Thomas Carlyle on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

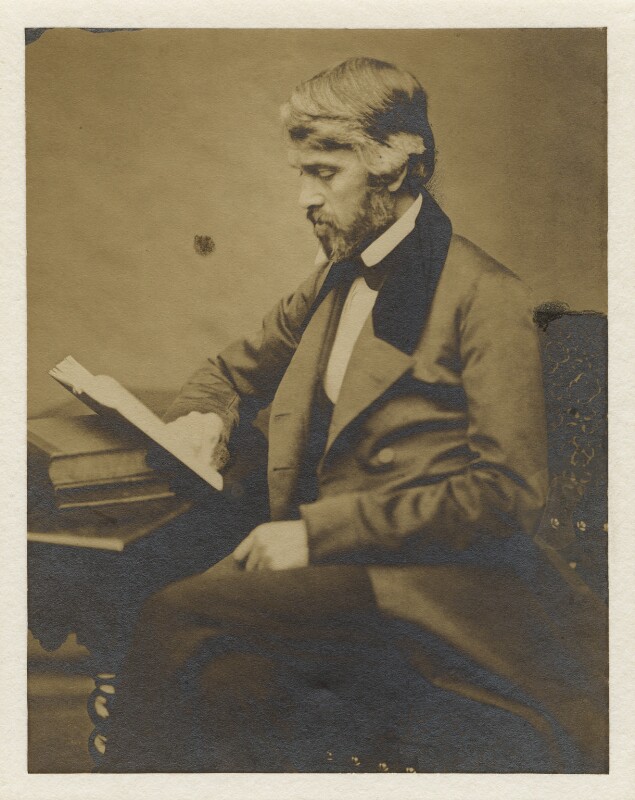

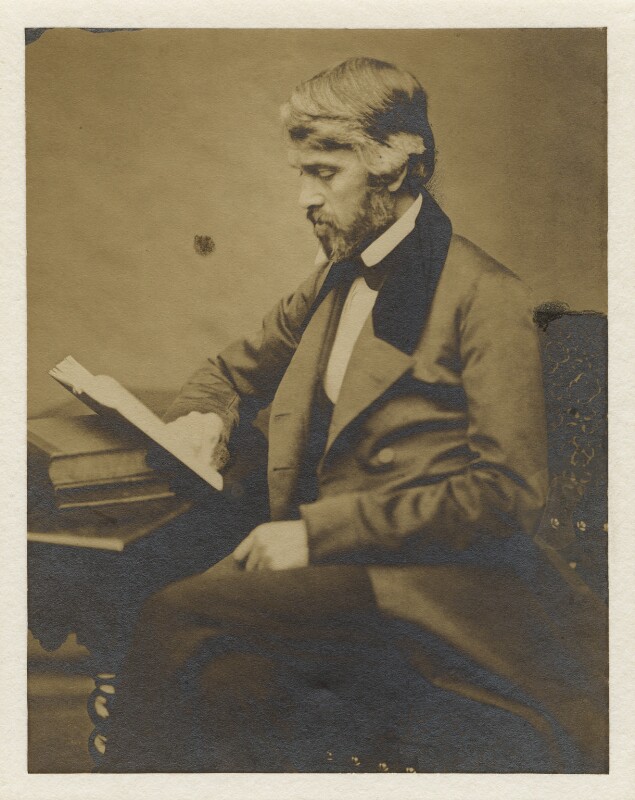

Thomas Carlyle (4 December 17955 February 1881) was a Scottish essayist, historian and philosopher. A leading writer of the Victorian era, he exerted a profound influence on 19th-century art, literature and philosophy.

Born in Ecclefechan, Dumfriesshire, Carlyle attended the University of Edinburgh where he excelled in mathematics, inventing the Carlyle circle. After finishing the arts course, he prepared to become a minister in the Burgher Church while working as a schoolmaster. He quit these and several other endeavours before settling on literature, writing for the '' Edinburgh Encyclopædia'' and working as a translator. He found initial success as a disseminator of

Thomas Carlyle (4 December 17955 February 1881) was a Scottish essayist, historian and philosopher. A leading writer of the Victorian era, he exerted a profound influence on 19th-century art, literature and philosophy.

Born in Ecclefechan, Dumfriesshire, Carlyle attended the University of Edinburgh where he excelled in mathematics, inventing the Carlyle circle. After finishing the arts course, he prepared to become a minister in the Burgher Church while working as a schoolmaster. He quit these and several other endeavours before settling on literature, writing for the '' Edinburgh Encyclopædia'' and working as a translator. He found initial success as a disseminator of

Thomas Carlyle was born on 4 December 1795 to James (1758–1832) and Margaret Aitken Carlyle (1771–1853) in the village of Ecclefechan in Dumfriesshire in southwest Scotland. Nicholas Carlisle traced Carlyle's ancestry back to Margaret Bruce, sister of

Thomas Carlyle was born on 4 December 1795 to James (1758–1832) and Margaret Aitken Carlyle (1771–1853) in the village of Ecclefechan in Dumfriesshire in southwest Scotland. Nicholas Carlisle traced Carlyle's ancestry back to Margaret Bruce, sister of

In November 1809 at nearly fourteen years of age, Carlyle walked one hundred miles from his home in order to attend the University of Edinburgh (), where he studied mathematics with John Leslie, science with John Playfair and moral philosophy with Thomas Brown. He gravitated to mathematics and geometry and displayed great talent in those subjects, being credited with the invention of the Carlyle circle. In the University library, he read many important works of eighteenth-century and contemporary history, philosophy, and '' belles-lettres''. He began expressing religious scepticism around this time, asking his mother to her horror, "Did God Almighty come down and make wheelbarrows in a shop?" In 1813 he completed his arts curriculum and enrolled in a theology course at Divinity Hall the following academic year. This was to be the preliminary of a ministerial career.

Carlyle began teaching at Annan Academy in June 1814. He gave his first trial sermons in December 1814 and December 1815, both of which are lost. By the summer of 1815 he had taken an interest in

In November 1809 at nearly fourteen years of age, Carlyle walked one hundred miles from his home in order to attend the University of Edinburgh (), where he studied mathematics with John Leslie, science with John Playfair and moral philosophy with Thomas Brown. He gravitated to mathematics and geometry and displayed great talent in those subjects, being credited with the invention of the Carlyle circle. In the University library, he read many important works of eighteenth-century and contemporary history, philosophy, and '' belles-lettres''. He began expressing religious scepticism around this time, asking his mother to her horror, "Did God Almighty come down and make wheelbarrows in a shop?" In 1813 he completed his arts curriculum and enrolled in a theology course at Divinity Hall the following academic year. This was to be the preliminary of a ministerial career.

Carlyle began teaching at Annan Academy in June 1814. He gave his first trial sermons in December 1814 and December 1815, both of which are lost. By the summer of 1815 he had taken an interest in

Carlyle wrote several articles in July, August and September, and in November began a translation of Adrien-Marie Legendre">Adrien Marie Legendre

Adrien-Marie Legendre (; ; 18 September 1752 – 9 January 1833) was a French mathematician who made numerous contributions to mathematics. Well-known and important concepts such as the Legendre polynomials and Legendre transformation are named ...

Carlyle wrote several articles in July, August and September, and in November began a translation of Adrien-Marie Legendre">Adrien Marie Legendre

Adrien-Marie Legendre (; ; 18 September 1752 – 9 January 1833) was a French mathematician who made numerous contributions to mathematics. Well-known and important concepts such as the Legendre polynomials and Legendre transformation are named ...

