Anarchism in Ukraine on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Anarchism in Ukraine has its roots in the democratic and egalitarian organization of the

Anarchism in Ukraine has its roots in the democratic and egalitarian organization of the

By this time, the

By this time, the

The most prominent of the ''hromadas'' was the one in Kyiv, founded in 1859 by populist students of the Lavrovist tendency, who emphasised the education of the peasantry and rejected revolutionary agitation. It was banned by 1863 but renewed its educational activities in 1869, spearheaded by a new generation of students led by

The most prominent of the ''hromadas'' was the one in Kyiv, founded in 1859 by populist students of the Lavrovist tendency, who emphasised the education of the peasantry and rejected revolutionary agitation. It was banned by 1863 but renewed its educational activities in 1869, spearheaded by a new generation of students led by  In 1874, the Narodniks' "

In 1874, the Narodniks' "

Juda Grossman described the rise of anarchist groups in the wake of the revolution as though they "sprang up like mushrooms after a rain". Jewish anarchist groups sprouted up throughout many of the small towns in the Pale, while in the cities of Ukraine, the anarchist movement that had first appeared in Odesa and Katerynoslav had spread to Kyiv and Kharkiv. In

Juda Grossman described the rise of anarchist groups in the wake of the revolution as though they "sprang up like mushrooms after a rain". Jewish anarchist groups sprouted up throughout many of the small towns in the Pale, while in the cities of Ukraine, the anarchist movement that had first appeared in Odesa and Katerynoslav had spread to Kyiv and Kharkiv. In  The

The

The outbreak of the

The outbreak of the  In July, attempts were made to unify the revolutionary anarchist movement, with an anarchist conference in Kharkiv discussing the revolutionary role of factory committees versus trade unions and how they could convert the world war into a

In July, attempts were made to unify the revolutionary anarchist movement, with an anarchist conference in Kharkiv discussing the revolutionary role of factory committees versus trade unions and how they could convert the world war into a

Fleeing from the repression in Petrograd and Moscow, Russian anarchists sought asylum in the "

Fleeing from the repression in Petrograd and Moscow, Russian anarchists sought asylum in the " The region of

The region of  The Makhnovists remained on good terms with the Bolsheviks at this time. When famine threatened Petrograd and Moscow, Huliaipole's Ukrainian peasants exported large amounts of grain to the Russian cities, while Makhno himself was cast as a "courageous partisan" by the Soviet press. By March 1919, the Insurgent Army had even been absorbed into the

The Makhnovists remained on good terms with the Bolsheviks at this time. When famine threatened Petrograd and Moscow, Huliaipole's Ukrainian peasants exported large amounts of grain to the Russian cities, while Makhno himself was cast as a "courageous partisan" by the Soviet press. By March 1919, the Insurgent Army had even been absorbed into the  The Makhnovists resolved to defend their territory against both the Red and the White armies, with Trotsky again declaring Makhno an outlaw and the Makhnovists producing propaganda to persuade Red Army soldiers not to take up arms against them. The Makhnovists led the Red Army offensive into a protracted guerrilla war, causing great losses on both sides. The deaths were exacerbated by a typhus epidemic, which even struck Volin, resulting him in being captured by the Bolsheviks. But in October 1920,

The Makhnovists resolved to defend their territory against both the Red and the White armies, with Trotsky again declaring Makhno an outlaw and the Makhnovists producing propaganda to persuade Red Army soldiers not to take up arms against them. The Makhnovists led the Red Army offensive into a protracted guerrilla war, causing great losses on both sides. The deaths were exacerbated by a typhus epidemic, which even struck Volin, resulting him in being captured by the Bolsheviks. But in October 1920,  Following the dissolution of the

Following the dissolution of the

With the Bolsheviks' attention turned to its ongoing internal conflict between

With the Bolsheviks' attention turned to its ongoing internal conflict between  By 1924, there were anarchist groups in at least 28 Ukrainian cities. In the Odesa alone, there were three anarchist workers' circles, a youth group, a published journal and a library, with the police knowing of hundreds of anarchists in the city. Anarchists also organized within independent groups that were disconnected from the anarchist movement, such as Esperanto clubs and

By 1924, there were anarchist groups in at least 28 Ukrainian cities. In the Odesa alone, there were three anarchist workers' circles, a youth group, a published journal and a library, with the police knowing of hundreds of anarchists in the city. Anarchists also organized within independent groups that were disconnected from the anarchist movement, such as Esperanto clubs and

But the Ukrainian new left that had first constituted itself during the period of

But the Ukrainian new left that had first constituted itself during the period of

Anarchism in Ukraine has its roots in the democratic and egalitarian organization of the

Anarchism in Ukraine has its roots in the democratic and egalitarian organization of the Zaporozhian Cossacks

The Zaporozhian Cossacks, Zaporozhian Cossack Army, Zaporozhian Host, (, or uk, Військо Запорізьке, translit=Viisko Zaporizke, translit-std=ungegn, label=none) or simply Zaporozhians ( uk, Запорожці, translit=Zaporoz ...

, who inhabited the region up until the 18th century. Philosophical anarchism

Philosophical anarchism is an anarchist school of thought which focuses on intellectual criticism of authority, especially political power, and the legitimacy of governments. The American anarchist and socialist Benjamin Tucker coined the term '' ...

first emerged from the radical

Radical may refer to:

Politics and ideology Politics

*Radical politics, the political intent of fundamental societal change

*Radicalism (historical), the Radical Movement that began in late 18th century Britain and spread to continental Europe and ...

movement during the Ukrainian national revival, finding a literary expression in the works of Mykhailo Drahomanov

Mykhailo Petrovych Drahomanov ( ukr, Михайло Петрович Драгоманов; 18 September 1841 – 2 July 1895) was a Ukrainian intellectual and public figure. As an academic, Drahomanov was an economist, historian, philosopher, and ...

, who was himself inspired by the libertarian socialism

Libertarian socialism, also known by various other names, is a left-wing,Diemer, Ulli (1997)"What Is Libertarian Socialism?" The Anarchist Library. Retrieved 4 August 2019. anti-authoritarian, anti-statist and libertarianLong, Roderick T. (201 ...

of Pierre-Joseph Proudhon

Pierre-Joseph Proudhon (, , ; 15 January 1809, Besançon – 19 January 1865, Paris) was a French socialist,Landauer, Carl; Landauer, Hilde Stein; Valkenier, Elizabeth Kridl (1979) 959 "The Three Anticapitalistic Movements". ''European Socia ...

. The spread of populist

Populism refers to a range of political stances that emphasize the idea of "the people" and often juxtapose this group against " the elite". It is frequently associated with anti-establishment and anti-political sentiment. The term developed ...

ideas by the Narodniks

The Narodniks (russian: народники, ) were a politically conscious movement of the Russian intelligentsia in the 1860s and 1870s, some of whom became involved in revolutionary agitation against tsarism. Their ideology, known as Narodism, ...

also lay the groundwork for the adoption of anarchism by Ukraine's working classes, gaining notable circulation in the Jewish communities

Jewish ethnic divisions refer to many distinctive communities within the world's ethnically Jewish population. Although considered a self-identifying ethnicity, there are distinct ethnic subdivisions among Jews, most of which are primarily the ...

of the Pale of Settlement

The Pale of Settlement (russian: Черта́ осе́длости, '; yi, דער תּחום-המושבֿ, '; he, תְּחוּם הַמּוֹשָב, ') was a western region of the Russian Empire with varying borders that existed from 1791 to 19 ...

.

By the outbreak of the 1905 Revolution, a specifically anarchist movement had risen to prominence in Ukraine. The ideas of anarcho-communism

Anarcho-communism, also known as anarchist communism, (or, colloquially, ''ancom'' or ''ancomm'') is a political philosophy and anarchist school of thought that advocates communism. It calls for the abolition of private property but retains res ...

, anarcho-syndicalism

Anarcho-syndicalism is a political philosophy and anarchist school of thought that views revolutionary industrial unionism or syndicalism as a method for workers in capitalist society to gain control of an economy and thus control influence in b ...

and individualist anarchism

Individualist anarchism is the branch of anarchism that emphasizes the individual and their Will (philosophy), will over external determinants such as groups, society, traditions and ideological systems."What do I mean by individualism? I mean ...

all took root in Ukrainian revolutionary circles, with syndicalism itself developing a notably strong hold in Odesa

Odesa (also spelled Odessa) is the third most populous city and municipality in Ukraine and a major seaport and transport hub located in the south-west of the country, on the northwestern shore of the Black Sea. The city is also the administrative ...

