ŇĆyama Sutematsu on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Princess , born , was a prominent figure in the

The 600 women and children inside the castle, led by

The 600 women and children inside the castle, led by

In December 1871, when she was eleven years old, Yamakawa was sent to the United States for study, as part of the

In December 1871, when she was eleven years old, Yamakawa was sent to the United States for study, as part of the  By October, however, they had separated: Yoshimasu and Ueda returned to Japan, Tsuda moved in with the Lanmans, and on October 31, 1872 Nagai and Yamakawa were moved to

By October, however, they had separated: Yoshimasu and Ueda returned to Japan, Tsuda moved in with the Lanmans, and on October 31, 1872 Nagai and Yamakawa were moved to

While at school, Yamakawa began styling her name as Stematz Yamakawa, using the American name order and a spelling which matched the pronunciation of her name. Her teachers included

While at school, Yamakawa began styling her name as Stematz Yamakawa, using the American name order and a spelling which matched the pronunciation of her name. Her teachers included

In January 1882, Yamakawa wrote to Alice Bacon that one of the marriage proposals she had declined was from someone "I might have married for money and position but I resisted the temptation," whom she later revealed to have been

In January 1882, Yamakawa wrote to Alice Bacon that one of the marriage proposals she had declined was from someone "I might have married for money and position but I resisted the temptation," whom she later revealed to have been  ŇĆyama Iwao left Japan to study Prussian military systems early in 1884, relieving ŇĆyama Sutematsu of the social duties of a minister's wife for the year he was away. In July 1884, the Peerage Act of 1884 made them

ŇĆyama Iwao left Japan to study Prussian military systems early in 1884, relieving ŇĆyama Sutematsu of the social duties of a minister's wife for the year he was away. In July 1884, the Peerage Act of 1884 made them

After her marriage, ŇĆyama took on the social responsibilities of a government official's wife, and advised the Empress on western customs, holding the official title of "Advisor on Westernization in the Court." She also advocated for women's education and encouraged upper-class Japanese women to volunteer as nurses. She frequently hosted American visitors to advance Japanese-American relations, including Alice Bacon, the geographer

After her marriage, ŇĆyama took on the social responsibilities of a government official's wife, and advised the Empress on western customs, holding the official title of "Advisor on Westernization in the Court." She also advocated for women's education and encouraged upper-class Japanese women to volunteer as nurses. She frequently hosted American visitors to advance Japanese-American relations, including Alice Bacon, the geographer

File:Sutematsu Oyama at Vassar.jpg, Yamakawa Sutematsu at Vassar

File:Vassar College Class of 1882.jpg, The Vassar College Class of 1882. Yamakawa Sutematsu is in the third-to-last row, fifth from the left.

File:Princess Sutematsu Oyama.jpg, Marchioness ŇĆyama, c. 1888

File:Sutematsu Yamakawa formal.jpg, ŇĆyama Sutematsu in formal court

Oyama Sutematsu

in Vassar's special collections.

Photo gallery

collected by Janice P. Nimura. {{DEFAULTSORT:Oyama, Sutematsu 1860 births 1919 deaths Deaths from Spanish flu Japanese women Members of the Iwakura Mission People from Aizu People of Meiji-period Japan Vassar College alumni

Meiji era

The is an era of Japanese history that extended from October 23, 1868 to July 30, 1912.

The Meiji era was the first half of the Empire of Japan, when the Japanese people moved from being an isolated feudal society at risk of colonization b ...

, and the first Japanese woman to receive a college degree. She was born into a traditional samurai

were the hereditary military nobility and officer caste of medieval and early-modern Japan from the late 12th century until their abolition in 1876. They were the well-paid retainers of the '' daimyo'' (the great feudal landholders). They h ...

household which supported the Tokugawa shogunate

The Tokugawa shogunate (, Japanese Śĺ≥Ś∑ĚŚĻēŚļú ''Tokugawa bakufu''), also known as the , was the military government of Japan during the Edo period from 1603 to 1868. Nussbaum, Louis-Fr√©d√©ric. (2005)"''Tokugawa-jidai''"in ''Japan Encyclopedia ...

during the Boshin War

The , sometimes known as the Japanese Revolution or Japanese Civil War, was a civil war in Japan fought from 1868 to 1869 between forces of the ruling Tokugawa shogunate and a clique seeking to seize political power in the name of the Imperi ...

. As a child, she survived the monthlong siege known as the Battle of Aizu

The Battle of Aizu (Japanese: šľöśī•śą¶šļČ, "War of Aizu") was fought in northern Japan from October to November in autumn 1868, and was part of the Boshin War.

History

Aizu was known for its martial skill, and maintained at any given time a s ...

in 1868, and lived briefly as a refugee.

In 1871, Yamakawa was one of five girls chosen to accompany the Iwakura Mission

The Iwakura Mission or Iwakura Embassy (, ''Iwakura Shisetsudan'') was a Japanese diplomatic voyage to the United States and Europe conducted between 1871 and 1873 by leading statesmen and scholars of the Meiji period. It was not the only such m ...

