Weald on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Weald () is an area of

The Weald () is an area of

The Weald is the eroded remains of a geological structure, an

The Weald is the eroded remains of a geological structure, an

Prehistoric evidence suggests that, following the

Prehistoric evidence suggests that, following the

South East England

South East England is one of the nine official regions of England, regions of England that are in the ITL 1 statistical regions of England, top level category for Statistics, statistical purposes. It consists of the nine counties of england, ...

between the parallel chalk

Chalk is a soft, white, porous, sedimentary carbonate rock. It is a form of limestone composed of the mineral calcite and originally formed deep under the sea by the compression of microscopic plankton that had settled to the sea floor. Ch ...

escarpment

An escarpment is a steep slope or long cliff that forms as a result of faulting or erosion and separates two relatively level areas having different elevations.

Due to the similarity, the term '' scarp'' may mistakenly be incorrectly used inte ...

s of the North

North is one of the four compass points or cardinal directions. It is the opposite of south and is perpendicular to east and west. ''North'' is a noun, adjective, or adverb indicating Direction (geometry), direction or geography.

Etymology

T ...

and the South Downs

The South Downs are a range of chalk hills in the south-eastern coastal counties of England that extends for about across the south-eastern coastal counties of England from the Itchen valley of Hampshire in the west to Beachy Head, in the ...

. It crosses the counties of Hampshire

Hampshire (, ; abbreviated to Hants.) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South East England. It is bordered by Berkshire to the north, Surrey and West Sussex to the east, the Isle of Wight across the Solent to the south, ...

, Surrey

Surrey () is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South East England. It is bordered by Greater London to the northeast, Kent to the east, East Sussex, East and West Sussex to the south, and Hampshire and Berkshire to the wes ...

, West Sussex

West Sussex is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South East England. It is bordered by Surrey to the north, East Sussex to the east, the English Channel to the south, and Hampshire to the west. The largest settlement is Cr ...

, East Sussex

East Sussex is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South East England. It is bordered by Kent to the north-east, West Sussex to the west, Surrey to the north-west, and the English Channel to the south. The largest settlement ...

, and Kent

Kent is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South East England. It is bordered by Essex across the Thames Estuary to the north, the Strait of Dover to the south-east, East Sussex to the south-west, Surrey to the west, and Gr ...

. It has three parts, the sandstone

Sandstone is a Clastic rock#Sedimentary clastic rocks, clastic sedimentary rock composed mainly of grain size, sand-sized (0.0625 to 2 mm) silicate mineral, silicate grains, Cementation (geology), cemented together by another mineral. Sand ...

"High Weald" in the centre, the clay

Clay is a type of fine-grained natural soil material containing clay minerals (hydrous aluminium phyllosilicates, e.g. kaolinite, ). Most pure clay minerals are white or light-coloured, but natural clays show a variety of colours from impuriti ...

"Low Weald" periphery and the Greensand Ridge

The Greensand Ridge, also known as the Wealden Greensand, is an extensive, prominent, often wooded, mixed greensand/sandstone escarpment in south-east England. Forming part of the Weald, a former dense forest in Sussex, Surrey and Kent, it ...

, which stretches around the north and west of the Weald and includes its highest points. The Weald once was covered with forest and its name, Old English

Old English ( or , or ), or Anglo-Saxon, is the earliest recorded form of the English language, spoken in England and southern and eastern Scotland in the Early Middle Ages. It developed from the languages brought to Great Britain by Anglo-S ...

in origin, signifies "woodland

A woodland () is, in the broad sense, land covered with woody plants (trees and shrubs), or in a narrow sense, synonymous with wood (or in the U.S., the '' plurale tantum'' woods), a low-density forest forming open habitats with plenty of sunli ...

". The term is still used, as scattered farms and villages sometimes refer to the Weald in their names.

Etymology

The name "Weald" is derived from theOld English

Old English ( or , or ), or Anglo-Saxon, is the earliest recorded form of the English language, spoken in England and southern and eastern Scotland in the Early Middle Ages. It developed from the languages brought to Great Britain by Anglo-S ...

', meaning "forest

A forest is an ecosystem characterized by a dense ecological community, community of trees. Hundreds of definitions of forest are used throughout the world, incorporating factors such as tree density, tree height, land use, legal standing, ...

" (cognate of German ''Wald'', but unrelated to English "wood"). This comes from a Germanic root of the same meaning, and ultimately from Indo-European

The Indo-European languages are a language family native to the northern Indian subcontinent, most of Europe, and the Iranian plateau with additional native branches found in regions such as Sri Lanka, the Maldives, parts of Central Asia (e. ...

. ''Weald'' is specifically a West Saxon form; with '' wold'' as the Anglian dialect

A dialect is a Variety (linguistics), variety of language spoken by a particular group of people. This may include dominant and standard language, standardized varieties as well as Vernacular language, vernacular, unwritten, or non-standardize ...

form of the word. The Middle English

Middle English (abbreviated to ME) is a form of the English language that was spoken after the Norman Conquest of 1066, until the late 15th century. The English language underwent distinct variations and developments following the Old English pe ...

form of the word is ''wēld'', and the modern spelling is a reintroduction of the Old English form attributed to its use by William Lambarde

William Lambarde (18 October 1536 – 19 August 1601) was an English antiquarian, writer on legal subjects, and politician. He is particularly remembered as the author of ''A Perambulation of Kent'' (1576), the first English county history; ''Ei ...

in his ''A Perambulation of Kent'' of 1576.

In early medieval Britain, the area had the name ''Andredes weald'', meaning "the forest of Andred", the latter derived from '' Anderida'', the Roman name of present-day Pevensey

Pevensey ( ) is a village and civil parishes in England, civil parish in the Wealden District, Wealden district of East Sussex, England. The main village is located north-east of Eastbourne, one mile (1.6 km) inland from Pevensey Bay. The ...

. The area is also referred to in early English texts as ''Andredesleage'', where the second element, ''leage,'' is another Old English word for "woodland", represented by the modern '.

The adjective for "Weald" is "wealden".

Geology

The Weald is the eroded remains of a geological structure, an

The Weald is the eroded remains of a geological structure, an anticline

In structural geology, an anticline is a type of Fold (geology), fold that is an arch-like shape and has its oldest Bed (geology), beds at its core, whereas a syncline is the inverse of an anticline. A typical anticline is convex curve, c ...

