Syracuse,Sicily on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Syracuse ( ; ; ) is a historic city on the

Syracuse and its surrounding area have been inhabited since ancient times, as shown by the findings in the villages of Stentinello, Ognina, Plemmirio, Matrensa, Cozzo Pantano and ''Thapsos'', which already had a relationship with

Syracuse and its surrounding area have been inhabited since ancient times, as shown by the findings in the villages of Stentinello, Ognina, Plemmirio, Matrensa, Cozzo Pantano and ''Thapsos'', which already had a relationship with

The descendants of the first colonists, called ''Gamoroi'', held power until they were expelled by the lower class of the city assisted by Cyllyrians, identified as enslaved natives similar in status to the

The descendants of the first colonists, called ''Gamoroi'', held power until they were expelled by the lower class of the city assisted by Cyllyrians, identified as enslaved natives similar in status to the

After Timoleon's death the struggle among the city's parties restarted and ended with the rise of another tyrant,

After Timoleon's death the struggle among the city's parties restarted and ended with the rise of another tyrant,

Though declining slowly through the years, Syracuse maintained the status of capital of the Roman government of Sicily and seat of the

Though declining slowly through the years, Syracuse maintained the status of capital of the Roman government of Sicily and seat of the

*

*

* Castello Maniace, constructed between 1232 and 1240, is an example of the military architecture of Frederick II's reign. It is a square structure with circular towers at each of the four corners. The most striking feature is the pointed portal, decorated with polychrome marbles.

* ''Archaeological Museum'' with collections including findings from the mid-Bronze Age to 5th century BC.

* ''Palazzo Lanza Buccheri'' (16th century).

* '' Palazzo Bellomo'' (12th century), which contains an art museum that houses

* Castello Maniace, constructed between 1232 and 1240, is an example of the military architecture of Frederick II's reign. It is a square structure with circular towers at each of the four corners. The most striking feature is the pointed portal, decorated with polychrome marbles.

* ''Archaeological Museum'' with collections including findings from the mid-Bronze Age to 5th century BC.

* ''Palazzo Lanza Buccheri'' (16th century).

* '' Palazzo Bellomo'' (12th century), which contains an art museum that houses

Coins from ancient Syracuse and Sicily

Photos of Ortigia in Syracuse

{{Authority control 8th-century BC establishments in Italy Archaeological sites in Sicily Cities and towns in Sicily Coastal towns in Sicily Corinthian colonies Dorian colonies in Magna Graecia Mediterranean port cities and towns in Italy Municipalities of the Province of Syracuse Populated places established in the 8th century BC Sicilian Baroque World Heritage Sites in Italy Greek city-states

Italian

Italian(s) may refer to:

* Anything of, from, or related to the people of Italy over the centuries

** Italians, a Romance ethnic group related to or simply a citizen of the Italian Republic or Italian Kingdom

** Italian language, a Romance languag ...

island of Sicily

Sicily (Italian language, Italian and ), officially the Sicilian Region (), is an island in the central Mediterranean Sea, south of the Italian Peninsula in continental Europe and is one of the 20 regions of Italy, regions of Italy. With 4. ...

, the capital of the Italian province of Syracuse

The province of Syracuse (; ) was a Provinces of Italy, province in the autonomous island region of Sicily, Italy. Its capital was the city of Syracuse, Sicily, Syracuse, a town established by Greeks, Greek colonists arriving from Corinth in the ...

. The city is notable for its rich Greek and Roman history, culture

Culture ( ) is a concept that encompasses the social behavior, institutions, and Social norm, norms found in human societies, as well as the knowledge, beliefs, arts, laws, Social norm, customs, capabilities, Attitude (psychology), attitudes ...

, amphitheatre

An amphitheatre (American English, U.S. English: amphitheater) is an open-air venue used for entertainment, performances, and sports. The term derives from the ancient Greek ('), from ('), meaning "on both sides" or "around" and ('), meani ...

s, architecture, and as the birthplace and home of the pre-eminent mathematician and engineer Archimedes

Archimedes of Syracuse ( ; ) was an Ancient Greece, Ancient Greek Greek mathematics, mathematician, physicist, engineer, astronomer, and Invention, inventor from the ancient city of Syracuse, Sicily, Syracuse in History of Greek and Hellenis ...

. This 2,700-year-old city played a key role in ancient times, when it was one of the major powers of the Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea ( ) is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the east by the Levant in West Asia, on the north by Anatolia in West Asia and Southern ...

world. Syracuse is located in the southeast corner of the island of Sicily, next to the Gulf of Syracuse beside the Ionian Sea

The Ionian Sea (, ; or , ; , ) is an elongated bay of the Mediterranean Sea. It is connected to the Adriatic Sea to the north, and is bounded by Southern Italy, including Basilicata, Calabria, Sicily, and the Salento peninsula to the west, ...

. It is situated in a drastic rise of land with depths being close to the city offshore although the city itself is generally not so hilly in comparison.

The city was founded by Ancient Greek

Ancient Greek (, ; ) includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the classical antiquity, ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Greek ...

Corinthians

The First Epistle to the Corinthians () is one of the Pauline epistles, part of the New Testament of the Christian Bible. The epistle is attributed to Paul the Apostle and a co-author, Sosthenes, and is addressed to the Christian church in C ...

and Tenea

Tenea () is a municipal unit within the municipality of Corinth (municipality), Corinth, Corinthia, Peloponnese (region), Peloponnese, Greece. The municipal unit has an area of . Until 2011, its municipal seat was in Chiliomodi.

The modern city ...

ns and became a very powerful city-state

A city-state is an independent sovereign city which serves as the center of political, economic, and cultural life over its contiguous territory. They have existed in many parts of the world throughout history, including cities such as Rome, ...

. Syracuse was allied with Sparta

Sparta was a prominent city-state in Laconia in ancient Greece. In antiquity, the city-state was known as Lacedaemon (), while the name Sparta referred to its main settlement in the Evrotas Valley, valley of Evrotas (river), Evrotas rive ...

and Corinth

Corinth ( ; , ) is a municipality in Corinthia in Greece. The successor to the ancient Corinth, ancient city of Corinth, it is a former municipality in Corinthia, Peloponnese (region), Peloponnese, which is located in south-central Greece. Sin ...

and exerted influence over the entirety of Magna Graecia

Magna Graecia refers to the Greek-speaking areas of southern Italy, encompassing the modern Regions of Italy, Italian regions of Calabria, Apulia, Basilicata, Campania, and Sicily. These regions were Greek colonisation, extensively settled by G ...

, of which it was the most important city. Described by Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero ( ; ; 3 January 106 BC – 7 December 43 BC) was a Roman statesman, lawyer, scholar, philosopher, orator, writer and Academic skeptic, who tried to uphold optimate principles during the political crises tha ...

as "the greatest Greek city and the most beautiful of them all", it equalled Athens

Athens ( ) is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Greece, largest city of Greece. A significant coastal urban area in the Mediterranean, Athens is also the capital of the Attica (region), Attica region and is the southe ...

in size during the fifth century BC. It later became part of the Roman Republic

The Roman Republic ( ) was the era of Ancient Rome, classical Roman civilisation beginning with Overthrow of the Roman monarchy, the overthrow of the Roman Kingdom (traditionally dated to 509 BC) and ending in 27 BC with the establis ...

and the Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also known as the Eastern Roman Empire, was the continuation of the Roman Empire centred on Constantinople during late antiquity and the Middle Ages. Having survived History of the Roman Empire, the events that caused the ...

. Under Emperor Constans II

Constans II (; 7 November 630 – 15 July 668), also called "the Bearded" (), was the Byzantine emperor from 641 to 668. Constans was the last attested emperor to serve as Roman consul, consul, in 642, although the office continued to exist unti ...

, it served as the capital of the Byzantine Empire (663–669). Palermo

Palermo ( ; ; , locally also or ) is a city in southern Italy, the capital (political), capital of both the autonomous area, autonomous region of Sicily and the Metropolitan City of Palermo, the city's surrounding metropolitan province. The ...

later overtook it in importance, as the capital of the Kingdom of Sicily

The Kingdom of Sicily (; ; ) was a state that existed in Sicily and the southern Italian peninsula, Italian Peninsula as well as, for a time, in Kingdom of Africa, Northern Africa, from its founding by Roger II of Sicily in 1130 until 1816. It was ...

. Eventually the kingdom would be united with the Kingdom of Naples

The Kingdom of Naples (; ; ), officially the Kingdom of Sicily, was a state that ruled the part of the Italian Peninsula south of the Papal States between 1282 and 1816. It was established by the War of the Sicilian Vespers (1282–1302). Until ...

to form the Two Sicilies

The Kingdom of the Two Sicilies () was a kingdom in Southern Italy from 1816 to 1861 under the control of the House of Bourbon-Two Sicilies, a cadet branch of the Bourbons. The kingdom was the largest sovereign state by population and land are ...

until the Italian unification

The unification of Italy ( ), also known as the Risorgimento (; ), was the 19th century political and social movement that in 1861 ended in the annexation of various states of the Italian peninsula and its outlying isles to the Kingdom of ...

of 1860.