, while acts of anarchist terrorism by cells such as the Black Banner became more commonplace. After the revolution was suppressed, Ukrainian anarchism began to reorganize itself, culminating in the outburst following the February Revolution

The February Revolution ( rus, Февра́льская револю́ция, r=Fevral'skaya revolyutsiya, p=fʲɪvˈralʲskəjə rʲɪvɐˈlʲutsɨjə), known in Soviet historiography as the February Bourgeois Democratic Revolution and somet ...

, when Nestor Makhno

Nestor Ivanovych Makhno, The surname "Makhno" ( uk, Махно́) was itself a corruption of Nestor's father's surname "Mikhnenko" ( uk, Міхненко). ( 1888 – 25 July 1934), also known as Bat'ko Makhno ("Father Makhno"),; According to ...

returned to the country and began to organize among the peasantry.

Ukraine became a stronghold of anarchism during the revolutionary period, acting as a counterweight to Ukrainian nationalism

Ukrainian nationalism refers to the promotion of the unity of Ukrainians as a people and it also refers to the promotion of the identity of Ukraine as a nation state. The nation building that arose as nationalism grew following the French Revol ...

, Russian imperialism

Russian imperialism includes the policy and ideology of power exerted by Russia, as well as its antecedent states, over other countries and external territories. This includes the conquests of the Russian Empire, the imperial actions of the Soviet ...

and Bolshevism

Bolshevism (from Bolshevik) is a revolutionary socialist current of Soviet Marxist–Leninist political thought and political regime associated with the formation of a rigidly centralized, cohesive and disciplined party of social revolution, fo ...

. The Revolutionary Insurgent Army of Ukraine

The Revolutionary Insurgent Army of Ukraine ( uk, Революційна Повстанська Армія України), also known as the Black Army or as Makhnovtsi ( uk, Махновці), named after their leader Nestor Makhno, was a ...

(RIAU), led by Makhno, carved out an anarchist territory in the south

South is one of the cardinal directions or Points of the compass, compass points. The direction is the opposite of north and is perpendicular to both east and west.

Etymology

The word ''south'' comes from Old English ''sūþ'', from earlier Pro ...

-east

East or Orient is one of the four cardinal directions or points of the compass. It is the opposite direction from west and is the direction from which the Sun rises on the Earth.

Etymology

As in other languages, the word is formed from the fa ...

of the country, centered in the former cossack lands of Zaporizhzhia

Zaporizhzhia ( uk, Запоріжжя) or Zaporozhye (russian: Запорожье) is a city in southeast Ukraine, situated on the banks of the Dnieper, Dnieper River. It is the Capital city, administrative centre of Zaporizhzhia Oblast. Zapor ...

. By 1921, the Ukrainian anarchist movement was defeated by the Bolsheviks

The Bolsheviks (russian: Большевики́, from большинство́ ''bol'shinstvó'', 'majority'),; derived from ''bol'shinstvó'' (большинство́), "majority", literally meaning "one of the majority". also known in English ...

, who established the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic

The Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic ( uk, Украї́нська Радя́нська Соціалісти́чна Респу́бліка, ; russian: Украи́нская Сове́тская Социалисти́ческая Респ ...

in its place.

Anarchism experienced a brief resurgence in Ukraine during the time of the New Economic Policy

The New Economic Policy (NEP) () was an economic policy of the Soviet Union proposed by Vladimir Lenin in 1921 as a temporary expedient. Lenin characterized the NEP in 1922 as an economic system that would include "a free market and capitalism, ...

, but was again defeated following the rise of totalitarianism

Totalitarianism is a form of government and a political system that prohibits all opposition parties, outlaws individual and group opposition to the state and its claims, and exercises an extremely high if not complete degree of control and reg ...

under the rule of Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as General Secreta ...

. Further expressions of anarchism existed in the breach of Soviet Ukrainian history, before finally reemerging onto the public sphere following the dissolution of the Soviet Union

The dissolution of the Soviet Union, also negatively connoted as rus, Разва́л Сове́тского Сою́за, r=Razvál Sovétskogo Soyúza, ''Ruining of the Soviet Union''. was the process of internal disintegration within the Sov ...

. In the 21st century, the Ukrainian anarchist movement has experienced a resurgence, itself coming into conflict with the rising far-right

Far-right politics, also referred to as the extreme right or right-wing extremism, are political beliefs and actions further to the right of the left–right political spectrum than the standard political right, particularly in terms of being ...

following Euromaidan

Euromaidan (; uk, Євромайдан, translit=Yevromaidan, lit=Euro Square, ), or the Maidan Uprising, was a wave of Political demonstration, demonstrations and civil unrest in Ukraine, which began on 21 November 2013 with large protes ...

.

History

At the western-most point of theEurasian Steppe

The Eurasian Steppe, also simply called the Great Steppe or the steppes, is the vast steppe ecoregion of Eurasia in the temperate grasslands, savannas and shrublands biome. It stretches through Hungary, Bulgaria, Romania, Moldova and Transnistri ...

, the lands today known as Ukraine came under the control of a number of nomadic societies from the 5th century BCE. First came the Indo-European

The Indo-European languages are a language family native to the overwhelming majority of Europe, the Iranian plateau, and the northern Indian subcontinent. Some European languages of this family, English, French, Portuguese, Russian, Dutc ...

Scythians

The Scythians or Scyths, and sometimes also referred to as the Classical Scythians and the Pontic Scythians, were an Ancient Iranian peoples, ancient Eastern Iranian languages, Eastern

* : "In modern scholarship the name 'Sakas' is reserved f ...

and Sarmatians

The Sarmatians (; grc, Σαρμαται, Sarmatai; Latin: ) were a large confederation of Ancient Iranian peoples, ancient Eastern Iranian languages, Eastern Iranian peoples, Iranian Eurasian nomads, equestrian nomadic peoples of classical ant ...

, then the Turkic Khazars

The Khazars ; he, כּוּזָרִים, Kūzārīm; la, Gazari, or ; zh, 突厥曷薩 ; 突厥可薩 ''Tūjué Kěsà'', () were a semi-nomadic Turkic people that in the late 6th-century CE established a major commercial empire coverin ...

, Pechenegs

The Pechenegs () or Patzinaks tr, Peçenek(ler), Middle Turkic: , ro, Pecenegi, russian: Печенег(и), uk, Печеніг(и), hu, Besenyő(k), gr, Πατζινάκοι, Πετσενέγοι, Πατζινακίται, ka, პა� ...

and Cumans

The Cumans (or Kumans), also known as Polovtsians or Polovtsy (plural only, from the Russian language, Russian Exonym and endonym, exonym ), were a Turkic people, Turkic nomadic people comprising the western branch of the Cuman–Kipchak confede ...

, before the migration

Migration, migratory, or migrate may refer to: Human migration

* Human migration, physical movement by humans from one region to another

** International migration, when peoples cross state boundaries and stay in the host state for some minimum le ...

of Slavs

Slavs are the largest European ethnolinguistic group. They speak the various Slavic languages, belonging to the larger Balto-Slavic branch of the Indo-European languages. Slavs are geographically distributed throughout northern Eurasia, main ...

to the region. By the 9th century CE, these Slavs became known as the Rus

Rus or RUS may refer to:

People and places

* Rus (surname), a Romanian-language surname

* East Slavic historical territories and peoples (). See Names of Rus', Russia and Ruthenia

** Rus' people, the people of Rus'

** Rus' territories

*** Kievan ...

and had formed a loose federation of principalities, with Kyiv

Kyiv, also spelled Kiev, is the capital and most populous city of Ukraine. It is in north-central Ukraine along the Dnieper, Dnieper River. As of 1 January 2021, its population was 2,962,180, making Kyiv the List of European cities by populat ...

as its center. The Rus were converted to Orthodox Christianity

Orthodoxy (from Ancient Greek, Greek: ) is adherence to correct or accepted creeds, especially in religion.

Orthodoxy within Christianity refers to acceptance of the doctrines defined by various creeds and ecumenical councils in Late antiquity, A ...

over the following century, before being invaded

An invasion is a military offensive in which large numbers of combatants of one geopolitical entity aggressively enter territory owned by another such entity, generally with the objective of either: conquering; liberating or re-establishing con ...

by the Mongol Empire

The Mongol Empire of the 13th and 14th centuries was the largest contiguous land empire in history. Originating in present-day Mongolia in East Asia, the Mongol Empire at its height stretched from the Sea of Japan to parts of Eastern Europe, ...

, which brought about the collapse of Kyivan rule. While ruled by the Golden Horde

The Golden Horde, self-designated as Ulug Ulus, 'Great State' in Turkic, was originally a Mongols, Mongol and later Turkicized khanate established in the 13th century and originating as the northwestern sector of the Mongol Empire. With the fr ...

