Thirty Years’ War on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Thirty Years' War, fought primarily in

Disputes occasionally resulted in full-scale conflict like the 1583 to 1588 Cologne War, caused when its

Disputes occasionally resulted in full-scale conflict like the 1583 to 1588 Cologne War, caused when its

Ferdinand once claimed he would rather see his lands destroyed than tolerate

Ferdinand once claimed he would rather see his lands destroyed than tolerate  On 19 August, the Bohemian Estates rescinded Ferdinand's 1617 election as king and a week later formally offered the crown to Frederick. On 28 August, Ferdinand was elected Holy Roman Emperor, making war inevitable if Frederick accepted the Bohemian crown. Most of Frederick's advisors urged him to reject it, as did the Duke of Savoy, and his father-in-law James I. The exceptions included Christian of Anhalt and Maurice of Orange, for whom conflict in Germany was a means to divert Spanish resources from the Netherlands. The Dutch offered subsidies to Frederick and the Protestant Union, helped raise loans for Bohemia, and provided weapons and munitions. However, wider European support failed to materialise, largely due to lack of enthusiasm for removing a legally elected ruler, regardless of religion.

Although Frederick accepted the crown and entered Prague in October 1619, his support eroded over the next few months. In July 1620, the Protestant Union proclaimed its neutrality, while John George of Saxony backed Ferdinand in return for the cession of

On 19 August, the Bohemian Estates rescinded Ferdinand's 1617 election as king and a week later formally offered the crown to Frederick. On 28 August, Ferdinand was elected Holy Roman Emperor, making war inevitable if Frederick accepted the Bohemian crown. Most of Frederick's advisors urged him to reject it, as did the Duke of Savoy, and his father-in-law James I. The exceptions included Christian of Anhalt and Maurice of Orange, for whom conflict in Germany was a means to divert Spanish resources from the Netherlands. The Dutch offered subsidies to Frederick and the Protestant Union, helped raise loans for Bohemia, and provided weapons and munitions. However, wider European support failed to materialise, largely due to lack of enthusiasm for removing a legally elected ruler, regardless of religion.

Although Frederick accepted the crown and entered Prague in October 1619, his support eroded over the next few months. In July 1620, the Protestant Union proclaimed its neutrality, while John George of Saxony backed Ferdinand in return for the cession of

Dutch and English subsidies enabled Christian to devise an ambitious three part campaign plan. While he led the main force down the Weser, Mansfeld would attack Wallenstein in

Dutch and English subsidies enabled Christian to devise an ambitious three part campaign plan. While he led the main force down the Weser, Mansfeld would attack Wallenstein in  With Ferdinand's resources stretched by the outbreak of the

With Ferdinand's resources stretched by the outbreak of the

From 1626 to 1629, Gustavus was engaged in a war with Poland–Lithuania, ruled by his Catholic cousin

From 1626 to 1629, Gustavus was engaged in a war with Poland–Lithuania, ruled by his Catholic cousin  Gustavus put pressure on Brandenburg by sacking Küstrin and

Gustavus put pressure on Brandenburg by sacking Küstrin and  Two months later, the Swedes fought an imperial army at Lützen. Both sides suffered heavy casualties, while Gustavus himself was killed and some Swedish units incurred losses of over 60%. Fighting continued until dusk when Wallenstein retreated, abandoning his artillery and wounded. Despite their losses, this allowed the Swedes to claim victory, although the result continues to be disputed.

After his death, Gustavus' policies were continued by his Chancellor

Two months later, the Swedes fought an imperial army at Lützen. Both sides suffered heavy casualties, while Gustavus himself was killed and some Swedish units incurred losses of over 60%. Fighting continued until dusk when Wallenstein retreated, abandoning his artillery and wounded. Despite their losses, this allowed the Swedes to claim victory, although the result continues to be disputed.

After his death, Gustavus' policies were continued by his Chancellor

However, Condé was unable to fully exploit his victory due to factors affecting all combatants. The devastation inflicted by 25 years of warfare meant armies spent more time foraging than fighting, forcing them to become smaller and more mobile, with a much greater emphasis on cavalry. Difficulties in gathering provisions meant campaigns started later, and restricted them to areas that could be easily supplied, usually close to rivers. In addition, the French army in Germany was shattered at Tuttlingen in November by Bavarian general

However, Condé was unable to fully exploit his victory due to factors affecting all combatants. The devastation inflicted by 25 years of warfare meant armies spent more time foraging than fighting, forcing them to become smaller and more mobile, with a much greater emphasis on cavalry. Difficulties in gathering provisions meant campaigns started later, and restricted them to areas that could be easily supplied, usually close to rivers. In addition, the French army in Germany was shattered at Tuttlingen in November by Bavarian general

The final Peace of Westphalia consisted of three separate agreements. These were the

The final Peace of Westphalia consisted of three separate agreements. These were the

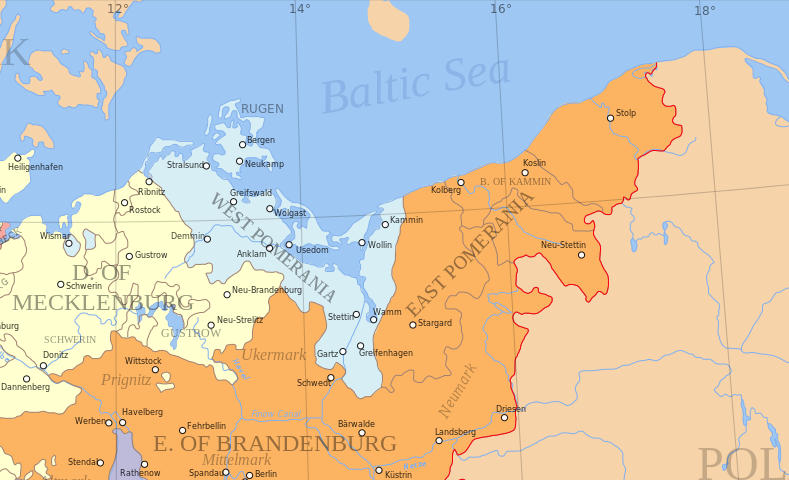

In 1940, agrarian historian Günther Franz published an analysis of data from across Germany covering the period from 1618 to 1648. Broadly confirmed by more recent work, he concluded about 40% of the civilian rural population became casualties, and 33% of the urban. These figures need to be read with care, since Franz calculated the ''absolute decline'' in pre and post-war populations, or 'total demographic loss'. They therefore include factors unrelated to death or disease, such as permanent migration to areas outside the Empire or lower birthrates, a common but less obvious impact of extended warfare. There were also wide regional variations, with areas of northwest Germany experiencing minimal loss of population, while those of Mecklenburg,

In 1940, agrarian historian Günther Franz published an analysis of data from across Germany covering the period from 1618 to 1648. Broadly confirmed by more recent work, he concluded about 40% of the civilian rural population became casualties, and 33% of the urban. These figures need to be read with care, since Franz calculated the ''absolute decline'' in pre and post-war populations, or 'total demographic loss'. They therefore include factors unrelated to death or disease, such as permanent migration to areas outside the Empire or lower birthrates, a common but less obvious impact of extended warfare. There were also wide regional variations, with areas of northwest Germany experiencing minimal loss of population, while those of Mecklenburg,

Contemporaries spoke of a "frenzy of despair" as people sought to make sense of the relentless and often random bloodshed unleashed by the war. Attributed by religious authorities to divine retribution, attempts to identify a supernatural cause led to a series of

Contemporaries spoke of a "frenzy of despair" as people sought to make sense of the relentless and often random bloodshed unleashed by the war. Attributed by religious authorities to divine retribution, attempts to identify a supernatural cause led to a series of

France arguably gained more from the conflict than any other power, and by 1648, most of Richelieu's objectives had been achieved. These included separation of the Spanish and Austrian Habsburgs, expansion of the French frontier into the Empire, and an end to Spanish military supremacy in northern Europe. Although the Franco-Spanish war continued until 1659, Westphalia allowed Louis XIV to begin replacing Spain as the predominant European power.

While religion remained a divisive political issue in many countries, the Thirty Years' War is arguably the last major Continental Europe, European conflict where it was a primary driver. Future religious conflicts were either internal, such as the Camisards revolt in southern France, or relatively minor, like the 1712 Toggenburg War. The war created the outlines of a Europe that persisted until 1815 and beyond, most significantly the nation-state of France, along with the start of a split between Germany and a separate Austro-Hungarian bloc.

