World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a

world war

A world war is an international conflict which involves all or most of the world's major powers. Conventionally, the term is reserved for two major international conflicts that occurred during the first half of the 20th century, World WarI (1914 ...

that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the

vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the

great powers—forming two opposing

military alliance

A military alliance is a formal agreement between nations concerning national security. Nations in a military alliance agree to active participation and contribution to the defense of others in the alliance in the event of a crisis. (Online) ...

s: the

Allies

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are called ...

and the

Axis powers

The Axis powers, ; it, Potenze dell'Asse ; ja, 枢軸国 ''Sūjikukoku'', group=nb originally called the Rome–Berlin Axis, was a military coalition that initiated World War II and fought against the Allies. Its principal members were ...

. World War II was a

total war

Total war is a type of warfare that includes any and all civilian-associated resources and infrastructure as legitimate military targets, mobilizes all of the resources of society to fight the war, and gives priority to warfare over non-combata ...

that directly involved more than 100 million

personnel from more than 30 countries.

The major participants in the war threw their entire economic, industrial, and scientific capabilities behind the

war effort

In politics and military planning, a war effort is a coordinated mobilization of society's resources—both industrial and human—towards the support of a military force. Depending on the militarization of the culture, the relative si ...

, blurring the distinction between civilian and military resources.

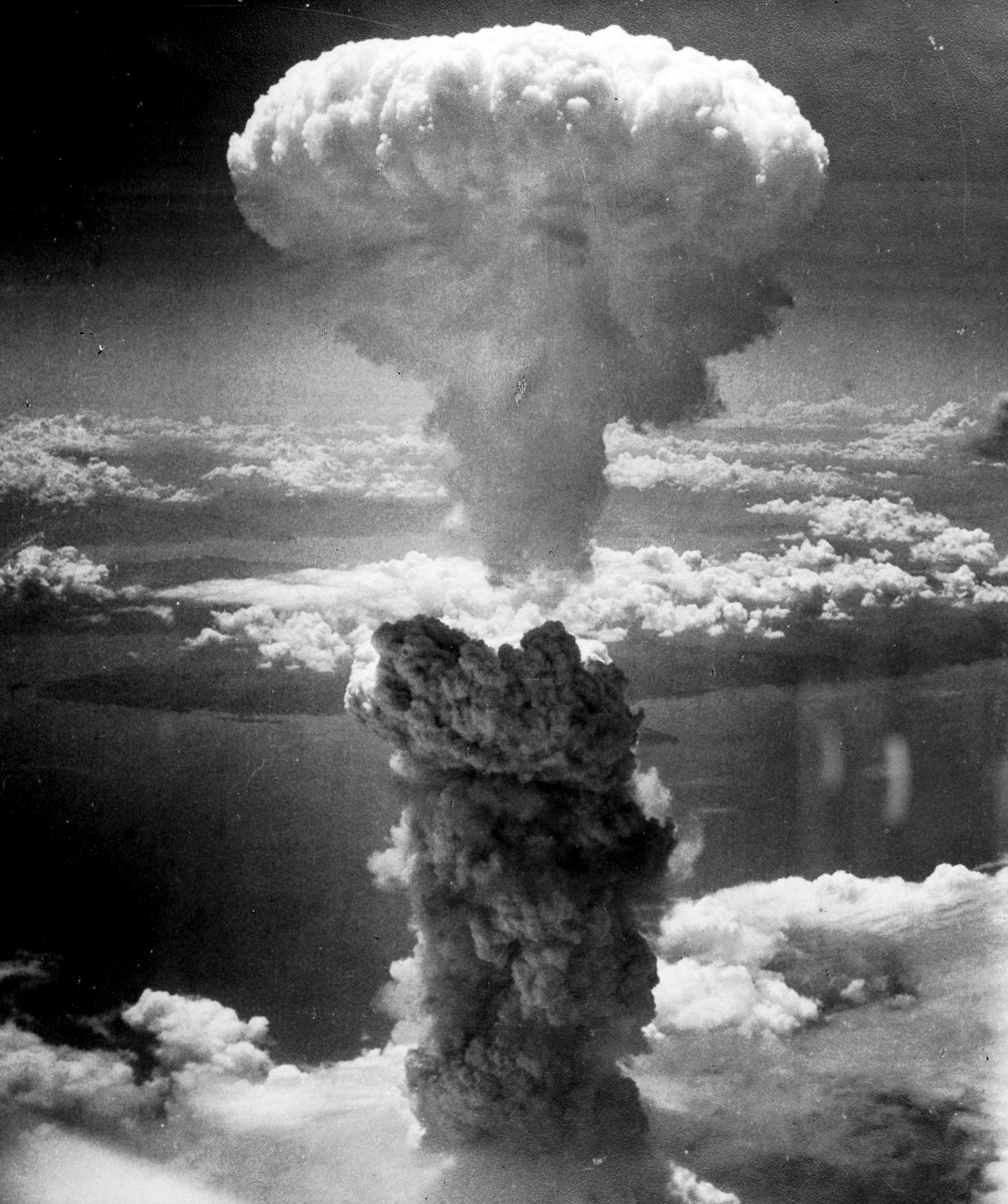

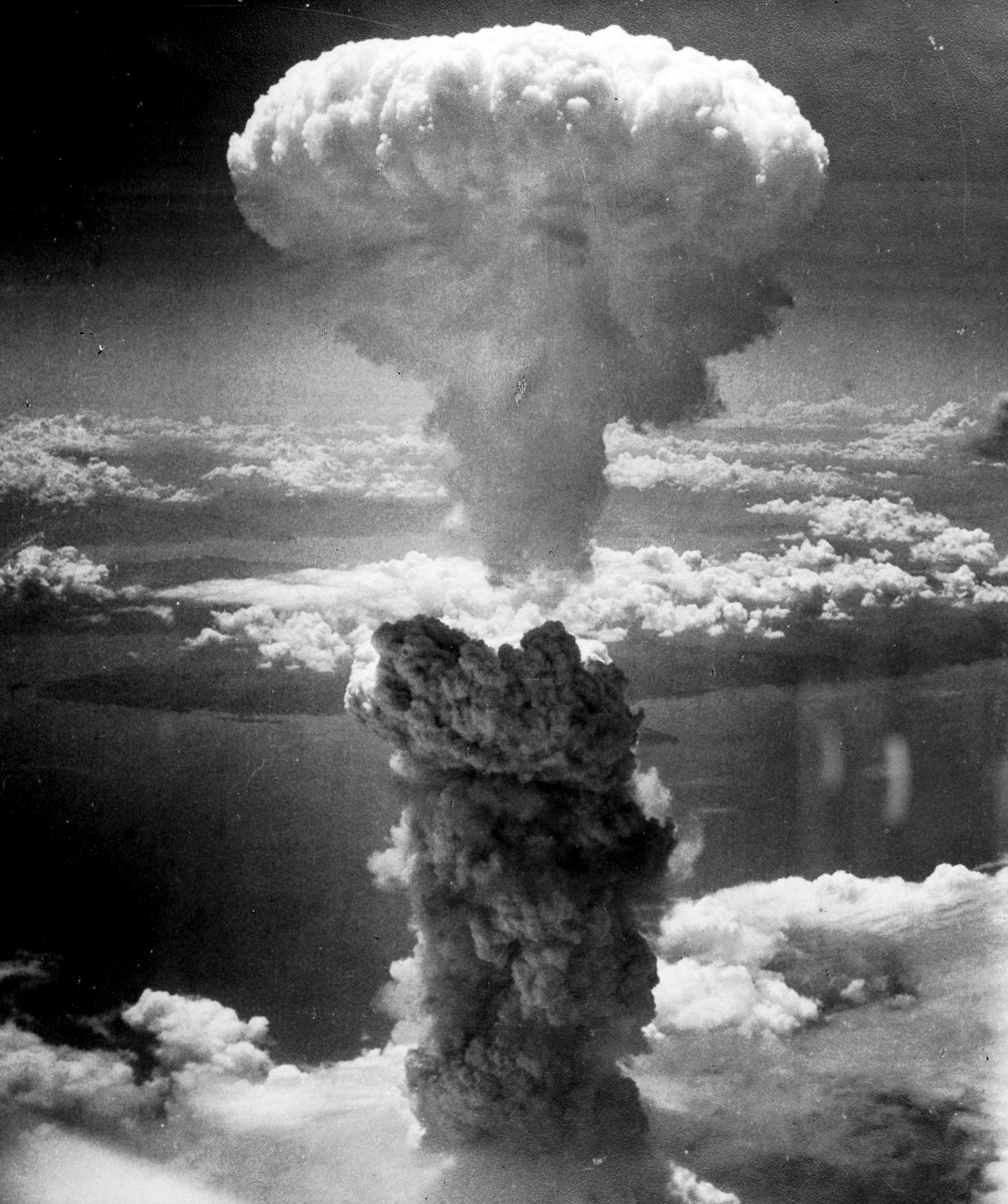

Aircraft played a major role in the conflict, enabling the

strategic bombing

Strategic bombing is a military strategy used in total war with the goal of defeating the enemy by destroying its morale, its economic ability to produce and transport materiel to the theatres of military operations, or both. It is a systematica ...

of population centres and deploying the

only two nuclear weapons ever used in war.

