Babylonian Jew on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The history of the Jews in Iraq ( he, יְהוּדִים בָּבְלִים, ', ; ar, اليهود العراقيون, ) is documented from the time of the

The history of the Jews in Iraq ( he, יְהוּדִים בָּבְלִים, ', ; ar, اليهود العراقيون, ) is documented from the time of the

After the fall of Jerusalem, Babylon became the focus of Judaism for more than a thousand years, and the place where Jews would define themselves as "a people without a land". In 587-6 BCE, following the fall of the

After the fall of Jerusalem, Babylon became the focus of Judaism for more than a thousand years, and the place where Jews would define themselves as "a people without a land". In 587-6 BCE, following the fall of the

After various changes of fortune,

After various changes of fortune,

Early Labor Zionism mostly concentrated on the Jews of Europe, skipping Iraqi Jews because of their lack of interest in agriculture. The result was that "Until World War II, Zionism made little headway because few Iraqi Jews were interested in the socialist ideal of manual labor in Palestine."

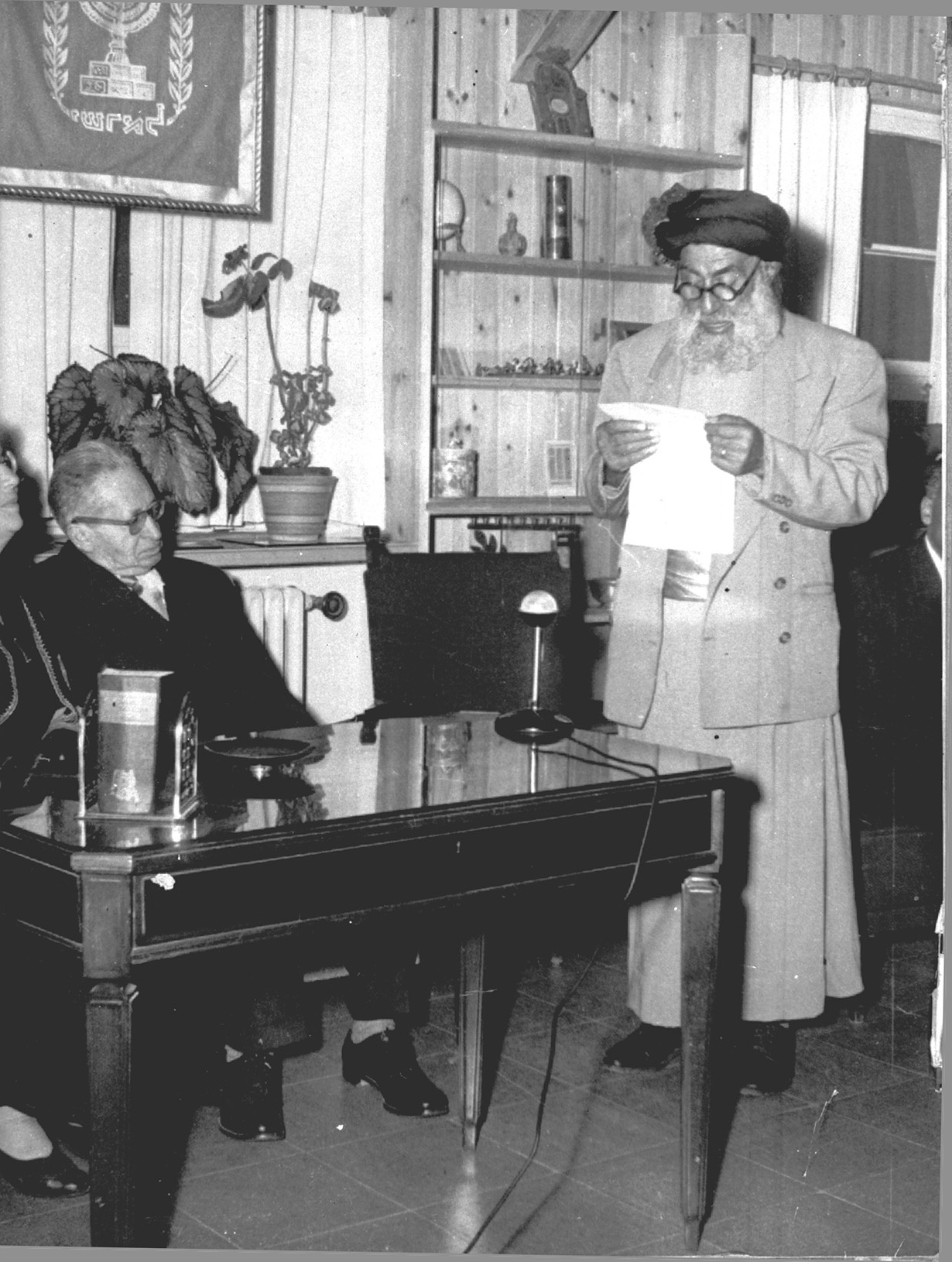

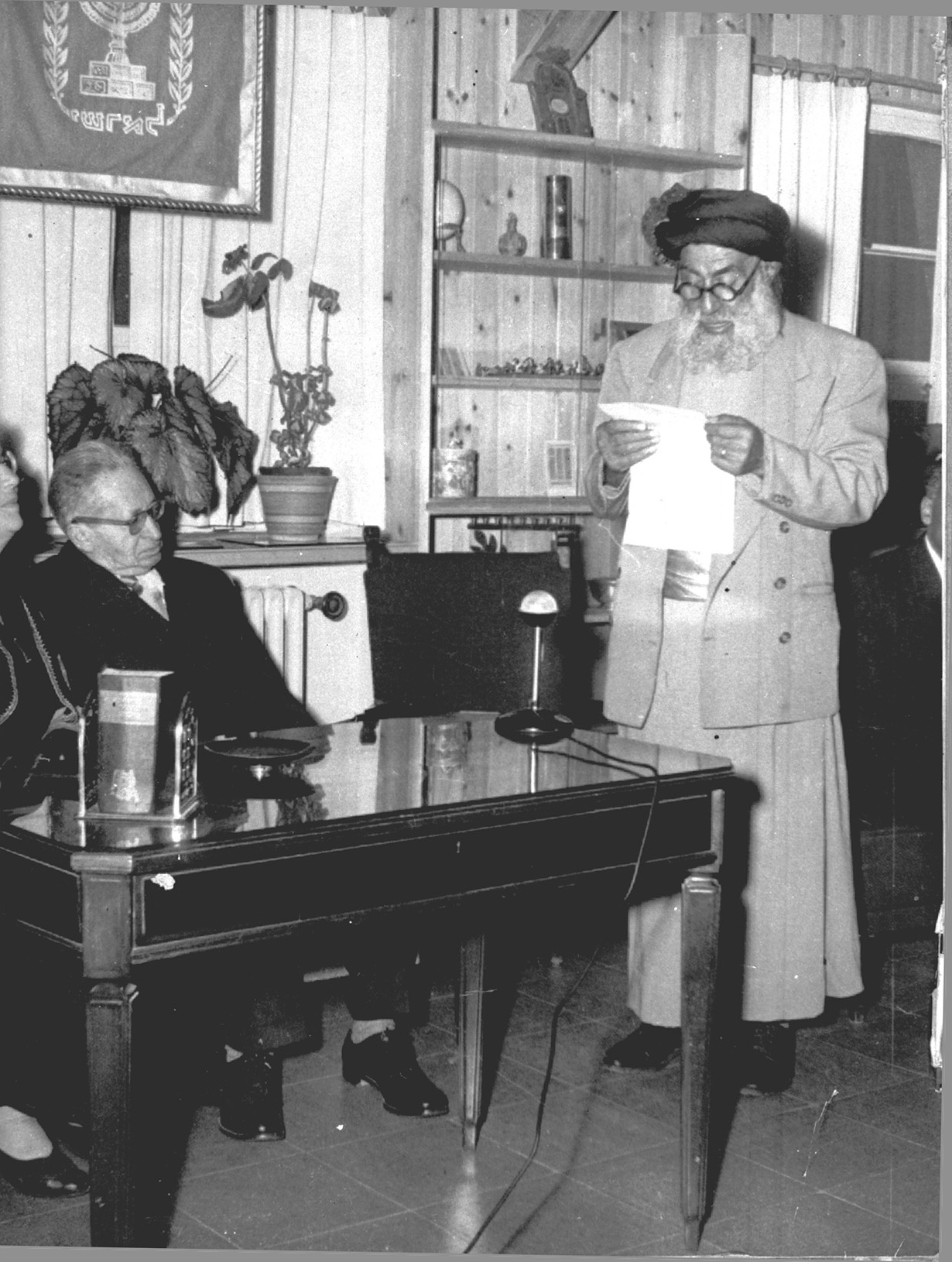

During the British Mandate, beginning in 1920, and in the early days after independence in 1932, well-educated Jews played an important role in civic life. Iraq's first minister of finance, Sir

Early Labor Zionism mostly concentrated on the Jews of Europe, skipping Iraqi Jews because of their lack of interest in agriculture. The result was that "Until World War II, Zionism made little headway because few Iraqi Jews were interested in the socialist ideal of manual labor in Palestine."

During the British Mandate, beginning in 1920, and in the early days after independence in 1932, well-educated Jews played an important role in civic life. Iraq's first minister of finance, Sir  Following the collapse of

Following the collapse of

With Iraqi Jews enduring oppression and being driven into destitution, the Iraqi Zionist underground began smuggling Jews out of Iraq to Israel starting in November 1948. Jews were smuggled into

With Iraqi Jews enduring oppression and being driven into destitution, the Iraqi Zionist underground began smuggling Jews out of Iraq to Israel starting in November 1948. Jews were smuggled into  From the start of the emigration law in March 1950 until the end of the year, 60,000 Jews registered to leave Iraq. In addition to continuing arrests and the dismissal of Jews from their jobs, this exodus was encouraged by a series of bombings starting in April 1950 that resulted in a number of injuries and a few deaths. Two months before the expiration of the law, by which time about 85,000 Jews had registered, another bomb at the Masuda Shemtov synagogue killed 3 or 5 Jews and injured many others. Iraqi Prime Minister Nuri al-Said was determined to drive the Jews out of his country as quickly as possible, and on August 21, 1950 he threatened to revoke the license of the company transporting the Jewish exodus if it did not fulfill its daily quota of 500 Jews. The available planes initially did not match the demand, and as a result many Jews had to wait for extended periods of time in Iraq while awaiting transport to Israel. These Jews, having already been

