Andrew Fisher on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

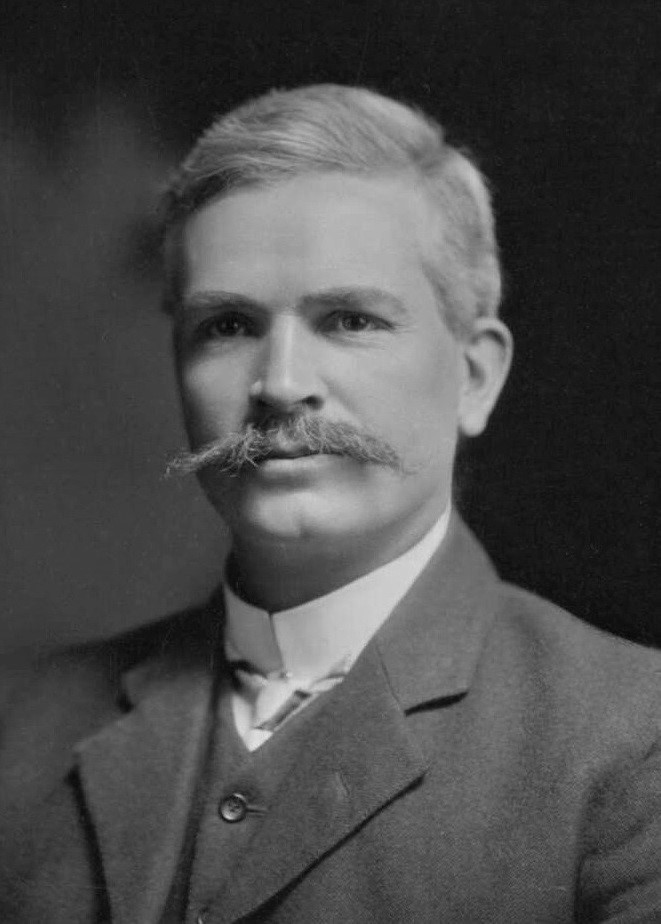

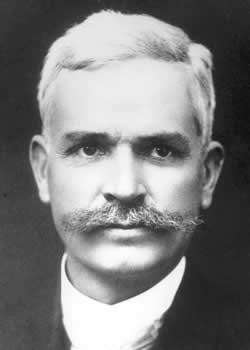

Andrew Fisher (29 August 186222 October 1928) was an Australian politician who served three terms as

Fisher and his younger brother James arrived in

Fisher and his younger brother James arrived in

Fisher formed his only

Fisher formed his only

Fisher wanted additional Commonwealth power in certain areas, such as the

Fisher wanted additional Commonwealth power in certain areas, such as the

Fisher and his party were immediately underway in organising urgent defence measures for planning and implementing Australian war effort. Fisher visited New Zealand during this time which saw

Fisher and his party were immediately underway in organising urgent defence measures for planning and implementing Australian war effort. Fisher visited New Zealand during this time which saw  Fisher passed this report on to Hughes and to Defence Minister

Fisher passed this report on to Hughes and to Defence Minister

Despite the length of Fisher's service as prime minister, for many years he and his government were given relatively little scholarly attention. His decision to retire to England placed him out of the public eye, while his mental deterioration and early death deprived him of the opportunity to dictate his own legacy. Writers interested in the post-Federation era did not generally view him as an attractive biographical subject, which has been attributed to the relative orthodoxy of his political views and a reputation for propriety to the point of dullness. Fisher's 1981 entry in the ''

Despite the length of Fisher's service as prime minister, for many years he and his government were given relatively little scholarly attention. His decision to retire to England placed him out of the public eye, while his mental deterioration and early death deprived him of the opportunity to dictate his own legacy. Writers interested in the post-Federation era did not generally view him as an attractive biographical subject, which has been attributed to the relative orthodoxy of his political views and a reputation for propriety to the point of dullness. Fisher's 1981 entry in the ''

Andrew Fisher: a reforming treasurer – treasury.gov.auPrime Ministers of Australia: Andrew Fisher

Andrew Fisher – Scaramouche

{{DEFAULTSORT:Fisher, Andrew Prime Ministers of Australia Treasurers of Australia Members of the Cabinet of Australia Australian Leaders of the Opposition Australian Labor Party members of the Parliament of Australia Australian federationists Australian miners Australian trade unionists Members of the Australian House of Representatives for Wide Bay Members of the Australian House of Representatives People from East Ayrshire People from Gympie Scottish emigrants to colonial Australia Australian socialists 1862 births 1928 deaths Members of the Queensland Legislative Assembly High Commissioners of Australia to the United Kingdom Australian Labor Party members of the Parliament of Queensland Leaders of the Australian Labor Party 20th-century Australian politicians Australian members of the Privy Council of the United Kingdom Australian Presbyterians Politicians from Queensland

prime minister of Australia

The prime minister of Australia is the head of government of the Commonwealth of Australia. The prime minister heads the executive branch of the Australian Government, federal government of Australia and is also accountable to Parliament of A ...

– from 1908 to 1909, from 1910 to 1913, and from 1914 to 1915. He was the leader of the Australian Labor Party

The Australian Labor Party (ALP), also simply known as Labor, is the major centre-left political party in Australia, one of two major parties in Australian politics, along with the centre-right Liberal Party of Australia. The party forms the f ...

(ALP) from 1907 to 1915.

Fisher was born in Crosshouse

Crosshouse is a village in East Ayrshire about west of Kilmarnock. It grew around the cross-roads of the main Kilmarnock to Irvine road, once classified as the A71 but now reduced in status to the B7081, with a secondary road (the B751) running ...

, Ayrshire

Ayrshire ( gd, Siorrachd Inbhir Àir, ) is a historic county and registration county in south-west Scotland, located on the shores of the Firth of Clyde. Its principal towns include Ayr, Kilmarnock and Irvine and it borders the counties of Re ...

, Scotland. He left school at a young age to work in the nearby coal mines, becoming secretary of the local branch of the Ayrshire Miners' Union The Ayrshire Miners' Union was a coal mining trade union based in Scotland.

History

The first Ayrshire Miners' Union was founded in 1880, with Keir Hardie as its organiser. The union supported a strike for higher wages over the winter of 1881/82, ...

at the age of 17. Fisher immigrated to Australia in 1885, where he continued his involvement with trade unionism. He settled in Gympie, Queensland

Gympie ( ) is a city and a locality in the Gympie Region, Queensland, Australia. In the Wide Bay-Burnett District, Gympie is about north of the state capital, Brisbane. The city lies on the Mary River, which floods Gympie occasionally. The l ...

, and in 1893 was elected to the Queensland Legislative Assembly

The Legislative Assembly of Queensland is the sole chamber of the unicameral Parliament of Queensland established under the Constitution of Queensland. Elections are held every four years and are done by full preferential voting. The Assembly ...

as a representative of the Labor Party. Fisher lost his seat in 1896, but returned in 1899 and later that year briefly served as a minister in the government of Anderson Dawson

Andrew Dawson (16 July 1863 – 20 July 1910), usually known as Anderson Dawson, was an Australian politician, the Premier of Queensland for one week (1–7 December) in 1899. This short-lived premiership was the first Australian Labor Party go ...

.

In 1901, Fisher was elected to the new federal parliament

The Parliament of Australia (officially the Federal Parliament, also called the Commonwealth Parliament) is the legislative branch of the government of Australia. It consists of three elements: the monarch (represented by the governor-gen ...

representing the Division of Wide Bay

The Division of Wide Bay is an Australian electoral division in the state of Queensland.

Geography

Since 1984, federal electoral division boundaries in Australia have been determined at redistributions by a redistribution committee appointed ...

