Alkene Derivatives on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

In

General, Organic, and Biological Chemistry

'. 1232 pages. Two general types of monoalkenes are distinguished: terminal and internal. Also called α-olefins, terminal alkenes are more useful. However, the

CH2=CH2 + H2O -> CH3-CH2OH

Alkenes can also be converted into alcohols via the oxymercuration–demercuration reaction , the

CH2=CH2 + Br2 -> BrCH2-CH2Br

Related reactions are also used as quantitative measures of unsaturation, expressed as the bromine number and

CH2=CH2 + X2 + H2O -> XCH2-CH2OH + HX

RCH=CH2 + RCO3H -> RCHOCH2 + RCO2H

For ethylene, the C2H4 + 1/2 O2 -> C2H4O

Alkenes react with ozone, leading to the scission of the double bond. The process is called RCH=CHR' + O3 + SMe2 -> RCHO + R'CHO + O=SMe2

:R2C=CHR' + O3 -> R2CHO + R'CHO + O=SMe2

When treated with a hot concentrated, acidified solution of , alkenes are cleaved to form R'CH=CR2 + 1/2 O2 + H2O -> R'CH(OH)-C(OH)R2

This reaction is called dihydroxylation.

In the presence of an appropriate  Another example is the

Another example is the

Organic Chemistry with Biological Applications

'; 3rd edition. 1224 pages.

IUPAC Blue Book. * Rule A-4. Bivalent and Multivalent Radical

IUPAC Blue Book. * Rules A-11.3, A-11.4, A-11.5 Unsaturated monocyclic hydrocarbons and substituent

IUPAC Blue Book. * Rule A-23. Hydrogenated Compounds of Fused Polycyclic Hydrocarbon

IUPAC Blue Book.

organic chemistry

Organic chemistry is a subdiscipline within chemistry involving the science, scientific study of the structure, properties, and reactions of organic compounds and organic materials, i.e., matter in its various forms that contain carbon atoms.Clay ...

, an alkene is a hydrocarbon

In organic chemistry, a hydrocarbon is an organic compound consisting entirely of hydrogen and carbon. Hydrocarbons are examples of group 14 hydrides. Hydrocarbons are generally colourless and hydrophobic, and their odors are usually weak or ...

containing a carbon

Carbon () is a chemical element with the symbol C and atomic number 6. It is nonmetallic and tetravalent—its atom making four electrons available to form covalent chemical bonds. It belongs to group 14 of the periodic table. Carbon makes ...

–carbon double bond

In chemistry, a double bond is a covalent bond between two atoms involving four bonding electrons as opposed to two in a single bond. Double bonds occur most commonly between two carbon atoms, for example in alkenes. Many double bonds exist betw ...

.

Alkene is often used as synonym of olefin, that is, any hydrocarbon containing one or more double bonds.H. Stephen Stoker (2015): General, Organic, and Biological Chemistry

'. 1232 pages. Two general types of monoalkenes are distinguished: terminal and internal. Also called α-olefins, terminal alkenes are more useful. However, the

International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry

The International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC ) is an international federation of National Adhering Organizations working for the advancement of the chemical sciences, especially by developing nomenclature and terminology. It is ...

(IUPAC) recommends using the name "alkene" only for acyclic hydrocarbons with just one double bond; alkadiene, alkatriene, etc., or polyene

In organic chemistry, polyenes are poly- unsaturated, organic compounds that contain at least three alternating double () and single () carbon–carbon bonds. These carbon–carbon double bonds interact in a process known as conjugation, result ...

for acyclic hydrocarbons with two or more double bonds; cycloalkene, cycloalkadiene, etc. for cyclic ones; and "olefin" for the general class – cyclic or acyclic, with one or more double bonds.

Acyclic alkenes, with only one double bond and no other functional group

In organic chemistry, a functional group is a substituent or moiety in a molecule that causes the molecule's characteristic chemical reactions. The same functional group will undergo the same or similar chemical reactions regardless of the res ...

s (also known as mono-enes) form a homologous series

In organic chemistry, a homologous series is a sequence of compounds with the same functional group and similar chemical properties in which the members of the series can be branched or unbranched, or differ by molecular formula of and molecu ...

of hydrocarbon

In organic chemistry, a hydrocarbon is an organic compound consisting entirely of hydrogen and carbon. Hydrocarbons are examples of group 14 hydrides. Hydrocarbons are generally colourless and hydrophobic, and their odors are usually weak or ...

s with the general formula with ''n'' being 2 or more (which is two hydrogen

Hydrogen is the chemical element with the symbol H and atomic number 1. Hydrogen is the lightest element. At standard conditions hydrogen is a gas of diatomic molecules having the formula . It is colorless, odorless, tasteless, non-toxic ...

s less than the corresponding alkane

In organic chemistry

Organic chemistry is a subdiscipline within chemistry involving the science, scientific study of the structure, properties, and reactions of organic compounds and organic materials, i.e., matter in its various forms tha ...

). When ''n'' is four or more, isomer

In chemistry, isomers are molecules or polyatomic ions with identical molecular formulae – that is, same number of atoms of each element – but distinct arrangements of atoms in space. Isomerism is existence or possibility of isomers.

...

s are possible, distinguished by the position and conformation of the double bond.

Alkenes are generally colorless non-polar

In chemistry, polarity is a separation of electric charge leading to a molecule or its chemical groups having an electric dipole moment, with a negatively charged end and a positively charged end.

Polar molecules must contain one or more pol ...

compounds, somewhat similar to alkanes but more reactive. The first few members of the series are gases or liquids at room temperature. The simplest alkene, ethylene

Ethylene ( IUPAC name: ethene) is a hydrocarbon which has the formula or . It is a colourless, flammable gas with a faint "sweet and musky" odour when pure. It is the simplest alkene (a hydrocarbon with carbon-carbon double bonds).

Ethylene ...

() (or "ethene" in the IUPAC nomenclature

A chemical nomenclature is a set of rules to generate systematic names for chemical compounds. The nomenclature used most frequently worldwide is the one created and developed by the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC).

The ...

) is the organic compound

In chemistry, organic compounds are generally any chemical compounds that contain carbon- hydrogen or carbon-carbon bonds. Due to carbon's ability to catenate (form chains with other carbon atoms), millions of organic compounds are known. Th ...

produced on the largest scale industrially.

Aromatic

In chemistry, aromaticity is a chemical property of cyclic (ring-shaped), ''typically'' planar (flat) molecular structures with pi bonds in resonance (those containing delocalized electrons) that gives increased stability compared to sat ...

compounds are often drawn as cyclic alkenes, however their structure and properties are sufficiently distinct that they are not classified as alkenes or olefins. Hydrocarbons with two overlapping double bonds () are called allenes

In organic chemistry, allenes are organic compounds in which one carbon atom has double bonds with each of its two adjacent carbon centres (). Allenes are classified as cumulated dienes. The parent compound of this class is propadiene, which ...

—the simplest such compound is itself called ''allene

In organic chemistry, allenes are organic compounds in which one carbon atom has double bonds with each of its two adjacent carbon centres (). Allenes are classified as cumulated dienes. The parent compound of this class is propadiene, which i ...

''—and those with three or more overlapping bonds (, , etc.) are called cumulene

In organic chemistry, a cumulene is a compound having three or more ''cumulative'' (consecutive) double bonds. They are analogous to allenes, only having a more extensive chain. The simplest molecule in this class is butatriene (), which is a ...

s. Some authors do not consider allenes and cumulenes to be "alkenes".

