The Algerian War, also known as the Algerian Revolution or the Algerian War of Independence,

[( ar, الثورة الجزائرية '; '' ber, Tagrawla Tadzayrit''; french: Guerre d'Algérie or ')] and sometimes in Algeria as the War of 1 November, was fought between

France and the Algerian

National Liberation Front (french: Front de Libération Nationale – FLN) from 1954 to 1962, which led to

Algeria winning its independence from France.

An important

decolonization war

Wars of national liberation or national liberation revolutions are conflicts fought by nations to gain independence. The term is used in conjunction with wars against foreign powers (or at least those perceived as foreign) to establish separat ...

, it was a complex conflict characterized by

guerrilla warfare

Guerrilla warfare is a form of irregular warfare in which small groups of combatants, such as paramilitary personnel, armed civilians, or Irregular military, irregulars, use military tactics including ambushes, sabotage, Raid (military), raids ...

and war crimes. The conflict also became a

civil war between the different communities and within the communities. The war took place mainly on the territory of

Algeria, with repercussions in

metropolitan France.

Effectively started by members of the

National Liberation Front (FLN) on 1 November 1954, during the ("Red

All Saints' Day"), the conflict led to serious political crises in France, causing the fall of the

Fourth Republic (1946–58), to be replaced by the

Fifth Republic with a strengthened presidency. The brutality of the methods employed by the French forces failed to

win hearts and minds __NOTOC__

Winning hearts and minds is a concept occasionally expressed in the resolution of war, insurgency, and other conflicts, in which one side seeks to prevail not by the use of superior force, but by making emotional or intellectual appeals ...

in Algeria, alienated support in metropolitan France, and discredited French prestige abroad.

As the war dragged on, the French public slowly turned against it

and many of France's key allies, including the United States, switched from supporting France to abstaining in the UN debate on Algeria.

After major demonstrations in

Algiers

Algiers ( ; ar, الجزائر, al-Jazāʾir; ber, Dzayer, script=Latn; french: Alger, ) is the capital and largest city of Algeria. The city's population at the 2008 Census was 2,988,145Census 14 April 2008: Office National des Statistiques ...

and several other cities in favor of independence (1960)

and a United Nations resolution recognizing the right to independence,

Charles de Gaulle

Charles André Joseph Marie de Gaulle (; ; (commonly abbreviated as CDG) 22 November 18909 November 1970) was a French army officer and statesman who led Free France against Nazi Germany in World War II and chaired the Provisional Government ...

, the first

president of the Fifth Republic, decided to open a series of negotiations with the FLN. These concluded with the signing of the

Évian Accords in March 1962. A

referendum took place on 8 April 1962 and the French electorate approved the Évian Accords. The final result was 91% in favor of the ratification of this agreement

and on 1 July, the Accords were subject to a

second referendum in Algeria, where 99.72% voted for independence and just 0.28% against.

The planned French withdrawal led to a state crisis. This included various

assassination

Assassination is the murder of a prominent or important person, such as a head of state, head of government, politician, world leader, member of a royal family or CEO. The murder of a celebrity, activist, or artist, though they may not have ...

attempts on de Gaulle as well as some attempts at

military coups. Most of the former were carried out by the (OAS), an underground organization formed mainly from French military personnel supporting a French Algeria, which committed a large number of bombings and murders both in Algeria and in the homeland to stop the planned independence.

The war caused the deaths of between 300,000 and 1,500,000 Algerians,

[ 25,600 French soldiers,][ and 6,000 Europeans. War crimes commited during the war included massacres of civilians, rape, and torture; the French destroyed over 8,000 villages and relocated over 2 million Algerians to concentration camps.]agreement Agreement may refer to:

Agreements between people and organizations

* Gentlemen's agreement, not enforceable by law

* Trade agreement, between countries

* Consensus, a decision-making process

* Contract, enforceable in a court of law

** Meeting of ...

between French and Algerian authorities declared that no actions could be taken against them. However, the Harkis in particular, having served as auxiliaries with the French army, were regarded as traitors and many were murdered by the FLN or by lynch mobs, often after being abducted and tortured.[ About 90,000 managed to flee to France, some with help from their French officers acting against orders, and today they and their descendants form a significant part of the Algerian-French population.

]

Background

Conquest of Algeria

On the pretext of a slight to their consul, the French invaded Algeria in 1830.

On the pretext of a slight to their consul, the French invaded Algeria in 1830.[ Directed by Marshall Bugeaud, who became the first ]Governor-General of Algeria

In 1830, in the days before the outbreak of the July Revolution against the Bourbon Restoration in France, the conquest of Algeria was initiated by Charles X as an attempt to increase his popularity amongst the French people. The invasion b ...

, the conquest was violent and marked by a "scorched earth

A scorched-earth policy is a military strategy that aims to destroy anything that might be useful to the enemy. Any assets that could be used by the enemy may be targeted, which usually includes obvious weapons, transport vehicles, communi ...

" policy designed to reduce the power of the native rulers, the Dey, including massacres, mass rapes and other atrocities.[ (quoting Alexis de Tocqueville, ''Travail sur l'Algérie'' in ''Œuvres complètes'', Paris, Gallimard, Bibliothèque de la Pléiade, 1991, pp 704 and 705.] Between 500,000 and 1,000,000, from approximately 3 million Algerians, were killed in the first three decades of the conquest.departments

Department may refer to:

* Departmentalization, division of a larger organization into parts with specific responsibility

Government and military

*Department (administrative division), a geographical and administrative division within a country, ...

: Alger, Oran

Oran ( ar, وَهران, Wahrān) is a major coastal city located in the north-west of Algeria. It is considered the second most important city of Algeria after the capital Algiers, due to its population and commercial, industrial, and cultural ...

and Constantine. Many French and other Europeans (Spanish, Italians, Maltese and others) later settled in Algeria.

Under the Second Empire (1852–1871), the ''Code de l'indigénat

In communications and information processing, code is a system of rules to convert information—such as a letter, word, sound, image, or gesture—into another form, sometimes shortened or secret, for communication through a communication c ...

'' (Indigenous Code) was implemented by the ''sénatus-consulte

A ( French translation of la, senatus consultum, lit=decree of the senate) was a feature of French law during the French Consulate (1799–1804), First French Empire (1804–1814, 1815) and Second French Empire (1852–1870).

Consulate and Fir ...

'' of 14 July 1865. It allowed Muslims to apply for full French citizenship, a measure that few took since it involved renouncing the right to be governed by ''sharia

Sharia (; ar, شريعة, sharīʿa ) is a body of religious law that forms a part of the Islamic tradition. It is derived from the religious precepts of Islam and is based on the sacred scriptures of Islam, particularly the Quran and the H ...

'' law in personal matters and was widely considered to be apostasy. Its first article stipulated:

The indigenous Muslim is French; however, he will continue to be subjected to Muslim law. He may be admitted to serve in the army (armée de terre) and the navy (armée de mer). He may be called to functions and civil employment in Algeria. He may, on his demand, be admitted to enjoy the rights of a French citizen; in this case, he is subjected to the political and civil laws of France.

Prior to 1870, fewer than 200 demands were registered by Muslims and 152 by Jewish Algerians.[le code de l'indigénat dans l'Algérie coloniale](_blank)

, '' Human Rights League'' (LDH), March 6, 2005 – URL accessed on January 17, 2007 The 1865 decree was then modified by the 1870 Crémieux Decree, which granted French nationality to Jews living in one of the three Algerian departments. In 1881, the ''Code de l'Indigénat'' made the discrimination official by creating specific penalties for ''indigènes'' and organising the seizure or appropriation of their lands.

Algerian Nationalism

Both Muslim and European Algerians took part in World War II and fought for France. Algerian Muslims served as '' tirailleurs'' (such regiments were created as early as 1842) and spahis; and French settlers as Zouaves or Chasseurs d'Afrique. US President Woodrow Wilson's 1918 Fourteen Points had the fifth read: "A free, open-minded, and absolutely impartial adjustment of all colonial claims, based upon a strict observance of the principle that in determining all such questions of sovereignty the interests of the populations concerned must have equal weight with the equitable claims of the government whose title is to be determined." Some Algerian intellectuals, dubbed ''oulémas

In Islam, the ''ulama'' (; ar, علماء ', singular ', "scholar", literally "the learned ones", also spelled ''ulema''; feminine: ''alimah'' ingularand ''aalimath'' lural are the guardians, transmitters, and interpreters of religious ...

'', began to nurture the desire for independence or, at the very least, autonomy and self-rule.

Within that context, a grandson of Abd el-Kadir spearheaded the resistance against the French in the first half of the 20th century and was a member of the directing committee of the French Communist Party. In 1926, he founded the '' Étoile Nord-Africaine'' ("North African Star"), to which Messali Hadj, also a member of the Communist Party and of its affiliated trade union, the Confédération générale du travail unitaire (CGTU), joined the following year.

