Asiento on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The () was a monopoly

The () was a monopoly

/ref> Spain had neither direct access to the African sources of slaves nor the ability to transport them, so the asiento system was a way to ensure a legal supply of Africans to the New World, which brought revenue to the Spanish crown.

Following the establishment of the Portuguese colony of Angola in 1575, and the gradual replacement of

Following the establishment of the Portuguese colony of Angola in 1575, and the gradual replacement of

In the 1650s after Portugal achieved its independence from Spain, Spain denied the asiento to the Portuguese, whom it considered rebels. Spain sought to enter the slave trade directly, sending ships to Angola to purchase slaves. It also toyed with the idea of a military alliance with Kongo, the powerful African kingdom north of Angola. But these ideas were abandoned and the Spanish returned to Portuguese and then Dutch interests to supply slaves. ( Captain Holmes's expedition captured or destroyed all the Dutch settlements on Ghana's coast.) The Spanish awarded large contracts for the asiento to the Genovese banker Grillo in the 1660s and the

In the 1650s after Portugal achieved its independence from Spain, Spain denied the asiento to the Portuguese, whom it considered rebels. Spain sought to enter the slave trade directly, sending ships to Angola to purchase slaves. It also toyed with the idea of a military alliance with Kongo, the powerful African kingdom north of Angola. But these ideas were abandoned and the Spanish returned to Portuguese and then Dutch interests to supply slaves. ( Captain Holmes's expedition captured or destroyed all the Dutch settlements on Ghana's coast.) The Spanish awarded large contracts for the asiento to the Genovese banker Grillo in the 1660s and the

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0922156518000158 Published online by Cambridge University Press: 08 March 2018 * 13 May 1601 – 16 October 1604: João Rodrigues Coutinho. * 16 October 1604 – 27 September 1615: Gonçalo Vaz Coutinho * 27 September 1615 – 1 April 1623: In 1640 the

In 1640 the

In 1661 the Dutch and the Portuguese signed a

In 1661 the Dutch and the Portuguese signed a

/ref> ** [] * In May 1679 the Coymans financed slave transports, organized by Captain Juan Barroso del Pozo, of 9,800 "negros" to Curaçao. * In 1680, Barroso from Seville and Nicolás Porcio, his Venetian son-in-law, became ''asentistas''. * 1682–1688: Juan Barroso del Pozo (–1683) and Nicolás Porcio succeeded in getting the asiento for 6.5 years. It was Porcio who encountered many financial difficulties after the loss of ships and slaves. In 1683 he travelled to Portobelo but was taken, prisoner. He was unable to make his payments to the crown, alleging that the local authorities in Cartagena were working against his interests.Wills, J.E. (2001) ''1688. A Global History'', p. 50. ** 1683 Dutch privateers attacked Veracruz and Cartagena. ** In 1684 Genoa was heavily bombarded by a French fleet as punishment for its alliance with Spain. As a result, the Genoese bankers and traders made new economic and financial links with Louis XIV. * February 1685 – March 1687:

Capitalism in Amsterdam in the 17th century, p. 110-111

/ref> The cash payment to the Spanish government, an indispensable feature of this bargain, was furnished by the Amsterdam house of Coymans. Coymans made an immediate payment towards some frigates for the Spanish navy being built in Amsterdam and an advance on the dues he would be liable for on goods imported to Spanish America. ** Royal Order, signed "El Rey", commanding Don Balthasar Coymans, Don Juan Barrosa and Don Nicolás Porzio to assemble ten Capuchin monks ( Franciscan friars) from either Cadiz or Amsterdam to sail to the coast of Africa to buy slaves, to convert them to Christianity and sell them in the West Indies, 25 March 1685 Balthasar & Johan Coymans. ** ''Carta de Rodrigo Gómez a anuel Diego López de Zúñiga Mendoza Sotomayor, XDuque de Béjar informando de la concesión de un asiento de negros en el Río de la Plata a favor de Baltasar Coymans y pide recomendaciones personales para que su hijo Pedro sea empleado en ese negocio. Menciona también a Gaspar de Rebolledo, Juan Pimentel como Gobernador de Buenos Aires y a

*1701–1713: Governor

*1701–1713: Governor

/ref> The English contractor was required to advance 200,000 pesos (£45,000) to Philip for their share in the trade, to be paid in two equal installments, the first two months after the contract was signed, the second two months after the first. In addition, the company was allowed to send one ship of 500 tons annually to Portobello to engage in normal trade to avoid In 1714 2,680 slaves were carried, and for 1716–17, 13,000 more, but the trade continued to be unprofitable. As the French previously discovered, high costs meant the real profits from the slave trade asiento were in smuggling contraband goods, which evaded import duties and deprived the authorities of much-needed revenue. An import duty of 33 pieces of eight was charged on each slave (although for this purpose two children were counted as one adult slave). In 1718 a declaration of war between England and Spain halted operations under the Asiento until 1721. The company's assets in South America were seized, at a cost claimed by the company to be £300,000. Any prospect of profit from trade, for which the company had purchased ships and had been planning its next ventures, disappeared. Similar conflicts interrupted the contract from 1727 to 1729 and 1739 to 1748. Increasing knowledge of illicit trading by the SSC resulted in the Spanish tightening on-site monitoring in the Americas during the 1730s. The Spanish then proceeded to seek recompense for clandestine trade carried on by the SSC and others under the veil of the supply of Negroes and the annual ship. Thus a key feature of the depredations crisis was the ongoing failure by the SSC to account and report transparently. Spain having raised objections to the ''asiento'' clauses, the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle was supplemented by the Treaty of Madrid (5 October 1750). The matter of the ''asiento'' was not even mentioned in the treaty, as it had lessened in importance to both nations, although both parties had agreed to resolve outstanding concerns at a "proper time and place". The issue was finally settled in 1750 when Britain agreed to renounce its claim to the asiento in exchange for a payment of £100,000 and British trade with

In 1714 2,680 slaves were carried, and for 1716–17, 13,000 more, but the trade continued to be unprofitable. As the French previously discovered, high costs meant the real profits from the slave trade asiento were in smuggling contraband goods, which evaded import duties and deprived the authorities of much-needed revenue. An import duty of 33 pieces of eight was charged on each slave (although for this purpose two children were counted as one adult slave). In 1718 a declaration of war between England and Spain halted operations under the Asiento until 1721. The company's assets in South America were seized, at a cost claimed by the company to be £300,000. Any prospect of profit from trade, for which the company had purchased ships and had been planning its next ventures, disappeared. Similar conflicts interrupted the contract from 1727 to 1729 and 1739 to 1748. Increasing knowledge of illicit trading by the SSC resulted in the Spanish tightening on-site monitoring in the Americas during the 1730s. The Spanish then proceeded to seek recompense for clandestine trade carried on by the SSC and others under the veil of the supply of Negroes and the annual ship. Thus a key feature of the depredations crisis was the ongoing failure by the SSC to account and report transparently. Spain having raised objections to the ''asiento'' clauses, the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle was supplemented by the Treaty of Madrid (5 October 1750). The matter of the ''asiento'' was not even mentioned in the treaty, as it had lessened in importance to both nations, although both parties had agreed to resolve outstanding concerns at a "proper time and place". The issue was finally settled in 1750 when Britain agreed to renounce its claim to the asiento in exchange for a payment of £100,000 and British trade with

/ref> * There was no ''asiento'' during the Austrian War of Succession (1740-1748). *1748-1750: Spain renewed the ''asiento'' with Britain for four years, but it ended with the Treaty of Madrid. The Spanish authorities "restore the slave trade to the sphere of internal law from which it should never have left". By the middle of the 18th century, British Jamaica and French

Atlantic History and the Slave Trade to Spanish America ALEX BORUCKI, DAVID ELTIS, AND DAVID WHEAT. In: AMERICAN HISTORICAL REVIEW APRIL 2015, p. 440

/ref>

The () was a monopoly

The () was a monopoly contract

A contract is a legally enforceable agreement between two or more parties that creates, defines, and governs mutual rights and obligations between them. A contract typically involves the transfer of goods, services, money, or a promise to ...

between the Spanish Crown

, coatofarms = File:Coat_of_Arms_of_Spanish_Monarch.svg

, coatofarms_article = Coat of arms of the King of Spain

, image = Felipe_VI_in_2020_(cropped).jpg

, incumbent = Felipe VI

, incumbentsince = 19 Ju ...

and various merchants for the right to provide African slaves to colonies in the Spanish Americas. The Spanish Empire

The Spanish Empire ( es, link=no, Imperio español), also known as the Hispanic Monarchy ( es, link=no, Monarquía Hispánica) or the Catholic Monarchy ( es, link=no, Monarquía Católica) was a colonial empire governed by Spain and its prede ...

rarely engaged in the trans-Atlantic slave trade directly from Africa itself, choosing instead to contract out the importation to foreign merchants from nations more prominent in that part of the world; typically Portuguese and Genoese, but later the Dutch, French, and British. The Asiento did not concern French

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with Franc ...

or British Caribbean but Spanish America.