Structural isomerism

Alkenes having four or morecarbon

Carbon () is a chemical element with the symbol C and atomic number 6. It is nonmetallic and tetravalent—its atom making four electrons available to form covalent chemical bonds. It belongs to group 14 of the periodic table. Carbon makes ...

atoms can form diverse structural isomer

In chemistry, a structural isomer (or constitutional isomer in the IUPAC nomenclature) of a compound is another compound whose molecule has the same number of atoms of each element, but with logically distinct bonds between them. The term met ...

s. Most alkenes are also isomers of cycloalkane

In organic chemistry, the cycloalkanes (also called naphthenes, but distinct from naphthalene) are the monocyclic saturated hydrocarbons. In other words, a cycloalkane consists only of hydrogen and carbon atoms arranged in a structure containin ...

s. Acyclic alkene structural isomers with only one double bond follow:

* : ethylene

Ethylene ( IUPAC name: ethene) is a hydrocarbon which has the formula or . It is a colourless, flammable gas with a faint "sweet and musky" odour when pure. It is the simplest alkene (a hydrocarbon with carbon-carbon double bonds).

Ethylene ...

only

* : propylene

Propylene, also known as propene, is an unsaturated organic compound with the chemical formula CH3CH=CH2. It has one double bond, and is the second simplest member of the alkene class of hydrocarbons. It is a colorless gas with a faint petrole ...

only

* : 3 isomers: 1-butene

1-Butene (or 1-Butylene) is the organic compound with the formula CH3CH2CH=CH2. It is a colorless gas that is easily condensed to give a colorless liquid. It is classified as a linear alpha-olefin. It is one of the isomers of butene (butylene ...

, 2-butene

But-2-ene is an acyclic alkene with four carbon atoms. It is the simplest alkene exhibiting ''cis''/''trans''-isomerism (also known as (''E''/''Z'')-isomerism); that is, it exists as two geometric isomers ''cis''-but-2-ene ((''Z'')-but-2-ene) and ...

, and isobutylene

Isobutylene (or 2-methylpropene) is a hydrocarbon with the chemical formula . It is a four-carbon branched alkene (olefin), one of the four isomers of butylene. It is a colorless flammable gas, and is of considerable industrial value.

Producti ...

* : 5 isomers: 1-pentene

Pentenes are alkenes with the chemical formula . Each contains one double bond within its molecular structure. Six different compounds are in this class, differing from each other by whether the carbon atoms are attached linearly or in a branched ...

, 2-pentene, 2-methyl-1-butene, 3-methyl-1-butene, 2-methyl-2-butene

2-Methyl-2-butene, 2m2b, 2-methylbut-2-ene, also beta-isoamylene is an alkene hydrocarbon with the molecular formula C5H10.

Used as a free radical scavenger in trichloromethane (chloroform) and dichloromethane (methylene chloride).

John Snow, th ...

* : 13 isomers: 1-hexene, 2-hexene, 3-hexene, 2-methyl-1-pentene, 3-methyl-1-pentene, 4-methyl-1-pentene, 2-methyl-2-pentene, 3-methyl-2-pentene, 4-methyl-2-pentene, 2,3-dimethyl-1-butene, 3,3-dimethyl-1-butene, 2,3-dimethyl-2-butene, 2-ethyl-1-butene

* : 27 isomers (calculated)

* : 2,281 isomers (calculated)

* : 193,706,542,776 isomers (calculated)

Many of these molecules exhibit ''cis''–''trans'' isomerism. There may also be chiral

Chirality is a property of asymmetry important in several branches of science. The word ''chirality'' is derived from the Greek (''kheir''), "hand", a familiar chiral object.

An object or a system is ''chiral'' if it is distinguishable from i ...

carbon atoms particularly within the larger molecules (from ). The number of potential isomers increases rapidly with additional carbon atoms.

Structure and bonding

Bonding

A carbon–carbon double bond consists of asigma bond

In chemistry, sigma bonds (σ bonds) are the strongest type of covalent chemical bond. They are formed by head-on overlapping between atomic orbitals. Sigma bonding is most simply defined for diatomic molecules using the language and tools o ...

and a pi bond

In chemistry, pi bonds (π bonds) are covalent chemical bonds, in each of which two lobes of an orbital on one atom overlap with two lobes of an orbital on another atom, and in which this overlap occurs laterally. Each of these atomic orbita ...

. This double bond is stronger than a single covalent bond (611 kJ/ mol for C=C vs. 347 kJ/mol for C–C), but not twice as strong. Double bonds are shorter than single bonds with an average bond length

In molecular geometry, bond length or bond distance is defined as the average distance between nuclei of two bonded atoms in a molecule. It is a transferable property of a bond between atoms of fixed types, relatively independent of the rest ...

of 1.33 Å (133 pm) vs 1.53 Å for a typical C-C single bond.

Each carbon atom of the double bond uses its three sp2 hybrid orbitals to form sigma bonds to three atoms (the other carbon atom and two hydrogen atoms). The unhybridized 2p atomic orbitals, which lie perpendicular to the plane created by the axes of the three sp² hybrid orbitals, combine to form the pi bond. This bond lies outside the main C–C axis, with half of the bond on one side of the molecule and a half on the other. With a strength of 65 kcal/mol, the pi bond is significantly weaker than the sigma bond.

Rotation about the carbon–carbon double bond is restricted because it incurs an energetic cost to break the alignment of the p orbitals on the two carbon atoms. Consequently ''cis'' or ''trans'' isomers interconvert so slowly that they can be freely handled at ambient conditions without isomerization. More complex alkenes may be named with the ''E''–''Z'' notation for molecules with three or four different substituent

A substituent is one or a group of atoms that replaces (one or more) atoms, thereby becoming a moiety in the resultant (new) molecule. (In organic chemistry and biochemistry, the terms ''substituent'' and '' functional group'', as well as '' ...

s (side groups). For example, of the isomers of butene, the two methyl groups of (''Z'')-but-2 -ene (a.k.a. ''cis''-2-butene) appear on the same side of the double bond, and in (''E'')-but-2-ene (a.k.a. ''trans''-2-butene) the methyl groups appear on opposite sides. These two isomers of butene have distinct properties.

Shape

As predicted by the VSEPR model ofelectron

The electron (, or in nuclear reactions) is a subatomic particle with a negative one elementary electric charge. Electrons belong to the first generation of the lepton particle family,

and are generally thought to be elementary partic ...

pair repulsion, the molecular geometry

Molecular geometry is the three-dimensional space, three-dimensional arrangement of the atoms that constitute a molecule. It includes the general shape of the molecule as well as bond lengths, bond angles, torsional angles and any other geometric ...

of alkenes includes bond angle

Bond or bonds may refer to:

Common meanings

* Bond (finance), a type of debt security

* Bail bond, a commercial third-party guarantor of surety bonds in the United States

* Chemical bond, the attraction of atoms, ions or molecules to form chemi ...

s about each carbon atom in a double bond of about 120°. The angle may vary because of steric strain Van der Waals strain is strain resulting from Van der Waals repulsion when two substituents in a molecule approach each other with a distance less than the sum of their Van der Waals radii.

Van der Waals strain is also called Van der Waals repul ...

introduced by nonbonded interactions between functional group

In organic chemistry, a functional group is a substituent or moiety in a molecule that causes the molecule's characteristic chemical reactions. The same functional group will undergo the same or similar chemical reactions regardless of the res ...

s attached to the carbon atoms of the double bond. For example, the C–C–C bond angle in propylene

Propylene, also known as propene, is an unsaturated organic compound with the chemical formula CH3CH=CH2. It has one double bond, and is the second simplest member of the alkene class of hydrocarbons. It is a colorless gas with a faint petrole ...

is 123.9°.

