Moroccan architecture refers to the

architecture

Architecture is the art and technique of designing and building, as distinguished from the skills associated with construction. It is both the process and the product of sketching, conceiving, planning, designing, and constructing building ...

characteristic of

Morocco

Morocco (),, ) officially the Kingdom of Morocco, is the westernmost country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It overlooks the Mediterranean Sea to the north and the Atlantic Ocean to the west, and has land borders with Algeria to ...

throughout its

history

History (derived ) is the systematic study and the documentation of the human activity. The time period of event before the History of writing#Inventions of writing, invention of writing systems is considered prehistory. "History" is an umbr ...

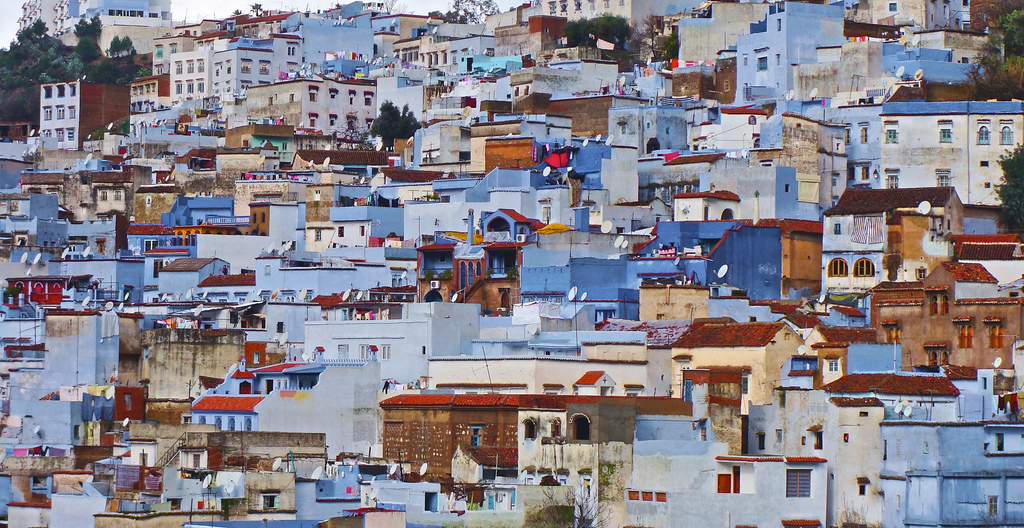

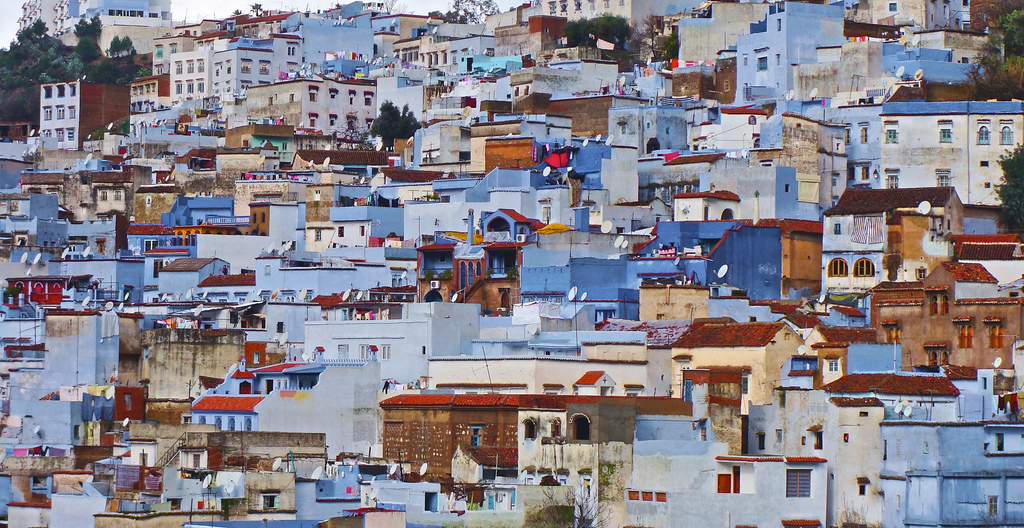

and up to modern times. The country's diverse geography and long history, marked by successive waves of settlers through both migration and military conquest, are all reflected in its architecture. This architectural heritage ranges from

ancient Roman

In modern historiography, ancient Rome refers to Roman civilisation from the founding of the city of Rome in the 8th century BC to the collapse of the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century AD. It encompasses the Roman Kingdom (753–509 BC ...

and

Berber

Berber or Berbers may refer to:

Ethnic group

* Berbers, an ethnic group native to Northern Africa

* Berber languages, a family of Afro-Asiatic languages

Places

* Berber, Sudan, a town on the Nile

People with the surname

* Ady Berber (1913–196 ...

(Amazigh) sites to 20th-century

colonial

Colonial or The Colonial may refer to:

* Colonial, of, relating to, or characteristic of a colony or colony (biology)

Architecture

* American colonial architecture

* French Colonial

* Spanish Colonial architecture

Automobiles

* Colonial (1920 au ...

and

modern architecture

Modern architecture, or modernist architecture, was an architectural movement or architectural style based upon new and innovative technologies of construction, particularly the use of glass, steel, and reinforced concrete; the idea that form ...

.

The most recognizably "Moroccan" architecture, however, is the traditional architecture that developed in the

Islamic period (7th century and after) which dominates much of Morocco's documented history and its existing heritage.

This "

Islamic architecture

Islamic architecture comprises the architectural styles of buildings associated with Islam. It encompasses both secular and religious styles from the early history of Islam to the present day. The Islamic world encompasses a wide geographic ar ...

" of Morocco was part of a wider cultural and artistic complex, often referred to as "

Moorish

The term Moor, derived from the ancient Mauri, is an exonym first used by Christian Europeans to designate the Muslim inhabitants of the Maghreb, the Iberian Peninsula, Sicily and Malta during the Middle Ages.

Moors are not a distinct or se ...

" art, which characterized Morocco,

al-Andalus

Al-Andalus DIN 31635, translit. ; an, al-Andalus; ast, al-Ándalus; eu, al-Andalus; ber, ⴰⵏⴷⴰⵍⵓⵙ, label=Berber languages, Berber, translit=Andalus; ca, al-Àndalus; gl, al-Andalus; oc, Al Andalús; pt, al-Ândalus; es, ...

(Muslim

Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = ''Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, i ...

and

Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic ( pt, República Portuguesa, links=yes ), is a country whose mainland is located on the Iberian Peninsula of Southwestern Europe, and whose territory also includes the Atlantic archipelagos of ...

), and parts of

Algeria

)

, image_map = Algeria (centered orthographic projection).svg

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capital = Algiers

, coordinates =

, largest_city = capital

, relig ...

and even

Tunisia

)

, image_map = Tunisia location (orthographic projection).svg

, map_caption = Location of Tunisia in northern Africa

, image_map2 =

, capital = Tunis

, largest_city = capital

, ...

.

It blended influences from

Berber

Berber or Berbers may refer to:

Ethnic group

* Berbers, an ethnic group native to Northern Africa

* Berber languages, a family of Afro-Asiatic languages

Places

* Berber, Sudan, a town on the Nile

People with the surname

* Ady Berber (1913–196 ...

culture in

North Africa

North Africa, or Northern Africa is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region, and it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of Mauritania in ...

, pre-Islamic Spain (

Roman

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*''Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a letter ...

,

Byzantine

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

, and

Visigothic

The Visigoths (; la, Visigothi, Wisigothi, Vesi, Visi, Wesi, Wisi) were an early Germanic people who, along with the Ostrogoths, constituted the two major political entities of the Goths within the Roman Empire in late antiquity, or what is kno ...

), and contemporary artistic currents in the Islamic

Middle East

The Middle East ( ar, الشرق الأوسط, ISO 233: ) is a geopolitical region commonly encompassing Arabian Peninsula, Arabia (including the Arabian Peninsula and Bahrain), Anatolia, Asia Minor (Asian part of Turkey except Hatay Pro ...

to elaborate a unique style over centuries with recognizable features such as the

"Moorish" arch, ''

riad'' gardens (courtyard gardens with a symmetrical four-part division), and elaborate

geometric

Geometry (; ) is, with arithmetic, one of the oldest branches of mathematics. It is concerned with properties of space such as the distance, shape, size, and relative position of figures. A mathematician who works in the field of geometry is ca ...

and

arabesque

The arabesque is a form of artistic decoration consisting of "surface decorations based on rhythmic linear patterns of scrolling and interlacing foliage, tendrils" or plain lines, often combined with other elements. Another definition is "Foli ...

motifs in wood,

stucco

Stucco or render is a construction material made of aggregates, a binder, and water. Stucco is applied wet and hardens to a very dense solid. It is used as a decorative coating for walls and ceilings, exterior walls, and as a sculptural and a ...