. He served as the Minister for Trade and Customs for a few months in 1904, in the short-lived government of Chris Watson. Fisher was elected deputy leader of the ALP in 1905 and replaced Watson as leader in 1907. He initially provided support to the minority government

A minority government, minority cabinet, minority administration, or a minority parliament is a government and Cabinet (government), cabinet formed in a parliamentary system when a political party or Coalition government, coalition of parties do ...

of Protectionist

Protectionism, sometimes referred to as trade protectionism, is the economic policy of restricting imports from other countries through methods such as tariffs on imported goods, import quotas, and a variety of other government regulations. ...

leader Alfred Deakin

Alfred Deakin (3 August 1856 – 7 October 1919) was an Australian politician who served as the second Prime Minister of Australia. He was a leader of the movement for Federation, which occurred in 1901. During his three terms as prime ministe ...

, but in November 1908 the ALP withdrew its support and Deakin resigned as prime minister. Fisher subsequently formed a minority government of his own. It lasted only a few months, as in June 1909 Deakin returned as prime minister at the head of a new anti-socialist Liberal Party

The Liberal Party is any of many political parties around the world. The meaning of ''liberal'' varies around the world, ranging from liberal conservatism on the right to social liberalism on the left.

__TOC__ Active liberal parties

This is a li ...

.

Fisher returned as prime minister after the 1910 Australian federal election, which saw Labor attain majority government

A majority government is a government by one or more governing parties that hold an absolute majority of seats in a legislature. This is as opposed to a minority government, where the largest party in a legislature only has a plurality of seats. ...

for the first time in its history. His second government passed wide-ranging reforms – old-age and disability pensions, enshrined new workers' rights

Labor rights or workers' rights are both legal rights and human rights relating to labor relations between workers and employers. These rights are codified in national and international labor and employment law. In general, these rights influen ...

in legislation, established the Commonwealth Bank

The Commonwealth Bank of Australia (CBA), or CommBank, is an Australian multinational bank with businesses across New Zealand, Asia, the United States and the United Kingdom. It provides a variety of financial services including retail, busines ...

, oversaw the continued expansion of the Royal Australian Navy

The Royal Australian Navy (RAN) is the principal naval force of the Australian Defence Force (ADF). The professional head of the RAN is Chief of Navy (CN) Vice Admiral Mark Hammond AM, RAN. CN is also jointly responsible to the Minister of ...

, began construction on the Trans-Australian Railway

The Trans-Australian Railway, opened in 1917, runs from Port Augusta in South Australia to Kalgoorlie in Western Australia, crossing the Nullarbor Plain in the process. As the only rail freight corridor between Western Australia and the easter ...

, and formally established what is now the Australian Capital Territory

The Australian Capital Territory (commonly abbreviated as ACT), known as the Federal Capital Territory (FCT) until 1938, is a landlocked federal territory of Australia containing the national capital Canberra and some surrounding townships. ...

. However, at the 1913 election the ALP narrowly lost its House of Representatives majority to the Liberal Party, with Fisher being replaced as prime minister by Joseph Cook.

After just over a year in office, Cook was forced to call a new election, the first double dissolution

A double dissolution is a procedure permitted under the Australian Constitution to resolve deadlocks in the bicameral Parliament of Australia between the House of Representatives (lower house) and the Senate (upper house). A double dissolution ...

. Labor won back its majority in the House, and Fisher returned for a third term as prime minister. During the election campaign he famously declared that Australia would defend Britain "to the last man and the last shilling". However, he struggled with the demands of Australia's participation in World War I and in October 1915 resigned in favour of his deputy Billy Hughes

William Morris Hughes (25 September 1862 – 28 October 1952) was an Australian politician who served as the seventh prime minister of Australia, in office from 1915 to 1923. He is best known for leading the country during World War I, but ...

. Fisher subsequently accepted an appointment as the High Commissioner of Australia to the United Kingdom, holding the position from 1916 to 1920. After a brief return to Australia, he retired to London, dying there at the age of 66. His cumulative total of just under five years as prime minister is the second-longest by an ALP leader, surpassed only by Bob Hawke

Robert James Lee Hawke (9 December 1929 – 16 May 2019) was an Australian politician and union organiser who served as the 23rd prime minister of Australia from 1983 to 1991, holding office as the leader of the Australian Labor Party (A ...

.

Early life

Birth and family background

Fisher was born on 29 August 1862 inCrosshouse

Crosshouse is a village in East Ayrshire about west of Kilmarnock. It grew around the cross-roads of the main Kilmarnock to Irvine road, once classified as the A71 but now reduced in status to the B7081, with a secondary road (the B751) running ...

, a mining village west of Kilmarnock

Kilmarnock (, sco, Kilmaurnock; gd, Cill Mheàrnaig (IPA: ʰʲɪʎˈveaːɾnəkʲ, "Marnock's church") is a large town and former burgh in East Ayrshire, Scotland and is the administrative centre of East Ayrshire, East Ayrshire Council. ...

, Ayrshire

Ayrshire ( gd, Siorrachd Inbhir Àir, ) is a historic county and registration county in south-west Scotland, located on the shores of the Firth of Clyde. Its principal towns include Ayr, Kilmarnock and Irvine and it borders the counties of Re ...

, Scotland. He was the second of eight children born to Jane (née Garven or Garvin) and Robert Fisher; he had one older brother, four younger brothers, and two younger sisters. His younger sister died at the age of 10 in 1879, the only one of the siblings not to live to adulthood. Fisher's mother was the daughter of a blacksmith and worked as a domestic servant. On his father's side, he was descended from a long line of Ayrshire coalminers. According to family tradition, his paternal grandfather was persecuted for his involvement in the fledgling union movement, and on one occasion was left homeless with five young children.Day (2008), p. 5. Although he was probably only partially literate, Fisher's father was prominent in the local community and involved with various community organisations. He was the leader of a temperance society

The temperance movement is a social movement promoting temperance or complete abstinence from consumption of alcoholic beverages. Participants in the movement typically criticize alcohol intoxication or promote teetotalism, and its leaders empha ...

, and in 1863 was one of ten miners who co-founded a cooperative society

A cooperative (also known as co-operative, co-op, or coop) is "an autonomous association of persons united voluntarily to meet their common economic, social and cultural needs and aspirations through a jointly owned and democratically-control ...

. He and his family were active members of the Free Church of Scotland.

Childhood

Fisher spent most of his childhood living in a miners' row, which had an earthen floor and no running water.Bastian (2009), p. 6. He was kicked in the head by a cow as a small child, leaving him mostly deaf in one ear. The injury may have contributed to a childhood speech impediment and his reserved nature as an adult.Bastian (2009), p. 5. As a boy, Fisher and his brothers fished in Carmel Water, a tributary of theRiver Irvine

The River Irvine ( gd, Irbhinn) is a river that flows through southwest Scotland. Its watershed is on the Lanarkshire border of Ayrshire at an altitude of above sea-level, near Loudoun Hill, Drumclog Moss, Drumclog, and SW by W of Strathaven. I ...

, and enjoyed long walks across the countryside. He was athletic, helping form a local football team, and stood as an adult, above the average at the time. In later life, Fisher recalled attending four schools as a boy. The exact details are uncertain, but he is known to have finished his schooling in Crosshouse and to have attended a school in nearby Dreghorn

Dreghorn is a village in North Ayrshire, Scotland, east of Irvine town centre, on the old main road from Irvine to Kilmarnock. It is sited on a ridge between two rivers. As archaeological excavations near the village centre have found a signifi ...

for a period.Day (2008), pp. 8–9. The standard of public education in Scotland was relatively high at the time, and his schoolmaster in Crosshouse had received formal training in Edinburgh; the main focus of the curriculum was on the three Rs

The three Rs (as in the letter ''R'') are three basic skills taught in schools: reading, writing and arithmetic (usually said as "reading, 'riting, and 'rithmetic"). The phrase appears to have been coined at the beginning of the 19th century.

...

. He later supplemented his limited formal education by attending night school in Kilmarnock and reading at the town library.

