|

Regenerative Cooling

Regenerative cooling is a method of cooling gases in which compressed gas is cooled by allowing it to expand and thereby take heat from the surroundings. The cooled expanded gas then passes through a heat exchanger where it cools the incoming compressed gas. Regenerative cycles *Stirling cycle * Gifford–McMahon cycle * Vuilleumier cycle *Pulse tube refrigerator History In 1857, Siemens introduced the regenerative cooling concept with the Siemens cycle. In 1895, William Hampson in England and Carl von Linde in Germany independently developed and patented the Hampson–Linde cycle to liquefy air using the Joule–Thomson expansion process and regenerative cooling. On 10 May 1898, James Dewar used regenerative cooling to become the first to statically liquefy hydrogen. See also *Cryocooler *Displacer *Fluid mechanics *Regenerative cooling (rocket) *Regenerative heat exchanger *Thermodynamic cycle A thermodynamic cycle consists of a linked sequence of thermodynamic processes ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Heat Transfer

Heat transfer is a discipline of thermal engineering that concerns the generation, use, conversion, and exchange of thermal energy (heat) between physical systems. Heat transfer is classified into various mechanisms, such as thermal conduction, Convection (heat transfer), thermal convection, thermal radiation, and transfer of energy by phase changes. Engineers also consider the transfer of mass of differing chemical species (mass transfer in the form of advection), either cold or hot, to achieve heat transfer. While these mechanisms have distinct characteristics, they often occur simultaneously in the same system. Heat conduction, also called diffusion, is the direct microscopic exchanges of kinetic energy of particles (such as molecules) or quasiparticles (such as lattice waves) through the boundary between two systems. When an object is at a different temperature from another body or its surroundings, heat flows so that the body and the surroundings reach the same temperature, ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Liquid Hydrogen

Liquid hydrogen (LH2 or LH2) is the liquid state of the element hydrogen. Hydrogen is found naturally in the molecular H2 form. To exist as a liquid, H2 must be cooled below its critical point of 33 K. However, for it to be in a fully liquid state at atmospheric pressure, H2 needs to be cooled to .IPTS-1968 iupac.org, accessed 2020-01-01 A common method of obtaining liquid hydrogen involves a compressor resembling a jet engine in both appearance and principle. Liquid hydrogen is typically used as a concentrated form of . Storing it as liquid takes less space than storing it as a gas at ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Thermodynamic Cycles

A thermodynamic cycle consists of a linked sequence of thermodynamic processes that involve transfer of heat and work into and out of the system, while varying pressure, temperature, and other state variables within the system, and that eventually returns the system to its initial state. In the process of passing through a cycle, the working fluid (system) may convert heat from a warm source into useful work, and dispose of the remaining heat to a cold sink, thereby acting as a heat engine. Conversely, the cycle may be reversed and use work to move heat from a cold source and transfer it to a warm sink thereby acting as a heat pump. If at every point in the cycle the system is in thermodynamic equilibrium, the cycle is reversible. Whether carried out reversible or irreversibly, the net entropy change of the system is zero, as entropy is a state function. During a closed cycle, the system returns to its original thermodynamic state of temperature and pressure. Process quantities ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Cryogenics

In physics, cryogenics is the production and behaviour of materials at very low temperatures. The 13th IIR International Congress of Refrigeration (held in Washington DC in 1971) endorsed a universal definition of “cryogenics” and “cryogenic” by accepting a threshold of 120 K (or –153 °C) to distinguish these terms from the conventional refrigeration. This is a logical dividing line, since the normal boiling points of the so-called permanent gases (such as helium, hydrogen, neon, nitrogen, oxygen, and normal air) lie below 120K while the Freon refrigerants, hydrocarbons, and other common refrigerants have boiling points above 120K. The U.S. National Institute of Standards and Technology considers the field of cryogenics as that involving temperatures below -153 Celsius (120K; -243.4 Fahrenheit) Discovery of superconducting materials with critical temperatures significantly above the boiling point of nitrogen has provided new interest in reliable, low cost method ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Cooling Technology

Cooling is removal of heat, usually resulting in a lower temperature and/or phase change. Temperature lowering achieved by any other means may also be called cooling.ASHRAE Terminology, https://www.ashrae.org/technical-resources/free-resources/ashrae-terminology The transfer of thermal energy may occur via thermal radiation, heat conduction or convection. Examples can be as simple as reducing temperature of a coffee. Devices *Coolant *Cooling towers, as used in large industrial plants and power stations * Daytime passive radiative cooler *Evaporative cooler *Heat exchanger *Heat pipe *Heat sink *HVAC (Heating, Ventilation and Air Conditioning) * Intercooler *Radiative cooling in Heat shields * Radiators in automobiles *Pumpable ice technology *Thermoelectric cooling *Vortex tube The vortex tube, also known as the Ranque-Hilsch vortex tube, is a mechanical device that separates a compressed gas into hot and cold streams. The gas emerging from the hot end can reach temperature ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Timeline Of Hydrogen Technologies

