Anthroposophy is a

spiritualnew religious movement

A new religious movement (NRM), also known as a new religion, is a religious or Spirituality, spiritual group that has modern origins and is peripheral to its society's dominant religious culture. NRMs can be novel in origin, or they can be part ...

[Sources for 'new religious movement':] which was founded in the early 20th century by the

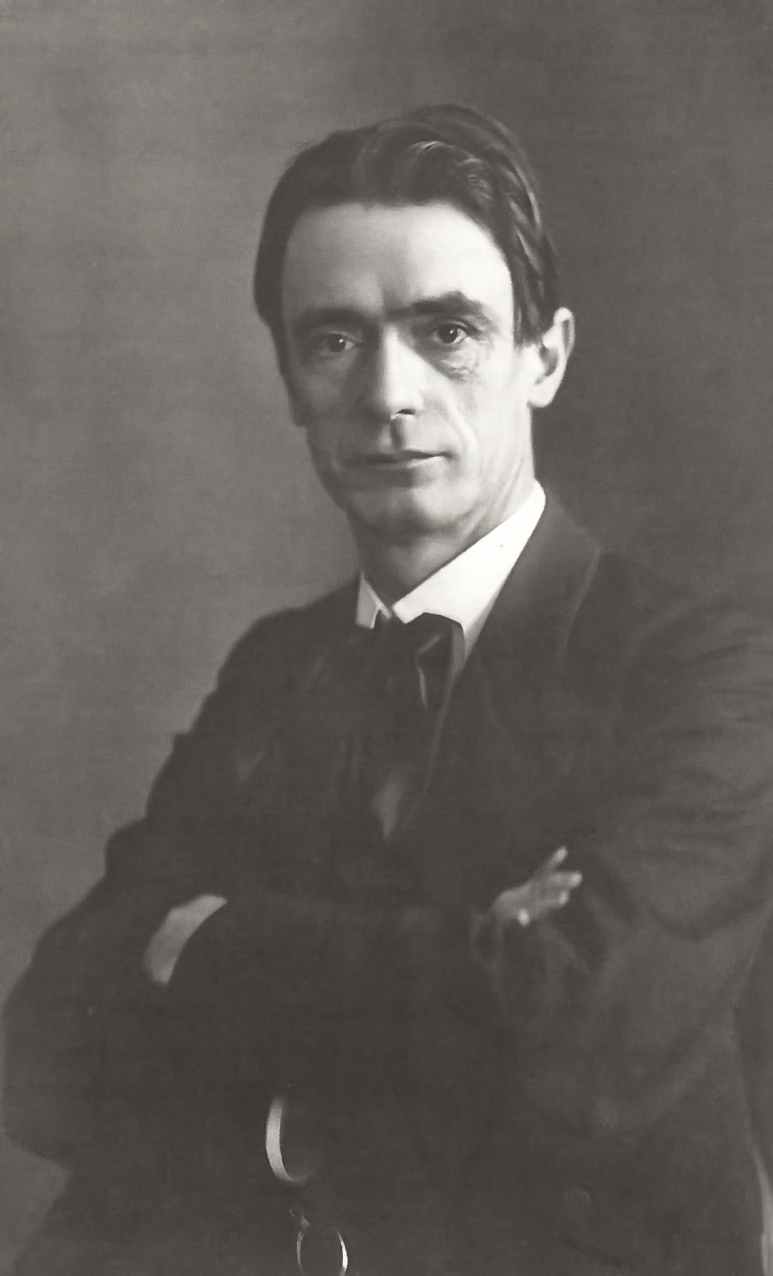

esotericist Rudolf Steiner

Rudolf Joseph Lorenz Steiner (; 27 or 25 February 1861 – 30 March 1925) was an Austrian occultist, social reformer, architect, esotericist, and claimed clairvoyant. Steiner gained initial recognition at the end of the nineteenth century ...

that postulates the existence of an

objective, intellectually comprehensible

spiritual world, accessible to human experience. Followers of anthroposophy aim to engage in spiritual discovery through a mode of thought independent of sensory experience.

Though proponents claim to present their ideas in a manner that is verifiable by rational discourse and say that they seek precision and clarity comparable to that obtained by

scientists

A scientist is a person who researches to advance knowledge in an area of the natural sciences.

In classical antiquity, there was no real ancient analog of a modern scientist. Instead, philosophers engaged in the philosophical study of nature ...

investigating the physical world, many of these ideas have been termed

pseudoscientific

Pseudoscience consists of statements, beliefs, or practices that claim to be both scientific and factual but are incompatible with the scientific method. Pseudoscience is often characterized by contradictory, exaggerated or unfalsifiable cl ...

by experts in

epistemology

Epistemology is the branch of philosophy that examines the nature, origin, and limits of knowledge. Also called "the theory of knowledge", it explores different types of knowledge, such as propositional knowledge about facts, practical knowle ...

and debunkers of pseudoscience.

[Sources for 'pseudoscience':]

Anthroposophy has its roots in

German idealism

German idealism is a philosophical movement that emerged in Germany in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. It developed out of the work of Immanuel Kant in the 1780s and 1790s, and was closely linked both with Romanticism and the revolutionary ...

, Western and Eastern esoteric ideas, various religious traditions, and modern

Theosophy

Theosophy is a religious movement established in the United States in the late 19th century. Founded primarily by the Russian Helena Blavatsky and based largely on her writings, it draws heavily from both older European philosophies such as Neop ...

. Steiner chose the term ''anthroposophy'' (from Greek ἄνθρωπος , 'human', and ''σοφία

sophia'', 'wisdom') to emphasize his philosophy's

humanist

Humanism is a philosophical stance that emphasizes the individual and social potential, and agency of human beings, whom it considers the starting point for serious moral and philosophical inquiry.

The meaning of the term "humanism" ha ...

ic orientation.

He defined it as "a scientific exploration of the spiritual world"; others have variously called it a "philosophy and cultural movement", a "spiritual movement", a "spiritual science", "a system of thought", "a speculative and oracular metaphysic",

"system

..replete with esoteric and occult mystifications",

or "a spiritualist movement",

or ''folie a culte''.

Anthroposophical ideas have been applied in a range of fields including education (both in

Waldorf schools

Waldorf education, also known as Steiner education, is based on the educational philosophy of Rudolf Steiner, the founder of anthroposophy. Its educational style is Holistic education, holistic, intended to develop pupils' intellectual, artistic ...

and in the

Camphill movement

The Camphill Movement is an initiative for social change based on the principles of anthroposophy. Camphill communities are residential communities and schools that provide support for the education, employment, and daily lives of adults and child ...

), environmental conservation and

banking

A bank is a financial institution that accepts Deposit account, deposits from the public and creates a demand deposit while simultaneously making loans. Lending activities can be directly performed by the bank or indirectly through capital m ...

; with additional applications in

agriculture

Agriculture encompasses crop and livestock production, aquaculture, and forestry for food and non-food products. Agriculture was a key factor in the rise of sedentary human civilization, whereby farming of domesticated species created ...

,

organizational development

Organization development (OD) is the study and implementation of practices, systems, and techniques that affect organizational change. The goal of which is to modify a group's/organization's performance and/or culture. The organizational chan ...

, the

arts

The arts or creative arts are a vast range of human practices involving creativity, creative expression, storytelling, and cultural participation. The arts encompass diverse and plural modes of thought, deeds, and existence in an extensive ...

, and more.

The

Anthroposophical Society is headquartered at the

Goetheanum

The Goetheanum, located in Dornach, in the canton of Solothurn, Switzerland, is the world center for the Anthroposophy, anthroposophical movement. The term refers to two structures, the first was in use 1919 to 1922 and destroyed by fire; the sec ...

in

Dornach, Switzerland. Anthroposophy's supporters include writers

Saul Bellow

Saul Bellow (born Solomon Bellows; June 10, 1915April 5, 2005) was a Canadian-American writer. For his literary work, Bellow was awarded the Pulitzer Prize, the 1976 Nobel Prize in Literature, and the National Medal of Arts. He is the only write ...

,

and

Selma Lagerlöf

Selma Ottilia Lovisa Lagerlöf (, , ; 20 November 1858 – 16 March 1940) was a Swedish writer. She published her first novel, ''Gösta Berling's Saga'', at the age of 33. She was the first woman to win the Nobel Prize in Literature, which she was ...

