Afrikaner Organizations on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Afrikaners () are a

Afrikaners () are a

Afrikaners make up approximately 58% of South Africa's white population, based on language used in the home. English speakers – an ethnically diverse group – account for closer to 37%. As in

Afrikaners make up approximately 58% of South Africa's white population, based on language used in the home. English speakers – an ethnically diverse group – account for closer to 37%. As in

The earliest Afrikaner communities in South Africa were formed at the Cape of Good Hope, mainly through the introduction of Dutch colonists, French Huguenot refugees and erstwhile servants of the VOC. During the early colonial period, Afrikaners were generally known as "Christians", "colonists", "emigrants", or ("inhabitants"). Their concept of being rooted in Africa—as opposed to the company's expatriate officialdom—did not find widespread expression until the late eighteenth century.

It is to the ambitions of

The earliest Afrikaner communities in South Africa were formed at the Cape of Good Hope, mainly through the introduction of Dutch colonists, French Huguenot refugees and erstwhile servants of the VOC. During the early colonial period, Afrikaners were generally known as "Christians", "colonists", "emigrants", or ("inhabitants"). Their concept of being rooted in Africa—as opposed to the company's expatriate officialdom—did not find widespread expression until the late eighteenth century.

It is to the ambitions of

Long before the British annexed the Cape Colony, there were already large Dutch-speaking European settlements in the

Long before the British annexed the Cape Colony, there were already large Dutch-speaking European settlements in the

Important as the Trek was to the formation of Boer ethnic identity, so were the running conflicts with various indigenous groups along the way. One conflict central to the construction of Boer identity occurred with the Zulu in the area of present-day

Important as the Trek was to the formation of Boer ethnic identity, so were the running conflicts with various indigenous groups along the way. One conflict central to the construction of Boer identity occurred with the Zulu in the area of present-day

After defeating the Zulu and the recovery of the treaty between Dingane and Retief, the Voortrekkers proclaimed the

After defeating the Zulu and the recovery of the treaty between Dingane and Retief, the Voortrekkers proclaimed the  A significant number of Afrikaners also went as to

A significant number of Afrikaners also went as to  The Boers created sovereign states in what is now South Africa: (the

The Boers created sovereign states in what is now South Africa: (the

Many Boers, who had little love or respect for Britain, objected to the use of the " children from the concentration camps to attack the anti-British Germans, resulting in the Maritz Rebellion of 1914, which was quickly quelled by the government forces.

Some Boers subsequently moved to South West Africa, which was administered by South Africa until its independence in 1990, after which the country adopted the name Namibia.

Many Boers, who had little love or respect for Britain, objected to the use of the " children from the concentration camps to attack the anti-British Germans, resulting in the Maritz Rebellion of 1914, which was quickly quelled by the government forces.

Some Boers subsequently moved to South West Africa, which was administered by South Africa until its independence in 1990, after which the country adopted the name Namibia.

Based on Heese's genealogical research of the period from 1657 to 1867, his study ' ("The Origins of the Afrikaners") estimated an average ethnic admixture for Afrikaners of 35.5% Dutch, 34.4% German, 13.9% French, 7.2% non-European, 2.6% English, 2.8% other European and 3.6% unknown. Heese reached this conclusion by recording all the wedding dates and number of children of each immigrant. He then divided the period between 1657 and 1867 into six thirty-year blocs, and working under the assumption that earlier colonists contributed more to the gene pool, multiplied each child's bloodline by 32, 16, 8, 4, 2 and 1 according to respective period. Heese argued that previous studies wrongly classified some German progenitors as Dutch, although for the purposes of his own study he also reclassified a number of Scandinavian (especially Danish) progenitors as German. Drawing heavily on

Based on Heese's genealogical research of the period from 1657 to 1867, his study ' ("The Origins of the Afrikaners") estimated an average ethnic admixture for Afrikaners of 35.5% Dutch, 34.4% German, 13.9% French, 7.2% non-European, 2.6% English, 2.8% other European and 3.6% unknown. Heese reached this conclusion by recording all the wedding dates and number of children of each immigrant. He then divided the period between 1657 and 1867 into six thirty-year blocs, and working under the assumption that earlier colonists contributed more to the gene pool, multiplied each child's bloodline by 32, 16, 8, 4, 2 and 1 according to respective period. Heese argued that previous studies wrongly classified some German progenitors as Dutch, although for the purposes of his own study he also reclassified a number of Scandinavian (especially Danish) progenitors as German. Drawing heavily on

According to a genetic study in February 2019, almost all Afrikaners have admixture from non-Europeans. The total amount of non-European ancestry - on average - is 4.8%, of which 2.1% are of African ancestry and 2.7% Asian/ Native American ancestry. Among the 77 Afrikaners investigated, 6.5% had more than 10% non-European admixture, 27.3% had between 5 and 10%, 59.7% had between 1 and 5%, and 6.5% below 1%. It appears that some 3.4% of the non-European admixture can be traced to enslaved peoples who were brought to the Cape from other regions during colonial times. Only 1.38% of the admixture is attributed to the local Khoe-San people.

According to a genetic study in February 2019, almost all Afrikaners have admixture from non-Europeans. The total amount of non-European ancestry - on average - is 4.8%, of which 2.1% are of African ancestry and 2.7% Asian/ Native American ancestry. Among the 77 Afrikaners investigated, 6.5% had more than 10% non-European admixture, 27.3% had between 5 and 10%, 59.7% had between 1 and 5%, and 6.5% below 1%. It appears that some 3.4% of the non-European admixture can be traced to enslaved peoples who were brought to the Cape from other regions during colonial times. Only 1.38% of the admixture is attributed to the local Khoe-San people.