's ''Elements of Geometry''. In January 1822, Carlyle wrote "Goethe's Faust" for the ''New Edinburgh Review'', and shortly afterwards began a tutorship for the distinguished Buller family, tutoring Charles Buller and his brother Arthur William Buller until July; he would work for the family until July 1824. Carlyle completed the Legendre translation in July 1822, having prefixed his own essay "On Proportion", which Augustus De Morgan later called "as good a substitute for the fifth Book of Euclid as could have been given in that space". Carlyle's translation of Goethe's '' Wilhelm Meister's Apprenticeship'' (1824) and '' Travels'' (1825) and his biography of Schiller (1825) brought him a decent income, which had before then eluded him, and he garnered a modest reputation. He began corresponding with Goethe and made his first trip to London in 1824, meeting with prominent writers such as Thomas Campbell, Charles Lamb, and Samuel Taylor Coleridge, and gaining friendships with Anna Montagu, Bryan Waller Proctor, and Henry Crabb Robinson. He also travelled to Paris in October–November with Edward Strachey and

In October 1826, Thomas and Jane Carlyle were married at the Welsh family farm in Templand. Shortly after their marriage, the Carlyles moved into a modest home on Comely Bank in Edinburgh, that had been leased for them by Jane's mother. They lived there from October 1826 to May 1828. In that time, Carlyle published ''German Romance'', began ''Wotton Reinfred'', an autobiographical novel which he left unfinished, and published his first article for the '' Edinburgh Review'', "

In October 1826, Thomas and Jane Carlyle were married at the Welsh family farm in Templand. Shortly after their marriage, the Carlyles moved into a modest home on Comely Bank in Edinburgh, that had been leased for them by Jane's mother. They lived there from October 1826 to May 1828. In that time, Carlyle published ''German Romance'', began ''Wotton Reinfred'', an autobiographical novel which he left unfinished, and published his first article for the '' Edinburgh Review'', " In May 1828, the Carlyles moved to Craigenputtock, the main house of Jane's modest agricultural estate in Dumfriesshire, which they occupied until May 1834. He wrote a number of essays there which earned him money and augmented his reputation, including "Life and Writings of

In May 1828, the Carlyles moved to Craigenputtock, the main house of Jane's modest agricultural estate in Dumfriesshire, which they occupied until May 1834. He wrote a number of essays there which earned him money and augmented his reputation, including "Life and Writings of  Most notably, he wrote ''

Most notably, he wrote ''

Carlyle eventually decided to publish ''Sartor'' serially in '' Fraser's Magazine'', with the instalments appearing between November 1833 and August 1834. Despite early recognition from Emerson, Mill and others, it was generally received poorly, if noticed at all. In 1834, Carlyle applied unsuccessfully for the astronomy professorship at the Edinburgh observatory. That autumn, he arranged for the publication of a history of the

Carlyle eventually decided to publish ''Sartor'' serially in '' Fraser's Magazine'', with the instalments appearing between November 1833 and August 1834. Despite early recognition from Emerson, Mill and others, it was generally received poorly, if noticed at all. In 1834, Carlyle applied unsuccessfully for the astronomy professorship at the Edinburgh observatory. That autumn, he arranged for the publication of a history of the  During Carlyle's lecture series, '' The French Revolution: A History'' was officially published. It marked his career breakthrough. At the end of the year, Carlyle reported to Karl August Varnhagen von Ense that his earlier efforts to popularise German literature were beginning to produce results, and expressed his satisfaction: "''Deutschland'' will reclaim her great Colony; we shall become more ''Deutsch'', that is to say more ''English'', at same time." ''The French Revolution'' fostered the republication of ''Sartor Resartus'' in London in 1838 as well as a collection of his earlier writings in the form of the '' Critical and Miscellaneous Essays'', facilitated in Boston with the aid of Emerson. Carlyle presented his second lecture series in April and June 1838 on the history of literature at the Marylebone Institution in Portman Square. '' The Examiner'' reported that at the end of the second lecture, "Mr. Carlyle was heartily greeted with applause." Carlyle felt that they "went on better and better, and grew at last, or threatened to grow, quite a flaming affair." He published two essays in 1838, "Sir Walter Scott", being a review of John Gibson Lockhart's biography, and "Varnhagen von Ense's Memoirs". In April 1839, Carlyle published "Petition on the Copyright Bill". A third series of lectures was given in May on the revolutions of modern Europe, which the ''Examiner'' reviewed positively, noting after the third lecture that "Mr. Carlyle's audiences appear to increase in number every time." Carlyle wrote to his mother that the lectures were met "with very kind acceptance from people more distinguished than ever; yet still with a feeling that I was far from the ''right'' lecturing point yet." In July, he published "On the Sinking of the Vengeur" and in December he published ''Chartism'', a pamphlet in which he addressed the movement of the same name and raised the Condition-of-England question.

During Carlyle's lecture series, '' The French Revolution: A History'' was officially published. It marked his career breakthrough. At the end of the year, Carlyle reported to Karl August Varnhagen von Ense that his earlier efforts to popularise German literature were beginning to produce results, and expressed his satisfaction: "''Deutschland'' will reclaim her great Colony; we shall become more ''Deutsch'', that is to say more ''English'', at same time." ''The French Revolution'' fostered the republication of ''Sartor Resartus'' in London in 1838 as well as a collection of his earlier writings in the form of the '' Critical and Miscellaneous Essays'', facilitated in Boston with the aid of Emerson. Carlyle presented his second lecture series in April and June 1838 on the history of literature at the Marylebone Institution in Portman Square. '' The Examiner'' reported that at the end of the second lecture, "Mr. Carlyle was heartily greeted with applause." Carlyle felt that they "went on better and better, and grew at last, or threatened to grow, quite a flaming affair." He published two essays in 1838, "Sir Walter Scott", being a review of John Gibson Lockhart's biography, and "Varnhagen von Ense's Memoirs". In April 1839, Carlyle published "Petition on the Copyright Bill". A third series of lectures was given in May on the revolutions of modern Europe, which the ''Examiner'' reviewed positively, noting after the third lecture that "Mr. Carlyle's audiences appear to increase in number every time." Carlyle wrote to his mother that the lectures were met "with very kind acceptance from people more distinguished than ever; yet still with a feeling that I was far from the ''right'' lecturing point yet." In July, he published "On the Sinking of the Vengeur" and in December he published ''Chartism'', a pamphlet in which he addressed the movement of the same name and raised the Condition-of-England question.

In May 1840, Carlyle gave his fourth and final set of lectures, which were published in 1841 as '' On Heroes, Hero-Worship, & the Heroic in History.'' Carlyle wrote to his brother John afterwards, "The Lecturing business went of 'sic''with sufficient ''éclat;'' the Course was generally judged, and I rather join therein myself, to be the bad ''best'' I have yet given." In the 1840 edition of the ''Essays'', Carlyle published "Fractions", a collection of poems written from 1823 to 1833. Later that year, he declined a proposal for a professorship of history at Edinburgh. Carlyle was the principal founder of the London Library in 1841. He had become frustrated by the facilities available at the British Museum Library, where he was often unable to find a seat (obliging him to perch on ladders), where he complained that the enforced close confinement with his fellow readers gave him a "museum headache", where the books were unavailable for loan, and where he found the library's collections of pamphlets and other material relating to the French Revolution and English Civil Wars inadequately catalogued. In particular, he developed an antipathy to the Keeper of Printed Books, Anthony Panizzi (despite the fact that Panizzi had allowed him many privileges not granted to other readers), and criticised him in a footnote to an article published in the ''

In May 1840, Carlyle gave his fourth and final set of lectures, which were published in 1841 as '' On Heroes, Hero-Worship, & the Heroic in History.'' Carlyle wrote to his brother John afterwards, "The Lecturing business went of 'sic''with sufficient ''éclat;'' the Course was generally judged, and I rather join therein myself, to be the bad ''best'' I have yet given." In the 1840 edition of the ''Essays'', Carlyle published "Fractions", a collection of poems written from 1823 to 1833. Later that year, he declined a proposal for a professorship of history at Edinburgh. Carlyle was the principal founder of the London Library in 1841. He had become frustrated by the facilities available at the British Museum Library, where he was often unable to find a seat (obliging him to perch on ladders), where he complained that the enforced close confinement with his fellow readers gave him a "museum headache", where the books were unavailable for loan, and where he found the library's collections of pamphlets and other material relating to the French Revolution and English Civil Wars inadequately catalogued. In particular, he developed an antipathy to the Keeper of Printed Books, Anthony Panizzi (despite the fact that Panizzi had allowed him many privileges not granted to other readers), and criticised him in a footnote to an article published in the ''

Carlyle visited Ireland in 1846 with Charles Gavan Duffy for a companion and guide, and wrote a series of brief articles on the Irish question in 1848. These were "Ireland and the British Chief Governor", "Irish Regiments (of the New Æra)", and "The Repeal of the Union", each of which offered solutions to Ireland's problems and argued to preserve England's connection with Ireland. Carlyle wrote an article titled "Ireland and Sir Robert Peel" (signed "C.") published in April 1849 in '' The Spectator'' in response to two speeches given by Peel wherein he made many of the same proposals which Carlyle had earlier suggested; he called the speeches "like a prophecy of better things, inexpressibly cheering." In May, he published "Indian Meal", in which he advanced maize as a remedy to the Great Famine as well as the worries of "disconsolate Malthusians". He visited Ireland again with Duffy later that year while recording his impressions in his letters and a series of memoranda, published as ''Reminiscences of My Irish Journey in 1849'' after his death; Duffy would publish his own memoir of their travels, ''Conversations with Carlyle''.