,

painters

Piet Mondrian

Pieter Cornelis Mondriaan (; 7 March 1872 – 1 February 1944), known after 1911 as Piet Mondrian (, , ), was a Dutch Painting, painter and Theory of art, art theoretician who is regarded as one of the greatest artists of the 20th century. He w ...

,

Wassily Kandinsky

Wassily Wassilyevich Kandinsky ( – 13 December 1944) was a Russian painter and art theorist. Kandinsky is generally credited as one of the pioneers of abstract art, abstraction in western art. Born in Moscow, he spent his childhood in ...

and

Hilma af Klint,

filmmaker

Andrei Tarkovsky

Andrei Arsenyevich Tarkovsky (, ; 4 April 1932 – 29 December 1986) was a Soviet film director and screenwriter of Russian origin. He is widely considered one of the greatest directors in cinema history. Works by Andrei Tarkovsky, His films e ...

,

child psychiatrist

Eva Frommer,

music therapist

Maria Schüppel,

Romuva religious founder

Vydūnas

Wilhelm Storost, artistic name Vilius Storostas-Vydūnas (22 March 1868 – 20 February 1953), mostly known as Vydūnas, was a Prussian-Lithuanian teacher, poet, humanist, philosopher and Lithuanian

writer, a leader of the Prussian Lithuani ...

,

[Bagdonavičius, Vaclovas.]

Similarities and Differences between Vydūnas and Steiner

("Berührungspunkte und Unterschiede zwischen Vydūnas und Steiner"). n Lithuanian Vydūnas und deutsche Kultur, sudarytojai Vacys Bagdonavičius, Aušra Martišiūtė-Linartienė, Vilnius: Lietuvių literatūros ir tautosakos institutas, 2013, pp. 325–330. and former president of Georgia

Zviad Gamsakhurdia.

While critics and proponents alike acknowledge Steiner's many anti-racist statements,

"Steiner's collected works...contain pervasive internal contradictions and inconsistencies on racial and national questions."

[

The historian of religion ]Olav Hammer

Olav Hammer (born 1958) is a Swedish professor emeritus at the University of Southern Denmark in Odense working in the field of history of religion.

Career

Hammer has written four books in Swedish and one monograph, ''Claiming Knowledge: Strat ...

has termed anthroposophy "the most important esoteric society in European history".[ See also p. 98, where Hammer states that – unusually for founders of esoteric movements – Steiner's self-descriptions of the origins of his thought and work correspond to the view of external historians.] Many scientists, physicians, and philosophers, including Michael Shermer

Michael Brant Shermer (born September 8, 1954) is an American science writer, historian of science, executive director of The Skeptics Society, and founding publisher of '' Skeptic'' magazine, a publication focused on investigating pseudoscientif ...

, Michael Ruse

Michael Escott Ruse (21 June 1940 – 1 November 2024) was a British-born Canadian philosopher of science who specialised in the philosophy of biology and worked on the relationship between science and religion, the creation–evolution contr ...

, Edzard Ernst

Edzard Ernst (born 30 January 1948) is a retired British-German academic physician and researcher specializing in the study of complementary and alternative medicine. He was Professor of Complementary Medicine at the University of Exeter, the wo ...

, David Gorski

David Henry Gorski is an American surgical oncologist and professor of surgery at Wayne State University School of Medicine. He specializes in breast cancer surgery at the Karmanos Cancer Institute. Gorski is an outspoken skeptic and critic ...

, and Simon Singh have criticized anthroposophy's application in the areas of medicine, biology, agriculture, and education, considering it dangerous and pseudoscientific

Pseudoscience consists of statements, beliefs, or practices that claim to be both scientific and factual but are incompatible with the scientific method. Pseudoscience is often characterized by contradictory, exaggerated or unfalsifiable cl ...

.[Sources for 'dangerous' or 'pseudoscientific':] Ideas of Steiner's that are unsupported or disproven by modern science include: racial evolution, clairvoyance ( Steiner claimed he was clairvoyant),Atlantis

Atlantis () is a fictional island mentioned in Plato's works '' Timaeus'' and ''Critias'' as part of an allegory on the hubris of nations. In the story, Atlantis is described as a naval empire that ruled all Western parts of the known world ...

myth.

History

The early work of the founder of anthroposophy,

The early work of the founder of anthroposophy, Rudolf Steiner

Rudolf Joseph Lorenz Steiner (; 27 or 25 February 1861 – 30 March 1925) was an Austrian occultist, social reformer, architect, esotericist, and claimed clairvoyant. Steiner gained initial recognition at the end of the nineteenth century ...

, culminated in his '' Philosophy of Freedom'' (also translated as ''The Philosophy of Spiritual Activity'' and ''Intuitive Thinking as a Spiritual Path''). Here, Steiner developed a concept of free will

Free will is generally understood as the capacity or ability of people to (a) choice, choose between different possible courses of Action (philosophy), action, (b) exercise control over their actions in a way that is necessary for moral respon ...

based on inner experiences, especially those that occur in the creative activity of independent thought.Theosophical Society

The Theosophical Society is the organizational body of Theosophy, an esoteric new religious movement. It was founded in New York City, U.S.A. in 1875. Among its founders were Helena Blavatsky, a Russian mystic and the principal thinker of the ...

. From 1900 on, thanks to the positive reception his ideas received from Theosophists, Steiner focused increasingly on his work with the Theosophical Society, becoming the secretary

A secretary, administrative assistant, executive assistant, personal secretary, or other similar titles is an individual whose work consists of supporting management, including executives, using a variety of project management, program evalu ...

of its section in Germany in 1902. During his leadership, membership increased dramatically, from just a few individuals to sixty-nine lodges.[Of these, 55 lodges – about 2,500 people – seceded with Steiner to form his new Anthroposophical Society at the end of 1912. Geoffrey Ahern, ]

Sun at Midnight: the Rudolf Steiner Movement and Gnosis in the West, 2nd edition

'', 2009, James Clark and Co, , p. 43

By 1907, a split between Steiner and the Theosophical Society became apparent. While the Society was oriented toward an Eastern and especially India

India, officially the Republic of India, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area; the List of countries by population (United Nations), most populous country since ...

n approach, Steiner was trying to develop a path that embraced Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion, which states that Jesus in Christianity, Jesus is the Son of God (Christianity), Son of God and Resurrection of Jesus, rose from the dead after his Crucifixion of Jesus, crucifixion, whose ...

and natural science

Natural science or empirical science is one of the branches of science concerned with the description, understanding and prediction of natural phenomena, based on empirical evidence from observation and experimentation. Mechanisms such as peer ...

.[Gary Lachman, ''Rudolf Steiner'', New York:Tarcher/Penguin ] The split became irrevocable when Annie Besant

Annie Besant (; Wood; 1 October 1847 – 20 September 1933) was an English socialist, Theosophy (Blavatskian), theosophist, freemason, women's rights and Home Rule activist, educationist and campaigner for Indian nationalism. She was an arden ...

, then president of the Theosophical Society, presented the child Jiddu Krishnamurti

Jiddu Krishnamurti ( ; 11 May 1895 – 17 February 1986) was an Indian Philosophy, philosopher, speaker, writer, and Spirituality, spiritual figure. Adopted by members of the Theosophy, Theosophical tradition as a child, he was raised to fill ...

as the reincarnated Christ. Steiner strongly objected and considered any comparison between Krishnamurti and Christ to be nonsense; many years later, Krishnamurti also repudiated the assertion. Steiner's continuing differences with Besant led him to separate from the Theosophical Society Adyar. He was subsequently followed by the great majority of the Theosophical Society's German members, as well as many members of other national sections. In 1912, Steiner broke away from the ''Theosophical Society'' to found an independent group, which he named the ''Anthroposophical Society.'' After

In 1912, Steiner broke away from the ''Theosophical Society'' to found an independent group, which he named the ''Anthroposophical Society.'' After World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, members of the young society began applying Steiner's ideas to create cultural movements in areas such as traditional

A tradition is a system of beliefs or behaviors (folk custom) passed down within a group of people or society with symbolic meaning or special significance with origins in the past. A component of cultural expressions and folklore, common examp ...

and special education

Special education (also known as special-needs education, aided education, alternative provision, exceptional student education, special ed., SDC, and SPED) is the practice of educating students in a way that accommodates their individual di ...

, farming, and medicine

Medicine is the science and Praxis (process), practice of caring for patients, managing the Medical diagnosis, diagnosis, prognosis, Preventive medicine, prevention, therapy, treatment, Palliative care, palliation of their injury or disease, ...

