Second-generation Computer on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The history of computing hardware spans the developments from early devices used for simple calculations to today's complex computers, encompassing advancements in both analog and digital technology.

The first aids to computation were purely mechanical devices which required the operator to set up the initial values of an elementary

Since

Since

In 1642, while still a teenager,

In 1642, while still a teenager,  Around 1820, Charles Xavier Thomas de Colmar created what would over the rest of the century become the first successful, mass-produced mechanical calculator, the Thomas

Around 1820, Charles Xavier Thomas de Colmar created what would over the rest of the century become the first successful, mass-produced mechanical calculator, the Thomas

In the late 1880s, the American

In the late 1880s, the American

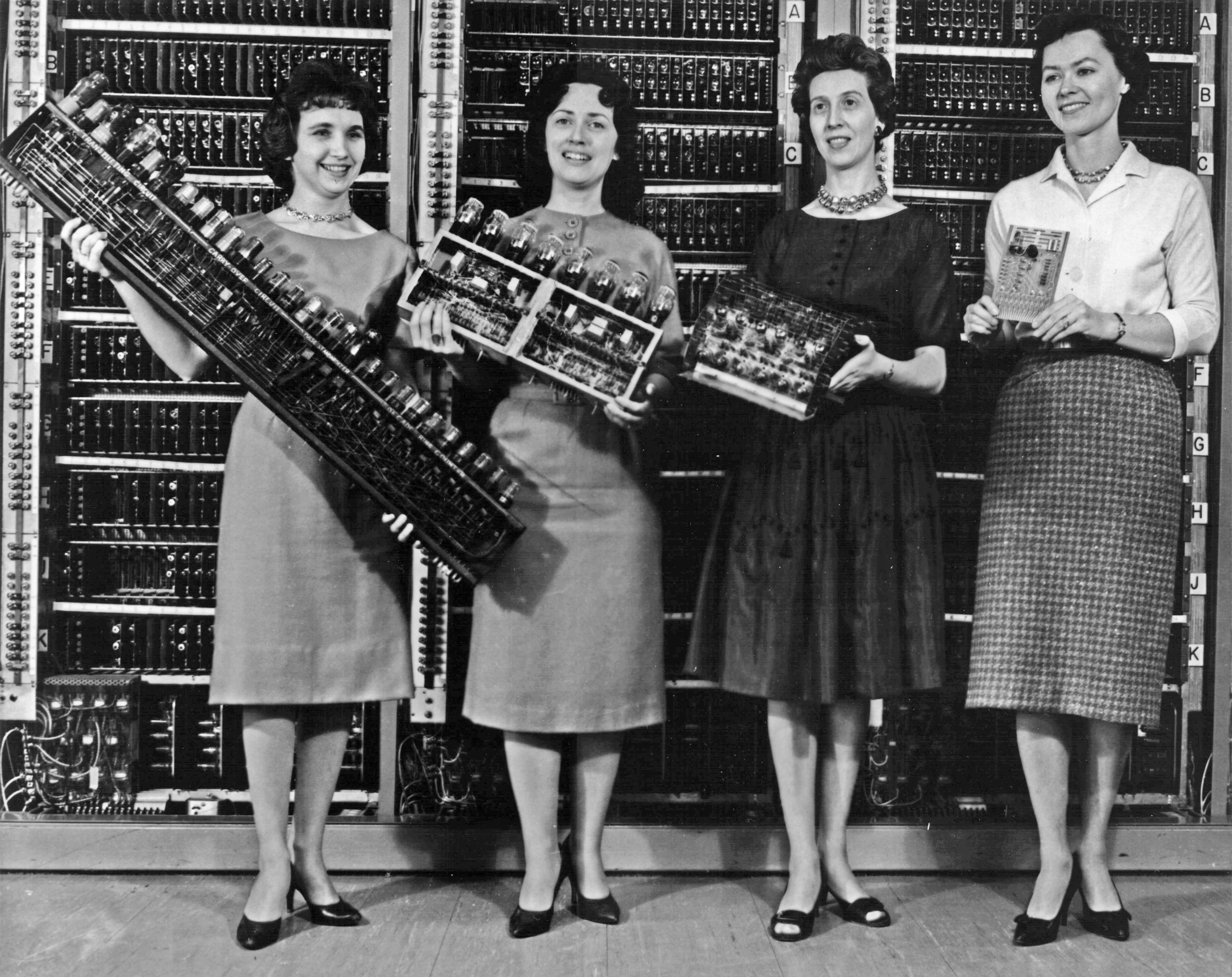

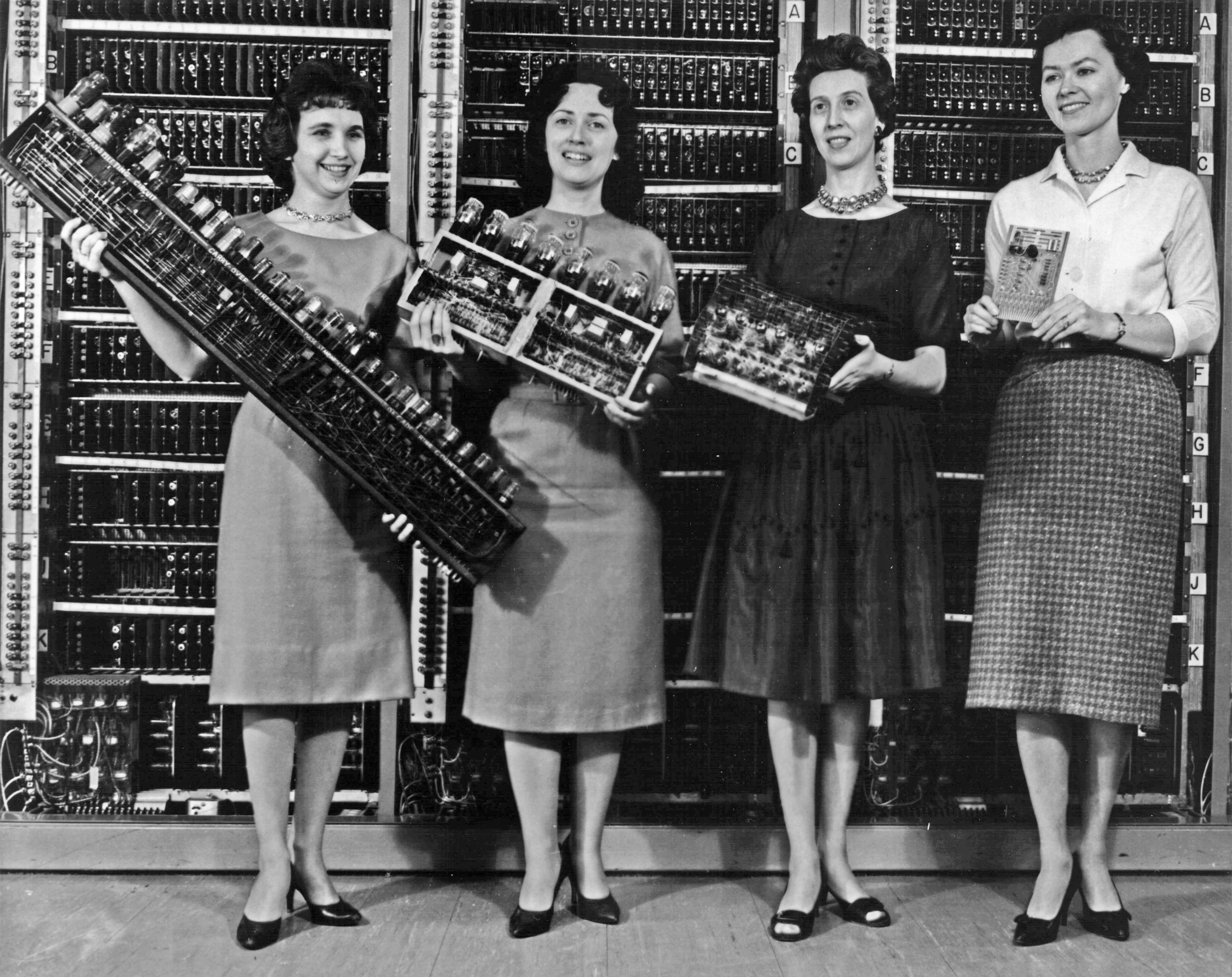

By the 20th century, earlier mechanical calculators, cash registers, accounting machines, and so on were redesigned to use electric motors, with gear position as the representation for the state of a variable. The word "computer" was a job title assigned to primarily women who used these calculators to perform mathematical calculations. By the 1920s, British scientist

By the 20th century, earlier mechanical calculators, cash registers, accounting machines, and so on were redesigned to use electric motors, with gear position as the representation for the state of a variable. The word "computer" was a job title assigned to primarily women who used these calculators to perform mathematical calculations. By the 1920s, British scientist

The

The

In the first half of the 20th century,

In the first half of the 20th century,

Memoria sobre las máquinas algébricas: con un informe de la Real academia de ciencias exactas, fisicas y naturales

', Misericordia, 1895. An important advance in analog computing was the development of the first

An important advance in analog computing was the development of the first

The principle of the modern computer was first described by computer scientist

The principle of the modern computer was first described by computer scientist

In 1941, Zuse followed his earlier machine up with the Z3, the world's first working

In 1941, Zuse followed his earlier machine up with the Z3, the world's first working

