Archaeologists From Paris on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Archaeology or archeology is the scientific study of human activity through the recovery and

Archaeology or archeology is the scientific study of human activity through the recovery and

The science of archaeology (from

The science of archaeology (from

One of the first sites to undergo archaeological excavation was

One of the first sites to undergo archaeological excavation was

The father of archaeological excavation was William Cunnington (1754–1810). He undertook excavations in

The father of archaeological excavation was William Cunnington (1754–1810). He undertook excavations in

The first stratigraphic excavation to reach wide popularity with public was that of

The first stratigraphic excavation to reach wide popularity with public was that of

The purpose of archaeology is to learn more about past societies and the development of the human race. Over 99% of the development of humanity has occurred within prehistoric cultures, who did not make use of

The purpose of archaeology is to learn more about past societies and the development of the human race. Over 99% of the development of humanity has occurred within prehistoric cultures, who did not make use of

The archaeological project then continues (or alternatively, begins) with a

The archaeological project then continues (or alternatively, begins) with a  The simplest survey technique is surface survey. It involves combing an area, usually on foot but sometimes with the use of mechanized transport, to search for features or artifacts visible on the surface. Surface survey cannot detect sites or features that are completely buried under earth, or overgrown with vegetation. Surface survey may also include mini-excavation techniques such as augers, corers, and

The simplest survey technique is surface survey. It involves combing an area, usually on foot but sometimes with the use of mechanized transport, to search for features or artifacts visible on the surface. Surface survey cannot detect sites or features that are completely buried under earth, or overgrown with vegetation. Surface survey may also include mini-excavation techniques such as augers, corers, and

Archaeological excavation existed even when the field was still the domain of amateurs, and it remains the source of the majority of data recovered in most field projects. It can reveal several types of information usually not accessible to survey, such as

Archaeological excavation existed even when the field was still the domain of amateurs, and it remains the source of the majority of data recovered in most field projects. It can reveal several types of information usually not accessible to survey, such as

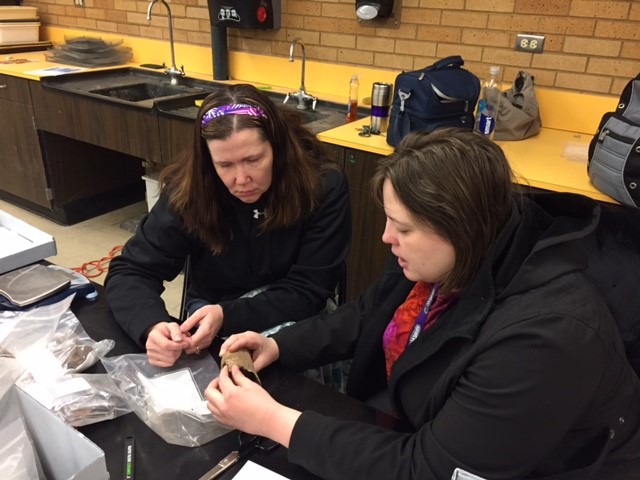

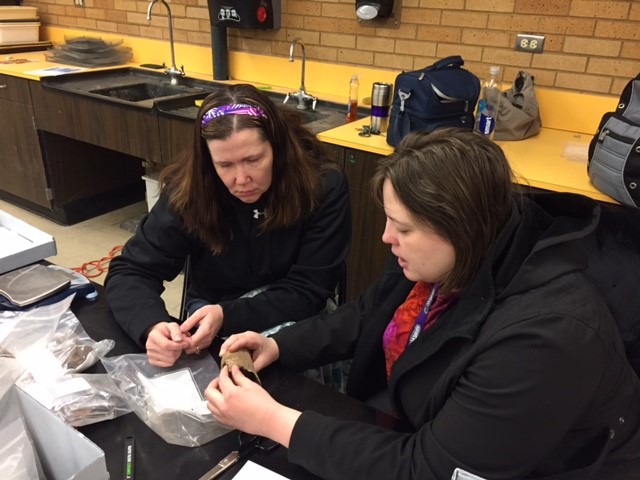

Once artifacts and structures have been excavated, or collected from surface surveys, it is necessary to properly study them. This process is known as post-excavation analysis, and is usually the most time-consuming part of an archaeological investigation. It is not uncommon for final excavation reports for major sites to take years to be published.

At a basic level of analysis, artifacts found are cleaned, catalogued and compared to published collections. This comparison process often involves classifying them typologically and identifying other sites with similar artifact assemblages. However, a much more comprehensive range of analytical techniques are available through archaeological science, meaning that artifacts can be dated and their compositions examined. Bones, plants, and pollen collected from a site can all be analyzed using the methods of

Once artifacts and structures have been excavated, or collected from surface surveys, it is necessary to properly study them. This process is known as post-excavation analysis, and is usually the most time-consuming part of an archaeological investigation. It is not uncommon for final excavation reports for major sites to take years to be published.

At a basic level of analysis, artifacts found are cleaned, catalogued and compared to published collections. This comparison process often involves classifying them typologically and identifying other sites with similar artifact assemblages. However, a much more comprehensive range of analytical techniques are available through archaeological science, meaning that artifacts can be dated and their compositions examined. Bones, plants, and pollen collected from a site can all be analyzed using the methods of

The protection of archaeological finds for the public from catastrophes, wars and armed conflicts is increasingly being implemented internationally. This happens on the one hand through international agreements and on the other hand through organizations that monitor or enforce protection.

The protection of archaeological finds for the public from catastrophes, wars and armed conflicts is increasingly being implemented internationally. This happens on the one hand through international agreements and on the other hand through organizations that monitor or enforce protection.

Early archaeology was largely an attempt to uncover spectacular artifacts and features, or to explore vast and mysterious abandoned cities and was mostly done by upper class, scholarly men. This general tendency laid the foundation for the modern popular view of archaeology and archaeologists. Many of the public view archaeology as something only available to a narrow demographic. The job of archaeologist is depicted as a "romantic adventurist occupation". and as a hobby more than a job in the scientific community. Cinema audiences form a notion of "who archaeologists are, why they do what they do, and how relationships to the past are constituted", and is often under the impression that all archaeology takes place in a distant and foreign land, only to collect monetarily or spiritually priceless artifacts. The modern depiction of archaeology has incorrectly formed the public's perception of what archaeology is.

Much thorough and productive research has indeed been conducted in dramatic locales such as

Early archaeology was largely an attempt to uncover spectacular artifacts and features, or to explore vast and mysterious abandoned cities and was mostly done by upper class, scholarly men. This general tendency laid the foundation for the modern popular view of archaeology and archaeologists. Many of the public view archaeology as something only available to a narrow demographic. The job of archaeologist is depicted as a "romantic adventurist occupation". and as a hobby more than a job in the scientific community. Cinema audiences form a notion of "who archaeologists are, why they do what they do, and how relationships to the past are constituted", and is often under the impression that all archaeology takes place in a distant and foreign land, only to collect monetarily or spiritually priceless artifacts. The modern depiction of archaeology has incorrectly formed the public's perception of what archaeology is.

Much thorough and productive research has indeed been conducted in dramatic locales such as

Motivated by a desire to halt looting, curb

Motivated by a desire to halt looting, curb

The Archaeology Channel

to support the organization's mission "to nurturing and bringing attention to the human cultural heritage, by using media in the most efficient and effective ways possible." There is a considerable international body of research focused on archaeology and public value and tangible benefits of archaeology include helping to counteract racism, documenting accomplishments of ignored communities, providing time-depth as a response to short-termism of the modern age, contribution to human ecology, independent evidence base, historic context development and tourism The delivery of public benefits through archaeology can be summarised as follows: through making a contribution to a shared history, artistic and cultural treasures, local values, place-making and social cohesion, educational benefits, contribution to science and innovation, health and wellbeing, and added economic value to developers.

400,000 records of archaeological sites and architecture in England

Archaeolog.org

Archaeology Daily News

Archaeology Times , The top archaeology news from around the world

Council for British Archaeology

Estudio de Museología Rosario

Fasti Online – an online database of archaeological sites

Great Archaeology

* ttp://www.archaeology.gov.lk/ Sri Lanka Archaeology

Scottish Archaeological Research Framework (ScARF)

The Archaeological Institute of America

The Archaeology Channel

The Archaeology Data Service – Open access online archive for UK and global archaeology

The Archaeology Division of the American Anthropological Association

The Canadian Museum of Civilization – Archaeology

The Society for American Archaeology

The World Archaeological Congress

US Forest Service Volunteer program ''Passport in Time''

* ttp://usaklihoyuk.org/en The Italian Archaeological Mission in Uşaklı Höyük

Comprehensive Database of Archaeological Site Reports in Japan

{{Authority control Anthropology

Archaeology or archeology is the scientific study of human activity through the recovery and

Archaeology or archeology is the scientific study of human activity through the recovery and analysis

Analysis ( : analyses) is the process of breaking a complex topic or substance into smaller parts in order to gain a better understanding of it. The technique has been applied in the study of mathematics and logic since before Aristotle (3 ...

of material culture

Material culture is the aspect of social reality grounded in the objects and architecture that surround people. It includes the usage, consumption, creation, and trade of objects as well as the behaviors, norms, and rituals that the objects crea ...