, and

tile

Tiles are usually thin, square or rectangular coverings manufactured from hard-wearing material such as ceramic, stone, metal, baked clay, or even glass. They are generally fixed in place in an array to cover roofs, floors, walls, edges, or o ...

work (notably ''

zellij

''Zellij'' ( ar, الزليج, translit=zillīj; also spelled zillij or zellige) is a style of mosaic tilework made from individually hand-chiseled tile pieces. The pieces were typically of different colours and fitted together to form various pa ...

'').

Although Moroccan Berber architecture is not strictly separate from the rest of Moroccan architecture, many structures and architectural styles are distinctively associated with traditionally Berber or Berber-dominated regions of Morocco such as the

Atlas Mountains

The Atlas Mountains are a mountain range in the Maghreb in North Africa. It separates the Sahara Desert from the Mediterranean Sea and the Atlantic Ocean; the name "Atlantic" is derived from the mountain range. It stretches around through Moroc ...

and the

Sahara

, photo = Sahara real color.jpg

, photo_caption = The Sahara taken by Apollo 17 astronauts, 1972

, map =

, map_image =

, location =

, country =

, country1 =

, ...

and pre-Sahara regions.

These mostly

rural

In general, a rural area or a countryside is a geographic area that is located outside towns and cities. Typical rural areas have a low population density and small settlements. Agricultural areas and areas with forestry typically are describ ...

regions are marked by numerous

kasbah

A kasbah (, also ; ar, قَـصَـبَـة, qaṣaba, lit=fortress, , Maghrebi Arabic: ), also spelled qasba, qasaba, or casbah, is a fortress, most commonly the citadel or fortified quarter of a city. It is also equivalent to the term ''alca ...

s (fortresses) and ''

ksour'' (fortified villages) shaped by local geography and social structures, of which one of the most famous is

Ait Benhaddou

An ait (, like ''eight'') or eyot () is a small island. It is especially used to refer to river islands found on the River Thames and its tributaries in England.

Aits are typically formed by the deposit of sediment in the water, which accumu ...

. They are typically made of

rammed earth

Rammed earth is a technique for constructing foundations, floors, and walls using compacted natural raw materials such as earth, chalk, lime, or gravel. It is an ancient method that has been revived recently as a sustainable building method.

...

and decorated with local geometric motifs. Far from being isolated from other historical artistic currents around them, the Berbers of Morocco (and across North Africa) adapted the forms and ideas of

Islamic architecture

Islamic architecture comprises the architectural styles of buildings associated with Islam. It encompasses both secular and religious styles from the early history of Islam to the present day. The Islamic world encompasses a wide geographic ar ...

to their own conditions and in turn contributed to the formation of

Western Islamic art, particularly during their political domination of the region over the centuries of

Almoravid

The Almoravid dynasty ( ar, المرابطون, translit=Al-Murābiṭūn, lit=those from the ribats) was an imperial Berber Muslim dynasty centered in the territory of present-day Morocco. It established an empire in the 11th century that s ...

,

Almohad

The Almohad Caliphate (; ar, خِلَافَةُ ٱلْمُوَحِّدِينَ or or from ar, ٱلْمُوَحِّدُونَ, translit=al-Muwaḥḥidūn, lit=those who profess the Tawhid, unity of God) was a North African Berbers, Berber M ...

, and

Marinid

The Marinid Sultanate was a Berber Muslim empire from the mid-13th to the 15th century which controlled present-day Morocco and, intermittently, other parts of North Africa (Algeria and Tunisia) and of the southern Iberian Peninsula (Spain) a ...

rule.

Modern architecture in Morocco includes many examples of early 20th-century

Art Deco

Art Deco, short for the French ''Arts Décoratifs'', and sometimes just called Deco, is a style of visual arts, architecture, and product design, that first appeared in France in the 1910s (just before World War I), and flourished in the Unite ...

and local

neo-Moorish

Moorish Revival or Neo-Moorish is one of the exotic revival architectural styles that were adopted by architects of Europe and the Americas in the wake of Romanticist Orientalism. It reached the height of its popularity after the mid-19th centur ...

(or ''Mauresque'') architecture constructed during the

French (and

Spanish

Spanish might refer to:

* Items from or related to Spain:

**Spaniards are a nation and ethnic group indigenous to Spain

**Spanish language, spoken in Spain and many Latin American countries

**Spanish cuisine

Other places

* Spanish, Ontario, Cana ...

) colonial occupation of the country between 1912 and 1956 (or until 1958 for Spain).

In the later 20th century, after Morocco regained its independence, some new buildings continued to pay tribute to traditional Moroccan architecture and motifs (even when designed by foreign architects), as exemplified by the

Mausoleum of King Mohammed V (completed in 1971) and the massive

Hassan II Mosque

The Hassan II Mosque ( ar, مسجد الحسن الثاني, french: Grande Mosquée Hassan II) is a mosque in Casablanca, Morocco. It is the largest functioning mosque in Africa and is the List of largest mosques, 7th largest in the world. Its ...

in

Casablanca

Casablanca, also known in Arabic as Dar al-Bayda ( ar, الدَّار الْبَيْضَاء, al-Dār al-Bayḍāʾ, ; ber, ⴹⴹⴰⵕⵍⴱⵉⴹⴰ, ḍḍaṛlbiḍa, : "White House") is the largest city in Morocco and the country's econom ...

(completed in 1993).

Modernist architecture is also evident in contemporary constructions, not only for regular everyday structures but also in major prestige projects.

History

Antiquity

Although less well-documented, Morocco's earliest historical periods were dominated by

Berber

Berber or Berbers may refer to:

Ethnic group

* Berbers, an ethnic group native to Northern Africa

* Berber languages, a family of Afro-Asiatic languages

Places

* Berber, Sudan, a town on the Nile

People with the surname

* Ady Berber (1913–196 ...

groups and kingdoms, up to the Berber kingdom of

Mauretania

Mauretania (; ) is the Latin name for a region in the ancient Maghreb. It stretched from central present-day Algeria westwards to the Atlantic, covering northern present-day Morocco, and southward to the Atlas Mountains. Its native inhabitants, ...

.

In the 7th or 8th century BC the

Phoenicians

Phoenicia () was an ancient Semitic-speaking peoples, ancient thalassocracy, thalassocratic civilization originating in the Levant region of the eastern Mediterranean, primarily located in modern Lebanon. The territory of the Phoenician city-st ...

founded a colony of

Lixus Lixus may refer to:

* ''lixus'', the Latin word for "boiled"

* Lixus (ancient city) in Morocco

* ''Lixus (beetle)'', a genus of true weevils

* Lixus, one of the sons of Aegyptus and Caliadne

Caliadne (; Ancient Greek: Καλιάδνης ) or Cali ...

on the

Atlantic

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's five oceans, with an area of about . It covers approximately 20% of Earth's surface and about 29% of its water surface area. It is known to separate the " Old World" of Africa, Europe an ...

coast, which later came under

Carthaginian The term Carthaginian ( la, Carthaginiensis ) usually refers to a citizen of Ancient Carthage.

It can also refer to:

* Carthaginian (ship), a three-masted schooner built in 1921

* Insurgent privateers; nineteenth-century South American privateers, ...

, Mauretanian, and eventually

Roman

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*''Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a letter ...

control.

Other important towns such as

Tingis

Tingis (Latin; grc-gre, Τίγγις ''Tíngis'') or Tingi ( Ancient Berber:), the ancient name of Tangier in Morocco, was an important Carthaginian, Moor, and Roman port on the Atlantic Ocean. It was eventually granted the status of a Roman colo ...

(present-day

Tangier

Tangier ( ; ; ar, طنجة, Ṭanja) is a city in northwestern Morocco. It is on the Moroccan coast at the western entrance to the Strait of Gibraltar, where the Mediterranean Sea meets the Atlantic Ocean off Cape Spartel. The town is the cap ...

) and Sala (

Chellah

The Chellah or Shalla ( ber, script=Latn, Sla or ; ar, شالة), is a medieval fortified Muslim necropolis and ancient archeological site in Rabat, Morocco, located on the south (left) side of the Bou Regreg estuary. The earliest evidence of th ...

) were founded and developed by Phoenicians or Mauretanian Berbers.

The settlement of Volubilis was the traditional capital of the Mauretanian kingdom from the second century BC onward, though it may have been founded as early as the third century BC.

Under Mauretanian rule its streets were laid out in a

grid plan

In urban planning, the grid plan, grid street plan, or gridiron plan is a type of city plan in which streets run at right angles to each other, forming a grid.

Two inherent characteristics of the grid plan, frequent intersections and orthogona ...

and may have included a palace complex and fortified walls.

The influence of

Punic

The Punic people, or western Phoenicians, were a Semitic people in the Western Mediterranean who migrated from Tyre, Phoenicia to North Africa during the Early Iron Age. In modern scholarship, the term ''Punic'' – the Latin equivalent of the ...