, the northern states under the rule of Moscow

Moscow ( , US chiefly ; rus, links=no, Москва, r=Moskva, p=mɐskˈva, a=Москва.ogg) is the capital and largest city of Russia. The city stands on the Moskva River in Central Russia, with a population estimated at 13.0 million ...

became known as "Russia", while the southern borderlands came to be known as "Ukraine". After the fall of the Horde, Ukraine became a battleground between the competing Polish

Polish may refer to:

* Anything from or related to Poland, a country in Europe

* Polish language

* Poles

Poles,, ; singular masculine: ''Polak'', singular feminine: ''Polka'' or Polish people, are a West Slavic nation and ethnic group, w ...

, Russian

Russian(s) refers to anything related to Russia, including:

*Russians (, ''russkiye''), an ethnic group of the East Slavic peoples, primarily living in Russia and neighboring countries

*Rossiyane (), Russian language term for all citizens and peo ...

and Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

s, which brought about the development of a distinct Ukrainian culture

The culture of Ukraine is the composite of the material and spiritual values of the Ukrainian people that has formed throughout the history of Ukraine. It is closely intertwined with ethnic studies about ethnic Ukrainians and Ukrainian historiog ...

.

By this time, the

By this time, the Cossacks

The Cossacks , es, cosaco , et, Kasakad, cazacii , fi, Kasakat, cazacii , french: cosaques , hu, kozákok, cazacii , it, cosacchi , orv, коза́ки, pl, Kozacy , pt, cossacos , ro, cazaci , russian: казаки́ or ...

had emerged from the conflict, establishing themselves along the banks of the Don

Don, don or DON and variants may refer to:

Places

*County Donegal, Ireland, Chapman code DON

*Don (river), a river in European Russia

*Don River (disambiguation), several other rivers with the name

*Don, Benin, a town in Benin

*Don, Dang, a vill ...

and Dniepr

}

The Dnieper () or Dnipro (); , ; . is one of the major transboundary rivers of Europe, rising in the Valdai Hills near Smolensk, Russia, before flowing through Belarus and Ukraine to the Black Sea. It is the longest river of Ukraine and ...

rivers, where they practiced a form of participatory democracy

Participatory democracy, participant democracy or participative democracy is a form of government in which citizens participate individually and directly in political decisions and policies that affect their lives, rather than through elected rep ...

in popular assemblies

A popular assembly (or people's assembly) is a gathering called to address issues of importance to participants. Assemblies tend to be freely open to participation and operate by direct democracy. Some assemblies are of people from a location ...

(''Krugs'') and elected their own military leaders (''Ataman

Ataman (variants: ''otaman'', ''wataman'', ''vataman''; Russian: атаман, uk, отаман) was a title of Cossack and haidamak leaders of various kinds. In the Russian Empire, the term was the official title of the supreme military comman ...

s''). While other cossacks would end up pledging their loyalty to one state or another, the Zaporozhian Cossacks

The Zaporozhian Cossacks, Zaporozhian Cossack Army, Zaporozhian Host, (, or uk, Військо Запорізьке, translit=Viisko Zaporizke, translit-std=ungegn, label=none) or simply Zaporozhians ( uk, Запорожці, translit=Zaporoz ...

in Ukraine were able to maintain their independence. The Zaporozhians were made up of a broad mix of peoples, including those who had fled from serfdom

Serfdom was the status of many peasants under feudalism, specifically relating to manorialism, and similar systems. It was a condition of debt bondage and indentured servitude with similarities to and differences from slavery, which develop ...

, who as "free Ukrainians" held their own land and were mobilized as part of the Zaporozhian host. The Ukrainian cossacks fought against the Poles, Russians and Ottomans alike, organized into decentralised regiment

A regiment is a military unit. Its role and size varies markedly, depending on the country, service and/or a specialisation.

In Medieval Europe, the term "regiment" denoted any large body of front-line soldiers, recruited or conscripted ...

s (''polks'') and squadrons (''sotnias''). The Zaporozhian Sich

The Zaporozhian Sich ( ua, Запорозька Січ, ; also uk, Вольностi Вiйська Запорозького Низового, ; Free lands of the Zaporozhian Host the Lower) was a semi-autonomous polity and proto-state of Co ...

was itself organized along democratic and egalitarian

Egalitarianism (), or equalitarianism, is a school of thought within political philosophy that builds from the concept of social equality, prioritizing it for all people. Egalitarian doctrines are generally characterized by the idea that all hum ...

lines, where military and civilian officials were all directly elected

Direct election is a system of choosing political officeholders in which the voters directly cast ballots for the persons or political party that they desire to see elected. The method by which the winner or winners of a direct election are cho ...

for one-year terms and subject to instant recall by the assemblies, while its land was distributed equally among the people.

Dedicated to the preservation of "Cossack freedoms", Stenka Razin led the Don Cossacks

Don Cossacks (russian: Донские казаки, Donskie kazaki) or Donians (russian: донцы, dontsy) are Cossacks who settled along the middle and lower Don. Historically, they lived within the former Don Cossack Host (russian: До� ...

in an uprising against the Tsarist autocracy

Tsarist autocracy (russian: царское самодержавие, transcr. ''tsarskoye samoderzhaviye''), also called Tsarism, was a form of autocracy (later absolute monarchy) specific to the Grand Duchy of Moscow and its successor states th ...

in Russia and later Yemelyan Pugachev

Yemelyan Ivanovich Pugachev (russian: Емельян Иванович Пугачёв; c. 1742) was an ataman of the Yaik Cossacks who led a great popular insurrection during the reign of Catherine the Great. Pugachev claimed to be Catherine's ...

led the Ural Cossacks

The Ural Cossack Host was a cossack host formed from the Ural Cossacks – those Eurasian cossacks settled by the Ural River. Their alternative name, Yaik Cossacks, comes from the old name of the river.

They were also known by the names:

*Rus ...

in a peasants' revolt

The Peasants' Revolt, also named Wat Tyler's Rebellion or the Great Rising, was a major uprising across large parts of England in 1381. The revolt had various causes, including the socio-economic and political tensions generated by the Black ...

against serfdom

Serfdom was the status of many peasants under feudalism, specifically relating to manorialism, and similar systems. It was a condition of debt bondage and indentured servitude with similarities to and differences from slavery, which develop ...

, but both of these rebellions were defeated. The Cossack hosts were subsequently dissolved and inducted into the Imperial Russian Army

The Imperial Russian Army (russian: Ру́сская импера́торская а́рмия, tr. ) was the armed land force of the Russian Empire, active from around 1721 to the Russian Revolution of 1917. In the early 1850s, the Russian Ar ...

, in which they became loyal soldiers of the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War. ...

, going on to play a vital role in defeating the Napoleonic invasion of 1812 and later becoming the ''de facto'' police force in Russia. Likewise, the Zaporozhian Sich was broken up and its people were forced into either serfdom or exile, with Ukraine being brought definitively under Russian imperial rule. Nevertheless, the tradition of the "libertarian-minded warrior-peasants" persisted, setting the groundwork for the libertarian communist

Anarcho-communism, also known as anarchist communism, (or, colloquially, ''ancom'' or ''ancomm'') is a political philosophy and anarchist school of thought that advocates communism. It calls for the abolition of private property but retains resp ...

movement in Ukraine.

Rising radicalism

Radicalism spread throughUkraine

Ukraine ( uk, Україна, Ukraïna, ) is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the second-largest European country after Russia, which it borders to the east and northeast. Ukraine covers approximately . Prior to the ongoing Russian inv ...

in the wake of the War of 1812

The War of 1812 (18 June 1812 – 17 February 1815) was fought by the United States of America and its indigenous allies against the United Kingdom and its allies in British North America, with limited participation by Spain in Florida. It bega ...

, as the rise in calls for abolition of the Tsarist autocracy

Tsarist autocracy (russian: царское самодержавие, transcr. ''tsarskoye samoderzhaviye''), also called Tsarism, was a form of autocracy (later absolute monarchy) specific to the Grand Duchy of Moscow and its successor states th ...

and serfdom

Serfdom was the status of many peasants under feudalism, specifically relating to manorialism, and similar systems. It was a condition of debt bondage and indentured servitude with similarities to and differences from slavery, which develop ...

led to the establishment of the Southern Society of the Decembrists

The Southern Society of the Decembrists (russian: Южное общество декабристов) was one of two, along with the Northern Society, main secret revolutionary organizations of the Decembrists. Created in March 1821 on the basi ...

in 1821. Ukrainian Decembrists were more radical than their northern counterparts, calling for the overthrow of the monarchy and its replacement with a revolutionary republic

A revolutionary republic is a form of government whose main tenets are popular sovereignty, rule of law, and representative democracy. It is based in part on the ideas of Whig and Enlightenment thinkers, and was favored by revolutionaries dur ...

