Shushan Purim on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Purim (; , ) is a

The

The

The primary source relating to the origin of Purim is the

The primary source relating to the origin of Purim is the

The 1st-century CE historian

The 1st-century CE historian

The first religious ceremony which is ordained for the celebration of Purim is the reading of the Book of Esther (the "Megillah") in the synagogue, a regulation which is ascribed in the Talmud (Megillah 2a) to the Sages of the

The first religious ceremony which is ordained for the celebration of Purim is the reading of the Book of Esther (the "Megillah") in the synagogue, a regulation which is ascribed in the Talmud (Megillah 2a) to the Sages of the

, the story of the attack on the Jews by

When Haman's name is read out loud during the public chanting of the Megillah in the synagogue, which occurs 54 times, the congregation engages in noise-making to blot out his name. The practice can be traced back to the

When Haman's name is read out loud during the public chanting of the Megillah in the synagogue, which occurs 54 times, the congregation engages in noise-making to blot out his name. The practice can be traced back to the

The Book of Esther prescribes "the sending of portions one man to another, and gifts to the poor". According to

The Book of Esther prescribes "the sending of portions one man to another, and gifts to the poor". According to

On Purim day, a festive meal called the is held.

There is a longstanding custom of drinking wine at the feast. The Talmud (b. Megillah 7b) records that " Rava said: A person is obligated to become intoxicated on Purim, until they cannot distinguish between 'Blessed be Mordecai' and 'Cursed be Haman'". Several interpretations arose among the late medieval authorities, although in general the classical sources are unanimous in rejecting intoxicated excess; only beginning with the Hasidic masters was drunkenness occasionally endorsed.

On Purim day, a festive meal called the is held.

There is a longstanding custom of drinking wine at the feast. The Talmud (b. Megillah 7b) records that " Rava said: A person is obligated to become intoxicated on Purim, until they cannot distinguish between 'Blessed be Mordecai' and 'Cursed be Haman'". Several interpretations arose among the late medieval authorities, although in general the classical sources are unanimous in rejecting intoxicated excess; only beginning with the Hasidic masters was drunkenness occasionally endorsed.

The custom of masquerading in costumes and the wearing of masks probably originated among the Italian Jews at the end of the 15th century. The concept was possibly influenced by the Roman

The custom of masquerading in costumes and the wearing of masks probably originated among the Italian Jews at the end of the 15th century. The concept was possibly influenced by the Roman

On Purim,

On Purim,

Israeli Ministry Warns of ‘Panic-Inducing’ Purim Costumes

, '' JNS'', February 25, 2024

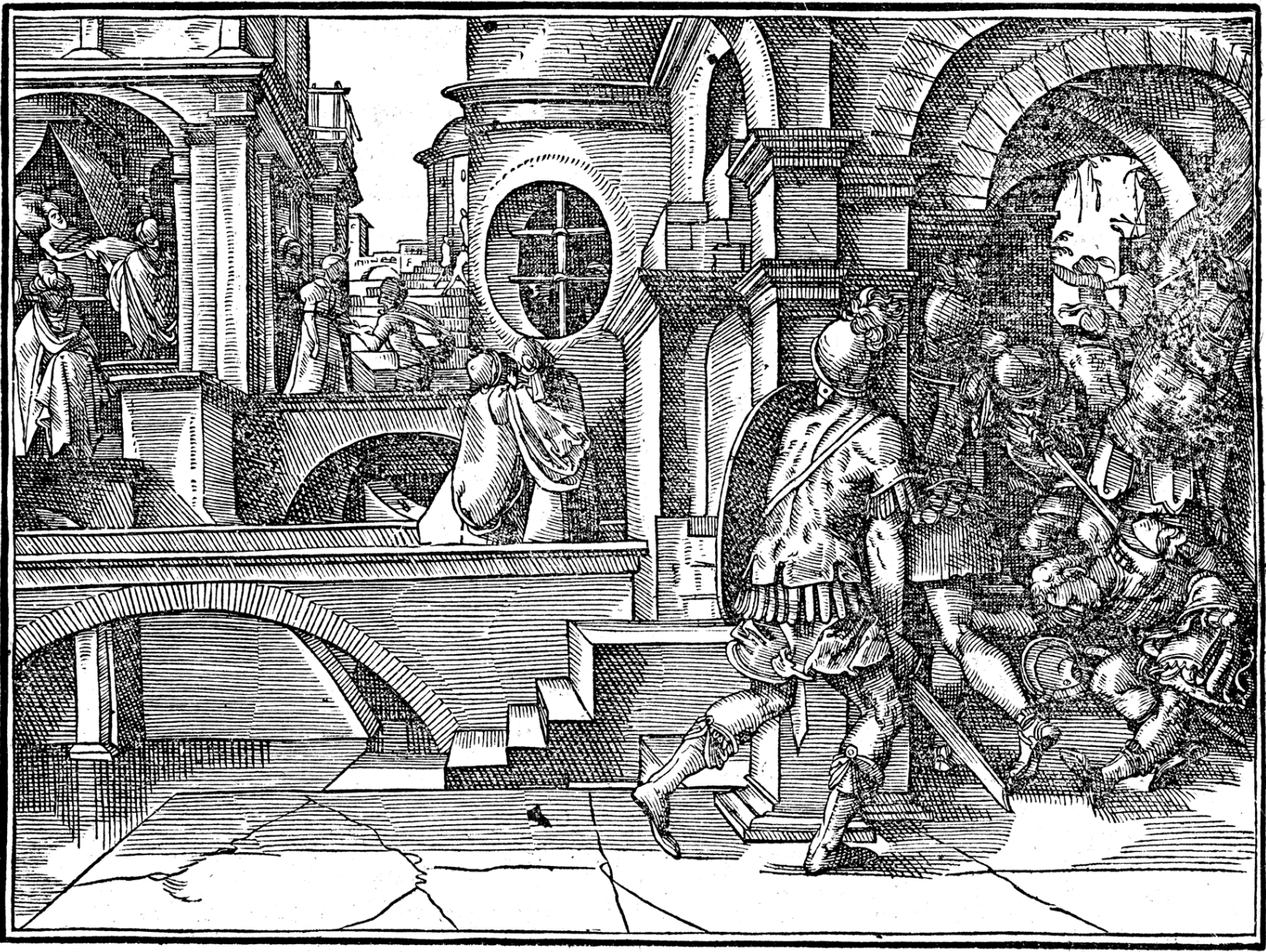

File:Purim woodcut.png, alt=, Purim (1657 engraving)

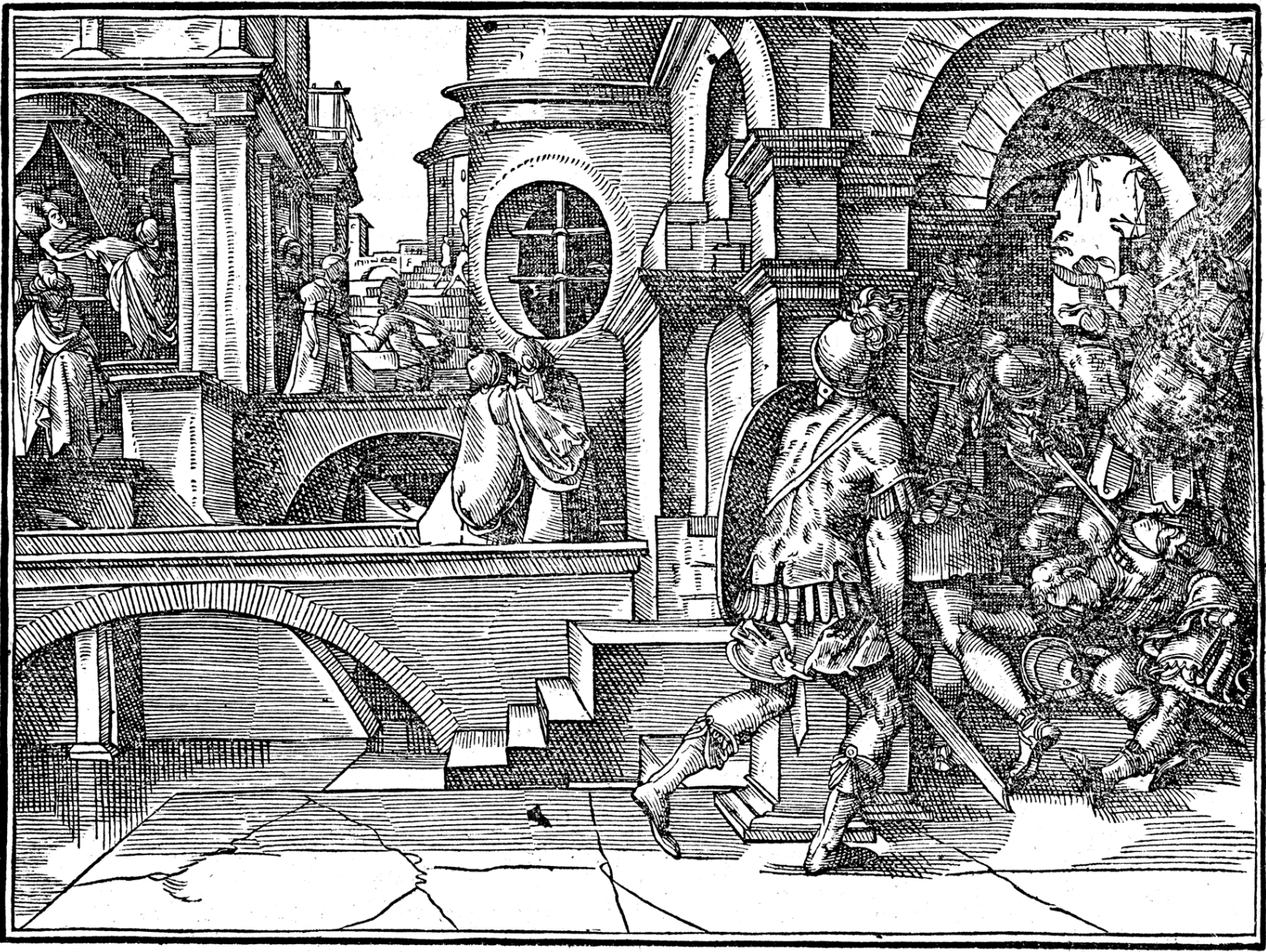

File:Purim woodcut 2.png, alt=, Purim (1699 engraving)

File:Me'ah Berachot6.jpg, alt=, 18th-century manuscript of the prayer of Al HaNissim on the miracles of Purim

File:Megillah.png, alt=, 1740 illumination of an Ashkenazic megillah reading. One man reads while another follows along and a child waves a noise-maker.

