Sir John Fowler, 1st Baronet on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Sir John Fowler, 1st Baronet, KCMG, LLD,

Fowler established a busy practice, working on many railway schemes across the country. He became chief engineer for the

Fowler established a busy practice, working on many railway schemes across the country. He became chief engineer for the

As part of his railway projects, Fowler designed numerous bridges. In the 1860s, he designed

As part of his railway projects, Fowler designed numerous bridges. In the 1860s, he designed

The first trial on the Great Western Railway in October 1861 was a failure. The condensing system leaked, causing the boiler to run dry and pressure to drop, risking a boiler explosion. A second trial on the Metropolitan Railway in 1862 was also a failure, and the fireless engine was abandoned, becoming known as " Fowler's Ghost". The locomotive was sold to Isaac Watt Boulton in 1865; he intended to convert it into a standard engine but it was eventually scrapped.

On opening, the Metropolitan Railway's trains were provided by the Great Western Railway, but these were withdrawn in August 1863. After a period hiring trains from the Great Northern Railway, the Metropolitan Railway introduced its own, Fowler designed, 4-4-0

The first trial on the Great Western Railway in October 1861 was a failure. The condensing system leaked, causing the boiler to run dry and pressure to drop, risking a boiler explosion. A second trial on the Metropolitan Railway in 1862 was also a failure, and the fireless engine was abandoned, becoming known as " Fowler's Ghost". The locomotive was sold to Isaac Watt Boulton in 1865; he intended to convert it into a standard engine but it was eventually scrapped.

On opening, the Metropolitan Railway's trains were provided by the Great Western Railway, but these were withdrawn in August 1863. After a period hiring trains from the Great Northern Railway, the Metropolitan Railway introduced its own, Fowler designed, 4-4-0

Fowler stood unsuccessfully for parliament as a

Fowler stood unsuccessfully for parliament as a

FRSE

Fellowship of the Royal Society of Edinburgh (FRSE) is an award granted to individuals that the Royal Society of Edinburgh, Scotland's national academy of science and Literature, letters, judged to be "eminently distinguished in their subject". ...

(15 July 1817 – 20 November 1898) was an English civil engineer

A civil engineer is a person who practices civil engineering – the application of planning, designing, constructing, maintaining, and operating infrastructure while protecting the public and environmental health, as well as improving existing i ...

specialising in the construction of railways and railway infrastructure. In the 1850s and 1860s, he was engineer for the world's first underground railway, London's Metropolitan Railway

The Metropolitan Railway (also known as the Met) was a passenger and goods railway that served London from 1863 to 1933, its main line heading north-west from the capital's financial heart in the City to what were to become the Middlesex su ...

, built by the "cut-and-cover

A tunnel is an underground or undersea passageway. It is dug through surrounding soil, earth or rock, or laid under water, and is usually completely enclosed except for the two Portal (architecture), portals common at each end, though ther ...

" method under city streets. In the 1880s, he was chief engineer for the Forth Bridge, which opened in 1890. Fowler's was a long and eminent career, spanning most of the 19th century's railway expansion, and he was engineer, adviser or consultant to many British and foreign railway companies and governments. He was the youngest president of the Institution of Civil Engineers

The Institution of Civil Engineers (ICE) is an independent professional association for civil engineers and a Charitable organization, charitable body in the United Kingdom. Based in London, ICE has over 92,000 members, of whom three-quarters ar ...

, between 1865 and 1867, and his major works represent a lasting legacy of Victorian engineering.

Early life

Fowler was born in Wadsley,Sheffield

Sheffield is a city in South Yorkshire, England, situated south of Leeds and east of Manchester. The city is the administrative centre of the City of Sheffield. It is historically part of the West Riding of Yorkshire and some of its so ...