The exact age at which Fisher left school is uncertain, but he could have been as young as nine or as old as thirteen. He is believed to have begun his working life as a coal trapper, opening and closing the trapdoors that allowed for ventilation and the movement of coal. He was later placed in charge of the pit ponies

A pit pony, otherwise known as a mining horse, was a horse, pony or mule commonly used underground in mines from the mid-18th until the mid-20th century. The term "pony" was sometimes broadly applied to any equine working underground.English ...

, and finally took his place performing "pick-and-shovel work" at the coalface. When he was 16, he was promoted to air-pump operator, which required additional training and was seen as a relatively prestigious position. Fisher's father had black lung disease

Coal workers' pneumoconiosis (CWP), also known as black lung disease or black lung, is an occupational type of pneumoconiosis caused by long-term exposure to coal dust. It is common in coal miners and others who work with coal. It is similar to ...

, and gave up mining around the same time as his oldest sons began working. He subsequently became the manager of the foodstore at the local cooperative, and the family moved out of miners' row. They later lived in Kilmaurs

Kilmaurs () is a village in East Ayrshire, Scotland which lies just outside of the largest settlement in East Ayrshire, Kilmarnock. It lies on the Carmel Water, southwest of Glasgow. Population recorded for the village in the 2001 Census recorde ...

for a period, but eventually returned to Crosshouse and leased a small farm. Fisher's father then worked as a gardener and apiarist, supplementing his income with contract work repairing the machinery at local mines. He died of lung disease in 1887, aged 53.

Early political activities

In 1879, aged 17, Fisher was elected secretary of the Crosshouse branch of theAyrshire Miners' Union The Ayrshire Miners' Union was a coal mining trade union based in Scotland.

History

The first Ayrshire Miners' Union was founded in 1880, with Keir Hardie as its organiser. The union supported a strike for higher wages over the winter of 1881/82, ...

. He soon came into contact with Keir Hardie

James Keir Hardie (15 August 185626 September 1915) was a Scottish trade unionist and politician. He was a founder of the Labour Party, and served as its first parliamentary leader from 1906 to 1908.

Hardie was born in Newhouse, Lanarkshire. ...

, a leading figure in the union and a future leader of the British Labour Party. The pair met frequently to discuss politics and would renew their acquaintance later in life. Fisher and Hardie were leaders of the 1881 Ayrshire miners' strike, which was widely seen as a failure. The ten-week strike resulted in only a small pay rise rather than the 10 percent that had been asked for; many workers depleted their savings and some cooperatives came close to bankruptcy. Fisher had originally been opposed to the strike, and unsuccessfully attempted to negotiate a compromise with mine-owners. He lost his job, but soon found work at a different mine. Like many miners, Fisher was a supporter of Gladstone's Liberal Party

The Liberal Party is any of many political parties around the world. The meaning of ''liberal'' varies around the world, ranging from liberal conservatism on the right to social liberalism on the left.

__TOC__ Active liberal parties

This is a li ...

, in particular the " Liberal-Labour" candidates who had the support of the unions. In 1884, he chaired a public meeting in Crosshouse in support of the Third Reform Bill. He subsequently wrote a letter to Gladstone and received a reply thanking him for his support. The following year, Fisher was involved in another miners' strike. He was not only sacked but also blacklisted. He was left with little future in Scotland and decided to emigrate; his older brother John had already left for England a few years earlier, becoming a police constable in Liverpool

Liverpool is a city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. With a population of in 2019, it is the 10th largest English district by population and its metropolitan area is the fifth largest in the United Kingdom, with a popul ...

.

Move to Australia

Fisher and his younger brother James arrived in

Fisher and his younger brother James arrived in Brisbane

Brisbane ( ) is the capital and most populous city of the states and territories of Australia, Australian state of Queensland, and the list of cities in Australia by population, third-most populous city in Australia and Oceania, with a populati ...

, Queensland

)

, nickname = Sunshine State

, image_map = Queensland in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of Queensland in Australia

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Australia

, established_title = Before federation

, established_ ...

, on 17 August 1885, after a two-month steamship journey from London. He first saw Australia during a stopover at Thursday Island

Thursday Island, colloquially known as TI, or in the Kawrareg dialect, Waiben or Waibene, is an island of the Torres Strait Islands, an archipelago of at least 274 small islands in the Torres Strait. TI is located approximately north of Cape ...

, where whites were a minority and there was a large Japanese population. His biographer David Day has speculated that this initial first impression may have contributed to his later opposition to non-white immigration. Fisher's path to Australia was virtually identical to that of Billy Hughes

William Morris Hughes (25 September 1862 – 28 October 1952) was an Australian politician who served as the seventh prime minister of Australia, in office from 1915 to 1923. He is best known for leading the country during World War I, but ...

, who had arrived less than a year earlier in December 1884 – both men took assisted passage, arrived at the age of 22, and travelled from London to Brisbane. Unlike Hughes, Fisher never lost his original accent and retained a thick Scottish "brogue" for the rest of his life.

After arriving in Brisbane, Fisher made his way to the Burrum River

The Burrum River is a river located in the Wide Bay-Burnett region of Queensland, Australia.

Course and features

The river rises within Lake Lenthall, impounded by Lenthalls Dam at the confluence of several smaller watercourses including Harw ...

coalfields where there were already a number of Scottish miners. He began as an ordinary miner and joined the local miners' union, but after successfully sinking a new shaft at Torbanlea

Torbanlea is a rural town and locality in the Fraser Coast Region, Queensland, Australia. In the the locality of Torbanlea had a population of 791 people.

Geography

The Burrum River forms the western and northern boundary of the locality. T ...

, he was employed as a mine manager. Prospering financially for the first time in his life, he built a timber cottage at Howard

Howard is an English-language given name originating from Old French Huard (or Houard) from a Germanic source similar to Old High German ''*Hugihard'' "heart-brave", or ''*Hoh-ward'', literally "high defender; chief guardian". It is also probabl ...

and began investing in shares. Fisher moved to the larger gold-mining town of Gympie

Gympie ( ) is a city and a Suburbs and localities (Australia), locality in the Gympie Region, Queensland, Australia. In the Wide Bay-Burnett District, Gympie is about north of the state capital, Brisbane. The city lies on the Mary River (Queen ...

in 1888, initially working in the No. 1 North Phoenix mine and then in the South Great Eastern Extended. He continued his involvement in unionism, helping form the Gympie branch of the Amalgamated Miners' Association (AMA) and serving terms as secretary and president. He obtained an engine-driver's certificate in 1891, and was elected president of the related craft union

Craft unionism refers to a model of trade unionism in which workers are organised based on the particular craft or trade in which they work. It contrasts with industrial unionism, in which all workers in the same industry are organized into the s ...

. This new job allowed him to work above-ground, operating the machinery that raised and lowered the cages in the mineshaft. During his time in Gympie, Fisher stayed in a boardinghouse in Red Hill; it is now heritage-listed as " Andrew Fisher's Cottage". He would eventually marry his landlady's daughter, Margaret Irvine.

Within years of arriving in the town, Fisher had become "an important figure in the Gympie labour movement, straddling both its political and industrial wings". He was a founding member of the Gympie cooperative, and in 1891 became the secretary of the Gympie Joint Labour Committee, the local labour council A labour council, trades council or industrial council is an association of labour unions or union branches in a given area. Most commonly, they represent unions in a given geographical area, whether at the district, city, region, or provincial or ...

. He helped establish a branch of the Workers' Political Association, the forerunner of the Labor Party, and served as the inaugural branch president with George Ryland as secretary. In 1892, he represented Gympie at the Labour-in-Politics Convention in Brisbane. He was sacked from his engine-driving job in the same year, and subsequently devoted his full attention to politics.

Queensland politics

In 1891, Fisher was elected as the first president of the Gympie branch of the Labour Party. In 1893, he was elected to theLegislative Assembly of Queensland

The Legislative Assembly of Queensland is the sole chamber of the unicameral Parliament of Queensland established under the Constitution of Queensland. Elections are held every four years and are done by full preferential voting. The Assembl ...

as Labour member for the Electoral district of Gympie

Gympie is an electoral district of the Legislative Assembly in the Australian state of Queensland The electorate is centred on the city of Gympie and stretches north to Rainbow Beach and as far south to Pomona.