France arguably gained more from the conflict than any other power, and by 1648, most of Richelieu's objectives had been achieved. These included separation of the Spanish and Austrian Habsburgs, expansion of the French frontier into the Empire, and an end to Spanish military supremacy in northern Europe. Although the Franco-Spanish war continued until 1659, Westphalia allowed Louis XIV to begin replacing Spain as the predominant European power.

While religion remained a divisive political issue in many countries, the Thirty Years' War is arguably the last major Continental Europe, European conflict where it was a primary driver. Future religious conflicts were either internal, such as the Camisards revolt in southern France, or relatively minor, like the 1712 Toggenburg War. The war created the outlines of a Europe that persisted until 1815 and beyond, most significantly the nation-state of France, along with the start of a split between Germany and a separate Austro-Hungarian bloc.

Central Europe

Central Europe is a geographical region of Europe between Eastern Europe, Eastern, Southern Europe, Southern, Western Europe, Western and Northern Europe, Northern Europe. Central Europe is known for its cultural diversity; however, countries in ...

between 1618 and 1648, was one of the most destructive conflicts in European history

The history of Europe is traditionally divided into four time periods: prehistoric Europe (prior to about 800 BC), classical antiquity (800 BC to AD 500), the Middle Ages (AD 500–1500), and the modern era (since AD 1500).

The first early Eu ...

. An estimated 4.5 to 8 million soldiers and civilians died from battle, famine, or disease, while parts of Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

reported population declines of over 50%. Related conflicts include the Eighty Years' War

The Eighty Years' War or Dutch Revolt (; 1566/1568–1648) was an armed conflict in the Habsburg Netherlands between disparate groups of rebels and the Spanish Empire, Spanish government. The Origins of the Eighty Years' War, causes of the w ...

, the War of the Mantuan Succession

The War of the Mantuan Succession, from 1628 to 1631, was caused by the death in December 1627 of Vincenzo II, last male heir from the House of Gonzaga, long-time rulers of Mantua and Montferrat. Their strategic importance led to a proxy war b ...

, the Franco-Spanish War, the Torstenson War

The Torstenson War was fought between Sweden and Denmark–Norway from 1643 to 1645. The name derives from Swedish general Lennart Torstenson.

Denmark-Norway had withdrawn from the Thirty Years' War in the 1629 Treaty of Lübeck. After its vic ...

, the Dutch-Portuguese War, and the Portuguese Restoration War

The Restoration War (), historically known as the Acclamation War (''Guerra da Aclamação''), was the war between Portugal and Spain that began with the Portuguese revolution of 1640 and ended with the Treaty of Lisbon in 1668, bringing a forma ...

.

The war had its origins in the 16th-century Reformation

The Reformation, also known as the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation, was a time of major Theology, theological movement in Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the p ...

, which led to religious conflict within the Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire, also known as the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation after 1512, was a polity in Central and Western Europe, usually headed by the Holy Roman Emperor. It developed in the Early Middle Ages, and lasted for a millennium ...

. The 1555 Peace of Augsburg

The Peace of Augsburg (), also called the Augsburg Settlement, was a treaty between Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor, and the Schmalkaldic League, signed on 25 September 1555 in the German city of Augsburg. It officially ended the religious struggl ...

attempted to resolve this by dividing the Empire into Catholic

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

and Lutheran

Lutheranism is a major branch of Protestantism that emerged under the work of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German friar and Protestant Reformers, reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practices of the Catholic Church launched ...

states, but the settlement was destabilised by the subsequent expansion of Protestantism

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that emphasizes Justification (theology), justification of sinners Sola fide, through faith alone, the teaching that Salvation in Christianity, salvation comes by unmerited Grace in Christianity, divin ...

beyond these boundaries. Combined with differences over the limits of imperial authority, religion was thus an important factor in starting the war. However, its scope and extent was largely the consequence of external drivers such as the French–Habsburg rivalry

The term French–Habsburg rivalry (; ) describes the rivalry between France and the House of Habsburg. The Habsburgs headed an expansive and evolving empire that included, at various times, the Holy Roman Empire, the Habsburg Spain, Spanish Emp ...

and the Dutch Revolt

The Eighty Years' War or Dutch Revolt (; 1566/1568–1648) was an armed conflict in the Habsburg Netherlands between disparate groups of rebels and the Spanish government. The causes of the war included the Reformation, centralisation, exc ...

.

Its outbreak is generally traced to 1618

Events

January–March

* January 6

** Jahangir, ruler of the Mughal Empire in northern India, gives an audience for the first time to a representative of the British East India Company, receiving Sir Thomas Roe at the capital at ...

, when the Catholic Emperor Ferdinand II

Ferdinand II (9 July 1578 – 15 February 1637) was Holy Roman Emperor, King of Bohemia, King of Hungary, Hungary, and List of Croatian monarchs, Croatia from 1619 until his death in 1637. He was the son of Archduke Charles II, Archduke of Austr ...

was replaced as king of Bohemia

The Duchy of Bohemia was established in 870 and raised to the Kingdom of Bohemia in Golden Bull of Sicily, 1198. Several Bohemian monarchs ruled as non-hereditary kings and first gained the title in 1085. From 1004 to 1806, Bohemia was part of th ...

by the Protestant Frederick V of the Palatinate Frederick may refer to:

People

* Frederick (given name), the name

Given name

Nobility

= Anhalt-Harzgerode =

* Frederick, Prince of Anhalt-Harzgerode (1613–1670)

= Austria =

* Frederick I, Duke of Austria (Babenberg), Duke of Austria fr ...

. Although Ferdinand quickly regained control of Bohemia, Frederick's participation expanded fighting into the Palatinate, whose strategic importance drew in the Dutch Republic

The United Provinces of the Netherlands, commonly referred to in historiography as the Dutch Republic, was a confederation that existed from 1579 until the Batavian Revolution in 1795. It was a predecessor state of the present-day Netherlands ...

and Spain, then engaged in the Eighty Years' War. In addition, the acquisition of territories within the Empire by rulers like Christian IV of Denmark

Christian IV (12 April 1577 – 28 February 1648) was King of Denmark and King of Norway, Norway and List of rulers of Schleswig-Holstein, Duke of Holstein and Schleswig from 1588 until his death in 1648. His reign of 59 years and 330 days is th ...

and Gustavus Adolphus

Gustavus Adolphus (9 December N.S 19 December">Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="/nowiki>Old Style and New Style dates">N.S 19 December15946 November Old Style and New Style dates">N.S 16 November] 1632), also known in English as ...

of Swedish Empire, Sweden gave them and other foreign powers an ongoing motive to intervene. Combined with fears the Protestant religion in general was threatened, these factors turned an internal dynastic dispute into a European conflict.

The period 1618 to 1635 was primarily a civil war

A civil war is a war between organized groups within the same Sovereign state, state (or country). The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies.J ...

within the Holy Roman Empire, which largely ended with the Peace of Prague. However, France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

's entry into the war in alliance

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or sovereign state, states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not an explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an a ...

with Sweden turned the empire into one theatre of a wider struggle with their Habsburg rivals, Emperor Ferdinand III

Ferdinand III (Ferdinand Ernest; 13 July 1608 – 2 April 1657) was Archduke of Austria, King of Hungary and Croatia from 1625, King of Bohemia from 1627 and Holy Roman Emperor from 1637 to his death.

Ferdinand ascended the throne at the begi ...

and Spain. Fighting ended with the 1648 Peace of Westphalia

The Peace of Westphalia (, ) is the collective name for two peace treaties signed in October 1648 in the Westphalian cities of Osnabrück and Münster. They ended the Thirty Years' War (1618–1648) and brought peace to the Holy Roman Empire ...

, whose terms included greater autonomy for states like Bavaria

Bavaria, officially the Free State of Bavaria, is a States of Germany, state in the southeast of Germany. With an area of , it is the list of German states by area, largest German state by land area, comprising approximately 1/5 of the total l ...

and Saxony

Saxony, officially the Free State of Saxony, is a landlocked state of Germany, bordering the states of Brandenburg, Saxony-Anhalt, Thuringia, and Bavaria, as well as the countries of Poland and the Czech Republic. Its capital is Dresden, and ...

, as well as acceptance of Dutch independence by Spain. The conflict shifted the balance of power in favour of France, and set the stage for the expansionist wars of Louis XIV

LouisXIV (Louis-Dieudonné; 5 September 16381 September 1715), also known as Louis the Great () or the Sun King (), was King of France from 1643 until his death in 1715. His verified reign of 72 years and 110 days is the List of longest-reign ...

which dominated Europe for the next sixty years.