World War II was by far the

deadliest conflict in human history; it resulted in

70 to 85 million fatalities, mostly among civilians. Tens of millions died due to

genocide

Genocide is the intentional destruction of a people—usually defined as an ethnic, national, racial, or religious group—in whole or in part. Raphael Lemkin coined the term in 1944, combining the Greek word (, "race, people") with the Lat ...

s (including

the Holocaust

The Holocaust, also known as the Shoah, was the genocide of European Jews during World War II. Between 1941 and 1945, Nazi Germany and its collaborators systematically murdered some six million Jews across German-occupied Europe; ...

),

starvation,

massacre

A massacre is the killing of a large number of people or animals, especially those who are not involved in any fighting or have no way of defending themselves. A massacre is generally considered to be morally unacceptable, especially when per ...

s, and

disease

A disease is a particular abnormal condition that negatively affects the structure or function of all or part of an organism, and that is not immediately due to any external injury. Diseases are often known to be medical conditions that a ...

. In the wake of the Axis defeat,

Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

and

Japan were occupied, and

war crimes tribunals were conducted

against German and

Japanese leaders.

The

causes of World War II are debated, but contributing factors included the

Second Italo-Ethiopian War

The Second Italo-Ethiopian War, also referred to as the Second Italo-Abyssinian War, was a war of aggression which was fought between Italy and Ethiopia from October 1935 to February 1937. In Ethiopia it is often referred to simply as the Itali ...

,

Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War ( es, Guerra Civil Española)) or The Revolution ( es, La Revolución, link=no) among Nationalists, the Fourth Carlist War ( es, Cuarta Guerra Carlista, link=no) among Carlists, and The Rebellion ( es, La Rebelión, link ...

,

Second Sino-Japanese War

The Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945) or War of Resistance (Chinese term) was a military conflict that was primarily waged between the Republic of China and the Empire of Japan. The war made up the Chinese theater of the wider Pacific Th ...

,

Soviet–Japanese border conflicts

The Soviet–Japanese border conflicts, also known as the Soviet-Japanese Border War or the First Soviet-Japanese War,was a series of minor and major conflicts fought between the Soviet Union (led by Joseph Stalin), Mongolia (led by Khorloo ...

,

rise of fascism in Europe and rising European tensions since

World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

. World War II is generally considered to have begun on 1 September 1939, when

Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

, under

Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

,

invaded Poland. The

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the European mainland, continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

and

France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan area ...

subsequently

declared war

A declaration of war is a formal act by which one state announces existing or impending war activity against another. The declaration is a performative speech act (or the signing of a document) by an authorized party of a national government, i ...

on Germany on 3 September. Under the

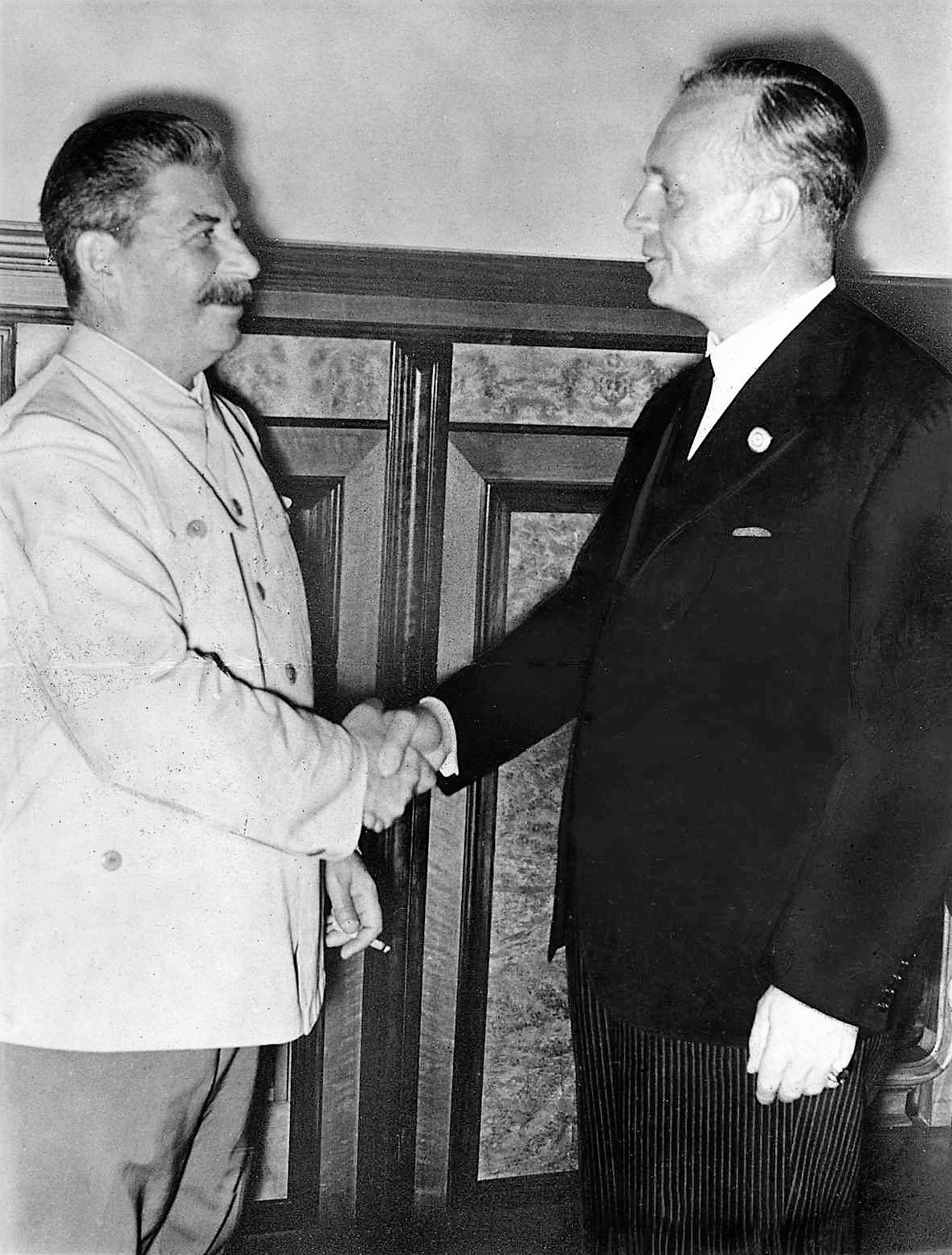

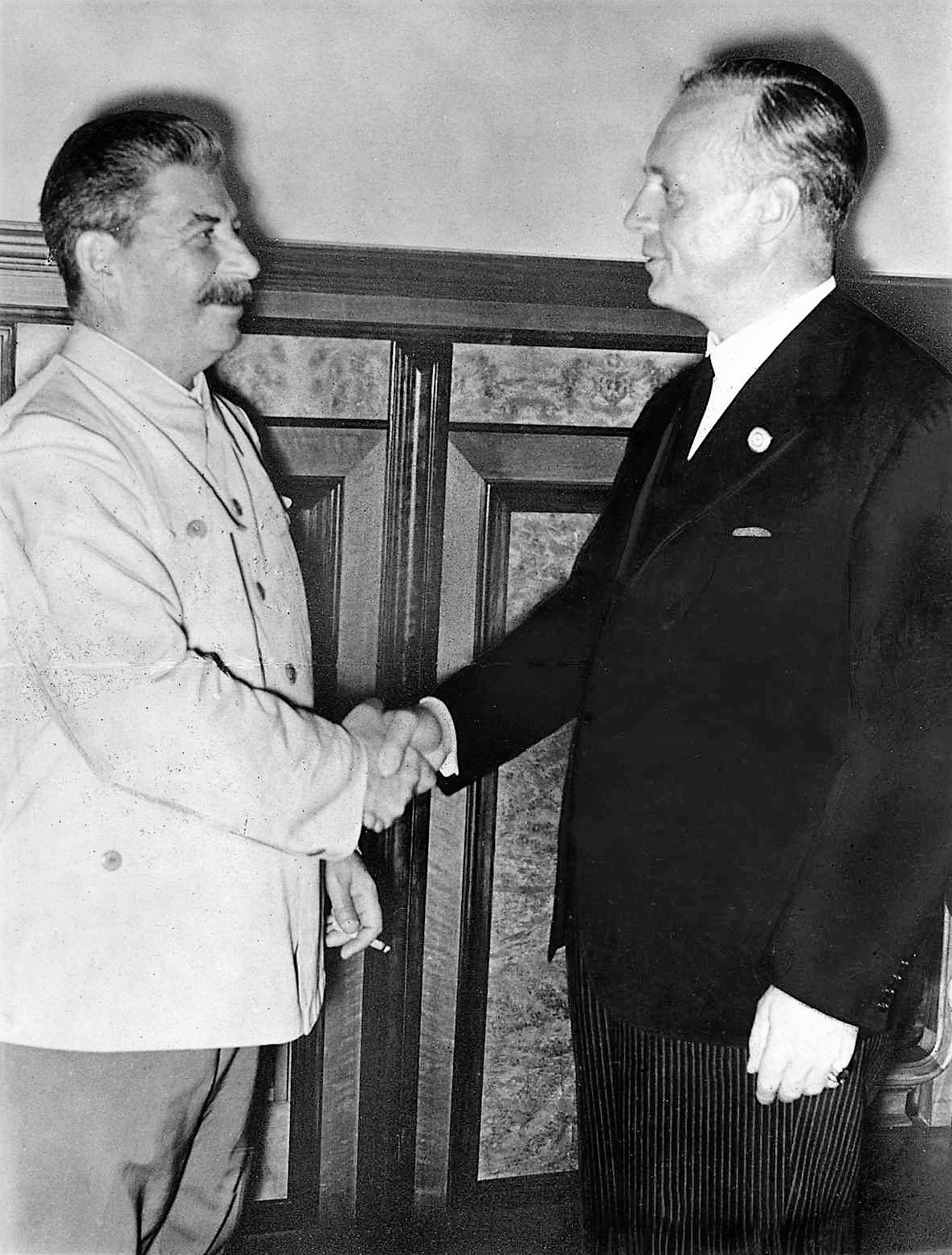

Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact

The Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact was a non-aggression pact between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union that enabled those powers to partition Poland between them. The pact was signed in Moscow on 23 August 1939 by German Foreign Minister Joachim von Ri ...

of August 1939, Germany and the

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

had partitioned

Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populou ...

and marked out their "

spheres of influence

In the field of international relations, a sphere of influence (SOI) is a spatial region or concept division over which a state or organization has a level of cultural, economic, military or political exclusivity.