File:Purim, woodcut, sefer menhagim.jpg, alt=, Purim woodcut (1741)

File:Feast of lots.jpg, alt=, Megillah reading (1764)

File:FrozenPurim.jpg, alt=, '' Frozen''-themed Megillah reading (2014)

File:Isaac and Michal Herzog in Megillah reading event at the Ahavat Tzion Synagogue in Beit Shemesh, March 2022 (GPOABG1 13).jpg, alt=,

Purim Resources

* Yeshiv

Laws, articles and Q&A on Purim

* Peninei Halakh

The month of Adar and the holiday of Purim, minhagim (customs) and halachot (laws)

by Rabbi

Purim Resources

* The United Synagogue of Conservative Judais

Purim Resources

*

Purim celebrations in the IDF, Exhibition in the IDF&defense establishment archives

{{Authority control Judaism and alcohol Adar observances Masquerade ceremonies Book of Esther

Jewish holiday

Jewish holidays, also known as Jewish festivals or ''Yamim Tovim'' (, or singular , in transliterated Hebrew []), are holidays observed by Jews throughout the Hebrew calendar.This article focuses on practices of mainstream Rabbinic Judaism. ...

that commemorates the saving of the Jews, Jewish people from Genocide, annihilation at the hands of an official of the Achaemenid Empire

The Achaemenid Empire or Achaemenian Empire, also known as the Persian Empire or First Persian Empire (; , , ), was an Iranian peoples, Iranian empire founded by Cyrus the Great of the Achaemenid dynasty in 550 BC. Based in modern-day Iran, i ...

named Haman

Haman ( ; also known as Haman the Agagite) is the main antagonist in the Book of Esther, who according to the Hebrew Bible was an official in the court of the Achaemenid Empire, Persian empire under King Ahasuerus#Book of Esther, Ahasuerus, comm ...

, as it is recounted in the Book of Esther

The Book of Esther (; ; ), also known in Hebrew language, Hebrew as "the Scroll" ("the wikt:מגילה, Megillah"), is a book in the third section (, "Writings") of the Hebrew Bible. It is one of the Five Megillot, Five Scrolls () in the Hebr ...

(usually dated to the late-5th or 4th centuries BCE).

Haman was the royal vizier to the Persian king Ahasuerus

Ahasuerus ( ; , commonly ''Achashverosh''; , in the Septuagint; in the Vulgate) is a name applied in the Hebrew Bible to three rulers of Ancient Persia and to a Babylonian official (or Median king) first appearing in the Tanakh in the Book of ...

(Xerxes I

Xerxes I ( – August 465 BC), commonly known as Xerxes the Great, was a List of monarchs of Persia, Persian ruler who served as the fourth King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire, reigning from 486 BC until his assassination in 465 BC. He was ...

or Artaxerxes I

Artaxerxes I (, ; ) was the fifth King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire, from 465 to December 424 BC. He was the third son of Xerxes I.

In Greek sources he is also surnamed "Long-handed" ( ''Makrókheir''; ), allegedly because his ri ...

; and in Old Persian

Old Persian is one of two directly attested Old Iranian languages (the other being Avestan) and is the ancestor of Middle Persian (the language of the Sasanian Empire). Like other Old Iranian languages, it was known to its native speakers as (I ...

, respectively). His plans were foiled by Mordecai

Mordecai (; also Mordechai; , IPA: ) is one of the main personalities in the Book of Esther in the Hebrew Bible. He is the cousin and guardian of Esther, who became queen of Persia under the reign of Ahasuerus (Xerxes I). Mordecai's loyalty and ...

of the tribe of Benjamin

According to the Torah, the Tribe of Benjamin () was one of the Twelve Tribes of Israel. The tribe was descended from Benjamin, the youngest son of the Patriarchs (Bible), patriarch Jacob (later given the name Israel) and his wife Rachel. In the ...

, who previously to that warned the king from an assassination attempt and thus saving his life, and Esther

Esther (; ), originally Hadassah (; ), is the eponymous heroine of the Book of Esther in the Hebrew Bible. According to the biblical narrative, which is set in the Achaemenid Empire, the Persian king Ahasuerus falls in love with Esther and ma ...

, Mordecai's cousin and adopted daughter who had become queen of Persia after her marriage to Ahasuerus. The day of deliverance became a day of feasting and rejoicing among Jews.

According to the Scroll of Esther

The Book of Esther (; ; ), also known in Hebrew as "the Scroll" ("the Megillah"), is a book in the third section (, "Writings") of the Hebrew Bible. It is one of the Five Scrolls () in the Hebrew Bible and later became part of the Christian ...

, "they should make them days of feasting and gladness, and of sending portions one to another, and gifts to the poor". Purim is celebrated among Jews by:

*Exchanging gifts of food and drink, known as

* Donating charity to the poor, known as

*Eating a celebratory meal with alcoholic beverages, known as or "Mishteh"

*Public recitation of the Scroll of Esther ( ), or "reading of the Megillah", usually in synagogue

*Reciting additions to the daily prayers and the grace after meals, known as

*Applying henna

Henna is a reddish dye prepared from the dried and powdered leaves of the henna tree. It has been used since at least the ancient Egyptian period as a hair and body dye, notably in the temporary body art of mehndi (or "henna tattoo") resulti ...

(Sephardic

Sephardic Jews, also known as Sephardi Jews or Sephardim, and rarely as Iberian Peninsular Jews, are a Jewish diaspora population associated with the historic Jewish communities of the Iberian Peninsula (Spain and Portugal) and their descendant ...

and Mizrahi Jews)

Other customs include wearing masks and costumes, public celebrations and parades (), eating (), and drinking wine

Wine is an alcoholic drink made from Fermentation in winemaking, fermented fruit. Yeast in winemaking, Yeast consumes the sugar in the fruit and converts it to ethanol and carbon dioxide, releasing heat in the process. Wine is most often made f ...

.

According to the Hebrew calendar

The Hebrew calendar (), also called the Jewish calendar, is a lunisolar calendar used today for Jewish religious observance and as an official calendar of Israel. It determines the dates of Jewish holidays and other rituals, such as '' yahrze ...

, Purim is celebrated annually on the 14th day of the Hebrew month of Adar

Adar (Hebrew: , ; from Akkadian ''adaru'') is the sixth month of the civil year and the twelfth month of the religious year on the Hebrew calendar, roughly corresponding to the month of March in the Gregorian calendar. It is a month of 29 days. ...

(and it is celebrated in Adar II in Hebrew leap years, which occur 7 times in every 19 years), the day following the victory of the Jews over their enemies, the 13th of Adar, a date now observed in most years with the fast of Esther.

In cities that were protected by a surrounding wall at the time of Joshua

Joshua ( ), also known as Yehoshua ( ''Yəhōšuaʿ'', Tiberian Hebrew, Tiberian: ''Yŏhōšuaʿ,'' Literal translation, lit. 'Yahweh is salvation'), Jehoshua, or Josue, functioned as Moses' assistant in the books of Book of Exodus, Exodus and ...

, Purim is celebrated on the 15th of the month of Adar on what is known as , since fighting in the walled city of Shushan continued through the 14th day of Adar

Adar (Hebrew: , ; from Akkadian ''adaru'') is the sixth month of the civil year and the twelfth month of the religious year on the Hebrew calendar, roughly corresponding to the month of March in the Gregorian calendar. It is a month of 29 days. ...

. Today, only in Jerusalem

Jerusalem is a city in the Southern Levant, on a plateau in the Judaean Mountains between the Mediterranean Sea, Mediterranean and the Dead Sea. It is one of the List of oldest continuously inhabited cities, oldest cities in the world, and ...

is Purim observed on the 15th, and in several other biblical settlements (such as Hebron

Hebron (; , or ; , ) is a Palestinian city in the southern West Bank, south of Jerusalem. Hebron is capital of the Hebron Governorate, the largest Governorates of Palestine, governorate in the West Bank. With a population of 201,063 in ...

and Shilo) it is celebrated on both dates because of doubts regarding their status as cities surrounded by a wall since the days of Joshua. Some also celebrate both in Prague

Prague ( ; ) is the capital and List of cities and towns in the Czech Republic, largest city of the Czech Republic and the historical capital of Bohemia. Prague, located on the Vltava River, has a population of about 1.4 million, while its P ...

and Baghdad

Baghdad ( or ; , ) is the capital and List of largest cities of Iraq, largest city of Iraq, located along the Tigris in the central part of the country. With a population exceeding 7 million, it ranks among the List of largest cities in the A ...

.