The North African Star broke from the Communist Party in 1928, before being dissolved in 1929 at Paris's demand. Amid growing discontent from the Algerian population, the Third Republic (1871–1940) acknowledged some demands, and the Popular Front initiated the Blum-Viollette proposal in 1936, which was supposed to enlighten the Indigenous Code by giving French citizenship to a small number of Muslims. The ''pieds-noirs

The ''Pieds-Noirs'' (; ; ''Pied-Noir''), are the people of French and other European descent who were born in Algeria during the period of French rule from 1830 to 1962; the vast majority of whom departed for mainland France as soon as Alger ...

'' (Algerians of European origin) violently demonstrated against it and the North African Party also opposed it, leading to its abandonment. The pro-independence party was dissolved in 1937, and its leaders were charged with the illegal reconstitution of a dissolved league, leading to Messali Hadj's 1937 founding of the ''Parti du peuple algérien The Algerian People's Party (in French, Parti du Peuple Algerien PPA), was a successor organization of the North African Star (''Étoile Nord-Africaine''), led by veteran Algerian nationalist Messali Hadj. It was formed on March 11, 1937. In 1936, ...

'' (Algerian People's Party, PPA), which, no longer espoused full independence but only extensive autonomy. This new party was dissolved in 1939. Under Vichy France, the French State attempted to abrogate the Crémieux Decree to suppress the Jews' French citizenship, but the measure was never implemented.

On the other hand, the nationalist leader Ferhat Abbas founded the Algerian Popular Union (''Union populaire algérienne'') in 1938. In 1943, Abbas wrote the Algerian People's Manifesto (''Manifeste du peuple algérien''). Arrested after the Sétif massacre of May 8, 1945, when the French Army and pieds-noirs mobs killed between 6,000 and 30,000 Algerians,[ Abbas founded the Democratic Union of the Algerian Manifesto (UDMA) in 1946 and was elected as a deputy. Founded in 1954, the National Liberation Front (FLN) created an armed wing, the '' Armée de Libération Nationale'' (National Liberation Army) to engage in an armed struggle against French authority. Many Algerian soldiers served for the French Army in the French Indochina War had strong sympathy to the Vietnamese fighting against France and took up their experience to support the ALN.

France, which had just lost French Indochina, was determined not to lose the next colonial war, particularly in its oldest and nearest major colony, which was regarded as a part of Metropolitan France (rather than a colony), by French law.

]

War chronology

Beginning of hostilities

In the early morning hours of 1 November 1954, FLN ''maquisards'' (guerrillas) attacked military and civilian targets throughout Algeria in what became known as the ''

In the early morning hours of 1 November 1954, FLN ''maquisards'' (guerrillas) attacked military and civilian targets throughout Algeria in what became known as the ''Toussaint Rouge

(, "Red All Saints' Day"), also known as ("Bloody All-Saints' Day") is the name given to a series of 70 attacks committed by militant members of the Algerian National Liberation Front (FLN) that took place on 1 November 1954—the Catholic fes ...

'' (Red All-Saints' Day). From Cairo, the FLN broadcast the declaration of 1 November 1954

The Declaration of 1 November 1954 is the first independentist appeal addressed by the National Liberation Front (FLN) to the Algerian people, marking the start of the Algerian Revolution and the armed action of the National Liberation Army (A ...

written by the journalist Mohamed Aïchaoui calling on Muslims in Algeria to join in a national struggle for the "restoration of the Algerian state – sovereign, democratic and social – within the framework of the principles of Islam." It was the reaction of Premier Pierre Mendès France ( Radical-Socialist Party), who only a few months before had completed the liquidation of France's tete empire in Indochina, which set the tone of French policy for five years. He declared in the National Assembly, "One does not compromise when it comes to defending the internal peace of the nation, the unity and integrity of the Republic. The Algerian departments are part of the French Republic. They have been French for a long time, and they are irrevocably French. ... Between them and metropolitan France there can be no conceivable secession." At first, and despite the Sétif massacre of 8 May 1945, and the pro-Independence struggle before World War II, most Algerians were in favor of a relative status-quo. While Messali Hadj had radicalized by forming the FLN, Ferhat Abbas maintained a more moderate, electoral strategy. Fewer than 500 ''fellaghas The ''Fellagha'', an Arabic word literally meaning "bandits" (الفلاقة, singular الفلاق), refers to groups of armed militants affiliated with anti-colonial movements in French North Africa. It most often is used to refer to armed Alge ...

'' (pro-Independence fighters) could be counted at the beginning of the conflict.["Alger-Bagdad", account of Yves Boisset's film documentary, '' La Bataille d'Algers'' (2006), in '' Le Canard enchaîné'', January 10, 2007, n°4498, p.7] The Algerian population radicalized itself in particular because of the terrorist acts of French-sponsored ''Main Rouge ''La Main Rouge'' ( en, The Red Hand) was a French terrorist organization operated by the French foreign intelligence agency ( External Documentation and Counter-Espionage Service), or SDECE, in the 1950s. Its purpose was to eliminate the supporte ...

'' (Red Hand) group, which targeted anti-colonialists in all of the Maghreb region (Morocco, Tunisia and Algeria), killing, for example, Tunisian activist Farhat Hached in 1952.

FLN

The FLN uprising presented nationalist groups with the question of whether to adopt armed revolt as the main course of action. During the first year of the war, Ferhat Abbas's Democratic Union of the Algerian Manifesto (UDMA), the ulema, and the Algerian Communist Party (PCA) maintained a friendly neutrality toward the FLN. The communists, who had made no move to cooperate in the uprising at the start, later tried to infiltrate the FLN, but FLN leaders publicly repudiated the support of the party. In April 1956, Abbas flew to Cairo, where he formally joined the FLN. This action brought in many ''évolués'' who had supported the UDMA in the past. The

The FLN uprising presented nationalist groups with the question of whether to adopt armed revolt as the main course of action. During the first year of the war, Ferhat Abbas's Democratic Union of the Algerian Manifesto (UDMA), the ulema, and the Algerian Communist Party (PCA) maintained a friendly neutrality toward the FLN. The communists, who had made no move to cooperate in the uprising at the start, later tried to infiltrate the FLN, but FLN leaders publicly repudiated the support of the party. In April 1956, Abbas flew to Cairo, where he formally joined the FLN. This action brought in many ''évolués'' who had supported the UDMA in the past. The AUMA

The Adult Use of Marijuana Act (AUMA) (Proposition 64) was a 2016 voter initiative to legalize cannabis in California. The full name is the Control, Regulate and Tax Adult Use of Marijuana Act. The initiative passed with 57% voter approval and be ...

also threw the full weight of its prestige behind the FLN. Bendjelloul and the pro-integrationist moderates had already abandoned their efforts to mediate between the French and the rebels.

After the collapse of the MTLD, the veteran nationalist Messali Hadj formed the leftist

Left-wing politics describes the range of political ideologies that support and seek to achieve social equality and egalitarianism, often in opposition to social hierarchy. Left-wing politics typically involve a concern for those in soci ...

Mouvement National Algérien (MNA), which advocated a policy of violent revolution and total independence similar to that of the FLN, but aimed to compete with that organisation. The Armée de Libération Nationale (ALN), the military wing of the FLN, subsequently wiped out the MNA guerrilla operation in Algeria, and Messali Hadj's movement lost what little influence it had had there. However, the MNA retained the support of many Algerian workers in France through the Union Syndicale des Travailleurs Algériens

Union commonly refers to:

* Trade union, an organization of workers

* Union (set theory), in mathematics, a fundamental operation on sets

Union may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment

Music

* Union (band), an American rock group

** ''U ...

(the Union of Algerian Workers). The FLN also established a strong organization in France to oppose the MNA. The "Café wars

A coffeehouse, coffee shop, or café is an establishment that primarily serves coffee of various types, notably espresso, latte, and cappuccino. Some coffeehouses may serve cold drinks, such as iced coffee and iced tea, as well as other non-ca ...

", resulting in nearly 5,000 deaths, were waged in France between the two rebel groups throughout the years of the War of Independence.

On the political front, the FLN worked to persuade—and to coerce—the Algerian masses to support the aims of the independence movement through contributions. FLN-influenced labor unions, professional associations, and students' and women's organizations were created to lead opinion in diverse segments of the population, but here too, violent coercion was widely used. Frantz Fanon, a psychiatrist from Martinique who became the FLN's leading political theorist, provided a sophisticated intellectual justification for the use of violence in achieving national liberation. From Cairo, Ahmed Ben Bella ordered the liquidation of potential ''interlocuteurs valables'', those independent representatives of the

On the political front, the FLN worked to persuade—and to coerce—the Algerian masses to support the aims of the independence movement through contributions. FLN-influenced labor unions, professional associations, and students' and women's organizations were created to lead opinion in diverse segments of the population, but here too, violent coercion was widely used. Frantz Fanon, a psychiatrist from Martinique who became the FLN's leading political theorist, provided a sophisticated intellectual justification for the use of violence in achieving national liberation. From Cairo, Ahmed Ben Bella ordered the liquidation of potential ''interlocuteurs valables'', those independent representatives of the Muslim

Muslims ( ar, المسلمون, , ) are people who adhere to Islam, a monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God of Abrah ...

community acceptable to the French through whom a compromise or reforms within the system might be achieved.

