Sir William Petty on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

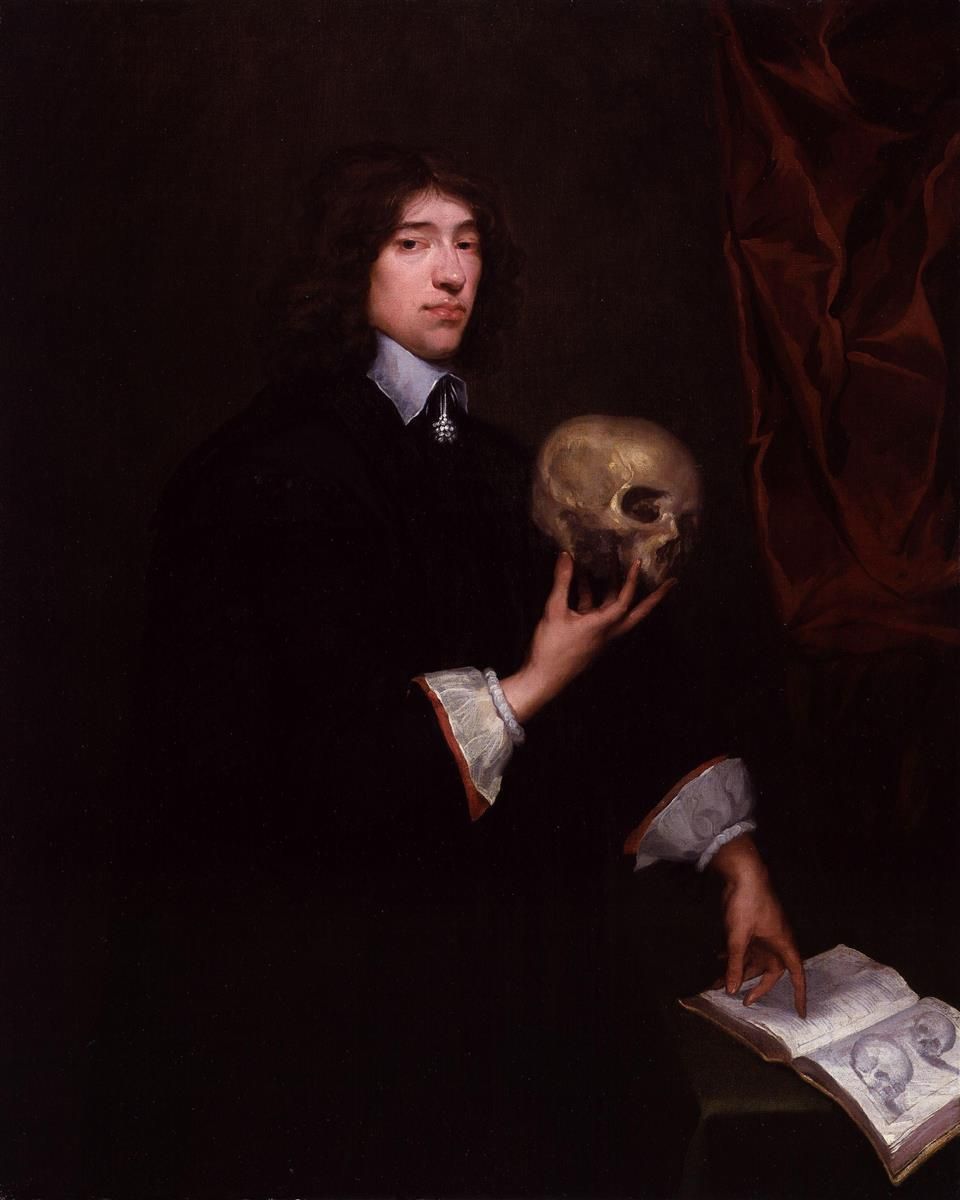

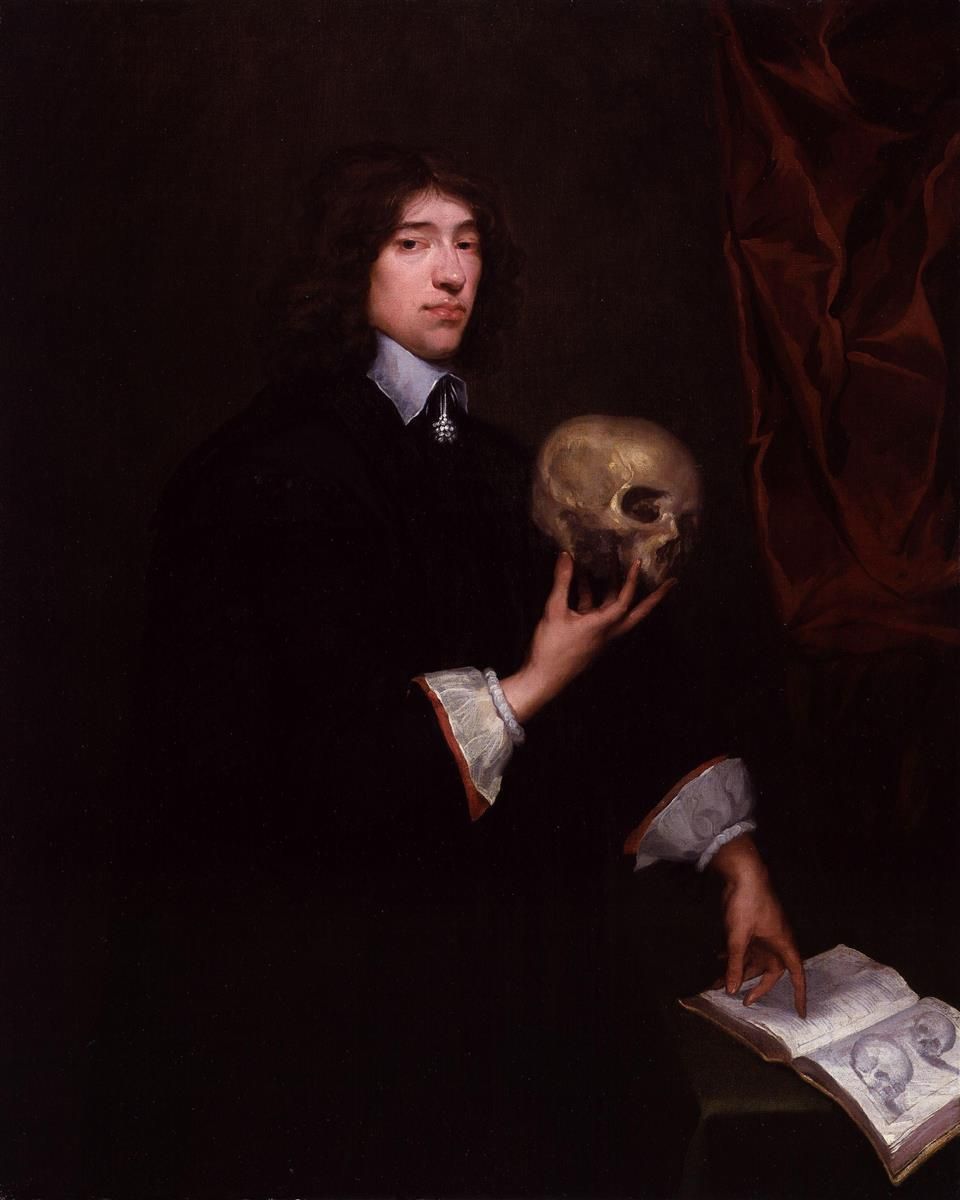

Sir William Petty (26 May 1623 – 16 December 1687) was an English economist, physician, scientist and philosopher. He first became prominent serving

In 1652, he took a leave of absence and travelled with

In 1652, he took a leave of absence and travelled with

Political Arithmetick

Petty made a practical study of the

Archive for the History of Economic Thought: "William Petty"

* *

Petty FitzMaurice (Lansdowne) family tree

*

Search the collection

Kenmare Journal – A Bridge to the Past.

{{DEFAULTSORT:Petty, William 1623 births 1687 deaths 17th-century English medical doctors 17th-century English male writers 17th-century English economists 17th-century English philosophers People from Romsey Members of the pre-1707 English Parliament for constituencies in Cornwall 17th-century English businesspeople English statisticians Founder fellows of the Royal Society Alumni of the University of Oxford Fellows of Brasenose College, Oxford English surveyors

Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell (25 April 15993 September 1658) was an English statesman, politician and soldier, widely regarded as one of the most important figures in British history. He came to prominence during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms, initially ...

and the Commonwealth

A commonwealth is a traditional English term for a political community founded for the common good. The noun "commonwealth", meaning "public welfare, general good or advantage", dates from the 15th century. Originally a phrase (the common-wealth ...

in Ireland

Ireland (, ; ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe. Geopolitically, the island is divided between the Republic of Ireland (officially Names of the Irish state, named Irelan ...

. He developed efficient methods to survey the land that was to be confiscated and given to Cromwell's soldiers. He also remained a significant figure under King Charles II and King James II

James II and VII (14 October 1633 – 16 September 1701) was King of England and Ireland as James II and King of Scotland as James VII from the death of his elder brother, Charles II, on 6 February 1685, until he was deposed in the 1688 Glori ...

, as did many others who had served Cromwell.

Petty was also a scientist, inventor, and merchant, a charter member of the Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

, and briefly a member of the Parliament of England

The Parliament of England was the legislature of the Kingdom of England from the 13th century until 1707 when it was replaced by the Parliament of Great Britain. Parliament evolved from the Great Council of England, great council of Lords Spi ...

. However, he is best remembered for his theories on economics and his methods of ''political arithmetic''. He was knighted in 1661.

Life

Early life

Petty was born inLondon

London is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of both England and the United Kingdom, with a population of in . London metropolitan area, Its wider metropolitan area is the largest in Wester ...

, where his father and grandfather were clothiers. He was a precocious and intelligent youth and in 1637 became a cabin boy