Name

''Purim'' is the plural of the Hebrew word (loan from Akkadian ''puru'') meaning " lot". Its use as the name of this festival comes from Esther 3:6–7, describing the choice of date:Purim narrative

The

The Scroll of Esther

The Book of Esther (; ; ), also known in Hebrew as "the Scroll" ("the Megillah"), is a book in the third section (, "Writings") of the Hebrew Bible. It is one of the Five Scrolls () in the Hebrew Bible and later became part of the Christian ...

takes place over 9 years and begins with a six-month drinking feast given by King Ahasuerus

Ahasuerus ( ; , commonly ''Achashverosh''; , in the Septuagint; in the Vulgate) is a name applied in the Hebrew Bible to three rulers of Ancient Persia and to a Babylonian official (or Median king) first appearing in the Tanakh in the Book of ...

of the Persian Empire

The Achaemenid Empire or Achaemenian Empire, also known as the Persian Empire or First Persian Empire (; , , ), was an Iranian empire founded by Cyrus the Great of the Achaemenid dynasty in 550 BC. Based in modern-day Iran, it was the larg ...

for the army and Media

Media may refer to:

Communication

* Means of communication, tools and channels used to deliver information or data

** Advertising media, various media, content, buying and placement for advertising

** Interactive media, media that is inter ...

and the satraps

A satrap () was a governor of the provinces of the ancient Median kingdom, Median and Achaemenid Empire, Persian (Achaemenid) Empires and in several of their successors, such as in the Sasanian Empire and the Hellenistic period, Hellenistic empi ...

and princes of the 127 provinces of his kingdom, concluding with a seven-day drinking feast for the inhabitants of Shushan (Susa

Susa ( ) was an ancient city in the lower Zagros Mountains about east of the Tigris, between the Karkheh River, Karkheh and Dez River, Dez Rivers in Iran. One of the most important cities of the Ancient Near East, Susa served as the capital o ...

), rich and poor, and a separate drinking feast for the women organized by Queen Vashti

Vashti (; ; ) was a queen of Achaemenid Empire, Persia and the first wife of Persian king Ahasuerus in the Book of Esther, a book included within the Hebrew Bible, Tanakh and the Old Testament which is read on the Jewish holidays, Jewish holiday ...

in the pavilion of the royal courtyard.

At this feast, Ahasuerus becomes thoroughly drunk, and prompted by his courtiers, orders his wife Vashti to 'display her beauty' before the nobles and populace, while wearing her royal crown. Vashti's refusal embarrasses him in front of his guests and prompts him to demote her from her position as queen. Ahasuerus then orders all of the beautiful women throughout the empire to be presented to him, so that he can choose a new queen to replace Vashti. One of these is Esther

Esther (; ), originally Hadassah (; ), is the eponymous heroine of the Book of Esther in the Hebrew Bible. According to the biblical narrative, which is set in the Achaemenid Empire, the Persian king Ahasuerus falls in love with Esther and ma ...

, who was orphaned at a young age and is being fostered by her first cousin Mordecai

Mordecai (; also Mordechai; , IPA: ) is one of the main personalities in the Book of Esther in the Hebrew Bible. He is the cousin and guardian of Esther, who became queen of Persia under the reign of Ahasuerus (Xerxes I). Mordecai's loyalty and ...

, a member of the Sanhedrin

The Sanhedrin (Hebrew and Middle Aramaic , a loanword from , 'assembly,' 'sitting together,' hence ' assembly' or 'council') was a Jewish legislative and judicial assembly of either 23 or 70 elders, existing at both a local and central level i ...

. She finds favor in the King's eyes, and is made his new wife. Esther

Esther (; ), originally Hadassah (; ), is the eponymous heroine of the Book of Esther in the Hebrew Bible. According to the biblical narrative, which is set in the Achaemenid Empire, the Persian king Ahasuerus falls in love with Esther and ma ...

does not reveal her origins or that she is Jewish

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of History of ancient Israel and Judah, ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, rel ...

, as Mordecai told her not to. Based on the choice of words used in the text some rabbinic commentators state that she was actually Mordecai's wife.

Shortly afterwards, Mordecai discovers a plot by two palace guards Bigthan and Teresh to kill Ahasuerus. They are apprehended and hanged

Hanging is killing a person by suspending them from the neck with a noose or ligature strangulation, ligature. Hanging has been a standard method of capital punishment since the Middle Ages, and has been the primary execution method in numerou ...

, and Mordecai's service to the King is recorded in the daily record of the court.

Ahasuerus appoints Haman

Haman ( ; also known as Haman the Agagite) is the main antagonist in the Book of Esther, who according to the Hebrew Bible was an official in the court of the Achaemenid Empire, Persian empire under King Ahasuerus#Book of Esther, Ahasuerus, comm ...

as his viceroy

A viceroy () is an official who reigns over a polity in the name of and as the representative of the monarch of the territory.

The term derives from the Latin prefix ''vice-'', meaning "in the place of" and the Anglo-Norman ''roy'' (Old Frenc ...

. Mordecai, who sits at the palace gates, falls into Haman's disfavor as he refuses to bow down to him. Having found out that Mordecai is Jewish, Haman plans to kill not just Mordecai but the entire Jewish minority in the empire. Obtaining Ahasuerus' permission and funds to execute this plan, he casts lots () to choose the date on which to do this—the 14th of the month of Adar. When Mordecai finds out about the plans, he puts on sackcloth and ashes, a sign of mourning, publicly weeping and lamenting, and many other Jews in Shushan and other parts of Ahasuerus' empire do likewise, with widespread penitence and fasting

Fasting is the act of refraining from eating, and sometimes drinking. However, from a purely physiological context, "fasting" may refer to the metabolic status of a person who has not eaten overnight (before "breakfast"), or to the metabolic sta ...

. Esther discovers what has transpired; there follows an exchange of messages between her and Mordecai, with Hatach, one of the palace servants, as the intermediary. Mordecai requests that she intercede with the King on behalf of the embattled Jews; she replies that nobody is allowed to approach the King, under penalty of death.

Esther says she will fast and pray for three days and asks Mordecai to request that all Jews of Persia fast and pray for three days together with her. She will then approach the King to seek his help, despite the law against doing so, and declares, 'If I perish, I perish.' On the third day, she seeks an audience with Ahasuerus, during which she invites him to a feast in the company of Haman. During the feast, she asks them to attend a further feast the next evening. Meanwhile, Haman is again offended by Mordecai's refusal to bow to him; egged on by his wife Zeresh and unidentified friends, he builds a gallows

A gallows (or less precisely scaffold) is a frame or elevated beam, typically wooden, from which objects can be suspended or "weighed". Gallows were thus widely used to suspend public weighing scales for large and heavy objects such as sa ...

for Mordecai, with the intention to hang him there the very next day.

That night, Ahasuerus suffers from insomnia

Insomnia, also known as sleeplessness, is a sleep disorder where people have difficulty sleeping. They may have difficulty falling asleep, or staying asleep for as long as desired. Insomnia is typically followed by daytime sleepiness, low ene ...

, and when the court's daily records are read to him to help him fall asleep, he learns of the services rendered by Mordecai in the earlier plot against his life. Ahasuerus asks whether anything was done for Mordecai and is told that he received no recognition for saving the King's life. Just then, Haman appears, and King Ahasuerus asks him what should be done for the man that the King wishes to honor. Thinking that the King is referring to Haman himself, Haman says that the honoree should be dressed in the King's royal robes and led around on the King's royal horse. To Haman's horror, the king instructs Haman to render such honors to Mordecai.

Later that evening, Ahasuerus and Haman attend Esther's second banquet, at which she reveals that she is Jewish and that Haman is planning to exterminate her people, which includes her. Ahasuerus becomes enraged and instead orders Haman hanged on the gallows that Haman had prepared for Mordecai. The previous decree against the Jewish people could not be nullified, so the King allows Mordecai and Esther to write another decree as they wish. They decree that Jewish people may preemptively kill those thought to pose a lethal risk. As a result, on 13 Adar, 500 attackers and 10 of Haman's sons are killed in Shushan. Throughout the empire 75,000 of the Jewish peoples' enemies are killed. On the 14th, another 300 are killed in Shushan. No spoils are taken.

Mordecai assumes the position of second in rank to Ahasuerus, and institutes an annual commemoration of the delivery of the Jewish people from annihilation.

Scriptural and rabbinical sources

The primary source relating to the origin of Purim is the

The primary source relating to the origin of Purim is the Book of Esther

The Book of Esther (; ; ), also known in Hebrew language, Hebrew as "the Scroll" ("the wikt:מגילה, Megillah"), is a book in the third section (, "Writings") of the Hebrew Bible. It is one of the Five Megillot, Five Scrolls () in the Hebr ...

, which became the last of the 24 books of the Hebrew Bible

The Hebrew Bible or Tanakh (;"Tanach"

. '' Great Assembly According to Jewish tradition the Great Assembly (, also translated as Great Synagogue or ''Synod'') was an assembly of possibly 120 scribes, sages, and prophets, which existed from the early Second Temple period (around 516 BCE) to the early He ...

. It is dated to the 4th century BCE and according to the . '' Great Assembly According to Jewish tradition the Great Assembly (, also translated as Great Synagogue or ''Synod'') was an assembly of possibly 120 scribes, sages, and prophets, which existed from the early Second Temple period (around 516 BCE) to the early He ...

Talmud

The Talmud (; ) is the central text of Rabbinic Judaism and the primary source of Jewish religious law (''halakha'') and Jewish theology. Until the advent of Haskalah#Effects, modernity, in nearly all Jewish communities, the Talmud was the cen ...

was a redaction by the Great Assembly of an original text by Mordechai.

The in the Mishnah

The Mishnah or the Mishna (; , from the verb ''šānā'', "to study and review", also "secondary") is the first written collection of the Jewish oral traditions that are known as the Oral Torah. Having been collected in the 3rd century CE, it is ...

(redacted CE) records the laws relating to Purim. The accompanying Tosefta

The Tosefta ( "supplement, addition") is a compilation of Jewish Oral Law from the late second century, the period of the Mishnah and the Jewish sages known as the '' Tannaim''.