While there may be a formal al ...

" across

Finland

Finland ( fi, Suomi ; sv, Finland ), officially the Republic of Finland (; ), is a Nordic country in Northern Europe. It shares land borders with Sweden to the northwest, Norway to the north, and Russia to the east, with the Gulf of B ...

,

Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania and

Romania

Romania ( ; ro, România ) is a country located at the crossroads of Central, Eastern, and Southeastern Europe. It borders Bulgaria to the south, Ukraine to the north, Hungary to the west, Serbia to the southwest, Moldova to the east, and ...

. From late 1939 to early 1941, in a series of

campaigns and

treaties

A treaty is a formal, legally binding written agreement between actors in international law. It is usually made by and between sovereign states, but can include international organizations, individuals, business entities, and other legal pers ...

, Germany conquered or controlled much of

continental Europe, and formed the Axis alliance with

Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical ...

and

Japan (with other countries later). Following the onset of campaigns in

North Africa

North Africa, or Northern Africa is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region, and it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of Mauritania in ...

and

East Africa, and the

fall of France in mid-1940, the war continued primarily between the European Axis powers and the

British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts e ...

, with war in the

Balkans

The Balkans ( ), also known as the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with various geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throughout the who ...

, the aerial

Battle of Britain

The Battle of Britain, also known as the Air Battle for England (german: die Luftschlacht um England), was a military campaign of the Second World War, in which the Royal Air Force (RAF) and the Fleet Air Arm (FAA) of the Royal Navy defende ...

,

the Blitz

The Blitz was a German bombing campaign against the United Kingdom in 1940 and 1941, during the Second World War. The term was first used by the British press and originated from the term , the German word meaning 'lightning war'.

The Germa ...

of the United Kingdom, and the

Battle of the Atlantic. On 22 June 1941, Germany led the European Axis powers in

an invasion of the Soviet Union, opening the

Eastern Front, the largest land

theatre of war

In warfare, a theater or theatre is an area in which important military events occur or are in progress. A theater can include the entirety of the airspace, land and sea area that is or that may potentially become involved in war operations.

T ...

in history.

Japan, which aimed to

dominate Asia and the Pacific, was

at war with the

Republic of China by 1937. In December 1941, Japan attacked American and British territories with near-simultaneous

offensives against Southeast Asia and the Central Pacific, including an

attack on the US fleet at Pearl Harbor which resulted in the

United States declaring war against Japan. The

European Axis powers declared war on the United States in solidarity. Japan soon captured much of the western Pacific, but its advances were halted in 1942 after losing the critical

Battle of Midway

The Battle of Midway was a major naval battle in the Pacific Theater of World War II that took place on 4–7 June 1942, six months after Japan's attack on Pearl Harbor and one month after the Battle of the Coral Sea. The U.S. Navy under ...

; later, Germany and Italy were

defeated in North Africa and at

Stalingrad in the Soviet Union. Key setbacks in 1943—including a series of German defeats on the Eastern Front, the

Allied invasions of Sicily and

the Italian mainland, and Allied offensives in the Pacific—cost the Axis powers their initiative and forced them into strategic retreat on all fronts. In 1944, the Western Allies

invaded German-occupied France, while the Soviet Union

regained its territorial losses and turned towards Germany and its allies. During 1944 and 1945, Japan suffered reversals in mainland Asia, while the Allies crippled the

Japanese Navy

, abbreviated , also simply known as the Japanese Navy, is the maritime warfare branch of the Japan Self-Defense Forces, tasked with the naval defense of Japan. The JMSDF was formed following the dissolution of the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) ...

and captured key western Pacific islands.

The war in Europe concluded with the liberation of

German-occupied territories and the

invasion of Germany by the Western Allies and the Soviet Union, culminating in the

Fall of Berlin to Soviet troops,

Hitler's suicide, and the German

unconditional surrender

An unconditional surrender is a surrender in which no guarantees are given to the surrendering party. It is often demanded with the threat of complete destruction, extermination or annihilation.

In modern times, unconditional surrenders most ofte ...

on

8 May 1945. Following the refusal of Japan to surrender on the terms of the

Potsdam Declaration

The Potsdam Declaration, or the Proclamation Defining Terms for Japanese Surrender, was a statement that called for the surrender of all Japanese armed forces during World War II. On July 26, 1945, United States President Harry S. Truman, Uni ...

(issued 26 July 1945), the United States

dropped the first atomic bombs on the Japanese cities of

Hiroshima on 6 August and

Nagasaki

is the capital and the largest Cities of Japan, city of Nagasaki Prefecture on the island of Kyushu in Japan.

It became the sole Nanban trade, port used for trade with the Portuguese and Dutch during the 16th through 19th centuries. The Hi ...

on 9 August. Faced with an imminent

invasion of the Japanese archipelago, the possibility of additional atomic bombings, and the Soviet Union's declared entry into the war against Japan on the eve of

invading Manchuria, Japan announced on 10 August its intention to surrender, signing

a surrender document on

2 September 1945.

World War II changed the political alignment and social structure of the globe. The

United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization whose stated purposes are to maintain international peace and security, develop friendly relations among nations, achieve international cooperation, and be a centre for harmoniz ...

was established to foster international co-operation and prevent future conflicts, with the victorious great powers—China, France, the Soviet Union, the United Kingdom, and the United States—becoming the

permanent members of its

Security Council

The United Nations Security Council (UNSC) is one of the six principal organs of the United Nations (UN) and is charged with ensuring international peace and security, recommending the admission of new UN members to the General Assembly, an ...

. The Soviet Union and the United States emerged as rival

superpowers, setting the stage for the nearly half-century-long

Cold War. In the wake of European devastation, the influence of its great powers waned, triggering the

decolonisation of Africa

The decolonisation of Africa was a process that took place in the mid-to-late 1950s to 1975 during the Cold War, with radical government changes on the continent as colonial governments made the transition to independent states. The process wa ...

and

Asia

Asia (, ) is one of the world's most notable geographical regions, which is either considered a continent in its own right or a subcontinent of Eurasia, which shares the continental landmass of Afro-Eurasia with Africa. Asia covers an are ...

. Most countries whose industries had been damaged moved towards

economic recovery and expansion. Political and economic integration, especially

in Europe, began as an effort to forestall future hostilities, end pre-war enmities and forge a sense of common identity.

Start and end dates

It is generally considered that in

Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a subcontinent of Eurasia and it is located entirel ...

World War II started on 1 September 1939, beginning with the

German invasion of Poland

The invasion of Poland (1 September – 6 October 1939) was a joint attack on the Republic of Poland by Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union which marked the beginning of World War II. The German invasion began on 1 September 1939, one week afte ...

and the United Kingdom and France's declaration of war on Germany two days later. Other dates for the beginning of the war in the Pacific include the start of the

Second Sino-Japanese War

The Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945) or War of Resistance (Chinese term) was a military conflict that was primarily waged between the Republic of China and the Empire of Japan. The war made up the Chinese theater of the wider Pacific Th ...

on 7 July 1937, or the earlier

Japanese invasion of Manchuria

The Empire of Japan's Kwantung Army invaded Manchuria on 18 September 1931, immediately following the Mukden Incident. At the war's end in February 1932, the Japanese established the puppet state of Manchukuo. Their occupation lasted until the ...

, on 19 September 1931. Others follow the British historian

A. J. P. Taylor

Alan John Percivale Taylor (25 March 1906 – 7 September 1990) was a British historian who specialised in 19th- and 20th-century European diplomacy. Both a journalist and a broadcaster, he became well known to millions through his televis ...

, who held that the Sino-Japanese War and war in Europe and its colonies occurred simultaneously, and the two wars became World War II in 1941. Other starting dates sometimes used for World War II include the

Italian invasion of Abyssinia on 3 October 1935. The British historian

Antony Beevor

Sir Antony James Beevor, (born 14 December 1946) is a British military historian. He has published several popular historical works on the Second World War and the Spanish Civil War.