A cabin boy or ship's boy is a boy or young man who waits on the officers and passengers of a ship, especially running errands for the captain. The modern merchant navy successor to the cabin boy is the steward's assistant.

Duties

Cabin boys ...

. His readiness to provide caricatures of fellow crew members won him few friends. He also learnt of his defective sight when he failed to spot a landmark he had been told to look for. The captain, who had by this time seen the landmark from the deck for himself " drubbed him with a cord". He was subsequently set ashore in Normandy

Normandy (; or ) is a geographical and cultural region in northwestern Europe, roughly coextensive with the historical Duchy of Normandy.

Normandy comprises Normandy (administrative region), mainland Normandy (a part of France) and insular N ...

after breaking his leg on board. After this setback, he applied in Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

to study with the Jesuit

The Society of Jesus (; abbreviation: S.J. or SJ), also known as the Jesuit Order or the Jesuits ( ; ), is a religious order (Catholic), religious order of clerics regular of pontifical right for men in the Catholic Church headquartered in Rom ...

s in Caen

Caen (; ; ) is a Communes of France, commune inland from the northwestern coast of France. It is the Prefectures in France, prefecture of the Departments of France, department of Calvados (department), Calvados. The city proper has 105,512 inha ...

, supporting himself by teaching English. After a year, he returned to England, and had by now a thorough knowledge of Latin, Greek

Greek may refer to:

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor of all kno ...

, French, mathematics, and astronomy.

Career

At Oxford

After the Third Siege of Oxford had resulted in the garrison surrendering to the parliamentarians on 24 June 1646, Petty arrived in the town and was offered a fellowship atBrasenose College

Brasenose College (BNC) is one of the constituent colleges of the University of Oxford in the United Kingdom. It began as Brasenose Hall in the 13th century, before being founded as a college in 1509. The library and chapel were added in the m ...

and studied medicine at the University

A university () is an educational institution, institution of tertiary education and research which awards academic degrees in several Discipline (academia), academic disciplines. ''University'' is derived from the Latin phrase , which roughly ...

. He befriended Hartlib and Boyle and became a member of the Oxford Philosophical Club

The Oxford Philosophical Club, also referred to as the "Oxford Circle", was to a group of natural philosophers, mathematicians, physicians, virtuosi and dilettanti gathering around John Wilkins FRS (1614–1672) at Oxford University, Oxford in t ...

.

Musician, doctor, academic and surveyor

By 1651, Petty was an anatomy instructor atBrasenose College, Oxford

Brasenose College (BNC) is one of the Colleges of the University of Oxford, constituent colleges of the University of Oxford in the United Kingdom. It began as Brasenose Hall in the 13th century, before being founded as a college in 1509. The l ...

, as deputy to Thomas Clayton the younger. With a second doctor, Thomas Willis

Thomas Willis Fellow of the Royal Society, FRS (27 January 1621 – 11 November 1675) was an English physician who played an important part in the history of anatomy, neurology, and psychiatry, and was a founding member of the Royal Society.

L ...