Background

Jewish teachings of the Tannaitic period were cha ...

(redacted in the same period) and Gemara

The Gemara (also transliterated Gemarah, or in Yiddish Gemore) is an essential component of the Talmud, comprising a collection of rabbinical analyses and commentaries on the Mishnah and presented in 63 books. The term is derived from the Aram ...

(in the Jerusalem and Babylonian Talmud redacted CE and CE respectively) record additional contextual details such as Queen Vashti having been the daughter of Belshazzar

Belshazzar ( Babylonian cuneiform: ''Bēl-šar-uṣur'', meaning " Bel, protect the king"; ''Bēlšaʾṣṣar'') was the son and crown prince of Nabonidus (), the last king of the Neo-Babylonian Empire. Through his mother, he might have been ...

as well as details that accord with Josephus

Flavius Josephus (; , ; ), born Yosef ben Mattityahu (), was a Roman–Jewish historian and military leader. Best known for writing '' The Jewish War'', he was born in Jerusalem—then part of the Roman province of Judea—to a father of pr ...

, such as Esther having been of royal descent. Brief mention of Esther is made in Tractate ( 139b) and idolatry relating to worship of Haman is discussed in Tractate ( 61b).

The work Esther Rabbah is a Midrash

''Midrash'' (;"midrash"

. ''Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary''. ; or ''midrashot' ...

ic text divided in two parts. The first part dated to CE provides an exegetical commentary on the first two chapters of the Hebrew Book of Esther and provided source material for the . The second part may have been redacted as late as the 11th century CE, and contains commentary on the remaining chapters of Esther. It, too, contains the additional contextual material found in the (a chronicle of Jewish history from Adam to the age of . ''Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary''. ; or ''midrashot' ...

Titus

Titus Caesar Vespasianus ( ; 30 December 39 – 13 September AD 81) was Roman emperor from 79 to 81. A member of the Flavian dynasty, Titus succeeded his father Vespasian upon his death, becoming the first Roman emperor ever to succeed h ...

believed to have been written by Josippon or Joseph ben Gorion).

Historical views

Traditional historians

The 1st-century CE historian

The 1st-century CE historian Josephus

Flavius Josephus (; , ; ), born Yosef ben Mattityahu (), was a Roman–Jewish historian and military leader. Best known for writing '' The Jewish War'', he was born in Jerusalem—then part of the Roman province of Judea—to a father of pr ...

recounts the origins of Purim in Book 11 of his ''Antiquities of the Jews

''Antiquities of the Jews'' (; , ''Ioudaikē archaiologia'') is a 20-volume historiographical work, written in Greek, by the Roman-Jewish historian Josephus in the 13th year of the reign of the Roman emperor Domitian, which was 94 CE. It cont ...

''. He follows the Hebrew Book of Esther but shows awareness of some of the additional material found in the Greek

Greek may refer to:

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor of all kno ...

version (the Septuagint

The Septuagint ( ), sometimes referred to as the Greek Old Testament or The Translation of the Seventy (), and abbreviated as LXX, is the earliest extant Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible from the original Biblical Hebrew. The full Greek ...

) in that he too identifies Ahasuerus as Artaxerxes and provides the text of the king's letter. He also provides additional information on the dating of events relative to Ezra and Nehemiah. Josephus also records the Persian persecution of Jews and mentions Jews being forced to worship at Persian-erected shrines.William Whiston, ''The Works of Flavius Josephus, the Learned and Authentic Jewish Historian'', Milner and Sowerby, 1864, online edition Harvard University 2004. Cited in '' Contra Apionem'' which quotes a work referred to as ''Peri Ioudaion'' (''On the Jews''), which is credited to Hecataeus of Abdera Hecataeus (Greek: Ἑκαταῖος) is a Greek name shared by several historical figures:

* Hecataeus of Miletus

Hecataeus of Miletus (; ; c. 550 – c. 476 BC), son of Hegesander, was an early Greek historian and geographer.

Bio ...

(late fourth century BCE).

The Josippon, a 10th-century CE compilation of Jewish history, includes an account of the origins of Purim in its chapter 4. It too follows the original biblical account and includes additional traditions matching those found in the Greek version and Josephus (whom the author claims as a source) with the exception of the details of the letters found in the latter works. It also provides other contextual information relating to Jewish and Persian history such as the identification of Darius the Mede

Darius the Mede is mentioned in the Book of Daniel as King of Babylon between Belshazzar and Cyrus the Great, but he is not known to secular history and there is no space in the historical timeline between those two verified rulers. Belshazzar, w ...

as the uncle and father-in-law of Cyrus.

A brief Persian account of events is provided by Islamic historian Muhammad ibn Jarir al-Tabari

Abū Jaʿfar Muḥammad ibn Jarīr ibn Yazīd al-Ṭabarī (; 839–923 CE / 224–310 AH), commonly known as al-Ṭabarī (), was a Sunni Islam, Sunni Muslim ulama, scholar, polymath, Islamic history, historian, tafsir, exegete, faqīh, juris ...

in his '' History of the Prophets and Kings'' (completed 915 CE).Ehsan Yar-Shater, ''The History of al-Tabari : An Annotated Translation'', SUNY Press, 1989 Basing his account on Jewish and Christian sources, al-Tabari provides additional details such as the original Persian form "Asturya" for "Esther".Moshe Perlmann trans., ''The Ancient Kingdoms'', SUNY Press, 1985 He places events during the rule of Ardashir Bahman (Artaxerxes II

Arses (; 445 – 359/8 BC), known by his regnal name Artaxerxes II ( ; ), was King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire from 405/4 BC to 358 BC. He was the son and successor of Darius II () and his mother was Parysatis.

Soon after his accession, Ar ...

),Said Amir Arjomand, ''Artaxerxes, Ardasir and Bahman'', The Journal of the American Oriental Society, Vol. 118, 1998 but confuses him with Ardashir al-Tawil al-Ba (Artaxerxes I

Artaxerxes I (, ; ) was the fifth King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire, from 465 to December 424 BC. He was the third son of Xerxes I.

In Greek sources he is also surnamed "Long-handed" ( ''Makrókheir''; ), allegedly because his ri ...

), while assuming Ahasuerus to be the name of a co-ruler. Another brief Persian account is recorded by Masudi

al-Masʿūdī (full name , ), –956, was a historian, geographer and traveler. He is sometimes referred to as the "Herodotus of the Arabs". A polymath and prolific author of over twenty works on theology, history (Islamic and universal), geo ...

in ''The Meadows of Gold

''Meadows of Gold and Mines of Gems'' (, ') is a 10th century history book by an Abbasid scholar al-Masudi. Written in Arabic and encompassing the period from the beginning of the world (starting with Adam and Eve) through to the late Abbasid era ...

'' (completed 947 CE). He refers to a Jewish woman who had married the Persian King Bahman (Artaxerxes II), and delivered her people, thus corroborating this identification of Ahasuerus. He also mentions the woman's daughter, Khumay, who is not known in Jewish tradition but is well remembered in Persian folklore. Al-Tabari calls her ''Khumani'' and tells how her father (Ardashir Bahman) married her. Ferdowsi

Abu'l-Qâsem Ferdowsi Tusi (also Firdawsi, ; 940 – 1019/1025) was a Persians, Persian poet and the author of ''Shahnameh'' ("Book of Kings"), which is one of the world's longest epic poetry, epic poems created by a single poet, and the gre ...

in his ''Shahnameh

The ''Shahnameh'' (, ), also transliterated ''Shahnama'', is a long epic poem written by the Persian literature, Persian poet Ferdowsi between and 1010 CE and is the national epic of Greater Iran. Consisting of some 50,000 distichs or couple ...

'' ( CE) also tells of King Bahman marrying Khumay.

Modern Biblical scholarship generally identifies Ahasuerus

Ahasuerus ( ; , commonly ''Achashverosh''; , in the Septuagint; in the Vulgate) is a name applied in the Hebrew Bible to three rulers of Ancient Persia and to a Babylonian official (or Median king) first appearing in the Tanakh in the Book of ...

with Xerxes I of Persia

Xerxes I ( – August 465 BC), commonly known as Xerxes the Great, was a Persian ruler who served as the fourth King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire, reigning from 486 BC until his assassination in 465 BC. He was the son of Darius the Great ...

.

Modern scholarship views

Since the 1890s, several academics have suggested that Purim has its origin in aeuhemerized

In the fields of philosophy and mythography, euhemerism () is an approach to the interpretation of mythology in which mythological accounts are presumed to have originated from real historical events or personages. Euhemerism supposes that histor ...

Babylonian or Persian

Persian may refer to:

* People and things from Iran, historically called ''Persia'' in the English language

** Persians, the majority ethnic group in Iran, not to be conflated with the Iranic peoples

** Persian language, an Iranian language of the ...

myth

Myth is a genre of folklore consisting primarily of narratives that play a fundamental role in a society. For scholars, this is very different from the vernacular usage of the term "myth" that refers to a belief that is not true. Instead, the ...

or festival

A festival is an event celebrated by a community and centering on some characteristic aspect or aspects of that community and its religion or cultures. It is often marked as a local or national holiday, Melā, mela, or Muslim holidays, eid. A ...

(though which one is a subject of discussion). Isaac Kalimi find these hypotheses unlikely. Given the similarity of the names Esther and Mordecai to the Babylonian gods Ishtar

Inanna is the List of Mesopotamian deities, ancient Mesopotamian goddess of war, love, and fertility. She is also associated with political power, divine law, sensuality, and procreation. Originally worshipped in Sumer, she was known by the Akk ...

and Marduk

Marduk (; cuneiform: Dingir, ᵈAMAR.UTU; Sumerian language, Sumerian: "calf of the sun; solar calf"; ) is a god from ancient Mesopotamia and patron deity of Babylon who eventually rose to prominence in the 1st millennium BC. In B ...

