Anti-semitism on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

In 1879, German journalist

In 1879, German journalist

Bernard Lewis defined antisemitism as a special case of prejudice, hatred, or persecution directed against people who are in some way different from the rest. According to Lewis, antisemitism is marked by two distinct features: Jews are judged according to a standard different from that applied to others, and they are accused of "cosmic evil." Thus, "it is perfectly possible to hate and even to persecute Jews without necessarily being anti-Semitic" unless this hatred or persecution displays one of the two features specific to antisemitism. Lewis, Bernard

Bernard Lewis defined antisemitism as a special case of prejudice, hatred, or persecution directed against people who are in some way different from the rest. According to Lewis, antisemitism is marked by two distinct features: Jews are judged according to a standard different from that applied to others, and they are accused of "cosmic evil." Thus, "it is perfectly possible to hate and even to persecute Jews without necessarily being anti-Semitic" unless this hatred or persecution displays one of the two features specific to antisemitism. Lewis, Bernard

"The New Anti-Semitism"

, ''The American Scholar'', Volume 75 No. 1, Winter 2006, pp. 25–36. The paper is based on a lecture delivered at Brandeis University on 24 March 2004. There have been a number of efforts by international and governmental bodies to define antisemitism formally. The United States Department of State states that "while there is no universally accepted definition, there is a generally clear understanding of what the term encompasses." For the purposes of its 2005 Report on Global Anti-Semitism, the term was considered to mean "hatred toward Jews—individually and as a group—that can be attributed to the Jewish religion and/or ethnicity.""Report on Global Anti-Semitism"

,

Antisemitism manifests itself in a variety of ways.

Antisemitism manifests itself in a variety of ways.

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who holds such positions is called an antisemite. Antisemitism is considered to be a form of racism.

Antisemitism has historically been manifested in many ways, ranging from expressions of

"The New Anti-Semitism"

, ''The American Scholar'', Volume 75 No. 1, Winter 2006, pp. 25–36. The paper is based on a lecture delivered at Brandeis University on 24 March 2004.

The origin of "antisemitic" terminologies is found in the responses of

The origin of "antisemitic" terminologies is found in the responses of

theories concerning race, civilization, and "progress" had become quite widespread in Europe in the second half of the 19th century, especially as Prussian nationalistic historian Heinrich von Treitschke did much to promote this form of racism. He coined the phrase "the Jews are our misfortune" which would later be widely used by Nazism, Nazis. According to Avner Falk, Treitschke uses the term "Semitic" almost synonymously with "Jewish", in contrast to Renan's use of it to refer to a whole range of peoples, based generally on linguistic criteria.

According to Jonathan M. Hess, the term was originally used by its authors to "stress the radical difference between their own 'antisemitism' and earlier forms of antagonism toward Jews and Judaism."

hatred

Hatred is an intense negative emotional response towards certain people, things or ideas, usually related to opposition or revulsion toward something. Hatred is often associated with intense feelings of anger, contempt, and disgust. Hatred is s ...

of or discrimination against individual Jews to organized pogroms by mobs, police forces, or genocide. Although the term did not come into common usage until the 19th century, it is also applied to previous and later anti-Jewish incidents. Notable instances of persecution

Persecution is the systematic mistreatment of an individual or group by another individual or group. The most common forms are religious persecution, racism, and political persecution, though there is naturally some overlap between these term ...

include the Rhineland massacres preceding the First Crusade in 1096, the Edict of Expulsion from England in 1290, the 1348–1351 persecution of Jews during the Black Death

There were a series of violent attacks, massacres and mass persecutions of Jews during the Black Death. Jewish communities were falsely blamed for outbreaks of the Black Death in Europe. Violence were committed from 1348 to 1351 in Toulon, Barcelo ...

, the massacres of Spanish Jews in 1391, the persecutions of the Spanish Inquisition, the expulsion from Spain Expulsion from Spain may refer to:

*Expulsion of Jews from Spain (1492 in Aragon and Castile, 1497–98 in Navarre)

*Expulsion of the Moriscos (1609–1614)

See also

*Forced conversions of Muslims in Spain

The forced conversions of Muslims in ...

in 1492, the Cossack massacres in Ukraine from 1648 to 1657, various anti-Jewish pogroms in the Russian Empire

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who holds such positions is called an antisemite. Antisemitism is considered to be a form of racism.

Antis ...

between 1821 and 1906, the 1894–1906 Dreyfus affair in France, the Holocaust in German-occupied Europe

German-occupied Europe refers to the sovereign countries of Europe which were wholly or partly occupied and civil-occupied (including puppet governments) by the military forces and the government of Nazi Germany at various times between 1939 an ...

during World War II and Soviet anti-Jewish policies. Though historically most manifestations of antisemitism have taken place in Christian Europe since the early 20th century antisemitism has increased in the Middle East.

The root word '' Semite'' gives the false impression

''False Impression'' is a mystery novel by English author Jeffrey Archer, first published in February 2005 by Macmillan (). The novel was published in several countries.

Plot summary

''False Impression'' concerns an international journey thro ...

that antisemitism is directed against all Semitic people, e.g., including Arabs, Assyrians

Assyrian may refer to:

* Assyrian people, the indigenous ethnic group of Mesopotamia.

* Assyria, a major Mesopotamian kingdom and empire.

** Early Assyrian Period

** Old Assyrian Period

** Middle Assyrian Empire

** Neo-Assyrian Empire

* Assyrian ...

, and Arameans

The Arameans ( oar, 𐤀𐤓𐤌𐤉𐤀; arc, 𐡀𐡓𐡌𐡉𐡀; syc, ܐܪ̈ܡܝܐ, Ārāmāyē) were an ancient Semitic-speaking people in the Near East, first recorded in historical sources from the late 12th century BCE. The Aramean ...

. The compound word ('antisemitism') was first used in print in Germany in 1879 as a scientific-sounding term for ('Jew-hatred'), and this has been its common use since then.. Extract from ''Islam in History: Ideas, Men and Events in the Middle East'', The Library Press, 1973.

* Lewis, Bernard"The New Anti-Semitism"

, ''The American Scholar'', Volume 75 No. 1, Winter 2006, pp. 25–36. The paper is based on a lecture delivered at Brandeis University on 24 March 2004.

Origin and usage

Etymology

The origin of "antisemitic" terminologies is found in the responses of

The origin of "antisemitic" terminologies is found in the responses of Moritz Steinschneider

Moritz Steinschneider (30 March 1816, Prostějov, Moravia, Austrian Empire – 24 January 1907, Berlin) was a Moravian bibliographer and Orientalist. He received his early instruction in Hebrew from his father, Jacob Steinschneider ( 1782; ...

to the views of Ernest Renan

Joseph Ernest Renan (; 27 February 18232 October 1892) was a French Orientalist and Semitic scholar, expert of Semitic languages and civilizations, historian of religion, philologist, philosopher, biblical scholar, and critic. He wrote influe ...

. As Alex Bein writes: "The compound anti-Semitism appears to have been used first by Steinschneider, who challenged Renan on account of his 'anti-Semitic prejudices' race">Race_(human_categorization).html" ;"title=".e., his derogation of the "Semites" as a race" Avner Falk">Race (human categorization)">race">Race_(human_categorization).html" ;"title=".e., his derogation of the "Semites" as a Race (human categorization)">race" Avner Falk similarly writes: "The German word ''antisemitisch'' was first used in 1860 by the Austrian Jewish scholar Moritz Steinschneider (1816–1907) in the phrase ''antisemitische Vorurteile'' (antisemitic prejudices). Steinschneider used this phrase to characterise the French philosopher Ernest Renan's false ideas about how ' Semitic races' were inferior to 'Aryan race">Semitic Race">Semitic races' were inferior to 'Aryan races'".

Pseudoscience">Pseudoscientific

Pseudoscience consists of statements, beliefs, or practices that claim to be both scientific and factual but are incompatible with the scientific method. Pseudoscience is often characterized by contradictory, exaggerated or unfalsifiable claim ... In 1879, German journalist

In 1879, German journalist Wilhelm Marr

Friedrich Wilhelm Adolph Marr (November 16, 1819 – July 17, 1904) was a German agitator and journalist, who popularized the term "antisemitism" (1881) hich was invented by Moritz Steinschneider

Life

Marr was born in Magdeburg as the only son ...

published a pamphlet, ''Der Sieg des Judenthums über das Germanenthum. Vom nicht confessionellen Standpunkt aus betrachtet'' (''The Victory of the Jewish Spirit over the Germanic Spirit. Observed from a non-religious perspective'') in which he used the word ''Semitismus'' interchangeably with the word ''Judentum'' to denote both "Jewry" (the Jews as a collective) and "jewishness" (the quality of being Jewish, or the Jewish spirit).

This use of '' Semitismus'' was followed by a coining of " Antisemitismus" which was used to indicate opposition to the Jews as a people and opposition to the Jewish spirit, which Marr interpreted as infiltrating German culture. His next pamphlet, ''Der Weg zum Siege des Germanenthums über das Judenthum'' (''The Way to Victory of the Germanic Spirit over the Jewish Spirit'', 1880), presents a development of Marr's ideas further and may present the first published use of the German word '' Antisemitismus'', "antisemitism".

The pamphlet became very popular, and in the same year he founded the ''Antisemiten-Liga'' (League of Antisemites), apparently named to follow the "Anti-Kanzler-Liga" (Anti-Chancellor League). The league was the first German organization committed specifically to combating the alleged threat to Germany and German culture posed by the Jews and their influence and advocating their forced removal from the country.

So far as can be ascertained, the word was first widely printed in 1881, when Marr published ''Zwanglose Antisemitische Hefte'', and Wilhelm Scherer used the term ''Antisemiten'' in the January issue of '' Neue Freie Presse''.