In the modern day, the city is listed by UNESCO

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO ) is a List of specialized agencies of the United Nations, specialized agency of the United Nations (UN) with the aim of promoting world peace and International secur ...

as a World Heritage Site

World Heritage Sites are landmarks and areas with legal protection under an treaty, international treaty administered by UNESCO for having cultural, historical, or scientific significance. The sites are judged to contain "cultural and natural ...

along with the Necropolis of Pantalica

The Necropolis of Pantalica is a collection of cemeteries with rock-cut chamber tombs in southeast Sicily, Italy. Dating from the 13th to the 7th centuries BC, there was thought to be over 5,000 tombs, although the most recent estimate suggests ...

. In the central area, the city itself has a population of around 125,000 people. Syracuse is mentioned in the Bible in the Acts of the Apostles

The Acts of the Apostles (, ''Práxeis Apostólōn''; ) is the fifth book of the New Testament; it tells of the founding of the Christian Church and the spread of The gospel, its message to the Roman Empire.

Acts and the Gospel of Luke make u ...

book at 28:12 as Paul

Paul may refer to:

People

* Paul (given name), a given name, including a list of people

* Paul (surname), a list of people

* Paul the Apostle, an apostle who wrote many of the books of the New Testament

* Ray Hildebrand, half of the singing duo ...

stayed there. The patron saint

A patron saint, patroness saint, patron hallow or heavenly protector is a saint who in Catholicism, Anglicanism, Eastern Orthodoxy or Oriental Orthodoxy is regarded as the heavenly advocate of a nation, place, craft, activity, class, clan, fa ...

of the city is Saint Lucy

Lucia of Syracuse ( – 304 AD), also called Saint Lucia () and better known as Saint Lucy, was a Roman people, Roman Christian martyr who died during the Diocletianic Persecution. She is venerated as a saint in Catholic Church, Catholic, Angl ...

; she was born in Syracuse and her feast day, Saint Lucy's Day

Saint Lucy's Day, also called the Feast of Saint Lucy, is a Christian feast day observed on 13 December. The observance commemorates Lucia of Syracuse, an early-fourth-century virgin martyr under the Diocletianic Persecution. According to l ...

, is celebrated on 13 December.

History

Archaic period

Syracuse and its surrounding area have been inhabited since ancient times, as shown by the findings in the villages of Stentinello, Ognina, Plemmirio, Matrensa, Cozzo Pantano and ''Thapsos'', which already had a relationship with

Syracuse and its surrounding area have been inhabited since ancient times, as shown by the findings in the villages of Stentinello, Ognina, Plemmirio, Matrensa, Cozzo Pantano and ''Thapsos'', which already had a relationship with Mycenaean Greece

Mycenaean Greece (or the Mycenaean civilization) was the last phase of the Bronze Age in ancient Greece, spanning the period from approximately 1750 to 1050 BC.. It represents the first advanced and distinctively Greek civilization in mainla ...

.

Syracuse was founded in 734 or 733 BC in Sicily by Greek settlers from Corinth

Corinth ( ; , ) is a municipality in Corinthia in Greece. The successor to the ancient Corinth, ancient city of Corinth, it is a former municipality in Corinthia, Peloponnese (region), Peloponnese, which is located in south-central Greece. Sin ...

and Tenea

Tenea () is a municipal unit within the municipality of Corinth (municipality), Corinth, Corinthia, Peloponnese (region), Peloponnese, Greece. The municipal unit has an area of . Until 2011, its municipal seat was in Chiliomodi.

The modern city ...

, led by the ''oecist

The ''oikistes'' (), often anglicized as oekist or oecist, was the individual chosen by an ancient Greek polis

Polis (: poleis) means 'city' in Ancient Greek. The ancient word ''polis'' had socio-political connotations not possessed by modern u ...

'' (colonizer) Archias. There are many attested variants of the name of the city including ''Syrakousai'', ''Syrakosai'' and ''Syrakō''. One observation cited for the origin of the name is that the Phoenicians

Phoenicians were an ancient Semitic group of people who lived in the Phoenician city-states along a coastal strip in the Levant region of the eastern Mediterranean, primarily modern Lebanon and the Syrian coast. They developed a maritime civi ...

called it Sour-ha-Koussim, which means "Stone of the seagulls" from which would come the name of Syracuse. However, this etymology does not account for the name variant ''Syrakō''. Another possible origin of the city's name was given by Vibius Sequester

Vibius Sequester (active in the 4th or 5th century AD) is the Latin author of lists of geographical names.

Work

''De fluminibus, fontibus, lacubus, nemoribus, gentibus, quorum apud poëtas mentio fit'' is made up of seven alphabetical lists of ...

citing first Stephanus Byzantius

Stephanus or Stephen of Byzantium (; , ''Stéphanos Byzántios''; centuryAD) was a Byzantine grammarian and the author of an important geographical dictionary entitled ''Ethnica'' (). Only meagre fragments of the dictionary survive, but the epit ...

''Ethnika'' 592.18–21,593.1–8, i.e. Stephanus Byzantinus

Stephanus or Stephen of Byzantium (; , ''Stéphanos Byzántios''; centuryAD) was a Byzantine grammarian and the author of an important geographical dictionary entitled ''Ethnica'' (). Only meagre fragments of the dictionary survive, but the epitom ...

' ''Ethnika'' (kat'epitomen), lemma in that there was a Syracusian marsh () called ''Syrako'' and secondly Marcian

Marcian (; ; ; 392 – 27 January 457) was Roman emperor of the Byzantine Empire, East from 450 to 457. Very little is known of his life before becoming emperor, other than that he was a (personal assistant) who served under the commanders ...

's ''Periegesis'' wherein Archias gave the city the name of a nearby marsh; hence one gets ''Syrako'' (and thereby ''Syrakousai'' and other variants) for the name of Syracuse, a name also attested by Epicharmus

Epicharmus of Kos or Epicharmus Comicus or Epicharmus Comicus Syracusanus (), thought to have lived between c. 550 and c. 460 BC, was a Greek dramatist and philosopher who is often credited with being one of the first comedic writers, ...

. The settlement of Syracuse was a planned event, as a strong central leader, Arkhias the aristocrat, laid out how property would be divided up for the settlers, as well as plans for how the streets of the settlement should be arranged, and how wide they should be. The nucleus of the ancient city was the small island of Ortygia

Ortygia ( ; ; ) is a small island which is the historical centre of the city of Syracuse, Sicily. The island, also known as the (Old City), contains many historical landmarks.

The name originates from the Ancient Greek (), which means " quail ...

. The settlers found the land fertile and the native tribes to be reasonably well-disposed to their presence. The city grew and prospered, and for some time stood as the most powerful Greek city anywhere in the Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea ( ) is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the east by the Levant in West Asia, on the north by Anatolia in West Asia and Southern ...

. Colonies were founded at Akrai

Akrai (; ) was a Greek colony of Magna Graecia founded in Sicily by the Syracusans in 663 BC. It was located near the modern Palazzolo Acreide.

Location

It was founded on a spectacular and strategic site, on the Acremonte plateau of the Hy ...

(664 BC), Kasmenai

Casmenae or Kasmenai (, Casmene in Italian) was an ancient Greek colony of Magna Graecia located on the Hyblaean Mountains, founded in 644 BC by the Syracusans at a strategic position for the control of central Sicily. It was also intended ...

(643 BC), Akrillai

Akrillai () and Akrilla (), Acrillae (in Latin) was an ancient Greek colony of Magna Graecia located in the modern province of Ragusa, Sicily, Italy, where the town of Chiaramonte Gulfi stands today. The ruins of the old colony can be found in t ...

(7th century BC), Helorus (7th century BC) and Kamarina (598 BC).

Classical period

The descendants of the first colonists, called ''Gamoroi'', held power until they were expelled by the lower class of the city assisted by Cyllyrians, identified as enslaved natives similar in status to the

The descendants of the first colonists, called ''Gamoroi'', held power until they were expelled by the lower class of the city assisted by Cyllyrians, identified as enslaved natives similar in status to the helots

The helots (; , ''heílotes'') were a subjugated population that constituted a majority of the population of Laconia and Messenia – the territories ruled by Sparta. There has been controversy since antiquity as to their exact characteristic ...

of Sparta. The former, however, returned to power in 485 BC, thanks to the help of Gelo

Gelon also known as Gelo (Greek: Γέλων ''Gelon'', ''gen.'': Γέλωνος; died 478 BC), son of Deinomenes, was a Greek tyrant of the Sicilian cities Gela and Syracuse, Sicily, and first of the Deinomenid rulers.

Early life

Gelon was t ...

, ruler of Gela

Gela (Sicilian and ; ) is a city and (municipality) in the regional autonomy, Autonomous Region of Sicily, Italy; in terms of area and population, it is the largest municipality on the southern coast of Sicily. Gela is part of the Province o ...