, the absence of historical records mentioning a Jewish queen in the Achaemenid court, and the lack of any reference to Purim in Jewish sources before the first century BCE, scholars generally consider the Book of Esther to lack historical value and do not regard it as the origin of this Jewish festival. According to McCullough, there may be particles of truth behind the story of Esther, but the book in its current form contains errors and contradictions that should classify it as a historical novel (not a historical account). Based on Herodotus, Xerxes' wife was Amestris, daughter of Otanes, while there is no trace of Vashti or Esther in Herodotus' history.Sperling and Baumgarten also argues that if Mordecai was exiled from Judah with Jehoiachin (589 BCE), as the Book of Esther claims, Mordecai’s age during Xerxes’ time would have been over a hundred years. How could an elderly person have been employed as a government official by the Achaemenids? According to Mathia Delcor, the Book of Esther contains numerous errors in its depiction of Achaemenid history, which casts doubt on the credibility of the Purim story, although it cannot be said that the book emerged from a vacuum. For example, among the improbabilities that question the historical accuracy of the Book of Esther are: the feast held by the king for his officials, which lasted 180 days; Queen Vashti's disobedience to the king; the king's correspondence with various nations in their own languages and the decree that every man should be the master of his household (when the official language of the empire was Imperial Aramaic); and the granting of high positions to non-Persians and Some of the well-known errors in the Book of Esther include: the mention of 127 satrapies (provinces) in the Persian Empire, while Herodotus cites 20 satrapies. The artificial narrative of the book, which speaks of contrasts—Jews and idol-worshippers, the hanging of Haman and the appointment of Mordecai as vizier, the massacre of non-Jews and anti-Jewish killings—also suggests a legendary tale. Schellekens suggests that the festival of Purim may have been modeled after the Iranian festival of Magophonia, which the Iranians celebrated annually to commemorate the overthrow of Gaumata (who usurped the royal throne) and the restoration of the kingship to Darius the Great

Darius I ( ; – 486 BCE), commonly known as Darius the Great, was the third King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire, reigning from 522 BCE until his death in 486 BCE. He ruled the empire at its territorial peak, when it included much of West A ...

. Sperling and Baumgarten also says the entire story is full of improbabilities. For instance, Mordecai was known as a Jew in the court, yet his niece and adopted daughter, who visited him daily, managed to successfully conceal her nationality and religion. Moreover, the story feels artificially serious and suspiciously secular. The supplicants never mention God during times of danger, and there is no reference to God during the thanksgiving celebration after the Jews' salvation. As a result, the Talmudic rabbis had to add God's name to the Book of Esther, and the Greek and Aramaic translations of the book were made more devout.

Observances

Purim has more of a national than a religious character, and its status as a holiday is on a different level from those days ordained holy by theTorah

The Torah ( , "Instruction", "Teaching" or "Law") is the compilation of the first five books of the Hebrew Bible, namely the books of Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers and Deuteronomy. The Torah is also known as the Pentateuch () ...

. Hallel is not recited. As such, according to some authorities, business transactions and even manual labor are allowed on Purim under certain circumstances. A special prayer ( – "For the Miracles") is inserted into the Amidah

The ''Amidah'' (, ''Tefilat HaAmidah'', 'The Standing Prayer'), also called the ''Shemoneh Esreh'' ( 'eighteen'), is the central prayer of Jewish liturgy. Observant Jews recite the ''Amidah'' during each of the three services prayed on week ...

prayers during evening, morning and afternoon prayer services, and is also included in the ("Grace after Meals").

The four main mitzvot

In its primary meaning, the Hebrew word (; , ''mīṣvā'' , plural ''mīṣvōt'' ; "commandment") refers to a commandment from God to be performed as a religious duty. Jewish law () in large part consists of discussion of these commandments ...

(obligations) of the day are:

# Listening to the public reading, usually in synagogue, of the Book of Esther

The Book of Esther (; ; ), also known in Hebrew language, Hebrew as "the Scroll" ("the wikt:מגילה, Megillah"), is a book in the third section (, "Writings") of the Hebrew Bible. It is one of the Five Megillot, Five Scrolls () in the Hebr ...

in the evening and again in the following morning ().

# Sending food gifts to friends ().

# Giving charity

Charity may refer to:

Common meanings

* Charitable organization or charity, a non-profit organization whose primary objectives are philanthropy and social well-being of persons

* Charity (practice), the practice of being benevolent, giving and sha ...

to the poor ().

# Eating a festive meal ().

The three latter obligations apply only during the daytime hours of Purim.Reading of the Megillah

The first religious ceremony which is ordained for the celebration of Purim is the reading of the Book of Esther (the "Megillah") in the synagogue, a regulation which is ascribed in the Talmud (Megillah 2a) to the Sages of the

The first religious ceremony which is ordained for the celebration of Purim is the reading of the Book of Esther (the "Megillah") in the synagogue, a regulation which is ascribed in the Talmud (Megillah 2a) to the Sages of the Great Assembly

According to Jewish tradition the Great Assembly (, also translated as Great Synagogue or ''Synod'') was an assembly of possibly 120 scribes, sages, and prophets, which existed from the early Second Temple period (around 516 BCE) to the early He ...

, of which Mordecai

Mordecai (; also Mordechai; , IPA: ) is one of the main personalities in the Book of Esther in the Hebrew Bible. He is the cousin and guardian of Esther, who became queen of Persia under the reign of Ahasuerus (Xerxes I). Mordecai's loyalty and ...

is reported to have been a member. Originally this regulation was only supposed to be observed on the 14th of Adar; later, however, Rabbi Joshua ben Levi (3rd century CE) prescribed that the Megillah should also be read on the eve of Purim. Further, he obliged women to attend the reading of the Megillah, because women were also part of the miracle. The commentaries offer two reasons as to why women played a major role in the miracle. The first reason is that it was through a lady, Queen Esther

Esther (; ), originally Hadassah (; ), is the eponymous heroine of the Book of Esther in the Hebrew Bible. According to the biblical narrative, which is set in the Achaemenid Empire, the Persian king Ahasuerus falls in love with Esther and ma ...

, that the miraculous deliverance of the Jews was accomplished (Rashbam

Samuel ben Meir (Troyes, c. 1085 – c. 1158), after his death known as the "Rashbam", a Hebrew acronym for RAbbi SHmuel Ben Meir, was a leading French Tosafist and grandson of Shlomo Yitzhaki, "Rashi".

Biography

He was born in the vicinity of ...

). The second reason is that women were also threatened by the genocidal decree and were therefore equal beneficiaries of the miracle (Tosafot

The Tosafot, Tosafos or Tosfot () are Middle Ages, medieval commentaries on the Talmud. They take the form of critical and explanatory glosses, printed, in almost all Talmud editions, on the outer margin and opposite Rashi's notes.

The authors o ...

).

The Talmud prescribed three benedictions before the reading and one benediction after the reading. The Talmud added other provisions. For example, the reader is to pronounce the names of the ten sons of Haman

Haman ( ; also known as Haman the Agagite) is the main antagonist in the Book of Esther, who according to the Hebrew Bible was an official in the court of the Achaemenid Empire, Persian empire under King Ahasuerus#Book of Esther, Ahasuerus, comm ...

in one breath, to indicate their simultaneous death. An additional custom that probably began in medieval times is that the congregation recites aloud with the reader the verses Esther 2:5, Esther 8:15–16, and Esther 10:3, which relate the origin of Mordecai and his triumph.

The Megillah is read with a cantillation (a traditional chant) which is different from that which is used in the customary reading of the Torah. Besides the traditional cantillation, there are several verses or short phrases in the Megillah that are chanted in a different chant, the chant that is traditionally used during the reading of the book of Lamentations

The Book of Lamentations (, , from its incipit meaning "how") is a collection of poetic laments for the destruction of Jerusalem in 586 BCE. In the Hebrew Bible, it appears in the Ketuvim ("Writings") as one of the Five Megillot ("Five Scroll ...

. These verses are particularly sad, or they refer to Jews being in exile. When the Megillah reader jumps to the melody of the book of Lamentations for these phrases, it heightens the feeling of sadness in the listener.

In some communities, the Megillah is not chanted, but is read like a letter, because of the name ("epistle"), which is applied to the Book of Esther. It has been also customary since the time of the early medieval era of the Geonim

''Geonim'' (; ; also Romanization of Hebrew, transliterated Gaonim, singular Gaon) were the presidents of the two great Talmudic Academies in Babylonia, Babylonian Talmudic Academies of Sura Academy , Sura and Pumbedita Academy , Pumbedita, in t ...

to unroll the whole Megillah before reading it, to give it the appearance of an epistle. According to halakha

''Halakha'' ( ; , ), also Romanization of Hebrew, transliterated as ''halacha'', ''halakhah'', and ''halocho'' ( ), is the collective body of Judaism, Jewish religious laws that are derived from the Torah, Written and Oral Torah. ''Halakha'' is ...

(Jewish law), the Megillah may be read in any language intelligible to the audience.

According to the Mishnah ( Megillahbr>30b, the story of the attack on the Jews by

Amalek

Amalek (; ) is described in the Hebrew Bible as the enemy of the nation of the Israelites. The name "Amalek" can refer to the descendants of Amalek, the grandson of Esau, or anyone who lived in their territories in Canaan, or North African descend ...

, the progenitor of Haman, is also to be read.