, Petty was involved in treating Anne Greene, a woman who survived her own hanging and was subsequently pardoned because her survival was widely held to be an act of divine intervention

Divine intervention is an event that occurs when a deity (i.e. God or gods) becomes actively involved in changing some situation in human affairs. In contrast to other kinds of divine action, the expression "divine ''intervention''" implies that ...

. The event was widely written about at the time, and helped to build Petty's career and reputation. He was also appointed Gresham Professor of Music by the Corporation of the City of London

The City of London Corporation, officially and legally the Mayor and Commonalty and Citizens of the City of London, is the local authority of the City of London, the historic centre of London and the location of much of the United Kingdom's fi ...

in 1650, retaining the post until 1660.

In 1652, he took a leave of absence and travelled with

In 1652, he took a leave of absence and travelled with Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell (25 April 15993 September 1658) was an English statesman, politician and soldier, widely regarded as one of the most important figures in British history. He came to prominence during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms, initially ...

's army in Ireland as physician-general, responsible to Cromwell's son-in-law, Charles Fleetwood

Charles Fleetwood ( 1618 – 4 October 1692) was an English lawyer from Northamptonshire, who served with the Parliamentarian army during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. A close associate of Oliver Cromwell, to whom he was related by marriage ...

. His opposition to conventional universities, being committed to 'new science' as inspired by Francis Bacon

Francis Bacon, 1st Viscount St Alban (; 22 January 1561 – 9 April 1626) was an English philosopher and statesman who served as Attorney General and Lord Chancellor of England under King James I. Bacon argued for the importance of nat ...

and imparted by his afore-mentioned acquaintances, perhaps pushed him from Oxford. He was pulled to Ireland perhaps by a sense of ambition and desire for wealth and power. He secured the contract for charting Ireland in 1654, so that those who had lent funds to Cromwell's army might be repaid in land – a means of ensuring the army was self-financing. This enormous task, which he completed in 1656, became known as the Down Survey, later published (1685) as '' Hiberniae Delineatio''. As his reward, he acquired approximately in Kenmare

Kenmare () is a small town in the south of County Kerry, Ireland. The name Kenmare is the anglicised form of ''Ceann Mara'', meaning "head of the sea", referring to the head of Kenmare Bay. It is also a townland and civil parish.

Location

Ken ...

, in southwest Ireland, and £9,000. This personal gain to Petty led to persistent court cases on charges of bribery and breach of trust, until his death.

Back in England, as a Cromwellian supporter, he ran successfully for Parliament in 1659 for West Looe.

Projector

Petty gained possession of the three baronies of Iveragh, Glanarought and Dunkerron inCounty Kerry

County Kerry () is a Counties of Ireland, county on the southwest coast of Republic of Ireland, Ireland, within the Provinces of Ireland, province of Munster and the Southern Region, Ireland, Southern Region. It is bordered by two other countie ...

. He soon became a projector

A projector or image projector is an optical device that projects an image (or moving images) onto a surface, commonly a projection screen. Most projectors create an image by shining a light through a small transparent lens, but some newer type ...

, developing extensive plans for an ironworks

An ironworks or iron works is an industrial plant where iron is smelted and where heavy iron and steel products are made. The term is both singular and plural, i.e. the singular of ''ironworks'' is ''ironworks''.

Ironworks succeeded bloome ...

and a fishery

Fishery can mean either the enterprise of raising or harvesting fish and other aquatic life or, more commonly, the site where such enterprise takes place ( a.k.a., fishing grounds). Commercial fisheries include wild fisheries and fish far ...

on his substantial estates in Kerry. Although he had great expectations of his application of his scientific methods to improvement, little came of these. He began by applying his political arithmetic to his own estates, surveying the population and livestock to develop an understanding of the land's potential. The ironworks was established in 1660.

Natural philosopher

Despite his political allegiances, Petty was well-treated at the Restoration in 1660, although he lost some of his Irish lands. Charles II, at their first meeting, brushed aside Petty's apologies for his past support for Cromwell, "seeming to regard them as needless", and discussed his experiments into the mechanics of shipping instead. In 1661 he was elected as a Member of Parliament forInistioge

Inistioge (; ) is a small village in County Kilkenny, Republic of Ireland, Ireland. Historically, its name has been spelt as Ennistioge, Ennisteage, and in other ways. The village is situated on the River Nore, southeast of Kilkenny. Inistioge ...

in the Parliament of Ireland

The Parliament of Ireland () was the legislature of the Lordship of Ireland, and later the Kingdom of Ireland, from 1297 until the end of 1800. It was modelled on the Parliament of England and from 1537 comprised two chambers: the Irish Hou ...

. In 1662, he was admitted as a charter member of the Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

of the same year. This year also saw him write his first work on economics, ''Treatise of Taxes and Contributions''. Petty counted naval architecture among his many scientific interests. He had become convinced of the superiority of double-hulled boats, although they were not always successful; a ship called the ''Experiment'' reached Porto

Porto (), also known in English language, English as Oporto, is the List of cities in Portugal, second largest city in Portugal, after Lisbon. It is the capital of the Porto District and one of the Iberian Peninsula's major urban areas. Porto c ...

in 1664, but sank on the way back.

Ireland and later life

Petty was knighted in 1661 by Charles II and served as MP forInistioge

Inistioge (; ) is a small village in County Kilkenny, Republic of Ireland, Ireland. Historically, its name has been spelt as Ennistioge, Ennisteage, and in other ways. The village is situated on the River Nore, southeast of Kilkenny. Inistioge ...

from 1661-66. He remained in Ireland until 1685. He was a friend of Samuel Pepys

Samuel Pepys ( ; 23 February 1633 – 26 May 1703) was an English writer and Tories (British political party), Tory politician. He served as an official in the Navy Board and Member of Parliament (England), Member of Parliament, but is most r ...

.

The events that took him from Oxford to Ireland marked a shift from medicine and the physical sciences to the social sciences, and Petty lost all his Oxford offices. The social sciences became the area that he studied for the rest of his life. His focus became greater income from Irish colonization, and his works describe that country and propose many remedies for what he characterized as its backward condition. He helped found the Dublin Society in 1682. Returning ultimately to London in 1685, he died in 1687. He was buried in Romsey Abbey

Romsey Abbey is the name currently given to a parish church of the Church of England in Romsey, a market town in Hampshire, England. Until the Dissolution of the Monasteries it was the church of a Benedictine Order, Benedictine nunnery. The surv ...

.