. Gelo himself became the despot of the city, and moved many inhabitants of Gela, Kamarina and Megara

Megara (; , ) is a historic town and a municipality in West Attica, Greece. It lies in the northern section of the Isthmus of Corinth opposite the island of Salamis Island, Salamis, which belonged to Megara in archaic times, before being taken ...

to Syracuse, building the new quarters of Tyche and Neapolis outside the walls. His program of new constructions included a new theatre, designed by Damocopos, which gave the city a flourishing cultural life: this in turn attracted personalities as Aeschylus

Aeschylus (, ; ; /524 – /455 BC) was an ancient Greece, ancient Greek Greek tragedy, tragedian often described as the father of tragedy. Academic knowledge of the genre begins with his work, and understanding of earlier Greek tragedy is large ...

, Ario of Methymna

Mithymna () (, also sometimes spelled ''Methymna'') is a town and former municipality on the island of Lesbos, North Aegean, Greece. Since the 2019 local government reform it is part of the municipality of West Lesbos, of which it is a municip ...

and Eumelos of Corinth. The enlarged power of Syracuse made unavoidable the clash against the Carthaginians

The Punic people, usually known as the Carthaginians (and sometimes as Western Phoenicians), were a Semitic people, Semitic people who Phoenician settlement of North Africa, migrated from Phoenicia to the Western Mediterranean during the Iron ...

, who ruled western Sicily. In the Battle of Himera, Gelo, who had allied with Theron of Agrigento

Agrigento (; or ) is a city on the southern coast of Sicily, Italy and capital of the province of Agrigento.

Founded around 582 BC by Greek colonists from Gela, Agrigento, then known as Akragas, was one of the leading cities during the golden ...

, decisively defeated the African force led by Hamilcar __NOTOC__

Hamilcar (, ,. or , , "Melqart is Gracious"; , ''Hamílkas'';) was a common Carthaginian masculine given name. The name was particularly common among the ruling families of ancient Carthage.

People named Hamilcar include:

* Hamilcar th ...

. A temple dedicated to Athena

Athena or Athene, often given the epithet Pallas, is an ancient Greek religion, ancient Greek goddess associated with wisdom, warfare, and handicraft who was later syncretism, syncretized with the Roman goddess Minerva. Athena was regarde ...

(on the site of today's Cathedral), was erected in the city to commemorate the event.

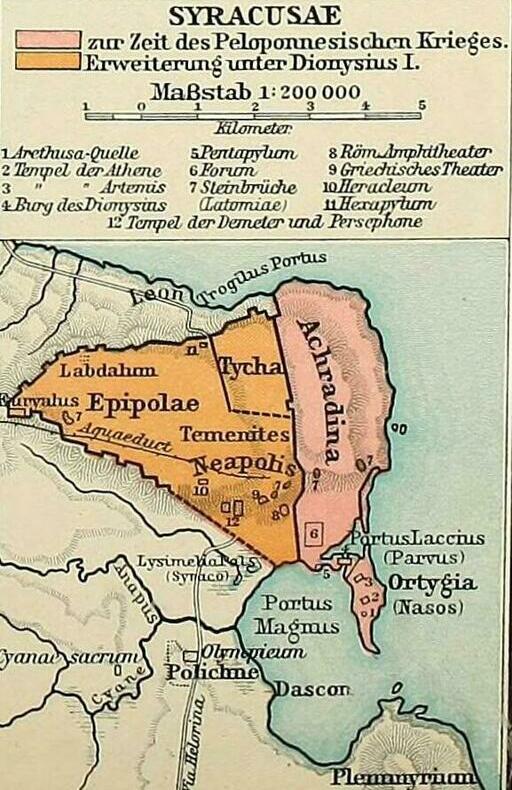

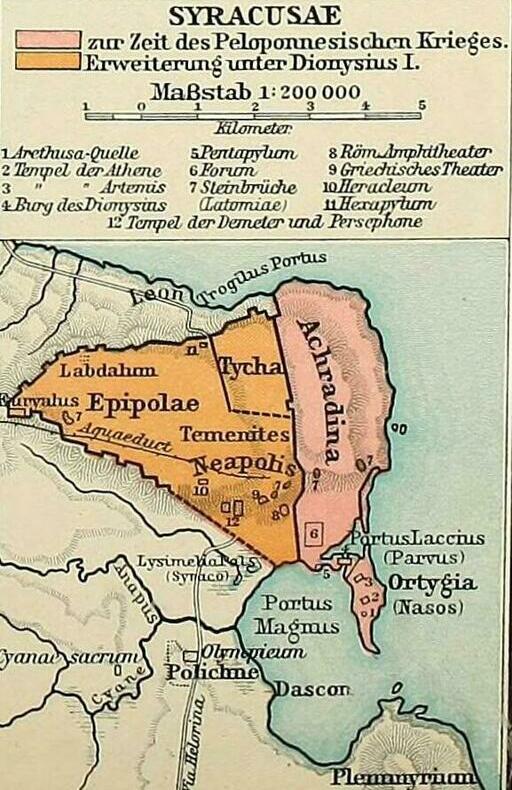

Syracuse grew considerably during this time. Its walls encircled in the fifth century, but as early as the 470s BC the inhabitants started building outside the walls. The complete population of its territory approximately numbered 250,000 in 415 BC and the population size of the city itself was probably similar to Athens.

Gelo was succeeded by his brother Hiero

Hiero or hieron (; , "holy place" or "sacred place") is an ancient Greek shrine, Ancient Greek temple, temple, or temenos, temple precinct.

Hiero may also refer to:

People

* Hiero I of Syracuse, tyrant of Syracuse, Sicily from 478 to 467 BC

* ...

, who fought against the Etruscans

The Etruscan civilization ( ) was an ancient civilization created by the Etruscans, a people who inhabited Etruria in List of ancient peoples of Italy, ancient Italy, with a common language and culture, and formed a federation of city-states. Af ...

at Cumae

Cumae ( or or ; ) was the first ancient Greek colony of Magna Graecia on the mainland of Italy and was founded by settlers from Euboea in the 8th century BCE. It became a rich Roman city, the remains of which lie near the modern village of ...

in 474 BC. His rule was eulogized by poets like Simonides of Ceos

Simonides of Ceos (; ; c. 556 – 468 BC) was a Greek lyric poet, born in Ioulis on Ceos. The scholars of Hellenistic Alexandria included him in the canonical list of the nine lyric poets esteemed by them as worthy of critical study. ...

, Bacchylides

Bacchylides (; ''Bakkhulides''; – ) was a Greek lyric poet. Later Greeks included him in the canonical list of Nine Lyric Poets, which included his uncle Simonides. The elegance and polished style of his lyrics have been noted in Bacchylidea ...

and Pindar

Pindar (; ; ; ) was an Greek lyric, Ancient Greek lyric poet from Thebes, Greece, Thebes. Of the Western canon, canonical nine lyric poets of ancient Greece, his work is the best preserved. Quintilian wrote, "Of the nine lyric poets, Pindar i ...

, who visited his court. A democratic regime was introduced by Thrasybulos (467 BC). The city continued to expand in Sicily

Sicily (Italian language, Italian and ), officially the Sicilian Region (), is an island in the central Mediterranean Sea, south of the Italian Peninsula in continental Europe and is one of the 20 regions of Italy, regions of Italy. With 4. ...

, fighting

Combat ( French for ''fight'') is a purposeful violent conflict between multiple combatants with the intent to harm the opposition. Combat may be armed (using weapons) or unarmed ( not using weapons). Combat is resorted to either as a method of ...

against the rebellious Siculi

The Sicels ( ; or ''Siculī'') were an Indo-European tribe who inhabited eastern Sicily, their namesake, during the Iron Age. They spoke the Siculian language. After the defeat of the Sicels at the Battle of Nomae in 450 BC and the death of ...

, and on the Tyrrhenian Sea

The Tyrrhenian Sea (, ; or ) , , , , is part of the Mediterranean Sea off the western coast of Italy. It is named for the Tyrrhenians, Tyrrhenian people identified with the Etruscans of Italy.

Geography

The sea is bounded by the islands of C ...

, making expeditions up to Corsica

Corsica ( , , ; ; ) is an island in the Mediterranean Sea and one of the Regions of France, 18 regions of France. It is the List of islands in the Mediterranean#By area, fourth-largest island in the Mediterranean and lies southeast of the Metro ...

and Elba

Elba (, ; ) is a Mediterranean Sea, Mediterranean island in Tuscany, Italy, from the coastal town of Piombino on the Italian mainland, and the largest island of the Tuscan Archipelago. It is also part of the Arcipelago Toscano National Park, a ...

. In the late 5th century BC, Syracuse found itself at war with Athens

Athens ( ) is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Greece, largest city of Greece. A significant coastal urban area in the Mediterranean, Athens is also the capital of the Attica (region), Attica region and is the southe ...

, which sought more resources to fight the Peloponnesian War

The Second Peloponnesian War (431–404 BC), often called simply the Peloponnesian War (), was an Ancient Greece, ancient Greek war fought between Classical Athens, Athens and Sparta and their respective allies for the hegemony of the Ancien ...