. Following the death of Alexander I Alexander I may refer to:

* Alexander I of Macedon, king of Macedon 495–454 BC

* Alexander I of Epirus (370–331 BC), king of Epirus

* Pope Alexander I (died 115), early bishop of Rome

* Pope Alexander I of Alexandria (died 320s), patriarch of ...

, the Southern Society in Kyiv

Kyiv, also spelled Kiev, is the capital and most populous city of Ukraine. It is in north-central Ukraine along the Dnieper, Dnieper River. As of 1 January 2021, its population was 2,962,180, making Kyiv the List of European cities by populat ...

staged a revolt against the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War. ...

, but it was suppressed.

Radicalism was raised further during the Ukrainian national revival, as Brotherhoods began to advocate for Ukrainian autonomy and the replacement of the Empire with a pan-Slavic

Pan-Slavism, a movement which crystallized in the mid-19th century, is the political ideology concerned with the advancement of integrity and unity for the Slavic people. Its main impact occurred in the Balkans, where non-Slavic empires had rule ...

federation

A federation (also known as a federal state) is a political entity characterized by a union of partially self-governing provinces, states, or other regions under a central federal government (federalism). In a federation, the self-governin ...

organized along liberal democratic

Liberal democracy is the combination of a liberal political ideology that operates under an indirect democratic form of government. It is characterized by elections between multiple distinct political parties, a separation of powers into diff ...

lines, with Taras Shevchenko

Taras Hryhorovych Shevchenko ( uk, Тарас Григорович Шевченко , pronounced without the middle name; – ), also known as Kobzar Taras, or simply Kobzar (a kobzar is a bard in Ukrainian culture), was a Ukraine, Ukrainian p ...

even displaying revolutionary sentiments. The Ukrainian intellectual '' hromadas'', inspired by Russian populism, began to engage with the peasantry - leading to the rise of agrarian socialist

Agrarian socialism is a political ideology that promotes “the equal distribution of landed resources among collectivized peasant villages” This socialist system places agriculture at the center of the economy instead of the industrialization ...

tendencies in Ukrainian radical circles.

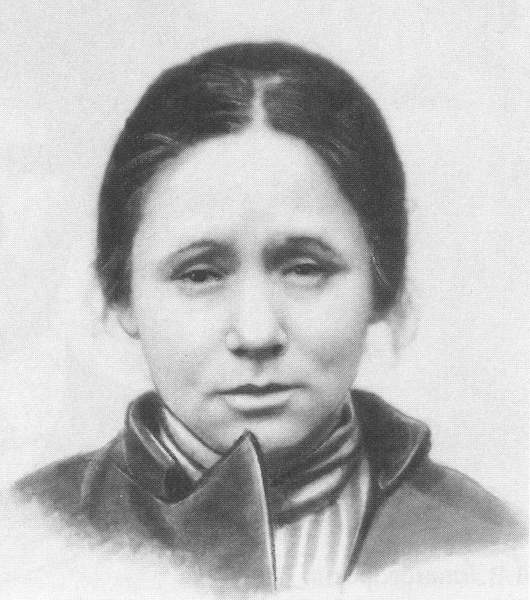

The most prominent of the ''hromadas'' was the one in Kyiv, founded in 1859 by populist students of the Lavrovist tendency, who emphasised the education of the peasantry and rejected revolutionary agitation. It was banned by 1863 but renewed its educational activities in 1869, spearheaded by a new generation of students led by

The most prominent of the ''hromadas'' was the one in Kyiv, founded in 1859 by populist students of the Lavrovist tendency, who emphasised the education of the peasantry and rejected revolutionary agitation. It was banned by 1863 but renewed its educational activities in 1869, spearheaded by a new generation of students led by Volodymyr Antonovych

Volodymyr Antonovych ( ukr, Володимир Боніфатійович Антонович, tr. ''Volodymyr Bonifatijovych Antonovych''; pl, Włodzimierz Antonowicz; russian: Влади́мир Бонифа́тьевич Антоно́вич, ...

, Pavlo Chubynsky

Pavlo Platonovych Chubynsky ( uk, Павло Платонович Чубинський; 1839 – January 26, 1884) was a Ukrainian poet and ethnographer whose poem ''Shche ne vmerla Ukraina'' (Ukraine Has Not Yet Perished) was set to music and ad ...

and Mykhailo Drahomanov

Mykhailo Petrovych Drahomanov ( ukr, Михайло Петрович Драгоманов; 18 September 1841 – 2 July 1895) was a Ukrainian intellectual and public figure. As an academic, Drahomanov was an economist, historian, philosopher, and ...

. Continuing the democratic-federalist

The term ''federalist'' describes several political beliefs around the world. It may also refer to the concept of parties, whose members or supporters called themselves ''Federalists''.

History Europe federation

In Europe, proponents of de ...

tradition from the Decembrists and the Brotherhoods, Mykhailo Drahomanov blended together elements from liberal democracy

Liberal democracy is the combination of a liberal political ideology that operates under an indirect democratic form of government. It is characterized by elections between multiple distinct political parties, a separation of powers into diff ...

, agrarian socialism

Agrarian socialism is a political ideology that promotes “the equal distribution of landed resources among collectivized peasant villages” This socialist system places agriculture at the center of the economy instead of the industrialization ...

and Ukrainian nationalism

Ukrainian nationalism refers to the promotion of the unity of Ukrainians as a people and it also refers to the promotion of the identity of Ukraine as a nation state. The nation building that arose as nationalism grew following the French Revol ...

, envisioning the final goal of the democratic-federalist movement to be the achievement of anarchy

Anarchy is a society without a government. It may also refer to a society or group of people that entirely rejects a set hierarchy. ''Anarchy'' was first used in English in 1539, meaning "an absence of government". Pierre-Joseph Proudhon adopted ...

, as inspired by the works

Works may refer to:

People

* Caddy Works (1896–1982), American college sports coach

* Samuel Works (c. 1781–1868), New York politician

Albums

* '' ''Works'' (Pink Floyd album)'', a Pink Floyd album from 1983

* ''Works'', a Gary Burton album ...

of Pierre-Joseph Proudhon

Pierre-Joseph Proudhon (, , ; 15 January 1809, Besançon – 19 January 1865, Paris) was a French socialist,Landauer, Carl; Landauer, Hilde Stein; Valkenier, Elizabeth Kridl (1979) 959 "The Three Anticapitalistic Movements". ''European Socia ...

. Having coined the slogan "Cosmopolitanism

Cosmopolitanism is the idea that all human beings are members of a single community. Its adherents are known as cosmopolitan or cosmopolite. Cosmopolitanism is both prescriptive and aspirational, believing humans can and should be " world citizens ...

in the ideas and the ends, nationality

Nationality is a legal identification of a person in international law, establishing the person as a subject, a ''national'', of a sovereign state. It affords the state jurisdiction over the person and affords the person the protection of the ...

in the ground and the forms," Drahomanov rejected separatism

Separatism is the advocacy of cultural, ethnic, tribal, religious, racial, governmental or gender separation from the larger group. As with secession, separatism conventionally refers to full political separation. Groups simply seeking greate ...

due to his philosophical anarchist

Philosophical anarchism is an anarchist school of thought which focuses on intellectual criticism of authority, especially political power, and the legitimacy of governments. The American anarchist and socialist Benjamin Tucker coined the term '' ...

opposition to nation state

A nation state is a political unit where the state and nation are congruent. It is a more precise concept than "country", since a country does not need to have a predominant ethnic group.

A nation, in the sense of a common ethnicity, may inc ...

s. Viewing national liberation as "inseparable from social emancipation", he instead encouraged for the ''Hromada'' to concentrate on building a bottom-up form of democracy of small communities organized on a federative basis.

In 1874, the Narodniks' "

In 1874, the Narodniks' "Going to the People

Going to the People (russian: Хождение в народ, ) was a populist movement in the Russian Empire. It was largely inspired by the work of Russian theorists such as Mikhail Bakunin and Pyotr Lavrov, who advocated that groups of dedicat ...

" campaign culminated in a number of Ukrainian revolutionary anarchists (''buntars''), led by Yakov Stefanovich

Yakov Vasilevich Stefanovich ( Russian: Яков Васильевич Стефанович) (10 December (28 November old style) 1854 –14 April 1915) was a Ukrainian narodnik revolutionary.

Stefanovich led an unsuccessful attempt to incite a pea ...