Efforts are being made by some Afrikaners to secure

Efforts are being made by some Afrikaners to secure

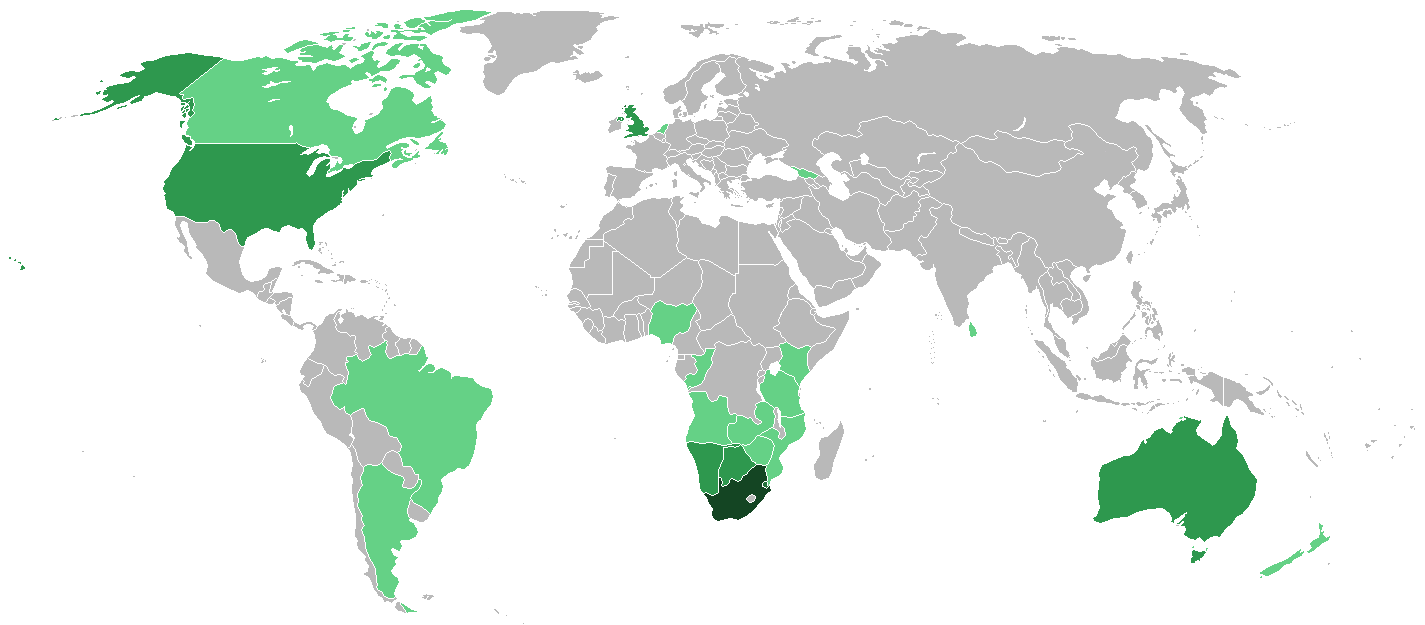

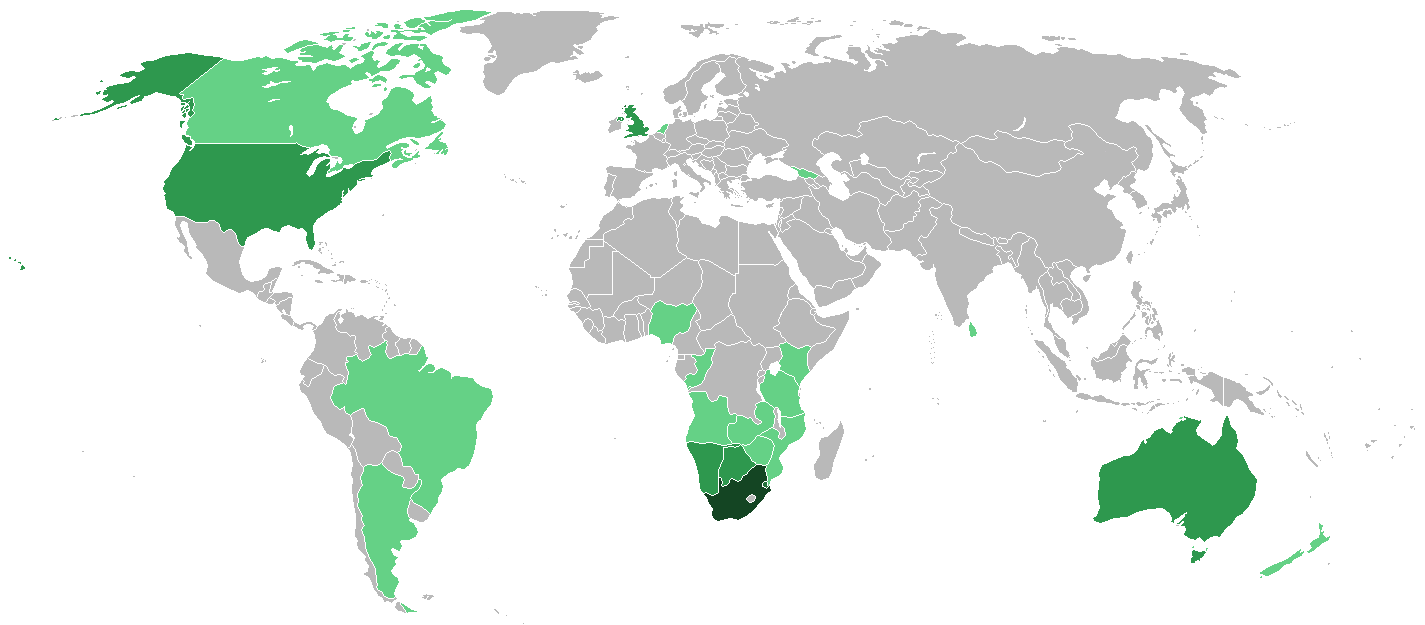

Since 1994, significant numbers of White people have emigrated from South Africa. Large Afrikaner and English-speaking South African communities have developed in the UK and other developed countries. Between 1995 and 2005, more than one million South Africans emigrated overseas, citing the high rate of violent crime. Farmers have also emigrated to other parts of Africa to develop efficient commercial farming there.

Since 1994, significant numbers of White people have emigrated from South Africa. Large Afrikaner and English-speaking South African communities have developed in the UK and other developed countries. Between 1995 and 2005, more than one million South Africans emigrated overseas, citing the high rate of violent crime. Farmers have also emigrated to other parts of Africa to develop efficient commercial farming there.

South Africa – Poor Whites

(Australian Broadcasting Corporation: Foreign Correspondent, transcript)

(Strategy Leader Resource Kit: People Profile)

South Africa

(Rita M. Byrnes, ed. ''South Africa: A Country Study''. Washington: GPO for the Library of Congress, 1996.) {{Authority control Afrikaner people Dutch diaspora in Africa Dutch South African Dutch Cape Colony Ethnic groups in South Africa Ethnic groups in Namibia Ethnic groups in Zimbabwe Members of the Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organization Articles containing video clips

Afrikaners () are a

Afrikaners () are a South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the southernmost country in Africa. It is bounded to the south by of coastline that stretch along the South Atlantic and Indian Oceans; to the north by the neighbouring coun ...

n ethnic group

An ethnic group or an ethnicity is a grouping of people who identify with each other on the basis of shared attributes that distinguish them from other groups. Those attributes can include common sets of traditions, ancestry, language, history, ...

descended from predominantly Dutch settlers first arriving at the Cape of Good Hope

The Cape of Good Hope ( af, Kaap die Goeie Hoop ) ;''Kaap'' in isolation: pt, Cabo da Boa Esperança is a rocky headland on the Atlantic coast of the Cape Peninsula in South Africa.

A common misconception is that the Cape of Good Hope is ...

in the 17th and 18th centuries.Entry: Cape Colony. ''Encyclopædia Britannica Volume 4 Part 2: Brain to Casting''. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. 1933. James Louis Garvin, editor. They traditionally dominated South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the southernmost country in Africa. It is bounded to the south by of coastline that stretch along the South Atlantic and Indian Oceans; to the north by the neighbouring coun ...

's politics and commercial agricultural sector prior to 1994. Afrikaans

Afrikaans (, ) is a West Germanic language that evolved in the Dutch Cape Colony from the Dutch vernacular of Holland proper (i.e., the Hollandic dialect) used by Dutch, French, and German settlers and their enslaved people. Afrikaans gr ...

, South Africa's third most widely spoken home language, evolved as the mother tongue

A first language, native tongue, native language, mother tongue or L1 is the first language or dialect that a person has been exposed to from birth or within the critical period. In some countries, the term ''native language'' or ''mother tong ...

of Afrikaners and most Cape Coloureds

Cape Coloureds () are a South African ethnic group consisted primarily of persons of mixed race and Khoisan descent. Although Coloureds form a minority group within South Africa, they are the predominant population group in the Western Cape.

...

. It originated from the Dutch vernacular of South Holland

South Holland ( nl, Zuid-Holland ) is a province of the Netherlands with a population of over 3.7 million as of October 2021 and a population density of about , making it the country's most populous province and one of the world's most densely ...

, incorporating words brought from the Dutch East Indies

The Dutch East Indies, also known as the Netherlands East Indies ( nl, Nederlands(ch)-Indië; ), was a Dutch colony consisting of what is now Indonesia. It was formed from the nationalised trading posts of the Dutch East India Company, whic ...

(now Indonesia

Indonesia, officially the Republic of Indonesia, is a country in Southeast Asia and Oceania between the Indian and Pacific oceans. It consists of over 17,000 islands, including Sumatra, Java, Sulawesi, and parts of Borneo and New Gui ...

) and Madagascar

Madagascar (; mg, Madagasikara, ), officially the Republic of Madagascar ( mg, Repoblikan'i Madagasikara, links=no, ; french: République de Madagascar), is an island country in the Indian Ocean, approximately off the coast of East Afric ...

by slaves. Afrikaners make up approximately 5.2% of the total South African population, based upon the number of White South African

White South Africans generally refers to South Africans of European descent. In linguistic, cultural, and historical terms, they are generally divided into the Afrikaans-speaking descendants of the Dutch East India Company's original settler ...

s who speak Afrikaans as a first language in the South African National Census of 2011.

The arrival of Portuguese explorer Vasco da Gama

Vasco da Gama, 1st Count of Vidigueira (; ; c. 1460s – 24 December 1524), was a Portuguese explorer and the first European to reach India by sea.

His initial voyage to India by way of Cape of Good Hope (1497–1499) was the first to link ...

at Calicut

Kozhikode (), also known in English as Calicut, is a city along the Malabar Coast in the state of Kerala in India. It has a corporation limit population of 609,224 and a metropolitan population of more than 2 million, making it the second ...

, India, in 1498 opened a gateway of free access to Asia from Western Europe

Western Europe is the western region of Europe. The region's countries and territories vary depending on context.