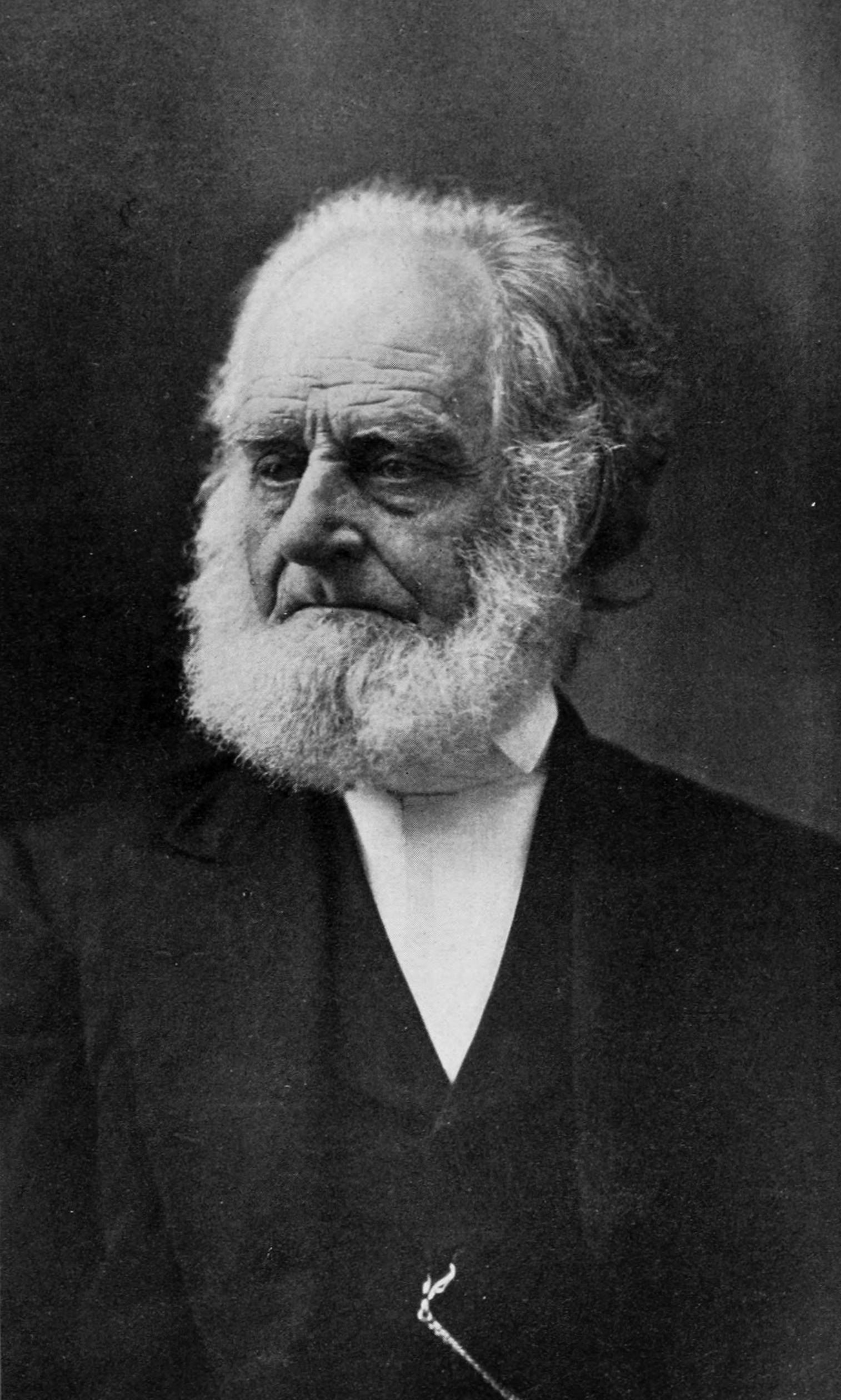

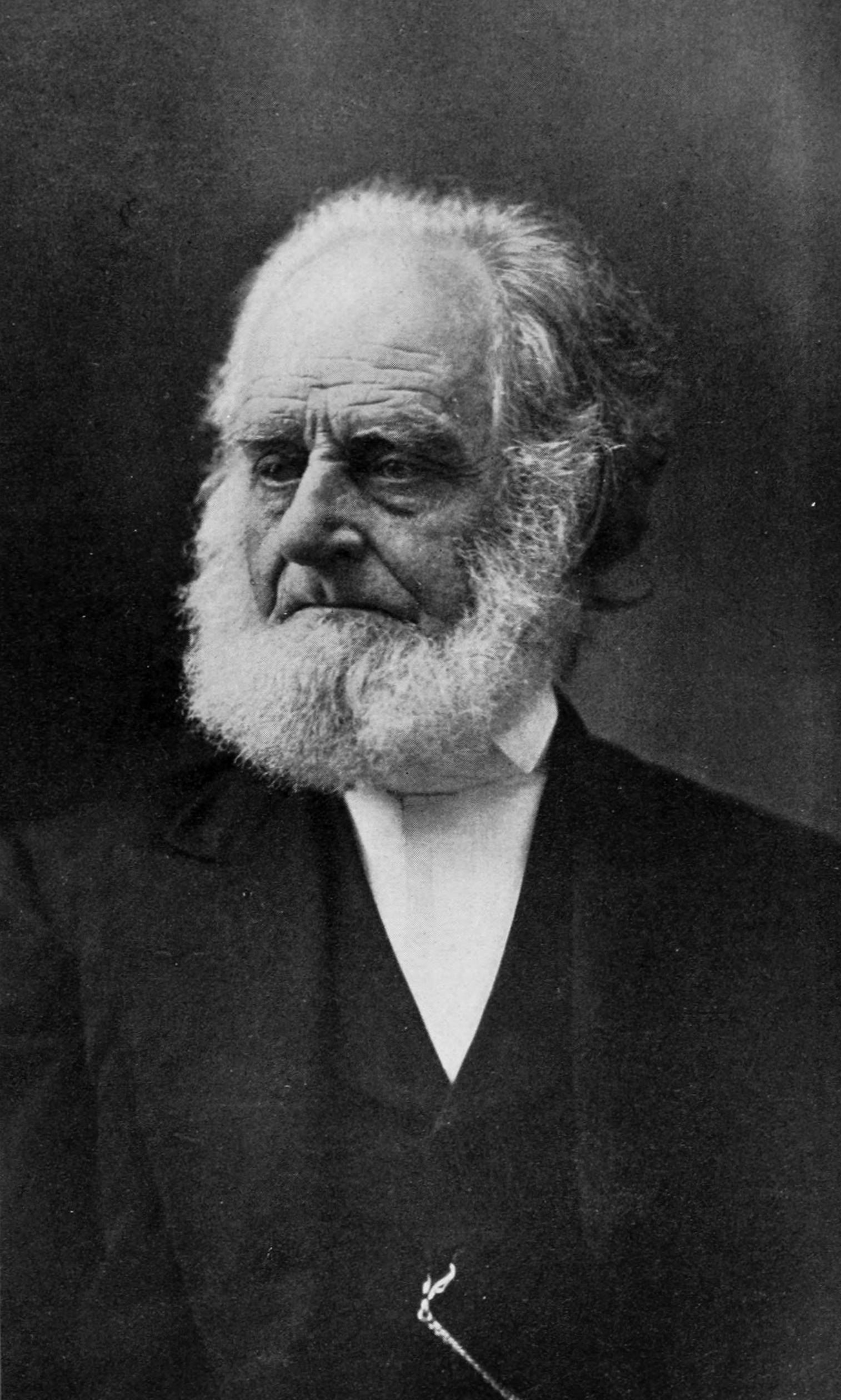

to America and spend ten years receiving an American education. At this time, her name was changed to , or, when she wrote in English, Stematz Yamakawa. Yamakawa lived in the household of Leonard Bacon

Reverend Leonard Bacon (February 19, 1802 ‚Äď December 24, 1881) was an American Congregational preacher and writer. He held the pulpit of the First Church New Haven and was later professor of church history and polity at Yale College.

Biograp ...

in New Haven, Connecticut

New Haven is a city in the U.S. state of Connecticut. It is located on New Haven Harbor on the northern shore of Long Island Sound in New Haven County, Connecticut and is part of the New York City metropolitan area. With a population of 134,02 ...

, becoming particularly close with his youngest daughter Alice Mabel Bacon

Alice Mabel Bacon (February 26, 1858 – May 1, 1918) was an American writer, women's educator and a foreign advisor to the Japanese government in Meiji period Japan.

Early life

Alice Mabel Bacon was the youngest of the three daughters and ...

. She learned English and graduated from Hillhouse High School

James Hillhouse High School is a four-year comprehensive public high school in New Haven, Connecticut. It serves grades 9‚Äď12.

James Hillhouse High School is the oldest public high school in New Haven, and is part of the New Haven Public Scho ...

, then attended Vassar College

Vassar College ( ) is a private liberal arts college in Poughkeepsie, New York, United States. Founded in 1861 by Matthew Vassar, it was the second degree-granting institution of higher education for women in the United States, closely follo ...

, the first nonwhite student at that fledgling women's university. She graduated with the Vassar College class of 1882, earning a B.A., magna cum laude. After graduation, she remained a few more months to study nursing, and finally returned to Japan in October 1882.