Carlyle's travels in Ireland deeply affected his views on society, as did the Revolutions of 1848. While embracing the latter as necessary in order to cleanse society of various forms of anarchy and misgovernment, he denounced their democratic undercurrent and insisted on the need for authoritarian leaders. These events inspired his next two works, " Occasional Discourse on the Negro Question" (1849), in which he coined the term " Dismal Science" to describe political economy, and '' Latter-Day Pamphlets'' (1850). The illiberal content of these works sullied Carlyle's reputation for some progressives, while endearing him to those that shared his views. In 1851, Carlyle wrote '' The Life of John Sterling'' as a corrective to Julius Hare's unsatisfactory 1848 biography. In late September and early October, he made his second trip to Paris, where he met

Carlyle visited Ireland in 1846 with Charles Gavan Duffy for a companion and guide, and wrote a series of brief articles on the Irish question in 1848. These were "Ireland and the British Chief Governor", "Irish Regiments (of the New Æra)", and "The Repeal of the Union", each of which offered solutions to Ireland's problems and argued to preserve England's connection with Ireland. Carlyle wrote an article titled "Ireland and Sir Robert Peel" (signed "C.") published in April 1849 in '' The Spectator'' in response to two speeches given by Peel wherein he made many of the same proposals which Carlyle had earlier suggested; he called the speeches "like a prophecy of better things, inexpressibly cheering." In May, he published "Indian Meal", in which he advanced maize as a remedy to the Great Famine as well as the worries of "disconsolate Malthusians". He visited Ireland again with Duffy later that year while recording his impressions in his letters and a series of memoranda, published as ''Reminiscences of My Irish Journey in 1849'' after his death; Duffy would publish his own memoir of their travels, ''Conversations with Carlyle''.

Carlyle's travels in Ireland deeply affected his views on society, as did the Revolutions of 1848. While embracing the latter as necessary in order to cleanse society of various forms of anarchy and misgovernment, he denounced their democratic undercurrent and insisted on the need for authoritarian leaders. These events inspired his next two works, " Occasional Discourse on the Negro Question" (1849), in which he coined the term " Dismal Science" to describe political economy, and '' Latter-Day Pamphlets'' (1850). The illiberal content of these works sullied Carlyle's reputation for some progressives, while endearing him to those that shared his views. In 1851, Carlyle wrote '' The Life of John Sterling'' as a corrective to Julius Hare's unsatisfactory 1848 biography. In late September and early October, he made his second trip to Paris, where he met

Carlyle travelled to Scotland to deliver his "Inaugural Address at Edinburgh" as Rector in April 1866. During his trip, he was accompanied by John Tyndall,

Carlyle travelled to Scotland to deliver his "Inaugural Address at Edinburgh" as Rector in April 1866. During his trip, he was accompanied by John Tyndall,  Amidst controversy over governor John Eyre's violent repression of the Morant Bay rebellion, Carlyle assumed leadership of the Eyre Defence and Aid Fund in 1865 and 1866. The Defence had convened in response to the anti-Eyre

Amidst controversy over governor John Eyre's violent repression of the Morant Bay rebellion, Carlyle assumed leadership of the Eyre Defence and Aid Fund in 1865 and 1866. The Defence had convened in response to the anti-Eyre  In the spring of 1874, Carlyle accepted the '' Pour le Mérite für Wissenschaften und Künste'' from Otto von Bismarck and declined Disraeli's offers of a state pension and the

In the spring of 1874, Carlyle accepted the '' Pour le Mérite für Wissenschaften und Künste'' from Otto von Bismarck and declined Disraeli's offers of a state pension and the

Carlyle's religious, historical and political thought has long been the subject of debate. In the 19th century, he was "an enigma" according to Ian Campbell in the '' Dictionary of Literary Biography'', being "variously regarded as sage and impious, a moral leader, a moral desperado, a radical, a conservative, a Christian." Carlyle continues to perplex scholars in the 21st century, as Kenneth J. Fielding quipped in 2005: "A problem in writing about Carlyle and his beliefs is that people think that they know what they are."

Carlyle identified two philosophical precepts. The first is derived from Novalis: "The True philosophical Act is annihilation of self (''Selbsttödtung''); this is the real beginning of all Philosophy; all requisites for being a Disciple of Philosophy point hither." The second is derived from Goethe: "It is only with Renunciation (''Entsagen'') that Life, properly speaking, can be said to begin." Through ''Selbsttödtung'' (annihilation of self), liberation from

Carlyle's religious, historical and political thought has long been the subject of debate. In the 19th century, he was "an enigma" according to Ian Campbell in the '' Dictionary of Literary Biography'', being "variously regarded as sage and impious, a moral leader, a moral desperado, a radical, a conservative, a Christian." Carlyle continues to perplex scholars in the 21st century, as Kenneth J. Fielding quipped in 2005: "A problem in writing about Carlyle and his beliefs is that people think that they know what they are."

Carlyle identified two philosophical precepts. The first is derived from Novalis: "The True philosophical Act is annihilation of self (''Selbsttödtung''); this is the real beginning of all Philosophy; all requisites for being a Disciple of Philosophy point hither." The second is derived from Goethe: "It is only with Renunciation (''Entsagen'') that Life, properly speaking, can be said to begin." Through ''Selbsttödtung'' (annihilation of self), liberation from

Carlyle revered what he called the "Bible of Universal History", a "real Prophetic Manuscript" which incorporates the poetic and the factual to show the divine reality of existence. For Carlyle, "the right interpretation of Reality and History" is the highest form of poetry, and "true History" is "the only possible

Carlyle revered what he called the "Bible of Universal History", a "real Prophetic Manuscript" which incorporates the poetic and the factual to show the divine reality of existence. For Carlyle, "the right interpretation of Reality and History" is the highest form of poetry, and "true History" is "the only possible

Thomas Carlyle (4 December 17955 February 1881) was a Scottish essayist, historian and philosopher. A leading writer of the Victorian era, he exerted a profound influence on 19th-century art, literature and philosophy.

Born in Ecclefechan, Dumfriesshire, Carlyle attended the University of Edinburgh where he excelled in mathematics, inventing the Carlyle circle. After finishing the arts course, he prepared to become a minister in the Burgher Church while working as a schoolmaster. He quit these and several other endeavours before settling on literature, writing for the '' Edinburgh Encyclopædia'' and working as a translator. He found initial success as a disseminator of

Thomas Carlyle (4 December 17955 February 1881) was a Scottish essayist, historian and philosopher. A leading writer of the Victorian era, he exerted a profound influence on 19th-century art, literature and philosophy.

Born in Ecclefechan, Dumfriesshire, Carlyle attended the University of Edinburgh where he excelled in mathematics, inventing the Carlyle circle. After finishing the arts course, he prepared to become a minister in the Burgher Church while working as a schoolmaster. He quit these and several other endeavours before settling on literature, writing for the '' Edinburgh Encyclopædia'' and working as a translator. He found initial success as a disseminator of German literature

German literature () comprises those literary texts written in the German language. This includes literature written in Germany, Austria, the German parts of Switzerland and Belgium, Liechtenstein, Luxembourg, South Tyrol in Italy and to a l ...

, then little-known to English readers, through his translations, his ''Life of'' '' Friedrich Schiller'' (1825), and his review essays for various journals. His first major work was a novel entitled ''Sartor Resartus

''Sartor Resartus: The Life and Opinions of Herr Teufelsdröckh in Three Books'' is an 1831 novel by the Scottish essayist, historian and philosopher Thomas Carlyle, first published as a serial in '' Fraser's Magazine'' in November 1833 – Augu ...

'' (1833–34). After relocating to London, he became famous with his ''French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are conside ...

'' (1837), which prompted the collection and reissue of his essays as '' Miscellanies''. Each of his subsequent works, from ''On Heroes

''On Heroes, Hero-Worship, & the Heroic in History'' is a book by the Scottish essayist, historian and philosopher Thomas Carlyle, published by James Fraser, London, in 1841. It is a collection of six lectures given in May 1840 about prominent h ...

'' (1841) to '' History of Frederick the Great'' (1858–65) and beyond, were highly regarded throughout Europe and North America. He founded the London Library, contributed significantly to the creation of the National Portrait Galleries in London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

and Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a border with England to the southeast and is otherwise surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean to th ...

, was elected Lord Rector of Edinburgh University in 1865, and received the '' Pour le Mérite'' in 1874, among other honours.

Carlyle's corpus spans the genres of history, the critical essay, social commentary, biography, fiction, and poetry. His innovative writing style, known as Carlylese, greatly influenced Victorian literature and anticipated techniques of postmodern literature. While not adhering to any formal religion, he asserted the importance of belief and developed his own philosophy of religion

Philosophy of religion is "the philosophical examination of the central themes and concepts involved in religious traditions". Philosophical discussions on such topics date from ancient times, and appear in the earliest known Text (literary theo ...

. He preached " Natural Supernaturalism", the idea that all things are "Clothes" which at once reveal and conceal the divine, that "a mystic bond of brotherhood makes all men one", and that duty, work and silence are essential. He postulated the Great Man theory, a philosophy of history which contends that history is shaped by exceptional individuals. He viewed history as a "Prophetic Manuscript" that progresses on a cyclical

Cycle, cycles, or cyclic may refer to:

Anthropology and social sciences

* Cyclic history, a theory of history

* Cyclical theory, a theory of American political history associated with Arthur Schlesinger, Sr.