For bridged alkenes, Bredt's rule Bredt's rule is an empirical observation in organic chemistry that states that a double bond cannot be placed at the bridgehead of a bridged ring system, unless the rings are large enough. The rule is named after Julius Bredt, who first discussed ...

states that a double bond cannot occur at the bridgehead of a bridged ring system unless the rings are large enough. Following Fawcett and defining ''S'' as the total number of non-bridgehead atoms in the rings, bicyclic systems require ''S'' ≥ 7 for stability and tricyclic systems require ''S'' ≥ 11.

Physical properties

Many of the physical properties of alkenes andalkane

In organic chemistry

Organic chemistry is a subdiscipline within chemistry involving the science, scientific study of the structure, properties, and reactions of organic compounds and organic materials, i.e., matter in its various forms tha ...

s are similar: they are colorless, nonpolar, and combustible. The physical state depends on molecular mass

The molecular mass (''m'') is the mass of a given molecule: it is measured in daltons (Da or u). Different molecules of the same compound may have different molecular masses because they contain different isotopes of an element. The related quant ...

: like the corresponding saturated hydrocarbons, the simplest alkenes (ethylene

Ethylene ( IUPAC name: ethene) is a hydrocarbon which has the formula or . It is a colourless, flammable gas with a faint "sweet and musky" odour when pure. It is the simplest alkene (a hydrocarbon with carbon-carbon double bonds).

Ethylene ...

, propylene

Propylene, also known as propene, is an unsaturated organic compound with the chemical formula CH3CH=CH2. It has one double bond, and is the second simplest member of the alkene class of hydrocarbons. It is a colorless gas with a faint petrole ...

, and butene) are gases at room temperature. Linear alkenes of approximately five to sixteen carbon atoms are liquids, and higher alkenes are waxy solids. The melting point of the solids also increases with increase in molecular mass.

Alkenes generally have stronger smells than their corresponding alkanes. Ethylene has a sweet and musty odor. The binding of cupric ion to the olefin in the mammalian olfactory receptor MOR244-3 is implicated in the smell of alkenes (as well as thiols). Strained alkenes, in particular, like norbornene and ''trans''-cyclooctene are known to have strong, unpleasant odors, a fact consistent with the stronger π complexes they form with metal ions including copper.

Reactions

Alkenes are relatively stable compounds, but are more reactive thanalkane

In organic chemistry

Organic chemistry is a subdiscipline within chemistry involving the science, scientific study of the structure, properties, and reactions of organic compounds and organic materials, i.e., matter in its various forms tha ...

s. Most reactions of alkenes involve additions to this pi bond, forming new single bonds. Alkenes serve as a feedstock for the petrochemical industry

The petrochemical industry is concerned with the production and trade of petrochemicals. A major part is constituted by the plastics (polymer) industry. It directly interfaces with the petroleum industry, especially the downstream sector.

Comp ...

because they can participate in a wide variety of reactions, prominently polymerization and alkylation.

Except for ethylene, alkenes have two sites of reactivity: the carbon–carbon pi-bond and the presence of allylic

In organic chemistry, an allyl group is a substituent with the structural formula , where R is the rest of the molecule. It consists of a methylene bridge () attached to a vinyl group (). The name is derived from the scientific name for garlic, . ...

CH centers. The former dominates but the allylic site are important too.

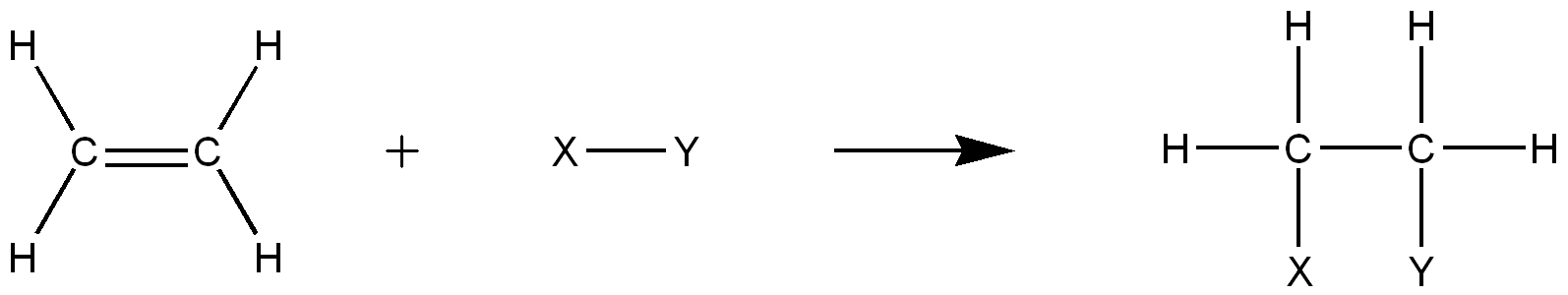

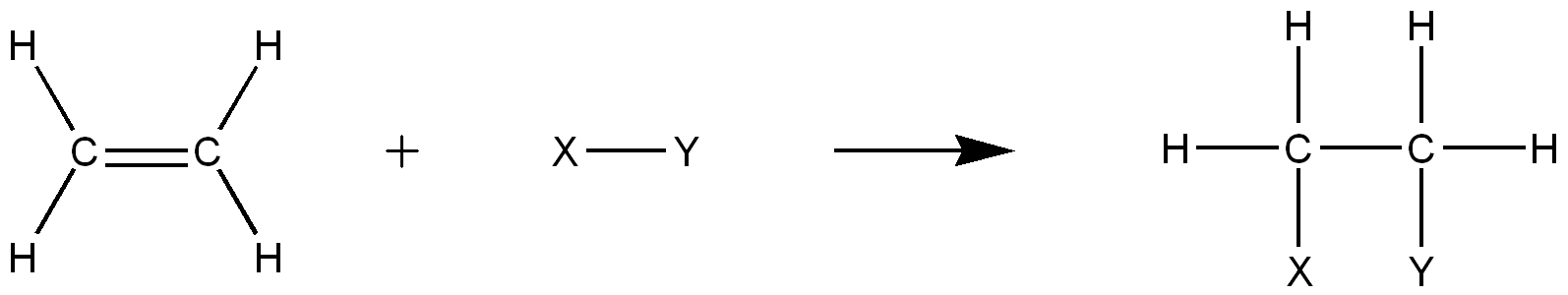

Addition reactions

Alkenes react in manyaddition reaction

In organic chemistry, an addition reaction is, in simplest terms, an organic reaction where two or more molecules combine to form a larger one (the adduct)..

Addition reactions are limited to chemical compounds that have multiple bonds, such as ...

s, which occur by opening up the double-bond. Most of these addition reactions follow the mechanism of electrophilic addition. Examples are hydrohalogenation

A hydrohalogenation reaction is the electrophilic addition of hydrohalic acids like hydrogen chloride or hydrogen bromide to alkenes to yield the corresponding haloalkanes.

:

If the two carbon atoms at the double bond are linked to a different ...

, halogenation

In chemistry, halogenation is a chemical reaction that entails the introduction of one or more halogens into a compound. Halide-containing compounds are pervasive, making this type of transformation important, e.g. in the production of polyme ...

, halohydrin formation, oxymercuration, hydroboration

In organic chemistry, hydroboration refers to the addition of a hydrogen- boron bond to certain double and triple bonds involving carbon (, , , and ). This chemical reaction is useful in the organic synthesis of organic compounds.