. The Syracusans enlisted the aid of a general from Sparta

Sparta was a prominent city-state in Laconia in ancient Greece. In antiquity, the city-state was known as Lacedaemon (), while the name Sparta referred to its main settlement in the Evrotas Valley, valley of Evrotas (river), Evrotas rive ...

, Athens' foe in the war, to defeat the Athenians, destroy their ships, and leave them to starve on the island (see Sicilian Expedition

The Sicilian Expedition was an Classical Athens, Athenian military expedition to Sicily, which took place from 415–413 BC during the Peloponnesian War between Classical Athens, Athens on one side and Sparta, Syracuse, Sicily, Syracuse and Co ...

). In 401 BC, Syracuse contributed a force of 300 hoplites

Hoplites ( ) ( ) were citizen-soldiers of Ancient Greek city-states who were primarily armed with spears and shields. Hoplite soldiers used the phalanx formation to be effective in war with fewer soldiers. The formation discouraged the soldi ...

and a general to Cyrus the Younger

Cyrus the Younger ( ''Kūruš''; ; died 401 BC) was an Achaemenid prince and general. He ruled as satrap of Lydia and Ionia from 408 to 401 BC. Son of Darius II and Parysatis, he died in 401 BC in battle during a failed attempt to oust his ...

's Army of the Ten Thousand

The Ten Thousand (, ''hoi Myrioi'') were a force of mercenary units, mainly Greeks, employed by Cyrus the Younger to attempt to wrest the throne of the Persian Empire from his brother, Artaxerxes II. Their march to the Battle of Cunaxa and back ...

.

Then in the early 4th century BC, the tyrant

A tyrant (), in the modern English usage of the word, is an absolute ruler who is unrestrained by law, or one who has usurped a legitimate ruler's sovereignty. Often portrayed as cruel, tyrants may defend their positions by resorting to ...

Dionysius the Elder

Dionysius I or Dionysius the Elder ( 432 – 367 BC) was a Greek tyrant of Syracuse, Sicily. He conquered several cities in Sicily and southern Italy, opposed Carthage's influence in Sicily and made Syracuse the most powerful of the Western ...

was again at war against Carthage

Carthage was an ancient city in Northern Africa, on the eastern side of the Lake of Tunis in what is now Tunisia. Carthage was one of the most important trading hubs of the Ancient Mediterranean and one of the most affluent cities of the classic ...

and, although losing Gela and Camarina, kept that power from capturing the whole of Sicily. After the end of the conflict Dionysius built a massive fortress on Ortygia and 22 km-long walls around all of Syracuse. Another period of expansion saw the destruction of Naxos

Naxos (; , ) is a Greek island belonging to the Cyclades island group. It is the largest island in the group. It was an important centre during the Bronze Age Cycladic Culture and in the Ancient Greek Archaic Period. The island is famous as ...

, Catania

Catania (, , , Sicilian and ) is the second-largest municipality on Sicily, after Palermo, both by area and by population. Despite being the second city of the island, Catania is the center of the most densely populated Sicilian conurbation, wh ...

and Lentini

Lentini (; ; ; ) is a town and in the Province of Syracuse, southeastern Sicily (Southern Italy), located 35 km (22 miles) north-west of Syracuse.

History

The city was founded by colonists from Naxos as Leontini in 729 BC, which in its beginning ...

; then Syracuse entered again in war against Carthage (397 BC). After various changes of fortune, the Carthaginians managed to besiege Syracuse itself, but were eventually pushed back by a pestilence. A treaty in 392 BC allowed Syracuse to enlarge further its possessions, founding the cities of Adrano

Adrano (; Adernò until 1929; ), ancient '' Adranon'', is a town and in the Metropolitan City of Catania on the east coast of Sicily.

It is situated around northwest of Catania, which was also the capital of the province to which Adrano belo ...

n, Tyndarion and Tauromenos, and conquering Rhegion

Reggio di Calabria (; ), commonly and officially referred to as Reggio Calabria, or simply Reggio by its inhabitants, is the largest city in Calabria as well as the seat of the Metropolitan City of Reggio Calabria. As of 2025, it has 168,572 ...

on the continent. In the Adriatic

The Adriatic Sea () is a body of water separating the Italian Peninsula from the Balkans, Balkan Peninsula. The Adriatic is the northernmost arm of the Mediterranean Sea, extending from the Strait of Otranto (where it connects to the Ionian Se ...

, to facilitate trade, Dionysius the Elder

Dionysius I or Dionysius the Elder ( 432 – 367 BC) was a Greek tyrant of Syracuse, Sicily. He conquered several cities in Sicily and southern Italy, opposed Carthage's influence in Sicily and made Syracuse the most powerful of the Western ...

founded Ancona

Ancona (, also ; ) is a city and a seaport in the Marche region of central Italy, with a population of around 101,997 . Ancona is the capital of the province of Ancona, homonymous province and of the region. The city is located northeast of Ro ...

, Adria

Adria is a town and ''comune'' in the province of Rovigo in the Veneto region of northern Italy, situated between the mouths of the rivers Adige and Po River, Po. The remains of the Etruria, Etruscan city of Atria or Hatria are to be found below ...

and Issa. Apart from his battle deeds, Dionysius was famous as a patron of art, and Plato

Plato ( ; Greek language, Greek: , ; born BC, died 348/347 BC) was an ancient Greek philosopher of the Classical Greece, Classical period who is considered a foundational thinker in Western philosophy and an innovator of the writte ...

himself visited Syracuse several times, where Dionysius, offended by Plato's daring to disagree with the king, imprisoned the philosopher and sold him into slavery (according to some sources).

His successor was Dionysius the Younger

Dionysius the Younger (, 343 BC), or Dionysius II, was a Greek politician who ruled Syracuse, Sicily from 367 BC to 357 BC and again from 346 BC to 344 BC.

Biography

Dionysius II of Syracuse was the son of Dionysius the Elder and Doris of Locr ...

, who was however expelled by Dion in 356 BC. But the latter's despotic rule led in turn to his expulsion, and Dionysius reclaimed his throne in 347 BC. Dionysius was besieged in Syracuse by the Syracusan general Hicetas

Hicetas ( or ; c. 400 – c. 335 BC) was a Greek philosopher of the Pythagorean School. He was born in Syracuse, Magna Graecia. Like his fellow Pythagorean Ecphantus and the Academic Heraclides Ponticus, he believed that the daily movement o ...

in 344 BC. The following year the Corinthian Timoleon

Timoleon ( Greek: Τιμολέων), son of Timodemus, of Corinth (–337 BC) was a Greek statesman and general.

As a brilliant general, a champion of Greece against Carthage, and a fighter against despotism, he is closely connected with the h ...

installed a democratic regime in the city after he exiled Dionysius and defeated Hicetas. The long series of internal struggles had weakened Syracuse's power on the island, and Timoleon tried to remedy this, defeating the Carthaginians in the Battle of the Crimissus

The Battle of the Crimissus (also spelled ''Crimisus'' and ''Crimesus'') was fought in 339 BC between a large Carthaginian army commanded by Asdrubal and Hamilcar and an army from Syracuse led by Timoleon. Timoleon attacked the Carthag ...

(339 BC).

Hellenistic period

After Timoleon's death the struggle among the city's parties restarted and ended with the rise of another tyrant,

After Timoleon's death the struggle among the city's parties restarted and ended with the rise of another tyrant, Agathocles

Agathocles ( Greek: ) is a Greek name. The most famous person called Agathocles was Agathocles of Syracuse, the tyrant of Syracuse. The name is derived from and .

Other people named Agathocles include:

*Agathocles, a sophist, teacher of Damon

...

, who seized power with a coup in 317 BC. He resumed the war against Carthage, with alternate fortunes. He was besieged in Syracuse by the Carthaginians in 311 BC, but he escaped from the city with a small fleet. He scored a moral success, bringing the war to the Carthaginians' native African soil, inflicting heavy losses to the enemy. The defenders of Syracuse destroyed the Carthaginian army which besieged them. However, Agathocles was eventually defeated in Africa as well. The war ended with another treaty of peace which did not prevent the Carthaginians from interfering in the politics of Syracuse after the death of Agathocles (289 BC). They laid siege to Syracuse for the fourth and last time in 278 BC. They retreated at the arrival of king Pyrrhus of Epirus

Pyrrhus ( ; ; 319/318–272 BC) was a Greeks, Greek king and wikt:statesman, statesman of the Hellenistic period.Plutarch. ''Parallel Lives'',Pyrrhus... He was king of the Molossians, of the royal Aeacidae, Aeacid house, and later he became ki ...

, whom Syracuse had asked for help. After a brief period under the rule of Epirus, Hiero II

Hiero II (; also Hieron ; ; c. 308 BC – 215 BC) was the Greek tyrant of Syracuse, Greek Sicily, from 275 to 215 BC, and the illegitimate son of a Syracusan noble, Hierocles, who claimed descent from Gelon. He was a former general of Pyrrhus o ...

seized power in 275 BC.