. The archaeological record

The archaeological record is the body of physical (not written) evidence about the past. It is one of the core concepts in archaeology, the academic discipline concerned with documenting and interpreting the archaeological record. Archaeological t ...

consists of artifacts, architecture

Architecture is the art and technique of designing and building, as distinguished from the skills associated with construction. It is both the process and the product of sketching, conceiving, planning, designing, and constructing buildings ...

, biofacts or ecofacts, sites, and cultural landscape

Cultural landscape is a term used in the fields of geography, ecology, and heritage studies, to describe a symbiosis of human activity and environment. As defined by the World Heritage Committee, it is the "cultural properties hatrepresent the ...

s. Archaeology can be considered both a social science

Social science is one of the branches of science, devoted to the study of societies and the relationships among individuals within those societies. The term was formerly used to refer to the field of sociology, the original "science of s ...

and a branch of the humanities

Humanities are academic disciplines that study aspects of human society and culture. In the Renaissance, the term contrasted with divinity and referred to what is now called classics, the main area of secular study in universities at t ...

. It is usually considered an independent academic discipline

An academy (Attic Greek: Ἀκαδήμεια; Koine Greek Ἀκαδημία) is an institution of secondary education, secondary or tertiary education, tertiary higher education, higher learning (and generally also research or honorary membershi ...

, but may also be classified as part of anthropology

Anthropology is the scientific study of humanity, concerned with human behavior, human biology, cultures, societies, and linguistics, in both the present and past, including past human species. Social anthropology studies patterns of be ...

(in North America – the four-field approach), history

History (derived ) is the systematic study and the documentation of the human activity. The time period of event before the invention of writing systems is considered prehistory. "History" is an umbrella term comprising past events as well ...

or geography

Geography (from Greek: , ''geographia''. Combination of Greek words ‘Geo’ (The Earth) and ‘Graphien’ (to describe), literally "earth description") is a field of science devoted to the study of the lands, features, inhabitants, an ...

.

Archaeologists study human prehistory

Prehistory, also known as pre-literary history, is the period of human history between the use of the first stone tools by hominins 3.3 million years ago and the beginning of recorded history with the invention of writing systems. The us ...

and history

History (derived ) is the systematic study and the documentation of the human activity. The time period of event before the invention of writing systems is considered prehistory. "History" is an umbrella term comprising past events as well ...

, from the development of the first stone tool

A stone tool is, in the most general sense, any tool made either partially or entirely out of stone. Although stone tool-dependent societies and cultures still exist today, most stone tools are associated with prehistoric (particularly Stone A ...

s at Lomekwi

Lomekwi 3 is the name of an archaeological site in Kenya where ancient stone tools have been discovered dating to 3.3 million years ago, which make them the oldest ever found.

Discovery

In July 2011, a team of archeologists led by Sonia Harm ...

in East Africa 3.3 million years ago up until recent decades. Archaeology is distinct from palaeontology

Paleontology (), also spelled palaeontology or palæontology, is the scientific study of life that existed prior to, and sometimes including, the start of the Holocene epoch (roughly 11,700 years before present). It includes the study of fossi ...

, which is the study of fossil

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserved ...

remains. Archaeology is particularly important for learning about prehistoric societies, for which, by definition, there are no written records. Prehistory includes over 99% of the human past, from the Paleolithic

The Paleolithic or Palaeolithic (), also called the Old Stone Age (from Greek: παλαιός '' palaios'', "old" and λίθος ''lithos'', "stone"), is a period in human prehistory that is distinguished by the original development of stone too ...

until the advent of literacy in societies around the world. Archaeology has various goals, which range from understanding culture history

Culture-historical archaeology is an archaeological theory that emphasises defining historical societies into distinct ethnic and cultural groupings according to their material culture.

It originated in the late nineteenth century as cultural ev ...

to reconstructing past lifeway

Lifeway is a term used in the disciplines of anthropology, sociology and archeology, particularly in North America.

History Literature

From the mid 19th century, the word was used with the meaning 'way through life' or 'way of life'. It a ...

s to documenting and explaining changes in human societies through time. Derived from the Greek, the term ''archaeology'' literally means "the study of ancient history".

The discipline involves surveying

Surveying or land surveying is the technique, profession, art, and science of determining the terrestrial two-dimensional or three-dimensional positions of points and the distances and angles between them. A land surveying professional is ...

, excavation

Excavation may refer to:

* Excavation (archaeology)

* Excavation (medicine)

* ''Excavation'' (The Haxan Cloak album), 2013

* ''Excavation'' (Ben Monder album), 2000

* ''Excavation'' (novel), a 2000 novel by James Rollins

* '' Excavation: A Mem ...

, and eventually analysis

Analysis ( : analyses) is the process of breaking a complex topic or substance into smaller parts in order to gain a better understanding of it. The technique has been applied in the study of mathematics and logic since before Aristotle (3 ...

of data collected, to learn more about the past. In broad scope, archaeology relies on cross-disciplinary research.

Archaeology developed out of antiquarianism

An antiquarian or antiquary () is an fan (person), aficionado or student of antiquities or things of the past. More specifically, the term is used for those who study history with particular attention to ancient artifact (archaeology), artifac ...

in Europe during the 19th century, and has since become a discipline practiced around the world. Archaeology has been used by nation-states to create particular visions of the past. Since its early development, various specific sub-disciplines of archaeology have developed, including maritime archaeology

Maritime archaeology (also known as marine archaeology) is a discipline within archaeology as a whole that specifically studies human interaction with the sea, lakes and rivers through the study of associated physical remains, be they vessels, s ...

, feminist archaeology

Feminist archaeology employs a feminist perspective in interpreting past societies. It often focuses on gender, but also considers gender in tandem with other factors, such as sexuality, race, or class. Feminist archaeology has critiqued the ...

, and archaeoastronomy

Archaeoastronomy (also spelled archeoastronomy) is the interdisciplinary or multidisciplinary study of how people in the past "have understood the phenomena in the sky, how they used these phenomena and what role the sky played in their cu ...

, and numerous different scientific techniques have been developed to aid archaeological investigation. Nonetheless, today, archaeologists face many problems, such as dealing with pseudoarchaeology

Pseudoarchaeology—also known as alternative archaeology, fringe archaeology, fantastic archaeology, cult archaeology, and spooky archaeology—is the interpretation of the past from outside the archaeological science community, which rejects ...

, the looting

Looting is the act of stealing, or the taking of goods by force, typically in the midst of a military, political, or other social crisis, such as war, natural disasters (where law and civil enforcement are temporarily ineffective), or rioting. ...

of artifacts, a lack of public interest, and opposition to the excavation of human remains.

History

First instances of archaeology

InAncient Mesopotamia

The history of Mesopotamia ranges from the earliest human occupation in the Paleolithic period up to Late antiquity. This history is pieced together from evidence retrieved from archaeological excavations and, after the introduction of writing i ...

, a foundation deposit of the Akkadian Empire

The Akkadian Empire () was the first ancient empire of Mesopotamia after the long-lived civilization of Sumer. It was centered in the city of Akkad () and its surrounding region. The empire united Akkadian and Sumerian speakers under one r ...

ruler Naram-Sin (ruled ) was discovered and analysed by king Nabonidus

Nabonidus (Babylonian cuneiform: ''Nabû-naʾid'', meaning "May Nabu be exalted" or "Nabu is praised") was the last king of the Neo-Babylonian Empire, ruling from 556 BC to the fall of Babylon to the Achaemenid Empire under Cyrus the Great in ...

, , who is thus known as the first archaeologist. Not only did he lead the first excavations which were to find the foundation deposits of the temples of Šamaš the sun god, the warrior goddess Anunitu (both located in Sippar

Sippar ( Sumerian: , Zimbir) was an ancient Near Eastern Sumerian and later Babylonian city on the east bank of the Euphrates river. Its '' tell'' is located at the site of modern Tell Abu Habbah near Yusufiyah in Iraq's Baghdad Governorate, som ...

), and the sanctuary that Naram-Sin built to the moon god, located in Harran

Harran (), historically known as Carrhae ( el, Kάρραι, Kárrhai), is a rural town and district of the Şanlıurfa Province in southeastern Turkey, approximately 40 kilometres (25 miles) southeast of Urfa and 20 kilometers from the border ...

, but he also had them restored to their former glory. He was also the first to date an archaeological artifact in his attempt to date Naram-Sin's temple during his search for it. Even though his estimate was inaccurate by about 1,500 years, it was still a very good one considering the lack of accurate dating technology at the time.