Structural origins

The 16th centuryReformation

The Reformation, also known as the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation, was a time of major Theology, theological movement in Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the p ...

caused open warfare between Protestants

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that emphasizes Justification (theology), justification of sinners Sola fide, through faith alone, the teaching that Salvation in Christianity, salvation comes by unmerited Grace in Christianity, divin ...

and Catholics

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics worldwide as of 2025. It is among the world's oldest and largest international institut ...

within the Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire, also known as the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation after 1512, was a polity in Central and Western Europe, usually headed by the Holy Roman Emperor. It developed in the Early Middle Ages, and lasted for a millennium ...

, which ended with the 1552 Peace of Passau

The Peace of Passau was an attempt to resolve religious tensions in the Holy Roman Empire. After Emperor Charles V won a victory against Protestant forces in the Schmalkaldic War of 1547, he implemented the Augsburg Interim, which largely reaffi ...

. The Peace of Augsburg

The Peace of Augsburg (), also called the Augsburg Settlement, was a treaty between Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor, and the Schmalkaldic League, signed on 25 September 1555 in the German city of Augsburg. It officially ended the religious struggl ...

in 1555 tried to prevent a recurrence by fixing boundaries between the two faiths, using the principle of ''cuius regio, eius religio

() is a Latin phrase which literally means "whose realm, his religion" – meaning that the religion of the ruler was to dictate the religion of those ruled. This legal principle marked a major development in the collective (if not individual) ...

''. Under this, states were designated as either Lutheran

Lutheranism is a major branch of Protestantism that emerged under the work of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German friar and Protestant Reformers, reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practices of the Catholic Church launched ...

, then the most usual form of Protestantism, or Catholic, based on the religion of their ruler. Other provisions protected substantial religious minorities in cities like Donauwörth

Donauwörth (; ) is a town and the capital of the Donau-Ries district in Swabia, Bavaria, Germany. It is said to have been founded by two fishermen where the rivers Danube (Donau) and Wörnitz meet. The city is part of the scenic route called "R ...

, and confirmed Lutheran ownership of property taken from the Catholic Church

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

since 1552.

However, the settlement was undermined by the expansion of Protestantism into Catholic areas post 1555, particularly Calvinism

Reformed Christianity, also called Calvinism, is a major branch of Protestantism that began during the 16th-century Protestant Reformation. In the modern day, it is largely represented by the Continental Reformed Christian, Presbyteri ...

, a Protestant doctrine viewed with hostility by both Lutherans and Catholics. The Augsburg terms also gave individual rulers significantly greater autonomy, allowing larger states to pursue their own objectives. These frequently clashed with those of central authority, and on occasion superseded religion, with the Protestant states of Saxony

Saxony, officially the Free State of Saxony, is a landlocked state of Germany, bordering the states of Brandenburg, Saxony-Anhalt, Thuringia, and Bavaria, as well as the countries of Poland and the Czech Republic. Its capital is Dresden, and ...

, Brandenburg

Brandenburg, officially the State of Brandenburg, is a States of Germany, state in northeastern Germany. Brandenburg borders Poland and the states of Berlin, Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, Lower Saxony, Saxony-Anhalt, and Saxony. It is the List of Ger ...

, Denmark–Norway

Denmark–Norway (Danish language, Danish and Norwegian language, Norwegian: ) is a term for the 16th-to-19th-century multi-national and multi-lingual real unionFeldbæk 1998:11 consisting of the Kingdom of Denmark, the Kingdom of Norway (includ ...

and Swedish Empire, Sweden competing over the lucrative Baltic trade.

Reconciling these differences was hampered by fragmented political institutions, which included 300 imperial estate

An Imperial Estate (; , plural: ') was an entity or an individual of the Holy Roman Empire with representation and the right to vote in the Imperial Diet (Holy Roman Empire), Imperial Diet ('). Rulers of these Estates were able to exercise signi ...

s distributed across Germany, the Low Countries

The Low Countries (; ), historically also known as the Netherlands (), is a coastal lowland region in Northwestern Europe forming the lower Drainage basin, basin of the Rhine–Meuse–Scheldt delta and consisting today of the three modern "Bene ...

, northern Italy

Northern Italy (, , ) is a geographical and cultural region in the northern part of Italy. The Italian National Institute of Statistics defines the region as encompassing the four Northwest Italy, northwestern Regions of Italy, regions of Piedmo ...

, and present-day France. These ranged in size and importance from the seven Prince-elector

The prince-electors ( pl. , , ) were the members of the Electoral College of the Holy Roman Empire, which elected the Holy Roman Emperor. Usually, half of the electors were archbishops.

From the 13th century onwards, a small group of prince- ...

s who voted for the Holy Roman Emperor

The Holy Roman Emperor, originally and officially the Emperor of the Romans (disambiguation), Emperor of the Romans (; ) during the Middle Ages, and also known as the Roman-German Emperor since the early modern period (; ), was the ruler and h ...

, down to Prince-bishop

A prince-bishop is a bishop who is also the civil ruler of some secular principality and sovereignty, as opposed to '' Prince of the Church'' itself, a title associated with cardinals. Since 1951, the sole extant prince-bishop has been the ...

rics and imperial cities like Hamburg

Hamburg (, ; ), officially the Free and Hanseatic City of Hamburg,. is the List of cities in Germany by population, second-largest city in Germany after Berlin and List of cities in the European Union by population within city limits, 7th-lar ...

. Each also belonged to an Imperial Circle", a regional grouping concerned chiefly with defence, and which operated independently of the others. Above all of these was the Imperial Diet, which assembled infrequently, and focused on discussion, rather than legislation.

Although technically elected, since 1440 the position of emperor had been held by the House of Habsburg

The House of Habsburg (; ), also known as the House of Austria, was one of the most powerful Dynasty, dynasties in the history of Europe and Western civilization. They were best known for their inbreeding and for ruling vast realms throughout ...

. The largest single landowner within the Holy Roman Empire, they ruled over eight million subjects, based in territories that included Austria

Austria, formally the Republic of Austria, is a landlocked country in Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine Federal states of Austria, states, of which the capital Vienna is the List of largest cities in Aust ...

, Bohemia

Bohemia ( ; ; ) is the westernmost and largest historical region of the Czech Republic. In a narrow, geographic sense, it roughly encompasses the territories of present-day Czechia that fall within the Elbe River's drainage basin, but historic ...

and Hungary

Hungary is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning much of the Pannonian Basin, Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Croatia and ...

. They also controlled the Spanish Empire

The Spanish Empire, sometimes referred to as the Hispanic Monarchy (political entity), Hispanic Monarchy or the Catholic Monarchy, was a colonial empire that existed between 1492 and 1976. In conjunction with the Portuguese Empire, it ushered ...

until 1556, when Charles V Charles V may refer to:

Kings and Emperors

* Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor (1500–1558)

* Charles V of Naples (1661–1700), better known as Charles II of Spain

* Charles V of France (1338–1380), called the Wise

Others

* Charles V, Duke ...

divided his possessions between different branches of the family. This bond was reinforced by frequent inter-marriage, while Spain

Spain, or the Kingdom of Spain, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe with territories in North Africa. Featuring the Punta de Tarifa, southernmost point of continental Europe, it is the largest country in Southern Eur ...

retained territories within the Holy Roman Empire such as the Spanish Netherlands

The Spanish Netherlands (; ; ; ) (historically in Spanish: , the name "Flanders" was used as a '' pars pro toto'') was the Habsburg Netherlands ruled by the Spanish branch of the Habsburgs from 1556 to 1714. They were a collection of States of t ...

, Milan

Milan ( , , ; ) is a city in northern Italy, regional capital of Lombardy, the largest city in Italy by urban area and the List of cities in Italy, second-most-populous city proper in Italy after Rome. The city proper has a population of nea ...

and Franche-Comté

Franche-Comté (, ; ; Frainc-Comtou dialect, Frainc-Comtou: ''Fraintche-Comtè''; ; also ; ; all ) is a cultural and Provinces of France, historical region of eastern France. It is composed of the modern departments of France, departments of Doub ...

. However, although the two often collaborated, there was no such thing as a joint "Habsburg" policy.

This is because the two entities were very different. Spain was a global maritime superpower, stretching from Europe to the Philippines

The Philippines, officially the Republic of the Philippines, is an Archipelagic state, archipelagic country in Southeast Asia. Located in the western Pacific Ocean, it consists of List of islands of the Philippines, 7,641 islands, with a tot ...