The concept of "the West" appeared in Europe in juxtaposition to "the East" and originally applied to the ancient Mediterranean ...

around the Cape of Good Hope; however, it also necessitated the founding and safeguarding of trade stations in the East. The Portuguese landed in Mossel Bay

Mossel Bay ( af, Mosselbaai) is a harbour town of about 99,000 people on the Southern Cape (or Garden Route) of South Africa. It is an important tourism and farming region of the Western Cape Province. Mossel Bay lies 400 kilometres east of the ...

in 1500, explored Table Bay

Table Bay (Afrikaans: ''Tafelbaai'') is a natural bay on the Atlantic Ocean overlooked by Cape Town (founded 1652 by Van Riebeeck) and is at the northern end of the Cape Peninsula, which stretches south to the Cape of Good Hope. It was named b ...

two years later, and by 1510 had started raiding inland. Shortly afterwards the Dutch Republic

The United Provinces of the Netherlands, also known as the (Seven) United Provinces, officially as the Republic of the Seven United Netherlands ( Dutch: ''Republiek der Zeven Verenigde Nederlanden''), and commonly referred to in historiograph ...

sent merchant vessels to India, and in 1602 founded the ('Dutch East India Company'; VOC). As the volume of traffic rounding the Cape increased, VOC recognised its natural harbour as an ideal watering point for the long voyage around Africa to the Orient and established a victualling station there in 1652. VOC officials did not favour the permanent settlement

The Permanent Settlement, also known as the Permanent Settlement of Bengal, was an agreement between the East India Company and Bengali landlords to fix revenues to be raised from land that had far-reaching consequences for both agricultural met ...

of Europeans in their trading empire, although during the 140 years of Dutch rule many VOC servants retired or were discharged and remained as private citizens. Furthermore, the exigencies of supplying local garrisons and passing fleets compelled the administration to confer free status upon employees and oblige them to become independent farmers.

Encouraged by the success of this experiment, the Company extended free passage from 1685 to 1707 for Hollanders wishing to settle at the Cape. In 1688, it sponsored the immigration of 200 French

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with Franc ...

Huguenot

The Huguenots ( , also , ) were a religious group of French Protestants who held to the Reformed, or Calvinist, tradition of Protestantism. The term, which may be derived from the name of a Swiss political leader, the Genevan burgomaster Be ...

refugees forced into exile by the Edict of Fontainebleau

The Edict of Fontainebleau (22 October 1685) was an edict issued by French King Louis XIV and is also known as the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes. The Edict of Nantes (1598) had granted Huguenots the right to practice their religion without ...

. The terms under which the Huguenots agreed to immigrate were the same offered to other VOC subjects, including free passage and requisite farm equipment on credit. Prior attempts at cultivating vineyards or exploiting olive groves for fruit had been unsuccessful, and it was hoped that Huguenot colonists accustomed to Mediterranean agriculture could succeed where the Dutch had failed.Theale, George McCall (4 May 1882). ''Chronicles of Cape Commanders, or, An abstract of original manuscripts in the Archives of the Cape Colony''. Cape Town: WA Richards & Sons 1882. pp 24—387. They were augmented by VOC soldiers returning from Asia, predominantly German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

**Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ge ...

s channeled into Amsterdam by the company's extensive recruitment network and thence overseas. Despite their diverse nationalities, the colonists used a common language and adopted similar attitudes towards politics. The attributes they shared came to serve as a basis for the evolution of Afrikaner identity and consciousness.

Afrikaner nationalism

Afrikaner nationalism ( af, Afrikanernasionalisme) is a nationalistic political ideology which created by Afrikaners residing in Southern Africa during the Victorian era. The ideology was developed in response to the significant events in Afri ...

has taken the form of political parties and secret societies such as the in the twentieth century. In 1914, the National Party was formed to promote Afrikaner economic interests and sever South Africa's ties to the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and ...

. Rising to prominence by winning the 1948 general elections, it was also noted for enforcing a harsh policy of racial segregation (apartheid

Apartheid (, especially South African English: , ; , "aparthood") was a system of institutionalised racial segregation that existed in South Africa and South West Africa (now Namibia) from 1948 to the early 1990s. Apartheid was ...

) while simultaneously declaring South Africa a republic and withdrawing from the British Commonwealth

The Commonwealth of Nations, simply referred to as the Commonwealth, is a political association of 56 member states, the vast majority of which are former territories of the British Empire. The chief institutions of the organisation are the Co ...

. The National Party left power in 1994 following decades of domestic unrest and international sanctions that resulted in bilateral negotiations to end apartheid and South Africa's first multiracial elections held under a universal franchise.

Nomenclature

The term "Afrikaner" (formerly sometimes in the forms or , from the Dutch ) presently denotes the politically, culturally and socially dominant and majority group amongwhite South Africans

White South Africans generally refers to South Africans of European descent. In linguistic, cultural, and historical terms, they are generally divided into the Afrikaans-speaking descendants of the Dutch East India Company's original settle ...

, or the Afrikaans

Afrikaans (, ) is a West Germanic language that evolved in the Dutch Cape Colony from the Dutch vernacular of Holland proper (i.e., the Hollandic dialect) used by Dutch, French, and German settlers and their enslaved people. Afrikaans gr ...

-speaking population of Dutch

Dutch commonly refers to:

* Something of, from, or related to the Netherlands

* Dutch people ()

* Dutch language ()

Dutch may also refer to:

Places

* Dutch, West Virginia, a community in the United States

* Pennsylvania Dutch Country

People E ...

origin. Their original progenitors, especially in paternal lines, also included smaller numbers of Flemish

Flemish (''Vlaams'') is a Low Franconian dialect cluster of the Dutch language. It is sometimes referred to as Flemish Dutch (), Belgian Dutch ( ), or Southern Dutch (). Flemish is native to Flanders, a historical region in northern Belgium; ...

, French Huguenot

The Huguenots ( , also , ) were a religious group of French Protestants who held to the Reformed, or Calvinist, tradition of Protestantism. The term, which may be derived from the name of a Swiss political leader, the Genevan burgomaster Beza ...

, German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

**Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ge ...

, Danish, Norwegian

Norwegian, Norwayan, or Norsk may refer to:

*Something of, from, or related to Norway, a country in northwestern Europe

* Norwegians, both a nation and an ethnic group native to Norway

* Demographics of Norway

*The Norwegian language, including ...

, and Swedish immigrants. Historically, the terms "" and "" have both been used to describe white Afrikaans-speakers as a group; neither is particularly objectionable, but "Afrikaner" has been considered a more appropriate term.

By the late nineteenth century, the term was in common usage in both the Boer republics and in the Cape Colony

The Cape Colony ( nl, Kaapkolonie), also known as the Cape of Good Hope, was a British colony in present-day South Africa named after the Cape of Good Hope, which existed from 1795 to 1802, and again from 1806 to 1910, when it united with ...

. At one time, ''burghers'' denoted Cape Dutch

Cape Dutch, also commonly known as Cape Afrikaners, were a historic socioeconomic class of Afrikaners who lived in the Western Cape during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. The terms have been evoked to describe an affluent, apolitical ...

: those settlers who were influential in the administration, able to participate in urban affairs, and did so regularly. ''Boers

Boers ( ; af, Boere ()) are the descendants of the Dutch-speaking Free Burghers of the eastern Cape frontier in Southern Africa during the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries. From 1652 to 1795, the Dutch East India Company controlled this a ...

'' often referred to the settled ethnic European farmers or to nomadic cattle-herders. During the Batavian Republic

The Batavian Republic ( nl, Bataafse Republiek; french: République Batave) was the successor state to the Republic of the Seven United Netherlands. It was proclaimed on 19 January 1795 and ended on 5 June 1806, with the accession of Louis Bon ...

of 1795–1806, ('citizen') was popularised among Dutch communities both at home and abroad as a popular revolutionary form of address. In South Africa, it remained in use as late as the Second Boer War

The Second Boer War ( af, Tweede Vryheidsoorlog, , 11 October 189931 May 1902), also known as the Boer War, the Anglo–Boer War, or the South African War, was a conflict fought between the British Empire and the two Boer Republics (the So ...

of 1899–1902.

The first recorded instance of a colonist identifying as an Afrikaner occurred in March 1707, during a disturbance in Stellenbosch

Stellenbosch (; )A Universal Pronounc ...

. When the magistrate

The term magistrate is used in a variety of systems of governments and laws to refer to a civilian officer who administers the law. In ancient Rome, a '' magistratus'' was one of the highest ranking government officers, and possessed both judic ...

, Johannes Starrenburg, ordered an unruly crowd to desist, a young white man named Hendrik Biebouw retorted, "" ("I will not leave, I am an African – even if the magistrate were to beat me to death, or put me in jail, I shall not be, nor will I stay, silent!"). Biebouw was flogged for his insolence and later banished to Batavia (present-day Jakarta in Indonesia). The word ''Afrikaner'' is thought to have first been used to classify Cape Coloured

Cape Coloureds () are a South African ethnic group consisted primarily of persons of mixed race and Khoisan descent. Although Coloureds form a minority group within South Africa, they are the predominant population group in the Western C ...

s, or other groups of mixed-race

Mixed race people are people of more than one race or ethnicity. A variety of terms have been used both historically and presently for mixed race people in a variety of contexts, including ''multiethnic'', ''polyethnic'', occasionally ''bi-eth ...

ancestry. Biebouw had numerous "half-caste" (mixed race) siblings and may have identified with Coloureds socially. The growing use of the term appeared to express the rise of a new identity for white South Africans, suggesting for the first time a group identification with the Cape Colony

The Cape Colony ( nl, Kaapkolonie), also known as the Cape of Good Hope, was a British colony in present-day South Africa named after the Cape of Good Hope, which existed from 1795 to 1802, and again from 1806 to 1910, when it united with ...

rather than with an ancestral homeland in Europe.