The seat is currently held b ...

and by the following year had become Labour's deputy leader in the Legislative Assembly. In his maiden speech, he pushed for a 50% decrease in military spending and declared support for a federation. He was also active in the Amalgamated Miners Union, becoming President of the Gympie branch by 1891.Fisher, Kathleen (2006) "From pit boy to prime minister: Andrew Fisher", in ''National Library of Australia News'', XVI (9), June 2006, p. 16 Another policy area that captured his attention during this term, was the employment of workers from the Pacific Islands in sugar plantations, a practice that Fisher and Labour both strongly opposed. He lost his seat in 1896 following a campaign in which he was charged by his opponent Jacob Stumm

Jacob Stumm (26 August 1853 – 23 January 1921) was an Australian politician. He was a Ministerialist member of the Legislative Assembly of Queensland for the seat of Gympie from 1896 to 1899 and a Commonwealth Liberal Party member of the Aus ...

with being a dangerous revolutionary and an anti-Catholic, accusations that were propagated by the newspaper ''Gympie Times''.

The 1896 establishment of the ''Gympie Truth'', a newspaper that he was to partly own, was part of his response. Intended as a medium to broadcast Labour's message, the newspaper played a vital role in Fisher's return to parliament in 1899. This time, he was the beneficiary of a scare campaign, in which conservative candidate Francis Power was consistently painted by the ''Gympie Truth'' as being a supporter of black labour and the alleged economic and social ills that accompanied it. In that year he was Secretary for Railways and Public Works in the seven-day government of Anderson Dawson

Andrew Dawson (16 July 1863 – 20 July 1910), usually known as Anderson Dawson, was an Australian politician, the Premier of Queensland for one week (1–7 December) in 1899. This short-lived premiership was the first Australian Labor Party go ...

, the first parliamentary Labour government in the world.

Federal politics

The state Labour parties and their MPs were mixed in their support for theFederation of Australia

The Federation of Australia was the process by which the six separate British self-governing colonies of Queensland, New South Wales, Victoria, Tasmania, South Australia (which also governed what is now the Northern Territory), and Western A ...

. However Fisher was a firm believer in federation, supporting the union of the Australian colonies and campaigned for the 'Yes' vote in Queensland's 1899 referendum. Fisher stood for the Division of Wide Bay

The Division of Wide Bay is an Australian electoral division in the state of Queensland.

Geography

Since 1984, federal electoral division boundaries in Australia have been determined at redistributions by a redistribution committee appointed ...

at the inaugural 1901 Australian federal election and won the seat, which he held continuously for the rest of his political career. At the end of 1901, Fisher married Margaret Irvine, his previous landlady's daughter.

Fisher supported the White Australia policy

The White Australia policy is a term encapsulating a set of historical policies that aimed to forbid people of non-European ethnic origin, especially Asians (primarily Chinese) and Pacific Islanders, from immigrating to Australia, starting i ...

but also argued that any Kanaka who had converted to Christianity and married should be allowed to remain in Australia.

Labour improved their position at the 1903 election, gaining enough seats to be on par with the other two, a legislative time colloquially known as the "three elevens". When the Deakin government resigned in 1904, George Reid

Sir George Houston Reid, (25 February 1845 – 12 September 1918) was an Australian politician who led the Reid Government as the fourth Prime Minister of Australia from 1904 to 1905, having previously been Premier of New South Wales f ...

of the Free Trade Party declined to take office, resulting in Labour taking power and Chris Watson becoming Labour's first Prime Minister for a four-month period in 1904. Fisher established and demonstrated his ministerial capabilities as Minister for Trade and Customs in the Watson Ministry

The Watson ministry ( Labour) was the 3rd ministry of the Government of Australia, and the first national Labour government formed in the world. It was led by the country's 3rd Prime Minister, Chris Watson. The Watson ministry succeeded the ...

. The fourth Labour member in the ministry after Watson, Hughes, and Lee Batchelor

Egerton Lee Batchelor (10 April 1865 – 8 October 1911) was an Australian politician and trade unionist. He was a pioneer of the Australian Labor Party (ALP) in South Australia, which at the time was known as the United Labor Party (ULP). He w ...

, Fisher was promoted to Deputy Leader of the Labour Party in 1905.

George Reid

Sir George Houston Reid, (25 February 1845 – 12 September 1918) was an Australian politician who led the Reid Government as the fourth Prime Minister of Australia from 1904 to 1905, having previously been Premier of New South Wales f ...

adopted a strategy of trying to reorient the party system along Labour vs non-Labour lines – prior to the 1906 election, he renamed his Free Trade Party to the Anti-Socialist Party. Reid envisaged a spectrum running from socialist to anti-socialist, with the Protectionist Party

The Protectionist Party or Liberal Protectionist Party was an Australian political party, formally organised from 1887 until 1909, with policies centred on protectionism. The party advocated protective tariffs, arguing it would allow Australi ...

in the middle. This attempt struck a chord with politicians who were steeped in the Westminster tradition and regarded a two-party system

A two-party system is a political party system in which two major political parties consistently dominate the political landscape. At any point in time, one of the two parties typically holds a majority in the legislature and is usually referre ...

as very much the norm.

Party leader

At the 1906 election, Deakin remained Prime Minister even though Labour gained considerably more seats than the Protectionists. When Watson resigned in 1907, Fisher succeeded him as Labour leader, although Hughes andWilliam Spence

William Guthrie Spence (7 August 1846 – 13 December 1926), was an Australian trade union leader and politician, played a leading role in the formation of both Australia's largest union, the Australian Workers' Union, and the Australian Labor ...

also stood for the position. Fisher was considered to have a better understanding of economic matters, was better at handling caucus, had better relations with the party organisation and the unions, and was more in touch with party opinion. He did not share Hughes' passion for free trade or that of Watson and Hughes for defence (and later conscription). In political terms he was a radical, on the left-wing of his party, with a strong sense of Labour's part in British working-class history.

At the 1908 Labour Federal Conference, Fisher argued for female representation in parliament:

With a majority of seats in the Labour-Protectionist government, Labour caucus by early 1908 had become restive as to the future of the Deakin minority government. With the Deakin ministry in trouble, Deakin spoke to Fisher and Watson about a possible coalition, and following a report agreed to it providing Labour had a majority in cabinet, that there was immediate legislation for old-age pension

A pension (, from Latin ''pensiō'', "payment") is a fund into which a sum of money is added during an employee's employment years and from which payments are drawn to support the person's retirement from work in the form of periodic payments ...

s, that New Protection was carried and that at the following election the government would promise a progressive land tax. No coalition was formed, however the pressure from Labour brought about productive change by Deakin: he agreed to a royal commission into the post office, old-age pensions were to be provided from the surplus revenue fund and £250,000 set aside for ships for an Australian Navy

The Royal Australian Navy (RAN) is the principal naval force of the Australian Defence Force (ADF). The professional head of the RAN is Chief of Navy (CN) Vice Admiral Mark Hammond AM, RAN. CN is also jointly responsible to the Minister of ...

. New Protection was declared invalid by the High Court in June, Fisher found the tariff proposals of Deakin unsatisfactory, while caucus was also dissatisfied with the old-age pension proposals. Without Labour support the Deakin government collapsed in November 1908.

During the parliamentary ballots that selected Yass-Canberra as the site of the national capital, in October 1908, Fisher voted consistently for Dalgety.