The 1479 Treaty of Alcáçovas divided the Atlantic Ocean and other parts of the globe into two zones of influence, Spanish and Portuguese. The Spanish acquired the west side, washing South America and the West Indies, whilst the Portuguese obtained the east side, washing the west coast of Africa - and also the Indian Ocean beyond. The Spanish relied on enslaved African labourers to support their American colonial project, but now lacked any trading or territorial foothold in West Africa, the principal source of slave labour. The Spanish relied on Portuguese slave traders to fill their requirements. The contract was usually obtained by foreign merchant banks that cooperated with local or foreign traders, that specialized in shipping. Different organisations and individuals would bid for the right to hold the .

The original impetus to import enslaved Africans was to relieve the indigenous inhabitants of the colonies from the labour demands of Spanish colonists. The enslavement of Amerindians

The Indigenous peoples of the Americas are the inhabitants of the Americas before the arrival of the European settlers in the 15th century, and the ethnic groups who now identify themselves with those peoples.

Many Indigenous peoples of the A ...

had been halted by the influence of Dominicans such as Bartolomé de las Casas

Bartolomé de las Casas, Dominican Order, OP ( ; ; 11 November 1484 – 18 July 1566) was a 16th-century Spanish Empire, Spanish landowner, friar, priest, and bishop, famed as a historian and social reformer. He arrived in Hispaniola as a layman ...

. Spain gave individual to Portuguese merchants to bring African slaves to South America.

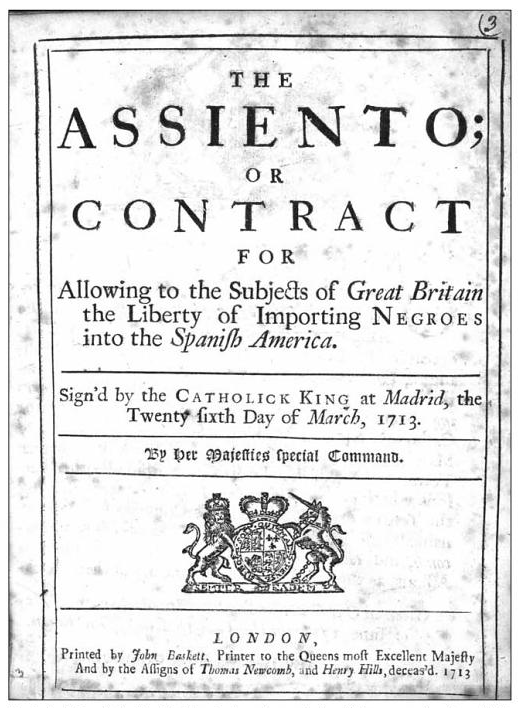

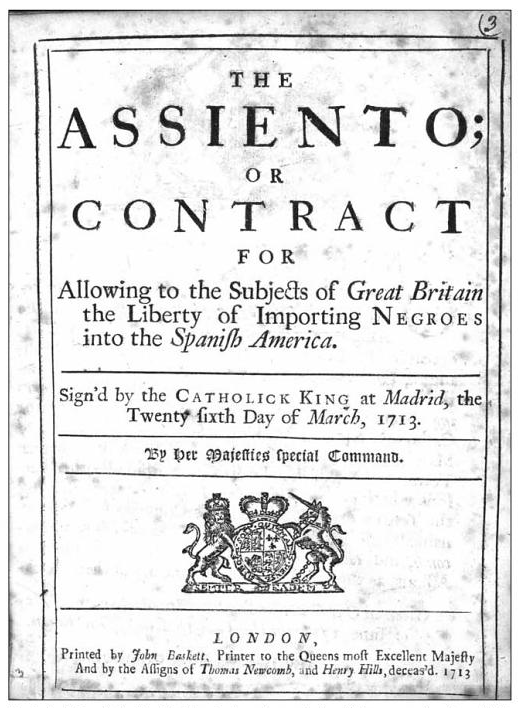

After the Treaty of Münster, in 1648, Dutch merchants became involved in the Asiento de Negros. In 1713, the British were awarded the right to the asiento in the Treaty of Utrecht

The Peace of Utrecht was a series of peace treaties signed by the belligerents in the War of the Spanish Succession, in the Dutch city of Utrecht between April 1713 and February 1715. The war involved three contenders for the vacant throne of ...

, which ended the War of the Spanish Succession

The War of the Spanish Succession was a European great power conflict that took place from 1701 to 1714. The death of childless Charles II of Spain in November 1700 led to a struggle for control of the Spanish Empire between his heirs, Phili ...

. The British government passed its rights to the South Sea Company

The South Sea Company (officially The Governor and Company of the merchants of Great Britain, trading to the South Seas and other parts of America, and for the encouragement of the Fishery) was a British joint-stock company founded in Ja ...

.Haring, ''The Spanish Empire in America'', p. 220. The British ended with the 1750 Treaty of Madrid between Great Britain and Spain after the War of Jenkins' Ear

The War of Jenkins' Ear, or , was a conflict lasting from 1739 to 1748 between Britain and the Spanish Empire. The majority of the fighting took place in New Granada and the Caribbean Sea, with major operations largely ended by 1742. It is con ...

, known appropriately by the Spanish as the ''Guerra del Asiento'' ("War of the Asiento").

An , in the

Spanish language

Spanish ( or , Castilian) is a Romance languages, Romance language of the Indo-European language family that evolved from colloquial Latin spoken on the Iberian peninsula. Today, it is a world language, global language with more than 500 millio ...

, is a short-term loan

In finance, a loan is the lending of money by one or more individuals, organizations, or other entities to other individuals, organizations, etc. The recipient (i.e., the borrower) incurs a debt and is usually liable to pay interest on that ...

or debt contract, of about one to four years, signed between the Spanish crown

, coatofarms = File:Coat_of_Arms_of_Spanish_Monarch.svg

, coatofarms_article = Coat of arms of the King of Spain

, image = Felipe_VI_in_2020_(cropped).jpg

, incumbent = Felipe VI

, incumbentsince = 19 Ju ...

and a banker or a small group of bankers () against future crown revenues, often included after peace treaties

A peace treaty is an agreement between two or more hostile parties, usually countries or governments, which formally ends a state of war between the parties. It is different from an armistice, which is an agreement to stop hostilities; a surre ...

were signed. An covered one or a combination of three specific transactions: an unsecured short-term loan, a transfer of payment, and a currency exchange contract. Between the early 16th and the mid-18th century, were used by the Spanish treasurer

A treasurer is the person responsible for running the treasury of an organization. The significant core functions of a corporate treasurer include cash and liquidity management, risk management, and corporate finance.

Government

The treasury o ...

to adjust short-term imbalances between revenues and expenditures. The sovereign promised to repay the principal of the loan plus high interest (12%). The participant bankers in Seville, Lisbon, Republic of Genoa

The Republic of Genoa ( lij, Repúbrica de Zêna ; it, Repubblica di Genova; la, Res Publica Ianuensis) was a medieval and early modern maritime republic from the 11th century to 1797 in Liguria on the northwestern Italian coast. During the L ...

and Amsterdam, in turn, drew on the profits and direct investments obtained from a large number of Atlantic merchants. In exchange for a set of scheduled payments, merchants and financiers were given the right to collect relevant taxes or oversee the trade in those commodities that fell under the monarch's prerogative. In this way a set of merchants received the right to ship tobacco, salt, sugar and cacao on a trade route

A trade route is a logistical network identified as a series of pathways and stoppages used for the commercial transport of cargo. The term can also be used to refer to trade over bodies of water. Allowing goods to reach distant markets, a sin ...

from the Spanish West Indies

The Spanish West Indies or the Spanish Antilles (also known as "Las Antillas Occidentales" or simply "Las Antillas Españolas" in Spanish language, Spanish) were Spanish colonies in the Caribbean. In terms of governance of the Spanish Empire, The ...

, some times accompanied by licences to export bullion from Spanish Main

During the Spanish colonization of America, the Spanish Main was the collective term for the parts of the Spanish Empire that were on the mainland of the Americas and had coastlines on the Caribbean Sea or Gulf of Mexico. The term was used to di ...

or Cadiz. In particular, the would result in great impact for the economy of Spanish American colonies, because the treaty secured or would secure fixed revenues for the crown and the supply of the region with certain commodities, whereas the contracting party bore the risk of the trade. A new asiento was the safest means to get their money back and cash their arrears.

History of the

Background in the Spanish Americas

The general meaning of (from the Spanish verb , to sit, which was derived from the Latin ) in Spanish is "consent" or "settlement, establishment". In a commercial context, it means "contract, trading agreement". In the words ofGeorges Scelle

Georges Scelle (19 March 1878 Avranches (Manche) – 8 January 1961) was an international jurist and member of the United Nations International Law Commission.

