Treaty Of Cateau-Cambrésis on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Treaty of Cateau-Cambrésis in April 1559 ended the

This division was driven by the administrative complexity of managing the two empires as a single entity, but also reflected strategic differences. While Spain was a global maritime superpower, the Austrian Habsburgs focused on securing a pre-eminent position in Germany and managing the threat posed by the

This division was driven by the administrative complexity of managing the two empires as a single entity, but also reflected strategic differences. While Spain was a global maritime superpower, the Austrian Habsburgs focused on securing a pre-eminent position in Germany and managing the threat posed by the  Despite these successes, Philip was struggling to finance the war, and in December 1558 advised his commander in Flanders, Emmanuel Philibert, that he could no longer pay his troops. Similar problems meant Henry II of France was also willing to reach an agreement, especially after France occupied the Three Bishoprics in 1552, and recaptured Calais in January 1558. In addition, internal divisions caused by the rise of Protestantism in France exacerbated splits within the nobility, and led to the outbreak of the

Despite these successes, Philip was struggling to finance the war, and in December 1558 advised his commander in Flanders, Emmanuel Philibert, that he could no longer pay his troops. Similar problems meant Henry II of France was also willing to reach an agreement, especially after France occupied the Three Bishoprics in 1552, and recaptured Calais in January 1558. In addition, internal divisions caused by the rise of Protestantism in France exacerbated splits within the nobility, and led to the outbreak of the

* Presiding negotiator:

* Presiding negotiator:

Emmanuel Philibert, Duke of Savoy married Margaret of France, Duchess of Berry, the sister of Henry II of France. Philip II of Spain married Elisabeth, the daughter of Henry II of France. Often overlooked, this has been described as "the most important marriage treaty of the 16th century". During a

Emmanuel Philibert, Duke of Savoy married Margaret of France, Duchess of Berry, the sister of Henry II of France. Philip II of Spain married Elisabeth, the daughter of Henry II of France. Often overlooked, this has been described as "the most important marriage treaty of the 16th century". During a

Photocopies of the Franco-Spanish Treaty of Cateau-Cambrésis in the original Spanish text

– ieg-friedensvertraege.de Leibniz Institute for European History {{Authority control 1559 in England 1559 in Italy 1559 in France 1559 in Spain 1559 in the Holy Roman Empire Cateau-Cambrésis Cateau-Cambrésis Cateau-Cambrésis Cateau-Cambrésis Henry II of France Ferdinand I, Holy Roman Emperor Philip II of Spain Elizabeth I Italian War of 1551–1559

Italian Wars

The Italian Wars were a series of conflicts fought between 1494 and 1559, mostly in the Italian Peninsula, but later expanding into Flanders, the Rhineland and Mediterranean Sea. The primary belligerents were the House of Valois, Valois kings o ...

(1494–1559). It consisted of two separate treaties, one between England

England is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is located on the island of Great Britain, of which it covers about 62%, and List of islands of England, more than 100 smaller adjacent islands. It ...

and France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

on 2 April, and another between France and Spain

Spain, or the Kingdom of Spain, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe with territories in North Africa. Featuring the Punta de Tarifa, southernmost point of continental Europe, it is the largest country in Southern Eur ...

on 3 April. Although he was not a signatory, both were approved by Emperor Ferdinand I, since many of the territorial exchanges concerned states within the Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire, also known as the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation after 1512, was a polity in Central and Western Europe, usually headed by the Holy Roman Emperor. It developed in the Early Middle Ages, and lasted for a millennium ...

.

Henry II of France abandoned claims on the Italian states ruled by Philip II of Spain

Philip II (21 May 152713 September 1598), sometimes known in Spain as Philip the Prudent (), was King of Spain from 1556, King of Portugal from 1580, and King of Naples and List of Sicilian monarchs, Sicily from 1554 until his death in 1598. He ...

(the southern kingdoms of Naples

Naples ( ; ; ) is the Regions of Italy, regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 908,082 within the city's administrative limits as of 2025, while its Metropolitan City of N ...

, Sicily

Sicily (Italian language, Italian and ), officially the Sicilian Region (), is an island in the central Mediterranean Sea, south of the Italian Peninsula in continental Europe and is one of the 20 regions of Italy, regions of Italy. With 4. ...

, and Sardinia

Sardinia ( ; ; ) is the Mediterranean islands#By area, second-largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after Sicily, and one of the Regions of Italy, twenty regions of Italy. It is located west of the Italian Peninsula, north of Tunisia an ...

, along with the Duchy of Milan

The Duchy of Milan (; ) was a state in Northern Italy, created in 1395 by Gian Galeazzo Visconti, then the lord of Milan, and a member of the important Visconti of Milan, Visconti family, which had been ruling the city since 1277. At that time, ...

in the north), restored an independent Savoy

Savoy (; ) is a cultural-historical region in the Western Alps. Situated on the cultural boundary between Occitania and Piedmont, the area extends from Lake Geneva in the north to the Dauphiné in the south and west and to the Aosta Vall ...

, returned Corsica

Corsica ( , , ; ; ) is an island in the Mediterranean Sea and one of the Regions of France, 18 regions of France. It is the List of islands in the Mediterranean#By area, fourth-largest island in the Mediterranean and lies southeast of the Metro ...

to Genoa

Genoa ( ; ; ) is a city in and the capital of the Italian region of Liguria, and the sixth-largest city in Italy. As of 2025, 563,947 people live within the city's administrative limits. While its metropolitan city has 818,651 inhabitan ...

, and formally recognised the Protestant

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that emphasizes Justification (theology), justification of sinners Sola fide, through faith alone, the teaching that Salvation in Christianity, salvation comes by unmerited Grace in Christianity, divin ...

Elizabeth I

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was List of English monarchs, Queen of England and List of Irish monarchs, Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. She was the last and longest reigning monarch of the House of Tudo ...

as queen of England, rather than her Catholic

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

cousin, Mary, Queen of Scots

Mary, Queen of Scots (8 December 1542 – 8 February 1587), also known as Mary Stuart or Mary I of Scotland, was List of Scottish monarchs, Queen of Scotland from 14 December 1542 until her forced abdication in 1567.