Family

William Petty marriedElizabeth Waller

Elizabeth Waller (born 1943 in Cheshire, England) is a British costume designer for theatre, television and film. She began her costume career in theatre, before joining the BBC costume team, where her period costume work was acclaimed for its att ...

in 1667. She was a daughter of the regicide

Regicide is the purposeful killing of a monarch or sovereign of a polity and is often associated with the usurpation of power. A regicide can also be the person responsible for the killing. The word comes from the Latin roots of ''regis'' ...

Sir Hardress Waller

Sir Hardress Waller (1666) was born in Kent and settled in Ireland during the 1630s. A first cousin of Roundhead, Parliamentarian general William Waller, he fought for Roundhead, Parliament in the Wars of the Three Kingdoms, becoming a leading ...

(whose life was spared after the Restoration) and Elizabeth Dowdall. She had been previously married to Sir Maurice Fenton, who died in 1664. She was given the title Baroness Shelburne for life. They had three surviving children:

* Charles Petty, 1st Baron Shelburne

Earl of Shelburne is a title that has been created twice while the title of Baron Shelburne has been created three times. The Shelburne title was created for the first time in the Peerage of Ireland in 1688 when Elizabeth, Lady Petty, was made ...

* Henry Petty, 1st Earl of Shelburne

Henry Petty, 1st Earl of Shelburne PC (I) (22 October 1675 – 17 April 1751) was an Anglo-Irish peer and politician who sat in the House of Commons from 1715 to 1727.

Background

Petty was a younger son of Sir William Petty and Elizabeth, Baro ...

* Anne, who married Thomas Fitzmaurice, 1st Earl of Kerry.

Neither Charles nor Henry had male issue and the Shelburne title passed by a special remainder to Anne's son John Petty, 1st Earl of Shelburne

John Petty Fitzmaurice, 1st Earl of Shelburne PC (Ire) (1706 – 14 May 1761), known as John FitzMaurice until 1751 and as The Viscount FitzMaurice between 1751 and 1753, was an Anglo-Irish peer and politician. He was the father of William ...

, who took his mother's surname, and whose descendants hold the title Marquis of Lansdowne. Her grandson William Petty, 2nd Earl of Shelburne

William Petty Fitzmaurice, 1st Marquess of Lansdowne (2 May 17377 May 1805), known as the Earl of Shelburne between 1761 and 1784, by which title he is generally known to history, was an Anglo-Irish Whig (British political party), Whig states ...

, praised her as a woman of strong character and intelligence, the only person who could manage her bad-tempered and tyrannical husband.

Economic works and theories

Two men crucially influenced Petty's economic theories. The first wasThomas Hobbes

Thomas Hobbes ( ; 5 April 1588 – 4 December 1679) was an English philosopher, best known for his 1651 book ''Leviathan (Hobbes book), Leviathan'', in which he expounds an influential formulation of social contract theory. He is considered t ...

, for whom Petty acted as personal secretary. According to Hobbes, theory should set out the rational requirements for "civil peace and material plenty". As Hobbes had centred on peace, Petty chose prosperity.

The influence of Francis Bacon

Francis Bacon, 1st Viscount St Alban (; 22 January 1561 – 9 April 1626) was an English philosopher and statesman who served as Attorney General and Lord Chancellor of England under King James I. Bacon argued for the importance of nat ...

was also profound. Bacon, and indeed Hobbes, held the conviction that mathematics and the senses must be the basis of all rational sciences. This passion for accuracy led Petty to famously declare that his form of science would only use measurable phenomena and would seek quantitative precision, rather than rely on comparatives or superlatives, yielding a new subject that he named "political arithmetic". Petty thus carved a niche for himself as the first dedicated economic scientist, amidst the merchant-pamphleteers, such as Thomas Mun

Sir Thomas Mun (; 17 June 157121 July 1641) was an English writer on economics and is often referred to as the last of the early mercantilists. Most notably, he is known for serving as the director of the East India Company. Due to his strong ...

or Josiah Child

Sir Josiah Child, 1st Baronet, (c. 1630/31 – 22 June 1699) was an English economist, merchant and politician. He was an economist proponent of mercantilism and governor of the British East India Company, East India Company. He led the compa ...

, and philosopher-scientists occasionally discussing economics, such as John Locke

John Locke (; 29 August 1632 (Old Style and New Style dates, O.S.) – 28 October 1704 (Old Style and New Style dates, O.S.)) was an English philosopher and physician, widely regarded as one of the most influential of the Enlightenment thi ...

.

He was indeed writing before the true development of political economy

Political or comparative economy is a branch of political science and economics studying economic systems (e.g. Marketplace, markets and national economies) and their governance by political systems (e.g. law, institutions, and government). Wi ...

. As such, many of his claims for precision are of imperfect quality. Nonetheless, Petty wrote three main works on economics, ''Treatise of Taxes and Contributions'' (written in 1662), ''Verbum Sapienti'' (1665) and ''Quantulumcunque Concerning Money'' (1682). These works, which received great attention in the 1690s, show his theories on major areas of what would later become economics. What follows is an analysis of his most important theories, those on fiscal contributions, national wealth, the money supply and circulation velocity, value, the interest rate, international trade and government investment.

Many of his economic writings were collected by Charles Henry Hull in 1899 in '' The Economic Writings of Sir William Petty''.

Hull, in his scholarly article ' Petty's Place in the History of Economic Theory' (1900) proposed a division of the economic writings of Petty in three (or four) groups:

* the first group, written when Petty had returned to London after finishing his " Down Survey" in Ireland, consists mainly of ''A Treatise of Taxes & Contributions'' (written and first published 1662) and ''Verbum Sapienti'' (written 1665, printed 1691). These texts relate to the discussions about fiscal issues, following the Restoration and the expenses of the first Dutch war

The First Anglo-Dutch War, or First Dutch War, was a naval conflict between the Commonwealth of England and the Dutch Republic. Largely caused by disputes over trade, it began with English attacks on Dutch merchant shipping, but expanded to vast ...

.

* the second group holds ''The Political Anatomy of Ireland'' and ''Political Arithmetick.'' These texts were written some ten years later in Ireland. As Hull writes, the "direct impulse to their writing came from Dr. Edward Chamberlayne's ''Present State of England'', published 1669".

* Again ten years later the third group of pamphlets was written, that were contributions to the dispute whether London was a larger city than Paris, and that are titled the ''Essays in Political Arithmetick'' by Hull. This group of pamphlets had a close relation to John Graunt

John Graunt (24 April 1620 – 18 April 1674) has been regarded as the founder of demography. Graunt was one of the first demographers, and perhaps the first epidemiologist, though by profession he was a haberdasher. He was bankrupted later in ...