* Social cycle, various cycles in soc ...

basis, analogous to the phoenix and the seasons. Raising the " Condition-of-England Question" to address the impact of the Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution was the transition to new manufacturing processes in Great Britain, continental Europe, and the United States, that occurred during the period from around 1760 to about 1820–1840. This transition included going f ...

, his political philosophy

Political philosophy or political theory is the philosophical study of government, addressing questions about the nature, scope, and legitimacy of public agents and institutions and the relationships between them. Its topics include politics, l ...

is characterised by medievalism, advocating a "Chivalry

Chivalry, or the chivalric code, is an informal and varying code of conduct developed in Europe between 1170 and 1220. It was associated with the medieval Christian institution of knighthood; knights' and gentlemen's behaviours were governed b ...

of Labour" led by " Captains of Industry". He attacked utilitarianism as mere atheism

Atheism, in the broadest sense, is an absence of belief in the existence of deities. Less broadly, atheism is a rejection of the belief that any deities exist. In an even narrower sense, atheism is specifically the position that there no ...

and egoism, criticised ''laissez-faire

''Laissez-faire'' ( ; from french: laissez faire , ) is an economic system in which transactions between private groups of people are free from any form of economic interventionism (such as subsidies) deriving from special interest groups. ...

'' political economy

Political economy is the study of how economic systems (e.g. markets and national economies) and political systems (e.g. law, institutions, government) are linked. Widely studied phenomena within the discipline are systems such as labour ...

as the " Dismal Science", and rebuked "big black Democracy

Democracy (From grc, δημοκρατία, dēmokratía, ''dēmos'' 'people' and ''kratos'' 'rule') is a form of government in which people, the people have the authority to deliberate and decide legislation ("direct democracy"), or to choo ...

" while championing "''Hero''archy (Government of Heroes)".

Carlyle occupied a central position in Victorian culture, being considered not only, in the words of Ralph Waldo Emerson

Ralph Waldo Emerson (May 25, 1803April 27, 1882), who went by his middle name Waldo, was an American essayist, lecturer, philosopher, abolitionist, and poet who led the transcendentalist movement of the mid-19th century. He was seen as a cham ...

, the "undoubted head of English letters

The alphabet for Modern English is a Latin-script alphabet consisting of 26 letters, each having an upper- and lower-case form. The word ''alphabet'' is a compound of the first two letters of the Greek alphabet, ''alpha'' and ''beta''. ...

", but a secular prophet. Posthumously, his reputation suffered as publications by his friend and disciple James Anthony Froude

James Anthony Froude ( ; 23 April 1818 – 20 October 1894) was an English historian, novelist, biographer, and editor of ''Fraser's Magazine''. From his upbringing amidst the Anglo-Catholic Oxford Movement, Froude intended to become a clergy ...

provoked controversy about Carlyle's personal life, particularly his marriage to Jane Welsh Carlyle. His reputation further declined in the 20th century, as the onsets of World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

and World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

brought forth accusations that he was a progenitor of both Prussianism and fascism

Fascism is a far-right, authoritarian, ultra-nationalist political ideology and movement,: "extreme militaristic nationalism, contempt for electoral democracy and political and cultural liberalism, a belief in natural social hierarchy and th ...

. Since the 1950s, extensive scholarship in the field of Carlyle Studies has improved his standing, and he is now recognised as "one of the enduring monuments of our literature who, quite simply, cannot be spared."

Biography

Early life

Thomas Carlyle was born on 4 December 1795 to James (1758–1832) and Margaret Aitken Carlyle (1771–1853) in the village of Ecclefechan in Dumfriesshire in southwest Scotland. Nicholas Carlisle traced Carlyle's ancestry back to Margaret Bruce, sister of

Thomas Carlyle was born on 4 December 1795 to James (1758–1832) and Margaret Aitken Carlyle (1771–1853) in the village of Ecclefechan in Dumfriesshire in southwest Scotland. Nicholas Carlisle traced Carlyle's ancestry back to Margaret Bruce, sister of Robert the Bruce

Robert I (11 July 1274 – 7 June 1329), popularly known as Robert the Bruce (Scottish Gaelic: ''Raibeart an Bruis''), was King of Scots from 1306 to his death in 1329. One of the most renowned warriors of his generation, Robert eventuall ...

. His parents were members of the Burgher secession Presbyterian church. James Carlyle was a stonemason, later a farmer, who built the Arched House

Thomas Carlyle's Birthplace is a house in Ecclefechan, Dumfries and Galloway, Scotland, UK, in which Thomas Carlyle, who was to become a pre-eminent man of letters, was born in 1795.

The house was built in 1791 by Carlyle's father James and J ...

wherein his son was born. His maxim was that "man was created to work, not to speculate, or feel, or dream." As a result of his disordered upbringing, James Carlyle became deeply religious in his youth, reading many books of sermons and doctrinal arguments throughout his life. He married his first wife in 1791, distant cousin Janet, who gave birth to John Carlyle and then died. He married Margaret Aitken in 1795, a poor farmer's daughter then working as a servant. They had nine children, of whom Thomas was the eldest. Margaret was pious and devout and hoped that Thomas would become a minister. She was close to her eldest son, being a "smoking companion, counselor and confidante" in Carlyle's early days. She suffered a manic episode when Carlyle was a teenager, in which she became "elated, disinhibited, over-talkative and violent." She suffered another breakdown in 1817, which required her to be removed from her home and restrained. Carlyle always spoke highly of his parents, and his character was deeply influenced by both of them.

Carlyle's early education came from his mother, who taught him reading (despite being barely literate), and his father, who taught him arithmetic. He first attended "Tom Donaldson's School" in Ecclefechan followed by Hoddam School (), which "then stood at the Kirk

Kirk is a Scottish and former Northern English word meaning "church". It is often used specifically of the Church of Scotland. Many place names and personal names are also derived from it.

Basic meaning and etymology

As a common noun, ''kirk' ...

", located at the "Cross-roads" midway between Ecclefechan and Hoddam Castle

Hoddom Castle is a large tower house in Dumfries and Galloway, south Scotland. It is located by the River Annan, south-west of Ecclefechan and the same distance north-west of Brydekirk in the parish of Cummertrees. The castle is protected as ...

. By age 7, Carlyle showed enough proficiency in English that he was advised to "go into Latin", which he did with enthusiasm; however, the schoolmaster at Hoddam did not know Latin, so he was handed over to a minister that did, with whom he made a "rapid & sure way". He then went to Annan Academy (), where he studied rudimentary Greek, read Latin and French fluently, and learned arithmetic "thoroughly well". Carlyle was severely bullied by his fellow students at Annan, until he "revolted against them, and gave stroke for stroke"; he remembered the first two years there as among the most miserable of his life.

Edinburgh, the ministry and teaching (1809–1818)

In November 1809 at nearly fourteen years of age, Carlyle walked one hundred miles from his home in order to attend the University of Edinburgh (), where he studied mathematics with John Leslie, science with John Playfair and moral philosophy with Thomas Brown. He gravitated to mathematics and geometry and displayed great talent in those subjects, being credited with the invention of the Carlyle circle. In the University library, he read many important works of eighteenth-century and contemporary history, philosophy, and '' belles-lettres''. He began expressing religious scepticism around this time, asking his mother to her horror, "Did God Almighty come down and make wheelbarrows in a shop?" In 1813 he completed his arts curriculum and enrolled in a theology course at Divinity Hall the following academic year. This was to be the preliminary of a ministerial career.

Carlyle began teaching at Annan Academy in June 1814. He gave his first trial sermons in December 1814 and December 1815, both of which are lost. By the summer of 1815 he had taken an interest in

In November 1809 at nearly fourteen years of age, Carlyle walked one hundred miles from his home in order to attend the University of Edinburgh (), where he studied mathematics with John Leslie, science with John Playfair and moral philosophy with Thomas Brown. He gravitated to mathematics and geometry and displayed great talent in those subjects, being credited with the invention of the Carlyle circle. In the University library, he read many important works of eighteenth-century and contemporary history, philosophy, and '' belles-lettres''. He began expressing religious scepticism around this time, asking his mother to her horror, "Did God Almighty come down and make wheelbarrows in a shop?" In 1813 he completed his arts curriculum and enrolled in a theology course at Divinity Hall the following academic year. This was to be the preliminary of a ministerial career.

