Polish–Russian War (1609–1618) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Polish–Russian War was a conflict fought between the

ImageSize = width:500 height:100

PlotArea = left:65 right:15 bottom:20 top:5

AlignBars = justify

Colors =

id:godunovb value:rgb(0.99215,0.8,0.54)

id:godunovf value:rgb(1,0.7019,0)

id:dimitryi value:rgb(1,1,0)

id:szhujskiy value:rgb(1,1,0.702)

id:vladislav value:rgb(1,0.922,0.384)

id:romanov value:rgb(1,0.922,0.675)

Period = from:1600 till:1615

TimeAxis = orientation:horizontal

ScaleMajor = unit:year increment:1 start:1600

PlotData=

align:center textcolor:black fontsize:8 mark:(line,black) width:35 shift:(0,-5)

from:start till: 1605 text:"

In the late 16th and early 17th centuries,  In late 1600, a Polish

In late 1600, a Polish

For most of the 17th century, Sigismund III was occupied with internal problems of his own, like the Nobles' Rebellion in the Commonwealth and the wars with Sweden and in Moldavia. However, the impostor

For most of the 17th century, Sigismund III was occupied with internal problems of his own, like the Nobles' Rebellion in the Commonwealth and the wars with Sweden and in Moldavia. However, the impostor  Dmitry attracted a number of followers, formed a small army, and, supported by approximately 3500 soldiers of the Commonwealth magnates' private armies and the mercenaries bought by Dmitriy's own cash, rode to Russia in June 1604. Some of Godunov's other enemies, including approximately 2,000 southern

Dmitry attracted a number of followers, formed a small army, and, supported by approximately 3500 soldiers of the Commonwealth magnates' private armies and the mercenaries bought by Dmitriy's own cash, rode to Russia in June 1604. Some of Godunov's other enemies, including approximately 2,000 southern

Tsar Vasili Shuyski was unpopular and weak in Russia and his reign was far from stable. He was perceived as anti-Polish; he had led the coup against the first False Dmitry, killing over 500 Polish soldiers in Moscow and imprisoning a Polish envoy. The civil war raged on, as in 1607 the False Dmitry II appeared, again supported by some Polish

Tsar Vasili Shuyski was unpopular and weak in Russia and his reign was far from stable. He was perceived as anti-Polish; he had led the coup against the first False Dmitry, killing over 500 Polish soldiers in Moscow and imprisoning a Polish envoy. The civil war raged on, as in 1607 the False Dmitry II appeared, again supported by some Polish

In 1609 the Zebrzydowski Rebellion ended when Tsar Vasili signed a military alliance with

In 1609 the Zebrzydowski Rebellion ended when Tsar Vasili signed a military alliance with

/ref> Some Russian boyars assured Sigismund of their support by offering the throne to his son, Prince Wladislaus IV of Poland, Władysław. Previously, Sigismund had been unwilling to commit the majority of Polish forces or his time to the internal conflict in Russia, but in 1609 those factors made him re-evaluate and drastically change his policy. Although many Polish nobles and soldiers were fighting for the second False Dmitry at the time, Sigismund III and the troops under his command did not support Dimitriy for the throne – Sigismund wanted Russia himself. The entry of Sigismund into Russia caused the majority of the Polish supporters of False Dmitry II to desert him and contributed to his defeat. A series of subsequent disasters induced False Dmitry II to flee his camp disguised as a peasant and to go to Kostroma together with Marina. Dmitry made another unsuccessful attack on Moscow, and, supported by the

Hetman Żółkiewski, whose only other choice was mutiny, decided to follow the king's orders and left Smolensk in 1610, leaving only a smaller force necessary to continue the siege. With Cossack reinforcements, he marched on Moscow. However, as he feared and predicted, as the Polish–Lithuanian forces pressed eastwards, ravaging Russian lands, and as Sigismund's lack of willingness to compromise became more and more apparent, many supporters of the Poles and of the second False Dmitry left the pro-Polish camp and turned to Shuyski's anti-Polish faction.