Afrikaner culture and people are also commonly referred to as ''the Afrikaans'' or ''Afrikaans people''.

Population

1691 estimates

VOC initially had no intention of establishing a permanent European settlement at theCape of Good Hope

The Cape of Good Hope ( af, Kaap die Goeie Hoop ) ;''Kaap'' in isolation: pt, Cabo da Boa Esperança is a rocky headland on the Atlantic coast of the Cape Peninsula in South Africa.

A common misconception is that the Cape of Good Hope is ...

; until 1657 it devoted as little attention as possible to the development or administration of the Dutch Cape Colony

The Cape Colony ( nl, Kaapkolonie) was a Dutch United East India Company (VOC) colony in Southern Africa, centered on the Cape of Good Hope, from where it derived its name. The original colony and its successive states that the colony was inco ...

. From the VOC's perspective, there was little financial incentive to regard the region as anything more than the site of a strategic victualing centre. Furthermore, the Cape was unpopular among VOC employees, who regarded it as a barren and insignificant outpost with little opportunity for advancement.

A small number of longtime VOC employees who had been instrumental in the colony's founding and its first five years of existence, however, expressed interest in applying for grants of land, with the objective of retiring at the Cape as farmers. In time they came to form a class of , also known as (free citizens), former VOC employees who stayed in Dutch territories overseas after serving their contracts. The were to be of Dutch birth (although exceptions were made for some Germans), married, "of good character", and had to undertake to spend at least twenty years in Southern Africa. In March 1657, when the first started receiving their farms, the white population of the Cape was only about 134. Although the soil and climate in Cape Town

Cape Town ( af, Kaapstad; , xh, iKapa) is one of South Africa's three capital cities, serving as the seat of the Parliament of South Africa. It is the legislative capital of the country, the oldest city in the country, and the second largest ...

were suitable for farming, willing immigrants remained in short supply and included a number of orphans, refugees, and foreigners accordingly. From 1688 onward the Cape attracted some French Huguenot

The Huguenots ( , also , ) were a religious group of French Protestants who held to the Reformed, or Calvinist, tradition of Protestantism. The term, which may be derived from the name of a Swiss political leader, the Genevan burgomaster Be ...

s, most of them refugees from the protracted conflict between Protestants and Catholics in France.

South Africa's white population in 1691 has been described as the Afrikaner "parent stock", as no significant effort was made to secure more colonist families after the dawn of the 18th century, and a majority of Afrikaners are descended from progenitors who arrived prior to 1700 in general and the late 1600s in particular. Although some two-thirds of this figure were Dutch-speaking Hollanders, there were at least 150 Huguenots and a nearly equal number of Low German

:

:

:

:

:

(70,000)

(30,000)

(8,000)

, familycolor = Indo-European

, fam2 = Germanic

, fam3 = West Germanic

, fam4 = North Sea Germanic

, ancestor = Old Saxon

, ancestor2 = Middle ...

speakers. Also represented in smaller numbers were Swedes, Danes

Danes ( da, danskere, ) are a North Germanic ethnic group and nationality native to Denmark and a modern nation identified with the country of Denmark. This connection may be ancestral, legal, historical, or cultural.

Danes generally regard t ...

, and Belgians

Belgians ( nl, Belgen; french: Belges; german: Belgier) are people identified with the Kingdom of Belgium, a federal state in Western Europe. As Belgium is a multinational state, this connection may be residential, legal, historical, or cultur ...

.

1754 estimates

In 1754, Cape governorRyk Tulbagh

Ryk Tulbagh (14 May 1699, Utrecht – 11 August 1771, Cape Town) was Governor of the Dutch Cape Colony from 27 February 1751 to 11 August 1771 under the Dutch East India Company (VOC).

Tulbagh was the son of Dirk Tulbagh and Catharina Catte ...

conducted a census of his non-indigenous subjects. White - now outnumbered by slaves brought from West Africa

West Africa or Western Africa is the westernmost region of Africa. The United Nations defines Western Africa as the 16 countries of Benin, Burkina Faso, Cape Verde, The Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Ivory Coast, Liberia, Mali ...

, Mozambique

Mozambique (), officially the Republic of Mozambique ( pt, Moçambique or , ; ny, Mozambiki; sw, Msumbiji; ts, Muzambhiki), is a country located in southeastern Africa bordered by the Indian Ocean to the east, Tanzania to the north, Malawi ...

, Madagascar

Madagascar (; mg, Madagasikara, ), officially the Republic of Madagascar ( mg, Repoblikan'i Madagasikara, links=no, ; french: République de Madagascar), is an island country in the Indian Ocean, approximately off the coast of East Afric ...

and the Dutch East Indies

The Dutch East Indies, also known as the Netherlands East Indies ( nl, Nederlands(ch)-Indië; ), was a Dutch colony consisting of what is now Indonesia. It was formed from the nationalised trading posts of the Dutch East India Company, whic ...

- only totaled about 6,000.

1806 estimates

Following the defeat and collapse of the Dutch Republic duringJoseph Souham

Joseph, comte Souham (30 April 1760 – 28 April 1837) was a French general who fought in the French Revolutionary Wars and the Napoleonic Wars. He was born at Lubersac and died at Versailles. After long service in the French Royal Army, he was ...

's Flanders Campaign

The Flanders Campaign (or Campaign in the Low Countries) was conducted from 20 April 1792 to 7 June 1795 during the first years of the War of the First Coalition. A coalition of states representing the Ancien Régime in Western Europe – Au ...

, William V, Prince of Orange

William V (Willem Batavus; 8 March 1748 – 9 April 1806) was a prince of Orange and the last stadtholder of the Dutch Republic. He went into exile to London in 1795. He was furthermore ruler of the Principality of Orange-Nassau until his death i ...

escaped to the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and ...

and appealed to the British to occupy his colonial possessions until he was restored. Holland's administration was never effectively reestablished; upon a new outbreak of hostilities with France expeditionary forces led by Sir David Baird, 1st Baronet finally permanently imposed British rule when they defeated Cape governor Jan Willem Janssens

Jonkheer Jan Willem Janssens GCMWO (12 October 1762 – 23 May 1838) was a Dutch nobleman, soldier and statesman who served both as the governor of the Dutch Cape Colony and governor-general of the Dutch East Indies.

Early life

Born in Nijme ...

in 1806.

At the onset of Cape Town

Cape Town ( af, Kaapstad; , xh, iKapa) is one of South Africa's three capital cities, serving as the seat of the Parliament of South Africa. It is the legislative capital of the country, the oldest city in the country, and the second largest ...

's annexation to the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts e ...

, the original Afrikaners numbered 26,720 – or 36% of the colony's population.

1936 Census

The South African census of 1936 gave the following breakdown of language speakers of European origin.1960 Census

The South African census of 1960 was the final census undertaken in theUnion of South Africa

The Union of South Africa ( nl, Unie van Zuid-Afrika; af, Unie van Suid-Afrika; ) was the historical predecessor to the present-day Republic of South Africa. It came into existence on 31 May 1910 with the unification of the Cape, Natal, Tr ...

. Ethno-linguistic status of some 15,994,181 South African citizens was projected by various sources through sampling language, religion and race. At least 1.6 million South Africans represented white Afrikaans speakers, or 10% of the total population. They also constituted 9.3% of the population in neighbouring South West Africa

South West Africa ( af, Suidwes-Afrika; german: Südwestafrika; nl, Zuidwest-Afrika) was a territory under South African administration from 1915 to 1990, after which it became modern-day Namibia. It bordered Angola (Portuguese colony before 1 ...

.

1985 Census

According to the South African census of 1985, there were 2,581,080 white Afrikaans speakers then residing in the country, or about 9.4% of the total population.1996 Census

TheSouth African National Census of 1996

The National Census of 1996 was the 1st comprehensive national census of the Republic of South Africa, after the end of Apartheid. It undertook to enumerate every person present in South Africa on the census night at a cost of .

Pre-enumeration

...

was the first census conducted in post-apartheid

Apartheid (, especially South African English: , ; , "aparthood") was a system of institutionalised racial segregation that existed in South Africa and South West Africa (now Namibia) from 1948 to the early 1990s. Apartheid was ...

South Africa. It was calculated on census day and reported a population of 2,558,956 white Afrikaans speakers. The census noted that Afrikaners represented the eighth largest ethnic group in the country, or 6.3% of the total population. Even after the end of Apartheid the ethnic group only fell by 25,000 people.