Antiquarians

The science of archaeology (from

The science of archaeology (from Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

, ''archaiologia'' from , ''arkhaios'', "ancient" and , ''-logia'', "-logy

''-logy'' is a suffix in the English language, used with words originally adapted from Ancient Greek ending in ('). The earliest English examples were anglicizations of the French '' -logie'', which was in turn inherited from the Latin ''-lo ...

") grew out of the older multi-disciplinary study known as antiquarian

An antiquarian or antiquary () is an fan (person), aficionado or student of antiquities or things of the past. More specifically, the term is used for those who study history with particular attention to ancient artifact (archaeology), artifac ...

ism. Antiquarians studied history

History (derived ) is the systematic study and the documentation of the human activity. The time period of event before the invention of writing systems is considered prehistory. "History" is an umbrella term comprising past events as well ...

with particular attention to ancient artifacts and manuscripts, as well as historical sites. Antiquarianism focused on the empirical evidence that existed for the understanding of the past, encapsulated in the motto of the 18th century antiquary, Sir Richard Colt Hoare: "We speak from facts not theory". Tentative steps towards the systematization of archaeology as a science

Science is a systematic endeavor that builds and organizes knowledge in the form of testable explanations and predictions about the universe.

Science may be as old as the human species, and some of the earliest archeological evidence ...

took place during the Enlightenment period

The Age of Enlightenment or the Enlightenment; german: Aufklärung, "Enlightenment"; it, L'Illuminismo, "Enlightenment"; pl, Oświecenie, "Enlightenment"; pt, Iluminismo, "Enlightenment"; es, La Ilustración, "Enlightenment" was an intel ...

in Europe in the 17th and 18th centuries.

In Imperial China

The earliest known written records of the history of China date from as early as 1250 BC, from the Shang dynasty (c. 1600–1046 BC), during the reign of king Wu Ding. Ancient historical texts such as the '' Book of Documents'' (early chapt ...

during the Song dynasty

The Song dynasty (; ; 960–1279) was an imperial dynasty of China that began in 960 and lasted until 1279. The dynasty was founded by Emperor Taizu of Song following his usurpation of the throne of the Later Zhou. The Song conquered the res ...

(960–1279), figures such as Ouyang Xiu

Ouyang Xiu (; 1007 – 1072 CE), courtesy name Yongshu, also known by his art names Zuiweng () and Liu Yi Jushi (), was a Chinese historian, calligrapher, epigrapher, essayist, poet, and politician of the Song dynasty. He was a renowned writ ...

and Zhao Mingcheng established the tradition of Chinese epigraphy

Epigraphy () is the study of inscriptions, or epigraphs, as writing; it is the science of identifying graphemes, clarifying their meanings, classifying their uses according to dates and cultural contexts, and drawing conclusions about the w ...

by investigating, preserving, and analyzing ancient Chinese bronze inscriptions

Chinese bronze inscriptions, also commonly referred to as bronze script or bronzeware script, are writing in a variety of Chinese scripts on ritual bronzes such as ''zhōng'' bells and '' dǐng'' tripodal cauldrons from the Shang dynasty (2nd m ...

from the Shang

The Shang dynasty (), also known as the Yin dynasty (), was a Chinese royal dynasty founded by Tang of Shang (Cheng Tang) that ruled in the Yellow River valley in the second millennium BC, traditionally succeeding the Xia dynasty and ...

and Zhou periods. In his book

His or HIS may refer to:

Computing

* Hightech Information System, a Hong Kong graphics card company

* Honeywell Information Systems

* Hybrid intelligent system

* Microsoft Host Integration Server

Education

* Hangzhou International School, in ...

published in 1088, Shen Kuo

Shen Kuo (; 1031–1095) or Shen Gua, courtesy name Cunzhong (存中) and pseudonym Mengqi (now usually given as Mengxi) Weng (夢溪翁),Yao (2003), 544. was a Chinese polymathic scientist and statesman of the Song dynasty (960–1279). Shen wa ...

criticized contemporary Chinese scholars for attributing ancient bronze vessels as creations of famous sages rather than artisan commoners, and for attempting to revive them for ritual use without discerning their original functionality and purpose of manufacture. Such antiquarian pursuits waned after the Song period, were revived in the 17th century during the Qing dynasty

The Qing dynasty ( ), officially the Great Qing,, was a Manchu-led imperial dynasty of China and the last orthodox dynasty in Chinese history. It emerged from the Later Jin dynasty founded by the Jianzhou Jurchens, a Tungusic-speak ...

, but were always considered a branch of Chinese historiography

Chinese historiography is the study of the techniques and sources used by historians to develop the recorded history of China.

Overview of Chinese history

The recording of events in Chinese history dates back to the Shang dynasty (c. 1600–1046 ...

rather than a separate discipline of archaeology.

In Renaissance Europe

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass ideas ...

, philosophical interest in the remains of Greco-Roman

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

* Rome, the capital city of Italy

* Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*''Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a lett ...

civilization and the rediscovery of classical culture began in the late Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire ...

, with humanism

Humanism is a philosophical stance that emphasizes the individual and social potential and agency of human beings. It considers human beings the starting point for serious moral and philosophical inquiry.

The meaning of the term "human ...

.

Cyriacus of Ancona

Cyriacus of Ancona or Ciriaco de' Pizzicolli (31 July 1391 – 1453/55) was a restlessly itinerant Italian humanist and antiquarian who came from a prominent family of merchants in Ancona, a maritime republic on the Adriatic. He has been called ...

was a restlessly itinerant Italian humanist

Humanism is a philosophical stance that emphasizes the individual and social potential and agency of human beings. It considers human beings the starting point for serious moral and philosophical inquiry.

The meaning of the term "human ...

and antiquarian

An antiquarian or antiquary () is an fan (person), aficionado or student of antiquities or things of the past. More specifically, the term is used for those who study history with particular attention to ancient artifact (archaeology), artifac ...

who came from a prominent family of merchants in Ancona

Ancona (, also , ) is a city and a seaport in the Marche region in central Italy, with a population of around 101,997 . Ancona is the capital of the province of Ancona and of the region. The city is located northeast of Rome, on the Adriatic ...

, a maritime republic

The maritime republics ( it, repubbliche marinare), also called merchant republics ( it, repubbliche mercantili), were thalassocratic city-states of the Mediterranean Basin during the Middle Ages. Being a significant presence in Italy in the Mid ...

on the Adriatic

The Adriatic Sea () is a body of water separating the Italian Peninsula from the Balkan Peninsula. The Adriatic is the northernmost arm of the Mediterranean Sea, extending from the Strait of Otranto (where it connects to the Ionian Sea) to the ...

. He was called by his contemporaries ''pater antiquitatis'' ('father of antiquity') and today "father of classical archaeology": ''"Cyriac of Ancona was the most enterprising and prolific recorder of Greek and Roman antiquities, particularly inscriptions, in the fifteenth century, and the general accuracy of his records entitles him to be called the founding father of modern classical archeology."'' He traveled throughout Greece and all around the Eastern Mediterranean, to record his findings on ancient buildings, statues and inscriptions, including archaeological remains still unknown to his time: the Parthenon

The Parthenon (; grc, Παρθενών, , ; ell, Παρθενώνας, , ) is a former temple on the Athenian Acropolis, Greece, that was dedicated to the goddess Athena during the fifth century BC. Its decorative sculptures are considere ...

, Delphi

Delphi (; ), in legend previously called Pytho (Πυθώ), in ancient times was a sacred precinct that served as the seat of Pythia, the major oracle who was consulted about important decisions throughout the ancient classical world. The orac ...

, the Egyptian pyramids

The Egyptian pyramids are ancient masonry structures located in Egypt. Sources cite at least 118 identified "Egyptian" pyramids. Approximately 80 pyramids were built within the Kingdom of Kush, now located in the modern country of Sudan. Of ...

, the hieroglyphics

Egyptian hieroglyphs (, ) were the formal writing system used in Ancient Egypt, used for writing the Egyptian language. Hieroglyphs combined logographic, syllabic and alphabetic elements, with some 1,000 distinct characters.There were about 1 ...

. He noted down his archaeological discoveries in his diary, ''Commentaria'' (in six volumes).

Flavio Biondo

Flavio Biondo (Latin Flavius Blondus) (1392 – June 4, 1463) was an Italian Renaissance humanist historian. He was one of the first historians to use a three-period division of history (Ancient, Medieval, Modern) and is known as one of the f ...

, an Italian Renaissance humanist

Renaissance humanism was a revival in the study of classical antiquity, at first in Italy and then spreading across Western Europe in the 14th, 15th, and 16th centuries. During the period, the term ''humanist'' ( it, umanista) referred to teache ...

historian, created a systematic guide to the ruins and topography of ancient Rome in the early 15th century, for which he has been called an early founder of archaeology.

Antiquarians of the 16th century, including John Leland and William Camden

William Camden (2 May 1551 – 9 November 1623) was an English antiquarian, historian, topographer, and herald, best known as author of ''Britannia'', the first chorographical survey of the islands of Great Britain and Ireland, and the ''Ann ...