.

By 1923, a schism had formed between older members, focused on inner development, and younger members eager to become active in contemporary social transformations. In response, Steiner attempted to bridge the gap by establishing an overall School for ''Spiritual Science''. As a spiritual basis for the reborn movement, Steiner wrote a ''Foundation Stone Meditation'' which remains a central touchstone of anthroposophical ideas.

Steiner died just over a year later, in 1925. The Second World War temporarily hindered the anthroposophical movement in most of Continental Europe, as the Anthroposophical Society and most of its practical counter-cultural applications were banned by the Nazi government.Rudolf Hess

Rudolf Walter Richard Hess (Heß in German; 26 April 1894 – 17 August 1987) was a German politician, Nuremberg trials, convicted war criminal and a leading member of the Nazi Party in Nazi Germany, Germany. Appointed Deputy Führer ( ...

, was a strong supporter of anthroposophy,Sicherheitsdienst

' (, "Security Service"), full title ' ("Security Service of the ''Reichsführer-SS''"), or SD, was the intelligence agency of the Schutzstaffel, SS and the Nazi Party in Nazi Germany. Established in 1931, the SD was the first Nazi intelligence ...

argued largely in vain against Anthroposophy. According to Staudenmaier, "The prospect of unmitigated persecution was held at bay for years in a tenuous truce between pro-anthroposophical and anti-anthroposophical Nazi factions."

Morals: Anthroposophy was not the stake of that dispute, but merely powerful Nazis wanting to get rid of other powerful Nazis. E.g. Jehovah's Witnesses

Jehovah's Witnesses is a Christian denomination that is an outgrowth of the Bible Student movement founded by Charles Taze Russell in the nineteenth century. The denomination is nontrinitarian, millenarian, and restorationist. Russell co-fou ...

were treated much more aggressively than Anthroposophists.

Kurlander stated that "the Nazis were hardly ideologically opposed to the supernatural sciences themselves"—rather they objected to the free (i.e. non-totalitarian) pursuit of supernatural sciences.[Staudenmaier (2014: 18, 79). Quote: Though raised Catholic, Büchenbacher had partial Jewish ancestry and was considered a “half-Jew” by Nazi standards. He emigrated to Switzerland in 1936. According to his post-war memoirs, “approximately two thirds of German anthroposophists more or less succumbed to National Socialism.” He reported that various influential anthroposophists were “deeply infected by Nazi views” and “staunchly supported Hitler.” Both Guenther Wachsmuth, Secretary of the Swiss-based General Anthroposophical Society, and Marie Steiner, the widow of Rudolf Steiner, were described as “completely pro-Nazi.” Büchenbacher retrospectively lamented the far-reaching “Nazi sins” of his colleagues.] Marie Steiner-von Sivers, Guenther Wachsmuth, and Albert Steffen, had publicly expressed sympathy for the Nazi regime since its beginnings; led by such sympathies of their leadership, the Swiss and German Anthroposophical organizations chose for a path conflating accommodation with collaboration, which in the end ensured that while the Nazi regime hunted the esoteric organizations, Gentile Anthroposophists from Nazi Germany and countries occupied by it were let be to a surprising extent. Of course they had some setbacks from the enemies of Anthroposophy among the upper echelons of the Nazi regime, but Anthroposophists also had loyal supporters among them, so overall Gentile Anthroposophists were not badly hit by the Nazi regime.

Staudenmaier's overall argument is that "there were often no clear-cut lines between theosophy, anthroposophy, ariosophy, astrology and the ''völkisch'' movement from which the Nazi Party arose."

Etymology and earlier uses of the word

''Anthroposophy'' is an amalgam of the Greek

Greek may refer to:

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor of all kno ...

terms ( 'human') and ( 'wisdom'). An early English usage is recorded by Nathan Bailey

Nathan Bailey (died 27 June 1742), was an English philologist and lexicographer. He was the author of several dictionaries, including his '' Universal Etymological Dictionary'', which appeared in some 30 editions between 1721 and 1802. Bailey' ...

(1742) as meaning "the knowledge of the nature of man".

The first known use of the term ''anthroposophy'' occurs within '' Arbatel de magia veterum, summum sapientiae studium'', a book published anonymously in 1575 and attributed to Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa. The work describes anthroposophy (as well as theosophy) variously as an understanding of goodness, nature, or human affairs. In 1648, the Welsh philosopher Thomas Vaughan published his ''Anthroposophia Theomagica, or a discourse of the nature of man and his state after death.''

The term began to appear with some frequency in philosophical works of the mid- and late-nineteenth century. In the early part of that century, Ignaz Troxler used the term ''anthroposophy'' to refer to philosophy deepened to self-knowledge, which he suggested allows deeper knowledge of nature as well. He spoke of human nature as a mystical unity of God and world. Immanuel Hermann Fichte used the term ''anthroposophy'' to refer to "rigorous human self-knowledge", achievable through thorough comprehension of the human spirit and of the working of God in this spirit, in his 1856 work ''Anthropology: The Study of the Human Soul''. In 1872, the philosopher of religion Gideon Spicker used the term ''anthroposophy'' to refer to self-knowledge that would unite God and world: "the true study of the human being is the human being, and philosophy's highest aim is self-knowledge, or Anthroposophy."

In 1882, the philosopher Robert Zimmermann published the treatise, "An Outline of Anthroposophy: Proposal for a System of Idealism on a Realistic Basis," proposing that idealistic philosophy should employ logical thinking to extend empirical experience. Steiner attended lectures by Zimmermann at the

The first known use of the term ''anthroposophy'' occurs within '' Arbatel de magia veterum, summum sapientiae studium'', a book published anonymously in 1575 and attributed to Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa. The work describes anthroposophy (as well as theosophy) variously as an understanding of goodness, nature, or human affairs. In 1648, the Welsh philosopher Thomas Vaughan published his ''Anthroposophia Theomagica, or a discourse of the nature of man and his state after death.''

The term began to appear with some frequency in philosophical works of the mid- and late-nineteenth century. In the early part of that century, Ignaz Troxler used the term ''anthroposophy'' to refer to philosophy deepened to self-knowledge, which he suggested allows deeper knowledge of nature as well. He spoke of human nature as a mystical unity of God and world. Immanuel Hermann Fichte used the term ''anthroposophy'' to refer to "rigorous human self-knowledge", achievable through thorough comprehension of the human spirit and of the working of God in this spirit, in his 1856 work ''Anthropology: The Study of the Human Soul''. In 1872, the philosopher of religion Gideon Spicker used the term ''anthroposophy'' to refer to self-knowledge that would unite God and world: "the true study of the human being is the human being, and philosophy's highest aim is self-knowledge, or Anthroposophy."

In 1882, the philosopher Robert Zimmermann published the treatise, "An Outline of Anthroposophy: Proposal for a System of Idealism on a Realistic Basis," proposing that idealistic philosophy should employ logical thinking to extend empirical experience. Steiner attended lectures by Zimmermann at the University of Vienna

The University of Vienna (, ) is a public university, public research university in Vienna, Austria. Founded by Rudolf IV, Duke of Austria, Duke Rudolph IV in 1365, it is the oldest university in the German-speaking world and among the largest ...

in the early 1880s, thus at the time of this book's publication.

In the early 1900s, Steiner began using the term ''anthroposophy'' (i.e. human wisdom) as an alternative to the term ''theosophy'' (i.e. divine wisdom).

Central ideas

Spiritual knowledge and freedom

Anthroposophical proponents aim to extend the clarity of the scientific method

The scientific method is an Empirical evidence, empirical method for acquiring knowledge that has been referred to while doing science since at least the 17th century. Historically, it was developed through the centuries from the ancient and ...

to phenomena of human soul-life and spiritual experiences. Steiner believed this required developing new faculties of objective spiritual perception, which he maintained was still possible for contemporary humans. The steps of this process of inner development he identified as consciously achieved ''imagination

Imagination is the production of sensations, feelings and thoughts informing oneself. These experiences can be re-creations of past experiences, such as vivid memories with imagined changes, or completely invented and possibly fantastic scenes ...

'', '' inspiration'', and ''intuition

Intuition is the ability to acquire knowledge without recourse to conscious reasoning or needing an explanation. Different fields use the word "intuition" in very different ways, including but not limited to: direct access to unconscious knowledg ...