Hiero inaugurated a period of 50 years of peace and prosperity, in which Syracuse became one of the most renowned capitals of Antiquity. He issued the so-called ''Lex Hieronica

The ''Lex Hieronica'' was a unique system of regulations concerning the agricultural taxation of Sicilia (Roman province), Sicily by the Roman Republic. The taxation system was named after King Hiero II of Syracuse, Hiero II of Syracuse, Sicily, Sy ...

'', which was later adopted by the Romans for their administration of Sicily; he also had the theatre enlarged and a new immense altar

An altar is a table or platform for the presentation of religion, religious offerings, for sacrifices, or for other ritualistic purposes. Altars are found at shrines, temples, Church (building), churches, and other places of worship. They are use ...

, the "Hiero's Ara", built. Under his rule lived the most famous Syracusan, the mathematician and natural philosopher

Natural philosophy or philosophy of nature (from Latin ''philosophia naturalis'') is the philosophical study of physics, that is, nature and the physical universe, while ignoring any supernatural influence. It was dominant before the developme ...

Archimedes

Archimedes of Syracuse ( ; ) was an Ancient Greece, Ancient Greek Greek mathematics, mathematician, physicist, engineer, astronomer, and Invention, inventor from the ancient city of Syracuse, Sicily, Syracuse in History of Greek and Hellenis ...

. Among his many inventions were various military engines including the claw of Archimedes

The Claw of Archimedes (; also known as the iron hand) was an ancient weapon devised by Archimedes to defend the seaward portion of Syracuse's city wall against amphibious assault. Although its exact nature is unclear, the accounts of ancient h ...

, later used to resist the Roman siege of 214–212 BC. Literary figures included Theocritus

Theocritus (; , ''Theokritos''; ; born 300 BC, died after 260 BC) was a Greek poet from Sicily, Magna Graecia, and the creator of Ancient Greek pastoral poetry.

Life

Little is known of Theocritus beyond what can be inferred from his writings ...

and others.

Hiero's successor, the young Hieronymus

Hieronymus, in English pronounced or , is the Latin form of the Ancient Greek name (Hierṓnymos), meaning "with a sacred name". It corresponds to the English given name Jerome (given name), Jerome.

Variants

* Albanian language, Albanian: Jeroni ...

(ruled from 215 BC), broke the alliance with the Romans after their defeat at the Battle of Cannae

The Battle of Cannae (; ) was a key engagement of the Second Punic War between the Roman Republic and Ancient Carthage, Carthage, fought on 2 August 216 BC near the ancient village of Cannae in Apulia, southeast Italy. The Carthaginians and ...

and accepted Carthage

Carthage was an ancient city in Northern Africa, on the eastern side of the Lake of Tunis in what is now Tunisia. Carthage was one of the most important trading hubs of the Ancient Mediterranean and one of the most affluent cities of the classic ...

's support. The Romans, led by consul Marcus Claudius Marcellus

Marcus Claudius Marcellus (; 270 – 208 BC) was a Roman general and politician during the 3rd century BC. Five times elected as Roman consul, consul of the Roman Republic (222, 215, 214, 210, and 208 BC). Marcellus gained the most prestigious a ...

, besieged the city in 214 BC. The city held out for three years, but fell in 212 BC. The successes of the Syracusians in repelling the Roman siege had made them overconfident. In 212 BC, the Romans received information that the city's inhabitants were to participate in the annual festival to their goddess Artemis

In ancient Greek religion and Greek mythology, mythology, Artemis (; ) is the goddess of the hunting, hunt, the wilderness, wild animals, transitions, nature, vegetation, childbirth, Kourotrophos, care of children, and chastity. In later tim ...

. A small party of Roman soldiers approached the city under the cover of night and managed to scale the walls to get into the outer city and with reinforcements soon took control, killing Archimedes in the process, but the main fortress remained firm. After an eight-month siege and with parleys in progress, an Iberian

Iberian refers to Iberia. Most commonly Iberian refers to:

*Someone or something originating in the Iberian Peninsula, namely from Spain, Portugal, Gibraltar and Andorra.

The term ''Iberian'' is also used to refer to anything pertaining to the fo ...

captain named Moeriscus is believed to have let the Romans in near the Fountains of Arethusa. On the agreed signal, during a diversionary attack, he opened the gate. After setting guards on the houses of the pro-Roman faction, Marcellus gave Syracuse to plunder.

Imperial Roman and Byzantine period

Though declining slowly through the years, Syracuse maintained the status of capital of the Roman government of Sicily and seat of the

Though declining slowly through the years, Syracuse maintained the status of capital of the Roman government of Sicily and seat of the praetor

''Praetor'' ( , ), also ''pretor'', was the title granted by the government of ancient Rome to a man acting in one of two official capacities: (i) the commander of an army, and (ii) as an elected ''magistratus'' (magistrate), assigned to disch ...

. It remained an important port for trade between the Eastern and the Western parts of the Empire. Christianity spread in the city through the efforts of Paul of Tarsus

Paul, also named Saul of Tarsus, commonly known as Paul the Apostle and Saint Paul, was a Apostles in the New Testament, Christian apostle ( AD) who spread the Ministry of Jesus, teachings of Jesus in the Christianity in the 1st century, first ...

and Saint Marziano, the first bishop of the city, who made it one of the main centres of proselytism

Proselytism () is the policy of attempting to convert people's religious or political beliefs. Carrying out attempts to instill beliefs can be called proselytization.

Proselytism is illegal in some countries. Some draw distinctions between Chris ...

in the West. In the age of Christian persecutions massive catacomb

Catacombs are man-made underground passages primarily used for religious purposes, particularly for burial. Any chamber used as a burial place is considered a catacomb, although the word is most commonly associated with the Roman Empire.

Etym ...

s were carved, whose size is second only to those of Rome.

After a period of Vandal

The Vandals were a Germanic people who were first reported in the written records as inhabitants of what is now Poland, during the period of the Roman Empire. Much later, in the fifth century, a group of Vandals led by kings established Vandal ...

rule, 469–477, Syracuse and the island was recovered for Italian rule under Odoacer (476–491) and Theodoric the Great (491–526), and then by Belisarius

BelisariusSometimes called Flavia gens#Later use, Flavius Belisarius. The name became a courtesy title by the late 4th century, see (; ; The exact date of his birth is unknown. March 565) was a military commander of the Byzantine Empire under ...

for the Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also known as the Eastern Roman Empire, was the continuation of the Roman Empire centred on Constantinople during late antiquity and the Middle Ages. Having survived History of the Roman Empire, the events that caused the ...

(31 December 535). From 663 to 668 Syracuse was the seat of the Greek-speaking Emperor Constans II

Constans II (; 7 November 630 – 15 July 668), also called "the Bearded" (), was the Byzantine emperor from 641 to 668. Constans was the last attested emperor to serve as Roman consul, consul, in 642, although the office continued to exist unti ...

, as well as a capital of the Byzantine (Eastern Roman) Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also known as the Eastern Roman Empire, was the continuation of the Roman Empire centred on Constantinople during late antiquity and the Middle Ages. Having survived the events that caused the fall of the Western Roman E ...

and metropolis of the whole Sicilian Church. Constans II was assassinated when his plans to permanently replace the Byzantine capital of Constantinople with Syracuse became suspected.

Emirate of Sicily

The city was besieged by theAghlabids

The Aghlabid dynasty () was an Arab dynasty centered in Ifriqiya (roughly present-day Tunisia) from 800 to 909 that conquered parts of Sicily, Southern Italy, and possibly Sardinia, nominally as vassals of the Abbasid Caliphate. The Aghlabids ...

for almost a year in 827–828, but Byzantine reinforcements prevented its fall. It remained the center of Byzantine resistance to the gradual Muslim conquest of Sicily

The Arab Muslim conquest of Sicily began in June 827 and lasted until 902, when the last major Byzantine stronghold on the island, Taormina, fell. Isolated fortresses remained in Byzantine hands until 965, but the island was henceforth under Ar ...

until it fell to the Aghlabids after another siege on 20/21 May 878. During the two centuries of Muslim

Muslims () are people who adhere to Islam, a Monotheism, monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God ...

rule, the capital of the Emirate of Sicily

The island of SicilyIn Arabic, the island was known as (). was under Islam, Islamic rule from the late ninth to the late eleventh centuries. It became a prosperous and influential commercial power in the Mediterranean Sea, Mediterranean, with ...

was moved from Syracuse to Palermo

Palermo ( ; ; , locally also or ) is a city in southern Italy, the capital (political), capital of both the autonomous area, autonomous region of Sicily and the Metropolitan City of Palermo, the city's surrounding metropolitan province. The ...

. The cathedral was converted into a mosque and the quarter on the Ortygia

Ortygia ( ; ; ) is a small island which is the historical centre of the city of Syracuse, Sicily. The island, also known as the (Old City), contains many historical landmarks.