Carlyle began teaching at Annan Academy in June 1814. He gave his first trial sermons in December 1814 and December 1815, both of which are lost. By the summer of 1815 he had taken an interest in astronomy

Astronomy () is a natural science that studies astronomical object, celestial objects and phenomena. It uses mathematics, physics, and chemistry in order to explain their origin and chronology of the Universe, evolution. Objects of interest ...

and would study the astronomical theories of Pierre-Simon Laplace

Pierre-Simon, marquis de Laplace (; ; 23 March 1749 – 5 March 1827) was a French scholar and polymath whose work was important to the development of engineering, mathematics, statistics, physics, astronomy, and philosophy. He summarized ...

for several years. In November 1816, he began teaching at Kirkcaldy, having left Annan. There, he made friends with Edward Irving, whose ex-pupil Margaret Gordon became Carlyle's "first love". In May 1817, Carlyle abstained from enrolment in the theology course, news which his parents received with "magnanimity". In the autumn of that year, he read '' De l'Allemagne'' (1813) by Germaine de Staël, which prompted him to seek a German teacher, with whom he learned the pronunciation. In Irving's library, he read the works of David Hume and Edward Gibbon's ''Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire'' (1776–1789); he would later recall that I read Gibbon, and then first clearly saw thatChristianity Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth Jesus, likely from he, יֵשׁוּעַ, translit=Yēšūaʿ, label=Hebrew/Aramaic ( AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesu ...was not true. Then came the most trying time of my life. I should either have gone mad or made an end of myself had I not fallen in with some very superior minds.

Mineralogy, law and first publications (1818–1821)

In the summer of 1818, following a "Tour" with Irving through "Peebles

Peebles ( gd, Na Pùballan) is a town in the Scottish Borders, Scotland. It was historically a royal burgh and the county town of Peeblesshire. According to the 2011 census, the population was 8,376 and the estimated population in June 2018 wa ...

- Moffat moor country", Carlyle made his first attempt at publishing, forwarding an article "of a descriptive Tourist kind" to "some Magazine Editor in Edinburgh", which was not published and is now lost. In October, Carlyle resigned from his position at Kirkcaldy, and left for Edinburgh in November. Shortly before his departure, he began to suffer from dyspepsia, which remained with him throughout his life. He enrolled in a mineralogy

Mineralogy is a subject of geology specializing in the scientific study of the chemistry, crystal structure, and physical (including optical) properties of minerals and mineralized artifacts. Specific studies within mineralogy include the proce ...

class from November 1818 to April 1819, attending lectures by Robert Jameson, and in January 1819 began to study German, desiring to read the mineralogical works of Abraham Gottlob Werner. In February and March, he translated a piece by Jöns Jacob Berzelius, and by September he was "reading Goethe

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (28 August 1749 – 22 March 1832) was a German poet, playwright, novelist, scientist, statesman, theatre director, and critic. His works include plays, poetry, literature, and aesthetic criticism, as well as t ...

". In November he enrolled in "the class of Scots law

Scots law () is the legal system of Scotland. It is a hybrid or mixed legal system containing civil law and common law elements, that traces its roots to a number of different historical sources. Together with English law and Northern Ireland ...

", studying under David Hume (the advocate). In December 1819 and January 1820, Carlyle made his second attempt at publishing, writing a review-article on Marc-Auguste Pictet

Marc-Auguste Pictet (; 23 July 1752 – 19 April 1825) was a Swiss scientific journalist and experimental natural philosopher.

Pictet's main contribution to learning was his editing of the scientific section of the ''Bibliothèque Britann ...

's review of Jean-Alfred Gautier's ''Essai historique sur le problème des trois corps'' (1817) which went unpublished and is lost. The law classes ended in March 1820 and he did not pursue the subject any further.

In the same month, he wrote several articles for David Brewster's '' Edinburgh Encyclopædia'' (1808–1830), which appeared in October. These were his first published writings. In May and June, Carlyle wrote a review-article on the work of Christopher Hansteen, translated a book by Friedrich Mohs, and read Goethe's ''Faust''. By the autumn, Carlyle had also learned Italian and was reading Vittorio Alfieri, Dante Alighieri and Sismondi, though German literature was still his foremost interest, having "revealed" to him a "new Heaven and new Earth". In March 1821, he finished two more articles for Brewster's encyclopedia, and in April he completed a review of Joanna Baillie's ''Metrical Legends'' (1821).

In May, Carlyle was introduced to Jane Baillie Welsh by Irving in Haddington. The two began a correspondence, and Carlyle sent books to her, encouraging her intellectual pursuits; she called him "my German Master".

"Conversion": Leith Walk and Hoddam Hill (1821–1826)

During this time, Carlyle struggled with what he described as "the dismallest Lernean Hydra of problems, spiritual, temporal, eternal". Spiritual doubt, lack of success in his endeavours, and dyspepsia were all damaging his physical and mental health, for which he found relief only in "sea-bathing". In early July 1821, an "incident" occurred to Carlyle inLeith Walk

Leith Walk is one of the longest streets in Edinburgh

Edinburgh ( ; gd, Dùn Èideann ) is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 Council areas of Scotland, council areas. Historically part of the county of Midlothian (interchange ...

, "during those 3 weeks of total sleeplessness, in which almost" his "one solace was that of a daily bathe on the sands between nowiki/>Leith">Leith.html" ;"title="nowiki/>Leith">nowiki/>Leithand Portobello, Edinburgh">Portobello." The incident was the beginning of Carlyle's "Conversion", the process by which he "'authentically took the Devil by the nose'" and flung "''him'' behind me". It gave Carlyle courage in his battle against the "Hydra"; to his brother John, he wrote, "What is there to fear, indeed?"

Carlyle wrote several articles in July, August and September, and in November began a translation of Adrien-Marie Legendre">Adrien Marie Legendre

Adrien-Marie Legendre (; ; 18 September 1752 – 9 January 1833) was a French mathematician who made numerous contributions to mathematics. Well-known and important concepts such as the Legendre polynomials and Legendre transformation are named ...

Carlyle wrote several articles in July, August and September, and in November began a translation of Adrien-Marie Legendre">Adrien Marie Legendre

Adrien-Marie Legendre (; ; 18 September 1752 – 9 January 1833) was a French mathematician who made numerous contributions to mathematics. Well-known and important concepts such as the Legendre polynomials and Legendre transformation are named ...Kitty Kirkpatrick

Katherine Aurora "Kitty" Kirkpatrick (9 April 1802 – 2 March 1889) was a British woman of Anglo-Indian descent best known as a muse of the Scottish philosopher Thomas Carlyle. Born in India to a British father and an Indian mother, Kirk ...

, where he attended Georges Cuvier

Jean Léopold Nicolas Frédéric, Baron Cuvier (; 23 August 1769 – 13 May 1832), known as Georges Cuvier, was a French naturalist and zoologist, sometimes referred to as the "founding father of paleontology". Cuvier was a major figure in na ...

's introductory lecture on comparative anatomy, gathered information on the study of medicine

Medicine is the science and Praxis (process), practice of caring for a patient, managing the diagnosis, prognosis, Preventive medicine, prevention, therapy, treatment, Palliative care, palliation of their injury or disease, and Health promotion ...

, introduced himself to Legendre, was introduced by Legendre to Charles Dupin, observed Laplace and several other notables while declining offers of introduction by Dupin, and heard François Magendie

__NOTOC__

François Magendie (6 October 1783 – 7 October 1855) was a French physiologist, considered a pioneer of experimental physiology. He is known for describing the foramen of Magendie. There is also a ''Magendie sign'', a downward a ...

read a paper on the " fifth pair of nerves".

In May 1825, Carlyle moved into a cottage farmhouse in Hoddam Hill near Ecclefechan, which his father had leased for him. Carlyle lived with his brother Alexander, who, "with a cheap little man-servant", worked the farm, his mother, with one maid-servant, and his two youngest sisters, Jean and Jenny. He had constant contact with the rest of his family, most of whom lived close by at Mainhill, a farm owned by his father. Jane made a successful visit in September 1825. Whilst there, Carlyle wrote ''German Romance'' (1827), a collection of previously untranslated German novellas by Johann Karl August Musäus

Johann Karl August Musäus (29 March 1735 – 28 October 1787) was a popular German author and one of the first collectors of German folk stories, most celebrated for his '' Volksmärchen der Deutschen'' (1782–1787), a collection of German fair ...

, Friedrich de la Motte Fouqué, Ludwig Tieck

Johann Ludwig Tieck (; ; 31 May 177328 April 1853) was a German poet, fiction writer, translator, and critic. He was one of the founding fathers of the Romantic movement in the late 18th and early 19th centuries.

Early life

Tieck was born in B ...

, E. T. A. Hoffmann

Ernst Theodor Amadeus Hoffmann (born Ernst Theodor Wilhelm Hoffmann; 24 January 1776 – 25 June 1822) was a German Romantic author of fantasy and Gothic horror, a jurist, composer, music critic and artist. Penrith Goff, "E.T.A. Hoffmann" in E ...