Prime Ministership

First term (1908–1909)

Fisher formed his only

Fisher formed his only minority government

A minority government, minority cabinet, minority administration, or a minority parliament is a government and Cabinet (government), cabinet formed in a parliamentary system when a political party or Coalition government, coalition of parties do ...

and the First Fisher Ministry

The First Fisher ministry ( Labour) was the 6th ministry of the Government of Australia. It was led by the country's 5th Prime Minister, Andrew Fisher. The First Fisher ministry succeeded the Second Deakin ministry, which dissolved on 13 Nov ...

. The government passed the Seat of Government Act 1908

The Seat of Government Act 1908 was enacted by the Australian Government on 14 December 1908. The act selected the Yass-Queanbeyan region as the site for Canberra, the new capital city of Australia.

The act repealed the earlier '' Seat of Gover ...

, providing for the new federal capital to be in the Yass-Canberra

Canberra ( )

is the capital city of Australia. Founded following the federation of the colonies of Australia as the seat of government for the new nation, it is Australia's largest inland city and the eighth-largest city overall. The ci ...

area, passed the Manufacturers' Encouragement Act to provide bounties for iron and steel manufacturers who paid fair and reasonable wages, ordered three torpedo boat

A torpedo boat is a relatively small and fast naval ship designed to carry torpedoes into battle. The first designs were steam-powered craft dedicated to ramming enemy ships with explosive spar torpedoes. Later evolutions launched variants of se ...

destroyers

In navy, naval terminology, a destroyer is a fast, manoeuvrable, long-endurance warship intended to escort

larger vessels in a Naval fleet, fleet, convoy or Carrier battle group, battle group and defend them against powerful short range attack ...

, and assumed local naval defence responsibility and placed the Australian Navy

The Royal Australian Navy (RAN) is the principal naval force of the Australian Defence Force (ADF). The professional head of the RAN is Chief of Navy (CN) Vice Admiral Mark Hammond AM, RAN. CN is also jointly responsible to the Minister of ...

at the disposal of the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

in wartime.

Fisher committed Labour to amending the Constitution to give the Commonwealth power over labour

Labour or labor may refer to:

* Childbirth, the delivery of a baby

* Labour (human activity), or work

** Manual labour, physical work

** Wage labour, a socioeconomic relationship between a worker and an employer

** Organized labour and the labour ...

, wages and prices, to expanding the navy and providing compulsory military training for youths, to extending pension

A pension (, from Latin ''pensiō'', "payment") is a fund into which a sum of money is added during an employee's employment years and from which payments are drawn to support the person's retirement from work in the form of periodic payments ...

s, to a land tax, to the construction of a transcontinental railway

A transcontinental railroad or transcontinental railway is contiguous railroad trackage, that crosses a continental land mass and has terminals at different oceans or continental borders. Such networks can be via the tracks of either a single ...

, to the replacement of pound sterling

Sterling (abbreviation: stg; Other spelling styles, such as STG and Stg, are also seen. ISO code: GBP) is the currency of the United Kingdom and nine of its associated territories. The pound ( sign: £) is the main unit of sterling, and t ...

with Australian currency and to tariff

A tariff is a tax imposed by the government of a country or by a supranational union on imports or exports of goods. Besides being a source of revenue for the government, import duties can also be a form of regulation of foreign trade and poli ...

s to protect the sugar industry. In May 1909, the more conservative Protectionists and Freetraders merged to form the Commonwealth Liberal Party

The Liberal Party was a parliamentary party in Australian federal politics between 1909 and 1917. The party was founded under Alfred Deakin's leadership as a merger of the Protectionist Party and Anti-Socialist Party, an event known as the Fus ...

, while the more liberal Protectionists joined Labour. With a majority of seats, the CLP led by Alfred Deakin

Alfred Deakin (3 August 1856 – 7 October 1919) was an Australian politician who served as the second Prime Minister of Australia. He was a leader of the movement for Federation, which occurred in 1901. During his three terms as prime ministe ...

ousted Labour from office, with Fisher failing to persuade the Governor-General Lord Dudley to dissolve Parliament.

Second term (1910–1913)

At the 1910 election, Labour gained sixteen additional seats to hold a total of forty-two of the seventy-five House of Representatives' seats, and all eighteen Senate seats up for election to hold a total of twenty-two out of thirty-six seats. This gave Labour control of both upper and lower houses and enabled Fisher to form his Second Fisher Ministry, Australia's first elected federalmajority government

A majority government is a government by one or more governing parties that hold an absolute majority of seats in a legislature. This is as opposed to a minority government, where the largest party in a legislature only has a plurality of seats. ...

, Australia's first elected Senate majority, and the world's first Labour Party majority government. The 113 acts passed in the three years of the second Fisher government exceeded even the output of the second Deakin government over a similar period. The 1910–13 Fisher government represented the culmination of Labour's involvement in politics, and was a period of reform unmatched in the Commonwealth until the 1940s, under John Curtin

John Curtin (8 January 1885 – 5 July 1945) was an Australian politician who served as the 14th prime minister of Australia from 1941 until his death in 1945. He led the country for the majority of World War II, including all but the last few ...

and Ben Chifley

Joseph Benedict Chifley (; 22 September 1885 – 13 June 1951) was an Australian politician who served as the 16th prime minister of Australia from 1945 to 1949. He held office as the leader of the Australian Labor Party (ALP) from 1945, follow ...

. The Fisher government carried out many reforms in defence, finance, transport and communications, and social security, achieving the vast majority of their aims in just three years of government. These included extending old-age and disability pensions, introducing a maternity

]

A mother is the female parent of a child. A woman may be considered a mother by virtue of having given birth, by raising a child who may or may not be her biological offspring, or by supplying her ovum for fertilisation in the case of gesta ...

allowance and issuing Australia's first paper currency

A banknote—also called a bill (North American English), paper money, or simply a note—is a type of negotiable promissory note, made by a bank or other licensed authority, payable to the bearer on demand.

Banknotes were originally issued ...

, forming the Royal Australian Navy

The Royal Australian Navy (RAN) is the principal naval force of the Australian Defence Force (ADF). The professional head of the RAN is Chief of Navy (CN) Vice Admiral Mark Hammond AM, RAN. CN is also jointly responsible to the Minister of ...

, the start of construction of the Trans-Australian Railway

The Trans-Australian Railway, opened in 1917, runs from Port Augusta in South Australia to Kalgoorlie in Western Australia, crossing the Nullarbor Plain in the process. As the only rail freight corridor between Western Australia and the easter ...

, expanding the bench of the High Court of Australia

The High Court of Australia is Australia's apex court. It exercises Original jurisdiction, original and appellate jurisdiction on matters specified within Constitution of Australia, Australia's Constitution.

The High Court was established fol ...

, the founding of Canberra

Canberra ( )

is the capital city of Australia. Founded following the federation of the colonies of Australia as the seat of government for the new nation, it is Australia's largest inland city and the eighth-largest city overall. The ci ...

, and the establishment of the state-owned Commonwealth Bank

The Commonwealth Bank of Australia (CBA), or CommBank, is an Australian multinational bank with businesses across New Zealand, Asia, the United States and the United Kingdom. It provides a variety of financial services including retail, busines ...

. Fisher's second government also introduced uniform postal charges throughout Australia, carried out measures to break up land monopolies, put forward proposals for closer regulation of working hours, wages and employment conditions, and amended the 1904 Conciliation and Arbitration Act to provide greater authority for the court president, and to allow for Commonwealth employees' industrial unions, registered with the Arbitration Court.

A land tax, aimed at breaking up big estates and give wider scope for small-scale farming, was also introduced, while coverage of the Arbitration system was extended to agricultural workers, domestics, and federal public servants. In addition, the age at which women became entitled to the old-age pension was lowered from sixty-five to sixty. The introduction of the maternity allowance was a major reform, because it enabled more births to be attended by doctors, thus leading to reductions in infant mortality rates. Compulsory preference to trade unionists in federal employment was also introduced, while the Seaman's Compensation Act of 1911 and the Navigation Act of 1912 were enacted to improve conditions for those working at sea, together with compensatory arrangements for seamen and next of kin. Eligibility for pensions was also widened. From December 1912 onwards, naturalised residents no longer had to wait three years to be eligible for a pension. That same year, the value of a pensioner's home was excluded from consideration when assessing the value of their property.

nationalisation

Nationalization (nationalisation in British English) is the process of transforming privately-owned assets into public assets by bringing them under the public ownership of a national government or state. Nationalization usually refers to pri ...

of monopolies

A monopoly (from Greek el, μόνος, mónos, single, alone, label=none and el, πωλεῖν, pōleîn, to sell, label=none), as described by Irving Fisher, is a market with the "absence of competition", creating a situation where a speci ...