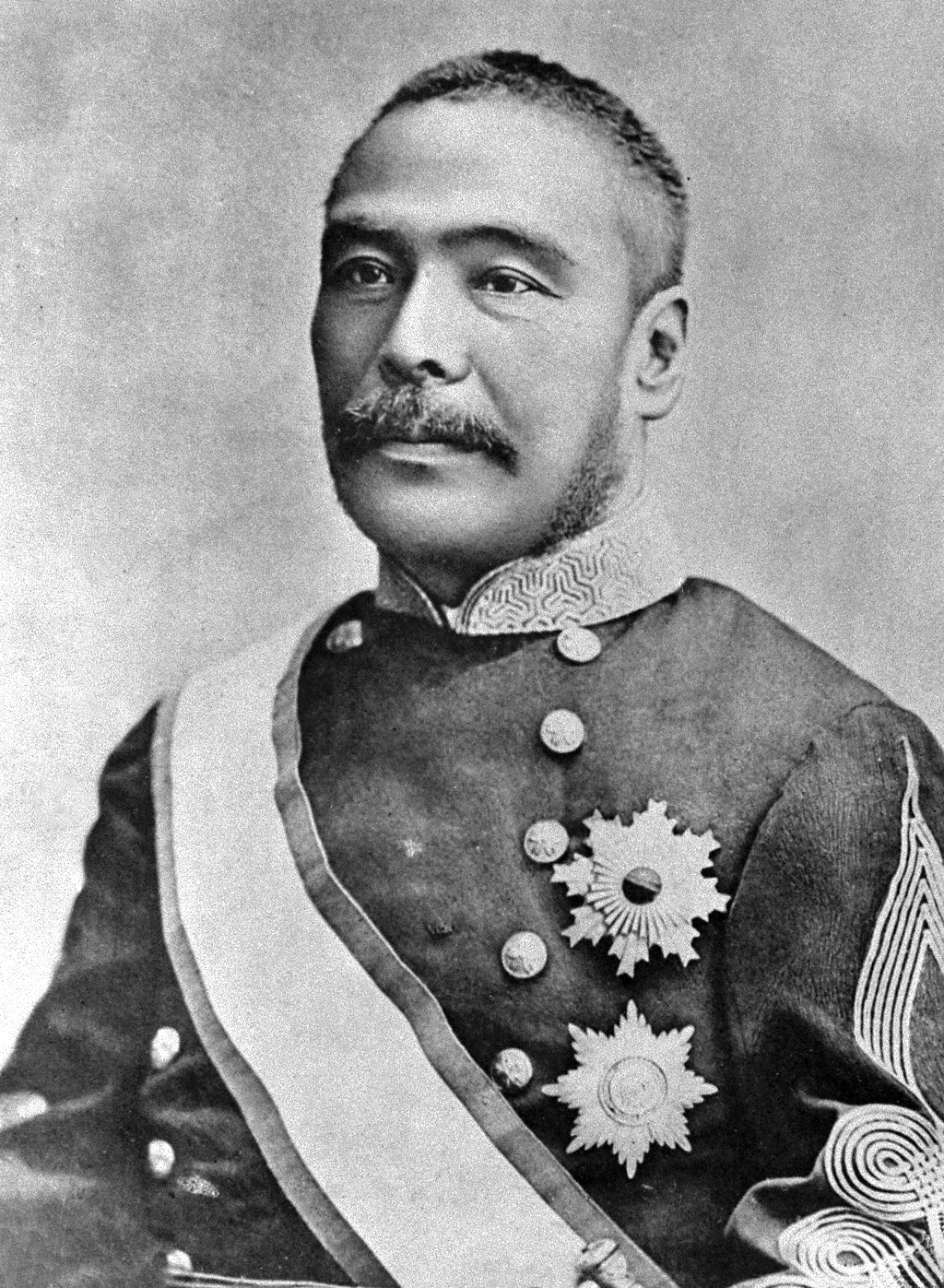

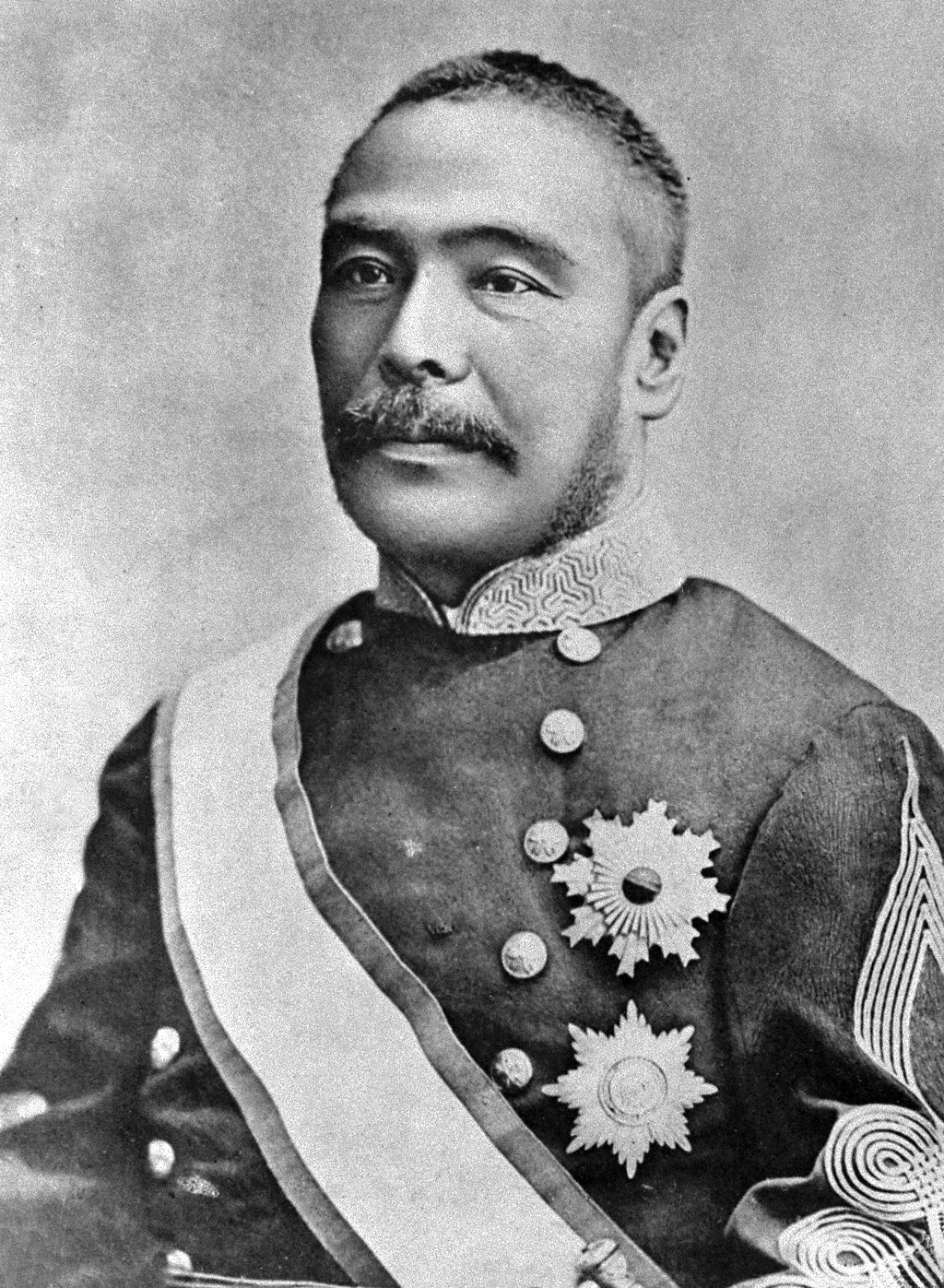

When she first returned to Japan, Yamakawa looked for educational or government work, but her options were limited, especially because she could not read or write Japanese. In April 1882, she accepted a marriage proposal from ŇĆyama Iwao

was a Japanese field marshal, and one of the founders of the Imperial Japanese Army.