Early life

Born in Kensington, Beevor was educated at tw ...

views the beginning of World WarII as the

Battles of Khalkhin Gol

The Battles of Khalkhin Gol (russian: Бои на Халхин-Голе; mn, Халхын голын байлдаан) were the decisive engagements of the undeclared Soviet–Japanese border conflicts involving the Soviet Union, Mongolia, Ja ...

fought between

Japan and the forces of

Mongolia

Mongolia; Mongolian script: , , ; lit. "Mongol Nation" or "State of Mongolia" () is a landlocked country in East Asia, bordered by Russia to the north and China to the south. It covers an area of , with a population of just 3.3 million, ...

and the

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

from May to September 1939. Others view the

Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War ( es, Guerra Civil Española)) or The Revolution ( es, La Revolución, link=no) among Nationalists, the Fourth Carlist War ( es, Cuarta Guerra Carlista, link=no) among Carlists, and The Rebellion ( es, La Rebelión, link ...

as the start or prelude to World War II.

The exact date of the war's end is also not universally agreed upon. It was generally accepted at the time that the war ended with the

armistice

An armistice is a formal agreement of warring parties to stop fighting. It is not necessarily the end of a war, as it may constitute only a cessation of hostilities while an attempt is made to negotiate a lasting peace. It is derived from the ...

of 14 August 1945 (

V-J Day

Victory over Japan Day (also known as V-J Day, Victory in the Pacific Day, or V-P Day) is the day on which Imperial Japan surrendered in World War II, in effect bringing the war to an end. The term has been applied to both of the days on ...

), rather than with the formal

surrender of Japan on 2 September 1945, which officially

ended the war in Asia. A

peace treaty between Japan and the Allies was signed in 1951. A 1990

treaty regarding Germany's future allowed the

reunification of East and West Germany to take place and resolved most post-World WarII issues. No formal peace treaty between Japan and the Soviet Union was ever signed, although the state of war between the two countries was terminated by the

Soviet–Japanese Joint Declaration of 1956

The Soviet Union did not sign the Treaty of Peace with Japan in 1951. On October 19, 1956, Japan and the Soviet Union signed a Joint Declaration providing for the end of the state of war and for the restoration of diplomatic relations between ...

, which also restored full diplomatic relations between them.

[''Texts of Soviet–Japanese Statements; Peace Declaration Trade Protocol.'']

New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

, page 2, 20 October 1956.

Subtitle: "Moscow, October 19. (UP) – Following are the texts of a Soviet–Japanese peace declaration and of a trade protocol between the two countries, signed here today, in unofficial translation from the Russian". Quote: "The state of war between the U.S.S.R. and Japan ends on the day the present declaration enters into force ..

Background

Europe

World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

had radically altered the

political

Politics (from , ) is the set of activities that are associated with making decisions in groups, or other forms of power relations among individuals, such as the distribution of resources or status. The branch of social science that stud ...

European map, with the defeat of the

Central Powers

The Central Powers, also known as the Central Empires,german: Mittelmächte; hu, Központi hatalmak; tr, İttifak Devletleri / ; bg, Централни сили, translit=Tsentralni sili was one of the two main coalitions that fought in ...

—including

Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, often referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire,, the Dual Monarchy, or Austria, was a constitutional monarchy and great power in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. It was formed with the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of ...

,

Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

,

Bulgaria

Bulgaria (; bg, България, Bǎlgariya), officially the Republic of Bulgaria,, ) is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern flank of the Balkans, and is bordered by Romania to the north, Serbia and North Macedo ...

, and the

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

—and the 1917

Bolshevik seizure of power in

Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. It is the largest country in the world, with its internationally recognised territory covering , and encompassing one-eig ...

, which led to the founding of the Soviet Union. Meanwhile, the victorious

Allies of World War I

The Allies of World War I, Entente (alliance), Entente Powers, or Allied Powers were a coalition of countries led by French Third Republic, France, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, United Kingdom, Russian Empire, Russia, King ...

, such as France,

Belgium

Belgium, ; french: Belgique ; german: Belgien officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. The country is bordered by the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Luxembourg to the southeast, France to th ...

, Italy,

Romania

Romania ( ; ro, România ) is a country located at the crossroads of Central, Eastern, and Southeastern Europe. It borders Bulgaria to the south, Ukraine to the north, Hungary to the west, Serbia to the southwest, Moldova to the east, and ...

, and

Greece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders ...

, gained territory, and new

nation-states

A nation state is a political unit where the state and nation are congruent. It is a more precise concept than "country", since a country does not need to have a predominant ethnic group.

A nation, in the sense of a common ethnicity, may i ...

were created out of the

collapse of Austria-Hungary and the

Ottoman and

Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War. ...

s.

To prevent a future world war, the

League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference that ...

was created during the

1919 Paris Peace Conference

Events

January

* January 1

** The Czechoslovak Legions occupy much of the self-proclaimed "free city" of Bratislava, Pressburg (now Bratislava), enforcing its incorporation into the new republic of Czechoslovakia.

** HMY Iolaire, HMY ''Io ...

. The organisation's primary goals were to prevent armed conflict through

collective security, military and

naval disarmament, and settling international disputes through peaceful negotiations and arbitration.

Despite strong

pacifist sentiment

after World WarI,

irredentist

Irredentism is usually understood as a desire that one state annexes a territory of a neighboring state. This desire is motivated by ethnic reasons (because the population of the territory is ethnically similar to the population of the parent st ...

and

revanchist

Revanchism (french: revanchisme, from ''revanche'', " revenge") is the political manifestation of the will to reverse territorial losses incurred by a country, often following a war or social movement. As a term, revanchism originated in 1870s F ...

nationalism

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a group of people), Smith, Anthony. ''Nationalism: The ...

emerged in several European states in the same period. These sentiments were especially marked in Germany because of the significant territorial, colonial, and financial losses imposed by the

Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles (french: Traité de Versailles; german: Versailler Vertrag, ) was the most important of the peace treaties of World War I. It ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. It was signed on 28 June ...

. Under the treaty, Germany lost around 13 percent of its home territory and all

its overseas possessions, while German annexation of other states was prohibited,

reparations

Reparation(s) may refer to:

Christianity

* Restitution (theology), the Christian doctrine calling for reparation

* Acts of reparation, prayers for repairing the damages of sin

History

*War reparations

**World War I reparations, made from G ...

were imposed, and limits were placed on the size and capability of the country's

armed forces.

The German Empire was dissolved in the

German Revolution of 1918–1919, and a democratic government, later known as the

Weimar Republic

The Weimar Republic (german: link=no, Weimarer Republik ), officially named the German Reich, was the government of Germany from 1918 to 1933, during which it was a constitutional federal republic for the first time in history; hence it is ...

, was created. The interwar period saw strife between supporters of the new republic and hardline opponents on both the

right

Rights are legal, social, or ethical principles of freedom or entitlement; that is, rights are the fundamental normative rules about what is allowed of people or owed to people according to some legal system, social convention, or ethical ...

and

left. Italy, as an Entente ally, had made some post-war territorial gains; however, Italian nationalists were angered that the

promises made by the United Kingdom and France to secure Italian entrance into the war were not fulfilled in the peace settlement. From 1922 to 1925, the

Fascist movement led by

Benito Mussolini seized power in Italy with a nationalist,

totalitarian

Totalitarianism is a form of government and a political system that prohibits all opposition parties, outlaws individual and group opposition to the state and its claims, and exercises an extremely high if not complete degree of control and reg ...

, and

class collaboration

Class collaboration is a principle of social organization based upon the belief that the division of society into a hierarchy of social classes is a positive and essential aspect of civilization.

Fascist support

Class collaboration is one of th ...

ist agenda that abolished representative democracy, repressed socialist, left-wing and liberal forces, and pursued an aggressive expansionist foreign policy aimed at making Italy a

world power

A great power is a sovereign state that is recognized as having the ability and expertise to exert its influence on a global scale. Great powers characteristically possess military and economic strength, as well as diplomatic and soft power inf ...

, and promising the creation of a "

New Roman Empire

The Italian colonial empire ( it, Impero coloniale italiano), known as the Italian Empire (''Impero Italiano'') between 1936 and 1943, began in Africa in the 19th century and comprised the colonies, protectorates, concessions and dependencie ...

".

Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

, after an

unsuccessful attempt to overthrow the German government in 1923, eventually

became the Chancellor of Germany in 1933 when

Paul Von Hindenburg

Paul Ludwig Hans Anton von Beneckendorff und von Hindenburg (; abbreviated ; 2 October 1847 – 2 August 1934) was a German field marshal and statesman who led the Imperial German Army during World War I and later became President of Germany fr ...

and the Reichstag appointed him. He abolished democracy, espousing a

radical, racially motivated revision of the world order, and soon began a massive

rearmament campaign. Meanwhile, France, to secure its alliance,

allowed Italy a free hand in Ethiopia, which Italy desired as a colonial possession. The situation was aggravated in early 1935 when the

Territory of the Saar Basin

The Territory of the Saar Basin (german: Saarbeckengebiet, ; french: Territoire du bassin de la Sarre) was a region of Germany occupied and governed by the United Kingdom and France from 1920 to 1935 under a League of Nations mandate. It had its ...

was legally reunited with Germany, and Hitler repudiated the Treaty of Versailles, accelerated his rearmament programme, and introduced

conscription.

The United Kingdom, France and Italy formed the

Stresa Front in April 1935 in order to contain Germany, a key step towards

military globalisation Military globalization is defined by David Held as "the process which embodies the growing extensity and intensity of military relations among the political units of the world-system. Understood as such, it reflects both the expanding network of wo ...