(Carthaginian) culture in the city is archaeologically attested by Punic

stelae

A stele ( ),Anglicized plural steles ( ); Greek plural stelai ( ), from Greek , ''stēlē''. The Greek plural is written , ''stēlai'', but this is only rarely encountered in English. or occasionally stela (plural ''stelas'' or ''stelæ''), whe ...

and the remains of a Punic temple.

The Mauretanian king

Juba II

Juba II or Juba of Mauretania (Latin: ''Gaius Iulius Iuba''; grc, Ἰóβας, Ἰóβα or ;Roller, Duane W. (2003) ''The World of Juba II and Kleopatra Selene'' "Routledge (UK)". pp. 1–3. . c. 48 BC – AD 23) was the son of Juba I and client ...

(r. 25 BC–23 AD), a

client king

A client state, in international relations, is a state that is economically, politically, and/or militarily subordinate to another more powerful state (called the "controlling state"). A client state may variously be described as satellite state, ...

of Rome and a promoter of late

Hellenistic culture

In Classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Mediterranean history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the emergence of the Roman Empire, as signified by the Battle of Actium in ...

, built a palace in Lixus that was based on Hellenistic models.

Roman settlement and construction was much less extensive in the territory of present-day Morocco, which was on the edge of the empire, than it was in nearby regions like

Hispania

Hispania ( la, Hispānia , ; nearly identically pronounced in Spanish, Portuguese, Catalan, and Italian) was the Roman name for the Iberian Peninsula and its provinces. Under the Roman Republic, Hispania was divided into two provinces: Hispania ...

or

''Africa'' (present-day

Tunisia

)

, image_map = Tunisia location (orthographic projection).svg

, map_caption = Location of Tunisia in northern Africa

, image_map2 =

, capital = Tunis

, largest_city = capital

, ...

). The most significant cities, and the ones most directly influenced by

Roman culture

The culture of ancient Rome existed throughout the almost 1200-year history of the civilization of Ancient Rome. The term refers to the culture of the Roman Republic, later the Roman Empire, which at its peak covered an area from present-day Lo ...

, were Tingis, Volubilis, and Sala.

Large-scale

Roman architecture

Ancient Roman architecture adopted the external language of classical Greek architecture for the purposes of the ancient Romans, but was different from Greek buildings, becoming a new architectural style. The two styles are often considered on ...

was relatively rare; for example, there is only one known

amphitheater

An amphitheatre (British English) or amphitheater (American English; both ) is an open-air venue used for entertainment, performances, and sports. The term derives from the ancient Greek ('), from ('), meaning "on both sides" or "around" and ...

in the region, at Lixus.

Volubilis, the most inland major city, became a well-developed provincial Roman ''

municipium

In ancient Rome, the Latin term (pl. ) referred to a town or city. Etymologically, the was a social contract among ("duty holders"), or citizens of the town. The duties () were a communal obligation assumed by the in exchange for the privi ...

'' and its ruins today are the best-preserved Roman site in Morocco. It included

aqueducts

Aqueduct may refer to:

Structures

*Aqueduct (bridge), a bridge to convey water over an obstacle, such as a ravine or valley

*Navigable aqueduct, or water bridge, a structure to carry navigable waterway canals over other rivers, valleys, railw ...

, a

forum

Forum or The Forum (plural forums or fora) may refer to:

Common uses

* Forum (legal), designated space for public expression in the United States

*Forum (Roman), open public space within a Roman city

**Roman Forum, most famous example

*Internet ...

,

bath complexes

Public baths originated when most people in population centers did not have access to private bathing facilities. Though termed "public", they have often been restricted according to gender, religious affiliation, personal membership, and other cr ...

, a

basilica

In Ancient Roman architecture, a basilica is a large public building with multiple functions, typically built alongside the town's forum. The basilica was in the Latin West equivalent to a stoa in the Greek East. The building gave its name ...

, the

Capitoline Temple

The Capitoline Temple is an ancient monument located in the old city of Volubilis in Fès-Meknès, Morocco. It dates from the Roman era, and was situated in the ancient Kingdom of Mauretania.

The building incorporates a tetrastyle architectural de ...

, and a

triumphal arch

A triumphal arch is a free-standing monumental structure in the shape of an archway with one or more arched passageways, often designed to span a road. In its simplest form a triumphal arch consists of two massive piers connected by an arch, crow ...

dedicated to the emperor

Caracalla

Marcus Aurelius Antoninus (born Lucius Septimius Bassianus, 4 April 188 – 8 April 217), better known by his nickname "Caracalla" () was Roman emperor from 198 to 217. He was a member of the Severan dynasty, the elder son of Emperor S ...

and his mother in 216–217. The site has also preserved a number of fine

Roman mosaics

A Roman mosaic is a mosaic made during the Roman period, throughout the Roman Republic and later Empire. Mosaics were used in a variety of private and public buildings, on both floors and walls, though they competed with cheaper frescos for the ...

.

It continued to be an urban center even after the end of Roman occupation in 285, with evidence of

Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

Christian

Christians () are people who follow or adhere to Christianity, a monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus Christ. The words ''Christ'' and ''Christian'' derive from the Koine Greek title ''Christós'' (Χρι ...

, Berber, and

Byzantine

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

(Eastern Roman) occupation.

Early Islamic period (8th–10th century)

In the early 8th century the region became steadily integrated into the emerging

Muslim world

The terms Muslim world and Islamic world commonly refer to the Islamic community, which is also known as the Ummah. This consists of all those who adhere to the religious beliefs and laws of Islam or to societies in which Islam is practiced. I ...

, beginning with the

military incursions of

Musa ibn Nusayr

Musa ibn Nusayr ( ar, موسى بن نصير ''Mūsá bin Nuṣayr''; 640 – c. 716) served as a Umayyad governor and an Arab general under the Umayyad caliph Al-Walid I. He ruled over the Muslim provinces of North Africa (Ifriqiya), and direct ...

and becoming more definitive with the advent of the

Idrisid dynasty

The Idrisid dynasty or Idrisids ( ar, الأدارسة ') were an Arab Muslim dynasty from 788 to 974, ruling most of present-day Morocco and parts of present-day western Algeria. Named after the founder, Idris I, the Idrisids were an Alid an ...

at the end of that century.

The arrival of Islam was extremely significant as it developed a new set of societal norms (although some of them were familiar to

Judeo-Christian

The term Judeo-Christian is used to group Christianity and Judaism together, either in reference to Christianity's derivation from Judaism, Christianity's borrowing of Jewish Scripture to constitute the "Old Testament" of the Christian Bible, or ...

societies) and institutions which therefore shaped, to some extent, the types of buildings being built and the aesthetic or spiritual values that guided their design.

[Hattstein, Markus and Delius, Peter (eds.), 2011, ''Islam: Art and Architecture''. h.f.ullmann.]

The Idrisids founded the city of

Fes

Fez or Fes (; ar, فاس, fās; zgh, ⴼⵉⵣⴰⵣ, fizaz; french: Fès) is a city in northern inland Morocco and the capital of the Fès-Meknès administrative region. It is the second largest city in Morocco, with a population of 1.11 mi ...

, which became their capital and the major political and cultural center of early Islamic Morocco.

In this early period Morocco also absorbed waves of immigrants from Tunisia and

al-Andalus

Al-Andalus DIN 31635, translit. ; an, al-Andalus; ast, al-Ándalus; eu, al-Andalus; ber, ⴰⵏⴷⴰⵍⵓⵙ, label=Berber languages, Berber, translit=Andalus; ca, al-Àndalus; gl, al-Andalus; oc, Al Andalús; pt, al-Ândalus; es, ...

(Muslim-ruled

Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = ''Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, i ...

and

Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic ( pt, República Portuguesa, links=yes ), is a country whose mainland is located on the Iberian Peninsula of Southwestern Europe, and whose territory also includes the Atlantic archipelagos of ...

), who brought in cultural and artistic influences from their home countries.

The earliest well-known Islamic-era monuments in Morocco, such as the

al-Qarawiyyin

The University of al-Qarawiyyin ( ar, جامعة القرويين; ber, ⵜⴰⵙⴷⴰⵡⵉⵜ ⵏ ⵍⵇⴰⵕⴰⵡⵉⵢⵉⵏ; french: Université Al Quaraouiyine), also written Al-Karaouine or Al Quaraouiyine, is a university located in ...

and

Andalusiyyin mosques in Fes, were built in the

hypostyle

In architecture, a hypostyle () hall has a roof which is supported by columns.

Etymology

The term ''hypostyle'' comes from the ancient Greek ὑπόστυλος ''hypóstȳlos'' meaning "under columns" (where ὑπό ''hypó'' means below or un ...

form and made early use of the

horseshoe or "Moorish" arch.

These reflected early influences from major monuments like the

Great Mosque of Kairouan

The Great Mosque of Kairouan ( ar, جامع القيروان الأكبر), also known as the Mosque of Uqba (), is a mosque situated in the UNESCO World Heritage town of Kairouan, Tunisia and is one of the most impressive and largest Islamic mo ...

and the

Great Mosque of Cordoba

Great may refer to: Descriptions or measurements

* Great, a relative measurement in physical space, see Size

* Greatness, being divine, majestic, superior, majestic, or transcendent

People

* List of people known as "the Great"

*Artel Great (born ...