, and the Americas

The Americas, sometimes collectively called America, are a landmass comprising the totality of North America and South America.'' Webster's New World College Dictionary'', 2010 by Wiley Publishing, Inc., Cleveland, Ohio. When viewed as a sin ...

, while Austria was a land-based power, focused on Germany, and securing their eastern border against the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

. Another key difference was the disparity in relative financial strength, with the Spanish providing large subsidies to their Austrian counterparts. The loss of these post 1640, as Spain itself struggled with the costs of a long running global war, substantially weakened the imperial position.

Prior to the Reformation, shared religion partially compensated for weak imperial institutions. After 1556, rising religious and political tensions allowed states like Lutheran Saxony and Catholic Bavaria

Bavaria, officially the Free State of Bavaria, is a States of Germany, state in the southeast of Germany. With an area of , it is the list of German states by area, largest German state by land area, comprising approximately 1/5 of the total l ...

to expand their own power, while further weakening imperial authority. This internal political struggle was exacerbated by external powers with their own strategic objectives, such as Spain, the Dutch Republic

The United Provinces of the Netherlands, commonly referred to in historiography as the Dutch Republic, was a confederation that existed from 1579 until the Batavian Revolution in 1795. It was a predecessor state of the present-day Netherlands ...

, or France, confronted by Habsburg lands on its borders to the north

North is one of the four compass points or cardinal directions. It is the opposite of south and is perpendicular to east and west. ''North'' is a noun, adjective, or adverb indicating Direction (geometry), direction or geography.

Etymology

T ...

, south

South is one of the cardinal directions or compass points. The direction is the opposite of north and is perpendicular to both west and east.

Etymology

The word ''south'' comes from Old English ''sūþ'', from earlier Proto-Germanic ''*sunþa ...

, and along the Pyrenees

The Pyrenees are a mountain range straddling the border of France and Spain. They extend nearly from their union with the Cantabrian Mountains to Cap de Creus on the Mediterranean coast, reaching a maximum elevation of at the peak of Aneto. ...

. Since a number of foreign rulers were also imperial princes, divisions within the empire drew in players like Christian IV of Denmark

Christian IV (12 April 1577 – 28 February 1648) was King of Denmark and King of Norway, Norway and List of rulers of Schleswig-Holstein, Duke of Holstein and Schleswig from 1588 until his death in 1648. His reign of 59 years and 330 days is th ...

, who joined the war in 1625 as Duke of Holstein-Gottorp

Holstein-Gottorp () is the Historiography, historiographical name, as well as contemporary shorthand name, for the parts of the duchies of Duchy of Schleswig, Schleswig and Duchy of Holstein, Holstein, also known as Ducal Holstein, that were rul ...

.

Background: 1556 to 1618

ruler

A ruler, sometimes called a rule, scale, line gauge, or metre/meter stick, is an instrument used to make length measurements, whereby a length is read from a series of markings called "rules" along an edge of the device. Usually, the instr ...

converted to Calvinism. More common were events such as the 1606 "Battle of the Flags" in Donauwörth, when riots broke out after the Lutheran majority blocked a Catholic religious procession. Emperor Rudolf approved intervention by the Catholic Maximilian of Bavaria. In return, he was allowed to annex the town, and as agreed at Augsburg, the official religion changed from Lutheran to Catholic.

When the Imperial Diet opened in February 1608, both Lutherans and Calvinists sought re-confirmation of the Augsburg settlement. In return, the Habsburg heir Archduke Ferdinand required the immediate restoration of any property taken from the Catholic Church since 1555, rather than the previous practice whereby each case was assessed separately. By threatening all Protestants, his demand paralysed the diet, and removed the perception of imperial neutrality.

Loss of faith in central authority meant towns and rulers began strengthening their fortifications and armies, with foreign travellers often commenting on the militarisation of Germany in this period. When Frederick IV, Elector Palatine

Frederick IV, Elector Palatine of the Rhine (; 5 March 1574 – 19 September 1610), only surviving son of Louis VI, Elector Palatine and Elisabeth of Hesse, called "Frederick the Righteous" (; French: ''Frédéric IV le juste'').

Life

Bor ...

formed the Protestant Union

The Protestant Union (), also known as the Evangelical Union, Union of Auhausen, German Union or the Protestant Action Party, was a coalition of Protestant German states. It was formed on 14 May 1608 by Frederick IV, Elector Palatine in order t ...

in 1608, Maximilian responded by setting up the Catholic League in July 1609. Both were largely vehicles for their leaders' dynastic ambitions, but when combined with the 1609 to 1614 War of the Jülich Succession

The War of the Jülich Succession, also known as the Jülich War or the Jülich-Cleves Succession Crises (German language, German: ''Jülich-Klevischer Erbfolgestreit''), was a war of succession in the United Duchies of Jülich-Cleves-Berg. The fi ...

, the result was to increase tensions throughout the empire. Some historians who see the war as primarily a European conflict argue Jülich marks its beginning, with Spain and Austria backing the Catholic candidate, France and the Dutch Republic

The United Provinces of the Netherlands, commonly referred to in historiography as the Dutch Republic, was a confederation that existed from 1579 until the Batavian Revolution in 1795. It was a predecessor state of the present-day Netherlands ...

the Protestant.

External powers became involved in what was an internal German dispute due to the imminent expiry of the 1609 Twelve Years' Truce

The Twelve Years' Truce was a ceasefire during the Eighty Years' War between Habsburg Spain, Spain and the Dutch Republic, agreed in Antwerp on 9 April 1609 and ended on 9 April 1621. While European powers like Kingdom of France, France began tre ...

, which suspended the Eighty Years' War

The Eighty Years' War or Dutch Revolt (; 1566/1568–1648) was an armed conflict in the Habsburg Netherlands between disparate groups of rebels and the Spanish Empire, Spanish government. The Origins of the Eighty Years' War, causes of the w ...

between Spain and the Dutch Republic. Before restarting hostilities, Ambrosio Spinola

Ambrogio Spinola Doria, 1st Marquess of Los Balbases and 1st Duke of Sesto (1569 – 25 September 1630) was an Italian military leader and nobleman of the Republic of Genoa, who served as a Spanish general and won a number of important battles. ...

, commander in the Spanish Netherlands, needed to secure the Spanish Road

The Spanish Road was a military road and trade route linking Spanish territories in Flanders with those in Italy. It was in use from approximately 1567 to 1648.

The Road was created to support the Spanish war effort in the Eighty Years' War ag ...

, an overland route connecting Habsburg possessions in Italy to Flanders

Flanders ( or ; ) is the Dutch language, Dutch-speaking northern portion of Belgium and one of the communities, regions and language areas of Belgium. However, there are several overlapping definitions, including ones related to culture, la ...

. This allowed him to move troops and supplies by road, rather than sea where the Dutch navy was dominant; by 1618, the only part not controlled by Spain ran through the Electoral Palatinate

The Electoral Palatinate was a constituent state of the Holy Roman Empire until it was annexed by the Electorate of Baden in 1803. From the end of the 13th century, its ruler was one of the Prince-electors who elected the Holy Roman Empero ...

.

Since Emperor Matthias had no surviving children, in July 1617 Philip III of Spain

Philip III (; 14 April 1578 – 31 March 1621) was King of Spain and King of Portugal, Portugal (where he is known as Philip II of Portugal) during the Iberian Union. His reign lasted from 1598 until his death in 1621. He held dominion over the S ...

agreed to support Ferdinand II's election as king of Bohemia and Hungary. In return, Ferdinand made concessions to Spain in northern Italy and Alsace, and agreed to support their offensive against the Dutch. Doing so required his election as emperor, which was not guaranteed; Maximilian of Bavaria, who opposed the increase of Spanish influence in an area he considered his own, tried to create a coalition to support his candidacy.

Another option was Frederick V, Elector Palatine Frederick may refer to:

People

* Frederick (given name), the name

Given name

Nobility

= Anhalt-Harzgerode =

* Frederick, Prince of Anhalt-Harzgerode (1613–1670)

= Austria =

* Frederick I, Duke of Austria (Babenberg), Duke of Austria fro ...

, a Calvinist who in 1613 married Elizabeth of Bohemia

Elizabeth Stuart (19 August 1596 – 13 February 1662) was Electress of the Palatinate and briefly Queen of Bohemia as the wife of Frederick V of the Palatinate. The couple's selection for the crown by the nobles of Bohemia was part of the po ...