The ''Jewish Encyclopedia

''The Jewish Encyclopedia: A Descriptive Record of the History, Religion, Literature, and Customs of the Jewish People from the Earliest Times to the Present Day'' is an English-language encyclopedia containing over 15,000 articles on th ...

'' reports, "In February 1881, a correspondent of the '' Allgemeine Zeitung des Judentums'' speaks of 'Anti-Semitism' as a designation which recently came into use ("Allg. Zeit. d. Jud." 1881, p. 138). On 19 July 1882, the editor says, 'This quite recent Anti-Semitism is hardly three years old.'"

The word "antisemitism" was borrowed into English from German in 1881. '' Oxford English Dictionary'' editor James Murray wrote that it was not included in the first edition because "Anti-Semite and its family were then probably very new in English use, and not thought likely to be more than passing nonce-words... Would that anti-Semitism had had no more than a fleeting interest!" The related term " philosemitism" was used by 1881.

Usage

From the outset the term "anti-Semitism" bore special racial connotations and meant specifically prejudice against Jews. The term is confusing, for in modern usage 'Semitic' designates a language group, not a race. In this sense, the term is a misnomer, since there are many speakers of Semitic languages (e.g. Arabs, Ethiopians, andArameans

The Arameans ( oar, 𐤀𐤓𐤌𐤉𐤀; arc, 𐡀𐡓𐡌𐡉𐡀; syc, ܐܪ̈ܡܝܐ, Ārāmāyē) were an ancient Semitic-speaking people in the Near East, first recorded in historical sources from the late 12th century BCE. The Aramean ...

) who are not the objects of antisemitic prejudices, while there are many Jews who do not speak Hebrew, a Semitic language. Though 'antisemitism' could be construed as prejudice against people who speak other Semitic languages, this is not how the term is commonly used.

The term may be spelled with or without a hyphen (antisemitism or anti-Semitism). Many scholars and institutions favor the unhyphenated form. Shmuel Almog argued, "If you use the hyphenated form, you consider the words 'Semitism', 'Semite', 'Semitic' as meaningful ... antisemitic parlance, 'Semites' really stands for Jews, just that.", SICSA Report: Newsletter of the Vidal Sassoon International Center for the Study of Antisemitism (Summer 1989). Emil Fackenheim supported the unhyphenated spelling, in order to " ispelthe notion that there is an entity 'Semitism' which 'anti-Semitism' opposes." Others endorsing an unhyphenated term for the same reason include the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance, historian Deborah Lipstadt, Padraic O'Hare, professor of Religious and Theological Studies and Director of the Center for the Study of Jewish-Christian-Muslim Relations at Merrimack College; and historians Yehuda Bauer and James Carroll. According to Carroll, who first cites O'Hare and Bauer on "the existence of something called 'Semitism'", "the hyphenated word thus reflects the bipolarity that is at the heart of the problem of antisemitism".

Definition

Though the general definition of antisemitism is hostility or prejudice against Jews, and, according to Olaf Blaschke, has become an "umbrella term for negative stereotypes about Jews", a number of authorities have developed more formal definitions. Holocaust scholar andCity University of New York

The City University of New York ( CUNY; , ) is the Public university, public university system of Education in New York City, New York City. It is the largest urban university system in the United States, comprising 25 campuses: eleven Upper divis ...

professor Helen Fein defines it as "a persisting latent structure of hostile beliefs towards Jews as a collective manifested in individuals as attitudes, and in culture as myth, ideology, folklore and imagery, and in actions—social or legal discrimination, political mobilization against the Jews, and collective or state violence—which results in and/or is designed to distance, displace, or destroy Jews as Jews."

Elaborating on Fein's definition, Dietz Bering of the University of Cologne writes that, to antisemites, "Jews are not only partially but totally bad by nature, that is, their bad traits are incorrigible. Because of this bad nature: (1) Jews have to be seen not as individuals but as a collective. (2) Jews remain essentially alien in the surrounding societies. (3) Jews bring disaster on their 'host societies' or on the whole world, they are doing it secretly, therefore the anti-Semites feel obliged to unmask the conspiratorial, bad Jewish character."

For Sonja Weinberg, as distinct from economic and religious anti-Judaism

Anti-Judaism is the "total or partial opposition to Judaism as a religion—and the total or partial opposition to Jews as adherents of it—by persons who accept a competing system of beliefs and practices and consider certain genuine Judai ...

, antisemitism in its modern form shows conceptual innovation, a resort to 'science' to defend itself, new functional forms, and organisational differences. It was anti-liberal, racialist and nationalist. It promoted the myth that Jews conspired to 'judaise' the world; it served to consolidate social identity; it channeled dissatisfactions among victims of the capitalist system; and it was used as a conservative cultural code to fight emancipation and liberalism.

Bernard Lewis defined antisemitism as a special case of prejudice, hatred, or persecution directed against people who are in some way different from the rest. According to Lewis, antisemitism is marked by two distinct features: Jews are judged according to a standard different from that applied to others, and they are accused of "cosmic evil." Thus, "it is perfectly possible to hate and even to persecute Jews without necessarily being anti-Semitic" unless this hatred or persecution displays one of the two features specific to antisemitism. Lewis, Bernard

Bernard Lewis defined antisemitism as a special case of prejudice, hatred, or persecution directed against people who are in some way different from the rest. According to Lewis, antisemitism is marked by two distinct features: Jews are judged according to a standard different from that applied to others, and they are accused of "cosmic evil." Thus, "it is perfectly possible to hate and even to persecute Jews without necessarily being anti-Semitic" unless this hatred or persecution displays one of the two features specific to antisemitism. Lewis, Bernard"The New Anti-Semitism"

, ''The American Scholar'', Volume 75 No. 1, Winter 2006, pp. 25–36. The paper is based on a lecture delivered at Brandeis University on 24 March 2004. There have been a number of efforts by international and governmental bodies to define antisemitism formally. The United States Department of State states that "while there is no universally accepted definition, there is a generally clear understanding of what the term encompasses." For the purposes of its 2005 Report on Global Anti-Semitism, the term was considered to mean "hatred toward Jews—individually and as a group—that can be attributed to the Jewish religion and/or ethnicity.""Report on Global Anti-Semitism"

,

U.S. State Department

The United States Department of State (DOS), or State Department, is an executive department of the U.S. federal government responsible for the country's foreign policy and relations. Equivalent to the ministry of foreign affairs of other nati ...

, 5 January 2005.

In 2005, the European Monitoring Centre on Racism and Xenophobia (now Fundamental Rights Agency), then an agency of the European Union, developed a more detailed working definition, which states: "Antisemitism is a certain perception of Jews, which may be expressed as hatred toward Jews. Rhetorical and physical manifestations of antisemitism are directed toward Jewish or non-Jewish individuals and/or their property, toward Jewish community institutions and religious facilities." It also adds that "such manifestations could also target the state of Israel, conceived as a Jewish collectivity," but that "criticism of Israel similar to that leveled against any other country cannot be regarded as antisemitic." It provides contemporary examples of ways in which antisemitism may manifest itself, including promoting the harming of Jews in the name of an ideology or religion; promoting negative stereotypes of Jews; holding Jews collectively responsible for the actions of an individual Jewish person or group; denying the Holocaust or accusing Jews or Israel of exaggerating it; and accusing Jews of dual loyalty

In politics, dual loyalty is loyalty to two separate interests that potentially conflict with each other, leading to a conflict of interest.

Inherently controversial

While nearly all examples of alleged "dual loyalty" are considered highly contr ...

or a greater allegiance to Israel than their own country. It also lists ways in which attacking Israel could be antisemitic, and states that denying the Jewish people their right to self-determination, e.g. by claiming that the existence of a state of Israel is a racist endeavor, can be a manifestation of antisemitism—as can applying double standards by requiring of Israel a behavior not expected or demanded of any other democratic nation, or holding Jews collectively responsible for the actions of the State of Israel.

The definition has been adopted by the European Parliament Working Group on Antisemitism, in 2010 it was adopted by the United States Department of State, in 2014 it was adopted in the Operational Hate Crime Guidance of the UK College of Policing and was also adopted by the Campaign Against Antisemitism. In 2016, the definition was adopted by the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance. The Working Definition of Antisemitism is among the most controversial documents related to opposition to antisemitism, and critics argue that it has been used to censor criticism of Israel.

Evolution of usage

In 1879,Wilhelm Marr

Friedrich Wilhelm Adolph Marr (November 16, 1819 – July 17, 1904) was a German agitator and journalist, who popularized the term "antisemitism" (1881) hich was invented by Moritz Steinschneider

Life

Marr was born in Magdeburg as the only son ...