As the FLN campaign of influence spread through the countryside, many European farmers in the interior (called ''Pieds-Noirs

The ''Pieds-Noirs'' (; ; ''Pied-Noir''), are the people of French and other European descent who were born in Algeria during the period of French rule from 1830 to 1962; the vast majority of whom departed for mainland France as soon as Alger ...

''), many of whom lived on lands taken from Muslim communities during the nineteenth century, sold their holdings and sought refuge in Algiers

Algiers ( ; ar, الجزائر, al-Jazāʾir; ber, Dzayer, script=Latn; french: Alger, ) is the capital and largest city of Algeria. The city's population at the 2008 Census was 2,988,145Census 14 April 2008: Office National des Statistiques ...

and other Algerian cities. After a series of bloody, random massacres and bombings by Muslim Algerians in several towns and cities, the French ''Pieds-Noirs'' and urban French population began to demand that the French government engage in sterner countermeasures, including the proclamation of a state of emergency

A state of emergency is a situation in which a government is empowered to be able to put through policies that it would normally not be permitted to do, for the safety and protection of its citizens. A government can declare such a state du ...

, capital punishment for political crimes, denunciation of all separatists, and most ominously, a call for 'tit-for-tat' reprisal operations by police, military, and para-military forces. '' Colon'' vigilante units, whose unauthorized activities were conducted with the passive cooperation of police authorities, carried out ''ratonnades'' (literally, ''rat-hunts'', ''raton'' being a racist term for denigrating Muslim Algerians) against suspected FLN members of the Muslim community.

By 1955, effective political action groups within the Algerian colonial community succeeded in convincing many of the Governors General sent by Paris that the military was not the way to resolve the conflict. A major success was the conversion of Jacques Soustelle, who went to Algeria as governor general in January 1955 determined to restore peace. Soustelle, a one-time leftist and by 1955 an ardent Gaullist, began an ambitious reform program (the Soustelle Plan The Soustelle Plan was a reform program envisioned by Jacques Soustelle, then governor general of Algeria, for the improvement of several administrative, political, social and economic works which emphasized the integration of Muslim Algerians with ...

) aimed at improving economic conditions among the Muslim population.

After the Philippeville massacre

The FLN adopted tactics similar to those of nationalist groups in Asia, and the French did not realize the seriousness of the challenge they faced until 1955, when the FLN moved into urbanized areas. "An important watershed in the War of Independence was the massacre of Pieds-Noirs civilians by the FLN near the town of Philippeville (now known as Skikda) in August 1955. Before this operation, FLN policy was to attack only military and government-related targets. The commander of the Constantine ''wilaya''/region, however, decided a drastic escalation was needed. The killing by the FLN and its supporters of 123 people, including 71 French,[Number given by the](_blank)

Préfecture du Gers

Gers (; oc, Gers or , ) is a department in the region of Occitania, Southwestern France. Named after the Gers River, its inhabitants are called the ''Gersois'' and ''Gersoises'' in French. In 2019, it had a population of 191,377. , French governmental site – URL accessed on February 17, 2007 including old women and babies, shocked Jacques Soustelle into calling for more repressive measures against the rebels. The French authorities stated that 1,273 guerrillas died in what Soustelle admitted were "severe" reprisals. The FLN subsequently claimed that 12,000 Muslims were killed.[ Soustelle's repression was an early cause of the Algerian population's rallying to the FLN.]Algerian Assembly

Algerian may refer to:

* Something of, or related to Algeria

* Algerian people, a person or people from Algeria, or of Algerian descent

* Algerian cuisine

* Algerian culture

* Algerian Islamic reference

* Algerian Mus'haf

* Algerian (solitaire)

* A ...

. Lacoste saw the assembly, which was dominated by ''pieds-noirs'', as hindering the work of his administration, and he undertook the rule of Algeria by decree. He favored stepping up French military operations and granted the army exceptional police powers—a concession of dubious legality under French law—to deal with the mounting political violence. At the same time, Lacoste proposed a new administrative structure to give Algeria some autonomy and a decentralized government. Whilst remaining an integral part of France, Algeria was to be divided into five districts, each of which would have a territorial assembly elected from a single slate of candidates. Until 1958, deputies representing Algerian districts were able to delay the passage of the measure by the National Assembly of France

The National Assembly (french: link=no, italics=set, Assemblée nationale; ) is the lower house of the bicameral French Parliament under the Fifth Republic, the upper house being the Senate (). The National Assembly's legislators are known a ...

.

In August and September 1956, the leadership of the FLN guerrillas operating within Algeria (popularly known as "internals") met to organize a formal policy-making body to synchronize the movement's political and military activities. The highest authority of the FLN was vested in the thirty-four member National Council of the Algerian Revolution

National may refer to:

Common uses

* Nation or country

** Nationality – a ''national'' is a person who is subject to a nation, regardless of whether the person has full rights as a citizen

Places in the United States

* National, Maryland, ce ...

(Conseil National de la Révolution Algérienne, CNRA), within which the five-man Committee of Coordination and Enforcement (''Comité de Coordination et d'Exécution'', CCE) formed the executive. The leadership of the regular FLN forces based in Tunisia and Morocco ("externals"), including Ben Bella, knew the conference was taking place but by chance or design on the part of the "internals" were unable to attend.

In October 1956, the French Air Force

The French Air and Space Force (AAE) (french: Armée de l'air et de l'espace, ) is the air and space force of the French Armed Forces. It was the first military aviation force in history, formed in 1909 as the , a service arm of the French Army; ...

intercepted a Moroccan DC-3 bound for Tunis, carrying Ahmed Ben Bella, Mohammed Boudiaf

Mohamed Boudiaf (23 June 1919 – 29 June 1992, ar, محمد بوضياف; ALA-LC: ''Muḥammad Bū-Ḍiyāf''), also called Si Tayeb el Watani, was an Algerian political leader and one of the founders of the revolutionary National Liberat ...

, Mohamed Khider

Muhammad was an Islamic prophet and a religious and political leader who preached and established Islam.

Muhammad and variations may also refer to:

*Muhammad (name), a given name and surname, and list of people with the name and its variations

...

and Hocine Aït Ahmed

Hocine Aït Ahmed ( ar, حسين آيت أحمد; 20 August 1926 – 23 December 2015) was an Algerian politician. He was founder and leader until 2009 of the historical political opposition in Algeria.

Life

Aït Ahmed was born at Aï ...

, and forced it to land in Algiers. Lacoste had the FLN external political leaders arrested and imprisoned for the duration of the war. This action caused the remaining rebel leaders to harden their stance.

France opposed Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser

Gamal Abdel Nasser Hussein, . (15 January 1918 – 28 September 1970) was an Egyptian politician who served as the second president of Egypt from 1954 until his death in 1970. Nasser led the Egyptian revolution of 1952 and introduced far-re ...

's material and political assistance to the FLN, which some French analysts believed was the revolution's main sustenance. This attitude was a factor in persuading France to participate in the November 1956 attempt to seize the Suez Canal

The Suez Canal ( arz, قَنَاةُ ٱلسُّوَيْسِ, ') is an artificial sea-level waterway in Egypt, connecting the Mediterranean Sea to the Red Sea through the Isthmus of Suez and dividing Africa and Asia. The long canal is a popular ...

during the Suez Crisis

The Suez Crisis, or the Second Arab–Israeli war, also called the Tripartite Aggression ( ar, العدوان الثلاثي, Al-ʿUdwān aṯ-Ṯulāṯiyy) in the Arab world and the Sinai War in Israel,Also known as the Suez War or 1956 Wa ...

.

During 1957, support for the FLN weakened as the breach between the internals and externals widened. To halt the drift, the FLN expanded its executive committee to include Abbas, as well as imprisoned political leaders such as Ben Bella. It also convinced communist and Arab members of the United Nations (UN) to put diplomatic pressure on the French government to negotiate a cease-fire. In 1957, it became common knowledge in France that the French Army was routinely using torture to extract information from suspected FLN members.[ Another case that attracted much media attention was the murder of Maurice Audin, a member of the outlawed Algerian Communist party, mathematics professor at the University of Algiers and a suspected FLN member whom the French Army arrested in June 1957.][ Audin was tortured and killed and his body was never found.][ As Audin was French rather than Algerian, his "disappearance" while in the custody of the French Army led to the case becoming a ''cause célèbre'' as his widow aided by the historian Pierre Vidal-Naquet determinedly sought to have the men responsible for her husband's death prosecuted.][

Existentialist writer, philosopher and playwright Albert Camus, native of Algiers, tried unsuccessfully to persuade both sides to at least leave civilians alone, writing editorials against the use of torture in '']Combat

Combat ( French for ''fight'') is a purposeful violent conflict meant to physically harm or kill the opposition. Combat may be armed (using weapons) or unarmed ( not using weapons). Combat is sometimes resorted to as a method of self-defense, or ...