, conducted surveys of the English countryside, drawing, describing and interpreting the monuments that they encountered.

The OED first cites "archaeologist" from 1824; this soon took over as the usual term for one major branch of antiquarian activity. "Archaeology", from 1607 onwards, initially meant what we would call "ancient history" generally, with the narrower modern sense first seen in 1837.

12th century Indian scholar Kalhana

Kalhana ( sa, कल्हण, translit=kalhaṇa) was the author of ''Rajatarangini'' (''River of Kings''), an account of the history of Kashmir. He wrote the work in Sanskrit between 1148 and 1149. All information regarding his life has to be ...

's writings involved recording of local traditions, examining manuscripts, inscriptions, coins and architectures, which is described as one of the earliest traces of archaeology. One of his notable work is called ''Rajatarangini'' which was completed in and is described as one of the first history books of India.

First excavations

One of the first sites to undergo archaeological excavation was

One of the first sites to undergo archaeological excavation was Stonehenge

Stonehenge is a prehistoric monument on Salisbury Plain in Wiltshire, England, west of Amesbury. It consists of an outer ring of vertical sarsen standing stones, each around high, wide, and weighing around 25 tons, topped by connec ...

and other megalithic monuments

A megalith is a large stone that has been used to construct a prehistoric structure or monument, either alone or together with other stones. There are over 35,000 in Europe alone, located widely from Sweden to the Mediterranean sea.

The ...

in England. John Aubrey

John Aubrey (12 March 1626 – 7 June 1697) was an English antiquary, natural philosopher and writer. He is perhaps best known as the author of the '' Brief Lives'', his collection of short biographical pieces. He was a pioneer archaeologist ...

(1626–1697) was a pioneer archaeologist who recorded numerous megalith

A megalith is a large stone that has been used to construct a prehistoric structure or monument, either alone or together with other stones. There are over 35,000 in Europe alone, located widely from Sweden to the Mediterranean sea.

The ...

ic and other field monuments in southern England. He was also ahead of his time in the analysis of his findings. He attempted to chart the chronological stylistic evolution of handwriting, medieval architecture, costume, and shield-shapes.

Excavations were also carried out by the Spanish military engineer Roque Joaquín de Alcubierre

Roque Joaquín de Alcubierre (16 August 1702 – 14 March 1780) was a military engineer in the Spanish Army who discovered architectural remains at Pompeii and Herculaneum.

Early life

Alcubierre was born and studied in Zaragoza, Spain. When he rea ...

in the ancient towns of Pompeii

Pompeii (, ) was an ancient city located in what is now the ''comune'' of Pompei near Naples in the Campania region of Italy. Pompeii, along with Herculaneum and many villas in the surrounding area (e.g. at Boscoreale, Stabiae), was burie ...

and Herculaneum

Herculaneum (; Neapolitan and it, Ercolano) was an ancient town, located in the modern-day ''comune'' of Ercolano, Campania, Italy. Herculaneum was buried under volcanic ash and pumice in the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in AD 79.

Like the n ...

, both of which had been covered by ash during the Eruption of Mount Vesuvius in AD 79

Of the many eruptions of Mount Vesuvius, a major stratovolcano in southern Italy, the best-known is its eruption in 79 AD, which was one of the deadliest in European history. The eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 AD is one of the best-known in h ...

. These excavations began in 1748 in Pompeii, while in Herculaneum they began in 1738. The discovery of entire towns, complete with utensils and even human shapes, as well the unearthing of fresco

Fresco (plural ''frescos'' or ''frescoes'') is a technique of mural painting executed upon freshly laid ("wet") lime plaster. Water is used as the vehicle for the dry-powder pigment to merge with the plaster, and with the setting of the plast ...

s, had a big impact throughout Europe.

However, prior to the development of modern techniques, excavations tended to be haphazard; the importance of concepts such as stratification

Stratification may refer to:

Mathematics

* Stratification (mathematics), any consistent assignment of numbers to predicate symbols

* Data stratification in statistics

Earth sciences

* Stable and unstable stratification

* Stratification, or st ...

and context

Context may refer to:

* Context (language use), the relevant constraints of the communicative situation that influence language use, language variation, and discourse summary

Computing

* Context (computing), the virtual environment required to s ...

were overlooked.