, organizing a peasant revolt in Chyhyryn

Chyhyryn ( uk, Чигирин, ) is a city and historic site located in Cherkasy Raion of Cherkasy Oblast of central Ukraine. From 1648 to 1669 the city was a Hetman residence. After a forced relocation of the Ruthenian Orthodox metropolitan see ...

, before being suppressed by Russian authorities. Alexander II subsequently issued the ''Ems Ukaz

The Ems Ukaz or Ems Ukase (russian: Эмский указ, Emskiy ukaz; uk, Емський указ, Ems’kyy ukaz), was a secret decree (''ukaz'') of Emperor Alexander II of Russia issued on May 18, 1876, banning the use of the Ukrainian lang ...

'' which banned the use of the Ukrainian language

Ukrainian ( uk, украї́нська мо́ва, translit=ukrainska mova, label=native name, ) is an East Slavic language of the Indo-European language family. It is the native language of about 40 million people and the official state langu ...

, resulting in the repression of the ''hromadas'' and Drahomanov's flight into exile in Geneva

Geneva ( ; french: Genève ) frp, Genèva ; german: link=no, Genf ; it, Ginevra ; rm, Genevra is the List of cities in Switzerland, second-most populous city in Switzerland (after Zürich) and the most populous city of Romandy, the French-speaki ...

, where he established the Geneva Circle, the first Ukrainian socialist organisation. Drahomanov's socialist tendencies brought him into conflict with more moderate members of the ''Hromada'', as well as the "chauvinist

Chauvinism is the unreasonable belief in the superiority or dominance of one's own group or people, who are seen as strong and virtuous, while others are considered weak, unworthy, or inferior. It can be described as a form of extreme patriotis ...

" and "dictatorial

A dictator is a political leader who possesses absolute power. A dictatorship is a state ruled by one dictator or by a small clique. The word originated as the title of a Roman dictator elected by the Roman Senate to rule the republic in times ...

" Russian revolutionaries, leaving him isolated from many of his contemporaries by 1886. In Galicia, which Drahomanov had placed at the center of the Ukrainian national struggle due to its constitutionalism

Constitutionalism is "a compound of ideas, attitudes, and patterns of behavior elaborating the principle that the authority of government derives from and is limited by a body of fundamental law".

Political organizations are constitutional ...

, Drahomanov's disciple Ivan Franko

Ivan Yakovych Franko (Ukrainian: Іван Якович Франко, pronounced ˈwɑn ˈjɑkowɪtʃ frɐnˈkɔ 27 August 1856 – 28 May 1916) was a Ukrainian poet, writer, social and literary critic, journalist, interpreter, economist, ...

found himself persecuted by the Austrian authorities and ostracised by local religious conservatives

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization ...

, due to his staunch anti-clericalism

Anti-clericalism is opposition to religious authority, typically in social or political matters. Historical anti-clericalism has mainly been opposed to the influence of Roman Catholicism. Anti-clericalism is related to secularism, which seeks to ...

.

Nonetheless, in 1890 Franko was able to found the Ukrainian Radical Party

The Ukrainian Radical Party, (URP), ( uk, Українська радикальна партія, УPП, ''Ukrajinśka Radykaľna Partija'') founded in October 1890 as Ruthenian-Ukrainian Radical Party and based on the radical movement in wester ...

(URP), which engaged in a number of activities including the convocation of popular assemblies

A popular assembly (or people's assembly) is a gathering called to address issues of importance to participants. Assemblies tend to be freely open to participation and operate by direct democracy. Some assemblies are of people from a location ...

, the establishment of cooperatives

A cooperative (also known as co-operative, co-op, or coop) is "an autonomous association of persons united voluntarily to meet their common economic, social and cultural needs and aspirations through a jointly owned and democratically-control ...

and the education of the peasantry. In 1895, members of the URP were elected to the Galician Diet and the Austrian parliament

The Austrian Parliament (german: Österreichisches Parlament) is the bicameral federal legislature of the Austrian Republic. It consists of two chambers – the National Council and the Federal Council. In specific cases, both houses convene ...

, by which point its party congresses were beginning to call for Ukrainian independence and endorsed a number of strikes by agricultural workers. Drahomanov's death that same year accelerated a split in the organization, between orthodox radicals that stayed loyal to Drahomanov's platform, younger social democrats

Social democracy is a political, social, and economic philosophy within socialism that supports political and economic democracy. As a policy regime, it is described by academics as advocating economic and social interventions to promote so ...

that had gravitated towards Marxism

Marxism is a Left-wing politics, left-wing to Far-left politics, far-left method of socioeconomic analysis that uses a Materialism, materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to understand S ...

and nationalists

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a group of people), Smith, Anthony. ''Nationalism: The ...

who were no longer comfortable with the party's socialist line. By losing the latter two factions, the URP took on a definitively agrarian socialist platform and grew to become the second-largest of the Ukrainian political parties in Galicia.

1905 Revolution

Ukrainian Jews

The history of the Jews in Ukraine dates back over a thousand years; Jewish communities have existed in the territory of Ukraine from the time of the Kievan Rus' (late 9th to mid-13th century). Some of the most important Jewish religious and ...

in the Pale of Settlement

The Pale of Settlement (russian: Черта́ осе́длости, '; yi, דער תּחום-המושבֿ, '; he, תְּחוּם הַמּוֹשָב, ') was a western region of the Russian Empire with varying borders that existed from 1791 to 19 ...

had been extended a number of rights during the reign of Alexander II, but following his assassination

Assassination is the murder of a prominent or important person, such as a head of state, head of government, politician, world leader, member of a royal family or CEO. The murder of a celebrity, activist, or artist, though they may not have ...

by People's Will

Narodnaya Volya ( rus, Наро́дная во́ля, p=nɐˈrodnəjə ˈvolʲə, t=People's Will) was a late 19th-century revolutionary political organization in the Russian Empire which conducted assassinations of government officials in an att ...

, a wave of pogroms

A pogrom () is a violent riot incited with the aim of massacring or expelling an ethnic or religious group, particularly Jews. The term entered the English language from Russian to describe 19th- and 20th-century attacks on Jews in the Russian ...

broke out and the new government of Alexander III implemented the May Laws

Temporary regulations regarding the Jews (also known as May Laws) were proposed by the minister of internal affairs Nikolay Pavlovich Ignatyev and enacted on 15 May (3 May O.S.), 1882, by Tsar Alexander III of Russia. Originally, regulations of ...

, which persecuted Jews living in the Pale. In 1903, a strike in Odesa

Odesa (also spelled Odessa) is the third most populous city and municipality in Ukraine and a major seaport and transport hub located in the south-west of the country, on the northwestern shore of the Black Sea. The city is also the administrative ...

rapidly escalated into a nationwide Ukrainian general strike

A general strike refers to a strike action in which participants cease all economic activity, such as working, to strengthen the bargaining position of a trade union or achieve a common social or political goal. They are organised by large co ...

, with the heavy industry centers of Kyiv

Kyiv, also spelled Kiev, is the capital and most populous city of Ukraine. It is in north-central Ukraine along the Dnieper, Dnieper River. As of 1 January 2021, its population was 2,962,180, making Kyiv the List of European cities by populat ...

, Kharkiv

Kharkiv ( uk, wikt:Харків, Ха́рків, ), also known as Kharkov (russian: Харькoв, ), is the second-largest List of cities in Ukraine, city and List of hromadas of Ukraine, municipality in Ukraine.Mykolaiv

Mykolaiv ( uk, Миколаїв, ) is a List of cities in Ukraine, city and List of hromadas of Ukraine, municipality in Southern Ukraine, the Administrative centre, administrative center of the Mykolaiv Oblast. Mykolaiv city, which provides U ...

and Katerynoslav

Dnipro, previously called Dnipropetrovsk from 1926 until May 2016, is Ukraine's fourth-largest city, with about one million inhabitants. It is located in the eastern part of Ukraine, southeast of the Ukrainian capital Kyiv on the Dnieper Rive ...

all experiencing mass industrial action. The Minister of Interior

An interior minister (sometimes called a minister of internal affairs or minister of home affairs) is a Cabinet (government), cabinet official position that is responsible for internal affairs, such as public security, civil registration and iden ...

Vyacheslav von Plehve

Vyacheslav Konstantinovich von Plehve ( rus, Вячесла́в (Wenzel (Славик)) из Плевны Константи́нович фон Пле́ве, p=vʲɪtɕɪˈslaf fɐn ˈplʲevʲɪ; – ) served as a director of Imperial Russ ...

responded to the strike wave by propagating a number of anti-semitic

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who holds such positions is called an antisemite. Antisemitism is considered to be a form of racism.