'' newspaper. The FLN considered him a fool, and some ''Pieds-Noirs'' considered him a traitor. Nevertheless, in his speech when he received the Nobel Prize in Literature

)

, image = Nobel Prize.png

, caption =

, awarded_for = Outstanding contributions in literature

, presenter = Swedish Academy

, holder = Annie Ernaux (2022)

, location = Stockholm, Sweden

, year = 1901

, ...

, Camus said that when faced with a radical choice he would eventually support his community. This statement made him lose his status among left-wing intellectuals; when he died in 1960 in a car crash, the official thesis of an ordinary accident (a quick open-and-shut case) left more than a few observers doubtful. His widow claimed that Camus, though discreet, was in fact an ardent supporter of French Algeria in the last years of his life.

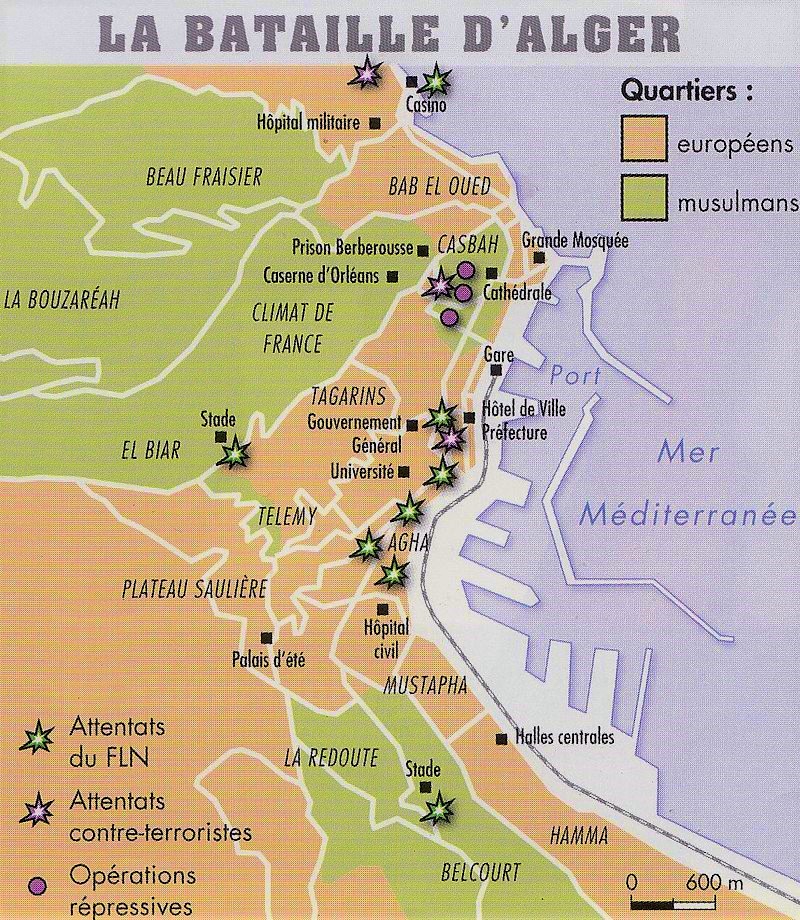

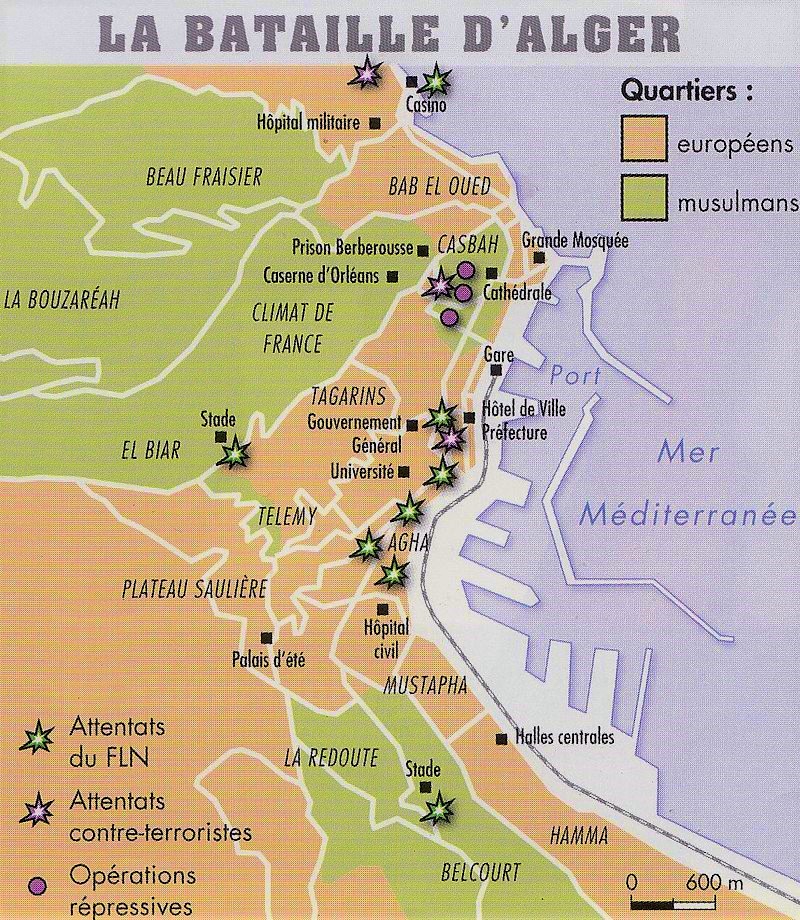

Battle of Algiers

To increase international and domestic French attention to their struggle, the FLN decided to bring the conflict to the cities and to call a nationwide

To increase international and domestic French attention to their struggle, the FLN decided to bring the conflict to the cities and to call a nationwide general strike

A general strike refers to a strike action in which participants cease all economic activity, such as working, to strengthen the bargaining position of a trade union or achieve a common social or political goal. They are organised by large co ...

and also to plant bombs in public places. The most notable instance was the Battle of Algiers, which began on September 30, 1956, when three women, including Djamila Bouhired

Djamila Bouhired ( ar, جميلة بوحيرد, born c. 1935) is an Algerian militant. Bouhired is a nationalist who opposed the French colonial rule of Algeria. She was raised in a middle-class family by a Tunisian mother and an Algerian father ...

and Zohra Drif, simultaneously placed bombs at three sites including the downtown office of Air France. The FLN carried out shootings and bombings in the spring of 1957, resulting in civilian casualties and a crushing response from the authorities.

General Jacques Massu was instructed to use whatever methods deemed necessary to restore order in the city and to find and eliminate terrorists. Using paratroopers, he broke the strike and, in the succeeding months, destroyed the FLN infrastructure in Algiers. But the FLN had succeeded in showing its ability to strike at the heart of French Algeria and to assemble a mass response to its demands among urban Muslims. The publicity given to the brutal methods used by the army to win the Battle of Algiers, including the use of torture, strong movement control and curfew called ''quadrillage'' and where all authority was under the military, created doubt in France about its role in Algeria. What was originally "pacification

Pacification may refer to:

The restoration of peace through a declaration or peace treaty:

*Pacification of Ghent, an alliance of several provinces of the Netherlands signed on November 8, 1576

*Treaty of Berwick (1639), or ''Pacification of Berwi ...

" or a "public order operation" had turned into a colonial war accompanied by torture.

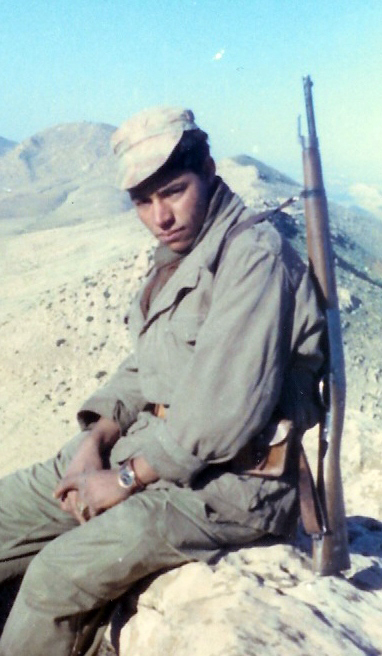

Guerrilla war

During 1956 and 1957, the FLN successfully applied hit-and-run tactics in accordance with guerrilla warfare

Guerrilla warfare is a form of irregular warfare in which small groups of combatants, such as paramilitary personnel, armed civilians, or Irregular military, irregulars, use military tactics including ambushes, sabotage, Raid (military), raids ...

theory. Whilst some of this was aimed at military targets, a significant amount was invested in a terror campaign against those in any way deemed to support or encourage French authority. This resulted in acts of sadistic torture and brutal violence against all, including women and children. Specializing in ambushes and night raids and avoiding direct contact with superior French firepower, the internal forces targeted army patrols, military encampments, police posts, and colonial farms, mines, and factories, as well as transportation and communications facilities. Once an engagement was broken off, the guerrillas merged with the population in the countryside, in accordance with Mao's theories. Kidnapping was commonplace, as were the ritual murder and mutilation of civiliansAurès

, native_name_lang =

, settlement_type = Natural region

, image_skyline = Ras el Aïoun.jpg

, image_alt =

, image_caption = Landscape of the Aurès in Ras el Aïoun

, image_flag ...