From the start of the emigration law in March 1950 until the end of the year, 60,000 Jews registered to leave Iraq. In addition to continuing arrests and the dismissal of Jews from their jobs, this exodus was encouraged by a series of bombings starting in April 1950 that resulted in a number of injuries and a few deaths. Two months before the expiration of the law, by which time about 85,000 Jews had registered, another bomb at the Masuda Shemtov synagogue killed 3 or 5 Jews and injured many others. Iraqi Prime Minister Nuri al-Said was determined to drive the Jews out of his country as quickly as possible, and on August 21, 1950 he threatened to revoke the license of the company transporting the Jewish exodus if it did not fulfill its daily quota of 500 Jews. The available planes initially did not match the demand, and as a result many Jews had to wait for extended periods of time in Iraq while awaiting transport to Israel. These Jews, having already been  Israel's fragile infrastructure, which already had to accommodate a mass influx of Jewish immigration from war-ravaged Europe and other Arab and Muslim countries, was heavily strained, and the Israeli government was not certain that it had enough permanent housing units and tents to accommodate the Iraqi Jews. When Israel attempted to negotiate a more gradual influx of Iraqi Jews, Said realized that the Jews could be turned into a demographic weapon against Israel. He hoped that a rapid influx of totally penniless Jews would collapse Israel's infrastructure. In March 1951, he engineered a law which would permanently freeze all assets of denaturalized Jews. Officially, the assets were merely frozen and not confiscated; under international law assets can theoretically remain frozen for perpetuity, making it impossible for them to ever be reclaimed. The law was prepared in secret, as it was being ratified, Baghdad's telephone network suspended operations to prevent Jews from learning of it and attempt to transfer or withdraw their money. Iraq's Banks were closed for three days to ensure that Jews could not access their funds. With Iraq's Jews effectively stripped of their assets permanently, Said demanded Israel accept 10,000 Iraqi Jewish refugees per month. He threatened to prohibit Jewish emigration from May 31, 1951 and to set up concentration camps for stateless Jews still in Iraq. Israel attempted to negotiate a compromise to enable the Iraqi Jews to leave gradually in a way that did not put as much pressure on Israel's absorptive capacity, but Said was adamant that the Jews had to leave as fast as possible. As a result, Israel increased the flights.

In Baghdad, the daily spectacle of Jews carrying nothing but their clothes and a bag of their remaining possessions being loaded onto trucks for transport to the airport caused public jubilation. Jews were mocked every step of the way during their departure and crowds stoned the trucks taking Jews to the airport. Jews were allowed to bring out a maximum of five pounds weight in property, which was to consist of personal effects only, as well as a small amount of cash. At the airport, Iraqi officials body searched every emigrant for cash or jewelry, and they also beat and spat on the departing Jews.

Overall, between 1948 and 1951, 121,633 Iraqi Jews were airlifted, bused, or smuggled out of the country, including 119,788 between January 1950 and December 1951. About 15,000 Jews remained in Iraq. In 1952, emigration to Israel was again banned, and the Iraqi government publicly hanged two Jews who had been falsely charged with throwing a bomb at the Baghdad office of the U.S. Information Agency.

According to Palestinian politician

Israel's fragile infrastructure, which already had to accommodate a mass influx of Jewish immigration from war-ravaged Europe and other Arab and Muslim countries, was heavily strained, and the Israeli government was not certain that it had enough permanent housing units and tents to accommodate the Iraqi Jews. When Israel attempted to negotiate a more gradual influx of Iraqi Jews, Said realized that the Jews could be turned into a demographic weapon against Israel. He hoped that a rapid influx of totally penniless Jews would collapse Israel's infrastructure. In March 1951, he engineered a law which would permanently freeze all assets of denaturalized Jews. Officially, the assets were merely frozen and not confiscated; under international law assets can theoretically remain frozen for perpetuity, making it impossible for them to ever be reclaimed. The law was prepared in secret, as it was being ratified, Baghdad's telephone network suspended operations to prevent Jews from learning of it and attempt to transfer or withdraw their money. Iraq's Banks were closed for three days to ensure that Jews could not access their funds. With Iraq's Jews effectively stripped of their assets permanently, Said demanded Israel accept 10,000 Iraqi Jewish refugees per month. He threatened to prohibit Jewish emigration from May 31, 1951 and to set up concentration camps for stateless Jews still in Iraq. Israel attempted to negotiate a compromise to enable the Iraqi Jews to leave gradually in a way that did not put as much pressure on Israel's absorptive capacity, but Said was adamant that the Jews had to leave as fast as possible. As a result, Israel increased the flights.

In Baghdad, the daily spectacle of Jews carrying nothing but their clothes and a bag of their remaining possessions being loaded onto trucks for transport to the airport caused public jubilation. Jews were mocked every step of the way during their departure and crowds stoned the trucks taking Jews to the airport. Jews were allowed to bring out a maximum of five pounds weight in property, which was to consist of personal effects only, as well as a small amount of cash. At the airport, Iraqi officials body searched every emigrant for cash or jewelry, and they also beat and spat on the departing Jews.

Overall, between 1948 and 1951, 121,633 Iraqi Jews were airlifted, bused, or smuggled out of the country, including 119,788 between January 1950 and December 1951. About 15,000 Jews remained in Iraq. In 1952, emigration to Israel was again banned, and the Iraqi government publicly hanged two Jews who had been falsely charged with throwing a bomb at the Baghdad office of the U.S. Information Agency.

According to Palestinian politician

The Forgotten Refugees: the Causes of the Post-1948 Jewish Exodus from Arab Countries

" Paper presented at the 14th Jewish Studies Conference, Melbourne, March 2002. ''Palestine Remembered''. Retrieved 15 May 2015. The affair has also been the subject of a libel lawsuit by

Most of the 15,000 Jews remaining after Operation Ezra and Nehemiah stayed through the Abdul Karim Qassim era when conditions improved and began to return to normal, but

Most of the 15,000 Jews remaining after Operation Ezra and Nehemiah stayed through the Abdul Karim Qassim era when conditions improved and began to return to normal, but

/ref> Among the American forces stationed in Iraq, there were only three Jewish chaplains. In 2011, a leaked US embassy cable named 8 Jews left in Baghdad; one of whom, Emhad Levy, immigrated to Israel. Andrew White, who was Vicar of St George's Church, Baghdad, urged the remaining Jews to immigrate. White also pleaded for help in saving remaining Torah scrolls in Iraq. Over Jewish protests, th

Iraqi Jewish Archive

is to be given by the U.S. government to the Iraqi government, instead of being returned to the Iraqi Jewish community; however, the archive can be seen online. In Al-Qosh, the Jewish prophet Nahum's tomb was being restored in 2020 thanks to a $1-million grant from the U.S., local authorities, and private donations. In 2020, the synagogue beside Ezekiel's Tomb was converted into a mosque. On March 15, 2021, one of the last remaining five Jews in Iraq, Dr. Dhafer Fouad Eliyahu, died. In November 2021, Israeli police recovered a Baghdad Torah scroll from an Arab village. In December 2021, Jews in Iraq received Hanukkah kits. On May 27, 2022, Iraq passed a law making contact with Israel punishable by death.

In 2021 the Jewish Population in Iraq number is fewer than five.Jewish Chronicle March 14, 2021

/ref>The number of living Jews in Iraq is 3 (2022)

Halban Publishers

2010) * Mona Yahia, ''When the Grey Beetles took over Baghdad''

Halban Publishers

2003)

Iraqi Jews Community By Kobi Arami

Iraqi Jews Worldwide

Iraqi Jews who left Baghdad during the 1960s and 1970s

The Jewish Community of Baghdad

Museum of the Jewish People at Beit Hatfutsot

Iraq Jews hub

at Iraqjews.org

Tradition of the Iraqi Jews

(mostly Hebrew, with links to recordings)

on the Jews of Iraq

Babylonia

at ''

Iraqi Jews in Israel: Two Iraqi Jewish Museums in Israel

at WZO

A Story of Successful Absorption: Aliyah from Iraq

at WZO

The Last Days in Babylon by Marina Benjamin

The story of the Iraqi Jews told through the life of the author's grandmother

Aiding the Enemy

Iraq's recent hatred for Jews makes it an odd place to celebrate Passover for American GIs, By T. Trent Gegax, ''

'It Is Now or Never'

Iraqi Jews who were stripped of their citizenship and their homes over the past half century may finally get a chance to reclaim them, By Sarah Sennott, Newsweek, MSNBC

Guide to the Robert Shasha Collection of Iraqi Jewish Oral Histories

at the American Sephardi Federation.

Personal Stories of Jews from Iraq

''Baghdad Twist''

Directed by Joe Balass. * 2013 �

''Farewell Baghdad''

Directed by Nissim Dayan. * 2014 – '' Shadow in Baghdad''. Directed by Duki Dror. {{DEFAULTSORT:History Of The Jews In Iraq Jewish ethnic groups

The history of the Jews in Iraq ( he, יְהוּדִים בָּבְלִים, ', ; ar, اليهود العراقيون, ) is documented from the time of the

The history of the Jews in Iraq ( he, יְהוּדִים בָּבְלִים, ', ; ar, اليهود العراقيون, ) is documented from the time of the Babylonian captivity

The Babylonian captivity or Babylonian exile is the period in Jewish history during which a large number of Judeans from the ancient Kingdom of Judah were captives in Babylon, the capital city of the Neo-Babylonian Empire, following their def ...

c. 586 BC. Iraqi Jews constitute one of the world's oldest and most historically significant Jewish

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

communities.

The Jewish community of what is termed in Jewish sources "Babylon" or "Babylonia" included Ezra

Ezra (; he, עֶזְרָא, '; fl. 480–440 BCE), also called Ezra the Scribe (, ') and Ezra the Priest in the Book of Ezra, was a Jewish scribe ('' sofer'') and priest ('' kohen''). In Greco-Latin Ezra is called Esdras ( grc-gre, Ἔσδρ� ...

the scribe, whose return to Judea

Judea or Judaea ( or ; from he, יהודה, Standard ''Yəhūda'', Tiberian ''Yehūḏā''; el, Ἰουδαία, ; la, Iūdaea) is an ancient, historic, Biblical Hebrew, contemporaneous Latin, and the modern-day name of the mountainous south ...

in the late 6th century BCE is associated with significant changes in Jewish ritual observance and the rebuilding of the Temple in Jerusalem

The Temple in Jerusalem, or alternatively the Holy Temple (; , ), refers to the two now-destroyed religious structures that served as the central places of worship for Israelites and Jews on the modern-day Temple Mount in the Old City of Jeru ...

. The Babylonian Talmud

The Talmud (; he, , Talmūḏ) is the central text of Rabbinic Judaism and the primary source of Jewish religious law ('' halakha'') and Jewish theology. Until the advent of modernity, in nearly all Jewish communities, the Talmud was the cen ...

was compiled in "Babylonia

Babylonia (; Akkadian: , ''māt Akkadī'') was an ancient Akkadian-speaking state and cultural area based in the city of Babylon in central-southern Mesopotamia (present-day Iraq and parts of Syria). It emerged as an Amorite-ruled state ...

", identified with modern Iraq.