.

In the 10th century much of northern Morocco came directly within the sphere of influence of the

Umayyad Caliphate of Cordoba, with competition from the

Fatimid Caliphate

The Fatimid Caliphate was an Isma'ilism, Ismaili Shia Islam, Shi'a caliphate extant from the tenth to the twelfth centuries AD. Spanning a large area of North Africa, it ranged from the Atlantic Ocean in the west to the Red Sea in the ea ...

further east.

Early contributions to Moroccan architecture from this period include expansions to the Qarawiyyin and Andalusiyyin mosques and the addition of their square-shafted

minaret

A minaret (; ar, منارة, translit=manāra, or ar, مِئْذَنة, translit=miʾḏana, links=no; tr, minare; fa, گلدسته, translit=goldaste) is a type of tower typically built into or adjacent to mosques. Minarets are generall ...

s, the oldest surviving mosques in Morocco, which anticipate the standard form of later Moroccan minarets.

The Berber Empires: Almoravids and Almohads (11th–13th centuries)

The collapse of the Cordoban caliphate in the early 11th century was followed by the significant

advance of Christian kingdoms into Muslim al-Andalus and the rise of major Berber empires in Morocco. The latter included first the

Almoravids

The Almoravid dynasty ( ar, المرابطون, translit=Al-Murābiṭūn, lit=those from the ribats) was an imperial Berber Muslim dynasty centered in the territory of present-day Morocco. It established an empire in the 11th century that ...

(11th-12th centuries) and then the

Almohads

The Almohad Caliphate (; ar, خِلَافَةُ ٱلْمُوَحِّدِينَ or or from ar, ٱلْمُوَحِّدُونَ, translit=al-Muwaḥḥidūn, lit=those who profess the unity of God) was a North African Berber Muslim empire fo ...

(12th-13th centuries), both of whom also took control of remaining Muslim territory in al-Andalus, creating empires that stretched across large parts of western and northern Africa and into Europe.

This period is considered one of the most formative stages of Moroccan and

Moorish architecture

Moorish architecture is a style within Islamic architecture which developed in the western Islamic world, including al-Andalus (on the Iberian peninsula) and what is now Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia (part of the Maghreb). The term "Moorish" com ...

, establishing many of the forms and motifs that were refined in subsequent centuries.

These two empires were responsible for establishing a new imperial capital at

Marrakesh

Marrakesh or Marrakech ( or ; ar, مراكش, murrākuš, ; ber, ⵎⵕⵕⴰⴽⵛ, translit=mṛṛakc}) is the fourth largest city in the Kingdom of Morocco. It is one of the four Imperial cities of Morocco and is the capital of the Marrakes ...

and the Almohads also began construction of a monumental capital in

Rabat

Rabat (, also , ; ar, الرِّبَاط, er-Ribât; ber, ⵕⵕⴱⴰⵟ, ṛṛbaṭ) is the capital city of Morocco and the country's seventh largest city with an urban population of approximately 580,000 (2014) and a metropolitan populati ...

.

The Almoravids adopted the architectural developments of al-Andalus, such as the complex interlacing arches of the Great Mosque in Cordoba and of the

Aljaferia palace in

Zaragoza

Zaragoza, also known in English as Saragossa,''Encyclopædia Britannica'"Zaragoza (conventional Saragossa)" is the capital city of the Zaragoza Province and of the autonomous community of Aragon, Spain. It lies by the Ebro river and its tributari ...

, while also introducing new ornamental techniques from the east such as ''

muqarnas

Muqarnas ( ar, مقرنص; fa, مقرنس), also known in Iranian architecture as Ahoopāy ( fa, آهوپای) and in Iberian architecture as Mocárabe, is a form of ornamented vaulting in Islamic architecture. It is the archetypal form of I ...

'' ("stalactite" or "honeycomb" carvings).

The Almohad

Kutubiyya and

Tinmal

Tinmel ( Berber: Tin Mel or Tin Mal, ar, تينمل) is a small mountain village in the High Atlas 100 km from Marrakesh, Morocco. Tinmel was the cradle of the Berber Almohad empire, from where the Almohads started their military campaign ...

mosques are often considered the prototypes of later Moroccan mosques.

The monumental minarets (e.g. the Kutubiyya minaret, the

Giralda

The Giralda ( es, La Giralda ) is the bell tower of Seville Cathedral in Seville, Spain. It was built as the minaret for the Great Mosque of Seville in al-Andalus, Moorish Spain, during the reign of the Almohad dynasty, with a Renaissance-style ...

of

Seville

Seville (; es, Sevilla, ) is the capital and largest city of the Spanish autonomous community of Andalusia and the province of Seville. It is situated on the lower reaches of the River Guadalquivir, in the southwest of the Iberian Peninsula ...

, and the

Hassan Tower

Hassan Tower or Tour Hassan ( ar, صومعة حسان; ) is the minaret of an incomplete mosque in Rabat, Morocco. It was commissioned by Abu Yusuf Yaqub al-Mansur, the third Caliph of the Almohad Caliphate, near the end of the 12th century. The ...

of Rabat) and ornamental gateways (e.g.

Bab Agnaou

Bab Agnaou (; ; sometimes transliterated as Bab Agnaw) is one of the best-known gates of Marrakesh, Morocco. Its construction is attributed to the Almohad caliph Abu Yusuf Ya'qub al-Mansur and was completed around 1188 or 1190.

The gate was the ma ...

in Marrakesh, and

Bab Oudaia

Bab Oudaya (also spelled Bab Oudaia or Bab Udaya; ), also known as Bab Lakbir or Bab al-Kabir (), is the monumental gate of the Kasbah of the Udayas in Rabat, Morocco. The gate, built in the late 12th century, is located at the northwest corner ...

and

Bab er-Rouah

Bab er-Rouah (also spelled Bab er-Ruwah or Bab Rouah) is a monumental City gate, gate in the Almohad Caliphate, Almohad-era ramparts of Rabat, Morocco.

History

It was built by the Almohad Caliphate, caliph Abu Yusuf Yaqub al-Mansur, Ya'qub al- ...

in Rabat) of the Almohad period also established the overall decorative schemes that became recurrent in these architectural elements thenceforth. The minaret of the

Kasbah Mosque of Marrakesh was particularly influential and set a style that was repeated, with minor elaborations, in the following Marinid period.

The Almoravids and Almohads also promoted the tradition of establishing garden estates in the countryside of their capital, such as the

Menara Garden

The Menara Gardens ( ar, حدائق المنارة) are a historic public garden and orchard in Marrakech, Morocco. They were established in the 12th century (circa 1157) by the Almohad Caliphate ruler Abd al-Mu'min. Along with the Agdal Gardens ...

and the

Agdal Gardens

The Agdal Gardens (or Aguedal Gardens) are a large area of historic gardens and orchards in Marrakesh, Morocco. The gardens are located to the south of the city's historic Kasbah and its royal palace. Together with the medina of Marrakech and the ...

on the outskirts of Marrakesh. In the late 12th century the Almohads created a new fortified palace district, the

Kasbah of Marrakesh

The Kasbah of Marrakesh is a large walled district in the southern part of the medina of Marrakesh, Morocco, which historically served as the citadel (''kasbah'') and royal palace complex of the city. A large part of the district is still occupied ...

, to serve as their royal residence and administrative center. These traditions and policies had earlier precedents in al-Andalus – such as the creation of

Madinat al-Zahra

Madinat al-Zahra or Medina Azahara ( ar, مدينة الزهراء, translit=Madīnat az-Zahrā, lit=the radiant city) was a fortified palace-city on the western outskirts of Córdoba in present-day Spain. Its remains are a major archaeological ...

near Cordoba – and were subsequently repeated by future rulers of Morocco.

The Marinids (13th–15th centuries)

The Berber

Marinid dynasty

The Marinid Sultanate was a Berber Muslim empire from the mid-13th to the 15th century which controlled present-day Morocco and, intermittently, other parts of North Africa (Algeria and Tunisia) and of the southern Iberian Peninsula (Spain) a ...

that followed was also important in further refining the artistic legacy established by their predecessors. Based in Fes, they built monuments with increasingly intricate and extensive decoration, particularly in wood and

stucco

Stucco or render is a construction material made of aggregates, a binder, and water. Stucco is applied wet and hardens to a very dense solid. It is used as a decorative coating for walls and ceilings, exterior walls, and as a sculptural and a ...

.

They were also the first to deploy extensive use of ''

zellij

''Zellij'' ( ar, الزليج, translit=zillīj; also spelled zillij or zellige) is a style of mosaic tilework made from individually hand-chiseled tile pieces. The pieces were typically of different colours and fitted together to form various pa ...