, the Kabylie, and other mountainous areas around Constantine and south of Algiers and Oran

Oran ( ar, وَهران, Wahrān) is a major coastal city located in the north-west of Algeria. It is considered the second most important city of Algeria after the capital Algiers, due to its population and commercial, industrial, and cultural ...

. In these places, the FLN established a simple but effective—although frequently temporary—military administration that was able to collect taxes and food and to recruit manpower. But it was never able to hold large, fixed positions.

The loss of competent field commanders both on the battlefield and through defections and political purges created difficulties for the FLN. Moreover, power struggles in the early years of the war split leadership in the wilayat, particularly in the Aurès. Some officers created their own fiefdoms, using units under their command to settle old scores and engage in private wars against military rivals within the FLN.

French counter-insurgency operations

Despite complaints from the military command in Algiers, the French government was reluctant for many months to admit that the Algerian situation was out of control and that what was viewed officially as a pacification operation had developed into a war. By 1956, there were more than 400,000 French troops in Algeria. Although the elite colonial infantry airborne units and the Foreign Legion bore the brunt of offensive counterinsurgency combat operations, approximately 170,000 Muslim Algerians also served in the regular French army, most of them volunteers. France also sent air force and naval units to the Algerian theater, including helicopters. In addition to service as a flying ambulance and cargo carrier, French forces utilized the helicopter for the first time in a ground attack role in order to pursue and destroy fleeing FLN guerrilla units. The American military later used the same helicopter combat methods in the Vietnam War. The French also used napalm.[

The French army resumed an important role in local Algerian administration through the Special Administration Section ('']Section Administrative Spécialisée

Section, Sectioning or Sectioned may refer to:

Arts, entertainment and media

* Section (music), a complete, but not independent, musical idea

* Section (typography), a subdivision, especially of a chapter, in books and documents

** Section sig ...

'', SAS), created in 1955. The SAS's mission was to establish contact with the Muslim population and weaken nationalist influence in the rural areas by asserting the "French presence" there. SAS officers—called ''képis bleus'' (blue caps)—also recruited and trained bands of loyal Muslim irregulars, known as '' harkis''. Armed with shotguns and using guerrilla tactics similar to those of the FLN, the ''harkis'', who eventually numbered about 180,000 volunteers, more than the FLN activists,[Major Gregory D. Peterson, ''The French Experience in Algeria, 1954–62: Blueprint for U.S. Operations in Iraq'', Ft Leavenworth, Kansas: School of Advanced Military Studies, p.33] were an ideal instrument of counterinsurgency warfare.

''Harkis'' were mostly used in conventional formations, either in all-Algerian units commanded by French officers or in mixed units. Other uses included platoon or smaller size units, attached to French battalions, in a similar way as the Kit Carson Scouts by the U.S. in Vietnam. A third use was an intelligence gathering role, with some reported minor pseudo-operations

A false flag operation is an act committed with the intent of disguising the actual source of responsibility and pinning blame on another party. The term "false flag" originated in the 16th century as an expression meaning an intentional misr ...

in support of their intelligence collection. U.S. military expert Lawrence E. Cline

Lawrence may refer to:

Education Colleges and universities

* Lawrence Technological University, a university in Southfield, Michigan, United States

* Lawrence University, a liberal arts university in Appleton, Wisconsin, United States

Preparato ...

stated, "The extent of these pseudo-operations appears to have been very limited both in time and scope. ... The most widespread use of pseudo type operations was during the 'Battle of Algiers' in 1957. The principal French employer of covert agents in Algiers was the Fifth Bureau, the psychological warfare branch. "The Fifth Bureau" made extensive use of 'turned' FLN members, one such network being run by Captain Paul-Alain Leger of the 10th Paras. " Persuaded" to work for the French forces included by the use of torture and threats against their family; these agents "mingled with FLN cadres. They planted incriminating forged documents, spread false rumors of treachery and fomented distrust. ... As a frenzy of throat-cutting and disemboweling broke out among confused and suspicious FLN cadres, nationalist slaughtered nationalist from April to September 1957 and did France's work for her." But this type of operation involved individual operatives rather than organized covert units.

One organized pseudo-guerrilla unit, however, was created in December 1956 by the French DST domestic intelligence agency. The ''Organization of the French Algerian Resistance'' (ORAF), a group of counter-terrorists had as its mission to carry out false flag

A false flag operation is an act committed with the intent of disguising the actual source of responsibility and pinning blame on another party. The term "false flag" originated in the 16th century as an expression meaning an intentional misr ...

terrorist attacks with the aim of quashing any hopes of political compromise. But it seemed that, as in Indochina, "the French focused on developing native guerrilla groups that would fight against the FLN", one of whom fought in the Southern Atlas Mountains

The Atlas Mountains are a mountain range in the Maghreb in North Africa. It separates the Sahara Desert from the Mediterranean Sea and the Atlantic Ocean; the name "Atlantic" is derived from the mountain range. It stretches around through Moroc ...

, equipped by the French Army.[

Late in 1957, General Raoul Salan, commanding the French Army in Algeria, instituted a system of ''quadrillage'' (surveillance using a grid pattern), dividing the country into sectors, each permanently garrisoned by troops responsible for suppressing rebel operations in their assigned territory. Salan's methods sharply reduced the instances of FLN terrorism but tied down a large number of troops in static defense. Salan also constructed a heavily patrolled system of barriers to limit infiltration from Tunisia and Morocco. The best known of these was the Morice Line (named for the French defense minister, ]André Morice

André Morice (11 October 1900, Nantes – 17 January 1990) was a French politician. He represented the Radical Party in the Constituent Assembly elected in 1945, in the Constituent Assembly elected in 1946 and in the National Assembly from 1946 ...

), which consisted of an electrified fence, barbed wire, and mines over a 320-kilometer stretch of the Tunisian border. Despite ruthless clashes during the Battle of the borders, the ALN failed to penetrate these defence lines.

The French military command ruthlessly applied the principle of collective responsibility to villages suspected of sheltering, supplying, or in any way cooperating with the guerrillas. Villages that could not be reached by mobile units were subject to aerial bombardment. FLN guerrillas that fled to caves or other remote hiding places were tracked and hunted down. In one episode, FLN guerrillas who refused to surrender and withdraw from a cave complex were dealt with by French Foreign Legion Pioneer troops, who, lacking flamethrowers or explosives, simply bricked up each cave, leaving the residents to die of suffocation.population transfers

Population transfer or resettlement is a type of mass migration, often imposed by state policy or international authority and most frequently on the basis of ethnicity or religion but also due to Development-induced displacement, economic deve ...

effectively denied the use of remote villages to FLN guerrillas, who had used them as a source of rations and manpower, but also caused significant resentment on the part of the displaced villagers. Relocation's social and economic disruption continued to be felt a generation later. At the same time, the French tried to gain support from the civilian population by providing money, jobs and housing to farmers

Fall of the Fourth Republic

Recurrent cabinet crises focused attention on the inherent instability of the Fourth Republic and increased the misgivings of the army and of the pieds-noirs that the security of Algeria was being undermined by party politics. Army commanders chafed at what they took to be inadequate and incompetent political initiatives by the government in support of military efforts to end the rebellion. The feeling was widespread that another debacle like that of Indochina in 1954 was in the offing and that the government would order another precipitate pullout and sacrifice French honor to political expediency. Many saw in de Gaulle, who had not held office since 1946, the only public figure capable of rallying the nation and giving direction to the French government.

After his time as governor general, Soustelle returned to France to organize support for de Gaulle's return to power, while retaining close ties to the army and the ''pieds-noirs''. By early 1958, he had organized a coup d'état, bringing together dissident army officers and ''pieds-noirs'' with sympathetic Gaullists. An army junta under General Massu seized power in Algiers on the night of May 13, thereafter known as the May 1958 crisis. General Salan assumed leadership of a Committee of Public Safety formed to replace the civil authority and pressed the junta's demands that de Gaulle be named by French president René Coty to head a government of national unity invested with extraordinary powers to prevent the "abandonment of Algeria."