, Yorkshire, England, to land surveyor John Fowler and his wife Elizabeth (née Swann). He was educated privately at Whitley Hall near Ecclesfield

Ecclesfield is a village and civil parish in the City of Sheffield, South Yorkshire, England, approximately 6 miles (9 km) north of Sheffield City Centre. Ecclesfield civil parish had a population of 32,073 at the 2011 Census. Ecclesfiel ...

. He trained under John Towlerton Leather, engineer of the Sheffield waterworks, and with Leather's uncle, George Leather, on the Aire and Calder Navigation

The Aire and Calder Navigation is the River engineering#Canalization of rivers, canalised section of the River Aire, Rivers Aire and River Calder, West Yorkshire, Calder in West Yorkshire, England. The first improvements to the rivers above Kn ...

and on railway surveys. From 1837 he worked for John Urpeth Rastrick on railway projects including the London and Brighton Railway and the unbuilt West Cumberland and Furness Railway. He then worked again for George Leather as resident engineer on the Stockton and Hartlepool Railway and was appointed engineer to the railway when it opened in 1841. Fowler initially established a practice as a consulting engineer in the Yorkshire and Lincolnshire area, but, a heavy workload led him to move to London in 1844. He became a member of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers

The Institution of Mechanical Engineers (IMechE) is an independent professional association and learned society headquartered in London, United Kingdom, that represents mechanical engineers and the engineering profession. With over 110,000 member ...

in 1847, the year the Institution was founded, and a member of the Institution of Civil Engineers

The Institution of Civil Engineers (ICE) is an independent professional association for civil engineers and a Charitable organization, charitable body in the United Kingdom. Based in London, ICE has over 92,000 members, of whom three-quarters ar ...

in 1849. On 2 July 1850 he married Elizabeth Broadbent (died 19 November 1901), daughter of J. Broadbent of Manchester. The couple had four sons.

Railways

Fowler established a busy practice, working on many railway schemes across the country. He became chief engineer for the

Fowler established a busy practice, working on many railway schemes across the country. He became chief engineer for the Manchester, Sheffield and Lincolnshire Railway

The Manchester, Sheffield and Lincolnshire Railway (MS&LR) was formed in 1847 when the Sheffield, Ashton-under-Lyne and Manchester Railway joined with authorised but unbuilt railway companies, forming a proposed network from Manchester to Grims ...

and was engineer of the East Lincolnshire Railway

The East Lincolnshire Railway was a main line railway linking the towns of Boston, Lincolnshire, Boston, Alford, Lincolnshire, Alford, Louth, Lincolnshire, Louth and Grimsby in Lincolnshire, England. It opened in 1848. The ELR ''Company'' had l ...

, the Oxford, Worcester and Wolverhampton Railway and the Severn Valley Railway

The Severn Valley Railway is a standard gauge, standard-gauge heritage railway in Shropshire and Worcestershire, England. The single-track line runs from Bridgnorth to Kidderminster, calling at four intermediate stations and three request stop ...

. In 1853, he became chief engineer of the Metropolitan Railway

The Metropolitan Railway (also known as the Met) was a passenger and goods railway that served London from 1863 to 1933, its main line heading north-west from the capital's financial heart in the City to what were to become the Middlesex su ...

in London, the world's first underground railway. Constructed in shallow "cut-and-cover" trenches beneath roads, the line opened between Paddington

Paddington is an area in the City of Westminster, in central London, England. A medieval parish then a metropolitan borough of the County of London, it was integrated with Westminster and Greater London in 1965. Paddington station, designed b ...

and Farringdon in 1863. Fowler was also engineer for the associated District Railway

The Metropolitan District Railway, also known as the District Railway, was a passenger railway that served London, England, from 1868 to 1933. Established in 1864 to complete an " inner circle" of lines connecting railway termini in London, the ...

and the Hammersmith and City Railway. Today these railways form the majority of the London Underground

The London Underground (also known simply as the Underground or as the Tube) is a rapid transit system serving Greater London and some parts of the adjacent home counties of Buckinghamshire, Essex and Hertfordshire in England.