; however, that June, the United Kingdom made an

independent naval agreement with Germany, easing prior restrictions. The Soviet Union, concerned by

Germany's goals of capturing vast areas of Eastern Europe, drafted a treaty of mutual assistance with France. Before taking effect, though, the

Franco-Soviet pact

The Franco-Soviet Treaty of Mutual Assistance was a bilateral treaty between France and the Soviet Union with the aim of enveloping Nazi Germany in 1935 to reduce the threat from Central Europe. It was pursued by Maxim Litvinov, the Soviet foreig ...

was required to go through the bureaucracy of the League of Nations, which rendered it essentially toothless. The United States, concerned with events in Europe and Asia, passed the

Neutrality Act in August of the same year.

Hitler defied the Versailles and

Locarno treaties by

remilitarising the Rhineland in March 1936, encountering little opposition due to the policy of

appeasement. In October 1936, Germany and Italy formed the

Rome–Berlin Axis

The Axis powers, ; it, Potenze dell'Asse ; ja, 枢軸国 ''Sūjikukoku'', group=nb originally called the Rome–Berlin Axis, was a military coalition that initiated World War II and fought against the Allies. Its principal members were ...

. A month later, Germany and Japan signed the

Anti-Comintern Pact

The Anti-Comintern Pact, officially the Agreement against the Communist International was an anti-Communist pact concluded between Nazi Germany and the Empire of Japan on 25 November 1936 and was directed against the Communist International (C ...

, which Italy joined the following year.

Asia

The

Kuomintang

The Kuomintang (KMT), also referred to as the Guomindang (GMD), the Nationalist Party of China (NPC) or the Chinese Nationalist Party (CNP), is a major political party in the Republic of China, initially on the Chinese mainland and in Tai ...

(KMT) party in China launched a

unification campaign against

regional warlords and nominally unified China in the mid-1920s, but was soon embroiled in

a civil war against its former

Chinese Communist Party

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP), officially the Communist Party of China (CPC), is the founding and sole ruling party of the People's Republic of China (PRC). Under the leadership of Mao Zedong, the CCP emerged victorious in the Chinese Civil ...

allies and

new regional warlords. In 1931, an

increasingly militaristic Empire of Japan

The also known as the Japanese Empire or Imperial Japan, was a historical nation-state and great power that existed from the Meiji Restoration in 1868 until the enactment of the post-World War II Constitution of Japan, 1947 constitu ...

, which had long sought influence in China as the first step of what its government saw as the country's

right to rule Asia, staged the

Mukden Incident as a pretext to

invade Manchuria and establish the

puppet state

A puppet state, puppet régime, puppet government or dummy government, is a state that is ''de jure'' independent but ''de facto'' completely dependent upon an outside power and subject to its orders.Compare: Puppet states have nominal sove ...

of

Manchukuo.

China appealed to the

League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference that ...

to stop the Japanese invasion of Manchuria. Japan withdrew from the League of Nations after being

condemned

Condemned or The Condemned may refer to:

Legal

* Persons awaiting execution

* A condemned property, or condemned building, by a local authority, usually for public health or safety reasons

* A condemned property seized by power of eminent domain

...

for its incursion into Manchuria. The two nations then fought several battles, in

Shanghai

Shanghai (; , , Standard Mandarin pronunciation: ) is one of the four direct-administered municipalities of the People's Republic of China (PRC). The city is located on the southern estuary of the Yangtze River, with the Huangpu River flowin ...

,

Rehe and

Hebei

Hebei or , (; alternately Hopeh) is a northern province of China. Hebei is China's sixth most populous province, with over 75 million people. Shijiazhuang is the capital city. The province is 96% Han Chinese, 3% Manchu, 0.8% Hui, and 0 ...

, until the

Tanggu Truce

The Tanggu Truce, sometimes called the , was a ceasefire that was signed between the Republic of China and the Empire of Japan in Tanggu District, Tianjin, on May 31, 1933. It formally ended the Japanese invasion of Manchuria, which had begun ...

was signed in 1933. Thereafter, Chinese volunteer forces continued the resistance to Japanese aggression in

Manchuria

Manchuria is an exonym (derived from the endo demonym " Manchu") for a historical and geographic region in Northeast Asia encompassing the entirety of present-day Northeast China (Inner Manchuria) and parts of the Russian Far East (Outer M ...

, and

Chahar and Suiyuan. After the 1936

Xi'an Incident

The Xi'an Incident, previously romanized as the Sian Incident, was a political crisis that took place in Xi'an, Shaanxi in 1936. Chiang Kai-shek, leader of the Nationalist government of China, was detained by his subordinate generals Chang ...

, the Kuomintang and communist forces agreed on a ceasefire to present

a united front to oppose Japan.

Pre-war events

Italian invasion of Ethiopia (1935)

The

Second Italo-Ethiopian War

The Second Italo-Ethiopian War, also referred to as the Second Italo-Abyssinian War, was a war of aggression which was fought between Italy and Ethiopia from October 1935 to February 1937. In Ethiopia it is often referred to simply as the Itali ...

was a brief

colonial war

Colonial war (in some contexts referred to as small war) is a blanket term relating to the various conflicts that arose as the result of overseas territories being settled by foreign powers creating a colony. The term especially refers to wars ...

that began in October 1935 and ended in May 1936. The war began with the invasion of the

Ethiopian Empire

The Ethiopian Empire (), also formerly known by the exonym Abyssinia, or just simply known as Ethiopia (; Amharic and Tigrinya: ኢትዮጵያ , , Oromo: Itoophiyaa, Somali: Itoobiya, Afar: ''Itiyoophiyaa''), was an empire that histori ...

(also known as

Abyssinia

The Ethiopian Empire (), also formerly known by the exonym Abyssinia, or just simply known as Ethiopia (; Amharic and Tigrinya: ኢትዮጵያ , , Oromo: Itoophiyaa, Somali: Itoobiya, Afar: ''Itiyoophiyaa''), was an empire that historica ...

) by the armed forces of the

Kingdom of Italy

The Kingdom of Italy ( it, Regno d'Italia) was a state that existed from 1861, when Victor Emmanuel II of Sardinia was proclaimed King of Italy, until 1946, when civil discontent led to an institutional referendum to abandon the monarchy and f ...

(''Regno d'Italia''), which was launched from

Italian Somaliland

Italian Somalia ( it, Somalia Italiana; ar, الصومال الإيطالي, Al-Sumal Al-Italiy; so, Dhulka Talyaaniga ee Soomaalida), was a protectorate and later colony of the Kingdom of Italy in present-day Somalia. Ruled in the 19th centu ...

and

Eritrea. The war resulted in the

military occupation

Military occupation, also known as belligerent occupation or simply occupation, is the effective military control by a ruling power over a territory that is outside of that power's sovereign territory.Eyāl Benveniśtî. The international law ...

of Ethiopia and its

annexation into the newly created colony of

Italian East Africa

Italian East Africa ( it, Africa Orientale Italiana, AOI) was an Italian colony in the Horn of Africa. It was formed in 1936 through the merger of Italian Somalia, Italian Eritrea, and the newly occupied Ethiopian Empire, conquered in the S ...

(''Africa Orientale Italiana'', or AOI); in addition it exposed the weakness of the

League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference that ...

as a force to preserve peace. Both Italy and Ethiopia were member nations,

but the League did little when the former clearly violated Article X of the League's

Covenant

Covenant may refer to:

Religion

* Covenant (religion), a formal alliance or agreement made by God with a religious community or with humanity in general

** Covenant (biblical), in the Hebrew Bible

** Covenant in Mormonism, a sacred agreement b ...

. The United Kingdom and France supported imposing sanctions on Italy for the invasion, but the sanctions were not fully enforced and failed to end the Italian invasion. Italy subsequently dropped its objections to Germany's goal of absorbing

Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populous ...

.

Spanish Civil War (1936–1939)

When civil war broke out in Spain, Hitler and Mussolini lent military support to the

Nationalist rebels, led by General

Francisco Franco. Italy supported the Nationalists to a greater extent than the Nazis did: altogether Mussolini sent to Spain more than 70,000 ground troops and 6,000 aviation personnel, as well as about 720 aircraft. The Soviet Union supported the existing government of the

Spanish Republic

The Spanish Republic (), commonly known as the Second Spanish Republic (), was the form of government in Spain from 1931 to 1939. The Republic was proclaimed on 14 April 1931, after the deposition of King Alfonso XIII, and was dissolved on 1 A ...

. More than 30,000 foreign volunteers, known as the

International Brigades, also fought against the Nationalists. Both Germany and the Soviet Union used this

proxy war

A proxy war is an armed conflict between two states or non-state actors, one or both of which act at the instigation or on behalf of other parties that are not directly involved in the hostilities. In order for a conflict to be considered a pr ...

as an opportunity to test in combat their most advanced weapons and tactics. The Nationalists won the civil war in April 1939; Franco, now dictator, remained officially neutral during World WarII but

generally favoured the Axis. His greatest collaboration with Germany was the sending of

volunteers

Volunteering is a voluntary act of an individual or group freely giving time and labor for community service. Many volunteers are specifically trained in the areas they work, such as medicine, education, or emergency rescue. Others serve ...

to fight on the

Eastern Front.