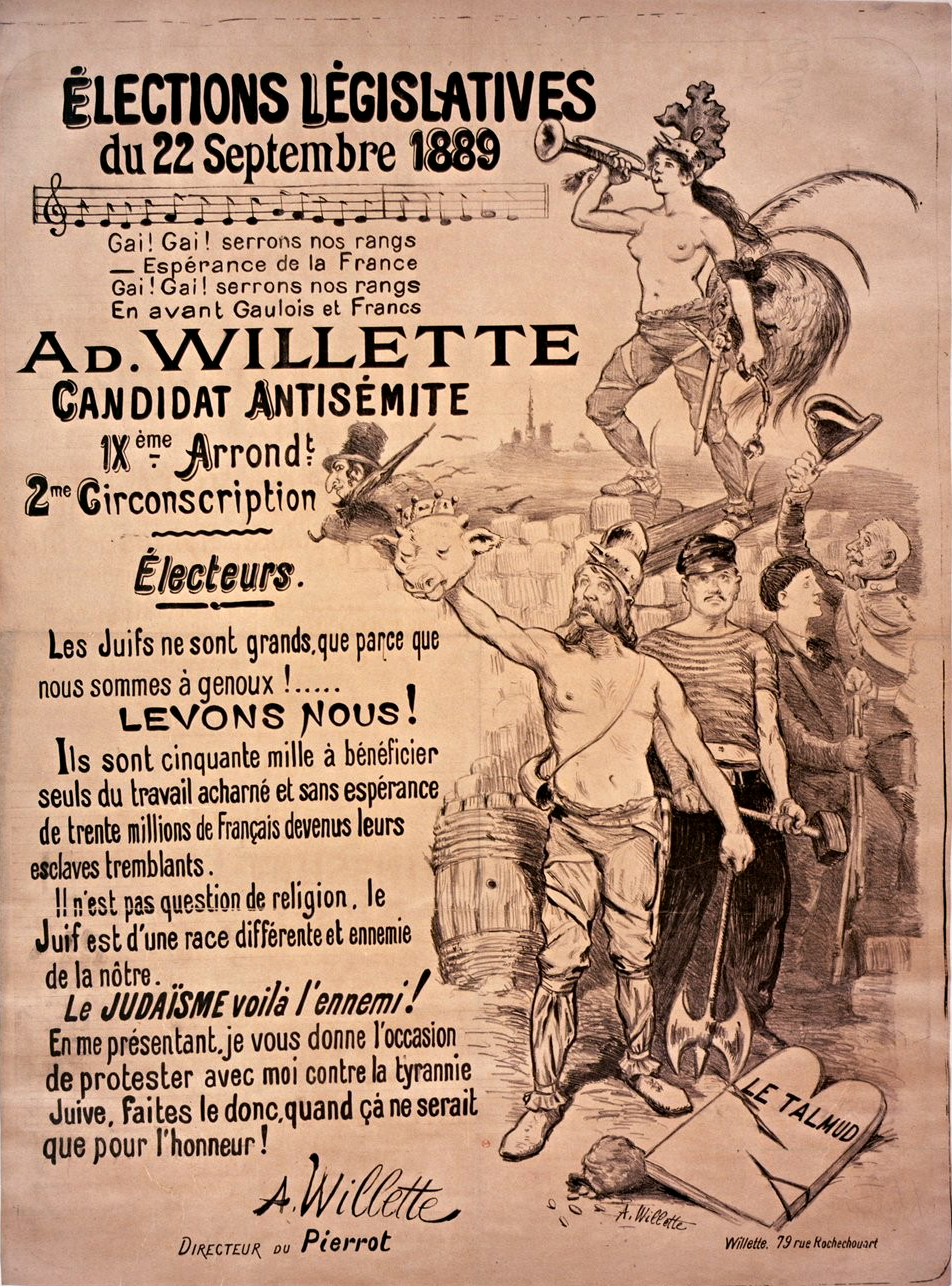

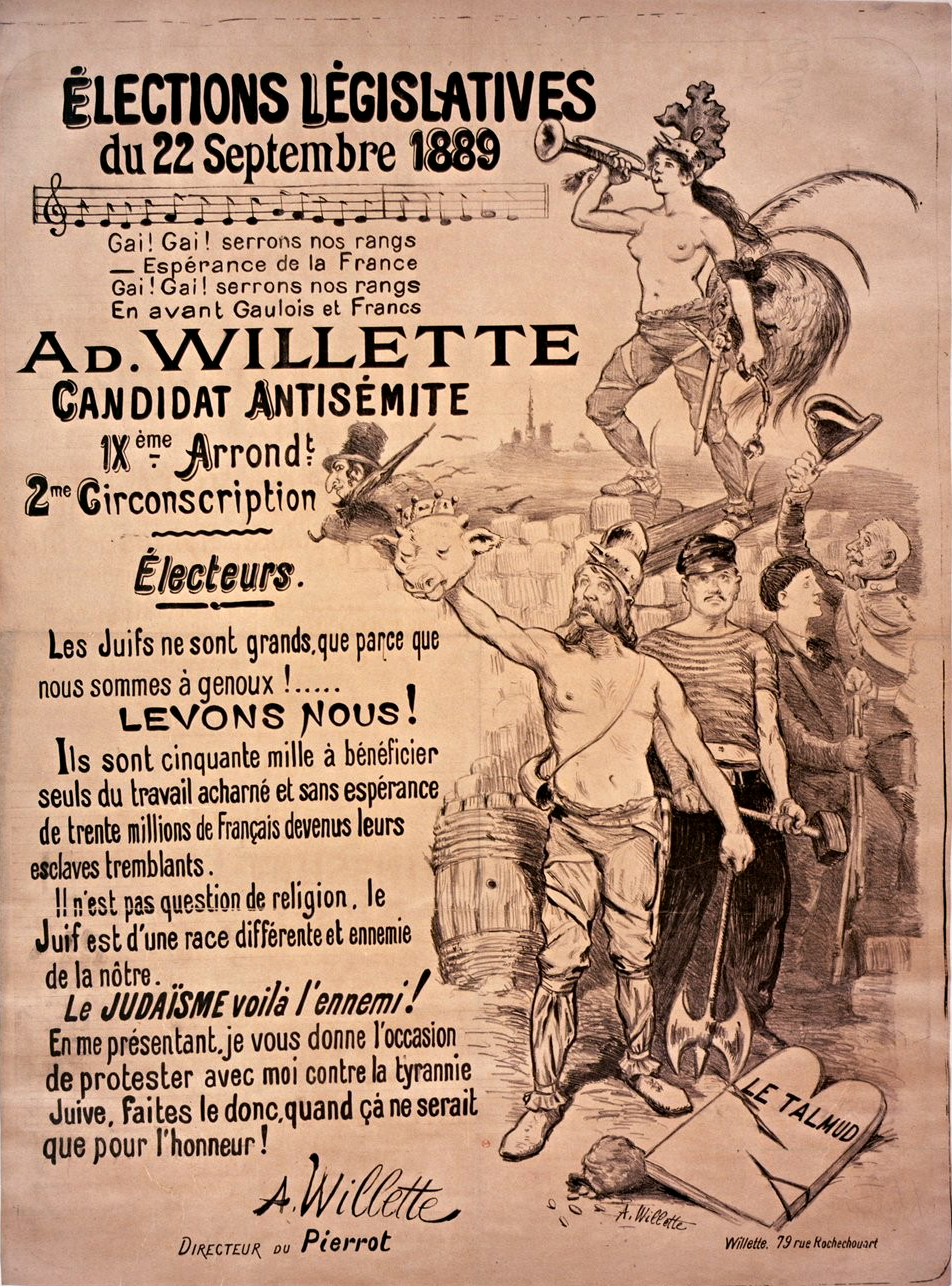

founded the ''Antisemiten-Liga'' (Anti-Semitic League). Identification with antisemitism and as an antisemite was politically advantageous in Europe during the late 19th century. For example, Karl Lueger

Karl Lueger (; 24 October 1844 – 10 March 1910) was an Austrian politician, mayor of Vienna, and leader and founder of the Austrian Christian Social Party. He is credited with the transformation of the city of Vienna into a modern city. The pop ...

, the popular mayor of fin de siècle Vienna, skillfully exploited antisemitism as a way of channeling public discontent to his political advantage. In its 1910 obituary of Lueger, ''The New York Times'' notes that Lueger was "Chairman of the Christian Social Union of the Parliament and of the Anti-Semitic Union of the Diet of Lower Austria. In 1895, A. C. Cuza organized the ''Alliance Anti-semitique Universelle'' in Bucharest. In the period before World War II, when animosity towards Jews was far more commonplace, it was not uncommon for a person, an organization, or a political party to self-identify as an antisemite or antisemitic.

The early Zionist pioneer Leon Pinsker, a professional physician, preferred the clinical-sounding term ''Judeophobia'' to antisemitism, which he regarded as a misnomer. The word ''Judeophobia'' first appeared in his pamphlet " Auto-Emancipation", published anonymously in German in September 1882, where it was described as an irrational fear or hatred of Jews. According to Pinsker, this irrational fear was an inherited predisposition.

In the aftermath of the Kristallnacht pogrom in 1938, German propaganda minister Goebbels

Paul Joseph Goebbels (; 29 October 1897 – 1 May 1945) was a German Nazi politician who was the ''Gauleiter'' (district leader) of Berlin, chief propagandist for the Nazi Party, and then Reich Minister of Propaganda from 1933 to 19 ...

announced: "The German people is anti-Semitic. It has no desire to have its rights restricted or to be provoked in the future by parasites of the Jewish race."

After 1945 victory of the Allies over Nazi Germany, and particularly after the full extent of the Nazi genocide against the Jews became known, the term ''antisemitism'' acquired pejorative connotations. This marked a full circle shift in usage, from an era just decades earlier when "Jew" was used as a pejorative term. Yehuda Bauer wrote in 1984: "There are no anti-Semites in the world ... Nobody says, 'I am anti-Semitic.' You cannot, after Hitler. The word has gone out of fashion."