Blessings before Megillah reading

Before the reading of the Megillah on Purim, both at night and again in the morning, the reader of the Megillah recites the following three blessings and at the end of each blessing the congregation then responds by answering "Amen" after each of the blessings. At the morning reading of the Megillah the congregation should have in mind that the third blessing applies to the other observances of the day as well as to the reading of the Megillah:Blessing and recitations after Megillah reading

After the Megillah reading, each member of the congregation who has heard the reading recites the following blessing. This blessing is not recited unless a was present for the Megillah reading: After the nighttime Megillah reading the following two paragraphs are recited: The first one is an acrostic poem that starts with each letter of the Hebrew alphabet, starting with "Who balked () the counsel of the nations and annulled the counsel of the cunning. When a wicked man stood up against us (), a wantonly evil branch of Amalek's offspring ..." and ending with "The rose of Jacob () was cheerful and glad, when they jointly saw Mordechai robed in royal blue. You have been their eternal salvation (), and their hope throughout generations." The second is recited at night, but after the morning Megillah reading only this is recited:The rose of Jacob was cheerful and glad, when they jointly saw Mordechai robed in royal blue. You have been their eternal salvation, and their hope throughout generations.At night and in the morning:

Women and Megillah reading

Women have an obligation to hear the Megillah because "they also were involved in that miracle." Orthodox communities, including most Modern Orthodox ones, however, generally do not allow women to lead the Megillah reading. Rabbinic authorities who hold that women should not read the Megillah for themselves, because of an uncertainty as to which blessing they should recite upon the reading, nonetheless agree that they have an obligation to hear it read. According to these authorities if women, or men for that matter, cannot attend the services in the synagogue, the Megillah should be read for them in private by any male over the age of thirteen. Often in Orthodox communities there is a special public reading only for women, conducted either in a private home or in a synagogue, but the Megillah is read by a man. Some Modern Orthodox leaders have held that women can serve as public Megillah readers. Women's megillah readings have become increasingly common in more liberalModern Orthodox Judaism

Modern Orthodox Judaism (also Modern Orthodox or Modern Orthodoxy) is a movement within Orthodox Judaism that attempts to Torah Umadda#Synthesis, synthesize Jewish principles of faith, Jewish values and the halakha, observance of Jewish law with t ...

, though women may only read for other women, according to Ashkenazi authorities.

Blotting out Haman's name

When Haman's name is read out loud during the public chanting of the Megillah in the synagogue, which occurs 54 times, the congregation engages in noise-making to blot out his name. The practice can be traced back to the

When Haman's name is read out loud during the public chanting of the Megillah in the synagogue, which occurs 54 times, the congregation engages in noise-making to blot out his name. The practice can be traced back to the Tosafists

Tosafists were rabbis of France, Germany, Bohemia and Austria, who lived from the 12th to the mid-15th centuries, in the period of Rishonim. The Tosafists composed critical and explanatory glosses (questions, notes, interpretations, rulings and ...

(the leading French and German rabbis of the 13th century). In accordance with a passage in the Midrash

''Midrash'' (;"midrash"

. ''Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary''. ; or ''midrashot' ...

, where the verse "Thou shalt blot out the remembrance of . ''Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary''. ; or ''midrashot' ...

Amalek

Amalek (; ) is described in the Hebrew Bible as the enemy of the nation of the Israelites. The name "Amalek" can refer to the descendants of Amalek, the grandson of Esau, or anyone who lived in their territories in Canaan, or North African descend ...

" is explained to mean "even from wood and stones." A custom developed of writing the name of Haman, the offspring of Amalek, on two smooth stones, and knocking them together until the name was blotted out. Some wrote the name of Haman on the soles of their shoes, and at the mention of the name stamped with their feet as a sign of contempt. Another method was to use a noisy ratchet

Ratchet may refer to:

Devices

* Ratchet (device), a mechanical device that allows movement in only one direction

* Ratchet effect in sociology and economics

* Ratchet, metonymic name for a socket wrench incorporating a ratcheting device

* Ratc ...

, called a (from the Hebrew , meaning "noise") and in Yiddish

Yiddish, historically Judeo-German, is a West Germanic language historically spoken by Ashkenazi Jews. It originated in 9th-century Central Europe, and provided the nascent Ashkenazi community with a vernacular based on High German fused with ...

a . Some of the rabbis protested against these uproarious excesses, considering them a disturbance of public worship, but the custom of using a ratchet in the synagogue on Purim is now almost universal, with the exception of Spanish and Portuguese Jews

Spanish and Portuguese Jews, also called Western Sephardim, Iberian Jews, or Peninsular Jews, are a distinctive sub-group of Sephardic Jews who are largely descended from Jews who lived as New Christians in the Iberian Peninsula during the fe ...

and other Sephardic Jews, who consider them an improper interruption of the reading. The great Ashkenazi halachic authority, Rabbi Moshe Isserles, affirmed and validated this custom in his notes on the Shulchan Aruch

The ''Shulhan Arukh'' ( ),, often called "the Code of Jewish Law", is the most widely consulted of the various legal codes in Rabbinic Judaism. It was authored in the city of Safed in what is now Israel by Joseph Karo in 1563 and published in ...

:It is also written that the young children are accustomed to draw pictures of Haman on trees or stones or to write the name of Haman on themselves and to strike one against the other in order to blot out his name according to "The name of Amalek shall surely be erased" (Devarim 25:19) and "But the fame of the wicked rots". (Proverbs 10:7). From this is derived the custom that we strike Haman wen we read the Megillah in the synagogue. We must not nullify any custom nor should we ridicule ny custombecause it was not for nothing that it was determined.

Food gifts and charity

The Book of Esther prescribes "the sending of portions one man to another, and gifts to the poor". According to

The Book of Esther prescribes "the sending of portions one man to another, and gifts to the poor". According to halakha

''Halakha'' ( ; , ), also Romanization of Hebrew, transliterated as ''halacha'', ''halakhah'', and ''halocho'' ( ), is the collective body of Judaism, Jewish religious laws that are derived from the Torah, Written and Oral Torah. ''Halakha'' is ...

, each adult must give at least two different foods to one person, and at least two charitable donations to two poor people.Barclay, Rabbi Elozor and Jaeger, Rabbi Yitzchok (2001). ''Guidelines: Over two hundred and fifty of the most commonly asked questions about Purim''. Southfield, MI: Targum Press. The food parcels are called ("sending of portions"), and in some circles the custom has evolved into a major gift-giving event.

To fulfill the mitzvah of giving charity to two poor people, one can give either food or money equivalent to the amount of food that is eaten at a regular meal. It is better to spend more on charity than on the giving of . In the synagogue, regular collections of charity are made on the festival and the money is distributed among the needy. No distinction is made among the poor; anyone who is willing to accept charity is allowed to participate. It is obligatory for the poorest Jew, even one who is himself dependent on charity, to give to other poor people.

Purim meal and festive drinking

On Purim day, a festive meal called the is held.

There is a longstanding custom of drinking wine at the feast. The Talmud (b. Megillah 7b) records that " Rava said: A person is obligated to become intoxicated on Purim, until they cannot distinguish between 'Blessed be Mordecai' and 'Cursed be Haman'". Several interpretations arose among the late medieval authorities, although in general the classical sources are unanimous in rejecting intoxicated excess; only beginning with the Hasidic masters was drunkenness occasionally endorsed.

On Purim day, a festive meal called the is held.

There is a longstanding custom of drinking wine at the feast. The Talmud (b. Megillah 7b) records that " Rava said: A person is obligated to become intoxicated on Purim, until they cannot distinguish between 'Blessed be Mordecai' and 'Cursed be Haman'". Several interpretations arose among the late medieval authorities, although in general the classical sources are unanimous in rejecting intoxicated excess; only beginning with the Hasidic masters was drunkenness occasionally endorsed. Maimonides

Moses ben Maimon (1138–1204), commonly known as Maimonides (, ) and also referred to by the Hebrew acronym Rambam (), was a Sephardic rabbi and Jewish philosophy, philosopher who became one of the most prolific and influential Torah schola ...

writes that one must "drink wine until drunk, and pass out from drink"; according to one view, he is interpreting the Talmud this way (a sleeping person cannot distinguish), but according to another, he is intentionally contradicting it. Joseph Karo

Joseph ben Ephraim Karo, also spelled Yosef Caro, or Qaro (; 1488 – March 24, 1575, 13 Nisan 5335 A.M.), was a prominent Sephardic Jewish rabbi renowned as the author of the last great codification of Jewish law, the ''Beit Yosef'', and its ...

writes that one must "never become drunk, as this is totally forbidden and leads to terrible sins. Rather, one must drink slightly more than usual", while Moses Isserles

Moses Isserles (; ; 22 February 1530 / 25 Adar I 5290 – 11 May 1572 / 18 Iyar 5332), also known by the acronym Rema, was an eminent Polish Ashkenazi rabbi, talmudist, and '' posek'' (expert in Jewish law). He is considered the "Maimonides o ...

writes that one may drink more or less, so long as the intent is pure. Yechiel Michel Epstein

Yechiel Michel ha-Levi Epstein ()

(24 January 1829 – 25 March 1908), often called "the ''Aruch haShulchan''" after his magnum opus, '' Aruch HaShulchan'', was a Rabbi and ''posek'' (authority in Jewish law) in Lithuania.

Biography

Yechiel Mi ...

suggests that "until" should be read exclusively, so that one is obligated to become drunk but not so drunk that they cannot distinguish Mordecai and Haman.

Fasts

The Fast of Esther, observed before Purim, on the 13th of Adar, is an original part of the Purim celebration, referred to in Esther 9:31–32. The first who mentions the Fast of Esther is Aḥai of Shabḥa (8th century CE) in ''She'iltot

She'iltot of Rav Achai Gaon, also known as Sheiltot de-Rav Ahai, or simply She'iltot (), is a rabbinic Halakha, halakhic work composed in the 8th century by Ahai of Shabha (variants: Aḥa of Shabha; Acha of Shabcha), during the geonic period. ''S ...