, daughter of James I of England

James VI and I (James Charles Stuart; 19 June 1566 – 27 March 1625) was King of Scotland as James VI from 24 July 1567 and King of England and Ireland as James I from the union of the Scottish and English crowns on 24 March 1603 unti ...

. Currently, three of the seven electors were Protestant, and four Catholic, so when Ferdinand was elected king of Bohemia in 1617, he also gained control of its electoral vote. However, his conservative Catholicism made him unpopular with the predominantly Protestant Bohemian nobility, who were also concerned about the erosion of their rights. These factors led them to propose replacing Ferdinand, but since Frederick's election would change the religious balance of the electors, this potentially implied a Protestant emperor, and the end of Habsburg predominance. These factors combined to bring about the Bohemian Revolt

The Bohemian Revolt (; ; 1618–1620) was an uprising of the Kingdom of Bohemia, Bohemian Estates of the realm, estates against the rule of the Habsburg dynasty that began the Thirty Years' War. It was caused by both religious and power dispu ...

in May 1618.

Phase I: 1618 to 1635

Bohemian revolt

Ferdinand once claimed he would rather see his lands destroyed than tolerate

Ferdinand once claimed he would rather see his lands destroyed than tolerate heresy

Heresy is any belief or theory that is strongly at variance with established beliefs or customs, particularly the accepted beliefs or religious law of a religious organization. A heretic is a proponent of heresy.

Heresy in Heresy in Christian ...

within them. Less than 18 months after taking control of Styria

Styria ( ; ; ; ) is an Austrian Federal states of Austria, state in the southeast of the country. With an area of approximately , Styria is Austria's second largest state, after Lower Austria. It is bordered to the south by Slovenia, and cloc ...

in 1595, he had eliminated Protestantism in what had been a stronghold of the Reformation

The Reformation, also known as the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation, was a time of major Theology, theological movement in Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the p ...

. Absorbed by their war in the Netherlands, his Spanish relatives preferred to avoid antagonising Protestants elsewhere. They recognised the dangers associated with Ferdinand's fervent Catholicism, but supported his claim due to the lack of alternatives.

On being elected king of Bohemia in May 1617, Ferdinand reconfirmed Protestant religious freedoms, but his record in Styria led to the suspicion he was only awaiting a chance to overturn them. These concerns were heightened after a series of legal disputes over property were all decided in favour of the Catholic Church. In May 1618, Protestant nobles led by Count Thurn met in Prague Castle

Prague Castle (; ) is a castle complex in Prague, Czech Republic serving as the official residence and workplace of the president of the Czech Republic. Built in the 9th century, the castle has long served as the seat of power for List of rulers ...

with Ferdinand's two Catholic representatives, Vilem Slavata and Jaroslav Borzita. In what became known as the Third Defenestration of Prague

The Defenestrations of Prague (, , ) were three incidents in the history of Bohemia in which people were defenestrated (thrown out of a window). Though already existing in Middle French, the word ''defenestrate'' is believed to have first been us ...

, both men were thrown out of the castle windows along with their secretary Filip Fabricius

Filip Fabricius, later of Rosenfeld and Hohenfall (c. 1570, Mikulov – 18 October 1632, Prague) was a Bohemia, Bohemian Catholic officer best known for being thrown out of the Prague Castle window during the Third Defenestration of Prague with tw ...

, although all three survived.

Thurn established a Protestant-dominated government in Bohemia, while unrest expanded into Silesia

Silesia (see names #Etymology, below) is a historical region of Central Europe that lies mostly within Poland, with small parts in the Czech Silesia, Czech Republic and Germany. Its area is approximately , and the population is estimated at 8, ...

and the Habsburg heartlands of Lower

Lower may refer to:

* ''Lower'' (album), 2025 album by Benjamin Booker

*Lower (surname)

*Lower Township, New Jersey

*Lower Receiver (firearms)

*Lower Wick

Lower Wick is a small hamlet located in the county of Gloucestershire, England. It is sit ...

and Upper Austria

Upper Austria ( ; ; ) is one of the nine States of Austria, states of Austria. Its capital is Linz. Upper Austria borders Germany and the Czech Republic, as well as the other Austrian states of Lower Austria, Styria, and Salzburg (state), Salzbur ...

, where much of the nobility was also Protestant. Losing control of these threatened the entire Habsburg state, while in addition to its crucial electoral vote, Bohemia was one of the most prosperous areas of the Empire. Regaining control was vital for the Austrian Habsburgs, but chronic financial weakness left them dependent on Maximilian and Spain for the resources needed to achieve this.

Spanish involvement inevitably drew in the Dutch, and potentially France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

, although the strongly Catholic Louis XIII of France

Louis XIII (; sometimes called the Just; 27 September 1601 – 14 May 1643) was King of France from 1610 until his death in 1643 and King of Navarre (as Louis II) from 1610 to 1620, when the crown of Navarre was merged with the French crown.

...

faced his own Protestant rebels at home and refused to support them elsewhere. The revolt also provided opportunities for external opponents of the Habsburgs, including the Ottoman Empire and Savoy

Savoy (; ) is a cultural-historical region in the Western Alps. Situated on the cultural boundary between Occitania and Piedmont, the area extends from Lake Geneva in the north to the Dauphiné in the south and west and to the Aosta Vall ...

. Funded by Frederick and Charles Emmanuel I, Duke of Savoy

Charles Emmanuel I (; 12 January 1562 – 26 July 1630), known as the Great, was the Duke of Savoy and ruler of the Savoyard states from 30 August 1580 until his death almost 50 years later in 1630, he was the longest-reigning Savoyard monarch ...

, a mercenary army under Ernst von Mansfeld

Peter Ernst, Graf von Mansfeld (; 158029 November 1626), or simply Ernst von Mansfeld, was a German military commander; despite being a Catholic, he fought for the Protestants during the early years of the Thirty Years' War. He was one of the l ...

was sent to support the Bohemian rebels. Attempts by Maximilian and John George of Saxony to broker a negotiated solution ended when Matthias died in March 1619, since many believed the loss of his authority and influence had fatally damaged the Habsburgs.

By mid-June 1619, the Bohemian army under Thurn was outside Vienna

Vienna ( ; ; ) is the capital city, capital, List of largest cities in Austria, most populous city, and one of Federal states of Austria, nine federal states of Austria. It is Austria's primate city, with just over two million inhabitants. ...

and despite Mansfeld's defeat at Sablat, Ferdinand's position continued to worsen. Gabriel Bethlen

Gabriel Bethlen (; 1580 – 15 November 1629) was Prince of Transylvania from 1613 to 1629 and Duke of Opole from 1622 to 1625. He was also King-elect of Hungary from 1620 to 1621, but he never took control of the whole kingdom. Bethlen, sup ...

, Calvinist Prince of Transylvania

The Prince of Transylvania (, , , Fallenbüchl 1988, p. 77.) was the head of state of the Principality of Transylvania from the late-16th century until the mid-18th century. John Sigismund Zápolya was the first to adopt the title in 1 ...

, invaded Hungary with Ottoman support, although the Habsburgs persuaded them to avoid direct involvement. This was helped by Ottomans involvement first in the 1620 Polish war, then the 1623 to 1639 conflict with Persia.

On 19 August, the Bohemian Estates rescinded Ferdinand's 1617 election as king and a week later formally offered the crown to Frederick. On 28 August, Ferdinand was elected Holy Roman Emperor, making war inevitable if Frederick accepted the Bohemian crown. Most of Frederick's advisors urged him to reject it, as did the Duke of Savoy, and his father-in-law James I. The exceptions included Christian of Anhalt and Maurice of Orange, for whom conflict in Germany was a means to divert Spanish resources from the Netherlands. The Dutch offered subsidies to Frederick and the Protestant Union, helped raise loans for Bohemia, and provided weapons and munitions. However, wider European support failed to materialise, largely due to lack of enthusiasm for removing a legally elected ruler, regardless of religion.

Although Frederick accepted the crown and entered Prague in October 1619, his support eroded over the next few months. In July 1620, the Protestant Union proclaimed its neutrality, while John George of Saxony backed Ferdinand in return for the cession of

On 19 August, the Bohemian Estates rescinded Ferdinand's 1617 election as king and a week later formally offered the crown to Frederick. On 28 August, Ferdinand was elected Holy Roman Emperor, making war inevitable if Frederick accepted the Bohemian crown. Most of Frederick's advisors urged him to reject it, as did the Duke of Savoy, and his father-in-law James I. The exceptions included Christian of Anhalt and Maurice of Orange, for whom conflict in Germany was a means to divert Spanish resources from the Netherlands. The Dutch offered subsidies to Frederick and the Protestant Union, helped raise loans for Bohemia, and provided weapons and munitions. However, wider European support failed to materialise, largely due to lack of enthusiasm for removing a legally elected ruler, regardless of religion.

