Zeppelin D Class on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

A Zeppelin is a type of

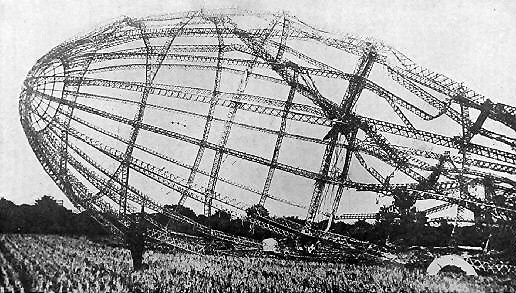

The principal feature of the Zeppelin's design was a fabric-covered, rigid metal framework of transverse rings and longitudinal girders enclosing a number of individual gasbags. This allowed the craft to be much larger than

The principal feature of the Zeppelin's design was a fabric-covered, rigid metal framework of transverse rings and longitudinal girders enclosing a number of individual gasbags. This allowed the craft to be much larger than

In 1898, Count Zeppelin founded the ''Gesellschaft zur Förderung der Luftschiffahrt'' (Society for the Promotion of Airship Flight), contributing more than half of its 800,000

In 1898, Count Zeppelin founded the ''Gesellschaft zur Förderung der Luftschiffahrt'' (Society for the Promotion of Airship Flight), contributing more than half of its 800,000  This accident would have finished Zeppelin's experiments, but his flights had generated huge public interest and a sense of national pride regarding his work, and spontaneous donations from the public began pouring in, eventually totalling over six million marks. This enabled the Count to found the '' Luftschiffbau Zeppelin GmbH'' (Airship Construction Zeppelin Ltd.) and the Zeppelin Foundation.

This accident would have finished Zeppelin's experiments, but his flights had generated huge public interest and a sense of national pride regarding his work, and spontaneous donations from the public began pouring in, eventually totalling over six million marks. This enabled the Count to found the '' Luftschiffbau Zeppelin GmbH'' (Airship Construction Zeppelin Ltd.) and the Zeppelin Foundation.

Before World War I (1914–1918) the Zeppelin company manufactured 21 more airships. The

Before World War I (1914–1918) the Zeppelin company manufactured 21 more airships. The  On 24 April 1912, the

On 24 April 1912, the

p. 256.

/ref> Although Zeppelin bombing raids, especially those aimed at London, captivated the German public’s imagination, they had limited material success. Nevertheless, these raids—along with later bombing raids by airplanes—led to the diversion of men and resources from the Western Front. Additionally, the fear of these attacks impacted industrial production to some extent. Early offensive operations by Army airships quickly revealed their extreme vulnerability to ground fire when flown at low altitudes, leading to the loss of several airships. Since no dedicated bombs had been developed at the time, these early raids dropped artillery shells instead. * On August 5, 1914, the airship Z VI bombed At the instigation of the Kaiser a plan was made to bomb

At the instigation of the Kaiser a plan was made to bomb

The main use of the airship was in reconnaissance over the

The main use of the airship was in reconnaissance over the

At the beginning of the conflict, the German command had high hopes for the airships, which were considerably more capable than contemporary light fixed-wing machines: they were almost as fast, could carry multiple machine guns, and had enormously greater

At the beginning of the conflict, the German command had high hopes for the airships, which were considerably more capable than contemporary light fixed-wing machines: they were almost as fast, could carry multiple machine guns, and had enormously greater

The first raid of 1916 was carried out by the German Navy. Nine Zeppelins were sent to Liverpool on the night of 31 January – 1 February. A combination of poor weather and mechanical problems scattered them across the

The first raid of 1916 was carried out by the German Navy. Nine Zeppelins were sent to Liverpool on the night of 31 January – 1 February. A combination of poor weather and mechanical problems scattered them across the  L 32 was piloted by ''Oberleutnant'' Werner Peterson of the Naval Airship Service, who had only taken command of L 32 in August 1916. L 32 approached from the south, crossing the English Channel close to Dungeness light house, passing Tunbridge Wells at 12:10 and dropping bombs on

L 32 was piloted by ''Oberleutnant'' Werner Peterson of the Naval Airship Service, who had only taken command of L 32 in August 1916. L 32 approached from the south, crossing the English Channel close to Dungeness light house, passing Tunbridge Wells at 12:10 and dropping bombs on

At the beginning of the war Captain Ernst A. Lehmann and Baron Gemmingen, Count Zeppelin's nephew, developed an

At the beginning of the war Captain Ernst A. Lehmann and Baron Gemmingen, Count Zeppelin's nephew, developed an

Under these circumstances, Eckener managed to obtain an order for the next American dirigible. Germany had to pay for this airship itself, as the cost was set against the war reparation accounts, but for the Zeppelin company this was unimportant. LZ 126 made its first flight on 27 August 1924.

On 12 October at 07:30 local time the Zeppelin took off for the US under the command of Hugo Eckener. The ship completed its voyage without any difficulties in 80 hours 45 minutes. American crowds enthusiastically celebrated the arrival, and President

Under these circumstances, Eckener managed to obtain an order for the next American dirigible. Germany had to pay for this airship itself, as the cost was set against the war reparation accounts, but for the Zeppelin company this was unimportant. LZ 126 made its first flight on 27 August 1924.

On 12 October at 07:30 local time the Zeppelin took off for the US under the command of Hugo Eckener. The ship completed its voyage without any difficulties in 80 hours 45 minutes. American crowds enthusiastically celebrated the arrival, and President

In August 1929, ''Graf Zeppelin'' departed for another daring enterprise: a

In August 1929, ''Graf Zeppelin'' departed for another daring enterprise: a  In the following year, ''Graf Zeppelin'' undertook trips around Europe, and following a successful tour to

In the following year, ''Graf Zeppelin'' undertook trips around Europe, and following a successful tour to

The coming to power of the

The coming to power of the  On 6 May 1937, while landing in Lakehurst after a transatlantic flight, the tail of the ship caught fire, and within seconds, the ''Hindenburg'' burst into flames, killing 35 of the 97 people on board and one member of the ground crew. The cause of the fire was never definitively determined. The investigation into the accident concluded that

On 6 May 1937, while landing in Lakehurst after a transatlantic flight, the tail of the ship caught fire, and within seconds, the ''Hindenburg'' burst into flames, killing 35 of the 97 people on board and one member of the ground crew. The cause of the fire was never definitively determined. The investigation into the accident concluded that

"Pinkner and Wyman: the Evil Geniuses behind ''Fringe''."

''Los Angeles Times,'' 20 May 2010. Retrieved: 17 June 2011. They are also seen in the alternate reality 1939 plot line in the film ''

Since the 1990s

Since the 1990s

"The Development of Material-Adapted Structural Form."

Part II: Appendices

'' THÈSE NO 2986. ''

''Count Zeppelin: The Man and His Work''. London: Massie, 1938 – (ASIN: B00085KPWK) ( extract pp. 155–157, 210–211). * * Liddell Hart, B. H. ''A History of the World War 1914–1918.'' London: Faber & Faber, 1934. * * Robinson, Douglas H. ''Giants in the Sky: History of the Rigid Airship.'' Henley-on-Thames, UK: Foulis, 1973. . * Robinson, Douglas H. ''The Zeppelin in Combat.'' Henley-on-Thames, UK: Foulis, 1971 (3rd ed.). . * * Schiller, Hans von. – ''The Zeppelin Book'', Lulu online publishing, 2017. * Stephenson, Charles. ''Zeppelins: German Airships, 1900–40.'' Oxford, UK: Osprey, 2004. . * Swinfield, J. ''Airship: Design, Development and Disaster''. London: Conway, 2012. * * Willmott, H.P. ''First World War''. London:

"Zeppelin Exhibition – An Online Exhibition About Zeppelins"

Post & Tele Museum, Denmark. *

How did London civilians respond to the German airship raids of 1915?

(archived 20 December 2008)

Airships.net – Illustrated history of passenger Zeppelins

* ttp://www.ezep.de/zpj/zpj.html Zeppelin Post Journal – Quarterly publication for Zeppelin mail and airship memorabiliabr>Zeppelin Luftschifftechnik GmbH – The original company, now developing the ''Zeppelin NT''Dark Autumn: The 1916 German Zeppelin OffensiveDie deütschen Luftstreitkräfte im Weltkriege edited by Georg Paul Neumann 1920 [German][Books google].