2001 Census

TheSouth African National Census of 2001

The National Census of 2001 was the 2nd comprehensive national census of the Republic of South Africa, or Post-Apartheid South Africa. It undertook to enumerate every person present in South Africa on the census night between 9–10 October 2001 ...

was the second census conducted in post-apartheid

Apartheid (, especially South African English: , ; , "aparthood") was a system of institutionalised racial segregation that existed in South Africa and South West Africa (now Namibia) from 1948 to the early 1990s. Apartheid was ...

South Africa. It was calculated on 9 October and reported a population of 2,576,184 white Afrikaans speakers. The census noted that Afrikaners represented the eighth largest ethnic group in the country, or 5.7% of the total population.

Distribution

Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by to ...

or the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country Continental United States, primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., ...

, most modern European immigrants elect to learn English and are likelier to identify with those descended from British colonials of the nineteenth century. Aside from coastal pockets in the Eastern Cape

The Eastern Cape is one of the provinces of South Africa. Its capital is Bhisho, but its two largest cities are East London and Gqeberha.

The second largest province in the country (at 168,966 km2) after Northern Cape, it was formed in ...

and KwaZulu-Natal

KwaZulu-Natal (, also referred to as KZN and known as "the garden province") is a province of South Africa that was created in 1994 when the Zulu bantustan of KwaZulu ("Place of the Zulu" in Zulu) and Natal Province were merged. It is loca ...

they remain heavily outnumbered by those of Afrikaans origin.

2011 Census

The South African National Census of 2011 counted 2,710,461white South African

White South Africans generally refers to South Africans of European descent. In linguistic, cultural, and historical terms, they are generally divided into the Afrikaans-speaking descendants of the Dutch East India Company's original settler ...

s who speak Afrikaans as a first language, or approximately 5.23% of the total South African population. The census also showed an increase of 5.21% in Afrikaner population compared to the previous, 2001 census.

History

Early Dutch settlement

The earliest Afrikaner communities in South Africa were formed at the Cape of Good Hope, mainly through the introduction of Dutch colonists, French Huguenot refugees and erstwhile servants of the VOC. During the early colonial period, Afrikaners were generally known as "Christians", "colonists", "emigrants", or ("inhabitants"). Their concept of being rooted in Africa—as opposed to the company's expatriate officialdom—did not find widespread expression until the late eighteenth century.

It is to the ambitions of

The earliest Afrikaner communities in South Africa were formed at the Cape of Good Hope, mainly through the introduction of Dutch colonists, French Huguenot refugees and erstwhile servants of the VOC. During the early colonial period, Afrikaners were generally known as "Christians", "colonists", "emigrants", or ("inhabitants"). Their concept of being rooted in Africa—as opposed to the company's expatriate officialdom—did not find widespread expression until the late eighteenth century.

It is to the ambitions of Prince Henry the Navigator

''Dom'' Henrique of Portugal, Duke of Viseu (4 March 1394 – 13 November 1460), better known as Prince Henry the Navigator ( pt, Infante Dom Henrique, o Navegador), was a central figure in the early days of the Portuguese Empire and in the 15t ...

that historians attribute the discovery of the Cape as a settling ground for Europeans. In 1424, Henry and Fernando de Castro besieged the Canary Islands

The Canary Islands (; es, :es:Canarias, Canarias, ), also known informally as the Canaries, are a Spanish Autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community and archipelago in the Atlantic Ocean, in Macaronesia. At their closest point to ...

, under the impression that they might be of use to further Portuguese expeditions around Africa's coast. Although this attempt was unsuccessful, Portugal's continued interest in the continent made possible the later voyages of Bartholomew Diaz in 1487 and Vasco de Gama ten years later. Diaz made known to the world a "Cape of Storms", rechristened "Good Hope" by John II. As it was desirable to take formal possession of this territory, the Portuguese erected a stone cross in Algoa Bay

Algoa Bay is a maritime bay in the Eastern Cape, South Africa. It is located in the east coast, east of the Cape of Good Hope.

Algoa Bay is bounded in the west by Cape Recife and in the east by Cape Padrone. The bay is up to deep. The harbour c ...

. Da Gama and his successors, however, did not take kindly to the notion, especially following a skirmish with the Khoikhoi

Khoekhoen (singular Khoekhoe) (or Khoikhoi in the former orthography; formerly also '' Hottentots''"Hottentot, n. and adj." ''OED Online'', Oxford University Press, March 2018, www.oed.com/view/Entry/88829. Accessed 13 May 2018. Citing G. S. ...

in 1497, when one of his admirals was wounded.

After the British East India Company

The East India Company (EIC) was an English, and later British, joint-stock company founded in 1600 and dissolved in 1874. It was formed to trade in the Indian Ocean region, initially with the East Indies (the Indian subcontinent and South ...

was founded in 1599, London merchants began to take advantage of the route to India by the Cape. James Lancaster

Sir James Lancaster (c. 1554 – 6 June 1618) was an English privateer and trader of the Elizabethan era.

Life and work

Lancaster came from Basingstoke in Hampshire. In his early life, he was a soldier and a trader in Portugal.

On 10 April 1 ...

, who had visited Robben Island some years earlier, anchored in Table Bay

Table Bay (Afrikaans: ''Tafelbaai'') is a natural bay on the Atlantic Ocean overlooked by Cape Town (founded 1652 by Van Riebeeck) and is at the northern end of the Cape Peninsula, which stretches south to the Cape of Good Hope. It was named b ...

in 1601. By 1614, the British had planted a penal colony on the site, and in 1621 two Englishmen claimed Table Bay on behalf of King James I James I may refer to:

People

*James I of Aragon (1208–1276)

*James I of Sicily or James II of Aragon (1267–1327)

*James I, Count of La Marche (1319–1362), Count of Ponthieu

*James I, Count of Urgell (1321–1347)

*James I of Cyprus (1334–13 ...

, but this action was not ratified. They eventually settled on Saint Helena

Saint Helena () is a British overseas territory located in the South Atlantic Ocean. It is a remote volcanic tropical island west of the coast of south-western Africa, and east of Rio de Janeiro in South America. It is one of three constit ...

as an alternative port of refuge.

Due to the value of the spice trade between Europe and their outposts in the East Indies

The East Indies (or simply the Indies), is a term used in historical narratives of the Age of Discovery. The Indies refers to various lands in the East or the Eastern hemisphere, particularly the islands and mainlands found in and around ...

, Dutch ships began to call sporadically at the Cape in search of provisions after 1598. In 1601, a Captain Paul van Corniden came ashore at St. Sebastion's Bay near Overberg

__NOTOC__

Overberg is a region in South Africa to the east of Cape Town beyond the Hottentots-Holland mountains. It lies along the Western Cape Province's south coast between the Cape Peninsula and the region known as the Garden Route in the ...

. He discovered a small inlet which he named ('Meat Bay'), after the cattle trade, and another ('Fish Bay') after the abundance of fish. Not long afterwards, Admiral Joris van Spilbergen reported catching penguins and sheep on Robben Island.

In 1648, Dutch sailors Leendert Jansz and Nicholas Proot had been shipwrecked in Table Bay and marooned for five months until picked up by a returning ship. During this period they established friendly relations with the locals, who sold them sheep, cattle, and vegetables. Both men presented a report advocating the Table valley as a fort and garden for the VOC fleets.

Under recommendation from Jan van Riebeeck

Johan Anthoniszoon "Jan" van Riebeeck (21 April 1619 – 18 January 1677) was a Dutch navigator and colonial administrator of the Dutch East India Company.

Life

Early life

Jan van Riebeeck was born in Culemborg, as the son of a surgeon. ...

, the Heeren XVII

The United East India Company ( nl, Verenigde Oostindische Compagnie, the VOC) was a chartered company established on the 20th March 1602 by the States General of the Netherlands amalgamating existing companies into the first joint-stock co ...

authorised the establishment of a fort at the Cape, and this the more hurriedly to preempt any further imperial maneuvers by Britain, France or Portugal. Van Riebeeck, his family and seventy to eighty VOC personnel arrived there on 6 April 1652 after a journey of three and a half months. Their immediate task was the establishment of some gardens, "taking for this purpose all the best and richest ground"; following this they were instructed to conduct a survey to determine the best pastureland for the grazing of cattle. By 15 May, they had nearly completed construction on the Castle of Good Hope, which was to be an easily defensible victualing station serving Dutch ships plying the Indian Ocean

The Indian Ocean is the third-largest of the world's five oceanic divisions, covering or ~19.8% of the water on Earth's surface. It is bounded by Asia to the north, Africa to the west and Australia to the east. To the south it is bounded by ...

. Dutch sailors appreciated the mild climate at the Cape, which allowed them to recuperate from their protracted periods of service in the tropical humidity of Southeast Asia. VOC fleets bearing cargo from the "Orient" anchored in the Cape for a month, usually from March or April, when they were resupplied with water and provisions prior to completing their return voyage to the Netherlands.