Although Frederick accepted the crown and entered Prague in October 1619, his support eroded over the next few months. In July 1620, the Protestant Union proclaimed its neutrality, while John George of Saxony backed Ferdinand in return for the cession of Lusatia

Lusatia (; ; ; ; ; ), otherwise known as Sorbia, is a region in Central Europe, formerly entirely in Germany and today territorially split between Germany and modern-day Poland. Lusatia stretches from the Bóbr and Kwisa rivers in the eas ...

, and a guarantee of Lutheran rights in Bohemia. Maximilian of Bavaria funded a combined Imperial-Catholic League army led by Count Tilly and Charles of Bucquoy, which pacified Upper and Lower Austria and occupied western Bohemia before marching on Prague. Defeated by Tilly at the Battle of White Mountain

The Battle of White Mountain (; ) was an important battle in the early stages of the Thirty Years' War. It led to the defeat of the Bohemian Revolt and ensured Habsburg control for the next three hundred years.

It was fought on 8 November 16 ...

in November 1620, the Bohemian army disintegrated, and Frederick was forced to flee the country.

Palatinate campaign

By abandoning Frederick, the German princes had hoped to restrict the dispute to Bohemia, but this was thwarted by Maximilian's dynastic ambitions. In the October 1619 Treaty of Munich, Ferdinand transferred the Palatinate's electoral vote to Bavaria, and allowed Maximilian to annex theUpper Palatinate

The Upper Palatinate (; , , ) is an administrative district in the east of Bavaria, Germany. It consists of seven districts and 226 municipalities, including three cities.

Geography

The Upper Palatinate is a landscape with low mountains and nume ...

. Many Protestants had supported Ferdinand because in principle they opposed the deposition of a legally elected ruler, and now objected to Frederick's removal on the same grounds. For Catholics, it presented an opportunity to regain lands and properties lost since 1555, a combination which destabilised large parts of the Empire.

At the same time, Spain was drawn into the conflict due to the strategic importance of the Spanish Road for their war in the Netherlands, and its proximity to the Palatinate. When an army led by Córdoba occupied the Lower Palatinate

The Palatinate (; ; Palatine German: ''Palz''), or the Rhenish Palatinate (''Rheinpfalz''), is a historical region of Germany. The Palatinate occupies most of the southern quarter of the German federal state of Rhineland-Palatinate (''Rheinl ...

in October 1619, James I sent English naval forces against Spanish colonial possessions and threatened war if Spanish troops were not withdrawn by spring 1621. These actions were primarily designed to placate his opponents in Parliament

In modern politics and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

, who considered his pro-Spanish policy a betrayal of the Protestant cause. Spanish chief minister Olivares correctly interpreted them as an invitation to open negotiations, and in return for an Anglo-Spanish alliance offered to restore Frederick to his Rhineland possessions.

Since Frederick's demand for full restitution of his lands and titles was incompatible with the Treaty of Munich, hopes of a negotiated peace quickly evaporated. Despite defeat in Bohemia, Frederick's allies included Georg Friedrich of Baden and Christian of Brunswick, while the Dutch provided him with military support after the Eighty Years' War restarted in April 1621 and his father-in-law James funded an army of mercenaries under Mansfeld. However, their failure to co-ordinate effectively led to a series of defeats by Spanish and Catholic League forces, including Wimpfen

Bad Wimpfen () is a historic spa town in the Heilbronn (district), district of Heilbronn in the Baden-Württemberg region of southern Germany. It lies north of the city of Heilbronn, on the river Neckar.

Geography

Bad Wimpfen is located on the w ...

in May 1622 and Höchst in June. By November 1622, Spanish and imperial troops controlled most of the Palatinate, apart from Frankenthal

Frankenthal (Pfalz) (; ) is a town in southwestern Germany, in the state of Rhineland-Palatinate.

History

Frankenthal was first mentioned in 772. In 1119 an Augustinians, Augustinian monastery was built here, the ruins of which — known, aft ...

, which was held by a small English garrison under Sir Horace Vere

Horace Vere, 1st Baron Vere of Tilbury (1565 – 2 May 1635) was an English army officer who served in the Eighty Years' War and the Thirty Years' War. A brother of Francis Vere, he was sent to the Electoral Palatinate by James VI and I in 1620. ...

. The remnants of Mansfeld's army took refuge in the Dutch Republic, as did Frederick, who spent most of his time in The Hague

The Hague ( ) is the capital city of the South Holland province of the Netherlands. With a population of over half a million, it is the third-largest city in the Netherlands. Situated on the west coast facing the North Sea, The Hague is the c ...

until his death in November 1632.

At a meeting of the Imperial Diet in February 1623, Ferdinand forced through provisions transferring Frederick's titles, lands, and electoral vote to Maximilian. He did so with support from the Catholic League, despite strong opposition from Protestant members, as well as the Spanish. The Palatinate was clearly lost; in March, James instructed Vere to surrender Frankenthal, while Tilly's victory over Christian of Brunswick at Stadtlohn

Stadtlohn (; ) is a city in western Münsterland in the northwest of North Rhine-Westphalia, and is a district town of the Borken administrative district. The city had a population of 20,746 inhabitants as of 2020.Upper Saxon Circle

The Upper Saxon Circle () was an Imperial Circle of the Holy Roman Empire, created in 1512.

The circle was dominated by the electorate of Saxony (the circle's director) and the electorate of Margraviate of Brandenburg, Brandenburg. It further co ...

and Brandenburg

Brandenburg, officially the State of Brandenburg, is a States of Germany, state in northeastern Germany. Brandenburg borders Poland and the states of Berlin, Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, Lower Saxony, Saxony-Anhalt, and Saxony. It is the List of Ger ...

the Lower

Lower may refer to:

* ''Lower'' (album), 2025 album by Benjamin Booker

*Lower (surname)

*Lower Township, New Jersey

*Lower Receiver (firearms)

*Lower Wick

Lower Wick is a small hamlet located in the county of Gloucestershire, England. It is sit ...

, both ''kreise'' had remained neutral during the campaigns in Bohemia and the Palatinate. However, Frederick's deposition in 1623 meant John George of Saxony and the Calvinist George William, Elector of Brandenburg

George William (; 13 November 1595 – 1 December 1640), of the Hohenzollern dynasty, was Margrave and Elector of Brandenburg and Duke of Prussia from 1619 until his death. His reign was marked by ineffective governance during the Thirty Years' ...

became concerned Ferdinand intended to reclaim formerly Catholic bishoprics currently held by Protestants. These fears seemed confirmed when Tilly restored the Roman Catholic Diocese of Halberstadt

The Diocese of Halberstadt was a Roman Catholic diocese () from 804 until 1648."Dio ...

in early 1625.

As Duke of Holstein, Christian IV was also a member of the Lower Saxon circle, while the Danish economy relied on the Baltic trade and tolls from traffic through the Øresund

Øresund or Öresund (, ; ; ), commonly known in English as the Sound, is a strait which forms the Denmark–Sweden border, Danish–Swedish border, separating Zealand (Denmark) from Scania (Sweden). The strait has a length of ; its width var ...

. In 1621, Hamburg accepted Danish "supervision", while his son Frederick Frederick may refer to:

People

* Frederick (given name), the name

Given name

Nobility

= Anhalt-Harzgerode =

* Frederick, Prince of Anhalt-Harzgerode (1613–1670)

= Austria =

* Frederick I, Duke of Austria (Babenberg), Duke of Austria fro ...

became joint-administrator of Lübeck

Lübeck (; or ; Latin: ), officially the Hanseatic League, Hanseatic City of Lübeck (), is a city in Northern Germany. With around 220,000 inhabitants, it is the second-largest city on the German Baltic Sea, Baltic coast and the second-larg ...

, Bremen

Bremen (Low German also: ''Breem'' or ''Bräm''), officially the City Municipality of Bremen (, ), is the capital of the States of Germany, German state of the Bremen (state), Free Hanseatic City of Bremen (), a two-city-state consisting of the c ...

, and Verden; possession ensured Danish control of the Elbe

The Elbe ( ; ; or ''Elv''; Upper Sorbian, Upper and , ) is one of the major rivers of Central Europe. It rises in the Giant Mountains of the northern Czech Republic before traversing much of Bohemia (western half of the Czech Republic), then Ge ...

and Weser

The Weser () is a river of Lower Saxony in north-west Germany. It begins at Hannoversch Münden through the confluence of the Werra and Fulda. It passes through the Hanseatic city of Bremen. Its mouth is further north against the ports o ...

rivers.