{{LZ Navbox Brands that became generic Vehicles introduced in 1900 Air freight Aviation in World War I 20th century in Germany 20th-century German aviation

rigid airship

A rigid airship is a type of airship (or dirigible) in which the Aerostat, envelope is supported by an internal framework rather than by being kept in shape by the pressure of the lifting gas within the envelope, as in blimps (also called pres ...

named after the German inventor Ferdinand von Zeppelin

Graf, Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin (; 8 July 1838 – 8 March 1917) was a General (Germany), German general and later inventor of the Zeppelin rigid airships. His name became synonymous with airships and dominated long-distance flight until the ...

() who pioneered rigid airship development at the beginning of the 20th century. Zeppelin's notions were first formulated in 1874Eckener 1938, pp. 155–157. and developed in detail in 1893.Dooley 2004, p. A.187. They were patented in Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

in 1895 and in the United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

in 1899. After the outstanding success of the Zeppelin design, the word ''zeppelin'' came to be commonly used to refer to all forms of rigid airship

An airship, dirigible balloon or dirigible is a type of aerostat (lighter-than-air) aircraft that can navigate through the air flying powered aircraft, under its own power. Aerostats use buoyancy from a lifting gas that is less dense than the ...

s. Zeppelins were first flown commercially in 1910 by Deutsche Luftschiffahrts-AG

DELAG, acronym for ''Deutsche Luftschiffahrts-Aktiengesellschaft'' (German for "German Airship Travel Corporation"), was the List of airlines by foundation, world's first airline to use an aircraft in revenue service. It operated a fleet of zepp ...

(DELAG), the world's first airline in revenue service. By mid-1914, DELAG had carried over 10,000 fare-paying passengers on over 1,500 flights. During World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, the German military made extensive use of Zeppelins as bombers and as scouts. Numerous bombing raids on Britain

Britain most often refers to:

* Great Britain, a large island comprising the countries of England, Scotland and Wales

* The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, a sovereign state in Europe comprising Great Britain and the north-eas ...

resulted in over 500 deaths.

The defeat of Germany in 1918 temporarily slowed the airship business. Although DELAG established a scheduled daily service between Berlin

Berlin ( ; ) is the Capital of Germany, capital and largest city of Germany, by both area and List of cities in Germany by population, population. With 3.7 million inhabitants, it has the List of cities in the European Union by population withi ...

, Munich

Munich is the capital and most populous city of Bavaria, Germany. As of 30 November 2024, its population was 1,604,384, making it the third-largest city in Germany after Berlin and Hamburg. Munich is the largest city in Germany that is no ...

, and Friedrichshafen

Friedrichshafen ( or ; Low Alemannic: ''Hafe'' or ''Fridrichshafe'') is a city on the northern shoreline of Lake Constance (the ''Bodensee'') in Southern Germany, near the borders of both Switzerland and Austria. It is the district capital (''K ...

in 1919, the airships built for that service eventually had to be surrendered under the terms of the Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles was a peace treaty signed on 28 June 1919. As the most important treaty of World War I, it ended the state of war between Germany and most of the Allies of World War I, Allied Powers. It was signed in the Palace ...

, which also prohibited Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

from building large airships. An exception was made to allow the construction of one airship for the United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the naval warfare, maritime military branch, service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is the world's most powerful navy with the largest Displacement (ship), displacement, at 4.5 millio ...

, the order for which saved the company from extinction.

In 1926, the restrictions on airship construction were lifted and, with the aid of donations from the public, work began on the construction of LZ 127 ''Graf Zeppelin''. That revived the company's fortunes and, during the 1930s, the airships '' Graf Zeppelin'', and the even larger LZ 129 ''Hindenburg'' operated regular transatlantic flight

A transatlantic flight is the flight of an aircraft across the Atlantic Ocean from Europe, Africa, South Asia, or the Middle East to North America, South America, or ''vice versa''. Such flights have been made by fixed-wing aircraft, airships, bal ...

s from Germany to North America and Brazil. The spire of the Empire State Building was originally designed to serve as a mooring mast for Zeppelins and other airships, although it was found that high winds made that impossible and the plan was abandoned. The ''Hindenburg'' disaster in 1937, along with political and economic developments in Germany in the lead-up to World War II, hastened the demise of airships.

Principal characteristics

non-rigid airship

A non-rigid airship, commonly called a blimp ( /blɪmp/), is an airship (dirigible) without an internal structural framework or a keel. Unlike semi-rigid and rigid airships (e.g. Zeppelins), blimps rely on the pressure of their lifting gas (us ...

s, which relied on the inflation of a single-pressure envelope to maintain their shape. The framework of most Zeppelins was made of duralumin

Duralumin (also called duraluminum, duraluminium, duralum, dural(l)ium, or dural) is a trade name for one of the earliest types of age hardening, age-hardenable aluminium–copper alloys. The term is a combination of ''Düren'' and ''aluminium'' ...

, a combination of aluminium

Aluminium (or aluminum in North American English) is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol Al and atomic number 13. It has a density lower than that of other common metals, about one-third that of steel. Aluminium has ...

, copper

Copper is a chemical element; it has symbol Cu (from Latin ) and atomic number 29. It is a soft, malleable, and ductile metal with very high thermal and electrical conductivity. A freshly exposed surface of pure copper has a pinkish-orang ...

, and two or three other metals, the exact composition of which was kept secret for years. Early Zeppelins used rubberized cotton for the gasbags, but most later craft used goldbeater's skin made from cattle gut.

The first Zeppelins had long cylindrical hulls with tapered ends and complex multi-plane fin

A fin is a thin component or appendage attached to a larger body or structure. Fins typically function as foils that produce lift or thrust, or provide the ability to steer or stabilize motion while traveling in water, air, or other fluids. F ...

s. During World War I, following the lead of the rival firm Schütte-Lanz Luftschiffbau, almost all later airships changed to the more familiar streamlined shape with cruciform

A cruciform is a physical manifestation resembling a common cross or Christian cross. These include architectural shapes, biology, art, and design.

Cruciform architectural plan

Christian churches are commonly described as having a cruciform ...

tail fins.

Zeppelins were propelled by several internal combustion engines

An engine or motor is a machine designed to convert one or more forms of energy into mechanical energy.

Available energy sources include potential energy (e.g. energy of the Earth's gravitational field as exploited in hydroelectric power gen ...

, mounted in gondolas

The gondola (, ; , ) is a traditional, flat-bottomed Venetian rowing boat, well suited to the conditions of the Venetian lagoon. It is typically propelled by a gondolier, who uses a rowing oar, which is not fastened to the hull, in a sculli ...

or engine cars attached outside the structural framework. Some of these could provide reverse thrust for manoeuvring while mooring.

Early models had a fairly small externally-mounted gondola for passengers and crew beneath the frame. This space was never heated, because fire outside of the kitchen was considered too risky, and during trips across the North Atlantic or Siberia passengers were forced to bundle in blankets and furs to keep warm and were often miserably cold.

By the time of the '' Hindenburg'' several important changes had made traveling much more comfortable: the passenger space had been relocated to the interior of the framework, passenger rooms were insulated from the exterior by the dining area, and forced-warm air could be circulated from the water that cooled the forward engines. The new design did prevent passengers from enjoying the views from the windows of their berths, which had been a major attraction on the ''Graf Zeppelin''. On both the older and newer vessels, the external viewing windows were often open during flight. The flight altitude was so low that no pressurization of the cabins was necessary. The ''Hindenburg'' did maintain a pressurized air-locked smoking room: no flame was allowed, but a single electric lighter was provided, which could not be removed from the room.

Access to Zeppelins was achieved in a number of ways. The ''Graf Zeppelin''s gondola was accessed while the vessel was on the ground, via gangways. The ''Hindenburg'' also had passenger gangways leading from the ground directly into its hull which could be withdrawn entirely, ground access to the gondola, and an exterior access hatch via its electrical room; this latter was intended for crew use only.

On some long-distance zeppelins, engines were powered by a special Blau gas produced by the Zeppelin facility in Friedrichshafen. The combustible Blau gas was formulated to make its weight near that of air, so that its storage and consumption had little effect on the zeppelin's buoyancy

Buoyancy (), or upthrust, is the force exerted by a fluid opposing the weight of a partially or fully immersed object (which may be also be a parcel of fluid). In a column of fluid, pressure increases with depth as a result of the weight of t ...

. Blau gas was used on the first zeppelin voyage to America, starting in 1929.