From the biblical

The Bible (from Koine Greek , , 'the books') is a collection of religious texts or scriptures that are held to be sacred in Christianity, Judaism, Samaritanism, and many other religions. The Bible is an anthologya compilation of texts of a ...

Babylonian Babylonian may refer to:

* Babylon, a Semitic Akkadian city/state of ancient Mesopotamia founded in 1894 BC

* Babylonia, an ancient Akkadian-speaking Semitic nation-state and cultural region based in central-southern Mesopotamia (present-day Iraq)

...

period to the rise of the Islamic caliphate

A caliphate or khilāfah ( ar, خِلَافَة, ) is an institution or public office under the leadership of an Islamic steward with the title of caliph (; ar, خَلِيفَة , ), a person considered a political-religious successor to th ...

, the Jewish community of "Babylon" thrived as the center of Jewish learning. The Mongol

The Mongols ( mn, Монголчууд, , , ; ; russian: Монголы) are an East Asian ethnic group native to Mongolia, Inner Mongolia in China and the Buryatia Republic of the Russian Federation. The Mongols are the principal member ...

invasion and Islamic discrimination in the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire ...

led to its decline. Under the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

, the Jews of Iraq fared better. The community established modern schools in the second half of the 19th century. Driven by persecution, which saw many of the leading Jewish families of Baghdad flee for India

India, officially the Republic of India ( Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the ...

, and expanding trade with British colonies, the Jews of Iraq established a trading diaspora in Asia

Asia (, ) is one of the world's most notable geographical regions, which is either considered a continent in its own right or a subcontinent of Eurasia, which shares the continental landmass of Afro-Eurasia with Africa. Asia covers an ...

known as the Baghdadi Jews

The former communities of Jewish migrants and their descendants from Baghdad and elsewhere in the Middle East are traditionally called Baghdadi Jews or Iraqi Jews. They settled primarily in the ports and along the trade routes around the Indian ...

.

In the 20th century, Iraqi Jews played an important role in the early days of Iraq's independence. Between 1950 and 1952, 120,000–130,000 of the Iraqi Jewish community (around 75%) reached Israel in Operation Ezra and Nehemiah

From 1951 to 1952, Operation Ezra and Nehemiah airlifted between 120,000 and 130,000 Iraqi Jews to Israel via Iran and Cyprus. The massive emigration of Iraqi Jews was among the most climactic events of the Jewish exodus from the Muslim World.

T ...

.

The religious and cultural traditions of Iraqi Jews are kept alive today in strong communities established by Iraqi Jews in Israel

Iraqi Jews in Israel, also known as the Bavlim (Hebrew for " Babylonians"), are immigrants and descendants of the immigrants of the Iraqi Jewish communities, who now reside within the state of Israel. They number around 450,000.

History

Sinc ...

, especially in Or Yehuda

Or Yehuda ( he, אוֹר יְהוּדָה, ar, أور يهوده ) is a town in the Tel Aviv District of Gush Dan, Israel. In it had a population of .

History Prehistory

Human settlement back to the Chalcolithic has been found on the site.

, Givatayim

Givatayim ( he, גִּבְעָתַיִים, lit. "two hills") is a city in Israel east of Tel Aviv. It is part of the metropolitan area known as Gush Dan. Givatayim was established in 1922 by pioneers of the Second Aliyah. In it had a population o ...

and Kiryat Gat

Kiryat Gat, also spelled Qiryat Gat ( he, קִרְיַת גַּת), is a city in the Southern District of Israel. It lies south of Tel Aviv, north of Beersheba, and from Jerusalem. In it had a population of . The city hosts one of the most a ...

. According to government data as of 2014, there were 227,900 Jews of Iraqi descent in Israel, with other estimates as high as 600,000 Israelis having some Iraqi ancestry. Smaller communities upholding Iraqi Jewish traditions in the Jewish diaspora exist in the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the European mainland, continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

, Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe, north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel (Grea ...

, Australia, Singapore

Singapore (), officially the Republic of Singapore, is a sovereign island country and city-state in maritime Southeast Asia. It lies about one degree of latitude () north of the equator, off the southern tip of the Malay Peninsula, borde ...

, Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by tota ...

, and the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., federal district, five ma ...

.

The term "Babylonia"

What Jewish sources called "Babylon" and "Babylonia" may refer to the ancient city of Babylon and theNeo-Babylonian Empire

The Neo-Babylonian Empire or Second Babylonian Empire, historically known as the Chaldean Empire, was the last polity ruled by monarchs native to Mesopotamia. Beginning with the coronation of Nabopolassar as the King of Babylon in 626 BC and bei ...

; or, very often, it means the specific area of Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia ''Mesopotamíā''; ar, بِلَاد ٱلرَّافِدَيْن or ; syc, ܐܪܡ ܢܗܪ̈ܝܢ, or , ) is a historical region of Western Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the F ...

(the region between the Tigris and the Euphrates rivers) where a number of Jewish religious academies functioned during the Geonic

''Geonim'' ( he, גאונים; ; also transliterated Gaonim, singular Gaon) were the presidents of the two great Babylonian Talmudic Academies of Sura and Pumbedita, in the Abbasid Caliphate, and were the generally accepted spiritual leaders o ...

period (6th–11th century CE).

Early Biblical history

In the Bible, Babylon and the country of Babylonia are not always clearly distinguished, in most cases the same word being used for both. In some passages the land of Babylonia is calledShinar

Shinar (; Hebrew , Septuagint ) is the name for the southern region of Mesopotamia used by the Hebrew Bible.

Etymology

Hebrew שנער ''Šinʿar'' is equivalent to the Egyptian ''Sngr'' and Hittite ''Šanḫar(a)'', all referring to southern M ...

, while in the post-exilic literature it is called Chaldea

Chaldea () was a small country that existed between the late 10th or early 9th and mid-6th centuries BCE, after which the country and its people were absorbed and assimilated into the indigenous population of Babylonia. Semitic-speaking, it was ...

. In the Book of Genesis

The Book of Genesis (from Greek ; Hebrew: בְּרֵאשִׁית ''Bəreʾšīt'', "In hebeginning") is the first book of the Hebrew Bible and the Christian Old Testament. Its Hebrew name is the same as its first word, ( "In the beginning" ...

, Babylonia is described as the land in which Babel, Erech

Uruk, also known as Warka or Warkah, was an ancient city of Sumer (and later of Babylonia) situated east of the present bed of the Euphrates River on the dried-up ancient channel of the Euphrates east of modern Samawah, Al-Muthannā, Iraq.Ha ...

, Accad, and Calneh

Calneh () was a city founded by Nimrod, mentioned twice in the Hebrew Bible ().

are located – cities that are declared to have formed the beginning of Nimrod

Nimrod (; ; arc, ܢܡܪܘܕ; ar, نُمْرُود, Numrūd) is a biblical figure mentioned in the Book of Genesis and Books of Chronicles. The son of Cush and therefore a great-grandson of Noah, Nimrod was described as a king in the land of ...

's kingdom (). Here, the Tower of Babel

The Tower of Babel ( he, , ''Mīgdal Bāḇel'') narrative in Genesis 11:1–9 is an origin myth meant to explain why the world's peoples speak different languages.

According to the story, a united human race speaking a single language and mi ...

was located (); and it was also the seat of Amraphel's dominion ().

In the historical books, Babylonia is frequently referred to (there are no fewer than thirty-one allusion

Allusion is a figure of speech, in which an object or circumstance from unrelated context is referred to covertly or indirectly. It is left to the audience to make the direct connection. Where the connection is directly and explicitly stated (as ...

s in the Books of Kings), though the lack of a clear distinction between the city and the country is sometimes puzzling. Allusions to it are confined to the points of contact between the Israelites and the various Babylonian kings, especially Merodach-baladan (Berodach-baladan of ; compare ) and Nebuchadnezzar

Nebuchadnezzar II ( Babylonian cuneiform: ''Nabû-kudurri-uṣur'', meaning "Nabu, watch over my heir"; Biblical Hebrew: ''Nəḇūḵaḏneʾṣṣar''), also spelled Nebuchadrezzar II, was the second king of the Neo-Babylonian Empire, rulin ...

. In Books of Chronicles, Ezra

Ezra (; he, עֶזְרָא, '; fl. 480–440 BCE), also called Ezra the Scribe (, ') and Ezra the Priest in the Book of Ezra, was a Jewish scribe ('' sofer'') and priest ('' kohen''). In Greco-Latin Ezra is called Esdras ( grc-gre, Ἔσδρ� ...

, and Nehemiah

Nehemiah is the central figure of the Book of Nehemiah, which describes his work in rebuilding Jerusalem during the Second Temple period. He was governor of Persian Judea under Artaxerxes I of Persia (465–424 BC). The name is pronounced ...

the interest is transferred to Cyrus (see, for example, ), though the retrospect still deals with the conquests of Nebuchadnezzar

Nebuchadnezzar II ( Babylonian cuneiform: ''Nabû-kudurri-uṣur'', meaning "Nabu, watch over my heir"; Biblical Hebrew: ''Nəḇūḵaḏneʾṣṣar''), also spelled Nebuchadrezzar II, was the second king of the Neo-Babylonian Empire, rulin ...

, and Artaxerxes

Artaxerxes may refer to:

The throne name of several Achaemenid rulers of the 1st Persian Empire:

* Artaxerxes I of Persia (died 425 BC), Artaxerxes I Longimanus, ''r.'' 466–425 BC, son and successor of Xerxes I

* Artaxerxes II of Persia (436 ...

is mentioned once ().

In the poetical literature of Israel, Babylonia plays an insignificant part (see , and especially Psalm 137), but it fills a very large place in the Prophets. The Book of Isaiah resounds with the "burden of Babylon" (), though at that time it still seemed a "far country" (). In the number and importance of its references to Babylonian life and history, the Book of Jeremiah

The Book of Jeremiah ( he, ספר יִרְמְיָהוּ) is the second of the Latter Prophets in the Hebrew Bible, and the second of the Prophets in the Christian Old Testament. The superscription at chapter Jeremiah 1:1–3 identifies the boo ...

stands preeminent in the Hebrew literature. With numerous important allusions to events in the reign of Nebuchadnezzar, Jeremiah

Jeremiah, Modern: , Tiberian: ; el, Ἰερεμίας, Ieremíās; meaning "Yah shall raise" (c. 650 – c. 570 BC), also called Jeremias or the "weeping prophet", was one of the major prophets of the Hebrew Bible. According to Jewis ...

has become a valuable source in reconstructing Babylonian history within recent times. The inscriptions of Nebuchadnezzar are almost exclusively devoted to building operations; and but for the Book of Jeremiah, little would be known of his campaign against Jerusalem.