Biography

Early life

ŇĆyama was born in Kagoshima to a ''samurai'' family of the Satsuma Domain. as a younger paternal cousin to Saigo Takamori. A prot√© ...

, a wealthy and important general, despite the fact that he had fought on the opposing side of the Battle of Aizu. As her husband was promoted, she was elevated in rank to become Countess, Marchioness, and finally Princess ŇĆyama in 1905. She was a prominent figure in Rokumeikan

The was a large two-story building in Tokyo, completed in 1883, which became a controversial symbol of Westernisation in the Meiji period. Commissioned for the housing of foreign guests by the Foreign Minister Inoue Kaoru, it was designed by Brit ...

society, advising the Empress on Western customs. She also used her social position as a philanthropist to advocate for women's education and volunteer nursing. She assisted in the founding of the Peeresses' School for high-ranking ladies, and the Women's Home School of English, which would later become Tsuda University

is a private women's university based at Kodaira, Tokyo. It is one of the oldest and most prestigious higher educational institutions for women in Japan, contributing to the advancement of women in society for more than a century.

History

The u ...

. She died in 1919 when the 1918 flu pandemic

The 1918‚Äď1920 influenza pandemic, commonly known by the misnomer Spanish flu or as the Great Influenza epidemic, was an exceptionally deadly global influenza pandemic caused by the H1N1 influenza A virus. The earliest documented case was ...

reached Tokyo.

Early life

Yamakawa Sakiko was born on February 24, 1860, inAizu

is the westernmost of the three regions of Fukushima Prefecture, Japan, the other two regions being NakadŇćri in the central area of the prefecture and HamadŇćri in the east. As of October 1, 2010, it had a population of 291,838. The princip ...

, an isolated and mountainous region in what is now the Fukushima Prefecture

Fukushima Prefecture (; ja, Á¶ŹŚ≥∂ÁúĆ, Fukushima-ken, ) is a prefecture of Japan located in the TŇćhoku region of Honshu. Fukushima Prefecture has a population of 1,810,286 () and has a geographic area of . Fukushima Prefecture borders Miya ...

. She was the youngest daughter of , a ''karŇć

were top-ranking samurai officials and advisors in service to the ''daimyŇćs'' of feudal Japan.

Overview

In the Edo period, the policy of ''sankin-kŇćtai'' (alternate attendance) required each ''daimyŇć'' to place a ''karŇć'' in Edo and anoth ...

'' (senior retainer) of the lord of Aizu, and his wife TŇći of another ''karŇć'' family, the . Yamakawa had five siblings: three sisters‚ÄĒ, Misao, and Tokiwa; and two brothers, and .

Yamakawa was raised in a traditional samurai household in the town of Wakamatsu, in a several-acre compound near the northern gate of Tsuruga Castle

, also known as Tsuruga Castle (ť∂ī„É∂Śüé ''Tsuru-ga-jŇć'') is a concrete replica of a traditional Japanese castle in northern Japan, at the center of the city of Aizuwakamatsu, in Fukushima Prefecture.

Background

Aizu Wakamatsu Castle is locate ...

. She did not attend school, but was taught to read and write at home, as part of a rigorous education in etiquette and obedience based on the eighteenth-century neo-Confucian

Neo-Confucianism (, often shortened to ''l«źxu√©'' ÁźÜŚ≠ł, literally "School of Principle") is a moral, ethical, and metaphysical Chinese philosophy influenced by Confucianism, and originated with Han Yu (768‚Äď824) and Li Ao (772‚Äď841) in th ...

text ''Onna Daigaku

The ''Onna Daigaku'' ( or "The Great Learning for Women") is an 18th-century Japanese educational text advocating for neo-Confucian values in education, with the oldest existing version dating to 1729. It is frequently attributed to Japanese botan ...

'' (''Greater Learning for Women'').

Battle of Aizu

In 1868‚Äď1869, Yamakawa's family was on the losing side of theBoshin War

The , sometimes known as the Japanese Revolution or Japanese Civil War, was a civil war in Japan fought from 1868 to 1869 between forces of the ruling Tokugawa shogunate and a clique seeking to seize political power in the name of the Imperi ...

. The Boshin War was a civil war at the end of Japan's ''bakumatsu

was the final years of the Edo period when the Tokugawa shogunate ended. Between 1853 and 1867, Japan ended its isolationist foreign policy known as and changed from a feudal Tokugawa shogunate to the modern empire of the Meiji government ...

'' ("end of military government"), in which pro-shogunate

, officially , was the title of the military dictators of Japan during most of the period spanning from 1185 to 1868. Nominally appointed by the Emperor, shoguns were usually the de facto rulers of the country, though during part of the Kamakur ...

forces resisted the new imperial rule that began with the 1867 Meiji Restoration

The , referred to at the time as the , and also known as the Meiji Renovation, Revolution, Regeneration, Reform, or Renewal, was a political event that restored practical imperial rule to Japan in 1868 under Emperor Meiji. Although there were ...

. The conflict reached Yamakawa's hometown with the Battle of Aizu

The Battle of Aizu (Japanese: šľöśī•śą¶šļČ, "War of Aizu") was fought in northern Japan from October to November in autumn 1868, and was part of the Boshin War.

History

Aizu was known for its martial skill, and maintained at any given time a s ...

in late 1868. On October 8, 1868, when Yamakawa was eight, imperial forces invaded and burned her hometown of Wakamatsu. Yamakawa took shelter within the walls of Tsuruga Castle with her mother and sisters. Several hundred people from other samurai families instead committed ritual suicide, in what would become a famous instance of mass suicide. This invasion marked the beginning of a monthlong siege, which came to be a symbol of "heroic and desperate resistance." It was during the Battle of Aizu that the Byakkotai

The was a group of around 305 young teenage samurai of the Aizu Domain, who fought in the Boshin War (1868‚Äď1869) on the side of the Tokugawa shogunate.

History

The Byakkotai was part of Aizu's four-unit military, formed in April 1868 in the ...

(White Tiger Brigade), a group of teenage fighters, famously committed mass suicide under the mistaken belief that the castle had fallen.