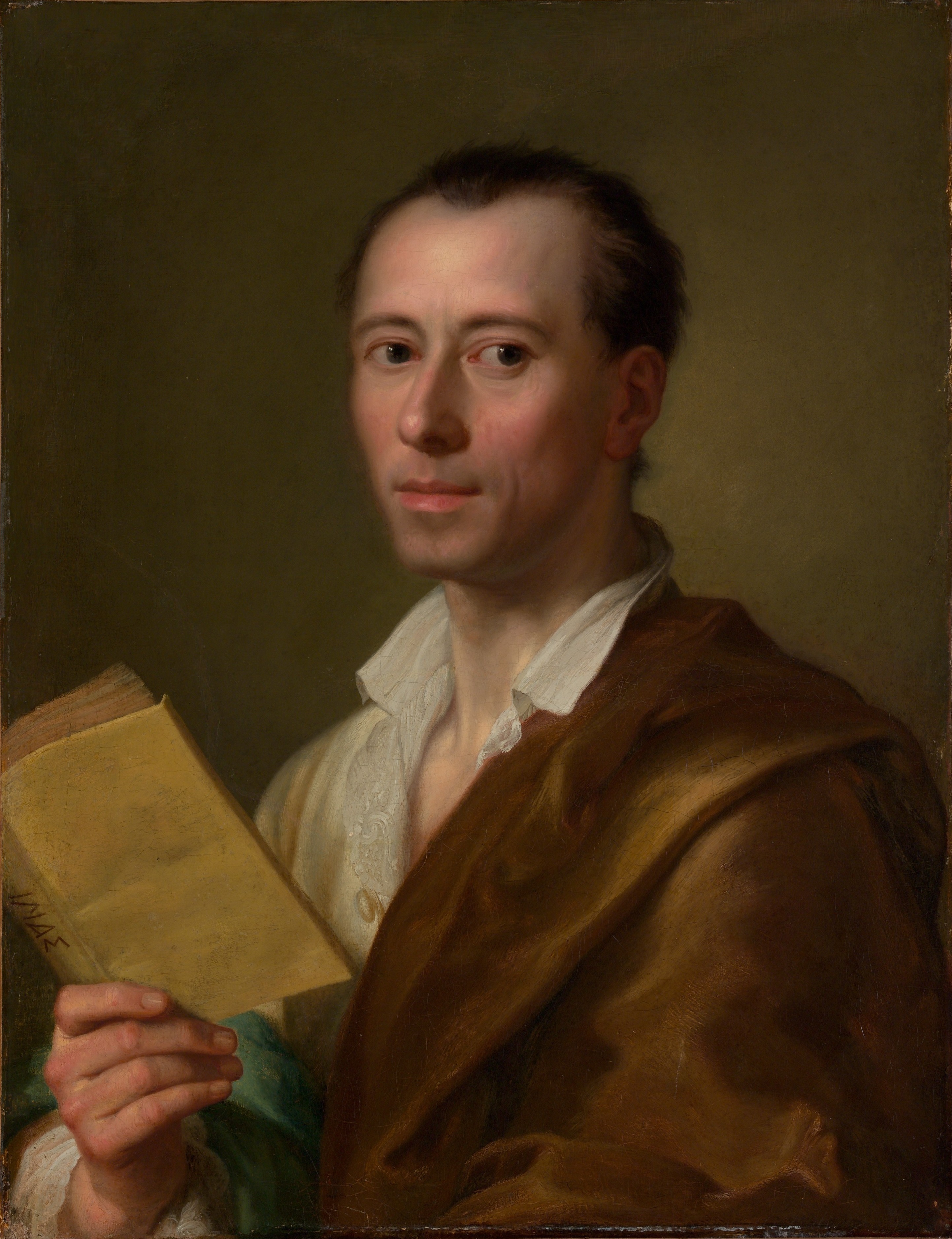

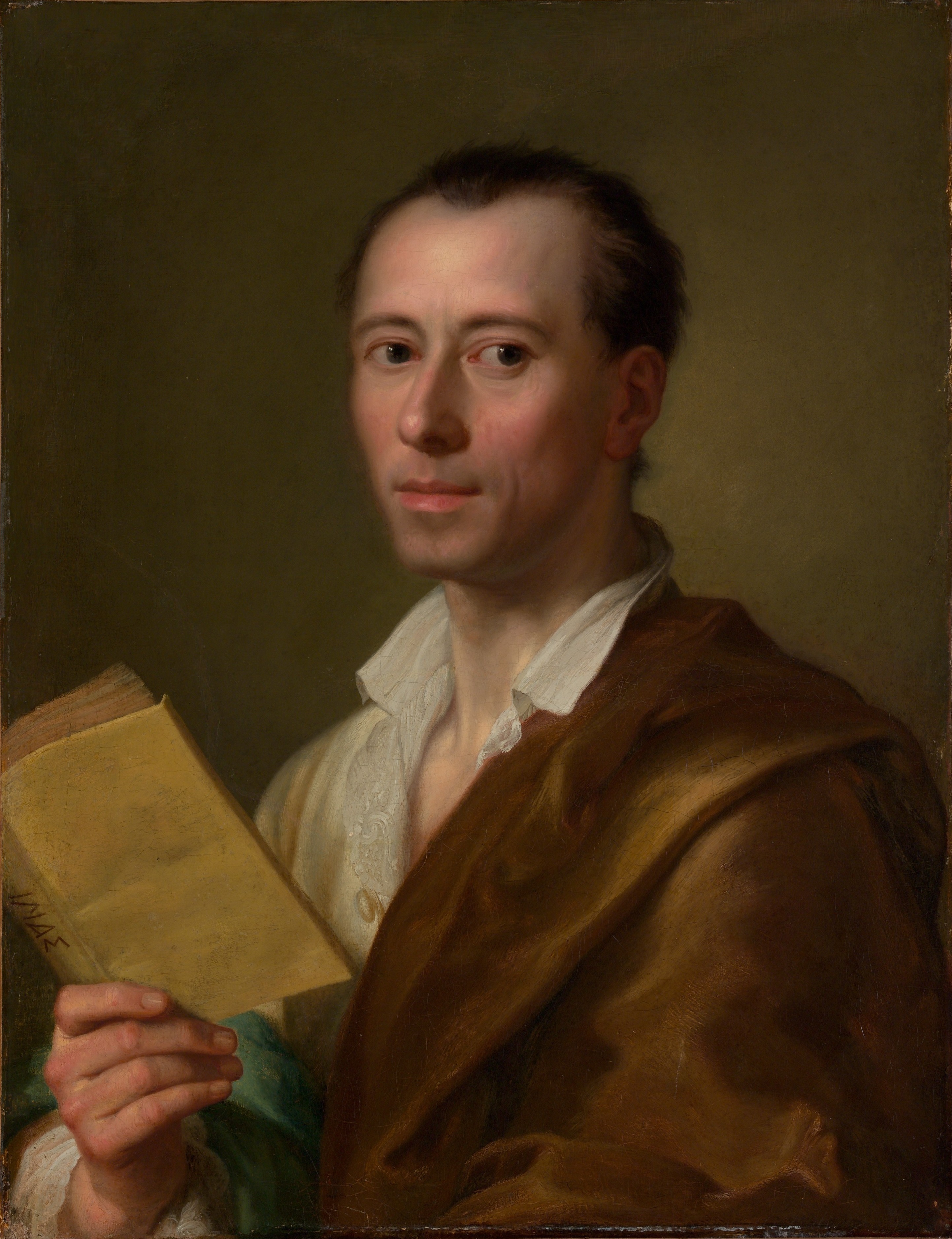

In the mid-18th century, the German Johann Joachim Winckelmann

Johann Joachim Winckelmann (; ; 9 December 17178 June 1768) was a German art historian and archaeologist. He was a pioneering Hellenist who first articulated the differences between Greek, Greco-Roman and Roman art. "The prophet and foundin ...

lived in Rome and devoted himself to the study of Roman antiquities and gradually acquired an unrivalled knowledge of ancient art. Then, he visited the archaeological excavations being conducted at Pompeii

Pompeii (, ) was an ancient city located in what is now the ''comune'' of Pompei near Naples in the Campania region of Italy. Pompeii, along with Herculaneum and many villas in the surrounding area (e.g. at Boscoreale, Stabiae), was burie ...

and Herculaneum

Herculaneum (; Neapolitan and it, Ercolano) was an ancient town, located in the modern-day ''comune'' of Ercolano, Campania, Italy. Herculaneum was buried under volcanic ash and pumice in the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in AD 79.

Like the n ...

. He was one of the founders of scientific archaeology and first applied the categories of style on a large, systematic basis to the history of art

The history of art focuses on objects made by humans for any number of spiritual, narrative, philosophical, symbolic, conceptual, documentary, decorative, and even functional and other purposes, but with a primary emphasis on its aesthetics, ae ...

He was one of the first to separate Greek art into periods and time classifications. Winckelmann has been called both "The prophet and founding hero of modern archaeology

Modern archaeology is the discipline of archaeology which contributes to excavations.

Johann Joachim Winckelmann was one of the founders of scientific archaeology and first applied the categories of style on a large, systematic basis to the h ...

" Boorstin, 584 and the father of the discipline of art history

Art history is the study of aesthetic objects and visual expression in historical and stylistic context. Traditionally, the discipline of art history emphasized painting, drawing, sculpture, architecture, ceramics and decorative arts; yet today, ...

.

Development of archaeological method

The father of archaeological excavation was William Cunnington (1754–1810). He undertook excavations in

The father of archaeological excavation was William Cunnington (1754–1810). He undertook excavations in Wiltshire

Wiltshire (; abbreviated Wilts) is a historic and ceremonial county in South West England with an area of . It is landlocked and borders the counties of Dorset to the southwest, Somerset to the west, Hampshire to the southeast, Gloucestershire ...

from around 1798, funded by Sir Richard Colt Hoare. Cunnington made meticulous recordings of Neolithic

The Neolithic period, or New Stone Age, is an Old World archaeological period and the final division of the Stone Age. It saw the Neolithic Revolution, a wide-ranging set of developments that appear to have arisen independently in several pa ...

and Bronze Age

The Bronze Age is a historic period, lasting approximately from 3300 BC to 1200 BC, characterized by the use of bronze, the presence of writing in some areas, and other early features of urban civilization. The Bronze Age is the second pri ...

barrows, and the terms he used to categorize and describe them are still used by archaeologists today.

One of the major achievements of 19th-century archaeology was the development of stratigraphy

Stratigraphy is a branch of geology concerned with the study of rock layers ( strata) and layering (stratification). It is primarily used in the study of sedimentary and layered volcanic rocks.

Stratigraphy has three related subfields: lithost ...

. The idea of overlapping strata tracing back to successive periods was borrowed from the new geological

Geology () is a branch of natural science concerned with Earth and other astronomical objects, the features or rocks of which it is composed, and the processes by which they change over time. Modern geology significantly overlaps all other E ...

and paleontological

Paleontology (), also spelled palaeontology or palæontology, is the scientific study of life that existed prior to, and sometimes including, the start of the Holocene epoch (roughly 11,700 years before present). It includes the study of foss ...

work of scholars like William Smith, James Hutton

James Hutton (; 3 June O.S.172614 June 1726 New Style. – 26 March 1797) was a Scottish geologist, agriculturalist, chemical manufacturer, naturalist and physician. Often referred to as the father of modern geology, he played a key role ...

and Charles Lyell

Sir Charles Lyell, 1st Baronet, (14 November 1797 – 22 February 1875) was a Scottish geologist who demonstrated the power of known natural causes in explaining the earth's history. He is best known as the author of ''Principles of Geolo ...

. The application of stratigraphy to archaeology first took place with the excavations of prehistorical and Bronze Age

The Bronze Age is a historic period, lasting approximately from 3300 BC to 1200 BC, characterized by the use of bronze, the presence of writing in some areas, and other early features of urban civilization. The Bronze Age is the second pri ...

sites. In the third and fourth decades of the 19th century, archaeologists like Jacques Boucher de Perthes and Christian Jürgensen Thomsen

Christian Jürgensen Thomsen (29 December 1788 – 21 May 1865) was a Danish antiquarian who developed early archaeological techniques and methods.

In 1816 he was appointed head of 'antiquarian' collections which later developed into the Nat ...

began to put the artifacts they had found in chronological order.

A major figure in the development of archaeology into a rigorous science was the army officer and ethnologist

Ethnology (from the grc-gre, ἔθνος, meaning 'nation') is an academic field that compares and analyzes the characteristics of different peoples and the relationships between them (compare cultural, social, or sociocultural anthropolog ...

, Augustus Pitt Rivers

Lieutenant General Augustus Henry Lane Fox Pitt Rivers (14 April 18274 May 1900) was an English officer in the British Army, ethnologist, and archaeologist. He was noted for innovations in archaeological methodology, and in the museum display ...

, who began excavations on his land in England in the 1880s. His approach was highly methodical by the standards of the time, and he is widely regarded as the first scientific archaeologist. He arranged his artifacts by type or " typologically, and within types by date or "chronologically". This style of arrangement, designed to highlight the evolutionary trends in human artifacts, was of enormous significance for the accurate dating of the objects. His most important methodological innovation was his insistence that ''all'' artifacts, not just beautiful or unique ones, be collected and catalogued.