Scelle attended the Law Faculty and the '' École Libre des Sciences Politiques'' in ...

, it was "a term in Spanish public law which designates every contract made for the purpose of public utility...between the Spanish government and private individuals."

The Asiento system was established following Spanish settlement in the Caribbean when the indigenous population was undergoing demographic collapse and the Spanish needed another source of labour. Initially, a few Christian Africans born in Iberia were transported to the Caribbean. But as the indigenous demographic collapse was ongoing and opponents of the Spanish exploitation of indigenous labour grew, including that of Bartolomé de Las Casas

Bartolomé de las Casas, Dominican Order, OP ( ; ; 11 November 1484 – 18 July 1566) was a 16th-century Spanish Empire, Spanish landowner, friar, priest, and bishop, famed as a historian and social reformer. He arrived in Hispaniola as a layman ...

, the young Habsburg king Charles I of Spain allowed for the direct importation of slaves from Africa ('' bozales'') to the Caribbean. The first asiento for selling slaves was drawn up in August 1518, granting a Flemish favourite of Charles, Laurent de Gouvenot, a monopoly on importing enslaved Africans for eight years with a maximum of 4,000. Gouvenot promptly sold his licence to the treasurer of the and three subcontractors, Genoese merchants in Andalusia

Andalusia (, ; es, Andalucía ) is the southernmost autonomous community in Peninsular Spain. It is the most populous and the second-largest autonomous community in the country. It is officially recognised as a "historical nationality". The ...

, for 25,000 ducats. The Casa de Contratación in Seville

Seville (; es, Sevilla, ) is the capital and largest city of the Spanish autonomous community of Andalusia and the province of Seville. It is situated on the lower reaches of the River Guadalquivir, in the southwest of the Iberian Peninsul ...

controlled both trade and immigration to the New World, excluding Jews, '' conversos'', Muslims, and foreigners. African slaves were considered merchandise, and their imports were regulated by the crown. The Spanish crown collected a duty on each " pieza", and not on each individual slave delivered.The Oxford Encyclopedia of Economic History, Volume 5 by Oxford University Press/ref> Spain had neither direct access to the African sources of slaves nor the ability to transport them, so the asiento system was a way to ensure a legal supply of Africans to the New World, which brought revenue to the Spanish crown.

Portuguese monopoly

For the Spanish crown, the asiento was a source of profit. Haring says, "The asiento remained the settled policy of the Spanish government for controlling and profiting from the slave trade." In Habsburg Spain, asientos were a basic method of financing state expenditures: "Borrowing took two forms – long-term debt in the form of perpetual bonds (''juros''), and short-term loan contracts provided by bankers (''asientos''). Many asientos were eventually converted or refinanced through ''juros''." Initially, since Portugal had unimpeded rights in West Africa via its 1494treaty

A treaty is a formal, legally binding written agreement between actors in international law. It is usually made by and between sovereign states, but can include international organizations, individuals, business entities, and other legal perso ...

, it dominated the European slave trade of Africans. Before the onset of the official asiento in 1595, when the Spanish monarch also ruled Portugal in the Iberian Union

pt, União Ibérica

, conventional_long_name =Iberian Union

, common_name =

, year_start = 1580

, date_start = 25 August

, life_span = 1580–1640

, event_start = War of the Portuguese Succession

, event_end = Portuguese Restoration War

, ...

(1580–1640), the Spanish fiscal authorities gave individual asientos to merchants, primarily from Portugal, to bring slaves to the Americas. For the 1560s most of these slaves were obtained in the Upper Guinea area, especially in the Sierra Leone

Sierra Leone,)]. officially the Republic of Sierra Leone, is a country on the southwest coast of West Africa. It is bordered by Liberia to the southeast and Guinea surrounds the northern half of the nation. Covering a total area of , Sierra ...

region where there were many wars associated with the Mandé invasions.

Following the establishment of the Portuguese colony of Angola in 1575, and the gradual replacement of

Following the establishment of the Portuguese colony of Angola in 1575, and the gradual replacement of São Tomé

São Tomé is the capital and largest city of the Central African island country of São Tomé and Príncipe. Its name is Portuguese for " Saint Thomas". Founded in the 15th century, it is one of Africa's oldest colonial cities.

History

Ál ...

by Brazil

Brazil ( pt, Brasil; ), officially the Federative Republic of Brazil (Portuguese: ), is the largest country in both South America and Latin America. At and with over 217 million people, Brazil is the world's fifth-largest country by area ...

as the primary producer of sugar, Angolan interests came to dominate the trade, and it was Portuguese financiers and merchants who obtained the larger-scale, comprehensive asiento that was established in 1595 during the period of the Iberian Union. The asiento was extended to the importation of African slaves to Brazil, with those holding asientos for the Brazilian slave trade often also trading slaves in Spanish America. Spanish America was a major market for African slaves, including many of whom exceeded the quota of the asiento license and were illegally sold. From the period between 1595 and 1622, approximately half of all imported slaves were destined for Mexico. Most smuggled slaves were not brought by freelance traders.

Angolan dominance of the trade was pronounced after 1615 when the governors of Angola, starting with Bento Banha Cardoso, allied with Imbangala mercenaries to wreak havoc on the local African powers. Many of these governors also held the contract of Angola as well as the asiento, thus insuring their interests. Shipping registers from Vera Cruz Veracruz is a state in Mexico. Veracruz or Vera Cruz (literally "True Cross") may also refer to:

People

* María González Veracruz (born 1979), Spanish politician

* Philip Vera Cruz (1904–1994), Filipino American labor leader

* Tomé Vera Cruz ...

and Cartagena show that as many as 85% of the slaves arriving in Spanish ports were from Angola, brought by Portuguese ships. In 1637 the Dutch West India Company employed Portuguese merchants in the trade. The earlier asiento period came to an end in 1640 when Portugal revolted against Spain, though even then the Portuguese continued to supply Spanish colonies.

Dutch, French and British competition

In the 1650s after Portugal achieved its independence from Spain, Spain denied the asiento to the Portuguese, whom it considered rebels. Spain sought to enter the slave trade directly, sending ships to Angola to purchase slaves. It also toyed with the idea of a military alliance with Kongo, the powerful African kingdom north of Angola. But these ideas were abandoned and the Spanish returned to Portuguese and then Dutch interests to supply slaves. ( Captain Holmes's expedition captured or destroyed all the Dutch settlements on Ghana's coast.) The Spanish awarded large contracts for the asiento to the Genovese banker Grillo in the 1660s and the

In the 1650s after Portugal achieved its independence from Spain, Spain denied the asiento to the Portuguese, whom it considered rebels. Spain sought to enter the slave trade directly, sending ships to Angola to purchase slaves. It also toyed with the idea of a military alliance with Kongo, the powerful African kingdom north of Angola. But these ideas were abandoned and the Spanish returned to Portuguese and then Dutch interests to supply slaves. ( Captain Holmes's expedition captured or destroyed all the Dutch settlements on Ghana's coast.) The Spanish awarded large contracts for the asiento to the Genovese banker Grillo in the 1660s and the Dutch West India Company

The Dutch West India Company ( nl, Geoctrooieerde Westindische Compagnie, ''WIC'' or ''GWC''; ; en, Chartered West India Company) was a chartered company of Dutch merchants as well as foreign investors. Among its founders was Willem Usselincx ( ...

in 1675 rather than Portuguese merchants in the 1670s and 1680s. However, this same period saw a resurgence of piracy

Piracy is an act of robbery or criminal violence by ship or boat-borne attackers upon another ship or a coastal area, typically with the goal of stealing cargo and other valuable goods. Those who conduct acts of piracy are called pirates, v ...

. In 1700, with the death of the last Habsburg monarch, Charles II of Spain, his will named the House of Bourbon

The House of Bourbon (, also ; ) is a European dynasty of French origin, a branch of the Capetian dynasty, the royal House of France. Bourbon kings first ruled France and Navarre in the 16th century. By the 18th century, members of the Spanis ...

in the form of Philip V of Spain

Philip V ( es, Felipe; 19 December 1683 – 9 July 1746) was King of Spain from 1 November 1700 to 14 January 1724, and again from 6 September 1724 to his death in 1746. His total reign of 45 years is the longest in the history of the Spanish mon ...

as the successor to the Spanish throne. The Bourbon family were also Kings of France

France was ruled by monarchs from the establishment of the Kingdom of West Francia in 843 until the end of the Second French Empire in 1870, with several interruptions.

Classical French historiography usually regards Clovis I () as the fi ...

and so the asiento was granted in 1702 to the French Guinea Company

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with Fran ...

, for the importation of 48,000 African slaves over a decade. The Africans were transported to the French Caribbean colonies of Martinique and Saint Domingue.