, a dome of layered Lower Cretaceous

Lower may refer to:

* ''Lower'' (album), 2025 album by Benjamin Booker

* Lower (surname)

* Lower Township, New Jersey

*Lower Receiver (firearms)

* Lower Wick Gloucestershire, England

See also

* Nizhny

{{Disambiguation ...

rock

Rock most often refers to:

* Rock (geology), a naturally occurring solid aggregate of minerals or mineraloids

* Rock music, a genre of popular music

Rock or Rocks may also refer to:

Places United Kingdom

* Rock, Caerphilly, a location in Wale ...

s cut through by weathering

Weathering is the deterioration of rocks, soils and minerals (as well as wood and artificial materials) through contact with water, atmospheric gases, sunlight, and biological organisms. It occurs '' in situ'' (on-site, with little or no move ...

to expose the layers as sandstone

Sandstone is a Clastic rock#Sedimentary clastic rocks, clastic sedimentary rock composed mainly of grain size, sand-sized (0.0625 to 2 mm) silicate mineral, silicate grains, Cementation (geology), cemented together by another mineral. Sand ...

ridges and clay

Clay is a type of fine-grained natural soil material containing clay minerals (hydrous aluminium phyllosilicates, e.g. kaolinite, ). Most pure clay minerals are white or light-coloured, but natural clays show a variety of colours from impuriti ...

valleys. The oldest rocks exposed at the centre of the anticline are correlated with the Purbeck Beds

The Purbeck Group is an Upper Jurassic to Lower Cretaceous lithostratigraphic group (a sequence of rock strata) in south-east England. The name is derived from the district known as the Isle of Purbeck in Dorset where the strata are exposed in th ...

of the Upper Jurassic

The Late Jurassic is the third epoch of the Jurassic Period, and it spans the geologic time from 161.5 ± 1.0 to 143.1 ± 0.8 million years ago (Ma), which is preserved in Upper Jurassic strata.Owen 1987.

In European lithostratigraphy, the name ...

. Above these, the Cretaceous rocks, include the Wealden Group

The Wealden Group, occasionally also referred to as the Wealden Supergroup, is a group (stratigraphy), group (a sequence of rock strata) in the lithostratigraphy of southern England. The Wealden group consists of wiktionary:paralic, paralic to c ...

of alternating sands and claysthe Ashdown Sand Formation, Wadhurst Clay Formation

The Wadhurst Clay Formation is a geological unit which forms part of the Wealden Group and the middle part of the now unofficial Hastings Beds. These geological units make up the core of the geology of the High Weald in the English counties of West ...

, Tunbridge Wells Sand Formation (collectively known as the Hastings Beds

The Wealden Group, occasionally also referred to as the Wealden Supergroup, is a group (a sequence of rock strata) in the lithostratigraphy of southern England. The Wealden group consists of paralic to continental (freshwater) facies sedimentar ...

) and the Weald Clay

Weald Clay or the Weald Clay Formation is a Lower Cretaceous sedimentary rock unit underlying areas of South East England, between the North and South Downs, in an area called the Weald Basin. It is the uppermost unit of the Wealden Group of ...

. The Wealden Group

The Wealden Group, occasionally also referred to as the Wealden Supergroup, is a group (stratigraphy), group (a sequence of rock strata) in the lithostratigraphy of southern England. The Wealden group consists of wiktionary:paralic, paralic to c ...

is overlain by the Lower Greensand

The Lower Greensand Group is a geological unit present across large areas of Southern England. It was deposited during the Aptian and Albian ages of the Early Cretaceous. It predominantly consists of sandstone and unconsolidated sand that were d ...

and the Gault

The Gault Formation is a geological formation of stiff blue clay deposited in a calm, fairly deep-water marine environment during the Lower Cretaceous Period (Upper and Middle Albian). It is well exposed in the coastal cliffs at Copt Point in Fo ...

Formation, consisting of the Gault

The Gault Formation is a geological formation of stiff blue clay deposited in a calm, fairly deep-water marine environment during the Lower Cretaceous Period (Upper and Middle Albian). It is well exposed in the coastal cliffs at Copt Point in Fo ...

and the Upper Greensand

Greensand or green sand is a sand or sandstone which has a greenish color. This term is specifically applied to shallow marine sediment that contains noticeable quantities of rounded greenish grains. These grains are called ''glauconies'' and co ...

.

The rocks of the central part of the anticline include hard sandstone

Sandstone is a Clastic rock#Sedimentary clastic rocks, clastic sedimentary rock composed mainly of grain size, sand-sized (0.0625 to 2 mm) silicate mineral, silicate grains, Cementation (geology), cemented together by another mineral. Sand ...

s, and these form hills now called the ''High Weald''. The peripheral areas are mostly of softer sandstones and clays and form a gentler rolling landscape, the ''Low Weald''. The Weald–Artois Anticline continues some further south-eastwards under the Straits of Dover

The Strait of Dover or Dover Strait, historically known as the Dover Narrows, is the strait at the narrowest part of the English Channel, marking the boundary between the Channel and the North Sea, and separating Great Britain from continental ...

, and includes the Boulonnais of France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

.

In the first edition of ''On The Origin of Species

''On the Origin of Species'' (or, more completely, ''On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life'')The book's full original title was ''On the Origin of Species by M ...

'', Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English Natural history#Before 1900, naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all speci ...

used an estimate for the erosion of the chalk, sandstone and clay strata of the Weald in his theory of natural selection. Charles Darwin was a follower of Lyell's theory of uniformitarianism

Uniformitarianism, also known as the Doctrine of Uniformity or the Uniformitarian Principle, is the assumption that the same natural laws and processes that operate in our present-day scientific observations have always operated in the universe in ...

and decided to expand upon Lyell's theory with a quantitative estimate to determine if there was enough time in the history of the Earth to uphold his principles of evolution. He assumed the rate of erosion was around one inch per century and calculated the age of the Weald at around 300 million years. Were that true, he reasoned, the Earth itself must be much older. In 1862, William Thomson (later Lord Kelvin) published a paper "On the age of the sun's heat", in which – unaware of the process of solar fusion – he calculated the Sun had been burning for less than a million years, and put the outside limit of the age of the Earth

The age of Earth is estimated to be 4.54 ± 0.05 billion years. This age may represent the age of Earth's accretion (astrophysics), accretion, or Internal structure of Earth, core formation, or of the material from which Earth formed. This dating ...

at 200 million years. Based on these estimates he denounced Darwin's geological estimates as imprecise. Darwin saw Lord Kelvin's calculation as one of the most serious criticisms to his theory and removed his calculations on the Weald from the third edition of ''On the Origin of Species''.

Modern chronostratigraphy shows that the Weald Clays were laid down around 130 million years ago in the Early Cretaceous.

Many important fossils have been found in the sandstones and clays of the Weald, including ''Baryonyx

''Baryonyx'' () is a genus of theropod dinosaur which lived in the Barremian stage of the Early Cretaceous period, about 130–125 million years ago. The first skeleton was discovered in 1983 in the Smokejack Clay Pit, of Surrey, England, in ...