'' 4; the reason there given for its institution is based on an interpretation of Esther 9:18, Esther 9:31 and Talmud Megillah 2a: "The 13th was the time of gathering", which gathering is explained to have had also the purpose of public prayer and fasting. Some, however, used to fast three days in commemoration of the fasting of Esther; but as fasting was prohibited during the month of Nisan, the first and second Mondays and the Thursday following Purim were chosen. The fast of the 13th is still commonly observed; but when that date falls on Shabbat

Shabbat (, , or ; , , ) or the Sabbath (), also called Shabbos (, ) by Ashkenazi Hebrew, Ashkenazim, is Judaism's day of rest on the seventh day of the seven-day week, week—i.e., Friday prayer, Friday–Saturday. On this day, religious Jews ...

, the fast is pushed back to the preceding Thursday, Friday being needed to prepare for Sabbath and the following Purim festival.

Customs

Greetings

It is common to greet one another on Purim in Hebrew with (, inYiddish

Yiddish, historically Judeo-German, is a West Germanic language historically spoken by Ashkenazi Jews. It originated in 9th-century Central Europe, and provided the nascent Ashkenazi community with a vernacular based on High German fused with ...

with () or in Ladino with . The Hebrew greeting loosely translates to 'Happy Purim Holiday' and the Yiddish and Ladino translate to 'Happy Purim'.

Masquerading

The custom of masquerading in costumes and the wearing of masks probably originated among the Italian Jews at the end of the 15th century. The concept was possibly influenced by the Roman

The custom of masquerading in costumes and the wearing of masks probably originated among the Italian Jews at the end of the 15th century. The concept was possibly influenced by the Roman carnival

Carnival (known as Shrovetide in certain localities) is a festive season that occurs at the close of the Christian pre-Lenten period, consisting of Quinquagesima or Shrove Sunday, Shrove Monday, and Shrove Tuesday or Mardi Gras.

Carnival typi ...

and spread across Europe. The practice was only introduced into Middle Eastern countries during the 19th century. The first Jewish codifier to mention the custom was Judah Minz

Judah ben Eliezer ha-Levi Minz (c. 1405 – 1508), also known as Mahari Minz, was the most prominent Italian rabbi of his time. As his surname suggests, he immigrated around 1462 from Mainz to Italy. He officiated as rabbi of Padua for forty-seven ...

. Iranian Jews

Iranian Jews, (; ) also Persian Jews ( ) or Parsim, constitute one of the oldest communities of the Jewish diaspora. Dating back to the History of ancient Israel and Judah, biblical era, they originate from the Jews who relocated to Iran (his ...

use traditional Persian costumes and masks.

The primary reason for masquerading is that it alludes to the hidden aspect of the miracle of Purim, which was "disguised" by natural events but was really the work of the Almighty. Since charity is a central feature of the day, when givers and recipients disguise themselves, this also allows greater anonymity thus preserving the dignity of the recipient.

Additional explanations are based on:

*Targum

A targum (, ''interpretation'', ''translation'', ''version''; plural: targumim) was an originally spoken translation of the Hebrew Bible (also called the ) that a professional translator ( ''mǝṯurgǝmān'') would give in the common language o ...

on Esther (Chapter 3), which states that Haman's hate for Mordecai stemmed from Jacob

Jacob, later known as Israel, is a Hebrew patriarch of the Abrahamic religions. He first appears in the Torah, where he is described in the Book of Genesis as a son of Isaac and Rebecca. Accordingly, alongside his older fraternal twin brother E ...

's 'dressing up' like Esau

Esau is the elder son of Isaac in the Hebrew Bible. He is mentioned in the Book of Genesis and by the minor prophet, prophets Obadiah and Malachi. The story of Jacob and Esau reflects the historical relationship between Israel and Edom, aiming ...

to receive Isaac

Isaac ( ; ; ; ; ; ) is one of the three patriarchs (Bible), patriarchs of the Israelites and an important figure in the Abrahamic religions, including Judaism, Christianity, Islam, and the Baháʼí Faith. Isaac first appears in the Torah, in wh ...

's blessings.

*Others who "dressed up" or hid who they were in the story of Esther:

**Esther not revealing that she is a Jew.

**Mordecai wearing sackcloth.

**Mordecai being dressed in the king's clothing.

**" ny from among the peoples of the land became Jews; for the fear of the Jews was fallen upon them" (); on which the Vilna Gaon

Elijah ben Solomon Zalman, ( ''Rabbi Eliyahu ben Shlomo Zalman''), also known as the Vilna Gaon ( ''Der Vilner Goen''; ; or Elijah of Vilna, or by his Hebrew acronym Gr"a ("Gaon Rabbenu Eliyahu": "Our great teacher Elijah"; Sialiec, April 23, 172 ...

comments that those gentiles were not accepted as converts

Conversion or convert may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media

* ''The Convert'', a 2023 film produced by Jump Film & Television and Brouhaha Entertainment

* "Conversion" (''Doctor Who'' audio), an episode of the audio drama ''Cyberman''

* ...

because they only made themselves look Jewish on the outside, as they did this out of fear.

*To recall the episodes that only happened in "outside appearance" as stated in Talmud Megillah 12a) that the Jews bowed to Haman only from the outside, internally holding strong to their Jewish belief, and likewise, God only gave the appearance as if he was to destroy all the Jews while internally knowing that he will save them.

Burning of Haman's effigy

As early as the 5th century, there was a custom to burn aneffigy

An effigy is a sculptural representation, often life-size, of a specific person or a prototypical figure. The term is mostly used for the makeshift dummies used for symbolic punishment in political protests and for the figures burned in certain ...

of Haman on Purim. Prohibitions were issued against such displays under the reign of Flavius Augustus Honorius

Honorius (; 9 September 384 – 15 August 423) was Roman emperor from 393 to 423. He was the younger son of emperor Theodosius I and his first wife Aelia Flaccilla. After the death of Theodosius in 395, Honorius, under the regency of Stilich ...

(395–423) and of Theodosius II

Theodosius II ( ; 10 April 401 – 28 July 450), called "the Calligraphy, Calligrapher", was Roman emperor from 402 to 450. He was proclaimed ''Augustus (title), Augustus'' as an infant and ruled as the Eastern Empire's sole emperor after the ...

(408–450). The custom was popular during the Geonic period (9th and 10th centuries), and a 14th century scholar described how people would ride through the streets of Provence

Provence is a geographical region and historical province of southeastern France, which stretches from the left bank of the lower Rhône to the west to the France–Italy border, Italian border to the east; it is bordered by the Mediterrane ...

holding fir branches and blowing trumpets around a puppet of Haman which was hanged and later burnt. The practice continued into the 20th century, with children treating Haman as a sort of "Guy Fawkes

Guy Fawkes (; 13 April 1570 – 31 January 1606), also known as Guido Fawkes while fighting for the Spanish, was a member of a group of provincial English Catholics involved in the failed Gunpowder Plot of 1605. He was born and educate ...

". In the early 1950s, the custom was still observed in Iran and some remote communities in Kurdistan where young Muslims would sometimes join in.

Purim spiel

A Purim ''spiel'' (Purim play) is a comic dramatization that attempts to convey the saga of the Purim story. By the 18th century, in some parts of Eastern Europe, the Purim plays had evolved into broad-ranging satires with music and dance for which the story of Esther was little more than a pretext. Indeed, by the mid-19th century, some were even based on other biblical stories. Today, Purim spiels can revolve around anything relating to Jews, Judaism, or even community gossip that will bring cheer and comic relief to an audience celebrating the day.Songs

Songs associated with Purim are based on sources that are Talmudic, liturgical and cultural. Traditional Purim songs include ("When he Hebrew month ofAdar enters, we have a lot of joy"—Mishnah Taanith 4:1) and ("The Jews had light and gladness, joy and honor"—Esther 8:16). The prayer is sung at the conclusion of the Megillah reading. A number of children's songs (with non-liturgical sources) also exist: ''Once There Was a Wicked Wicked Man'', , ''Chag Purim, Chag Purim, Chag Gadol Hu LaYehudim'', , , , , , , , , .Traditional foods

On Purim,

On Purim, Ashkenazi Jews

Ashkenazi Jews ( ; also known as Ashkenazic Jews or Ashkenazim) form a distinct subgroup of the Jewish diaspora, that emerged in the Holy Roman Empire around the end of the first millennium CE. They traditionally speak Yiddish, a language ...

and Israeli Jews

Israeli Jews or Jewish Israelis ( ) comprise Israel's largest ethnic and religious community. The core of their demographic consists of those with a Jewish identity and their descendants, including ethnic Jews and religious Jews alike. Appr ...

(of both Ashkenazi and Sephardic descent) eat triangular pastries called hamantaschen ("Haman's pockets") or ("Haman's ears"). A sweet pastry dough is rolled out, cut into circles, and traditionally filled with a raspberry, apricot, date, or poppy seed

Poppy seed is an oilseed obtained from the poppy plant (''Papaver somniferum''). The tiny, kidney-shaped seeds have been harvested from dried seed pods by various civilizations for thousands of years. It is still widely used in many countries, ...

filling. More recently, flavors such as chocolate have also gained favor, while non-traditional experiments such as pizza hamantaschen also exist. The pastry is then wrapped up into a triangular shape with the filling either hidden or showing.

Among Sephardic Jews

Sephardic Jews, also known as Sephardi Jews or Sephardim, and rarely as Iberian Peninsular Jews, are a Jewish diaspora population associated with the historic Jewish communities of the Iberian Peninsula (Spain and Portugal) and their descendant ...

, a fried pastry called fazuelos is eaten, as well as a range of baked or fried pastries called Orejas de Haman (Haman's Ears) or Hojuelas de Haman. The Sephardic Jewish community in Jerusalem

Jerusalem is a city in the Southern Levant, on a plateau in the Judaean Mountains between the Mediterranean Sea, Mediterranean and the Dead Sea. It is one of the List of oldest continuously inhabited cities, oldest cities in the world, and ...

traditionally served Baklava

Baklava (, or ; ) is a layered pastry dessert made of filo pastry, filled with chopped nuts, and sweetened with syrup or honey. It was one of the most popular sweet pastries of Ottoman cuisine.