The only surviving legit ...

. In exchange, France strengthened its southern, eastern and northern borders, confirming the occupation of the Three Bishoprics and the recapture of Calais from England.

Background

TheItalian Wars

The Italian Wars were a series of conflicts fought between 1494 and 1559, mostly in the Italian Peninsula, but later expanding into Flanders, the Rhineland and Mediterranean Sea. The primary belligerents were the House of Valois, Valois kings o ...

between the House of Valois and the House of Habsburg

The House of Habsburg (; ), also known as the House of Austria, was one of the most powerful Dynasty, dynasties in the history of Europe and Western civilization. They were best known for their inbreeding and for ruling vast realms throughout ...

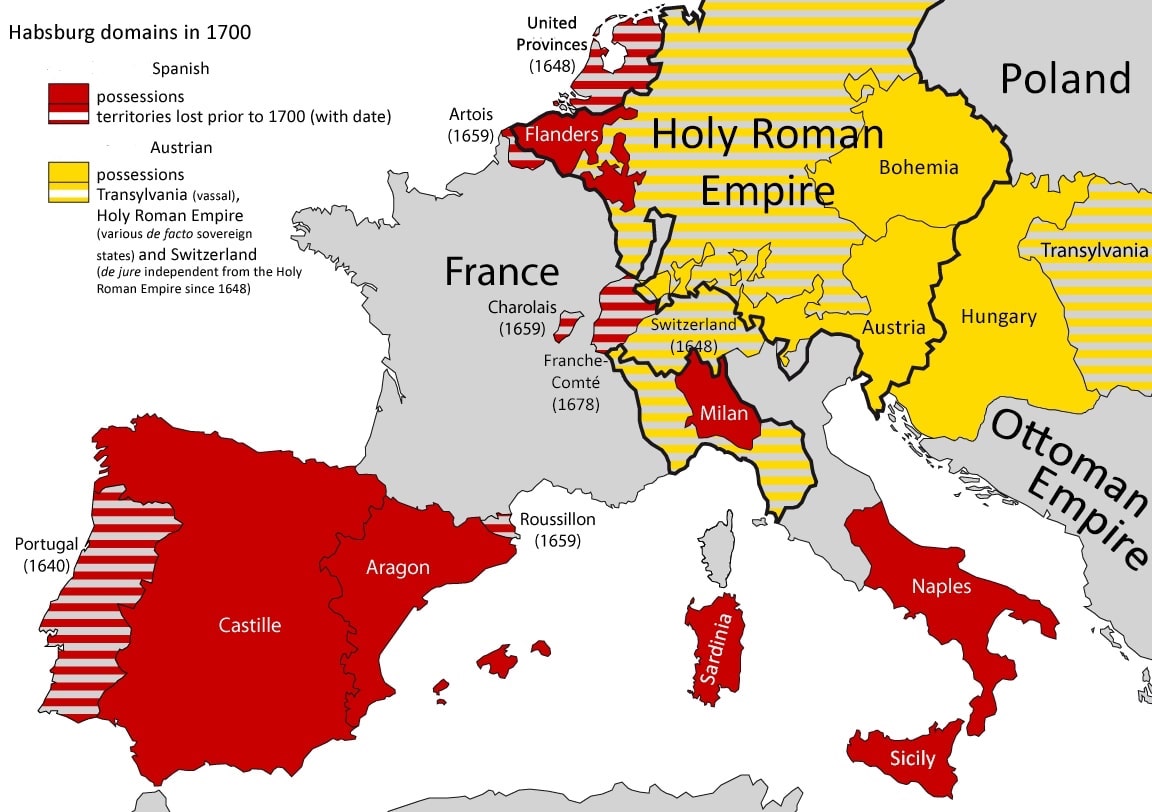

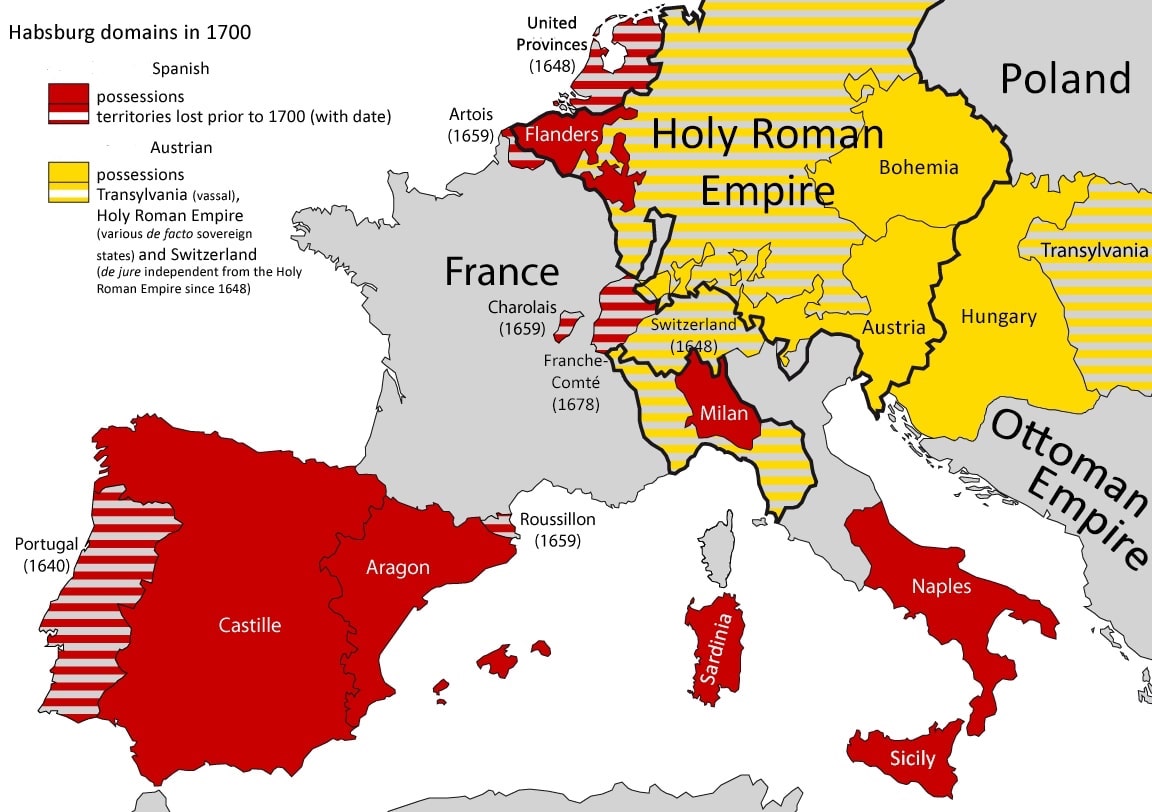

began in 1494, and lasted for over 60 years. For much of this period, Spain

Spain, or the Kingdom of Spain, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe with territories in North Africa. Featuring the Punta de Tarifa, southernmost point of continental Europe, it is the largest country in Southern Eur ...

and the Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire, also known as the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation after 1512, was a polity in Central and Western Europe, usually headed by the Holy Roman Emperor. It developed in the Early Middle Ages, and lasted for a millennium ...

were ruled by Emperor Charles V until he abdicated in January 1556 and divided his possessions. The lands of the Habsburg monarchy

The Habsburg monarchy, also known as Habsburg Empire, or Habsburg Realm (), was the collection of empires, kingdoms, duchies, counties and other polities (composite monarchy) that were ruled by the House of Habsburg. From the 18th century it is ...

, often referred to as "Austria", went to his brother Ferdinand

Ferdinand is a Germanic name composed of the elements "journey, travel", Proto-Germanic , abstract noun from root "to fare, travel" (PIE , "to lead, pass over"), and "courage" or "ready, prepared" related to Old High German "to risk, ventu ...

, who was also elected Holy Roman Emperor

The Holy Roman Emperor, originally and officially the Emperor of the Romans (disambiguation), Emperor of the Romans (; ) during the Middle Ages, and also known as the Roman-German Emperor since the early modern period (; ), was the ruler and h ...

. His son Philip II of Spain

Philip II (21 May 152713 September 1598), sometimes known in Spain as Philip the Prudent (), was King of Spain from 1556, King of Portugal from 1580, and King of Naples and List of Sicilian monarchs, Sicily from 1554 until his death in 1598. He ...

, who married Mary I of England

Mary I (18 February 1516 – 17 November 1558), also known as Mary Tudor, was Queen of England and Ireland from July 1553 and Queen of Spain as the wife of King Philip II from January 1556 until her death in 1558. She made vigorous ...

in July 1554, already ruled the Spanish Netherlands