Hydroboration ...

, dichlorocarbene addition

Dichlorocarbene is the reactive intermediate with chemical formula CCl2. Although this chemical species has not been isolated, it is a common intermediate in organic chemistry, being generated from chloroform. This bent diamagnetic molecule rapidly ...

, Simmons–Smith reaction, catalytic hydrogenation, epoxidation

In organic chemistry, an epoxide is a cyclic ether () with a three-atom ring. This ring approximates an equilateral triangle, which makes it strained, and hence highly reactive, more so than other ethers. They are produced on a large scal ...

, radical polymerization

In polymer chemistry, free-radical polymerization (FRP) is a method of polymerization by which a polymer forms by the successive addition of free-radical building blocks ( repeat units). Free radicals can be formed by a number of different mechan ...

and hydroxylation

In chemistry, hydroxylation can refer to:

*(i) most commonly, hydroxylation describes a chemical process that introduces a hydroxyl group () into an organic compound.

*(ii) the ''degree of hydroxylation'' refers to the number of OH groups in a ...

.

:

Hydrogenation and related hydroelementations

Hydrogenation

Hydrogenation is a chemical reaction between molecular hydrogen (H2) and another compound or element, usually in the presence of a catalyst such as nickel, palladium or platinum. The process is commonly employed to reduce or saturate org ...

of alkenes produces the corresponding alkane

In organic chemistry

Organic chemistry is a subdiscipline within chemistry involving the science, scientific study of the structure, properties, and reactions of organic compounds and organic materials, i.e., matter in its various forms tha ...

s. The reaction is sometimes carried out under pressure and at elevated temperature. Metallic catalyst

Catalysis () is the process of increasing the rate of a chemical reaction by adding a substance known as a catalyst (). Catalysts are not consumed in the reaction and remain unchanged after it. If the reaction is rapid and the catalyst recyc ...

s are almost always required. Common industrial catalysts are based on platinum

Platinum is a chemical element with the symbol Pt and atomic number 78. It is a dense, malleable, ductile, highly unreactive, precious, silverish-white transition metal. Its name originates from Spanish , a diminutive of "silver".

Pla ...

, nickel

Nickel is a chemical element with symbol Ni and atomic number 28. It is a silvery-white lustrous metal with a slight golden tinge. Nickel is a hard and ductile transition metal. Pure nickel is chemically reactive but large pieces are slow ...

, and palladium

Palladium is a chemical element with the symbol Pd and atomic number 46. It is a rare and lustrous silvery-white metal discovered in 1803 by the English chemist William Hyde Wollaston. He named it after the asteroid Pallas, which was itself nam ...

. A large scale application is the production of margarine

Margarine (, also , ) is a spread used for flavoring, baking, and cooking. It is most often used as a substitute for butter. Although originally made from animal fats, most margarine consumed today is made from vegetable oil. The spread was orig ...

.

Aside from the addition of across the double bond, many other 's can be added. These processes are often of great commercial significance. One example is the addition of H-SiR3, i.e., hydrosilylation Hydrosilylation, also called catalytic hydrosilation, describes the addition of Si-H bonds across unsaturated bonds."Hydrosilylation A Comprehensive Review on Recent Advances" B. Marciniec (ed.), Advances in Silicon Science, Springer Science, 2009 ...

. This reaction is used to generate organosilicon compound

Organosilicon compounds are organometallic compounds containing carbon–silicon bonds. Organosilicon chemistry is the corresponding science of their preparation and properties. Most organosilicon compounds are similar to the ordinary organic co ...

s. Another reaction is hydrocyanation, the addition of across the double bond.

Hydration

Hydration, the addition of water across the double bond of alkenes, yieldsalcohol

Alcohol most commonly refers to:

* Alcohol (chemistry), an organic compound in which a hydroxyl group is bound to a carbon atom

* Alcohol (drug), an intoxicant found in alcoholic drinks

Alcohol may also refer to:

Chemicals

* Ethanol, one of sev ...

s. The reaction is catalyzed by phosphoric acid

Phosphoric acid (orthophosphoric acid, monophosphoric acid or phosphoric(V) acid) is a colorless, odorless phosphorus-containing solid, and inorganic compound with the chemical formula . It is commonly encountered as an 85% aqueous solutio ...

or sulfuric acid. This reaction is carried out on an industrial scale to produce synthetic ethanol

Ethanol (abbr. EtOH; also called ethyl alcohol, grain alcohol, drinking alcohol, or simply alcohol) is an organic compound. It is an alcohol with the chemical formula . Its formula can be also written as or (an ethyl group linked to a h ...

.

:hydroboration–oxidation reaction Hydroboration–oxidation reaction is a two-step hydration reaction that converts an alkene into an Alcohol (chemistry), alcohol. The process results in the Syn and anti addition, syn addition of a hydrogen and a hydroxyl group where the double bond ...

or by Mukaiyama hydration.

Halogenation

Inelectrophilic halogenation

In organic chemistry, an electrophilic aromatic halogenation is a type of electrophilic aromatic substitution. This organic reaction is typical of aromatic compounds and a very useful method for adding substituents to an aromatic system.

:

A few ...

the addition of elemental bromine

Bromine is a chemical element with the symbol Br and atomic number 35. It is the third-lightest element in group 17 of the periodic table (halogens) and is a volatile red-brown liquid at room temperature that evaporates readily to form a simil ...

or chlorine

Chlorine is a chemical element with the symbol Cl and atomic number 17. The second-lightest of the halogens, it appears between fluorine and bromine in the periodic table and its properties are mostly intermediate between them. Chlorine is ...

to alkenes yields vicinal dibromo- and dichloroalkanes (1,2-dihalides or ethylene dihalides), respectively. The decoloration of a solution of bromine in water is an analytical test for the presence of alkenes:

:iodine number

Iodine is a chemical element with the symbol I and atomic number 53. The heaviest of the stable halogens, it exists as a semi-lustrous, non-metallic solid at standard conditions that melts to form a deep violet liquid at , and boils to a vi ...

of a compound or mixture.

Hydrohalogenation

Hydrohalogenation

A hydrohalogenation reaction is the electrophilic addition of hydrohalic acids like hydrogen chloride or hydrogen bromide to alkenes to yield the corresponding haloalkanes.

:

If the two carbon atoms at the double bond are linked to a different ...

is the addition of hydrogen halide

In chemistry, hydrogen halides (hydrohalic acids when in the aqueous phase) are diatomic, inorganic compounds that function as Arrhenius acids. The formula is HX where X is one of the halogens: fluorine, chlorine, bromine, iodine, or astati ...

s, such as HCl or HI, to alkenes to yield the corresponding haloalkane

The haloalkanes (also known as halogenoalkanes or alkyl halides) are alkanes containing one or more halogen substituents. They are a subset of the general class of halocarbons, although the distinction is not often made. Haloalkanes are widely ...

s:

:

If the two carbon atoms at the double bond are linked to a different number of hydrogen atoms, the halogen is found preferentially at the carbon with fewer hydrogen substituents. This patterns is known as Markovnikov's rule

In organic chemistry, Markovnikov's rule or Markownikoff's rule describes the outcome of some addition reactions. The rule was formulated by Russian chemist Vladimir Markovnikov in 1870.

Explanation

The rule states that with the addition of a ...