The 600 women and children inside the castle, led by

The 600 women and children inside the castle, led by Matsudaira Teru

Matsudaira Teru (śĚĺŚĻ≥ ÁÖß), or Teruhime (, "Princess Teru"), (February 2, 1833 ‚ąí February 28, 1884) was an aristocrat in Japan during the late Edo period, Edo and early Meiji periods. She participated in the siege of Aizuwakamatsu Castle (Ts ...

, formed workgroups to cook, clean, and make gun cartridges, as well as nursing nearly 1,500 wounded soldiers. One of Yamakawa's sisters attempted to join Nakano Takeko

was a Japanese female warrior of the Aizu Domain, who fought and died during the Boshin War. During the Battle of Aizu, she fought with a naginata (a Japanese polearm) and was the leader of an ad hoc corps of female combatants who fought in ...

's , but on her mother's orders remained inside the castle making gun cartridges. Yamakawa herself, age eight, carried supplies for the cartridge makers. Toward the end of the siege, Yamakawa's mother sent her and other girls to fly kites as a gesture of defiance while imperial cannons bombarded the castle and the women smothered the shells with wet quilts. One shell which was not smothered in time exploded near her, wounding Yamakawa's neck with shrapnel, and killing her sister-in-law Toseko.

After the battle

The siege ended with the castle's surrender on November 7, 1868. Yamakawa was taken to a nearby prisoner camp with her mother and sisters, where they were held for a year. In the spring of 1870, they were exiled to the newly created Tonami District (an area that is now part of theToyama Prefecture

is a prefecture of Japan located in the ChŇębu region of Honshu. Toyama Prefecture has a population of 1,044,588 (1 June 2019) and has a geographic area of 4,247.61 km2 (1,640.01 sq mi). Toyama Prefecture borders Ishikawa Prefecture to the ...

). The 17,000 refugees exiled there had no experience of farming, and the winter saw shortages of food, shelter, and firewood which threatened Yamakawa's family with starvation. Yamakawa, turning eleven, spread night soil

Night soil is a historically used euphemism for human excreta collected from cesspools, privies, pail closets, pit latrines, privy middens, septic tanks, etc. This material was removed from the immediate area, usually at night, by workers employ ...

on the fields and scavenged for shellfish.

In the spring of 1871, Yamakawa was sent to Hakodate

is a city and port located in Oshima Subprefecture, Hokkaido, Japan. It is the capital city of Oshima Subprefecture. As of July 31, 2011, the city has an estimated population of 279,851 with 143,221 households, and a population density of 412.8 ...

, without her family, where she was lodged with and then with French missionaries.

Education in America

Departure with the Iwakura Mission

In December 1871, when she was eleven years old, Yamakawa was sent to the United States for study, as part of the

In December 1871, when she was eleven years old, Yamakawa was sent to the United States for study, as part of the Iwakura Mission

The Iwakura Mission or Iwakura Embassy (, ''Iwakura Shisetsudan'') was a Japanese diplomatic voyage to the United States and Europe conducted between 1871 and 1873 by leading statesmen and scholars of the Meiji period. It was not the only such m ...

. Yamakawa was one of five girls sent to spend ten years studying Western ways for the benefit of Japan, after which she was to return and pass on her knowledge to other Japanese women and to her children, in accordance with the Meiji philosophy of "Good Wife, Wise Mother

"Good Wife, Wise Mother" is a phrase representing a traditional ideal for womanhood in East Asia, including Japan, China and Korea. First appearing in the late 1800s, the four-character phrase "Good Wife, Wise Mother" (also ) was coined by Nakamu ...

". The other girls were Yoshimasu Ryo (age 14), Ueda Tei (14), Nagai Shige (10) and Tsuda Ume

was a Japanese educator and a pioneer in education for women in Meiji period Japan.Nussbaum, Louis-Frédéric. (2005). "Tsuda Umeko" in . Originally named Tsuda Ume, with ''ume'' referring to the Japanese plum, she went by the name Ume Tsuda ...

(6). All five girls were from samurai families on the losing side of the Boshin War. The initiative was a "pet project" of Kiyotaka Kuroda

Count , also known as , was a Japanese politician of the Meiji era. He was Prime Minister of Japan from 1888 to 1889. He was also vice chairman of the Hokkaido Development Commission ( Kaitaku-shi).

Biography

As a Satsuma ''samurai''

Kur ...

, who initially received no applicants in response to his recruitment efforts, despite the generous funding offered: all the girls' living expenses would be paid for the decade, plus a generous stipend. In response to Kuroda's second call for girls to be educated in America, Yamakawa's eldest brother Hiroshi, acting as head of the household, nominated her. Hiroshi was familiar with Kuroda, since his and Yamakawa's brother Kenjiro had recently left for his own education in America in January 1871, with Kuroda's assistance. Hiroshi may have nominated his sister due to her independent spirit and academic strengths, or out of simple financial need. The five girls chosen were the only applicants.

At this time, Yamakawa's mother changed her given name from ("little blossom") to . The meaning of the new name could indicate disappointment that Yamakawa was being sent away from Japan, with the first character meaning , as if Yamakawa had been thrown away. But the name could also indicate a positive hope: is one of the Three Friends of Winter

The Three Friends of Winter is an art motif that comprises the pine, bamboo, and plum. . The Chinese celebrated the pine, bamboo and plum together, as they observed that these plants do not wither as the cold days deepen into the winter season ...

which flourish even in harsh conditions, and it sounds like , suggesting that her mother her youngest daughter to the government mission while awaiting her safe return.

Before leaving Japan, Yamakawa and the others were the first samurai-class girls to be granted an audience with the Empress Haruko, on November 9, 1871. They departed with the rest of the Iwakura Mission on December 23, 1871 aboard the steamship ''America

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

'', chaperoned by Elida DeLong (wife of the American diplomat Charles E. DeLong

Charles Egbert DeLong (August 13, 1832 ‚Äď October 26, 1876) was an American diplomat who served as the Envoy to Japan during the mid-19th century.Nussbaum, Louis-Fr√©d√©ric. (2005). "De Long, Charles E." in .

Early life

DeLong was a native of ...

), who spoke no Japanese). After a stormy and difficult journey, they arrived in San Francisco on January 15, 1872. Yamakawa and the other girls spent two weeks in San Francisco, largely solitary in their hotel room but the subjects of intense newspaper coverage. Americans typically spelled her name as Stemats Yamagawa, and referred to her and the other girls as "Japanese princesses". After two weeks in San Francisco, the Iwakura Mission embarked on a monthlong cross-country train tour, arriving in Washington, DC on February 29, where Charles Lanman

Charles Lanman (June 14, 1819 - March 4, 1895) was an American author, government official, artist, librarian, and explorer.

Biography

Charles Lanman was born in Monroe, Michigan, on June 14, 1819, the son of Charles James Lanman, and the gr ...

(secretary to Arinori Mori) took custody of the girls. Yamakawa lived briefly with Mrs. Lanman's sister, a Mrs. Hepburn, then in May 1872 all five girls were moved to their own house with a governess, to study English and piano.

By October, however, they had separated: Yoshimasu and Ueda returned to Japan, Tsuda moved in with the Lanmans, and on October 31, 1872 Nagai and Yamakawa were moved to

By October, however, they had separated: Yoshimasu and Ueda returned to Japan, Tsuda moved in with the Lanmans, and on October 31, 1872 Nagai and Yamakawa were moved to New Haven, Connecticut

New Haven is a city in the U.S. state of Connecticut. It is located on New Haven Harbor on the northern shore of Long Island Sound in New Haven County, Connecticut and is part of the New York City metropolitan area. With a population of 134,02 ...