Purely

Purely

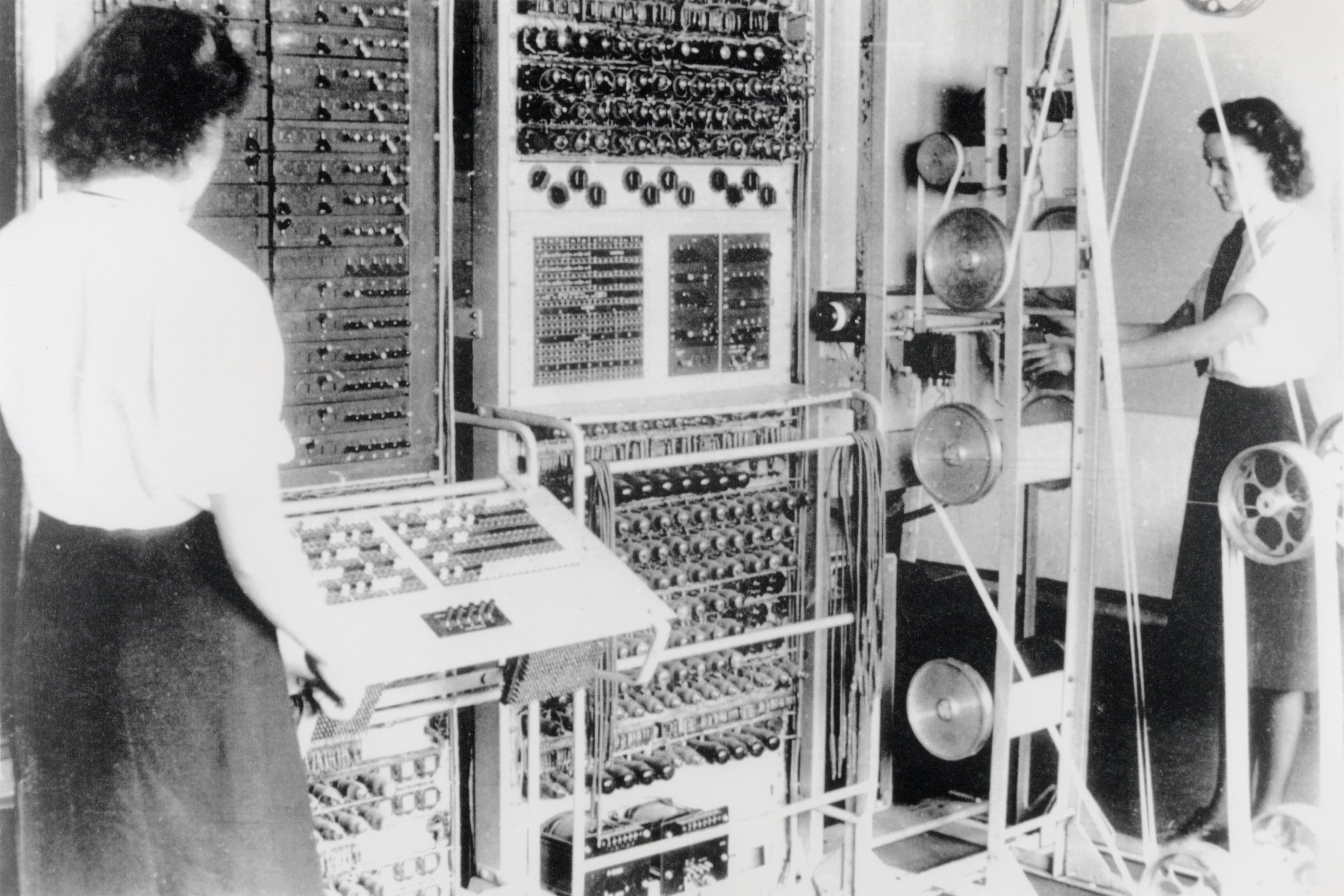

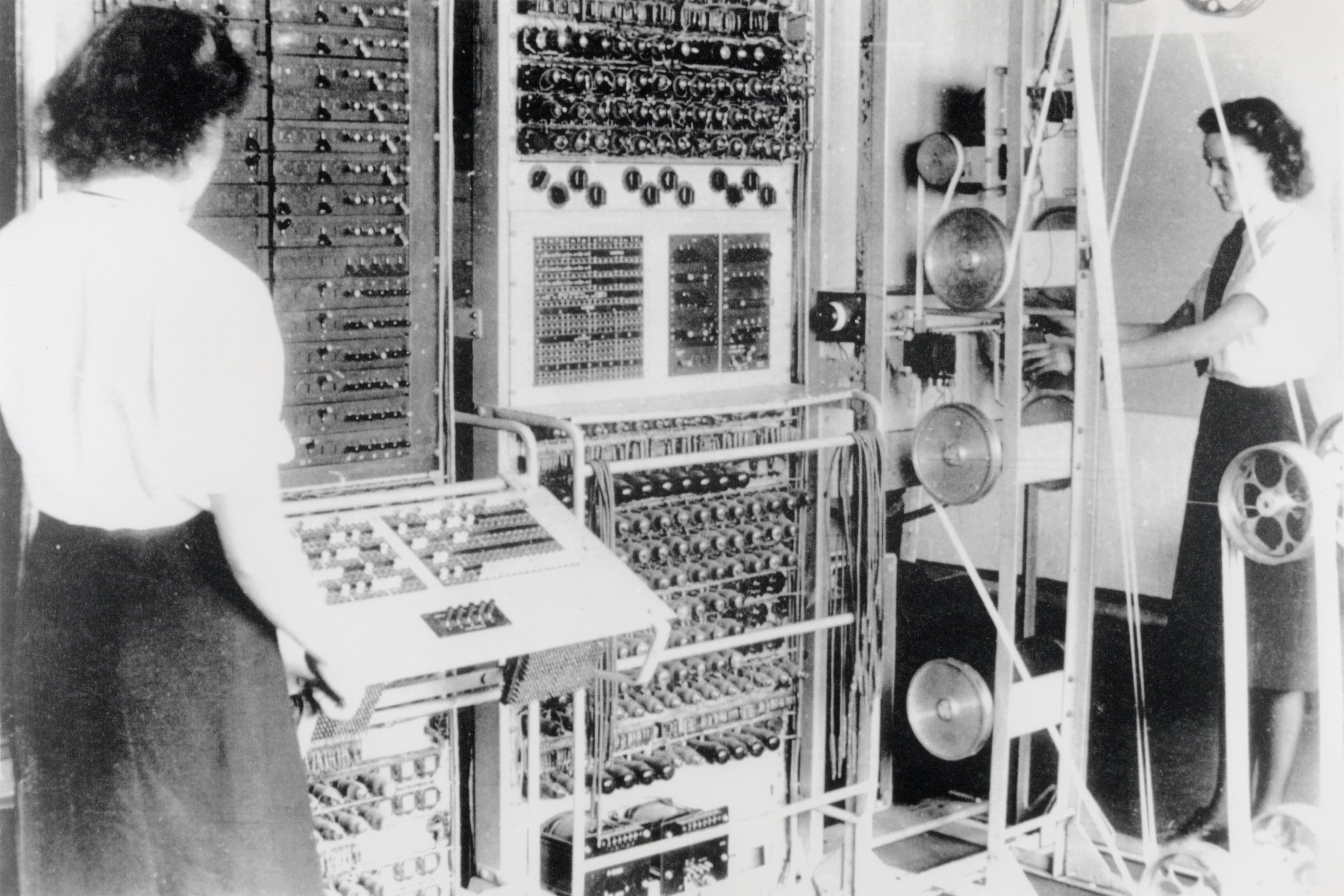

During World War II, British codebreakers at

During World War II, British codebreakers at  Colossus was the world's first electronic

Colossus was the world's first electronic  Without the use of these machines, the

Without the use of these machines, the

The

The

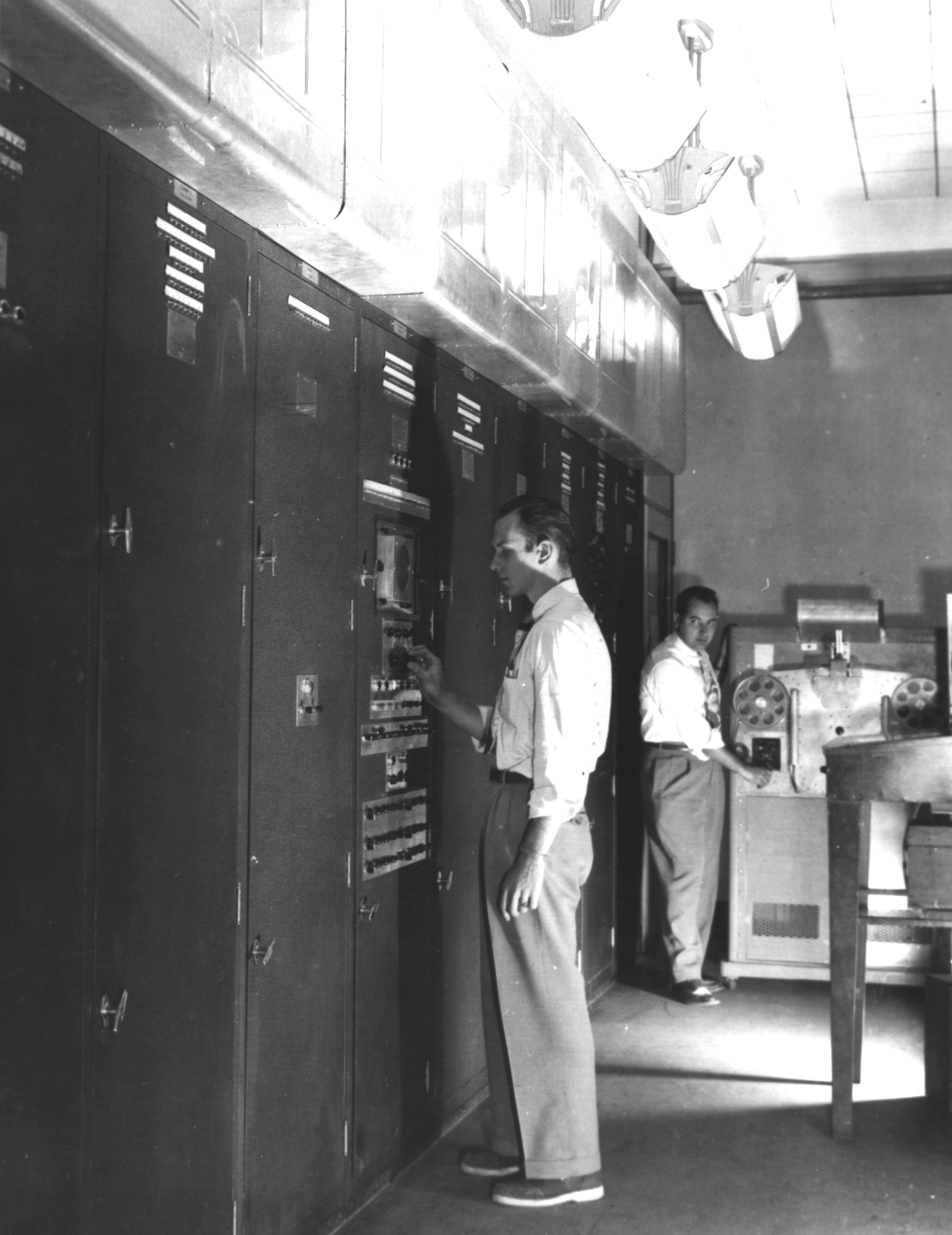

Compared to the UNIVAC, IBM introduced a smaller, more affordable computer in 1954 that proved very popular. The

Compared to the UNIVAC, IBM introduced a smaller, more affordable computer in 1954 that proved very popular. The

Magnetic drum memories were developed for the US Navy during WW II with the work continuing at

Magnetic drum memories were developed for the US Navy during WW II with the work continuing at

The bipolar

The bipolar

arithmetic

Arithmetic is an elementary branch of mathematics that deals with numerical operations like addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division. In a wider sense, it also includes exponentiation, extraction of roots, and taking logarithms.

...

operation, then manipulate the device to obtain the result. In later stages, computing devices began representing numbers in continuous forms, such as by distance along a scale, rotation of a shaft, or a specific voltage level. Numbers could also be represented in the form of digits, automatically manipulated by a mechanism. Although this approach generally required more complex mechanisms, it greatly increased the precision of results. The development of transistor technology, followed by the invention of integrated circuit chips, led to revolutionary breakthroughs.

Transistor-based computers and, later, integrated circuit-based computers enabled digital systems to gradually replace analog systems, increasing both efficiency and processing power. Metal-oxide-semiconductor

upright=1.3, Two power MOSFETs in amperes">A in the ''on'' state, dissipating up to about 100 watt">W and controlling a load of over 2000 W. A matchstick is pictured for scale.

In electronics, the metal–oxide–semiconductor field- ...

(MOS) large-scale integration

An integrated circuit (IC), also known as a microchip or simply chip, is a set of electronic circuits, consisting of various electronic components (such as transistors, resistors, and capacitors) and their interconnections. These components a ...

(LSI) then enabled semiconductor memory

Semiconductor memory is a digital electronic semiconductor device used for digital data storage, such as computer memory. It typically refers to devices in which data is stored within metal–oxide–semiconductor (MOS) memory cells on a si ...

and the microprocessor

A microprocessor is a computer processor (computing), processor for which the data processing logic and control is included on a single integrated circuit (IC), or a small number of ICs. The microprocessor contains the arithmetic, logic, a ...

, leading to another key breakthrough, the miniaturized personal computer

A personal computer, commonly referred to as PC or computer, is a computer designed for individual use. It is typically used for tasks such as Word processor, word processing, web browser, internet browsing, email, multimedia playback, and PC ...

(PC), in the 1970s. The cost of computers gradually became so low that personal computers by the 1990s, and then mobile computers

Mobile computing is human–computer interaction in which a computer is expected to be transported during normal usage and allow for transmission of data, which can include voice and video transmissions. Mobile computing involves mobile communi ...

(smartphone

A smartphone is a mobile phone with advanced computing capabilities. It typically has a touchscreen interface, allowing users to access a wide range of applications and services, such as web browsing, email, and social media, as well as multi ...

s and tablets) in the 2000s, became ubiquitous.

Early devices

Ancient and medieval

Devices have been used to aid computation for thousands of years, mostly usingone-to-one correspondence

In mathematics, a bijection, bijective function, or one-to-one correspondence is a function between two sets such that each element of the second set (the codomain) is the image of exactly one element of the first set (the domain). Equivale ...

with fingers

A finger is a prominent digit on the forelimbs of most tetrapod vertebrate animals, especially those with prehensile extremities (i.e. hands) such as humans and other primates. Most tetrapods have five digits (pentadactyly), Chambers 1998 p. 60 ...

. The earliest counting device was probably a form of tally stick

A tally stick (or simply a tally) was an ancient memory aid used to record and document numbers, quantities, and messages. Tally sticks first appear as animal bones carved with notches during the Upper Palaeolithic; a notable example is the Is ...

. The Lebombo bone from the mountains between Eswatini

Eswatini, formally the Kingdom of Eswatini, also known by its former official names Swaziland and the Kingdom of Swaziland, is a landlocked country in Southern Africa. It is bordered by South Africa on all sides except the northeast, where i ...

and South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the Southern Africa, southernmost country in Africa. Its Provinces of South Africa, nine provinces are bounded to the south by of coastline that stretches along the Atlantic O ...

may be the oldest known mathematical artifact. It dates from 35,000 BCE and consists of 29 distinct notches that were deliberately cut into a baboon

Baboons are primates comprising the biology, genus ''Papio'', one of the 23 genera of Old World monkeys, in the family Cercopithecidae. There are six species of baboon: the hamadryas baboon, the Guinea baboon, the olive baboon, the yellow ba ...

's fibula

The fibula (: fibulae or fibulas) or calf bone is a leg bone on the lateral side of the tibia, to which it is connected above and below. It is the smaller of the two bones and, in proportion to its length, the most slender of all the long bones. ...

. Later record keeping aids throughout the Fertile Crescent

The Fertile Crescent () is a crescent-shaped region in the Middle East, spanning modern-day Iraq, Israel, Jordan, Lebanon, Palestine, and Syria, together with northern Kuwait, south-eastern Turkey, and western Iran. Some authors also include ...

included calculi (clay spheres, cones, etc.) which represented counts of items, probably livestock or grains, sealed in hollow unbaked clay containers. The use of counting rods

Counting rods (筭) are small bars, typically 3–14 cm (1" to 6") long, that were used by mathematicians for calculation in ancient East Asia. They are placed either horizontally or vertically to represent any integer or rational number.

...

is one example. The abacus

An abacus ( abaci or abacuses), also called a counting frame, is a hand-operated calculating tool which was used from ancient times in the ancient Near East, Europe, China, and Russia, until the adoption of the Hindu–Arabic numeral system. A ...

was early used for arithmetic tasks. What we now call the Roman abacus

The Ancient Romans developed the Roman hand abacus, a portable, but less capable, base-10 version of earlier abacuses like those that were used by the Greeks and Babylonians.

Origin

The Roman abacus was the first portable calculating device for ...

was used in Babylonia

Babylonia (; , ) was an Ancient history, ancient Akkadian language, Akkadian-speaking state and cultural area based in the city of Babylon in central-southern Mesopotamia (present-day Iraq and parts of Kuwait, Syria and Iran). It emerged as a ...

as early as –2300 BC. Since then, many other forms of reckoning boards or tables have been invented. In a medieval European counting house

Counting is the process of determining the number of Element (mathematics), elements of a finite set of objects; that is, determining the size (mathematics), size of a set. The traditional way of counting consists of continually increasing a (men ...

, a checkered cloth would be placed on a table, and markers moved around on it according to certain rules, as an aid to calculating sums of money.

Several analog computer

An analog computer or analogue computer is a type of computation machine (computer) that uses physical phenomena such as Electrical network, electrical, Mechanics, mechanical, or Hydraulics, hydraulic quantities behaving according to the math ...

s were constructed in ancient and medieval times to perform astronomical calculations. These included the astrolabe

An astrolabe (; ; ) is an astronomy, astronomical list of astronomical instruments, instrument dating to ancient times. It serves as a star chart and Model#Physical model, physical model of the visible celestial sphere, half-dome of the sky. It ...

and Antikythera mechanism

The Antikythera mechanism ( , ) is an Ancient Greece, Ancient Greek hand-powered orrery (model of the Solar System). It is the oldest known example of an Analog computer, analogue computer. It could be used to predict astronomy, astronomical ...

from the Hellenistic world

In classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Greek history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the death of Cleopatra VII in 30 BC, which was followed by the ascendancy of the Roma ...

(c. 150–100 BC). In Roman Egypt

Roman Egypt was an imperial province of the Roman Empire from 30 BC to AD 642. The province encompassed most of modern-day Egypt except for the Sinai. It was bordered by the provinces of Crete and Cyrenaica to the west and Judaea, ...