Ferdinand had paid Albrecht von Wallenstein

Albrecht Wenzel Eusebius von Wallenstein, Duke of Friedland (; 24 September 1583 – 25 February 1634), also von Waldstein (), was a Bohemian military leader and statesman who fought on the Catholic side during the Thirty Years' War (1618–16 ...

for his support against Frederick with estates confiscated from the Bohemian rebels, and now contracted with him to conquer the north on a similar basis. In May 1625, the Lower Saxony ''kreis'' elected Christian their military commander, although not without resistance; Saxony and Brandenburg viewed Denmark and Sweden as competitors, and wanted to avoid either becoming involved in the empire. Attempts to negotiate a peaceful solution failed as the conflict in Germany became part of the wider struggle between France and their Habsburg rivals in Spain and Austria.

In the June 1624 Treaty of Compiègne, France had agreed to subsidise the Dutch war against Spain for a minimum of three years, while in the December 1625 Treaty of The Hague, the Dutch and English agreed to finance Danish intervention in the Empire. Hoping to create a wider coalition against Ferdinand, the Dutch invited France, Sweden, Savoy, and the Republic of Venice

The Republic of Venice, officially the Most Serene Republic of Venice and traditionally known as La Serenissima, was a sovereign state and Maritime republics, maritime republic with its capital in Venice. Founded, according to tradition, in 697 ...

to join, but it was overtaken by events. In early 1626, Cardinal Richelieu

Armand Jean du Plessis, 1st Duke of Richelieu (9 September 1585 – 4 December 1642), commonly known as Cardinal Richelieu, was a Catholic Church in France, French Catholic prelate and statesman who had an outsized influence in civil and religi ...

, main architect of the alliance, faced a new Huguenot rebellion at home and in the March Treaty of Monzón

The Treaty of Monçon or Treaty of Monzón was signed on 5 March 1626 by Cardinal Richelieu, the chief minister of Louis XIII and Gaspar de Guzmán, Count-Duke of Olivares, the chief minister of Philip IV of Spain, at Monzón, Monçon (modern Monz� ...

, France withdrew from northern Italy, re-opening the Spanish Road.

Dutch and English subsidies enabled Christian to devise an ambitious three part campaign plan. While he led the main force down the Weser, Mansfeld would attack Wallenstein in

Dutch and English subsidies enabled Christian to devise an ambitious three part campaign plan. While he led the main force down the Weser, Mansfeld would attack Wallenstein in Magdeburg

Magdeburg (; ) is the Capital city, capital of the Germany, German States of Germany, state Saxony-Anhalt. The city is on the Elbe river.

Otto I, Holy Roman Emperor, Otto I, the first Holy Roman Emperor and founder of the Archbishopric of Mag ...

, supported by forces led by Christian of Brunswick and Maurice of Hesse-Kassel

Maurice of Hesse-Kassel (; 25 May 1572 – 15 March 1632), also called Maurice the Learned or Moritz, was the Landgrave of Hesse-Kassel (or Hesse-Cassel) in the Holy Roman Empire from 1592 to 1627.

Life

Maurice was born in Kassel as the son of ...

. However, Mansfeld was defeated at Dessau Bridge in April, and when Maurice refused to support him, Christian of Brunswick fell back on Wolfenbüttel

Wolfenbüttel (; ) is a town in Lower Saxony, Germany, the administrative capital of Wolfenbüttel District

Wolfenbüttel (; ) is a town in Lower Saxony, Germany, the administrative capital of Wolfenbüttel (district), Wolfenbüttel Distri ...

, where he died of disease shortly after. The Danes were comprehensively beaten at Lutter in August, and Mansfeld's army dissolved after his death in November.

Many of Christian's German allies, such as Hesse-Kassel

The Landgraviate of Hesse-Kassel (), spelled Hesse-Cassel during its entire existence, also known as the Hessian Palatinate (), was a state of the Holy Roman Empire. The state was created in 1567 when the Landgraviate of Hesse was divided upon t ...

and Saxony, had little interest in replacing imperial domination with Danish, while few of the Dutch or English subsidies were ever paid. Charles I of England

Charles I (19 November 1600 – 30 January 1649) was King of Kingdom of England, England, Kingdom of Scotland, Scotland, and Kingdom of Ireland, Ireland from 27 March 1625 until Execution of Charles I, his execution in 1649.

Charles was born ...

allowed Christian to recruit up to 9,000 Scottish mercenaries, but they took time to arrive, and although able to slow Wallenstein's advance were insufficient to stop him. By the end of 1627, Wallenstein had occupied Mecklenburg

Mecklenburg (; ) is a historical region in northern Germany comprising the western and larger part of the federal-state Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania. The largest cities of the region are Rostock, Schwerin, Neubrandenburg, Wismar and Güstrow. ...

, Pomerania

Pomerania ( ; ; ; ) is a historical region on the southern shore of the Baltic Sea in Central Europe, split between Poland and Germany. The central and eastern part belongs to the West Pomeranian Voivodeship, West Pomeranian, Pomeranian Voivod ...

, and Jutland

Jutland (; , ''Jyske Halvø'' or ''Cimbriske Halvø''; , ''Kimbrische Halbinsel'' or ''Jütische Halbinsel'') is a peninsula of Northern Europe that forms the continental portion of Denmark and part of northern Germany (Schleswig-Holstein). It ...

, and began making plans to construct a fleet capable of challenging Danish control of the Baltic. He was supported by Spain, for whom it provided an opportunity to open another front against the Dutch.

On 13 May 1628, his deputy von Arnim besieged Stralsund

Stralsund (; Swedish language, Swedish: ''Strålsund''), officially the Hanseatic League, Hanseatic City of Stralsund (German language, German: ''Hansestadt Stralsund''), is the fifth-largest city in the northeastern German federal state of Mecklen ...

, the only port with facilities large enough to build this fleet. Gustavus Adolphus

Gustavus Adolphus (9 December N.S 19 December">Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="/nowiki>Old Style and New Style dates">N.S 19 December15946 November Old Style and New Style dates">N.S 16 November] 1632), also known in English as ...

responded by sending several thousand men to Stralsund under Alexander Leslie

Alexander Leslie, 1st Earl of Leven (4 April 1661) was a Scottish army officer. Born illegitimate and raised as a foster child, he subsequently advanced to the rank of field marshal in Swedish Army, and in Scotland became Lord General in comma ...

, who was also appointed governor. Von Arnim abandoned the siege on 4 August, but three weeks later Christian suffered another defeat at Wolgast

Wolgast () is a town in the district of Vorpommern-Greifswald, in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, Germany. It is situated on the bank of the river (or strait) Peenestrom, vis-a-vis the island of Usedom on the Baltic Sea, Baltic coast that can be accessed ...

. He began negotiations with Wallenstein, who despite his recent victories was concerned by the prospect of Swedish intervention, and thus anxious to make peace.

With Ferdinand's resources stretched by the outbreak of the

With Ferdinand's resources stretched by the outbreak of the War of the Mantuan Succession

The War of the Mantuan Succession, from 1628 to 1631, was caused by the death in December 1627 of Vincenzo II, last male heir from the House of Gonzaga, long-time rulers of Mantua and Montferrat. Their strategic importance led to a proxy war b ...

, Wallenstein persuaded him to agree relatively lenient terms in the June 1629 Treaty of Lübeck

The Treaty or Peace of Lübeck (, ) ended the Danish intervention in the Thirty Years' War (Low Saxon or Emperor's War, Kejserkrigen). It was signed in Lübeck on 22 May 1629 by Albrecht von Wallenstein and Christian IV of Denmark-Norway, and o ...

. These allowed Christian to retain Schleswig

The Duchy of Schleswig (; ; ; ; ; ) was a duchy in Southern Jutland () covering the area between about 60 km (35 miles) north and 70 km (45 mi) south of the current border between Germany and Denmark. The territory has been di ...

and Holstein in return for relinquishing Bremen and Verden, and abandoning support for the German Protestants. While Denmark kept Schleswig and Holstein until 1864, this effectively ended its reign as the predominant Nordic state.