's ''Observations upon the Bills of Mortality of London.''

* The ''Quantulumcunque concerning Money'' (written in 1682, and printed in 1695, and perhaps in 1682), can probably be considered as belonging to a group of its own.

The division given here was still used by scholars at the end of the twentieth century.See for instance for instance and . One may wonder why Hull does not mention ''A Treatise of Ireland'' in this list. He was the first to have this manuscript, dated 1687, printed. ().

Fiscal contributions

By Petty's time, England was engaged in war with Holland, and in the first three chapters of ''Treatise of Taxes and Contributions'', Petty sought to establish principles of taxation and public expenditure, to which the monarch could adhere, when deciding how to raise money for the war. Petty lists six kinds of public charge, namely defence, governance, the ''pastorage of men's souls'', education, the maintenance of ''impotents of all sorts'' and infrastructure, or ''things of universal good''. He then discusses general and particular causes of changes in these charges. He thinks that there is great scope for reduction of the first four public charges, and recommends increased spending on care for the elderly, sick, orphans, etc., as well as the government employment of ''supernumeraries''. Petty was interested in the extent to which taxes could be raised without inciting rebellion On the issue of raising taxes, Petty was a definite proponent ofconsumption tax

A consumption tax is a tax levied on consumption spending on goods and services. The tax base of such a tax is the money spent on Consumption (economics), consumption. Consumption taxes are usually indirect, such as a sales tax or a value-added ta ...

es. He recommended that in general taxes should be just sufficient to meet the various types of public charges that he listed. They should also be horizontally equitable, regular and proportionate. He condemned poll tax

A poll tax, also known as head tax or capitation, is a tax levied as a fixed sum on every liable individual (typically every adult), without reference to income or resources. ''Poll'' is an archaic term for "head" or "top of the head". The sen ...

es as very unequal and excise on beer as taxing the poor excessively. He recommended a much higher quality of statistical information, to raise taxes more fairly. Imports should be taxed, but only in such a way that would put them on a level playing field with domestic produce. A vital aspect of economies at this time was that they were transforming from barter

In trade, barter (derived from ''bareter'') is a system of exchange (economics), exchange in which participants in a financial transaction, transaction directly exchange good (economics), goods or service (economics), services for other goods ...

economies to money economies. Linked to this, and aware of the scarcity of money, Petty recommends that taxes be payable in forms other than gold or silver, which he estimated to be less than 1% of national wealth. To him, too much importance was placed on money, "which is to the whole effect of the Kingdom… not ven

Venezuela, officially the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela, is a country on the northern coast of South America, consisting of a continental landmass and many islands and islets in the Caribbean Sea. It comprises an area of , and its popul ...

one to 100".

National income accounting

In making the above estimate, Petty introduced in the first two chapters of ''Verbum Sapienti'' the first rigorous assessments ofnational income

A variety of measures of national income and output are used in economics to estimate total economic activity in a country or region, including gross domestic product (GDP), Gross national income (GNI), net national income (NNI), and adjusted nati ...

and wealth. To him, it was all too obvious that a country's wealth lay in more than just gold and silver. He worked off an estimation that the average personal income was £6 13s 4d per annum, with a population of six million, meaning that national income would be £40m. Petty's theory produced estimates, some more reliable than others, for the various components of national income, including land, ships, personal estates and housing. He then distinguished between the stocks (£250m) and the flows yielding from them (£15m). The discrepancy between these flows and his estimate for national income (£40m) leads Petty to postulate that the other £25m is the yield from what must be £417m of labour stock, the "value of the people". This gave a total wealth for England in the 1660s of £667m.

Statistics

Petty's only statistical technique is the use of simple averages. He would not be a statistician by today's standards but during his time a statistician was merely one that employed the use ofquantitative data

Quantitative research is a research strategy that focuses on quantifying the collection and analysis of data. It is formed from a deductive approach where emphasis is placed on the testing of theory, shaped by empiricist and positivist philoso ...

. Because obtaining census data was difficult, if not impossible, especially for Ireland, he applied methods of estimation

Estimation (or estimating) is the process of finding an estimate or approximation, which is a value that is usable for some purpose even if input data may be incomplete, uncertain, or unstable. The value is nonetheless usable because it is d ...

. The way in which he would estimate the population would be to start with estimating the population of London. He would do this by either estimating it by exports or by deaths. His method of using exports is by considering that a 30 per cent increase in exports corresponds to a similar proportionate increase in population. The way he would use deaths would be by multiplying the number of deaths by 30 – estimating that one out of thirty people dies each year. To obtain the population of all of England he would multiply the population of London by 8. Such a simple use of estimation could have easily have been abused and Petty was accused more than once of doctoring the figures for the Crown. (Henry Spiegel)

Money supply and circulation

This figure for the stock of wealth was contrasted with amoney supply

In macroeconomics, money supply (or money stock) refers to the total volume of money held by the public at a particular point in time. There are several ways to define "money", but standard measures usually include currency in circulation (i ...

in gold and silver of only £6m. Petty believed that there was a certain amount of money that a nation needed to drive its trade. Hence it was possible to have too little money circulating in an economy, which would mean that people would have to rely on barter

In trade, barter (derived from ''bareter'') is a system of exchange (economics), exchange in which participants in a financial transaction, transaction directly exchange good (economics), goods or service (economics), services for other goods ...

. It would also be possible for there to be too much money in an economy. But the topical question was, as he asks in chapter 3 of ''Verbum Sapienti'', would £6m be enough to drive a nation's trade, especially if the King wanted to raise additional funds for the war with Holland?

The answer for Petty lay in the velocity of money

image:M3 Velocity in the US.png, 300px, Similar chart showing the logged velocity (green) of a broader measure of money M3 that covers M2 plus large institutional deposits. The US no longer publishes official M3 measures, so the chart only runs t ...

's circulation. Anticipating the quantity theory of money

The quantity theory of money (often abbreviated QTM) is a hypothesis within monetary economics which states that the general price level of goods and services is directly proportional to the amount of money in circulation (i.e., the money supply) ...

often said to be initiated by John Locke

John Locke (; 29 August 1632 (Old Style and New Style dates, O.S.) – 28 October 1704 (Old Style and New Style dates, O.S.)) was an English philosopher and physician, widely regarded as one of the most influential of the Enlightenment thi ...