. A constitutional referendum was initiated in 1911 which aimed to increase the federal government's legislative powers over trade and commerce and over monopolies. Both questions were defeated, with around 61 per cent voting 'No'. The Fisher government made another attempt, holding a referendum in 1913 which asked for greater federal powers over trade and commerce, corporations, industrial matters, trusts, monopolies, and railway disputes. All six questions were defeated, with around 51 per cent voting 'No'. At the 1913 election, the Commonwealth Liberal Party

The Liberal Party was a parliamentary party in Australian federal politics between 1909 and 1917. The party was founded under Alfred Deakin's leadership as a merger of the Protectionist Party and Anti-Socialist Party, an event known as the Fus ...

, led by Joseph Cook, defeated the Labor Party by a single seat.

Third term (1914–1915)

Labor retained control of theAustralian Senate

The Senate is the upper house of the Bicameralism, bicameral Parliament of Australia, the lower house being the House of Representatives (Australia), House of Representatives. The composition and powers of the Senate are established in Chapter ...

despite defeat. In 1914, Cook, frustrated by the Labor-controlled Senate's rejection of his legislation, recommended to the new Governor-General Sir Ronald Munro Ferguson that both houses of the parliament be dissolved and elections called. This was Australia's first double dissolution

A double dissolution is a procedure permitted under the Australian Constitution to resolve deadlocks in the bicameral Parliament of Australia between the House of Representatives (lower house) and the Senate (upper house). A double dissolution ...

election, and the only one until the 1951 election. The First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

had broken out in the middle of the 1914 election campaign, with both sides committing Australia to the British Empire. Fisher campaigned on Labor's record of support for an independent Australian defence force, and pledged that Australia would "stand beside the mother country to help and defend her to the last man and the last shilling". Labor won the election with another absolute majority in both houses and Fisher formed his third government on 17 September 1914.

Fisher and his party were immediately underway in organising urgent defence measures for planning and implementing Australian war effort. Fisher visited New Zealand during this time which saw

Fisher and his party were immediately underway in organising urgent defence measures for planning and implementing Australian war effort. Fisher visited New Zealand during this time which saw Billy Hughes

William Morris Hughes (25 September 1862 – 28 October 1952) was an Australian politician who served as the seventh prime minister of Australia, in office from 1915 to 1923. He is best known for leading the country during World War I, but ...

serve as acting Prime Minister for two months. Fisher and Labor continued to implement promised peacetime legislation, including the ''River Murray Waters Act 1915'', the ''Freight Arrangements Act 1915'', the ''Sugar Purchase Act 1915'', the ''Estate Duty Assessment'' and the ''Estate Duty'' acts in 1914. Wartime legislation in 1914 and 1915 included the ''War Precautions'' acts (giving the Governor-General power to make regulations for national security), a ''Trading with the Enemy Act'', ''War Census'' acts, a ''Crimes Act'', a ''Belgium Grant Act'', and an ''Enemy Contracts Annulment Act''. In December 1914, a War Pensions Act was passed to provide for the grant of Pensions upon the death or incapacity of Members of the Defence Force of the Commonwealth and Members of the Imperial Reserve Forces residents in Australia whose death or incapacity resulted from their employment in connection with warlike operations.

In October 1915, journalist Keith Murdoch

Sir Keith Arthur Murdoch (12 August 1885 – 4 October 1952) was an Australian journalist, businessman and the father of Rupert Murdoch, the current Executive chairman for News Corporation and the chairman of Fox Corporation.

Early life

Murdoc ...

reported on the situation in Gallipoli

The Gallipoli peninsula (; tr, Gelibolu Yarımadası; grc, Χερσόνησος της Καλλίπολης, ) is located in the southern part of East Thrace, the European part of Turkey, with the Aegean Sea to the west and the Dardanelles ...

at Fisher's request, and advised him, "Your fears have been justified". He described the Dardanelles Expedition as being "a series of disastrous underestimations" and "one of the most terrible chapters in our history" concluding:

Fisher passed this report on to Hughes and to Defence Minister

Fisher passed this report on to Hughes and to Defence Minister George Pearce

Sir George Foster Pearce KCVO (14 January 1870 – 24 June 1952) was an Australian politician who served as a Senator for Western Australia from 1901 to 1938. He began his career in the Labor Party but later joined the National Labor Party, t ...

, ultimately leading to the evacuation of the Australian troops in December 1915. The report was also used by the Dardanelles Commission

The Dardanelles Commission was an investigation into the disastrous 1915 Dardanelles Campaign. It was set up under the Special Commissions (Dardanelles and Mesopotamia) Act 1916. The final report of the commission, issued in 1919, found major p ...

on which Fisher served, while High Commissioner in London.

Fisher resigned as Prime Minister and from Parliament on 27 October 1915 after being absent from parliament without explanation for three sitting days. Three days later, Labor Caucus unanimously elected Billy Hughes

William Morris Hughes (25 September 1862 – 28 October 1952) was an Australian politician who served as the seventh prime minister of Australia, in office from 1915 to 1923. He is best known for leading the country during World War I, but ...

leader of the Federal Parliamentary Party. Fisher's seat was narrowly won by the Commonwealth Liberal Party

The Liberal Party was a parliamentary party in Australian federal politics between 1909 and 1917. The party was founded under Alfred Deakin's leadership as a merger of the Protectionist Party and Anti-Socialist Party, an event known as the Fus ...

on a 0.2% margin at the 1915 Wide Bay by-election.

High Commissioner to the United Kingdom

Fisher served as Australia's secondHigh Commissioner to the United Kingdom

The following is the list of ambassadors and high commissioners to the United Kingdom, or more formally, to the Court of St James's. High commissioners represent member states of the Commonwealth of Nations and ambassadors represent other sta ...

from 1 January 1916 until 1 January 1921. Fisher opposed conscription which made his dealings with Billy Hughes difficult. Hughes asked Fisher for support by cable three weeks before the first referendum, but Fisher cabled back "Am unable to sign appeal. Position forbids." He subsequently refused to publicly comment on the issue. Hughes' 1916 referendum on conscription had a No vote of around 52 per cent, while the 1917 referendum had a No vote of around 54 per cent. Fisher visited Australian troops serving in Belgium and France in 1919, and later presented Pearce with an album of battlefield photos from 1917 and 1918, showing the horrendous conditions experienced by the troops.

The Dardanelles Commission

The Dardanelles Commission was an investigation into the disastrous 1915 Dardanelles Campaign. It was set up under the Special Commissions (Dardanelles and Mesopotamia) Act 1916. The final report of the commission, issued in 1919, found major p ...

, including Fisher, interviewed witnesses in 1916 and 1917 and issued its final report in 1919. It concluded that the expedition was poorly planned and executed and that difficulties had been underestimated, problems which were exacerbated by supply shortages and by personality clashes and procrastination at high levels. Some 480,000 Allied troops had been dedicated to the failed campaign, with around half in casualties. The report's conclusions were regarded as insipid with no figures (political or military) heavily censured. The report of the commission and information gathered by the inquiry remain a key source of documents on the campaign.