''.[, Schneider quotes here from Steiner's dissertation, ''Truth and Knowledge''] For Steiner, the human capacity for rational

Rationality is the quality of being guided by or based on reason. In this regard, a person acts rationally if they have a good reason for what they do, or a belief is rational if it is based on strong evidence. This quality can apply to an ...

thought would allow individuals to comprehend spiritual research on their own and bypass the danger of dependency on an authority such as himself.mysticism

Mysticism is popularly known as becoming one with God or the Absolute (philosophy), Absolute, but may refer to any kind of Religious ecstasy, ecstasy or altered state of consciousness which is given a religious or Spirituality, spiritual meani ...

, which he considered lacking the clarity necessary for exact knowledge, and natural science

Natural science or empirical science is one of the branches of science concerned with the description, understanding and prediction of natural phenomena, based on empirical evidence from observation and experimentation. Mechanisms such as peer ...

, which he considered arbitrarily limited to what can be seen, heard, or felt with the outward senses.

Nature of the human being

In ''Theosophy'', Steiner suggested that human beings unite a ''physical body'' of substances gathered from and returning to the inorganic world; a ''life body'' (also called the etheric body), in common with all living creatures (including plants); a bearer of sentience

Sentience is the ability to experience feelings and sensations. It may not necessarily imply higher cognitive functions such as awareness, reasoning, or complex thought processes. Some writers define sentience exclusively as the capacity for ''v ...

or consciousness

Consciousness, at its simplest, is awareness of a state or object, either internal to oneself or in one's external environment. However, its nature has led to millennia of analyses, explanations, and debate among philosophers, scientists, an ...

(also called the astral body

The astral body is a subtle body posited by many philosophers, intermediate between the intelligent soul and the mental body, composed of a subtle material. In many recensions the concept ultimately derives from the philosophy of Plato though th ...

), in common with all animal

Animals are multicellular, eukaryotic organisms in the Biology, biological Kingdom (biology), kingdom Animalia (). With few exceptions, animals heterotroph, consume organic material, Cellular respiration#Aerobic respiration, breathe oxygen, ...

s; and the ego, which anchors the faculty of self-awareness unique to human beings.

Anthroposophy describes a broad evolution of human consciousness. Early stages of human evolution possess an intuitive perception of reality, including a clairvoyant

Clairvoyance (; ) is the claimed ability to acquire information that would be considered impossible to get through scientifically proven sensations, thus classified as extrasensory perception, or "sixth sense". Any person who is claimed to ...

perception of spiritual realities. Humanity has progressively evolved an increasing reliance on intellect

Intellect is a faculty of the human mind that enables reasoning, abstraction, conceptualization, and judgment. It enables the discernment of truth and falsehood, as well as higher-order thinking beyond immediate perception. Intellect is dis ...

ual faculties and a corresponding loss of intuitive or clairvoyant experiences, which have become atavistic. The increasing intellectualization of consciousness, initially a progressive direction of evolution, has led to an excessive reliance on abstraction

Abstraction is a process where general rules and concepts are derived from the use and classifying of specific examples, literal (reality, real or Abstract and concrete, concrete) signifiers, first principles, or other methods.

"An abstraction" ...

and a loss of contact with both natural and spiritual realities. However, to go further requires new capacities that combine the clarity of intellectual thought with the imagination and with consciously achieved inspiration and intuitive insights.death

Death is the end of life; the irreversible cessation of all biological functions that sustain a living organism. Death eventually and inevitably occurs in all organisms. The remains of a former organism normally begin to decompose sh ...

of the physical body, the human spirit recapitulates the past life, perceiving its events as they were experienced by the objects of its actions. A complex transformation takes place between the review of the past life and the preparation for the next life. The individual's karmic condition eventually leads to a choice of parents, physical body, disposition, and capacities that provide the challenges and opportunities that further development requires, which includes karmically chosen tasks for the future life.[

Steiner described some conditions that determine the interdependence of a person's lives, or ]karma

Karma (, from , ; ) is an ancient Indian concept that refers to an action, work, or deed, and its effect or consequences. In Indian religions, the term more specifically refers to a principle of cause and effect, often descriptively called ...

.

Evolution

The anthroposophical view of evolution

Evolution is the change in the heritable Phenotypic trait, characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. It occurs when evolutionary processes such as natural selection and genetic drift act on genetic variation, re ...

considers all animals

Animals are multicellular, eukaryotic organisms in the biological kingdom Animalia (). With few exceptions, animals consume organic material, breathe oxygen, have myocytes and are able to move, can reproduce sexually, and grow from a ...

to have evolved from an early, unspecialized form. As the least specialized animal, human beings have maintained the closest connection to the archetypal form; contrary to the Darwinian conception of human evolution, all other animals ''devolve'' from this archetype.Theosophy

Theosophy is a religious movement established in the United States in the late 19th century. Founded primarily by the Russian Helena Blavatsky and based largely on her writings, it draws heavily from both older European philosophies such as Neop ...

's complex system of cycles of world development and human evolution. The evolution of the world is said to have occurred in cycles. The first phase of the world consisted only of heat. In the second phase, a more active condition, light, and a more condensed, gaseous state separate out from the heat. In the third phase, a fluid state arose, as well as a sounding, forming energy. In the fourth (current) phase, solid physical matter first exists. This process is said to have been accompanied by an evolution of consciousness which led up to present human culture.

Ethics

The anthroposophical view is that good is found in the balance between two polar influences on world and human evolution. These are often described through their mythological embodiments as spiritual adversaries which endeavour to tempt and corrupt humanity, Lucifer

The most common meaning for Lucifer in English is as a name for the Devil in Christian theology.

He appeared in the King James Version of the Bible in Isaiah and before that in the Vulgate (the late-4th-century Latin translation of the Bib ...

and his counterpart Ahriman

Angra Mainyu (; ) is the Avestan name of Zoroastrianism's hypostasis of the "destructive/evil spirit" and the main adversary in Zoroastrianism either of the Spenta Mainyu, the "holy/creative spirits/mentality", or directly of Ahura Mazda, th ...

. These have both positive and negative aspects. Lucifer is the light spirit, which "plays on human pride and offers the delusion of divinity", but also motivates creativity

Creativity is the ability to form novel and valuable Idea, ideas or works using one's imagination. Products of creativity may be intangible (e.g. an idea, scientific theory, Literature, literary work, musical composition, or joke), or a physica ...

and spirituality

The meaning of ''spirituality'' has developed and expanded over time, and various meanings can be found alongside each other. Traditionally, spirituality referred to a religious process of re-formation which "aims to recover the original shape o ...

; Ahriman is the dark spirit that tempts human beings to "...deny heir

Inheritance is the practice of receiving private property, titles, debts, entitlements, privileges, rights, and obligations upon the death of an individual. The rules of inheritance differ among societies and have changed over time. Offi ...

link with divinity and to live entirely on the material plane", but that also stimulates intellectuality and technology

Technology is the application of Conceptual model, conceptual knowledge to achieve practical goals, especially in a reproducible way. The word ''technology'' can also mean the products resulting from such efforts, including both tangible too ...

. Both figures exert a negative effect on humanity when their influence becomes misplaced or one-sided, yet their influences are necessary for human freedom to unfold.

Claimed applications

Rationale

Steiner/Waldorf education

There is a pedagogical movement with over 1000 Steiner or Waldorf schools (the latter name stems from the first such school, founded in Stuttgart in 1919) located in some 60 countries; the great majority of these are independent (private) schools. Sixteen of the schools have been affiliated with the United Nations' UNESCO Associated Schools Project Network, which sponsors education projects that foster improved quality of education throughout the world. Waldorf schools receive full or partial governmental funding in some European nations, Australia and in parts of the United States (as Waldorf method public or charter schools) and Canada.

The schools have been founded in a variety of communities: for example in the ''favela

Favela () is an umbrella name for several types of impoverished neighborhoods in Brazil. The term, which means slum or ghetto, was first used in the Slum of Providência in the center of Rio de Janeiro in the late 19th century, which was b ...

s'' of São Paulo[White, Ralph]

Interview with Rene M. Querido

''Lapis Magazine'' to wealthy suburbs of major cities;Egypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

, Australia, the Netherlands, Mexico and South Africa. Though most of the early Waldorf schools were teacher-founded, the schools today are usually initiated and later supported by a parent community.[Lenart, Claudia M]

"Steiner's Chicago Legacy Shines Brightly"

, ''Conscious Choice'' June 2003

Benjamin Lazier calls Steiner a "maverick educator".