History

Early designs

CountFerdinand von Zeppelin

Graf, Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin (; 8 July 1838 – 8 March 1917) was a General (Germany), German general and later inventor of the Zeppelin rigid airships. His name became synonymous with airships and dominated long-distance flight until the ...

's interest in airship development began in 1874, when he was inspired by a lecture given by Heinrich von Stephan

Ernst Heinrich Wilhelm von Stephan (born Heinrich Stephan, January 7, 1831 – April 8, 1897) was a general post director for the German Empire who reorganized the German postal service. He was integral in the founding of the Universal Posta ...

on the subject of "World Postal Services and Air Travel" to outline the basic principle of his later craft in a diary entry dated 25 March 1874.Dooley 2004, p. A.183. It describes a large rigidly framed outer envelope

An envelope is a common packaging item, usually made of thin, flat material. It is designed to contain a flat object, such as a letter (message), letter or Greeting card, card.

Traditional envelopes are made from sheets of paper cut to one o ...

containing several separate gasbags. He had previously encountered Union Army balloons in 1863 when he visited the United States as a military observer during the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and the Confederate States of A ...

.

Count Zeppelin began to seriously pursue his project after his early retirement from the army in 1890 at the age of 52. Convinced of the potential importance of aviation, he started working on various designs in 1891, and had completed detailed designs by 1893. An official committee reviewed his plans in 1894, and he received a patent, granted on 31 August 1895, with Theodor Kober producing the technical drawings.Dooley 2004, p. A.190.

Zeppelin's patent described a ' ("Steerable aircraft with several carrier bodies arranged one behind another"), an airship consisting of flexibly articulated rigid sections. The front section, containing the crew and engines, was long with a gas capacity of . The middle section was long with an intended useful load of and the rear section long with an intended load of .

Count Zeppelin's attempts to secure government funding for his project proved unsuccessful, but a lecture given to the Union of German Engineers gained their support. Zeppelin also sought support from the industrialist Carl Berg, then engaged in construction work on the second airship design of David Schwarz. Berg was under contract not to supply aluminium to any other airship manufacturer, and subsequently made a payment to Schwarz's widow as compensation for breaking this agreement.Dooley 2004, p. A.193.

Schwarz's design differed fundamentally from Zeppelin's, crucially lacking the use of separate gasbags inside a rigid envelope.Dooley 2004, p. A.191.

In 1898, Count Zeppelin founded the ''Gesellschaft zur Förderung der Luftschiffahrt'' (Society for the Promotion of Airship Flight), contributing more than half of its 800,000

In 1898, Count Zeppelin founded the ''Gesellschaft zur Förderung der Luftschiffahrt'' (Society for the Promotion of Airship Flight), contributing more than half of its 800,000 mark

Mark may refer to:

In the Bible

* Mark the Evangelist (5–68), traditionally ascribed author of the Gospel of Mark

* Gospel of Mark, one of the four canonical gospels and one of the three synoptic gospels

Currencies

* Mark (currency), a currenc ...

share-capital himself. Responsibility for the detail design was given to Kober, whose place was later taken by Ludwig Dürr

Ludwig Ferdinand Dürr (4 June 1878 in Stuttgart – 1 January 1956 in Friedrichshafen) was a German airship designer.

Life and career

After completing training as a mechanic, Dürr continued his training at the Königliche Baugewerkschule (Ro ...

, and construction of the first airship began in 1899 in a floating assembly-hall or hangar in the Bay of Manzell near Friedrichshafen

Friedrichshafen ( or ; Low Alemannic: ''Hafe'' or ''Fridrichshafe'') is a city on the northern shoreline of Lake Constance (the ''Bodensee'') in Southern Germany, near the borders of both Switzerland and Austria. It is the district capital (''K ...

on Lake Constance

Lake Constance (, ) refers to three bodies of water on the Rhine at the northern foot of the Alps: Upper Lake Constance (''Obersee''), Lower Lake Constance (''Untersee''), and a connecting stretch of the Rhine, called the Seerhein (). These ...

(the ''Bodensee''). The intention behind the floating hall was to facilitate the difficult task of bringing the airship out of the hall, as it could easily be aligned with the wind. The LZ 1 (LZ for ''Luftschiff Zeppelin'', or "Zeppelin Airship") was long with a hydrogen capacity of , was driven by two Daimler engines each driving a pair of propellers mounted either side of the envelope via bevel gear

Bevel gears are gears where the axes of the two shafts intersect and the tooth-bearing faces of the gears themselves are conically shaped. Bevel gears are most often mounted on shafts that are 90 degrees apart, but can be designed to work at ot ...

s and a driveshaft, and was controlled in pitch by moving a weight between its two nacelle

A nacelle ( ) is a streamlined container for aircraft parts such as Aircraft engine, engines, fuel or equipment. When attached entirely outside the airframe, it is sometimes called a pod, in which case it is attached with a Hardpoint#Pylon, pylo ...

s.

The first flight took place over Lake Constance on 2 July 1900. Dooley 2004, pp. A.197–A.198. Damaged during landing, it was repaired and modified and proved its potential in two subsequent flights made on 17 and 24 October 1900, bettering the 6 m/s ( ) velocity attained by the French airship ''La France''. Despite this performance, the shareholder

A shareholder (in the United States often referred to as stockholder) of corporate stock refers to an individual or legal entity (such as another corporation, a body politic, a trust or partnership) that is registered by the corporation as the ...

s declined to invest more money, and so the company was liquidated, with Count von Zeppelin purchasing the ship and equipment. The Count wished to continue experimenting, but he eventually dismantled the ship in 1901.de Syon 2001, p. 25.

Donations, the profits of a special lottery

A lottery (or lotto) is a form of gambling that involves the drawing of numbers at random for a prize. Some governments outlaw lotteries, while others endorse it to the extent of organizing a national or state lottery. It is common to find som ...

, some public funding, a mortgage of Count von Zeppelin's wife's estate, and a 100,000 mark contribution by Count von Zeppelin himself allowed the construction of LZ 2, which made only a single flight on 17 January 1906.de Syon 2001, p. 26. After both engines failed it made a forced landing in the Allgäu

The Allgäu (Standard ) is a region in Swabia in southern Germany. It covers the south of Bavarian Swabia, southeastern Baden-Württemberg, and parts of Austria. The region stretches from the pre-alpine lands up to the Alps. The main rivers flo ...

mountains, where a storm subsequently damaged the anchored ship beyond repair.

Incorporating all the usable parts of LZ 2, its successor LZ 3 became the first truly successful Zeppelin. This renewed the interest of the German military, but a condition of purchase of an airship was a 24-hour endurance trial.de Syon 2001, p. 35. This was beyond the capabilities of LZ 3, leading Zeppelin to construct his fourth design, the LZ 4, first flown on 20 June 1908. On 1 July it was flown over Switzerland to Zürich and then back to Lake Constance, covering and reaching an altitude of . An attempt to complete the 24-hour trial flight ended when LZ 4 had to make a landing at Echterdingen near Stuttgart

Stuttgart (; ; Swabian German, Swabian: ; Alemannic German, Alemannic: ; Italian language, Italian: ; ) is the capital city, capital and List of cities in Baden-Württemberg by population, largest city of the States of Germany, German state of ...

because of mechanical problems. During the stop, a storm tore the airship away from its moorings on the afternoon of 5 August 1908. It crashed into a tree, caught fire, and quickly burnt out. No one was seriously injured.

This accident would have finished Zeppelin's experiments, but his flights had generated huge public interest and a sense of national pride regarding his work, and spontaneous donations from the public began pouring in, eventually totalling over six million marks. This enabled the Count to found the '' Luftschiffbau Zeppelin GmbH'' (Airship Construction Zeppelin Ltd.) and the Zeppelin Foundation.

This accident would have finished Zeppelin's experiments, but his flights had generated huge public interest and a sense of national pride regarding his work, and spontaneous donations from the public began pouring in, eventually totalling over six million marks. This enabled the Count to found the '' Luftschiffbau Zeppelin GmbH'' (Airship Construction Zeppelin Ltd.) and the Zeppelin Foundation.