The name originates from the Ancient Greek (), which means " quail ...

island was gradually rebuilt along Islamic styles. The city, nevertheless, maintained important trade relationships, and housed a relatively flourishing cultural and artistic life: several Arab poets, including Ibn Hamdis, the most important Sicilian Arab poet of the 12th century, flourished in the city.

Norman kingdom of Sicily

In 1038, the Byzantine generalGeorge Maniakes

George Maniakes (; ; died 1043) was a prominent general of the Byzantine Empire during the 11th century. He was the catepan of Italy in 1042. He is known as Gyrgir in Scandinavian sagas. He is popularly said to have been extremely tall and well ...

reconquered the city, sending the relics of St. Lucy to Constantinople

Constantinople (#Names of Constantinople, see other names) was a historical city located on the Bosporus that served as the capital of the Roman Empire, Roman, Byzantine Empire, Byzantine, Latin Empire, Latin, and Ottoman Empire, Ottoman empire ...

. The eponymous castle on the cape of Ortygia bears his name, although it was built under the Hohenstaufen

The Hohenstaufen dynasty (, , ), also known as the Staufer, was a noble family of unclear origin that rose to rule the Duchy of Swabia from 1079, and to royal rule in the Holy Roman Empire during the Middle Ages from 1138 until 1254. The dynast ...

rule. In 1086, the Normans

The Normans (Norman language, Norman: ''Normaunds''; ; ) were a population arising in the medieval Duchy of Normandy from the intermingling between Norsemen, Norse Viking settlers and locals of West Francia. The Norse settlements in West Franc ...

entered Syracuse, one of the last Arab

Arabs (, , ; , , ) are an ethnic group mainly inhabiting the Arab world in West Asia and North Africa. A significant Arab diaspora is present in various parts of the world.

Arabs have been in the Fertile Crescent for thousands of years ...

strongholds, after siege lasting from May to October by Roger I of Sicily

Roger I (; ; ; Norse: ''Rogeirr''; 1031 – 22 June 1101), nicknamed "Roger Bosso" and "Grand Count Roger", was a Norman nobleman who became the first Grand Count of Sicily from 1071 to 1101.

As a member of the House of Hauteville, he parti ...

and his son Jordan of Hauteville Jordan of Hauteville (–1092) was the eldest son and bastard of Roger I of Sicily. A fighter, he took part, from an early age, in the conquests of his father in Sicily.

Jordan is named as son of Count Roger's first marriage in ''Europäische Stamm ...

, who was given the city as count. New quarters were built, and the cathedral was restored, as well as other churches.

High medieval period

In 1194,Emperor Henry VI

Henry VI (German: ''Heinrich VI.''; November 1165 – 28 September 1197), a member of the Hohenstaufen dynasty, was King of Germany (King of the Romans) from 1169 and Holy Roman Emperor from 1191 until his death. From 1194 he was also King of Sic ...

occupied the Sicilian kingdom, including Syracuse. After a short period of Genoese rule (1205–1220) under the notorious admiral and pirate Alamanno da Costa Alamanno da Costa (active 1193–1224, died before 1229) was a Genoese admiral. He became the count of Syracuse in the Kingdom of Sicily, and led naval expeditions throughout the eastern Mediterranean. He was an important figure in Genoa's longstan ...

, which favoured a rise of trades, royal authority was re-asserted in the city by Frederick II. He began the construction of the Castello Maniace, the Bishops' Palace and the Bellomo Palace. Frederick's death brought a period of unrest and feudal anarchy. In the War of the Sicilian Vespers

The War of the Sicilian Vespers, also shortened to the War of the Vespers, was a conflict waged by several medieval European kingdoms over control of Sicily from 1282 to 1302. The war, which started with the revolt of the Sicilian Vespers, was ...

between the Angevin and Aragonese dynasties for control of Sicily, Syracuse sided with the Aragonese and expelled the Angevins in 1298, receiving from the Spanish sovereigns great privileges in reward. The preeminence of baronial families is also shown by the construction of the palaces of Abela

Abela is a surname.

The Abela family, which is a branch of the royal family of Spain, is originally from Catalonia from where some of its members moved to Valence and then to Sicilia and to Malta. Ávila (called Abela by the Romans) is the capita ...

, Chiaramonte

The Chiaramonte are a noble family of Sicily. They became the most powerful and wealthy family in Sicily. In the 13th century the marriage of Manfredi Chiaramonte to Isabella Mosca, united the two Sicilian counties of Modica and Ragusa. Ar ...

, Nava, Montalto.

16th–20th centuries

The city was struck by two ruinous earthquakes in 1542 and1693

Events

January–March

* January 11 – The Mount Etna volcano erupts in Italy, causing a devastating earthquake that kills 60,000 people in Sicily and Malta

Malta, officially the Republic of Malta, is an island country in Sout ...

, and a plague in 1729. The 17th century destruction changed the appearance of Syracuse forever, as well as the entire Val di Noto

Val di Noto () is a historical and geographical area encompassing the south-eastern third of Sicily; it is dominated by the limestone Hyblaean plateau. Historically, it was one of the three valli of Sicily.

History

The oldest recorded settlemen ...

, whose cities were rebuilt along the typical lines of Sicilian Baroque

Sicilian Baroque is the distinctive form of Baroque architecture which evolved on the island of Sicily, off the southern coast of Italy, in the , when it was part of the Spanish Empire. The style is recognisable not only by its typical Baroque c ...

, considered one of the most typical expressions of the architecture of Southern Italy. The spread of cholera

Cholera () is an infection of the small intestine by some Strain (biology), strains of the Bacteria, bacterium ''Vibrio cholerae''. Symptoms may range from none, to mild, to severe. The classic symptom is large amounts of watery diarrhea last ...

in 1837 led to a revolt against the Bourbon Bourbon may refer to:

Food and drink

* Bourbon whiskey, an American whiskey made using a corn-based mash

* Bourbon, a beer produced by Brasseries de Bourbon

* Bourbon biscuit, a chocolate sandwich biscuit

* Bourbon coffee, a type of coffee ma ...

government. The punishment was the move of the province capital seat to Noto

Noto (; ) is a city and in the Province of Syracuse, Sicily, Italy. It is southwest of the city of Syracuse at the foot of the Iblean Mountains. It lends its name to the surrounding area Val di Noto. In 2002 Noto and its church were decl ...

, but the unrest had not been totally choked, as the Siracusani took part in the Sicilian revolution of 1848

The Sicilian revolution of independence of 1848 (; ) which commenced on 12 January 1848 was the first of the numerous Revolutions of 1848 which swept across Europe. It was a popular rebellion against the rule of Ferdinand II of the House of Bourb ...

.

After the Unification of Italy

The unification of Italy ( ), also known as the Risorgimento (; ), was the 19th century Political movement, political and social movement that in 1861 ended in the Proclamation of the Kingdom of Italy, annexation of List of historic states of ...

of 1865, Syracuse regained its status of provincial capital. In the late 19th century, the walls (including Porta Ligny) were demolished and a bridge connecting the mainland to Ortygia island was built. In the following year a railway link was constructed.

Modern history

Allied bombings in 1943 caused heavy destruction duringWorld War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

. ''Operation Husky'', the codename for the Allied invasion of Sicily

The Allied invasion of Sicily, also known as the Battle of Sicily and Operation Husky, was a major campaign of World War II in which the Allies of World War II, Allied forces invaded the island of Sicily in July 1943 and took it from the Axis p ...

, was launched on the night between 9–10 July 1943 with British forces attacking the southeast of the island. The plan was for the British 5th Infantry Division

The 5th Infantry Division was a regular army infantry Division (military), division of the British Army. It was established by Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington for service in the Peninsular War, as part of the Anglo-Portuguese Army, and ...

, part of General

A general officer is an Officer (armed forces), officer of high rank in the army, armies, and in some nations' air force, air and space forces, marines or naval infantry.

In some usages, the term "general officer" refers to a rank above colone ...

Sir Bernard Montgomery's Eighth Army, to capture Syracuse on the first day of the invasion. This part of the operation went completely according to plan, and British forces captured Syracuse on the first night of the operation. The port was then used as a base for the British Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

. To the west of the city is a Commonwealth War Graves cemetery where about 1,000 men are buried. After the end of the war the northern quarters of Syracuse experienced a heavy, often chaotic, expansion, favoured by the quick process of industrialization.

Syracuse today has about 125,000 inhabitants and numerous attractions for the visitor interested in historical sites (such as the Ear of Dionysius

The Ear of Dionysius () is a limestone cave carved out of the Temenites hill in the city of Syracuse, on the island of Sicily in Italy. Its name, given by the painter Michelangelo da Caravaggio, comes from its similarity in shape to the human e ...

). A process of recovering and restoring the historical centre has been ongoing since the 1990s. Nearby places of note include Catania

Catania (, , , Sicilian and ) is the second-largest municipality on Sicily, after Palermo, both by area and by population. Despite being the second city of the island, Catania is the center of the most densely populated Sicilian conurbation, wh ...