As part of their strategy of maintaining a balance of power in Europe, Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the northwest coast of continental Europe. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the largest European island and the ninth-largest island in the world. It is ...

and her allies, including the Dutch and the Portuguese, disputed the Bourbon inheritance of the Spanish throne and fought in the War of the Spanish Succession

The War of the Spanish Succession was a European great power conflict that took place from 1701 to 1714. The death of childless Charles II of Spain in November 1700 led to a struggle for control of the Spanish Empire between his heirs, Phili ...

against Bourbon hegemony. Although Britain did not prevail, it did receive the ''asiento'' as part of the Peace of Utrecht

The Peace of Utrecht was a series of peace treaties signed by the belligerents in the War of the Spanish Succession, in the Dutch city of Utrecht between April 1713 and February 1715. The war involved three contenders for the vacant throne of ...

.Similar patents in the British system were the Virginia Company

The Virginia Company was an English trading company chartered by King James I on 10 April 1606 with the object of colonizing the eastern coast of America. The coast was named Virginia, after Elizabeth I, and it stretched from present-day Mai ...

, the Levant Company

The Levant Company was an English chartered company formed in 1592. Elizabeth I of England approved its initial charter on 11 September 1592 when the Venice Company (1583) and the Turkey Company (1581) merged, because their charters had expired ...

and the Merchant Adventurers' patent of trade with the United Provinces (essentially concurrent with the modern-day Netherlands). An overview of the British system from a Marxist perspective is given by Robert Brenner, on the editorial board of the ''New Left Review

The ''New Left Review'' is a British bimonthly journal covering world politics, economy, and culture, which was established in 1960.

History Background

As part of the British "New Left" a number of new journals emerged to carry commentary on m ...

'', in "''Merchants and Revolution''". This granted Britain a thirty-year ''asiento'' to send one merchant ship to the Spanish port of Portobelo, furnishing 4800 slaves to the Spanish colonies. The ''asiento'' became a conduit for British contraband and smugglers of all kinds, which undermined Spain's attempts to keep a protectionist

Protectionism, sometimes referred to as trade protectionism, is the economic policy of restricting imports from other countries through methods such as tariffs on imported goods, import quotas, and a variety of other government regulations ...

trading system with its American colonies. Disputes connected with it led to the War of Jenkins' Ear

The War of Jenkins' Ear, or , was a conflict lasting from 1739 to 1748 between Britain and the Spanish Empire. The majority of the fighting took place in New Granada and the Caribbean Sea, with major operations largely ended by 1742. It is con ...

(1739). Britain gave up its rights to the asiento after the war, in the Treaty of Madrid of 1750, as Spain was implementing several administrative and economic reforms

Reform ( lat, reformo) means the improvement or amendment of what is wrong, corrupt, unsatisfactory, etc. The use of the word in this way emerges in the late 18th century and is believed to originate from Christopher Wyvill's Association movement ...

. The Spanish Crown bought out the South Sea Company's right to the ''asiento'' that year. The Spanish Crown sought another way to supply African slaves, attempting to liberalize its traffic, trying to shift to a system of the free trade in slaves by Spaniards and foreigners in particular colonial locations. These were Cuba, Santo Domingo, Puerto Rico, and Caracas, all of which used African slaves in large numbers.

Holders of the ''Asiento''

Early: 1518–1595

* 1518–1527: Laurent de Gouvenot (aka Lorenzo de Gorrevod or Garrebod), Governor ofBresse

Bresse () is a former French province. It is located in the regions of Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes and Bourgogne-Franche-Comté of eastern France. The geographical term ''Bresse'' has two meanings: ''Bresse bourguignonne'' (or ''louhannaise''), whi ...

and majordomo of Charles I of Spain

Charles V, french: Charles Quint, it, Carlo V, nl, Karel V, ca, Carles V, la, Carolus V (24 February 1500 – 21 September 1558) was Holy Roman Emperor and Archduke of Austria from 1519 to 1556, King of Spain ( Castile and Aragon) f ...

.Dalla Corte, Gabriela (2006) ''Homogeneidad, Diferencia y Exclusión en América.'' Edicions Universitat Barcelona, The first known transatlantic slave ship—sailed from São Tomé

São Tomé is the capital and largest city of the Central African island country of São Tomé and Príncipe. Its name is Portuguese for " Saint Thomas". Founded in the 15th century, it is one of Africa's oldest colonial cities.

History

Ál ...

in 1525.

** Outsourced to Domingo de Forne, Agustín de Ribaldo and Fernando Vázquez, all Genoese

Genoese may refer to:

* a person from Genoa

* Genoese dialect, a dialect of the Ligurian language

* Republic of Genoa (–1805), a former state in Liguria

See also

* Genovese, a surname

* Genovesi, a surname

*

*

*

*

* Genova (disambiguati ...

established in Seville

Seville (; es, Sevilla, ) is the capital and largest city of the Spanish autonomous community of Andalusia and the province of Seville. It is situated on the lower reaches of the River Guadalquivir, in the southwest of the Iberian Peninsul ...

.

* 1528–1536: The Welser

Welser was a German banking and merchant family, originally a patrician family based in Augsburg and Nuremberg, that rose to great prominence in international high finance in the 16th century as bankers to the Habsburgs and financiers of Charle ...

and Fugger families from Augsburg

Augsburg (; bar , Augschburg , links=https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Swabian_German , label=Swabian German, , ) is a city in Swabia, Bavaria, Germany, around west of Bavarian capital Munich. It is a university town and regional seat of the '' ...

.Cortés López, José Luis (2004) ''Esclavo y Colono.'' Universidad de Salamanca

* 1536–1595: Liberalization

Liberalization or liberalisation (British English) is a broad term that refers to the practice of making laws, systems, or opinions less severe, usually in the sense of eliminating certain government regulations or restrictions. The term is used m ...

.

Portuguese: 1595–1640

Six Asientos were granted to: * 30 January 1595 – 13 May 1601: Pedro Gomes ReynelReinel introduced 25,000 slaves to Brazil in the following six years. This agreement introduced well-defined characteristics in this type of contract. According to its clauses, Reynel was obliged to introduce 4,250 African slaves annually into the Indies; he could grant "licences" to anyone who wanted them and he would be in charge of completing the required total if necessary.A Forgotten Chapter in the History of International Commercial Arbitration: The Slave Trade's Dispute Settlement System by ANNE-CHARLOTTE MARTINEAUDOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0922156518000158 Published online by Cambridge University Press: 08 March 2018 * 13 May 1601 – 16 October 1604: João Rodrigues Coutinho. * 16 October 1604 – 27 September 1615: Gonçalo Vaz Coutinho * 27 September 1615 – 1 April 1623:

António Fernandes de Elvas António Fernandes de Elvas (died 1623) was a Portuguese-born merchant, including investor in pepper tax farm and Asian spices. Fernandes de Elvas and his family were Marranos; that is to say Sephardic Jews who conformed outwardly as '' Cristão- ...

. The two main places in the Spanish Americas that slaves were brought were Cartagena de Indias

Cartagena ( , also ), known since the colonial era as Cartagena de Indias (), is a city and one of the major ports on the northern coast of Colombia in the Caribbean Coast Region, bordering the Caribbean sea. Cartagena's past role as a link ...

(in modern Colombia) and Veracruz

Veracruz (), formally Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave (), officially the Free and Sovereign State of Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave ( es, Estado Libre y Soberano de Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave), is one of the 31 states which, along with Me ...

(in modern Mexico

Mexico ( Spanish: México), officially the United Mexican States, is a country in the southern portion of North America. It is bordered to the north by the United States; to the south and west by the Pacific Ocean; to the southeast by Guate ...

) from here they were distributed out towards what is today Venezuela

Venezuela (; ), officially the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela ( es, link=no, República Bolivariana de Venezuela), is a country on the northern coast of South America, consisting of a continental landmass and many islands and islets in ...

, the Antilles

The Antilles (; gcf, label=Antillean Creole, Antiy; es, Antillas; french: Antilles; nl, Antillen; ht, Antiy; pap, Antias; Jamaican Patois: ''Antiliiz'') is an archipelago bordered by the Caribbean Sea to the south and west, the Gulf of Mex ...

and Lima

Lima ( ; ), originally founded as Ciudad de Los Reyes (City of The Kings) is the capital and the largest city of Peru. It is located in the valleys of the Chillón, Rímac and Lurín Rivers, in the desert zone of the central coastal part of t ...

(through Portobello and Panama

Panama ( , ; es, link=no, Panamá ), officially the Republic of Panama ( es, República de Panamá), is a transcontinental country spanning the southern part of North America and the northern part of South America. It is bordered by Co ...

) then to Upper Peru and Potosí

Potosí, known as Villa Imperial de Potosí in the colonial period, is the capital city and a municipality of the Department of Potosí in Bolivia. It is one of the highest cities in the world at a nominal . For centuries, it was the location o ...