Before World War I

Before World War I (1914–1918) the Zeppelin company manufactured 21 more airships. The

Before World War I (1914–1918) the Zeppelin company manufactured 21 more airships. The Imperial German Army

The Imperial German Army (1871–1919), officially referred to as the German Army (), was the unified ground and air force of the German Empire. It was established in 1871 with the political unification of Germany under the leadership of Kingdom o ...

bought LZ 3 and LZ 5 (a sister-ship to LZ 4 which was completed in May 1909) and designated them Z I and Z II respectively. Z II was wrecked in a gale in April 1910, while Z I flew until 1913, when it was decommissioned and replaced by LZ 15, designated ''ersatz'' Z I. First flown on 16 January 1913, it was wrecked on 19 March of the same year. In April 1913 its newly built sister-ship LZ 15 (Z IV) accidentally intruded into French airspace owing to a navigational error caused by high winds and poor visibility. The commander judged it proper to land the airship to demonstrate that the incursion was accidental, and brought the ship down on the military parade-ground at Lunéville

Lunéville ( ; German : ''Lünstadt'' ; Lorrain: ''Leneinvile'') is a commune in the northeastern French department of Meurthe-et-Moselle.

It is a subprefecture of the department and lies on the river Meurthe at its confluence with the Ve ...

. The airship remained on the ground until the following day, permitting a detailed examination by French airship experts.

In 1909, Count Zeppelin founded the world's first airline, the Deutsche Luftschiffahrts-Aktiengesellschaft (German Airship Travel Corporation), generally known as DELAG

DELAG, acronym for ''Deutsche Luftschiffahrts-Aktiengesellschaft'' (German for "German Airship Travel Corporation"), was the world's first airline to use an aircraft in revenue service. It operated a fleet of zeppelin rigid airships manufacture ...

Robinson 1971, p. 15 to promote his airships, initially using LZ 6, which he had hoped to sell to the German Army. Notable aviation figures like Orville Wright

The Wright brothers, Orville Wright (August 19, 1871 – January 30, 1948) and Wilbur Wright (April 16, 1867 – May 30, 1912), were American aviation pioneers generally credited with inventing, building, and flying the world's first succes ...

offered critical perspectives on the Zeppelin; in a September 1909 New York Times interview, Wright compared airships to steam engines nearing their developmental peak, while seeing airplanes as akin to gas engines with untapped potential for innovation.The airships did not provide a scheduled service between cities, but generally operated pleasure cruises, carrying twenty passengers. The airships were given names in addition to their production numbers. LZ 6 first flew on 25 August 1909 and was accidentally destroyed in Baden-Oos on 14 September 1910 by a fire in its hangar.

The second DELAG airship, LZ 7 ''Deutschland'', made its maiden voyage on 19 June 1910. On 28 June it set off on a voyage to publicise Zeppelins, carrying 19 journalists as passengers. A combination of adverse weather and engine failure brought it down at Mount Limberg near Bad Iburg

Bad Iburg (; Westphalian: ''Bad Ibig'') is a spa town in the district of Osnabrück, in Lower Saxony, Germany. It is situated in the Teutoburg Forest, 16 km south of Osnabrück, and the Hermannsweg long-distance hiking trail passes throug ...

in Lower Saxony, its hull getting stuck in trees. All passengers and crew were unhurt, except for one crew member who broke his leg when he jumped from the craft. It was replaced by LZ 8 ''Deutschland II'', which also had a short career, first flying on 30 March 1911 and becoming damaged beyond repair when caught by a strong cross-wind while being walked out of its shed on 16 May. The company's fortunes changed with the next ship, LZ 10 ''Schwaben'', which first flew on 26 June 1911 and carried 1,553 passengers in 218 flights before catching fire after a gust tore it from its mooring near Düsseldorf. Other DELAG ships included LZ 11 ''Viktoria Luise'' (1912), LZ 13 ''Hansa'' (1912) and LZ 17 ''Sachsen'' (1913). By the outbreak of World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

in August 1914, 1588 flights had carried 10,197 fare-paying passengers.

On 24 April 1912, the

On 24 April 1912, the Imperial German Navy

The Imperial German Navy or the ''Kaiserliche Marine'' (Imperial Navy) was the navy of the German Empire, which existed between 1871 and 1919. It grew out of the small Prussian Navy (from 1867 the North German Federal Navy), which was mainly for ...

ordered its first Zeppelin—an enlarged version of the airships operated by DELAG—which received the naval designation Z 1 and entered Navy service in October 1912. On 18 January 1913 Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz

Alfred Peter Friedrich von Tirpitz (; born Alfred Peter Friedrich Tirpitz; 19 March 1849 – 6 March 1930) was a German grand admiral and State Secretary of the German Imperial Naval Office, the powerful administrative branch of the German Imperi ...

, Secretary of State of the German Imperial Naval Office, obtained the agreement of Kaiser Wilhelm II

Wilhelm II (Friedrich Wilhelm Viktor Albert; 27 January 18594 June 1941) was the last German Emperor and King of Prussia from 1888 until his abdication in 1918, which marked the end of the German Empire as well as the Hohenzollern dynasty ...

to a five-year program of expansion of German naval-airship strength, involving the building of two airship bases and constructing a fleet of ten airships. The first airship of the program, L 2, was ordered on 30 January. L 1 was lost on 9 September near Heligoland

Heligoland (; , ; Heligolandic Frisian: , , Mooring Frisian: , ) is a small archipelago in the North Sea. The islands were historically possessions of Denmark, then became possessions of the United Kingdom from 1807 to 1890. Since 1890, the ...

when caught in a storm while taking part in an exercise with the German fleet. 14 crew members drowned, the first fatalities in a Zeppelin accident.Robinson 1971, p. 25 Less than six weeks later, on 17 October, LZ 18 (L 2) caught fire during its acceptance trials, killing the entire crew. These accidents deprived the Navy of most of its experienced personnel: the head of the Admiralty Air Department was killed in the L 1 and his successor died in the L 2. The Navy was left with three partially trained crews. The next Navy zeppelin, the M class L 3, did not enter service until May 1914: in the meantime, ''Sachsen'' was hired from DELAG as a training ship.

By the outbreak of war in August 1914, Zeppelin had started constructing the first M class airships, which had a length of , with a volume of and a useful load of . Their three Maybach C-X engines produced each, and they could reach speeds of up to .

During World War I

During World War I, Germany’s airships were operated separately by the Army and the Navy. At the war’s outset, the Army assumed control of the three remaining DELAG airships, having already decommissioned three older Zeppelins, including Z I. Throughout the war, the Navy primarily used its Zeppelins for reconnaissance missions.Boyne 2002p. 256.

/ref> Although Zeppelin bombing raids, especially those aimed at London, captivated the German public’s imagination, they had limited material success. Nevertheless, these raids—along with later bombing raids by airplanes—led to the diversion of men and resources from the Western Front. Additionally, the fear of these attacks impacted industrial production to some extent. Early offensive operations by Army airships quickly revealed their extreme vulnerability to ground fire when flown at low altitudes, leading to the loss of several airships. Since no dedicated bombs had been developed at the time, these early raids dropped artillery shells instead. * On August 5, 1914, the airship Z VI bombed

Liège

Liège ( ; ; ; ; ) is a City status in Belgium, city and Municipalities in Belgium, municipality of Wallonia, and the capital of the Liège Province, province of Liège, Belgium. The city is situated in the valley of the Meuse, in the east o ...

. Due to cloud cover, it had to fly at a relatively low altitude, making it susceptible to small-arms fire; the damage led to a forced landing near Bonn, where the airship was destroyed. Thirteen bombs were dropped during the raid, resulting in the deaths of nine civilians.Robinson 1973, pp.86-7

* On August 21, airships Z VII and Z VIII were damaged by ground fire while supporting German Army operations in Alsace, with Z VIII ultimately lost. During the night of August 24-25, Z IX bombed Antwerp

Antwerp (; ; ) is a City status in Belgium, city and a Municipalities of Belgium, municipality in the Flemish Region of Belgium. It is the capital and largest city of Antwerp Province, and the third-largest city in Belgium by area at , after ...

, striking near the royal palace and killing five people. Less effective raids followed on the nights of September 1-2 and October 7. However, on October 8, Z IX was destroyed in its hangar at Düsseldorf by Flight Lieutenant Reginald Marix of the Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS). The RNAS had previously bombed Zeppelin bases in Cologne on September 22, 1914.

* On the Eastern Front, airship Z V was brought down by ground fire on August 28 during the Battle of Tannenberg

The Battle of Tannenberg, also known as the Second Battle of Tannenberg, was fought between Russia and Germany between 23 and 30 August 1914, the first month of World War I. The battle resulted in the almost complete destruction of the Russ ...