'', discovered in 1983. The Piltdown Man hoax specimen was claimed to have come from a gravel pit at Piltdown

Piltdown is a series of hamlets in East Sussex, England,VillagenetPiltdown in East Sussex accessed 1 June 2023 located south of Ashdown Forest. It is best known for the Piltdown Man hoax where amateur archaeologist Charles Dawson claimed to ...

near Uckfield

Uckfield () is a town in the Wealden District, Wealden District of East Sussex in South East England. The town is on the River Uck, one of the tributaries of the River Ouse, Sussex, River Ouse, on the southern edge of the Weald.

Etymology

"Uck ...

. The first ''Iguanodon

''Iguanodon'' ( ; meaning 'iguana-tooth'), named in 1825, is a genus of iguanodontian dinosaur. While many species found worldwide have been classified in the genus ''Iguanodon'', dating from the Late Jurassic to Early Cretaceous, Taxonomy (bi ...

'' was identified after the fossil collector and illustrator Mary Ann Mantell supposedly unearthed some fossilised teeth by a road near Cuckfield

Cuckfield ( ) is a village and civil parishes in England, civil parish in the Mid Sussex District, Mid Sussex District of West Sussex, England, on the southern slopes of the Weald. It lies south of London, north of Brighton, and east northea ...

in 1822. Her husband, the geologist Gideon Mantell

Gideon Algernon Mantell Membership of the Royal College of Surgeons, MRCS Fellow of the Royal Society, FRS (3 February 1790 – 10 November 1852) was an English obstetrician, geologist and paleontology, palaeontologist. His attempts to reconstr ...

sent them to various experts and this important find led to the discovery of dinosaurs.

The area contains significant reserves of shale oil

Shale oil is an unconventional oil produced from oil shale rock fragments by pyrolysis, hydrogenation, or thermal dissolution. These processes convert the organic matter within the rock (kerogen) into synthetic oil and gas. The resulting oil c ...

, totalling 4.4 billion barrels of oil

A barrel is one of several units of volume applied in various contexts; there are dry barrels, fluid barrels (such as the U.K. beer barrel and U.S. beer barrel), oil barrels, and so forth. For historical reasons, the volumes of some barrel unit ...

in the Wealden basin according to a 2014 study, which then Business and Energy Minister Michael Fallon

Sir Michael Cathel Fallon (born 14 May 1952) is a British politician who served as Secretary of State for Defence from 2014 to 2017. A member of the Conservative Party (UK), Conservative Party, he served as Member of Parliament (United Kingdom ...

said "will bring jobs and business opportunities" and significantly help with UK energy self-sufficiency. Fracking

Fracking (also known as hydraulic fracturing, fracing, hydrofracturing, or hydrofracking) is a well stimulation technique involving the fracturing of formations in bedrock by a pressurized liquid. The process involves the high-pressure inje ...

in the area would be required to achieve these objectives, which has been opposed by environmental groups.

History

Prehistoric evidence suggests that, following the

Prehistoric evidence suggests that, following the Mesolithic

The Mesolithic (Ancient Greek language, Greek: μέσος, ''mesos'' 'middle' + λίθος, ''lithos'' 'stone') or Middle Stone Age is the Old World archaeological period between the Upper Paleolithic and the Neolithic. The term Epipaleolithic i ...

hunter-gatherers, the Neolithic

The Neolithic or New Stone Age (from Ancient Greek, Greek 'new' and 'stone') is an archaeological period, the final division of the Stone Age in Mesopotamia, Asia, Europe and Africa (c. 10,000 BCE to c. 2,000 BCE). It saw the Neolithic Revo ...

inhabitants had turned to farming, with the resultant clearance of the forest. With the Iron Age

The Iron Age () is the final epoch of the three historical Metal Ages, after the Chalcolithic and Bronze Age. It has also been considered as the final age of the three-age division starting with prehistory (before recorded history) and progre ...

came the first use of the Weald as an industrial area. Wealden sandstones contain ironstone

Ironstone is a sedimentary rock, either deposited directly as a ferruginous sediment or created by chemical replacement, that contains a substantial proportion of an iron ore compound from which iron (Fe) can be smelted commercially.

Not to be c ...

, and with the additional presence of large amounts of timber for making charcoal

Charcoal is a lightweight black carbon residue produced by strongly heating wood (or other animal and plant materials) in minimal oxygen to remove all water and volatile constituents. In the traditional version of this pyrolysis process, ca ...

for fuel, the area was the centre of the Wealden iron industry

The Wealden iron industry was located in the Weald of south-eastern England. It was formerly an important industry, producing a large proportion of the wrought iron, bar iron made in England in the 16th century and most British cannon until abou ...

from then, through the Roman times

In modern historiography, ancient Rome is the Roman civilisation from the founding of the Italian city of Rome in the 8th century BC to the collapse of the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century AD. It encompasses the Roman Kingd ...

, until the last forge was closed in 1813. The index to the Ordnance Survey Map of Roman Britain lists 33 iron mines, and 67% of these are in the Weald.

The Weald is thought to have undergone repeated cycles of clearance and re-forestation, and the decline in the population following the end of the Romano British period allowed the tree cover to re-establish. According to the 9th-century ''Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

The ''Anglo-Saxon Chronicle'' is a collection of annals in Old English, chronicling the history of the Anglo-Saxons.

The original manuscript of the ''Chronicle'' was created late in the ninth century, probably in Wessex, during the reign of ...

'', the Weald measured or longer by in the Saxon era, stretching from Lympne

Lympne (), formerly also Lymne, is a village on the former shallow-gradient sea cliffs above the expansive agricultural plain of Romney Marsh in Kent. The settlement forms an L shape stretching from Port Lympne Zoo via Lympne Castle facing Ly ...

, near Romney Marsh

Romney Marsh is a sparsely populated wetland area in the counties of Kent and East Sussex in the south-east of England. It covers about . The Marsh has been in use for centuries, though its inhabitants commonly suffered from malaria until the ...

in Kent, to the Forest of Bere

The Forest of Bere is a mixed-use partially forested area in Hampshire immediately north of Fareham, Portsmouth and Roman Road, Havant and including a small part of the South Downs National Park.New Forest

The New Forest is one of the largest remaining tracts of unenclosed pasture land, heathland and forest in Southern England, covering southwest Hampshire and southeast Wiltshire. It was proclaimed a royal forest by William the Conqueror, featu ...

in Hampshire. The area was sparsely inhabited and inhospitable, being used mainly as a resource by people living on its fringes, much as in other places in Britain such as Dartmoor

Dartmoor is an upland area in southern Devon, South West England. The moorland and surrounding land has been protected by National Park status since 1951. Dartmoor National Park covers .