Late Biblical history and the Babylonian exile

During the 6th century BCE, the Jews of the ancientKingdom of Judah

The Kingdom of Judah ( he, , ''Yəhūdā''; akk, 𒅀𒌑𒁕𒀀𒀀 ''Ya'údâ'' 'ia-ú-da-a-a'' arc, 𐤁𐤉𐤕𐤃𐤅𐤃 ''Bēyt Dāwīḏ'', " House of David") was an Israelite kingdom of the Southern Levant during the Iron Age. ...

were exiled to Babylon by Nebuchadnezzar

Nebuchadnezzar II ( Babylonian cuneiform: ''Nabû-kudurri-uṣur'', meaning "Nabu, watch over my heir"; Biblical Hebrew: ''Nəḇūḵaḏneʾṣṣar''), also spelled Nebuchadrezzar II, was the second king of the Neo-Babylonian Empire, rulin ...

in three waves. These three separate occasions are mentioned in the Book of Jeremiah

The Book of Jeremiah ( he, ספר יִרְמְיָהוּ) is the second of the Latter Prophets in the Hebrew Bible, and the second of the Prophets in the Christian Old Testament. The superscription at chapter Jeremiah 1:1–3 identifies the boo ...

(). The first was in the time of Jehoiachin

Jeconiah ( he, יְכָנְיָה ''Yəḵonəyā'' , meaning "Yah has established"; el, Ιεχονιας; la, Iechonias, Jechonias), also known as Coniah and as Jehoiachin ( he, יְהוֹיָכִין ''Yəhōyāḵīn'' ; la, Ioachin, Joach ...

in 597 BC, when, in retaliation for a refusal to pay tribute, the First Temple in Jerusalem was partially despoiled and a number of the leading citizens removed (Book of Daniel

The Book of Daniel is a 2nd-century BC biblical apocalypse with a 6th century BC setting. Ostensibly "an account of the activities and visions of Daniel, a noble Jew exiled at Babylon", it combines a prophecy of history with an eschatology ...

, ). After eleven years, in the reign of Zedekiah—who had been enthroned by Nebuchadnezzar— a fresh revolt of the Judaeans took place, perhaps encouraged by the close proximity of the Egyptian army. The city was razed to the ground, and a further deportation ensued. Finally, five years later, Jeremiah records a third captivity. After the overthrow of Babylonia by the Persians

The Persians are an Iranian ethnic group who comprise over half of the population of Iran. They share a common cultural system and are native speakers of the Persian language as well as of the languages that are closely related to Persian.

...

, Cyrus gave the Jews permission to return to their native land (537 BC), and more than forty thousand are said to have availed themselves of the privilege. (See Jehoiakim

Jehoiakim, also sometimes spelled Jehoikim; la, Joakim was the eighteenth and antepenultimate king of Judah from 609 to 598 BC. He was the second son of king Josiah () and Zebidah, the daughter of Pedaiah of Rumah. His birth name was Eliakim.; ...

; Ezra

Ezra (; he, עֶזְרָא, '; fl. 480–440 BCE), also called Ezra the Scribe (, ') and Ezra the Priest in the Book of Ezra, was a Jewish scribe ('' sofer'') and priest ('' kohen''). In Greco-Latin Ezra is called Esdras ( grc-gre, Ἔσδρ� ...

; Nehemiah

Nehemiah is the central figure of the Book of Nehemiah, which describes his work in rebuilding Jerusalem during the Second Temple period. He was governor of Persian Judea under Artaxerxes I of Persia (465–424 BC). The name is pronounced ...

.)

The earliest accounts of the Jews exiled to Babylonia are furnished only by scanty biblical details, although a number of archaeological discoveries shed light into the social lives of the deportees; certain sources seek to supply this deficiency from the realms of legend and tradition. Thus, the so-called "Small Chronicle" (Seder Olam Zutta

Seder Olam Zutta (Hebrew: ) is an anonymous chronicle from 803 CE, called "Zuta" (= "smaller," or "younger") to distinguish it from the older ''Seder Olam Rabbah.'' This work is based upon, and to a certain extent completes and continues, the olde ...

) endeavors to preserve historic continuity by providing a genealogy of the exilarch

The exilarch was the leader of the Jewish community in Persian Mesopotamia (modern day Iraq) during the era of the Parthians, Sasanians and Abbasid Caliphate up until the Mongol invasion of Baghdad in 1258, with intermittent gaps due to ongoin ...

s ("Reshe Galuta") back to King Jeconiah

Jeconiah ( he, יְכָנְיָה ''Yəḵonəyā'' , meaning "Yah has established"; el, Ιεχονιας; la, Iechonias, Jechonias), also known as Coniah and as Jehoiachin ( he, יְהוֹיָכִין ''Yəhōyāḵīn'' ; la, Ioachin, Joach ...

; indeed, Jeconiah himself is made an exilarch. The "Small Chronicle's" states that Zerubbabel

According to the biblical narrative, Zerubbabel, ; la, Zorobabel; Akkadian: 𒆰𒆍𒀭𒊏𒆠 ''Zērubābili'' was a governor of the Achaemenid Empire's province Yehud Medinata and the grandson of Jeconiah, penultimate king of Judah. Zerubba ...

returned to Judea in the Greek period. Certainly, the descendants of the Davidic line occupied an exalted position among their brethren in Babylonia, as they did at that period in Judea. During the Maccabean revolt

The Maccabean Revolt ( he, מרד החשמונאים) was a Jewish rebellion led by the Maccabees against the Seleucid Empire and against Hellenistic influence on Jewish life. The main phase of the revolt lasted from 167–160 BCE and ended ...

, these Judean descendants of the royal house had immigrated to Babylonia.

Achaemenid period

According to the biblical account, the Persian emperor Cyrus the Great was "God's anointed", having freed the Jews from Babylonian rule. After the conquest of Babylonia by the Persian Achaemenid Empire Cyrus granted all the Jews citizenship and by decree allowed the Jews to return to Israel (around 537 BCE). Subsequently, successive waves of Babylonian Jews emigrated to Israel. Ezra (/ˈɛzrə/; Hebrew: עֶזְרָא, ‘Ezrā; fl. 480–440 BCE), also called Ezra the Scribe (עֶזְרָא הַסּוֹפֵר, Ezra ha-Sofer) and Ezra the Priest in the Book of Ezra, a Jewish scribe (sofer) and priest (kohen), returned from Babylonian exile and reintroduced the Torah in Jerusalem (Ezra 7–10 and Neh 8).Greek period

WithAlexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon ( grc, Ἀλέξανδρος, Alexandros; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the ancient Greek kingdom of Macedon. He succeeded his father Philip II to ...

's campaign, accurate information concerning the Jews in the East reached the western world. Alexander's army contained numerous Jews who refused, from religious scruples, to take part in the reconstruction of the destroyed Belus temple in Babylon. The accession of Seleucus Nicator

Seleucus I Nicator (; ; grc-gre, Σέλευκος Νικάτωρ , ) was a Macedonian Greek general who was an officer and successor ( ''diadochus'') of Alexander the Great. Seleucus was the founder of the eponymous Seleucid Empire. In the po ...

, 312 BC, to whose extensive empire Babylonia belonged, was accepted by the Jews and Syrians for many centuries as the commencement of a new era for reckoning time, called "minyan sheṭarot", æra contractuum, or era of contracts, which was also officially adopted by the Parthians. This so-called Seleucid era

The Seleucid era ("SE") or (literally "year of the Greeks" or "Greek year"), sometimes denoted "AG," was a system of numbering years in use by the Seleucid Empire and other countries among the ancient Hellenistic civilizations. It is sometimes ...

survived in the Orient long after it had been abolished in the West (see Sherira's "Letter," ed. Neubauer, p. 28). Nicator's foundation of a city, Seleucia, on the Tigris is mentioned by the Rabbis ( Midr. The. ix. 8); both the "Large" and the "Small Chronicle" contain references to him. The important victory which the Jews are said to have gained over the Galatians in Babylonia (see II Maccabees – ) must have happened under Seleucus Callinicus or under Antiochus III

Antiochus III the Great (; grc-gre, Ἀντίoχoς Μέγας ; c. 2413 July 187 BC) was a Greek Hellenistic king and the 6th ruler of the Seleucid Empire, reigning from 222 to 187 BC. He ruled over the region of Syria and large parts of the r ...

. The last-named settled a large number of Babylonian Jews as colonists in his western dominions, with the view of checking certain revolutionary tendencies disturbing those lands. Mithridates

Mithridates or Mithradates ( Old Persian 𐎷𐎡𐎰𐎼𐎭𐎠𐎫 ''Miθradāta'') is the Hellenistic form of an Iranian theophoric name, meaning "given by the Mithra". Its Modern Persian form is Mehrdad. It may refer to:

Rulers

*Of Cius (al ...

(174–136 BC) subjugated, about the year 160, the province of Babylonia, and thus the Jews for four centuries came under Parthian domination.

Parthian period

Jewish sources contain no mention ofParthia

Parthia ( peo, 𐎱𐎼𐎰𐎺 ''Parθava''; xpr, 𐭐𐭓𐭕𐭅 ''Parθaw''; pal, 𐭯𐭫𐭮𐭥𐭡𐭥 ''Pahlaw'') is a historical region located in northeastern Greater Iran. It was conquered and subjugated by the empire of the Mede ...

n influence; the very name "Parthian" does not occur, unless indeed "Parthian" is meant by "Persian", which occurs now and then. The Armenia

Armenia (), , group=pron officially the Republic of Armenia,, is a landlocked country in the Armenian Highlands of Western Asia.The UNbr>classification of world regions places Armenia in Western Asia; the CIA World Factbook , , and ...

n prince Sanatroces, of the royal house of the Arsacides, is mentioned in the "Small Chronicle" as one of the successors ( diadochoi) of Alexander. Among other Asiatic princes, the Roman rescript in favor of the Jews reached Arsaces as well ( I Macc. xv. 22); it is not, however, specified which Arsaces. Not long after this, the Partho-Babylonian country was trodden by the army of a Jewish prince; the Syrian king, Antiochus VII Sidetes

Antiochus VII Euergetes ( el, Ἀντίοχος Ευεργέτης; c. 164/160 BC129 BC), nicknamed Sidetes ( el, Σιδήτης) (from Side, a city in Asia Minor), also known as Antiochus the Pious, was ruler of the Hellenistic Seleucid Empir ...

, marched, in company with Hyrcanus I, against the Parthians; and when the allied armies defeated the Parthians (129 BC) at the Great Zab

The Great Zab or Upper Zab ( (''al-Zāb al-Kabīr''), or , , ''(zāba ʻalya)'') is an approximately long river flowing through Turkey and Iraq. It rises in Turkey near Lake Van and joins the Tigris in Iraq south of Mosul. The drainage basin o ...