Once again, the methods used to obtain victory explain why the war failed to end. Ferdinand paid Wallenstein by letting him confiscate estates, extort ransoms from towns, and allowing his men to plunder the lands they passed through, regardless of whether they belonged to allies or opponents. In early 1628, Ferdinand deposed the hereditary Duke of Mecklenburg, and appointed Wallenstein in his place, an act which united all German princes in opposition, regardless of religion. This unity was undermined by Maximilian of Bavaria's desire to retain the Palatinate; as a result, the Catholic League argued only for a return to the position prevailing pre-1627, while Protestants wanted that of 1618.

Made overconfident by success, in March 1629 Ferdinand passed an Edict of Restitution

The Edict of Restitution was proclaimed by Ferdinand II, Holy Roman Emperor in Vienna, on 6 March 1629, eleven years into the Thirty Years' War. Following Catholic League (German), Catholic military successes, Ferdinand hoped to restore control ...

, which required all lands taken from the Catholic church after 1555 to be returned. While technically legal, politically it was extremely unwise, since doing so would alter nearly every single state boundary in north and central Germany, deny the existence of Calvinism and restore Catholicism in areas where it had not been a significant presence for nearly a century. Well aware none of the princes involved would agree, Ferdinand used the device of an imperial edict

An edict is a decree or announcement of a law, often associated with monarchies, but it can be under any official authority. Synonyms include "dictum" and "pronouncement". ''Edict'' derives from the Latin edictum.

Notable edicts

* Telepinu ...

, once again asserting his right to alter laws without consultation. This new assault on "German liberties" ensured continuing opposition and undermined his previous success.

At the same time, his Spanish allies were reluctant to antagonise German Protestants as the Eighty Years' War

The Eighty Years' War or Dutch Revolt (; 1566/1568–1648) was an armed conflict in the Habsburg Netherlands between disparate groups of rebels and the Spanish Empire, Spanish government. The Origins of the Eighty Years' War, causes of the w ...

had now shifted in favour of the Dutch Republic. Madrid's financial position steadily deteriorated in the 1620s, particularly after the Dutch West India Company

The Dutch West India Company () was a Dutch chartered company that was founded in 1621 and went defunct in 1792. Among its founders were Reynier Pauw, Willem Usselincx (1567–1647), and Jessé de Forest (1576–1624). On 3 June 1621, it was gra ...

captured the Spanish treasure fleet

The Spanish treasure fleet, or West Indies Fleet (, also called silver fleet or plate fleet; from the meaning "silver"), was a convoy system of sea routes organized by the Spanish Empire from 1566 to 1790, which linked Spain with its Spanish Empi ...

at Matanzas

Matanzas (Cuban ; ) is the capital of the Cuban province of Matanzas Province, Matanzas. Known for its poets, culture, and Afro-American religions, Afro-Cuban folklore, it is located on the northern shore of the island of Cuba, on the Bay of Mat ...

in 1628. Fighting in Italy diverted Spanish resources from the Netherlands, where Frederick Henry, Prince of Orange

Frederick Henry (; 29 January 1584 – 14 March 1647) was the sovereign prince of Orange and stadtholder of Holland, Zeeland, Utrecht, Guelders, and Overijssel in the Dutch Republic from his older half-brother's death on 23 April 1625 until his ...

captured 's-Hertogenbosch

s-Hertogenbosch (), colloquially known as Den Bosch (), is a List of cities in the Netherlands by province, city and List of municipalities of the Netherlands, municipality in the Netherlands with a population of 160,783. It is the capital of ...

in 1629.

Sweden invades Germany (1630–1635)

Sigismund Sigismund (variants: Sigmund, Siegmund) is a German proper name, meaning "protection through victory", from Old High German ''sigu'' "victory" + ''munt'' "hand, protection". Tacitus latinises it ''Segimundus''. There appears to be an older form of ...

, who also claimed the Swedish throne and was backed by Ferdinand II. Once this conflict ended, and with only a few minor states like Hesse-Kassel

The Landgraviate of Hesse-Kassel (), spelled Hesse-Cassel during its entire existence, also known as the Hessian Palatinate (), was a state of the Holy Roman Empire. The state was created in 1567 when the Landgraviate of Hesse was divided upon t ...

still openly opposing Ferdinand, Gustavus became an obvious ally for Richelieu. In September 1629, the latter helped negotiate the Truce of Altmark between Sweden and Poland, freeing Gustavus to enter the war. Partly a genuine desire to support his Protestant co-religionists, like Christian he also wanted to maximise his share of the Baltic trade that provided much of Sweden's income.

Following failed negotiations with Ferdinand II, Gustavus landed in Pomerania

Pomerania ( ; ; ; ) is a historical region on the southern shore of the Baltic Sea in Central Europe, split between Poland and Germany. The central and eastern part belongs to the West Pomeranian Voivodeship, West Pomeranian, Pomeranian Voivod ...

in June 1630 with nearly 18,000 Swedish troops. Using Stralsund as a bridgehead, he marched south along the Oder

The Oder ( ; Czech and ) is a river in Central Europe. It is Poland's second-longest river and third-longest within its borders after the Vistula and its largest tributary the Warta. The Oder rises in the Czech Republic and flows through wes ...

towards Stettin

Szczecin ( , , ; ; ; or ) is the capital and largest city of the West Pomeranian Voivodeship in northwestern Poland. Located near the Baltic Sea and the German border, it is a major seaport, the largest city of northwestern Poland, and se ...

and coerced Bogislaw XIV, Duke of Pomerania, into agreeing an alliance

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or sovereign state, states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not an explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an a ...

which secured his interests in Pomerania against his rival Sigismund. As a result, the Poles turned their attention to Russia, initiating the 1632 to 1634 Smolensk War

The Smolensk War (1632–1634) was a conflict fought between the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth and Russia.

Hostilities began in October 1632 when Russian forces tried to capture the city of Smolensk. Small military engagements produced mix ...

.

However, Swedish expectations of widespread German support proved unrealistic. By the end of 1630, their only new ally was the Administrator of Magdeburg, Christian William whose capital was under siege by Tilly. Despite the devastation inflicted by imperial soldiers, Saxony and Brandenburg had their own ambitions in Pomerania, which clashed with those of Gustavus; previous experience also showed inviting external powers into the Empire was easier than getting them to leave.

Gustavus put pressure on Brandenburg by sacking Küstrin and

Gustavus put pressure on Brandenburg by sacking Küstrin and Frankfurt an der Oder

Frankfurt (Oder), also known as Frankfurt an der Oder (, ; Marchian dialects, Central Marchian: ''Frankfort an de Oder,'' ) is the fourth-largest city in the German state of Brandenburg after Potsdam, Cottbus and Brandenburg an der Havel. With a ...

, while the Sack of Magdeburg

The Sack of Magdeburg, also called Magdeburg's Wedding () or Magdeburg's Sacrifice (), was the destruction of the Protestant city of Magdeburg on 20 May 1631 by the Imperial Army and the forces of the Catholic League, resulting in the deaths ...

in May 1631 provided a powerful warning of the consequences of imperial victory. Once again, Richelieu used French financial power to bridge differences between the Swedes and the German princes; the 1631 Treaty of Bärwalde

The Treaty of Bärwalde (; ; ), signed on 23 January 1631, was an agreement by France to provide Sweden financial support, following its intervention in the Thirty Years' War.

This was in line with Cardinal Richelieu's policy of avoiding direct ...

provided funds for the Swedes and their Protestant allies, including Saxony and Brandenburg. These amounted to 400,000 Reichstaler

The ''Reichsthaler'' (; modern spelling Reichstaler), or more specifically the ''Reichsthaler specie'', was a standard thaler silver coin introduced by the Holy Roman Empire in 1566 for use in all German states, minted in various versions for the ...

per year, or one million livres, plus an additional 120,000 for 1630. While less than 2% of total French income, these payments boosted that of Sweden by more than 25%, and allowed Gustavus to maintain 36,000 troops.

Gustavus used this army to win victories at Breitenfeld in September 1631, then Rain

Rain is a form of precipitation where water drop (liquid), droplets that have condensation, condensed from Water vapor#In Earth's atmosphere, atmospheric water vapor fall under gravity. Rain is a major component of the water cycle and is res ...

in April 1632, where Tilly was killed. Ferdinand turned once again to Wallenstein, who realised Gustavus was overextended and established himself at Fürth

Fürth (; East Franconian German, East Franconian: ; ) is a List of cities and towns in Germany, city in northern Bavaria, Germany, in the administrative division (''Regierungsbezirk'') of Middle Franconia.

It is the Franconia#Towns and cities, s ...

, from where he could threaten his supply lines. This led to the Battle of the Alte Veste