William Flinders Petrie

Sir William Matthew Flinders Petrie ( – ), commonly known as simply Flinders Petrie, was a British Egyptologist and a pioneer of systematic methodology in archaeology and the preservation of artefacts. He held the first chair of Egypt ...

is another man who may legitimately be called the Father of Archaeology. His painstaking recording and study of artifacts, both in Egypt and later in Palestine, laid down many of the ideas behind modern archaeological recording; he remarked that "I believe the true line of research lies in the noting and comparison of the smallest details." Petrie developed the system of dating layers based on pottery and ceramic findings, which revolutionized the chronological basis of Egyptology

Egyptology (from ''Egypt'' and Greek , '' -logia''; ar, علم المصريات) is the study of ancient Egyptian history, language, literature, religion, architecture and art from the 5th millennium BC until the end of its native relig ...

. Petrie was the first to scientifically investigate the Great Pyramid

The Great Pyramid of Giza is the biggest Egyptian pyramid and the tomb of Fourth Dynasty pharaoh Khufu. Built in the early 26th century BC during a period of around 27 years, the pyramid is the oldest of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World ...

in Egypt during the 1880s. He was also responsible for mentoring and training a whole generation of Egyptologists, including Howard Carter

Howard Carter (9 May 18742 March 1939) was a British archaeologist and Egyptologist who discovered the intact tomb of the 18th Dynasty Pharaoh Tutankhamun in November 1922, the best-preserved pharaonic tomb ever found in the Valley of the ...

who went on to achieve fame with the discovery of the tomb of 14th-century BC pharaoh Tutankhamun

Tutankhamun (, egy, twt-ꜥnḫ-jmn), Egyptological pronunciation Tutankhamen () (), sometimes referred to as King Tut, was an Egyptian pharaoh who was the last of his royal family to rule during the end of the Eighteenth Dynasty (ruled ...

.

The first stratigraphic excavation to reach wide popularity with public was that of

The first stratigraphic excavation to reach wide popularity with public was that of Hissarlik

Hisarlik ( Turkish: ''Hisarlık'', "Place of Fortresses"), often spelled Hissarlik, is the Turkish name for an ancient city located in what is known historically as Anatolia.A compound of the noun, hisar, "fortification," and the suffix -lik. The ...

, on the site of ancient Troy

Troy ( el, Τροία and Latin: Troia, Hittite: 𒋫𒊒𒄿𒊭 ''Truwiša'') or Ilion ( el, Ίλιον and Latin: Ilium, Hittite: 𒃾𒇻𒊭 ''Wiluša'') was an ancient city located at Hisarlik in present-day Turkey, south-west of Ç ...

, carried out by Heinrich Schliemann

Johann Ludwig Heinrich Julius Schliemann (; 6 January 1822 – 26 December 1890) was a German businessman and pioneer in the field of archaeology. He was an advocate of the historicity of places mentioned in the works of Homer and an archaeolog ...

, Frank Calvert

Frank Calvert (1828–1908) was an English expatriate who was a consular official in the eastern Mediterranean region and an amateur archaeologist. He began exploratory excavations on the mound at Hisarlik (the site of the ancient city of Troy) ...

and Wilhelm Dörpfeld

Wilhelm Dörpfeld (26 December 1853 – 25 April 1940) was a German architect and archaeologist, a pioneer of stratigraphic excavation and precise graphical documentation of archaeological projects. He is famous for his work on Bronze Age site ...

in the 1870s. These scholars individuated nine different cities that had overlapped with one another, from prehistory to the Hellenistic period

In Classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Mediterranean history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the emergence of the Roman Empire, as signified by the Battle of Actium in ...

. Meanwhile, the work of Sir Arthur Evans

Sir Arthur John Evans (8 July 1851 – 11 July 1941) was a British archaeologist and pioneer in the study of Aegean civilization in the Bronze Age. He is most famous for unearthing the palace of Knossos on the Greek island of Crete. Based on ...

at Knossos

Knossos (also Cnossos, both pronounced ; grc, Κνωσός, Knōsós, ; Linear B: ''Ko-no-so'') is the largest Bronze Age archaeological site on Crete and has been called Europe's oldest city.

Settled as early as the Neolithic period, the na ...

in Crete

Crete ( el, Κρήτη, translit=, Modern: , Ancient: ) is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the 88th largest island in the world and the fifth largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after Sicily, Sardinia, Cyprus, ...

revealed the ancient existence of an equally advanced Minoan civilization

The Minoan civilization was a Bronze Age Aegean civilization on the island of Crete and other Aegean Islands, whose earliest beginnings were from 3500BC, with the complex urban civilization beginning around 2000BC, and then declining from 1450 ...

.

The next major figure in the development of archaeology was Sir Mortimer Wheeler

Sir Robert Eric Mortimer Wheeler CH CIE MC TD (10 September 1890 – 22 July 1976) was a British archaeologist and officer in the British Army. Over the course of his career, he served as Director of both the National Museum of Wales an ...

, whose highly disciplined approach to excavation and systematic coverage in the 1920s and 1930s brought the science on swiftly. Wheeler developed the grid system of excavation, which was further improved by his student Kathleen Kenyon

Dame Kathleen Mary Kenyon, (5 January 1906 – 24 August 1978) was a British archaeologist of Neolithic culture in the Fertile Crescent. She led excavations of Tell es-Sultan, the site of ancient Jericho, from 1952 to 1958, and has been called ...

.

Archaeology became a professional activity in the first half of the 20th century, and it became possible to study archaeology as a subject in universities and even schools. By the end of the 20th century nearly all professional archaeologists, at least in developed countries, were graduates. Further adaptation and innovation in archaeology continued in this period, when maritime archaeology

Maritime archaeology (also known as marine archaeology) is a discipline within archaeology as a whole that specifically studies human interaction with the sea, lakes and rivers through the study of associated physical remains, be they vessels, s ...

and urban archaeology

Urban archaeology is a sub discipline of archaeology specializing in the material past of towns and cities where long-term human habitation has often left a rich record of the past. In modern times, when someone talks about living in a city, the ...

became more prevalent and rescue archaeology

Rescue archaeology, sometimes called commercial archaeology, preventive archaeology, salvage archaeology, contract archaeology, developer-funded archaeology or compliance archaeology, is state-sanctioned, archaeological survey and excavation carr ...

was developed as a result of increasing commercial development.Renfrew and Bahn (2004 991

Year 991 ( CMXCI) was a common year starting on Thursday (link will display the full calendar) of the Julian calendar.

Events

* March 1: In Rouen, Pope John XV ratifies the first Truce of God, between Æthelred the Unready and Richard I of ...

:33–35

Purpose

The purpose of archaeology is to learn more about past societies and the development of the human race. Over 99% of the development of humanity has occurred within prehistoric cultures, who did not make use of

The purpose of archaeology is to learn more about past societies and the development of the human race. Over 99% of the development of humanity has occurred within prehistoric cultures, who did not make use of writing

Writing is a medium of human communication which involves the representation of a language through a system of physically inscribed, mechanically transferred, or digitally represented symbols.

Writing systems do not themselves constitute h ...

, thereby no written records exist for study purposes. Without such written sources, the only way to understand prehistoric societies is through archaeology. Because archaeology is the study of past human activity, it stretches back to about 2.5 million years ago when the first stone tools are found – The Oldowan Industry. Many important developments in human history occurred during prehistory, such as the evolution of humanity during the Paleolithic

The Paleolithic or Palaeolithic (), also called the Old Stone Age (from Greek: παλαιός '' palaios'', "old" and λίθος ''lithos'', "stone"), is a period in human prehistory that is distinguished by the original development of stone too ...

period, when the hominin

The Hominini form a taxonomic tribe of the subfamily Homininae ("hominines"). Hominini includes the extant genera ''Homo'' (humans) and '' Pan'' (chimpanzees and bonobos) and in standard usage excludes the genus ''Gorilla'' (gorillas).

The ...

s developed from the australopithecines

Australopithecina or Hominina is a subtribe in the tribe Hominini. The members of the subtribe are generally ''Australopithecus'' ( cladistically including the genera ''Homo'', '' Paranthropus'', and ''Kenyanthropus''), and it typically include ...

in Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent, after Asia in both cases. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 6% of Earth's total surface area ...

and eventually into modern ''Homo sapiens

Humans (''Homo sapiens'') are the most abundant and widespread species of primate, characterized by bipedalism and exceptional cognitive skills due to a large and complex brain. This has enabled the development of advanced tools, culture ...

''. Archaeology also sheds light on many of humanity's technological advances, for instance the ability to use fire, the development of stone tool

A stone tool is, in the most general sense, any tool made either partially or entirely out of stone. Although stone tool-dependent societies and cultures still exist today, most stone tools are associated with prehistoric (particularly Stone A ...

s, the discovery of metallurgy

Metallurgy is a domain of materials science and engineering that studies the physical and chemical behavior of metallic elements, their inter-metallic compounds, and their mixtures, which are known as alloys.

Metallurgy encompasses both the sc ...

, the beginnings of religion

Religion is usually defined as a social- cultural system of designated behaviors and practices, morals, beliefs, worldviews, texts, sanctified places, prophecies, ethics, or organizations, that generally relates humanity to supernatur ...

and the creation of agriculture

Agriculture or farming is the practice of cultivating plants and livestock. Agriculture was the key development in the rise of sedentary human civilization, whereby farming of domesticated species created food surpluses that enabled people ...