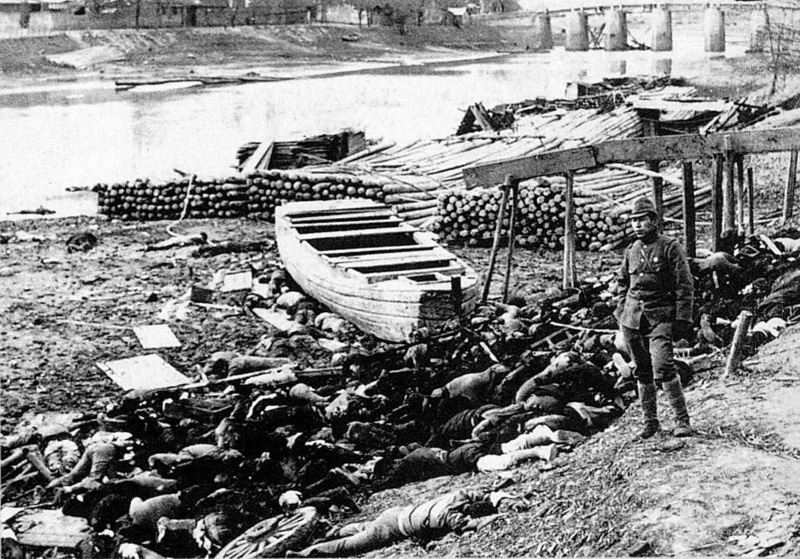

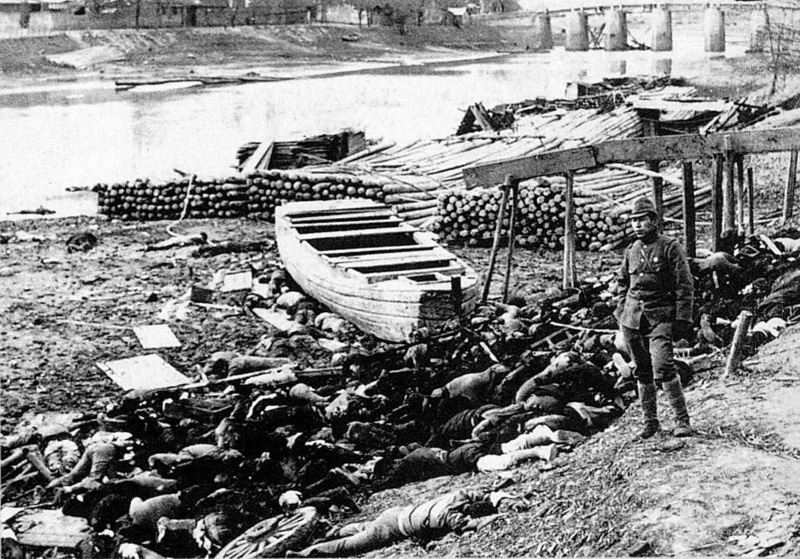

Japanese invasion of China (1937)

In July 1937, Japan captured the former Chinese imperial capital of

Peking

}

Beijing ( ; ; ), alternatively romanized as Peking ( ), is the capital of the People's Republic of China. It is the center of power and development of the country. Beijing is the world's most populous national capital city, with over 21 ...

after instigating the

Marco Polo Bridge Incident, which culminated in the Japanese campaign to invade all of China. The Soviets quickly signed a

non-aggression pact with China to lend

materiel

Materiel (; ) refers to supplies, equipment, and weapons in military supply-chain management, and typically supplies and equipment in a commercial supply chain context.

In a military context, the term ''materiel'' refers either to the specif ...

support, effectively ending China's prior

co-operation with Germany. From September to November, the Japanese attacked

Taiyuan, engaged the

Kuomintang Army around Xinkou,

[.] and fought

Communist forces in Pingxingguan.

[Yang Kuisong, "On the reconstruction of the facts of the Battle of Pingxingguan"] Generalissimo

''Generalissimo'' ( ) is a military rank of the highest degree, superior to field marshal and other five-star ranks in the states where they are used.

Usage

The word (), an Italian term, is the absolute superlative of ('general') thus me ...

Chiang Kai-shek deployed his

best army to

defend Shanghai, but after three months of fighting, Shanghai fell. The Japanese continued to push the Chinese forces back,

capturing the capital Nanking in December 1937. After the fall of Nanking, tens or hundreds of thousands of Chinese civilians and disarmed combatants were

murdered by the Japanese.

[Totten, Samuel. ''Dictionary of Genocide''. 2008, 298–99.]

In March 1938, Nationalist Chinese forces won their

first major victory at Taierzhuang, but then the city of

Xuzhou

Xuzhou (徐州), also known as Pengcheng (彭城) in ancient times, is a major city in northwestern Jiangsu province, China. The city, with a recorded population of 9,083,790 at the 2020 census (3,135,660 of which lived in the built-up area ma ...

was taken by the Japanese in May. In June 1938, Chinese forces stalled the Japanese advance by

flooding the Yellow River; this manoeuvre bought time for the Chinese to prepare their defences at

Wuhan

Wuhan (, ; ; ) is the capital of Hubei Province in the People's Republic of China. It is the largest city in Hubei and the most populous city in Central China, with a population of over eleven million, the ninth-most populous Chinese city an ...

, but the

city was taken by October. Japanese military victories did not bring about the collapse of Chinese resistance that Japan had hoped to achieve; instead, the Chinese government relocated inland to

Chongqing and continued the war.

Soviet–Japanese border conflicts

In the mid-to-late 1930s, Japanese forces in

Manchukuo had sporadic border clashes with the Soviet Union and

Mongolia

Mongolia; Mongolian script: , , ; lit. "Mongol Nation" or "State of Mongolia" () is a landlocked country in East Asia, bordered by Russia to the north and China to the south. It covers an area of , with a population of just 3.3 million, ...

. The Japanese doctrine of

Hokushin-ron

was a pre-World War II political doctrine of the Empire of Japan which stated that Manchuria and Siberia were Japan's sphere of interest and that the potential value to Japan for economic and territorial expansion in those areas was greater tha ...

, which emphasised Japan's expansion northward, was favoured by the Imperial Army during this time. With the Japanese defeat at

Khalkin Gol in 1939, the ongoing Second Sino-Japanese War and ally Nazi Germany pursuing neutrality with the Soviets, this policy would prove difficult to maintain. Japan and the Soviet Union eventually signed a

Neutrality Pact in April 1941, and Japan adopted the doctrine of

Nanshin-ron

was a political doctrine in the Empire of Japan that stated that Southeast Asia and the Pacific Islands were Japan's sphere of interest and that their potential value to the Empire for economic and territorial expansion was greater than elsewh ...

, promoted by the Navy, which took its focus southward, eventually leading to its war with the United States and the Western Allies.

European occupations and agreements

In Europe, Germany and Italy were becoming more aggressive. In March 1938, Germany

annexed Austria, again provoking

little response from other European powers. Encouraged, Hitler began pressing German claims on the

Sudetenland, an area of

Czechoslovakia

, rue, Чеськословеньско, , yi, טשעכאסלאוואקיי,

, common_name = Czechoslovakia

, life_span = 1918–19391945–1992

, p1 = Austria-Hungary

, image_p1 ...

with a predominantly

ethnic German

, native_name_lang = de

, region1 =

, pop1 = 72,650,269

, region2 =

, pop2 = 534,000

, region3 =

, pop3 = 157,000

3,322,405

, region4 =

, pop4 = ...

population. Soon the United Kingdom and France followed the appeasement policy of British Prime Minister

Neville Chamberlain and conceded this territory to Germany in the

Munich Agreement

The Munich Agreement ( cs, Mnichovská dohoda; sk, Mníchovská dohoda; german: Münchner Abkommen) was an agreement concluded at Munich on 30 September 1938, by Germany, the United Kingdom, France, and Italy. It provided "cession to Germany ...

, which was made against the wishes of the Czechoslovak government, in exchange for a promise of no further territorial demands. Soon afterwards, Germany and Italy forced Czechoslovakia to

cede additional territory to Hungary, and Poland annexed Czechoslovakia's

Zaolzie

Trans-Olza ( pl, Zaolzie, ; cs, Záolží, ''Záolší''; german: Olsa-Gebiet; Cieszyn Silesian: ''Zaolzi''), also known as Trans-Olza Silesia ( Polish: ''Śląsk Zaolziański''), is a territory in the Czech Republic, which was disputed betwe ...

region.

Although all of Germany's stated demands had been satisfied by the agreement, privately Hitler was furious that British interference had prevented him from seizing all of Czechoslovakia in one operation. In subsequent speeches Hitler attacked British and Jewish "war-mongers" and in January 1939

secretly ordered a major build-up of the German navy to challenge British naval supremacy. In March 1939,

Germany invaded the remainder of Czechoslovakia and subsequently split it into the German

Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia

The Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia; cs, Protektorát Čechy a Morava; its territory was called by the Nazis ("the rest of Czechia"). was a partially annexed territory of Nazi Germany established on 16 March 1939 following the German oc ...

and a pro-German

client state

A client state, in international relations, is a state that is economically, politically, and/or militarily subordinate to another more powerful state (called the "controlling state"). A client state may variously be described as satellite state, ...

, the

Slovak Republic. Hitler also delivered an

ultimatum to Lithuania on 20 March 1939, forcing the concession of the

Klaipėda Region

The Klaipėda Region ( lt, Klaipėdos kraštas) or Memel Territory (german: Memelland or ''Memelgebiet'') was defined by the 1919 Treaty of Versailles in 1920 and refers to the northernmost part of the German province of East Prussia, when as ...

, formerly the German ''Memelland''.

