Acadia National Park, Maine on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Acadia National Park is an American

The park includes mountains, an ocean coastline, woodlands, lakes, and ponds. In addition to nearly half of Mount Desert Island, the park designation also preserves a portion of the

The park includes mountains, an ocean coastline, woodlands, lakes, and ponds. In addition to nearly half of Mount Desert Island, the park designation also preserves a portion of the

. ''nps.gov''. National Park Service. March 2, 2018. Retrieved November 29, 2018.

. ''nps.gov''. National Park Service. February 8, 2018. Retrieved November 29, 2018. The Park Loop Road leads to many scenic viewpoints along the coast, through forests and to the top of Cadillac Mountain. The road traverses the eastern side of Mount Desert Island in a one-way, clockwise direction from Bar Harbor to Seal Harbor, passing features such as the Tarn (a pond), Champlain Mountain (location of a popular, exposed cliffside trail named Precipice), the Beehive (another, smaller mountain), Sand Beach (a saltwater swimming area), Gorham Mountain, Thunder Hole (a crevasse into which waves crash loudly), Otter Cliff, Otter Cove, Seal Harbor,

The Park Loop Road leads to many scenic viewpoints along the coast, through forests and to the top of Cadillac Mountain. The road traverses the eastern side of Mount Desert Island in a one-way, clockwise direction from Bar Harbor to Seal Harbor, passing features such as the Tarn (a pond), Champlain Mountain (location of a popular, exposed cliffside trail named Precipice), the Beehive (another, smaller mountain), Sand Beach (a saltwater swimming area), Gorham Mountain, Thunder Hole (a crevasse into which waves crash loudly), Otter Cliff, Otter Cove, Seal Harbor,

"Asticou's Island Domain: Wabanaki Peoples at Mount Desert Island 1500–2000, Acadia National Park, Ethnographic Overview and Assessment, Volume 1"archive

. pp. 5-6, 19, 29. Northeast Region Ethnography Program of the National Park Service. Boston, Massachusetts. Retrieved November 20, 2018.

The border established between the United States and Canada after the American Revolution split the Wabanaki homelands. The confederacy was dissolved around 1870 due to pressure from the American and Canadian governments, though the tribal nations continued to interact in their traditional ways. In the nineteenth century, Wabanakis sold handmade

The border established between the United States and Canada after the American Revolution split the Wabanaki homelands. The confederacy was dissolved around 1870 due to pressure from the American and Canadian governments, though the tribal nations continued to interact in their traditional ways. In the nineteenth century, Wabanakis sold handmade

The Italian explorer Giovanni da Verrazzano sailed along the coast of Mount Desert Island during an expedition for the French Crown in 1524. He was followed by Estêvão Gomes, a Portuguese explorer for the Spanish Crown in 1525. French explorer Jean Alfonse arrived in 1542. Alfonse entered

The Italian explorer Giovanni da Verrazzano sailed along the coast of Mount Desert Island during an expedition for the French Crown in 1524. He was followed by Estêvão Gomes, a Portuguese explorer for the Spanish Crown in 1525. French explorer Jean Alfonse arrived in 1542. Alfonse entered

The first French missionary colony in America was established on Mount Desert Island in 1613. The colony was destroyed a short time later by an armed vessel from the

The first French missionary colony in America was established on Mount Desert Island in 1613. The colony was destroyed a short time later by an armed vessel from the

From 1915 to 1940, the wealthy philanthropist John D. Rockefeller Jr. financed, designed, and directed the construction of a network of carriage roads throughout the park."Acadia's Historic Carriage Roads"

From 1915 to 1940, the wealthy philanthropist John D. Rockefeller Jr. financed, designed, and directed the construction of a network of carriage roads throughout the park."Acadia's Historic Carriage Roads"

. ''nps.gov''. National Park Service. December 14, 2015. Retrieved November 23, 2018.archive

. ''nps.gov''. May 2007. National Park Service. Retrieved December 9, 2018. About of carriage roads are maintained and accessible within park boundaries. Granite coping stones along carriage road edges act as guard rails; they are nicknamed "Rockefeller's Teeth." The carriage roads are open from the end of the spring mud season, generally in late April, through the summer, autumn, and winter months, until the following spring thaw causes another closure in March to prevent damage to the gravel surface.

Acadia National Park's first naturalist, Arthur Stupka, also had the distinction of being the first NPS naturalist to serve in any of the NPS's eastern United States districts. He joined the park staff in 1932, and in the capacity of park naturalist he wrote, edited and published a four-volume serial entitled ''Nature Notes from Acadia'' (1932–1935).

Beginning on October 17, 1947, more than of Acadia National Park burned in a fire that also destroyed an additional of Mount Desert Island outside the park. The fire began along Crooked Road west of Hulls Cove (northwest of Bar Harbor). The forest fire was one of a series of fires that consumed much of Maine's forest in a dry year. The fire burned until November 14, and was fought by the Coast Guard, Army Air Corps, Navy, local residents, and National Park Service employees from around the country. Sixty-seven of the historic summer cottages along Millionaires’ Row, along with 170 other homes, and five hotels were destroyed. Restoration of the park was substantially supported by the Rockefeller family. Regrowth has occurred naturally with new deciduous forests consisting of birch and aspen enhancing the colors of autumn foliage, adding diversity to tree populations, and providing for the eventual regeneration of spruce and fir forests.

Beginning on October 17, 1947, more than of Acadia National Park burned in a fire that also destroyed an additional of Mount Desert Island outside the park. The fire began along Crooked Road west of Hulls Cove (northwest of Bar Harbor). The forest fire was one of a series of fires that consumed much of Maine's forest in a dry year. The fire burned until November 14, and was fought by the Coast Guard, Army Air Corps, Navy, local residents, and National Park Service employees from around the country. Sixty-seven of the historic summer cottages along Millionaires’ Row, along with 170 other homes, and five hotels were destroyed. Restoration of the park was substantially supported by the Rockefeller family. Regrowth has occurred naturally with new deciduous forests consisting of birch and aspen enhancing the colors of autumn foliage, adding diversity to tree populations, and providing for the eventual regeneration of spruce and fir forests.

The region is characterized by a large seasonal variation in temperature with warm to hot summers that are often humid, and cold to severely cold winters. According to the Köppen climate classification system, Mount Desert Island has a warm-summer humid continental climate (''Dfb''). The average annual temperature in the park is 47.3 °F (8.5 °C). July is the warmest month with an average of 69.7 °F (20.9 °C), while January is the coldest month with an average of 23.8 °F (-4.6 °C). The record high and low temperatures are 96 °F (36 °C) and -21 °F (-29 °C), respectively. The plant

The region is characterized by a large seasonal variation in temperature with warm to hot summers that are often humid, and cold to severely cold winters. According to the Köppen climate classification system, Mount Desert Island has a warm-summer humid continental climate (''Dfb''). The average annual temperature in the park is 47.3 °F (8.5 °C). July is the warmest month with an average of 69.7 °F (20.9 °C), while January is the coldest month with an average of 23.8 °F (-4.6 °C). The record high and low temperatures are 96 °F (36 °C) and -21 °F (-29 °C), respectively. The plant

The Cadillac Mountain Intrusive Complex is part of the Coastal Maine Magmatic Province, consisting of over a hundred mafic and

The Cadillac Mountain Intrusive Complex is part of the Coastal Maine Magmatic Province, consisting of over a hundred mafic and

Mount Desert Island granite was created about 420 Mya, with one of the oldest granite bodies being Cadillac Mountain, the largest on the island. The granite body rose slowly through bedrock, fracturing it into large pieces, some of which melted under intense heat. As the granite cooled, the bedrock fragments were left surrounded by crystallized granite in a shatter zone that is visible on the eastern side of the mountain. A fine-grained, black igneous rock called diabase intruded into the granite during later volcanic activity. Diabase bodies, or dikes, are visible along the Cadillac Mountain road and on the Schoodic Peninsula.

During the next several hundred million years, the rock layers that still covered the large granite bodies, along with softer rock surrounding the granite, were worn away by erosion.

Mount Desert Island granite was created about 420 Mya, with one of the oldest granite bodies being Cadillac Mountain, the largest on the island. The granite body rose slowly through bedrock, fracturing it into large pieces, some of which melted under intense heat. As the granite cooled, the bedrock fragments were left surrounded by crystallized granite in a shatter zone that is visible on the eastern side of the mountain. A fine-grained, black igneous rock called diabase intruded into the granite during later volcanic activity. Diabase bodies, or dikes, are visible along the Cadillac Mountain road and on the Schoodic Peninsula.

During the next several hundred million years, the rock layers that still covered the large granite bodies, along with softer rock surrounding the granite, were worn away by erosion.

During the last two to three million years, a series of ice sheets flowed and receded across northern North America, eroding mountains and creating U-shaped valleys.

The glacier that covered Mount Desert Range, part of which is now called Mount Desert Island, was thick and moved at the rate of a few yards (meters) per year. The mountain range was heavily eroded by the glacier which rounded off mountaintops, carved saddles, deepened valleys, and created the fjard known as Somes Sound, nearly dividing the current island in half."The Story of Glaciers"

During the last two to three million years, a series of ice sheets flowed and receded across northern North America, eroding mountains and creating U-shaped valleys.