The Spanish Netherlands (; ; ; ) (historically in Spanish: , the name "Flanders" was used as a '' pars pro toto'') was the Habsburg Netherlands ruled by the Spanish branch of the Habsburgs from 1556 to 1714. They were a collection of States of t ...

and Milan

Milan ( , , ; ) is a city in northern Italy, regional capital of Lombardy, the largest city in Italy by urban area and the List of cities in Italy, second-most-populous city proper in Italy after Rome. The city proper has a population of nea ...

in his own right. To these possessions were added the Spanish Empire

The Spanish Empire, sometimes referred to as the Hispanic Monarchy (political entity), Hispanic Monarchy or the Catholic Monarchy, was a colonial empire that existed between 1492 and 1976. In conjunction with the Portuguese Empire, it ushered ...

, Naples

Naples ( ; ; ) is the Regions of Italy, regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 908,082 within the city's administrative limits as of 2025, while its Metropolitan City of N ...

, Sicily

Sicily (Italian language, Italian and ), officially the Sicilian Region (), is an island in the central Mediterranean Sea, south of the Italian Peninsula in continental Europe and is one of the 20 regions of Italy, regions of Italy. With 4. ...

, and Sardinia

Sardinia ( ; ; ) is the Mediterranean islands#By area, second-largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after Sicily, and one of the Regions of Italy, twenty regions of Italy. It is located west of the Italian Peninsula, north of Tunisia an ...

.

This division was driven by the administrative complexity of managing the two empires as a single entity, but also reflected strategic differences. While Spain was a global maritime superpower, the Austrian Habsburgs focused on securing a pre-eminent position in Germany and managing the threat posed by the

This division was driven by the administrative complexity of managing the two empires as a single entity, but also reflected strategic differences. While Spain was a global maritime superpower, the Austrian Habsburgs focused on securing a pre-eminent position in Germany and managing the threat posed by the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

. A second area of divergence was how to respond to the Reformation

The Reformation, also known as the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation, was a time of major Theology, theological movement in Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the p ...

, and growth of Protestantism

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that emphasizes Justification (theology), justification of sinners Sola fide, through faith alone, the teaching that Salvation in Christianity, salvation comes by unmerited Grace in Christianity, divin ...

. In Germany, conflict between Lutheran

Lutheranism is a major branch of Protestantism that emerged under the work of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German friar and Protestant Reformers, reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practices of the Catholic Church launched ...

and Catholic

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

princes resulted in the 1552 Second Schmalkaldic War, settled by the 1556 Peace of Augsburg.