Greatly alarmed and with Hitler making further demands on the

Free City of Danzig, the United Kingdom and France

guaranteed their support for Polish independence; when

Italy conquered Albania in April 1939, the same guarantee was extended to the

Kingdoms of Romania and

Greece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders ...

. Shortly after the

Franco

Franco may refer to:

Name

* Franco (name)

* Francisco Franco (1892–1975), Spanish general and dictator of Spain from 1939 to 1975

* Franco Luambo (1938–1989), Congolese musician, the "Grand Maître"

Prefix

* Franco, a prefix used when ref ...

-

British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English, ...

pledge to Poland, Germany and Italy formalised their own alliance with the

Pact of Steel

The Pact of Steel (german: Stahlpakt, it, Patto d'Acciaio), formally known as the Pact of Friendship and Alliance between Germany and Italy, was a military and political alliance between Italy and Germany.

The pact was initially drafted as a t ...

. Hitler accused the United Kingdom and Poland of trying to "encircle" Germany and renounced the

Anglo-German Naval Agreement

The Anglo-German Naval Agreement (AGNA) of 18 June 1935 was a naval agreement between the United Kingdom and Germany regulating the size of the '' Kriegsmarine'' in relation to the Royal Navy.

The Anglo-German Naval Agreement fixed a ratio whe ...

and the

German–Polish Non-Aggression Pact.

The situation reached a general crisis in late August as German troops continued to mobilise against the Polish border. On 23 August, when tripartite negotiations about a military alliance between France, the United Kingdom and Soviet Union stalled, the Soviet Union signed

a non-aggression pact with Germany. This pact had a secret protocol that defined German and Soviet "spheres of influence" (western

Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populou ...

and Lithuania for Germany;

eastern Poland

Eastern Poland is a macroregion in Poland comprising the Lublin, Podkarpackie, Podlaskie, Świętokrzyskie, and Warmian-Masurian voivodeships.

The make-up of the distinct macroregion is based not only of geographical criteria, but also econo ...

, Finland,

Estonia

Estonia, formally the Republic of Estonia, is a country by the Baltic Sea in Northern Europe. It is bordered to the north by the Gulf of Finland across from Finland, to the west by the sea across from Sweden, to the south by Latvia, a ...

,

Latvia and

Bessarabia for the Soviet Union), and raised the question of continuing Polish independence. The pact neutralised the possibility of Soviet opposition to a campaign against Poland and assured that Germany would not have to face the prospect of a two-front war, as it had in World WarI. Immediately after that, Hitler ordered the attack to proceed on 26 August, but upon hearing that the United Kingdom had concluded a formal mutual assistance pact with Poland and that Italy would maintain neutrality, he decided to delay it.

In response to British requests for direct negotiations to avoid war, Germany made demands on Poland, which only served as a pretext to worsen relations.

On 29 August, Hitler demanded that a Polish

plenipotentiary

A ''plenipotentiary'' (from the Latin ''plenus'' "full" and ''potens'' "powerful") is a diplomat who has full powers—authorization to sign a treaty or convention on behalf of his or her sovereign. When used as a noun more generally, the wor ...

immediately travel to Berlin to negotiate the handover of

Danzig, and to allow a

plebiscite

A referendum (plural: referendums or less commonly referenda) is a direct vote by the electorate on a proposal, law, or political issue. This is in contrast to an issue being voted on by a representative. This may result in the adoption of ...

in the

Polish Corridor

The Polish Corridor (german: Polnischer Korridor; pl, Pomorze, Polski Korytarz), also known as the Danzig Corridor, Corridor to the Sea or Gdańsk Corridor, was a territory located in the region of Pomerelia (Pomeranian Voivodeship, easter ...

in which the German minority would vote on secession.

The Poles refused to comply with the German demands, and on the night of 30–31 August in a confrontational meeting with the British ambassador

Nevile Henderson

Sir Nevile Meyrick Henderson (10 June 1882 – 30 December 1942) was a British diplomat who served as the ambassador of the United Kingdom to Germany from 1937 to 1939.

Early life and education

Henderson was born at Sedgwick Park, near Horsha ...

, Ribbentrop declared that Germany considered its claims rejected.

Course of the war

War breaks out in Europe (1939–40)

On 1 September 1939, Germany

invaded Poland after

having staged several

false flag border incidents as a pretext to initiate the invasion. The first German attack of the war came against the

Polish defenses at Westerplatte.

The United Kingdom responded with an ultimatum to Germany to cease military operations, and on 3 September, after the ultimatum was ignored, Britain and France declared war on Germany, followed by

Australia,

New Zealand

New Zealand ( mi, Aotearoa ) is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and over 700 smaller islands. It is the sixth-largest island count ...

,

South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the Southern Africa, southernmost country in Africa. It is bounded to the south by of coastline that stretch along the Atlantic Ocean, South Atlantic and Indian Oceans; to the ...

and

Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by tot ...

. During the

Phoney War

The Phoney War (french: Drôle de guerre; german: Sitzkrieg) was an eight-month period at the start of World War II, during which there was only one limited military land operation on the Western Front, when French troops invaded Germa ...

period, the alliance provided no direct military support to Poland, outside of a

cautious French probe into the Saarland.

[.]

, observes that, while it is true that Poland was far away, making it difficult for the French and British to provide support, " w Western historians of World War II ... know that the British had committed to bomb Germany if it attacked Poland, but did not do so except for one raid on the base of Wilhelmshaven. The French, who committed to attacking Germany in the west, had no intention of doing so." The Western Allies also began a

naval blockade of Germany, which aimed to damage the country's economy and the war effort. Germany responded by ordering

U-boat warfare against Allied merchant and warships, which would later escalate into the

Battle of the Atlantic.

On 8 September, German troops reached the suburbs of

Warsaw

Warsaw ( pl, Warszawa, ), officially the Capital City of Warsaw,, abbreviation: ''m.st. Warszawa'' is the capital and largest city of Poland. The metropolis stands on the River Vistula in east-central Poland, and its population is officia ...

. The Polish

counter offensive to the west halted the German advance for several days, but it was outflanked and encircled by the ''

Wehrmacht

The ''Wehrmacht'' (, ) were the unified armed forces of Nazi Germany from 1935 to 1945. It consisted of the ''Heer'' (army), the '' Kriegsmarine'' (navy) and the ''Luftwaffe'' (air force). The designation "''Wehrmacht''" replaced the previo ...

''. Remnants of the Polish army broke through to

besieged Warsaw. On 17 September 1939, two days after signing a

cease-fire with Japan, the

Soviet Union invaded Poland under the pretext that the Polish state had ostensibly ceased to exist. On 27 September, the Warsaw garrison surrendered to the Germans, and

the last large operational unit of the Polish Army surrendered on 6October. Despite the military defeat, Poland never surrendered; instead, it formed the

Polish government-in-exile

The Polish government-in-exile, officially known as the Government of the Republic of Poland in exile ( pl, Rząd Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej na uchodźstwie), was the government in exile of Poland formed in the aftermath of the Invasion of Pola ...

and a

clandestine state apparatus remained in occupied Poland. A significant part of Polish military personnel

evacuated to Romania and Latvia; many of them later

fought against the Axis in other theatres of the war.

Germany annexed the western and

occupied the central part of Poland, and the Soviet Union

annexed its eastern part; small shares of Polish territory were transferred to

Lithuania and

Slovakia

Slovakia (; sk, Slovensko ), officially the Slovak Republic ( sk, Slovenská republika, links=no ), is a landlocked country in Central Europe. It is bordered by Poland to the north, Ukraine to the east, Hungary to the south, Austria to the s ...

. On 6 October, Hitler made a public peace overture to the United Kingdom and France but said that the future of Poland was to be determined exclusively by Germany and the Soviet Union. The proposal was rejected,

and Hitler ordered an immediate offensive against France, which was postponed until the spring of 1940 due to bad weather.

After the outbreak of war in Poland, Stalin threatened

Estonia

Estonia, formally the Republic of Estonia, is a country by the Baltic Sea in Northern Europe. It is bordered to the north by the Gulf of Finland across from Finland, to the west by the sea across from Sweden, to the south by Latvia, a ...

,

Latvia and

Lithuania with military invasion, forcing the three

Baltic countries

The Baltic states, et, Balti riigid or the Baltic countries is a geopolitical term, which currently is used to group three countries: Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania. All three countries are members of NATO, the European Union, the Eurozone ...

to sign

pacts that stipulated the creation of Soviet military bases in these countries. In October 1939, significant Soviet military contingents were moved there.

Finland

Finland ( fi, Suomi ; sv, Finland ), officially the Republic of Finland (; ), is a Nordic country in Northern Europe. It shares land borders with Sweden to the northwest, Norway to the north, and Russia to the east, with the Gulf of B ...

refused to sign a similar pact and rejected ceding part of its territory to the Soviet Union.

The Soviet Union invaded Finland in November 1939, and the Soviet Union was expelled from the

League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference that ...

. Despite overwhelming numerical superiority, Soviet military success during the

Winter War

The Winter War,, sv, Vinterkriget, rus, Зи́мняя война́, r=Zimnyaya voyna. The names Soviet–Finnish War 1939–1940 (russian: link=no, Сове́тско-финская война́ 1939–1940) and Soviet–Finland War 1 ...

was modest, and the Finno-Soviet war ended in March 1940 with

some Finnish concessions of territory.