This is a timeline of the history of hydrogen technology. Timeline 16th century * c. 1520 – First recorded observation of hydrogen by Paracelsus through dissolution of metals (iron, zinc, and tin) in sulfuric acid. 17th century * 1625 – First description of hydrogen by Johann Baptista van Helmont. First to use the word "gas". * 1650 – Turquet de Mayerne obtained a gas or "inflammable air" by the action of dilute sulphuric acid on iron. * 1662 – Boyle's law (gas law relating pressure and volume) * 1670 – Robert Boyle produced hydrogen by reacting metals with acid. * 1672 – "New Experiments touching the Relation between Flame and Air" by Robert Boyle. * 1679 – Denis Papin – safety valve * 1700 – Nicolas Lemery showed that the gas produced in the sulfuric acid/iron reaction was explosive in air 18th century * 1755 – Joseph Black confirmed that different gases exist. / Latent heat * 1766 – Henry Cavendish published in "On Factitious Airs" a description of " ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Thermodynamic Cycle

A thermodynamic cycle consists of a linked sequence of thermodynamic processes that involve transfer of heat and work into and out of the system, while varying pressure, temperature, and other state variables within the system, and that eventually returns the system to its initial state. In the process of passing through a cycle, the working fluid (system) may convert heat from a warm source into useful work, and dispose of the remaining heat to a cold sink, thereby acting as a heat engine. Conversely, the cycle may be reversed and use work to move heat from a cold source and transfer it to a warm sink thereby acting as a heat pump. If at every point in the cycle the system is in thermodynamic equilibrium, the cycle is reversible. Whether carried out reversible or irreversibly, the net entropy change of the system is zero, as entropy is a state function. During a closed cycle, the system returns to its original thermodynamic state of temperature and pressure. Process quantities ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Regenerative Heat Exchanger