Unlike Ferdinand, who favoured compromise with his Protestant subjects, Charles and Philip responded to the rise of Calvinism

Reformed Christianity, also called Calvinism, is a major branch of Protestantism that began during the 16th-century Protestant Reformation. In the modern day, it is largely represented by the Continental Reformed Christian, Presbyteri ...

in the Spanish Netherlands

The Spanish Netherlands (; ; ; ) (historically in Spanish: , the name "Flanders" was used as a '' pars pro toto'') was the Habsburg Netherlands ruled by the Spanish branch of the Habsburgs from 1556 to 1714. They were a collection of States of t ...

with repression, a policy that eventually led to the Dutch War of Independence

The Eighty Years' War or Dutch Revolt (; 1566/1568–1648) was an armed conflict in the Habsburg Netherlands between disparate groups of rebels and the Spanish government. The causes of the war included the Reformation, centralisation, ex ...

in 1568. Although the two Habsburg branches cooperated when their aims converged, Ferdinand was more focused on restoring order to the Empire, and dealing with the Ottomans

Ottoman may refer to:

* Osman I, historically known in English as "Ottoman I", founder of the Ottoman Empire

* Osman II, historically known in English as "Ottoman II"

* Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empir ...

. Philip kept fighting, but recognised peace with France would enable him to deal with the rebellious Dutch. Victories at St Quentin in 1557 and Gravelines

Gravelines ( , ; ) is a Communes of France, commune in the Nord (French department), Nord departments of France, department in Northern France. It lies at the mouth of the river Aa (France), Aa southwest of Dunkirk, France, Dunkirk. It was form ...

in August 1558 allowed him to negotiate from strength.

Despite these successes, Philip was struggling to finance the war, and in December 1558 advised his commander in Flanders, Emmanuel Philibert, that he could no longer pay his troops. Similar problems meant Henry II of France was also willing to reach an agreement, especially after France occupied the Three Bishoprics in 1552, and recaptured Calais in January 1558. In addition, internal divisions caused by the rise of Protestantism in France exacerbated splits within the nobility, and led to the outbreak of the

Despite these successes, Philip was struggling to finance the war, and in December 1558 advised his commander in Flanders, Emmanuel Philibert, that he could no longer pay his troops. Similar problems meant Henry II of France was also willing to reach an agreement, especially after France occupied the Three Bishoprics in 1552, and recaptured Calais in January 1558. In addition, internal divisions caused by the rise of Protestantism in France exacerbated splits within the nobility, and led to the outbreak of the French Wars of Religion

The French Wars of Religion were a series of civil wars between French Catholic Church, Catholics and Protestantism, Protestants (called Huguenots) from 1562 to 1598. Between two and four million people died from violence, famine or disease di ...

in 1562.

Finally, England

England is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is located on the island of Great Britain, of which it covers about 62%, and List of islands of England, more than 100 smaller adjacent islands. It ...

was also anxious to end the war, which it entered in alliance with Spain and was widely seen as a disastrous decision. The capture of Calais after more than 200 years severely damaged English prestige and deprived them of a bridgehead which had allowed English troops to cross the English Channel

The English Channel, also known as the Channel, is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that separates Southern England from northern France. It links to the southern part of the North Sea by the Strait of Dover at its northeastern end. It is the busi ...

and intervene in mainland Europe with relative ease.

Negotiations

Marck and Vaucelles

After three years of war, both the French and Spanish courts were making overtures for peace talks as early as November 1554. The first serious Franco-Spanish peace negotiations, although preliminary, were held at the Conference of Marck within thePale of Calais

The Pale of Calais was a territory in northern France ruled by the monarchs of England from 1347 to 1558. The area, which centred on Calais, was taken following the Battle of Crécy in 1346 and the subsequent Siege of Calais (1346–47), Siege o ...

– on then-neutral English soil – in June 1555. However, both sides made mistakes and the conference was a failure; they wanted peace, but were not ready for reconciliation yet. The failure caused both kings to desire revenge, but as their armies and finances were exhausted, they remained on the defensive and the military situation barely changed. By October 1555, diplomacy had resumed, and the Truce of Vaucelles was agreed on 5 February 1556, somewhat favourable to France. But rather than a step towards peace, Vaucelles proved to be but a lull in the war; continued desire for revenge led to numerous incidents during the negotiations, and the stipulations of the truce were never fully implemented and observed before war resumed in September 1556 with the Spanish invasion of the pro-French Papal States.

Initially, there were attempts on both sides to limit the conflict to the Papal States, but by December 1556, preparations were made for a resumption of hostilities on all fronts, and on 6 January 1557 Gaspard II de Coligny (French governor of Picardy) launched surprise attacks on Douai and Lens in the Spanish Netherlands. The Spanish victory in the Battle of St. Quentin (1557) (10–27 August) turned out to be decisive; while England had entered the war on Spain's side, France lost one ally after the other, including the Pope, who signed a separate peace on 12 September 1557. However, Henry managed to surprise friend and foe by conquering Calais in January 1558, and negotiated a marriage between Mary, Queen of Scots

Mary, Queen of Scots (8 December 1542 – 8 February 1587), also known as Mary Stuart or Mary I of Scotland, was List of Scottish monarchs, Queen of Scotland from 14 December 1542 until her forced abdication in 1567.

The only surviving legit ...

and his son Francis (19 April 1558); although not quite able to make up for his loss at St. Quentin, it allowed Henry to save face and obtain a better position at the negotiation table.

Marcoing

Peace talks between Spain, England and France began in early 1558, but little progress was made; France refused to contemplate Mary's demand for the return of Calais, and her marriage to Philip made it difficult for England to negotiate separately. The Franco-Spanish talks at Marcoing near Cambrai, initiated by France, lasted just three days (15–17 May 1558) and came to nothing, mostly because the Siege of Thionville (1558) was ongoing, Granvelle sought to gain time by negotiations to allow the Spanish army in the Netherlands to prepare for war, and both parties could not find diplomatic common ground.Cercamp and Cateau

* Presiding negotiator:

* Presiding negotiator: Christina of Denmark

Christina of Denmark (; November 1521 – 10 December 1590) was a Denmark, Danish princess, the younger surviving daughter of Christian II, King Christian II of Denmark and Norway and Isabella of Austria. By her two marriages, she became List ...