'' (mosaic tilework in complex

geometric patterns

A pattern is a regularity in the world, in human-made design, or in abstract ideas. As such, the elements of a pattern repeat in a predictable manner. A geometric pattern is a kind of pattern formed of geometric shapes and typically repeated l ...

).

Notably, they were the first to build

madrasa

Madrasa (, also , ; Arabic: مدرسة , pl. , ) is the Arabic word for any type of educational institution, secular or religious (of any religion), whether for elementary instruction or higher learning. The word is variously transliterated '' ...

s, a type of institution which originated in

Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

and had spread west.

The madrasas of Fes, such as the

Bou Inania,

al-Attarine, and

as-Sahrij madrasas, as well as the

Marinid madrasa of

Salé

Salé ( ar, سلا, salā, ; ber, ⵙⵍⴰ, sla) is a city in northwestern Morocco, on the right bank of the Bou Regreg river, opposite the national capital Rabat, for which it serves as a commuter town. Founded in about 1030 by the Banu Ifran ...

and the other

Bou Inania in

Meknes

Meknes ( ar, مكناس, maknās, ; ber, ⴰⵎⴽⵏⴰⵙ, amknas; french: Meknès) is one of the four Imperial cities of Morocco, located in northern central Morocco and the sixth largest city by population in the kingdom. Founded in the 11th c ...

, are considered among the greatest architectural works of this period.

[Kubisch, Natascha (2011). "Maghreb - Architecture" in Hattstein, Markus and Delius, Peter (eds.) ''Islam: Art and Architecture''. h.f.ullmann.] While mosque architecture largely followed the Almohad model, one noted change was the progressive increase in the size of the ''

sahn

A ''sahn'' ( ar, صَحْن, '), is a courtyard in Islamic architecture, especially the formal courtyard of a mosque. Most traditional mosques have a large central ''sahn'', which is surrounded by a ''Riwaq (arcade), riwaq'' or arcade (architect ...

'' or courtyard, which was previously a minor element of the floor plan but which eventually, in the subsequent

Saadian

The Saadi Sultanate (also rendered in English as Sa'di, Sa'did, Sa'dian, or Saadian; ar, السعديون, translit=as-saʿdiyyūn) was a state which ruled present-day Morocco and parts of West Africa in the 16th and 17th centuries. It was l ...

period, became as large as the main prayer hall, and sometimes larger.

Like the Almohads before them, the Marinids created a separate palace-city for themselves; this time, outside Fes. Later known as

Fes Jdid

Fes Jdid or Fes el-Jdid () is one of the three parts of Fez, Morocco. It was founded by the Marinids in 1276 as an extension of Fes el Bali (the old city or ''medina'') and as a royal citadel and capital. It is occupied in large part by the hist ...

, this new fortified citadel had a set of double walls for defense, a new

Grand Mosque, a vast royal garden to the north known as

''el-Mosara'', residences for government officials, and barracks for military garrisons.

Later on, probably in the 15th century, a new

Jewish

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

quarter was created on its south side, the first ''

mellah

A ''mellah'' ( or 'saline area'; and he, מלאח) is a Jewish quarter of a city in Morocco. Starting in the 15th century and especially since the beginning of the 19th century, Jewish communities in Morocco were constrained to live in ''mellah'' ...

'' in Morocco, prefiguring the creation of similar districts in other Moroccan cities in later periods.

The architectural style under the Marinids was very closely related to that found in the

Emirate of Granada

The Emirate of Granada ( ar, إمارة غرﻧﺎﻃﺔ, Imārat Ġarnāṭah), also known as the Nasrid Kingdom of Granada ( es, Reino Nazarí de Granada), was an Emirate, Islamic realm in southern Iberia during the Late Middle Ages. It was the ...

, in Spain, under the contemporary

Nasrid dynasty

The Nasrid dynasty ( ar, بنو نصر ''banū Naṣr'' or ''banū al-Aḥmar''; Spanish: ''Nazarí'') was the last Muslim dynasty in the Iberian Peninsula, ruling the Emirate of Granada from 1230 until 1492. Its members claimed to be of Arab ...

.

The decoration of the famous

Alhambra

The Alhambra (, ; ar, الْحَمْرَاء, Al-Ḥamrāʾ, , ) is a palace and fortress complex located in Granada, Andalusia, Spain. It is one of the most famous monuments of Islamic architecture and one of the best-preserved palaces of the ...

is thus reminiscent of what was built in Fes at the same time. When

Granada

Granada (,, DIN 31635, DIN: ; grc, Ἐλιβύργη, Elibýrgē; la, Illiberis or . ) is the capital city of the province of Granada, in the autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Andalusia, Spain. Granada is located at the fo ...

was conquered in 1492 by

Catholic Spain and the last Muslim realm of al-Andalus came to an end, many of the remaining

Spanish Muslims

Spain is a Christian majority country, with Islam being a minority religion, practised mostly by the immigrants and their descendants from Muslim majority countries. Due to the secular nature of the Spanish constitution, Muslims are free to ...

(and

Jews

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

) fled to Morocco and

North Africa

North Africa, or Northern Africa is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region, and it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of Mauritania in ...

, further increasing the Andalusian influence in these regions in subsequent generations.

The Sharifian dynasties: Saadians and Alaouites (16th–19th centuries)

After the Marinids came the

Saadian dynasty

The Saadi Sultanate (also rendered in English as Sa'di, Sa'did, Sa'dian, or Saadian; ar, السعديون, translit=as-saʿdiyyūn) was a state which ruled present-day Morocco and parts of West Africa in the 16th and 17th centuries. It was l ...

, which marked a political shift from Berber-led empires to

sultan

Sultan (; ar, سلطان ', ) is a position with several historical meanings. Originally, it was an Arabic abstract noun meaning "strength", "authority", "rulership", derived from the verbal noun ', meaning "authority" or "power". Later, it ...

ates led by

Arab

The Arabs (singular: Arab; singular ar, عَرَبِيٌّ, DIN 31635: , , plural ar, عَرَب, DIN 31635: , Arabic pronunciation: ), also known as the Arab people, are an ethnic group mainly inhabiting the Arab world in Western Asia, ...

sharif

Sharīf ( ar, شريف, 'noble', 'highborn'), also spelled shareef or sherif, feminine sharīfa (), plural ashrāf (), shurafāʾ (), or (in the Maghreb) shurfāʾ, is a title used to designate a person descended, or claiming to be descended, fr ...

ian dynasties. Artistically and architecturally, however, there was broad continuity and the Saadians are seen by modern scholars as continuing to refine the existing Moroccan-Moorish style, with some considering the

Saadian Tombs

The Saadian Tombs (, , ) are a historic royal necropolis in Marrakesh, Morocco, located on the south side of the Kasbah Mosque, inside the royal kasbah (citadel) district of the city. They date to the time of the Saadian dynasty and in particul ...

in Marrakesh as one of the apogees of this style.

Starting with the Saadians, and continuing with the

Alaouites

The Alawis, Alawites ( ar, علوية ''Alawīyah''), or pejoratively Nusayris ( ar, نصيرية ''Nuṣayrīyah'') are an ethnoreligious group that lives primarily in Levant and follows Alawism, a sect of Islam that originated from Shia Isl ...

(their successors and the reigning monarchy today), Moroccan art and architecture is portrayed by modern (

Western

Western may refer to:

Places

*Western, Nebraska, a village in the US

*Western, New York, a town in the US

*Western Creek, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western Junction, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western world, countries that id ...

) scholars as having remained essentially "conservative"; meaning that it continued to reproduce the existing style with high fidelity but did not introduce major new innovations.

The Saadians, especially under the sultans

Abdallah al-Ghalib

Abdallah al-Ghalib Billah (; b. 1517 – d. 22 January 1574, 1557–1574) was the second Saadian sultan of Morocco. He succeeded his father Mohammed al-Shaykh as Sultan of Morocco.

Biography

Early life

With his first wife Sayyida Rabia, Mo ...

and

Ahmad al-Mansur

Ahmad al-Mansur ( ar, أبو العباس أحمد المنصور, Ahmad Abu al-Abbas al-Mansur, also al-Mansur al-Dahabbi (the Golden), ar, أحمد المنصور الذهبي; and Ahmed al-Mansour; 1549 in Fes – 25 August 1603, Fes) was the ...

, were extensive builders and benefitted from great economic resources at the height of their power in the late 16th century. In addition to the Saadian Tombs, they also built the

Ben Youssef Madrasa and several major mosques in Marrakesh including the

Mouassine Mosque

The Mouassine Mosque or al-Muwassin Mosque () is a major neighbourhood mosque (a Friday mosque) in Marrakech, Morocco, dating from the 16th century during the Saadian Dynasty. It shares its name with the Mouassine neighbourhood.

History

Ba ...

and the

Bab Doukkala Mosque

The Bab Doukkala Mosque (or Mosque of Bab Doukkala) is a major neighbourhood mosque (a Friday mosque) in Marrakesh, Morocco, dating from the 16th century. It is named after the nearby city gate, Bab Doukkala, in the western city walls. It is als ...