In June 1940, the Soviet Union

occupied

' (Norwegian: ') is a Norwegian political thriller TV series that premiered on TV2 on 5 October 2015. Based on an original idea by Jo Nesbø, the series is co-created with Karianne Lund and Erik Skjoldbjærg. Season 2 premiered on 10 October ...

the entire territories of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania, and the Romanian regions of

Bessarabia, Northern Bukovina and the Hertsa region. In August 1940, Hitler imposed the

Second Vienna Award

The Second Vienna Award, also known as the Vienna Diktat, was the second of two territorial disputes that were arbitrated by Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy. On 30 August 1940, they assigned the territory of Northern Transylvania, including all o ...

on Romania which led to the transfer of

Northern Transylvania to Hungary. In September 1940, Bulgaria demanded

Southern Dobruja

Southern Dobruja, South Dobruja or Quadrilateral ( Bulgarian: Южна Добруджа, ''Yuzhna Dobrudzha'' or simply Добруджа, ''Dobrudzha''; ro, Dobrogea de Sud, or ) is an area of northeastern Bulgaria comprising Dobrich and Silis ...

from Romania with German and Italian support, leading to the

Treaty of Craiova

The Treaty of Craiova ( bg, Крайовска спогодба, Krayovska spogodba; ro, Tratatul de la Craiova) was signed on 7 September 1940 and ratified on 13 September 1940 by the Kingdom of Bulgaria and the Kingdom of Romania. Under its te ...

.

The loss of one-third of Romania's 1939 territory caused a coup against King Carol II, turning Romania into a fascist dictatorship under Marshal Ion Antonescu with a course set firmly towards the Axis in the hopes of a German guarantee. Meanwhile, Nazi-Soviet political rapprochement and economic co-operation gradually stalled, and both states began preparations for war.

Western Europe (1940–41)

In April 1940,

Germany invaded Denmark and Norway to protect shipments of

iron ore from Sweden, which the Allies were

attempting to cut off. Denmark capitulated after a few hours, and Norway was conquered within two months

despite Allied support.

British discontent over the Norwegian campaign led to the resignation of Prime Minister

Neville Chamberlain, who was replaced by

Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 during the Second World War, and again from ...

on 10May 1940.

On the same day, Germany

launched an offensive against France. To circumvent the strong

Maginot Line fortifications on the Franco-German border, Germany directed its attack at the neutral nations of

Belgium

Belgium, ; french: Belgique ; german: Belgien officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. The country is bordered by the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Luxembourg to the southeast, France to th ...

,

the Netherlands

)

, anthem = ( en, "William of Nassau")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of the Netherlands

, established_title = Before independence

, established_date = Spanish Netherl ...

, and

Luxembourg

Luxembourg ( ; lb, Lëtzebuerg ; french: link=no, Luxembourg; german: link=no, Luxemburg), officially the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg, ; french: link=no, Grand-Duché de Luxembourg ; german: link=no, Großherzogtum Luxemburg is a small lan ...

. The Germans carried out a flanking manoeuvre through the

Ardennes region, which was mistakenly perceived by Allies as an impenetrable natural barrier against armoured vehicles. By successfully implementing new ''

Blitzkrieg'' tactics, the ''Wehrmacht'' rapidly advanced to the Channel and cut off the Allied forces in Belgium, trapping the bulk of the Allied armies in a cauldron on the Franco-Belgian border near Lille. The United Kingdom was able

to evacuate a significant number of Allied troops from the continent by early June, although abandoning almost all their equipment.

On 10 June,

Italy invaded France, declaring war on both France and the United Kingdom. The Germans turned south against the weakened French army, and

Paris

Paris () is the Capital city, capital and List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), ma ...

fell to them on 14June. Eight days later

France signed an armistice with Germany; it was divided into

German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

** Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ge ...

and

Italian occupation zones, and an unoccupied

rump state

A rump state is the remnant of a once much larger state, left with a reduced territory in the wake of secession, annexation, occupation, decolonization, or a successful coup d'état or revolution on part of its former territory. In the last case ...

under the

Vichy Regime

Vichy France (french: Régime de Vichy; 10 July 1940 – 9 August 1944), officially the French State ('), was the fascist French state headed by Marshal Philippe Pétain during World War II. Officially independent, but with half of its ter ...

, which, though officially neutral, was generally aligned with Germany. France kept its fleet, which

the United Kingdom attacked on 3July in an attempt to prevent its seizure by Germany.

The air

Battle of Britain

The Battle of Britain, also known as the Air Battle for England (german: die Luftschlacht um England), was a military campaign of the Second World War, in which the Royal Air Force (RAF) and the Fleet Air Arm (FAA) of the Royal Navy defende ...

began in early July with

Luftwaffe attacks on shipping and harbours.

The United Kingdom rejected Hitler's peace offer,

and the

German air superiority campaign started in August but failed to defeat

RAF Fighter Command

RAF Fighter Command was one of the commands of the Royal Air Force. It was formed in 1936 to allow more specialised control of fighter aircraft. It served throughout the Second World War. It earned near-immortal fame during the Battle of Brita ...

, forcing the indefinite postponement of the

proposed German invasion of Britain. The German

strategic bombing

Strategic bombing is a military strategy used in total war with the goal of defeating the enemy by destroying its morale, its economic ability to produce and transport materiel to the theatres of military operations, or both. It is a systematica ...

offensive intensified with night attacks on London and other cities in

the Blitz

The Blitz was a German bombing campaign against the United Kingdom in 1940 and 1941, during the Second World War. The term was first used by the British press and originated from the term , the German word meaning 'lightning war'.

The Germa ...

, but failed to significantly disrupt the British war effort and largely ended in May 1941.

Using newly captured French ports, the German Navy

enjoyed success against an over-extended

Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against ...

, using

U-boat

U-boats were naval submarines operated by Germany, particularly in the First and Second World Wars. Although at times they were efficient fleet weapons against enemy naval warships, they were most effectively used in an economic warfare ro ...

s against British shipping

in the Atlantic. The British

Home Fleet scored a significant victory on 27May 1941 by

sinking the German battleship ''Bismarck''.

In November 1939, the United States was taking measures to assist China and the Western Allies and amended the

Neutrality Act to allow

"cash and carry" purchases by the Allies. In 1940, following the German capture of Paris, the size of the

United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage ...

was

significantly increased. In September the United States further agreed to a

trade of American destroyers for British bases. Still, a large majority of the American public continued to oppose any direct military intervention in the conflict well into 1941. In December 1940 Roosevelt accused Hitler of planning world conquest and ruled out any negotiations as useless, calling for the United States to become an "

arsenal of democracy

"Arsenal of Democracy" was the central phrase used by U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt in a radio broadcast on the threat to national security, delivered on December 29, 1940—nearly a year before the United States entered the Second Worl ...

" and promoting

Lend-Lease programmes of aid to support the British war effort. The United States started strategic planning to prepare for a full-scale offensive against Germany.

At the end of September 1940, the

Tripartite Pact

The Tripartite Pact, also known as the Berlin Pact, was an agreement between Germany, Italy, and Japan signed in Berlin on 27 September 1940 by, respectively, Joachim von Ribbentrop, Galeazzo Ciano and Saburō Kurusu. It was a defensive milit ...

formally united Japan, Italy, and Germany as the

Axis powers

The Axis powers, ; it, Potenze dell'Asse ; ja, 枢軸国 ''Sūjikukoku'', group=nb originally called the Rome–Berlin Axis, was a military coalition that initiated World War II and fought against the Allies. Its principal members were ...

. The Tripartite Pact stipulated that any country, with the exception of the Soviet Union, which attacked any Axis Power would be forced to go to war against all three. The Axis expanded in November 1940 when

Hungary

Hungary ( hu, Magyarország ) is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning of the Pannonian Basin, Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the ...

,

Slovakia

Slovakia (; sk, Slovensko ), officially the Slovak Republic ( sk, Slovenská republika, links=no ), is a landlocked country in Central Europe. It is bordered by Poland to the north, Ukraine to the east, Hungary to the south, Austria to the s ...

and

Romania

Romania ( ; ro, România ) is a country located at the crossroads of Central, Eastern, and Southeastern Europe. It borders Bulgaria to the south, Ukraine to the north, Hungary to the west, Serbia to the southwest, Moldova to the east, and ...

joined.

Romania

Romania ( ; ro, România ) is a country located at the crossroads of Central, Eastern, and Southeastern Europe. It borders Bulgaria to the south, Ukraine to the north, Hungary to the west, Serbia to the southwest, Moldova to the east, and ...

and

Hungary

Hungary ( hu, Magyarország ) is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning of the Pannonian Basin, Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the ...

later made major contributions to the Axis war against the Soviet Union, in Romania's case partially to recapture

territory ceded to the Soviet Union.

Mediterranean (1940–41)

In early June 1940, the Italian ''Regia Aeronautica''

attacked and besieged Malta, a British possession. From late summer to early autumn, Italy

conquered British Somaliland and made an

incursion into British-held Egypt. In October,

Italy attacked Greece, but the attack was repulsed with heavy Italian casualties; the campaign ended within months with minor territorial changes. Germany started preparation for an invasion of the Balkans to assist Italy, to prevent the British from gaining a foothold there, which would be a potential threat for Romanian oil fields, and to strike against the British dominance of the Mediterranean.

In December 1940, British Empire forces began

counter-offensives against Italian forces in Egypt and

Italian East Africa