, former Duchess consort of Lorraine (1544–1545)

* Chief Spanish negotiator: Antoine Perrenot de Granvelle

** Other Spanish negotiators: Fernando Álvarez de Toledo, 3rd Duke of Alba; William I, Prince of Orange; Ruy Gómez de Silva, 1st Prince of Éboli

* Chief French negotiator: Anne de Montmorency

** Other French negotiators: Jacques d'Albon, Marquis of Fronsac; Charles de Guise, Cardinal of Lorraine; Jean de Morvilliers, bishop of Orléans; and the French secretary of state Claude de l'Aubespine

* Chief English negotiator: Henry Fitzalan, 12th Earl of Arundel

Henry Fitzalan, 12th Earl of Arundel (23 April 151224 February 1580) was an English nobleman, who over his long life assumed a prominent place at the court of all the later Tudor sovereigns.

Court career under Henry VIII

He was the only s ...

** Other English negotiators: Thomas Thirlby, bishop of Ely; Nicholas Wotton

Nicholas Wotton (c. 1497 – 26 January 1567) was an England, English diplomat, cleric and courtier. He served as Dean of York and Royal Envoy to Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor.

Life

He was a son of Sir Robert Wotton of Boughton Malherbe, Kent ...

, the dean of Canterbury and York; and William Howard, 1st Baron Howard of Effingham

* Ambassadors of other states not directly involved in the negotiations were not permitted to attend; this especially disadvantaged Italian states, because decisions about their futures were made.

Haan (2010) concluded that the negotiations from October 1558 to April 1559 focused on three major unresolved issues:

# The fate of the Pale of Calais

The Pale of Calais was a territory in northern France ruled by the monarchs of England from 1347 to 1558. The area, which centred on Calais, was taken following the Battle of Crécy in 1346 and the subsequent Siege of Calais (1346–47), Siege o ...

(owned by England, but occupied by France).

# The fate of the territories in the north-west of Italy (i.e. Piedmont, Montferrat and the Duchy of Milan).

# The restitution of the places of Picardy (mainly St. Quentin, Le Catelet and Ham, owned by France, but occupied by Spain).

The last two rounds of peace talks that eventually led to the Treaty of Cateau-Cambrésis began at the Cistercian monastery of Cercamp near Frévent (12 October – 26 November 1558), followed by Le Cateau-Cambrésis (10 February – 3 April 1559). Large formal meetings were held in Christina's lodgings, while informal talks were held in the diplomats' own quarters or on their way to meals. On 17 October, the Spanish and French agreed to an armistice for the remainder of that month of October. On 1 December 1558, the parties at Cercamp agreed to renew the ceasefire '...as it was first agreed on the 17th day of last October, as is said, until midnight of the last day of next January...', and on 6 February 1559 at Le Cateau-Cambrésis they prolonged the truce (then set to expire on 10 February) indefinitely 'for all the time that they are in this Negotiation, and six days after the separation of this Assembly...'.

The French plenipotentiaries intended to recover St. Quentin, Le Catelet and Ham, to keep Calais, and to maintain solid positions in northern Italy; they were willing to surrender the Duchy of Milan for proper compensation, and to compromise in the Duchy of Savoy as long as it left France with a couple of strong fortified places. The Spanish delegates demanded that Henry II abandon all his (claimed) possessions in Italy (Piedmont, Corsica, the Republic of Siena, and part of Montferrat), and they used the Spanish-occupied places in Picardy as bargaining material to achieve this goal. Emmanuel Philibert stated he was willing to surrender only four places to France, and otherwise reclaim the entire Savoyard territory for himself. The English and French made equally categorical claims to legitimate possession of Calais, and the Spanish were determined to support their English allies as long as it would not lead them to fail to achieve peace with France.

Mary's death in November 1558 and the succession of her Protestant half-sister Elizabeth I of England

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was Queen of England and Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. She was the last and longest reigning monarch of the House of Tudor. Her eventful reign, and its effect on history ...

changed the Anglo-French dynamic. The new regime needed peace and stability more than Calais, while France had leverage in the form of the 16-year-old Catholic wife of the future Francis II of France, Mary, Queen of Scots

Mary, Queen of Scots (8 December 1542 – 8 February 1587), also known as Mary Stuart or Mary I of Scotland, was List of Scottish monarchs, Queen of Scotland from 14 December 1542 until her forced abdication in 1567.

The only surviving legit ...

, who also had a claim to the English throne. This opened the possibility of a separate Anglo-French peace and in December a new English envoy, Nicholas Wotton

Nicholas Wotton (c. 1497 – 26 January 1567) was an England, English diplomat, cleric and courtier. He served as Dean of York and Royal Envoy to Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor.

Life

He was a son of Sir Robert Wotton of Boughton Malherbe, Kent ...

, arrived in France to hold informal talks separate from those in Le Cateau. Since both sides recognised English security depended upon Philip's continued goodwill, finding a way to address this issue was crucial if they were to reach a deal. Although Elizabeth continued to press for the return of Calais, she could not afford to continue fighting simply to achieve that objective and the French were well aware of that reality.

Despite attempts to keep the negotiations secret, his spies kept Philip informed on their progress; although he disliked Elizabeth's religion, having the half-French Mary on the English throne would be far worse, even if she was a Catholic. If England was about to settle, it was vital that Spain should not be left isolated, especially as Philip admitted in February that his desperate financial position made it a matter of urgency. While its involvement in the war was relatively minor, England played an important role in the negotiations that ended it, as did Emperor Ferdinand, whose approval was required since many of the territorial adjustments involved states that were members of the Holy Roman Empire. A preliminary peace treaty between France and Scotland on the one hand and England on the other was agreed on 12 March 1559 at Cateau-Cambrésis.