On May 24, French paratroopers from the Algerian corps landed on Corsica

Corsica ( , Upper , Southern ; it, Corsica; ; french: Corse ; lij, Còrsega; sc, Còssiga) is an island in the Mediterranean Sea and one of the 18 regions of France. It is the fourth-largest island in the Mediterranean and lies southeast of ...

, taking the French island in a bloodless action, Opération Corse. Subsequently, preparations were made in Algeria for Operation Resurrection

Operation Resurrection was a planned military operation of the French Army in 1958 that sought to take over the capital of France, Paris, to force the return of Charles de Gaulle to head the government. Masterminded by General Jacques Massu, the o ...

, which had as its objectives the seizure of Paris and the removal of the French government. Resurrection was to be implemented in the event of one of three following scenarios: Were de Gaulle not approved as leader of France by the parliament; were de Gaulle to ask for military assistance to take power; or if it seemed that communist forces were making any move to take power in France. De Gaulle was approved by the French parliament on May 29, by 329 votes against 224, 15 hours before the projected launch of Operation Resurrection. This indicated that the Fourth Republic by 1958 no longer had any support from the French Army in Algeria and was at its mercy even in civilian political matters. This decisive shift in the balance of power in civil-military relations in France in 1958, and the threat of force, was the primary factor in the return of de Gaulle to power in France.

De Gaulle

Many people, regardless of citizenship, greeted de Gaulle's return to power as the breakthrough needed to end the hostilities. On his trip to Algeria on 4 June 1958, de Gaulle calculatedly made an ambiguous and broad emotional appeal to all the inhabitants, declaring, "Je vous ai compris" ("I have understood you"). De Gaulle raised the hopes of the ''pied-noir'' and the professional military, disaffected by the indecisiveness of previous governments, with his exclamation of "Vive l' Algérie française" ("Long live French Algeria") to cheering crowds in Mostaganem. At the same time, he proposed economic, social, and political reforms to improve the situation of the Muslims. Nonetheless, de Gaulle later admitted to having harbored deep pessimism about the outcome of the Algerian situation even then. Meanwhile, he looked for a "third force" among the population of Algeria, uncontaminated by the FLN or the "ultras" (''colon'' extremists), through whom a solution might be found.

De Gaulle immediately appointed a committee to draft a new constitution for France's Fifth Republic, which would be declared early the next year, with which Algeria would be associated but of which it would not form an integral part. All Muslims, including women, were registered for the first time on electoral rolls to participate in a referendum to be held on the new constitution in September 1958.

De Gaulle's initiative threatened the FLN with decreased support among Muslims. In reaction, the FLN set up the Provisional Government of the Algerian Republic (Gouvernement Provisoire de la République Algérienne, GPRA), a government-in-exile headed by Abbas

Abbas may refer to:

People

* Abbas (name), list of people with the name, including:

**Abbas ibn Ali, Popularly known as Hazrat-e-Abbas (brother of Imam Hussayn)

**Abbas ibn Abd al-Muttalib, uncle of Muhammad

** Mahmoud Abbas (born 1935), Palest ...

and based in Tunis. Before the referendum, Abbas lobbied for international support for the GPRA, which was quickly recognized by Morocco, Tunisia, China, and several other African, Arab, and Asian countries, but not by the Soviet Union.

In February 1959, de Gaulle was elected president of the new Fifth Republic. He visited Constantine in October to announce a program to end the war and create an Algeria closely linked to France. De Gaulle's call on the rebel leaders to end hostilities and to participate in elections was met with adamant refusal. "The problem of a cease-fire in Algeria is not simply a military problem", said the GPRA's Abbas. "It is essentially political, and negotiation must cover the whole question of Algeria." Secret discussions that had been underway were broken off.

From 1958 to 1959, the French army won military control in Algeria and was the closest it would be to victory. In late July 1959, during Operation Jumelles, Colonel Bigeard, whose elite paratrooper unit fought at Dien Bien Phu in 1954, told journalist Jean Lartéguy

Jean Lartéguy (5 September 1920 in Maisons-Alfort – 23 February 2011) was the pen name of Jean Pierre Lucien Osty, a French writer, journalist, and former soldier.

Larteguy is credited with first envisioning the " ticking time bomb" sce ...

,

source

During this period in France, however, popular opposition to the conflict was growing, notably in the French Communist Party, then one of the country's strongest political forces, which supported the Algerian Revolution. Thousands of relatives of conscripts and reserve soldiers suffered loss and pain; revelations of torture and the indiscriminate brutality of the army against the Muslim population prompted widespread revulsion, and a significant constituency supported the principle of national liberation. By 1959, it was clear that the status quo was untenable and France could either grant Algeria independence or allow real equality with the Muslims. De Gaulle told an advisor: "If we integrate them, if all the Arabs and the Berbers of Algeria were considered French, how could they be prevented from settling in France, where the living standard is so much higher? My village would no longer be called Colombey-les-Deux-Églises but Colombey-les-Deux-Mosquées".

A Critical Evaluation of Charles De Gaulle's Handling... , 123 Help Me

which he envisioned as leading to majority rule in an Algeria formally associated with France. In Tunis, Abbas acknowledged that de Gaulle's statement might be accepted as a basis for settlement, but the French government refused to recognize the GPRA as the representative of Algeria's Muslim community.

Week of barricades

Convinced that de Gaulle had betrayed them, some units of European volunteers (''Unités Territoriales'') in Algiers led by student leaders

Convinced that de Gaulle had betrayed them, some units of European volunteers (''Unités Territoriales'') in Algiers led by student leaders Pierre Lagaillarde

Pierre Lagaillarde (; Courbevoie, 15 May 1931 – 17 August 2014) was a French politician, and a founder of the '' Organisation armée secrète'' (OAS).

Lagaillarde was a lawyer at Blida in Algeria, a reserve officer of the paratroopers, and a ...

and Jean-Jacques Susini

Jean-Jacques Susini (30 July 1933 – 3 July 2017) was a French political figure, militant and cofounder of the Organisation armée secrète (OAS), a paramilitary organization opposing Algerian independence from France.

Life

Born in Algiers, Fre ...

, café owner Joseph Ortiz, and lawyer Jean-Baptiste Biaggi Jean-Baptiste Biaggi (27 August 1917 – 29 July 2009) was a French politician.

Biaggi was born in Ponce, Puerto Rico, on 27 August 1917. He attended Lycée de Bastia, and before graduating from Faculty of Law of Paris. During World War II, Biaggi ...

staged an insurrection in the Algerian capital starting on 24 January 1960, and known in France as ''La semaine des barricades'' ("the week of barricades"). The ''ultras'' incorrectly believed that they would be supported by General Massu. The insurrection order was given by Colonel Jean Garde of the Fifth Bureau. As the army, police, and supporters stood by, civilian ''pieds-noirs'' threw up barricades in the streets and seized government buildings. General Maurice Challe, responsible for the army in Algeria, declared Algiers under siege, but forbade the troops to fire on the insurgents. Nevertheless, 20 rioters were killed during shooting on Boulevard Laferrière.

In Paris on 29 January 1960, de Gaulle called on his ineffective army to remain loyal and rallied popular support for his Algerian policy in a televised address:

I took, in the name of France, the following decision—the Algerians will have the free choice of their destiny. When, in one way or another – by ceasefire or by complete crushing of the rebels – we will have put an end to the fighting, when, after a prolonged period of appeasement, the population will have become conscious of the stakes and, thanks to us, realised the necessary progress in political, economic, social, educational, and other domains. Then it will be the Algerians who will tell us what they want to be.... Your French of Algeria, how can you listen to the liars and the conspirators who tell you that, if you grant free choice to the Algerians, France and de Gaulle want to abandon you, retreat from Algeria, and deliver you to the rebellion?.... I say to all of our soldiers: your mission comprises neither equivocation nor interpretation. You have to liquidate the rebellious forces, which want to oust France from Algeria and impose on this country its dictatorship of misery and sterility.... Finally, I address myself to France. Well, well, my dear and old country, here we face together, once again, a serious ordeal. In virtue of the mandate that the people have given me and of the national legitimacy, which I have embodied for 20 years, I ask everyone to support me whatever happens.

Most of the Army heeded his call, and the siege of Algiers ended on 1 February with Lagaillarde surrendering to General Challe's command of the French Army in Algeria. The loss of many ''ultra'' leaders who were imprisoned or transferred to other areas did not deter the French Algeria militants. Sent to prison in Paris and then paroled, Lagaillarde fled to Spain. There, with another French army officer, Raoul Salan, who had entered clandestinely

Secrecy is the practice of hiding information from certain individuals or groups who do not have the "need to know", perhaps while sharing it with other individuals. That which is kept hidden is known as the secret.

Secrecy is often controvers ...