, Hero of Alexandria

Hero of Alexandria (; , , also known as Heron of Alexandria ; probably 1st or 2nd century AD) was a Greek mathematician and engineer who was active in Alexandria in Egypt during the Roman era. He has been described as the greatest experimental ...

(c. 10–70 AD) made mechanical devices including automata

An automaton (; : automata or automatons) is a relatively self-operating machine, or control mechanism designed to automatically follow a sequence of operations, or respond to predetermined instructions. Some automata, such as bellstrikers i ...

and a programmable cart

A cart or dray (Australia and New Zealand) is a vehicle designed for transport, using two wheels and normally pulled by draught animals such as horses, donkeys, mules and oxen, or even smaller animals such as goats or large dogs.

A handcart ...

. The steam-powered automatic flute described by the ''Book of Ingenious Devices

The ''Book of Ingenious Devices'' (, ) is a large illustrated work on mechanical devices, including automata, published in 850 by the three brothers of Persian descent, the Banū Mūsā brothers (Ahmad, Muhammad and Hasan ibn Musa ibn Shakir) ...

'' (850) by the Persian-Baghdadi Banū Mūsā brothers

The three brothers Abū Jaʿfar, Muḥammad ibn Mūsā ibn Shākir (before 803 – February 873); Abū al-Qāsim, Aḥmad ibn Mūsā ibn Shākir (d. 9th century) and Al-Ḥasan ibn Mūsā ibn Shākir (d. 9th century), were Persian people, Pers ...

may have been the first programmable device.

Other early mechanical devices used to perform one or another type of calculations include the planisphere

In astronomy, a planisphere () is a star chart analog computing instrument in the form of two adjustable disks that rotate on a common pivot. It can be adjusted to display the visible stars for any time and date. It is an instrument to assist i ...

and other mechanical computing devices invented by Al-Biruni

Abu Rayhan Muhammad ibn Ahmad al-Biruni (; ; 973after 1050), known as al-Biruni, was a Khwarazmian Iranian scholar and polymath during the Islamic Golden Age. He has been called variously "Father of Comparative Religion", "Father of modern ...

(c. AD 1000); the equatorium

An equatorium (plural, equatoria) is an astronomy, astronomical Mechanical calculator, calculating instrument. It can be used for finding the positions of the Moon, Sun, and planets without arithmetic operations, using a geometrical model to re ...

and universal latitude-independent astrolabe by Al-Zarqali

Abū Isḥāq Ibrāhīm ibn Yaḥyā al-Naqqāsh al-Zarqālī al-Tujibi (); also known as Al-Zarkali or Ibn Zarqala (1029–1100), was an Arab maker of astronomical instruments and an astrologer from the western part of the Islamic world.

...

(c. AD 1015); the astronomical analog computers of other medieval Muslim astronomers and engineers; and the astronomical clock tower

Clock towers are a specific type of structure that house a turret clock and have one or more clock faces on the upper exterior walls. Many clock towers are freestanding structures but they can also adjoin or be located on top of another building ...

of Su Song

Su Song (, 1020–1101), courtesy name Zirong (), was a Chinese polymathic scientist and statesman who lived during the Song dynasty (960–1279). He exceled in numerous fields including but not limited to mathematics, astronomy, cartography, ...

(1094) during the Song dynasty

The Song dynasty ( ) was an Dynasties of China, imperial dynasty of China that ruled from 960 to 1279. The dynasty was founded by Emperor Taizu of Song, who usurped the throne of the Later Zhou dynasty and went on to conquer the rest of the Fiv ...

. The castle clock, a hydropower

Hydropower (from Ancient Greek -, "water"), also known as water power or water energy, is the use of falling or fast-running water to Electricity generation, produce electricity or to power machines. This is achieved by energy transformation, ...

ed mechanical astronomical clock

An astronomical clock, horologium, or orloj is a clock with special mechanisms and dials to display astronomical information, such as the relative positions of the Sun, Moon, zodiacal constellations, and sometimes major planets.

Definition ...

invented by Ismail al-Jazari in 1206, was the first programmable analog computer. Ramon Llull

Ramon Llull (; ; – 1316), sometimes anglicized as ''Raymond Lully'', was a philosopher, theologian, poet, missionary, Christian apologist and former knight from the Kingdom of Majorca.

He invented a philosophical system known as the ''Art ...

invented the Lullian Circle: a notional machine for calculating answers to philosophical questions (in this case, to do with Christianity) via logical combinatorics. This idea was taken up by Leibniz

Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (or Leibnitz; – 14 November 1716) was a German polymath active as a mathematician, philosopher, scientist and diplomat who is credited, alongside Sir Isaac Newton, with the creation of calculus in addition to many ...

centuries later, and is thus one of the founding elements in computing and information science.

Renaissance calculating tools

Scottish mathematician and physicistJohn Napier

John Napier of Merchiston ( ; Latinisation of names, Latinized as Ioannes Neper; 1 February 1550 – 4 April 1617), nicknamed Marvellous Merchiston, was a Scottish landowner known as a mathematician, physicist, and astronomer. He was the 8 ...

discovered that the multiplication and division of numbers could be performed by the addition and subtraction, respectively, of the logarithm

In mathematics, the logarithm of a number is the exponent by which another fixed value, the base, must be raised to produce that number. For example, the logarithm of to base is , because is to the rd power: . More generally, if , the ...

s of those numbers. While producing the first logarithmic tables, Napier needed to perform many tedious multiplications. It was at this point that he designed his 'Napier's bones

Napier's bones is a manually operated calculating device created by John Napier of Merchiston, Scotland for the calculation of products and quotients of numbers. The method was based on lattice multiplication, and also called ''rabdology'', a w ...

', an abacus-like device that greatly simplified calculations that involved multiplication and division.

Since

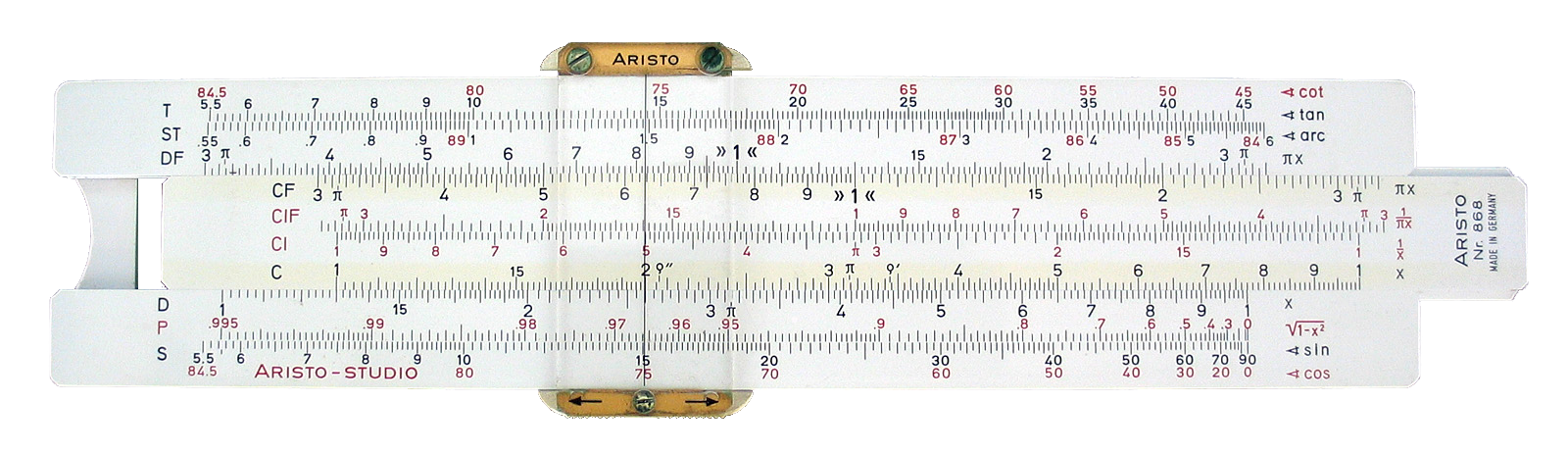

Since real number

In mathematics, a real number is a number that can be used to measure a continuous one- dimensional quantity such as a duration or temperature. Here, ''continuous'' means that pairs of values can have arbitrarily small differences. Every re ...

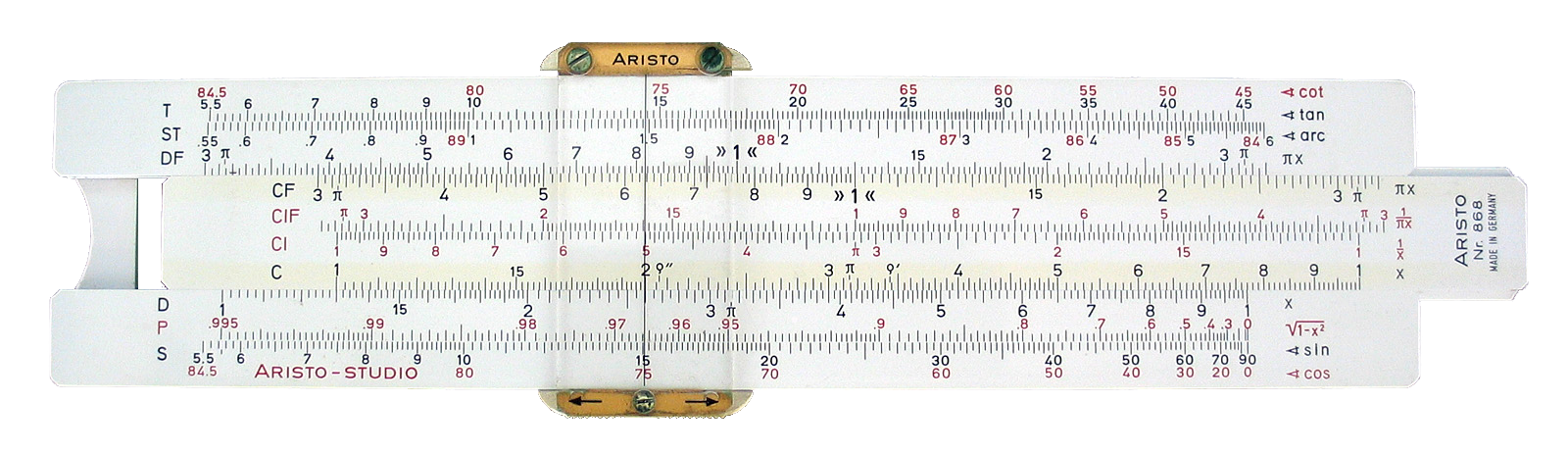

s can be represented as distances or intervals on a line, the slide rule

A slide rule is a hand-operated mechanical calculator consisting of slidable rulers for conducting mathematical operations such as multiplication, division, exponents, roots, logarithms, and trigonometry. It is one of the simplest analog ...

was invented in the 1620s, shortly after Napier's work, to allow multiplication and division operations to be carried out significantly faster than was previously possible. Edmund Gunter

Edmund Gunter (158110 December 1626), was an English clergyman, mathematician, geometer and astronomer of Welsh descent. He is best remembered for his mathematical contributions, which include the invention of the Gunter's chain, the #Gunter's q ...

built a calculating device with a single logarithmic scale at the University of Oxford

The University of Oxford is a collegiate university, collegiate research university in Oxford, England. There is evidence of teaching as early as 1096, making it the oldest university in the English-speaking world and the List of oldest un ...

. His device greatly simplified arithmetic calculations, including multiplication and division. William Oughtred

William Oughtred (5 March 1574 – 30 June 1660), also Owtred, Uhtred, etc., was an English mathematician and Anglican clergyman.'Oughtred (William)', in P. Bayle, translated and revised by J.P. Bernard, T. Birch and J. Lockman, ''A General ...

greatly improved this in 1630 with his circular slide rule. He followed this up with the modern slide rule in 1632, essentially a combination of two Gunter rules, held together with the hands. Slide rules were used by generations of engineers and other mathematically involved professional workers, until the invention of the pocket calculator

An electronic calculator is typically a portable electronic device used to perform calculations, ranging from basic arithmetic to complex mathematics.

The first solid-state electronic calculator was created in the early 1960s. Pocket-siz ...

.

Mechanical calculators

In 1609,Guidobaldo del Monte

Guidobaldo del Monte (11 January 1545 – 6 January 1607, var. Guidobaldi or Guido Baldi), Marquis del Monte, was an Italian mathematician, philosopher and astronomer of the 16th century.

Biography

Del Monte was born in Pesaro. His father, Rani ...

made a mechanical multiplier to calculate fractions of a degree. Based on a system of four gears, the rotation of an index on one quadrant corresponds to 60 rotations of another index on an opposite quadrant. Thanks to this machine, errors in the calculation of first, second, third and quarter degrees can be avoided. Guidobaldo is the first to document the use of gears for mechanical calculation.

Wilhelm Schickard, a German polymath

A polymath or polyhistor is an individual whose knowledge spans many different subjects, known to draw on complex bodies of knowledge to solve specific problems. Polymaths often prefer a specific context in which to explain their knowledge, ...

, designed a calculating machine in 1623 which combined a mechanized form of Napier's rods with the world's first mechanical adding machine built into the base. Because it made use of a single-tooth gear there were circumstances in which its carry mechanism would jam. A fire destroyed at least one of the machines in 1624 and it is believed Schickard was too disheartened to build another.