. The use of radical initiators or other compounds can lead to the opposite product result. Hydrobromic acid in particular is prone to forming radicals in the presence of various impurities or even atmospheric oxygen, leading to the reversal of the Markovnikov result:

:

Halohydrin formation

Alkenes react with water and halogens to form halohydrins by an addition reaction. Markovnikov regiochemistry and anti-stereochemistry occur. :Oxidation

Alkenes react with percarboxylic acids and even hydrogen peroxide to yieldepoxide

In organic chemistry, an epoxide is a cyclic ether () with a three-atom ring. This ring approximates an equilateral triangle, which makes it strained, and hence highly reactive, more so than other ethers. They are produced on a large scale ...

s:

:epoxidation

In organic chemistry, an epoxide is a cyclic ether () with a three-atom ring. This ring approximates an equilateral triangle, which makes it strained, and hence highly reactive, more so than other ethers. They are produced on a large scal ...

is conducted on a very large scale industrially using oxygen in the presence of catalysts:

:ozonolysis

In organic chemistry, ozonolysis is an organic reaction where the unsaturated bonds of alkenes (), alkynes (), or azo compounds () are cleaved with ozone (). Alkenes and alkynes form organic compounds in which the multiple carbon–carbon bon ...

. Often the reaction procedure includes a mild reductant, such as dimethylsulfide ():

:ketone

In organic chemistry, a ketone is a functional group with the structure R–C(=O)–R', where R and R' can be a variety of carbon-containing substituents. Ketones contain a carbonyl group –C(=O)– (which contains a carbon-oxygen double bon ...

s and/or carboxylic acid

In organic chemistry, a carboxylic acid is an organic acid that contains a carboxyl group () attached to an R-group. The general formula of a carboxylic acid is or , with R referring to the alkyl, alkenyl, aryl, or other group. Carboxyl ...

s. The stoichiometry of the reaction is sensitive to conditions. This reaction and the ozonolysis can be used to determine the position of a double bond in an unknown alkene.

The oxidation can be stopped at the vicinal diol

A diol is a chemical compound containing two hydroxyl groups ( groups). An aliphatic diol is also called a glycol. This pairing of functional groups is pervasive, and many subcategories have been identified.

The most common industrial diol is ...

rather than full cleavage of the alkene by using osmium tetroxide

Osmium tetroxide (also osmium(VIII) oxide) is the chemical compound with the formula OsO4. The compound is noteworthy for its many uses, despite its toxicity and the rarity of osmium. It also has a number of unusual properties, one being that the ...

or other oxidants:

:photosensitiser

Photosensitizers produce a physicochemical change in a neighboring molecule by either donating an electron to the substrate or by abstracting a hydrogen atom from the substrate. At the end of this process, the photosensitizer eventually returns to ...

, such as methylene blue

Methylthioninium chloride, commonly called methylene blue, is a salt used as a dye and as a medication. Methylene blue is a thiazine dye. As a medication, it is mainly used to treat methemoglobinemia by converting the ferric iron in hemoglob ...

and light, alkenes can undergo reaction with reactive oxygen species generated by the photosensitiser, such as hydroxyl radical

The hydroxyl radical is the diatomic molecule . The hydroxyl radical is very stable as a dilute gas, but it decays very rapidly in the condensed phase. It is pervasive in some situations. Most notably the hydroxyl radicals are produced from the ...

s, singlet oxygen

Singlet oxygen, systematically named dioxygen(singlet) and dioxidene, is a gaseous inorganic chemical with the formula O=O (also written as or ), which is in a quantum state where all electrons are spin paired. It is kinetically unstable at ambie ...

or superoxide

In chemistry, a superoxide is a compound that contains the superoxide ion, which has the chemical formula . The systematic name of the anion is dioxide(1−). The reactive oxygen ion superoxide is particularly important as the product of ...

ion. Reactions of the excited sensitizer can involve electron or hydrogen transfer, usually with a reducing substrate (Type I reaction) or interaction with oxygen (Type II reaction). These various alternative processes and reactions can be controlled by choice of specific reaction conditions, leading to a wide range of products. A common example is the +2cycloaddition

In organic chemistry, a cycloaddition is a chemical reaction in which "two or more unsaturated molecules (or parts of the same molecule) combine with the formation of a cyclic adduct in which there is a net reduction of the bond multiplicity". ...

of singlet oxygen with a diene

In organic chemistry a diene ( ) (diolefin ( ) or alkadiene) is a covalent compound that contains two double bonds, usually among carbon atoms. They thus contain two alk''ene'' units, with the standard prefix ''di'' of systematic nomenclature ...

such as cyclopentadiene

Cyclopentadiene is an organic compound with the formula C5H6.LeRoy H. Scharpen and Victor W. Laurie (1965): "Structure of cyclopentadiene". ''The Journal of Chemical Physics'', volume 43, issue 8, pages 2765-2766. It is often abbreviated CpH beca ...

to yield an endoperoxide:

Schenck ene reaction

Jewish (Ashkenazic) and German occupational surname derived from ''schenken'' (to pour out or serve) referring to the medieval profession of cup-bearer or wine server (later also to tavern keeper). At one time only Jews were allowed to sell alco ...

, in which singlet oxygen reacts with an allyl

In organic chemistry, an allyl group is a substituent with the structural formula , where R is the rest of the molecule. It consists of a methylene bridge () attached to a vinyl group (). The name is derived from the scientific name for garlic, ...

ic structure to give a transposed allyl peroxide

In chemistry, peroxides are a group of compounds with the structure , where R = any element. The group in a peroxide is called the peroxide group or peroxo group. The nomenclature is somewhat variable.

The most common peroxide is hydrogen ...

:

Polymerization

Terminal alkenes are precursors topolymer

A polymer (; Greek ''poly-'', "many" + '' -mer'', "part")

is a substance or material consisting of very large molecules called macromolecules, composed of many repeating subunits. Due to their broad spectrum of properties, both synthetic and ...

s via processes termed polymerization

In polymer chemistry, polymerization (American English), or polymerisation (British English), is a process of reacting monomer molecules together in a chemical reaction to form polymer chains or three-dimensional networks. There are many fo ...

. Some polymerizations are of great economic significance, as they generate as the plastics polyethylene

Polyethylene or polythene (abbreviated PE; IUPAC name polyethene or poly(methylene)) is the most commonly produced plastic. It is a polymer, primarily used for packaging (plastic bags, plastic films, geomembranes and containers including ...

and polypropylene

Polypropylene (PP), also known as polypropene, is a thermoplastic polymer used in a wide variety of applications. It is produced via chain-growth polymerization from the monomer propylene.

Polypropylene

belongs to the group of polyolefins an ...

. Polymers from alkene are usually referred to as '' polyolefins'' although they contain no olefins. Polymerization can proceed via diverse mechanisms. conjugated diene

In organic chemistry a diene ( ) (diolefin ( ) or alkadiene) is a covalent compound that contains two double bonds, usually among carbon atoms. They thus contain two alk''ene'' units, with the standard prefix ''di'' of systematic nomenclature ...

s such as buta-1,3-diene

1,3-Butadiene () is the organic compound with the formula (CH2=CH)2. It is a colorless gas that is easily condensed to a liquid. It is important industrially as a precursor to synthetic rubber. The molecule can be viewed as the union of two viny ...

and isoprene

Isoprene, or 2-methyl-1,3-butadiene, is a common volatile organic compound with the formula CH2=C(CH3)−CH=CH2. In its pure form it is a colorless volatile liquid. Isoprene is an unsaturated hydrocarbon. It is produced by many plants and animals ...

(2-methylbuta-1,3-diene) also produce polymers, one example being natural rubber.