Final years and death

Fisher's term as High Commissioner officially ended on 22 April 1921, although it concluded with three months' paid leave and he left for Australia on 29 January. He arrived back in Melbourne with no firm plans for his future, but the rapturous receptions he received at labour movement gatherings led him to contemplate a return to active politics. He was the only remaining former prime minister in the Labor Party, which had lost many experienced MPs in the 1916 party split. The party's leaderFrank Tudor

Francis Gwynne Tudor (29 January 1866 – 10 January 1922) was an Australian politician who served as the leader of the Australian Labor Party from 1916 until his death. He had previously been a government minister under Andrew Fisher and Billy ...

had had frequent bouts of ill health, and T. J. Ryan

Thomas Joseph Ryan (1 July 1876 – 1 August 1921) was an Australian politician who served as Premier of Queensland from 1915 to 1919, as leader of the state Labor Party. He resigned to enter federal politics, sitting in the House of Represe ...

, who was widely seen as Tudor's heir apparent, died suddenly of pneumonia in August 1921. Fisher seriously considered standing in the resulting by-election, but found there was no guarantee that the local party would accept him as a candidate. He was unwilling to actively campaign for preselection, and decided he would only stand if he were drafted; this did not eventuate.

With little else to keep them in Australia, Fisher and his wife decided to return to London to be closer to their children. They rented a property in Highgate

Highgate ( ) is a suburban area of north London at the northeastern corner of Hampstead Heath, north-northwest of Charing Cross.

Highgate is one of the most expensive London suburbs in which to live. It has two active conservation organisati ...

for a period, and then in October 1922 bought a home on South Hill Park

South Hill Park is a English country house and its grounds, now run as an arts centre. It lies in the Birch Hill estate to the south of Bracknell town centre, in Berkshire.

History

Construction by Watts

The original South Hill Park mans ...

near Hampstead Heath

Hampstead Heath (locally known simply as the Heath) is an ancient heath in London, spanning . This grassy public space sits astride a sandy ridge, one of the highest points in London, running from Hampstead to Highgate, which rests on a band o ...

. He explored the possibility of standing for the British House of Commons

The House of Commons is the lower house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Like the upper house, the House of Lords, it meets in the Palace of Westminster in London, England.

The House of Commons is an elected body consisting of 650 mem ...

, but eventually opted for a permanent retirement from politics. By the time he was 60, Fisher's family and friends had begun to notice a decline in his mental faculties, which was probably a form of early-onset dementia

Dementia is a disorder which manifests as a set of related symptoms, which usually surfaces when the brain is damaged by injury or disease. The symptoms involve progressive impairments in memory, thinking, and behavior, which negatively affe ...

. It was judged unsafe for him to be out alone in public, and in 1925 his assets were placed in trust. By 1928, he was unable to sign his own name, and his children were seriously considering having him institutionalised. Fisher contracted a severe case of influenza in September 1928, and eventually died from complications of the disease on 22 October, aged 66. He is one of only three Australian prime ministers to die overseas, and he and George Reid

Sir George Houston Reid, (25 February 1845 – 12 September 1918) was an Australian politician who led the Reid Government as the fourth Prime Minister of Australia from 1904 to 1905, having previously been Premier of New South Wales f ...

are the only ones who both began and ended their lives outside Australia.

Fisher was buried at Hampstead Cemetery

Hampstead Cemetery is a historic cemetery in West Hampstead, London, located at the upper extremity of the NW6 district. Despite the name, the cemetery is three-quarters of a mile from Hampstead Village, and bears a different postcode. It is jo ...

on 26 October 1928. On the same day, a memorial service was held at St Columba's Church, London, which was attended by representatives of King George V

George V (George Frederick Ernest Albert; 3 June 1865 – 20 January 1936) was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 6 May 1910 until Death and state funeral of George V, his death in 1936.

Born duri ...

and Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin

Stanley Baldwin, 1st Earl Baldwin of Bewdley, (3 August 186714 December 1947) was a British Conservative Party politician who dominated the government of the United Kingdom between the world wars, serving as prime minister on three occasions, ...

, as well as Arthur Henderson

Arthur Henderson (13 September 1863 – 20 October 1935) was a British iron moulder and Labour politician. He was the first Labour cabinet minister, won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1934 and, uniquely, served three separate terms as Leader of th ...

representing the British Labour Party. In February 1930, Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald unveiled a granite obelisk above Fisher's grave. His widow eventually moved back to Australia, dying there in 1958.

Evaluation

Despite the length of Fisher's service as prime minister, for many years he and his government were given relatively little scholarly attention. His decision to retire to England placed him out of the public eye, while his mental deterioration and early death deprived him of the opportunity to dictate his own legacy. Writers interested in the post-Federation era did not generally view him as an attractive biographical subject, which has been attributed to the relative orthodoxy of his political views and a reputation for propriety to the point of dullness. Fisher's 1981 entry in the ''

Despite the length of Fisher's service as prime minister, for many years he and his government were given relatively little scholarly attention. His decision to retire to England placed him out of the public eye, while his mental deterioration and early death deprived him of the opportunity to dictate his own legacy. Writers interested in the post-Federation era did not generally view him as an attractive biographical subject, which has been attributed to the relative orthodoxy of his political views and a reputation for propriety to the point of dullness. Fisher's 1981 entry in the ''Australian Dictionary of Biography

The ''Australian Dictionary of Biography'' (ADB or AuDB) is a national co-operative enterprise founded and maintained by the Australian National University (ANU) to produce authoritative biographical articles on eminent people in Australia's ...

'' was written by Denis Murphy, who had planned a full-length biography but died in 1984 before completing it. Clem Lloyd also began a biography in the 1990s, which was unfinished at the time of his death in 2001. The first complete biographies of Fisher did not emerge until the 100th anniversary of his prime ministership. These were David Day's ''Andrew Fisher: Prime Minister of Australia'' (2008) and Peter Bastian's ''Andrew Fisher: An Underestimated Man'' (2009), as well as a shorter volume by Edward Humphreys, ''Andrew Fisher: The Forgotten Man'' (2008).

Obituarists of Fisher generally emphasised his modesty, integrity, and dedication to the labour movement. Writing for ''The Australian Worker

''The Australian Worker'' was a newspaper produced in Sydney, New South Wales for the Australian Workers' Union. It was published from 1890 to 1950.

History

The newspaper had its origin in ''The Hummer'', "Official organ of the Associated Ri ...

'', Henry Ernest Boote

Henry Ernest Boote (1865 – 1949) was an Australian editor, journalist, propagandist, poet, and fiction writer.

Wrote ‘A Fool’s Talk’ (1915)

Biography

Born in Liverpool, England, 20 May 1865, Boote began working as an apprentice to a pri ...

praised him as "loyal to his class, courageous in the advocacy of their cause, and absolutely incorruptible". In the decades after his death, a general view emerged of Fisher as a competent rather than brilliant leader. He was praised for successfully managing the conflicting personalities within his own party, but as a leader of his country was often compared unfavourably with Deakin and Hughes. In general, his prime ministership was seen as a relatively inconsequential interlude. However, beginning in the 1970s a different view of Fisher began to emerge, which coincided with more of his personal papers becoming available to researchers. His more recent biographers have credited Fisher with establishing Labor as a viable party of government and demonstrating that the party's platform did not have to be sacrificed for political expediency, and argued that he deserves the primary credit for the political and electoral accomplishments of his governments. He is now generally seen as one of the most significant figures in the early years of his party.

Honours

At the end of the First World War,France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

awarded him the Légion d'honneur

The National Order of the Legion of Honour (french: Ordre national de la Légion d'honneur), formerly the Royal Order of the Legion of Honour ('), is the highest French order of merit, both military and civil. Established in 1802 by Napoleon ...

, but he declined it; he did not like decorations of any kind and adhered to this view throughout his life. In 1911 Fisher declined the offer of honorary degree

An honorary degree is an academic degree for which a university (or other degree-awarding institution) has waived all of the usual requirements. It is also known by the Latin phrases ''honoris causa'' ("for the sake of the honour") or ''ad hono ...

s from the universities of Oxford

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ...