.

**

* 1 April 1623 – 25 September 1631: Manuel Rodrigues Lamego Manuel Rodrigues de Lamego (born ''circa'' 1590) was a Portuguese-born merchant and slave trader active in Europe, Africa, Asia and the Americas. Rodrigues de Lamego was a Marrano. He was contracted by the Spanish Empire with an official '' asi ...

; 59 ships were licensed for Africa, where around 8,000 African slaves were purchased from West African merchants, mostly from Luanda

Luanda () is the Capital (political), capital and largest city in Angola. It is Angola's primary port, and its major Angola#Economy, industrial, Angola#Culture, cultural and Angola#Demographics, urban centre. Located on Angola's northern Atl ...

.

* 25 September 1631 – 1 December 1640: Melchor Gómez Angel and Cristóvão Mendes de Sousa.

In 1640 the

In 1640 the Iberian Union

pt, União Ibérica

, conventional_long_name =Iberian Union

, common_name =

, year_start = 1580

, date_start = 25 August

, life_span = 1580–1640

, event_start = War of the Portuguese Succession

, event_end = Portuguese Restoration War

, ...

fell apart; the Portuguese Restoration War

The Portuguese Restoration War ( pt, Guerra da Restauração) was the war between Portugal and Spain that began with the Portuguese revolution of 1640 and ended with the Treaty of Lisbon in 1668, bringing a formal end to the Iberian Union. The p ...

began. Between 1640 and 1651 there was no asiento. ) Slave arrivals to the Spanish Americas declined precipitously. On 12 July 1641 Portugal and the Dutch Republic signed a 'Treaty of Offensive and Defensive Alliance', otherwise known as the Treaty of The Hague. Dutch ships were allowed in any Portuguese port for ten years. Dutch merchant Jan Valckenburgh saw an opportunity but was expelled from Loango-Angola in 1648. Dutch private entrepreneurs were responsible for almost half of the total investment in slave trade against a smaller share held by the WIC.

The Invasion of Jamaica was the ''casus belli

A (; ) is an act or an event that either provokes or is used to justify a war. A ''casus belli'' involves direct offenses or threats against the nation declaring the war, whereas a ' involves offenses or threats against its ally—usually one ...

'' that resulted in the actual Anglo-Spanish War (1654-1660). In March 1659 the Danish Africa Company was started by the Finnish Hendrik Carloff

Hendrik Carloff (died after 1677) was an adventurer active in the 17th century. Carloff began his career as a cabin boy but rose to become the Commander and Director of the Dutch West India Company. He later joined the Swedish Africa Company and ...

and two Dutchmen. Their mandate included trade with the Danish Gold Coast. Their goal was to compete with the Dutch, the Swedish Africa Company

The Swedish Africa Company ( sv, Svenska Afrikanska Kompaniet) was a Swedish trading company, founded in 1649 on the initiative of the Walloon-Dutch merchant Louis De Geer and his son Laurens, for whom Sweden had become a second home. The primar ...

and the Portuguese. The Dutch competed with the Company of Royal Adventurers Trading to Africa founded in 1660. Both of these slaving powers had a strong presence on the Gold Coast and the Bight of Benin

The Bight of Benin or Bay of Benin is a bight in the Gulf of Guinea area on the western African coast that derives its name from the historical Kingdom of Benin.

Geography

It extends eastward for about from Cape St. Paul to the Nun outlet of ...

; many slaves came from Cross River (Nigeria)

Cross River (native name: Oyono) is the main river in southeastern Nigeria and gives its name to Cross River State. It originates in Cameroon, where it takes the name of the Manyu River. Although not long by African standards its catchment has h ...

, Calabar

Calabar (also referred to as Callabar, Calabari, Calbari and Kalabar) is the capital city of Cross River State, Nigeria. It was originally named Akwa Akpa, in the Efik language. The city is adjacent to the Calabar and Great Kwa rivers and ...

in the Bight of Biafra

The Bight of Biafra (known as the Bight of Bonny in Nigeria) is a bight off the West African coast, in the easternmost part of the Gulf of Guinea.

Geography

The Bight of Biafra, or Mafra (named after the town Mafra in southern Portugal), betwe ...

and West Central Africa

Central Africa is a subregion of the African continent comprising various countries according to different definitions. Angola, Burundi, the Central African Republic, Chad, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, the Republic of the Congo, E ...

. The Dutch and Portuguese signed a new Treaty of The Hague (1661). Matthias Beck, who had left Dutch Brazil in 1654, was appointed by the WIC as governor of Curaçao, that, from 1662 to 1728 and intermittently thereafter, functioned as an entrepôt

An ''entrepôt'' (; ) or transshipment port is a port, city, or trading post where merchandise may be imported, stored, or traded, usually to be exported again. Such cities often sprang up and such ports and trading posts often developed into c ...

through which captives on Dutch transatlantic ships reached Spanish colonies. A second branch of the intra-American slave traffic originated in Barbados

Barbados is an island country in the Lesser Antilles of the West Indies, in the Caribbean region of the Americas, and the most easterly of the Caribbean Islands. It occupies an area of and has a population of about 287,000 (2019 estimate ...

and the Colony of Jamaica.

Genoese: 1662–1671

In 1658 Ambrogio Lomellini and Domingo Grillo were appointed as ''Treasurers of the Holy Crusade'', waging war against "infidels". This fact allowed them to have access to a part of the treasures that came from America. (From the late 1640s Grillo and his business partner Lomellini lived in Madrid.Ammann, F. (2019) Looking through the mirrors: materiality and intimacy at Domenico Grillo's mansion in Baroque Madrid. https://doi.org/10.1080/13507486.2015.1131248) In 1662 and 1666 Spain (or the royal finances) were bankrupt. Slave-contracts of the WIC with Grillo and Lomellini of Madrid, 1662 and 1667, who were permitted to sub-contract to any nation friendly to Spain. * July 5, 1662 – 1669: Grillo and Lomellini promised to ship 24,000 slaves in seven years, assisted by the Dutch West India Company and the English Royal Adventurers from Jamaica toCartagena, Colombia

Cartagena ( , also ), known since the colonial era as Cartagena de Indias (), is a city and one of the major ports on the northern coast of Colombia in the Caribbean Coast Region, bordering the Caribbean sea. Cartagena's past role as a lin ...

, Veracruz in Mexico and Portobello in Panama. In 1664, the political situation in Europe and the Caribbean was volatile, leading to Second Anglo-Dutch War

The Second Anglo-Dutch War or the Second Dutch War (4 March 1665 – 31 July 1667; nl, Tweede Engelse Oorlog "Second English War") was a conflict between England and the Dutch Republic partly for control over the seas and trade routes, whe ...

. Robert Holmes captured the Dutch trading post of Cabo Verde in June 1664 and confiscated several ships of the Dutch West India company. The Duke of York, governor of the Royal Africa Company, envied the Dutch trade in slaves to Spanish America.

* Cristóbal Calderón, the attorney general or "procurador" of Havana, requests, on behalf of his city, a license to sail directly to the coasts of Guinea and Angola to supply themselves in slaves instead of relying on those the Asiento brought in from Barbados and Curaçao. Havana, April 28, 1664.

* In January 1667, Grillo and Lomelin convinced the Council of the Indies to return 100,000 pesos to the Asiento to restore the slaving negotiations with the British and the Dutch.DARING TRADE An Archaeology of the Slave Trade in Late-Seventeenth Century Panama (1663-1674) by Felipe Gaitán Ammann

* Grillo and Lomellini contacted :nl:Francesco Ferroni in Amsterdam and then turned to the Dutch to fulfil the conditions of their contract. Grillo's monopoly was bitterly received in the colonies. He operated almost exclusively by proxy. In 1668 when Grillo's estate was threatened with confiscation because of enormous debts, he succeeded in an extension of the Asiento for two years.

* In 1668 an immense warehouse was erected on baren island of Curaçao. About 90% of the slaves were exported from Curaçao and half of them illegally.

** In 1669 Spain is almost bankrupt. The Coymans bank in Amsterdam transported on four warships Spanish dollars or bars of silver (worth 500,000 guilders

Guilder is the English translation of the Dutch and German ''gulden'', originally shortened from Middle High German ''guldin pfenninc'' " gold penny". This was the term that became current in the southern and western parts of the Holy Roman Em ...

) from New Spain

New Spain, officially the Viceroyalty of New Spain ( es, Virreinato de Nueva España, ), or Kingdom of New Spain, was an integral territorial entity of the Spanish Empire, established by Habsburg Spain during the Spanish colonization of the Am ...

to Cadiz in order to get a subcontract. Also King Charles II of England tried to acquire the asiento.