Metal complexation

: Alkenes areligand

In coordination chemistry, a ligand is an ion or molecule ( functional group) that binds to a central metal atom to form a coordination complex. The bonding with the metal generally involves formal donation of one or more of the ligand's ele ...

s in transition metal alkene complexes. The two carbon centres bond to the metal using the pi- and pi*-orbitals. Mono- and diolefins are often used as ligands in stable complexes. Cyclooctadiene

A cyclooctadiene (sometimes abbreviated COD) is any of several cyclic diene with the formula (CH2)4(C2H2)2. Focusing only on cis derivatives, four isomers are possible: 1,2-, which is an allene, 1,3-, 1,4-, and 1,5-. Commonly encountered isomers ar ...

and norbornadiene are popular chelating agents, and even ethylene

Ethylene ( IUPAC name: ethene) is a hydrocarbon which has the formula or . It is a colourless, flammable gas with a faint "sweet and musky" odour when pure. It is the simplest alkene (a hydrocarbon with carbon-carbon double bonds).

Ethylene ...

itself is sometimes used as a ligand, for example, in Zeise's salt

Zeise's salt, potassium trichloro(ethylene)platinate(II), is the chemical compound with the formula K platinum.html" ;"title="/nowiki>platinum">PtCl3(C2H4)�H2O. The anion of this air-stable, yellow, coordination complex contains an hapticity"> ...

. In addition, metal–alkene complexes are intermediates in many metal-catalyzed reactions including hydrogenation, hydroformylation, and polymerization.

Reaction overview

Synthesis

Industrial methods

Alkenes are produced by hydrocarbon cracking. Raw materials are mostlynatural gas condensate

Natural-gas condensate, also called natural gas liquids, is a low-density mixture of hydrocarbon liquids that are present as gaseous components in the raw natural gas produced from many natural gas fields. Some gas species within the raw natur ...

components (principally ethane and propane) in the US and Mideast and naphtha

Naphtha ( or ) is a flammable liquid hydrocarbon mixture.

Mixtures labelled ''naphtha'' have been produced from natural gas condensates, petroleum distillates, and the distillation of coal tar and peat. In different industries and regions ...

in Europe and Asia. Alkanes are broken apart at high temperatures, often in the presence of a zeolite

Zeolites are microporous, crystalline aluminosilicate materials commonly used as commercial adsorbents and catalysts. They mainly consist of silicon, aluminium, oxygen, and have the general formula ・y where is either a metal ion or H+. These ...

catalyst, to produce a mixture of primarily aliphatic alkenes and lower molecular weight alkanes. The mixture is feedstock and temperature dependent, and separated by fractional distillation. This is mainly used for the manufacture of small alkenes (up to six carbons).

Related to this is catalytic dehydrogenation

In chemistry, dehydrogenation is a chemical reaction that involves the removal of hydrogen, usually from an organic molecule. It is the reverse of hydrogenation. Dehydrogenation is important, both as a useful reaction and a serious problem. A ...

, where an alkane loses hydrogen at high temperatures to produce a corresponding alkene. This is the reverse of the catalytic hydrogenation of alkenes.

This process is also known as reforming. Both processes are endothermic and are driven towards the alkene at high temperatures by entropy

Entropy is a scientific concept, as well as a measurable physical property, that is most commonly associated with a state of disorder, randomness, or uncertainty. The term and the concept are used in diverse fields, from classical thermodyna ...

.

Catalytic

Catalysis () is the process of increasing the rate of a chemical reaction by adding a substance known as a catalyst (). Catalysts are not consumed in the reaction and remain unchanged after it. If the reaction is rapid and the catalyst recycl ...

synthesis of higher α-alkenes (of the type RCH=CH2) can also be achieved by a reaction of ethylene with the organometallic compound

Organometallic chemistry is the study of organometallic compounds, chemical compounds containing at least one chemical bond between a carbon atom of an organic molecule and a metal, including alkali, alkaline earth, and transition metals, and so ...

triethylaluminium

Triethylaluminium is one of the simplest examples of an organoaluminium compound. Despite its name it has the formula Al2( C2H5)6 (abbreviated as Al2Et6 or TEA), as it exists as a dimer. This colorless liquid is pyrophoric. It is an industrial ...

in the presence of nickel

Nickel is a chemical element with symbol Ni and atomic number 28. It is a silvery-white lustrous metal with a slight golden tinge. Nickel is a hard and ductile transition metal. Pure nickel is chemically reactive but large pieces are slow ...

, cobalt

Cobalt is a chemical element with the symbol Co and atomic number 27. As with nickel, cobalt is found in the Earth's crust only in a chemically combined form, save for small deposits found in alloys of natural meteoric iron. The free element, ...

, or platinum

Platinum is a chemical element with the symbol Pt and atomic number 78. It is a dense, malleable, ductile, highly unreactive, precious, silverish-white transition metal. Its name originates from Spanish , a diminutive of "silver".

Pla ...

.

Elimination reactions

One of the principal methods for alkene synthesis in the laboratory is the roomelimination

Elimination may refer to:

Science and medicine

* Elimination reaction, an organic reaction in which two functional groups split to form an organic product

*Bodily waste elimination, discharging feces, urine, or foreign substances from the bo ...

of alkyl halides, alcohols, and similar compounds. Most common is the β-elimination via the E2 or E1 mechanism, but α-eliminations are also known.

The E2 mechanism provides a more reliable β-elimination method than E1 for most alkene syntheses. Most E2 eliminations start with an alkyl halide or alkyl sulfonate ester (such as a tosylate

In organic chemistry, a toluenesulfonyl group (tosyl group, abbreviated Ts or Tos) is a univalent functional group with the chemical formula –. It consists of a tolyl group, –, joined to a sulfonyl group, ––, with the open valence on ...

or triflate

In organic chemistry, triflate ( systematic name: trifluoromethanesulfonate), is a functional group with the formula and structure . The triflate group is often represented by , as opposed to −Tf, which is the triflyl group, . For example, ...

). When an alkyl halide is used, the reaction is called a dehydrohalogenation. For unsymmetrical products, the more substituted alkenes (those with fewer hydrogens attached to the C=C) tend to predominate (see Zaitsev's rule

In organic chemistry, Zaitsev's rule (or Saytzeff's rule, Saytzev's rule) is an empirical rule for predicting the favored alkene product(s) in elimination reactions. While at the University of Kazan, Russian chemist Alexander Zaitsev studied a va ...

). Two common methods of elimination reactions are dehydrohalogenation of alkyl halides and dehydration of alcohols. A typical example is shown below; note that if possible, the H is ''anti'' to the leaving group, even though this leads to the less stable ''Z''-isomer.

Alkenes can be synthesized from alcohols via dehydration

In physiology, dehydration is a lack of total body water, with an accompanying disruption of metabolic processes. It occurs when free water loss exceeds free water intake, usually due to exercise, disease, or high environmental temperature. Mi ...

, in which case water is lost via the E1 mechanism. For example, the dehydration of ethanol

Ethanol (abbr. EtOH; also called ethyl alcohol, grain alcohol, drinking alcohol, or simply alcohol) is an organic compound. It is an alcohol with the chemical formula . Its formula can be also written as or (an ethyl group linked to a h ...

produces ethylene:

:CH3CH2OH → H2C=CH2 + H2O

An alcohol may also be converted to a better leaving group (e.g., xanthate), so as to allow a milder ''syn''-elimination such as the Chugaev elimination and the Grieco elimination. Related reactions include eliminations by β-haloethers (the Boord olefin synthesis) and esters ( ester pyrolysis).