Russian forces under Grigory Voluyev were coming to relieve Smolensk and fortified the fort at Tsaryovo-Zaymishche (Carowo, Cariewo, Tsarovo–Zajmiszcze) to bar the Poles' advance on Moscow. The Siege of Tsaryovo began on 24 June. However, the Russians were not prepared for a long siege and had little food and water inside the fort. Voluyev sent word for Dmitry Shuyski (Tsar Shuyski's brother) to come to their aid and lift the siege. Shuyski's troops marched for Tsaryovo, not by the direct route, but round-about through Klushino, hoping to come to Tsaryovo by the back route. Shuyski received aid from Swedish forces under the command of Jacob Pontusson De la Gardie.

Żółkiewski learned of Shuyski's relief force and divided his troops to meet the Russians before they could come to Tsaryovo and lift the siege. He left at night so that Voluyev would not notice his absence. The combined Russian and Swedish armies were defeated on 4 July 1610 at the

Hetman Żółkiewski, whose only other choice was mutiny, decided to follow the king's orders and left Smolensk in 1610, leaving only a smaller force necessary to continue the siege. With Cossack reinforcements, he marched on Moscow. However, as he feared and predicted, as the Polish–Lithuanian forces pressed eastwards, ravaging Russian lands, and as Sigismund's lack of willingness to compromise became more and more apparent, many supporters of the Poles and of the second False Dmitry left the pro-Polish camp and turned to Shuyski's anti-Polish faction.

Russian forces under Grigory Voluyev were coming to relieve Smolensk and fortified the fort at Tsaryovo-Zaymishche (Carowo, Cariewo, Tsarovo–Zajmiszcze) to bar the Poles' advance on Moscow. The Siege of Tsaryovo began on 24 June. However, the Russians were not prepared for a long siege and had little food and water inside the fort. Voluyev sent word for Dmitry Shuyski (Tsar Shuyski's brother) to come to their aid and lift the siege. Shuyski's troops marched for Tsaryovo, not by the direct route, but round-about through Klushino, hoping to come to Tsaryovo by the back route. Shuyski received aid from Swedish forces under the command of Jacob Pontusson De la Gardie.

Żółkiewski learned of Shuyski's relief force and divided his troops to meet the Russians before they could come to Tsaryovo and lift the siege. He left at night so that Voluyev would not notice his absence. The combined Russian and Swedish armies were defeated on 4 July 1610 at the  After the news of Klushino spread, support for Tsar Shuyski almost completely evaporated. Żółkiewski soon convinced the Russian units at Tsaryovo, which were much stronger than the ones at Kłuszyn, to capitulate and to swear an oath of loyalty to Władysław. Then he incorporated them into his army and moved towards Moscow. In August 1610 many Russian

After the news of Klushino spread, support for Tsar Shuyski almost completely evaporated. Żółkiewski soon convinced the Russian units at Tsaryovo, which were much stronger than the ones at Kłuszyn, to capitulate and to swear an oath of loyalty to Władysław. Then he incorporated them into his army and moved towards Moscow. In August 1610 many Russian  In the meantime, Żółkiewski and the second False Dmitriy, formerly reluctant allies, began to part ways. The second False Dmitry had lost much of his influence over the Polish court, and Żółkiewski would eventually try to drive Dmitry from the capital. Żółkiewski soon began manoeuvring for a tsar of Polish origin, particularly the 15-year-old Prince Władysław. The boyars had offered the throne to Władysław at least twice, in the hopes of having the liberal Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth end the

In the meantime, Żółkiewski and the second False Dmitriy, formerly reluctant allies, began to part ways. The second False Dmitry had lost much of his influence over the Polish court, and Żółkiewski would eventually try to drive Dmitry from the capital. Żółkiewski soon began manoeuvring for a tsar of Polish origin, particularly the 15-year-old Prince Władysław. The boyars had offered the throne to Władysław at least twice, in the hopes of having the liberal Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth end the