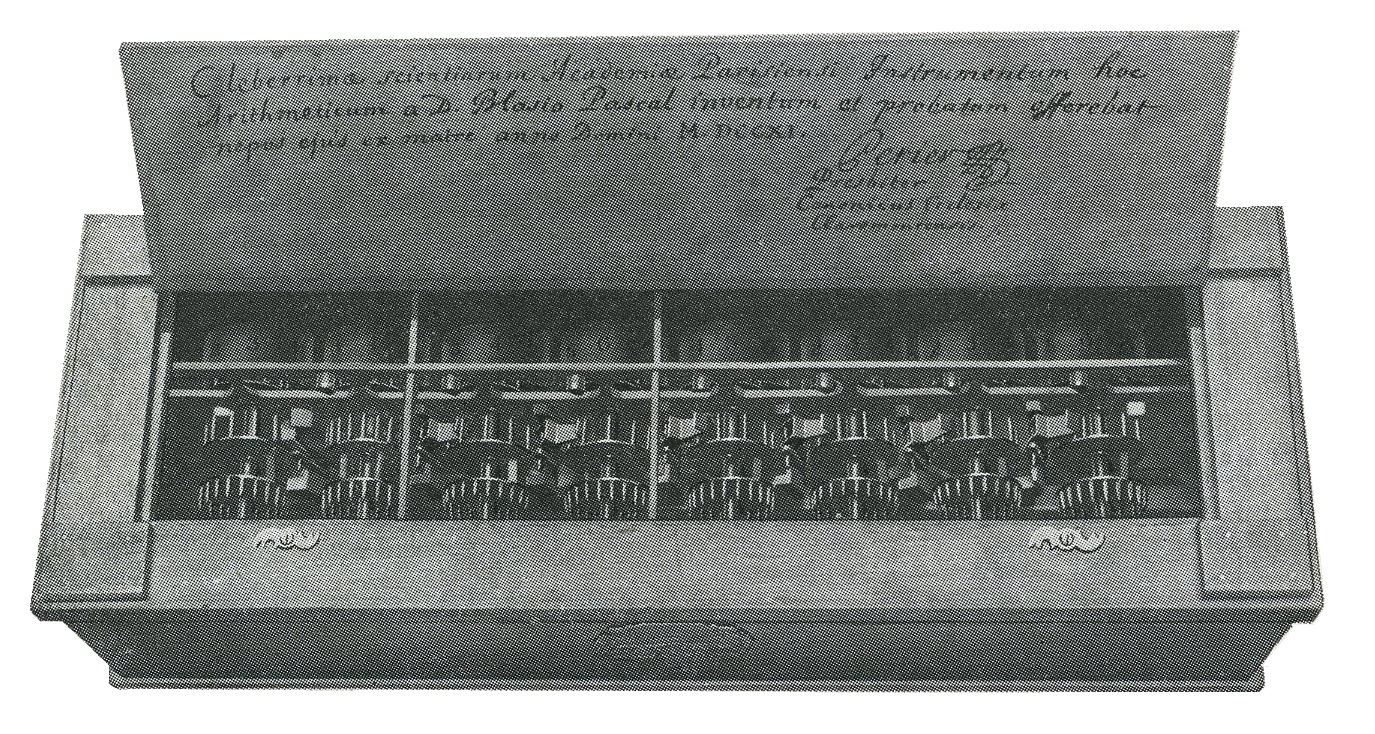

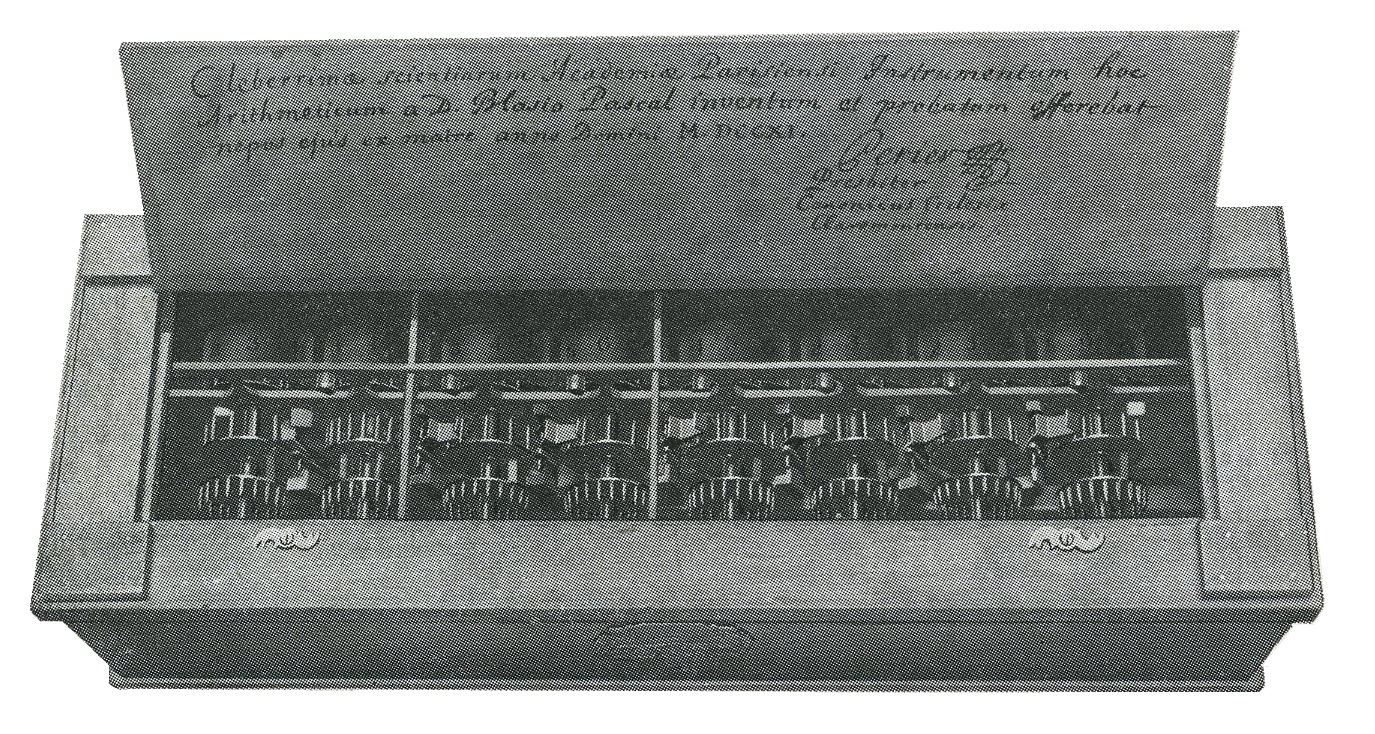

In 1642, while still a teenager,

In 1642, while still a teenager, Blaise Pascal

Blaise Pascal (19June 162319August 1662) was a French mathematician, physicist, inventor, philosopher, and Catholic Church, Catholic writer.

Pascal was a child prodigy who was educated by his father, a tax collector in Rouen. His earliest ...

started some pioneering work on calculating machines and after three years of effort and 50 prototypes he invented a mechanical calculator

A mechanical calculator, or calculating machine, is a mechanical device used to perform the basic operations of arithmetic automatically, or a simulation like an analog computer or a slide rule. Most mechanical calculators were comparable in si ...

. He built twenty of these machines (called Pascal's calculator

A Pascaline signed by Pascal in 1652

Top view and overview of the entire mechanism. This version of Pascaline was for accounting.

The pascaline (also known as the arithmetic machine or Pascal's calculator) is a mechanical calculator invented by ...

or Pascaline) in the following ten years. Nine Pascalines have survived, most of which are on display in European museums. A continuing debate exists over whether Schickard or Pascal should be regarded as the "inventor of the mechanical calculator" and the range of issues to be considered is discussed elsewhere.

Gottfried Wilhelm von Leibniz

Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (or Leibnitz; – 14 November 1716) was a German polymath active as a mathematician, philosopher, scientist and diplomat who is credited, alongside Sir Isaac Newton, with the creation of calculus in addition to many ...

invented the stepped reckoner and his famous stepped drum mechanism around 1672. He attempted to create a machine that could be used not only for addition and subtraction but would use a moveable carriage to enable multiplication and division. Leibniz once said "It is unworthy of excellent men to lose hours like slaves in the labour of calculation which could safely be relegated to anyone else if machines were used." However, Leibniz did not incorporate a fully successful carry mechanism. Leibniz also described the binary numeral system

A binary number is a number expressed in the base-2 numeral system or binary numeral system, a method for representing numbers that uses only two symbols for the natural numbers: typically "0" ( zero) and "1" ( one). A ''binary number'' may als ...

, a central ingredient of all modern computers. However, up to the 1940s, many subsequent designs (including Charles Babbage

Charles Babbage (; 26 December 1791 – 18 October 1871) was an English polymath. A mathematician, philosopher, inventor and mechanical engineer, Babbage originated the concept of a digital programmable computer.

Babbage is considered ...

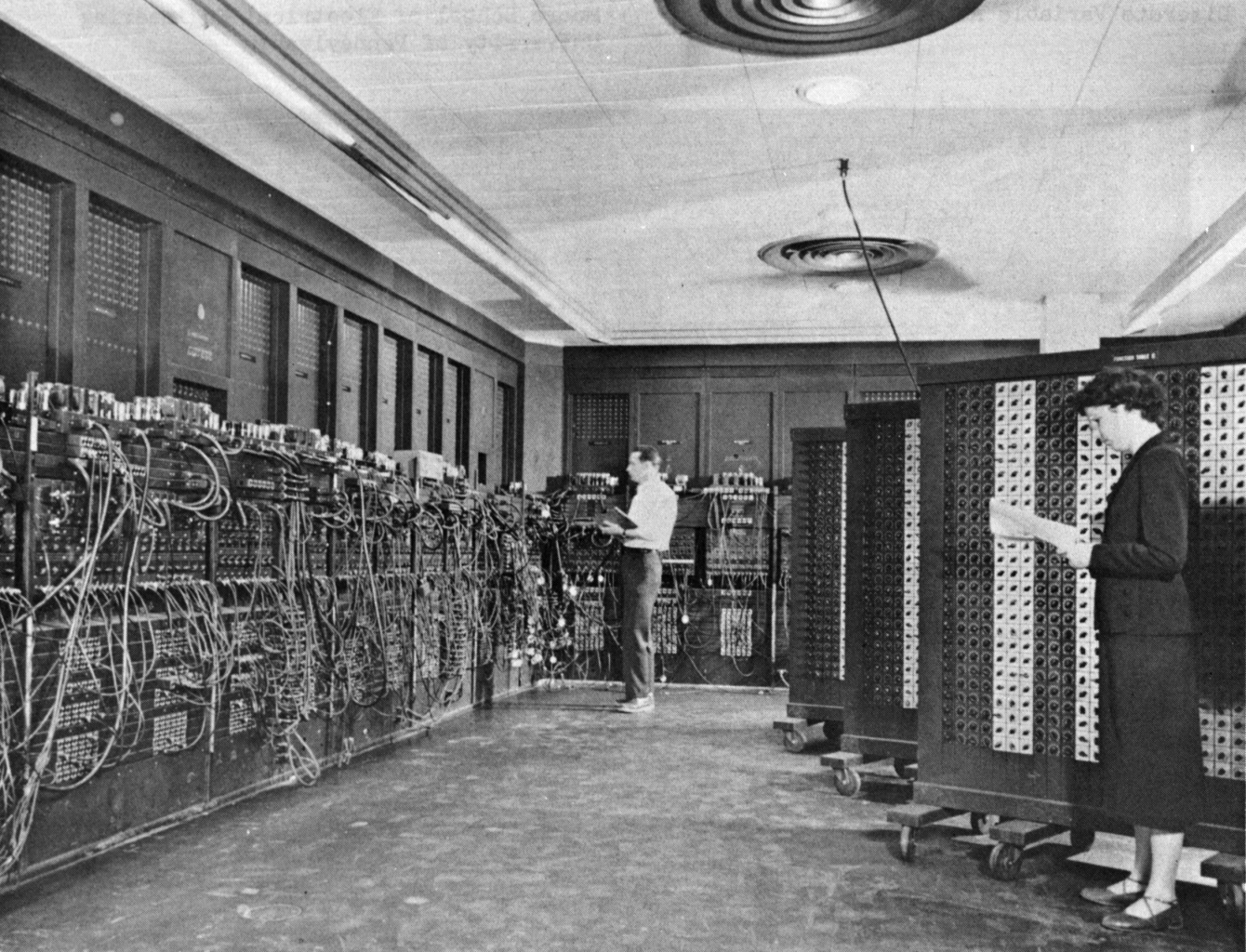

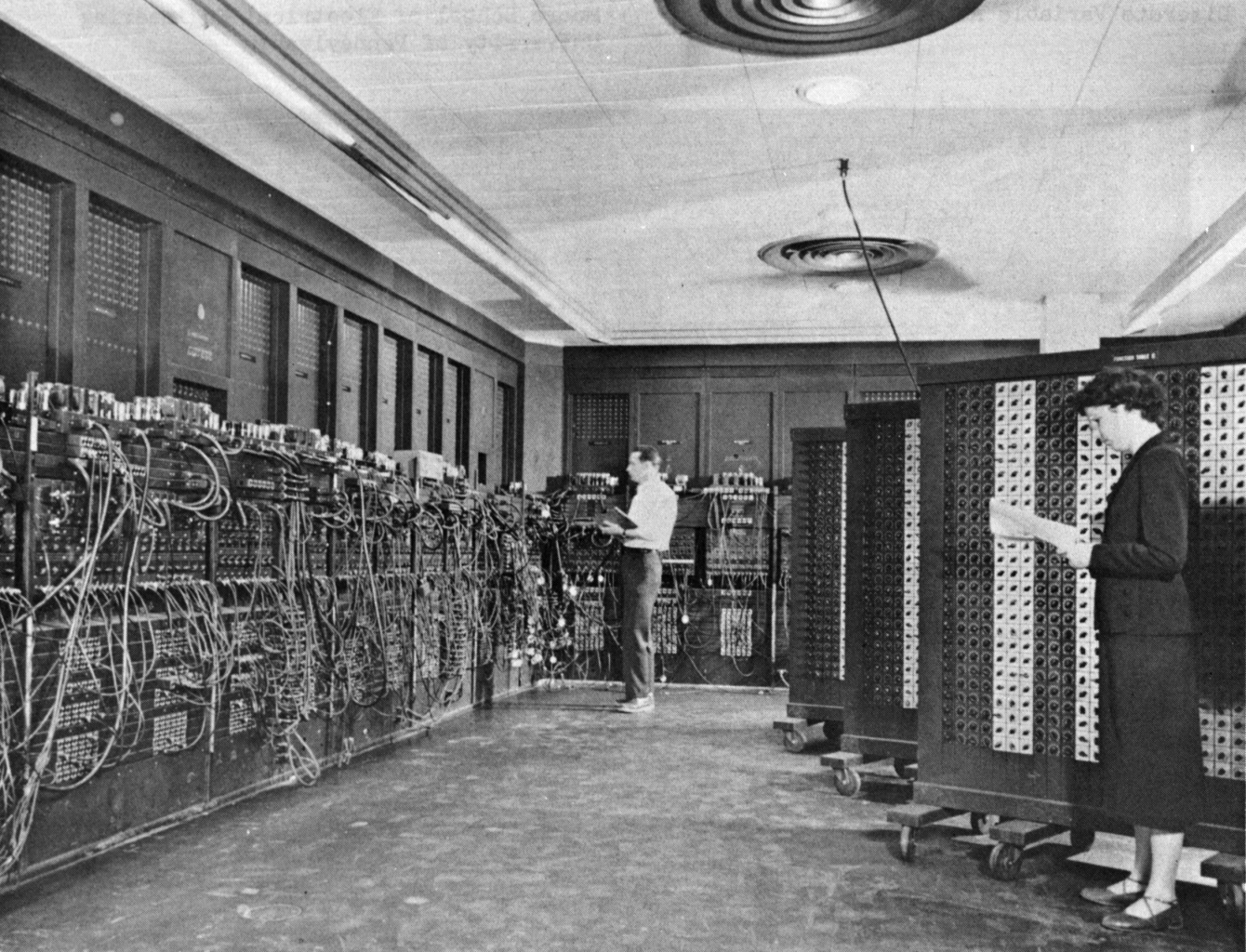

's machines of 1822 and even ENIAC

ENIAC (; Electronic Numerical Integrator and Computer) was the first Computer programming, programmable, Electronics, electronic, general-purpose digital computer, completed in 1945. Other computers had some of these features, but ENIAC was ...

of 1945) were based on the decimal system.