Antis ...

and anti-communist

Anti-communism is Political movement, political and Ideology, ideological opposition to communism. Organized anti-communism developed after the 1917 October Revolution in the Russian Empire, and it reached global dimensions during the Cold War, w ...

conspiracy theories

A conspiracy theory is an explanation for an event or situation that invokes a conspiracy by sinister and powerful groups, often political in motivation, when other explanations are more probable.Additional sources:

*

*

*

* The term has a nega ...

about the labour movement, which resulted in another wave of pogroms

A pogrom () is a violent riot incited with the aim of massacring or expelling an ethnic or religious group, particularly Jews. The term entered the English language from Russian to describe 19th- and 20th-century attacks on Jews in the Russian ...

breaking out in Ukraine. The living conditions of Pale nourished the growth of the Ukrainian anarchist movement, which grew particularly strong in Jewish towns, where workers' circles began to educate themselves on a number of radical ideas. Dissatisfied with the existing socialist parties, activists of the General Jewish Labour Bund, Socialist Revolutionary Party

The Socialist Revolutionary Party, or the Party of Socialist-Revolutionaries (the SRs, , or Esers, russian: эсеры, translit=esery, label=none; russian: Партия социалистов-революционеров, ), was a major politi ...

and Revolutionary Ukrainian Party

The Revolutionary Ukrainian Party ( uk, Революційна Партія України) was a Ukrainian political party in the Russian Empire founded on 11 February 1900 by the Kharkiv student secret society Hromada.

History

The rise of the ...

all deserted party politics for anarchism. The Bread and Freedom group in London

London is the capital and largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary down to the North Sea, and has been a majo ...

organized the distribution of anarchist literature, including the Yiddish language

Yiddish (, or , ''yidish'' or ''idish'', , ; , ''Yidish-Taytsh'', ) is a West Germanic language historically spoken by Ashkenazi Jews. It originated during the 9th century in Central Europe, providing the nascent Ashkenazi community with a ver ...

journals ''Arbeter Fraynd

The Worker's Friend Group was a Jewish anarchist group active in London's East End in the early 1900s. Associated with the Yiddish-language anarchist newspaper ''Arbeter Fraint'' ("Worker's Friend") and centered around the German emigre anarchi ...

'' and '' Germinal'', throughout much of the Pale, reaching as far as the anarchist groups in Odesa and Nizhyn

Nizhyn ( uk, Ні́жин, Nizhyn, ) is a city located in Chernihiv Oblast of northern Ukraine along the Oster River. The city is located north-east of the national capital Kyiv. Nizhyn serves as the administrative center of Nizhyn Raion. It ...

.

Popular discontent with the Tsarist autocracy

Tsarist autocracy (russian: царское самодержавие, transcr. ''tsarskoye samoderzhaviye''), also called Tsarism, was a form of autocracy (later absolute monarchy) specific to the Grand Duchy of Moscow and its successor states th ...

eventually culminated in the 1905 Revolution, during which much of the country rebelled against the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War. ...

, with a general strike

A general strike refers to a strike action in which participants cease all economic activity, such as working, to strengthen the bargaining position of a trade union or achieve a common social or political goal. They are organised by large co ...

in October successfully securing civil liberties

Civil liberties are guarantees and freedoms that governments commit not to abridge, either by constitution, legislation, or judicial interpretation, without due process. Though the scope of the term differs between countries, civil liberties may ...

and the constitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organisation or other type of Legal entity, entity and commonly determine how that entity is to be governed.

When ...

of the State Duma

The State Duma (russian: Госуда́рственная ду́ма, r=Gosudárstvennaja dúma), commonly abbreviated in Russian as Gosduma ( rus, Госду́ма), is the lower house of the Federal Assembly of Russia, while the upper house ...

. But workers and peasants throughout the country, having not had any of their economic demands met, continued to openly revolt against the government. During the suppression of the revolution in December, workers' uprisings broke out in Odesa, Kharkiv and Katerynoslav, but they were unsuccessful and the revolution was brought to an end.

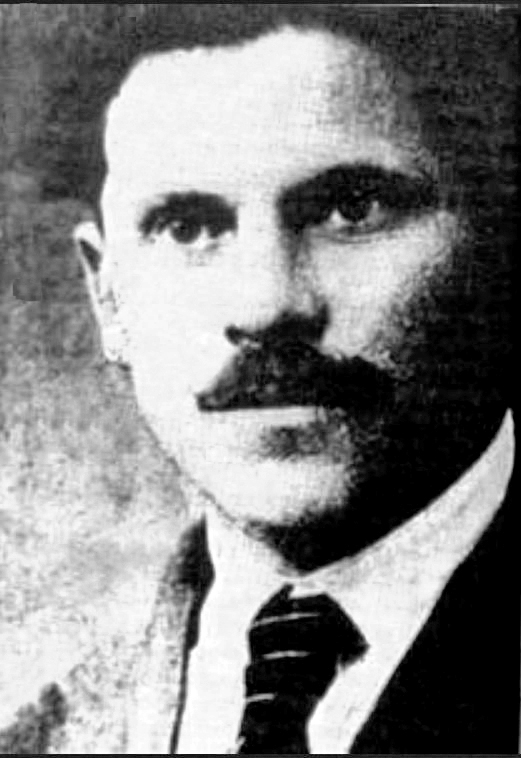

Juda Grossman described the rise of anarchist groups in the wake of the revolution as though they "sprang up like mushrooms after a rain". Jewish anarchist groups sprouted up throughout many of the small towns in the Pale, while in the cities of Ukraine, the anarchist movement that had first appeared in Odesa and Katerynoslav had spread to Kyiv and Kharkiv. In

Juda Grossman described the rise of anarchist groups in the wake of the revolution as though they "sprang up like mushrooms after a rain". Jewish anarchist groups sprouted up throughout many of the small towns in the Pale, while in the cities of Ukraine, the anarchist movement that had first appeared in Odesa and Katerynoslav had spread to Kyiv and Kharkiv. In Huliaipole

Huliaipole ( uk, Гуляйполе ; ) is a city in Polohy Raion, Zaporizhzhia Oblast, Ukraine. It is known as the birthplace of Ukrainian anarchist revolutionary Nestor Makhno. In 2021, it had a population of Huliaipole was attacked by Russian ...

, the Union of Poor Peasants

The Union of Poor Peasants ( uk, Спілка бідних хліборобів), also known as the Peasant Group of Anarcho-Communists or the Huliaipole Anarchist Group, was an underground anarchist organization, operating in the years 1905–190 ...

was formed to carry out expropriations

Eminent domain (United States, Philippines), land acquisition (India, Malaysia, Singapore), compulsory purchase/acquisition (Australia, New Zealand, Ireland, United Kingdom), resumption (Hong Kong, Uganda), resumption/compulsory acquisition (Austr ...

against the rich, with a young Nestor Makhno

Nestor Ivanovych Makhno, The surname "Makhno" ( uk, Махно́) was itself a corruption of Nestor's father's surname "Mikhnenko" ( uk, Міхненко). ( 1888 – 25 July 1934), also known as Bat'ko Makhno ("Father Makhno"),; According to ...

joining the group and later being arrested and imprisoned for killing a police officer. The Black Banner, a terrorist organization inspired by the insurrectionary anarchism

Insurrectionary anarchism is a revolutionary theory and tendency within the anarchist movement that emphasizes insurrection as a revolutionary practice. It is critical of formal organizations such as labor unions and federations that are based o ...

of Mikhail Bakunin

Mikhail Alexandrovich Bakunin (; 1814–1876) was a Russian revolutionary anarchist, socialist and founder of collectivist anarchism. He is considered among the most influential figures of anarchism and a major founder of the revolutionary ...

, grew to include a large membership of Russians, Ukrainians and Jews. In Katerynoslav, Odesa and Sevastopol

Sevastopol (; uk, Севасто́поль, Sevastópolʹ, ; gkm, Σεβαστούπολις, Sevastoúpolis, ; crh, Акъя́р, Aqyár, ), sometimes written Sebastopol, is the largest city in Crimea, and a major port on the Black Sea ...

, the Black banner organized a number of detachments that carried out bombings on buildings, murdered and robbed rich people, and fought with the police in the streets. Even the merchant vessels that docked in Odesa's port became the target of expropriations. At his trial, a member of the Odesa branch of the Black Banner explained their method of " motiveless terror":

Although the terrorists within the Black Banner had been energised by their attacks in Odesa, a dissenting ''Communard'' group had also emerged that called for the organization of a mass uprising, rather than individual acts of propaganda of the deed

Propaganda of the deed (or propaganda by the deed, from the French ) is specific political direct action meant to be exemplary to others and serve as a catalyst for revolution.

It is primarily associated with acts of violence perpetrated by pro ...