The Undergro ...

's Circle line. For his work on the Metropolitan Railway Fowler was paid the great sum of £152,000 (£ today), with £157,000 (£ today), from the District Railway. Although some of this would have been passed on to staff and contractors, Sir Edward Watkin, chairman of the Metropolitan Railway from 1872, complained that "No engineer in the world was so highly paid."

Other railways that Fowler consulted for were the London Tilbury and Southend Railway, the Great Northern Railway, the Highland Railway and the Cheshire Lines Railway. Following the death of Isambard Kingdom Brunel

Isambard Kingdom Brunel ( ; 9 April 1806 – 15 September 1859) was an English civil engineer and mechanical engineer who is considered "one of the most ingenious and prolific figures in engineering history", "one of the 19th-century engi ...

in 1859, Fowler was retained by the Great Western Railway

The Great Western Railway (GWR) was a History of rail transport in Great Britain, British railway company that linked London with the southwest, west and West Midlands (region), West Midlands of England and most of Wales. It was founded in 1833, ...

. His various appointments involved him in the design of Victoria station in London, Sheffield Victoria station, St Enoch station in Glasgow, Liverpool Central station and Manchester Central station. The latter station's wide train shed roof was the second widest unsupported iron arch in Britain after the roof of St Pancras railway station

St Pancras railway station (), officially known since 2007 as London St Pancras International, is a major central London railway terminus on Euston Road in the London Borough of Camden. It is the terminus for Eurostar services from Belgium, F ...

.

Fowler's consulting work extended beyond Britain including railway and engineering projects in Algeria, Australia, Belgium, Egypt, France, Germany, Portugal and the United States. He travelled to Egypt for the first time in 1869 and worked on a number of, mostly unrealised, schemes for the Khedive

Khedive ( ; ; ) was an honorific title of Classical Persian origin used for the sultans and grand viziers of the Ottoman Empire, but most famously for the Khedive of Egypt, viceroy of Egypt from 1805 to 1914.Adam Mestyan"Khedive" ''Encyclopaedi ...

, including a railway to Khartoum

Khartoum or Khartum is the capital city of Sudan as well as Khartoum State. With an estimated population of 7.1 million people, Greater Khartoum is the largest urban area in Sudan.

Khartoum is located at the confluence of the White Nile – flo ...

in Sudan

Sudan, officially the Republic of the Sudan, is a country in Northeast Africa. It borders the Central African Republic to the southwest, Chad to the west, Libya to the northwest, Egypt to the north, the Red Sea to the east, Eritrea and Ethiopi ...

which was planned in 1875 but not completed until after his death. In 1870 he provided advice to an Indian Government

The Government of India (ISO: Bhārata Sarakāra, legally the Union Government or Union of India or the Central Government) is the national authority of the Republic of India, located in South Asia, consisting of 36 states and union territor ...

inquiry on railway gauges where he recommended a narrow gauge of for light railways. He visited Australia in 1886, where he made some remarks on the break of gauge

With railways, a break of gauge occurs where a line of one track gauge (the distance between the rails, or between the wheels of trains designed to run on those rails) meets a line of a different gauge. Trains and railroad car, rolling stock g ...

difficulty. Later in his career, he was also a consultant with his partner Benjamin Baker and with James Henry Greathead on two of London's first tube railways, the City and South London Railway

The City and South London Railway (C&SLR) was the first successful deep-level underground "tube" railway in the world, and the first major railway to use Railway electrification in Great Britain, electric traction. The railway was originally i ...

and the Central London Railway.

Bridges

As part of his railway projects, Fowler designed numerous bridges. In the 1860s, he designed

As part of his railway projects, Fowler designed numerous bridges. In the 1860s, he designed Grosvenor Bridge

Grosvenor Bridge, originally known as, and alternatively called Victoria Railway Bridge, is a railway bridge over the River Thames in London, between Vauxhall Bridge and Chelsea Bridge. Originally constructed in 1860, and widened in 1865 and ...