. Without archaeology, little or nothing would be known about the use of material culture by humanity that pre-dates writing.

However, it is not only prehistoric, pre-literate cultures that can be studied using archaeology but historic, literate cultures as well, through the sub-discipline of historical archaeology

Historical archaeology is a form of archaeology dealing with places, things, and issues from the past or present when written records and oral traditions can inform and contextualize cultural material. These records can both complement and conflict ...

. For many literate cultures, such as Ancient Greece

Ancient Greece ( el, Ἑλλάς, Hellás) was a northeastern Mediterranean civilization, existing from the Greek Dark Ages of the 12th–9th centuries BC to the end of classical antiquity ( AD 600), that comprised a loose collection of cu ...

and Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia ''Mesopotamíā''; ar, بِلَاد ٱلرَّافِدَيْن or ; syc, ܐܪܡ ܢܗܪ̈ܝܢ, or , ) is a historical region of Western Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the ...

, their surviving records are often incomplete and biased to some extent. In many societies, literacy was restricted to the elite

In political and sociological theory, the elite (french: élite, from la, eligere, to select or to sort out) are a small group of powerful people who hold a disproportionate amount of wealth, privilege, political power, or skill in a group. ...

classes, such as the clergy

Clergy are formal leaders within established religions. Their roles and functions vary in different religious traditions, but usually involve presiding over specific rituals and teaching their religion's doctrines and practices. Some of the ter ...

, or the bureaucracy

The term bureaucracy () refers to a body of non-elected governing officials as well as to an administrative policy-making group. Historically, a bureaucracy was a government administration managed by departments staffed with non-elected offi ...

of court or temple. The literacy of aristocrats

Aristocracy (, ) is a form of government that places strength in the hands of a small, privileged ruling class, the aristocrats. The term derives from the el, αριστοκρατία (), meaning 'rule of the best'.

At the time of the word' ...

has sometimes been restricted to deeds and contracts. The interests and world-view of elites are often quite different from the lives and interests of the populace. Writings that were produced by people more representative of the general population were unlikely to find their way into libraries

A library is a collection of Document, materials, books or media that are accessible for use and not just for display purposes. A library provides physical (hard copies) or electronic media, digital access (soft copies) materials, and may be a ...

and be preserved there for posterity. Thus, written records tend to reflect the biases, assumptions, cultural values and possibly deceptions of a limited range of individuals, usually a small fraction of the larger population. Hence, written records cannot be trusted as a sole source. The material record may be closer to a fair representation of society, though it is subject to its own biases, such as sampling bias

In statistics, sampling bias is a bias in which a sample is collected in such a way that some members of the intended population have a lower or higher sampling probability than others. It results in a biased sample of a population (or non-human f ...

and differential preservation.

Often, archaeology provides the only means to learn of the existence and behaviors of people of the past. Across the millennia many thousands of cultures and societies and billions of people have come and gone of which there is little or no written record or existing records are misrepresentative or incomplete. Writing as it is known today did not exist in human civilization until the 4th millennium BCE, in a relatively small number of technologically advanced civilizations. In contrast, ''Homo sapiens'' has existed for at least 200,000 years, and other species of ''Homo'' for millions of years (see Human evolution

Human evolution is the evolutionary process within the history of primates that led to the emergence of '' Homo sapiens'' as a distinct species of the hominid family, which includes the great apes. This process involved the gradual developmen ...

). These civilizations are, not coincidentally, the best-known; they are open to the inquiry of historians for centuries, while the study of pre-historic cultures has arisen only recently. Within a literate civilization many events and important human practices may not be officially recorded. Any knowledge of the early years of human civilization – the development of agriculture, cult practices of folk religion, the rise of the first cities – must come from archaeology.

In addition to their scientific importance, archaeological remains sometimes have political or cultural significance to descendants of the people who produced them, monetary value to collectors, or strong aesthetic appeal. Many people identify archaeology with the recovery of such aesthetic, religious, political, or economic treasures rather than with the reconstruction of past societies.

This view is often espoused in works of popular fiction, such as Raiders of the Lost Ark, The Mummy, and King Solomon's Mines. When unrealistic subjects are treated more seriously, accusations of pseudoscience are invariably levelled at their proponents ''(see Pseudoarchaeology

Pseudoarchaeology—also known as alternative archaeology, fringe archaeology, fantastic archaeology, cult archaeology, and spooky archaeology—is the interpretation of the past from outside the archaeological science community, which rejects ...

)''. However, these endeavours, real and fictional, are not representative of modern archaeology.

Theory

There is no one approach to archaeological theory that has been adhered to by all archaeologists. When archaeology developed in the late 19th century, the first approach to archaeological theory to be practiced was that of cultural-history archaeology, which held the goal of explaining why cultures changed and adapted rather than just highlighting the fact that they did, therefore emphasizinghistorical particularism

Historical particularism (coined by Marvin Harris in 1968)Harris, Marvin: ''The Rise of Anthropological Theory: A History of Theories of Culture''. 1968. (Reissued 2001) New York: Thomas Y. Crowell Company is widely considered the first America ...

. In the early 20th century, many archaeologists who studied past societies with direct continuing links to existing ones (such as those of Native Americans, Siberia

Siberia ( ; rus, Сибирь, r=Sibir', p=sʲɪˈbʲirʲ, a=Ru-Сибирь.ogg) is an extensive geographical region, constituting all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has been a part ...

ns, Mesoamerica

Mesoamerica is a historical region and cultural area in southern North America and most of Central America. It extends from approximately central Mexico through Belize, Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua, and northern Costa Rica. Wit ...

ns etc.) followed the direct historical approach

The direct historical approach to archaeology was a methodology developed in the United States of America during the 1920s-1930s by William Duncan Strong and others, which argued that knowledge relating to historical periods is extended back into e ...

, compared the continuity between the past and contemporary ethnic and cultural groups. In the 1960s, an archaeological movement largely led by American archaeologists like Lewis Binford and Kent Flannery

Kent Vaughn Flannery (born 1934) is a North American archaeologist who has conducted and published extensive research on the pre-Columbian cultures and civilizations of Mesoamerica, and in particular those of central and southern Mexico. He has a ...

arose that rebelled against the established cultural-history archaeology. They proposed a "New Archaeology", which would be more "scientific" and "anthropological", with hypothesis

A hypothesis (plural hypotheses) is a proposed explanation for a phenomenon. For a hypothesis to be a scientific hypothesis, the scientific method requires that one can test it. Scientists generally base scientific hypotheses on previous obse ...

testing and the scientific method

The scientific method is an empirical method for acquiring knowledge that has characterized the development of science since at least the 17th century (with notable practitioners in previous centuries; see the article history of scientifi ...

very important parts of what became known as processual archaeology.

In the 1980s, a new postmodern

Postmodernism is an intellectual stance or Rhetorical modes, mode of discourseNuyen, A.T., 1992. The Role of Rhetorical Devices in Postmodernist Discourse. Philosophy & Rhetoric, pp.183–194. characterized by philosophical skepticism, skepticis ...

movement arose led by the British archaeologists Michael Shanks

Michael Garrett Shanks (born December 15, 1970) is a Canadian actor, writer and director. He is best known for his role as Daniel Jackson in the long-running military science fiction television series '' Stargate SG-1'' and as Charles Harris ...

, Christopher Tilley

__NOTOC__

Chris Tilley is a British archaeologist known for his contributions to postprocessualist archaeological theory. He is currently a Professor of Anthropology and Archaeology at University College London.

Tilley obtained his PhD in Anth ...

, Daniel Miller, and Ian Hodder

Ian Richard Hodder (born 23 November 1948, in Bristol) is a British archaeologist and pioneer of postprocessualist theory in archaeology that first took root among his students and in his own work between 1980–1990. At this time he had suc ...

, which has become known as post-processual archaeology

Post-processual archaeology, which is sometimes alternately referred to as the interpretative archaeologies by its adherents, is a movement in archaeological theory that emphasizes the subjectivity of archaeological interpretations. Despite having ...

. It questioned processualism's appeals to scientific positivism and impartiality, and emphasized the importance of a more self-critical theoretical reflexivity. However, this approach has been criticized by processualists as lacking scientific rigor, and the validity of both processualism and post-processualism is still under debate. Meanwhile, another theory, known as historical processualism

History (derived ) is the systematic study and the documentation of the human activity. The time period of event before the invention of writing systems is considered prehistory. "History" is an umbrella term comprising past events as wel ...

, has emerged seeking to incorporate a focus on process and post-processual archaeology's emphasis of reflexivity and history.

Archaeological theory now borrows from a wide range of influences, including neo-evolutionary thought, 5/span> phenomenology

Phenomenology may refer to:

Art

* Phenomenology (architecture), based on the experience of building materials and their sensory properties

Philosophy

* Phenomenology (philosophy), a branch of philosophy which studies subjective experiences and a ...