. In New Haven, Yamakawa's elder brother KenjirŇć was studying at Yale University. To ensure that Nagai and Yamakawa practiced their English, they were placed in separate households, Nagai living with the minister John S. C. Abbott and Yamakawa living with the minister Leonard Bacon

Reverend Leonard Bacon (February 19, 1802 ‚Äď December 24, 1881) was an American Congregational preacher and writer. He held the pulpit of the First Church New Haven and was later professor of church history and polity at Yale College.

Biograp ...

. Yamakawa would spend the next ten years as part of the Bacon family, growing particularly close with his youngest daughter of fourteen children, Alice Mabel Bacon

Alice Mabel Bacon (February 26, 1858 – May 1, 1918) was an American writer, women's educator and a foreign advisor to the Japanese government in Meiji period Japan.

Early life

Alice Mabel Bacon was the youngest of the three daughters and ...

. Likely due to the Bacons' influence, Yamakawa converted to Christianity.

Yamakawa attended Grove Hall Seminary, a primary school for girls, with Alice Bacon. In 1875, Yamakawa passed the entrance exam for Hillhouse High School

James Hillhouse High School is a four-year comprehensive public high school in New Haven, Connecticut. It serves grades 9‚Äď12.

James Hillhouse High School is the oldest public high school in New Haven, and is part of the New Haven Public Scho ...

, a prestigious public school, and began her studies there. She attended the 1876 Centennial Exposition

The Centennial International Exhibition of 1876, the first official World's Fair to be held in the United States, was held in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, from May 10 to November 10, 1876, to celebrate the 100th anniversary of the signing of the ...

in Philadelphia with both Nagai and Tsuda, a rare reunion. In April 1877, Yamakawa graduated from Hillhouse High School.

Vassar

Yamakawa began her studies atVassar College

Vassar College ( ) is a private liberal arts college in Poughkeepsie, New York, United States. Founded in 1861 by Matthew Vassar, it was the second degree-granting institution of higher education for women in the United States, closely follo ...

in September 1878, the fourteenth year of the still-new women's college. To her regret, the Bacons couldn't afford to send Alice to college, but she was reunited with Nagai. The two of them were the first nonwhite students at the school, and the first Japanese women to enroll in any college. Nagai enrolled as a special student in the music department, while Yamakawa pursued a full four-year bachelor's degree

A bachelor's degree (from Middle Latin ''baccalaureus'') or baccalaureate (from Modern Latin ''baccalaureatus'') is an undergraduate academic degree awarded by colleges and universities upon completion of a course of study lasting three to six ...

.

While at school, Yamakawa began styling her name as Stematz Yamakawa, using the American name order and a spelling which matched the pronunciation of her name. Her teachers included

While at school, Yamakawa began styling her name as Stematz Yamakawa, using the American name order and a spelling which matched the pronunciation of her name. Her teachers included Henry Van Ingen

Henry Van Ingen (12 November 1833, The Hague - 17 November 1898, Poughkeepsie, New York) was a Dutch painter who for many years taught art at Vassar College in the United States.

Career

Hendrik van Ingen studied at the Hague Academy of Design fr ...

and Maria Mitchell

Maria Mitchell ( /m…ôňąra…™…ô/; August 1, 1818 ‚Äď June 28, 1889) was an American astronomer, librarian, naturalist, and educator. In 1847, she discovered a comet named 1847 VI (modern designation C/1847 T1) that was later known as " Miss Mi ...

. During her time at Vassar, she studied Latin, German, Greek, math, natural history, composition, literature, drawing, chemistry, geology, history, and philosophy. She also mastered chess and whist

Whist is a classic English trick-taking card game which was widely played in the 18th and 19th centuries. Although the rules are simple, there is scope for strategic play.

History

Whist is a descendant of the 16th-century game of ''trump'' ...

. Yamakawa was a reserved and ambitious student, whose marks were among the highest in the class. She was also well-liked by her classmates. Around this time, Yamakawa's sister Misao moved from Japan to Russia; Misao wrote letters in French to Yamakawa, which Yamakawa's classmates translated and helped her reply to. Yamakawa was elected class president for 1879, and invited to join the literary club of the Shakespeare Society, which was "reserved for students of formidable intellect." In 1880, she was a marshal for the college's Founder's Day celebration. In June 1881, Nagai returned to Japan. The ten-year period of the girls' educational mission had ended, but Yamakawa extended her stay to complete her degree. In her senior year, she was named president of the Philalethean Society, the largest social organization at Vassar.

Yamakawa graduated from Vassar College with a B.A., magna cum laude, on June 14, 1882. Her thesis was on "British Foreign Policy Toward Japan," and she was chosen to give a commencement speech on the topic at her class's graduation. After graduation, Yamakawa studied nursing at the Connecticut Training School For Nurses in New Haven in July and August. She and Tsuda (who had also extended her stay, to complete a high school degree) finally departed for Japan in October 1882. They travelled by rail to San Francisco, whence they left aboard the steamship ''Arabic'' on October 31. After a rough three-week journey across the Pacific, Yamakawa arrived in Yokohama

is the second-largest city in Japan by population and the most populous municipality of Japan. It is the capital city and the most populous city in Kanagawa Prefecture, with a 2020 population of 3.8 million. It lies on Tokyo Bay, south of To ...

on November 20, 1882.

Marriage and family

When she first returned to Japan, Yamakawa looked for educational or government work, but her options were limited, especially because she could not read or write Japanese. Yamakawa initially expressed in her letters a resolution to remain unmarried and pursue an intellectual life, turning down at least three proposals. As she struggled to find work, however, she wrote that Japanese culture made marriage necessary, and gave more serious consideration to her suitors. In January 1882, Yamakawa wrote to Alice Bacon that one of the marriage proposals she had declined was from someone "I might have married for money and position but I resisted the temptation," whom she later revealed to have been

In January 1882, Yamakawa wrote to Alice Bacon that one of the marriage proposals she had declined was from someone "I might have married for money and position but I resisted the temptation," whom she later revealed to have been ŇĆyama Iwao

was a Japanese field marshal, and one of the founders of the Imperial Japanese Army.

Biography

Early life

ŇĆyama was born in Kagoshima to a ''samurai'' family of the Satsuma Domain. as a younger paternal cousin to Saigo Takamori. A prot√© ...

. At this time, ŇĆyama was 40 years old, with three young daughters from a first marriage which had just ended with his wife's death in childbirth. He was also a wealthy and important general in the Imperial Japanese Army

The was the official ground-based armed force of the Empire of Japan from 1868 to 1945. It was controlled by the Imperial Japanese Army General Staff Office and the Ministry of the Army, both of which were nominally subordinate to the Emperor o ...

who had lived in Europe for three years, spoke French, and sought an intelligent and cosmopolitan wife. As a former Satsuma Satsuma may refer to:

* Satsuma (fruit), a citrus fruit

* ''Satsuma'' (gastropod), a genus of land snails

Places Japan

* Satsuma, Kagoshima, a Japanese town

* Satsuma District, Kagoshima, a district in Kagoshima Prefecture

* Satsuma Domain, a sou ...

retainer, his military activity included serving as an artilleryman during the bombardment of Yamakawa's hometown of Aizu. He later liked to joke that Yamakawa had made the bullet which struck him during that battle.