The granite that forms the uplands dates from the Carb ...

, the Fens

The Fens or Fenlands in eastern England are a naturally marshy region supporting a rich ecology and numerous species. Most of the fens were drained centuries ago, resulting in a flat, dry, low-lying agricultural region supported by a system o ...

and the Forest of Arden

The Forest of Arden is a territory and cultural reference point in the English West Midlands, that in antiquity and into the Early Modern Period covered much of that district: 'This great forest once extended across a wide band of Middle Engl ...

. While most of the Weald was used for transhumance

Transhumance is a type of pastoralism or Nomad, nomadism, a seasonal movement of livestock between fixed summer and winter pastures. In montane regions (''vertical transhumance''), it implies movement between higher pastures in summer and low ...

by communities at the edge of the Weald, several parts of the forest on the higher ridges in the interior seem to have been used for hunting by the kings of Sussex.

The forests of the Weald were often used as a place of refuge and sanctuary. The ''Anglo-Saxon Chronicle'' relates events during the Anglo-Saxon

The Anglo-Saxons, in some contexts simply called Saxons or the English, were a Cultural identity, cultural group who spoke Old English and inhabited much of what is now England and south-eastern Scotland in the Early Middle Ages. They traced t ...

conquest of Sussex

Sussex (Help:IPA/English, /ˈsʌsɪks/; from the Old English ''Sūþseaxe''; lit. 'South Saxons'; 'Sussex') is an area within South East England that was historically a kingdom of Sussex, kingdom and, later, a Historic counties of England, ...

when the native Britons

British people or Britons, also known colloquially as Brits, are the citizens of the United Kingdom, the British Overseas Territories, and the Crown dependencies.: British nationality law governs modern British citizenship and nationality, w ...

(whom the Anglo-Saxons called ''Welsh'') were driven from the coastal towns into the forest for sanctuary:

Domesday Book

Domesday Book ( ; the Middle English spelling of "Doomsday Book") is a manuscript record of the Great Survey of much of England and parts of Wales completed in 1086 at the behest of William the Conqueror. The manuscript was originally known by ...

of 1086 suggests that the Weald was sparsely populated, but Peter Brandon suggests that the inhabitants and settlements may have been undercounted. The population of the area increased steadily between 800 and 1300, as woodland was cleared, resulting in the ''bocage

Bocage (, ) is a terrain of mixed woodland and pasture characteristic of parts of northern France, southern England, Ireland, the Netherlands, northern Spain and northern Germany, in regions where pastoral farming is the dominant land use.

' ...

'' pattern of irregularly shaped fields. Charters of Sele

Sele may refer to:

Places Africa

*Sele, Burkina Faso, a village in the Ouéleni Department of Burkina Fase.

* Sele, Ethiopia, a town in Agbe municipality

Asia

*Sele, Turkey, a Turkish village in Kailar in Ottoman times

*Şələ, Azerbaijan

*Seleu ...

and Lewes Priories from the end of the 11th century, indicate that numerous churches had been established in the Sussex Weald. Similarly, the ''Domesday Monachorum'' of Christ Church Canterbury, compiled 1089–, suggests that Kent Weald had already been divided into parishes by the start of the 12th century.

The origins of several Wealden settlements are reflected in their toponyms

Toponymy, toponymics, or toponomastics is the study of '' toponyms'' (proper names of places, also known as place names and geographic names), including their origins, meanings, usage, and types. ''Toponym'' is the general term for a proper nam ...

. Villages whose names end in ''fold'', were established on better drained soils by inhabitants of the Sussex Coastal Plain in the late Anglo-Saxon period. The suffix derives from the Old English

Old English ( or , or ), or Anglo-Saxon, is the earliest recorded form of the English language, spoken in England and southern and eastern Scotland in the Early Middle Ages. It developed from the languages brought to Great Britain by Anglo-S ...

''falod'', meaning an enclosure of pasture

Pasture (from the Latin ''pastus'', past participle of ''pascere'', "to feed") is land used for grazing.

Types of pasture

Pasture lands in the narrow sense are enclosed tracts of farmland, grazed by domesticated livestock, such as horses, c ...

. These folds were occupied on a seasonal basis to graze livestock during the summer months. Settlements ending in ''den'', found in the Kentish Weald, were established on a similar basis. The seasonal settlements in the region are thought to have become permanently occupied by the end of the 12th century. By the outbreak of the Black Death in England

The Black Death was a bubonic plague pandemic, which reached England in June 1348. It was the first and most severe manifestation of the second pandemic, caused by '' Yersinia pestis'' bacteria. The term ''Black Death'' was not used until the la ...

in June 1348, most parts of the Weald were under human influence.

In 1216 during the First Barons' War

The First Barons' War (1215–1217) was a civil war in the Kingdom of England in which a group of rebellious major landowners (commonly referred to as English feudal barony, barons) led by Robert Fitzwalter waged war against John of England, K ...

, a guerilla force of archers from the Weald, led by William of Cassingham (nicknamed Willikin of the Weald), ambushed the French occupying army led by Prince Louis near Lewes

Lewes () is the county town of East Sussex, England. The town is the administrative centre of the wider Lewes (district), district of the same name. It lies on the River Ouse, Sussex, River Ouse at the point where the river cuts through the Sou ...

and drove them to the coast at Winchelsea

Winchelsea () is a town in the county of East Sussex, England, located between the High Weald and the Romney Marsh, approximately south west of Rye and north east of Hastings. The current town, which was founded in 1288, replaced an earli ...

. The timely arrival of a French fleet allowed the French forces to narrowly escape starvation. William was later granted a pension from the Crown and made warden of the Weald in reward for his services.

The inhabitants of the Weald remained largely independent and hostile to outsiders during the next decades. In 1264 during the Second Barons' War

The Second Barons' War (1264–1267) was a civil war in Kingdom of England, England between the forces of barons led by Simon de Montfort, 6th Earl of Leicester, Simon de Montfort against the royalist forces of Henry III of England, King Hen ...

, the royalist army of King Henry III of England

Henry III (1 October 1207 – 16 November 1272), also known as Henry of Winchester, was King of England, Lord of Ireland, and Duke of Aquitaine from 1216 until his death in 1272. The son of John, King of England, King John and Isabella of Ang ...

marched through the Weald in order to force the submission of the Cinque Ports

The confederation of Cinque Ports ( ) is a historic group of coastal towns in south-east England – predominantly in Kent and Sussex, with one outlier (Brightlingsea) in Essex. The name is Old French, meaning "five harbours", and alludes to ...