. These two mosques are notable for being part of larger multi-purpose charitable complexes including several other structures like public fountains,

hammams, madrasas, and libraries. This marked a shift from the previous patterns of architectural patronage and may have been influenced by the tradition of building such complexes in

Mamluk architecture

Mamluk architecture was the architectural style under the Mamluk Sultanate (1250–1517), which ruled over Egypt, the Levant, and the Hijaz from their capital, Cairo. Despite their often tumultuous internal politics, the Mamluk sultans were proli ...

in

Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediter ...

and the ''

külliye

A külliye ( ota, كلية) is a complex of buildings associated with Turkish architecture centered on a mosque and managed within a single institution, often based on a waqf (charitable foundation) and composed of a madrasa, a Dar al-Shifa ("cl ...

''s of Ottoman architecture.

The Saadians also rebuilt the royal palace complex in the Kasbah of Marrakesh for themselves, where Ahmad al-Mansur constructed the famous

El Badi Palace

El Badi Palace ( ar, قصر البديع, lit=Palace of Wonder/Brilliance, also frequently translated as the "Incomparable Palace") or Badi' Palace is a ruined palace located in Marrakesh, Morocco. It was commissioned by the sultan Ahmad al-Mans ...

(built between 1578 and 1593) which was known for its superlative decoration and costly building materials including Italian

marble

Marble is a metamorphic rock composed of recrystallized carbonate minerals, most commonly calcite or Dolomite (mineral), dolomite. Marble is typically not Foliation (geology), foliated (layered), although there are exceptions. In geology, the ...

.

The Alaouites, starting with

Moulay Rashid in the mid-17th century, succeeded the Saadians as rulers of Morocco and continue to be the reigning monarchy of the country to this day. As a result, many of the mosques and palaces standing in Morocco today have been built or restored by the Alaouites at some point or another.

Ornate architectural elements from Saadian buildings, most famously from their lavish El Badi Palace in Marrakesh, were also stripped and reused in buildings elsewhere during the reign of

Moulay Isma'il (1672–1727).

Moulay Isma'il is also notable for having built a vast

imperial palace complex – similar to previous palace-citadels but on a grander scale than before – in Meknes, where the remains of his monumental structures can still be seen today.

In his time

Tangier

Tangier ( ; ; ar, طنجة, Ṭanja) is a city in northwestern Morocco. It is on the Moroccan coast at the western entrance to the Strait of Gibraltar, where the Mediterranean Sea meets the Atlantic Ocean off Cape Spartel. The town is the cap ...

was also returned to Moroccan control in 1684, and much of the city's current Moroccan and Islamic architecture dates from his reign or after.

n 1765 Sultan

Mohammed Ben Abdallah

''Sidi'' Mohammed ben Abdallah ''al-Khatib'' ( ar, سيدي محمد بن عبد الله الخطيب), known as Mohammed III ( ar, محمد الثالث), born in 1710 in Fes and died on 9 April 1790 in Meknes, was the Sultan of Morocco from 175 ...

(one of Moulay Isma'il's sons) started the construction of a new port city called

Essaouira

Essaouira ( ; ar, الصويرة, aṣ-Ṣawīra; shi, ⵜⴰⵚⵚⵓⵔⵜ, Taṣṣort, formerly ''Amegdul''), known until the 1960s as Mogador, is a port city in the western Moroccan region of Marakesh-Safi, on the Atlantic coast. It ha ...

(formerly Mogador), located along the Atlantic coast as close as possible to his capital at Marrakesh, to which he tried to move and restrict European trade.

He hired European architects to design the city, resulting in a relatively unique Moroccan-built city with

Western Europe

Western Europe is the western region of Europe. The region's countries and territories vary depending on context.

The concept of "the West" appeared in Europe in juxtaposition to "the East" and originally applied to the ancient Mediterranean ...

an architecture, particularly in the style of its fortifications. Similar coastal fortifications or

bastion

A bastion or bulwark is a structure projecting outward from the curtain wall of a fortification, most commonly angular in shape and positioned at the corners of the fort. The fully developed bastion consists of two faces and two flanks, with fi ...

s, usually known as a , were built at the same time in other port cities like Anfa (present-day

Casablanca

Casablanca, also known in Arabic as Dar al-Bayda ( ar, الدَّار الْبَيْضَاء, al-Dār al-Bayḍāʾ, ; ber, ⴹⴹⴰⵕⵍⴱⵉⴹⴰ, ḍḍaṛlbiḍa, : "White House") is the largest city in Morocco and the country's econom ...

), Rabat,

Larache

Larache ( ar, العرايش, al-'Araysh) is a city in northwestern Morocco. It is on the Moroccan coast, where the Loukkos River meets the Atlantic Ocean. Larache is one of the most important cities of the Tanger-Tetouan-Al Hoceima region.

Many ...

, and Tangier.

Up until the late 19th century and early 20th century, the Alaouite sultans and their ministers continued to build beautiful palaces, many of which are now used as museums or tourist attractions, such as the

Bahia Palace in Marrakesh, the

Dar Jamaï in Meknes, and the

Dar Batha

Dar Batḥa ( ar, دار البطحاء, pronounced ''Bat-ḥaa''), or Qasr al-Batḥa ( ar, قصر البطحاء), is a former royal palace in the city of Fez, Morocco. The palace was commissioned by the Alaouite Sultan Hassan I in the late 19th ...

in Fes.

Modern and contemporary architecture: 20th century to present day

In the 20th century, Moroccan architecture and cities were also shaped by the period of

French colonial control (1912–1956) as well as

Spanish colonial rule in the north of the country (1912–1958). This era introduced new architectural styles such as

Art Nouveau

Art Nouveau (; ) is an international style of art, architecture, and applied art, especially the decorative arts. The style is known by different names in different languages: in German, in Italian, in Catalan, and also known as the Modern ...

,

Art Deco

Art Deco, short for the French ''Arts Décoratifs'', and sometimes just called Deco, is a style of visual arts, architecture, and product design, that first appeared in France in the 1910s (just before World War I), and flourished in the Unite ...

, and other

modernist

Modernism is both a philosophical and arts movement that arose from broad transformations in Western society during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The movement reflected a desire for the creation of new forms of art, philosophy, an ...

styles, in addition to European ideas about

urban planning

Urban planning, also known as town planning, city planning, regional planning, or rural planning, is a technical and political process that is focused on the development and design of land use and the built environment, including air, water, ...

imposed by colonial authorities. The European architects and planners also drew on traditional Moroccan architecture to develop a style sometimes referred to as ''Neo-Mauresque'' (a type of

Neo-Moorish

Moorish Revival or Neo-Moorish is one of the exotic revival architectural styles that were adopted by architects of Europe and the Americas in the wake of Romanticist Orientalism. It reached the height of its popularity after the mid-19th centur ...

style), blending contemporary European architecture with a "

pastiche

A pastiche is a work of visual art, literature, theatre, music, or architecture that imitates the style or character of the work of one or more other artists. Unlike parody, pastiche pays homage to the work it imitates, rather than mocking it ...

" of traditional Moroccan architecture.

The French moved the capital to Rabat and founded a number of ''

Villes Nouvelles'' ("New Cities") next to the historic

medinas (old walled cities) to act as new administrative centers, which have since grown beyond the old cities. In particular,

Casablanca

Casablanca, also known in Arabic as Dar al-Bayda ( ar, الدَّار الْبَيْضَاء, al-Dār al-Bayḍāʾ, ; ber, ⴹⴹⴰⵕⵍⴱⵉⴹⴰ, ḍḍaṛlbiḍa, : "White House") is the largest city in Morocco and the country's econom ...

was developed into a major port and quickly became the country's most populous urban centre.

As a result, the

city's architecture became a major showcase of Art Deco and colonial ''Mauresque'' architecture. Notable examples include the civic buildings of

Muhammad V Square (''Place Mohammed V''), the

Cathedral of Sacré-Coeur, the Art Deco-style

Cinéma Rialto, the Neo-Moorish-style

Mahkamat al-Pasha

Mahkamat al-Pasha ( "the pasha's courthouse," ) is an administrative building constructed 1941-1942 in the Hubous neighborhood of Casablanca, Morocco. The complex serves or has served as a courthouse, residence of the pasha (governor), parliament ...

in the

Habous district.

Similar architecture also appeared in other major cities like Rabat and

Tangier

Tangier ( ; ; ar, طنجة, Ṭanja) is a city in northwestern Morocco. It is on the Moroccan coast at the western entrance to the Strait of Gibraltar, where the Mediterranean Sea meets the Atlantic Ocean off Cape Spartel. The town is the cap ...

, with examples such as the ''

Gran Teatro Cervantes

Gran Teatro Cervantes is a theatre, dedicated to Miguel de Cervantes, in Tangier, Morocco. The theatre was built in 1913 by the Spanish.