, the first railway bridge over the River Thames

The River Thames ( ), known alternatively in parts as the The Isis, River Isis, is a river that flows through southern England including London. At , it is the longest river entirely in England and the Longest rivers of the United Kingdom, s ...

, and the 13-arch Dollis Brook Viaduct for the Edgware, Highgate and London Railway.

He is credited with the design of the Victoria Bridge at Upper Arley

Upper Arley () is a village and civil parish near Kidderminster in the Wyre Forest (district), Wyre Forest District of Worcestershire, England. Historically part of Staffordshire, the village had a population of 741 at the 2011 census.

Amen ...

, Worcestershire

Worcestershire ( , ; written abbreviation: Worcs) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in the West Midlands (region), West Midlands of England. It is bordered by Shropshire, Staffordshire, and the West Midlands (county), West ...

, constructed between 1859 and 1861, and the near identical Albert Edward Bridge at Coalbrookdale

Coalbrookdale is a town in the Ironbridge Gorge and the Telford and Wrekin borough of Shropshire, England, containing a settlement of great significance in the history of iron ore smelting. It lies within the civil parish called The Gorge, Shro ...

, Shropshire

Shropshire (; abbreviated SalopAlso used officially as the name of the county from 1974–1980. The demonym for inhabitants of the county "Salopian" derives from this name.) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in the West M ...

built from 1863 to 1864. Both remain in use today carrying railway lines across the River Severn

The River Severn (, ), at long, is the longest river in Great Britain. It is also the river with the most voluminous flow of water by far in all of England and Wales, with an average flow rate of at Apperley, Gloucestershire. It rises in t ...

.

Following the collapse of Sir Thomas Bouch's Tay Bridge in 1879, Fowler, William Henry Barlow and Thomas Elliot Harrison were appointed in 1881 to a commission to review Bouch's design for the Forth Bridge. The commission recommended a steel cantilever bridge

A cantilever bridge is a bridge built using structures that project horizontally into space, supported on only one end (called cantilevers). For small footbridges, the cantilevers may be simple beam (structure), beams; however, large cantilever ...

designed by Fowler and Benjamin Baker, which was constructed between 1883 and 1890.

Locomotives

To avoid problems with smoke and steam overwhelming staff and passengers on the covered sections of the Metropolitan Railway, Fowler proposed afireless locomotive

A fireless locomotive is a type of locomotive which uses reciprocating engines powered from a reservoir of compressed air or steam, which is filled at intervals from an external source. They offer advantages over conventional steam locomotives of ...

. The locomotive was built by Robert Stephenson and Company

Robert Stephenson and Company was a locomotive manufacturing company founded in 1823 in Forth Street, Newcastle upon Tyne in England. It was the first company in the world created specifically to build Steam locomotive, railway engines.

Famou ...

and was a broad gauge

A broad-gauge railway is a railway with a track gauge (the distance between the rails) broader than the used by standard-gauge railways.

Broad gauge of , more known as Russian gauge, is the dominant track gauge in former Soviet Union countries ...

2-4-0 tender engine. The boiler had a normal firebox connected to a large combustion chamber

A combustion chamber is part of an internal combustion engine in which the air–fuel ratio, fuel/air mix is burned. For steam engines, the term has also been used for an extension of the Firebox (steam engine), firebox which is used to allow a mo ...

containing fire brick

A fire brick, firebrick, fireclay brick, or refractory brick is a block of ceramic material used in lining furnaces, kilns, fireboxes, and fireplaces. Made of primarily oxide materials like silica and alumina in varying ratios, these insulati ...

s which were to act as a heat reservoir. The combustion chamber was linked to the smokebox

A smokebox is one of the major basic parts of a steam locomotive exhaust system. Smoke and hot gases pass from the firebox through tubes where they pass heat to the surrounding water in the boiler. The smoke then enters the smokebox, and is ...

through a set of very short firetubes. Exhaust steam was re-condensed instead of escaping and fed back to the boiler. The locomotive was intended to operate conventionally in the open, but in tunnels dampers would be closed and steam would be generated firelessly, using the stored heat from the fire bricks.