Terms

Bertrand Haan (2010) stated that, until his publication, 'the various acts making up the Treaty of Cateau-Cambrésis have never been the subject of a scientific edition made from original documents,' pointing out that Jean Dumont's ''Corps universel diplomatique'' (1728) 'remains a reference, but is based on later copies.' Haan's 2010 edition of the Franco-Spanish agreement is based on 16th-century copies and collations (the articles in the original treaties appear to have been untitled and unnumbered), as he had no access to the originals. He also included several documents accompanying the main treaty: 'a ''traité des particuliers'' concerning lands, territorial claims or the pardon of prelates, great lords and financiers', a declaration that Christoph von Roggendorf and Juan de Luna would be excluded from the treaty, and a prisoner exchange agreement between Montmorency and Alba. He decided not to publish the Anglo-French agreement, pointing out that the original copies of it have been preserved as "J 652, n° 32" in the '' Trésor des Chartes'' of the Archives Nationales and as "E 30/1123" in the "Exchequer (Treasury of Receipts)" of thePublic Record Office

The Public Record Office (abbreviated as PRO, pronounced as three letters and referred to as ''the'' PRO), Chancery Lane in the City of London, was the guardian of the national archives of the United Kingdom from 1838 until 2003, when it was m ...

(now The National Archives).

* 2 April 1559: Anglo-French treaty between queen Elizabeth I and king Henry II

** 2 April 1559: Anglo-Scottish treaty between queen Elizabeth I

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was List of English monarchs, Queen of England and List of Irish monarchs, Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. She was the last and longest reigning monarch of the House of Tudo ...

and Mary, Queen of Scots

Mary, Queen of Scots (8 December 1542 – 8 February 1587), also known as Mary Stuart or Mary I of Scotland, was List of Scottish monarchs, Queen of Scotland from 14 December 1542 until her forced abdication in 1567.

The only surviving legit ...

& the later Francis II of France

** (related) 5 July 1560: Treaty of Edinburgh between Elizabeth I and Mary, Queen of Scots & Francis II of France

* 3 April 1559: Franco-Spanish treaty between kings Henry II and Philip II

** 3 April 1559: Franco-Spanish ''traité des particuliers''

** 3 April 1559: Declaration excluding Roggendorf and Luna (3 April 1559)

** 3 April 1559: Prisoner exchange agreement between Montmorency and Alba (3 April 1559).

Franco-Spanish agreement

* Henry II of France recognised Philip II of Spain as ruler of Milan and Naples. Henry II of France renounced his hereditary claims to theDuchy of Milan

The Duchy of Milan (; ) was a state in Northern Italy, created in 1395 by Gian Galeazzo Visconti, then the lord of Milan, and a member of the important Visconti of Milan, Visconti family, which had been ruling the city since 1277. At that time, ...

(ruled by Spain and part of the Holy Roman Empire), and recognized Spanish control over the Kingdom of Naples

The Kingdom of Naples (; ; ), officially the Kingdom of Sicily, was a state that ruled the part of the Italian Peninsula south of the Papal States between 1282 and 1816. It was established by the War of the Sicilian Vespers (1282–1302). Until ...

, the Kingdom of Sicily

The Kingdom of Sicily (; ; ) was a state that existed in Sicily and the southern Italian peninsula, Italian Peninsula as well as, for a time, in Kingdom of Africa, Northern Africa, from its founding by Roger II of Sicily in 1130 until 1816. It was ...

, and the Kingdom of Sardinia

The Kingdom of Sardinia, also referred to as the Kingdom of Sardinia and Corsica among other names, was a State (polity), country in Southern Europe from the late 13th until the mid-19th century, and from 1297 to 1768 for the Corsican part of ...

.

* Henry and Philip agreed to bring about 'the convocation and celebration of a holy universal council, so necessary for the reformation and reduction of the whole Christian Church into a true unity and harmony'. (Article 2)

* Spain returned Saint Quentin, Ham, Le Catelet and other places in northern France taken during the war. (Article 11)

* Henry confirmed Charles V's 1536 transfer of the March of Montferrat to the Duchy of Mantua, ruled by Guglielmo Gonzaga (allied with Spain and part of the Holy Roman Empire). (Articles 21–22)

* France returned the island of Corsica

Corsica ( , , ; ; ) is an island in the Mediterranean Sea and one of the Regions of France, 18 regions of France. It is the List of islands in the Mediterranean#By area, fourth-largest island in the Mediterranean and lies southeast of the Metro ...

to the Republic of Genoa

The Republic of Genoa ( ; ; ) was a medieval and early modern Maritime republics, maritime republic from the years 1099 to 1797 in Liguria on the northwestern Italy, Italian coast. During the Late Middle Ages, it was a major commercial power in ...

(allied with Spain and part of the Holy Roman Empire). French and Genoese merchants were granted full access to each other's ports. (Article 24)

* France recognised the 1555 conquest of the Republic of Siena

The Republic of Siena (, ) was a historic state consisting of the city of Siena and its surrounding territory in Tuscany, Central Italy. It existed for over 400 years, from 1125 to 1555. During its existence, it gradually expanded throughout south ...

(allied with France) by the Republic of Florence (allied with Spain and part of the Holy Roman Empire) and ceded the Presidi to Philip of Spain. (Article 25)

* As part of the terms, Emmanuel Philibert, Duke of Savoy married Henry's sister Margaret of France, Duchess of Berry (1523–1574), while his eldest daughter Elisabeth of Valois (1545–1568) became Philip's third wife. (Articles 26–33)

* France withdrew from Piedmont

Piedmont ( ; ; ) is one of the 20 regions of Italy, located in the northwest Italy, Northwest of the country. It borders the Liguria region to the south, the Lombardy and Emilia-Romagna regions to the east, and the Aosta Valley region to the ...

and gave the Duchy of Savoy

The Duchy of Savoy (; ) was a territorial entity of the Savoyard state that existed from 1416 until 1847 and was a possession of the House of Savoy.

It was created when Sigismund, Holy Roman Emperor, raised the County of Savoy into a duchy f ...

–Piedmont

Piedmont ( ; ; ) is one of the 20 regions of Italy, located in the northwest Italy, Northwest of the country. It borders the Liguria region to the south, the Lombardy and Emilia-Romagna regions to the east, and the Aosta Valley region to the ...