, and Jean Paul. In Hoddam Hill, Carlyle found respite from the "intolerable fret, noise and confusion" that he had experienced in Edinburgh, and observed what he described as "the finest and vastest prospect all round it I ever saw from any house", with "all Cumberland as in amphitheatre unmatchable". Here, he completed his "Conversion" which began with the Leith Walk incident. He achieved "a grand and ''ever''-joyful victory", in the "final chaining down, and trampling home, 'for good,' home into their caves forever, of all" his "''Spiritual Dragons''". By May 1826, problems with the landlord and the agreement forced the family's relocation to Scotsbrig

Scotsbrig is a farm near Ecclefechan, Dumfries and Galloway, Scotland, and a Category B listed building. Thomas Carlyle lived there with his family in the summer of 1826 before moving to 21 Comely Bank, Edinburgh. Scotsbrig remained a residence ...

, a farm near Ecclefechan. Later in life, he remembered the year at Hoddam Hill as "perhaps the most triumphantly important of my life."

Marriage, Comely Bank and Craigenputtock (1826–1834)

In October 1826, Thomas and Jane Carlyle were married at the Welsh family farm in Templand. Shortly after their marriage, the Carlyles moved into a modest home on Comely Bank in Edinburgh, that had been leased for them by Jane's mother. They lived there from October 1826 to May 1828. In that time, Carlyle published ''German Romance'', began ''Wotton Reinfred'', an autobiographical novel which he left unfinished, and published his first article for the '' Edinburgh Review'', "

In October 1826, Thomas and Jane Carlyle were married at the Welsh family farm in Templand. Shortly after their marriage, the Carlyles moved into a modest home on Comely Bank in Edinburgh, that had been leased for them by Jane's mother. They lived there from October 1826 to May 1828. In that time, Carlyle published ''German Romance'', began ''Wotton Reinfred'', an autobiographical novel which he left unfinished, and published his first article for the '' Edinburgh Review'', "Jean Paul Friedrich Richter

Jean Paul (; born Johann Paul Friedrich Richter, 21 March 1763 – 14 November 1825) was a German Romantic writer, best known for his humorous novels and stories.

Life and work

Jean Paul was born at Wunsiedel, in the Fichtelgebirge mounta ...

" (1827). "Richter" was the first of many essays extolling the virtues of German authors, who were then little-known to English readers; "State of German Literature" was published in October. In Edinburgh, Carlyle made contact with several distinguished literary figures, including '' Edinburgh Review'' editor Francis Jeffrey, John Wilson John Wilson may refer to:

Academics

* John Wilson (mathematician) (1741–1793), English mathematician and judge

* John Wilson (historian) (1799–1870), author of ''Our Israelitish Origin'' (1840), a founding text of British Israelism

* John Wil ...

of '' Blackwood's Magazine'', essayist Thomas De Quincey, and philosopher William Hamilton. In 1827 Carlyle attempted to land the Chair of Moral Philosophy at St. Andrews

St Andrews ( la, S. Andrea(s); sco, Saunt Aundraes; gd, Cill Rìmhinn) is a town on the east coast of Fife in Scotland, southeast of Dundee and northeast of Edinburgh. St Andrews had a recorded population of 16,800 , making it Fife's fourt ...

without success, despite support from an array of prominent intellectuals, including Goethe. He also made an unsuccessful attempt for a professorship at the University of London

The University of London (UoL; abbreviated as Lond or more rarely Londin in post-nominals) is a federal public research university located in London, England, United Kingdom. The university was established by royal charter in 1836 as a degre ...

.

In May 1828, the Carlyles moved to Craigenputtock, the main house of Jane's modest agricultural estate in Dumfriesshire, which they occupied until May 1834. He wrote a number of essays there which earned him money and augmented his reputation, including "Life and Writings of

In May 1828, the Carlyles moved to Craigenputtock, the main house of Jane's modest agricultural estate in Dumfriesshire, which they occupied until May 1834. He wrote a number of essays there which earned him money and augmented his reputation, including "Life and Writings of Werner Werner may refer to:

People

* Werner (name), origin of the name and people with this name as surname and given name

Fictional characters

* Werner (comics), a German comic book character

* Werner Von Croy, a fictional character in the ''Tomb Rai ...

", "Goethe's Helena", "Goethe", " Burns", "The Life of Heyne Heyne is a German surname. Notable people with the surname include:

*Benjamin Heyne (1770–1819), botanist, naturalist, and surgeon

*Christian Gottlob Heyne (1729–1812), German classical scholar and archaeologist

* Dirk Heyne (born 1957), German ...

" (each 1828), "German Playwrights", " Voltaire", " Novalis" (each 1829), "Jean Paul Friedrich Richter Again" (1830), "Cruthers and Jonson; or The Outskirts of Life: A True Story", " Luther's Psalm", and "Schiller" (each 1831). He began but did not complete a history of German literature, from which he drew material for essays " The Nibelungen Lied", "Early German Literature" and parts of "Historic Survey of German Poetry" (each 1831). He published early thoughts on the philosophy of history in "Thoughts on History" (1830) and wrote his first pieces of social criticism, "Signs of the Times" (1829) and "Characteristics" (1831).D. Daiches (ed.), ''Companion to Literature 1'' (London, 1965), p. 89. "Signs" garnered the interest of Gustave d'Eichthal, a member of the Saint-Simonians

Claude Henri de Rouvroy, comte de Saint-Simon (17 October 1760 – 19 May 1825), often referred to as Henri de Saint-Simon (), was a French political, economic and socialist theorist and businessman whose thought had a substantial influence on p ...

, who sent Carlyle Saint-Simonian literature, including Henri de Saint-Simon's ''Nouveau Christianisme'' (1825), which Carlyle translated and wrote an introduction for.

Most notably, he wrote ''

Most notably, he wrote ''Sartor Resartus

''Sartor Resartus: The Life and Opinions of Herr Teufelsdröckh in Three Books'' is an 1831 novel by the Scottish essayist, historian and philosopher Thomas Carlyle, first published as a serial in '' Fraser's Magazine'' in November 1833 – Augu ...

''. Finishing the manuscript in late July 1831, Carlyle began his search for a publisher, leaving for London in early August. He and his wife lived there for the winter at 4 (now 33) Ampton Street, Kings Cross, in a house built by Thomas Cubitt. The death of Carlyle's father in January 1832 and his inability to attend the funeral moved him to write the first of what would become the ''Reminiscences'', published posthumously in 1881. Carlyle had not found a publisher by the time he returned to Craigenputtock in March but he had initiated important friendships with Leigh Hunt and John Stuart Mill. That year, Carlyle wrote the essays "Goethe's Portrait", "Death of Goethe", "Goethe's Works", "Biography", " Boswell's Life of Johnson", and " Corn-Law Rhymes". Three months after their return from a January to May 1833 stay in Edinburgh, the Carlyles were visited at Craigenputtock by Ralph Waldo Emerson. Emerson (and other like-minded Americans) had been deeply affected by Carlyle's essays and determined to meet him during the northern terminus of a literary pilgrimage; it was to be the start of a lifelong friendship and a famous correspondence. 1833 saw publication of the essays " Diderot" and "Count Cagliostro

Count Alessandro di Cagliostro (, ; 2 June 1743 – 26 August 1795) was the alias of the Italian occultist Giuseppe Balsamo (; in French usually referred to as Joseph Balsamo).

Cagliostro was an Italian adventurer and self-styled magician. ...

"; in the latter, Carlyle introduced the idea of " Captains of Industry".

Chelsea (1834–1845)

In June 1834, the Carlyles moved into5 Cheyne Row

Carlyle's House, in Cheyne Row, Chelsea, central London, was the home of the Scottish essayist, historian and philosopher Thomas Carlyle and his wife Jane from 1834 until his death. The home of these writers was purchased by public subscripti ...

, Chelsea, which became their home for the remainder of their respective lives. Residence in London wrought a large expansion of Carlyle's social circle. He became acquainted with scores of leading writers, novelists, artists, radicals, men of science, Church of England clergymen, and political figures. Two of his most important friendships were with Lord and Lady Ashburton; though Carlyle's warm affection for the latter would eventually strain his marriage, the Ashburtons helped to broaden his social horizons, giving him access to circles of intelligence, political influence, and power. Carlyle eventually decided to publish ''Sartor'' serially in '' Fraser's Magazine'', with the instalments appearing between November 1833 and August 1834. Despite early recognition from Emerson, Mill and others, it was generally received poorly, if noticed at all. In 1834, Carlyle applied unsuccessfully for the astronomy professorship at the Edinburgh observatory. That autumn, he arranged for the publication of a history of the

Carlyle eventually decided to publish ''Sartor'' serially in '' Fraser's Magazine'', with the instalments appearing between November 1833 and August 1834. Despite early recognition from Emerson, Mill and others, it was generally received poorly, if noticed at all. In 1834, Carlyle applied unsuccessfully for the astronomy professorship at the Edinburgh observatory. That autumn, he arranged for the publication of a history of the French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are conside ...

and set about researching and writing it shortly thereafter. Having completed the first volume after five months of writing, he lent the manuscript to Mill, who had been supplying him with materials for his research. One evening in March 1835, Mill arrived at Carlyle's door appearing "unresponsive, pale, the very picture of despair". He had come to tell Carlyle that the manuscript was destroyed. It had been "left out", and Mill's housemaid took it for wastepaper, leaving only "some four tattered leaves". Carlyle was sympathetic: "I can be angry with no one; for they that were concerned in it have a far deeper sorrow than mine: it is purely the hand of Providence". The next day, Mill offered Carlyle £200, of which he would only accept £100. He began the volume anew shortly afterwards. Despite an initial struggle, he was not deterred, feeling like "a runner that tho' ''tripped'' down, will not lie there, but rise and run again." By September, the volume was rewritten. That year, he wrote a eulogy for his friend, "Death of Edward Irving".