, whereby economic output (''Y'') times price level (''p'') = money supply (''MS'') times velocity of circulation (''v''), Petty stated that if economic output was to be increased for a given money supply and price level, 'revolutions' must occur in smaller circles (i.e. velocity of circulation must be higher). This could be done through the establishment of a bank. He explicitly stated in ''Verbum Sapienti'' "nor is money wanting to answer all the ends of a well-policed state, notwithstanding the great decreases thereof which have happened within these Twenty years" and that higher velocity is the answer. He also mentions that there is nothing unique about gold and silver in fulfilling the functions of money and that money is the means to an end, not the end itself:

Nor were it hard to substitute in the place of Money old and silver(were a comptency of it wanting) what should be equivalent unto it. For Money is but the Fat of the Body-Politick, whereof too much doth often hinder its agility, as too little makes it sick... so doth Money in the State quicken its Action, feeds from abroad in the time of Dearth at home.'What is striking about these passages is his intellectual rigour, which put him far ahead of the

mercantilist

Mercantilism is a nationalist economic policy that is designed to maximize the exports and minimize the imports of an economy. It seeks to maximize the accumulation of resources within the country and use those resources for one-sided trade. ...

writers of earlier in the century. The use of biological analogies to illustrate his point, a trend continued by the physiocrats

Physiocracy (; from the Greek for "government of nature") is an economic theory developed by a group of 18th-century Age of Enlightenment French economists. They believed that the wealth of nations derived solely from the value of "land agricult ...

in France early in the 18th century, was also unusual.

Theory of value

On value, Petty continued the debate begun byAristotle

Aristotle (; 384–322 BC) was an Ancient Greek philosophy, Ancient Greek philosopher and polymath. His writings cover a broad range of subjects spanning the natural sciences, philosophy, linguistics, economics, politics, psychology, a ...

, and chose to develop an input-based theory of value: "all things ought to be valued by two natural Denominations, which is Land and Labour" (p. 44). Both of these would be prime sources of taxable income

Taxable income refers to the base upon which an income tax system imposes tax. In other words, the income over which the government imposed tax. Generally, it includes some or all items of income and is reduced by expenses and other deductions. T ...

. Like Richard Cantillon

Richard Cantillon (; 1680s – ) was an Irish-French economist and author of '' Essai Sur La Nature Du Commerce En Général'' (''Essay on the Nature of Trade in General''), a book considered by William Stanley Jevons to be the "cradle of ...

after him, he sought to devise some equation or par between the "mother and father" of output, land and labour, and to express value accordingly. He still included general productivity

Productivity is the efficiency of production of goods or services expressed by some measure. Measurements of productivity are often expressed as a ratio of an aggregate output to a single input or an aggregate input used in a production proce ...

, one's "art and industry". He applied his theory of value to rent. The natural rent of a land was the excess of what a labourer produces on it in a year over what he ate himself and traded for necessities. It was therefore the profit

Profit may refer to:

Business and law

* Profit (accounting), the difference between the purchase price and the costs of bringing to market

* Profit (economics), normal profit and economic profit

* Profit (real property), a nonpossessory inter ...

above the various costs related to the factors involved in production.

Interest rate

The natural rate of rent is related to his theories onusury

Usury () is the practice of making loans that are seen as unfairly enriching the lender. The term may be used in a moral sense—condemning taking advantage of others' misfortunes—or in a legal sense, where an interest rate is charged in e ...

. At the time, many religious writers still condemned the charging of interest as sinful. Petty also involved himself in the debate on usury and interest rate

An interest rate is the amount of interest due per period, as a proportion of the amount lent, deposited, or borrowed (called the principal sum). The total interest on an amount lent or borrowed depends on the principal sum, the interest rate, ...

s, regarding the phenomenon as a reward for forbearance on the part of the lender. Incorporating his theories of value, he asserted that, with perfect security, the rate of interest should equal the rent for land that the principal could have bought – again, a precocious insight into what would later become general equilibrium findings. Where security was more "casual", the return should be greater – a return for risk. Having established the justification for usury itself, that of forbearance

Forbearance, in the context of a mortgage process, is a special agreement between the lender and the borrower to delay a foreclosure. The literal meaning of forbearance is "holding back". This is also referred to as mortgage moratorium.

Applic ...

, he then shows his Hobbesian

Thomas Hobbes ( ; 5 April 1588 – 4 December 1679) was an English philosopher, best known for his 1651 book ''Leviathan'', in which he expounds an influential formulation of social contract theory. He is considered to be one of the founders ...

qualities, arguing against any government regulation of the interest rate, pointing to the "vanity and fruitlessness of making civil positive laws against the laws of nature".

''Laissez-faire'' governance

This is one of the major themes of Petty's writings, summed up by his use of the phrase ''vadere sicut vult'', from which ''laissez-faire

''Laissez-faire'' ( , from , ) is a type of economic system in which transactions between private groups of people are free from any form of economic interventionism (such as subsidies or regulations). As a system of thought, ''laissez-faire'' ...

'' is derived. As mentioned earlier, the motif of medicine was also useful to Petty, and he warned against over-interference by the government in the economy, seeing it as analogous to a physician tampering excessively with his patient. He applied this to monopolies, controls on the exportation of money and on the trade of commodities. They were, to him, vain and harmful to a nation. He recognised the price effects of monopolies, citing the French king's salt monopoly as an example. In another work, ''Political Arithmetic'', Petty also recognised the importance of economies of scale. He described the phenomenon of the division of labour, asserting that a good is both of better quality and cheaper, if many work on it. Petty said that the gain is greater "as the manufacture itself is greater".

Foreign exchange and control of trade

On the efflux ofspecie

Specie may refer to:

* Coins or other metal money in mass circulation

* Bullion coins

* Hard money (policy)

* Commodity money

* Specie Circular, 1836 executive order by US President Andrew Jackson regarding hard money

* Specie Payment Resumption A ...

, Petty thought it vain to try to control it, and dangerous, as it would leave the merchants to decide what goods a nation buys with the smaller amount of money. He noted in ''Quantulumcunque concerning money'' that countries plentiful in gold have no such laws restricting specie

Specie may refer to:

* Coins or other metal money in mass circulation

* Bullion coins

* Hard money (policy)

* Commodity money

* Specie Circular, 1836 executive order by US President Andrew Jackson regarding hard money

* Specie Payment Resumption A ...

. On exports in general, he regarded prescriptions, such as recent Acts of Parliament forbidding the export of wool and yarn, as "burthensome". Further restrictions "would do us twice as much harm as the losse of our said Trade" (p. 59), albeit with a concession that he is no expert in the study of the wool trade.