. Anarchists in major cities began to shift their activities towards the distribution of propaganda, with the Kyiv Group of Anarchist-Communists pursuing a more moderate course, inspired by the works of Peter Kropotkin

Pyotr Alexeyevich Kropotkin (; russian: link=no, Пётр Алексе́евич Кропо́ткин ; 9 December 1842 – 8 February 1921) was a Russian anarchist, socialist, revolutionary, historian, scientist, philosopher, and activis ...

. Inspired by their Narodnik predecessors, anarcho-communists from Odesa, Katerynoslav, Kyiv and Chernihiv " went to the people", distributing radical propaganda among the peasantry. Their leaflet ''How the Peasants Succeed Without Authority'' depicted a communal village that lived without government and distributed its resources " from each according to their ability, to each according to their needs". Members of Bread and Freedom denounced the "robber bands" of Odesa, comparing them to the Italian mafia

Organized crime in Italy and its criminal organizations have been prevalent in Italy, especially Southern Italy, for centuries and have affected the social and economic life of many Italian regions since at least the 19th century.

There are six ...

and claiming that their terror campaign demoralized and discredited the movement. Nevertheless, the anarcho-communists continued to advocate for propaganda of the deed, even approving "defensive terror" against the police and Black Hundreds

The Black Hundred (russian: Чёрная сотня, translit=Chornaya sotnya), also known as the black-hundredists (russian: черносотенцы; chernosotentsy), was a reactionary, monarchist and ultra-nationalist movement in Russia in t ...

, with a report from Odesa printed in ''Bread and Freedom'' declaring that "only the enemies of the people can be enemies of terror!"

Alongside anarcho-communism

Anarcho-communism, also known as anarchist communism, (or, colloquially, ''ancom'' or ''ancomm'') is a political philosophy and anarchist school of thought that advocates communism. It calls for the abolition of private property but retains res ...

, Ukrainian cities also saw the emergence of other anarchist tendencies, such as anarcho-syndicalism

Anarcho-syndicalism is a political philosophy and anarchist school of thought that views revolutionary industrial unionism or syndicalism as a method for workers in capitalist society to gain control of an economy and thus control influence in b ...

in Odesa and individualist anarchism

Individualist anarchism is the branch of anarchism that emphasizes the individual and their Will (philosophy), will over external determinants such as groups, society, traditions and ideological systems."What do I mean by individualism? I mean ...

in Kyiv. The anarcho-syndicalists of Odesa declared themselves in opposition to the terrorist tactics of the time, having experienced a number of them first-hand, instead advocating for the construction of labor union

A trade union (labor union in American English), often simply referred to as a union, is an organization of workers intent on "maintaining or improving the conditions of their employment", ch. I such as attaining better wages and benefits ( ...

s capable of radical industrial action

Industrial action (British English) or job action (American English) is a temporary show of dissatisfaction by employees—especially a strike action, strike or slowdown or working to rule—to protest against bad working conditions or low pay a ...

. However, the Odesa Anarcho-Syndicalists soon found themselves establishing their own "battle detachments" to carry out expropriations, using the stolen money to buy more weapons and fund the printing and distribution of their literature, even going on to establish a bomb laboratory. The anarcho-syndicalist leader Daniil Novomirskii justified this use of terrorism as having acted to benefit the movement "as a whole", which he distinguished from the unplanned "motiveless terror" of the '' Nechayevshchina''. The Odesa Anarcho-Syndicalists had adopted the French General Confederation of Labour (CGT) as a model for anarcho-syndicalism in Ukraine, centring trade unions

A trade union (labor union in American English), often simply referred to as a union, is an organization of workers intent on "maintaining or improving the conditions of their employment", ch. I such as attaining better wages and Employee ben ...

as the means for class struggle, winning short-term gains while building towards a social revolution, in which the unions could themselves seize the means of production

The means of production is a term which describes land, labor and capital that can be used to produce products (such as goods or services); however, the term can also refer to anything that is used to produce products. It can also be used as an ...

. Like their western counterparts, the Odesa syndicalists rejected vanguardism

Vanguardism in the context of Leninist revolutionary struggle, relates to a strategy whereby the most class-conscious and politically "advanced" sections of the proletariat or working class, described as the revolutionary vanguard, form organi ...

and tasked themselves with combatting socialist entryism

Entryism (also called entrism, enterism, or infiltration) is a political strategy in which an organisation or state encourages its members or supporters to join another, usually larger, organization in an attempt to expand influence and expand the ...

in the unions, going on to form the Revolutionary All-Russian Union of Labor as their own version of the industrial union

Industrial unionism is a trade union organizing method through which all workers in the same industry are organized into the same union, regardless of skill or trade, thus giving workers in one industry, or in all industries, more leverage in ...

. The Union quickly spread throughout Ukraine, at one point claiming 5,000 members, creating a union presence particularly among the factory and dock workers of Odesa and the bakers and tailors of Katerynoslav. On the rise of the Ukrainian anarcho-syndicalist movement, Juda Grossman remarked: "I am convinced that God, if he existed, must be a syndicalist—otherwise Novomirskii would not have enjoyed such great success."

The

The anti-intellectualism

Anti-intellectualism is hostility to and mistrust of intellect, intellectuals, and intellectualism, commonly expressed as deprecation of education and philosophy and the dismissal of art, literature, and science as impractical, politically ...

of the Polish revolutionary Jan Wacław Machajski, inspired by Bakunin's insurrectionary anarchism, also made an impression among Ukrainian anarchists, with the Black Banner members Olga Taratuta and Vladimir Striga organizing alongside Makhaevists in a secret society known as the Intransigents. Even the Odesa Anarcho-Syndicalists were influenced by Machajski's anti-intellectualism, with their denunciations of social democracy being rooted in their opposition to the creation of a new intellectual elite, declaring that "the liberation of the workers must be the task of the working class itself".

Despite the best efforts of the syndicalists, their extremist counterparts attracted far more attention from the press and the government. Pyotr Stolypin

Pyotr Arkadyevich Stolypin ( rus, Пётр Арка́дьевич Столы́пин, p=pʲɵtr ɐrˈkadʲjɪvʲɪtɕ stɐˈlɨpʲɪn; – ) was a Russian politician and statesman. He served as the third prime minister and the interior minist ...

instituted pacification measures against the terrorist movement, placing the Russian Empire under a state of emergency

A state of emergency is a situation in which a government is empowered to be able to put through policies that it would normally not be permitted to do, for the safety and protection of its citizens. A government can declare such a state du ...

and unleashing a wave of punishment against the Black Banner and other radical organisations, with a number of militants committing suicide after their capture. The concept of martyrdom

A martyr (, ''mártys'', "witness", or , ''marturia'', stem , ''martyr-'') is someone who suffers persecution and death for advocating, renouncing, or refusing to renounce or advocate, a religious belief or other cause as demanded by an external ...

entered the anarchist zeitgeist as hundreds of young anarchists were executed in the repression, including the Ukrainian individualist Matrena Prisiazhniuk, who was sentenced to death for raiding a sugar factory, murdering a priest and attempting to murder a police officer. Following her sentence, she remarked:

Contempt of court

Contempt of court, often referred to simply as "contempt", is the crime of being disobedient to or disrespectful toward a court of law and its officers in the form of behavior that opposes or defies the authority, justice, and dignity of the cour ...

was common among anarchist defendants, with one terrorist from Odesa, Lev Aleshker, attacking the judges: "You yourselves should be sitting on the bench of the accused! ..Down with all of you! Villainous hangmen! Long live anarchy!" In Aleshker's last testament, he predicted the coming of an anarchist future:

Five young anarchists were brought to trial for the bombing of the Cafe Libman in Odesa, all of them being sentenced to the death penalty. One of the defendants, Moisei Mets, denied any criminal guilt while also confessing to the bombing, declaring to the court that they demanded nothing less than "the final annihilation of eternal slavery and exploitation". Before his execution, Mets declared: "Death and destruction to the whole bourgeois order! Hail the revolutionary class struggle of the oppressed! Long live anarchism and communism!"