** The Treaty of Madrid (1670) was highly favourable to England, as its ownership of territories in the Caribbean Sea was confirmed by Spain.Padron pp.xiv-xxi England agreed to suppress piracy in the Caribbean and in return Spain agreed to permit English ships freedom of movement

Freedom of movement, mobility rights, or the right to travel is a human rights concept encompassing the right of individuals to travel from place to place within the territory of a country,Jérémiee Gilbert, ''Nomadic Peoples and Human Rights' ...

. Both agreed to refrain from trading in the other's Caribbean territory and to limit trading to their possessions.

* In 1671 the Grillo asiento is ended because of mistrust. Grillo's experience opened up the way for expansion of the Dutch, English and French slave trading companies.

** In 1671, the privateer Henry Morgan

Sir Henry Morgan ( cy, Harri Morgan; – 25 August 1688) was a privateer, plantation owner, and, later, Lieutenant Governor of Jamaica. From his base in Port Royal, Jamaica, he raided settlements and shipping on the Spanish Main, becoming ...

, licensed by the English government, sacked and burned the city of Panamá Viejo

Panamá Viejo ( English: "Old Panama"), also known as Panamá la Vieja, is the remaining part of the original Panama City, the former capital of Panama, which was destroyed in 1671 by the Welsh privateer Henry Morgan. It is located in the suburb ...

an important port on the Pacific used by Grillo for slave trade along the coast.

** In 1672 the Royal Africa Company was founded, headed by the Duke of York

Duke of York is a title of nobility in the Peerage of the United Kingdom. Since the 15th century, it has, when granted, usually been given to the second son of List of English monarchs, English (later List of British monarchs, British) monarchs. ...

.

** In 1673 the Compagnie du Sénégal

The Compagnie du Sénégal (French for the "Senegal Company" or, more literally, the "Company of the Senegal") was a 17th-century French chartered company that administered the territories of Saint-Louis and Gorée island as part of French ...

was founded and used Gorée to house the slaves since 1677. According to historical accounts, no more than 500 slaves per year were traded there.

** 1674: The French West India Company went bankrupt; the Dutch lost New Amsterdam

New Amsterdam ( nl, Nieuw Amsterdam, or ) was a 17th-century Dutch settlement established at the southern tip of Manhattan Island that served as the seat of the colonial government in New Netherland. The initial trading ''factory'' gave rise ...

and New Netherlands

New Netherland ( nl, Nieuw Nederland; la, Novum Belgium or ) was a 17th-century colonial province of the Dutch Republic that was located on the east coast of what is now the United States. The claimed territories extended from the Delmarva P ...

in the Third Anglo-Dutch War

The Third Anglo-Dutch War ( nl, Derde Engels-Nederlandse Oorlog), 27 March 1672 to 19 February 1674, was a naval conflict between the Dutch Republic and England, in alliance with France. It is considered a subsidiary of the wider 1672 to 1678 ...

.

** 1675: The Dutch New West India Company restarted; Curaçao seems to have become a free port for sugar, slaves and contraband

Contraband (from Medieval French ''contrebande'' "smuggling") refers to any item that, relating to its nature, is illegal to be possessed or sold. It is used for goods that by their nature are considered too dangerous or offensive in the eyes o ...

.

Dutch & Portuguese: 1671–1701

In 1661 the Dutch and the Portuguese signed a

In 1661 the Dutch and the Portuguese signed a peace

Peace is a concept of societal friendship and harmony in the absence of hostility and violence. In a social sense, peace is commonly used to mean a lack of conflict (such as war) and freedom from fear of violence between individuals or groups. ...

, ratified the year after. In 1667 the Dutch and the English signed the Treaty of Breda and New York became British. The Treaty of Lisbon (1668) ended twenty-eight years of war between Spain and Portugal. In the same year, France ended its war with Spain after the War of Devolution.

* 1671-1674: António Garcia, a Portuguese, was the heir of Lomelino. In 1675 he looked for assistance from Balthasar and his brother Joseph Coymans

Joseph Coymans (1591 – ca 1653), was a Dutch businessman in Haarlem, known best today for his portrait painted by Frans Hals, and its pendant, ''Portrait of Dorothea Berck''. The former resides at the Wadsworth Atheneum in Hartford, the lat ...

and the Dutch West India Company

The Dutch West India Company ( nl, Geoctrooieerde Westindische Compagnie, ''WIC'' or ''GWC''; ; en, Chartered West India Company) was a chartered company of Dutch merchants as well as foreign investors. Among its founders was Willem Usselincx ( ...

, financing the loan and the shipping.Pertinent en waarachtig verhaal van alle de handelingen en directie van Pedro van Belle omtrent den slavenhandel, ofwel het Assiento de Negros ... Garcia arranged to purchase all the slaves in Curaçao.

* 1676–1679: Manuel Hierro de Castro, and Manuel José Cortizos, members of the Consulado de Sevilla. The Spanish proposed to get the slaves from Cape Verde

, national_anthem = ()

, official_languages = Portuguese

, national_languages = Cape Verdean Creole

, capital = Praia

, coordinates =

, largest_city = capital

, demonym ...

, located on the demarcation line between the Spanish and Portuguese empire, but this was against the WIC-charter. The Dutch offered to bring the slaves to Hispaniola

Hispaniola (, also ; es, La Española; Latin and french: Hispaniola; ht, Ispayola; tnq, Ayiti or Quisqueya) is an island in the Caribbean that is part of the Greater Antilles. Hispaniola is the most populous island in the West Indies, and t ...

or the ports on the Spanish Main

During the Spanish colonization of America, the Spanish Main was the collective term for the parts of the Spanish Empire that were on the mainland of the Americas and had coastlines on the Caribbean Sea or Gulf of Mexico. The term was used to di ...

. From 1662 to 1690, only twenty slaving vessels set out under the Spanish flag, mostly between 1677 and 1681, an average of less than one a year.Atlantic History and the Slave Trade to Spanish America ALEX BORUCKI, DAVID ELTIS, AND DAVID WHEAT. In: AMERICAN HISTORICAL REVIEW APRIL 2015, p. 450/ref> ** [] * In May 1679 the Coymans financed slave transports, organized by Captain Juan Barroso del Pozo, of 9,800 "negros" to Curaçao. * In 1680, Barroso from Seville and Nicolás Porcio, his Venetian son-in-law, became ''asentistas''. * 1682–1688: Juan Barroso del Pozo (–1683) and Nicolás Porcio succeeded in getting the asiento for 6.5 years. It was Porcio who encountered many financial difficulties after the loss of ships and slaves. In 1683 he travelled to Portobelo but was taken, prisoner. He was unable to make his payments to the crown, alleging that the local authorities in Cartagena were working against his interests.Wills, J.E. (2001) ''1688. A Global History'', p. 50. ** 1683 Dutch privateers attacked Veracruz and Cartagena. ** In 1684 Genoa was heavily bombarded by a French fleet as punishment for its alliance with Spain. As a result, the Genoese bankers and traders made new economic and financial links with Louis XIV. * February 1685 – March 1687:

Balthasar Coymans

Balthazar, or variant spellings, may refer to:

Arts, entertainment and media

* Balthazar (novel), ''Balthazar'' (novel), by Lawrence Durrell, 1958

* ''Balthasar'', an 1889 book by Anatole France

* ''Professor Balthazar'', a Croatian animated TV ...

succeeded in ousting Porcio. Barbour, V. (1963Capitalism in Amsterdam in the 17th century, p. 110-111

/ref> The cash payment to the Spanish government, an indispensable feature of this bargain, was furnished by the Amsterdam house of Coymans. Coymans made an immediate payment towards some frigates for the Spanish navy being built in Amsterdam and an advance on the dues he would be liable for on goods imported to Spanish America. ** Royal Order, signed "El Rey", commanding Don Balthasar Coymans, Don Juan Barrosa and Don Nicolás Porzio to assemble ten Capuchin monks ( Franciscan friars) from either Cadiz or Amsterdam to sail to the coast of Africa to buy slaves, to convert them to Christianity and sell them in the West Indies, 25 March 1685 Balthasar & Johan Coymans. ** ''Carta de Rodrigo Gómez a anuel Diego López de Zúñiga Mendoza Sotomayor, XDuque de Béjar informando de la concesión de un asiento de negros en el Río de la Plata a favor de Baltasar Coymans y pide recomendaciones personales para que su hijo Pedro sea empleado en ese negocio. Menciona también a Gaspar de Rebolledo, Juan Pimentel como Gobernador de Buenos Aires y a

arlos José Gutiérrez de los Ríos Roha, VI

Arlos is a commune in the Haute-Garonne department in southwestern France.

Population

See also

*Communes of the Haute-Garonne department

The following is a list of the 586 communes of the French department of Haute-Garonne.

The communes c ...

Conde de Fernán-Núñez''. Antwerp, 1685-04-17.