Eternalism–contextualism debate

The study of antisemitism has become politically controversial because of differing interpretations of the Holocaust and the Israeli–Palestinian conflict. There are two competing views of antisemitism, eternalism, and contextualism. The eternalist view sees antisemitism as separate from other forms of racism and prejudice and an exceptionalist, transhistorical force teleologically culminating in the Holocaust. Hannah Arendt criticized this approach, writing that it provoked "the uncomfortable question: 'Why the Jews of all people?' . . . with the question begging reply: Eternal hostility." Zionist thinkers and antisemites draw different conclusions from what they perceive as the eternal hatred of Jews; according to antisemites, it proves the inferiority of Jews, while for Zionists it means that Jews need their own state as a refuge. Most Zionists do not believe that antisemitism can be combatted with education or other means. The contextual approach treats antisemitism as a type of racism and focuses on the historical context in which hatred of Jews emerges. Some contextualists restrict the use of "antisemitism" to refer exclusively to the era of modern racism, treating anti-Judaism as a separate phenomenon. Historian David Engel has challenged the project to define antisemitism, arguing that it essentializes Jewish history as one of persecution and discrimination. Engel argues that the term "antisemitism" is not useful in historical analysis because it implies that there are links between anti-Jewish prejudices expressed in different contexts, without evidence of such a connection.Manifestations

Antisemitism manifests itself in a variety of ways.

Antisemitism manifests itself in a variety of ways. René König

René König (5 July 1906 – 21 March 1992) was a German sociologist. He was very influential on West German sociology after 1949.

Born in Magdeburg, he 1925 took up Philosophy, Psychology, Ethnology, and Islamic Studies at the Universities o ...

mentions social antisemitism, economic antisemitism, religious antisemitism, and political antisemitism as examples. König points out that these different forms demonstrate that the "origins of anti-Semitic prejudices are rooted in different historical periods." König asserts that differences in the chronology of different antisemitic prejudices and the irregular distribution of such prejudices over different segments of the population create "serious difficulties in the definition of the different kinds of anti-Semitism." These difficulties may contribute to the existence of different taxonomies that have been developed to categorize the forms of antisemitism. The forms identified are substantially the same; it is primarily the number of forms and their definitions that differ. Bernard Lazare identifies three forms of antisemitism: Christian antisemitism, economic antisemitism, and ethnologic antisemitism.

William Brustein names four categories: religious, racial, economic, and political. The Roman Catholic historian Edward Flannery distinguished four varieties of antisemitism:

*political and economic antisemitism, giving as examples Cicero and Charles Lindbergh;

* theological or religious antisemitism, sometimes known as anti-Judaism

Anti-Judaism is the "total or partial opposition to Judaism as a religion—and the total or partial opposition to Jews as adherents of it—by persons who accept a competing system of beliefs and practices and consider certain genuine Judai ...

;

*nationalistic antisemitism, citing Voltaire and other Enlightenment

Enlightenment or enlighten may refer to:

Age of Enlightenment

* Age of Enlightenment, period in Western intellectual history from the late 17th to late 18th century, centered in France but also encompassing (alphabetically by country or culture): ...

thinkers, who attacked Jews for supposedly having certain characteristics, such as greed and arrogance, and for observing customs such as kashrut

(also or , ) is a set of dietary laws dealing with the foods that Jewish people are permitted to eat and how those foods must be prepared according to Jewish law. Food that may be consumed is deemed kosher ( in English, yi, כּשר), fro ...

and Shabbat

Shabbat (, , or ; he, שַׁבָּת, Šabbāṯ, , ) or the Sabbath (), also called Shabbos (, ) by Ashkenazim, is Judaism's day of rest on the seventh day of the week—i.e., Saturday. On this day, religious Jews remember the biblical storie ...

;

*and racial antisemitism, with its extreme form resulting in the Holocaust by the Nazis.

Louis Harap separates "economic antisemitism" and merges "political" and "nationalistic" antisemitism into "ideological antisemitism". Harap also adds a category of "social antisemitism".

* religious (Jew as Christ-killer),

* economic (Jew as banker, usurer, money-obsessed),

* social (Jew as social inferior, "pushy," vulgar, therefore excluded from personal contact),

* racist (Jews as an inferior "race"),

* ideological (Jews regarded as subversive or revolutionary),

* cultural (Jews regarded as undermining the moral and structural fiber of civilization).

Cultural antisemitism

Louis Harap defines cultural antisemitism as "that species of anti-Semitism that charges the Jews with corrupting a given culture and attempting to supplant or succeeding in supplanting the preferred culture with a uniform, crude, "Jewish" culture." Similarly, Eric Kandel characterizes cultural antisemitism as being based on the idea of "Jewishness" as a "religious or cultural tradition that is acquired through learning, through distinctive traditions and education." According to Kandel, this form of antisemitism views Jews as possessing "unattractive psychological and social characteristics that are acquired through acculturation." Niewyk and Nicosia characterize cultural antisemitism as focusing on and condemning "the Jews' aloofness from the societies in which they live." An important feature of cultural antisemitism is that it considers the negative attributes of Judaism to be redeemable by education or by religious conversion.Religious antisemitism

Religious antisemitism

Religious antisemitism is aversion to or discrimination against Jews as a whole, based on religious doctrines of supersession that expect or demand the disappearance of Judaism and the conversion of Jews, and which figure their political ene ...

, also known as anti-Judaism, is antipathy towards Jews because of their perceived religious beliefs. In theory, antisemitism and attacks against individual Jews would stop if Jews stopped practicing Judaism or changed their public faith, especially by conversion to the official or right religion. However, in some cases, discrimination continues after conversion, as in the case of '' Marranos'' (Christianized Jews in Spain and Portugal) in the late 15th century and 16th century, who were suspected of secretly practising Judaism or Jewish customs.

Although the origins of antisemitism are rooted in the Judeo-Christian conflict, other forms of antisemitism have developed in modern times. Frederick Schweitzer asserts that "most scholars ignore the Christian foundation on which the modern antisemitic edifice rests and invoke political antisemitism, cultural antisemitism, racism or racial antisemitism, economic antisemitism, and the like." William Nichols draws a distinction between religious antisemitism and modern antisemitism based on racial or ethnic grounds: "The dividing line was the possibility of effective conversion ..a Jew ceased to be a Jew upon baptism." From the perspective of racial antisemitism, however, "the assimilated Jew was still a Jew, even after baptism. ..From the Enlightenment

Enlightenment or enlighten may refer to:

Age of Enlightenment

* Age of Enlightenment, period in Western intellectual history from the late 17th to late 18th century, centered in France but also encompassing (alphabetically by country or culture): ...

onward, it is no longer possible to draw clear lines of distinction between religious and racial forms of hostility towards Jews ..Once Jews have been emancipated and secular thinking makes its appearance, without leaving behind the old Christian hostility towards Jews, the new term antisemitism becomes almost unavoidable, even before explicitly racist doctrines appear."

Some Christians such as the Catholic priest Ernest Jouin

Monsignor Ernest Jouin (21 December 1844 – 27 June 1932) was a French Catholic priest and essayist, known for his promotion of the Judeo-Masonic conspiracy theory. He also published the first French edition of ''The Protocols of the Elders of Z ...

, who published the first French translation of the ''Protocols'', combined religious and racial antisemitism, as in his statement that "From the triple viewpoint of race, of nationality, and of religion, the Jew has become the enemy of humanity." The virulent antisemitism of Édouard Drumont, one of the most widely read Catholic writers in France during the Dreyfus Affair, likewise combined religious and racial antisemitism. Drumont founded the Antisemitic League of France.

Economic antisemitism

The underlying premise of economic antisemitism is that Jews perform harmful economic activities or that economic activities become harmful when they are performed by Jews. Linking Jews and money underpins the most damaging and lasting antisemitic canards. Antisemites claim that Jews control the world finances, a theory promoted in the fraudulent Protocols of the Elders of Zion, and later repeated by Henry Ford and his Dearborn Independent. In the modern era, such myths continue to be spread in books such as '' The Secret Relationship Between Blacks and Jews'' published by theNation of Islam

The Nation of Islam (NOI) is a religious and political organization founded in the United States by Wallace Fard Muhammad in 1930.

A black nationalist organization, the NOI focuses its attention on the African diaspora, especially on African ...

, and on the internet.

Derek Penslar writes that there are two components to the financial canards:

:a) Jews are savages that "are temperamentally incapable of performing honest labor"

:b) Jews are "leaders of a financial cabal seeking world domination"

Abraham Foxman describes six facets of the financial canards:

#All Jews are wealthy

#Jews are stingy and greedy

#Powerful Jews control the business world

#Jewish religion emphasizes profit and materialism

#It is okay for Jews to cheat non-Jews

#Jews use their power to benefit "their own kind"

Gerald Krefetz

Gerald Krefetz (died 27 January 2006)

''The New York Times.'' January 29, 2006. Retrieved 23 August 2012. was an

''The New York Times.'' January 29, 2006. Retrieved 23 August 2012. was an

ewscontrol the banks, the money supply, the economy, and businesses—of the community, of the country, of the world". Krefetz gives, as illustrations, many slurs and proverbs (in several different languages) which suggest that Jews are stingy, or greedy, or miserly, or aggressive bargainers. During the nineteenth century, Jews were described as "scurrilous, stupid, and tight-fisted", but after the Jewish Emancipation and the rise of Jews to the middle- or upper-class in Europe were portrayed as "clever, devious, and manipulative financiers out to dominate orld finances.

Léon Poliakov asserts that economic antisemitism is not a distinct form of antisemitism, but merely a manifestation of theologic antisemitism (because, without the theological causes of economic antisemitism, there would be no economic antisemitism). In opposition to this view, Derek Penslar contends that in the modern era, economic antisemitism is "distinct and nearly constant" but theological antisemitism is "often subdued".

An academic study by Francesco D'Acunto, Marcel Prokopczuk, and Michael Weber showed that people who live in areas of Germany that contain the most brutal history of antisemitic persecution are more likely to be distrustful of finance in general. Therefore, they tended to invest less money in the stock market and make poor financial decisions. The study concluded, "that the persecution of minorities reduces not only the long-term wealth of the persecuted but of the persecutors as well."