In April 1836, with the intercession of Emerson, ''Sartor Resartus'' was first published in book form in Boston, soon selling out its initial run of five hundred copies. Carlyle's three-volume history of the French Revolution was completed in January 1837 and sent to the press. Contemporaneously, the essay "Memoirs of Mirabeau" was published, as was " The Diamond Necklace" in January and February, and "Parliamentary History of the French Revolution" in April. In need of further financial security, Carlyle began a series of lectures on German literature in May, delivered extemporaneously in Willis' Rooms. '' The Spectator'' reported that the first lecture was given "to a very crowded and yet a select audience of both sexes." Carlyle recalled being "wasted and fretted to a thread, my tongue … dry as charcoal: the people were there, I was obliged to stumble in, and start. ''Ach Gott!''" Despite his inexperience as a lecturer and deficiency "in the mere mechanism of oratory," reviews were positive and the series proved profitable for him.

During Carlyle's lecture series, '' The French Revolution: A History'' was officially published. It marked his career breakthrough. At the end of the year, Carlyle reported to Karl August Varnhagen von Ense that his earlier efforts to popularise German literature were beginning to produce results, and expressed his satisfaction: "''Deutschland'' will reclaim her great Colony; we shall become more ''Deutsch'', that is to say more ''English'', at same time." ''The French Revolution'' fostered the republication of ''Sartor Resartus'' in London in 1838 as well as a collection of his earlier writings in the form of the '' Critical and Miscellaneous Essays'', facilitated in Boston with the aid of Emerson. Carlyle presented his second lecture series in April and June 1838 on the history of literature at the Marylebone Institution in Portman Square. '' The Examiner'' reported that at the end of the second lecture, "Mr. Carlyle was heartily greeted with applause." Carlyle felt that they "went on better and better, and grew at last, or threatened to grow, quite a flaming affair." He published two essays in 1838, "Sir Walter Scott", being a review of John Gibson Lockhart's biography, and "Varnhagen von Ense's Memoirs". In April 1839, Carlyle published "Petition on the Copyright Bill". A third series of lectures was given in May on the revolutions of modern Europe, which the ''Examiner'' reviewed positively, noting after the third lecture that "Mr. Carlyle's audiences appear to increase in number every time." Carlyle wrote to his mother that the lectures were met "with very kind acceptance from people more distinguished than ever; yet still with a feeling that I was far from the ''right'' lecturing point yet." In July, he published "On the Sinking of the Vengeur" and in December he published ''Chartism'', a pamphlet in which he addressed the movement of the same name and raised the Condition-of-England question.

During Carlyle's lecture series, '' The French Revolution: A History'' was officially published. It marked his career breakthrough. At the end of the year, Carlyle reported to Karl August Varnhagen von Ense that his earlier efforts to popularise German literature were beginning to produce results, and expressed his satisfaction: "''Deutschland'' will reclaim her great Colony; we shall become more ''Deutsch'', that is to say more ''English'', at same time." ''The French Revolution'' fostered the republication of ''Sartor Resartus'' in London in 1838 as well as a collection of his earlier writings in the form of the '' Critical and Miscellaneous Essays'', facilitated in Boston with the aid of Emerson. Carlyle presented his second lecture series in April and June 1838 on the history of literature at the Marylebone Institution in Portman Square. '' The Examiner'' reported that at the end of the second lecture, "Mr. Carlyle was heartily greeted with applause." Carlyle felt that they "went on better and better, and grew at last, or threatened to grow, quite a flaming affair." He published two essays in 1838, "Sir Walter Scott", being a review of John Gibson Lockhart's biography, and "Varnhagen von Ense's Memoirs". In April 1839, Carlyle published "Petition on the Copyright Bill". A third series of lectures was given in May on the revolutions of modern Europe, which the ''Examiner'' reviewed positively, noting after the third lecture that "Mr. Carlyle's audiences appear to increase in number every time." Carlyle wrote to his mother that the lectures were met "with very kind acceptance from people more distinguished than ever; yet still with a feeling that I was far from the ''right'' lecturing point yet." In July, he published "On the Sinking of the Vengeur" and in December he published ''Chartism'', a pamphlet in which he addressed the movement of the same name and raised the Condition-of-England question.

In May 1840, Carlyle gave his fourth and final set of lectures, which were published in 1841 as '' On Heroes, Hero-Worship, & the Heroic in History.'' Carlyle wrote to his brother John afterwards, "The Lecturing business went of 'sic''with sufficient ''éclat;'' the Course was generally judged, and I rather join therein myself, to be the bad ''best'' I have yet given." In the 1840 edition of the ''Essays'', Carlyle published "Fractions", a collection of poems written from 1823 to 1833. Later that year, he declined a proposal for a professorship of history at Edinburgh. Carlyle was the principal founder of the London Library in 1841. He had become frustrated by the facilities available at the British Museum Library, where he was often unable to find a seat (obliging him to perch on ladders), where he complained that the enforced close confinement with his fellow readers gave him a "museum headache", where the books were unavailable for loan, and where he found the library's collections of pamphlets and other material relating to the French Revolution and English Civil Wars inadequately catalogued. In particular, he developed an antipathy to the Keeper of Printed Books, Anthony Panizzi (despite the fact that Panizzi had allowed him many privileges not granted to other readers), and criticised him in a footnote to an article published in the ''

In May 1840, Carlyle gave his fourth and final set of lectures, which were published in 1841 as '' On Heroes, Hero-Worship, & the Heroic in History.'' Carlyle wrote to his brother John afterwards, "The Lecturing business went of 'sic''with sufficient ''éclat;'' the Course was generally judged, and I rather join therein myself, to be the bad ''best'' I have yet given." In the 1840 edition of the ''Essays'', Carlyle published "Fractions", a collection of poems written from 1823 to 1833. Later that year, he declined a proposal for a professorship of history at Edinburgh. Carlyle was the principal founder of the London Library in 1841. He had become frustrated by the facilities available at the British Museum Library, where he was often unable to find a seat (obliging him to perch on ladders), where he complained that the enforced close confinement with his fellow readers gave him a "museum headache", where the books were unavailable for loan, and where he found the library's collections of pamphlets and other material relating to the French Revolution and English Civil Wars inadequately catalogued. In particular, he developed an antipathy to the Keeper of Printed Books, Anthony Panizzi (despite the fact that Panizzi had allowed him many privileges not granted to other readers), and criticised him in a footnote to an article published in the ''Westminster Review

The ''Westminster Review'' was a quarterly British publication. Established in 1823 as the official organ of the Philosophical Radicals, it was published from 1824 to 1914. James Mill was one of the driving forces behind the liberal journal u ...

'' as the "respectable Sub-Librarian". Carlyle's eventual solution, with the support of a number of influential friends, was to call for the establishment of a private subscription library from which books could be borrowed.

Carlyle had chosen Oliver Cromwell as the subject for a book in 1840 and struggled to find what form it would take. In the interim, he wrote '' Past and Present'' (1843) and the articles " Baillie the Covenanter" (1841), "Dr. Francia

Doctor is an academic title that originates from the Latin word of the same spelling and meaning. The word is originally an agentive noun of the Latin verb 'to teach'. It has been used as an academic title in Europe since the 13th century, w ...

" (1843), and "An Election to the Long Parliament" (1844). Carlyle declined an offer for professorship from St. Andrews in 1844. The first edition of '' Oliver Cromwell's Letters and Speeches: with Elucidations'' was published in 1845; it was a popular success, and did much to revise Cromwell's standing in Britain. Financially secure, Carlyle wrote little in the years that immediately followed ''Cromwell''.