In extent the new refreshment post was to be kept as confined as possible to reduce administrative expense. Residents would associate amiably with the natives for the sake of livestock trade, but otherwise keep to themselves and their task of becoming self-sufficient. As the VOC's primary goal was merchant enterprise, particularly its shipping network traversing the Atlantic and Indian Oceans between the Netherlands and various ports in Asia, most of its territories consisted of coastal forts, factories, and isolated trading posts dependent entirely on indigenous host states. The exercise of Dutch sovereignty, as well the large scale settlement of Dutch colonists, was therefore extremely limited at these sites. During the VOC's history only two primary exceptions to the rule emerged: the Dutch East Indies

The Dutch East Indies, also known as the Netherlands East Indies ( nl, Nederlands(ch)-Indië; ), was a Dutch colony consisting of what is now Indonesia. It was formed from the nationalised trading posts of the Dutch East India Company, whic ...

and the Cape of Good Hope, through the formation of the .

The VOC operated under a strict corporate hierarchy which allowed it to formally assign classifications to those whom it determined fell within its legal purview. Most Europeans within the VOC's registration and identification system were denoted either as employees or . The legal classifications imposed upon every individual in the Company possessions determined their position in society and conferred restraints upon their actions. VOC ordinances made a clear distinction between the "bonded" period of service, and the period of "freedom" that began once an employment contract ended. In order to ensure former employees could be distinguished from workers still in the service of the company, it was decided to provide them a "letter of freedom", a licence known as a . European employees were repatriated to the Netherlands upon the termination of their contract, unless they successfully applied for a , in which they were charged a small fee and registered as a in a VOC record known collectively as the ('free(dom) books'). Fairly strict conditions were levied on those who aspired to become at the Cape of Good Hope. They had to be married Dutch citizens who were regarded as being "of good character" by the VOC and committed to at least twenty years' residence in South Africa. Reflecting the multi-national nature of the workforce of the early modern trading companies, some foreigners, particularly Germans, were open to consideration as well. If their application for status was successful, the Company granted them plots of farmland of thirteen and a half morgen

A morgen was a unit of measurement of land area in Germany, the Netherlands, Poland, Lithuania and the Dutch colonies, including South Africa and Taiwan. The size of a morgen varies from . It was also used in Old Prussia, in the Balkans, ...

(equal to ), which were tax exempt for twelve years. They were also loaned tools and seeds. The extent of their farming activities, however, remained heavily regulated: for example, the were ordered to focus on the cultivation of grain. Each year their harvest was to be sold exclusively to the VOC at fixed prices. They were forbidden from growing tobacco, producing vegetables for any purpose other than personal consumption, or purchasing cattle from the native Khoikhoi

Khoekhoen (singular Khoekhoe) (or Khoikhoi in the former orthography; formerly also '' Hottentots''"Hottentot, n. and adj." ''OED Online'', Oxford University Press, March 2018, www.oed.com/view/Entry/88829. Accessed 13 May 2018. Citing G. S. ...

at rates which differed from those set by the VOC. With time, these restrictions and other attempts by the VOC to control the settlers resulted in successive generations of and their descendants becoming increasingly localised in their loyalties and national identity, and hostile towards the colonial government.

Around March 1657, Rijcklof van Goens

Rijcklof Volckertsz. van Goens (24 June 1619 – 14 November 1682) was the Governor of Zeylan and Governor-General of the Dutch East Indies. He was the Governor of Zeylan from 12 May 1660 to 1661, then in 1663 and finally from 19 November 1664 ...

, a senior VOC officer appointed as commissioner to the fledgling Dutch Cape Colony

The Cape Colony ( nl, Kaapkolonie) was a Dutch United East India Company (VOC) colony in Southern Africa, centered on the Cape of Good Hope, from where it derived its name. The original colony and its successive states that the colony was inco ...

, ordered Jan van Riebeeck to help more employees succeed as so the company could save on their wages. Although an overwhelming majority of the were farmers, some also stated their intention to seek employment as farm managers, fishermen, wagon-makers, tailors, or hunters. A ship's carpenter was granted a tract of forest, from which he was permitted to sell timber, and one miller from Holland opened his own water-operated corn mill, the first of its kind in Southern Africa. The colony initially did not do well, and many of the discouraged returned to VOC service or sought passage back to the Netherlands to pursue other opportunities. Vegetable gardens were frequently destroyed by storms, and cattle lost in raids by the Khoikhoi, who were known to the Dutch as . There was also an unskilled labour shortage, which the VOC later resolved by bringing slaves from Angola, Madagascar, and the East Indies.

In 1662, van Riebeeck was succeeded by Zacharias Wagenaer as governor of the Cape. Wagenaer was somewhat aloof towards the , whom he dismissed as "sodden, lazy, clumsy louts...since they do not pay proper attention to the laveslent to them, or to their work in the fields, nor to their animals, for that reason seem wedded to the low level and cannot rid themselves of their debts". When Wagenaer arrived, he observed that many of the unmarried were beginning to cohabit with their slaves, with the result that 75% of children born to Cape slaves at the time had a Dutch father. Wagenaer's response was to sponsor the immigration of Dutch women to the colony as potential wives for the settlers. Upon the outbreak of the Second Anglo-Dutch War

The Second Anglo-Dutch War or the Second Dutch War (4 March 1665 – 31 July 1667; nl, Tweede Engelse Oorlog "Second English War") was a conflict between England and the Dutch Republic partly for control over the seas and trade routes, whe ...

, Wagenaer was perturbed by the British capture of New Amsterdam

New Amsterdam ( nl, Nieuw Amsterdam, or ) was a 17th-century Dutch settlement established at the southern tip of Manhattan Island that served as the seat of the colonial government in New Netherland. The initial trading ''factory'' gave rise ...

and attacks on other Dutch outposts in the Americas and on the west African coast. He increased the Cape garrison by about 300 troops and replaced the original earthen fortifications of the Castle of Good Hope with new ones of stone.

In 1672, there were 300 VOC officials, employees, soldiers and sailors at the Cape, compared to only about 64 , 39 of whom were married, with 65 children. By 1687, the number had increased to about 254 , of whom 77 were married, with 231 children. Simon van der Stel, who was appointed governor of the Cape in 1679, reversed the VOC's earlier policy of keeping the colony limited to the confines of the Cape peninsula itself and encouraged Dutch settlement further abroad, resulting in the founding of Stellenbosch

Stellenbosch (; )A Universal Pronounc ...

. Van der Stel persuaded 30 to settle in Stellenbosch and a few years afterwards the town received its own municipal administration and school. The VOC was persuaded to seek more prospective European immigrants for the Cape after local officials noted that the cost of maintaining gardens to provision passing ships could be eliminated by outsourcing to a greater number of . Furthermore, the size of the Cape garrison could be reduced if there were many colonists capable of being called up for militia service as needed.

Following the passage of the Edict of Fontainebleau

The Edict of Fontainebleau (22 October 1685) was an edict issued by French King Louis XIV and is also known as the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes. The Edict of Nantes (1598) had granted Huguenots the right to practice their religion without ...

, the Netherlands

)

, anthem = ( en, "William of Nassau")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of the Netherlands

, established_title = Before independence

, established_date = Spanish Netherl ...

served as a major destination for French Huguenot refugees fleeing persecution at home. In April 1688, the VOC agreed to sponsor the resettlement of over 100 Huguenots at the Cape. Smaller numbers of Huguenots gradually arrived over the next decade, and by 1702 the community numbered close to 200. Between 1689 and 1707 they were augmented by additional numbers of Dutch settlers sponsored by the VOC with grants of land and free passage to Africa. Additionally, there were calls from the VOC administration to sponsor the immigration of more German settlers to the Cape, as long as they were Protestant. VOC pamphlets began circulating in German cities exhorting the urban poor to seek their fortune in southern Africa. Despite the increasing diversity of the colonial population, there was a degree of cultural assimilation due to intermarriage, and the almost universal adoption of the Dutch language. The use of other European languages was discouraged by a VOC edict declaring that Dutch should be the exclusive language of administrative record and education. In 1752, French astronomer Nicolas-Louis de Lacaille

Abbé Nicolas-Louis de Lacaille (; 15 March 171321 March 1762), formerly sometimes spelled de la Caille, was a French astronomer and geodesist who named 14 out of the 88 constellations. From 1750 to 1754, he studied the sky at the Cape of Good ...

visited the Cape and observed that the nearly all the third-generation descendants of the original Huguenot and German settlers spoke Dutch as a first language.