, Cambridge

Cambridge ( ) is a university city and the county town in Cambridgeshire, England. It is located on the River Cam approximately north of London. As of the 2021 United Kingdom census, the population of Cambridge was 145,700. Cambridge bec ...

, Glasgow

Glasgow ( ; sco, Glesca or ; gd, Glaschu ) is the most populous city in Scotland and the fourth-most populous city in the United Kingdom, as well as being the 27th largest city by population in Europe. In 2020, it had an estimated popul ...

and Birmingham

Birmingham ( ) is a city and metropolitan borough in the metropolitan county of West Midlands in England. It is the second-largest city in the United Kingdom with a population of 1.145 million in the city proper, 2.92 million in the West ...

, although he did accept the Freedom of the City

The Freedom of the City (or Borough in some parts of the UK) is an honour bestowed by a municipality upon a valued member of the community, or upon a visiting celebrity or dignitary. Arising from the medieval practice of granting respected ...

from the cities of Glasgow

Glasgow ( ; sco, Glesca or ; gd, Glaschu ) is the most populous city in Scotland and the fourth-most populous city in the United Kingdom, as well as being the 27th largest city by population in Europe. In 2020, it had an estimated popul ...

, Edinburgh

Edinburgh ( ; gd, Dùn Èideann ) is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 Council areas of Scotland, council areas. Historically part of the county of Midlothian (interchangeably Edinburghshire before 1921), it is located in Lothian ...

and Bristol

Bristol () is a city, ceremonial county and unitary authority in England. Situated on the River Avon, it is bordered by the ceremonial counties of Gloucestershire to the north and Somerset to the south. Bristol is the most populous city in ...

.

Another honour Fisher did accept was appointment to the Privy Council of the United Kingdom

The Privy Council (PC), officially His Majesty's Most Honourable Privy Council, is a formal body of advisers to the sovereign of the United Kingdom. Its membership mainly comprises senior politicians who are current or former members of e ...

on his visit to the UK in 1911 for the Coronation of King George V and the Imperial Conference

Imperial Conferences (Colonial Conferences before 1907) were periodic gatherings of government leaders from the self-governing colonies and dominions of the British Empire between 1887 and 1937, before the establishment of regular Meetings of ...

at the same time as New Zealand Prime Minister Sir Joseph Ward and Governor Lord Islington

John Poynder Dickson-Poynder, 1st Baron Islington, (31 October 1866 – 6 December 1936), born John Poynder Dickson and known as Sir John Poynder Dickson-Poynder from 1884 to 1910, was a British politician. He was Governor of New Zealand between ...

, granting him use of "The Right Honourable

''The Right Honourable'' ( abbreviation: ''Rt Hon.'' or variations) is an honorific style traditionally applied to certain persons and collective bodies in the United Kingdom, the former British Empire and the Commonwealth of Nations. The term is ...

". Public reaction to his appointment was positive, with the ''Brisbane Truth

The ''Brisbane Truth'' newspaper was a subsidiary of Sydney ''Truth'', and was launched in 1890.

Digitisation

The paper has been digitised as part of the Australian Newspapers Digitisation Program of the National Library of Australia.

Refere ...

'' noting it would not change his humble nature: "To plain Andrew Fisher, who lately refused to-be decorated with empty, unearned University degrees, a Privy Councillorship has been awarded. This is an honor to which our Prime Minister is justly entitled by reason of his inclusion in the secret councils of the Imperial Conference, which secrets include the private advice, tendered by him to the administrators of and in the administration of his Majesty's Imperial Government." Although admitted as a Privy Counsellor ''in absentia'' on 6 July 1911, it wasn't until 14 February 1916 when he was High Commissioner in London that he formally took his oath of office.

The federal electorate of Fisher

Fisher is an archaic term for a fisherman, revived as gender-neutral.

Fisher, Fishers or The Fisher may also refer to:

Places

Australia

*Division of Fisher, an electoral district in the Australian House of Representatives, in Queensland

*Elect ...

was named after him. A Canberra suburb, Fisher

Fisher is an archaic term for a fisherman, revived as gender-neutral.

Fisher, Fishers or The Fisher may also refer to:

Places

Australia

*Division of Fisher, an electoral district in the Australian House of Representatives, in Queensland

*Elect ...

, was also created in his memory, with its streets reflecting a mining theme in honour of Fisher's occupation before entering public life. Ramsay MacDonald, Britain's first Labour

Labour or labor may refer to:

* Childbirth, the delivery of a baby

* Labour (human activity), or work

** Manual labour, physical work

** Wage labour, a socioeconomic relationship between a worker and an employer

** Organized labour and the labour ...

Prime Minister, unveiled a memorial to Fisher in Hampstead Cemetery in 1930. A memorial garden was also dedicated to Fisher at his birthplace in the late 1970s.

In 1972 he was honoured on a postage stamp

A postage stamp is a small piece of paper issued by a post office, postal administration, or other authorized vendors to customers who pay postage (the cost involved in moving, insuring, or registering mail), who then affix the stamp to the fa ...

bearing his portrait issued by Australia Post

Australia Post, formally the Australian Postal Corporation, is the government business enterprise that provides postal services in Australia. The head office of Australia Post is located in Bourke Street, Melbourne, which also serves as a post o ...

.

In 1992, his home in Gympie ( Andrew Fisher's Cottage) was listed on the Queensland Heritage Register

The Queensland Heritage Register is a heritage register, a statutory list of places in Queensland, Australia that are protected by Queensland legislation, the Queensland Heritage Act 1992. It is maintained by the Queensland Heritage Council. As a ...

.

In 2008, Labor Prime Minister Kevin Rudd

Kevin Michael Rudd (born 21 September 1957) is an Australian former politician and diplomat who served as the 26th prime minister of Australia from 2007 to 2010 and again from June 2013 to September 2013, holding office as the leader of the ...

, who like Fisher is a Queenslander, launched a biography titled ''Andrew Fisher'', written by David Day. In turn, Rudd was presented with an item that once belonged to Fisher - a slightly battered gold pen engraved with Fisher's signature, which had been held in safekeeping for 80 years.

See also

*First Fisher Ministry

The First Fisher ministry ( Labour) was the 6th ministry of the Government of Australia. It was led by the country's 5th Prime Minister, Andrew Fisher. The First Fisher ministry succeeded the Second Deakin ministry, which dissolved on 13 Nov ...

* Second Fisher Ministry

*Third Fisher Ministry

The Third Fisher ministry (Labor) was the 10th ministry of the Government of Australia. It was led by the country's 5th Prime Minister, Andrew Fisher. The Third Fisher ministry succeeded the Cook ministry, which dissolved on 17 September 191 ...

Notes

References

Further reading

;Biographies * * * * ;Book chapters * Hughes, Colin A (1976), ''Mr Prime Minister. Australian Prime Ministers 1901–1972'', Oxford University Press, Melbourne, Victoria, Ch.6. * ;Journal articles * * *External links

Andrew Fisher: a reforming treasurer – treasury.gov.au

National Museum of Australia

The National Museum of Australia, in the national capital Canberra, preserves and interprets Australia's social history, exploring the key issues, people and events that have shaped the nation. It was formally established by the ''National Muse ...

Andrew Fisher – Scaramouche

{{DEFAULTSORT:Fisher, Andrew Prime Ministers of Australia Treasurers of Australia Members of the Cabinet of Australia Australian Leaders of the Opposition Australian Labor Party members of the Parliament of Australia Australian federationists Australian miners Australian trade unionists Members of the Australian House of Representatives for Wide Bay Members of the Australian House of Representatives People from East Ayrshire People from Gympie Scottish emigrants to colonial Australia Australian socialists 1862 births 1928 deaths Members of the Queensland Legislative Assembly High Commissioners of Australia to the United Kingdom Australian Labor Party members of the Parliament of Queensland Leaders of the Australian Labor Party 20th-century Australian politicians Australian members of the Privy Council of the United Kingdom Australian Presbyterians Politicians from Queensland