The first trial on the Great Western Railway in October 1861 was a failure. The condensing system leaked, causing the boiler to run dry and pressure to drop, risking a boiler explosion. A second trial on the Metropolitan Railway in 1862 was also a failure, and the fireless engine was abandoned, becoming known as " Fowler's Ghost". The locomotive was sold to Isaac Watt Boulton in 1865; he intended to convert it into a standard engine but it was eventually scrapped.

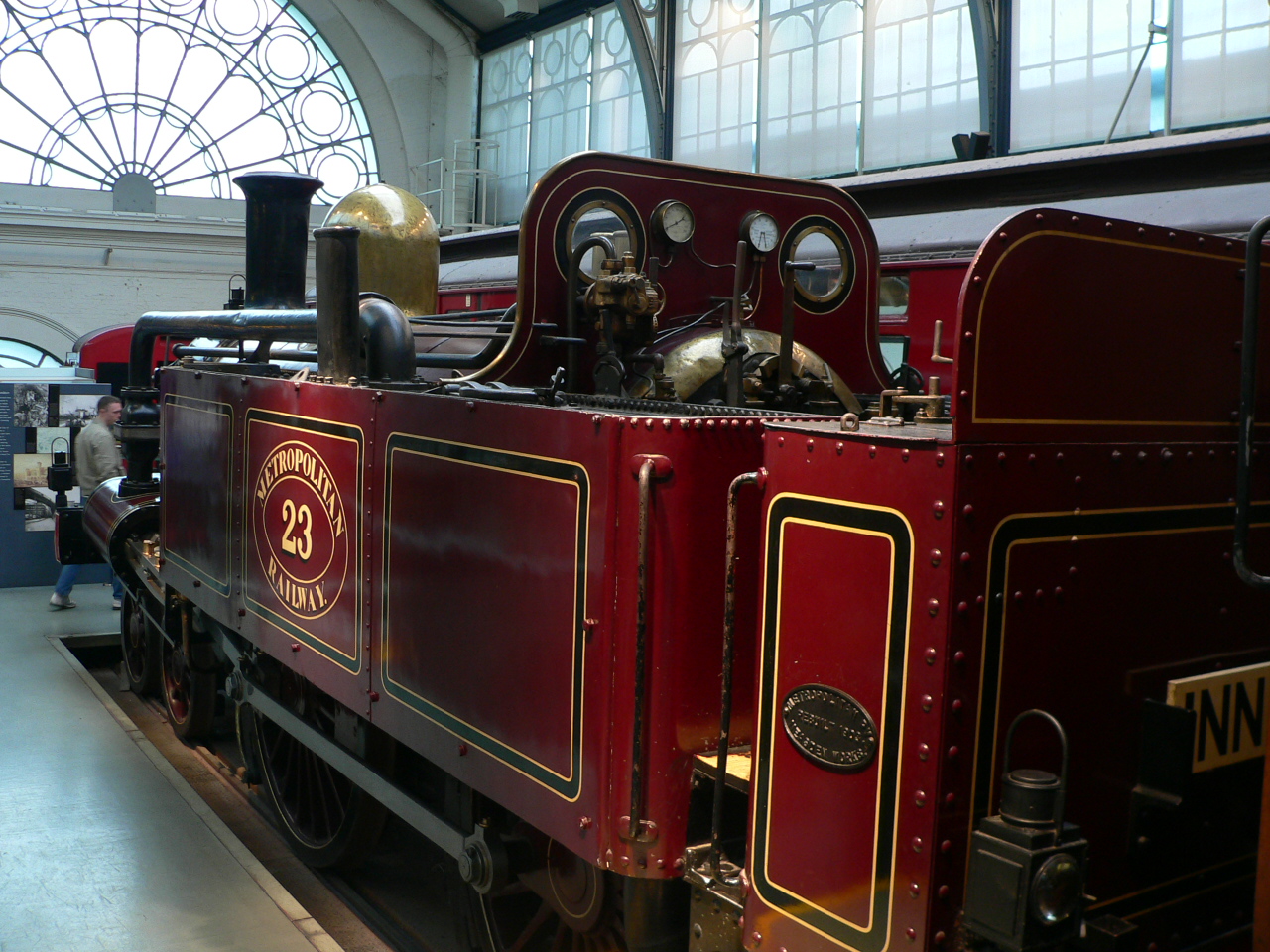

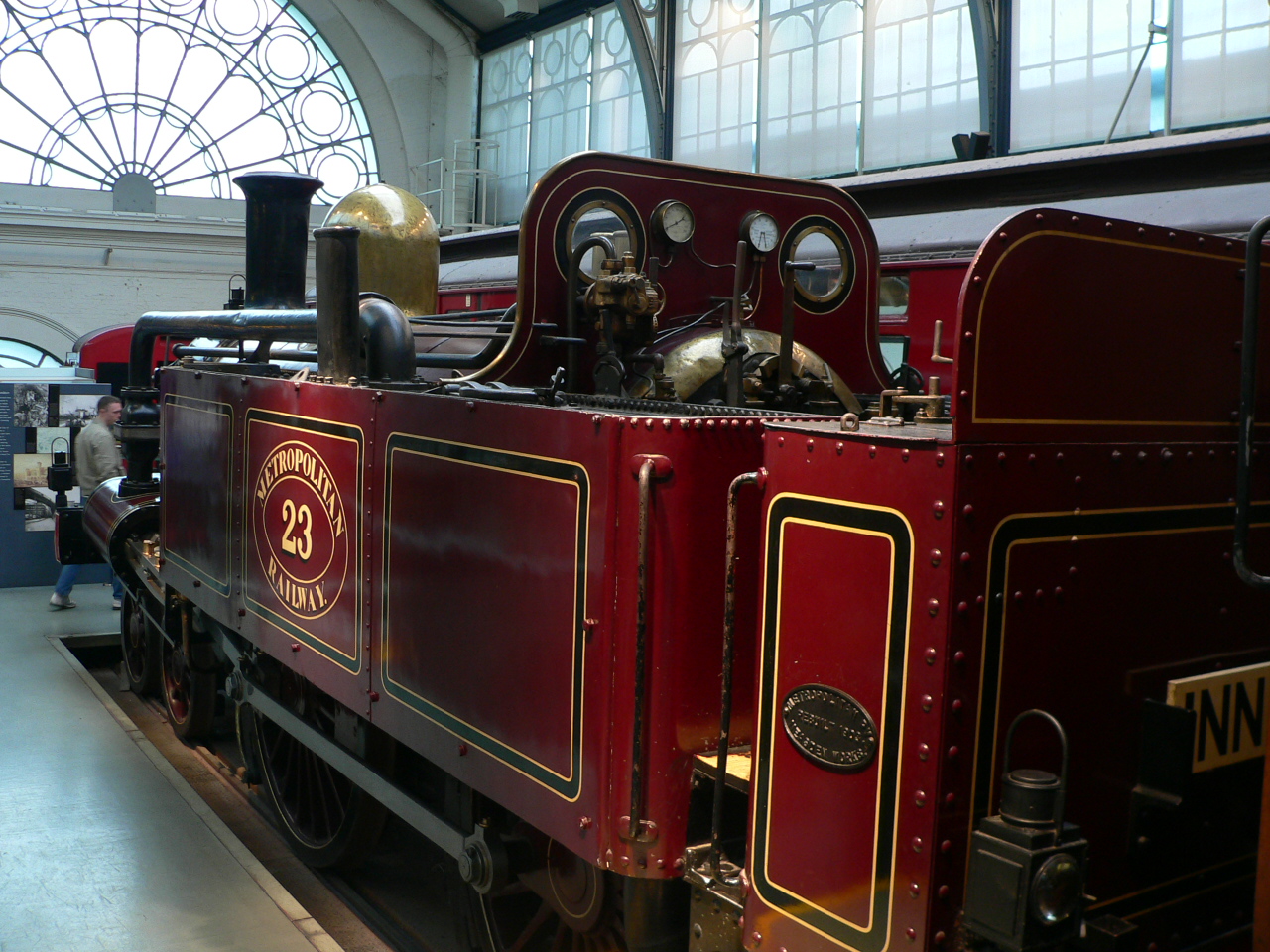

On opening, the Metropolitan Railway's trains were provided by the Great Western Railway, but these were withdrawn in August 1863. After a period hiring trains from the Great Northern Railway, the Metropolitan Railway introduced its own, Fowler designed, 4-4-0

The first trial on the Great Western Railway in October 1861 was a failure. The condensing system leaked, causing the boiler to run dry and pressure to drop, risking a boiler explosion. A second trial on the Metropolitan Railway in 1862 was also a failure, and the fireless engine was abandoned, becoming known as " Fowler's Ghost". The locomotive was sold to Isaac Watt Boulton in 1865; he intended to convert it into a standard engine but it was eventually scrapped.

On opening, the Metropolitan Railway's trains were provided by the Great Western Railway, but these were withdrawn in August 1863. After a period hiring trains from the Great Northern Railway, the Metropolitan Railway introduced its own, Fowler designed, 4-4-0 tank engine