On prohibiting imports, for example from Holland, such restrictions did little other than drive up prices, and were only useful if imports vastly exceeded exports. Petty saw far more use in going to Holland and learning whatever skills they have than trying to resist nature. Epitomizing his viewpoint, he thought it preferable to sell cloth for "debauching" foreign wines, rather than leave the clothiers unemployed.

Division of labour

In hiPolitical Arithmetick

Petty made a practical study of the

division of labour

The division of labour is the separation of the tasks in any economic system or organisation so that participants may specialise ( specialisation). Individuals, organisations, and nations are endowed with or acquire specialised capabilities, a ...

, showing its existence and usefulness in Dutch shipyards. Classically the workers in a shipyard would build ships as units, finishing one before starting another. But the Dutch had it organised with several teams each doing the same tasks for successive ships. People with a particular task to do must have discovered new methods that were only later observed and justified by writers on political economy

Political or comparative economy is a branch of political science and economics studying economic systems (e.g. Marketplace, markets and national economies) and their governance by political systems (e.g. law, institutions, and government). Wi ...

.

Petty also applied the principle to his survey of Ireland. His breakthrough was to divide up the work so that large parts of it could be done by people with no extensive training.

Urban society

Petty projected the growth of the city of London and supposed that it might swallow the rest of England – not so far from what actually happened:Now, if the city double its people in 40 years, and the present number be 670,000, and if the whole territory be 7,400,000, and double in 360 years, as aforesaid, then by the underwritten table it appears that A.D. 1840 the people of the city will be 10,718,880, and those of the whole country but 10,917,389, which is but inconsiderably more. Wherefore it is certain and necessary that the growth of the city must stop before the said year 1840, and will be at its utmost height in the next preceding period, A.D. 1800, when the number of the city will be eight times its present number, 5,359,000. And when (besides the said number) there will be 4,466,000 to perform the tillage, pasturage, and other rural works necessary to be done without the said city.He imagined a future in which "the city of London is seven times bigger than now, and that the inhabitants of it are 4,690,000 people, and that in all the other cities, ports, towns, and villages, there are but 2,710,000 more". He expected this some time around 1800, extrapolating existing trends. Long before

Malthus

Thomas Robert Malthus (; 13/14 February 1766 – 29 December 1834) was an English economist, cleric, and scholar influential in the fields of political economy and demography.

In his 1798 book ''An Essay on the Principle of Population'', Mal ...

, he noticed the potential of the human population to increase. But he also saw no reason why such a society should not be prosperous.

Legacy

Petty is best remembered for hiseconomic history

Economic history is the study of history using methodological tools from economics or with a special attention to economic phenomena. Research is conducted using a combination of historical methods, statistical methods and the Applied economics ...

and statistical writings, preceding the work of Adam Smith

Adam Smith (baptised 1723 – 17 July 1790) was a Scottish economist and philosopher who was a pioneer in the field of political economy and key figure during the Scottish Enlightenment. Seen by some as the "father of economics"——— or ...

, and for being a founding member of the Royal Society. Of particular interest were his forays into statistical analysis

Statistical inference is the process of using data analysis to infer properties of an underlying probability distribution.Upton, G., Cook, I. (2008) ''Oxford Dictionary of Statistics'', OUP. . Inferential statistical analysis infers properties of ...

. Petty's work in political arithmetic, along with the work of John Graunt

John Graunt (24 April 1620 – 18 April 1674) has been regarded as the founder of demography. Graunt was one of the first demographers, and perhaps the first epidemiologist, though by profession he was a haberdasher. He was bankrupted later in ...

, laid the foundation for modern census techniques. This work in statistical analysis, when further expanded by writers like Josiah Child

Sir Josiah Child, 1st Baronet, (c. 1630/31 – 22 June 1699) was an English economist, merchant and politician. He was an economist proponent of mercantilism and governor of the British East India Company, East India Company. He led the compa ...

documented some of the first expositions of modern insurance. Vernon Louis Parrington

Vernon Louis Parrington (August 3, 1871 – June 16, 1929) was an American literary historian, scholar, and college football coach. His three-volume history of American letters, ''Main Currents in American Thought'', won the Pulitzer Prize for H ...

notes him as an early expositor of the labour theory of value

The labor theory of value (LTV) is a theory of value that argues that the exchange value of a good or service is determined by the total amount of " socially necessary labor" required to produce it. The contrasting system is typically known as ...

as discussed in ''Treatise of Taxes'' in 1692.

He influenced several future economists, including Richard Cantillon

Richard Cantillon (; 1680s – ) was an Irish-French economist and author of '' Essai Sur La Nature Du Commerce En Général'' (''Essay on the Nature of Trade in General''), a book considered by William Stanley Jevons to be the "cradle of ...

, Adam Smith

Adam Smith (baptised 1723 – 17 July 1790) was a Scottish economist and philosopher who was a pioneer in the field of political economy and key figure during the Scottish Enlightenment. Seen by some as the "father of economics"——— or ...

, Karl Marx

Karl Marx (; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, political theorist, economist, journalist, and revolutionary socialist. He is best-known for the 1848 pamphlet '' The Communist Manifesto'' (written with Friedrich Engels) ...

, and John Maynard Keynes

John Maynard Keynes, 1st Baron Keynes ( ; 5 June 1883 – 21 April 1946), was an English economist and philosopher whose ideas fundamentally changed the theory and practice of macroeconomics and the economic policies of governments. Originall ...

. Petty and Adam Smith shared a worldview that believed in a harmonious natural world. They both saw the benefits of specialisation and the division of labour

The division of labour is the separation of the tasks in any economic system or organisation so that participants may specialise ( specialisation). Individuals, organisations, and nations are endowed with or acquire specialised capabilities, a ...

. Smith said nothing about Petty in ''The Wealth of Nations

''An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations'', usually referred to by its shortened title ''The Wealth of Nations'', is a book by the Scottish people, Scottish economist and moral philosophy, moral philosopher Adam Smith; ...

''. In his published writings, there is nothing apart from a reference in a letter to Lord Shelburne

William Petty Fitzmaurice, 1st Marquess of Lansdowne (2 May 17377 May 1805), known as the Earl of Shelburne between 1761 and 1784, by which title he is generally known to history, was an Anglo-Irish Whig statesman who was the first home secr ...

, one of Petty's aristocratic descendants.