In February 1882, Yamakawa played Portia in an amateur production of the final two acts of ''The Merchant of Venice

''The Merchant of Venice'' is a play by William Shakespeare, believed to have been written between 1596 and 1598. A merchant in Venice named Antonio defaults on a large loan provided by a Jewish moneylender, Shylock.

Although classified as ...

'' at a large party, which inspired Iwao to repeat his proposal. This time, he sent a formal request to her brothers, who were shocked. They immediately rejected him on Yamakawa's behalf because, as a Satsuma man, he was an enemy of Yamakawa's Aizu family. After several personal visits from Tsugumichi Saigo

Tsugumichi is a masculine Japanese given name.

Possible writings

Tsugumichi can be written using different combinations of kanji characters. Here are some examples:

*ś¨°ťĀď, "next, way"

*ś¨°Ť∑Į, "next, route"

*ś¨°ťÄö, "next, pass through"

*Śó£ťĀď ...

, a ranking Satsuma leader, Yamakawa's brothers were persuaded to let her decide. In April 1882, Yamakawa decided to accept him. They married in a small ceremony on November 8, 1883. At her marriage, Yamakawa became known as ŇĆyama Sutematsu or Madame ŇĆyama.

ŇĆyama Iwao left Japan to study Prussian military systems early in 1884, relieving ŇĆyama Sutematsu of the social duties of a minister's wife for the year he was away. In July 1884, the Peerage Act of 1884 made them

ŇĆyama Iwao left Japan to study Prussian military systems early in 1884, relieving ŇĆyama Sutematsu of the social duties of a minister's wife for the year he was away. In July 1884, the Peerage Act of 1884 made them Count

Count (feminine: countess) is a historical title of nobility in certain European countries, varying in relative status, generally of middling rank in the hierarchy of nobility. Pine, L. G. ''Titles: How the King Became His Majesty''. New York: ...

and Countess ŇĆyama. ŇĆyama Iwao left Japan again in 1894, at the head of Japan's Second Army, for the First Sino-Japanese War

The First Sino-Japanese War (25 July 1894 ‚Äď 17 April 1895) was a conflict between China and Japan primarily over influence in Korea. After more than six months of unbroken successes by Japanese land and naval forces and the loss of the po ...

. When the war concluded eight months later, the American press credited ŇĆyama Sutematsu's influence for Japan's superiority to China. After the war, ŇĆyama Iwao was promoted, and the couple became Marquess

A marquess (; french: marquis ), es, marqués, pt, marquês. is a nobleman of high hereditary rank in various European peerages and in those of some of their former colonies. The German language equivalent is Markgraf (margrave). A woman wi ...

and Marchioness ŇĆyama. ŇĆyama Iwao served again in the Russo-Japanese War

The Russo-Japanese War ( ja, śó•ťú≤śą¶šļČ, Nichiro sensŇć, Japanese-Russian War; russian: –†—ÉŐĀ—Ā—Ā–ļ–ĺ-—Ź–Ņ√≥–Ĺ—Ā–ļ–į—Ź –≤–ĺ–Ļ–Ĺ√°, R√ļssko-yap√≥nskaya voyn√°) was fought between the Empire of Japan and the Russian Empire during 1904 and 1 ...

beginning in 1904, commanding troops in Manchuria

Manchuria is an exonym (derived from the endo demonym " Manchu") for a historical and geographic region in Northeast Asia encompassing the entirety of present-day Northeast China (Inner Manchuria) and parts of the Russian Far East (Outer Manc ...

. At the end of the war in 1905, his rank was raised again, to Prince

A prince is a male ruler (ranked below a king, grand prince, and grand duke) or a male member of a monarch's or former monarch's family. ''Prince'' is also a title of nobility (often highest), often hereditary, in some European states. Th ...

, and ŇĆyama Sutematsu finally became the "Japanese princess" which the American newspapers had once mistakenly called her, with her title becoming Princess ŇĆyama. In 1915, the ŇĆyamas attended the enthronement

An enthronement is a ceremony of inauguration, involving a person—usually a monarch or religious leader—being formally seated for the first time upon their throne. Enthronements may also feature as part of a larger coronation rite.

...

of Emperor TaishŇć

was the 123rd Emperor of Japan, according to the traditional order of succession, and the second ruler of the Empire of Japan from 30 July 1912 until his death in 1926.

The Emperor's personal name was . According to Japanese custom, while reigni ...

and received a memorial badge as guests to the ceremony of accession.

During the ŇĆyamas' marriage, they had two daughters, Hisako (born November 1884, later Baroness Ida Hisako) and Nagako (born prematurely in 1887, lived only two days), and two sons, Takashi (winter 1886 ‚Äď April 1908) and Kashiwa (born June 1889). ŇĆyama Sutematsu was also a step-mother to ŇĆyama Iwao's three daughters from his first marriage: Nobuko (c. 1876 ‚Äď May 1896) and two younger girls. Despite the fact that ŇĆyama Sutematsu was not motivated by love when she accepted ŇĆyama Iwao's proposal, her biographer Janice P. Nimura calls their marriage "unusually happy," with ŇĆyama Sutematsu as the intellectual equal and helpmeet of her husband.

Depiction in ''The Cuckoo''

Beginning in 1898, a personal tragedy in ŇĆyama's household became the subject of a bestselling novel, in which ŇĆyama was depicted as a wicked stepmother. AuthorKenjirŇć Tokutomi

(December 8, 1868 ‚Äď September 18, 1927) was a Japanese writer and philosopher. He wrote novels under the pseudonym of , and his best-known work was his 1899 novel ''The Cuckoo''.

Biography

Tokutomi was born on December 8, 1868 in Minamat ...

's novel , or ''Nami-ko'', written under the pen name RŇćka Tokutomi, is based on the marriage and death of ŇĆyama Nobuko, one of ŇĆyama Iwao's daughters with his first wife. ŇĆyama Nobuko married Mishima YatarŇć in 1893, a love match which also united two powerful families. The winter after their marriage, Nobuko became ill with tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB) is an infectious disease usually caused by '' Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can also affect other parts of the body. Most infections show no symptoms, in ...

. Mishima's mother insisted that he divorce her, although he felt it was wrong, on the grounds that Nobuko would no longer be healthy enough to bear the heir which was necessary for an only son. While Nobuko was being nursed in the countryside, her parents agreed to a divorce, and the marriage was dissolved in the fall of 1895. Nobuko was moved back to her parents' house in Tokyo, where they built a new wing of their house for her to prevent transmission of the illness. ŇĆyama Sutematsu was the subject of unsympathetic gossip for isolating her stepdaughter, which was seen as a punishing exile. Nobuko died in May 1896, age twenty.