There are several theories for the origin of th ...

s, Kadayıf, Travadicos, Figuela, Tichpichtil, and Ma'amoul

Ma'amoul ( ) is a filled butter cookie made with semolina flour. It is popular throughout the Arab world. The filling can be made with dried fruits like figs, Phoenix dactylifera, dates, or Nut (fruit), nuts such as pistachios or walnuts, and o ...

during Purim.רשליקה - Rashelika - ניחוח המטבח הירושלמי ספרדי המסורתי. 1999. pp. 82-87 ''Travadicos'' is a term for a deep-fried version of '' bourekitas'' that is soaked in honey and filled with nuts. This name is used among Jews in Turkey, while for Jews in Greece

The history of the Jews in Greece can be traced back to at least the fourth century BCE. The oldest and the most characteristic Jewish group that has inhabited Greece are the Romaniotes, also known as "Greek Jews." The term "Greek Jew" is pre ...

, the same dish is known as ''bourekitas de muez''.

Seeds, nuts, legumes and green vegetables are customarily eaten on Purim, as the Talmud relates that Queen Esther ate only these foodstuffs in the palace of Ahasuerus, since she had no access to kosher food

Kosher foods are foods that conform to the Jewish dietary regulations of '' kashrut'' ( dietary law). The laws of ''kashrut'' apply to food derived from living creatures and kosher foods are restricted to certain types of mammals, birds and fish ...

.

Kreplach

Kreplach (from ) are small dumplings in Ashkenazi Jewish cuisine filled with ground meat, mashed potatoes or another filling, usually boiled and served in chicken soup, though they may also be served fried. They are similar to other types of du ...

, a kind of dumpling

Dumplings are a broad class of dishes that consist of pieces of cooked dough (made from a variety of starchy sources), often wrapped around a filling. The dough can be based on bread, wheat or other flours, or potatoes, and it may be filled wi ...

filled with cooked meat, chicken or liver and served in soup, are traditionally served by Ashkenazi Jews on Purim. "Hiding" the meat inside the dumpling serves as another reminder of the story of Esther, the only book of Hebrew scriptures besides The Song of Songs that does not contain a single reference to God, who seems to hide behind the scenes. Some Sephardic Jews traditionally eat cooked green fava beans

''Vicia faba'', commonly known as the broad bean, fava bean, or faba bean, is a species of vetch, a flowering plant in the pea and bean family Fabaceae. It is widely cultivated as a crop for human consumption, and also as a cover crop. Vari ...

in remembrance of Esther, who, in Ahasuerus' palace, could not consume meat and thus had to rely on vegetarian dishes. In the Middle Ages, European Jews would eat , a type of blintz or waffle

A waffle is a dish made from leavened Batter (cooking), batter or dough that is cooked between two plates that are patterned to give a characteristic size, shape, and surface impression. There are many variations based on the type of waffle iron ...

. Arany galuska, a dessert consisting of fried dough balls and vanilla custard, is traditional for Jews from Hungary and Romania, as well as their descendants.

Special breads are baked among various communities. In Moroccan Jewish communities, a Purim bread called ''ojos de Haman'' ("eyes of Haman") is sometimes baked in the shape of Haman's head, and the eyes, made of eggs, are plucked out to demonstrate the destruction of Haman. Among Polish Jews

The history of the Jews in Poland dates back at least 1,000 years. For centuries, Poland was home to the largest and most significant Jews, Jewish community in the world. Poland was a principal center of Jewish culture, because of the long pe ...

, ''koilitch'', a raisin Purim challah

Challah or hallah ( ; , ; 'c'''hallot'', 'c'''halloth'' or 'c'''hallos'', ), also known as berches in Central Europe, is a special bread in Jewish cuisine, usually braided and typically eaten on ceremonial occasions such as Shabbat ...

that is baked in a long twisted ring and topped with small colorful candies, is meant to evoke the colorful nature of the holiday.

Torah learning

There is a widespread tradition to study the Torah in a synagogue on Purim morning, during an event called "Yeshivas Mordechai Hatzadik" to commemorate all the Jews who were inspired by Mordechai to learn Torah to overturn the evil decree against them. Children are especially encouraged to participate with prizes and sweets due to the fact that Mordechai taught many children Torah during this time.In Jerusalem

Shushan Purim

Shushan Purim falls on Adar 15 and is the day on which Jews inJerusalem

Jerusalem is a city in the Southern Levant, on a plateau in the Judaean Mountains between the Mediterranean Sea, Mediterranean and the Dead Sea. It is one of the List of oldest continuously inhabited cities, oldest cities in the world, and ...

celebrate Purim. The day is also universally observed by omitting the tachanun

''Tachanun'' or ''Taḥanun'' ( "Supplication"), also called ''nefilat apayim'' ( "falling on the face"), is part of Judaism's morning (''Shacharit'') and afternoon (''Mincha'') prayer services; it follows the recitation of the ''Amidah'', the ce ...

prayer and having a more elaborate meal than on ordinary days.

Purim is celebrated on Adar 14 because the Jews in unwalled cities fought their enemies on Adar 13 and rested the following day. However, in Shushan, the capital city of the Achaemenid Empire

The Achaemenid Empire or Achaemenian Empire, also known as the Persian Empire or First Persian Empire (; , , ), was an Iranian peoples, Iranian empire founded by Cyrus the Great of the Achaemenid dynasty in 550 BC. Based in modern-day Iran, i ...

, the Jews were involved in defeating their enemies on Adar 13–14 and rested on the 15th (Esther 9:20–22). In commemoration of this, it was decided that while the victory would be celebrated universally on Adar

Adar (Hebrew: , ; from Akkadian ''adaru'') is the sixth month of the civil year and the twelfth month of the religious year on the Hebrew calendar, roughly corresponding to the month of March in the Gregorian calendar. It is a month of 29 days. ...

14, for Jews living in Shushan, the holiday would be held on Adar 15. Later, in deference to Jerusalem, the Sages determined that Purim would be celebrated on Adar 15 in all cities a wall had enclosed at the time of Joshua

Joshua ( ), also known as Yehoshua ( ''Yəhōšuaʿ'', Tiberian Hebrew, Tiberian: ''Yŏhōšuaʿ,'' Literal translation, lit. 'Yahweh is salvation'), Jehoshua, or Josue, functioned as Moses' assistant in the books of Book of Exodus, Exodus and ...

's conquest of Canaan

CanaanThe current scholarly edition of the Septuagint, Greek Old Testament spells the word without any accents, cf. Septuaginta : id est Vetus Testamentum graece iuxta LXX interprets. 2. ed. / recogn. et emendavit Robert Hanhart. Stuttgart : D ...

. This criterion allowed the city of Jerusalem to retain its importance for Jews, and although Shushan was not walled at the time of Joshua, it was made an exception since the miracle occurred there.

Today, there is debate as to whether outlying neighborhoods of Jerusalem are obliged to observe Purim on the 14th or 15th of Adar. Further doubts have arisen as to whether other cities were sufficiently walled in Joshua's era. It is therefore customary in certain towns including Hebron

Hebron (; , or ; , ) is a Palestinian city in the southern West Bank, south of Jerusalem. Hebron is capital of the Hebron Governorate, the largest Governorates of Palestine, governorate in the West Bank. With a population of 201,063 in ...

, Safed

Safed (), also known as Tzfat (), is a city in the Northern District (Israel), Northern District of Israel. Located at an elevation of up to , Safed is the highest city in the Galilee and in Israel.

Safed has been identified with (), a fortif ...

, Tiberias

Tiberias ( ; , ; ) is a city on the western shore of the Sea of Galilee in northern Israel. A major Jewish center during Late Antiquity, it has been considered since the 16th century one of Judaism's Four Holy Cities, along with Jerusalem, Heb ...

, Acre

The acre ( ) is a Unit of measurement, unit of land area used in the Imperial units, British imperial and the United States customary units#Area, United States customary systems. It is traditionally defined as the area of one Chain (unit), ch ...

, Ashdod

Ashdod (, ; , , or ; Philistine language, Philistine: , romanized: *''ʾašdūd'') is the List of Israeli cities, sixth-largest city in Israel. Located in the country's Southern District (Israel), Southern District, it lies on the Mediterranean ...

, Ashkelon

Ashkelon ( ; , ; ) or Ashqelon, is a coastal city in the Southern District (Israel), Southern District of Israel on the Mediterranean Sea, Mediterranean coast, south of Tel Aviv, and north of the border with the Gaza Strip.

The modern city i ...

, Beersheva

Beersheba ( / ; ), officially Be'er-Sheva, is the largest city in the Negev desert of southern Israel. Often referred to as the "Capital of the Negev", it is the centre of the fourth-most populous metropolitan area in Israel, the List of cities ...

, Beit She'an

Beit She'an ( '), also known as Beisan ( '), or Beth-shean, is a town in the Northern District (Israel), Northern District of Israel. The town lies at the Beit She'an Valley about 120 m (394 feet) below sea level.

Beit She'an is believed to ...

, Beit Shemesh

Beit Shemesh () is a city council (Israel), city located approximately west of Jerusalem in Israel's Jerusalem District. A center of Haredi Judaism and Modern Orthodoxy, Beit Shemesh has a population of 170,683 as of 2024.

The city is named afte ...

, Gaza, Gush Halav, Haifa

Haifa ( ; , ; ) is the List of cities in Israel, third-largest city in Israel—after Jerusalem and Tel Aviv—with a population of in . The city of Haifa forms part of the Haifa metropolitan area, the third-most populous metropolitan area i ...

, Jaffa