Biodynamic agriculture

Biodynamic agriculture, is a form of alternative agriculture based on pseudo-scientific and esoteric concepts. It was also the first intentional form of organic farming,[ begun in 1924, when Rudolf Steiner gave a series of lectures published in English as ''The Agriculture Course''.][Paull, John (2011]

. "Attending the First Organic Agriculture Course: Rudolf Steiner's Agriculture Course at Koberwitz, 1924"

, ''European Journal of Social Sciences'', 21(1):64–70. Steiner is considered one of the founders of the modern organic farming

Organic farming, also known as organic agriculture or ecological farming or biological farming,Labelling, article 30 o''Regulation (EU) 2018/848 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 30 May 2024 on organic production and labelling of ...

movement.[Cf. ] "' ..with the active cooperation of the Reich League for Biodynamic Agriculture' ..Pancke, Pohl, and Hans Merkel established additional biodynamic plantations across the eastern territories as well as Dachau, Ravensbrück, and Auschwitz concentration camps. Many were staffed by anthroposophists."

Anthroposophical medicine

Anthroposophical medicine is a form of alternative medicine

Alternative medicine refers to practices that aim to achieve the healing effects of conventional medicine, but that typically lack biological plausibility, testability, repeatability, or supporting evidence of effectiveness. Such practices are ...

based on pseudoscientific

Pseudoscience consists of statements, beliefs, or practices that claim to be both scientific and factual but are incompatible with the scientific method. Pseudoscience is often characterized by contradictory, exaggerated or unfalsifiable cl ...

and occult

The occult () is a category of esoteric or supernatural beliefs and practices which generally fall outside the scope of organized religion and science, encompassing phenomena involving a 'hidden' or 'secret' agency, such as magic and mysti ...

notions rather than in science-based medicine

''Science-Based Medicine'' is a website and blog with articles covering issues in science and medicine, especially medical scams and practices. Founded in 2008, it is owned and operated by the New England Skeptical Society, and run by Steve ...

.[ ''Cited in'' ]

Most anthroposophic medical preparations are highly diluted, like homeopathic remedies, while harmless in of themselves, using them in place of conventional medicine to treat illness is ineffective and risks adverse consequences.

Special needs education and services

In 1922, Ita Wegman

Ita Wegman (22 February 1876 – 4 March 1943) co-founded Anthroposophical Medicine with Rudolf Steiner. In 1921, she founded the first anthroposophical medical clinic in Arlesheim, known until 2014 as the Ita Wegman Clinic. She also developed a s ...

founded an anthroposophical center for special needs education, the Sonnenhof, in Switzerland. In 1940, Karl König

Karl König (25 September 1902 – 27 March 1966) was an Austrian paediatrician who founded the Camphill Movement, an international movement of therapeutic intentional community, intentional communities for those with special needs or disabilitie ...

founded the Camphill Movement

The Camphill Movement is an initiative for social change based on the principles of anthroposophy. Camphill communities are residential communities and schools that provide support for the education, employment, and daily lives of adults and child ...

in Scotland. The latter in particular has spread widely, and there are now over a hundred Camphill communities and other anthroposophical homes for children and adults in need of special care in about 22 countries around the world. Both Karl König, Thomas Weihs and others have written extensively on these ideas underlying Special education.

Architecture

Steiner designed around thirteen buildings in an organic— expressionist architectural style. Foremost among these are his designs for the two Goetheanum buildings in Dornach, Switzerland. Thousands of further buildings have been built by later generations of anthroposophic architects.

Steiner designed around thirteen buildings in an organic— expressionist architectural style. Foremost among these are his designs for the two Goetheanum buildings in Dornach, Switzerland. Thousands of further buildings have been built by later generations of anthroposophic architects.Hans Scharoun

Bernhard Hans Henry Scharoun (; 20 September 1893 – 25 November 1972) was a German architect best known for designing the (home to the Berlin Philharmonic) and the Schminke House in Löbau, Saxony. He was an important exponent of Organic arc ...

and Joachim Eble in Germany, Erik Asmussen in Sweden, Kenji Imai in Japan, Thomas Rau, Anton Alberts and Max van Huut in the Netherlands, Christopher Day and Camphill Architects in the UK, Thompson and Rose in America, Denis Bowman in Canada, and Walter Burley Griffin

Walter Burley Griffin (November 24, 1876February 11, 1937) was an American architect and landscape architect. He designed Canberra, Australia's capital city, the New South Wales towns of Griffith, New South Wales, Griffith and Leeton, New So ...

[Paull, John (2012]

Walter Burley Griffin and Marion Mahony Griffin, Architects of Anthroposophy

, Journal of Bio-Dynamics Tasmania, 106:20–30. and Gregory Burgess in Australia.Amsterdam

Amsterdam ( , ; ; ) is the capital of the Netherlands, capital and Municipalities of the Netherlands, largest city of the Kingdom of the Netherlands. It has a population of 933,680 in June 2024 within the city proper, 1,457,018 in the City Re ...

is a contemporary building by an anthroposophical architect which has received awards for its ecological design and approach to a self-sustaining ecology as an autonomous building

An autonomous building is a hypothetical building designed to be operated independently from infrastructure, infrastructural support services such as the electric power grid, gas grid, municipal water systems, sewage treatment systems, storm dr ...

and example of sustainable architecture

Sustainable architecture is architecture that seeks to minimize the negative environmental impact of buildings through improved efficiency and moderation in the use of materials, energy, development space and the ecosystem at large. Sometimes, su ...

.

Eurythmy

Together with Marie von Sivers, Steiner developed eurythmy, a performance art

Performance art is an artwork or art exhibition created through actions executed by the artist or other participants. It may be witnessed live or through documentation, spontaneously developed or written, and is traditionally presented to a pu ...

combining dance

Dance is an The arts, art form, consisting of sequences of body movements with aesthetic and often Symbol, symbolic value, either improvised or purposefully selected. Dance can be categorized and described by its choreography, by its repertoir ...

, speech, and music.

Social finance and entrepreneurship

Around the world today are a number of banks, companies, charities, and schools for developing co-operative forms of business using Steiner's ideas about economic associations, aiming at harmonious and socially responsible roles in the world economy.Bochum

Bochum (, ; ; ; ) is a city in North Rhine-Westphalia. With a population of 372,348 (April 2023), it is the sixth-largest city (after Cologne, Düsseldorf, Dortmund, Essen and Duisburg) in North Rhine-Westphalia, the most populous German federa ...

, Germany, founded in 1974.

Socially responsible banks founded out of anthroposophy include Triodos Bank, founded in the Netherlands

, Terminology of the Low Countries, informally Holland, is a country in Northwestern Europe, with Caribbean Netherlands, overseas territories in the Caribbean. It is the largest of the four constituent countries of the Kingdom of the Nether ...

in 1980 and also active in the UK, Germany, Belgium

Belgium, officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. Situated in a coastal lowland region known as the Low Countries, it is bordered by the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Luxembourg to the southeas ...

, Spain

Spain, or the Kingdom of Spain, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe with territories in North Africa. Featuring the Punta de Tarifa, southernmost point of continental Europe, it is the largest country in Southern Eur ...

and France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

. Other examples include Cultura Sparebank which dates from 1982 when a group of Norwegian anthroposophists began an initiative for ethical banking but only began to operate as a savings bank in Norway

Norway, officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic countries, Nordic country located on the Scandinavian Peninsula in Northern Europe. The remote Arctic island of Jan Mayen and the archipelago of Svalbard also form part of the Kingdom of ...

in the late 90s, La Nef in France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

and RSF Social Financein San Francisco

San Francisco, officially the City and County of San Francisco, is a commercial, Financial District, San Francisco, financial, and Culture of San Francisco, cultural center of Northern California. With a population of 827,526 residents as of ...

.

Harvard Business School historian Geoffrey Jones traced the considerable impact both Steiner and later anthroposophical entrepreneurs had on the creation of many businesses in organic food, ecological architecture and sustainable finance

Sustainable finance is the set of practices, standards, norms, regulations and products that pursue financial returns alongside environmental and/or social objectives. It is sometimes used interchangeably with Environmental, Social & Governance ( ...

.

Organizational development, counselling and biography work

Bernard Lievegoed, a psychiatrist, founded a new method of individual and institutional development oriented towards humanizing organizations and linked with Steiner's ideas of the threefold social order. This work is represented by the NPI Institute for Organizational Development in the Netherlands and sister organizations in many other countries.