Racial antisemitism is prejudice against Jews as a racial/ethnic group, rather than Judaism as a religion.

Racial antisemitism is the idea that the Jews are a distinct and inferior race compared to their host nations. In the late 19th century and early 20th century, it gained mainstream acceptance as part of the eugenics movement, which categorized non-Europeans as inferior. It more specifically claimed that Northern Europeans, or "Aryans", were superior. Racial antisemites saw the Jews as part of a Semitic race and emphasized their non-European origins and culture. They saw Jews as beyond redemption even if they converted to the majority religion.

Racial antisemitism replaced the hatred of Judaism with the hatred of Jews as a group. In the context of the Industrial Revolution, following the Jewish Emancipation, Jews rapidly urbanized and experienced a period of greater social mobility. With the decreasing role of religion in public life tempering religious antisemitism, a combination of growing nationalism, the rise of eugenics, and resentment at the socio-economic success of the Jews led to the newer, and more virulent, racist antisemitism.

According to William Nichols, religious antisemitism may be distinguished from modern antisemitism based on racial or ethnic grounds. "The dividing line was the possibility of effective conversion... a Jew ceased to be a Jew upon baptism." However, with racial antisemitism, "Now the assimilated Jew was still a Jew, even after baptism... From the

Racial antisemitism is prejudice against Jews as a racial/ethnic group, rather than Judaism as a religion.

Racial antisemitism is the idea that the Jews are a distinct and inferior race compared to their host nations. In the late 19th century and early 20th century, it gained mainstream acceptance as part of the eugenics movement, which categorized non-Europeans as inferior. It more specifically claimed that Northern Europeans, or "Aryans", were superior. Racial antisemites saw the Jews as part of a Semitic race and emphasized their non-European origins and culture. They saw Jews as beyond redemption even if they converted to the majority religion.

Racial antisemitism replaced the hatred of Judaism with the hatred of Jews as a group. In the context of the Industrial Revolution, following the Jewish Emancipation, Jews rapidly urbanized and experienced a period of greater social mobility. With the decreasing role of religion in public life tempering religious antisemitism, a combination of growing nationalism, the rise of eugenics, and resentment at the socio-economic success of the Jews led to the newer, and more virulent, racist antisemitism.

According to William Nichols, religious antisemitism may be distinguished from modern antisemitism based on racial or ethnic grounds. "The dividing line was the possibility of effective conversion... a Jew ceased to be a Jew upon baptism." However, with racial antisemitism, "Now the assimilated Jew was still a Jew, even after baptism... From the

Holocaust Denial, a Definition

, The Holocaust History Project, 2 July 2004. Retrieved 15 August 2016.Introduction: Denial as Anti-Semitism

, "Holocaust Denial: An Online Guide to Exposing and Combating Anti-Semitic Propaganda",

The New antisemitism

, accessed 5 March 2006

, '' The Guardian'', 8 August 2004. * Todd M. Endelma

"Antisemitism in Western Europe Today"

in ''Contemporary Antisemitism: Canada and the World''. University of Toronto Press, 2005, pp. 65–79. * David Matas

''Aftershock: Anti-Zionism and Antisemitism''

, Dundurn Press, 2005, pp. 30–31. *

Many authors see the roots of modern antisemitism in both pagan antiquity and early Christianity. Jerome Chanes identifies six stages in the historical development of antisemitism:

#Pre-Christian anti-Judaism in ancient Greece and Rome which was primarily ethnic in nature

#Christian antisemitism in antiquity and the Middle Ages which was religious in nature and has extended into modern times

#Traditional Muslim antisemitism which was—at least, in its classical form—nuanced in that Jews were a protected class

#Political, social and economic antisemitism of Enlightenment and post-Enlightenment Europe which laid the groundwork for racial antisemitism

#Racial antisemitism that arose in the 19th century and culminated in Nazism in the 20th century

#Contemporary antisemitism which has been labeled by some as the New Antisemitism

Chanes suggests that these six stages could be merged into three categories: "ancient antisemitism, which was primarily ethnic in nature; Christian antisemitism, which was religious; and the racial antisemitism of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries."

Many authors see the roots of modern antisemitism in both pagan antiquity and early Christianity. Jerome Chanes identifies six stages in the historical development of antisemitism:

#Pre-Christian anti-Judaism in ancient Greece and Rome which was primarily ethnic in nature

#Christian antisemitism in antiquity and the Middle Ages which was religious in nature and has extended into modern times

#Traditional Muslim antisemitism which was—at least, in its classical form—nuanced in that Jews were a protected class

#Political, social and economic antisemitism of Enlightenment and post-Enlightenment Europe which laid the groundwork for racial antisemitism

#Racial antisemitism that arose in the 19th century and culminated in Nazism in the 20th century

#Contemporary antisemitism which has been labeled by some as the New Antisemitism

Chanes suggests that these six stages could be merged into three categories: "ancient antisemitism, which was primarily ethnic in nature; Christian antisemitism, which was religious; and the racial antisemitism of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries."

Encyclopædia Britannica Online

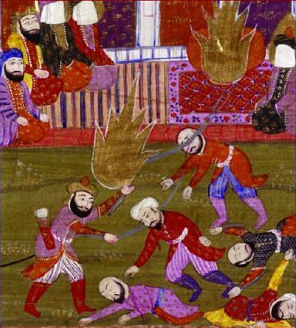

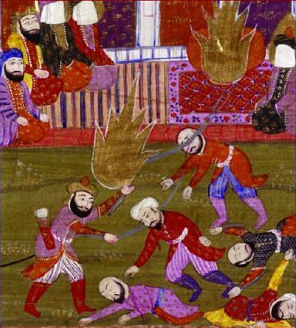

. were far more fundamentalist in outlook compared to their predecessors, and they treated the ''dhimmis'' harshly. Faced with the choice of either death or conversion, many Jews and Christians emigrated. Some, such as the family of Maimonides, fled east to more tolerant Muslim lands, while some others went northward to settle in the growing Christian kingdoms. In medieval Europe, Jews were persecuted with blood libels, expulsions, forced conversions and massacres. These persecutions were often justified on religious grounds and reached a first peak during the Crusades. In 1096, hundreds or thousands of Jews were killed during the First Crusade. This was the first major outbreak of anti-Jewish violence in Christian Europe outside Spain and was cited by Zionists in the 19th century as indicating the need for a state of Israel. In 1147, there were several massacres of Jews during the

In medieval Europe, Jews were persecuted with blood libels, expulsions, forced conversions and massacres. These persecutions were often justified on religious grounds and reached a first peak during the Crusades. In 1096, hundreds or thousands of Jews were killed during the First Crusade. This was the first major outbreak of anti-Jewish violence in Christian Europe outside Spain and was cited by Zionists in the 19th century as indicating the need for a state of Israel. In 1147, there were several massacres of Jews during the

Racial antisemitism

Racial antisemitism is prejudice against Jews as a racial/ethnic group, rather than Judaism as a religion.

Racial antisemitism is the idea that the Jews are a distinct and inferior race compared to their host nations. In the late 19th century and early 20th century, it gained mainstream acceptance as part of the eugenics movement, which categorized non-Europeans as inferior. It more specifically claimed that Northern Europeans, or "Aryans", were superior. Racial antisemites saw the Jews as part of a Semitic race and emphasized their non-European origins and culture. They saw Jews as beyond redemption even if they converted to the majority religion.

Racial antisemitism replaced the hatred of Judaism with the hatred of Jews as a group. In the context of the Industrial Revolution, following the Jewish Emancipation, Jews rapidly urbanized and experienced a period of greater social mobility. With the decreasing role of religion in public life tempering religious antisemitism, a combination of growing nationalism, the rise of eugenics, and resentment at the socio-economic success of the Jews led to the newer, and more virulent, racist antisemitism.

According to William Nichols, religious antisemitism may be distinguished from modern antisemitism based on racial or ethnic grounds. "The dividing line was the possibility of effective conversion... a Jew ceased to be a Jew upon baptism." However, with racial antisemitism, "Now the assimilated Jew was still a Jew, even after baptism... From the

Racial antisemitism is prejudice against Jews as a racial/ethnic group, rather than Judaism as a religion.

Racial antisemitism is the idea that the Jews are a distinct and inferior race compared to their host nations. In the late 19th century and early 20th century, it gained mainstream acceptance as part of the eugenics movement, which categorized non-Europeans as inferior. It more specifically claimed that Northern Europeans, or "Aryans", were superior. Racial antisemites saw the Jews as part of a Semitic race and emphasized their non-European origins and culture. They saw Jews as beyond redemption even if they converted to the majority religion.

Racial antisemitism replaced the hatred of Judaism with the hatred of Jews as a group. In the context of the Industrial Revolution, following the Jewish Emancipation, Jews rapidly urbanized and experienced a period of greater social mobility. With the decreasing role of religion in public life tempering religious antisemitism, a combination of growing nationalism, the rise of eugenics, and resentment at the socio-economic success of the Jews led to the newer, and more virulent, racist antisemitism.

According to William Nichols, religious antisemitism may be distinguished from modern antisemitism based on racial or ethnic grounds. "The dividing line was the possibility of effective conversion... a Jew ceased to be a Jew upon baptism." However, with racial antisemitism, "Now the assimilated Jew was still a Jew, even after baptism... From the Enlightenment

Enlightenment or enlighten may refer to:

Age of Enlightenment

* Age of Enlightenment, period in Western intellectual history from the late 17th to late 18th century, centered in France but also encompassing (alphabetically by country or culture): ...

onward, it is no longer possible to draw clear lines of distinction between religious and racial forms of hostility towards Jews... Once Jews have been emancipated and secular thinking makes its appearance, without leaving behind the old Christian hostility towards Jews, the new term antisemitism becomes almost unavoidable, even before explicitly racist doctrines appear."