The glacier that covered Mount Desert Range, part of which is now called Mount Desert Island, was thick and moved at the rate of a few yards (meters) per year. The mountain range was heavily eroded by the glacier which rounded off mountaintops, carved saddles, deepened valleys, and created the fjard known as Somes Sound, nearly dividing the current island in half."The Story of Glaciers"archive

. ''nps.gov''. National Park Service. Retrieved December 7, 2018. Evidence of the last glacial period, the Wisconsin glaciation from about 75,000 to 11,000 years ago, is visible as long scratches, or striations, and crescent-shaped gouges created by material carried along at the base of the ice. As the climate warmed, the glaciers melted and receded, leaving boulders that had been carried or further south from their original locations. These boulders, or glacial erratics, lie in valleys and on mountaintops, including Bubble Rock on the South Bubble.

The coastal areas of Maine sank slightly under the extreme weight of the ice sheets, allowing seawater to cover lowlands thus forming the present-day islands. Evidence of sea caves and past beaches can be found about above current sea level. As the ice receded and the land stabilized, lakes and ponds formed in valleys dammed by glacial debris. Rivers and streams flowed again through the watershed, continuing the gradual erosion of the drainage paths.

Acadia has a coastline composed of rocky

Acadia has a coastline composed of rocky

Frequent thawing in winter prevents large accumulations of snow, and keeps the ground well saturated. Ice storms are common in winter and early spring, while rain occurs throughout the year. Saturated soils, thawing, and heavy precipitation lead to rockfalls every spring along Mount Desert Island's loop road, as well as

Frequent thawing in winter prevents large accumulations of snow, and keeps the ground well saturated. Ice storms are common in winter and early spring, while rain occurs throughout the year. Saturated soils, thawing, and heavy precipitation lead to rockfalls every spring along Mount Desert Island's loop road, as well as

The ecological zones at Acadia National Park, from highest to lowest elevation, include: nearly barren mountain

The ecological zones at Acadia National Park, from highest to lowest elevation, include: nearly barren mountain

Flora common to both deciduous and

Flora common to both deciduous and

. ''nps.gov''. National Park Service. July 15, 2016. Retrieved December 3, 2018.

national park

A national park is a nature park, natural park in use for conservation (ethic), conservation purposes, created and protected by national governments. Often it is a reserve of natural, semi-natural, or developed land that a sovereign state dec ...

located along the mid-section of the Maine coast, southwest of Bar Harbor. The park preserves about half of Mount Desert Island, part of the Isle au Haut, the tip of the Schoodic Peninsula

The Schoodic Peninsula is a peninsula in Down East Maine. It is located four miles (6 km) east of Bar Harbor, Maine, as the crow flies. The Schoodic Peninsula contains , or approximately 5% of Acadia National Park. It includes the towns of ...

, and portions of 16 smaller outlying islands. It protects the natural beauty of the rocky headlands

A headland, also known as a head, is a coastal landform, a point of land usually high and often with a sheer drop, that extends into a body of water. It is a type of promontory. A headland of considerable size often is called a cape.Whittow, Joh ...

, including the highest mountains along the Atlantic coast. Acadia boasts a glaciated coastal and island landscape, an abundance of habitats, a high level of biodiversity, clean air and water, and a rich cultural heritage.

The park contains the tallest mountain on the Atlantic Coast of the United States (Cadillac Mountain

Cadillac Mountain is located on Mount Desert Island, within Acadia National Park, in the U.S. state of Maine. With an elevation of , its summit is the highest point in Hancock County and the highest within of the Atlantic shoreline of the North ...

), exposed granite domes

Granite domes are domical hills composed of granite with bare rock exposed over most of the surface. Generally, domical features such as these are known as bornhardts. Bornhardts can form in any type of plutonic rock but are typically composed o ...

, glacial erratics

A glacial period (alternatively glacial or glaciation) is an interval of time (thousands of years) within an ice age that is marked by colder temperatures and glacier advances. Interglacials, on the other hand, are periods of warmer climate betw ...

, U-shaped valleys, and cobble

Cobble may refer to:

* Cobble (geology), a designation of particle size for sediment or clastic rock

* Cobblestone, partially rounded rocks used for road paving

* Hammerstone, a prehistoric stone tool

* Tyringham Cobble, a nature reserve in Tyr ...

beaches. Its mountains, lakes, streams, wetlands, forests, meadows, and coastlines contribute to a diversity of plants and animals. Weaved into this landscape is a historic carriage road system financed by John D. Rockefeller Jr. In total, it encompasses .

Acadia has a rich human history, dating back more than 10,000 years ago with the Wabanaki people. The 17th century brought fur traders and other European explorers, while the 19th century saw an influx of summer visitors, then wealthy families. Many conservation-minded citizens, among them George B. Dorr (the "Father of Acadia National Park"), worked to establish this first U.S. national park east of the Mississippi River and the only one in the Northeastern United States

The Northeastern United States, also referred to as the Northeast, the East Coast, or the American Northeast, is a geographic region of the United States. It is located on the Atlantic coast of North America, with Canada to its north, the Southe ...

. Acadia was initially designated Sieur de Monts National Monument

A national monument is a monument constructed in order to commemorate something of importance to national heritage, such as a country's founding, independence, war, or the life and death of a historical figure.

The term may also refer to a spec ...

by proclamation of President Woodrow Wilson in 1916, then renamed and redesignated Lafayette National Park in 1919. The park was renamed Acadia National Park in 1929.

Recreational activities from spring through autumn include car and bus touring along the park's paved loop road; hiking, bicycling, and horseback riding on carriage roads (motor vehicles are prohibited); fishing; rock climbing; kayaking and canoeing on lakes and ponds; swimming at Sand Beach and Echo Lake; sea kayaking and guided boat tours on the ocean; and various ranger-led programs. Winter activities include cross-country skiing, snowshoeing, snowmobiling, and ice fishing. Two campgrounds are located on Mount Desert Island, another campground is on the Schoodic Peninsula, and five lean-to

A lean-to is a type of simple structure originally added to an existing building with the rafters "leaning" against another wall. Free-standing lean-to structures are generally used as shelters. One traditional type of lean-to is known by its Finn ...

sites are on Isle au Haut. The main visitor center is at Hulls Cove, northwest of Bar Harbor. Park visitation has been steadily increasing in Acadia over the past decade, with 2021 seeing a record count of 4.07 million visitors.