. Even though they were not aligned with the rebellious barons, the Weald's natives – mostly operating as archers – opposed the royalist advance, using guerrilla warfare

Guerrilla warfare is a form of unconventional warfare in which small groups of irregular military, such as rebels, partisans, paramilitary personnel or armed civilians, which may include recruited children, use ambushes, sabotage, terrori ...

. Even though they were unable to stop the army, their attacks inflicted substantial losses on the royalists. In retribution, King Henry ordered the execution of any Weald archers who were captured alive, for instance beheading 300 after a local shot his cook. The king also fined Battle Abbey

Battle Abbey is a partially ruined Benedictine abbey in Battle, East Sussex, England. The abbey was built on the site of the Battle of Hastings and dedicated to St Martin of Tours. It is a Scheduled Monument.

The Grade I listed site is now o ...

for the disloyalty of its tenants.

Geography

The Weald begins north-east ofPetersfield

Petersfield is a market town and civil parish in the East Hampshire district of Hampshire, England. It is north of Portsmouth. The town has its own Petersfield railway station, railway station on the Portsmouth Direct line, the mainline rai ...

in Hampshire

Hampshire (, ; abbreviated to Hants.) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South East England. It is bordered by Berkshire to the north, Surrey and West Sussex to the east, the Isle of Wight across the Solent to the south, ...

and extends across Surrey

Surrey () is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South East England. It is bordered by Greater London to the northeast, Kent to the east, East Sussex, East and West Sussex to the south, and Hampshire and Berkshire to the wes ...

and Kent

Kent is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South East England. It is bordered by Essex across the Thames Estuary to the north, the Strait of Dover to the south-east, East Sussex to the south-west, Surrey to the west, and Gr ...

in the north, and Sussex in the south. The western parts in Hampshire and West Sussex, known as the Western Weald

The western Weald is an area of undulating countryside in Hampshire and West Sussex containing a mixture of woodland and heathland areas.

It lies to the south of the towns of Bordon, Haslemere and Rake, West Sussex, Rake and to the west of the to ...

, are included in the South Downs National Park

The South Downs National Park is England's newest national parks of England and Wales, national park, designated on 31 March 2010. The park, covering an area of in southern England, stretches for from Winchester in the west to Eastbourne in t ...

. Other protected parts of the Weald are included in the Surrey Hills Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty and the High Weald Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty

The High Weald National Landscape is in south-east England. Covering an area of , it takes up parts of Kent,

Surrey, East Sussex, and West Sussex. It is the fourth largest Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB) in England and Wales. It ha ...

. In extent it covers about from west to east, and about from north to south, covering an area of some . The eastern end of the High Weald, the English Channel

The English Channel, also known as the Channel, is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that separates Southern England from northern France. It links to the southern part of the North Sea by the Strait of Dover at its northeastern end. It is the busi ...

coast, is marked in the centre by the high sandstone cliffs from Hastings

Hastings ( ) is a seaside town and Borough status in the United Kingdom, borough in East Sussex on the south coast of England,

east of Lewes and south east of London. The town gives its name to the Battle of Hastings, which took place to th ...

to Pett Level; and by former sea cliffs now fronted by the Pevensey and Romney Marshes on either side.

Much of the ''High Weald'', the central part, is designated as the High Weald Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty. Its landscape is described as:

Ashdown Forest

Ashdown Forest is an ancient area of open heathland occupying the highest sandy ridge-top of the High Weald National Landscape. It is situated south of London in the county East Sussex, England. Rising to an elevation

of above sea level, its ...

, an extensive area of heathland and woodland occupying the highest sandy ridge-top at the centre of the High Weald, is a former royal deer-hunting forest created by the Normans and said to be the largest remaining part of ''Andredesweald''.

There are centres of settlement, the largest of which are Horsham

Horsham () is a market town on the upper reaches of the River Arun on the fringe of the Weald in West Sussex, England. The town is south south-west of London, north-west of Brighton and north-east of the county town of Chichester. Nearby to ...

, Burgess Hill

Burgess Hill () is a town and civil parish in West Sussex, England, close to the border with East Sussex, on the edge of the South Downs National Park, south of London, north of Brighton and Hove, and northeast of the county town, Chichester. ...

, East Grinstead

East Grinstead () is a town in West Sussex, England, near the East Sussex, Surrey, and Kent borders, south of London, northeast of Brighton, and northeast of the county town of Chichester. Situated in the northeast corner of the county, bord ...

, Haywards Heath

Haywards Heath ( ) is a town in West Sussex, England, south of London, north of Brighton, south of Gatwick Airport and northeast of the county town, Chichester. Nearby towns include Burgess Hill to the southwest, Horsham to the northwest, ...

, Tonbridge

Tonbridge ( ) (historic spelling ''Tunbridge'') is a market town in Kent, England, on the River Medway, north of Royal Tunbridge Wells, south west of Maidstone and south east of London. In the administrative borough of Tonbridge and Mall ...

, Tunbridge Wells

Royal Tunbridge Wells (formerly, until 1909, and still commonly Tunbridge Wells) is a town in Kent, England, southeast of Central London. It lies close to the border with East Sussex on the northern edge of the High Weald, whose sandstone ...

, Crowborough

Crowborough is a town and civil parish in East Sussex, England, in the Weald at the edge of Ashdown Forest and the highest town in the High Weald AONB, High Weald Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty.

It is located south-west of Royal Tunbridge ...

; and the area along the coast from Hastings and Bexhill-on-Sea

Bexhill-on-Sea (often shortened to Bexhill) is a seaside town and civil parish in the Rother District in the county of East Sussex in South East England. It is located along the Sussex Coast and between the towns of Hastings, England, Hastings ...

to Rye

Rye (''Secale cereale'') is a grass grown extensively as a grain, a cover crop and a forage crop. It is grown principally in an area from Eastern and Northern Europe into Russia. It is much more tolerant of cold weather and poor soil than o ...

and Hythe.