(Lycus), the king ordered a halt of two days on account of the Jewish Sabbath and Feast of Weeks. In 40 BC. the Jewish puppet-king, Hyrcanus II

John Hyrcanus II (, ''Yohanan Hurqanos'') (died 30 BCE), a member of the Hasmonean dynasty, was for a long time the Jewish High Priest in the 1st century BCE. He was also briefly King of Judea 67–66 BCE and then the ethnarch (ruler) of ...

, fell into the hands of the Parthians, who, according to their custom, cut off his ears in order to render him unfit for rulership. The Jews of Babylonia, it seems, had the intention of founding a high-priesthood for the exiled Hyrcanus, which they would have made quite independent of Judea. But the reverse was to come about: the Judeans received a Babylonian, Ananel by name, as their high priest which indicates the importance enjoyed by the Jews of Babylonia. Still in religious matters the Babylonians, as indeed the whole diaspora, were in many regards dependent upon Judea. They went on pilgrimages to Jerusalem for the festivals.

How free a hand the Parthians permitted the Jews is perhaps best illustrated by the rise of the little Jewish robber-state in Nehardea

Nehardea or Nehardeah ( arc, נהרדעא, ''nəhardəʿā'' "river of knowledge") was a city from the area called by ancient Jewish sources Babylonia, situated at or near the junction of the Euphrates with the Nahr Malka (the Royal Canal), one ...

(see Anilai and Asinai). Still more remarkable is the conversion of the king of Adiabene

Adiabene was an ancient kingdom in northern Mesopotamia, corresponding to the northwestern part of ancient Assyria. The size of the kingdom varied over time; initially encompassing an area between the Zab Rivers, it eventually gained control of N ...

to Judaism. These instances show not only the tolerance, but the weakness of the Parthian kings. The Babylonian Jews wanted to fight in common cause with their Judean brethren against Vespasian

Vespasian (; la, Vespasianus ; 17 November AD 9 – 23/24 June 79) was a Roman emperor who reigned from AD 69 to 79. The fourth and last emperor who reigned in the Year of the Four Emperors, he founded the Flavian dynasty that ruled the Em ...

; but it was not until the Romans waged war under Trajan

Trajan ( ; la, Caesar Nerva Traianus; 18 September 539/11 August 117) was Roman emperor from 98 to 117. Officially declared ''optimus princeps'' ("best ruler") by the senate, Trajan is remembered as a successful soldier-emperor who presid ...

against Parthia

Parthia ( peo, 𐎱𐎼𐎰𐎺 ''Parθava''; xpr, 𐭐𐭓𐭕𐭅 ''Parθaw''; pal, 𐭯𐭫𐭮𐭥𐭡𐭥 ''Pahlaw'') is a historical region located in northeastern Greater Iran. It was conquered and subjugated by the empire of the Mede ...

that they made their hatred felt; so that it was in a great measure owing to the revolt of the Babylonian Jews that the Romans did not become masters of Babylonia too. Philo speaks of the large number of Jews resident in that country, a population which was no doubt considerably swelled by new immigrants after the destruction of Jerusalem. Accustomed in Jerusalem from early times to look to the east for help, and aware, as the Roman procurator Petronius was, that the Jews of Babylon could render effectual assistance, Babylonia became with the fall of Jerusalem the very bulwark of Judaism. The collapse of the Bar Kochba revolt no doubt added to the number of Jewish refugees in Babylon.

In the continuous Roman–Persian Wars

The Roman–Persian Wars, also known as the Roman–Iranian Wars, were a series of conflicts between states of the Greco-Roman world and two successive Iranian empires: the Parthian and the Sasanian. Battles between the Parthian Empire and the ...

, the Jews had every reason to hate the Romans, the destroyers of their sanctuary, and to side with the Parthians, their protectors. Possibly it was recognition of services thus rendered by the Jews of Babylonia, and by the Davidic house especially, that induced the Parthian kings to elevate the princes of the Exile, who until then had been little more than mere collectors of revenue, to the dignity of real princes, called ''Resh Galuta

The exilarch was the leader of the Jewish community in Persian Mesopotamia (modern day Iraq) during the era of the Parthians, Sasanians and Abbasid Caliphate up until the Mongol invasion of Baghdad in 1258, with intermittent gaps due to ongoing ...

''. Thus, then, the numerous Jewish subjects were provided with a central authority which assured an undisturbed development of their own internal affairs.

Babylonia as the center of Judaism

After the fall of Jerusalem, Babylon became the focus of Judaism for more than a thousand years, and the place where Jews would define themselves as "a people without a land". In 587-6 BCE, following the fall of the

After the fall of Jerusalem, Babylon became the focus of Judaism for more than a thousand years, and the place where Jews would define themselves as "a people without a land". In 587-6 BCE, following the fall of the Kingdom of Judah

The Kingdom of Judah ( he, , ''Yəhūdā''; akk, 𒅀𒌑𒁕𒀀𒀀 ''Ya'údâ'' 'ia-ú-da-a-a'' arc, 𐤁𐤉𐤕𐤃𐤅𐤃 ''Bēyt Dāwīḏ'', " House of David") was an Israelite kingdom of the Southern Levant during the Iron Age. ...

and the destruction of the First Temple

Solomon's Temple, also known as the First Temple (, , ), was the Temple in Jerusalem between the 10th century BC and . According to the Hebrew Bible, it was commissioned by Solomon in the United Kingdom of Israel before being inherited by th ...

, Jews were brought to the region between the Tigris and the Euphrates rivers, also known as Mesopotamia. This period in Jewish history became known as the Babylonian captivity

The Babylonian captivity or Babylonian exile is the period in Jewish history during which a large number of Judeans from the ancient Kingdom of Judah were captives in Babylon, the capital city of the Neo-Babylonian Empire, following their def ...

. Some five centuries later, after the destruction of the Second Temple

The Second Temple (, , ), later known as Herod's Temple, was the reconstructed Temple in Jerusalem between and 70 CE. It replaced Solomon's Temple, which had been built at the same location in the United Kingdom of Israel before being inherite ...

in Jerusalem, there was a wide dispersion of Jews in which many ended up in Babylonia. The Jews of Babylon would for the first time write prayers in a language other than Hebrew, such as the Kaddish

Kaddish or Qaddish or Qadish ( arc, קדיש "holy") is a hymn praising God that is recited during Jewish prayer services. The central theme of the Kaddish is the magnification and sanctification of God's name. In the liturgy, different versio ...

, written in Judeo-Aramaic

Judaeo-Aramaic languages represent a group of Hebrew-influenced Aramaic and Neo-Aramaic languages.

Early use

Aramaic, like Hebrew, is a Northwest Semitic language, and the two share many features. From the 7th century BCE, Aramaic became th ...

– a harbinger of the many languages in which Jewish prayers in the diaspora would come to be written in, such as Greek, Arabic, and Turkish.

Babylon therefore became the center of Jewish religion and culture in exile. Many esteemed and influential Jewish scholars dating back to Amoraim have their roots in Babylonian Jewry and culture.

The Iraqi Jewish community formed a homogeneous group, maintaining communal Jewish identity, culture and traditions. The Jews in Iraq distinguished themselves by the way they spoke in their old Arabic dialect, Judeo-Arabic

Judeo-Arabic dialects (, ; ; ) are ethnolects formerly spoken by Jews throughout the Arabic-speaking world. Under the ISO 639 international standard for language codes, Judeo-Arabic is classified as a macrolanguage under the code jrb, encom ...

; the way they dressed; observation of Jewish rituals, for example, the Sabbath

In Abrahamic religions, the Sabbath () or Shabbat (from Hebrew ) is a day set aside for rest and worship. According to the Book of Exodus, the Sabbath is a day of rest on the seventh day, commanded by God to be kept as a holy day of rest, as G ...

and holidays

A holiday is a day set aside by custom or by law on which normal activities, especially business or work including school, are suspended or reduced. Generally, holidays are intended to allow individuals to celebrate or commemorate an event or t ...

; and kashrut.

The rabbi Abba Arika

Abba Arikha (175–247 CE; Jewish Babylonian Aramaic: ; born: ''Rav Abba bar Aybo'', ), commonly known as Rav (), was a Jewish amora of the 3rd century. He was born and lived in Kafri, Asoristan, in the Sasanian Empire.

Abba Arikha establi ...

(175–247 AD), known as ''Rab'' due to his status as the highest authority in Judaism, is considered by the Jewish oral tradition the key leader, who along with the whole people in diaspora, maintained Judaism after the destruction of Jerusalem

The siege of Jerusalem of 70 CE was the decisive event of the First Jewish–Roman War (66–73 CE), in which the Roman army led by future emperor Titus besieged Jerusalem, the center of Jewish rebel resistance in the Roman province of Ju ...

. After studying in Palestine at the academy of Judah I, Rab returned to his Babylonian home; his arrival, in the year 530 in the Seleucidan calendar, or 219 AD, is considered to mark the beginning of a new era for the Jewish people, initiating the dominant role that the Babylonian academies played for several centuries, for the first time surpassing Judea

Judea or Judaea ( or ; from he, יהודה, Standard ''Yəhūda'', Tiberian ''Yehūḏā''; el, Ἰουδαία, ; la, Iūdaea) is an ancient, historic, Biblical Hebrew, contemporaneous Latin, and the modern-day name of the mountainous south ...

and Galilee

Galilee (; he, הַגָּלִיל, hagGālīl; ar, الجليل, al-jalīl) is a region located in northern Israel and southern Lebanon. Galilee traditionally refers to the mountainous part, divided into Upper Galilee (, ; , ) and Lower Gali ...

in the quality of Torah study. Most Jews to this day rely on the quality of the work of Babylonian scholars during this period over that of the Galilee from the same period. The Jewish community of Babylon was already learned, but Rab focused and organised their study. Leaving an existing Babylonian academy at Nehardea

Nehardea or Nehardeah ( arc, נהרדעא, ''nəhardəʿā'' "river of knowledge") was a city from the area called by ancient Jewish sources Babylonia, situated at or near the junction of the Euphrates with the Nahr Malka (the Royal Canal), one ...

for his colleague Samuel

Samuel ''Šəmūʾēl'', Tiberian: ''Šămūʾēl''; ar, شموئيل or صموئيل '; el, Σαμουήλ ''Samouḗl''; la, Samūēl is a figure who, in the narratives of the Hebrew Bible, plays a key role in the transition from the bi ...

, Rab founded a new academy at Sura, where he and his family already owned property, and which was known as a Jewish city. Rab's move created an environment in which Babylon had two contemporary leading academies that competed with one another, yet were so far removed from one another that they could never interfere with each other's operations. Since Rab and Samuel were acknowledged peers in position and learning, their academies likewise were considered of equal rank and influence. Their relationship can be compared to that between the Jerusalemite academies of the House of Hillel Ha-Zaken and the House of Shammai

The House of Hillel (Beit Hillel) and House of Shammai (Beit Shammai) were, among Jewish scholars, two schools of thought during the period of tannaim, named after the sages Hillel and Shammai (of the last century BCE and the early 1st century CE) ...