Impact of the British occupation of the Cape

Long before the British annexed the Cape Colony, there were already large Dutch-speaking European settlements in the

Long before the British annexed the Cape Colony, there were already large Dutch-speaking European settlements in the Cape Peninsula

The Cape Peninsula ( af, Kaapse Skiereiland) is a generally mountainous peninsula that juts out into the Atlantic Ocean at the south-western extremity of the African continent. At the southern end of the peninsula are Cape Point and the Ca ...

and beyond; by the time British rule became permanent in 1806, these had a population of over 26,000. There were, however, two distinct subgroups in the population settled under the VOC. The first were itinerant farmers who began to progressively settle further and further inland, seeking better pastures for their livestock and freedom from the VOC's regulations. This community of settlers collectively identified themselves as Boers to describe their agricultural way of life. Their farms were enormous by European standards, as the land was free and relatively underpopulated; they merely had to register them with the VOC, a process that was little more than a formality and became more irrelevant the further the Boers moved inland. A few Boers adopted a semi-nomadic lifestyle permanently and became known as . The Boers were deeply suspicious of the centralised government and increasing complexities of administration at the Cape; they constantly migrated further from the reaches of the colonial officialdom whenever it attempted to regulate their activities. By the mid-eighteenth century the Boers had penetrated almost a thousand kilometres into South Africa's interior beyond the Cape of Good Hope, at which point they encountered the Xhosa people

The Xhosa people, or Xhosa-speaking people (; ) are African people who are direct kinsmen of Tswana people, Sotho people and Twa people, yet are narrowly sub grouped by European as Nguni ethnic group whose traditional homeland is primarily t ...

, who were migrating southwards from the opposite direction. Competition between the two communities over resources on the frontier sparked the Xhosa Wars

The Xhosa Wars (also known as the Cape Frontier Wars or the Kaffir Wars) were a series of nine wars (from 1779 to 1879) between the Xhosa Kingdom and the British Empire as well as Trekboers in what is now the Eastern Cape in South Africa. T ...

. Harsh Boer attitudes towards black Africans were permanently shaped by their contact with the Xhosa, which bred insecurity and fear on the frontier.

The second subgroup of the population became known as the Cape Dutch

Cape Dutch, also commonly known as Cape Afrikaners, were a historic socioeconomic class of Afrikaners who lived in the Western Cape during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. The terms have been evoked to describe an affluent, apolitical ...

and remained concentrated in the southwestern Cape and especially the areas closer to Cape Town. They were likelier to be urban dwellers, more educated, and typically maintained greater cultural ties to the Netherlands than the Boers. The Cape Dutch formed the backbone of the colony's market economy and included the small entrepreneurial class. These colonists had vested economic interests in the Cape peninsula and were not inclined to venture inland because of the great difficulties in maintaining contact with a viable market. This was in sharp contrast with the Boers on the frontier, who lived on the margins of the market economy. For this reason the Cape Dutch could not easily participate in migrations to escape the colonial system, and the Boer strategy of social and economic withdrawal was not viable for them. Their response to grievances with the Cape government was to demand political reform and greater representation, a practice that became commonplace under Dutch and subsequently British rule. In 1779, for example, hundreds of Cape smuggled a petition to Amsterdam demanding an end to VOC corruption and contradictory laws. Unlike the Boers, the contact most Cape Dutch had with black Africans were predominantly peaceful, and their racial attitudes were more paternal than outright hostile.

Meanwhile, the VOC underwent a period of commercial decline beginning in the late eighteenth century which ultimately resulted in its bankruptcy. The company had suffered immense losses to its trade profits as a result of the Fourth Anglo-Dutch War

The Fourth Anglo-Dutch War ( nl, Vierde Engels-Nederlandse Oorlog; 1780–1784) was a conflict between the Kingdom of Great Britain and the Dutch Republic. The war, contemporary with the War of American Independence (1775-1783), broke out o ...

and was heavily in debt with European creditors. In 1794, the Dutch government intervened and assumed formal administration of the Cape Colony. However, events at the Cape were overtaken by turmoil in the Netherlands, which was occupied by Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader wh ...

during the Flanders Campaign

The Flanders Campaign (or Campaign in the Low Countries) was conducted from 20 April 1792 to 7 June 1795 during the first years of the War of the First Coalition. A coalition of states representing the Ancien Régime in Western Europe – Au ...

. This opened the Cape to French naval fleets. To protect her own prosperous maritime shipping routes, Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the northwest coast of continental Europe. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the largest European island and the ninth-largest island in the world. It ...

occupied the fledgling colony by force until 1803. From 1806 to 1814 the Cape was again governed as a British military dependency, whose sole importance to the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against Fr ...

was its strategic relation to Indian maritime traffic. The British formally assumed permanent administrative control around 1815, as a result of the Treaty of Paris.

Relations between some of the colonists and the new British administration quickly soured. The British brought more liberal attitudes towards slavery and treatment of the indigenous peoples to the Cape, which were utterly alien to the colonists. Furthermore, they insisted that the Cape Colony finance its own affairs by taxes levied on the white population, an unpopular measure which bred resentment. By 1812, new attorneys-general and judges had been imported from England and many of the preexisting VOC-era institutions abolished, namely the Dutch magistrate system and the only vestige of representative government at the Cape, the senate. The new judiciary then established circuit courts, which brought colonial authority directly to the frontier. These circuit courts were permitted to try colonists for allegations of abuse of slaves or indentured servants. Most of those tried for these offences were frontier Boers; the charges were usually brought by British missionaries and the courts themselves staffed by unsympathetic and liberal Cape Dutch. The Boers, who perceived most of the charges levelled against them to be flimsy or exaggerated, often refused to answer their court summons.

In 1815, a Cape police unit was dispatched to arrest a Boer for failure to appear in court on charges of cruelty towards indentured Khoisan servants; the colonist fired on the troopers when they entered his property and was killed. The controversy which surrounded the incident led to the abortive Slachter's Nek Rebellion

The Slachter's Nek Rebellion was an uprising by Boers in 1815 on the eastern border of the Cape Colony.

Background

In 1815 a farmer from the eastern border of the Cape Colony, Frederik Bezuidenhout, was summoned to appear before a magistrate's c ...

, in which a number of Boers took up arms against the British. British officials retaliated by hanging five Boers for insurrection. In 1828, the Cape governor declared that all native inhabitants but slaves were to have the rights of citizens, in respect of security and property ownership, on parity with whites. This had the effect of further alienating the Boers. Boer resentment of successive British administrators continued to grow throughout the late 1820s and early 1830s, especially with the official imposition of the English language. This replaced Dutch with English as the language used in the Cape's judicial system, putting the Boers at a disadvantage, as most spoke little or no English at all.

Bridling at what they considered an unwarranted intrusion into their way of life, some in the Boer community began to consider selling their farms and venturing deep into South Africa's unmapped interior to preempt further disputes and live completely independent from British rule. From their perspective, the Slachter's Nek Rebellion had demonstrated the futility of an armed uprising against the new order the British had entrenched at the Cape; one result was that the Boers who might have otherwise been inclined to take up arms began preparing for a mass emigration from the colony instead.

The Great Trek

In the 1830s and 1840s, an organised migration of an estimated 14,000 Boers, known as , across the Cape Colony's frontier began. The departed the colony in a series of parties, taking with them all their livestock and portable property, as well as slaves, and their dependents. They had the skills to maintain their own wagons and firearms, but remained dependent on equally mobile traders for vital commodities such as gunpowder and sugar. Nevertheless, one of their goals was to sever their ties with the Cape's commercial network by gaining access to foreign traders and ports in east Africa, well beyond the British sphere of influence. Many of the Boers who participated in the Great Trek had varying motives. While most were driven by some form of disenchantment with British policies, their secondary objectives ranged from seeking more desirable grazing land for their cattle to a desire to retain slaves after the abolition of slavery at the Cape. The Great Trek also split the Afrikaner community along social and geographical lines, driving a wedge between the and those who remained in the Cape Colony. Only about a fifth of the colony's Dutch-speaking white population at the time participated in the Great Trek. TheDutch Reformed Church

The Dutch Reformed Church (, abbreviated NHK) was the largest Christian denomination in the Netherlands from the onset of the Protestant Reformation in the 16th century until 1930. It was the original denomination of the Dutch Royal Family and ...

, to which most of the Boers belonged, condemned the migration. Despite their hostility towards the British, there were also Boers who chose to remain in the Cape of their own accord. For its part, the distinct Cape Dutch community remained loyal to the British Crown and focused its efforts on building political organisations seeking representative government; its lobbying efforts were partly responsible for the establishment of the Cape Qualified Franchise

The Cape Qualified Franchise was the system of non-racial franchise that was adhered to in the Cape Colony, and in the Cape Province in the early years of the Union of South Africa. Qualifications for the right to vote at parliamentary elections ...

in 1853.