Geography

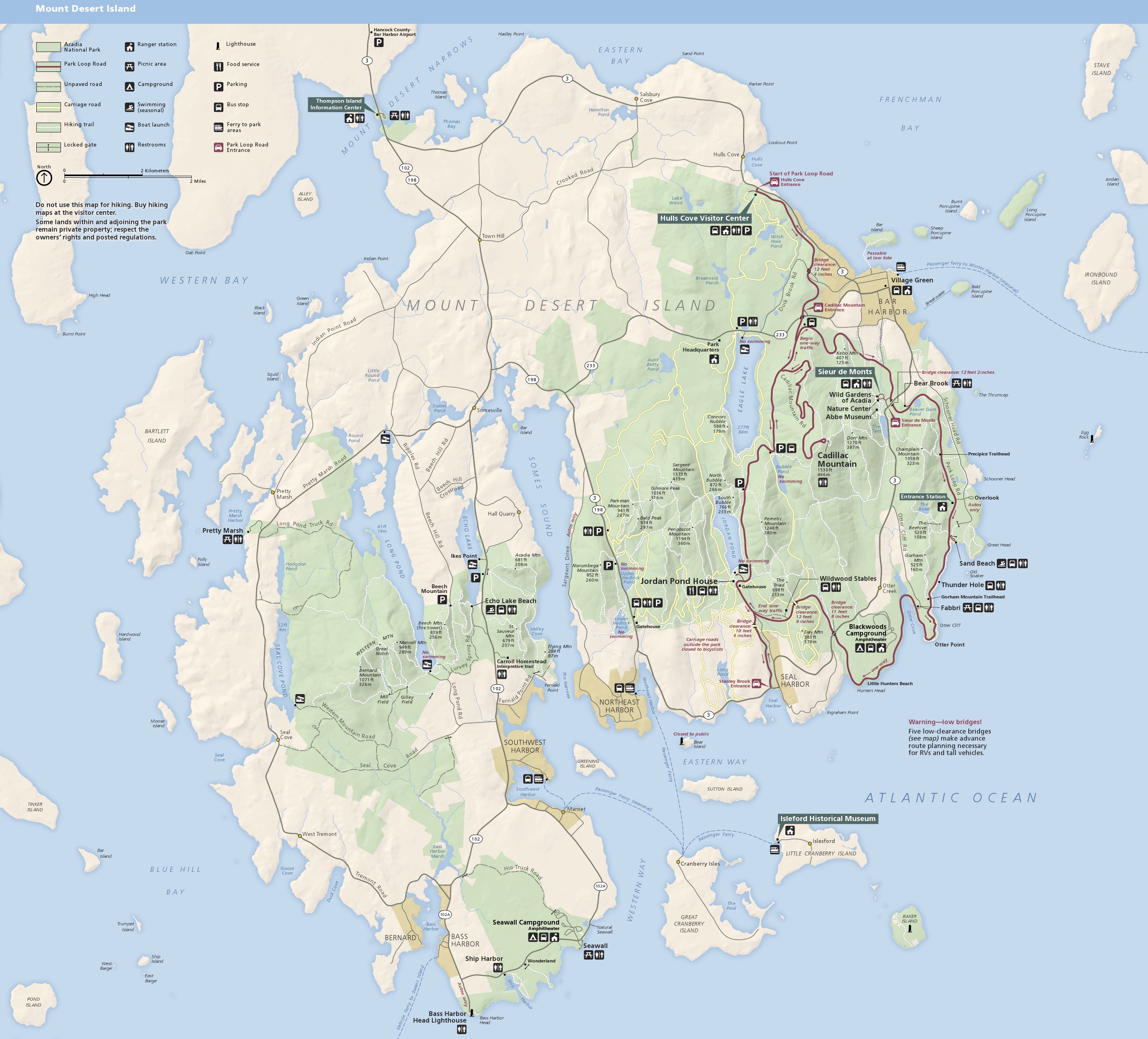

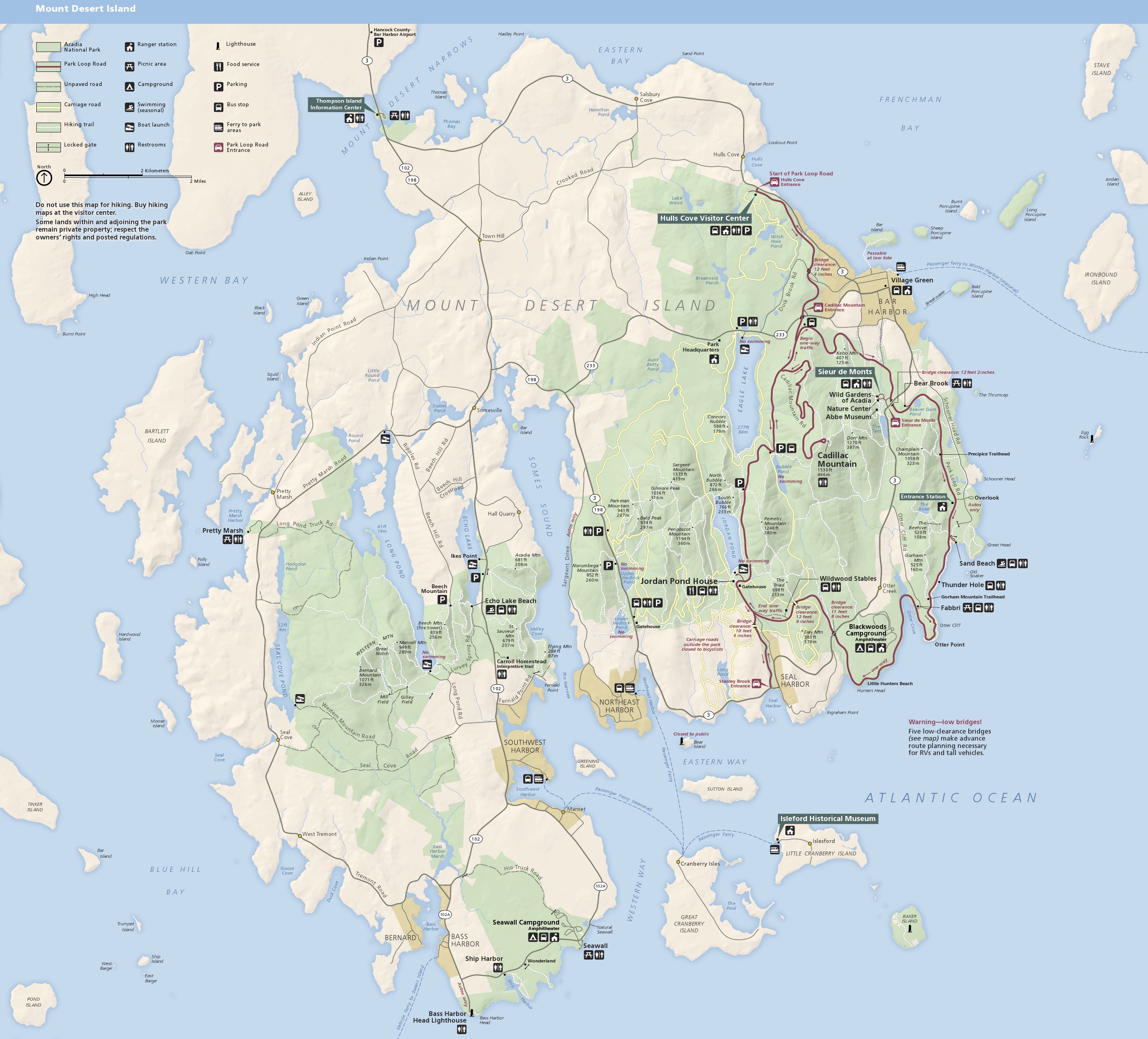

The park includes mountains, an ocean coastline, woodlands, lakes, and ponds. In addition to nearly half of Mount Desert Island, the park designation also preserves a portion of the

The park includes mountains, an ocean coastline, woodlands, lakes, and ponds. In addition to nearly half of Mount Desert Island, the park designation also preserves a portion of the Schoodic Peninsula

The Schoodic Peninsula is a peninsula in Down East Maine. It is located four miles (6 km) east of Bar Harbor, Maine, as the crow flies. The Schoodic Peninsula contains , or approximately 5% of Acadia National Park. It includes the towns of ...

on the mainland, as well as the majority of Isle au Haut and Baker Island, all of Bar Island

Bar Island () is a tidal island across from Bar Harbor on Mount Desert Island, Maine, United States. The uninhabited island is mostly forested in pine and birch trees and the island is now part of Acadia National Park

Acadia National Park i ...

, three of the four Porcupine Islands (Sheep, Bald and Long), the Thrumcap (an islet), part of Bear Island, and Thompson Island in Mount Desert Narrows, as well as several other islands and islets."Acadia National Park Maps". ''nps.gov''. National Park Service. March 2, 2018. Retrieved November 29, 2018.

Features

The mountains of Acadia National Park offer hikers expansive views of the ocean, island lakes, and pine forests. Twenty six significant mountains rise in the park, ranging from at Flying Mountain's summit to atCadillac Mountain

Cadillac Mountain is located on Mount Desert Island, within Acadia National Park, in the U.S. state of Maine. With an elevation of , its summit is the highest point in Hancock County and the highest within of the Atlantic shoreline of the North ...

's summit. Cadillac Mountain, named after the French explorer Antoine de la Mothe Cadillac, is on the eastern side of the island. Cadillac is the tallest mountain along the eastern coastline of the United States."Places To Go: Scenic Areas". ''nps.gov''. National Park Service. February 8, 2018. Retrieved November 29, 2018.

The Park Loop Road leads to many scenic viewpoints along the coast, through forests and to the top of Cadillac Mountain. The road traverses the eastern side of Mount Desert Island in a one-way, clockwise direction from Bar Harbor to Seal Harbor, passing features such as the Tarn (a pond), Champlain Mountain (location of a popular, exposed cliffside trail named Precipice), the Beehive (another, smaller mountain), Sand Beach (a saltwater swimming area), Gorham Mountain, Thunder Hole (a crevasse into which waves crash loudly), Otter Cliff, Otter Cove, Seal Harbor,

The Park Loop Road leads to many scenic viewpoints along the coast, through forests and to the top of Cadillac Mountain. The road traverses the eastern side of Mount Desert Island in a one-way, clockwise direction from Bar Harbor to Seal Harbor, passing features such as the Tarn (a pond), Champlain Mountain (location of a popular, exposed cliffside trail named Precipice), the Beehive (another, smaller mountain), Sand Beach (a saltwater swimming area), Gorham Mountain, Thunder Hole (a crevasse into which waves crash loudly), Otter Cliff, Otter Cove, Seal Harbor, Jordan Pond

Jordan Pond is an oligotrophic tarn in Acadia National Park near the town of Bar Harbor, Maine. The pond covers to a maximum depth of with a shoreline of .

The pond was formed by the Wisconsin Ice Sheet during the last glacial period. Penobsco ...

, Pemetic Mountain, the Bubbles, Bubble Rock, Bubble Pond, Eagle Lake, and the side road to the summit of Cadillac Mountain. Some of the island's west side features include Echo Lake and beach (a designated freshwater swimming area), Acadia Mountain, Beech Mountain, Long Pond, and Seal Cove Pond. Bass Harbor Head Light is situated atop a cliff on the southernmost tip of the west side of the island. Baker Island Light and Bear Island Light

Bear Island Light is a lighthouse on Bear Island near Mt. Desert Island, at the entrance to Northeast Harbor, Maine. It was first established in 1839. The present structure was built in 1889. It was deactivated in 1981 and relit as a private a ...

are the other two lighthouses managed by Acadia.

Somes Sound

Somes Sound is a fjard,

a body of water running deep into Mount Desert Island, the main site of Acadia National Park in Maine, United States. Its deepest point is approximately , and it is over deep in several places. The sound almost splits the ...

is a long fjard formed during a glacial period that nearly divides the island in half. The sound is deep at its deepest point, and is bordered by Norumbega Mountain to the east, and Acadia Mountain and Saint Sauveur Mountain to the west. The towns of Southwest Harbor and Northeast Harbor

Northeast Harbor is a village on Mount Desert Island, located in the town of Mount Desert, Maine, Mount Desert in Hancock County, Maine, Hancock County, Maine, United States.

The original settlers, the Someses and Richardsons, arrived around ...

face one another across the inlet to Somes Sound.

History

Native people

Native Americans have inhabited the area called Acadia for at least 12,000 years, including the coastal areas of Maine, Canada, and adjacent islands. The Wabanaki Confederacy ("People of the Dawnland") consists of five related Algonquian nations—theMaliseet

The Wəlastəkwewiyik, or Maliseet (, also spelled Malecite), are an Algonquian-speaking First Nation of the Wabanaki Confederacy. They are the indigenous people of the Wolastoq ( Saint John River) valley and its tributaries. Their territory ...