, albeit Rab and Samuel agreed with each other far more often than did the houses of Hillel and Shammai. Thus, both Babylonian rabbinical schools opened a new era for diaspora Judaism, and the ensuing discussions in their classes furnished the earliest stratum and style of the scholarly material deposited in the Babylonian Talmud

The Talmud (; he, , Talmūḏ) is the central text of Rabbinic Judaism and the primary source of Jewish religious law ('' halakha'') and Jewish theology. Until the advent of modernity, in nearly all Jewish communities, the Talmud was the cen ...

. The coexistence for many decades of these two colleges of equal rank, even after the school at Nehardea

Nehardea or Nehardeah ( arc, נהרדעא, ''nəhardəʿā'' "river of knowledge") was a city from the area called by ancient Jewish sources Babylonia, situated at or near the junction of the Euphrates with the Nahr Malka (the Royal Canal), one ...

was moved to Pumbedita

Pumbedita (sometimes Pumbeditha, Pumpedita, or Pumbedisa; arc, פוּמְבְּדִיתָא ''Pūmbəḏīṯāʾ'', "The Mouth of the River,") was an ancient city located near the modern-day city of Fallujah, Iraq. It is known for having hosted t ...

(now Fallujah

Fallujah ( ar, ٱلْفَلُّوجَة, al-Fallūjah, Iraqi pronunciation: ) is a city in the Iraqi province of Al Anbar, located roughly west of Baghdad on the Euphrates. Fallujah dates from Babylonian times and was host to important J ...

), produced for the first time in Babylonia the phenomenon of dual leadership that, with some slight interruptions, became a permanent fixture and a weighty factor in the development of the Jewish faith today.

The key work of these semi-competing academies was the compilation of the Babylonian Talmud (the discussions from these two cities), completed by Rav Ashi and Ravina, two successive leaders of the Babylonian Jewish community, around the year 520, though rougher copies had already been circulated to the Jews of the Byzantine Empire. Editorial work by the Savoraim or ''Rabbanan Savoraei'' (post-Talmudic rabbis), continued on this text's grammar for the next 250 years; much of the text did not reach its "perfected" form until around 600–700 AD. The Mishnah

The Mishnah or the Mishna (; he, מִשְׁנָה, "study by repetition", from the verb ''shanah'' , or "to study and review", also "secondary") is the first major written collection of the Jewish oral traditions which is known as the Oral Tora ...

, which had been completed in the early 3rd century AD, and the Babylonian Gemara (the discussions at and around these academies) together form the ''Talmud Bavli'' (the "Babylonian Talmud"). The Babylonian Jews became the keepers of the Bible. Jewish culture flourished in Babylonia during the Sasanian Empire (331–638) and catalyzed the rise of Rabbinic Judaism and central texts. Jewish scholars compiled the Babylonian Talmud starting in 474 as the spiritual codex

The codex (plural codices ) was the historical ancestor of the modern book. Instead of being composed of sheets of paper, it used sheets of vellum, papyrus, or other materials. The term ''codex'' is often used for ancient manuscript books, with ...

of Judaism, transferring Judaism into a spiritual and moral movement. The Talmud, a central commentary on the Mishnah, was perceived as a "portable homeland" for the Jews in diaspora.

The three centuries in the course of which the Babylonian Talmud was developed in the academies founded by Rab and Samuel were followed by five centuries during which it was intensely preserved, studied, expounded in the schools, and, through their influence, discipline and work, recognized by the whole diaspora. Sura

A ''surah'' (; ar, سورة, sūrah, , ), is the equivalent of "chapter" in the Qur'an. There are 114 ''surahs'' in the Quran, each divided into '' ayats'' (verses). The chapters or ''surahs'' are of unequal length; the shortest surah ('' Al-K ...

, Nehardea

Nehardea or Nehardeah ( arc, נהרדעא, ''nəhardəʿā'' "river of knowledge") was a city from the area called by ancient Jewish sources Babylonia, situated at or near the junction of the Euphrates with the Nahr Malka (the Royal Canal), one ...

, and Pumbedita

Pumbedita (sometimes Pumbeditha, Pumpedita, or Pumbedisa; arc, פוּמְבְּדִיתָא ''Pūmbəḏīṯāʾ'', "The Mouth of the River,") was an ancient city located near the modern-day city of Fallujah, Iraq. It is known for having hosted t ...

were considered the seats of diaspora learning; and the heads of these authorities were referred to later on as ''Geonim

''Geonim'' ( he, גאונים; ; also Romanization of Hebrew, transliterated Gaonim, singular Gaon) were the presidents of the two great Talmudic Academies in Babylonia, Babylonian Talmudic Academies of Sura Academy , Sura and Pumbedita Academy ...

'' and were considered the highest authorities on religious matters in the Jewish world. Their decisions were sought from all sides and were accepted wherever diaspora Jewish communal life existed. They even successfully competed against the learning coming from the Land of Israel itself. In the words of the haggadist, "God created these two academies in order that the promise might be fulfilled, that 'the word of God should never depart from Israel's mouth (Isa. lix. 21). The periods of Jewish history immediately following the close of the Talmud

The Talmud (; he, , Talmūḏ) is the central text of Rabbinic Judaism and the primary source of Jewish religious law ('' halakha'') and Jewish theology. Until the advent of modernity, in nearly all Jewish communities, the Talmud was the cen ...

are designated according to the titles of the teachers at Sura and Pumbedita; thus we have the time of the Geonim and that of the Saboraim. The Saboraim were the scholars whose diligent hands completed the Talmud and the first great Talmudic commentaries in the first third of the 6th century. The two academies among others, and the Jewish community they led, lasted until the middle of the 11th century, Pumbedita faded after its chief rabbi was murdered in 1038, and Sura faded soon after. Which ended for centuries the great scholarly reputation given to Babylonian Jews, as the center of Jewish thought.

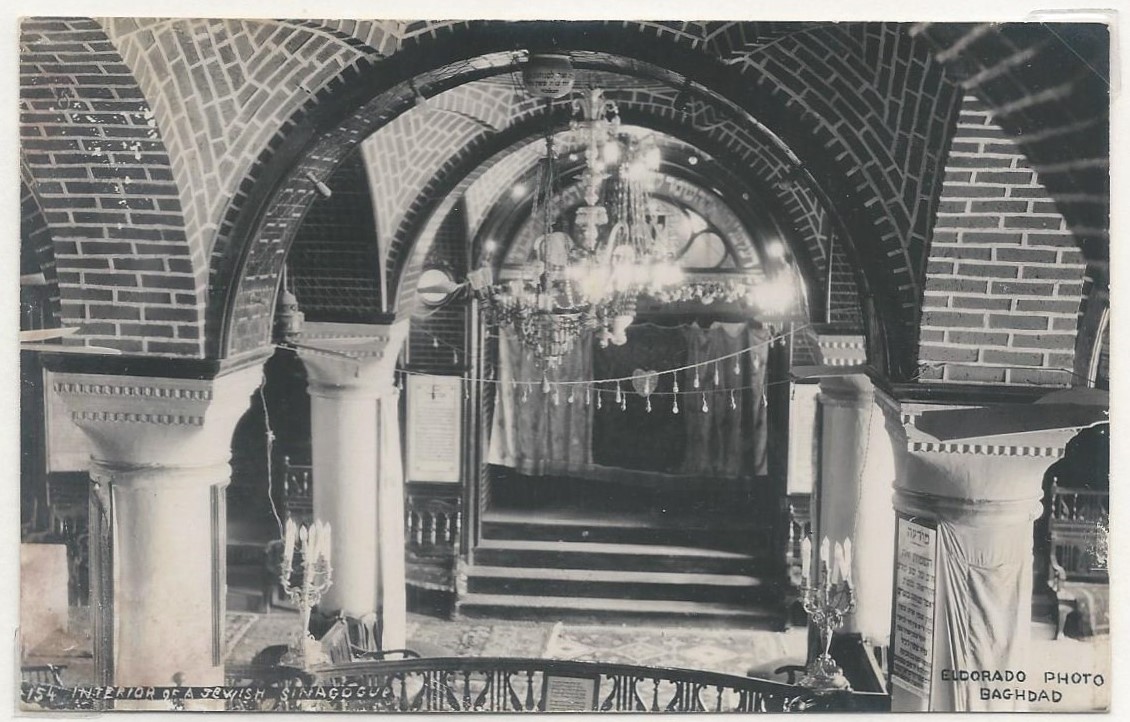

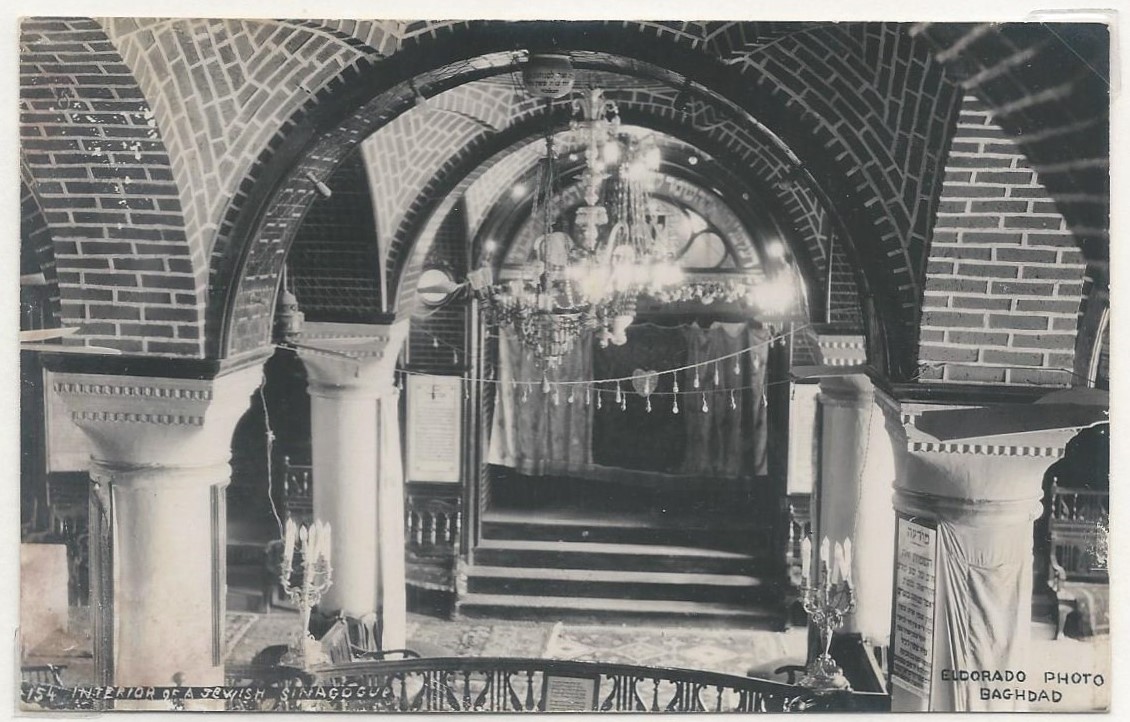

Iraq's Jewish community reached an apex in the 12th century, with 40,000 Jews, 28 synagogues, and ten '' yeshivot'', or Rabbinic academies. Jews participated in commerce, artisanal labor and medicine. Under Mongol rule (1258–1335) Jewish physician Sa’ad Al-Dawla served as , or assistant director of the financial administration of Baghdad, as well as Chief Vizier of the Mongol Empire.