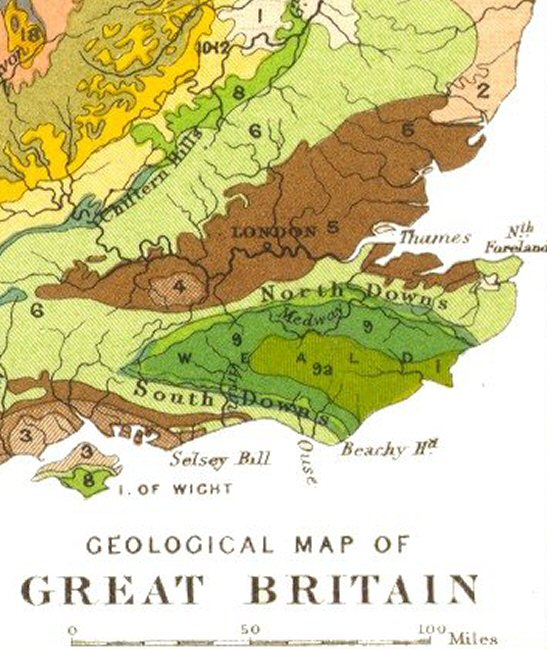

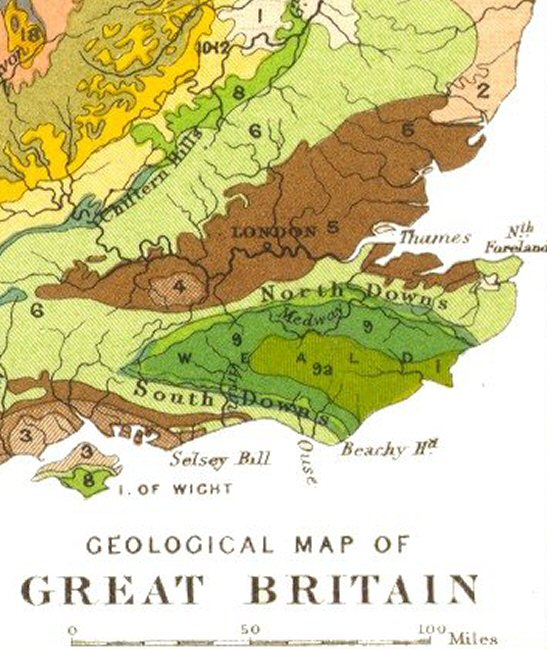

The geological map shows the High Weald in lime green (9a).

The ''Low Weald'', the periphery of the Weald, is shown as darker green on the map (9), and has an entirely different character. It is in effect the eroded outer edges of the High Weald, revealing a mixture of sandstone outcrops within the underlying clay. As a result, the landscape is of wide and low-lying clay vales with small woodlands ( "shaws") and fields. There is a great deal of surface water: ponds and many meandering streams.

Some areas, such as the flat plain around Crawley

Crawley () is a town and Borough status in the United Kingdom, borough in West Sussex, England. It is south of London, north of Brighton and Hove, and north-east of the county town of Chichester. Crawley covers an area of and had a populat ...

, have been utilised for urban use: here are Gatwick Airport

Gatwick Airport , also known as London Gatwick Airport (), is the Airports of London, secondary international airport serving London, West Sussex and Surrey. It is located near Crawley in West Sussex, south of Central London. In 2024, Gatwic ...

and its related developments and the Horley

Horley is a town in the borough of Reigate and Banstead in Surrey, England, south of the towns of Reigate and Redhill. The county border with West Sussex is to the south with Crawley and Gatwick Airport close to the town.

It has its own econ ...

-Crawley commuter settlements. Otherwise the Low Weald retains its historic settlement pattern, where the villages and small towns occupy harder outcrops of rocks. Settlements tend to be small, because of its original wooded nature and heavy clay soils, although many villages with good transport links have undergone expansion starting in the 20th century.

The Weald is drained by the many streams radiating from it, the majority being tributaries of the surrounding major rivers: particularly the Mole

Mole (or Molé) may refer to:

Animals

* Mole (animal) or "true mole"

* Golden mole, southern African mammals

* Marsupial mole

Marsupial moles, the Notoryctidae family, are two species of highly specialized marsupial mammals that are found i ...

, Medway

Medway is a Unitary authorities of England, unitary authority area with Borough status in the United Kingdom, borough status in the ceremonial county of Kent in South East England. It was formed in 1998 by merging the boroughs of City of Roche ...

, Stour, Rother, Cuckmere

The Cuckmere River rises near Heathfield in East Sussex, England on the southern slopes of the Weald. The name of the river probably comes from an Old English word meaning "fast-flowing", since it descends over in its initial . It flows into ...

, Ouse, Adur and Arun. Many of these streams provided the power for the watermill

A watermill or water mill is a mill that uses hydropower. It is a structure that uses a water wheel or water turbine to drive a mechanical process such as mill (grinding), milling (grinding), rolling, or hammering. Such processes are needed in ...

s, blast furnaces

A blast furnace is a type of metallurgical furnace used for smelting to produce industrial metals, generally pig iron, but also others such as lead or copper. ''Blast'' refers to the combustion air being supplied above atmospheric pressure.

In a ...

and hammers of the iron industry and the cloth mills. By the later 16th century, there were as many as one hundred furnaces and forges operating in the Weald.

Transport infrastructure

The M25, M26 andM20 motorway

The M20 is a Controlled-access highway, motorway in Kent, England. It follows on from the A20 road (England), A20 at Swanley, meeting the M25 motorway, M25, and continuing on to Folkestone, providing a link to the Channel Tunnel and the ports a ...

s all use the Vale of Holmesdale

Holmesdale, also known as the Vale of Holmesdale, is a valley in South-East England that falls between the hill ranges of the North Downs and the Greensand Ridge of the Weald, in the counties of Kent and Surrey. It stretches from Folkestone o ...

to the north, and therefore run along or near the northern edge of the Weald. The M23/A23 road

The A23 road is a major road in the United Kingdom between London and Brighton, East Sussex, England. It is managed by Transport for London for the section inside the Greater London boundary, Surrey County Council and West Sussex County C ...

to Brighton

Brighton ( ) is a seaside resort in the city status in the United Kingdom, city of Brighton and Hove, East Sussex, England, south of London.

Archaeological evidence of settlement in the area dates back to the Bronze Age Britain, Bronze Age, R ...

, uses the western, narrower, part of the Weald where there are stream headwaters, crossing it from north to south. Other roads take similar routes, although they often have long hills and many bends: the more sedate, but busy A21 trunk road to Hastings is still beset with traffic delays, despite having had some new sections.

Five railways once crossed the Weald, now reduced to three. Building them provided the engineers with difficulties in crossing the terrain, with the hard sandstone adding to their problems. The Brighton Main Line

The Brighton Main Line is a railway line in southern England linking London to Brighton. It starts at two termini in the capital, and , and the branches from each meet at , from where the route continues southwards via to the coast. The line ...

followed the same route as its road predecessors: although it necessitated the construction of Balcombe tunnel

Balcombe tunnel is a railway tunnel on the Brighton Main Line through the Weald, Sussex Weald between Three Bridges railway station, Three Bridges and Balcombe railway station, Balcombe. It is long. The track is electrified with a 750 V DC thir ...

and the Ouse Valley Viaduct. Tributaries of the River Ouse provided some assistance in the building of now-closed East Grinstead

East Grinstead () is a town in West Sussex, England, near the East Sussex, Surrey, and Kent borders, south of London, northeast of Brighton, and northeast of the county town of Chichester. Situated in the northeast corner of the county, bord ...