Speech and drama

There are also anthroposophical movements to renew speech and drama, the most important of which are based in the work of Marie Steiner-von Sivers

Marie Steiner-von SiversSome sources cite birthname as

Marie von Sivers, Marie Sievers, or Marie von Sievers (14 March 1867 – 27 December 1948) was a Baltic German actress, the second wife of Rudolf Steiner and one of his closest colleagu ...

(''speech formation'', also known as ''Creative Speech'') and the ''Chekhov Method'' originated by Michael Chekhov

Mikhail Aleksandrovich Chekhov (; 16 August 1891 – 30 September 1955), known as Michael Chekhov, was a Russian-American actor, Theatre director, director, author, and theatre practitioner. He was a nephew of the playwright Anton Chekhov an ...

(nephew of Anton Chekhov

Anton Pavlovich Chekhov (; ; 29 January 1860 – 15 July 1904) was a Russian playwright and short-story writer, widely considered to be one of the greatest writers of all time. His career as a playwright produced four classics, and his b ...

).

Art

Anthroposophic painting, a style inspired by

Anthroposophic painting, a style inspired by Rudolf Steiner

Rudolf Joseph Lorenz Steiner (; 27 or 25 February 1861 – 30 March 1925) was an Austrian occultist, social reformer, architect, esotericist, and claimed clairvoyant. Steiner gained initial recognition at the end of the nineteenth century ...

, featured prominently in the first Goetheanum

The Goetheanum, located in Dornach, in the canton of Solothurn, Switzerland, is the world center for the Anthroposophy, anthroposophical movement. The term refers to two structures, the first was in use 1919 to 1922 and destroyed by fire; the sec ...

's cupola. The technique frequently begins by filling the surface to be painted with color, out of which forms are gradually developed, often images with symbolic-spiritual significance. Paints that allow for many transparent layers are preferred, and often these are derived from plant materials. Rudolf Steiner

Rudolf Joseph Lorenz Steiner (; 27 or 25 February 1861 – 30 March 1925) was an Austrian occultist, social reformer, architect, esotericist, and claimed clairvoyant. Steiner gained initial recognition at the end of the nineteenth century ...

appointed the English sculptor Edith Maryon as head of the School of Fine Art

In European academic traditions, fine art (or, fine arts) is made primarily for aesthetics or creative expression, distinguishing it from popular art, decorative art or applied art, which also either serve some practical function (such as ...

at the Goetheanum

The Goetheanum, located in Dornach, in the canton of Solothurn, Switzerland, is the world center for the Anthroposophy, anthroposophical movement. The term refers to two structures, the first was in use 1919 to 1922 and destroyed by fire; the sec ...

.[Paull, John (2018]

A Portrait of Edith Maryon: Artist and Anthroposophist

, Journal of Fine Arts, 1(2):8–15. Together they carved the 9-metre tall sculpture titled ''The Representative of Humanity'', on display at the Goetheanum

The Goetheanum, located in Dornach, in the canton of Solothurn, Switzerland, is the world center for the Anthroposophy, anthroposophical movement. The term refers to two structures, the first was in use 1919 to 1922 and destroyed by fire; the sec ...

.[

]

Other

*Phenomenological approaches to science, pseudo-scientific

*Phenomenological approaches to science, pseudo-scientificretirement community

A retirement community is a residential community or housing complex designed for older adults who are generally able to care for themselves. Assistance from home care agencies is allowed in some communities, and activities and socialization op ...

and other anthroposophic projects.

*The Harduf ''kibbutz

A kibbutz ( / , ; : kibbutzim / ) is an intentional community in Israel that was traditionally based on agriculture. The first kibbutz, established in 1910, was Degania Alef, Degania. Today, farming has been partly supplanted by other economi ...

'' in Israel.

Social goals

For a period after World War I, Steiner was extremely active and well known in Germany, in part because he lectured widely proposing social reforms. Steiner was a sharp critic of nationalism

Nationalism is an idea or movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the state. As a movement, it presupposes the existence and tends to promote the interests of a particular nation, Smith, Anthony. ''Nationalism: Theory, I ...

, which he saw as outdated, and a proponent of achieving social solidarity through individual freedom.Hermann Hesse

Hermann Karl Hesse (; 2 July 1877 – 9 August 1962) was a Germans, German-Swiss people, Swiss poet and novelist, and the 1946 Nobel Prize in Literature laureate. His interest in Eastern philosophy, Eastern religious, spiritual, and philosophic ...

, among others) was widely circulated. His main book on social reform is ''Toward Social Renewal''.human rights

Human rights are universally recognized Morality, moral principles or Social norm, norms that establish standards of human behavior and are often protected by both Municipal law, national and international laws. These rights are considered ...

and the economy

An economy is an area of the Production (economics), production, Distribution (economics), distribution and trade, as well as Consumption (economics), consumption of Goods (economics), goods and Service (economics), services. In general, it is ...

. It emphasizes a particular ideal in each of these three realms of society:Equality

Equality generally refers to the fact of being equal, of having the same value.

In specific contexts, equality may refer to:

Society

* Egalitarianism, a trend of thought that favors equality for all people

** Political egalitarianism, in which ...

of rights

Rights are law, legal, social, or ethics, ethical principles of freedom or Entitlement (fair division), entitlement; that is, rights are the fundamental normative rules about what is allowed of people or owed to people according to some legal sy ...

, the sphere of legislation

Legislation is the process or result of enrolling, enacting, or promulgating laws by a legislature, parliament, or analogous governing body. Before an item of legislation becomes law it may be known as a bill, and may be broadly referred ...

* Fraternity in the economic sphere

According to Cees Leijenhorst, "Steiner outlined his vision of a new political and social philosophy that avoids the two extremes of capitalism and socialism."Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who, upon assuming office as Prime Minister of Italy, Prime Minister, became the dictator of Fascist Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 un ...

's government

Esoteric path

Paths of spiritual development

According to Steiner, a real spiritual world exists, evolving along with the material one. Steiner held that the spiritual world can be researched in the right circumstances through direct experience, by persons practicing rigorous forms of ethical

Ethics is the philosophical study of moral phenomena. Also called moral philosophy, it investigates normative questions about what people ought to do or which behavior is morally right. Its main branches include normative ethics, applied e ...

and cognitive

Cognition is the "mental action or process of acquiring knowledge and understanding through thought, experience, and the senses". It encompasses all aspects of intellectual functions and processes such as: perception, attention, thought, ...

self-discipline. Steiner described many exercises he said were suited to strengthening such self-discipline; the most complete exposition of these is found in his book ''How To Know Higher Worlds''. The aim of these exercises is to develop higher levels of consciousness

Consciousness, at its simplest, is awareness of a state or object, either internal to oneself or in one's external environment. However, its nature has led to millennia of analyses, explanations, and debate among philosophers, scientists, an ...

through meditation

Meditation is a practice in which an individual uses a technique to train attention and awareness and detach from reflexive, "discursive thinking", achieving a mentally clear and emotionally calm and stable state, while not judging the meditat ...

and observation

Observation in the natural sciences is an act or instance of noticing or perceiving and the acquisition of information from a primary source. In living beings, observation employs the senses. In science, observation can also involve the percep ...

. Details about the spiritual world, Steiner suggested, could on such a basis be discovered and reported, though no more infallibly than the results of natural science.[

]

Prerequisites to and stages of inner development

Steiner's stated prerequisites to beginning on a spiritual path include a willingness to take up serious cognitive studies, a respect for factual evidence, and a responsible attitude. Central to progress on the path itself is a harmonious cultivation of the following qualities:[Stein, W. J., ''Die moderne naturwissenschaftliche Vorstellungsart und die Weltanschauung Goethes, wie sie Rudolf Steiner vertritt'', reprinted in Meyer, Thomas, ''W.J. Stein / Rudolf Steiner'', pp. 267–75; 256–7.]

* By focusing on symbolic patterns, images, and poetic mantras, the meditant can achieve consciously directed Imaginations that allow sensory phenomena to appear as the expression of underlying beings of a soul-spiritual nature.

* By transcending such imaginative pictures, the meditant can become conscious of the meditative activity itself, which leads to experiences of expressions of soul-spiritual beings unmediated by sensory phenomena or qualities. Steiner calls this stage Inspiration.