Alkenes can be prepared indirectly from alkyl amine

In chemistry, amines (, ) are compounds and functional groups that contain a basic nitrogen atom with a lone pair. Amines are formally derivatives of ammonia (), wherein one or more hydrogen atoms have been replaced by a substituent su ...

s. The amine or ammonia is not a suitable leaving group, so the amine is first either alkylated (as in the Hofmann elimination

Hofmann elimination is an elimination reaction of an amine to form alkenes. The least stable alkene (the one with the least number of substituents on the carbons of the double bond), called the Hofmann product, is formed. This tendency, known as ...

) or oxidized to an amine oxide (the Cope reaction) to render a smooth elimination possible. The Cope reaction is a ''syn''-elimination that occurs at or below 150 °C, for example:

The Hofmann elimination is unusual in that the ''less'' substituted (non- Zaitsev) alkene is usually the major product.

Alkenes are generated from α-halo sulfones in the Ramberg–Bäcklund reaction, via a three-membered ring sulfone intermediate.

Synthesis from carbonyl compounds

Another important method for alkene synthesis involves construction of a new carbon–carbon double bond by coupling of a carbonyl compound (such as analdehyde

In organic chemistry, an aldehyde () is an organic compound containing a functional group with the structure . The functional group itself (without the "R" side chain) can be referred to as an aldehyde but can also be classified as a formyl group ...

or ketone

In organic chemistry, a ketone is a functional group with the structure R–C(=O)–R', where R and R' can be a variety of carbon-containing substituents. Ketones contain a carbonyl group –C(=O)– (which contains a carbon-oxygen double bon ...

) to a carbanion

In organic chemistry, a carbanion is an anion in which carbon is trivalent (forms three bonds) and bears a formal negative charge (in at least one significant resonance form).

Formally, a carbanion is the conjugate base of a carbon acid:

:R3CH ...

equivalent. Such reactions are sometimes called ''olefinations''. The most well-known of these methods is the Wittig reaction

The Wittig reaction or Wittig olefination is a chemical reaction of an aldehyde or ketone with a triphenyl phosphonium ylide called a Wittig reagent. Wittig reactions are most commonly used to convert aldehydes and ketones to alkenes. Most ...

, but other related methods are known, including the Horner–Wadsworth–Emmons reaction.

The Wittig reaction involves reaction of an aldehyde or ketone with a Wittig reagent (or phosphorane) of the type Ph3P=CHR to produce an alkene and Ph3P=O. The Wittig reagent is itself prepared easily from triphenylphosphine

Triphenylphosphine (IUPAC name: triphenylphosphane) is a common organophosphorus compound with the formula P(C6H5)3 and often abbreviated to P Ph3 or Ph3P. It is widely used in the synthesis of organic and organometallic compounds. PPh3 exists ...

and an alkyl halide. The reaction is quite general and many functional groups are tolerated, even esters, as in this example:

Related to the Wittig reaction is the Peterson olefination, which uses silicon-based reagents in place of the phosphorane. This reaction allows for the selection of ''E''- or ''Z''-products. If an ''E''-product is desired, another alternative is the Julia olefination, which uses the carbanion generated from a phenyl

In organic chemistry, the phenyl group, or phenyl ring, is a cyclic group of atoms with the formula C6 H5, and is often represented by the symbol Ph. Phenyl group is closely related to benzene and can be viewed as a benzene ring, minus a hydroge ...

sulfone. The Takai olefination based on an organochromium intermediate also delivers E-products. A titanium compound, Tebbe's reagent, is useful for the synthesis of methylene compounds; in this case, even esters and amides react.

A pair of ketones or aldehydes can be deoxygenated to generate an alkene. Symmetrical alkenes can be prepared from a single aldehyde or ketone coupling with itself, using titanium

Titanium is a chemical element with the Symbol (chemistry), symbol Ti and atomic number 22. Found in nature only as an oxide, it can be reduced to produce a lustrous transition metal with a silver color, low density, and high strength, resista ...

metal reduction (the McMurry reaction). If different ketones are to be coupled, a more complicated method is required, such as the Barton–Kellogg reaction

The Barton–Kellogg reaction is a coupling reaction between a diazo compound and a thioketone, giving an alkene by way of an episulfide intermediate. The Barton–Kellogg reaction is also known as Barton–Kellogg olefination and Barton olefin s ...

.

A single ketone can also be converted to the corresponding alkene via its tosylhydrazone, using sodium methoxide

Sodium methoxide is the simplest sodium alkoxide. With the formula , it is a white solid, which is formed by the deprotonation of methanol. Itis a widely used reagent in industry and the laboratory. It is also a dangerously caustic base. ...

(the Bamford–Stevens reaction The Bamford–Stevens reaction is a chemical reaction whereby treatment of tosylhydrazones with strong base gives alkenes. It is named for the British chemist William Randall Bamford and the Scottish chemist Thomas Stevens Stevens (1900–2000). ...

) or an alkyllithium (the Shapiro reaction).

Synthesis from alkenes

The formation of longer alkenes via the step-wise polymerisation of smaller ones is appealing, asethylene

Ethylene ( IUPAC name: ethene) is a hydrocarbon which has the formula or . It is a colourless, flammable gas with a faint "sweet and musky" odour when pure. It is the simplest alkene (a hydrocarbon with carbon-carbon double bonds).

Ethylene ...

(the smallest alkene) is both inexpensive and readily available, with hundreds of millions of tonnes produced annually. The Ziegler–Natta process allows for the formation of very long chains, for instance those used for polyethylene

Polyethylene or polythene (abbreviated PE; IUPAC name polyethene or poly(methylene)) is the most commonly produced plastic. It is a polymer, primarily used for packaging (plastic bags, plastic films, geomembranes and containers including ...

. Where shorter chains are wanted, as they for the production of surfactant

Surfactants are chemical compounds that decrease the surface tension between two liquids, between a gas and a liquid, or interfacial tension between a liquid and a solid. Surfactants may act as detergents, wetting agents, emulsifiers, fo ...

s, then processes incorporating a olefin metathesis

Olefin metathesis is an organic reaction that entails the redistribution of fragments of alkenes (olefins) by the scission and regeneration of carbon-carbon double bonds. Because of the relative simplicity of olefin metathesis, it often creat ...

step, such as the Shell higher olefin process

The Shell higher olefin process (SHOP) is a chemical process for the production of linear alpha olefins via ethylene oligomerization and olefin metathesis invented and exploited by Royal Dutch Shell.''Industrial Organic Chemistry'', Klaus Weisserm ...

are important.

Olefin metathesis is also used commercially for the interconversion of ethylene and 2-butene to propylene. Rhenium- and molybdenum-containing heterogeneous catalysis

In chemistry, heterogeneous catalysis is catalysis where the phase of catalysts differs from that of the reactants or products. The process contrasts with homogeneous catalysis where the reactants, products and catalyst exist in the same phase. ...

are used in this process:

:CH2=CH2 + CH3CH=CHCH3 → 2 CH2=CHCH3

Transition metal catalyzed hydrovinylation is another important alkene synthesis process starting from alkene itself. It involves the addition of a hydrogen and a vinyl group (or an alkenyl group) across a double bond.