A 1611 uprising in Moscow against the Polish garrison marked the end of Russian tolerance for the Commonwealth intervention. The citizens of Moscow had voluntarily participated in the coup in 1606, killing 500 Polish soldiers. Now, ruled by the Poles, they once again revolted. The Moscow burghers took over the munition store, but Polish troops defeated the first wave of attackers, and the fighting resulted in a large fire that consumed part of Moscow. From July onward the situation of the Commonwealth forces became grave, as the uprising turned into a siege of the Polish-held Kremlin. Reportedly, the Poles had imprisoned the leader of the Orthodox Church, Patriarch Hermogenes. When the Russians attacked Moscow, the Poles ordered him, as the man with the most authority with the Russians at the time, to sign a statement to call off the attack. Hermogenes refused and was starved to death. The Polish Kremlin garrison then found itself besieged.

In the meantime, in late 1611, prince

A 1611 uprising in Moscow against the Polish garrison marked the end of Russian tolerance for the Commonwealth intervention. The citizens of Moscow had voluntarily participated in the coup in 1606, killing 500 Polish soldiers. Now, ruled by the Poles, they once again revolted. The Moscow burghers took over the munition store, but Polish troops defeated the first wave of attackers, and the fighting resulted in a large fire that consumed part of Moscow. From July onward the situation of the Commonwealth forces became grave, as the uprising turned into a siege of the Polish-held Kremlin. Reportedly, the Poles had imprisoned the leader of the Orthodox Church, Patriarch Hermogenes. When the Russians attacked Moscow, the Poles ordered him, as the man with the most authority with the Russians at the time, to sign a statement to call off the attack. Hermogenes refused and was starved to death. The Polish Kremlin garrison then found itself besieged.

In the meantime, in late 1611, prince  Russian reinforcements under Prince Pozharsky eventually starved the Commonwealth garrison (there were reports of

Russian reinforcements under Prince Pozharsky eventually starved the Commonwealth garrison (there were reports of  On 2 June 1611 Smolensk had finally fallen to the Poles. After enduring 20 months of siege, two harsh winters and dwindling food supplies, the Russians in Smolensk finally reached their limit as the Polish–Lithuanian troops broke through the city gates. The Polish army, advised by the runaway traitor Andrei Dedishin, discovered a weakness in the fortress defenses, and on 13 June 1611 Cavalier of Malta Bartłomiej Nowodworski inserted a mine into a sewer canal. The explosion created a large breach in the fortress walls. The fortress fell on the same day. The remaining 3,000 Russian defenders took refuge in the Assumption Cathedral and blew themselves up with stores of gunpowder to avoid death at the hands of the invaders. Although it was a blow to lose Smolensk, the defeat freed up Russian troops to fight the Commonwealth in Moscow, and the Russian commander at Smolensk, Mikhail Borisovich Shein, was considered a hero for holding out as long as he had. He was captured at Smolensk and remained a prisoner of Poland–Lithuania for the next nine years.

On 2 June 1611 Smolensk had finally fallen to the Poles. After enduring 20 months of siege, two harsh winters and dwindling food supplies, the Russians in Smolensk finally reached their limit as the Polish–Lithuanian troops broke through the city gates. The Polish army, advised by the runaway traitor Andrei Dedishin, discovered a weakness in the fortress defenses, and on 13 June 1611 Cavalier of Malta Bartłomiej Nowodworski inserted a mine into a sewer canal. The explosion created a large breach in the fortress walls. The fortress fell on the same day. The remaining 3,000 Russian defenders took refuge in the Assumption Cathedral and blew themselves up with stores of gunpowder to avoid death at the hands of the invaders. Although it was a blow to lose Smolensk, the defeat freed up Russian troops to fight the Commonwealth in Moscow, and the Russian commander at Smolensk, Mikhail Borisovich Shein, was considered a hero for holding out as long as he had. He was captured at Smolensk and remained a prisoner of Poland–Lithuania for the next nine years.