, Mi'kmaq, Passamaquoddy

The Passamaquoddy ( Maliseet-Passamaquoddy: ''Peskotomuhkati'') are a Native American/First Nations people who live in northeastern North America. Their traditional homeland, Peskotomuhkatik'','' straddles the Canadian province of New Brunswick ...

, Abenaki and Penobscot. Some of the nations call Mount Desert Island ''Pemetic'' ("range of mountains"), which has remained at the center of the Wabanaki traditional ancestral homeland and territory of traditional stewardship responsibility to the present day. The etymology of the park's name begins with the Mi'kmaq term ''akadie'' ("piece of land") which was rendered as ''l'Acadie'' by French explorers, and translated into English as Acadia.

The Wabanaki traveled to the island in birch bark canoes to hunt, fish, gather berries, harvest clams and basket-making resources like sweetgrass, and to trade with other Wabanakis. They camped near places like Somes Sound

Somes Sound is a fjard,

a body of water running deep into Mount Desert Island, the main site of Acadia National Park in Maine, United States. Its deepest point is approximately , and it is over deep in several places. The sound almost splits the ...

.

In the early 17th century, Asticou was the chieftain of the greater Mount Desert Island area, one district of an intertribal confederacy known as Mawooshen led by the grandchief Bashaba. Castine (''Pentagoet'' in the native language) was the grandchief's favored rendezvous site for the Wabanaki tribes. The site is located just west of Mount Desert Island at the mouth of the Bagaduce River

The Bagaduce River is a tidal river in the Hancock County, Maine that empties into Penobscot Bay near the town of Castine. From the confluence of Black Brook and the outflow of Walker Pond (), the river runs about U.S. Geological Survey. Nationa ...

in eastern Penobscot Bay

Penobscot Bay (french: Baie de Penobscot) is an inlet of the Gulf of Maine and Atlantic Ocean in south central Maine. The bay originates from the mouth of Maine's Penobscot River, downriver from Belfast, Maine, Belfast. Penobscot Bay has many ...

. From 1615, Castine developed into a major fur trading post where French, English, and Dutch traders all fought for control. Sealskin

Sealskin is the skin of a seal.

Seal skins have been used by aboriginal people for millennia to make waterproof jackets and boots, and seal fur to make fur coats. Sailors used to have tobacco pouches made from sealskin. Canada, Greenland, Norwa ...

s, moose hides, and furs were traded by the Wabanakis for European commodities. By the early 1620s, warfare and introduced diseases, including smallpox, cholera

Cholera is an infection of the small intestine by some strains of the bacterium ''Vibrio cholerae''. Symptoms may range from none, to mild, to severe. The classic symptom is large amounts of watery diarrhea that lasts a few days. Vomiting and ...

and influenza

Influenza, commonly known as "the flu", is an infectious disease caused by influenza viruses. Symptoms range from mild to severe and often include fever, runny nose, sore throat, muscle pain, headache, coughing, and fatigue. These symptoms ...

, had decimated the tribes from Mount Desert Island southward to Cape Cod, leaving about 10 percent of the original population.Prins, Harald E. L.; McBride, Bunny (December 2007)"Asticou's Island Domain: Wabanaki Peoples at Mount Desert Island 1500–2000, Acadia National Park, Ethnographic Overview and Assessment, Volume 1"

. pp. 5-6, 19, 29. Northeast Region Ethnography Program of the National Park Service. Boston, Massachusetts. Retrieved November 20, 2018.

The border established between the United States and Canada after the American Revolution split the Wabanaki homelands. The confederacy was dissolved around 1870 due to pressure from the American and Canadian governments, though the tribal nations continued to interact in their traditional ways. In the nineteenth century, Wabanakis sold handmade

The border established between the United States and Canada after the American Revolution split the Wabanaki homelands. The confederacy was dissolved around 1870 due to pressure from the American and Canadian governments, though the tribal nations continued to interact in their traditional ways. In the nineteenth century, Wabanakis sold handmade ash

Ash or ashes are the solid remnants of fires. Specifically, ''ash'' refers to all non-aqueous, non- gaseous residues that remain after something burns. In analytical chemistry, to analyse the mineral and metal content of chemical samples, ash ...

and birch bark baskets to travelers. The Wabanaki performed dances for summer tourists and residents at Sieur de Monts and the town of Bar Harbor. Wabanaki guides led canoe trips around Frenchman Bay

Frenchman Bay is a bay in Hancock County, Maine, named for Samuel de Champlain, the French explorer who visited the area in 1604.

Frenchman Bay may have been the location of the Jesuit St. Sauveur mission, established in 1613.

In a 1960 book ...

and the Cranberry Islands.

For two years, 1970–71, the nations operated a Wabanaki educational center called T.R.I.B.E. (Teaching and Research in Bicultural Education) on the west side of Eagle Lake. American Indian land claims in Maine were legally settled in 1980 and 1991. The annual Bar Harbor Native American Festival began in 1989, jointly sponsored by the tribes and the Abbe Museum. The Maine Indian Basketmakers Alliance was formed in 1993, assisting in the coordination of the annual festival with the museum.

Currently, each tribe has a reservation and government headquarters located within their territories throughout Maine. Some Wabanakis live on Mount Desert Island, while others visit for board meetings at the Abbe Museum, to advise on and perform in exhibitions, for craft demonstrations, and to gather sweetgrass and sell handmade baskets at the annual festival.

Exploration

The Italian explorer Giovanni da Verrazzano sailed along the coast of Mount Desert Island during an expedition for the French Crown in 1524. He was followed by Estêvão Gomes, a Portuguese explorer for the Spanish Crown in 1525. French explorer Jean Alfonse arrived in 1542. Alfonse entered

The Italian explorer Giovanni da Verrazzano sailed along the coast of Mount Desert Island during an expedition for the French Crown in 1524. He was followed by Estêvão Gomes, a Portuguese explorer for the Spanish Crown in 1525. French explorer Jean Alfonse arrived in 1542. Alfonse entered Penobscot Bay

Penobscot Bay (french: Baie de Penobscot) is an inlet of the Gulf of Maine and Atlantic Ocean in south central Maine. The bay originates from the mouth of Maine's Penobscot River, downriver from Belfast, Maine, Belfast. Penobscot Bay has many ...

and recorded details about the fur trade. Portuguese navigator Simon Ferdinando guided an English expedition in 1580.

A few hundred people were living on Mount Desert Island when Samuel de Champlain

Samuel de Champlain (; Fichier OrigineFor a detailed analysis of his baptismal record, see RitchThe baptism act does not contain information about the age of Samuel, neither his birth date nor his place of birth. – 25 December 1635) was a Fre ...

arrived in 1604. Two Wabanakis led Champlain to Mount Desert Island, which he named Isle des Monts Deserts (Island of Barren Mountains) due to its barren peaks; he named Isle au Haut (High Island) due to its height.

While he was sailing down the coast on 5 September 1604, Champlain wrote:

Settlement

The first French missionary colony in America was established on Mount Desert Island in 1613. The colony was destroyed a short time later by an armed vessel from the

The first French missionary colony in America was established on Mount Desert Island in 1613. The colony was destroyed a short time later by an armed vessel from the Colony of Virginia

The Colony of Virginia, chartered in 1606 and settled in 1607, was the first enduring English colonial empire, English colony in North America, following failed attempts at settlement on Newfoundland (island), Newfoundland by Sir Humphrey GilbertG ...

as the first act of overt warfare in the long struggle leading to the French and Indian Wars. The island was granted to Antoine de la Mothe Cadillac by Louis XIV of France in 1688, but ceded to England in 1713. Massachusetts governor Sir Francis Bernard, 1st Baronet assumed control of the island in 1760. In 1790, Massachusetts granted the eastern half of the island to Cadillac's granddaughter, Mme. de Gregoire, while Bernard's son John retained ownership of the western half. The first record of summer visitors vacationing on the island was in 1855, and steamboat service from Boston was inaugurated in 1868. The Green Mountain Cog Railway was built from the shore of Eagle Lake to the summit of Cadillac Mountain

Cadillac Mountain is located on Mount Desert Island, within Acadia National Park, in the U.S. state of Maine. With an elevation of , its summit is the highest point in Hancock County and the highest within of the Atlantic shoreline of the North ...

in 1888. In 1901, the Maine Legislature granted Hancock County a charter to acquire and hold land on the island in the public interest. The first land was donated by Mrs. Eliza Homans of Boston in 1908, and had been acquired by 1914.

Rusticators

Artists and journalists had revealed and popularized the island in the mid-1800s. Painters came from the Hudson River School, including Thomas Cole and Frederic Church, inspiring patrons and friends to visit. The term ''rusticator'' was used to describe these early visitors who stayed in the homes of local fishermen and farmers for modest fees. The accommodations soon became insufficient for the increasing amount of summer visitors, and by 1880, thirty hotels were operating on the island. Tourism was becoming the major industry.Cottagers

For a select few Americans, the 1880s and the Gay Nineties meant affluence on a scale without precedent. Mount Desert Island, being remote from the cities of the east, became a summer retreat for families such as theRockefellers

The Rockefeller family () is an American industrial, political, and banking family that owns one of the world's largest fortunes. The fortune was made in the American petroleum industry during the late 19th and early 20th centuries by brothe ...

, Morgans, Fords, Vanderbilts, Carnegies, and Astors

The Astor family achieved prominence in business, society, and politics in the United States and the United Kingdom during the 19th and 20th centuries. With ancestral roots in the Italian Alps region of Italy by way of Germany,

the Astors settled ...