Around 1820, Charles Xavier Thomas de Colmar created what would over the rest of the century become the first successful, mass-produced mechanical calculator, the Thomas

Around 1820, Charles Xavier Thomas de Colmar created what would over the rest of the century become the first successful, mass-produced mechanical calculator, the Thomas Arithmometer

The arithmometer () was the first digital data, digital mechanical calculator strong and reliable enough to be used daily in an office environment. This calculator could add and subtract two numbers directly and perform Multiplication algorithm, ...

. It could be used to add and subtract, and with a moveable carriage the operator could also multiply, and divide by a process of long multiplication and long division. It utilised a stepped drum similar in conception to that invented by Leibniz. Mechanical calculators remained in use until the 1970s.

Punched-card data processing

In 1804, French weaverJoseph Marie Jacquard

Joseph Marie Charles ''dit'' (called or nicknamed) Jacquard (; 7 July 1752 – 7 August 1834) was a French weaver and merchant. He played an important role in the development of the earliest programmable loom (the "Jacquard loom"), which in tur ...

developed a loom in which the pattern being woven was controlled by a paper tape constructed from punched cards

A punched card (also punch card or punched-card) is a stiff paper-based medium used to store digital information via the presence or absence of holes in predefined positions. Developed over the 18th to 20th centuries, punched cards were wide ...

. The paper tape could be changed without changing the mechanical design of the loom. This was a landmark achievement in programmability. His machine was an improvement over similar weaving looms. Punched cards were preceded by punch bands, as in the machine proposed by Basile Bouchon

Basile Bouchon () (or Boachon) was a textile worker in the silk center in Lyon who invented a way to control a loom with a perforated paper tape in 1725. The son of an organ (music), organ maker, Bouchon partially automated the tedious setting u ...

. These bands would inspire information recording for automatic pianos and more recently numerical control

Computer numerical control (CNC) or CNC machining is the automated control of machine tools by a computer. It is an evolution of numerical control (NC), where machine tools are directly managed by data storage media such as punched cards or ...

machine tools.

In the late 1880s, the American

In the late 1880s, the American Herman Hollerith

Herman Hollerith (February 29, 1860 – November 17, 1929) was a German-American statistician, inventor, and businessman who developed an electromechanical tabulating machine for punched cards to assist in summarizing information and, later, in ...

invented data storage on punched card

A punched card (also punch card or punched-card) is a stiff paper-based medium used to store digital information via the presence or absence of holes in predefined positions. Developed over the 18th to 20th centuries, punched cards were widel ...

s that could then be read by a machine. To process these punched cards, he invented the tabulator and the keypunch

A keypunch is a device for precisely punching holes into stiff paper cards at specific locations as determined by keys struck by a human operator. Other devices included here for that same function include the gang punch, the pantograph punch, ...

machine. His machines used electromechanical relay

A relay

Electromechanical relay schematic showing a control coil, four pairs of normally open and one pair of normally closed contacts

An automotive-style miniature relay with the dust cover taken off

A relay is an electrically operated switc ...

s and counters. Hollerith's method was used in the 1890 United States census

The 1890 United States census was taken beginning June 2, 1890. The census determined the resident population of the United States to be 62,979,766, an increase of 25.5 percent over the 50,189,209 persons enumerated during the 1880 United States ...

. That census was processed two years faster than the prior census had been. "You may confidently look for the rapid reduction of the force of this office after the 1st of October, and the entire cessation of clerical work during the present calendar year. ... The condition of the work of the Census Division and the condition of the final reports show clearly that the work of the Eleventh Census will be completed at least two years earlier than was the work of the Tenth Census." — Carroll D. Wright, Commissioner of Labor in Charge Hollerith's company eventually became the core of IBM

International Business Machines Corporation (using the trademark IBM), nicknamed Big Blue, is an American Multinational corporation, multinational technology company headquartered in Armonk, New York, and present in over 175 countries. It is ...

.

By 1920, electromechanical tabulating machines could add, subtract, and print accumulated totals. Machine functions were directed by inserting dozens of wire jumpers into removable control panels. When the United States instituted Social Security

Welfare spending is a type of government support intended to ensure that members of a society can meet basic human needs such as food and shelter. Social security may either be synonymous with welfare, or refer specifically to social insurance ...

in 1935, IBM punched-card systems were used to process records of 26 million workers. Punched cards became ubiquitous in industry and government for accounting and administration.

Leslie Comrie

Leslie John Comrie FRS (15 August 1893 – 11 December 1950) was an astronomer and a pioneer in mechanical computation.

Life

Leslie John Comrie was born in Pukekohe (south of Auckland), New Zealand, on 15 August 1893.

He attended Auckland U ...

's articles on punched-card methods and W. J. Eckert's publication of ''Punched Card Methods in Scientific Computation'' in 1940, described punched-card techniques sufficiently advanced to solve some differential equations or perform multiplication and division using floating-point representations, all on punched cards and unit record machines. Such machines were used during World War II for cryptographic statistical processing, as well as a vast number of administrative uses. The Astronomical Computing Bureau of Columbia University

Columbia University in the City of New York, commonly referred to as Columbia University, is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in New York City. Established in 1754 as King's College on the grounds of Trinity Churc ...

performed astronomical calculations representing the state of the art in computing

Computing is any goal-oriented activity requiring, benefiting from, or creating computer, computing machinery. It includes the study and experimentation of algorithmic processes, and the development of both computer hardware, hardware and softw ...

.

Calculators

Lewis Fry Richardson

Lewis Fry Richardson, Fellow of the Royal Society, FRS (11 October 1881 – 30 September 1953) was an English mathematician, physicist, meteorologist, psychologist, and Pacifism, pacifist who pioneered modern mathematical techniques of weather ...

's interest in weather prediction led him to propose human computer

The term "computer", in use from the early 17th century (the first known written reference dates from 1613), meant "one who computes": a person performing mathematical calculations, before electronic calculators became available. Alan Turing ...

s and numerical analysis

Numerical analysis is the study of algorithms that use numerical approximation (as opposed to symbolic computation, symbolic manipulations) for the problems of mathematical analysis (as distinguished from discrete mathematics). It is the study of ...

to model the weather; to this day, the most powerful computers on Earth

Earth is the third planet from the Sun and the only astronomical object known to Planetary habitability, harbor life. This is enabled by Earth being an ocean world, the only one in the Solar System sustaining liquid surface water. Almost all ...

are needed to adequately model its weather using the Navier–Stokes equations

The Navier–Stokes equations ( ) are partial differential equations which describe the motion of viscous fluid substances. They were named after French engineer and physicist Claude-Louis Navier and the Irish physicist and mathematician Georg ...

.

Companies like Friden, Marchant Calculator

The Marchant Calculating Machine Company was founded in 1911 by Rodney and Alfred Marchant in Oakland, California.

The company built mechanical, and then electromechanical calculators which had a reputation for reliability. First models were sim ...

and Monroe

Monroe or Monroes may refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Monroe (surname)

* Monroe (given name)

* James Monroe, 5th President of the United States

* Marilyn Monroe, actress and model

Places United States

* Monroe, Arkansas, an unincorp ...

made desktop mechanical calculators from the 1930s that could add, subtract, multiply and divide. In 1948, the Curta was introduced by Austrian inventor Curt Herzstark. It was a small, hand-cranked mechanical calculator and as such, a descendant of Gottfried Leibniz

Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (or Leibnitz; – 14 November 1716) was a German polymath active as a mathematician, philosopher, scientist and diplomat who is credited, alongside Isaac Newton, Sir Isaac Newton, with the creation of calculus in ad ...

's Stepped Reckoner and Thomas

Thomas may refer to:

People

* List of people with given name Thomas

* Thomas (name)

* Thomas (surname)

* Saint Thomas (disambiguation)

* Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274) Italian Dominican friar, philosopher, and Doctor of the Church

* Thomas the A ...

' Arithmometer

The arithmometer () was the first digital data, digital mechanical calculator strong and reliable enough to be used daily in an office environment. This calculator could add and subtract two numbers directly and perform Multiplication algorithm, ...

.

The world's first ''all-electronic desktop'' calculator was the British Bell Punch

The Bell Punch Company was a British company manufacturing a variety of business machines, most notably several generations of public transport ticket machines and the world's first desktop electronic calculator, the Sumlock ANITA calculator, Su ...

ANITA, released in 1961. It used vacuum tube

A vacuum tube, electron tube, thermionic valve (British usage), or tube (North America) is a device that controls electric current flow in a high vacuum between electrodes to which an electric voltage, potential difference has been applied. It ...

s, cold-cathode tubes and Dekatron

In electronics, a Dekatron (or Decatron, or generically three-phase gas counting tube or glow-transfer counting tube or cold cathode tube) is a gas-filled decade counting tube. Dekatrons were used in computers, calculators, and other counti ...

s in its circuits, with 12 cold-cathode "Nixie" tubes for its display. The ANITA sold well since it was the only electronic desktop calculator available, and was silent and quick. The tube technology was superseded in June 1963 by the U.S. manufactured Friden EC-130, which had an all-transistor design, a stack of four 13-digit numbers displayed on a CRT

CRT or Crt most commonly refers to:

* Cathode-ray tube, a display

* Critical race theory, an academic framework of analysis

CRT may also refer to:

Law

* Charitable remainder trust, United States

* Civil Resolution Tribunal, Canada

* Columbia ...

, and introduced reverse Polish notation

Reverse Polish notation (RPN), also known as reverse Łukasiewicz notation, Polish postfix notation or simply postfix notation, is a mathematical notation in which operators ''follow'' their operands, in contrast to prefix or Polish notation ...

(RPN).

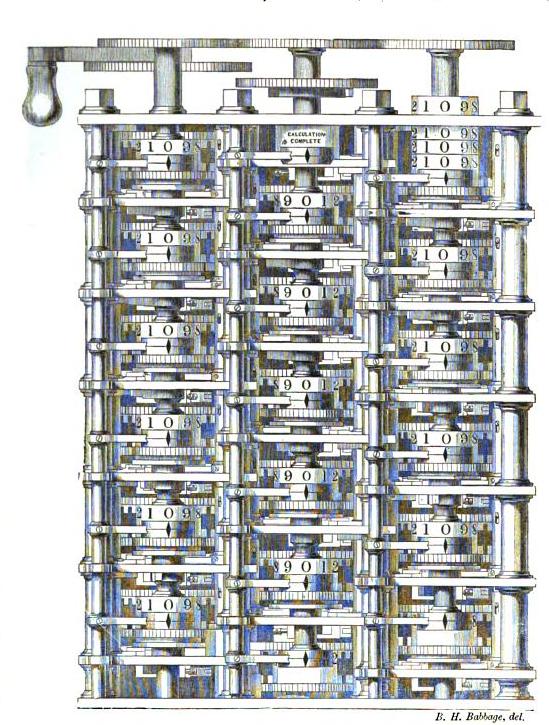

First proposed general-purpose computing device

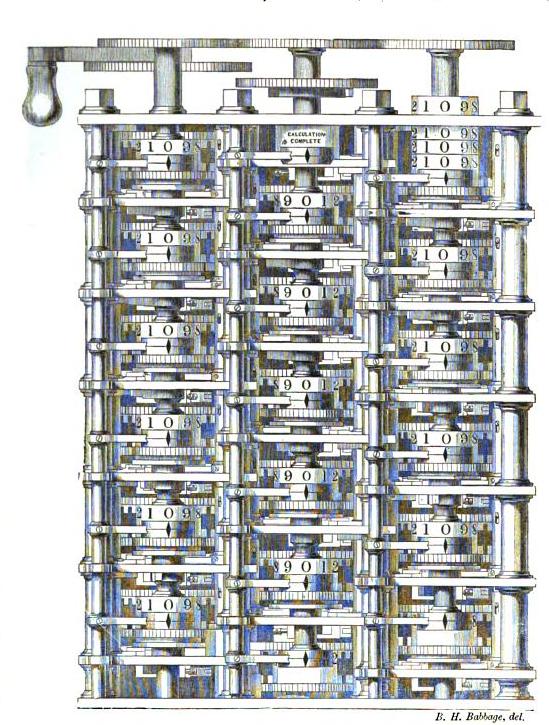

The

The Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution, sometimes divided into the First Industrial Revolution and Second Industrial Revolution, was a transitional period of the global economy toward more widespread, efficient and stable manufacturing processes, succee ...