In Odesa alone, 167 anarchists were tried in the wake of the revolution, including 12 anarcho-syndicalists, 94 members of the Black Banner, 51 sympathisers, 5 members of the SR Combat Organization and 5 members of the Anarchist Red Cross. They were mostly young people of mixed Russian, Ukrainian and Jewish backgrounds, of whom 28 received the death penalty and 5 escaped prison. One of those that escaped was Olga Taratuta, who fled to Geneva

Geneva ( ; french: Genève ) frp, Genèva ; german: link=no, Genf ; it, Ginevra ; rm, Genevra is the List of cities in Switzerland, second-most populous city in Switzerland (after Zürich) and the most populous city of Romandy, the French-speaki ...

and joined the ''buntars'' before returning to Katerynoslav and joining an anarcho-communist "battle detachment", which saw her arrested again and this time sentenced to hard labor. Vladimir Ushakov had also fled capture in Saint Petersburg

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

, hiding out in Lviv

Lviv ( uk, Львів) is the largest city in western Ukraine, and the seventh-largest in Ukraine, with a population of . It serves as the administrative centre of Lviv Oblast and Lviv Raion, and is one of the main cultural centres of Ukraine ...

before joining the Katerynoslav battle detachment and going on to expropriate a bank in Yalta

Yalta (: Я́лта) is a resort city on the south coast of the Crimean Peninsula surrounded by the Black Sea. It serves as the administrative center of Yalta Municipality, one of the regions within Crimea. Yalta, along with the rest of Crimea ...

. He was caught in the act and taken to prison in Sevastopol

Sevastopol (; uk, Севасто́поль, Sevastópolʹ, ; gkm, Σεβαστούπολις, Sevastoúpolis, ; crh, Акъя́р, Aqyár, ), sometimes written Sebastopol, is the largest city in Crimea, and a major port on the Black Sea ...

, where he committed suicide during a failed escape attempt. The leaders of the anarcho-syndicalist movement in Odesa and the anarcho-communist movement in Kyiv were all sentenced to long terms of hard labor.

The mass imprisonment of anarchist agitators affected each of them differently, with some taking the time to educate themselves and write of their experiences. In the Butyrka prison

Butyrskaya prison ( rus, Бутырская тюрьма, r= Butýrskaya tyurmá), usually known simply as Butyrka ( rus, Бутырка, p=bʊˈtɨrkə), is a prison in the Tverskoy District of central Moscow, Russia. In Imperial Russia it ...

, Nestor Makhno

Nestor Ivanovych Makhno, The surname "Makhno" ( uk, Махно́) was itself a corruption of Nestor's father's surname "Mikhnenko" ( uk, Міхненко). ( 1888 – 25 July 1934), also known as Bat'ko Makhno ("Father Makhno"),; According to ...

met Peter Arshinov

Peter Andreyevich Arshinov (russian: Пётр Андре́евич Арши́нов; 1887–1937), was a Russian anarchist revolutionary and intellectual who chronicled the history of the Makhnovshchina.

Initially a Bolshevik, during the 190 ...

, who educated the young peasant on the anarcho-communist theories of Bakunin and Kropotkin, up until their release following the February Revolution

The February Revolution ( rus, Февра́льская револю́ция, r=Fevral'skaya revolyutsiya, p=fʲɪvˈralʲskəjə rʲɪvɐˈlʲutsɨjə), known in Soviet historiography as the February Bourgeois Democratic Revolution and somet ...

. Makhno subsequently returned to Ukraine, where he began organizing an agricultural workers' union and was later elected chairman of the Huliaipole Soviet, from which he ordered the armed expropriation of land by the peasantry.

During World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, the URP took part in the establishment of the Ukrainian Sich Riflemen

Legion of Ukrainian Sich Riflemen (german: Ukrainische Sitschower Schützen; uk, Українські cічові стрільці (УСС), translit=Ukraïnski sichovi stril’tsi (USS)) was a Ukrainian unit within the Austro-Hungarian Army d ...

and, following the war, collaborated in the constitution of the West Ukrainian People's Republic

The West Ukrainian People's Republic (WUPR) or West Ukrainian National Republic (WUNR), known for part of its existence as the Western Oblast of the Ukrainian People's Republic, was a short-lived polity that controlled most of Eastern Gali ...

, with a number of its members subsequently joining the Central Council of the Ukrainian People's Republic

The Ukrainian People's Republic (UPR), or Ukrainian National Republic (UNR), was a country in Eastern Europe that existed between 1917 and 1920. It was declared following the February Revolution in Russia by the First Universal. In March 1 ...

. The federalist orientation of the Central Council was inspired in part by Drahomanov platform, and Drahomanov's influence further inspired the Socialist-Federalists and the Socialist-Revolutionaries

The Socialist Revolutionary Party, or the Party of Socialist-Revolutionaries (the SRs, , or Esers, russian: эсеры, translit=esery, label=none; russian: Партия социалистов-революционеров, ), was a major politi ...

.

Makhnovist Revolution

The outbreak of the

The outbreak of the February Revolution

The February Revolution ( rus, Февра́льская револю́ция, r=Fevral'skaya revolyutsiya, p=fʲɪvˈralʲskəjə rʲɪvɐˈlʲutsɨjə), known in Soviet historiography as the February Bourgeois Democratic Revolution and somet ...

brought with it a resurgence in anarchist activity in Ukraine. Within the month, anarcho-syndicalist

Anarcho-syndicalism is a political philosophy and anarchist school of thought that views revolutionary industrial unionism or syndicalism as a method for workers in capitalist society to gain control of an economy and thus control influence i ...

circles had been organized in the factories of Ukraine's largest industrial cities and miners in Donbas

The Donbas or Donbass (, ; uk, Донба́с ; russian: Донба́сс ) is a historical, cultural, and economic region in eastern Ukraine. Parts of the Donbas are controlled by Russian separatist groups as a result of the Russo-Ukrai ...

had adopted the preamble to the Industrial Workers of the World

The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), members of which are commonly termed "Wobblies", is an international labor union that was founded in Chicago in 1905. The origin of the nickname "Wobblies" is uncertain. IWW ideology combines genera ...

's constitution. In May 1917, the adoption of workers' control

Workers' control is participation in the management of factories and other commercial enterprises by the people who work there. It has been variously advocated by anarchists, socialists, communists, social democrats, distributists and Christ ...

as Bolshevik policy was welcomed by many Ukrainian anarcho-syndicalists, with one proclaiming that "since the time of the revolution, the olshevikshave decisively broken with Social Democracy

Social democracy is a Political philosophy, political, Social philosophy, social, and economic philosophy within socialism that supports Democracy, political and economic democracy. As a policy regime, it is described by academics as advocati ...

, and have been endeavoring to apply Anarcho-syndicalist methods of struggle." By this time, anarcho-syndicalists in Donbas had begun to reject traditional trade union

A trade union (labor union in American English), often simply referred to as a union, is an organization of workers intent on "maintaining or improving the conditions of their employment", ch. I such as attaining better wages and benefits ( ...

s in favor of the newly established factory committee Factory committees (russian: script=Latn, zavodskoy komitet, , ), , , ) were workers' councils representing factory workers in the history of Russia and Soviet Union that accomplished workers' control in various forms. (In Russian language, the ter ...

s, which they considered to be more in line with revolutionary syndicalism.

world revolution

World revolution is the Marxist concept of overthrowing capitalism in all countries through the conscious revolutionary action of the organized working class. For theorists, these revolutions will not necessarily occur simultaneously, but whe ...

. They also established an "Anarchist Information Bureau" to organize a national conference and gauge the movement's strength throughout the country. It was around this time that the Ukrainian revolutionary anarchist Nestor Makhno

Nestor Ivanovych Makhno, The surname "Makhno" ( uk, Махно́) was itself a corruption of Nestor's father's surname "Mikhnenko" ( uk, Міхненко). ( 1888 – 25 July 1934), also known as Bat'ko Makhno ("Father Makhno"),; According to ...

returned to his native Huliaipole

Huliaipole ( uk, Гуляйполе ; ) is a city in Polohy Raion, Zaporizhzhia Oblast, Ukraine. It is known as the birthplace of Ukrainian anarchist revolutionary Nestor Makhno. In 2021, it had a population of Huliaipole was attacked by Russian ...

, where he became involved as a union organizer among the local peasants. By August 1917, Makhno had been elected as the Chairman of the local Soviet

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

, a position from which he organized an armed peasant band to expropriate the large privately held estates and redistribute those lands equally to the whole peasantry.

As the year went on, more anarchist political prisoners were released from prison and returned from exile, which brought a number of intellectuals into the movement. By the turn of 1918, further anarchist conferences had been held in Donbas, Kharkiv and Katerynoslav, resulting in the foundation of the newspaper ''Golos Anarkhista'' and the election of a Donbas Anarchist Bureau. The Bureau then organized a series of political lectures in Ukraine, inviting anarchist intellectuals such as Juda Grossman, Nikolai Rogdaev and Peter Arshinov

Peter Andreyevich Arshinov (russian: Пётр Андре́евич Арши́нов; 1887–1937), was a Russian anarchist revolutionary and intellectual who chronicled the history of the Makhnovshchina.

Initially a Bolshevik, during the 190 ...