, Noto

Noto (; ) is a city and in the Province of Syracuse, Sicily, Italy. It is southwest of the city of Syracuse at the foot of the Iblean Mountains. It lends its name to the surrounding area Val di Noto. In 2002 Noto and its church were decl ...

, Modica

Modica (; ) is a city and municipality (''comune'') in the Province of Ragusa, Sicily, southern Italy. The city is situated in the Hyblaean Mountains. It has 53,413 inhabitants.

Modica has neolithic origins and it represents the historical cap ...

and Ragusa Ragusa may refer to:

Places Croatia

* Ragusa, Dalmatia, the historical name of the city of Dubrovnik

* the Republic of Ragusa (or Republic of Dubrovnik), the maritime city-state of Ragusa

* Ragusa Vecchia, historical Italian name of Cavtat, a t ...

.

Geography

Climate

Syracuse experiences a hot-summerMediterranean climate

A Mediterranean climate ( ), also called a dry summer climate, described by Köppen and Trewartha as ''Cs'', is a temperate climate type that occurs in the lower mid-latitudes (normally 30 to 44 north and south latitude). Such climates typic ...

(Köppen climate classification

The Köppen climate classification divides Earth climates into five main climate groups, with each group being divided based on patterns of seasonal precipitation and temperature. The five main groups are ''A'' (tropical), ''B'' (arid), ''C'' (te ...

: ''Csa'') with mild, wet winters and hot, dry summers. Snow is infrequent; the last measurable snowfall in the city occurred in December 2014. Frosts are very rare, with the last one also happening in December 2014 when the temperature dropped to the all-time record low of 0 °C.

A temperature of was registered in Floridia

Floridia (; ; from Latin "day of Flora" or the adjective ''floridus'' "florid") is a town and ''comune'' in the Province of Syracuse, Sicily (Italy).

Geography

Floridia lies west of Syracuse. Its principal industries are agriculture, livesto ...

, near Syracuse by the Sicilian Agrometeorological Information Service (SAIS) on 11 August 2021, and is recognized by the World Meteorological Organization

The World Meteorological Organization (WMO) is a List of specialized agencies of the United Nations, specialized agency of the United Nations responsible for promoting international cooperation on atmospheric science, climatology, hydrology an ...

as the official record highest temperature in Europe

Europe is a continent located entirely in the Northern Hemisphere and mostly in the Eastern Hemisphere. It is bordered by the Arctic Ocean to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the west, the Mediterranean Sea to the south, and Asia to the east ...

. Guido Guidi, lieutenant colonel of the Italian Meteorological Service, however, had stated the highest temperature registered in the organizations' stations during the heatwave was , at Naval Air Station Sigonella

Naval Air Station (NAS) Sigonella is an Italian Air Force base ('), and a U.S. Navy installation at Italian Air Force Base Sigonella in Lentini, Sicily, Italy. The whole NAS is a tenant of the Italian Air Force, which has the military and the ...

. Guidi underlines that the reported data by SAIS "is produced directly by the stations and is not subject to any control and validation procedure, neither automatic nor manual. It can therefore report errors due to sensor malfunctions as well as maintenance interventions".

Government

Demographics

In 2016, there were 122,051 people residing in Syracuse, located in the province of Syracuse,Sicily

Sicily (Italian language, Italian and ), officially the Sicilian Region (), is an island in the central Mediterranean Sea, south of the Italian Peninsula in continental Europe and is one of the 20 regions of Italy, regions of Italy. With 4. ...

, of whom 48.7% were male and 51.3% were female. Minors (children ages 18 and younger) totalled 18.9 percent of the population compared to pensioners who number 16.9 percent. This compares with the Italian average of 18.1 percent (minors) and 19.9 percent (pensioners). The average age of Syracuse resident is 40 compared to the Italian average of 42. In the five years between 2002 and 2007, the population of Syracuse declined by 0.5 percent, while Italy as a whole grew by 3.6 percent. The reason for decline is a population flight to the suburbs, and northern Italy

Northern Italy (, , ) is a geographical and cultural region in the northern part of Italy. The Italian National Institute of Statistics defines the region as encompassing the four Northwest Italy, northwestern Regions of Italy, regions of Piedmo ...

. The current birth rate of Syracuse is 9.75 births per 1,000 inhabitants compared to the Italian average of 9.45 births.

, 97.9% of the population was of Italian descent. The largest immigrant group came from other European nations (particularly those from Poland, and the United Kingdom): 0.6%, North Africa (mostly Tunisian): 0.5%, and South Asia: 0.4%.

Tourism

Since 2005, the entire city of Syracuse, along with theNecropolis of Pantalica

The Necropolis of Pantalica is a collection of cemeteries with rock-cut chamber tombs in southeast Sicily, Italy. Dating from the 13th to the 7th centuries BC, there was thought to be over 5,000 tombs, although the most recent estimate suggests ...

which falls within the province of Syracuse

The province of Syracuse (; ) was a Provinces of Italy, province in the autonomous island region of Sicily, Italy. Its capital was the city of Syracuse, Sicily, Syracuse, a town established by Greeks, Greek colonists arriving from Corinth in the ...

, has been listed as a World Heritage Site

World Heritage Sites are landmarks and areas with legal protection under an treaty, international treaty administered by UNESCO for having cultural, historical, or scientific significance. The sites are judged to contain "cultural and natural ...

by UNESCO

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO ) is a List of specialized agencies of the United Nations, specialized agency of the United Nations (UN) with the aim of promoting world peace and International secur ...

. This programme aims to catalogue, name, and conserve sites of outstanding cultural or natural

Nature is an inherent character or constitution, particularly of the ecosphere or the universe as a whole. In this general sense nature refers to the laws, elements and phenomena of the physical world, including life. Although humans are part ...

importance to the common heritage of humanity

Humanity most commonly refers to:

* Human, also humankind

* Humanity (virtue)

Humanity may also refer to:

Literature

* ''Humanity: A Moral History of the Twentieth Century'', a 1999 book by Jonathan Glover

* ''Humanity'', a 1990 science fiction n ...

. The deciding committee which evaluates potential candidates described their reasons for choosing Syracuse because "monuments and archeological sites situated in Syracuse are the finest example of outstanding architectural creation spanning several cultural aspects; Greek

Greek may refer to:

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor of all kno ...

, Roman

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of Roman civilization

*Epistle to the Romans, shortened to Romans, a letter w ...

and Baroque

The Baroque ( , , ) is a Western Style (visual arts), style of Baroque architecture, architecture, Baroque music, music, Baroque dance, dance, Baroque painting, painting, Baroque sculpture, sculpture, poetry, and other arts that flourished from ...

", following on that Ancient Syracuse was "directly linked to events, ideas and literary works of outstanding universal significance".

Buildings of the Greek and Roman periods

* The city walls * The ''Temple of Apollo Temple of Apollo may refer to:

*

Cyprus

*Temple of Apollo Hylates, Limassol

Czech Republic

*Temple of Apollo, Lednice–Valtice Cultural Landscape, South Moravian Region

Greece

*Temple of Apollo, Corinth

*Temple of Apollo (Delphi)

*Temple of A ...

'', at Piazza Emanuele Pancali, adapted to a church in Byzantine times and to a mosque under Arab rule.

* The ''Fountain of Arethusa

The Fountain of Arethusa (, ) is a natural spring on the island of Ortygia in the historical centre of the city of Syracuse in Sicily. According to Greek mythology, this freshwater fountain is the place where the nymph Arethusa, the patron figure ...

'', on Ortygia island. According to a legend, the nymph

A nymph (; ; sometimes spelled nymphe) is a minor female nature deity in ancient Greek folklore. Distinct from other Greek goddesses, nymphs are generally regarded as personifications of nature; they are typically tied to a specific place, land ...

Arethusa, hunted by Alpheus, was turned into a spring by Artemis

In ancient Greek religion and Greek mythology, mythology, Artemis (; ) is the goddess of the hunting, hunt, the wilderness, wild animals, transitions, nature, vegetation, childbirth, Kourotrophos, care of children, and chastity. In later tim ...

and appeared here.

* The ''Greek Theatre

A theatrical culture flourished in ancient Greece from 700 BC. At its centre was the city-state of Athens, which became a significant cultural, political, and religious place during this period, and the theatre was institutionalised there as par ...

'', whose cavea

The ''cavea'' (Latin language, Latin for "enclosure") are the seating sections of Theatre of ancient Greece, Greek and Roman theatre (structure), Roman theatres and Roman amphitheatre, amphitheatres. In Roman theatres, the ''cavea'' is tradition ...

is one of the largest ever built by the ancient Greeks: it has 67 rows, divided into nine sections with eight aisles. Only traces of the scene and the orchestra remain. The edifice (still used today) was modified by the Romans, who adapted it to their different style of spectacles, including also circus games. Near the theatre are the ''latomìe'', stone quarries, also used as prisons in ancient times. The most famous ''latomìa'' is the '' Orecchio di Dionisio'' ("Ear of Dionysius").