* By intensifying the will-forces through exercises such as a chronologically reversed review of the day's events, the meditant can achieve a further stage of inner independence from sensory experience, leading to direct contact, and even union, with spiritual beings ("Intuition") without loss of individual awareness.

Spiritual exercises

Steiner described numerous exercises he believed would bring spiritual development; other anthroposophists have added many others. A central principle is that "for every step in spiritual perception, three steps are to be taken in moral development." According to Steiner, moral development reveals the extent to which one has achieved control over one's inner life and can exercise it in harmony with the spiritual life of other people; it shows the real progress in spiritual development, the fruits of which are given in spiritual perception. It also guarantees the capacity to distinguish between false perceptions or illusions (which are possible in perceptions of both the outer world and the inner world) and true perceptions: i.e., the capacity to distinguish in any perception between the influence of subjective elements (i.e., viewpoint) and objective reality.

Place in Western philosophy

Steiner built upon Goethe

Johann Wolfgang (von) Goethe (28 August 1749 – 22 March 1832) was a German polymath who is widely regarded as the most influential writer in the German language. His work has had a wide-ranging influence on Western literature, literary, Polit ...

's conception of an imaginative power capable of synthesizing the sense-perceptible form of a thing (an image of its outer appearance) and the concept we have of that thing (an image of its inner structure or nature). Steiner added to this the conception that a further step in the development of thinking is possible when the thinker observes his or her own thought processes. "The organ of observation and the observed thought process are then identical, so that the condition thus arrived at is simultaneously one of perception through thinking and one of thought through perception."epistemic

Epistemology is the branch of philosophy that examines the nature, origin, and limits of knowledge. Also called "the theory of knowledge", it explores different types of knowledge, such as propositional knowledge about facts, practical knowledg ...

basis for Steiner's later anthroposophical work is contained in the seminal work, Philosophy of Freedom.[ See also Steiner's doctoral thesis, ''Truth and Science''] In his early works, Steiner sought to overcome what he perceived as the dualism of Cartesian idealism and Kant

Immanuel Kant (born Emanuel Kant; 22 April 1724 – 12 February 1804) was a German philosopher and one of the central Enlightenment thinkers. Born in Königsberg, Kant's comprehensive and systematic works in epistemology, metaphysics, et ...

ian subjectivism by developing Goethe's conception of the human being as a natural-supernatural entity, that is: natural in that humanity is a product of nature, supernatural in that through our conceptual powers we extend nature's realm, allowing it to achieve a reflective capacity in us as philosophy, art and science.Western thought

Western philosophy refers to the philosophical thought, traditions and works of the Western world. Historically, the term refers to the philosophical thinking of Western culture, beginning with the ancient Greek philosophy of the pre-Socratics. ...

.Owen Barfield

Arthur Owen Barfield (9 November 1898 – 14 December 1997) was an English philosopher, author, poet, critic, and member of the Inklings.

Life

Barfield was born in London, to Elizabeth (née Shoults; 1860–1940) and Arthur Edward Barfield (186 ...

(and through him influenced the Inklings

The Inklings were an informal literature, literary discussion group associated with J. R. R. Tolkien and C. S. Lewis at the University of Oxford for nearly two decades between the early 1930s and late 1949. The Inklings were literary enthusia ...

, an Oxford

Oxford () is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city and non-metropolitan district in Oxfordshire, England, of which it is the county town.

The city is home to the University of Oxford, the List of oldest universities in continuou ...

group of Christian writers that included J. R. R. Tolkien

John Ronald Reuel Tolkien (, 3 January 1892 – 2 September 1973) was an English writer and philologist. He was the author of the high fantasy works ''The Hobbit'' and ''The Lord of the Rings''.

From 1925 to 1945, Tolkien was the Rawlinson ...

and C. S. Lewis

Clive Staples Lewis (29 November 1898 – 22 November 1963) was a British writer, literary scholar and Anglican lay theologian. He held academic positions in English literature at both Magdalen College, Oxford (1925–1954), and Magdalen ...

).

Union of science and spirit

Steiner believed in the possibility of applying the clarity of scientific thinking to spiritual experience, which he saw as deriving from an objectively existing spiritual world.[Christoph Lindenberg, ''Rudolf Steiner'', Rowohlt 1992, ] Steiner identified mathematics

Mathematics is a field of study that discovers and organizes methods, Mathematical theory, theories and theorems that are developed and Mathematical proof, proved for the needs of empirical sciences and mathematics itself. There are many ar ...

, which attains certainty through thinking itself, thus through inner experience rather than empirical observation, as the basis of his epistemology of spiritual experience.

Anthroposophy regards mainstream science as Ahriman

Angra Mainyu (; ) is the Avestan name of Zoroastrianism's hypostasis of the "destructive/evil spirit" and the main adversary in Zoroastrianism either of the Spenta Mainyu, the "holy/creative spirits/mentality", or directly of Ahura Mazda, th ...

ic.[Sources for 'Ahrimanic':]

Relationship to religion

Esoteric School

The Esoteric School of the Anthroposophical Society originated, directly and indirectly, from "the many pansophical and occult groups belonging to high-grade Masonry", going through the Theosophical Society

The Theosophical Society is the organizational body of Theosophy, an esoteric new religious movement. It was founded in New York City, U.S.A. in 1875. Among its founders were Helena Blavatsky, a Russian mystic and the principal thinker of the ...

and Ordo Templi Orientis

Ordo Templi Orientis (O.T.O.; ) is an occult secret society and hermetic magical organization founded at the beginning of the 20th century. The origins of O.T.O. can be traced back to the German-speaking occultists Carl Kellner, Theodor Reuss, ...

.

Christ as the center of earthly evolution

Steiner's writing, though appreciative of all religions and cultural developments, emphasizes Western tradition as having evolved to meet contemporary needs.

Divergence from conventional Christian thought

Steiner's views of Christianity diverge from conventional Christian thought in key places, and include gnostic

Gnosticism (from Ancient Greek: , romanized: ''gnōstikós'', Koine Greek: �nostiˈkos 'having knowledge') is a collection of religious ideas and systems that coalesced in the late 1st century AD among early Christian sects. These diverse g ...

elements:

* One central point of divergence is Steiner's views on reincarnation

Reincarnation, also known as rebirth or transmigration, is the Philosophy, philosophical or Religion, religious concept that the non-physical essence of a living being begins a new lifespan (disambiguation), lifespan in a different physical ...

and karma.

* Steiner differentiated three contemporary paths by which he believed it possible to arrive at Christ

Jesus ( AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ, Jesus of Nazareth, and many other names and titles, was a 1st-century Jewish preacher and religious leader. He is the Jesus in Christianity, central figure of Christianity, the M ...

:

** Through heart-felt experiences of the Gospels

Gospel originally meant the Christian message (" the gospel"), but in the second century AD the term (, from which the English word originated as a calque) came to be used also for the books in which the message was reported. In this sen ...

; Steiner described this as the historically dominant path, but becoming less important in the future.

** Through inner experiences of a spiritual reality; this Steiner regarded as increasingly the path of spiritual or religious seekers today.

** Through initiatory experiences whereby the reality of Christ's death and resurrection are experienced; Steiner believed this is the path people will increasingly take.Jesus

Jesus (AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ, Jesus of Nazareth, and many Names and titles of Jesus in the New Testament, other names and titles, was a 1st-century Jewish preacher and religious leader. He is the Jesus in Chris ...

children involved in the Incarnation

Incarnation literally means ''embodied in flesh'' or ''taking on flesh''. It is the Conception (biology), conception and the embodiment of a deity or spirit in some earthly form or an Anthropomorphism, anthropomorphic form of a god. It is used t ...

of the Christ: one child descended from Solomon

Solomon (), also called Jedidiah, was the fourth monarch of the Kingdom of Israel (united monarchy), Kingdom of Israel and Judah, according to the Hebrew Bible. The successor of his father David, he is described as having been the penultimate ...

, as described in the Gospel of Matthew

The Gospel of Matthew is the first book of the New Testament of the Bible and one of the three synoptic Gospels. It tells the story of who the author believes is Israel's messiah (Christ (title), Christ), Jesus, resurrection of Jesus, his res ...

, the other child from Nathan

Nathan or Natan may refer to:

People and biblical figures

*Nathan (given name), including a list of people and characters with this name

* Nathan (surname)

*Nathan (prophet), a person in the Hebrew Bible

*Nathan (son of David), a biblical figu ...