During Ottoman rule (1534–1917) Jewish life prospered in Iraq. Jews were afforded religious liberties, enabling them to administer their own affairs in Jewish education. Tolerance towards Jews and Jewish customs, however, depended on local rulers. Ottoman ruler Sultan Murad IV

Murad IV ( ota, مراد رابع, ''Murād-ı Rābiʿ''; tr, IV. Murad, was the Sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 1623 to 1640, known both for restoring the authority of the state and for the brutality of his methods. Murad IV was born in Con ...

appointed 10,000 Jewish officers in his government, as he valued the Baghdadi Jews. In contrast, Murad's governor Dauod Pasha was cruel and was responsible for the emigration of many Iraqi Jews. After Dauod's death in 1851, Jewish involvement in commerce and politics increased, with religious influence also transforming. The Iraqi Jewish community introduced the ''Hakham Bashi'', or Chief Rabbinate, in 1849, with Hakham Ezra Dangoor leading the community. The chief rabbi was also president of the community and was assisted by a lay council, a religious court, and a schools committee.

Sassanid period

The Persian people were now again to make their influence felt in the history of the world.Ardashir I

Ardashir I (Middle Persian: 𐭠𐭥𐭲𐭧𐭱𐭲𐭥, Modern Persian: , '), also known as Ardashir the Unifier (180–242 AD), was the founder of the Sasanian Empire. He was also Ardashir V of the Kings of Persis, until he founded the new ...

destroyed the rule of the Arsacids in the winter of 226, and founded the illustrious dynasty of the Sassanids

The Sasanian () or Sassanid Empire, officially known as the Empire of Iranians (, ) and also referred to by historians as the Neo-Persian Empire, was the History of Iran, last Iranian empire before the early Muslim conquests of the 7th-8th cen ...

. Different from the Parthian rulers, who were northern Iranians following Mithraism and Zoroastrianism

Zoroastrianism is an Iranian religion and one of the world's oldest organized faiths, based on the teachings of the Iranian-speaking prophet Zoroaster. It has a dualistic cosmology of good and evil within the framework of a monotheistic ont ...

and speaking Pahlavi dialect, the Sassanids intensified nationalism and established a state-sponsored Zoroastrian church which often suppressed dissident factions and heterodox views. Under the Sassanids, Babylonia became the province of Asuristan, with its main city, Ctesiphon, becoming the capital of the Sassanid Empire.

Shapur I

Shapur I (also spelled Shabuhr I; pal, 𐭱𐭧𐭯𐭥𐭧𐭥𐭩, Šābuhr ) was the second Sasanian King of Kings of Iran. The dating of his reign is disputed, but it is generally agreed that he ruled from 240 to 270, with his father Ar ...

(Shvor Malka, which is the Aramaic form of the name) was a friend to the Jews. His friendship with Shmuel gained many advantages for the Jewish community.

Shapur II

Shapur II ( pal, 𐭱𐭧𐭯𐭥𐭧𐭥𐭩 ; New Persian: , ''Šāpur'', 309 – 379), also known as Shapur the Great, was the tenth Sasanian Empire, Sasanian King of Kings (Shahanshah) of Iran. The List of longest-reigning monarchs, longest ...

's mother was Jewish, and this gave the Jewish community a relative freedom of religion and many advantages. Shapur was also the friend of a Babylonian rabbi in the Talmud

The Talmud (; he, , Talmūḏ) is the central text of Rabbinic Judaism and the primary source of Jewish religious law ('' halakha'') and Jewish theology. Until the advent of modernity, in nearly all Jewish communities, the Talmud was the cen ...

called Raba, and Raba's friendship with Shapur II enabled him to secure a relaxation of the oppressive laws enacted against the Jews in the Persian Empire. In addition, Raba sometimes referred to his top student Abaye with the term Shvur Malka meaning "Shapur heKing" because of his bright and quick intellect.

Christians, Manicheans, Buddhists

Buddhism ( , ), also known as Buddha Dharma and Dharmavinaya (), is an Indian religion or philosophical tradition based on teachings attributed to the Buddha. It originated in northern India as a -movement in the 5th century BCE, and g ...

and Jews at first seemed at a disadvantage, especially under Sassanian high-priest Kartir

Kartir (also spelled Karder, Karter and Kerdir; Middle Persian: 𐭪𐭫𐭲𐭩𐭫 ''Kardīr'') was a powerful and influential Zoroastrian priest during the reigns of four Sasanian kings in the 3rd-century. His name is cited in the inscriptions ...

; but the Jews, dwelling in more compact masses in cities like Isfahan, were not exposed to such general discrimination as broke out against the more isolated Christians.

Islamic Arab period

The first legal expression of Islam toward the Jews,Christians

Christians () are people who follow or adhere to Christianity, a monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus Christ. The words ''Christ'' and ''Christian'' derive from the Koine Greek title ''Christós'' (Χρι ...

, and Zoroastrians after the conquests of the 630s were the poll-tax ("jizyah

Jizya ( ar, جِزْيَة / ) is a per capita yearly taxation historically levied in the form of financial charge on dhimmis, that is, permanent non-Muslim subjects of a state governed by Islamic law. The jizya tax has been understood in ...

"), the tax upon real estate ("kharaj

Kharāj ( ar, خراج) is a type of individual Islamic tax on agricultural land and its produce, developed under Islamic law.

With the first Muslim conquests in the 7th century, the ''kharaj'' initially denoted a lump-sum duty levied upon the ...

") was instituted. The first caliph

A caliphate or khilāfah ( ar, خِلَافَة, ) is an institution or public office under the leadership of an Islamic steward with the title of caliph (; ar, خَلِيفَة , ), a person considered a political-religious successor to th ...

, Abu Bakr

Abu Bakr Abdallah ibn Uthman Abi Quhafa (; – 23 August 634) was the senior companion and was, through his daughter Aisha, a father-in-law of the Islamic prophet Muhammad, as well as the first caliph of Islam. He is known with the honori ...

, sent the famous warrior Khalid bin Al-Waleed against Iraq; and a Jew, by name Ka'ab al-Aḥbar

Kaʿb al-Aḥbār ( ar, كعب الأحبار, full name Abū Isḥāq Kaʿb ibn Maniʿ al-Ḥimyarī ( ar, ابو اسحاق كعب بن مانع الحميري) was a 7th-century Yemenite Jew from the Arab tribe of "Dhī Raʿīn" ( ar, ذي ر ...

, is said to have fortified the general with prophecies of success.

The Jews may have favored the advance of the Arabs, from whom they could expect mild treatment. Some such services it must have been that secured for the exilarch

The exilarch was the leader of the Jewish community in Persian Mesopotamia (modern day Iraq) during the era of the Parthians, Sasanians and Abbasid Caliphate up until the Mongol invasion of Baghdad in 1258, with intermittent gaps due to ongoin ...

Bostanai the favor of Umar I, who awarded to him for a wife the daughter of the conquered Sassanid Chosroes II as Theophanes and Abraham Zacuto narrate. Jewish records, as, for instance, "Seder ha-Dorot," contain a Bostanai legend which has many features in common with the account of the hero Mar Zutra II, already mentioned. The account, at all events, reveals that Bostanai, the founder of the succeeding exilarch dynasty, was a man of prominence, who received from the victorious Arab general certain high privileges, such as the right to wear a signet ring

A seal is a device for making an impression in wax, clay, paper, or some other medium, including an embossment on paper, and is also the impression thus made. The original purpose was to authenticate a document, or to prevent interference with ...

, a privilege otherwise limited to Muslims.

Omar and Othman were followed by Ali (656), with whom the Jews of Babylonia sided as against his rival Mu'awiyah. A Jewish preacher, Abdallah ibn Saba, of southern Arabia, who had embraced Islam, held forth in support of his new religion, expounded Mohammed's appearance in a Jewish sense. Ali made Kufa, in Iraq, his capital, and it was there that Jews expelled from the Arabian Peninsula went (about 641). It is perhaps owing to these immigrants that the Arabic language so rapidly gained ground among the Jews of Babylonia, although a greater portion of the population of Iraq were of Arab descent. The capture by Ali of Firuz Shabur, where 90,000 Jews are said to have dwelt, is mentioned by the Jewish chroniclers. Mar Isaac, chief of the Academy of Sura

A ''surah'' (; ar, سورة, sūrah, , ), is the equivalent of "chapter" in the Qur'an. There are 114 ''surahs'' in the Quran, each divided into '' ayats'' (verses). The chapters or ''surahs'' are of unequal length; the shortest surah ('' Al-K ...

, paid homage to the caliph, and received privileges from him.

The proximity of the court lent to the Jews of Babylonia a species of central position, as compared with the whole caliphate

A caliphate or khilāfah ( ar, خِلَافَة, ) is an institution or public office under the leadership of an Islamic steward with the title of caliph (; ar, خَلِيفَة , ), a person considered a political-religious successor to th ...

; so that Babylonia

Babylonia (; Akkadian: , ''māt Akkadī'') was an ancient Akkadian-speaking state and cultural area based in the city of Babylon in central-southern Mesopotamia (present-day Iraq and parts of Syria). It emerged as an Amorite-ruled state ...

still continued to be the focus of Jewish life. The time-honored institutions of the exilarchate and the gaonate—the heads of the academies attained great influence—constituted a kind of higher authority, voluntarily recognized by the whole Jewish diaspora. But unfortunately exilarch

The exilarch was the leader of the Jewish community in Persian Mesopotamia (modern day Iraq) during the era of the Parthians, Sasanians and Abbasid Caliphate up until the Mongol invasion of Baghdad in 1258, with intermittent gaps due to ongoin ...

s and geonim

''Geonim'' ( he, גאונים; ; also Romanization of Hebrew, transliterated Gaonim, singular Gaon) were the presidents of the two great Talmudic Academies in Babylonia, Babylonian Talmudic Academies of Sura Academy , Sura and Pumbedita Academy ...

only too soon began to rival each other. A certain Mar Yanḳa, closely allied to the exilarch, persecuted the rabbis of Pumbedita

Pumbedita (sometimes Pumbeditha, Pumpedita, or Pumbedisa; arc, פוּמְבְּדִיתָא ''Pūmbəḏīṯāʾ'', "The Mouth of the River,") was an ancient city located near the modern-day city of Fallujah, Iraq. It is known for having hosted t ...

so bitterly that several of them were compelled to flee to Sura, not to return until after their persecutor's death (about 730). "The exilarchate was for sale in the Arab period" (Ibn Daud); and centuries later, Sherira boasts that he was not descended from Bostanai. In Arabic legend, the resh galuta (ras al-galut) remained a highly important personage; one of them could see spirits; another is said to have been put to death under the last Umayyad caliph, Merwan ibn Mohammed (745–750).