(late 18th to early 19th century) had a significant impact on the evolution of computing hardware, as the era's rapid advancements in machinery and manufacturing laid the groundwork for mechanized and automated computing. Industrial needs for precise, large-scale calculations—especially in fields such as navigation, engineering, and finance—prompted innovations in both design and function, setting the stage for devices like Charles Babbage's difference engine

A difference engine is an automatic mechanical calculator designed to tabulate polynomial functions. It was designed in the 1820s, and was created by Charles Babbage. The name ''difference engine'' is derived from the method of finite differen ...

(1822). This mechanical device was intended to automate the calculation of polynomial functions and represented one of the earliest applications of computational logic.

Babbage, often regarded as the "father of the computer," envisioned a fully mechanical system of gears and wheels, powered by steam, capable of handling complex calculations that previously required intensive manual labor. His difference engine, designed to aid navigational calculations, ultimately led him to conceive the analytical engine in 1833. This concept, far more advanced than his difference engine, included an arithmetic logic unit

In computing, an arithmetic logic unit (ALU) is a Combinational logic, combinational digital circuit that performs arithmetic and bitwise operations on integer binary numbers. This is in contrast to a floating-point unit (FPU), which operates on ...

, control flow through conditional branching and loops, and integrated memory. Babbage's plans made his analytical engine the first general-purpose design that could be described as Turing-complete

In computability theory, a system of data-manipulation rules (such as a model of computation, a computer's instruction set, a programming language, or a cellular automaton) is said to be Turing-complete or computationally universal if it can be ...

in modern terms.

The analytical engine was programmed using punched cards

A punched card (also punch card or punched-card) is a stiff paper-based medium used to store digital information via the presence or absence of holes in predefined positions. Developed over the 18th to 20th centuries, punched cards were wide ...

, a method adapted from the Jacquard loom

The Jacquard machine () is a device fitted to a loom that simplifies the process of manufacturing textiles with such complex patterns as brocade, damask and matelassé. The resulting ensemble of the loom and Jacquard machine is then called a Jac ...

invented by Joseph Marie Jacquard

Joseph Marie Charles ''dit'' (called or nicknamed) Jacquard (; 7 July 1752 – 7 August 1834) was a French weaver and merchant. He played an important role in the development of the earliest programmable loom (the "Jacquard loom"), which in tur ...

in 1804, which controlled textile patterns with a sequence of punched cards. These cards became foundational in later computing systems as well. Babbage's machine would have featured multiple output devices, including a printer, a curve plotter, and even a bell, demonstrating his ambition for versatile computational applications beyond simple arithmetic.

Ada Lovelace

Augusta Ada King, Countess of Lovelace (''née'' Byron; 10 December 1815 – 27 November 1852), also known as Ada Lovelace, was an English mathematician and writer chiefly known for her work on Charles Babbage's proposed mechanical general-pur ...

expanded on Babbage's vision by conceptualizing algorithms that could be executed by his machine. Her notes on the analytical engine, written in the 1840s, are now recognized as the earliest examples of computer programming. Lovelace saw potential in computers to go beyond numerical calculations, predicting that they might one day generate complex musical compositions or perform tasks like language processing.

Though Babbage's designs were never fully realized due to technical and financial challenges, they influenced a range of subsequent developments in computing hardware. Notably, in the 1890s, Herman Hollerith

Herman Hollerith (February 29, 1860 – November 17, 1929) was a German-American statistician, inventor, and businessman who developed an electromechanical tabulating machine for punched cards to assist in summarizing information and, later, in ...

adapted the idea of punched cards for automated data processing, which was utilized in the U.S. Census and sped up data tabulation significantly, bridging industrial machinery with data processing.

The Industrial Revolution's advancements in mechanical systems demonstrated the potential for machines to conduct complex calculations, influencing engineers like Leonardo Torres Quevedo

Leonardo Torres Quevedo (; 28 December 1852 – 18 December 1936) was a Spanish civil engineer, mathematician and inventor, known for his numerous engineering innovations, including Aerial tramway, aerial trams, airships, catamarans, and remote ...

and Vannevar Bush

Vannevar Bush ( ; March 11, 1890 – June 28, 1974) was an American engineer, inventor and science administrator, who during World War II, World War II headed the U.S. Office of Scientific Research and Development (OSRD), through which almo ...

in the early 20th century. Torres Quevedo designed an electromechanical machine with floating-point arithmetic, while Bush's later work explored electronic digital computing. By the mid-20th century, these innovations paved the way for the first fully electronic computers.

Analog computers

In the first half of the 20th century,

In the first half of the 20th century, analog computer

An analog computer or analogue computer is a type of computation machine (computer) that uses physical phenomena such as Electrical network, electrical, Mechanics, mechanical, or Hydraulics, hydraulic quantities behaving according to the math ...

s were considered by many to be the future of computing. These devices used the continuously changeable aspects of physical phenomena such as electrical

Electricity is the set of physical phenomena associated with the presence and motion of matter possessing an electric charge. Electricity is related to magnetism, both being part of the phenomenon of electromagnetism, as described by Maxwel ...

, mechanical

Mechanical may refer to:

Machine

* Machine (mechanical), a system of mechanisms that shape the actuator input to achieve a specific application of output forces and movement

* Mechanical calculator, a device used to perform the basic operations o ...

, or hydraulic

Hydraulics () is a technology and applied science using engineering, chemistry, and other sciences involving the mechanical properties and use of liquids. At a very basic level, hydraulics is the liquid counterpart of pneumatics, which concer ...

quantities to model

A model is an informative representation of an object, person, or system. The term originally denoted the plans of a building in late 16th-century English, and derived via French and Italian ultimately from Latin , .

Models can be divided in ...

the problem being solved, in contrast to digital computer

A computer is a machine that can be programmed to automatically carry out sequences of arithmetic or logical operations (''computation''). Modern digital electronic computers can perform generic sets of operations known as ''programs'', wh ...

s that represented varying quantities symbolically, as their numerical values change. As an analog computer does not use discrete values, but rather continuous values, processes cannot be reliably repeated with exact equivalence, as they can with Turing machine

A Turing machine is a mathematical model of computation describing an abstract machine that manipulates symbols on a strip of tape according to a table of rules. Despite the model's simplicity, it is capable of implementing any computer algori ...

s.

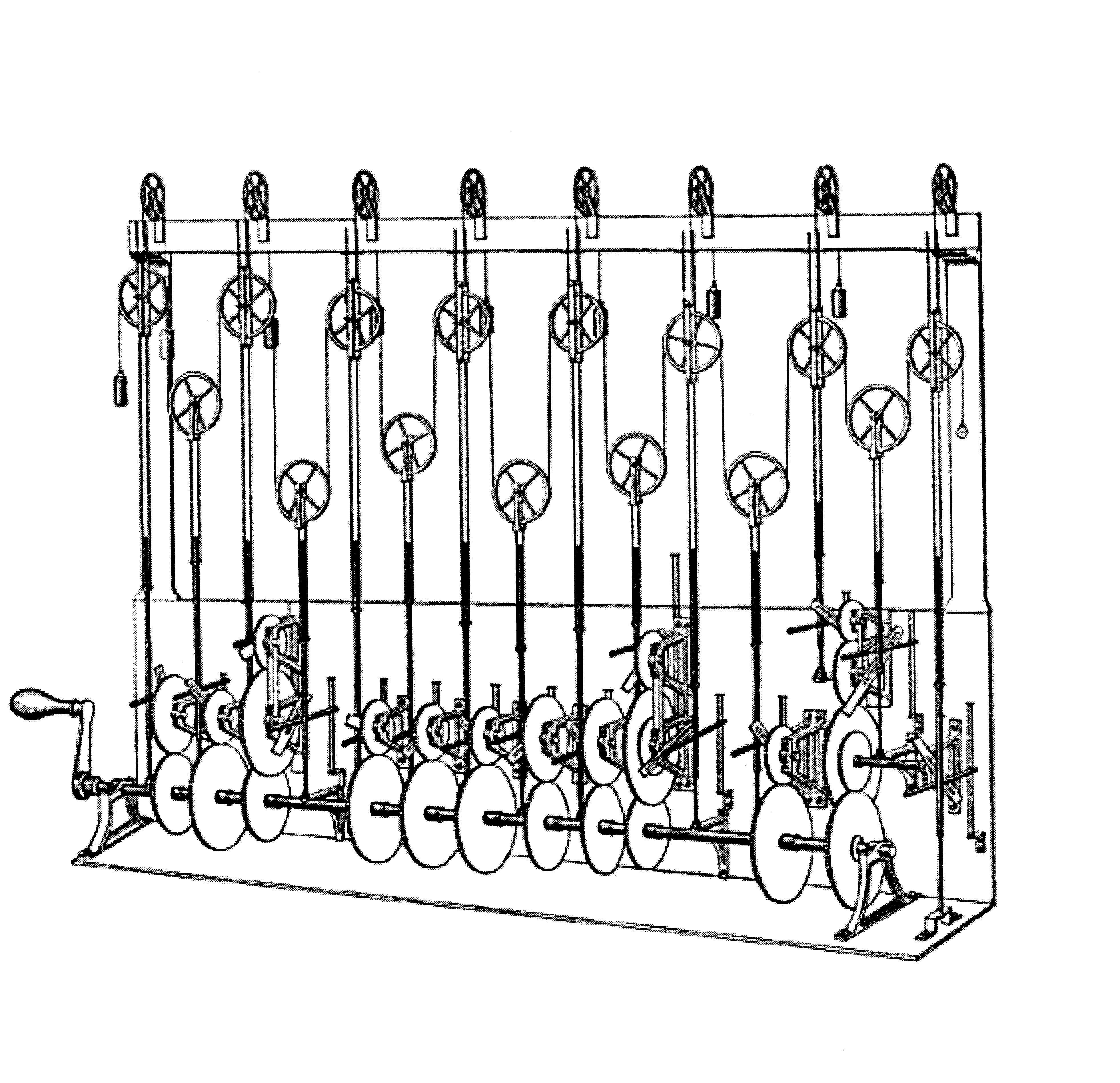

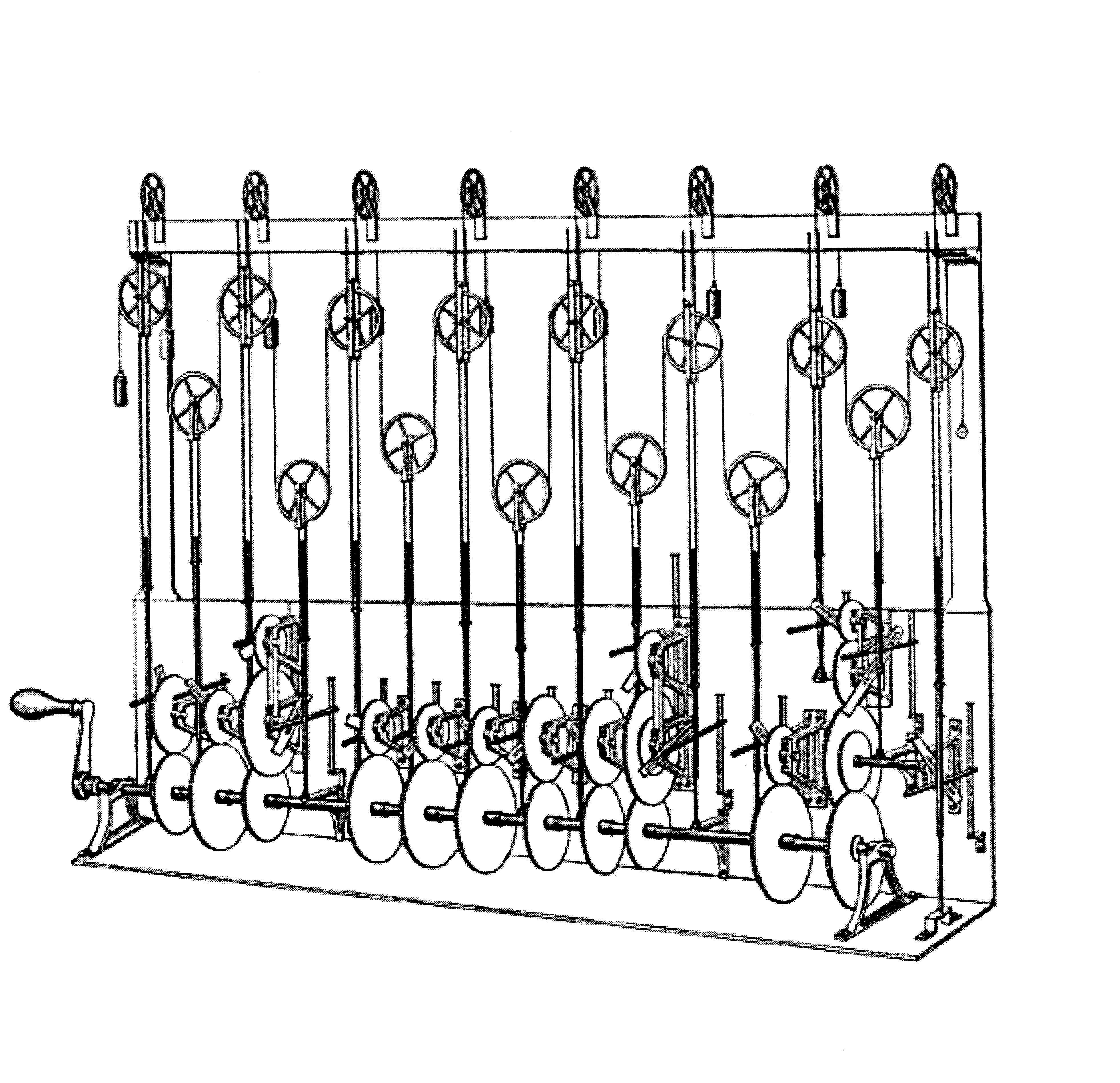

The first modern analog computer was a tide-predicting machine

A tide-predicting machine was a special-purpose mechanical analog computer of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, constructed and set up to predict the ebb and flow of sea tides and the irregular variations in their heights – which chan ...