Tokutomi published his story based on these events in the newspaper ''Kokumin shinbun'' from November 1898 to May 1899. Tokutomi revised the story, and published it as a standalone book in 1900, which is when it became one of the most successful novels at the time, a major bestseller popular across many social groups for its elegant language and tear-jerking scenes. The novel is "most often remembered as a novel that protests the victimization of women, particularly the victimization of young brides," blaming the Meiji era

The is an era of Japanese history that extended from October 23, 1868 to July 30, 1912.

The Meiji era was the first half of the Empire of Japan, when the Japanese people moved from being an isolated feudal society at risk of colonization b ...

family system known as ''ie'' for the tragedy. In presenting this moral, the novel depicts the young couple in idealized terms, and is moderately sympathetic toward the character based on ŇĆyama Iwao, but demonizes the characters based on Mishima's mother and on ŇĆyama Sutematsu. ŇĆyama Sutematsu's character is presented as jealous of her own stepdaughter, and a corrupting Western influence in her family.

Promotion of women's education and nursing

After her marriage, ŇĆyama took on the social responsibilities of a government official's wife, and advised the Empress on western customs, holding the official title of "Advisor on Westernization in the Court." She also advocated for women's education and encouraged upper-class Japanese women to volunteer as nurses. She frequently hosted American visitors to advance Japanese-American relations, including Alice Bacon, the geographer

After her marriage, ŇĆyama took on the social responsibilities of a government official's wife, and advised the Empress on western customs, holding the official title of "Advisor on Westernization in the Court." She also advocated for women's education and encouraged upper-class Japanese women to volunteer as nurses. She frequently hosted American visitors to advance Japanese-American relations, including Alice Bacon, the geographer Ellen Churchill Semple

Ellen Churchill Semple (January 8, 1863 ‚Äď May 8, 1932) was an American geographer and the first female president of the Association of American Geographers. She contributed significantly to the early development of the discipline of geography i ...

and the novelist Fannie Caldwell Macaulay. In 1888, ŇĆyama was the subject of negative press from Japanese conservatives, and withdrew somewhat from public life. Positive press in 1895, at the conclusion of the First Sino-Japanese War (in which her husband had military victories and she had philanthropic success), returned her to the public eye.

Education

ŇĆyama assisted Tsuda and Hirobumi Ito in establishing the Peeresses' School in Tokyo for high-ranking ladies, which opened on October 5, 1885. It was overseen by the new minister of education, Arinori Mori, who had frequently met with the girls of the Iwakura Mission while in America. In its first years, the school was a relatively conservative institution, where aristocratic students dressed in formal court dress and studied Japanese, Chinese literature, English or French, and history alongside the less academic subjects of morals, calligraphy, drawing, sewing, tea ceremony, flower arrangement, household management, and formal etiquette. From 1888‚Äď1889, Alice Bacon joined the school as an English teacher. At this point, the school began requiring Western dress for students. In 1900, she was a co-founder with Bacon and Tsuda Ume of the Women's Home School of English (orJoshi Eigaku Juku

is a private women's university based at Kodaira, Tokyo. It is one of the oldest and most prestigious higher educational institutions for women in Japan, contributing to the advancement of women in society for more than a century.

History

The ...

), to teach advanced studies and progressive Western ideals in English. At that time, women's only option for advanced study was the Women's Higher Normal School in Tokyo, which taught in Japanese and provided a more conservative curriculum. While Tsuda and Bacon worked as teachers, ŇĆyama served as a patron

Patronage is the support, encouragement, privilege, or financial aid that an organization or individual bestows on another. In the history of art, arts patronage refers to the support that kings, popes, and the wealthy have provided to artists su ...

of the school.

Philanthropy

ŇĆyama also promoted the idea ofphilanthropy

Philanthropy is a form of altruism that consists of "private initiatives, for the Public good (economics), public good, focusing on quality of life". Philanthropy contrasts with business initiatives, which are private initiatives for private goo ...

(not a typical part of aristocratic Japanese life) to high-ranking Japanese ladies. In 1884, she hosted the first charity bazaar

A charity bazaar, or "fancy faire", was an innovative and controversial fundraising sale in the Victorian era. Hospitals frequently used charity bazaars to raise funds because of their effectiveness. Commercial bazaars grew less popular in the 19t ...

in Japan, raising funds for Tokyo's new Charity Hospital. Despite skepticism of the concept in the Japanese press, and suggestions that the activity was not ladylike, the bazaar was a financial success and became an annual event.

In addition to promoting monetary charity, ŇĆyama was active in volunteer nursing. She was Director of the Ladies Relief Association and the Ladies Volunteer Nursing Association, President of the Ladies Patriotic Association, and Chairman of the Japanese Red Cross Society. At the outbreak of the First Sino-Japanese War in 1894, she formed a committee of sixty aristocratic ladies to raise funds and gather supplies for the troops. ŇĆyama herself rolled bandages for the Red Cross during this war, and worked again as a volunteer nurse during the Russo-Japanese War

The Russo-Japanese War ( ja, śó•ťú≤śą¶šļČ, Nichiro sensŇć, Japanese-Russian War; russian: –†—ÉŐĀ—Ā—Ā–ļ–ĺ-—Ź–Ņ√≥–Ĺ—Ā–ļ–į—Ź –≤–ĺ–Ļ–Ĺ√°, R√ļssko-yap√≥nskaya voyn√°) was fought between the Empire of Japan and the Russian Empire during 1904 and 1 ...

from 1904 to 1905.

Death

At ŇĆyama Iwao's death on December 10, 1916, ŇĆyama Sutematsu made her final retreat from public life, retiring to live in their son Kashiwa's household. She was not involved with the Red Cross duringWorld War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

. When the 1918 flu pandemic

The 1918‚Äď1920 influenza pandemic, commonly known by the misnomer Spanish flu or as the Great Influenza epidemic, was an exceptionally deadly global influenza pandemic caused by the H1N1 influenza A virus. The earliest documented case was ...

reached Tokyo in early 1919, ŇĆyama sent her family to the countryside in Nasushiobara, but remained in Tokyo herself to oversee the Women's Home School of English (Joshi Eigaku Juku) and seek a replacement president after Tsuda's retirement. She fell ill on February 6, and died of related pneumonia on February 18, 1919.

Gallery

kimono

The is a traditional Japanese garment and the national dress of Japan. The kimono is a wrapped-front garment with square sleeves and a rectangular body, and is worn left side wrapped over right, unless the wearer is deceased. The kimono ...

attire of jŇęnihitoe

The , more formally known as the , is a style of formal court dress first worn in the Heian period by noble women and ladies-in-waiting at the Japanese Imperial Court. The was composed of a number of kimono-like robes, layered on top of each oth ...

File:Sutematsu Oyama in evening dress.jpg, ŇĆyama Sutematsu in evening dress

File:Sutematsu Oyama later years.jpg, ŇĆyama Sutematsu in later years

Bibliography

Notes

Citations

General references

* * * * * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

* Kuno is Yamakawa's great granddaughter. *External links

Oyama Sutematsu

in Vassar's special collections.

Photo gallery

collected by Janice P. Nimura. {{DEFAULTSORT:Oyama, Sutematsu 1860 births 1919 deaths Deaths from Spanish flu Japanese women Members of the Iwakura Mission People from Aizu People of Meiji-period Japan Vassar College alumni