The Umayyad caliph, Umar II

Umar ibn Abd al-Aziz ( ar, عمر بن عبد العزيز, ʿUmar ibn ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz; 2 November 680 – ), commonly known as Umar II (), was the eighth Umayyad caliph. He made various significant contributions and reforms to the society, an ...

. (717–720), persecuted the Jews. He issued orders to his governors: "Tear down no church, synagogue, or fire-temple; but permit no new ones to be built". Isaac Iskawi II (about 800) received from Harun al-Rashid (786–809) confirmation of the right to carry a seal of office. At the court of the mighty Harun appeared an embassy from the emperor Charlemagne, in which a Jew, Isaac, took part. Charles (possibly Charles the Bald

Charles the Bald (french: Charles le Chauve; 13 June 823 – 6 October 877), also known as Charles II, was a 9th-century king of West Francia (843–877), king of Italy (875–877) and emperor of the Carolingian Empire (875–877). After a s ...

) is said to have asked the "king of Babel" to send him a man of royal lineage; and in response the calif dispatched Rabbi Machir to him; this was the first step toward establishing communication between the Jews of Babylonia and European communities. Although it is said that the law requiring Jews to wear a yellow badge upon their clothing originated with Harun, and although the laws of Islam were stringently enforced by him to the detriment of the Jews, the magnificent development which Arabian culture underwent in his time must have benefited the Jews also; so that a scientific tendency began to make itself noticeable among the Babylonian Jews under Harun and his successors, especially under Al-Ma'mun (813–833).

Like the Arabs, the Jews were zealous promoters of knowledge, and by translating Greek and Latin authors, mainly at the House of Wisdom

The House of Wisdom ( ar, بيت الحكمة, Bayt al-Ḥikmah), also known as the Grand Library of Baghdad, refers to either a major Abbasid public academy and intellectual center in Baghdad or to a large private library belonging to the Abba ...

in Baghdad, contributed essentially to their preservation. They took up religio-philosophical studies (the "kalam

''ʿIlm al-Kalām'' ( ar, عِلْم الكَلام, literally "science of discourse"), usually foreshortened to ''Kalām'' and sometimes called "Islamic scholastic theology" or "speculative theology", is the philosophical study of Islamic doc ...

"), siding generally with the Mutazilites and maintaining the freedom of the human will (" chadr"). The government meanwhile accomplished all it could toward the complete humiliation of the Jews. All non-believers—Magi, Jews, and Christians—were compelled by Al-Mutawakkil to wear a badge; their places of worship were confiscated and turned into mosques; they were excluded from public offices, and compelled to pay to the caliph a tax of one-tenth of the value of their houses. The caliph Al-Mu'tadhel (892–902) ranked the Jews as "state servants."

In the 7th century, the new Muslim rulers institute the kharaj

Kharāj ( ar, خراج) is a type of individual Islamic tax on agricultural land and its produce, developed under Islamic law.

With the first Muslim conquests in the 7th century, the ''kharaj'' initially denoted a lump-sum duty levied upon the ...

land tax, which led to mass migration of Babylonian Jews from the countryside to cities like Baghdad

Baghdad (; ar, بَغْدَاد , ) is the capital of Iraq and the second-largest city in the Arab world after Cairo. It is located on the Tigris near the ruins of the ancient city of Babylon and the Sassanid Persian capital of Ctesipho ...

. This in turn led to greater wealth and international influence, as well as a more cosmopolitan outlook from Jewish thinkers such as Saadiah Gaon, who now deeply engaged with Western philosophy for the first time. When the Abbasid Caliphate

The Abbasid Caliphate ( or ; ar, الْخِلَافَةُ الْعَبَّاسِيَّة, ') was the third caliphate to succeed the Islamic prophet Muhammad. It was founded by a dynasty descended from Muhammad's uncle, Abbas ibn Abdul-Mutta ...

and the city of Baghdad

Baghdad (; ar, بَغْدَاد , ) is the capital of Iraq and the second-largest city in the Arab world after Cairo. It is located on the Tigris near the ruins of the ancient city of Babylon and the Sassanid Persian capital of Ctesipho ...

declined in the 10th century, many Babylonian Jews migrated to the Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on th ...

region, contributing to the spread of Babylonian Jewish customs throughout the Jewish world.

Mongol period

The Caliphate hastened to its end before the rising power of theMongol Empire

The Mongol Empire of the 13th and 14th centuries was the largest contiguous land empire in history. Originating in present-day Mongolia in East Asia, the Mongol Empire at its height stretched from the Sea of Japan to parts of Eastern Europe ...

. As Bar Hebræus

Gregory Bar Hebraeus ( syc, ܓܪܝܓܘܪܝܘܣ ܒܪ ܥܒܪܝܐ, b. 1226 - d. 30 July 1286), known by his Syriac ancestral surname as Bar Ebraya or Bar Ebroyo, and also by a Latinisation of names, Latinized name Abulpharagius, was an Aramean Map ...

remarks, these Mongol tribes knew no distinction between heathens, Jews, and Christians; and their Great Khan Kublai Khan

Kublai ; Mongolian script: ; (23 September 1215 – 18 February 1294), also known by his temple name as the Emperor Shizu of Yuan and his regnal name Setsen Khan, was the founder of the Yuan dynasty of China and the fifth khagan-emperor of the ...

showed himself just toward the Jews who served in his army, as reported by Marco Polo.

Hulagu (a Buddhist), the destroyer of the Caliphate (1258) and the conqueror of Palestine (1260), was tolerant toward Muslims, Jews and Christians; but there can be no doubt that in those days of terrible warfare the Jews must have suffered much with others. Under the Mongolian rulers, the priests of all religions were exempt from the poll-tax. Hulagu's second son, Aḥmed, embraced Islam, but his successor, Arghun

Arghun Khan ( Mongolian Cyrillic: ''Аргун хан''; Traditional Mongolian: ; c. 1258 – 10 March 1291) was the fourth ruler of the Mongol empire's Ilkhanate, from 1284 to 1291. He was the son of Abaqa Khan, and like his father, was a d ...

(1284–91), hated the Muslims and was friendly to Jews and Christians; his chief counselor was a Jew, Sa'ad al-Dawla

Saʿd al-Dawla ibn Ṣafī ibn Hibatullāh ibn Muhassib al-Dawla al-Abharī ( ar, سعد الدولة بن هبة الله بن محاسب ابهري) (c. 1240 – March 5, 1291) was a Jewish physician and statesman in thirteenth-century Persi ...

, a physician of Baghdad.

It proved a false dawn. The power of Sa’ad al-Dawla was so vexatious to the Muslim population the churchman Bar Hebraeus

Gregory Bar Hebraeus ( syc, ܓܪܝܓܘܪܝܘܣ ܒܪ ܥܒܪܝܐ, b. 1226 - d. 30 July 1286), known by his Syriac ancestral surname as Bar Ebraya or Bar Ebroyo, and also by a Latinized name Abulpharagius, was an Aramean Maphrian (regional prim ...

wrote so “were the Muslims reduced to having a Jew in the place of honor.” This was exacerbated by Sa’d al-Dawla, who ordered no Muslim be employed by the official bureaucracy. He was also known as a fearsome tax collection and rumours swirled he was planning to create a new religion of which Arghun was supposed to be the prophet. Sa’d al-Dawla was murdered two days before the death of his Arghun, then stricken by illness, by his enemies in court.

After the death of the great khan and the murder of his Jewish favorite, the Muslims fell upon the Jews, and Baghdad witnessed a regular battle between them. Gaykhatu

Gaykhatu (Mongolian script:; ) was the fifth Ilkhanate ruler in Iran. He reigned from 1291 to 1295. His Buddhist baghshi gave him the Tibetan name Rinchindorj () which appeared on his paper money.

Early life

He was born to Abaqa and Nukdan K ...

also had a Jewish minister of finance, Reshid al-Dawla. The khan Ghazan

Mahmud Ghazan (5 November 1271 – 11 May 1304) (, Ghazan Khan, sometimes archaically spelled as Casanus by the Westerners) was the seventh ruler of the Mongol Empire's Ilkhanate division in modern-day Iran from 1295 to 1304. He was the son of A ...

also became a Muslim, and made the Jews second class citizens. The Egyptian sultan Naṣr, who also ruled over Iraq, reestablished the same law in 1330, and saddled it with new limitations. During this period attacks on Jews greatly increased. The situation grew dire for the Jewish community as Muslim chronicler Abbas al-’Azzawi recorded:

“These events which befell the Jews after they had attained a high standing in the state caused them to lower their voices. ince thenwe have not heard from them anything worthy of recording because they were prevented from participation in its government and politics. They were neglected and their voice was only heard gain

Gain or GAIN may refer to:

Science and technology

* Gain (electronics), an electronics and signal processing term

* Antenna gain

* Gain (laser), the amplification involved in laser emission

* Gain (projection screens)

* Information gain in d ...

after a long time.”

Baghdad, reduced in importance, ravaged by wars and invasions, was eclipsed as the commercial and political centre of the Arab world. The Jewish community, shuttered out of political life, were reduced too and the status of the Exilarch

The exilarch was the leader of the Jewish community in Persian Mesopotamia (modern day Iraq) during the era of the Parthians, Sasanians and Abbasid Caliphate up until the Mongol invasion of Baghdad in 1258, with intermittent gaps due to ongoin ...

and the Rabbis of the city diminished. Great numbers of Jews began to depart, seeking tranquility elsewhere in the Middle East beyond a now troubled frontier.

Mongolian fury once again devastated the localities inhabited by Jews, when, in 1393, Timur

Timur ; chg, ''Aqsaq Temür'', 'Timur the Lame') or as ''Sahib-i-Qiran'' ( 'Lord of the Auspicious Conjunction'), his epithet. ( chg, ''Temür'', 'Iron'; 9 April 133617–19 February 1405), later Timūr Gurkānī ( chg, ''Temür Kür ...

captured Baghdad, Wasit, Hilla

Hillah ( ar, ٱلْحِلَّة ''al-Ḥillah''), also spelled Hilla, is a city in central Iraq on the Hilla branch of the Euphrates River, south of Baghdad. The population is estimated at 364,700 in 1998. It is the capital of Babylon Province ...

, Basra