–Lewes

Lewes () is the county town of East Sussex, England. The town is the administrative centre of the wider Lewes (district), district of the same name. It lies on the River Ouse, Sussex, River Ouse at the point where the river cuts through the Sou ...

and Uckfield

Uckfield () is a town in the Wealden District, Wealden District of East Sussex in South East England. The town is on the River Uck, one of the tributaries of the River Ouse, Sussex, River Ouse, on the southern edge of the Weald.

Etymology

"Uck ...

–Lewes lines. The Tonbridge–Hastings line had to negotiate difficult terrain when it was first built, necessitating many sharp curves and tunnels; and similar problems had to be faced with the Ashford-Hastings line.

Several long-distance footpaths

A long-distance trail (or long-distance footpath, track, way, greenway (landscape), greenway) is a longer recreational trail mainly through rural areas used for hiking, backpacking (wilderness), backpacking, cycling, equestrianism or cross-co ...

criss-cross the Weald, and it is well-mapped recreationally, covered by routes from:

* The Ramblers' Association

The Ramblers' Association, branded simply as the Ramblers, is Great Britain's walking charity. The Ramblers is also a membership organisation with around 100,000 members and a network of volunteers who maintain and protect the path network. T ...

s and most District Councils for walkers

* Sustrans

Sustrans ( ) is a United Kingdom-based walking, wheeling and cycling charity, and the custodian of the National Cycle Network.

Its flagship project is the National Cycle Network, which has created of signed cycle routes throughout the United ...

and local county councils for cyclists

Cycling, also known as bicycling or biking, is the activity of riding a bicycle or other types of pedal-driven human-powered vehicles such as balance bikes, unicycles, tricycles, and quadricycles. Cycling is practised around the world for pur ...

Farming

Neither the thin infertile sands of the High Weald or the wet sticky clays of the Low Weald are suited to intensive arable farming and thetopography

Topography is the study of the forms and features of land surfaces. The topography of an area may refer to the landforms and features themselves, or a description or depiction in maps.

Topography is a field of geoscience and planetary sci ...

of the area often increases the difficulties. There are limited areas of fertile greensand which can be used for intensive vegetable growing, as in the valley of the Western Rother. Historically the area of cereals grown has varied greatly with changes in prices, increasing during the Napoleonic Wars

{{Infobox military conflict

, conflict = Napoleonic Wars

, partof = the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars

, image = Napoleonic Wars (revision).jpg

, caption = Left to right, top to bottom:Battl ...

and during and since World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

.

About 60% of the High Weald farmed land is grassland, with about 20% being arable.

The Weald has its own breed of cattle, called the Sussex

Sussex (Help:IPA/English, /ˈsʌsɪks/; from the Old English ''Sūþseaxe''; lit. 'South Saxons'; 'Sussex') is an area within South East England that was historically a kingdom of Sussex, kingdom and, later, a Historic counties of England, ...

, although the breed has been as numerous in Kent and parts of Surrey. Bred from the strong hardy oxen, which continued to be used to plough the clay soils of the Low Weald longer than in most places, these red beef cattle were highly praised by Arthur Young in his book ''Agriculture of Sussex'' when visiting Sussex in the 1790s. William Cobbett

William Cobbett (9 March 1763 – 18 June 1835) was an English pamphleteer, journalist, politician, and farmer born in Farnham, Surrey. He was one of an Agrarianism, agrarian faction seeking to reform Parliament, abolish "rotten boroughs", restr ...

commented on finding some of the finest cattle on some of the region's poorest subsistence farms on the High Weald. Pigs, which were kept by most households in the past, were able to be fattened in autumn on acorns in the extensive oak woods. In his novel ''Memoirs of a Fox-hunting Man'', the poet and novelist Siegfried Sassoon

Siegfried Loraine Sassoon (8 September 1886 – 1 September 1967) was an English war poet, writer, and soldier. Decorated for bravery on the Western Front (World War I), Western Front, he became one of the leading poets of the First World ...

refers to "the agricultural serenity of the Weald widespread in the delicate hazy sunshine".

Viticulture

Viticulture (, "vine-growing"), viniculture (, "wine-growing"), or winegrowing is the cultivation and harvesting of grapes. It is a branch of the science of horticulture. While the native territory of ''Vitis vinifera'', the common grape vine ...

has expanded quite rapidly across the Weald, where the climate and soil is well suited to the growing of grapes, with over 20 vineyards now in the Wealden district alone

Wildlife

The Weald has largely maintained its wooded character, with woodland still covering 23% of the overall area (one of the highest levels in England) and the proportion is considerably higher in some central parts. The sandstones of the Wealden rocks are usually acidic, often leading to the development of acidic habitats such asheathland

A heath () is a shrubland habitat found mainly on free-draining infertile, acidic soils and is characterised by open, low-growing woody vegetation. Moorland is generally related to high-ground heaths with—especially in Great Britain—a coole ...

, the largest remaining areas of which are in Ashdown Forest

Ashdown Forest is an ancient area of open heathland occupying the highest sandy ridge-top of the High Weald National Landscape. It is situated south of London in the county East Sussex, England. Rising to an elevation

of above sea level, its ...

and near Thursley

Thursley is a village and civil parish in southwest Surrey, west of the A3 between Milford and Hindhead. An associated hamlet is Bowlhead Green. To the east is Brook. In the south of the parish rises the Greensand Ridge, in this section re ...

.

Although common in France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

, the wild boar

The wild boar (''Sus scrofa''), also known as the wild swine, common wild pig, Eurasian wild pig, or simply wild pig, is a Suidae, suid native to much of Eurasia and North Africa, and has been introduced to the Americas and Oceania. The speci ...

became extinct in Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the north-west coast of continental Europe, consisting of the countries England, Scotland, and Wales. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the List of European ...

by the 17th century, but wild breeding populations have recently returned in the Weald, following escapes from boar farms.

Culture

The Weald has been associated with many writers, particularly in the 19th and early 20th centuries. These includeVita Sackville-West

Victoria Mary, Lady Nicolson, Order of the Companions of Honour, CH (née Sackville-West; 9 March 1892 – 2 June 1962), usually known as Vita Sackville-West, was an English author and garden designer.

Sackville-West was a successful nov ...

(1892–1962), Sir Arthur Conan Doyle

Sir Arthur Ignatius Conan Doyle (22 May 1859 – 7 July 1930) was a British writer and physician. He created the character Sherlock Holmes in 1887 for ''A Study in Scarlet'', the first of four novels and fifty-six short stories about Hol ...