** July 1686: The Imperial Cortes, Council of Castile

The Council of Castile ( es, Real y Supremo Consejo de Castilla), known earlier as the Royal Council ( es, Consejo Real), was a ruling body and key part of the domestic government of the Crown of Castile, second only to the monarch himself. I ...

started an investigation into the legitimacy of the Asiento. The asiento with Coymans is annulled.

** October 1686: The Dutch refused to accept the "Junta de Asiento de Negros", a commission of dubious authority.

** There was a risk of war between France, Britain and Spain, resulting in the

Grand Alliance; the Dutch feared Jamaica

Jamaica (; ) is an island country situated in the Caribbean Sea. Spanning in area, it is the third-largest island of the Greater Antilles and the Caribbean (after Cuba and Hispaniola). Jamaica lies about south of Cuba, and west of Hispan ...

was becoming more important than Curaçao

Curaçao ( ; ; pap, Kòrsou, ), officially the Country of Curaçao ( nl, Land Curaçao; pap, Pais Kòrsou), is a Lesser Antilles island country in the southern Caribbean Sea and the Dutch Caribbean region, about north of the Venezuela coas ...

.

** The Dutch West India Company paid high dividends, 10%.

* 1687–1688: Jan Carçau, or Juan Carcán a former assistant of Balthasar Coymans, takes over the asiento.

** March 1688: Jan Carçao is put in prison in Cádiz, accused of fraud. In June 1688 the commission delivered an opinion the Dutch must recognize the Juntas authority before discussions could proceed.

** In August 1688 the shares of the Dutch East and West India company collapsed in a crash on the Amsterdam stock market. Since the Glorious Revolution the catholic oriented James II of England

James VII and II (14 October 1633 16 September 1701) was King of England and King of Ireland as James II, and King of Scotland as James VII from the death of his elder brother, Charles II, on 6 February 1685. He was deposed in the Glorious Re ...

exiled in France.

* 1688 – October 1691: Nicolás Porcio.

* 1692–1695: Bernardo Francisco Marín de Guzmán.

** 1695–1701: Spain returned to the Portuguese; Manuel Ferreira de Carvalho representing the Cacheu and Cape Verde Company

The Cacheu and Cape Verde Company (Portuguese: ''Companhia de Cacheu e Cabo Verde'') was a chartered company created by Portugal which operated the colonies of Cacheu and Cape Verde in the late 17th and early 18th centuries. It was created as p ...

.

** By 1695, the French Navy had declined to the point that it could no longer face the English and Dutch in an open sea battle and therefore had switched to privateering – Guerre de course.

** 1695-1696 The Royal Africa Company suffered heavy losses, and lost its monopoly after the Trade with Africa Act 1697.

** By 1696, it was clear Charles II of Spain would die childless, and his potential heirs included Louis XIV and Emperor Leopold in Vienna.

** May 1697 the French raided Cartagena and plundered the city. Jean du Casse, who gave his support only reluctantly, as he preferred an attack on Portobelo, where most of the silver and Spanish dollar

The Spanish dollar, also known as the piece of eight ( es, Real de a ocho, , , or ), is a silver coin of approximately diameter worth eight Spanish reales. It was minted in the Spanish Empire following a monetary reform in 1497 with content ...

s came from. All the countries needed to boost the economy at the end of the Nine Years War. In September 1697, France signed Treaties of Peace with Spain and England, and a Treaty of Peace and Commerce with the Dutch Republic ( Peace of Ryswick). In the Caribbean, France received the Spanish islands of Tortuga and Saint-Domingue

Saint-Domingue () was a French colony in the western portion of the Caribbean island of Hispaniola, in the area of modern-day Haiti, from 1659 to 1804. The name derives from the Spanish main city in the island, Santo Domingo, which came to ref ...

.

* 1699-1703 Manuel Belmonte cooperated with Luis and Simon Rodriques de Souza from the Portuguese West India Company.

** In 1700 a grandson of Louis XIV ascended the Spanish throne as King Philip V of Spain

Philip V ( es, Felipe; 19 December 1683 – 9 July 1746) was King of Spain from 1 November 1700 to 14 January 1724, and again from 6 September 1724 to his death in 1746. His total reign of 45 years is the longest in the history of the Spanish mon ...

.

** In 1702 the War of the Spanish Succession

The War of the Spanish Succession was a European great power conflict that took place from 1701 to 1714. The death of childless Charles II of Spain in November 1700 led to a struggle for control of the Spanish Empire between his heirs, Phili ...

began: the Grand Alliance (Kingdom of England

The Kingdom of England (, ) was a sovereign state on the island of Great Britain from 12 July 927, when it emerged from various Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, until 1 May 1707, when it united with Scotland to form the Kingdom of Great Britain.

On ...

, Dutch Republic

The United Provinces of the Netherlands, also known as the (Seven) United Provinces, officially as the Republic of the Seven United Netherlands ( Dutch: ''Republiek der Zeven Verenigde Nederlanden''), and commonly referred to in historiography ...

and Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a political entity in Western, Central, and Southern Europe that developed during the Early Middle Ages and continued until its dissolution in 1806 during the Napoleonic Wars.

From the accession of Otto I in 962 ...

) declared war on France and Spain. However, the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by Kingdom of England, English and Kingdom of Scotland, Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were foug ...

's main effort was not off the Spanish Main

During the Spanish colonization of America, the Spanish Main was the collective term for the parts of the Spanish Empire that were on the mainland of the Americas and had coastlines on the Caribbean Sea or Gulf of Mexico. The term was used to di ...

, but off the Spanish coasts in Europe ( Battle of Cádiz).Trevelyan: ''England Under Queen Anne: Blenheim,'' p. 259 Spanish naval losses in the Battle of Vigo Bay

The Battle of Vigo Bay, also known as the Battle of Rande (; ), was a naval engagement fought on 23 October 1702 during the opening years of the War of the Spanish Succession. The engagement followed an Anglo-Dutch attempt to capture the Spanish ...

meant a total dependence on the French navy to keep up communications with the Americas.Roger: ''The Command of the Ocean: A Naval History of Britain 1649–1815,'' p.166 Spain was reliant on French ships, not only for slaves, even for its bullion fleet. Because of commercial competition paying the French and Spanish for the Asiento was a prominent issue during the Spanish War of Succession.

** The Methuen Treaty with the Dutch envoy Francesco Belmonte as one of the negotiators regulated the establishment of trade relations between England, Portugal and perhaps Brazil? The Portuguese who had trouble letting go of their Asiento rights ... were understood as a French privilege and indeed a marker of the superior status of the French abroad.

French: 1701–1713

Jean-Baptiste du Casse

Jean-Baptiste du Casse (2 August 1646 – 25 June 1715) was a French privateer, admiral, and colonial administrator who served throughout the Atlantic World during the 17th and 18th centuries. Likely born 2 August 1646 in Saubusse, near Pau (B ...

in name of the Compagnie de Guinée et de l'Assiente des Royaume de la France, founded in 1684. Company of Guinée concentrated on the slave trade for Guinée and Saint-Domingue; returning with sugar and all the other goods to Nantes

Nantes (, , ; Gallo: or ; ) is a city in Loire-Atlantique on the Loire, from the Atlantic coast. The city is the sixth largest in France, with a population of 314,138 in Nantes proper and a metropolitan area of nearly 1 million inhabit ...

. In 1701, the French King granted the Guinée Company the Spanish Asiento and the company reorganised. Unlike any other chartered company before it, it included both the Spanish King and the French King as shareholders, for one-quarter of the total capital each, which amounted to 100,000 livres. The Asiento did not concern French Caribbean but Spanish America.

* In 1706, the English planters on Jamaica

Jamaica (; ) is an island country situated in the Caribbean Sea. Spanning in area, it is the third-largest island of the Greater Antilles and the Caribbean (after Cuba and Hispaniola). Jamaica lies about south of Cuba, and west of Hispan ...

asked the Guinée company to supply them with slaves, but it was refused.

* December 2, 1711, Jacques Cassard

Jacques Cassard (30 September 1679 – 1740) was a French naval officer and privateer.

Biography

Born on 30 September 1679 to a family of merchants of Nantes, Cassard began a career as a sailor at age 14 on the merchantmen owned by his fa ...

obtained from the French king the command of a squadron of eight vessels and embarked on an expedition during which he plundered the Portuguese colony Cape Verde

, national_anthem = ()

, official_languages = Portuguese

, national_languages = Cape Verdean Creole

, capital = Praia

, coordinates =

, largest_city = capital

, demonym ...

. He seized in particular fort Praia

Praia (, Portuguese for "beach") is the capital and largest city of Cape Verde.Santiago, Cape Verde

Santiago ( Portuguese for “Saint James”) is the largest island of Cape Verde, its most important agricultural centre and home to half the nation's population. Part of the Sotavento Islands, it lies between the islands of Maio ( to the east) ...