A tank locomotive is a steam locomotive which carries its water in one or more on-board water tanks, instead of a more traditional tender. Most tank engines also have bunkers (or fuel tanks) to hold fuel; in a tender-tank locomotive a tender h ...

s in 1864. The design of condensing steam locomotives, known as the A class and, with minor updates, the B class, was so successful that the Metropolitan and District Railways eventually had 120 of the engines in use and they remained in operation until electrification of the lines in the 1900s. While they were not fireless, the locomotives condensed their steam, and burnt coke or smokeless coal to reduce smoke emitted.

Other activities and professional recognition

Fowler stood unsuccessfully for parliament as a

Fowler stood unsuccessfully for parliament as a Conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy and ideology that seeks to promote and preserve traditional institutions, customs, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civiliza ...

candidate in 1880 and 1885. His standing within the engineering profession was very high, to the extent that he was elected president of the Institution of Civil Engineers for the period 1866–67, its youngest president. Through his position in the Institution and through his own practice, he led the development of training for engineers.

In 1865/67, he purchased the adjacent estates of Braemore and Inverbroom, near Ullapool in Ross-shire

Ross-shire (; ), or the County of Ross, was a county in the Scottish Highlands. It bordered Sutherland to the north and Inverness-shire to the south, as well as having a complex border with Cromartyshire, a county consisting of numerous enc ...

, Scotland, comprising 44,000 acres and becoming one of the premier Deer Forests (sporting estates) of the Highlands. He built the substantial Braemore House (since demolished), where he entertained at the highest levels of politics and society. He developed a hydro-electric scheme, fed from the artificial Home Loch, planted extensive woodlands on the steep valley sides, and created 12 km of recreational walks through them, including suspension footbridges over the Corrieshalloch and Strone Gorges (the former now an NTS property). He also developed a network of stalkerpaths. He was appointed a Justice of the Peace and a Deputy Lieutenant of the county. Lady Fowler here became a noted botanist.

He listed his recreations in ''Who's Who

A Who's Who (or Who Is Who) is a reference work consisting of biographical entries of notable people in a particular field. The oldest and best-known is the annual publication ''Who's Who (UK), Who's Who'', a reference work on contemporary promin ...