, and with Jean-Jacques Susini, he created the Organisation armée secrète (Secret Army Organization, OAS) on December 3, 1960, with the purpose of continuing the fight for French Algeria. Highly organized and well-armed, the OAS stepped up its terrorist activities, which were directed against both Algerians and pro-government French citizens, as the move toward negotiated settlement of the war and self-determination gained momentum. To the FLN rebellion against France were added civil wars between extremists in the two communities and between the ''ultras'' and the French government in Algeria.

Beside Pierre Lagaillarde, Jean-Baptiste Biaggi was also imprisoned, while Alain de Sérigny Alain may refer to:

People

* Alain (given name), common given name, including list of persons and fictional characters with the name

* Alain (surname)

* "Alain", a pseudonym for cartoonist Daniel Brustlein

* Alain, a standard author abbreviation u ...

was arrested, and Joseph Ortiz's FNF dissolved, as well as General Lionel Chassin __TOC__

Lionel may refer to: Name

*Lionel (given name) Places

*Lionel, Lewis, a village in the Outer Hebrides of Scotland

*Lionel Town, Jamaica, a settlement Brands and enterprises

*Lionel, LLC, an American designer and importer of toy trains and mo ...

's MP13. De Gaulle also modified the government, excluding Jacques Soustelle, believed to be too pro-French Algeria, and granting the Minister of Information to Louis Terrenoire, who quit RTF

RTF may refer to:

Organisations

* African Union Regional Task Force, the military operation of the RCI-LRA, 2011–2018.

* Radiodiffusion-Télévision Française, a broadcaster in France, 1949–1964

* Russian Tennis Federation, the national gover ...

(French broadcasting TV). Pierre Messmer

Pierre Joseph Auguste Messmer (; 20 March 191629 August 2007) was a French Gaullist politician. He served as Minister of Armies under Charles de Gaulle from 1960 to 1969 – the longest serving since Étienne François, duc de Choiseul under Lo ...

, who had been a member of the Foreign Legion, was named Minister of Defense, and dissolved the Fifth Bureau, the psychological warfare branch, which had ordered the rebellion. These units had theorized the principles of a counter-revolutionary war

Counterinsurgency (COIN) is "the totality of actions aimed at defeating irregular forces". The Oxford English Dictionary defines counterinsurgency as any "military or political action taken against the activities of guerrillas or revolutionar ...

, including the use of torture. During the Indochina War (1947–54), officers such as Roger Trinquier and Lionel-Max Chassin were inspired by Mao Zedong's strategic doctrine and acquired knowledge of convince the population to support the fight. The officers were initially trained in the ''Centre d'instruction et de préparation à la contre-guérilla

Center or centre may refer to:

Mathematics

*Center (geometry), the middle of an object

* Center (algebra), used in various contexts

** Center (group theory)

** Center (ring theory)

* Graph center, the set of all vertices of minimum eccentricity ...

'' (Arzew). Jacques Chaban-Delmas

Jacques Chaban-Delmas (; 7 March 1915 – 10 November 2000) was a French Gaullist politician. He served as Prime Minister under Georges Pompidou from 1969 to 1972. He was the Mayor of Bordeaux from 1947 to 1995 and a deputy for the Gironde ''d� ...

added to that the ''Centre d'entraînement à la guerre subversive Jeanne-d'Arc

Center or centre may refer to:

Mathematics

*Center (geometry), the middle of an object

* Center (algebra), used in various contexts

** Center (group theory)

** Center (ring theory)

* Graph center, the set of all vertices of minimum eccentricity ...

'' (Center of Training to Subversive War Joan of Arc) in Philippeville, Algeria, directed by Colonel Marcel Bigeard.

The French army officers' uprising was due to a perceived second betrayal by the government, the first having been Indochina (1947–1954). In some aspects the Dien Bien Phu garrison was sacrificed with no metropolitan support, order was given to commanding officer General de Castries to "let the affair die of its own, in serenity" ("''laissez mourir l'affaire d'elle même en sérénité''"Front national pour l'Algérie française

Front may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Films

* ''The Front'' (1943 film), a 1943 Soviet drama film

* '' The Front'', 1976 film

Music

*The Front (band), an American rock band signed to Columbia Records and active in the 1980s and e ...

(FNAF, National Front for French Algeria) was created in June 1960 in Paris, gathering around de Gaulle's former Secretary Jacques Soustelle, Claude Dumont Claude may refer to:

__NOTOC__ People and fictional characters

* Claude (given name), a list of people and fictional characters

* Claude (surname), a list of people

* Claude Lorrain (c. 1600–1682), French landscape painter, draughtsman and etcher ...

, Georges Sauge Georges may refer to:

Places

* Georges River, New South Wales, Australia

* Georges Quay (Dublin)

*Georges Township, Fayette County, Pennsylvania

Other uses

*Georges (name)

* ''Georges'' (novel), a novel by Alexandre Dumas

* "Georges" (song), a 19 ...

, Yvon Chautard, Jean-Louis Tixier-Vignancour (who later competed in the 1965 presidential election), Jacques Isorni

Jacques Isorni (1911–1995) was a French lawyer and memoirist. He came to prominence for his role as defending counsel in a number of cases involving prominent figures on the far right as well as for his own involvement in right wing politics.

E ...

, Victor Barthélemy

Victor Barthélemy (21 July 1906 – 21 October 1985) was a French political activist, operative, and author. Originally a member of the French Communist Party and the Communist International, he moved to the fascist French Popular Party. After ...

, François Brigneau

François Brigneau (30 April 1919 - 9 April 2012) was a French far-right journalist and author who was a leading figure in '' Ordre Nouveau'', the National Front and the Party of New Forces.

Early years

Brigneau was born in Concarneau;Philip R ...

and Jean-Marie Le Pen. Another ''ultra'' rebellion occurred in December 1960, which led de Gaulle to dissolve the FNAF.

After the publication of the ''Manifeste des 121 The Manifesto of the 121 (french: Manifeste des 121, full title: ''Déclaration sur le droit à l’insoumission dans la guerre d’Algérie'' or ''Declaration on the right of insubordination in the Algerian War'') was an open letter signed by 121 i ...

'' against the use of torture and the war,French Section of the Workers' International

The French Section of the Workers' International (french: Section française de l'Internationale ouvrière, SFIO) was a political party in France that was founded in 1905 and succeeded in 1969 by the modern-day Socialist Party. The SFIO was found ...

(SFIO) socialist party, the Radical-Socialist Party, Force ouvrière

The General Confederation of Labor - Workers' Force (french: Confédération Générale du Travail - Force Ouvrière, or simply , FO), is one of the five major union confederations in France. In terms of following, it is the third behind the CGT ...

(FO) trade union, Confédération Française des Travailleurs Chrétiens trade-union, UNEF trade-union, etc., which supported de Gaulle against the ''ultras''.

Role of women

Women participated in a variety of roles during the Algerian War. The majority of Muslim women who became active participants did so on the side of the National Liberation Front (FLN). The French included some women, both Muslim and French, in their war effort, but they were not as fully integrated, nor were they charged with the same breadth of tasks as the women on the Algerian side. The total number of women involved in the conflict, as determined by post-war veteran registration, is numbered at 11,000, but it is possible that this number was significantly higher due to underreporting.

Women participated in a variety of roles during the Algerian War. The majority of Muslim women who became active participants did so on the side of the National Liberation Front (FLN). The French included some women, both Muslim and French, in their war effort, but they were not as fully integrated, nor were they charged with the same breadth of tasks as the women on the Algerian side. The total number of women involved in the conflict, as determined by post-war veteran registration, is numbered at 11,000, but it is possible that this number was significantly higher due to underreporting.[Lazreg, Marnia. ''The Eloquence of Silence''. London: Routledge, 1994 p. 120] Largely illiterate rural women, on the other hand, the remaining eighty percent, due to their geographic location in respect to the operations of FLN often became involved in the conflict as a result of proximity paired with force.[ the range of involvement by a woman could include both combatant and non-combatant roles. While most women's tasks were non-combatant, their less frequent, violent acts were more noticed. The reality was that "rural women in maquis rural areas support networks" contained the overwhelming majority of those who participated; female combatants were in the minority.

Perhaps the most famous incident involving Algerian women revolutionaries was the Milk Bar Café bombing of 1956, when Zohra Drif and ]Yacef Saâdi

Saadi Yacef (; 20 January 1928 – 10 September 2021) was an Algerian independence fighter, serving as a leader of the National Liberation Front during his country's war of independence. He was a Senator in Algeria's Council of the Nation un ...

planted three bombs: one in the Air France office in the Mauritania building in Algiers, which did not explode, one in a cafeteria on the Rue Michelet, and another at the Milk Bar Café, which killed 3 young women and injured multiple adults and children. Algerian Communist Party-member Raymonde Peschard was initially accused of being an accomplice to the bombing and was forced to flee from the colonial authorities.Charles de Gaulle

Charles André Joseph Marie de Gaulle (; ; (commonly abbreviated as CDG) 22 November 18909 November 1970) was a French army officer and statesman who led Free France against Nazi Germany in World War II and chaired the Provisional Government ...

on the anniversary of Algerian independence in 1962.