(allied with Spain and part of the Holy Roman Empire) back to Emmanuel Philibert, Duke of Savoy due to his victory at St. Quentin. Emmanuel Philibert agreed to remain neutral in the event of future conflict. (Articles 33 to 43)

* France retained five fortresses in northern Italy: near Turin ("Thurin"), Cherasco ("Quiers"), Pinerolo (Pignerol, "Pinerol"), Chivasso ("Chivaz") and Villanova d'Asti ("Villeneufve d'Ast"). (Article 34)

* France retained the Three Bishoprics of Toul, Metz

Metz ( , , , then ) is a city in northeast France located at the confluence of the Moselle (river), Moselle and the Seille (Moselle), Seille rivers. Metz is the Prefectures in France, prefecture of the Moselle (department), Moselle Departments ...

, and Verdun

Verdun ( , ; ; ; official name before 1970: Verdun-sur-Meuse) is a city in the Meuse (department), Meuse departments of France, department in Grand Est, northeastern France. It is an arrondissement of the department.

In 843, the Treaty of V ...

, ceded by Maurice, Elector of Saxony

Maurice (21 March 1521 – 9 July 1553) was Duke (1541–47) and later Elector (1547–53) of Saxony. His clever manipulation of alliances and disputes gained the Albertine branch of the Wettin dynasty extensive lands and the electoral dignit ...

for Henry's support during the Second Schmalkaldic War in 1552. (Article 44)

Anglo-French agreement

* (Articles 7, 8 and 14) England granted France possession of thePale of Calais

The Pale of Calais was a territory in northern France ruled by the monarchs of England from 1347 to 1558. The area, which centred on Calais, was taken following the Battle of Crécy in 1346 and the subsequent Siege of Calais (1346–47), Siege o ...

(seized from England in 1558), for an initial period of eight years (Article 7). This was a mechanism to save face and although Elizabeth tried to take advantage of the civil war to negotiate its return in 1562, it remained French thereafter.

Consequences

Celebrations

Emmanuel Philibert, Duke of Savoy married Margaret of France, Duchess of Berry, the sister of Henry II of France. Philip II of Spain married Elisabeth, the daughter of Henry II of France. Often overlooked, this has been described as "the most important marriage treaty of the 16th century". During a

Emmanuel Philibert, Duke of Savoy married Margaret of France, Duchess of Berry, the sister of Henry II of France. Philip II of Spain married Elisabeth, the daughter of Henry II of France. Often overlooked, this has been described as "the most important marriage treaty of the 16th century". During a tournament

A tournament is a competition involving at least three competitors, all participating in a sport or game. More specifically, the term may be used in either of two overlapping senses:

# One or more competitions held at a single venue and concen ...

held to celebrate the peace on 1 July, King Henry was injured in a jousting

Jousting is a medieval and renaissance martial game or hastilude between two combatants either on horse or on foot. The joust became an iconic characteristic of the knight in Romantic medievalism.

The term is derived from Old French , ultim ...

accident when a sliver from the shattered lance of Gabriel Montgomery, captain of the Scottish Guard at the French court, pierced his eye and caused subdural bleeding (though it never fully entered his brain). He died ten days later on 10 July 1559. His 15-year-old son Francis II succeeded him before he too died in December 1560 and was replaced by his 10-year-old brother Charles

Charles is a masculine given name predominantly found in English language, English and French language, French speaking countries. It is from the French form ''Charles'' of the Proto-Germanic, Proto-Germanic name (in runic alphabet) or ''* ...

. The resulting political instability, combined with the sudden demobilisation of thousands of largely unpaid troops, led to the outbreak of the French Wars of Religion

The French Wars of Religion were a series of civil wars between French Catholic Church, Catholics and Protestantism, Protestants (called Huguenots) from 1562 to 1598. Between two and four million people died from violence, famine or disease di ...

in 1562 that would consume France for the next thirty years.

Territories and dynasties

By the terms of the treaties, France ended military operations in theSpanish Netherlands

The Spanish Netherlands (; ; ; ) (historically in Spanish: , the name "Flanders" was used as a '' pars pro toto'') was the Habsburg Netherlands ruled by the Spanish branch of the Habsburgs from 1556 to 1714. They were a collection of States of t ...

and the Imperial fiefs of northern Italy and brought an end to most of the French occupation in Corsica, Tuscany and Piedmont. England and the Habsburgs, in exchange, ended their opposition to French occupation of the Pale of Calais

The Pale of Calais was a territory in northern France ruled by the monarchs of England from 1347 to 1558. The area, which centred on Calais, was taken following the Battle of Crécy in 1346 and the subsequent Siege of Calais (1346–47), Siege o ...

, the Three Bishoprics and a number of fortresses. For Spain

Spain, or the Kingdom of Spain, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe with territories in North Africa. Featuring the Punta de Tarifa, southernmost point of continental Europe, it is the largest country in Southern Eur ...

, despite no new gains and the restoration of some occupied territories to France, the peace was a positive result by confirming its control of the Habsburg Netherlands

Habsburg Netherlands were the parts of the Low Countries that were ruled by sovereigns of the Holy Roman Empire's House of Habsburg. This rule began in 1482 and ended for the Northern Netherlands in 1581 and for the Southern Netherlands in 1797. ...

, the Duchy of Milan

The Duchy of Milan (; ) was a state in Northern Italy, created in 1395 by Gian Galeazzo Visconti, then the lord of Milan, and a member of the important Visconti of Milan, Visconti family, which had been ruling the city since 1277. At that time, ...

, and the Kingdoms of Sardinia, Naples, and Sicily. Ferdinand I left the Three Bishoprics under French occupation, but the Netherlands and most of northern Italy remained part of the Holy Roman Empire in the form of imperial fiefs. Furthermore, his position of Holy Roman Emperor was recognized by the Pope, who had refused to do so as long as the war between France and the Habsburgs continued. England fared poorly during the war, and the loss of its last stronghold on the Continent damaged its reputation.