Important as the Trek was to the formation of Boer ethnic identity, so were the running conflicts with various indigenous groups along the way. One conflict central to the construction of Boer identity occurred with the Zulu in the area of present-day

Important as the Trek was to the formation of Boer ethnic identity, so were the running conflicts with various indigenous groups along the way. One conflict central to the construction of Boer identity occurred with the Zulu in the area of present-day KwaZulu-Natal

KwaZulu-Natal (, also referred to as KZN and known as "the garden province") is a province of South Africa that was created in 1994 when the Zulu bantustan of KwaZulu ("Place of the Zulu" in Zulu) and Natal Province were merged. It is loca ...

.

The Boers who entered Natal discovered that the land they wanted came under the authority of the Zulu King , who ruled that part of what subsequently became KwaZulu-Natal. The British had a small port colony (the future Durban) there but were unable to seize the whole of area from the war-ready Zulus, and only kept to the Port of Natal. The Boers found the land safe from the British and sent an un-armed Boer land treaty delegation under Piet Retief

Pieter Mauritz Retief (12 November 1780 – 6 February 1838) was a ''Voortrekker'' leader. Settling in 1814 in the frontier region of the Cape Colony, he assumed command of punitive expeditions in response to raiding parties from the adjacent ...

on 6 February 1838, to negotiate with the Zulu King. The negotiations went well and a contract between Retief and Dingane was signed.

After the signing, however, Dingane's forces surprised and killed the members of the delegation; a large-scale massacre of the Boers followed: see Weenen massacre

The Weenen massacre ( af, Bloukransmoorde) was the massacre of Khoikhoi, Basuto and Voortrekkers by the Zulu Kingdom on 17 February 1838. The massacres occurred at Doringkop, Bloukrans River, Moordspruit, Rensburgspruit and other sites arou ...

. Zulu ('regiments') attacked Boer encampments in the Drakensberg

The Drakensberg (Afrikaans: Drakensberge, Zulu: uKhahlambha, Sotho: Maluti) is the eastern portion of the Great Escarpment, which encloses the central Southern African plateau. The Great Escarpment reaches its greatest elevation – within t ...

foothills at what was later called Blaauwkrans and Weenen

Weenen (Dutch for "wept") is the second oldest European settlement in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. It is situated on the banks of the Bushman River. The farms around the town grow vegetables, lucerne, groundnuts, and citrus fruit.

History

The p ...

, killing women and children along with men. (By contrast, in earlier conflicts the had experienced along the eastern Cape frontier, the Xhosa

Xhosa may refer to:

* Xhosa people, a nation, and ethnic group, who live in south-central and southeasterly region of South Africa

* Xhosa language, one of the 11 official languages of South Africa, principally spoken by the Xhosa people

See als ...

had refrained from harming women and children.)

A commando of 470 men arrived to help the settlers. On 16 December 1838, the under the command of Andries Pretorius

Andries Wilhelmus Jacobus Pretorius (27 November 179823 July 1853) was a leader of the Boers who was instrumental in the creation of the South African Republic, as well as the earlier but short-lived Natalia Republic, in present-day South Afric ...

confronted about 10,000 Zulus at the prepared positions. The Boers had three injuries without any fatalities. Due to the blood of 3,000 slain Zulus that stained the Ncome River

Blood River ( af, Bloedrivier; zu, Ncome) is situated in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. This river has its sources in the hills south-east of Utrecht; leaving the highlands it is joined by two important tributaries that originate in the Schurvebe ...

, the conflict afterwards became known as the Battle of Blood River

The Battle of Blood River (16 December 1838) was fought on the bank of the Ncome River, in what is today KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa between 464 Voortrekkers ("Pioneers"), led by Andries Pretorius, and an estimated 10,000 to 15,000 Zulu. Es ...

.

In present-day South Africa, 16 December remains a celebrated public holiday, initially called "Dingane's Day". After 1952, the holiday was officially recognised and named the Day of the Covenant, changed to Day of the Vow

The Day of the Vow ( af, Geloftedag) is a religious public holiday in South Africa. It is an important day for Afrikaners, originating from the Battle of Blood River on 16 December 1838, before which about 400 Voortrekkers made a promise to God ...

in 1980 (Mackenzie 1999:69) and, after the abolition of apartheid, to Day of Reconciliation in 1994. The Boers saw their victory at the Battle of Blood River as evidence that they had found divine favour for their exodus

Exodus or the Exodus may refer to:

Religion

* Book of Exodus, second book of the Hebrew Torah and the Christian Bible

* The Exodus, the biblical story of the migration of the ancient Israelites from Egypt into Canaan

Historical events

* E ...

from British rule.

Boer republics

Natalia Republic

The Natalia Republic was a short-lived Boer republic founded in 1839 after a Voortrekker victory against the Zulus at the Battle of Blood River. The area was previously named ''Natália'' by Portuguese sailors, due to its discovery on Christ ...

. In 1843, Britain annexed Natal and many Boers trekked inwards again.

Due to the return of British rule, Boers fled to the frontiers to the north-west of the Drakensberg

The Drakensberg (Afrikaans: Drakensberge, Zulu: uKhahlambha, Sotho: Maluti) is the eastern portion of the Great Escarpment, which encloses the central Southern African plateau. The Great Escarpment reaches its greatest elevation – within t ...

mountains, and onto the highveld of the and . These areas were mostly unoccupied due to conflicts in the course of the genocidal wars of the Zulus on the local Basuthu population who used it as summer grazing for their cattle. Some Boers ventured beyond the present-day borders of South Africa, north as far as present-day Zambia and Angola. Others reached the Portuguese colony of Delagoa Bay

Maputo Bay ( pt, Baía de Maputo), formerly also known as Delagoa Bay from ''Baía da Lagoa'' in Portuguese, is an inlet of the Indian Ocean on the coast of Mozambique, between 25° 40' and 26° 20' S, with a length from north to south of over 90&n ...

, later called and subsequently Maputo

Maputo (), formerly named Lourenço Marques until 1976, is the capital, and largest city of Mozambique. Located near the southern end of the country, it is within of the borders with Eswatini and South Africa. The city has a population of 1,0 ...

– the capital of Mozambique.

A significant number of Afrikaners also went as to

A significant number of Afrikaners also went as to Angola

, national_anthem = "Angola Avante"()

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, capital = Luanda

, religion =

, religion_year = 2020

, religion_ref =

, coordinat ...

, where a large group settled on the Huíla Plateau, in Humpata

Humpata is a town and municipality in the province of Huíla, Angola. The municipality had a population of 89,144 in 2014.

Humpata was the primary destination of the Trekboers on the Dorsland Trek in the 1870s. These Afrikaners formed the ma ...

, and smaller communities on the Central Highlands. They constituted a closed community which rejected integration as well as innovation, became impoverished in the course of several decades, and returned to South West Africa

South West Africa ( af, Suidwes-Afrika; german: Südwestafrika; nl, Zuidwest-Afrika) was a territory under South African administration from 1915 to 1990, after which it became modern-day Namibia. It bordered Angola (Portuguese colony before 1 ...

and South Africa in waves.  The Boers created sovereign states in what is now South Africa: (the

The Boers created sovereign states in what is now South Africa: (the South African Republic

The South African Republic ( nl, Zuid-Afrikaansche Republiek, abbreviated ZAR; af, Suid-Afrikaanse Republiek), also known as the Transvaal Republic, was an independent Boer Republic in Southern Africa which existed from 1852 to 1902, when i ...

) and the Orange Free State were the most prominent and lasted the longest.

The discovery of goldfields awakened British interest in the Boer republics, and the two Boer Wars resulted: The First Boer War

The First Boer War ( af, Eerste Vryheidsoorlog, literally "First Freedom War"), 1880–1881, also known as the First Anglo–Boer War, the Transvaal War or the Transvaal Rebellion, was fought from 16 December 1880 until 23 March 1881 betwee ...

(1880–1881) and the Second Boer War

The Second Boer War ( af, Tweede Vryheidsoorlog, , 11 October 189931 May 1902), also known as the Boer War, the Anglo–Boer War, or the South African War, was a conflict fought between the British Empire and the two Boer Republics (the So ...

(1899–1902). The Boers won the first war and retained their independence. The second ended with British victory and annexation of the Boer areas into the British colonies. The British employed scorched earth

A scorched-earth policy is a military strategy that aims to destroy anything that might be useful to the enemy. Any assets that could be used by the enemy may be targeted, which usually includes obvious weapons, transport vehicles, commun ...

tactics and held many Boers in concentration camps

Internment is the imprisonment of people, commonly in large groups, without charges or intent to file charges. The term is especially used for the confinement "of enemy citizens in wartime or of terrorism suspects". Thus, while it can simply ...

as a means to separate commandos from their source of shelter, food and supply. The strategy had its intended effect, but an estimated 27,000 Boers (mainly women and children under sixteen) died in these camps from hunger