In the early 19th century, a number of laws enabling the emancipation of the Jews were enacted in Western European countries. The old laws restricting them to ghettos, as well as the many laws that limited their property rights, rights of worship and occupation, were rescinded. Despite this, traditional discrimination and hostility to Jews on religious grounds persisted and was supplemented by racial antisemitism, encouraged by the work of racial theorists such as Joseph Arthur de Gobineau and particularly his ''Essay on the Inequality of the Human Race'' of 1853–1855. Nationalist agendas based on ethnicity

An ethnic group or an ethnicity is a grouping of people who identify with each other on the basis of shared attributes that distinguish them from other groups. Those attributes can include common sets of traditions, ancestry, language, history, ...

, known as ethnonationalism, usually excluded the Jews from the national community as an alien race. Allied to this were theories of Social Darwinism, which stressed a putative conflict between higher and lower races of human beings. Such theories, usually posited by northern Europeans, advocated the superiority of white Aryan

Aryan or Arya (, Indo-Iranian *''arya'') is a term originally used as an ethnocultural self-designation by Indo-Iranians in ancient times, in contrast to the nearby outsiders known as 'non-Aryan' (*''an-arya''). In Ancient India, the term ' ...

s to Semitic

Semitic most commonly refers to the Semitic languages, a name used since the 1770s to refer to the language family currently present in West Asia, North and East Africa, and Malta.

Semitic may also refer to:

Religions

* Abrahamic religions

** ...

Jews.

Political antisemitism

William Brustein defines political antisemitism as hostility toward Jews based on the belief that Jews seek national and/or world power. Yisrael Gutman characterizes political antisemitism as tending to "lay responsibility on the Jews for defeats and political economic crises" while seeking to "exploit opposition and resistance to Jewish influence as elements in political party platforms."Derek J. Penslar Derek Jonathan Penslar, (born 1958) is an American-Canadian comparative historian with interests in the relationship between modern Israel and diaspora Jewish societies, global nationalist movements, European colonialism, and post-colonial states. ...

wrote, "Political antisemitism identified the Jews as responsible for all the anxiety-provoking social forces that characterized modernity."

According to Viktor Karády, political antisemitism became widespread after the legal emancipation of the Jews and sought to reverse some of the consequences of that emancipation.

Conspiracy theories

Holocaust denial and Jewish conspiracy theories are also considered forms of antisemitism.Mathis, Andrew EHolocaust Denial, a Definition

, The Holocaust History Project, 2 July 2004. Retrieved 15 August 2016.Introduction: Denial as Anti-Semitism

, "Holocaust Denial: An Online Guide to Exposing and Combating Anti-Semitic Propaganda",

Anti-Defamation League

The Anti-Defamation League (ADL), formerly known as the Anti-Defamation League of B'nai B'rith, is an international Jewish non-governmental organization based in the United States specializing in civil rights law. It was founded in late Septe ...

, 2001. Retrieved 12 June 2007. Zoological conspiracy theories

Zoological conspiracy theories involving Israel are occasionally found in the media or on the Internet, typically in Muslim-majority countries, alleging use of animals by Israel to attack civilians or to conduct espionage. These conspiracies are o ...

have been propagated by Arab media and Arabic language websites, alleging a "Zionist plot" behind the use of animals to attack civilians or to conduct espionage.

New antisemitism

Starting in the 1990s, some scholars have advanced the concept of new antisemitism, coming simultaneously from theleft

Left may refer to:

Music

* ''Left'' (Hope of the States album), 2006

* ''Left'' (Monkey House album), 2016

* "Left", a song by Nickelback from the album ''Curb'', 1996

Direction

* Left (direction), the relative direction opposite of right

* L ...

, the right, and radical Islam

Islamic extremism, Islamist extremism, or radical Islam, is used in reference to extremist beliefs and behaviors which are associated with the Islamic religion. These are controversial terms with varying definitions, ranging from academic unde ...

, which tends to focus on opposition to the creation of a Jewish homeland in the State of Israel

Israel (; he, יִשְׂרָאֵל, ; ar, إِسْرَائِيل, ), officially the State of Israel ( he, מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל, label=none, translit=Medīnat Yīsrāʾēl; ), is a country in Western Asia. It is situated ...

,* Phyllis Chesler. ''The New Antisemitism: The Current Crisis and What We Must Do About It'', Jossey-Bass, 2003, pp. 158–159, 181

* Warren KinsellaThe New antisemitism

, accessed 5 March 2006

, '' The Guardian'', 8 August 2004. * Todd M. Endelma

"Antisemitism in Western Europe Today"

in ''Contemporary Antisemitism: Canada and the World''. University of Toronto Press, 2005, pp. 65–79. * David Matas

''Aftershock: Anti-Zionism and Antisemitism''

, Dundurn Press, 2005, pp. 30–31. *

Robert S. Wistrich

Robert Solomon Wistrich (April 7, 1945 – May 19, 2015) was the Erich Neuberger Professor of European and Jewish history at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, and the head of the University's Vidal Sassoon International Center for the Study ...

"From Ambivalence to Betrayal: The Left, the Jews, and Israel (Studies in Antisemitism)", University of Nebraska Press, 2012 and they argue that the language of anti-Zionism

Anti-Zionism is opposition to Zionism. Although anti-Zionism is a heterogeneous phenomenon, all its proponents agree that the creation of the modern State of Israel, and the movement to create a sovereign Jewish state in the region of Palestin ...

and criticism of Israel are used to attack Jews more broadly. In this view, the proponents of the new concept believe that criticisms of Israel and Zionism are often disproportionate in degree and unique in kind, and they attribute this to antisemitism. Jewish scholar Gustavo Perednik

Gustavo Daniel Perednik ( he, גוסטבו דניאל פרדניק; born 1956) is an Argentinian-born Israeli author and educator.

Perednik graduated from the Universities of Buenos Aires and Jerusalem (cum laude), has a PhD in education (Universi ...

posited in 2004 that anti-Zionism in itself represents a form of discrimination against Jews, in that it singles out Jewish national aspirations as an illegitimate and racist endeavor, and "proposes actions that would result in the death of millions of Jews". It is asserted that the new antisemitism deploys traditional antisemitic motifs, including older motifs such as the blood libel.

Critics of the concept view it as trivializing the meaning of antisemitism, and as exploiting antisemitism in order to silence debate and to deflect attention from legitimate criticism of the State of Israel, and, by associating anti-Zionism with antisemitism, misusing it to taint anyone opposed to Israeli actions and policies.

History

Many authors see the roots of modern antisemitism in both pagan antiquity and early Christianity. Jerome Chanes identifies six stages in the historical development of antisemitism:

#Pre-Christian anti-Judaism in ancient Greece and Rome which was primarily ethnic in nature

#Christian antisemitism in antiquity and the Middle Ages which was religious in nature and has extended into modern times

#Traditional Muslim antisemitism which was—at least, in its classical form—nuanced in that Jews were a protected class

#Political, social and economic antisemitism of Enlightenment and post-Enlightenment Europe which laid the groundwork for racial antisemitism

#Racial antisemitism that arose in the 19th century and culminated in Nazism in the 20th century

#Contemporary antisemitism which has been labeled by some as the New Antisemitism

Chanes suggests that these six stages could be merged into three categories: "ancient antisemitism, which was primarily ethnic in nature; Christian antisemitism, which was religious; and the racial antisemitism of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries."

Many authors see the roots of modern antisemitism in both pagan antiquity and early Christianity. Jerome Chanes identifies six stages in the historical development of antisemitism:

#Pre-Christian anti-Judaism in ancient Greece and Rome which was primarily ethnic in nature

#Christian antisemitism in antiquity and the Middle Ages which was religious in nature and has extended into modern times

#Traditional Muslim antisemitism which was—at least, in its classical form—nuanced in that Jews were a protected class

#Political, social and economic antisemitism of Enlightenment and post-Enlightenment Europe which laid the groundwork for racial antisemitism

#Racial antisemitism that arose in the 19th century and culminated in Nazism in the 20th century

#Contemporary antisemitism which has been labeled by some as the New Antisemitism

Chanes suggests that these six stages could be merged into three categories: "ancient antisemitism, which was primarily ethnic in nature; Christian antisemitism, which was religious; and the racial antisemitism of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries."

Ancient world

The first clear examples of anti-Jewish sentiment can be traced to the 3rd century BCE to Alexandria, the home to the largest Jewish diaspora community in the world at the time and where the Septuagint, a Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible, was produced.Manetho

Manetho (; grc-koi, Μανέθων ''Manéthōn'', ''gen''.: Μανέθωνος) is believed to have been an Egyptian priest from Sebennytos ( cop, Ϫⲉⲙⲛⲟⲩϯ, translit=Čemnouti) who lived in the Ptolemaic Kingdom in the early third ...

, an Egyptian priest and historian of that era, wrote scathingly of the Jews. His themes are repeated in the works of Chaeremon, Lysimachus

Lysimachus (; Greek: Λυσίμαχος, ''Lysimachos''; c. 360 BC – 281 BC) was a Thessalian officer and successor of Alexander the Great, who in 306 BC, became King of Thrace, Asia Minor and Macedon.

Early life and career

Lysimachus was b ...

, Poseidonius, Apollonius Molon Apollonius Molon or Molo of Rhodes (or simply Molon; grc, Ἀπολλώνιος ὁ Μόλων), was a Greek rhetorician. He was a native of Alabanda, a pupil of Menecles, and settled at Rhodes, where he opened a school of rhetoric. Prior to that, ...