Karl Marx imitated Petty's belief that the total effort put in by the aggregate of ordinary workers represented a far greater contribution to the economy than contemporary ideas recognised. This belief led Petty to conclude that labour ranked as the greatest source of wealth. By contrast, Marx's conclusions were that surplus labour

Surplus labor () is a concept used by Karl Marx in his critique of political economy. It means labor performed in excess of the labor necessary to produce the means of livelihood of the worker ("necessary labor"). The "surplus" in this context mea ...

was the source of all profit

Profit may refer to:

Business and law

* Profit (accounting), the difference between the purchase price and the costs of bringing to market

* Profit (economics), normal profit and economic profit

* Profit (real property), a nonpossessory inter ...

, and that the labourer was alienated from his surplus and thus from society. Marx's high esteem of Adam Smith is mirrored in his consideration of Petty's analysis, testified for by countless quotations in his major work ''Das Kapital

''Capital: A Critique of Political Economy'' (), also known as ''Capital'' or (), is the most significant work by Karl Marx and the cornerstone of Marxian economics, published in three volumes in 1867, 1885, and 1894. The culmination of his ...

''. John Maynard Keynes

John Maynard Keynes, 1st Baron Keynes ( ; 5 June 1883 – 21 April 1946), was an English economist and philosopher whose ideas fundamentally changed the theory and practice of macroeconomics and the economic policies of governments. Originall ...

demonstrated how governments could manage aggregate demand

In economics, aggregate demand (AD) or domestic final demand (DFD) is the total demand for final goods and services in an economy at a given time. It is often called effective demand, though at other times this term is distinguished. This is the ...

to stimulate output and employment, much as Petty had done with simpler examples in the 17th century. Petty's simple £100-through-100-hands multiplier was refined by Keynes and incorporated into his model.

Some consider Petty's achievements a matter of good fortune. Petty was a music professor before being apprenticed to the brilliant Thomas Hobbes

Thomas Hobbes ( ; 5 April 1588 – 4 December 1679) was an English philosopher, best known for his 1651 book ''Leviathan (Hobbes book), Leviathan'', in which he expounds an influential formulation of social contract theory. He is considered t ...

. He arrived upon his laissez-faire view of economics at a time of great opportunity and growth in the expanding British Empire. Laissez-faire policies stood in direct contrast to his supervisor Hobbes's Social Contract

In moral and political philosophy, the social contract is an idea, theory, or model that usually, although not always, concerns the legitimacy of the authority of the state over the individual. Conceptualized in the Age of Enlightenment, it ...

, developed from Hobbes's experiences during the greatest depression in England's history, the General Crisis

The General Crisis is a term used by some historians to describe an alleged period of widespread regional conflict and instability that occurred from the early 17th century to the early 18th century in Europe, and in more recent historiography ...

.

Monument

In 1858Henry Petty-Fitzmaurice, 3rd Marquess of Lansdowne

Henry Petty-Fitzmaurice, 3rd Marquess of Lansdowne (2 July 178031 January 1863), known as Lord Henry Petty from 1784 to 1809, was a British statesman. In a ministerial career spanning nearly half a century, he notably served as Home Secretary a ...

, one of Petty's descendants, erected a memorial and likeness of Petty in Romsey Abbey

Romsey Abbey is the name currently given to a parish church of the Church of England in Romsey, a market town in Hampshire, England. Until the Dissolution of the Monasteries it was the church of a Benedictine Order, Benedictine nunnery. The surv ...

. The text on it reads: "A true patriot and a sound philosopher who, by his powerful intellect, his scientific works and indefatigable industry, became a benefactor to his family and an ornament to his country". A monumental slab on the floor of the south choir aisle of the Abbey reads "HERE LAYES SIR WILLIAM PETY". The third Marquess also erected the Lansdowne Monument on Cherhill Down in Wiltshire.

Publications

* 1647: '' The Advice to Hartlib'' * 1648: '' A Declaration Concerning the newly invented Art of Double Writing'' * 1659: '' Proceedings between Sankey and Petty'' * 1660: '' Reflections upon Ireland'' * 1662: '' A Treatise of Taxes & Contributions'' (later editions: 1667, 1679, 1685, etc.) * ''Political Arithmetic'' posthum. (approx. 1676, pub. 1690) * ''Verbum Sapienti'' posthum. (1664, pub. 1691) * ''Political Anatomy of Ireland'' posthum. (1672, pub. 1691) * ''Quantulumcunque Concerning Money'' ("something, be it ever so small, about money") posthum. (1682, pub. 1695) '' Quantulumcunque'' in: ''The Economic Writings of Sir William Petty'' (vol. 2) (1899). * ''An Essay Concerning the Multiplication of Mankind''. (1682)Notes

References

Sources

* Aspromourgos, Tony (1988) "The life of William Petty in relation to his economics" in ''History of Political Economy 20'': 337–356. * * * * * Hutchison, Terence (1988). "Petty on Policy, Theory and Method," in ''Before Adam Smith: the Emergence of Political Economy 1662–1776''. Basil Blackwell. * * * Routh, Guy (1989) ''The Origin of Economic Ideas''. London: Macmillan. * * Strathern, Paul (2001) - ''Dr Strangelove's Game : a brief history of economic genius''. London : Hamish Hamilton. * (especially section 'Petty's Natural Price', pp. 61–68)External links

Archive for the History of Economic Thought: "William Petty"

* *

Petty FitzMaurice (Lansdowne) family tree

*

National Portrait Gallery National Portrait Gallery may refer to:

* National Portrait Gallery (Australia), in Canberra

* National Portrait Gallery (Sweden), in Mariefred

*National Portrait Gallery (United States), in Washington, D.C.

*National Portrait Gallery, London

...

has five portraits of Sir William PettySearch the collection

Kenmare Journal – A Bridge to the Past.

{{DEFAULTSORT:Petty, William 1623 births 1687 deaths 17th-century English medical doctors 17th-century English male writers 17th-century English economists 17th-century English philosophers People from Romsey Members of the pre-1707 English Parliament for constituencies in Cornwall 17th-century English businesspeople English statisticians Founder fellows of the Royal Society Alumni of the University of Oxford Fellows of Brasenose College, Oxford English surveyors

William

William is a masculine given name of Germanic languages, Germanic origin. It became popular in England after the Norman Conquest, Norman conquest in 1066,All Things William"Meaning & Origin of the Name"/ref> and remained so throughout the Middle ...

Mercantilists

English MPs 1659

Irish MPs 1661–1666

English projectors

Burials at Romsey Abbey

Members of the Parliament of Ireland (pre-1801) for County Kilkenny constituencies