. These families, with the help of developers such as Charles T. How

Charles T. How (1840 – October 8, 1909) was an American lawyer and real-estate developer who began the development of mansions (also known as cottages) in Bar Harbor, Maine, in the late 19th century.

Early life

How was born in 1840.

Caree ...

, constructed elegant estates, which they called cottage

A cottage, during Feudalism in England, England's feudal period, was the holding by a cottager (known as a Cotter (farmer), cotter or ''bordar'') of a small house with enough garden to feed a family and in return for the cottage, the cottager ...

s. Luxury, refinement, and large gatherings replaced the buckboard rides, picnics, and day-long hikes of the rusticators. For more than forty years, the wealthy dominated summer activity on Mount Desert Island, but the Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

and World War II brought an end to the extravagance.

Park origins

The landscape architect Charles Eliot is credited with the idea for the park. George B. Dorr, called the "Father of Acadia National Park," along with Eliot's fatherCharles W. Eliot

Charles William Eliot (March 20, 1834 – August 22, 1926) was an American academic who was president of Harvard University from 1869 to 1909the longest term of any Harvard president. A member of the prominent Eliot family of Boston, he transfo ...

(president of Harvard from 1869 to 1909), supported the idea both through donations of land and through advocacy at the state and federal levels. Dorr later served as the park's first superintendent. President Woodrow Wilson first established its federal status as Sieur de Monts National Monument on July 8, 1916, administered by the National Park Service. It was the first national park created from private lands gifted to the public.

Congress redesignated the national monument as Lafayette National Park on February 26, 1919, the first American national park east of the Mississippi River and the only one in the Northeastern United States

The Northeastern United States, also referred to as the Northeast, the East Coast, or the American Northeast, is a geographic region of the United States. It is located on the Atlantic coast of North America, with Canada to its north, the Southe ...

. The park was named after the Marquis de Lafayette, an influential French participant in the American Revolution. Jordan Pond Road was started in 1922 and completed as a scenic motor highway in 1927. The Cadillac Mountain Summit Road, begun in 1925, was completed in 1931.

The name of the park was changed to Acadia National Park on January 19, 1929, in honor of the former French colony of Acadia which once included Maine. In 1929 Schoodic Peninsula

The Schoodic Peninsula is a peninsula in Down East Maine. It is located four miles (6 km) east of Bar Harbor, Maine, as the crow flies. The Schoodic Peninsula contains , or approximately 5% of Acadia National Park. It includes the towns of ...

was donated to Acadia by John Godfrey Moore's second wife Louise and daughters Ruth and Faith. Keeping up with the taxes on the Schoodic land became a drain on the family finances and they thought this world be a fitting way to honor John Godfrey Moore. There was an unspoken stipulation in the discussions — the heirs were anglophiles that did not want to have their land as part of Lafayette National Park. Conservationist George Dorr, who is referred to as the “Father of Acadia National Park,” suggested the name Acadia and the deal went through after the name changed, ensuring the expansion.

From 1915 to 1940, the wealthy philanthropist John D. Rockefeller Jr. financed, designed, and directed the construction of a network of carriage roads throughout the park."Acadia's Historic Carriage Roads"

From 1915 to 1940, the wealthy philanthropist John D. Rockefeller Jr. financed, designed, and directed the construction of a network of carriage roads throughout the park."Acadia's Historic Carriage Roads". ''nps.gov''. National Park Service. December 14, 2015. Retrieved November 23, 2018.

Jordan Pond

Jordan Pond is an oligotrophic tarn in Acadia National Park near the town of Bar Harbor, Maine. The pond covers to a maximum depth of with a shoreline of .

The pond was formed by the Wisconsin Ice Sheet during the last glacial period. Penobsco ...

and the other near Northeast Harbor

Northeast Harbor is a village on Mount Desert Island, located in the town of Mount Desert, Maine, Mount Desert in Hancock County, Maine, Hancock County, Maine, United States.

The original settlers, the Someses and Richardsons, arrived around ...

."The Carriage Roads of Acadia National Park". ''nps.gov''. May 2007. National Park Service. Retrieved December 9, 2018.

Administrative history

Superintendents

Fire of 1947

Beginning on October 17, 1947, more than of Acadia National Park burned in a fire that also destroyed an additional of Mount Desert Island outside the park. The fire began along Crooked Road west of Hulls Cove (northwest of Bar Harbor). The forest fire was one of a series of fires that consumed much of Maine's forest in a dry year. The fire burned until November 14, and was fought by the Coast Guard, Army Air Corps, Navy, local residents, and National Park Service employees from around the country. Sixty-seven of the historic summer cottages along Millionaires’ Row, along with 170 other homes, and five hotels were destroyed. Restoration of the park was substantially supported by the Rockefeller family. Regrowth has occurred naturally with new deciduous forests consisting of birch and aspen enhancing the colors of autumn foliage, adding diversity to tree populations, and providing for the eventual regeneration of spruce and fir forests.

Beginning on October 17, 1947, more than of Acadia National Park burned in a fire that also destroyed an additional of Mount Desert Island outside the park. The fire began along Crooked Road west of Hulls Cove (northwest of Bar Harbor). The forest fire was one of a series of fires that consumed much of Maine's forest in a dry year. The fire burned until November 14, and was fought by the Coast Guard, Army Air Corps, Navy, local residents, and National Park Service employees from around the country. Sixty-seven of the historic summer cottages along Millionaires’ Row, along with 170 other homes, and five hotels were destroyed. Restoration of the park was substantially supported by the Rockefeller family. Regrowth has occurred naturally with new deciduous forests consisting of birch and aspen enhancing the colors of autumn foliage, adding diversity to tree populations, and providing for the eventual regeneration of spruce and fir forests.

Climate

The region is characterized by a large seasonal variation in temperature with warm to hot summers that are often humid, and cold to severely cold winters. According to the Köppen climate classification system, Mount Desert Island has a warm-summer humid continental climate (''Dfb''). The average annual temperature in the park is 47.3 °F (8.5 °C). July is the warmest month with an average of 69.7 °F (20.9 °C), while January is the coldest month with an average of 23.8 °F (-4.6 °C). The record high and low temperatures are 96 °F (36 °C) and -21 °F (-29 °C), respectively. The plant

The region is characterized by a large seasonal variation in temperature with warm to hot summers that are often humid, and cold to severely cold winters. According to the Köppen climate classification system, Mount Desert Island has a warm-summer humid continental climate (''Dfb''). The average annual temperature in the park is 47.3 °F (8.5 °C). July is the warmest month with an average of 69.7 °F (20.9 °C), while January is the coldest month with an average of 23.8 °F (-4.6 °C). The record high and low temperatures are 96 °F (36 °C) and -21 °F (-29 °C), respectively. The plant hardiness zone

A hardiness zone is a geographic area defined as having a certain average annual minimum temperature, a factor relevant to the survival of many plants. In some systems other statistics are included in the calculations. The original and most wide ...

is 5b with an average annual extreme minimum air temperature of -11.4 °F (-24.1 °C).

Average annual precipitation in Bar Harbor is 55.54" (1411 mm). November is the wettest month with 5.89" (150 mm) of precipitation on average, while July is the driest month with 3.27" (83 mm). Precipitation days are spread evenly throughout the year with December averaging the most days with about 14, while August averages the least with about 9. The annual average days with precipitation is 139. Snow has been recorded from October to May, although the majority falls from December to March. The snowiest month is January with 18.3" (46 cm), and the annual average is 66.1" (167 cm).

Geology

The Cadillac Mountain Intrusive Complex is part of the Coastal Maine Magmatic Province, consisting of over a hundred mafic and

The Cadillac Mountain Intrusive Complex is part of the Coastal Maine Magmatic Province, consisting of over a hundred mafic and felsic

In geology, felsic is a modifier describing igneous rocks that are relatively rich in elements that form feldspar and quartz.Marshak, Stephen, 2009, ''Essentials of Geology,'' W. W. Norton & Company, 3rd ed. It is contrasted with mafic rocks, whi ...

pluton

In geology, an igneous intrusion (or intrusive body or simply intrusion) is a body of intrusive igneous rock that forms by crystallization of magma slowly cooling below the surface of the Earth. Intrusions have a wide variety of forms and com ...

s associated with the Acadian Orogeny. Mount Desert Island bedrock

In geology, bedrock is solid Rock (geology), rock that lies under loose material (regolith) within the crust (geology), crust of Earth or another terrestrial planet.

Definition

Bedrock is the solid rock that underlies looser surface mater ...

consists mainly of Cadillac Mountain granite. Perthite

Perthite is used to describe an intergrowth of two feldspars: a host grain of potassium-rich alkali feldspar (near K-feldspar, KAlSi3O8, in composition) includes exsolved lamellae or irregular intergrowths of sodic alkali feldspar (near albite, Na ...

gives the granite its pinkish color. The Silurian

The Silurian ( ) is a geologic period and system spanning 24.6 million years from the end of the Ordovician Period, at million years ago ( Mya), to the beginning of the Devonian Period, Mya. The Silurian is the shortest period of the Paleozo ...

age granite ranges from 424 to 419 million years ago (Mya). Diabase

Diabase (), also called dolerite () or microgabbro,

is a mafic, holocrystalline, subvolcanic rock equivalent to volcanic basalt or plutonic gabbro. Diabase dikes and sills are typically shallow intrusive bodies and often exhibit fine-graine ...

dikes

Dyke (UK) or dike (US) may refer to:

General uses

* Dyke (slang), a slang word meaning "lesbian"

* Dike (geology), a subvertical sheet-like intrusion of magma or sediment

* Dike (mythology), ''Dikē'', the Greek goddess of moral justice

* Dikes, ...

trend north–south through the complex. Almost 300 million years of erosion followed before the deposition of glacial features during the Pleistocene. Glacial polish

Glacial polish is a characteristic of rock surfaces where glaciers have passed over bedrock, typically granite or other hard igneous or metamorphic rock. Moving ice will carry pebbles and sand grains removed from upper levels which in turn grind ...