, invented by Sir William Thomson

William Thomson, 1st Baron Kelvin (26 June 182417 December 1907), was a British mathematician, Mathematical physics, mathematical physicist and engineer. Born in Belfast, he was the Professor of Natural Philosophy (Glasgow), professor of Natur ...

, later Lord Kelvin, in 1872. It used a system of pulleys and wires to automatically calculate predicted tide levels for a set period at a particular location and was of great utility to navigation in shallow waters. His device was the foundation for further developments in analog computing.

The differential analyser

The differential analyser is a mechanical analogue computer designed to solve differential equations by integration, using wheel-and-disc mechanisms to perform the integration. It was one of the first advanced computing devices to be used ope ...

, a mechanical analog computer designed to solve differential equations by integration using wheel-and-disc mechanisms, was conceptualized in 1876 by James Thomson, the brother of the more famous Lord Kelvin. He explored the possible construction of such calculators, but was stymied by the limited output torque of the ball-and-disk integrator

The ball-and-disk integrator is a key component of many advanced mechanical computers. Through simple mechanical means, it performs continual integration of the value of an input. Typical uses were the measurement of area or volume of material in ...

s. In a differential analyzer, the output of one integrator drove the input of the next integrator, or a graphing output.

A notable series of analog calculating machines were developed by Leonardo Torres Quevedo

Leonardo Torres Quevedo (; 28 December 1852 – 18 December 1936) was a Spanish civil engineer, mathematician and inventor, known for his numerous engineering innovations, including Aerial tramway, aerial trams, airships, catamarans, and remote ...

since 1895, including one that was able to compute the roots of arbitrary polynomial

In mathematics, a polynomial is a Expression (mathematics), mathematical expression consisting of indeterminate (variable), indeterminates (also called variable (mathematics), variables) and coefficients, that involves only the operations of addit ...

s of order eight, including the complex ones, with a precision down to thousandths.Leonardo Torres. Memoria sobre las máquinas algébricas: con un informe de la Real academia de ciencias exactas, fisicas y naturales

', Misericordia, 1895.

An important advance in analog computing was the development of the first

An important advance in analog computing was the development of the first fire-control system

A fire-control system (FCS) is a number of components working together, usually a gun data computer, a director and radar, which is designed to assist a ranged weapon system to target, track, and hit a target. It performs the same task as a hum ...

s for long range ship

A ship is a large watercraft, vessel that travels the world's oceans and other Waterway, navigable waterways, carrying cargo or passengers, or in support of specialized missions, such as defense, research and fishing. Ships are generally disti ...

gunlaying. When gunnery ranges increased dramatically in the late 19th century it was no longer a simple matter of calculating the proper aim point, given the flight times of the shells. Various spotters on board the ship would relay distance measures and observations to a central plotting station. There the fire direction teams fed in the location, speed and direction of the ship and its target, as well as various adjustments for Coriolis effect

In physics, the Coriolis force is a pseudo force that acts on objects in motion within a frame of reference that rotates with respect to an inertial frame. In a reference frame with clockwise rotation, the force acts to the left of the moti ...

, weather effects on the air, and other adjustments; the computer would then output a firing solution, which would be fed to the turrets for laying. In 1912, British engineer Arthur Pollen

Arthur Joseph Hungerford Pollen (13 September 1866 – 28 January 1937) was an English journalist, businessman, and commentator on naval affairs who devised a new computerised fire-control system for use on battleships prior to the First World W ...

developed the first electrically powered mechanical analogue computer

An analog computer or analogue computer is a type of computation machine (computer) that uses physical phenomena such as electrical, mechanical, or hydraulic quantities behaving according to the mathematical principles in question (''analog s ...

(called at the time the Argo Clock). It was used by the Imperial Russian Navy

The Imperial Russian Navy () operated as the navy of the Russian Tsardom and later the Russian Empire from 1696 to 1917. Formally established in 1696, it lasted until being dissolved in the wake of the February Revolution and the declaration of ...

in World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

. The alternative Dreyer Table fire control system was fitted to British capital ships by mid-1916.

Mechanical devices were also used to aid the accuracy of aerial bombing. Drift Sight was the first such aid, developed by Harry Wimperis in 1916 for the Royal Naval Air Service

The Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS) was the air arm of the Royal Navy, under the direction of the Admiralty (United Kingdom), Admiralty's Air Department, and existed formally from 1 July 1914 to 1 April 1918, when it was merged with the British ...

; it measured the wind speed

In meteorology, wind speed, or wind flow speed, is a fundamental atmospheric quantity caused by air moving from high to low pressure, usually due to changes in temperature. Wind speed is now commonly measured with an anemometer.

Wind spe ...

from the air, and used that measurement to calculate the wind's effects on the trajectory of the bombs. The system was later improved with the Course Setting Bomb Sight, and reached a climax with World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

bomb sights, Mark XIV bomb sight (RAF Bomber Command

RAF Bomber Command controlled the Royal Air Force's bomber forces from 1936 to 1968. Along with the United States Army Air Forces, it played the central role in the Strategic bombing during World War II#Europe, strategic bombing of Germany in W ...

) and the Norden

Norden is a Scandinavian and German word, directly translated as "the North". It may refer to:

Places England

* Norden, Basingstoke, a ward of Basingstoke and Deane

* Norden, Dorset, a hamlet near Corfe Castle

* Norden, Greater Manchester, a vill ...

(United States Army Air Forces

The United States Army Air Forces (USAAF or AAF) was the major land-based aerial warfare service component of the United States Army and ''de facto'' aerial warfare service branch of the United States during and immediately after World War II ...

).

The art of mechanical analog computing reached its zenith with the differential analyzer

The differential analyser is a mechanical analogue computer designed to solve differential equations by integration, using wheel-and-disc mechanisms to perform the integration. It was one of the first advanced computing devices to be used ope ...

, built by H. L. Hazen and Vannevar Bush

Vannevar Bush ( ; March 11, 1890 – June 28, 1974) was an American engineer, inventor and science administrator, who during World War II, World War II headed the U.S. Office of Scientific Research and Development (OSRD), through which almo ...

at MIT

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) is a private research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States. Established in 1861, MIT has played a significant role in the development of many areas of modern technology and sc ...

starting in 1927, which built on the mechanical integrators of James Thomson and the torque amplifier

A torque amplifier is a mechanical device that amplifies the torque of a rotating shaft without affecting its rotational speed. It is mechanically related to the capstan (nautical), capstan seen on ships. Its most widely known use is in power steer ...

s invented by H. W. Nieman. A dozen of these devices were built before their obsolescence became obvious; the most powerful was constructed at the University of Pennsylvania

The University of Pennsylvania (Penn or UPenn) is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States. One of nine colonial colleges, it was chartered in 1755 through the efforts of f ...

's Moore School of Electrical Engineering

The Moore School of Electrical Engineering was a school at the University of Pennsylvania. The school was integrated into the University of Pennsylvania School of Engineering and Applied Science.

The Moore School came into existence as a resul ...

, where the ENIAC

ENIAC (; Electronic Numerical Integrator and Computer) was the first Computer programming, programmable, Electronics, electronic, general-purpose digital computer, completed in 1945. Other computers had some of these features, but ENIAC was ...

was built.

A fully electronic analog computer was built by Helmut Hölzer

Helmut Hoelzer was a Nazi Germany V-2 rocket engineer who was brought to the United States under Operation Paperclip. Hoelzer was the inventor and constructor of the world's first electronic analog computer.

Life

In October 1939, while working ...

in 1942 at Peenemünde Army Research Center

The Peenemünde Army Research Center (, HVP) was founded in 1937 as one of five military proving grounds under the German Army Weapons Office (''Heereswaffenamt''). Several German guided missiles and rockets of World War II were developed by ...

.

By the 1950s the success of digital electronic computers had spelled the end for most analog computing machines, but hybrid analog computers, controlled by digital electronics, remained in substantial use into the 1950s and 1960s, and later in some specialized applications.

Advent of the digital computer

The principle of the modern computer was first described by computer scientist

The principle of the modern computer was first described by computer scientist Alan Turing

Alan Mathison Turing (; 23 June 1912 – 7 June 1954) was an English mathematician, computer scientist, logician, cryptanalyst, philosopher and theoretical biologist. He was highly influential in the development of theoretical computer ...

, who set out the idea in his seminal 1936 paper, ''On Computable Numbers''. Turing reformulated Kurt Gödel

Kurt Friedrich Gödel ( ; ; April 28, 1906 – January 14, 1978) was a logician, mathematician, and philosopher. Considered along with Aristotle and Gottlob Frege to be one of the most significant logicians in history, Gödel profoundly ...

's 1931 results on the limits of proof and computation, replacing Gödel's universal arithmetic-based formal language with the formal and simple hypothetical devices that became known as Turing machine

A Turing machine is a mathematical model of computation describing an abstract machine that manipulates symbols on a strip of tape according to a table of rules. Despite the model's simplicity, it is capable of implementing any computer algori ...

s. He proved that some such machine would be capable of performing any conceivable mathematical computation if it were representable as an algorithm

In mathematics and computer science, an algorithm () is a finite sequence of Rigour#Mathematics, mathematically rigorous instructions, typically used to solve a class of specific Computational problem, problems or to perform a computation. Algo ...

. He went on to prove that there was no solution to the ''Entscheidungsproblem

In mathematics and computer science, the ; ) is a challenge posed by David Hilbert and Wilhelm Ackermann in 1928. It asks for an algorithm that considers an inputted statement and answers "yes" or "no" according to whether it is universally valid ...

'' by first showing that the halting problem

In computability theory (computer science), computability theory, the halting problem is the problem of determining, from a description of an arbitrary computer program and an input, whether the program will finish running, or continue to run for ...

for Turing machines is undecidable: in general, it is not possible to decide algorithmically whether a given Turing machine will ever halt.

He also introduced the notion of a "universal machine" (now known as a universal Turing machine

In computer science, a universal Turing machine (UTM) is a Turing machine capable of computing any computable sequence, as described by Alan Turing in his seminal paper "On Computable Numbers, with an Application to the Entscheidungsproblem". Co ...

), with the idea that such a machine could perform the tasks of any other machine, or in other words, it is provably capable of computing anything that is computable by executing a program stored on tape, allowing the machine to be programmable. John von Neumann

John von Neumann ( ; ; December 28, 1903 – February 8, 1957) was a Hungarian and American mathematician, physicist, computer scientist and engineer. Von Neumann had perhaps the widest coverage of any mathematician of his time, in ...

acknowledged that the central concept of the modern computer was due to this paper. Turing machines are to this day a central object of study in theory of computation

In theoretical computer science and mathematics, the theory of computation is the branch that deals with what problems can be solved on a model of computation, using an algorithm, how efficiently they can be solved or to what degree (e.g., app ...

. Except for the limitations imposed by their finite memory stores, modern computers are said to be Turing-complete

In computability theory, a system of data-manipulation rules (such as a model of computation, a computer's instruction set, a programming language, or a cellular automaton) is said to be Turing-complete or computationally universal if it can be ...

, which is to say, they have algorithm

In mathematics and computer science, an algorithm () is a finite sequence of Rigour#Mathematics, mathematically rigorous instructions, typically used to solve a class of specific Computational problem, problems or to perform a computation. Algo ...

execution capability equivalent to a universal Turing machine

In computer science, a universal Turing machine (UTM) is a Turing machine capable of computing any computable sequence, as described by Alan Turing in his seminal paper "On Computable Numbers, with an Application to the Entscheidungsproblem". Co ...

.

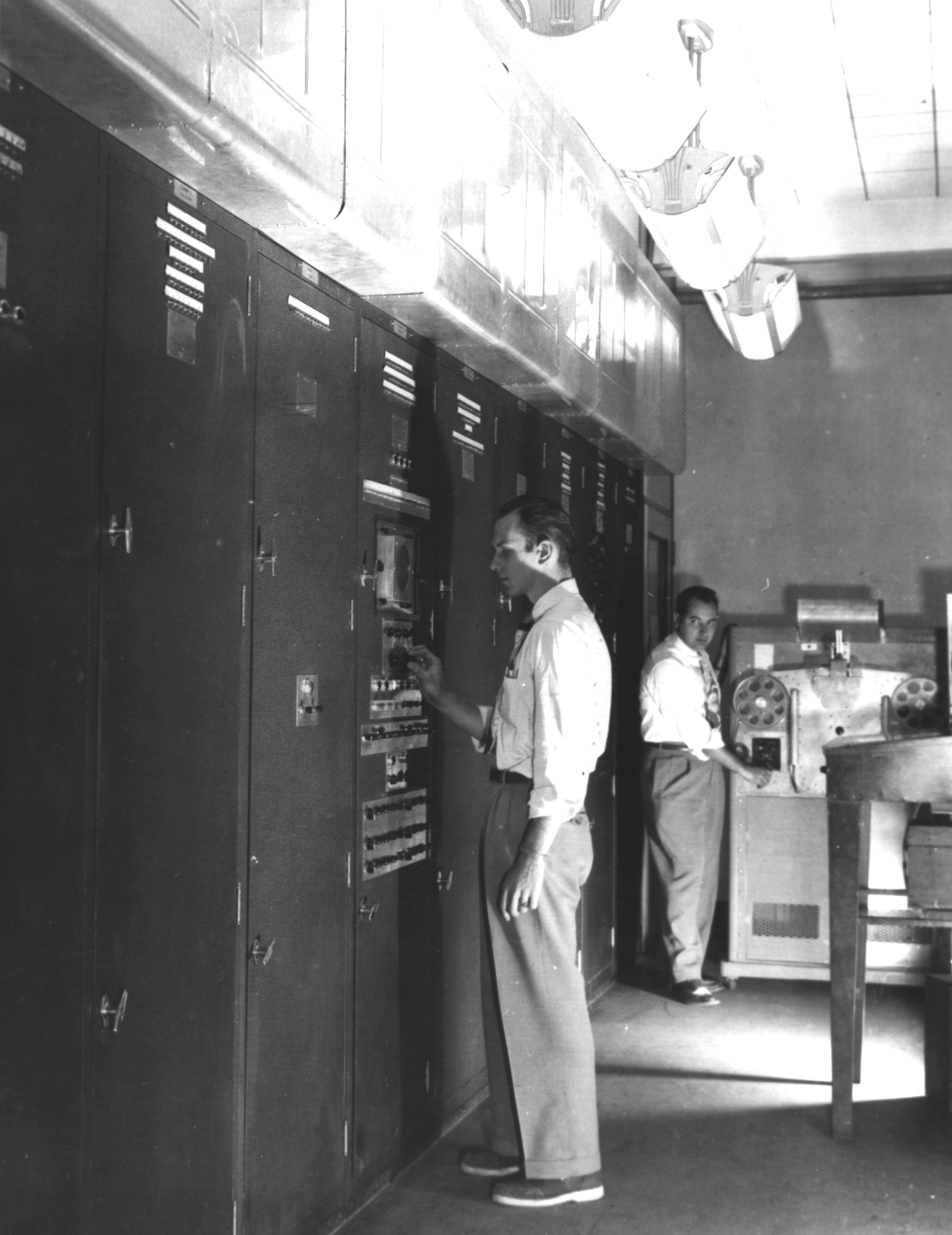

Electromechanical computers

The era of modern computing began with a flurry of development before and during World War II. Most digital computers built in this period were built with electromechanical – electric switches drove mechanical relays to perform the calculation. These mechanical components had a low operating speed due to their mechanical nature and were eventually superseded by much faster all-electric components, originally usingvacuum tube

A vacuum tube, electron tube, thermionic valve (British usage), or tube (North America) is a device that controls electric current flow in a high vacuum between electrodes to which an electric voltage, potential difference has been applied. It ...

s and later transistor

A transistor is a semiconductor device used to Electronic amplifier, amplify or electronic switch, switch electrical signals and electric power, power. It is one of the basic building blocks of modern electronics. It is composed of semicondu ...

s.