'' as yachting and deerstalking and was a member of the Carlton Club

The Carlton Club is a private members' club in the St James's area of London, England. It was the original home of the Conservative Party before the creation of Conservative Central Office. Membership of the club is by nomination and elect ...

, St Stephen's Club

St Stephen's Club was a private member's club in City of Westminster, Westminster, London, founded in 1870.

St Stephen's was originally on the corner of Bridge Street and the Victoria Embankment, Embankment, in London SW1, now the location of Por ...

, the Conservative Club

The Conservative Club was a London gentlemen's club, now dissolved, which was established in 1840. In 1950 it merged with the Bath Club, and was disbanded in 1981. From 1845 until 1959, the club occupied a building at 74 St James's Street where ...

and the Royal Yacht Squadron

The Royal Yacht Squadron (RYS) is a British yacht club. Its clubhouse is Cowes Castle on the Isle of Wight in the United Kingdom. Member yachts are given the suffix RYS to their names, and are permitted (with the appropriate warrant) to we ...

. He was also President of the Egyptian Exploration Fund. In 1885 he was made a Knight Commander of the Order of Saint Michael and Saint George as thanks from the government for allowing the use of maps of the Upper Nile valley he had had made when working on the Khedive's projects. They were the most accurate survey of the area and were used in the British Relief of Khartoum.

In 1887 he was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society of Edinburgh

The Royal Society of Edinburgh (RSE) is Scotland's national academy of science and letters. It is a registered charity that operates on a wholly independent and non-partisan basis and provides public benefit throughout Scotland. It was establis ...

.

Following the successful completion of the Forth Bridge in 1890, Fowler was created Baronet Fowler of Braemor. Along with Benjamin Baker, he received an honorary degree of Doctor of Law

A Doctor of Laws (LL.D.) is a doctoral degree in legal studies. The abbreviation LL.D. stands for ''Legum Doctor'', with the double “L” in the abbreviation referring to the early practice in the University of Cambridge to teach both canon law ...

s from the University of Edinburgh

The University of Edinburgh (, ; abbreviated as ''Edin.'' in Post-nominal letters, post-nominals) is a Public university, public research university based in Edinburgh, Scotland. Founded by the City of Edinburgh Council, town council under th ...

in 1890 for his engineering of the bridge. In 1892, the Poncelet Prize was doubled and awarded jointly to Baker and Fowler.

Fowler died in Bournemouth

Bournemouth ( ) is a coastal resort town in the Bournemouth, Christchurch and Poole unitary authority area, in the ceremonial county of Dorset, England. At the 2021 census, the built-up area had a population of 196,455, making it the largest ...

, Hampshire

Hampshire (, ; abbreviated to Hants.) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South East England. It is bordered by Berkshire to the north, Surrey and West Sussex to the east, the Isle of Wight across the Solent to the south, ...

, at the age of 81 and is buried in Brompton Cemetery

Brompton Cemetery (originally the West of London and Westminster Cemetery) is since 1852 the first (and only) London cemetery to be Crown Estate, Crown property, managed by The Royal Parks, in West Brompton in the Royal Borough of Kensington a ...

, London. He was succeeded in the baronetcy by his son John Arthur Fowler, 2nd Baronet (died 25 March 1899). The baronetcy became extinct in 1933 on the death of Reverend Montague Fowler, 4th Baronet, the first baronet's third son.

See also

* Fowler baronetsNotes

References

{{DEFAULTSORT:Fowler, John 1817 births 1898 deaths British railway pioneers History of Sheffield People from Wadsley Knights Commander of the Order of St Michael and St George British bridge engineers Engineers from Yorkshire Burials at Brompton Cemetery Baronets in the Baronetage of the United Kingdom Metropolitan Railway people Presidents of the Institution of Civil Engineers Presidents of the Smeatonian Society of Civil Engineers People associated with transport in London Transport design in London 19th-century English people 19th-century English businesspeople