, postmodernism

Postmodernism is an intellectual stance or mode of discourseNuyen, A.T., 1992. The Role of Rhetorical Devices in Postmodernist Discourse. Philosophy & Rhetoric, pp.183–194. characterized by skepticism toward the " grand narratives" of modern ...

, agency theory, cognitive science, structural functionalism

Structural functionalism, or simply functionalism, is "a framework for building theory that sees society as a complex system whose parts work together to promote solidarity and stability".

This approach looks at society through a macro-level o ...

, gender-based and feminist archaeology

Feminist archaeology employs a feminist perspective in interpreting past societies. It often focuses on gender, but also considers gender in tandem with other factors, such as sexuality, race, or class. Feminist archaeology has critiqued the ...

, and systems theory

Systems theory is the interdisciplinary study of systems, i.e. cohesive groups of interrelated, interdependent components that can be natural or human-made. Every system has causal boundaries, is influenced by its context, defined by its structu ...

.

Methods

An archaeological investigation usually involves several distinct phases, each of which employs its own variety of methods. Before any practical work can begin, however, a clear objective as to what the archaeologists are looking to achieve must be agreed upon. This done, a site issurveyed

Surveying or land surveying is the technique, profession, art, and science of determining the land, terrestrial Two-dimensional space#In geometry, two-dimensional or Three-dimensional space#In Euclidean geometry, three-dimensional positions of ...

to find out as much as possible about it and the surrounding area. Second, an excavation may take place to uncover any archaeological features buried under the ground. And, third, the information collected during the excavation is studied and evaluated in an attempt to achieve the original research objectives of the archaeologists. It is then considered good practice for the information to be published so that it is available to other archaeologists and historians, although this is sometimes neglected.

Remote sensing

Before actually starting to dig in a location,remote sensing

Remote sensing is the acquisition of information about an object or phenomenon without making physical contact with the object, in contrast to in situ or on-site observation. The term is applied especially to acquiring information about Ear ...

can be used to look where sites are located within a large area or provide more information about sites or regions. There are two types of remote sensing instruments—passive and active. Passive instruments detect natural energy that is reflected or emitted from the observed scene. Passive instruments sense only radiation emitted by the object being viewed or reflected by the object from a source other than the instrument. Active instruments emit energy and record what is reflected. Satellite imagery

Satellite images (also Earth observation imagery, spaceborne photography, or simply satellite photo) are images of Earth collected by imaging satellites operated by governments and businesses around the world. Satellite imaging companies sell ima ...

is an example of passive remote sensing. Here are two active remote sensing instruments:

* Lidar: Lidar

Lidar (, also LIDAR, or LiDAR; sometimes LADAR) is a method for determining ranges (variable distance) by targeting an object or a surface with a laser and measuring the time for the reflected light to return to the receiver. It can also be ...

(light detection and ranging) uses a laser (light amplification by stimulated emission of radiation) to transmit a light pulse and a receiver with sensitive detectors to measure the backscattered or reflected light. Distance to the object is determined by recording the time between the transmitted and backscattered pulses and using the speed of light to calculate the distance travelled. Lidars can determine atmospheric profiles of aerosols, clouds, and other constituents of the atmosphere.

* Laser altimeter: A laser altimeter uses a lidar (see above) to measure the height of the instrument platform above the surface. By independently knowing the height of the platform with respect to the mean Earth's surface, the topography of the underlying surface can be determined.

Field survey

The archaeological project then continues (or alternatively, begins) with a

The archaeological project then continues (or alternatively, begins) with a field survey

Field research, field studies, or fieldwork is the collection of raw data outside a laboratory, library, or workplace setting. The approaches and methods used in field research vary across disciplines. For example, biologists who conduct fi ...

. Regional survey is the attempt to systematically locate previously unknown sites in a region. Site survey is the attempt to systematically locate features of interest, such as houses and midden

A midden (also kitchen midden or shell heap) is an old dump for domestic waste which may consist of animal bone, human excrement, botanical material, mollusc shells, potsherds, lithics (especially debitage), and other artifacts and eco ...

s, within a site. Each of these two goals may be accomplished with largely the same methods.

Survey was not widely practiced in the early days of archaeology. Cultural historians and prior researchers were usually content with discovering the locations of monumental sites from the local populace, and excavating only the plainly visible features

Feature may refer to:

Computing

* Feature (CAD), could be a hole, pocket, or notch

* Feature (computer vision), could be an edge, corner or blob

* Feature (software design) is an intentional distinguishing characteristic of a software ite ...

there. Gordon Willey

Gordon Randolph Willey (7 March 1913 – 28 April 2002) was an American archaeologist who was described by colleagues as the "dean" of New World archaeology.Sabloff 2004, p.406 Willey performed fieldwork at excavations in South America, Central A ...

pioneered the technique of regional settlement pattern survey in 1949 in the Viru Valley

The Viru Valley is located in La Libertad Region on the north west coast of Peru.

The Viru Valley Project

In 1946 the first attempt to study settlement patterns in the Americas took place in the Viru Valley, led by Gordon Willey. Rather than exa ...

of coastal Peru

, image_flag = Flag of Peru.svg

, image_coat = Escudo nacional del Perú.svg

, other_symbol = Great Seal of the State

, other_symbol_type = National seal

, national_motto = "Firm and Happy f ...

, and survey of all levels became prominent with the rise of processual archaeology some years later.

Survey work has many benefits if performed as a preliminary exercise to, or even in place of, excavation. It requires relatively little time and expense, because it does not require processing large volumes of soil to search out artifacts. (Nevertheless, surveying a large region or site can be expensive, so archaeologists often employ sampling methods.) As with other forms of non-destructive archaeology, survey avoids ethical issues (of particular concern to descendant peoples) associated with destroying a site through excavation. It is the only way to gather some forms of information, such as settlement patterns and settlement structure. Survey data are commonly assembled into map

A map is a symbolic depiction emphasizing relationships between elements of some space, such as objects, regions, or themes.

Many maps are static, fixed to paper or some other durable medium, while others are dynamic or interactive. Although ...

s, which may show surface features and/or artifact distribution.

The simplest survey technique is surface survey. It involves combing an area, usually on foot but sometimes with the use of mechanized transport, to search for features or artifacts visible on the surface. Surface survey cannot detect sites or features that are completely buried under earth, or overgrown with vegetation. Surface survey may also include mini-excavation techniques such as augers, corers, and

The simplest survey technique is surface survey. It involves combing an area, usually on foot but sometimes with the use of mechanized transport, to search for features or artifacts visible on the surface. Surface survey cannot detect sites or features that are completely buried under earth, or overgrown with vegetation. Surface survey may also include mini-excavation techniques such as augers, corers, and shovel test

A shovel test pit (STP) is a standard method for Phase I of an archaeological survey. It is usually a part of the Cultural Resources Management (CRM) methodology and a popular form of rapid archaeological survey in the United States of America an ...

pits. If no materials are found, the area surveyed is deemed sterile

Sterile or sterility may refer to:

*Asepsis

Asepsis is the state of being free from disease-causing micro-organisms (such as pathogenic bacteria, viruses, pathogenic fungi, and parasites). There are two categories of asepsis: medical and surgi ...

.

Aerial survey

Aerial survey is a method of collecting geomatics or other imagery by using airplanes, helicopters, UAVs, balloons or other aerial methods. Typical types of data collected include aerial photography, Lidar, remote sensing (using various visible ...

is conducted using camera

A camera is an optical instrument that can capture an image. Most cameras can capture 2D images, with some more advanced models being able to capture 3D images. At a basic level, most cameras consist of sealed boxes (the camera body), with ...

s attached to airplane

An airplane or aeroplane (informally plane) is a fixed-wing aircraft that is propelled forward by thrust from a jet engine, propeller, or rocket engine. Airplanes come in a variety of sizes, shapes, and wing configurations. The broad ...

s, balloons

A balloon is a flexible bag that can be inflated with a gas, such as helium, hydrogen, nitrous oxide, oxygen, and air. For special tasks, balloons can be filled with smoke, liquid water, granular media (e.g. sand, flour or rice), or light s ...

, UAVs

An unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV), commonly known as a drone, is an aircraft without any human pilot, crew, or passengers on board. UAVs are a component of an unmanned aircraft system (UAS), which includes adding a ground-based controlle ...

, or even Kite

A kite is a tethered heavier-than-air or lighter-than-air craft with wing surfaces that react against the air to create lift and drag forces. A kite consists of wings, tethers and anchors. Kites often have a bridle and tail to guide the fac ...

s. A bird's-eye view is useful for quick mapping of large or complex sites. Aerial photographs are used to document the status of the archaeological dig. Aerial imaging can also detect many things not visible from the surface. Plant

Plants are predominantly photosynthetic eukaryotes of the kingdom Plantae. Historically, the plant kingdom encompassed all living things that were not animals, and included algae and fungi; however, all current definitions of Plantae excl ...