* The Roman amphitheatre

Roman amphitheatres are theatres — large, circular or oval open-air venues with tiered seating — built by the ancient Romans. They were used for events such as gladiator combats, ''venationes'' (animal slayings) and executions. About List of R ...

. It was partly carved out from the rock. In the centre of the area is a rectangular space which was used for the scenic machinery.

* The ''Tomb of Archimede'', in the Grotticelli Necropolis. Decorated with two Doric columns.

* The ''Temple of Olympian Zeus

Zeus (, ) is the chief deity of the List of Greek deities, Greek pantheon. He is a sky father, sky and thunder god in ancient Greek religion and Greek mythology, mythology, who rules as king of the gods on Mount Olympus.

Zeus is the child ...

'', about outside the city, built around the 6th century BC.

Buildings of the Christian period

*

* Cathedral of Syracuse

The Cathedral of Syracuse (''Duomo di Siracusa''), formally the (Metropolitan Cathedral of the Most Holy Nativity of Mary), is an ancient Catholic church in Syracuse, Sicily, the seat of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Siracusa, Catholic Archd ...

(): built by bishop Zosimo in the 7th-century over the great '' Temple of Athena'' (5th century BC), on Ortygia island. This was a Doric edifice with six columns on the short sides and 14 on the long sides: these are still incorporated into the walls of the cathedral. The base of the temple had three steps. The interior of the church has a nave and two aisles. The roof of the nave is from Norman times, as well as the mosaics in the apses. The façade was rebuilt by Andrea Palma in 1725–1753, with a double order of Corinthian column

The Corinthian order (, ''Korinthiakós rythmós''; ) is the last developed and most ornate of the three principal classical orders of Ancient Greek architecture and Roman architecture. The other two are the Doric order, which was the earliest, ...

s, and statues by Ignazio Marabitti

Ignazio Marabitti (6 September 1719La Sicilia nel secolo XVIII e la poesia satiricoburlesca

By Giuseppe Leanti, page 163. in Palermo – 1797 in Palermo) was a Sicilian sculptor of the late Baroque period.

He trained in Rome in the studio of Fil ...

. The interior houses a 12th–13th-century marble font, a silver statue of ''St Lucy'' by Pietro Rizzo (1599), a ciborium by Luigi Vanvitelli

Luigi Vanvitelli (; 12 May 1700 – 1 March 1773), known in Dutch as (), was an Italian architect and painter. The most prominent 18th-century architect of Italy, he practised a sober classicising academic Late Baroque style that made an ea ...

, and a statue of the ''Madonna della Neve'' ("Madonna of the Snow", 1512) by Antonello Gagini

Antonello Gagini (1478–1536) was an Italian sculptor of the Renaissance, mainly active in Sicily and Calabria.

Antonello belonged to a family of sculptors and artisans, originally from Northern Italy, but active throughout Italy, including Gen ...

.

* Basilica of ''Santa Lucia Extra moenia

Extra moenia (also: extra muros) is a Latin phrase that means ''outside the walls'' or ''outside the walls of the city''.

The phrase is commonly used in reference to the original attributes of a building, usually a church, which was built outside ...

'': a Byzantine church built (and rebuilt by the Normans), according to tradition, near the same place of the martyrdom of the saint in 303 AD. The current appearance is from the 15th–16th centuries. The most ancient parts still preserved include the portal, the three half-circular apses and the first two orders of the belfry. Under the church are the ''Catacombs of St. Lucy''. For this church Caravaggio

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio (also Michele Angelo Merigi or Amerighi da Caravaggio; 29 September 1571 – 18 July 1610), known mononymously as Caravaggio, was an Italian painter active in Rome for most of his artistic life. During the fina ...

painted the Burial of St. Lucy. In the same complex is a small octagonal shrine which includes the tomb of Saint Lucy

Lucia of Syracuse ( – 304 AD), also called Saint Lucia () and better known as Saint Lucy, was a Roman people, Roman Christian martyr who died during the Diocletianic Persecution. She is venerated as a saint in Catholic Church, Catholic, Angl ...

and Gregorio Tedeschi’s 1735 statue Dying Lucy.

* '' Madonna delle Lacrime'': (Shrine of the Virgin of Tears) 20th century Catholic basilica.

* ''San Benedetto'': 16th century church, restored after 1693. It houses a painting depicting ''Death of Saint Benedict'' by the Caravaggisti

The Caravaggisti (or the "Caravagesques"; singular: "Caravaggista") were stylistic followers of the late 16th-century Italian Baroque painter Caravaggio. His influence on the new Baroque style that eventually emerged from Mannerism was profound. ...

Mario Minniti

Mario Minniti (8 December 1577 – 22 November 1640) was an Italian Baroque painter active in Sicily after 1606.

Born in Syracuse, Sicily, he arrived in Rome in 1593, where he became the friend, collaborator, and model of the key Baroque paint ...

.

* Chiesa della Concezione (14th century, rebuilt in the 18th century), with the annexed Benedictine convent.

* ''San Cristoforo'': 14th century church, rebuilt in 18th-century.

* ''San Giovanni Battista'': 14th century church.

* ''San Filippo Apostolo'': 18th-century church with stairs down to a Jewish ritual bath (Mikvah

A mikveh or mikvah (, ''mikva'ot'', ''mikvot'', or ( Ashkenazic) ''mikves'', lit., "a collection") is a bath used for ritual immersion in Judaism to achieve ritual purity.

In Orthodox Judaism, these regulations are steadfastly adhered t ...

) dating to prior to the expulsion of Jews in 1492

* '' San Filippo Neri: 17th-century façade and interior reconstructed in 18th-century

* '' San Francesco all'Immacolata'': church with a convex façade intermingled by columns and pilaster strips. It housed an ancient celebration, the Svelata ("Revelation"), in which an image of the Madonna was unveiled at dawn of 29 November.

* ''San Giovanni Evangelista'': basilica church built by the Normans and destroyed in 1693. Only partially restored, it was erected over an ancient crypt of the martyr San Marciano, later destroyed by the Arabs. The main altar is Byzantine. It includes the ''Catacombs of San Giovanni'', featuring a maze of tunnels and passages, with thousands of tombs and several frescoes.

* '' San Giuseppe'': 18th-century octagonal church, in disrepair

* '' Santa Lucia alla Badia'': Baroque sanctuary church built after the 1693 earthquake.

* '' Santa Maria dei Miracoli'': 14th century church.

* '' San Martino'': 6th-century church, 14th-century façade, 18th-century interiors

* '' San Paolo Apostolo'': 18th century church.

* '' Spirito Santo'': 18th-century church.

* Church of the Jesuit College, a majestic, Baroque building.

Other notable buildings

* Castello Maniace, constructed between 1232 and 1240, is an example of the military architecture of Frederick II's reign. It is a square structure with circular towers at each of the four corners. The most striking feature is the pointed portal, decorated with polychrome marbles.

* ''Archaeological Museum'' with collections including findings from the mid-Bronze Age to 5th century BC.

* ''Palazzo Lanza Buccheri'' (16th century).

* '' Palazzo Bellomo'' (12th century), which contains an art museum that houses

* Castello Maniace, constructed between 1232 and 1240, is an example of the military architecture of Frederick II's reign. It is a square structure with circular towers at each of the four corners. The most striking feature is the pointed portal, decorated with polychrome marbles.

* ''Archaeological Museum'' with collections including findings from the mid-Bronze Age to 5th century BC.

* ''Palazzo Lanza Buccheri'' (16th century).

* '' Palazzo Bellomo'' (12th century), which contains an art museum that houses Antonello da Messina

Antonello da Messina (; 1425–1430February 1479), properly Antonello di Giovanni di Antonio, but also called Antonello degli Antoni and Anglicized as Anthony of Messina, was an Italian painter from Messina, active during the Italian Early Ren ...

's ''Annunciation

The Annunciation (; ; also referred to as the Annunciation to the Blessed Virgin Mary, the Annunciation of Our Lady, or the Annunciation of the Lord; ) is, according to the Gospel of Luke, the announcement made by the archangel Gabriel to Ma ...

'' (1474).

* ''Palazzo Montalto

Palazzo Montalto, also known as Palazzo Mergulese-Montalto, is a late 14th-century palace on the island of Ortygia in Syracuse, Sicily.

History

The palace was built in 1397 for Maciotta Mergulese. This is commemorated by the following inscription ...

'' (14th century), which conserves the old façade from the 14th century, with a pointed portal.

* ''Archbishop's Palace'' (17th century, modified in the following century). It houses the ''Alagonian Library'', founded in the late 18th century.

* ''Palazzo Vermexio

The Palazzo Vermexio, also known as the Palazzo del Senato, is a 17th-century Baroque monumental building located on the island of Ortigia

Ortygia ( ; ; ) is a small island which is the historical centre of the city of Syracuse, Sicily. The isl ...

'': current Town Hall, includes fragments of an Ionic temple of the 5th century BC.

* ''Palazzo Francica Nava'', with parts of the original 16th century building surviving.