After the fall of Smolensk, the Russo-Polish border remained relatively quiet for the next few years. However, no official treaty was signed. Sigismund, criticized by the

After the fall of Smolensk, the Russo-Polish border remained relatively quiet for the next few years. However, no official treaty was signed. Sigismund, criticized by the  While both countries were shaken by internal strife, many smaller factions thrived. Polish

While both countries were shaken by internal strife, many smaller factions thrived. Polish

Eventually the Commonwealth Sejm voted to raise the funds necessary to resume large scale military operations. The final attempt by Sigismund and Władysław to gain the throne was a new campaign launched on 6 April 1617. Władysław was the nominal commander, but it was hetman Chodkiewicz who had actual control over the army. In October, the towns of

Eventually the Commonwealth Sejm voted to raise the funds necessary to resume large scale military operations. The final attempt by Sigismund and Władysław to gain the throne was a new campaign launched on 6 April 1617. Władysław was the nominal commander, but it was hetman Chodkiewicz who had actual control over the army. In October, the towns of

In the end, Sigismund did not succeed in becoming tsar or in securing the throne for Władysław, but he was able to expand the Commonwealth's territory. During his reign Poland-Lithuania was the largest and most populous country in Europe. On 11 December 1618 the

In the end, Sigismund did not succeed in becoming tsar or in securing the throne for Władysław, but he was able to expand the Commonwealth's territory. During his reign Poland-Lithuania was the largest and most populous country in Europe. On 11 December 1618 the

The story of the Dymitriads and False Dimitrys proved useful to future generations of rulers and politicians in Poland and Russia, and a distorted version of the real events gained much fame in Russia, as well as in Poland. In Poland the Dmitriads campaign is remembered as the height of the Polish Golden Age, the time Poles captured Moscow, something that even four million troops from

The story of the Dymitriads and False Dimitrys proved useful to future generations of rulers and politicians in Poland and Russia, and a distorted version of the real events gained much fame in Russia, as well as in Poland. In Poland the Dmitriads campaign is remembered as the height of the Polish Golden Age, the time Poles captured Moscow, something that even four million troops from

Polacy na Kremlu

Tygodnik "Wprost", Nr 1182 (31 lipca 2005), , accessed on 29 July 2005 *

Polish occupation of Russia

(archived 10 October 2003) {{DEFAULTSORT:Polish-Muscovite War (1605-18) 1600s in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth 1600s in Russia 1610s in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth 1610s in Russia 17th-century conflicts Invasions of Russia Wars involving the Tsardom of Russia Wars involving the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth Polish–Russian wars Warfare of the early modern period Wars of succession involving the states and peoples of Europe Time of Troubles

Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, also referred to as Poland–Lithuania or the First Polish Republic (), was a federation, federative real union between the Crown of the Kingdom of Poland, Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania ...

and the Tsardom of Russia

The Tsardom of Russia, also known as the Tsardom of Moscow, was the centralized Russian state from the assumption of the title of tsar by Ivan the Terrible, Ivan IV in 1547 until the foundation of the Russian Empire by Peter the Great in 1721.

...

from 1609 to 1618.

Russia had been experiencing the Time of Troubles

The Time of Troubles (), also known as Smuta (), was a period of political crisis in Tsardom of Russia, Russia which began in 1598 with the death of Feodor I of Russia, Feodor I, the last of the Rurikids, House of Rurik, and ended in 1613 wit ...

since the death of Tsar Feodor I

Feodor I Ioannovich () or Fyodor I Ivanovich (; 31 May 1557 – 17 January 1598), nicknamed the Blessed (), was Tsar of all Russia from 1584 until his death in 1598.

Feodor's mother died when he was three, and he grew up in the shadow of his ...

in 1598, which caused political instability

Political decay is a political theory, originally described in 1965 by Samuel P. Huntington, which describes how chaos and disorder can arise from social modernization increasing more rapidly than political and institutional modernization. Huntin ...

and a violent succession crisis A succession crisis is a crisis that arises when an order of succession fails, for example when a monarch dies without an indisputable heir. It may result in a war of succession.