, with most of its crew captured. Z IV bombed Warsaw

Warsaw, officially the Capital City of Warsaw, is the capital and List of cities and towns in Poland, largest city of Poland. The metropolis stands on the Vistula, River Vistula in east-central Poland. Its population is officially estimated at ...

on September 24 and was also used to support German Army operations in East Prussia.Robinson 1973, p.85 By the end of 1914, the Army’s airship fleet had been reduced to four.

On 20 March 1915, temporarily forbidden from bombing London by the Kaiser, Z X (LZ 29), LZ 35 and the Schütte-Lanz airship SL 2 set off to bomb Paris

Paris () is the Capital city, capital and List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, largest city of France. With an estimated population of 2,048,472 residents in January 2025 in an area of more than , Paris is the List of ci ...

: SL 2 was damaged by artillery fire while crossing the front and turned back but the two Zeppelins reached Paris and dropped of bombs, killing only one and wounding eight. On the return journey Z X was damaged by anti-aircraft fire and was damaged beyond repair in the resulting forced landing. Three weeks later LZ 35 suffered a similar fate after bombing Poperinghe

Poperinge (; , ; ) is a City status in Belgium, city and Municipalities of Belgium, municipality located in the Belgium, Belgian province of West Flanders, Flemish Region, and has a history going back to medieval times. The municipality comprises ...

.

Paris mounted a more effective defense against zeppelin raids than London. Zeppelins attacking Paris had to first fly over the system of forts between the front and the city, from which they were subjected to anti-aircraft fire with reduced risk of collateral damage

"Collateral damage" is a term for any incidental and undesired death, injury or other damage inflicted, especially on civilians, as the result of an activity. Originally coined to describe military operations, it is now also used in non-milit ...

. The French also maintained a continuous patrol of two fighters over Paris at an altitude from which they could promptly attack arriving zeppelins avoiding the delay required to reach the zeppelin altitude. Two further missions were flown against Paris in January 1916: on 29 January LZ 79 killed 23 and injured another 30 but was so severely damaged by anti-aircraft fire that it crashed during the return journey. A second mission by LZ 77 the following night bombed the suburbs of Asnières and Versailles, with little effect.Robinson 1973, p. 113

Airship operations in the Balkans started in the autumn of 1915, and an airship base was constructed at Szentandras. In November 1915, LZ 81 was used to fly diplomats to Sofia

Sofia is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Bulgaria, largest city of Bulgaria. It is situated in the Sofia Valley at the foot of the Vitosha mountain, in the western part of the country. The city is built west of the Is ...

for negotiations with the Bulgaria

Bulgaria, officially the Republic of Bulgaria, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern portion of the Balkans directly south of the Danube river and west of the Black Sea. Bulgaria is bordered by Greece and Turkey t ...

n government. This base was also used by LZ 85 to conduct two raids on Salonika

Thessaloniki (; ), also known as Thessalonica (), Saloniki, Salonika, or Salonica (), is the second-largest city in Greece (with slightly over one million inhabitants in its Thessaloniki metropolitan area, metropolitan area) and the capital cit ...

in early 1916: a third raid on 4 May ended with it being brought down by anti-aircraft fire. The crew survived but were taken prisoner. When Romania

Romania is a country located at the crossroads of Central Europe, Central, Eastern Europe, Eastern and Southeast Europe. It borders Ukraine to the north and east, Hungary to the west, Serbia to the southwest, Bulgaria to the south, Moldova to ...

entered the war in August 1916, LZ 101 was transferred to Yambol

Yambol ( ) is a city in Southeastern Bulgaria and administrative centre of Yambol Province. It lies on both banks of the Tundzha river in the historical region of Thrace. It is occasionally spelled ''Jambol''.

Yambol is the administrative cente ...

and bombed Bucharest

Bucharest ( , ; ) is the capital and largest city of Romania. The metropolis stands on the River Dâmbovița (river), Dâmbovița in south-eastern Romania. Its population is officially estimated at 1.76 million residents within a greater Buc ...

on 28 August, 4 September and 25 September. LZ 86 transferred to Szentandras and made a single attack on the Ploiești

Ploiești ( , , ), formerly spelled Ploești, is a Municipiu, city and county seat in Prahova County, Romania. Part of the historical region of Muntenia, it is located north of Bucharest.

The area of Ploiești is around , and it borders the Ble ...

oil fields on 4 September but was wrecked on attempting to land after the mission. Its replacement, LZ 86, was damaged by anti-aircraft fire during its second attack on Bucharest on 26 September and was damaged beyond repair in the resulting forced landing, and was replaced by LZ 97.

Saint Petersburg

Saint Petersburg, formerly known as Petrograd and later Leningrad, is the List of cities and towns in Russia by population, second-largest city in Russia after Moscow. It is situated on the Neva, River Neva, at the head of the Gulf of Finland ...

in December 1916. Two Navy zeppelins were transferred to Wainoden on the Courland Peninsula

The Courland Peninsula (, German: ''Kurland''), also sometimes known as the Couronian Peninsula, is a distinct geographical, historical and cultural region in western Latvia. It represents the north-westernmost part of the broader region of Co ...

. A preliminary attempt to bomb Reval

Tallinn is the capital and most populous city of Estonia. Situated on a bay in north Estonia, on the shore of the Gulf of Finland of the Baltic Sea, it has a population of (as of 2025) and administratively lies in the Harju ''maakond'' (co ...

on 28 December ended in failure caused by operating problems due to the extreme cold, and one of the airships was destroyed in a forced landing at Seerappen. The plan was subsequently abandoned.

In 1917 the German High Command made an attempt to use a Zeppelin to deliver supplies to Lettow-Vorbeck's forces in German East Africa

German East Africa (GEA; ) was a German colonial empire, German colony in the African Great Lakes region, which included present-day Burundi, Rwanda, the Tanzania mainland, and the Kionga Triangle, a small region later incorporated into Portugu ...

. L 57, a specially lengthened craft was to have flown the mission but was destroyed shortly after completion. A Zeppelin then under construction, L 59, was then modified for the mission: it set off from Yambol on 21 November 1917 and nearly reached its destination, but was ordered to return by radio. Its journey covered and lasted 95 hours. It was then used for reconnaissance and bombing missions in the eastern Mediterranean. It flew one bombing mission against Naples

Naples ( ; ; ) is the Regions of Italy, regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 908,082 within the city's administrative limits as of 2025, while its Metropolitan City of N ...

on 10–11 March 1918. A planned attack on Suez

Suez (, , , ) is a Port#Seaport, seaport city with a population of about 800,000 in north-eastern Egypt, located on the north coast of the Gulf of Suez on the Red Sea, near the southern terminus of the Suez Canal. It is the capital and largest c ...

was turned back by high winds, and on 7 April 1918 it was on a mission to bomb the British naval base at Malta

Malta, officially the Republic of Malta, is an island country in Southern Europe located in the Mediterranean Sea, between Sicily and North Africa. It consists of an archipelago south of Italy, east of Tunisia, and north of Libya. The two ...

when it caught fire over the Straits of Otranto, with the loss of all its crew.

On 5 January 1918, a fire at Ahlhorn destroyed four of the specialised double sheds along with four Zeppelins and one Schütte-Lanz. In July 1918, the Tondern raid conducted by the RAF and Royal Navy, destroyed two Zeppelins in their sheds.

1914–1918 naval patrols

The main use of the airship was in reconnaissance over the

The main use of the airship was in reconnaissance over the North Sea

The North Sea lies between Great Britain, Denmark, Norway, Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium, and France. A sea on the European continental shelf, it connects to the Atlantic Ocean through the English Channel in the south and the Norwegian Se ...

and the Baltic

Baltic may refer to:

Peoples and languages

*Baltic languages, a subfamily of Indo-European languages, including Lithuanian, Latvian and extinct Old Prussian

*Balts (or Baltic peoples), ethnic groups speaking the Baltic languages and/or originatin ...

, and the majority of airships manufactured were used by the Navy. Patrolling had priority over any other airship activity. Lehmann Chapter VI During the war almost 1,000 missions were flown over the North Sea alone, compared with about 50 strategic bombing raids. The German Navy had some 15 Zeppelins in commission by the end of 1915 and was able to have two or more patrolling continuously at any one time. However, their operations were limited by weather conditions. On 16 February, L 3 and L 4 were lost owing to a combination of engine failure and high winds, L 3 crashing on the Danish island of Fanø

Fanø () is a Danish island in the North Sea off the coast of southwestern Denmark, and is the very northernmost of the Danish Wadden Sea Islands. Fanø Municipality () is the '' kommune'' that covers the island and its seat is the town of Nor ...

without loss of life and L 4 coming down at Blaavands Huk; eleven crew escaped from the forward gondola, after which the lightened airship with four crew members remaining in the aft engine car was blown out to sea and lost.