, glacial striations, and chatter marks are evident in granitic surfaces. Other glacier-shaped features include The Bubbles (two rôche moutonnées) and the U-shaped valleys of Sargent Mountain Pond, Jordan Pond, Seal Cove Pond, Long Pond, Echo Lake, and Eagle Lake. Somes Sound is a fjard and terminal moraines form the southern end of Long Pond, Echo Lake, and Jordan Pond. Bubble Rock is an example of a glacial erratic.

Bedrock formation

More than 500 Mya, layers of mud, sand and volcanic ash were buried beneath the ocean where high pressure, heat and tectonic activity created a metamorphic rock formation called the Ellsworth Schist. White and gray quartz, feldspar, and greenchlorite

The chlorite ion, or chlorine dioxide anion, is the halite with the chemical formula of . A chlorite (compound) is a compound that contains this group, with chlorine in the oxidation state of +3. Chlorites are also known as salts of chlorous ac ...

comprise the schist, which is the oldest rock in the Mount Desert Island region. Erosion and shifting of tectonic plates eventually brought the schist to the surface.

About 450 Mya, an ancient continental fragment, or micro- terrane, called Avalonia

Avalonia was a microcontinent in the Paleozoic era. Crustal fragments of this former microcontinent underlie south-west Great Britain, southern Ireland, and the eastern coast of North America. It is the source of many of the older rocks of Wester ...

collided with North America. The collision buried the schist along with accumulations of sand and silt, creating the Bar Harbor Formation which consists of brown and gray sandstone and siltstone

Siltstone, also known as aleurolite, is a clastic sedimentary rock that is composed mostly of silt. It is a form of mudrock with a low clay mineral content, which can be distinguished from shale by its lack of fissility.Blatt ''et al.'' 1980, p ...

layers. Material from volcanic flows and ash were also deposited on the formation, creating the volcanic rock found on the Cranberry Islands. Further volcanic activity introduced igneous rocks into the Bar Harbor Formation. As the igneous intrusions cooled, crystallized minerals formed including a gabbro composed of dark, iron-rich minerals.

Mount Desert Island granite was created about 420 Mya, with one of the oldest granite bodies being Cadillac Mountain, the largest on the island. The granite body rose slowly through bedrock, fracturing it into large pieces, some of which melted under intense heat. As the granite cooled, the bedrock fragments were left surrounded by crystallized granite in a shatter zone that is visible on the eastern side of the mountain. A fine-grained, black igneous rock called diabase intruded into the granite during later volcanic activity. Diabase bodies, or dikes, are visible along the Cadillac Mountain road and on the Schoodic Peninsula.

During the next several hundred million years, the rock layers that still covered the large granite bodies, along with softer rock surrounding the granite, were worn away by erosion.

Mount Desert Island granite was created about 420 Mya, with one of the oldest granite bodies being Cadillac Mountain, the largest on the island. The granite body rose slowly through bedrock, fracturing it into large pieces, some of which melted under intense heat. As the granite cooled, the bedrock fragments were left surrounded by crystallized granite in a shatter zone that is visible on the eastern side of the mountain. A fine-grained, black igneous rock called diabase intruded into the granite during later volcanic activity. Diabase bodies, or dikes, are visible along the Cadillac Mountain road and on the Schoodic Peninsula.

During the next several hundred million years, the rock layers that still covered the large granite bodies, along with softer rock surrounding the granite, were worn away by erosion.

Glaciation

During the last two to three million years, a series of ice sheets flowed and receded across northern North America, eroding mountains and creating U-shaped valleys.

The glacier that covered Mount Desert Range, part of which is now called Mount Desert Island, was thick and moved at the rate of a few yards (meters) per year. The mountain range was heavily eroded by the glacier which rounded off mountaintops, carved saddles, deepened valleys, and created the fjard known as Somes Sound, nearly dividing the current island in half."The Story of Glaciers"

During the last two to three million years, a series of ice sheets flowed and receded across northern North America, eroding mountains and creating U-shaped valleys.

The glacier that covered Mount Desert Range, part of which is now called Mount Desert Island, was thick and moved at the rate of a few yards (meters) per year. The mountain range was heavily eroded by the glacier which rounded off mountaintops, carved saddles, deepened valleys, and created the fjard known as Somes Sound, nearly dividing the current island in half."The Story of Glaciers". ''nps.gov''. National Park Service. Retrieved December 7, 2018.

Erosion and weathering

Acadia has a coastline composed of rocky

Acadia has a coastline composed of rocky headland

A headland, also known as a head, is a coastal landform, a point of land usually high and often with a sheer drop, that extends into a body of water. It is a type of promontory. A headland of considerable size often is called a cape.Whittow, John ...

s, and more heavily eroded stony or sandy beaches. Coastal areas directly facing the wind-driven waves of the Atlantic Ocean are solely composed of large boulders as all other material has been washed out to sea. Areas partially protected by rocky headlands contain the remains of more eroded rocks, consisting of pebbles, cobbles

Cobblestone is a natural building material based on cobble-sized stones, and is used for pavement roads, streets, and buildings.

Setts, also called Belgian blocks, are often casually referred to as "cobbles", although a sett is distinct fro ...

and smaller boulders. Sheltered coves, such as at Sand Beach, contain fine-grained particles that are primarily the remains of shells and other hard parts of marine life, including mussel

Mussel () is the common name used for members of several families of bivalve molluscs, from saltwater and Freshwater bivalve, freshwater habitats. These groups have in common a shell whose outline is elongated and asymmetrical compared with other ...

s and sea urchin

Sea urchins () are spiny, globular echinoderms in the class Echinoidea. About 950 species of sea urchin live on the seabed of every ocean and inhabit every depth zone from the intertidal seashore down to . The spherical, hard shells (tests) of ...

s.

Granitic ridges are subjected to frost weathering

Frost weathering is a collective term for several mechanical weathering processes induced by stresses created by the freezing of water into ice. The term serves as an umbrella term for a variety of processes such as frost shattering, frost wedg ...

. Joints, or fractures, are slowly enlarged as trapped water repeatedly freezes and melts, eventually splitting off a block. Bright pink scars with granitic rubble below are evidence of such weathering; one example can be seen above the Tarn, a pond just south of Bar Harbor.

At least twelve sea caves are located in several coastal areas of the park. Sea caves are formed when waves cause erosion of coastal rock formations. If a sea cave is enlarged enough, it may break through a headland

A headland, also known as a head, is a coastal landform, a point of land usually high and often with a sheer drop, that extends into a body of water. It is a type of promontory. A headland of considerable size often is called a cape.Whittow, John ...

to form a sea arch

A natural arch, natural bridge, or (less commonly) rock arch is a natural landform where an arch has formed with an opening underneath. Natural arches commonly form where inland cliffs, coastal cliffs, fins or stacks are subject to erosion fr ...

.

Mass wasting and slope failure

Frequent thawing in winter prevents large accumulations of snow, and keeps the ground well saturated. Ice storms are common in winter and early spring, while rain occurs throughout the year. Saturated soils, thawing, and heavy precipitation lead to rockfalls every spring along Mount Desert Island's loop road, as well as

Frequent thawing in winter prevents large accumulations of snow, and keeps the ground well saturated. Ice storms are common in winter and early spring, while rain occurs throughout the year. Saturated soils, thawing, and heavy precipitation lead to rockfalls every spring along Mount Desert Island's loop road, as well as slumping

Slumping is a technique in which items are made in a kiln by means of shaping glass over molds at high temperatures.

The slumping of a pyrometric cone is often used to measure temperature in a kiln.

Technique

Slumping glass is a highly techni ...

along coastal bluffs.

Mass wasting (slope movement) of marine clay

Marine clay is a type of clay found in coastal regions around the world. In the northern, deglaciated regions, it can sometimes be quick clay, which is notorious for being involved in landslides.

Marine clay is a particle of soil that is dedica ...

, deposited when the sea level was much higher, occurs along Hunters Brook on Mount Desert Island. Slumping of the greenish-gray clay destabilized the bank, changing the course of the stream. The eastern end of Otter Cove's beach contains eroded gullies of marine clay. Mass wasting and slope failure may occur wherever marine clay is exposed.

Seismic activity

Earthquakes with epicenters near the park have caused landslides, damaging roads and trails. Earthquakes in Maine occur at a low but steady rate, with magnitudes usually less than 4.8 on the Richter scale.Paleontology

The Presumpscot Formation has yielded a diverse collection of mostly marine fossils. The formation is composed of silt and clay deposited between 15 and 11,000 years ago when isostatic loading raised sea level as land was submerged to about above the current level. Post-glacial rebound lowered sea level, exposing the seabed to a depth of about below the current level. A global rise in sea-level flooded theshelf

Shelf ( : shelves) may refer to:

* Shelf (storage), a flat horizontal surface used for display and storage

Geology

* Continental shelf, the extended perimeter of a continent, usually covered by shallow seas

* Ice shelf, a thick platform of ice f ...

to the current level.

Plant fossils include pollen

Pollen is a powdery substance produced by seed plants. It consists of pollen grains (highly reduced microgametophytes), which produce male gametes (sperm cells). Pollen grains have a hard coat made of sporopollenin that protects the gametophyt ...