At the end of the conflict, Italy was therefore divided between viceroyalties of the Spanish Habsburgs in the south and the formal fiefs of the Austrian Habsburgs in the north. The imperial states were ruled by the Medici in Tuscany, the Spanish Habsburgs in Milan, the Estensi in Modena, and the House of Savoy

The House of Savoy (, ) is a royal house (formally a dynasty) of Franco-Italian origin that was established in 1003 in the historical region of Savoy, which was originally part of the Kingdom of Burgundy and now lies mostly within southeastern F ...

in Piedmont (which moved its capital to Turin

Turin ( , ; ; , then ) is a city and an important business and cultural centre in northern Italy. It is the capital city of Piedmont and of the Metropolitan City of Turin, and was the first Italian capital from 1861 to 1865. The city is main ...

in 1562). The Kingdoms of Naples, Sicily and Sardinia were under direct rule of the Spanish Habsburgs. The situation continued until the European wars of succession of the 18th century, when northern Italy passed to the Austrian house of Habsburg-Lorraine

The House of Habsburg-Lorraine () originated from the marriage in 1736 of Francis I, Holy Roman Emperor, Francis III, Duke of Lorraine and Bar, and Maria Theresa of Habsburg monarchy, Austria, later successively List of Bohemian monarchs, Queen ...

, and southern Italy passed to the Spanish Bourbons. The Treaty of Cateau-Cambrésis, by bringing Italy into a long period of peace and economic stability (which critics call stagnation) marks the end of the Italian Renaissance and the transition to the Baroque (Vivaldi

Antonio Lucio Vivaldi (4 March 1678 – 28 July 1741) was an Italian composer, virtuoso violinist, impresario of Baroque music and Roman Catholic priest. Regarded as one of the greatest Baroque composers, Vivaldi's influence during his lif ...

, Bernini, Caravaggio

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio (also Michele Angelo Merigi or Amerighi da Caravaggio; 29 September 1571 – 18 July 1610), known mononymously as Caravaggio, was an Italian painter active in Rome for most of his artistic life. During the fina ...

,... but also Vico, Bruno, Galileo

Galileo di Vincenzo Bonaiuti de' Galilei (15 February 1564 – 8 January 1642), commonly referred to as Galileo Galilei ( , , ) or mononymously as Galileo, was an Italian astronomer, physicist and engineer, sometimes described as a poly ...

).

Religion

Some historians have claimed that all signatories of the treaty needed to 'purge their lands of heresy'; in other words, all their subjects had to be forcefully reverted to Catholicism. Visconti (2003), for example, claimed that when pressured bySpain

Spain, or the Kingdom of Spain, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe with territories in North Africa. Featuring the Punta de Tarifa, southernmost point of continental Europe, it is the largest country in Southern Eur ...

to implement this obligation, Emmanuel Philibert, Duke of Savoy proclaimed the Edict of Nice (15 February 1560), prohibiting Protestantism on pains of a large fine, enslavement or banishment, which soon led to an armed revolt by the Protestant Waldensians

The Waldensians, also known as Waldenses (), Vallenses, Valdesi, or Vaudois, are adherents of a church tradition that began as an ascetic movement within Western Christianity before the Reformation. Originally known as the Poor of Lyon in the l ...

in his domain that would last until July 1561.

However, modern historians disagree about the primary motives of Philip II of Spain and especially Henry II of France to conclude the peace treaty. Because Henry II had told the Parlement of Paris that the fight against heresy required all his strength, and he needed to establish peace with Spain, Lucien Romier (1910) argued that besides the great financial troubles, 'that the religious motive of Henry had great, if not decisive, weight'. According to Rainer Babel (2021), that was 'a judgement which later research, with some nuances in detail, has not refuted', but he stated that Bertrand Haan (2010) had 'a deviating interpretation' challenging this consensus. Haan (2010) argued that finances were more important than domestic religious dissension; the fact that the latter was prominent in the 1560s in both France and Spain may have led historians astray in emphasising the role of religion in the 1559 treaty.

Megan Williams (2011) summarised: 'Indeed, Haan contends, it was not the treaty itself but its subsequent justifications which stoked French religious strife. The treaty's priority, he argues, was not a Catholic alliance to extirpate heresy but the affirmation of its signatories' honor and amity, consecrated by a set of dynastic marriages'. According to Haan, there is no evidence of a Catholic alliance between France and Spain to eradicate Protestantism even though some contemporaries have pointed to the treaty's second article to argue such an agreement existed: 'The second article expresses the wish to convene an oecumenical council. People, the contemporaries first, have concluded that the agreement sealed the establishment of a united front of Philip II and Henry II against Protestantism in their states as in Europe. The analysis of the progress of the talks shows that this was not the case'.

Pope Pius V raised the Florentine duke Cosimo de' Medici to Grand Duke of Tuscany

Grand may refer to:

People with the name

* Grand (surname)

* Grand L. Bush (born 1955), American actor

Places

* Grand, Oklahoma, USA

* Grand, Vosges, village and commune in France with Gallo-Roman amphitheatre

* Grand County (disambiguation), se ...

in 1569, which was confirmed by the emperor although Philip II of Spain disapproved. Although the papacy's diplomatic role increased during the Wars of Religion, popes and papal legates played no role in negotiating the most significant truces and treaties between the Habsburg and Valois monarchs during these wars.

Notes

References

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *External links

Photocopies of the Franco-Spanish Treaty of Cateau-Cambrésis in the original Spanish text

– ieg-friedensvertraege.de Leibniz Institute for European History {{Authority control 1559 in England 1559 in Italy 1559 in France 1559 in Spain 1559 in the Holy Roman Empire Cateau-Cambrésis Cateau-Cambrésis Cateau-Cambrésis Cateau-Cambrésis Henry II of France Ferdinand I, Holy Roman Emperor Philip II of Spain Elizabeth I Italian War of 1551–1559