, the storehouse of the commerce. Then he set off to Montserrat and Antigua

Antigua ( ), also known as Waladli or Wadadli by the native population, is an island in the Lesser Antilles. It is one of the Leeward Islands in the Caribbean region and the main island of the country of Antigua and Barbuda. Antigua and Ba ...

in the Caribbean before heading to the possessions of the Dutch. On 10 October 1712, Cassard attacked Suriname

Suriname (; srn, Sranankondre or ), officially the Republic of Suriname ( nl, Republiek Suriname , srn, Ripolik fu Sranan), is a country on the northeastern Atlantic coast of South America. It is bordered by the Atlantic Ocean to the north ...

and Berbice

Berbice is a region along the Berbice River in Guyana, which was between 1627 and 1792 a colony of the Dutch West India Company and between 1792 to 1815 a colony of the Dutch state. After having been ceded to the United Kingdom of Great Britain ...

, where demanded an amount of 300,000 guilders, which was paid in bills of exchange, slaves and goods. The negotiations with Suriname started, and on 27 October Cassard left with ƒ 747,350 (€8.1 million in 2018). Cassard returned to Martinique

Martinique ( , ; gcf, label=Martinican Creole, Matinik or ; Kalinago language, Kalinago: or ) is an island and an Overseas department and region, overseas department/region and single territorial collectivity of France. An integral part of ...

and set sail towards Sint Eustatius

Sint Eustatius (, ), also known locally as Statia (), is an island in the Caribbean. It is a special municipality (officially " public body") of the Netherlands.

The island lies in the northern Leeward Islands portion of the West Indies, s ...

. Curaçao

Curaçao ( ; ; pap, Kòrsou, ), officially the Country of Curaçao ( nl, Land Curaçao; pap, Pais Kòrsou), is a Lesser Antilles island country in the southern Caribbean Sea and the Dutch Caribbean region, about north of the Venezuela coas ...

was occupied by Cassard from February 18 to 27, 1713, more substantial and richer than the previous ones, but it's also much better defended.

* The King abolished the Asiento Company's monopoly in 1713 and opened the trade south of the Sierra Leone River to French private traders from five specific port towns: Nantes, Bordeaux, La Rochelle, Le Havre and Saint-Malo. They paid a tax to the king for each enslaved African transported to the French West Indies upon their return to France.

British: 1713–1750

After the introduction of the Trade with Africa Act 1697 the Royal African Company lost its monopoly and in 1708 it wasinsolvent

In accounting, insolvency is the state of being unable to pay the debts, by a person or company (debtor), at maturity; those in a state of insolvency are said to be ''insolvent''. There are two forms: cash-flow insolvency and balance-sheet i ...

.

*1 May 1713–May 1743: South Sea Company

The South Sea Company (officially The Governor and Company of the merchants of Great Britain, trading to the South Seas and other parts of America, and for the encouragement of the Fishery) was a British joint-stock company founded in Ja ...

received the Asiento for thirty years,Accounting and international relations: Britain, Spain and the Asiento treaty Salvador Carmona, Rafael Donoso, Stephen P. Walker, p. 257-258/ref> The English contractor was required to advance 200,000 pesos (£45,000) to Philip for their share in the trade, to be paid in two equal installments, the first two months after the contract was signed, the second two months after the first. In addition, the company was allowed to send one ship of 500 tons annually to Portobello to engage in normal trade to avoid

contraband

Contraband (from Medieval French ''contrebande'' "smuggling") refers to any item that, relating to its nature, is illegal to be possessed or sold. It is used for goods that by their nature are considered too dangerous or offensive in the eyes o ...

.

The 1713 Peace of Utrecht

The Peace of Utrecht was a series of peace treaties signed by the belligerents in the War of the Spanish Succession, in the Dutch city of Utrecht between April 1713 and February 1715. The war involved three contenders for the vacant throne of ...

granted Britain an ''asiento de negros'' lasting 30 years to supply the Spanish colonies with 144,000 at 4,800 slaves per year. Britain was permitted to open offices in Buenos Aires

Buenos Aires ( or ; ), officially the Autonomous City of Buenos Aires ( es, link=no, Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires), is the Capital city, capital and primate city of Argentina. The city is located on the western shore of the Río de la Plata ...

, Caracas

Caracas (, ), officially Santiago de León de Caracas, abbreviated as CCS, is the capital and largest city of Venezuela, and the center of the Metropolitan Region of Caracas (or Greater Caracas). Caracas is located along the Guaire River in the ...

, Cartagena, Havana

Havana (; Spanish: ''La Habana'' ) is the capital and largest city of Cuba. The heart of the La Habana Province, Havana is the country's main port and commercial center.

, Panama

Panama ( , ; es, link=no, Panamá ), officially the Republic of Panama ( es, República de Panamá), is a transcontinental country spanning the southern part of North America and the northern part of South America. It is bordered by Co ...

, Portobello and Vera Cruz Veracruz is a state in Mexico. Veracruz or Vera Cruz (literally "True Cross") may also refer to:

People

* María González Veracruz (born 1979), Spanish politician

* Philip Vera Cruz (1904–1994), Filipino American labor leader

* Tomé Vera Cruz ...

. An extra-legal clause was added; one ship of no more than 500 tons could be sent to one of these places each year (the ''Navío de Permiso'') with general trade goods. (Two ships were in addition to the annual ships, but were not part of the asiento contract.) One-quarter of the profits were to be reserved for the King of Spain. The Asiento was granted in the name of Queen Anne and then contracted to the company.

It was provided that the same reporting procedure might take place at subsequent five-year intervals. At the end of the contract the Assentistas were permitted three years to remove their effects from the Indies, adjust their accounts and ‘‘make up a balance of the whole”.

By July the South Sea Company had arranged contracts with the Royal African Company

The Royal African Company (RAC) was an English mercantile (trading) company set up in 1660 by the royal Stuart family and City of London merchants to trade along the west coast of Africa. It was led by the Duke of York, who was the brother of ...

to supply the necessary African slaves to Jamaica. Ten pounds was paid for a slave aged over 16, £8 for one under 16 but over 10. Two-thirds were to be male, and 90% adult. The company trans-shipped 1,230 slaves from Jamaica to America in the first year, plus any that might have been added (against standing instructions) by the ship's captains on their own behalf. On arrival of the first cargoes, the local authorities refused to accept the ''asiento'', which had still not been officially confirmed there by the Spanish authorities. The slaves were eventually sold at a loss in the West Indies.

In 1714 the government announced that a quarter of profits would be reserved for Queen Anne and a further 7.5% for a financial advisor, Manuel Manasses Gilligan, an English colonist, who operated from the (neutral) Danish West Indies

The Danish West Indies ( da, Dansk Vestindien) or Danish Antilles or Danish Virgin Islands were a Danish colony in the Caribbean, consisting of the islands of Saint Thomas with ; Saint John ( da, St. Jan) with ; and Saint Croix with . The ...

. Some Company board members refused to accept the contract on these terms, and the government was obliged to reverse its decision. Despite these setbacks, the company continued, having raised 200,000 peso

The peso is the monetary unit of several countries in the Americas, and the Philippines. Originating in the Spanish Empire, the word translates to "weight". In most countries the peso uses the same sign, "$", as many currencies named "dollar" ...

s (maybe ducats or Spanish escudos? to finance the operations. Anne had secretly negotiated with France to get its approval regarding the ''asiento.'' She boasted to Parliament of her success in taking the ''asiento'' away from France and London celebrated her economic coup.

In 1714 2,680 slaves were carried, and for 1716–17, 13,000 more, but the trade continued to be unprofitable. As the French previously discovered, high costs meant the real profits from the slave trade asiento were in smuggling contraband goods, which evaded import duties and deprived the authorities of much-needed revenue. An import duty of 33 pieces of eight was charged on each slave (although for this purpose two children were counted as one adult slave). In 1718 a declaration of war between England and Spain halted operations under the Asiento until 1721. The company's assets in South America were seized, at a cost claimed by the company to be £300,000. Any prospect of profit from trade, for which the company had purchased ships and had been planning its next ventures, disappeared. Similar conflicts interrupted the contract from 1727 to 1729 and 1739 to 1748. Increasing knowledge of illicit trading by the SSC resulted in the Spanish tightening on-site monitoring in the Americas during the 1730s. The Spanish then proceeded to seek recompense for clandestine trade carried on by the SSC and others under the veil of the supply of Negroes and the annual ship. Thus a key feature of the depredations crisis was the ongoing failure by the SSC to account and report transparently. Spain having raised objections to the ''asiento'' clauses, the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle was supplemented by the Treaty of Madrid (5 October 1750). The matter of the ''asiento'' was not even mentioned in the treaty, as it had lessened in importance to both nations, although both parties had agreed to resolve outstanding concerns at a "proper time and place". The issue was finally settled in 1750 when Britain agreed to renounce its claim to the asiento in exchange for a payment of £100,000 and British trade with