(1859-1930) and Rudyard Kipling

Joseph Rudyard Kipling ( ; 30 December 1865 – 18 January 1936)''The Times'', (London) 18 January 1936, p. 12. was an English journalist, novelist, poet, and short-story writer. He was born in British Raj, British India, which inspired much ...

(1865–1936). The setting for A.A. Milne's ''Winnie-the-Pooh

Winnie-the-Pooh (also known as Edward Bear, Pooh Bear or simply Pooh) is a fictional Anthropomorphism, anthropomorphic teddy bear created by English author A. A. Milne and English illustrator E. H. Shepard. Winnie-the-Pooh first appeared by ...

'' stories was inspired by Ashdown Forest

Ashdown Forest is an ancient area of open heathland occupying the highest sandy ridge-top of the High Weald National Landscape. It is situated south of London in the county East Sussex, England. Rising to an elevation

of above sea level, its ...

, near Milne's country home at Hartfield

Hartfield is a village and civil parish in the Wealden district of East Sussex, England. The parish also includes the settlements of Colemans Hatch, Hammerwood and Holtye, all lying on the northern edge of Ashdown Forest.

Geography

The main ...

. John Evelyn

John Evelyn (31 October 162027 February 1706) was an English writer, landowner, gardener, courtier and minor government official, who is now best known as a diary, diarist. He was a founding Fellow of the Royal Society.

John Evelyn's Diary, ...

(1620–1706), whose family estate was Wotton House

Wotton House, Wotton Underwood, Buckinghamshire, England, is a stately home built between 1704 and 1714, to a design very similar to that of the contemporary version of Buckingham House. The house is an example of English Baroque and a Grade I ...

on the River Tillingbourne

The River Tillingbourne (also known as the Tilling Bourne) runs along the south side of the North Downs and joins the River Wey at Guildford. Its source is a mile south of Tilling Springs to the north of Leith Hill at and it runs through Friday ...

near Dorking

Dorking () is a market town in Surrey in South East England about south-west of London. It is in Mole Valley, Mole Valley District and the non-metropolitan district, council headquarters are to the east of the centre. The High Street runs ro ...

, Surrey, was an essayist, diarist, and early author of botany, gardening and geography. The second half of E. M. Forster's ''A Room with a View

''A Room with a View'' is a 1908 novel by English writer E. M. Forster, about a young woman in the restrained culture of Edwardian-era England. Set in Italy and England, the story is both a romance and a humorous critique of English society ...

'' takes place at the protagonist's family home, "Windy Corner", in the Weald.

Sir Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 1874 – 24 January 1965) was a British statesman, military officer, and writer who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1940 to 1945 (Winston Churchill in the Second World War, ...

, British statesman and a prolific writer himself, did much of his writing at his country house, Chartwell

Chartwell is a English country house, country house near Westerham, Kent, in South East England. For over forty years, it was the home of Sir Winston Churchill. He bought the property in September 1922 and lived there until shortly before his ...

, near Westerham

Westerham is a town and civil parishes in England, civil parish in the Sevenoaks District of Kent, England. It is located 3.4 miles east of Oxted and 6 miles west of Sevenoaks, adjacent to the Kent border with both Greater London and Surrey.

I ...

, which has extensive views over the Weald. The view from the house was of crucial importance to Churchill; he once remarked, "I bought Chartwell for that view."

Sport

The game ofcricket

Cricket is a Bat-and-ball games, bat-and-ball game played between two Sports team, teams of eleven players on a cricket field, field, at the centre of which is a cricket pitch, pitch with a wicket at each end, each comprising two Bail (cr ...

may have originated prior to the 13th century in the Weald. The related game of stoolball

Stoolball is a sport that dates back to at least the 15th century, originating in Sussex, southern England. It is considered a "traditional striking and fielding sport" and may be an ancestor of cricket (a game it resembles in some respects), b ...

is still popular in the Weald, it was originally played mainly by women's teams, but since the formation of the Sussex league at the beginning of the 20th century it has been played by both men and women.

Other English wealds and wolds

Several other areas in southern England have the name "Weald", includingNorth Weald

North Weald Bassett, or simply North Weald ( ), is a village and civil parish in the Epping Forest district of Essex, England. The village is within the North Weald Ridges and Valleys landscape area.

A market is held every Saturday and Bank Ho ...

in Essex

Essex ( ) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in the East of England, and one of the home counties. It is bordered by Cambridgeshire and Suffolk to the north, the North Sea to the east, Kent across the Thames Estuary to the ...

, and Harrow Weald

Harrow Weald is a suburban district in Greater London, England. Located about north of Harrow, London, Harrow, Harrow Weald is formed from a leafy 1930s suburban development along with ancient woodland of Harrow Weald Common. It forms part of ...

in north-west London

London is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of both England and the United Kingdom, with a population of in . London metropolitan area, Its wider metropolitan area is the largest in Wester ...

.

"Wold" is used as the name for various open rolling upland areas in the North of England, including the Yorkshire Wolds

The Yorkshire Wolds are hills in the counties of the East Riding of Yorkshire and North Yorkshire in Northern England. They are the northernmost chalk hills in the UK and within lies the northernmost chalk stream in Europe, the Gypsey Race.

...

and the Lincolnshire Wolds

The Lincolnshire Wolds which also includes the Lincolnshire Wolds National Landscape are a range of low hills in the county of Lincolnshire, England which runs roughly parallel with the North Sea coast, from the Humber Estuary just west of the t ...

, although these are, by contrast, chalk uplands.

The Cotswolds

The Cotswolds ( ) is a region of central South West England, along a range of rolling hills that rise from the meadows of the upper River Thames to an escarpment above the Severn Valley and the Vale of Evesham. The area is defined by the bedroc ...

are a major geographical feature of central England, forming a south-west to north-east line across the country.

See also

*Weald and Downland Open Air Museum

The Weald and Downland Living Museum (known as the Weald and Downland Open Air Museum until January 2017) is an open-air museum in Singleton, West Sussex, Singleton, West Sussex. The museum is a Charitable organization, registered charity.

The ...

* Recreational walks in Kent

* History of Sussex

Sussex , from the Old English 'Sūþseaxe' ('South Saxons'), is a historic county in South East England.

Evidence from a fossil of Boxgrove Man (''Homo heidelbergensis'') shows that Sussex has been inhabited for at least 500,000 years. It i ...

Notes

References

Sources

* * * * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

* {{Coord, 51, N, 0.4, E, region:GB, display=title Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty in England Hills of East Sussex Hills of Kent Hills of Surrey Hills of West Sussex Wealden District Forests and woodlands of Kent Forests and woodlands of East Sussex Forests and woodlands of Surrey