, spore

In biology, a spore is a unit of sexual or asexual reproduction that may be adapted for dispersal and for survival, often for extended periods of time, in unfavourable conditions. Spores form part of the life cycles of many plants, algae, f ...

s, logs, and other plant macrofossils. Invertebrate fossils include foraminifera ( protists that form test shells), sponge spicules, bryozoans, bivalves

Bivalvia (), in previous centuries referred to as the Lamellibranchiata and Pelecypoda, is a class of marine and freshwater molluscs that have laterally compressed bodies enclosed by a shell consisting of two hinged parts. As a group, bival ...

, gastropods, '' Spirorbis'', beetles, ants, barnacle

A barnacle is a type of arthropod constituting the subclass Cirripedia in the subphylum Crustacea, and is hence related to crabs and lobsters. Barnacles are exclusively marine, and tend to live in shallow and tidal waters, typically in eros ...

s, decapod crustaceans (crab

Crabs are decapod crustaceans of the infraorder Brachyura, which typically have a very short projecting "tail" (abdomen) ( el, βραχύς , translit=brachys = short, / = tail), usually hidden entirely under the thorax. They live in all the ...

s, shrimp

Shrimp are crustaceans (a form of shellfish) with elongated bodies and a primarily swimming mode of locomotion – most commonly Caridea and Dendrobranchiata of the decapod order, although some crustaceans outside of this order are refer ...

, lobster

Lobsters are a family (biology), family (Nephropidae, Synonym (taxonomy), synonym Homaridae) of marine crustaceans. They have long bodies with muscular tails and live in crevices or burrows on the sea floor. Three of their five pairs of legs ...

s, etc.), ostracodes (seed shrimp), and ophiuroids ( brittle stars). Vertebrate fossils include fish and a few rare large mammals, such as walruses, whales, and a mammoth. Walrus remains have been reported on Andrews Island, west of Isle au Haut; Addison Point, northeast of the Schoodic Peninsula; and Gardiner Gardiner may refer to:

Places

Settlements

;Canada

* Gardiner, Ontario

;United States

* Gardiner, Maine

* Gardiner, Montana

* Gardiner (town), New York

** Gardiner (CDP), New York

* Gardiner, Oregon

* Gardiner, Washington

* West Gardiner, Maine

...

, west-northwest of Isle au Haut. The mammoth bones were found at Scarborough, southwest of Isle au Haut.

Ecology

The ecological zones at Acadia National Park, from highest to lowest elevation, include: nearly barren mountain

The ecological zones at Acadia National Park, from highest to lowest elevation, include: nearly barren mountain summit

A summit is a point on a surface that is higher in elevation than all points immediately adjacent to it. The topography, topographic terms acme, apex, peak (mountain peak), and zenith are synonymous.

The term (mountain top) is generally used ...

s; northern boreal

Boreal may refer to:

Climatology and geography

*Boreal (age), the first climatic phase of the Blytt-Sernander sequence of northern Europe, during the Holocene epoch

*Boreal climate, a climate characterized by long winters and short, cool to mild ...

and eastern deciduous forests on the mountainsides; freshwater lakes and ponds, as well as wetlands like marshes and swamp

A swamp is a forested wetland.Keddy, P.A. 2010. Wetland Ecology: Principles and Conservation (2nd edition). Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK. 497 p. Swamps are considered to be transition zones because both land and water play a role in ...

s in the valleys between mountains; and the Atlantic shoreline with rocky and sandy beaches, intertidal and subtidal zones.

Tiny subalpine plants grow in the granite joints on mountaintops and on the downwind side of rocks. Stunted, gnarled trees also survive near the summits. Spruce

A spruce is a tree of the genus ''Picea'' (), a genus of about 35 species of coniferous evergreen trees in the family Pinaceae, found in the northern temperate and boreal (taiga) regions of the Earth. ''Picea'' is the sole genus in the subfami ...

-fir

Firs (''Abies'') are a genus of 48–56 species of evergreen coniferous trees in the family (biology), family Pinaceae. They are found on mountains throughout much of North America, North and Central America, Europe, Asia, and North Africa. The ...

boreal forests cover much of the park. Stands of oak, maple, beech

Beech (''Fagus'') is a genus of deciduous trees in the family Fagaceae, native to temperate Europe, Asia, and North America. Recent classifications recognize 10 to 13 species in two distinct subgenera, ''Engleriana'' and ''Fagus''. The ''Engle ...

, and other hardwood

Hardwood is wood from dicot trees. These are usually found in broad-leaved temperate and tropical forests. In temperate and boreal latitudes they are mostly deciduous, but in tropics and subtropics mostly evergreen. Hardwood (which comes from ...

s more typical of New England represent the eastern deciduous forest. Pitch pine

''Pinus rigida'', the pitch pine, is a small-to-medium-sized pine. It is native to eastern North America, primarily from central Maine south to Georgia and as far west as Kentucky. It is found in environments which other species would find unsuit ...

s and scrub oak Scrub oak is a common name for several species of small, shrubby oaks. It may refer to:

*the Chaparral plant community in California, or to one of the following species.

In California

*California scrub oak (''Quercus berberidifolia''), a widespr ...

s inhabit isolated forests at their northeastern range limit, while jack pines reach the southern limit of their range in Acadia.

Fourteen great ponds and ten smaller ponds provide habitat for many fish and waterfowl species. More than 20% of the park is classified as wetland. Marshes and swamps form the transition between terrestrial and aquatic environments, maintaining biodiversity by providing a habitat for a wide range of species. Native wildlife frequent wetlands alongside species that are nesting, overwintering or migrating, such as birds along the Atlantic Flyway. Wetlands are composed of 37.5% marine

Marine is an adjective meaning of or pertaining to the sea or ocean.

Marine or marines may refer to:

Ocean

* Maritime (disambiguation)

* Marine art

* Marine biology

* Marine debris

* Marine habitats

* Marine life

* Marine pollution

Military

* ...

(sea water), 31.6% palustrine (stagnant water), 20% estuarine

An estuary is a partially enclosed coastal body of brackish water with one or more rivers or streams flowing into it, and with a free connection to the open sea. Estuaries form a transition zone between river environments and maritime environment ...

(coastal, brackish water), 10.7% lacustrine (freshwater lakes and ponds), and 0.2% riverine (flowing streams). Approximately of perennial streams and of intermittent streams flow through the park, while about of shoreline surround 110 lakes and ponds encompassing .

Intertidal flora and fauna inhabit more than of rocky coastline. The nutrient-rich marine waters cover the intertidal plants and animals twice a day. Pools of calm water form among the rocks around low tides, inhabited by starfish

Starfish or sea stars are star-shaped echinoderms belonging to the class Asteroidea (). Common usage frequently finds these names being also applied to ophiuroids, which are correctly referred to as brittle stars or basket stars. Starfish ...

, dog whelks, blue mussels, sea cucumber

Sea cucumbers are echinoderms from the class Holothuroidea (). They are marine animals with a leathery skin and an elongated body containing a single, branched gonad. Sea cucumbers are found on the sea floor worldwide. The number of holothuria ...

s, and rockweed.

Flora

Flora common to both deciduous and

Flora common to both deciduous and coniferous

Conifers are a group of cone-bearing seed plants, a subset of gymnosperms. Scientifically, they make up the division Pinophyta (), also known as Coniferophyta () or Coniferae. The division contains a single extant class, Pinopsida. All extant ...

woodlands include lowbush blueberry

Blueberries are a widely distributed and widespread group of perennial flowering plants with blue or purple berries. They are classified in the section ''Cyanococcus'' within the genus ''Vaccinium''. ''Vaccinium'' also includes cranberries, bi ...

, Canadian bunchberry, hobblebush

''Viburnum lantanoides'' (commonly known as hobble-bush, witch-hobble, alder-leaved viburnum, American wayfaring tree, and moosewood) is a perennial shrub of the family Adoxaceae (formerly in the Caprifoliaceae), growing 2–4 meters (6–12&nbs ...

, bluebead lily, Canada mayflower

''Maianthemum canadense'' (Canadian may-lily, Canada mayflower, false lily-of-the-valley, Canadian lily-of-the-valley, wild lily-of-the-valley,, p.105 two-leaved Solomon's seal)

is an understory perennial flowering plant, native to Canada and the ...

, wild sarsaparilla

''Aralia nudicaulis'' (commonly wild sarsaparilla,Dickinson, T.; Metsger, G.; Hull, J.; and Dickinson, R. (2004) The ROM Field Guide to Wildflowers of Ontario. Toronto:Royal Ontario Museum, p. 140. false sarsaparilla, shot bush, small spikenard, ...

, shadbush

''Amelanchier'' ( ), also known as shadbush, shadwood or shadblow, serviceberry or sarvisberry (or just sarvis), juneberry, saskatoon, sugarplum, wild-plum or chuckley pear,A Digital Flora of Newfoundland and Labrador Vascular Plants/ref> is a g ...

, starflower, rosy twisted stalk, wintergreen

Wintergreen is a group of aromatic plants. The term "wintergreen" once commonly referred to plants that remain green (continue photosynthesis) throughout the winter. The term "evergreen" is now more commonly used for this characteristic.

Mos ...

, and white pine trees."Common Native Plants". ''nps.gov''. National Park Service. July 15, 2016. Retrieved December 3, 2018.

potential natural vegetation

In ecology, potential natural vegetation (PNV), also known as Kuchler potential vegetation, is the vegetation that would be expected given environmental constraints (climate, geomorphology, geology) without human intervention or a hazard event ...

of northeastern spruce

A spruce is a tree of the genus ''Picea'' (), a genus of about 35 species of coniferous evergreen trees in the family Pinaceae, found in the northern temperate and boreal (taiga) regions of the Earth. ''Picea'' is the sole genus in the subfami ...