, and in Apion and Tacitus. Agatharchides of Cnidus ridiculed the practices of the Jews and the "absurdity of their Law", making a mocking reference to how Ptolemy Lagus was able to invade Jerusalem in 320 BCE because its inhabitants were observing the ''Shabbat

Shabbat (, , or ; he, שַׁבָּת, Šabbāṯ, , ) or the Sabbath (), also called Shabbos (, ) by Ashkenazim, is Judaism's day of rest on the seventh day of the week—i.e., Saturday. On this day, religious Jews remember the biblical storie ...

''. One of the earliest anti-Jewish edicts, promulgated by Antiochus IV Epiphanes in about 170–167 BCE, sparked a revolt of the Maccabees

The Maccabees (), also spelled Machabees ( he, מַכַּבִּים, or , ; la, Machabaei or ; grc, Μακκαβαῖοι, ), were a group of Jewish rebel warriors who took control of Judea, which at the time was part of the Seleucid Empire. ...

in Judea.

In view of Manetho's anti-Jewish writings, antisemitism may have originated in Egypt and been spread by "the Greek retelling of Ancient Egyptian prejudices".Schäfer, Peter. ''Judeophobia'', Harvard University Press, 1997, p. 208. Peter Schäfer The ancient Jewish philosopher Philo of Alexandria describes an attack on Jews in Alexandria in 38 CE in which thousands of Jews died.Barclay, John M G, 1999. ''Jews in the Mediterranean Diaspora: From Alexander to Trajan (323 BCE–117 CE)'', University of California. John M. G. Barclay of the University of Durham The violence in Alexandria may have been caused by the Jews being portrayed as misanthropes.Van Der Horst, Pieter Willem, 2003. ''Philo's Flaccus: The First Pogrom'', Philo of Alexandria Commentary Series, Brill. Pieter Willem van der Horst Tcherikover argues that the reason for hatred of Jews in the Hellenistic period was their separateness in the Greek cities, the '' poleis''.Tcherikover, Victor, ''Hellenistic Civilization and the Jews'', New York: Atheneum, 1975 Bohak has argued, however, that early animosity against the Jews cannot be regarded as being anti-Judaic or antisemitic unless it arose from attitudes that were held against the Jews alone, and that many Greeks showed animosity toward any group they regarded as barbarians.Bohak, Gideon. "The Ibis and the Jewish Question: Ancient 'Antisemitism' in Historical Context" in Menachem Mor et al., ''Jews and Gentiles in the Holy Land in the Days of the Second Temple, the Mishna and the Talmud'', Yad Ben-Zvi Press, 2003, pp. 27–43 .

Statements exhibiting prejudice against Jews and their religion can be found in the works of many pagan

Paganism (from classical Latin ''pāgānus'' "rural", "rustic", later "civilian") is a term first used in the fourth century by early Christians for people in the Roman Empire who practiced polytheism, or ethnic religions other than Judaism. ...

Greek and Roman writers. Edward Flannery writes that it was the Jews' refusal to accept Greek religious and social standards that marked them out. Hecataetus of Abdera, a Greek historian of the early third century BCE, wrote that Moses "in remembrance of the exile of his people, instituted for them a misanthropic and inhospitable way of life." Manetho

Manetho (; grc-koi, Μανέθων ''Manéthōn'', ''gen''.: Μανέθωνος) is believed to have been an Egyptian priest from Sebennytos ( cop, Ϫⲉⲙⲛⲟⲩϯ, translit=Čemnouti) who lived in the Ptolemaic Kingdom in the early third ...

, an Egyptian historian, wrote that the Jews were expelled Egyptian lepers who had been taught by Moses

Moses hbo, מֹשֶׁה, Mōše; also known as Moshe or Moshe Rabbeinu (Mishnaic Hebrew: מֹשֶׁה רַבֵּינוּ, ); syr, ܡܘܫܐ, Mūše; ar, موسى, Mūsā; grc, Mωϋσῆς, Mōÿsēs () is considered the most important pro ...

"not to adore the gods." Edward Flannery describes antisemitism in ancient times as essentially "cultural, taking the shape of a national xenophobia played out in political settings."

There are examples of Hellenistic

In Classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Mediterranean history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the emergence of the Roman Empire, as signified by the Battle of Actium in ...

rulers desecrating the Temple and banning Jewish religious practices, such as circumcision, Shabbat observance, the study of Jewish religious books, etc. Examples may also be found in anti-Jewish riots in Alexandria in the 3rd century BCE.

The Jewish diaspora on the Nile island Elephantine

Elephantine ( ; ; arz, جزيرة الفنتين; el, Ἐλεφαντίνη ''Elephantíne''; , ) is an island on the Nile, forming part of the city of Aswan in Upper Egypt. The archaeological sites on the island were inscribed on the UNESCO ...

, which was founded by mercenaries, experienced the destruction of its temple in 410 BCE.

Relationships between the Jewish people and the occupying Roman Empire were at times antagonistic and resulted in several rebellions. According to Suetonius

Gaius Suetonius Tranquillus (), commonly referred to as Suetonius ( ; c. AD 69 – after AD 122), was a Roman historian who wrote during the early Imperial era of the Roman Empire.

His most important surviving work is a set of biographies ...

, the emperor Tiberius expelled from Rome Jews who had gone to live there. The 18th-century English historian Edward Gibbon identified a more tolerant period in Roman-Jewish relations beginning in about 160 CE. However, when Christianity became the state religion of the Roman Empire, the state's attitude towards the Jews gradually worsened.

James Carroll asserted: "Jews accounted for 10% of the total population of the Roman Empire. By that ratio, if other factors such as pogroms and conversions had not intervened, there would be 200 million Jews in the world today, instead of something like 13 million."

Persecutions during the Middle Ages

In the late 6th century CE, the newly Catholicised Visigothic kingdom in Hispania issued a series of anti-Jewish edicts which forbade Jews from marrying Christians, practicing circumcision, and observing Jewish holy days. Continuing throughout the 7th century, both Visigothic kings and the Church were active in creating social aggression and towards Jews with "civic and ecclesiastic punishments", ranging between forced conversion, slavery, exile and death. From the 9th century, themedieval Islamic world

The Islamic Golden Age was a period of cultural, economic, and scientific flourishing in the history of Islam, traditionally dated from the 8th century to the 14th century. This period is traditionally understood to have begun during the reign ...

classified Jews and Christians as '' dhimmis'', and allowed Jews to practice their religion more freely than they could do in medieval Christian Europe. Under Islamic rule, there was a Golden age of Jewish culture in Spain that lasted until at least the 11th century. It ended when several Muslim pogroms against Jews took place on the Iberian Peninsula, including those that occurred in Córdoba in 1011 and in Granada in 1066. Several decrees ordering the destruction of synagogue

A synagogue, ', 'house of assembly', or ', "house of prayer"; Yiddish: ''shul'', Ladino: or ' (from synagogue); or ', "community". sometimes referred to as shul, and interchangeably used with the word temple, is a Jewish house of worshi ...

s were also enacted in Egypt, Syria

Syria ( ar, سُورِيَا or سُورِيَة, translit=Sūriyā), officially the Syrian Arab Republic ( ar, الجمهورية العربية السورية, al-Jumhūrīyah al-ʻArabīyah as-Sūrīyah), is a Western Asian country loc ...

, Iraq and Yemen from the 11th century. In addition, Jews were forced to convert to Islam

Islam (; ar, ۘالِإسلَام, , ) is an Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic Monotheism#Islam, monotheistic religion centred primarily around the Quran, a religious text considered by Muslims to be the direct word of God in Islam, God (or ...

or face death in some parts of Yemen, Morocco and Baghdad several times between the 12th and 18th centuries. The Almohads, who had taken control of the Almoravids

The Almoravid dynasty ( ar, المرابطون, translit=Al-Murābiṭūn, lit=those from the ribats) was an imperial Berber Muslim dynasty centered in the territory of present-day Morocco. It established an empire in the 11th century that ...

' Maghribi and Andalusian territories by 1147,Islamic world. (2007). In Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2 September 2007, froEncyclopædia Britannica Online

. were far more fundamentalist in outlook compared to their predecessors, and they treated the ''dhimmis'' harshly. Faced with the choice of either death or conversion, many Jews and Christians emigrated. Some, such as the family of Maimonides, fled east to more tolerant Muslim lands, while some others went northward to settle in the growing Christian kingdoms.

Second Crusade

The Second Crusade (1145–1149) was the second major crusade launched from Europe. The Second Crusade was started in response to the fall of the County of Edessa in 1144 to the forces of Zengi. The county had been founded during the First Crusa ...

. The Shepherds' Crusades of 1251 and 1320

Year 1320 ( MCCCXX) was a leap year starting on Tuesday (link will display the full calendar) of the Julian calendar.

Events

January–December

* January 20 – Duke Wladyslaw Lokietek becomes king of Poland.

* April 6 – Th ...

both involved attacks, as did Rintfleisch massacres in 1298. Expulsions followed, such as in 1290, the banishment of Jews from England; in 1394, the expulsion of 100,000 Jews in France; and in 1421, the expulsion of thousands from Austria. Many of the expelled Jews fled to Poland. In medieval and Renaissance Europe, a major contributor to the deepening of antisemitic sentiment and legal action among the Christian populations was the popular preaching of the zealous reform religious orders, the Franciscans (especially Bernardino of Feltre) and Dominicans (especially Vincent Ferrer), who combed Europe and promoted antisemitism through their often fiery, emotional appeals.