From alkynes

Reduction ofalkyne

\ce

\ce

Acetylene

\ce

\ce

\ce

Propyne

\ce

\ce

\ce

\ce

1-Butyne

In organic chemistry, an alkyne is an unsaturated hydrocarbon containing at least one carbon—carbon triple bond. The simplest acyclic alkynes with only one triple bond and no ...

s is a useful method for the stereoselective synthesis of disubstituted alkenes. If the ''cis''-alkene is desired, hydrogenation

Hydrogenation is a chemical reaction between molecular hydrogen (H2) and another compound or element, usually in the presence of a catalyst such as nickel, palladium or platinum. The process is commonly employed to reduce or saturate org ...

in the presence of Lindlar's catalyst

A Lindlar catalyst is a heterogeneous catalyst that consists of palladium deposited on calcium carbonate or barium sulfate which is then poisoned with various forms of lead or sulfur. It is used for the hydrogenation of alkynes to alkenes (i.e. w ...

(a heterogeneous catalyst that consists of palladium deposited on calcium carbonate and treated with various forms of lead) is commonly used, though hydroboration followed by hydrolysis provides an alternative approach. Reduction of the alkyne by sodium

Sodium is a chemical element with the symbol Na (from Latin ''natrium'') and atomic number 11. It is a soft, silvery-white, highly reactive metal. Sodium is an alkali metal, being in group 1 of the periodic table. Its only stable ...

metal in liquid ammonia

Ammonia is an inorganic compound of nitrogen and hydrogen with the formula . A stable binary hydride, and the simplest pnictogen hydride, ammonia is a colourless gas with a distinct pungent smell. Biologically, it is a common nitrogeno ...

gives the ''trans''-alkene.

For the preparation multisubstituted alkenes, carbometalation of alkynes can give rise to a large variety of alkene derivatives.

Rearrangements and related reactions

Alkenes can be synthesized from other alkenes viarearrangement reaction

In organic chemistry, a rearrangement reaction is a broad class of organic reactions where the carbon skeleton of a molecule is rearranged to give a structural isomer of the original molecule. Often a substituent moves from one atom to another at ...

s. Besides olefin metathesis

Olefin metathesis is an organic reaction that entails the redistribution of fragments of alkenes (olefins) by the scission and regeneration of carbon-carbon double bonds. Because of the relative simplicity of olefin metathesis, it often creat ...

(described above), many pericyclic reaction

In organic chemistry, a pericyclic reaction is the type of organic reaction wherein the transition state of the molecule has a cyclic geometry, the reaction progresses in a concerted fashion, and the bond orbitals involved in the reaction overlap ...

s can be used such as the ene reaction

In organic chemistry, the ene reaction (also known as the Alder-ene reaction by its discoverer Kurt Alder in 1943) is a chemical reaction between an alkene with an allylic hydrogen (the ene) and a compound containing a multiple bond (the enophile ...

and the Cope rearrangement.

In the Diels–Alder reaction

In organic chemistry, the Diels–Alder reaction is a chemical reaction between a Conjugated system, conjugated diene and a substituted alkene, commonly termed the Diels–Alder reaction#The dienophile, dienophile, to form a substituted cyclohexe ...

, a cyclohexene derivative is prepared from a diene and a reactive or electron-deficient alkene.

IUPAC Nomenclature

Although the nomenclature is not followed widely, according to IUPAC, an alkene is an acyclic hydrocarbon with just one double bond between carbon atoms. Olefins comprise a larger collection of cyclic and acyclic alkenes as well as dienes and polyenes. To form the root of the IUPAC names for straight-chain alkenes, change the ''-an-'' infix of the parent to ''-en-''. For example, CH3-CH3 is thealkane

In organic chemistry

Organic chemistry is a subdiscipline within chemistry involving the science, scientific study of the structure, properties, and reactions of organic compounds and organic materials, i.e., matter in its various forms tha ...

''ethANe''. The name of CH2=CH2 is therefore ''ethENe''.

For straight-chain alkenes with 4 or more carbon atoms, that name does not completely identify the compound. For those cases, and for branched acyclic alkenes, the following rules apply:

# Find the longest carbon chain in the molecule. If that chain does not contain the double bond, name the compound according to the alkane naming rules. Otherwise:

# Number the carbons in that chain starting from the end that is closest to the double bond.

# Define the location ''k'' of the double bond as being the number of its first carbon.

# Name the side groups (other than hydrogen) according to the appropriate rules.

# Define the position of each side group as the number of the chain carbon it is attached to.

# Write the position and name of each side group.

# Write the names of the alkane with the same chain, replacing the "-ane" suffix by "''k''-ene".

The position of the double bond is often inserted before the name of the chain (e.g. "2-pentene"), rather than before the suffix ("pent-2-ene").

The positions need not be indicated if they are unique. Note that the double bond may imply a different chain numbering than that used for the corresponding alkane: C–– is "2,2-dimethyl pentane", whereas C–= is "3,3-dimethyl 1-pentene".

More complex rules apply for polyenes and cycloalkenes.

''Cis''–''trans'' isomerism

If the double bond of an acyclic mono-ene is not the first bond of the chain, the name as constructed above still does not completely identify the compound, because of ''cis''–''trans'' isomerism. Then one must specify whether the two single C–C bonds adjacent to the double bond are on the same side of its plane, or on opposite sides. For monoalkenes, the configuration is often indicated by the prefixes ''cis''- (fromLatin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power ...

"on this side of") or ''trans''- ("across", "on the other side of") before the name, respectively; as in ''cis''-2-pentene or ''trans''-2-butene.

More generally, ''cis''–''trans'' isomerism will exist if each of the two carbons of in the double bond has two different atoms or groups attached to it. Accounting for these cases, the IUPAC recommends the more general E–Z notation, instead of the ''cis'' and ''trans'' prefixes. This notation considers the group with highest CIP priority in each of the two carbons. If these two groups are on opposite sides of the double bond's plane, the configuration is labeled ''E'' (from the German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

**Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ger ...

''entgegen'' meaning "opposite"); if they are on the same side, it is labeled ''Z'' (from German ''zusammen'', "together"). This labeling may be taught with mnemonic "''Z'' means 'on ze zame zide'".John E. McMurry (2014): Organic Chemistry with Biological Applications

'; 3rd edition. 1224 pages.

Groups containing C=C double bonds

IUPAC recognizes two names for hydrocarbon groups containing carbon–carbon double bonds, thevinyl group

In organic chemistry, a vinyl group (abbr. Vi; IUPAC name: ethenyl group) is a functional group with the formula . It is the ethylene (IUPAC name: ethene) molecule () with one fewer hydrogen atom. The name is also used for any compound contai ...

and the allyl

In organic chemistry, an allyl group is a substituent with the structural formula , where R is the rest of the molecule. It consists of a methylene bridge () attached to a vinyl group (). The name is derived from the scientific name for garlic, ...

group.

See also

* Alpha-olefin * Annulene *Aromatic hydrocarbon

Aromatic compounds, also known as "mono- and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons", are organic compounds containing one or more aromatic rings. The parent member of aromatic compounds is benzene. The word "aromatic" originates from the past grou ...

("Arene")

* Dendralene A dendralene is a discrete acyclic cross-conjugated polyene. The simplest dendralene is buta-1,3-diene (1) or endralene followed by endralene (2), endralene (3) and endralene (4) and so forth. endralene (butadiene) is the only one not cross- ...

* Nitroalkene

* Radialene

Nomenclature links

* Rule A-3. Unsaturated Compounds and Univalent RadicalIUPAC Blue Book. * Rule A-4. Bivalent and Multivalent Radical

IUPAC Blue Book. * Rules A-11.3, A-11.4, A-11.5 Unsaturated monocyclic hydrocarbons and substituent

IUPAC Blue Book. * Rule A-23. Hydrogenated Compounds of Fused Polycyclic Hydrocarbon

IUPAC Blue Book.

References

{{Authority control Alkenes,