The Z2 was one of the earliest examples of an electric operated digital computer

A computer is a machine that can be Computer programming, programmed to automatically Execution (computing), carry out sequences of arithmetic or logical operations (''computation''). Modern digital electronic computers can perform generic set ...

built with electromechanical relays and was created by civil engineer Konrad Zuse

Konrad Ernst Otto Zuse (; ; 22 June 1910 – 18 December 1995) was a German civil engineer, List of pioneers in computer science, pioneering computer scientist, inventor and businessman. His greatest achievement was the world's first programm ...

in 1940 in Germany. It was an improvement on his earlier, mechanical Z1; although it used the same mechanical memory

Memory is the faculty of the mind by which data or information is encoded, stored, and retrieved when needed. It is the retention of information over time for the purpose of influencing future action. If past events could not be remembe ...

, it replaced the arithmetic and control logic with electrical relay

A relay

Electromechanical relay schematic showing a control coil, four pairs of normally open and one pair of normally closed contacts

An automotive-style miniature relay with the dust cover taken off

A relay is an electrically operated switc ...

circuits.

In the same year, electro-mechanical devices called bombe

The bombe () was an Electromechanics, electro-mechanical device used by British cryptologists to help decipher German Enigma machine, Enigma-machine-encrypted secret messages during World War II. The United States Navy, US Navy and United Sta ...

s were built by British cryptologist

This is a list of cryptographers. Cryptography is the practice and study of techniques for secure communication in the presence of third parties called adversaries.

Pre twentieth century

* Al-Khalil ibn Ahmad al-Farahidi: wrote a (now lost) book ...

s to help decipher German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany, the country of the Germans and German things

**Germania (Roman era)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizenship in Germany, see also Ge ...

Enigma-machine-encrypted secret messages during World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

. The bombe's initial design was created in 1939 at the UK Government Code and Cypher School

The Government Code and Cypher School (GC&CS) was a British signals intelligence agency set up in 1919. During the First World War, the British Army and Royal Navy had separate signals intelligence agencies, MI1b and NID25 (initially known as R ...

at Bletchley Park

Bletchley Park is an English country house and Bletchley Park estate, estate in Bletchley, Milton Keynes (Buckinghamshire), that became the principal centre of Allies of World War II, Allied World War II cryptography, code-breaking during the S ...

by Alan Turing

Alan Mathison Turing (; 23 June 1912 – 7 June 1954) was an English mathematician, computer scientist, logician, cryptanalyst, philosopher and theoretical biologist. He was highly influential in the development of theoretical computer ...

, with an important refinement devised in 1940 by Gordon Welchman

William Gordon Welchman OBE (15 June 1906 – 8 October 1985) was an English mathematician. During World War II, he worked at Britain's secret decryption centre at Bletchley Park, where he was one of the most important contributors. In 1948, a ...

. The engineering design and construction was the work of Harold Keen

Harold Hall "Doc" Keen (1894–1973) was a British engineer who produced the engineering design, and oversaw the construction of, the British bombe, a codebreaking machine used in World War II to read German messages sent using the Enigma machi ...

of the British Tabulating Machine Company

__NOTOC__

The British Tabulating Machine Company (BTM) was a firm which manufactured and sold Hollerith unit record equipment and other data-processing equipment. During World War II, BTM constructed some 200 "bombes", machines used at Bletchley ...

. It was a substantial development from a device that had been designed in 1938 by Polish Cipher Bureau cryptologist Marian Rejewski

Marian Adam Rejewski (; 16 August 1905 – 13 February 1980) was a Polish people, Polish mathematician and Cryptography, cryptologist who in late 1932 reconstructed the sight-unseen German military Enigma machine, Enigma cipher machine, aided ...

, and known as the " cryptologic bomb" ( Polish: ''"bomba kryptologiczna"'').

electromechanical

Electromechanics combine processes and procedures drawn from electrical engineering and mechanical engineering. Electromechanics focus on the interaction of electrical and mechanical systems as a whole and how the two systems interact with each ...

programmable, fully automatic digital computer. The Z3 was built with 2000 relay

A relay

Electromechanical relay schematic showing a control coil, four pairs of normally open and one pair of normally closed contacts

An automotive-style miniature relay with the dust cover taken off

A relay is an electrically operated switc ...

s, implementing a 22-bit

The bit is the most basic unit of information in computing and digital communication. The name is a portmanteau of binary digit. The bit represents a logical state with one of two possible values. These values are most commonly represented as ...

word length

In computing, a word is any processor design's natural unit of data. A word is a fixed-sized datum handled as a unit by the instruction set or the hardware of the processor. The number of bits or digits in a word (the ''word size'', ''word wid ...

that operated at a clock frequency

Clock rate or clock speed in computing typically refers to the frequency at which the clock generator of a Microprocessor, processor can generate Clock signal, pulses used to Synchronization (computer science), synchronize the operations of it ...

of about 5–10 Hz. Program code and data were stored on punched film

A film, also known as a movie or motion picture, is a work of visual art that simulates experiences and otherwise communicates ideas, stories, perceptions, emotions, or atmosphere through the use of moving images that are generally, sinc ...

. It was quite similar to modern machines in some respects, pioneering numerous advances such as floating-point numbers

In computing, floating-point arithmetic (FP) is arithmetic on subsets of real numbers formed by a ''significand'' (a signed sequence of a fixed number of digits in some base) multiplied by an integer power of that base.

Numbers of this form ...

. Replacement of the hard-to-implement decimal system (used in Charles Babbage

Charles Babbage (; 26 December 1791 – 18 October 1871) was an English polymath. A mathematician, philosopher, inventor and mechanical engineer, Babbage originated the concept of a digital programmable computer.

Babbage is considered ...

's earlier design) by the simpler binary

Binary may refer to:

Science and technology Mathematics

* Binary number, a representation of numbers using only two values (0 and 1) for each digit

* Binary function, a function that takes two arguments

* Binary operation, a mathematical op ...

system meant that Zuse's machines were easier to build and potentially more reliable, given the technologies available at that time. The Z3 was proven to have been a Turing-complete machine in 1998 by Raúl Rojas

Raúl Rojas González (born 1955, in Mexico City) is a Mexican emeritus professor of Computer Science and Mathematics at the Free University of Berlin, and a renowned specialist in artificial neural networks. The FU-Fighters, football-playing ...

. In two 1936 patent

A patent is a type of intellectual property that gives its owner the legal right to exclude others from making, using, or selling an invention for a limited period of time in exchange for publishing an sufficiency of disclosure, enabling discl ...

applications, Zuse also anticipated that machine instructions could be stored in the same storage used for data—the key insight of what became known as the von Neumann architecture

The von Neumann architecture—also known as the von Neumann model or Princeton architecture—is a computer architecture based on the '' First Draft of a Report on the EDVAC'', written by John von Neumann in 1945, describing designs discus ...

, first implemented in 1948 in America in the electromechanical

Electromechanics combine processes and procedures drawn from electrical engineering and mechanical engineering. Electromechanics focus on the interaction of electrical and mechanical systems as a whole and how the two systems interact with each ...

IBM SSEC and in Britain in the fully electronic Manchester Baby

The Manchester Baby, also called the Small-Scale Experimental Machine (SSEM), was the first electronic stored-program computer. It was built at the University of Manchester by Frederic Calland Williams, Frederic C. Williams, Tom Kilburn, and Ge ...

.

Zuse suffered setbacks during World War II when some of his machines were destroyed in the course of Allied bombing campaigns. Apparently his work remained largely unknown to engineers in the UK and US until much later, although at least IBM was aware of it as it financed his post-war startup company in 1946 in return for an option on Zuse's patents.

In 1944, the Harvard Mark I

The Harvard Mark I, or IBM Automatic Sequence Controlled Calculator (ASCC), was one of the earliest general-purpose electromechanical computers used in the war effort during the last part of World War II.

One of the first programs to run on th ...

was constructed at IBM's Endicott laboratories. It was a similar general purpose electro-mechanical computer to the Z3, but was not quite Turing-complete.

Digital computation

The term digital was first suggested by George Robert Stibitz and refers to where a signal, such as a voltage, is not used to directly represent a value (as it would be in ananalog computer

An analog computer or analogue computer is a type of computation machine (computer) that uses physical phenomena such as Electrical network, electrical, Mechanics, mechanical, or Hydraulics, hydraulic quantities behaving according to the math ...

), but to encode it. In November 1937, Stibitz, then working at Bell Labs (1930–1941), completed a relay-based calculator he later dubbed the " Model K" (for "kitchen table", on which he had assembled it), which became the first binary adder

Binary may refer to:

Science and technology Mathematics

* Binary number, a representation of numbers using only two values (0 and 1) for each digit

* Binary function, a function that takes two arguments

* Binary operation, a mathematical op ...

. Typically signals have two states – low (usually representing 0) and high (usually representing 1), but sometimes three-valued logic

In logic, a three-valued logic (also trinary logic, trivalent, ternary, or trilean, sometimes abbreviated 3VL) is any of several many-valued logic systems in which there are three truth values indicating ''true'', ''false'', and some third value ...

is used, especially in high-density memory. Modern computers generally use binary logic, but many early machines were decimal computer

A decimal computer is a computer that represents and operates on numbers and addresses in decimal format instead of binary as is common in most modern computers. Some decimal computers had a variable word length, which enabled operations on r ...

s. In these machines, the basic unit of data was the decimal digit, encoded in one of several schemes, including binary-coded decimal

In computing and electronic systems, binary-coded decimal (BCD) is a class of binary encodings of decimal numbers where each digit is represented by a fixed number of bits, usually four or eight. Sometimes, special bit patterns are used f ...

or BCD, bi-quinary, excess-3

Excess-3, 3-excess or 10-excess-3 binary code (often abbreviated as XS-3, 3XS or X3), shifted binary or Stibitz code (after George Stibitz, who built a relay-based adding machine in 1937) is a self-complementary binary-coded decimal (BCD) code ...

, and two-out-of-five code

A two-out-of-five code is a constant-weight code that provides exactly ten possible combinations of two bits, and is thus used for representing the decimal digits using five bits. Each bit is assigned a weight, such that the set bits sum to the ...

.

The mathematical basis of digital computing is Boolean algebra

In mathematics and mathematical logic, Boolean algebra is a branch of algebra. It differs from elementary algebra in two ways. First, the values of the variable (mathematics), variables are the truth values ''true'' and ''false'', usually denot ...

, developed by the British mathematician George Boole

George Boole ( ; 2 November 1815 – 8 December 1864) was a largely self-taught English mathematician, philosopher and logician, most of whose short career was spent as the first professor of mathematics at Queen's College, Cork in Ireland. H ...

in his work ''The Laws of Thought

''An Investigation of the Laws of Thought: on Which are Founded the Mathematical Theories of Logic and Probabilities'' by George Boole, published in 1854, is the second of Boole's two monographs on algebraic logic. Boole was a professor of mathe ...

'', published in 1854. His Boolean algebra was further refined in the 1860s by William Jevons

William Stanley Jevons (; 1 September 1835 – 13 August 1882) was an English economist and logician.

Irving Fisher described Jevons's book ''A General Mathematical Theory of Political Economy'' (1862) as the start of the mathematical method i ...

and Charles Sanders Peirce

Charles Sanders Peirce ( ; September 10, 1839 – April 19, 1914) was an American scientist, mathematician, logician, and philosopher who is sometimes known as "the father of pragmatism". According to philosopher Paul Weiss (philosopher), Paul ...

, and was first presented systematically by Ernst Schröder and A. N. Whitehead. In 1879 Gottlob Frege developed the formal approach to logic and proposes the first logic language for logical equations.

In the 1930s and working independently, American electronic engineer

Electronic engineering is a sub-discipline of electrical engineering that emerged in the early 20th century and is distinguished by the additional use of active components such as semiconductor devices to amplify and control electric current flow ...

Claude Shannon

Claude Elwood Shannon (April 30, 1916 – February 24, 2001) was an American mathematician, electrical engineer, computer scientist, cryptographer and inventor known as the "father of information theory" and the man who laid the foundations of th ...

and Soviet logician

Logic is the study of correct reasoning. It includes both formal and informal logic. Formal logic is the study of deductively valid inferences or logical truths. It examines how conclusions follow from premises based on the structure of arg ...

Victor Shestakov both showed a one-to-one correspondence