As the Black Death

The Black Death (also known as the Pestilence, the Great Mortality or the Plague) was a bubonic plague pandemic occurring in Western Eurasia and North Africa from 1346 to 1353. It is the most fatal pandemic recorded in human history, causi ...

epidemics devastated Europe in the mid-14th century, causing the death of a large part of the population, Jews were used as scapegoats

Scapegoating is the practice of singling out a person or group for unmerited blame and consequent negative treatment. Scapegoating may be conducted by individuals against individuals (e.g. "he did it, not me!"), individuals against groups (e.g., ...

. Rumors spread that they caused the disease by deliberately poisoning wells. Hundreds of Jewish communities were destroyed in numerous persecutions. Although Pope Clement VI tried to protect them by issuing two papal bulls in 1348, the first on 6 July and an additional one several months later, 900 Jews were burned alive in Strasbourg, where the plague had not yet affected the city.See Stéphane Barry and Norbert Gualde, ''La plus grande épidémie de l'histoire'' ("The greatest epidemics in history"), in '' L'Histoire'' magazine, n°310, June 2006, p. 47

Reformation

Martin Luther, anecclesiastical

{{Short pages monitor

In Germany, Nazism led Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party, who Machtergreifung, came to power on 30 January 1933 shortly afterwards instituted repressive legislation which denied the Jews basic civil rights.

In September 1935, the Nuremberg Laws prohibited sexual relations and marriages between "Aryans" and Jews as ''Rassenschande'' ("race disgrace") and stripped all German Jews, even quarter- and half-Jews, of their citizenship, (their official title became "subjects of the state"). It instituted a pogrom on the night of 9–10 November 1938, dubbed '' Kristallnacht'', in which Jews were killed, their property destroyed and their synagogues torched. Antisemitic laws, agitation and propaganda were extended to

"Europe's Jews Tied to a Declining Political Class."

''Algemeiner''. 26 January 2015.

Robert L. Bernstein, Robert Bernstein, founder of Human Rights Watch, says that antisemitism is "deeply ingrained and institutionalized" in "Arab nations in modern times."

In a 2011 survey by the Pew Research Center, all of the Muslim-majority Middle Eastern countries polled held significantly negative opinions of Jews. In the questionnaire, only 2% of Egyptians, 3% of Lebanon, Lebanese Muslims, and 2% of Jordanians reported having a positive view of Jews. Muslim-majority countries outside the Middle East similarly held markedly negative views of Jews, with 4% of Turkey, Turks and 9% of Indonesians viewing Jews favorably.

According to a 2011 exhibition at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, United States, some of the dialogue from Middle East media and commentators about Jews bear a striking resemblance to Nazi propaganda. According to Josef Joffe of ''Newsweek'', "anti-Semitism—the real stuff, not just bad-mouthing particular Israeli policies—is as much part of Arab life today as the hijab or the hookah. Whereas this darkest of creeds is no longer tolerated in polite society in the West, in the Arab world, Jew hatred remains culturally endemic."

Muslim clerics in the Middle East have frequently referred to Jews as descendants of apes and pigs, which are conventional epithets for Jews and Christians.

According to professor Robert Wistrich, director of the Vidal Sassoon International Center for the Study of Antisemitism (SICSA), the calls for the destruction of Israel by Iran or by Hamas, Hezbollah, Islamic Jihad Movement in Palestine, Islamic Jihad, or the Muslim Brotherhood, represent a contemporary mode of genocidal antisemitism.

Robert L. Bernstein, Robert Bernstein, founder of Human Rights Watch, says that antisemitism is "deeply ingrained and institutionalized" in "Arab nations in modern times."

In a 2011 survey by the Pew Research Center, all of the Muslim-majority Middle Eastern countries polled held significantly negative opinions of Jews. In the questionnaire, only 2% of Egyptians, 3% of Lebanon, Lebanese Muslims, and 2% of Jordanians reported having a positive view of Jews. Muslim-majority countries outside the Middle East similarly held markedly negative views of Jews, with 4% of Turkey, Turks and 9% of Indonesians viewing Jews favorably.

According to a 2011 exhibition at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, United States, some of the dialogue from Middle East media and commentators about Jews bear a striking resemblance to Nazi propaganda. According to Josef Joffe of ''Newsweek'', "anti-Semitism—the real stuff, not just bad-mouthing particular Israeli policies—is as much part of Arab life today as the hijab or the hookah. Whereas this darkest of creeds is no longer tolerated in polite society in the West, in the Arab world, Jew hatred remains culturally endemic."

Muslim clerics in the Middle East have frequently referred to Jews as descendants of apes and pigs, which are conventional epithets for Jews and Christians.

According to professor Robert Wistrich, director of the Vidal Sassoon International Center for the Study of Antisemitism (SICSA), the calls for the destruction of Israel by Iran or by Hamas, Hezbollah, Islamic Jihad Movement in Palestine, Islamic Jihad, or the Muslim Brotherhood, represent a contemporary mode of genocidal antisemitism.

in: Factors contributing to this situation included that Jews were restricted from other professions, while the Christian Church declared for their followers that money lending constituted immoral "usury".

SSRN

* Arno Tausch, Tausch, Arno (2015). Islamism and Antisemitism. Preliminary Evidence on Their Relationship from Cross-National Opinion Data (14 August 2015). Available a

SSRN

o

Islamism and Antisemitism. Preliminary Evidence on Their Relationship from Cross-National Opinion Data

* Arno Tausch, Tausch, Arno (2014). The New Global Antisemitism: Implications from the Recent ADL-100 Data (14 January 2015). Middle East Review of International Affairs, Vol. 18, No. 3 (Fall 2014). Available a

SSRN

o

The New Global Antisemitism: Implications from the Recent ADL-100 Data

*

Anti-semitism

entry by Gotthard Deutsch in the

online

* Carr, Steven Alan. ''Hollywood and anti-Semitism: A cultural history up to World War II'', Cambridge University Press 2001. * Cohn, Norman. ''Warrant for Genocide'', Eyre & Spottiswoode 1967; Serif, 1996. * Fischer, Klaus P. ''The History of an Obsession: German Judeophobia and the Holocaust'', The Continuum Publishing Company, 1998. * Freudmann, Lillian C. ''Antisemitism in the New Testament'', University Press of America, 1994. * Jane Gerber, Gerber, Jane S. (1986). "Anti-Semitism and the Muslim World". In ''History and Hate: The Dimensions of Anti-Semitism'', ed. David Berger. Jewish Publications Society. * Goldberg, Sol; Ury, Scott; Weiser, Kalman (eds.). ''Key Concepts in the Study of Antisemitism'' (Palgrave Macmillan, 2021

online review

* Hanebrink, Paul. ''A Specter Haunting Europe: The Myth of Judeo-Bolshevism'', Harvard University Press, 2018. . * Raul Hilberg, Hilberg, Raul. ''The Destruction of the European Jews''. Holmes & Meier, 1985. 3 volumes. * Isser, Natalie. ''Antisemitism during the French Second Empire'' (1991) * *McKain, Mark. ''Anti-Semitism: At Issue'', Greenhaven Press, 2005. * Marcus, Kenneth L. The Definition of Anti-Semitism, 2015, Oxford University Press * Michael, Robert and Philip Rosen

Dictionary of Antisemitism

, The Scarecrow Press, Inc., 2007 * Michael, Robert. ''Holy Hatred: Christianity, Antisemitism, and the Holocaust'' * David Nirenberg, Nirenberg, David. ''Anti-Judaism: The Western Tradition'' (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2013) 610 pp. * * Roth, Philip. The Plot Against America, 2004 * Selzer, Michael (ed.). ''"Kike!" : A Documentary History of Anti-Semitism in America'', New York 1972. * Small, Charles Asher ed. ''The Yale Papers: Antisemitism In Comparative Perspective'' (Institute For the Study of Global Antisemitism and Policy, 2015)

online

, scholarly studies. * Stav, Arieh (1999). ''Peace: The Arabian Caricature – A Study of Anti-semitic Imagery''. Gefen Publishing House. . * Steinweis, Alan E. ''Studying the Jew: Scholarly Antisemitism in Nazi Germany''. Harvard University Press, 2006. . * Norman Stillman, Stillman, Norman. ''The Jews of Arab Lands: A History and Source Book''. (Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society of America. 1979). * Stillman, N.A. (2006). "Yahud". ''Encyclopaedia of Islam''. Eds.: P.J. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C.E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel and W.P. Heinrichs. Brill. Brill Online * * * , United States Department of State, 2008. Retrieved 25 November 2010. Se

HTML version

. * Vital, David. ''People Apart: The Jews in Europe, 1789-1939'' (1999); 930pp highly detailed ; Bibliographies, calendars, etc. * ''Jewish Journal of Greater Los Angeles''

"Experts explore effects of Ahmadinejad anti-Semitism"

9 March 2007 *Bernard Lazare, Lazare, Bernard

''Antisemitism: Its History and Causes''

*Anti-Defamation League]

Arab Antisemitism

Why the Jews? A perspective on causes of anti-Semitism

Coordination Forum for Countering Antisemitism

(with up to date calendar of antisemitism today)

Annotated bibliography of anti-Semitism

hosted by the Hebrew University of Jerusalem's Center for the Study of Antisemitism (SICSA)

Council of Europe, ECRI Country-by-Country Reports

* Porat, Dina

''Haaretz'', 27 January 2007. Retrieved 24 November 2010. *A. B. Yehoshua, Yehoshua, A.B.

An Attempt to Identify the Root Cause of Antisemitism

Azure

, Spring 2008.

Antisemitism in modern UkraineAntisemitism and Special Relativity

German-occupied Europe

German-occupied Europe refers to the sovereign countries of Europe which were wholly or partly occupied and civil-occupied (including puppet governments) by the military forces and the government of Nazi Germany at various times between 1939 an ...

in the wake of conquest, often building on local antisemitic traditions.