At this stage in the war there was no clear doctrine for the use of Naval airships. A single large Zeppelin, L 5, played an unimportant part in the Battle of the Dogger Bank on 24 January 1915. L 5 was carrying out a routine patrol when it picked up Admiral Hipper's radio signal announcing that he was engaged with the British battle cruiser squadron. Heading towards the German fleet's position, the Zeppelin was forced to climb above the cloud cover by fire from the British fleet: its commander then decided that it was his duty to cover the retreating German fleet rather than observe British movements.

In 1915, patrols were only carried out on 124 days and in other years the total was considerably less. They prevented British ships from approaching Germany, spotted when and where the British were laying mines and later aided in the destruction of those mines. Zeppelins would sometimes land on the sea next to a minesweeper, bring aboard an officer and show him the mines' locations.

In 1917, the Royal Navy began to take effective countermeasures against airship patrols over the North Sea. In April, the first Curtiss H.12 Large America long-range flying boats

A flying boat is a type of seaplane with a hull (watercraft), hull, allowing it to land on water. It differs from a floatplane in having a fuselage that is purpose-designed for flotation, while floatplanes rely on fuselage-mounted floats for b ...

were delivered to RNAS Felixstowe, and in July 1917, the aircraft carrier entered service and launching platforms for aeroplanes were fitted to the forward turrets of some light cruisers. On 14 May, L 22 was shot down near Terschelling Bank by an H.12 flown by Lt. Galpin and Sub-Lt. Leckie, which had been alerted following interception of its radio traffic. Two abortive interceptions were made by Galpin and Leckie on 24 May and 5 June. On 14 June, L 43 was brought down by an H.12 flown by Sub Lts. Hobbs and Dickie. On the same day Galpin and Leckie intercepted and attacked L 46. The Germans had believed that the previous unsuccessful attacks had been made by an aircraft operating from one of the Royal Navy's seaplane carriers; now realising that there was a new threat, Strasser ordered airships patrolling in the Terschilling area to maintain an altitude of at least , considerably reducing their effectiveness. On 21 August, L 23, patrolling off the Danish coast, was spotted by the British 3rd Light Cruiser squadron which was in the area. launched its Sopwith Pup

The Sopwith Pup is a British single-seater biplane fighter aircraft built by the Sopwith Aviation Company. It entered service with the Royal Naval Air Service and the Royal Flying Corps in the autumn of 1916. With pleasant flying characteristi ...

, and Sub-Lt. B. A. Smart succeeded in shooting the Zeppelin down in flames. The cause of the airship's loss was not discovered by the Germans, who believed the Zeppelin had been brought down by anti-aircraft fire from ships.

Bombing campaign against Britain

At the beginning of the conflict, the German command had high hopes for the airships, which were considerably more capable than contemporary light fixed-wing machines: they were almost as fast, could carry multiple machine guns, and had enormously greater

At the beginning of the conflict, the German command had high hopes for the airships, which were considerably more capable than contemporary light fixed-wing machines: they were almost as fast, could carry multiple machine guns, and had enormously greater bomb

A bomb is an explosive weapon that uses the exothermic reaction of an explosive material to provide an extremely sudden and violent release of energy. Detonations inflict damage principally through ground- and atmosphere-transmitted mechan ...

-load range and endurance. Contrary to expectation, it was not easy to ignite the hydrogen using standard bullets and shrapnel. The Allies only started to exploit the Zeppelin's great vulnerability to fire when a combination of Pomeroy and Brock explosive ammunition with Buckingham incendiary ammunition

Incendiary ammunition is a type of ammunition that contains a chemical that, upon hitting a hard obstacle, has the characteristic of causing fire/setting flammable materials in the vicinity of the impact on fire.

World War I

The first time ince ...

was used in fighter aircraft

Fighter aircraft (early on also ''pursuit aircraft'') are military aircraft designed primarily for air-to-air combat. In military conflict, the role of fighter aircraft is to establish air supremacy, air superiority of the battlespace. Domina ...

machine guns during 1916. The British had been concerned over the threat posed by Zeppelins since 1909, and attacked the Zeppelin bases early in the war. LZ 25 was destroyed in its hangar at Düsseldorf on 8 October 1914 by bombs dropped by Flt Lt Reginald Marix, RNAS, and the sheds at Cologne as well as the Zeppelin works in Friedrichshafen were also attacked. These raids were followed by the Cuxhaven Raid on Christmas Day 1914, one of the first operations carried out by ship-launched aeroplanes.

Airship raids on Great Britain were approved by the Kaiser

Kaiser ( ; ) is the title historically used by German and Austrian emperors. In German, the title in principle applies to rulers anywhere in the world above the rank of king (). In English, the word ''kaiser'' is mainly applied to the emperors ...

on 7 January 1915, although he excluded London as a target and further demanded that no attacks be made on historic buildings. The raids were intended to target only military sites on the east coast and around the Thames estuary, but bombing accuracy was poor owing to the height at which the airships flew and navigation was problematic. The airships relied largely on dead reckoning

In navigation, dead reckoning is the process of calculating the current position of a moving object by using a previously determined position, or fix, and incorporating estimates of speed, heading (or direction or course), and elapsed time. T ...

, supplemented by a radio direction-finding system of limited accuracy. After blackouts became widespread, many bombs fell at random on uninhabited countryside.

=1915

= The first on Britain took place on the night of 19–20 January 1915. Two Zeppelins, L 3 and L 4, intended to attack targets near the RiverHumber

The Humber is a large tidal estuary on the east coast of Northern England. It is formed at Trent Falls, Faxfleet, by the confluence of the tidal rivers River Ouse, Yorkshire, Ouse and River Trent, Trent. From there to the North Sea, it forms ...

but, diverted by strong winds, eventually dropped their bombs on Great Yarmouth

Great Yarmouth ( ), often called Yarmouth, is a seaside resort, seaside town which gives its name to the wider Borough of Great Yarmouth in Norfolk, England; it straddles the River Yare and is located east of Norwich. Its fishing industry, m ...

, Sheringham

Sheringham (; population 7,367) is a seaside town and civil parish in the county of Norfolk, England.Ordnance Survey (2002). ''OS Explorer Map 252 - Norfolk Coast East''. . The motto of the town, granted in 1953 to the Sheringham Urban District ...

, King's Lynn

King's Lynn, known until 1537 as Bishop's Lynn and colloquially as Lynn, is a port and market town in the borough of King's Lynn and West Norfolk in the county of Norfolk, England. It is north-east of Peterborough, north-north-east of Cambridg ...

and the surrounding villages, killing four and injuring 16. Material damage was estimated at £7,740.

The Kaiser authorised the bombing of the London docks on 12 February 1915, but no raids on London took place until May. Two Navy raids failed due to bad weather on 14 and 15 April, and it was decided to delay further attempts until the more capable P class Zeppelins were in service. The Army received the first of these, LZ 38, and Erich Linnarz commanded it on a raid over Ipswich

Ipswich () is a port town and Borough status in the United Kingdom, borough in Suffolk, England. It is the county town, and largest in Suffolk, followed by Lowestoft and Bury St Edmunds, and the third-largest population centre in East Anglia, ...

on 29–30 April and another, attacking Southend

Southend-on-Sea (), commonly referred to as Southend (), is a coastal city and unitary authorities of England, unitary authority area with Borough status in the United Kingdom, borough status in south-eastern Essex, England. It lies on the nor ...

on 9–10 May. LZ 38 also attacked Dover

Dover ( ) is a town and major ferry port in Kent, southeast England. It faces France across the Strait of Dover, the narrowest part of the English Channel at from Cap Gris Nez in France. It lies southeast of Canterbury and east of Maidstone. ...

and Ramsgate

Ramsgate is a seaside resort, seaside town and civil parish in the district of Thanet District, Thanet in eastern Kent, England. It was one of the great English seaside towns of the 19th century. In 2021 it had a population of 42,027. Ramsgate' ...

on 16–17 May, before returning to bomb Southend on 26–27 May. These four raids killed six people and injured six, causing property damage estimated at £16,898.Cole and Cheesman 1984, pp. 51–55. Twice Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS) aircraft tried to intercept LZ 38 but on both occasions it was either able to outclimb the aircraft or was already at too great an altitude for the aircraft to intercept.