History

The construction was led by Esperanza Orellana, her husband Manuel Peña and the owner

Ownership ...

'' in Tangier and the

Bank al-Maghrib

The Bank Al-Maghrib ( ar, بنك المغرب, ) is the central bank of the Kingdom of Morocco. It was founded in 1959 as the successor to the State Bank of Morocco (est. 1907). In 2008 Bank Al-Maghrib held reserves of foreign currency with an e ...

and

post office

A post office is a public facility and a retailer that provides mail services, such as accepting letters and parcels, providing post office boxes, and selling postage stamps, packaging, and stationery. Post offices may offer additional serv ...

buildings in downtown Rabat. Elsewhere, the smaller southern town of

Sidi Ifni

Sidi Ifni ( Berber: ''Ifni'', ⵉⴼⵏⵉ, ar, سيدي إفني) is a city located on the west coast of Morocco, on the shores of the Atlantic Ocean, with a population of 20,051 people. The economic base of the city is fishing. It is located in ...

is also notable for Art Deco architecture dating from the Spanish occupation.

Elie Azagury

Elie Azagury (; 1918-2009) was an influential Moroccan architect and director of the (GAMMA) after Moroccan independence in 1956. He is considered the first Moroccan modernist architect, with works in cities such as Casablanca, Tangier, and Agadi ...

became the first

Moroccan modernist architect in the 1950s.

In the later 20th century and into the 21st century, contemporary Moroccan architecture also continued to pay tribute to the country's traditional architecture. In some cases, international architects were recruited to design Moroccan-style buildings for major royal projects such as the

Mausoleum of Mohammed V

The Mausoleum of Mohammed V ( ar, ضريح محمد الخامس) is a mausoleum located across from the Hassan Tower in Rabat, Morocco. It contains the tombs of the Moroccan king Mohammed V and his two sons, late King Hassan II and Prince Abdal ...

in Rabat and the massive

Hassan II Mosque

The Hassan II Mosque ( ar, مسجد الحسن الثاني, french: Grande Mosquée Hassan II) is a mosque in Casablanca, Morocco. It is the largest functioning mosque in Africa and is the List of largest mosques, 7th largest in the world. Its ...

in Casablanca.

The monumental new gates of the

Royal Palace in Fez, built in 1969–1971, also made use of traditional Moroccan craftsmanship.

The new

train stations of Marrakesh and

Fes

Fez or Fes (; ar, فاس, fās; zgh, ⴼⵉⵣⴰⵣ, fizaz; french: Fès) is a city in northern inland Morocco and the capital of the Fès-Meknès administrative region. It is the second largest city in Morocco, with a population of 1.11 mi ...

are examples of traditional Moroccan forms being adapted to modern architecture. Modernist architecture has also continued to be used, exemplified by buildings like the

Sunna Mosque (1966) and the

Twin Center (1999) in Casablanca. More recently, some 21st-century examples of major or prestigious architecture projects include the extension of Marrakesh's

Menara Airport (completed in 2008), the

National Library of Morocco in Rabat (2008), the award-winning High-Speed Train Station in

Kenitra

Kenitra ( ar, القُنَيْطَرَة, , , ; ber, ⵇⵏⵉⵟⵔⴰ, Qniṭra; french: Kénitra) is a city in north western Morocco, formerly known as Port Lyautey from 1932 to 1956. It is a port on the Sebou River, Sebou river, has a popul ...

(opened in 2018), the

Finance City Tower in Casablanca (completed in 2019 and one of the

tallest buildings in Morocco), and the new

Grand Theatre of Rabat by

Zaha Hadid

Dame Zaha Mohammad Hadid ( ar, زها حديد ''Zahā Ḥadīd''; 31 October 1950 – 31 March 2016) was an Iraqi-British architect, artist and designer, recognised as a major figure in architecture of the late 20th and early 21st centu ...

(due to be completed in late 2019).

Influences

Roman and pre-Islamic

As with the rest of the

Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on the e ...

world, the culture and monuments of

Classical Antiquity

Classical antiquity (also the classical era, classical period or classical age) is the period of cultural history between the 8th century BC and the 5th century AD centred on the Mediterranean Sea, comprising the interlocking civilizations of ...

and of

Late Antiquity

Late antiquity is the time of transition from classical antiquity to the Middle Ages, generally spanning the 3rd–7th century in Europe and adjacent areas bordering the Mediterranean Basin. The popularization of this periodization in English ha ...

had an important influence on the architecture of the Islamic world that came after them. In Morocco, the former Roman city of

Volubilis

Volubilis (; ar, وليلي, walīlī; ber, ⵡⵍⵉⵍⵉ, wlili) is a partly excavated Berber-Roman city in Morocco situated near the city of Meknes, and may have been the capital of the kingdom of Mauretania, at least from the time of Kin ...

acted as the first Idrisid capital before the foundation of Fes.

The columns and

capitals of Roman and early Christian monuments were frequently re-used as

spolia

''Spolia'' (Latin: 'spoils') is repurposed building stone for new construction or decorative sculpture reused in new monuments. It is the result of an ancient and widespread practice whereby stone that has been quarried, cut and used in a built ...

in the early mosques of the region – although this was far less common in Morocco, where Roman remains were far sparser.

Later Islamic capitals developed from these models in turn.

In other examples, the vegetal and floral motifs of Late Antiquity formed one of the bases from which Islamic-era

arabesque

The arabesque is a form of artistic decoration consisting of "surface decorations based on rhythmic linear patterns of scrolling and interlacing foliage, tendrils" or plain lines, often combined with other elements. Another definition is "Foli ...

motifs were derived.

The iconic horseshoe arch or "moorish" arch, which became a regular feature of Moroccan and Moorish architecture, also had some precedents in

Byzantine

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

and

Visigothic

The Visigoths (; la, Visigothi, Wisigothi, Vesi, Visi, Wesi, Wisi) were an early Germanic people who, along with the Ostrogoths, constituted the two major political entities of the Goths within the Roman Empire in late antiquity, or what is kno ...

buildings.

Lastly, another major legacy of

Greco-Roman

The Greco-Roman civilization (; also Greco-Roman culture; spelled Graeco-Roman in the Commonwealth), as understood by modern scholars and writers, includes the geographical regions and countries that culturally—and so historically—were di ...

heritage was the continuation and proliferation of

public bathhouses, known as ''

hammam

A hammam ( ar, حمّام, translit=ḥammām, tr, hamam) or Turkish bath is a type of steam bath or a place of public bathing associated with the Islamic world. It is a prominent feature in the culture of the Muslim world and was inherited f ...

''s, across the Islamic world – including Morocco – which were closely based on Roman ''

thermae

In ancient Rome, (from Greek , "hot") and (from Greek ) were facilities for bathing. usually refers to the large Roman Empire, imperial public bath, bath complexes, while were smaller-scale facilities, public or private, that existed i ...

'' and took on added social roles.

Islamic-era Middle East

The arrival of Islam with Arab conquerors from the east in the early 8th century brought about social changes which also required the introduction of new building types such as mosques. The latter followed more or less the model of other hypostyle mosques which were common across much of the Islamic world at the time.

The traditions of

Islamic art

Islamic art is a part of Islamic culture and encompasses the visual arts produced since the 7th century CE by people who lived within territories inhabited or ruled by Muslim populations. Referring to characteristic traditions across a wide ra ...

also introduced certain aesthetic values, most notably a general preference for avoiding

figurative images due to a religious taboo on

icon

An icon () is a religious work of art, most commonly a painting, in the cultures of the Eastern Orthodox, Oriental Orthodox, and Catholic churches. They are not simply artworks; "an icon is a sacred image used in religious devotion". The most ...

s or worshipped images.

This

aniconism in Islamic culture caused artists to explore non-figural art, and created a general aesthetic shift toward

mathematically-based decoration, such as geometric patterns, as well as other relatively abstract motifs like arabesques. While figurative images did continue to appear in Islamic art, by the 14th century these were generally absent in the architecture of the western regions of the Islamic world like Morocco.

Some figural images of animals still appeared occasionally in royal palaces, such as the sculptures of lions and leopards in the monumental fountain of a former Saadian palace in the Agdal Gardens.

Aside from the initial changes brought about by the arrival of Islam, Moroccan culture and architecture continued afterwards to adopt certain ideas and imports from the eastern parts of the Islamic world. These include some of the institutions and building types that became characteristic of the historic Muslim world. For example,

bimaristan

A bimaristan (; ), also known as ''dar al-shifa'' (also ''darüşşifa'' in Turkish) or simply maristan, is a hospital in the historic Islamic world.

Etymology

''Bimaristan'' is a Persian word ( ''bīmārestān'') meaning "hospital", with '' ...

s, historical equivalents of hospitals, first originated further east in

Iraq

Iraq,; ku, عێراق, translit=Êraq officially the Republic of Iraq, '; ku, کۆماری عێراق, translit=Komarî Êraq is a country in Western Asia. It is bordered by Turkey to Iraq–Turkey border, the north, Iran to Iran–Iraq ...