End of the war

De Gaulle convoked the first referendum on the self-determination of Algeria on 8 January 1961, which 75% of the voters (both in France and Algeria) approved and de Gaulle's government began secret peace negotiations with the FLN. In the Algerian ''départements'' 69.51% voted in favor of self-determination.[

The ]generals' putsch

The Algiers putsch (french: Putsch d'Alger or ), also known as the Generals' putsch (''Putsch des généraux''), was a failed coup d'état intended to force French President Charles de Gaulle not to abandon French Algeria, along with the resi ...

in April 1961, aimed at canceling the government's negotiations with the FLN, marked the turning point in the official attitude toward the Algerian war. Leading the coup attempt to depose de Gaulle were General Raoul Salan, General André Zeller, General Maurice Challe, and General Edmond Jouhaud.[ Only the paratroop divisions and the Foreign Legion joined the coup, while the Air Force, Navy and most of the Army stayed loyal to General de Gaulle, but at one moment de Gaulle went on French television to ask for public support with the normally lofty de Gaulle saying "Frenchmen, Frenchwomen, help me!".][ De Gaulle was now prepared to abandon the ''Pied-Noirs'', which no previous French government was willing to do. The army had been discredited by the putsch and kept a low profile politically throughout the rest of France's involvement with Algeria. The OAS was to be the main standard bearer for the ''Pied-Noirs'' for the rest of the war.

Talks with the FLN reopened at Évian in May 1961; after several false starts, the French government decreed that a ceasefire would take effect on March 18, 1962. A major difficulty at the talks was de Gaulle's decision to grant independence only to the coastal regions of Algeria, where the bulk of the population lived, while hanging onto the Sahara, which happened to be rich in oil and gas, while the FLN claimed all of Algeria.][ During the talks, the ''Pied-Noirs'' and Muslim communities engaged in a low level civil war with bombings, shootings, throat-cutting and assassinations being the preferred methods.][ The Canadian historian John Cairns wrote at times it seemed like both communities were "going berserk" as everyday "murder was indiscriminate".][

On 29 June 1961, de Gaulle announced on TV that fighting was "virtually finished" and afterwards there were no major battles between the French Army and the FLN. During the summer of 1961 the OAS and the FLN engaged in a civil war, in which the greater numbers of the Muslims predominated.]4th Tirailleur Regiment

Fourth or the fourth may refer to:

* the ordinal form of the number 4

* ''Fourth'' (album), by Soft Machine, 1971

* Fourth (angle), an ancient astronomical subdivision

* Fourth (music), a musical interval

* ''The Fourth'' (1972 film), a Sovie ...

opened fire on a crowd of ''Pied-Noir'' demonstrators in Algiers, killing between 50 and 80 civilians. Total casualties in these three incidents were 326 killed and wounded amongst the ''Pied-Noirs'' and 110 French military personnel dead or injured.Mers El Kébir

Mers El Kébir ( ar, المرسى الكبير, translit=al-Marsā al-Kabīr, lit=The Great Harbor ) is a port on the Mediterranean Sea, near Oran in Oran Province, northwest Algeria. It is famous for the attack on the French fleet in 1940, in t ...

until 1967. (The Evian Accords had permitted France to maintain its military presence for fifteen years, so the withdrawal in 1967 was significantly ahead of schedule.[) Cairns writing from Paris in 1962 declared: "In some ways the last year has been the worse. Tension has never been higher. Disenchantment in France at least has never been greater. The mindless cruelty of it all has never been more absurd and savage. This last year, stretching from the hopeful spring of 1961 to the ceasefire of 18 March 1962 spanned a season of shadow boxing, false threats, capitulation and murderous hysteria. French Algeria died badly. Its agony was marked by panic and brutality as ugly as the record of European imperialism could show. In the spring of 1962 the unhappy corpse of empire still shuddered and lashed out and stained itself in fratricide. The whole episode of its death, measured at least seven and half years, constituted perhaps the most pathetic and sordid event in the entire history of colonialism. It is hard to see how anybody of importance in the tangled web of the conflict came out looking well. Nobody won the conflict, nobody dominated it."][

]

Strategy of internationalisation of the Algerian War led by the FLN

At the beginning of the war, on the Algerian side, it was necessary to compensate for military weakness with political and diplomatic struggle. In the asymmetric conflict between France and the FLN at this time, victory seemed extremely difficult.

The Algerian revolution began with the insurrection of November 1, when the FLN organized a series of attacks against the French army and military infrastructure, and published a statement calling on Algerians to get involved in the revolution. This initial campaign had limited impact: the events remained largely unreported, especially by the French press (only two newspaper columns in '' Le Monde'' and one in ''l'Express

''L'Express'' () is a French weekly news magazine headquartered in Paris. The weekly stands at the political centre in the French media landscape, and has a lifestyle supplement, ''L'Express Styles'', and a job supplement, ''Réussir''.

History ...

''), and the insurrection all but subsided. Nevertheless, François Mitterrand

François Marie Adrien Maurice Mitterrand (26 October 19168 January 1996) was President of France, serving under that position from 1981 to 1995, the longest time in office in the history of France. As First Secretary of the Socialist Party, he ...

, the French Minister of the Interior, sent 600 soldiers to Algeria.

Furthermore, the FLN was weak militarily at the beginning of the war. It was created in 1954 and had few members, and its ally the ALN

Aluminium nitride ( Al N) is a solid nitride of aluminium. It has a high thermal conductivity of up to 321 W/(m·K) and is an electrical insulator. Its wurtzite phase (w-AlN) has a band gap of ~6 eV at room temperature and has a potent ...

was also underdeveloped, having only 3,000 men badly equipped and trained, unable to compete with the French army. The nationalist forces also suffered from internal divisions.

As proclaimed in the statement of 1954, the FLN developed a strategy to avoid large-scale warfare and internationalize the conflict, appealing politically and diplomatically to influence French and world opinion.Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because the ...

and the emergence of the Third World.

Firstly, the FLN exploited the tensions between the American-led Western Bloc and the Soviet-led Communist bloc

The Eastern Bloc, also known as the Communist Bloc and the Soviet Bloc, was the group of socialist states of Central and Eastern Europe, East Asia, Southeast Asia, Africa, and Latin America under the influence of the Soviet Union that existed du ...

. FLN sought material support from the Communists, goading the Americans to support of Algerian independence to keep the country on the western side. Furthermore, the FLN used the tensions within each bloc, including between France and the US and between the USSR and Mao's China. The US, which generally opposed colonisation, had every interest in pushing France to give Algeria its independence.

Secondly, the FLN could count on Third World support. After World War II, many new states were created in the wave of decolonization: in 1945 there were 51 states in the UN, but by 1965 there were 117. This upturned the balance of power in the UN, with the recently decolonized countries now a majority with great influence. Most of the new states were part of the Third-World movement, proclaiming a third, non-aligned path in a bipolar world, and opposing colonialism in favor of national renewal and modernization. They felt concerned in the Algerian conflict and supported the FLN on the international stage. For example, a few days after the first insurrection in 1954, Radio Yugoslavia (Third-Worldist) begun to vocally support the struggle of Algeria; the 1955 Bandung conference

The first large-scale Asian–African or Afro–Asian Conference ( id, Konferensi Asia–Afrika)—also known as the Bandung Conference—was a meeting of Asian and African states, most of which were newly independent, which took place on 18–2 ...

internationally recognized the FLN as representing Algeria;China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's most populous country, with a population exceeding 1.4 billion, slightly ahead of India. China spans the equivalent of five time zones and ...

helped to rebuild the ALN to 20 000 men.Khrushchev

Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev (– 11 September 1971) was the General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1953 to 1964 and Premier of the Soviet Union, chairm ...

intensified moral support for the Algerian rebellion, which in turn pushed the USA to react.Matthew Connelly

Matthew James Connelly (born November 25, 1967) is an American professor of international and global history at Columbia University. His areas of expertise include the global Cold War, official secrecy, population control, and decolonization. He ...

, this strategy of internationalization became a model for other revolutionary groups such as the Palestine Liberation Organization

The Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO; ar, منظمة التحرير الفلسطينية, ') is a Palestinian nationalism, Palestinian nationalist political and militant organization founded in 1964 with the initial purpose of establ ...

of Yasser Arafat, and the African National Congress of Nelson Mandela

Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela (; ; 18 July 1918 – 5 December 2013) was a South African Internal resistance to apartheid, anti-apartheid activist who served as the President of South Africa, first president of South Africa from 1994 to 1 ...

.

Exodus of the Pieds-Noirs and Harkis

''Pieds-Noirs

The ''Pieds-Noirs'' (; ; ''Pied-Noir''), are the people of French and other European descent who were born in Algeria during the period of French rule from 1830 to 1962; the vast majority of whom departed for mainland France as soon as Alger ...