On 31 May Linnarz commanded LZ 38 on the first raid against London. In total some 120 bombs were dropped on a line stretching from Stoke Newington

Stoke Newington is an area in the northwest part of the London Borough of Hackney, England. The area is northeast of Charing Cross. The Manor of Stoke Newington gave its name to Stoke Newington (parish), Stoke Newington, the ancient parish. S ...

south to Stepney

Stepney is an area in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets in the East End of London. Stepney is no longer officially defined, and is usually used to refer to a relatively small area. However, for much of its history the place name was applied to ...

and then north toward Leytonstone

Leytonstone ( ) is an area in East London, England, within the London Borough of Waltham Forest. It adjoins Wanstead to the north-east, Forest Gate to the south-east, Stratford to the south-west, Leyton to the west, and Walthamstow to the nor ...

. Seven people were killed and 35 injured. 41 fires were started, burning out seven buildings and the total damage was assessed at £18,596. Aware of the problems that the Germans were experiencing in navigation, this raid caused the government to issue a D notice prohibiting the press from reporting anything about raids that was not mentioned in official statements. Only one of the 15 defensive sorties managed to make visual contact with the enemy, and one of the pilots, Flt Lieut D. M. Barnes, was killed on attempting to land.

The first naval attempt on London took place on 4 June: strong winds caused the commander of L 9 to misjudge his position, and the bombs were dropped on Gravesend

Gravesend is a town in northwest Kent, England, situated 21 miles (35 km) east-southeast of Charing Cross (central London) on the Bank (geography), south bank of the River Thames, opposite Tilbury in Essex. Located in the diocese of Roche ...

. L 9 was also diverted by the weather on 6–7 June, attacking Hull

Hull may refer to:

Structures

* The hull of an armored fighting vehicle, housing the chassis

* Fuselage, of an aircraft

* Hull (botany), the outer covering of seeds

* Hull (watercraft), the body or frame of a sea-going craft

* Submarine hull

Ma ...

instead of London and causing considerable damage. On the same night an Army raid of three Zeppelins also failed because of the weather, and as the airships returned to Evere (Brussels) they ran into a counter-raid by RNAS aircraft flying from Furnes, Belgium

Belgium, officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. Situated in a coastal lowland region known as the Low Countries, it is bordered by the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Luxembourg to the southeas ...

. LZ 38 was destroyed on the ground and LZ 37 was intercepted in the air by R. A. J. Warneford, who dropped six bombs on the airship, setting it on fire. All but one of the crew died. Warneford was awarded the Victoria Cross

The Victoria Cross (VC) is the highest and most prestigious decoration of the Orders, decorations, and medals of the United Kingdom, British decorations system. It is awarded for valour "in the presence of the enemy" to members of the British ...

for his achievement. As a consequence of the RNAS raid both the Army and Navy withdrew from their bases in Belgium.

After an ineffective attack by L 10 on Tyneside

Tyneside is a List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, built-up area across the banks of the River Tyne, England, River Tyne in Northern England. The population of Tyneside as published in the United Kingdom Census 2011, 2011 census was 774,891 ...

on 15–16 June the short summer nights discouraged further raids for some months, and the remaining Army Zeppelins were reassigned to the Eastern and Balkan fronts. The Navy resumed raids on Britain in August, when three largely ineffective raids were carried out. On 10 August the antiaircraft guns had their first success, causing L 12 to come down into the sea off Zeebrugge

Zeebrugge (; from , meaning "Bruges-on-Sea"; , ) is a village on the coast of Belgium and a subdivision of Bruges, for which it is the modern port. Zeebrugge serves as both the international port of Bruges-Zeebrugge and a seafront resort with ...

, and on 17–18 August L 10 became the first Navy airship to reach London. Mistaking the reservoirs of the Lea Valley

The Lea Valley (also spelt Lee Valley), the valley of the River Lea, has been used as a transport corridor, a source of sand and gravel, an industrial area, a water supply for London, and a recreational area. The London 2012 Summer Olympics wer ...

for the Thames, it dropped its bombs on Walthamstow

Walthamstow ( or ) is a town within the London Borough of Waltham Forest in east London. The town borders Chingford to the north, Snaresbrook and South Woodford to the east, Leyton and Leytonstone to the south, and Tottenham to the west. At ...

and Leytonstone. L 10 was destroyed a little over two weeks later: it was struck by lightning and caught fire off Cuxhaven

Cuxhaven (; ) is a town and seat of the Cuxhaven district, in Lower Saxony, Germany. The town includes the northernmost point of Lower Saxony. It is situated on the shore of the North Sea at the mouth of the Elbe River. Cuxhaven has a footprint o ...

, and the entire crew was killed. Three Army airships set off to bomb London on 7–8 September, of which two succeeded: SL 2 dropped bombs between Southwark

Southwark ( ) is a district of Central London situated on the south bank of the River Thames, forming the north-western part of the wider modern London Borough of Southwark. The district, which is the oldest part of South London, developed ...

and Woolwich

Woolwich () is a town in South London, southeast London, England, within the Royal Borough of Greenwich.

The district's location on the River Thames led to its status as an important naval, military and industrial area; a role that was mainta ...

: LZ 74 scattered 39 bombs over Cheshunt

Cheshunt (/ˈtʃɛzənt/ CHEZ-ənt) is a town in the Borough of Broxbourne, Hertfordshire, England, situated within the London commuter belt approximately north of Central London. The town lies on the River Lea and Lee Navigation, bordering th ...

before heading on to London and dropping a single bomb on Fenchurch Street station.

The Navy attempted to follow up the Army's success the following night. One Zeppelin targeted the benzole plant at Skinningrove and three set off to bomb London: two were forced to turn back but L 13, commanded by ''Kapitänleutnant'' Heinrich Mathy reached London. The bomb-load included a bomb, the largest yet carried. This exploded near Smithfield Market

Smithfield, properly known as West Smithfield, is a district located in Central London, part of Farringdon Without, the most westerly Wards of the City of London, ward of the City of London, England.

Smithfield is home to a number of City in ...

, destroying several houses and killing two men. More bombs fell on the textile warehouses north of St Paul's Cathedral

St Paul's Cathedral, formally the Cathedral Church of St Paul the Apostle, is an Anglican cathedral in London, England, the seat of the Bishop of London. The cathedral serves as the mother church of the Diocese of London in the Church of Engl ...

, causing a fire which despite the attendance of 22 fire engines caused over half a million pounds of damage: Mathy then turned east, dropping his remaining bombs on Liverpool Street station

Liverpool Street station, also known as London Liverpool Street, is a major central London railway terminus and connected London Underground station in the north-eastern corner of the City of London, in the ward of Bishopsgate Without. It i ...

. The Zeppelin was the target of concentrated anti-aircraft fire, but no hits were scored and the falling shrapnel caused both damage and alarm on the ground. The raid killed 22 people and injured 87. The monetary cost of the damage was over one sixth of the total damage costs inflicted by bombing raids during the war.

After three more raids were scattered by the weather, a five-Zeppelin raid was launched by the Navy on 13 October, the "Theatreland Raid." Arriving over the Norfolk coast at around 18:30, the Zeppelins encountered new ground defences installed since the September raid; these had no success, although the airship commanders commented on the improved defences of the city. L 15 began bombing over Charing Cross

Charing Cross ( ) is a junction in Westminster, London, England, where six routes meet. Since the early 19th century, Charing Cross has been the notional "centre of London" and became the point from which distances from London are measured. ...

, the first bombs striking the Lyceum Theatre and the corner of Exeter and Wellington Streets, killing 17 and injuring 20. None of the other Zeppelins reached central London: bombs fell on Woolwich, Guildford

Guildford () is a town in west Surrey, England, around south-west of central London. As of the 2011 census, the town has a population of about 77,000 and is the seat of the wider Borough of Guildford, which had around inhabitants in . The nam ...

, Tonbridge

Tonbridge ( ) (historic spelling ''Tunbridge'') is a market town in Kent, England, on the River Medway, north of Royal Tunbridge Wells, south west of Maidstone and south east of London. In the administrative borough of Tonbridge and Mall ...

, Croydon

Croydon is a large town in South London, England, south of Charing Cross. Part of the London Borough of Croydon, a Districts of England, local government district of Greater London; it is one of the largest commercial districts in Greater Lond ...