, with the first one being built by

Harun al-Rashid

Abu Ja'far Harun ibn Muhammad al-Mahdi ( ar

, أبو جعفر هارون ابن محمد المهدي) or Harun ibn al-Mahdi (; or 766 – 24 March 809), famously known as Harun al-Rashid ( ar, هَارُون الرَشِيد, translit=Hārūn ...

(between 786 and 809).

They spread westward and first appeared in

Morocco

Morocco (),, ) officially the Kingdom of Morocco, is the westernmost country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It overlooks the Mediterranean Sea to the north and the Atlantic Ocean to the west, and has land borders with Algeria to ...

around the late 12th century when the Almohads founded a maristan in Marrakesh.

Madrasa

Madrasa (, also , ; Arabic: مدرسة , pl. , ) is the Arabic word for any type of educational institution, secular or religious (of any religion), whether for elementary instruction or higher learning. The word is variously transliterated '' ...

s, another important institution, first originated in

Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

in the early 11th century under

Nizam al-Mulk

Abu Ali Hasan ibn Ali Tusi (April 10, 1018 – October 14, 1092), better known by his honorific title of Nizam al-Mulk ( fa, , , Order of the Realm) was a Persian scholar, jurist, political philosopher and Vizier of the Seljuk Empire. Rising fro ...

, and were progressively adopted further west.

The first madrasa in Morocco (

Madrasat as-Saffarin) was built in Fes by the Marinids in 1271, and madrasas further proliferated in the 14th century.

In terms of decorative motifs, ''muqarnas,'' a notable feature of Moroccan architecture introduced in the Almoravid period in the 12th century,

also originated at first in Iran before spreading to the west.

Al-Andalus (Muslim Spain and Portugal)

The culture of Muslim-controlled Al-Andalus, which existed across much of the Iberian Peninsula to the north between 711 and 1492, also had close influence on Moroccan history and architecture in a number of ways – and was in turn influenced by Moroccan cultural and political movements.

Jonathan Bloom

Jonathan Max Bloom (born April 7, 1950) is an American art historian and educator. Bloom has served as the dual Norma Jean Calderwood University Professor of Islamic and Asian Art at Boston College, along with his wife, Sheila Blair.

Career

Bl ...

, in his overview of western Islamic architecture, remarks that he "treats the architecture of North Africa and the Iberian Peninsula together because the

Straits of Gibraltar

The Strait of Gibraltar ( ar, مضيق جبل طارق, Maḍīq Jabal Ṭāriq; es, Estrecho de Gibraltar, Archaic: Pillars of Hercules), also known as the Straits of Gibraltar, is a narrow strait that connects the Atlantic Ocean to the Medit ...

were less of a barrier and more of a bridge."

In addition to the geographic proximity of the two regions, there were many waves of immigration from Al-Andalus to Morocco of both Muslims and Jews. One of the earliest waves were the Arab exiles from Cordoba who came to Fes after a failed rebellion in the early 9th century. This population transfer culminated in the waves of refugees that came after the

fall of Granada

The Granada War ( es, Guerra de Granada) was a series of military campaigns between 1482 and 1491 during the reign of the Catholic Monarchs, Isabella I of Castile and Ferdinand II of Aragon, against the Nasrid dynasty's Emirate of Granada. It e ...

in 1492, including many former elites and members of the Andalusi educated classes.

These immigrants played important roles in Moroccan society. Among other examples, it was the early Arab exiles from Cordoba who gave the Andalusiyyin quarter of Fes its name

and it was Andalusi refugees in the 16th century who rebuilt and expanded the northern city of

Tétouan

Tétouan ( ar, تطوان, tiṭwān, ber, ⵜⵉⵟⵟⴰⵡⴰⵏ, tiṭṭawan; es, Tetuán) is a city in northern Morocco. It lies along the Martil Valley and is one of the two major ports of Morocco on the Mediterranean Sea, a few miles so ...

.

The period of the

Umayyad Emirate

The Umayyad Caliphate (661–750 CE; , ; ar, ٱلْخِلَافَة ٱلْأُمَوِيَّة, al-Khilāfah al-ʾUmawīyah) was the second of the four major caliphates established after the death of Muhammad. The caliphate was ruled by the ...

and Caliphate in Cordoba, which marked the peak of Muslim power in Al-Andalus, was an especially crucial era which saw the construction of some of the region's most important early Islamic monuments. The Great Mosque of Cordoba is frequently cited by scholars as a major influence on the subsequent architecture of the western regions of the Islamic world due to both its architectural innovations and its symbolic importance as the religious heart of the powerful Cordoban Caliphate.

Many of its features, such as the ornamental ribbed domes,

the

minbar

A minbar (; sometimes romanized as ''mimber'') is a pulpit in a mosque where the imam (leader of prayers) stands to deliver sermons (, ''khutbah''). It is also used in other similar contexts, such as in a Hussainiya where the speaker sits and le ...

, and the polygonal

mihrab

Mihrab ( ar, محراب, ', pl. ') is a niche in the wall of a mosque that indicates the ''qibla'', the direction of the Kaaba in Mecca towards which Muslims should face when praying. The wall in which a ''mihrab'' appears is thus the "qibla w ...

chamber, would go on to be recurring models of later elements in the Islamic architecture of the wider region.

Likewise, the decorative layout of the ''Bab al-Wuzara gateway, the original western gate of the mosque, demonstrates many of the standard elements that recur in the gateways and mihrabs of subsequent periods: namely, a horseshoe arch with decorated

voussoir

A voussoir () is a wedge-shaped element, typically a stone, which is used in building an arch or vault.

Although each unit in an arch or vault is a voussoir, two units are of distinct functional importance: the keystone and the springer. The ...

s, a rectangular ''

alfiz The alfiz (, from Andalusi Arabic ''alḥíz'', from Standard Arabic ''alḥáyyiz'', meaning 'the container';Alf ...

'' frame, and an inscription band.

Georges Marçais

Georges Marçais ( Rennes, 11 March 1876 – Paris, 20 May 1962) was a French orientalist, historian, and scholar of Islamic art and architecture who specialized in the architecture of North Africa.

Biography

He initially trained as a painter ...

(an important 20th-century scholar on this subject

) also traces the origins of some later architectural features directly to the complex arches of

Al-Hakam II

Al-Hakam II, also known as Abū al-ʿĀṣ al-Mustanṣir bi-Llāh al-Hakam b. ʿAbd al-Raḥmān (; January 13, 915 – October 16, 976), was the Caliph of Córdoba. He was the second ''Umayyad'' Caliph of Córdoba in Al-Andalus, and son of Ab ...

's 10th-century expansion of the mosque, namely the

polylobed arches found throughout the region after the 10th century and the ''

sebka

''Sebka'' () refers to a type of decorative motif used in western Islamic ("Moorish") architecture and Mudéjar architecture.

History and description

Various types of interlacing rhombus-like motifs are heavily featured on the surfaces of ...

'' motif which became ubiquitous in Moroccan architecture after the Almohad period (12th-13th centuries).

Moreover, for much of the 10th century the Caliphate of Cordoba held northern Morocco in its

sphere of influence

In the field of international relations, a sphere of influence (SOI) is a spatial region or concept division over which a state or organization has a level of cultural, economic, military or political exclusivity.

While there may be a formal al ...

. During this period Caliph

Abd ar-Rahman III

ʿAbd al-Rahmān ibn Muḥammad ibn ʿAbd Allāh ibn Muḥammad ibn ʿAbd al-Raḥmān ibn al-Ḥakam al-Rabdī ibn Hishām ibn ʿAbd al-Raḥmān al-Dākhil () or ʿAbd al-Rahmān III (890 - 961), was the Umayyad Emir of Córdoba from 912 to 92 ...

contributed to the architecture of Fes by sponsoring the expansion of the Qarawiyyin Mosque.

The same caliph also oversaw the construction of the first minaret of Cordoba's mosque, whose shape – a square-based shaft with a secondary lantern tower above it – some scholars see as precursor to other minarets in al-Andalus and Morocco.

Around the same time, in 756, he also sponsored the construction of a similar (though simpler) minaret for the Qarawiyyin Mosque, while the Umayyad governor of Fes sponsored the construction of a similar minaret for the Al-Andalusiyyin Mosque across the river.

Starting in the 11th century, the Berber-led Almoravid and Almohad empires, which were based in Morocco but also controlled al-Andalus, were instrumental in combining the artistic trends of both North Africa and al-Andalus, leading to what eventually became the definitive "Hispano-Moorish" or Andalusi-Maghribi style of the region.

The famous

Almoravid Minbar in Marrakesh, commissioned from a workshop of craftsmen in Cordoba, is one of the examples illustrating this cross-continental sharing of art and forms.

These traditions of Moorish art and architecture were continued in Morocco (and the wider Maghreb) well after the end of Muslim rule on the Iberian Peninsula.

Amazigh (Berber)

The