/fir

Firs (''Abies'') are a genus of 48–56 species of evergreen coniferous trees in the family (biology), family Pinaceae. They are found on mountains throughout much of North America, North and Central America, Europe, Asia, and North Africa. The ...

within temperate coniferous forests, according to the original A. W. Kuchler August William Kuchler (born ''August Wilhelm Küchler''; 1907–1999) was a German-born American geographer and naturalist who is noted for developing a plant association system in widespread use in the United States. Some of this database has beco ...

types. Spruce-fir forests cover more than sixty percent of the naturally vegetated habitats in the park. Other coniferous forest plants include dewdrop, mountain holly Mountain holly is a common name for several plants and may refer to:

* ''Olearia macrodonta'', endemic to New Zealand

* ''Ilex montana'', native to eastern North America

* ''Ilex mucronata

''Ilex mucronata'', the mountain holly or catberry, is a ...

, pinesap, one-flowered pyrola, shinleaf, trailing arbutus

''Epigaea repens'', the mayflower, trailing arbutus, or ground laurel, is a low, spreading shrub in the family Ericaceae. It is found from Newfoundland to Florida, west to Kentucky and the Northwest Territories.

Description

The plant is a slo ...

, northern woodsorrel, and drooping woodreed.

An invasive insect known as the red pine scale

Scale or scales may refer to:

Mathematics

* Scale (descriptive set theory), an object defined on a set of points

* Scale (ratio), the ratio of a linear dimension of a model to the corresponding dimension of the original

* Scale factor, a number ...

was confirmed on dying red pines on the south side of Norumbega Mountain near Lower Hadlock Pond in 2014.

Deciduous forest trees include the white ash, big-toothed and trembling aspen, American beech

''Fagus grandifolia'', the American beech or North American beech, is a species of beech tree native to the eastern United States and extreme southeast of Canada.

Description

''Fagus grandifolia'' is a large deciduous tree growing to tall, w ...

, paper and yellow birch, red oak, American mountain ash

The tree species ''Sorbus americana'' is commonly known as the American mountain-ash. It is a deciduous perennial tree, native to eastern North America.

The American mountain-ash and related species (most often the European mountain-ash, '' Sorb ...

, as well as mountain, red, striped, and sugar maples. Other deciduous forest plants include large-leaved aster, chokecherry

''Prunus virginiana'', commonly called bitter-berry, chokecherry, Virginia bird cherry, and western chokecherry (also black chokecherry for ''P. virginiana'' var. ''demissa''), is a species of bird cherry (''Prunus'' subgenus ''Padus'') nat ...

, red-berried elder

''Sambucus racemosa'' is a species of elderberry known by the common names red elderberry and red-berried elder.

Distribution and habitat

It is native to Europe, northern temperate Asia, and North America across Canada and the United States. It ...

, Christmas fern

''Polystichum acrostichoides'', commonly denominated Christmas fern, is a perennial, evergreen fern native to eastern North America, from Nova Scotia west to Minnesota and south to Florida and eastern Texas.threeleaf goldthread, early saxifrage, false Solomon's seal, small Solomon's seal, and twinflower.

Trees commonly found in the mountains and dry, rocky places of the national park include gray birch,

common juniper

''Juniperus communis'', the common juniper, is a species of small tree or shrub in the cypress family Cupressaceae. An evergreen conifer, it has the largest geographical range of any woody plant, with a circumpolar distribution throughout the c ...

, jack pine, and pitch pine

''Pinus rigida'', the pitch pine, is a small-to-medium-sized pine. It is native to eastern North America, primarily from central Maine south to Georgia and as far west as Kentucky. It is found in environments which other species would find unsuit ...

, while smaller trees, or shrub, species include green alder

''Alnus alnobetula'' is a common tree widespread across much of Europe, Asia, and North America. Many sources refer to it as ''Alnus viridis'', the green alder, but botanically this is considered an illegitimate name synonymous with ''Alnus alnob ...

and pin cherry

''Prunus pensylvanica'', also known as bird cherry, fire cherry, pin cherry, and red cherry, is a North American cherry species in the genus ''Prunus''.

Description

''Prunus pensylvanica'' grows as a shrub or small tree, usually with a straigh ...

. Other common shrubs and flowering plants found in the mountains and rocky areas include alpine aster

''Aster alpinus'', the alpine aster or blue alpine daisy, is a species of flowering plant in the family Asteraceae, native to the mountains of Europe (including the Alps), with a subspecies native to Canada and the United States. This herbaceous ...

, bearberry, velvetleaf blueberry, bush-honeysuckle, black chokeberry

''Aronia melanocarpa'', called the black chokeberry, is a species of shrubs in the rose family native to eastern North America, ranging from Canada to the central United States, from Newfoundland west to Ontario and Minnesota, south as far as ...

, three-toothed cinquefoil

''Sibbaldiopsis'' is a genus in the plant family Rosaceae. This genus only contains a single species: ''Sibbaldiopsis tridentata'', formerly ''Potentilla tridentata''. Commonly, its names include three-toothed cinquefoil, shrubby fivefingers, and ...

, mountain cranberry, bracken fern, Rand's goldenrod, harebell, golden heather, mountain holly Mountain holly is a common name for several plants and may refer to:

* ''Olearia macrodonta'', endemic to New Zealand

* ''Ilex montana'', native to eastern North America

* ''Ilex mucronata

''Ilex mucronata'', the mountain holly or catberry, is a ...

, black huckleberry Black huckleberry is a common name for several plants and may refer to:

*''Gaylussacia baccata'', native to eastern North America

*''Vaccinium membranaceum

''Vaccinium membranaceum'' is a species within the group of Vaccinium commonly referred t ...

, creeping juniper, sheep laurel

''Kalmia angustifolia'' is a flowering shrub in the family Ericaceae, commonly known as sheep laurel. It is distributed in eastern North America from Ontario and Quebec south to Virginia. It grows commonly in dry habitats in the boreal forest, ...

, red raspberry, Virginia rose

''Rosa virginiana'', commonly known as the Virginia rose, common wild rose or prairie rose, is a woody perennial in the rose family native to eastern North America, where it is the most common wild rose. It is deciduous, forming a suckering shru ...

, mountain sandwort, bristly sarsaparilla, sweetfern

''Comptonia peregrina'' is a species of flowering plant in the family Myricaceae. It is the only extant (living) species in the genus '' Comptonia'', although a number of extinct species are placed in the genus. ''Comptonia peregrina'' is native ...

, and wild raisin

''Viburnum nudum'' is a deciduous shrub in the genus ''Viburnum'' within the muskroot family, Adoxaceae (It was formerly part of Caprifoliaceae, the honeysuckle family).

. Poverty oatgrass

''Danthonia spicata'' is a species of grass known by the common name poverty oatgrass, or simply poverty grass. It is native to North America, where it is widespread and common in many areas.

archive

. pp. 28, 41 (of PDF file). ''nps.gov''. National Park Service. September 2016. Retrieved December 20, 2018. Plant,

The park is inhabited by 37

The park is inhabited by 37

''nps.gov''. National Park Service. June 25, 2015. Retrieved December 5, 2018. "Species listed here are based on the ''Checklist'' results, not the ''Full list'' results. For mammals, the full list contains eleven unconfirmed species such as the

Bog

A bog or bogland is a wetland that accumulates peat as a deposit of dead plant materials often mosses, typically sphagnum moss. It is one of the four main types of wetlands. Other names for bogs include mire, mosses, quagmire, and muskeg; a ...

plants include bog aster, bog rosemary

''Andromeda polifolia'', common name bog-rosemary, is a species of flowering plant in the heath family Ericaceae, native to northern parts of the Northern Hemisphere. It is the only member of the genus ''Andromeda'', and is only found in bogs in ...

, cottongrass

''Eriophorum'' (cottongrass, cotton-grass or cottonsedge) is a genus of flowering plants in the family Cyperaceae, the sedge family. They are found throughout the arctic, subarctic, and temperate portions of the Northern Hemisphere in acid bog h ...

, large cranberry, small cranberry

''Vaccinium oxycoccos'' is a species of flowering plant in the heath family. It is known as small cranberry, marshberry, bog cranberry, swamp cranberry, or, particularly in Britain, just cranberry. It is widespread throughout the cool temperate ...

, bog goldenrod, dwarf huckleberry, blue flag, Labrador-tea, bog laurel, leatherleaf

''Chamaedaphne calyculata'', known commonly as leatherleaf or cassandra, is a perennial dwarf shrub in the plant family Ericaceae and the only species in the genus ''Chamaedaphne''. It is commonly seen in cold, acidic bogs and forms large, spread ...

, pitcher plant, rhodora, bristly rose, creeping snowberry Creeping snowberry is a common name for several plants and may refer to:

* ''Gaultheria hispidula''

* '' Symphoricarpos hesperius''

* '' Symphoricarpos mollis''

ReferencesCreeping snowberryat Integrated Taxonomic Information System

The Integra ...

, round-leaved sundew

''Drosera rotundifolia'', the round-leaved sundew, roundleaf sundew, or common sundew, is a carnivorous species of flowering plant that grows in bogs, marshes and fens. One of the most widespread sundew species, it has a circumboreal distribution ...

, spatulate-leaved sundew, and sweetgale