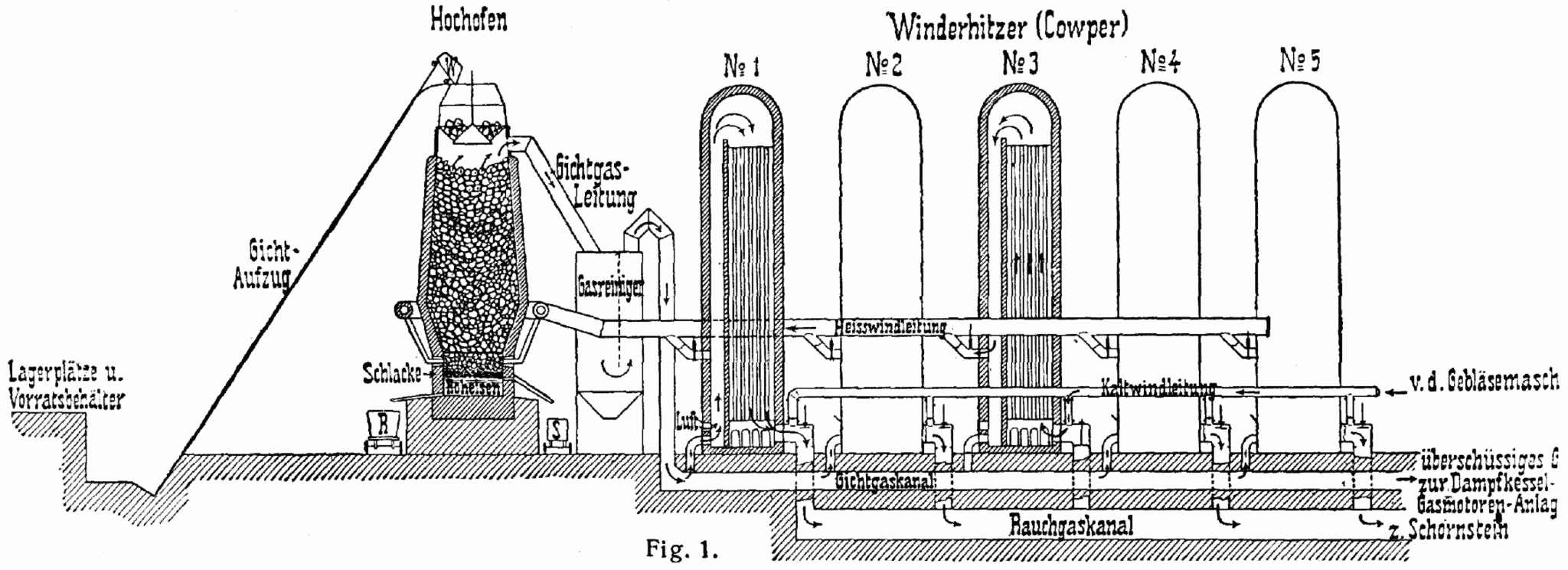

A regenerative heat exchanger, or more commonly a regenerator, is a type of heat exchanger where heat from the hot fluid is intermittently stored in a thermal storage medium before it is transferred to the cold fluid. To accomplish this the hot fluid is brought into contact with the heat storage medium, then the fluid is displaced with the cold fluid, which absorbs the heat. In regenerative heat exchangers, the fluid on either side of the heat exchanger can be the same fluid. The fluid may go through an external processing step, and then it is flowed back through the heat exchanger in the opposite direction for further processing. Usually the application will use this process cyclically or repetitively. Regenerative heating was one of the most important technologies developed during the Industrial Revolution when it was used in the hot blast process on blast furnaces. It was later used in glass melting furnaces and steel making, to increase the efficiency of open hearth furnaces, ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Regenerative Cooling (rocket)

Regenerative cooling, in the context of rocket engine design, is a configuration in which some or all of the propellant is passed through tubes, channels, or in a jacket around the combustion chamber or nozzle to cool the engine. This is effective because the propellants are often cryogenic. The heated propellant is then fed into a special gas-generator or injected directly into the main combustion chamber. History In 1857 Carl Wilhelm Siemens introduced the concept of regenerative cooling. On 10 May 1898, James Dewar used regenerative cooling to become the first to statically liquefy hydrogen. The concept of regenerative cooling was also mentioned in 1903 in an article by Konstantin Tsiolkovsky. Robert Goddard built the first regeneratively cooled engine in 1923, but rejected the scheme as too complex. A regeneratively cooled engine was built by the Italian researcher, Gaetano Arturo Crocco in 1930. The first Soviet engines to employ the technique were Fridrikh Tsander's OR-2 ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Fluid Mechanics

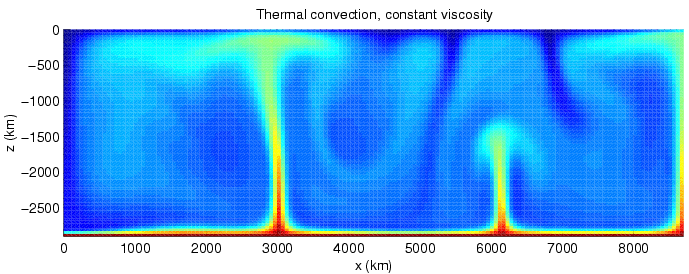

Fluid mechanics is the branch of physics concerned with the mechanics of fluids ( liquids, gases, and plasmas) and the forces on them. It has applications in a wide range of disciplines, including mechanical, aerospace, civil, chemical and biomedical engineering, geophysics, oceanography, meteorology, astrophysics, and biology. It can be divided into fluid statics, the study of fluids at rest; and fluid dynamics, the study of the effect of forces on fluid motion. It is a branch of continuum mechanics, a subject which models matter without using the information that it is made out of atoms; that is, it models matter from a ''macroscopic'' viewpoint rather than from ''microscopic''. Fluid mechanics, especially fluid dynamics, is an active field of research, typically mathematically complex. Many problems are partly or wholly unsolved and are best addressed by numerical methods, typically using computers. A modern discipline, called computational fluid dynamics (CFD), is dev ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Displacer

A Stirling engine is a heat engine that is operated by the cyclic compression and expansion of air or other gas (the ''working fluid'') between different temperatures, resulting in a net conversion of heat energy to mechanical work. More specifically, the Stirling engine is a closed-cycle regenerative heat engine with a permanent gaseous working fluid. ''Closed-cycle'', in this context, means a thermodynamic system in which the working fluid is permanently contained within the system, and ''regenerative'' describes the use of a specific type of internal heat exchanger and thermal store, known as the ''regenerator''. Strictly speaking, the inclusion of the regenerator is what differentiates a Stirling engine from other closed-cycle hot air engines. In the Stirling engine, a gas is heated and expanded by energy supplied from outside the engine's interior space (cylinder). It is then shunted to a different location within the engine, where it is cooled and compressed. A piston (o ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

James Dewar

Sir James Dewar (20 September 1842 – 27 March 1923) was a British chemist and physicist. He is best known for his invention of the vacuum flask, which he used in conjunction with research into the liquefaction of gases. He also studied atomic and molecular spectroscopy, working in these fields for more than 25 years. Early life James Dewar was born in Kincardine, Perthshire (now in Fife) in 1842, the youngest of six boys of Ann Dewar and Thomas Dewar, a vintner. He was educated at Kincardine Parish School and then Dollar Academy. His parents died when he was 15. He attended the University of Edinburgh where he studied chemistry under Lyon Playfair (later Baron Playfair), becoming Playfair's personal assistant. Dewar also studied under August Kekulé at Ghent. Career In 1875, Dewar was elected Jacksonian professor of natural experimental philosophy at the University of Cambridge, becoming a member of Peterhouse. He became a member of the Royal Institution and later, in 18 ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

.png)