, Hertford

Hertford ( ) is the county town of Hertfordshire, England, and is also a civil parish in the East Hertfordshire district of the county. The parish had a population of 26,783 at the 2011 census.

The town grew around a Ford (crossing), ford on ...

and an army camp near Folkestone. A total of 71 people were killed and 128 injured. This was the last raid of 1915, as bad weather coincided with the new moon in both November and December 1915 and continued into January 1916.

Although these raids had no significant military impact, the psychological effect was considerable. The writer D. H. Lawrence

David Herbert Lawrence (11 September 1885 – 2 March 1930) was an English novelist, short story writer, poet, playwright, literary critic, travel writer, essayist, and painter. His modernist works reflect on modernity, social alienation ...

described one raid in a letter to Lady Ottoline Morrell

Lady Ottoline Violet Anne Morrell (née Cavendish-Bentinck; 16 June 1873 – 21 April 1938) was an English Aristocracy (class), aristocrat and society hostess. Her patronage was influential in artistic and intellectual circles, where she befri ...

:

=1916

= The raids continued in 1916. In December 1915, additional P class Zeppelins and the first of the new Q class airships were delivered. The Q class was an enlargement of the P class with improved ceiling and bomb-load. The Army took full control of ground defences in February 1916, and a variety of sub 4-inch (less than 102 mm)calibre

In guns, particularly firearms, but not artillery, where a different definition may apply, caliber (or calibre; sometimes abbreviated as "cal") is the specified nominal internal diameter of the gun barrel bore – regardless of how or wher ...

guns were converted to anti-aircraft

Anti-aircraft warfare (AAW) is the counter to aerial warfare and includes "all measures designed to nullify or reduce the effectiveness of hostile air action".AAP-6 It encompasses surface-based, subsurface ( submarine-launched), and air-ba ...

use. Searchlight

A searchlight (or spotlight) is an apparatus that combines an extremely luminosity, bright source (traditionally a carbon arc lamp) with a mirrored parabolic reflector to project a powerful beam of light of approximately parallel rays in a part ...

s were introduced, initially manned by police. By mid-1916, there were 271 anti-aircraft guns and 258 searchlights across England. Aerial defences against Zeppelins were divided between the RNAS and the Royal Flying Corps

The Royal Flying Corps (RFC) was the air arm of the British Army before and during the First World War until it merged with the Royal Naval Air Service on 1 April 1918 to form the Royal Air Force. During the early part of the war, the RFC sup ...

(RFC), with the Navy engaging enemy airships approaching the coast while the RFC took responsibility once the enemy had crossed the coastline. Initially the War Office had believed that the Zeppelins used a layer of inert gas to protect themselves from incendiary bullets, and favoured the use of bombs or devices like the Ranken dart. However, by mid-1916 an effective mixture of explosive, tracer and incendiary rounds had been developed. There were 23 airship raids in 1916, in which 125 tons of bombs were dropped, killing 293 people and injuring 691.

The first raid of 1916 was carried out by the German Navy. Nine Zeppelins were sent to Liverpool on the night of 31 January – 1 February. A combination of poor weather and mechanical problems scattered them across the

The first raid of 1916 was carried out by the German Navy. Nine Zeppelins were sent to Liverpool on the night of 31 January – 1 February. A combination of poor weather and mechanical problems scattered them across the Midlands

The Midlands is the central region of England, to the south of Northern England, to the north of southern England, to the east of Wales, and to the west of the North Sea. The Midlands comprises the ceremonial counties of Derbyshire, Herefor ...

and several towns were bombed. A total of 61 people were reported killed and 101 injured by the raid."Damage in the Raid." ''The Times,'' 5 February 1916, p. 7. Despite ground fog, 22 aircraft took off to find the Zeppelins but none succeeded, and two pilots were killed when attempting to land. One airship, the L 19, came down in the North Sea because of engine failure and damage from Dutch ground-fire. Although the wreck stayed afloat for a while and was sighted by a British fishing trawler

A fishing trawler is a commercial fishing vessel designed to operate fishing trawls. Trawling is a method of fishing that involves actively dragging or pulling a trawl through the water behind one or more trawlers. Trawls are fishing nets tha ...

, the boat's crew refused to rescue the Zeppelin's crew because they were outnumbered, and all 16 crew died.

Further raids were delayed by an extended period of poor weather and also by the withdrawal of the majority of Naval Zeppelins in an attempt to resolve the recurrent engine failures. Three Zeppelins set off to bomb Rosyth

Rosyth () is a town and Garden City in Fife, Scotland, on the coast of the Firth of Forth.

Scotland's first Garden city movement, Garden City, Rosyth is part of the Greater Dunfermline Area and is located 3 miles south of Dunfermline city cen ...

on 5–6 March but were forced by high winds to divert to Hull, killing 18, injuring 52 and causing £25,005 damage. At the beginning of April raids were attempted on five successive nights. Ten airships set off on 31 March: most turned back and L 15, damaged by antiaircraft fire and an aircraft attacking using Ranken darts, came down in the sea near Margate. Most of the 48 killed in the raid were victims of a single bomb which fell on an Army billet in Cleethorpes

Cleethorpes () is a seaside town on the estuary of the Humber in North East Lincolnshire, Lincolnshire, England with a population of 29,678 in 2021. It has been permanently occupied since the 6th century, with fishing as its original industry ...

. The following night two Navy Zeppelins bombed targets in the north of England, killing 22 and injuring 130. On the night of 2/3 April a six-airship raid was made, targeting the naval base at Rosyth

Rosyth () is a town and Garden City in Fife, Scotland, on the coast of the Firth of Forth.

Scotland's first Garden city movement, Garden City, Rosyth is part of the Greater Dunfermline Area and is located 3 miles south of Dunfermline city cen ...

, the Forth Bridge

The Forth Bridge is a cantilever railway bridge across the Firth of Forth in the east of Scotland, west of central Edinburgh. Completed in 1890, it is considered a symbol of Scotland (having been voted Scotland's greatest man-made wonder in ...

and London. None of the airships bombed their intended targets; 13 were killed, 24 injured and much of the £77,113 damage was caused by the destruction of a warehouse in Leith

Leith (; ) is a port area in the north of Edinburgh, Scotland, founded at the mouth of the Water of Leith and is home to the Port of Leith.

The earliest surviving historical references are in the royal charter authorising the construction of ...

containing whisky. Raids on 4/5 April and 5/6 April had little effect, as did a five-Zeppelin raid on 25/6 April and a raid by a single Army Zeppelin the following night. On 2/3 July a nine-Zeppelin raid against Manchester and Rosyth was largely ineffective due to weather conditions, and one was forced to land in neutral Denmark, its crew being interned.

On 28–29 July, the first raid to include one of the new and much larger R-class Zeppelins, L 31, took place. The 10-Zeppelin raid achieved very little; four turned back early and the rest wandered over a fog-covered landscape before giving up. Adverse weather dispersed raids on 30–31 July and 2–3 August, and on 8–9 August nine airships attacked Hull with little effect. On 24–25 August 12 Navy Zeppelins were launched: eight turned back without attacking and only Heinrich Mathy's L 31 reached London; flying above low clouds, 36 bombs were dropped in 10 minutes on south east London. Nine people were killed, 40 injured and £130,203 of damage was caused.

Zeppelins were very difficult to attack successfully at high altitude, although this also made accurate bombing impossible. Aeroplanes struggled to reach a typical altitude of , and firing the solid bullets usually used by aircraft guns was ineffectual: they only made small holes causing inconsequential gas leaks. Britain developed new bullets, the Brock containing oxidant potassium chlorate

Potassium chlorate is the inorganic compound with the molecular formula KClO3. In its pure form, it is a white solid. After sodium chlorate, it is the second most common chlorate in industrial use. It is a strong oxidizing agent and its most impor ...

, and the Buckingham filled with phosphorus

Phosphorus is a chemical element; it has Chemical symbol, symbol P and atomic number 15. All elemental forms of phosphorus are highly Reactivity (chemistry), reactive and are therefore never found in nature. They can nevertheless be prepared ar ...

, which reacted with the chlorate to catch fire and hence ignite the Zeppelin's hydrogen. These had become available by September 1916.

The biggest raid to date was launched on 2–3 September, when twelve German Navy and four Army airships set out to bomb London. A combination of rain and snowstorms scattered the airships while they were still over the North Sea. Only one of the naval airships came within seven miles of central London, and both damage and casualties were slight. The newly commissioned Schütte-Lanz SL 11 dropped a few bombs on Hertfordshire