Journeys to Ireland and Germany (1846–1865)

Carlyle visited Ireland in 1846 with Charles Gavan Duffy for a companion and guide, and wrote a series of brief articles on the Irish question in 1848. These were "Ireland and the British Chief Governor", "Irish Regiments (of the New Æra)", and "The Repeal of the Union", each of which offered solutions to Ireland's problems and argued to preserve England's connection with Ireland. Carlyle wrote an article titled "Ireland and Sir Robert Peel" (signed "C.") published in April 1849 in '' The Spectator'' in response to two speeches given by Peel wherein he made many of the same proposals which Carlyle had earlier suggested; he called the speeches "like a prophecy of better things, inexpressibly cheering." In May, he published "Indian Meal", in which he advanced maize as a remedy to the Great Famine as well as the worries of "disconsolate Malthusians". He visited Ireland again with Duffy later that year while recording his impressions in his letters and a series of memoranda, published as ''Reminiscences of My Irish Journey in 1849'' after his death; Duffy would publish his own memoir of their travels, ''Conversations with Carlyle''.

Carlyle's travels in Ireland deeply affected his views on society, as did the Revolutions of 1848. While embracing the latter as necessary in order to cleanse society of various forms of anarchy and misgovernment, he denounced their democratic undercurrent and insisted on the need for authoritarian leaders. These events inspired his next two works, " Occasional Discourse on the Negro Question" (1849), in which he coined the term " Dismal Science" to describe political economy, and '' Latter-Day Pamphlets'' (1850). The illiberal content of these works sullied Carlyle's reputation for some progressives, while endearing him to those that shared his views. In 1851, Carlyle wrote '' The Life of John Sterling'' as a corrective to Julius Hare's unsatisfactory 1848 biography. In late September and early October, he made his second trip to Paris, where he met

Carlyle visited Ireland in 1846 with Charles Gavan Duffy for a companion and guide, and wrote a series of brief articles on the Irish question in 1848. These were "Ireland and the British Chief Governor", "Irish Regiments (of the New Æra)", and "The Repeal of the Union", each of which offered solutions to Ireland's problems and argued to preserve England's connection with Ireland. Carlyle wrote an article titled "Ireland and Sir Robert Peel" (signed "C.") published in April 1849 in '' The Spectator'' in response to two speeches given by Peel wherein he made many of the same proposals which Carlyle had earlier suggested; he called the speeches "like a prophecy of better things, inexpressibly cheering." In May, he published "Indian Meal", in which he advanced maize as a remedy to the Great Famine as well as the worries of "disconsolate Malthusians". He visited Ireland again with Duffy later that year while recording his impressions in his letters and a series of memoranda, published as ''Reminiscences of My Irish Journey in 1849'' after his death; Duffy would publish his own memoir of their travels, ''Conversations with Carlyle''.

Carlyle's travels in Ireland deeply affected his views on society, as did the Revolutions of 1848. While embracing the latter as necessary in order to cleanse society of various forms of anarchy and misgovernment, he denounced their democratic undercurrent and insisted on the need for authoritarian leaders. These events inspired his next two works, " Occasional Discourse on the Negro Question" (1849), in which he coined the term " Dismal Science" to describe political economy, and '' Latter-Day Pamphlets'' (1850). The illiberal content of these works sullied Carlyle's reputation for some progressives, while endearing him to those that shared his views. In 1851, Carlyle wrote '' The Life of John Sterling'' as a corrective to Julius Hare's unsatisfactory 1848 biography. In late September and early October, he made his second trip to Paris, where he met Adolphe Thiers

Marie Joseph Louis Adolphe Thiers ( , ; 15 April 17973 September 1877) was a French statesman and historian. He was the second elected President of France and first President of the French Third Republic.

Thiers was a key figure in the July Rev ...

and Prosper Mérimée; his account, "Excursion (Futile Enough) to Paris; Autumn 1851", was published posthumously.

In 1852, Carlyle began research on Frederick the Great, whom he had expressed interest in writing a biography of as early as 1830. He travelled to Germany that year, examining source documents and prior histories. Carlyle struggled through research and writing, telling von Ense it was "the poorest, most troublesome and arduous piece of work he has ever undertaken". In 1856, the first two volumes of '' History of Friedrich II. of Prussia, Called Frederick the Great'' were sent to the press and published in 1858. During this time, he wrote "The Opera" (1852), "Project of a National Exhibition of Scottish Portraits" (1854) at the request of David Laing, and "The Prinzenraub" (1855). In October 1855, he finished ''The Guises'', a history of the House of Guise

The House of Guise (pronunciation: �ɥiz Dutch: ''Wieze, German: Wiese'') was a prominent French noble family, that was involved heavily in the French Wars of Religion. The House of Guise was the founding house of the Principality of Joinv ...

and its relation to Scottish history, which was first published in 1981. Carlyle made a second expedition to Germany in 1858 to survey the topography of battlefields, which he documented in ''Journey to Germany, Autumn 1858'', published posthumously. In May 1863, Carlyle wrote the short dialogue "Ilias (Americana) in Nuce" (American Iliad

The ''Iliad'' (; grc, Ἰλιάς, Iliás, ; "a poem about Ilium") is one of two major ancient Greek epic poems attributed to Homer. It is one of the oldest extant works of literature still widely read by modern audiences. As with the '' Odys ...

in a Nutshell) on the topic of the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by state ...

. Upon publication in August, the "Ilias" drew scornful letters from David Atwood Wasson and Horace Howard Furness. In the summer of 1864, Carlyle lived at 117 Marina (built by James Burton) in St Leonards-on-Sea, in order to be nearer to his ailing wife who was in possession of caretakers there.

Carlyle planned to write four volumes but had written six by the time ''Frederick'' was finished in 1865. Before its end, Carlyle had developed a tremor in his writing hand. Upon its completion, it was received as a masterpiece. He earned a sobriquet, the " Sage of Chelsea", and in the eyes of those that had rebuked his politics, it restored Carlyle to his position as a great man of letters. Carlyle was elected Lord Rector of Edinburgh University in November 1865, succeeding William Ewart Gladstone

William Ewart Gladstone ( ; 29 December 1809 – 19 May 1898) was a British statesman and Liberal politician. In a career lasting over 60 years, he served for 12 years as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, spread over four non-con ...

and defeating Benjamin Disraeli by a vote of 657 to 310.

Final years (1866–1881)

Carlyle travelled to Scotland to deliver his "Inaugural Address at Edinburgh" as Rector in April 1866. During his trip, he was accompanied by John Tyndall,

Carlyle travelled to Scotland to deliver his "Inaugural Address at Edinburgh" as Rector in April 1866. During his trip, he was accompanied by John Tyndall, Thomas Henry Huxley

Thomas Henry Huxley (4 May 1825 – 29 June 1895) was an English biologist and anthropologist specialising in comparative anatomy. He has become known as "Darwin's Bulldog" for his advocacy of Charles Darwin's theory of evolution.

The stor ...

and Thomas Erskine. One of those that welcomed Carlyle on his arrival was Sir David Brewster, president of the university and the commissioner of Carlyle's first professional writings for the ''Edinburgh Encyclopædia''. Carlyle was joined onstage by his fellow travelers, Brewster, Moncure D. Conway

Moncure Daniel Conway (March 17, 1832 – November 15, 1907) was an American abolitionist minister and radical writer. At various times Methodist, Unitarian, and a Freethinker, he descended from patriotic and patrician families of Virginia ...

, George Harvey, Lord Neaves and others. Carlyle spoke extemporaneously on several subjects, concluding his address with a quote from Goethe: "Work, and despair not: ''Wir heissen euch hoffen,'' 'We bid you be of hope!'" Tyndall reported to Jane in a three-word telegram that it was "A perfect triumph." The warm reception he received in his homeland of Scotland marked the climax of Carlyle's life as a writer. While still in Scotland, Carlyle received abrupt news of Jane's sudden death in London. Upon her death, Carlyle began to edit his wife's letters and write reminiscences of her. He experienced feelings of guilt as he read her complaints about her illnesses, his friendship with Lady Harriet Ashburton, and his devotion to his labour, particularly on ''Frederick the Great''. Although deep in grief, Carlyle remained active in public life.

Amidst controversy over governor John Eyre's violent repression of the Morant Bay rebellion, Carlyle assumed leadership of the Eyre Defence and Aid Fund in 1865 and 1866. The Defence had convened in response to the anti-Eyre

Amidst controversy over governor John Eyre's violent repression of the Morant Bay rebellion, Carlyle assumed leadership of the Eyre Defence and Aid Fund in 1865 and 1866. The Defence had convened in response to the anti-Eyre Jamaica Committee

The Jamaica Committee was a group set up in Great Britain in 1865, which called for Edward Eyre, Governor of Jamaica, to be tried for his excesses in suppressing the Morant Bay rebellion of 1865. More radical members of the Committee wanted h ...

, led by Mill and backed by Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English natural history#Before 1900, naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all speci ...

, Herbert Spencer and others. Carlyle and the Defence were supported by John Ruskin, Alfred, Lord Tennyson, Charles Dickens