, as described in the Gospel of Luke

The Gospel of Luke is the third of the New Testament's four canonical Gospels. It tells of the origins, Nativity of Jesus, birth, Ministry of Jesus, ministry, Crucifixion of Jesus, death, Resurrection of Jesus, resurrection, and Ascension of ...

.Gilles Quispel

Gilles Quispel (30 May 1916 – 2 March 2006) was a Dutch theologian and historian of Christianity and Gnosticism. He was professor of early Christian history at Utrecht University.

Early life and education

Born in Rotterdam, he was the son of ...

put it, "After all, Theosophy is a pagan, Anthroposophy a Christian form of modern Gnosis."[Sources for 'Quispel':]

Maria Carlson stated "Theosophy and Anthroposophy are fundamentally Gnostic systems in that they posit the dualism of Spirit and Matter."Rosicrucianism

Rosicrucianism () is a spiritual and cultural movement that arose in early modern Europe in the early 17th century after the publication of several texts announcing to the world a new esoteric order. Rosicrucianism is symbolized by the Rose ...

.Western esotericism

Western esotericism, also known as the Western mystery tradition, is a wide range of loosely related ideas and movements that developed within Western society. These ideas and currents are united since they are largely distinct both from orthod ...

and occultism

The occult () is a category of esoteric or supernatural beliefs and practices which generally fall outside the scope of organized religion and science, encompassing phenomena involving a 'hidden' or 'secret' agency, such as magic and mystic ...

.New Age

New Age is a range of Spirituality, spiritual or Religion, religious practices and beliefs that rapidly grew in Western world, Western society during the early 1970s. Its highly eclecticism, eclectic and unsystematic structure makes a precise d ...

.

Judaism

Rudolf Steiner wrote and lectured on Judaism and Jewish issues over much of his adult life. He was a fierce opponent of popular antisemitism, but asserted that there was no justification for the existence of Judaism and Jewish culture in the modern world, a radical assimilationist perspective which saw the Jews completely integrating into the larger society.[Ralf Sonnenberg]

"Judentum, Zionismus und Antisemitismus aus der Sicht Rudolf Steiners"

He also supported Émile Zola

Émile Édouard Charles Antoine Zola (, ; ; 2 April 184029 September 1902) was a French novelist, journalist, playwright, the best-known practitioner of the literary school of Naturalism (literature), naturalism, and an important contributor to ...

's position in the Dreyfus affair.[ Steiner emphasized Judaism's central importance to the constitution of the modern era in the West but suggested that to appreciate the spirituality of the future it would need to overcome its tendency toward abstraction.

Steiner financed the publication of the book ''Die Entente-Freimaurerei und der Weltkrieg'' (1919) by ; Steiner also wrote the foreword for the book, partly based upon his own ideas.]conspiracy theory

A conspiracy theory is an explanation for an event or situation that asserts the existence of a conspiracy (generally by powerful sinister groups, often political in motivation), when other explanations are more probable.Additional sources:

* ...

according to whom World War I was a consequence of a collusion of Freemasons

Freemasonry (sometimes spelled Free-Masonry) consists of fraternal groups that trace their origins to the medieval guilds of stonemasons. Freemasonry is the oldest secular fraternity in the world and among the oldest still-existing organizati ...

and Jews

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of History of ancient Israel and Judah, ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, rel ...

– still favorite scapegoats of the conspiracy theorists – their purpose being the destruction of Germany. Fact is that Steiner spent a large sum of money for publishing "a now classic work of anti-Masonry and anti-Judaism".Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (20 April 1889 – 30 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was the dictator of Nazi Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his suicide in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the lea ...

called anthroposophy "Jewish methods". The anthroposophical institutions in Germany were banned during Nazi rule and several anthroposophists sent to concentration camps

A concentration camp is a prison or other facility used for the internment of political prisoners or politically targeted demographics, such as members of national or ethnic minority groups, on the grounds of national security, or for exploit ...

.Camphill movement

The Camphill Movement is an initiative for social change based on the principles of anthroposophy. Camphill communities are residential communities and schools that provide support for the education, employment, and daily lives of adults and child ...

, who had converted to Christianity. Martin Buber

Martin Buber (; , ; ; 8 February 1878 – 13 June 1965) was an Austrian-Israeli philosopher best known for his philosophy of dialogue, a form of existentialism centered on the distinction between the I and Thou, I–Thou relationship and the I� ...

and Hugo Bergmann, who viewed Steiner's social ideas as a solution to the Arab–Jewish conflict, were also influenced by anthroposophy.Israel

Israel, officially the State of Israel, is a country in West Asia. It Borders of Israel, shares borders with Lebanon to the north, Syria to the north-east, Jordan to the east, Egypt to the south-west, and the Mediterranean Sea to the west. Isr ...

, including the anthroposophical kibbutz

A kibbutz ( / , ; : kibbutzim / ) is an intentional community in Israel that was traditionally based on agriculture. The first kibbutz, established in 1910, was Degania Alef, Degania. Today, farming has been partly supplanted by other economi ...

Harduf, founded by Jesaiah Ben-Aharon, forty Waldorf kindergartens and seventeen Waldorf schools

Waldorf education, also known as Steiner education, is based on the educational philosophy of Rudolf Steiner, the founder of anthroposophy. Its educational style is Holistic education, holistic, intended to develop pupils' intellectual, artistic ...

(as of 2018). A number of these organizations are striving to foster positive relationships between the Arab and Jewish populations: The Harduf Waldorf school includes both Jewish and Arab faculty and students, and has extensive contact with the surrounding Arab communities, while the first joint Arab-Jewish kindergarten was a Waldorf program in Hilf near Haifa

Haifa ( ; , ; ) is the List of cities in Israel, third-largest city in Israel—after Jerusalem and Tel Aviv—with a population of in . The city of Haifa forms part of the Haifa metropolitan area, the third-most populous metropolitan area i ...

.

Christian Community

Towards the end of Steiner's life, a group of theology students (primarily Lutheran, with some Roman Catholic members) approached Steiner for help in reviving Christianity, in particular "to bridge the widening gulf between modern science and the world of spirit".Lutheran

Lutheranism is a major branch of Protestantism that emerged under the work of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German friar and Protestant Reformers, reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practices of the Catholic Church launched ...

pastor, Friedrich Rittelmeyer, who was already working with Steiner's ideas, to join their efforts. Out of their co-operative endeavor, the ''Movement for Religious Renewal'', now generally known as The Christian Community, was born. Steiner emphasized that he considered this movement, and his role in creating it, to be independent of his anthroposophical work,religion

Religion is a range of social system, social-cultural systems, including designated religious behaviour, behaviors and practices, morals, beliefs, worldviews, religious text, texts, sanctified places, prophecies, ethics in religion, ethics, or ...

or religious denomination.

Reception

Anthroposophy's supporters include Saul Bellow

Saul Bellow (born Solomon Bellows; June 10, 1915April 5, 2005) was a Canadian-American writer. For his literary work, Bellow was awarded the Pulitzer Prize, the 1976 Nobel Prize in Literature, and the National Medal of Arts. He is the only write ...

,Selma Lagerlöf

Selma Ottilia Lovisa Lagerlöf (, , ; 20 November 1858 – 16 March 1940) was a Swedish writer. She published her first novel, ''Gösta Berling's Saga'', at the age of 33. She was the first woman to win the Nobel Prize in Literature, which she was ...

,Andrei Bely

Boris Nikolaevich Bugaev (, ; – 8 January 1934), better known by the pen name Andrei Bely or Biely, was a Russian novelist, Symbolist poet, theorist and literary critic. He was a committed anthroposophist and follower of Rudolf Steiner. Hi ...

,Joseph Beuys

Joseph Heinrich Beuys ( ; ; 12 May 1921 – 23 January 1986) was a German artist, teacher, performance artist, and Aesthetics, art theorist whose work reflected concepts of humanism and sociology. With Heinrich Böll, , Caroline Tisdall, Rober ...

,Owen Barfield

Arthur Owen Barfield (9 November 1898 – 14 December 1997) was an English philosopher, author, poet, critic, and member of the Inklings.

Life

Barfield was born in London, to Elizabeth (née Shoults; 1860–1940) and Arthur Edward Barfield (186 ...

, architect Walter Burley Griffin

Walter Burley Griffin (November 24, 1876February 11, 1937) was an American architect and landscape architect. He designed Canberra, Australia's capital city, the New South Wales towns of Griffith, New South Wales, Griffith and Leeton, New So ...

,[ ]Wassily Kandinsky