Examples include (see List of wars of succession):

* The Wars of Th ...

upon the extinction of the Rurik dynasty

The Rurik dynasty, also known as the Rurikid or Riurikid dynasty, as well as simply Rurikids or Riurikids, was a noble lineage allegedly founded by the Varangian prince Rurik, who, according to tradition, established himself at Novgorod in the ...

; furthermore, a major famine

A famine is a widespread scarcity of food caused by several possible factors, including, but not limited to war, natural disasters, crop failure, widespread poverty, an Financial crisis, economic catastrophe or government policies. This phenom ...

ravaged the country from 1601 to 1603. Poland exploited Russia's civil wars when powerful members of the Polish ''szlachta

The ''szlachta'' (; ; ) were the nobility, noble estate of the realm in the Kingdom of Poland, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, and the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. Depending on the definition, they were either a warrior "caste" or a social ...

'' began influencing Russian boyar

A boyar or bolyar was a member of the highest rank of the feudal nobility in many Eastern European states, including Bulgaria, Kievan Rus' (and later Russia), Moldavia and Wallachia (and later Romania), Lithuania and among Baltic Germans. C ...

s and supporting successive pretenders to the title of tsar of Russia against the crowned tsar

Tsar (; also spelled ''czar'', ''tzar'', or ''csar''; ; ; sr-Cyrl-Latn, цар, car) is a title historically used by Slavic monarchs. The term is derived from the Latin word '' caesar'', which was intended to mean ''emperor'' in the Euro ...

s Boris Godunov

Boris Feodorovich Godunov (; ; ) was the ''de facto'' regent of Russia from 1585 to 1598 and then tsar from 1598 to 1605 following the death of Feodor I, the last of the Rurik dynasty. After the end of Feodor's reign, Russia descended into t ...

() and Vasili IV Shuysky (). From 1605, Polish nobles conducted a series of skirmishes until the death of False Dmitry I

False Dmitry I or Pseudo-Demetrius I () reigned as the Tsar of all Russia from 10 June 1605 until his death on 17 May 1606 under the name of Dmitriy Ivanovich (). According to historian Chester S.L. Dunning, Dmitry was "the only Tsar ever raise ...

in 1606, and they invaded again in 1607 until Russia formed a military alliance with Sweden two years later. The King of Poland, Sigismund III Vasa

Sigismund III Vasa (, ; 20 June 1566 – 30 April 1632

N.S.) was King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania from 1587 to 1632 and, as Sigismund, King of Sweden from 1592 to 1599. He was the first Polish sovereign from the House of Vasa. Re ...

, declared war on Russia in response in 1609, aiming to gain territorial concessions and to weaken Sweden's ally. Polish forces won many early victories such as the 1610 Battle of Klushino

The Battle of Klushino, or the Battle of Kłuszyn, was fought on 4 July 1610, between forces of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth and the Tsardom of Russia during the Polish–Russian War, part of Russia's Time of Troubles. The battle occu ...

. In 1610, Polish units entered Moscow and Sweden withdrew from the military alliance with Russia, instead triggering the Ingrian War

The Ingrian War () was a conflict fought between the Swedish Empire and the Tsardom of Russia which lasted between 1610 and 1617. It can be seen as part of Russia's Time of Troubles, and is mainly remembered for the attempt to put a Swedish duk ...

of 1610-1617 between Sweden and Russia.

Sigismund's son, Prince Władysław of Poland, was elected tsar of Russia by the Seven Boyars

The Seven Boyars () were a group of Russian nobles who deposed Tsar Vasili Shuisky on and later that year, after Russia lost the Battle of Klushino during the Polish–Russian War, acquiesced to the Polish–Lithuanian occupation of Moscow.

The ...

in September 1610, but Sigismund refused to allow his son to become the new tsar unless the Muscovites agreed to convert from Eastern Orthodoxy

Eastern Orthodoxy, otherwise known as Eastern Orthodox Christianity or Byzantine Christianity, is one of the three main Branches of Christianity, branches of Chalcedonian Christianity, alongside Catholic Church, Catholicism and Protestantism ...

to Catholicism

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

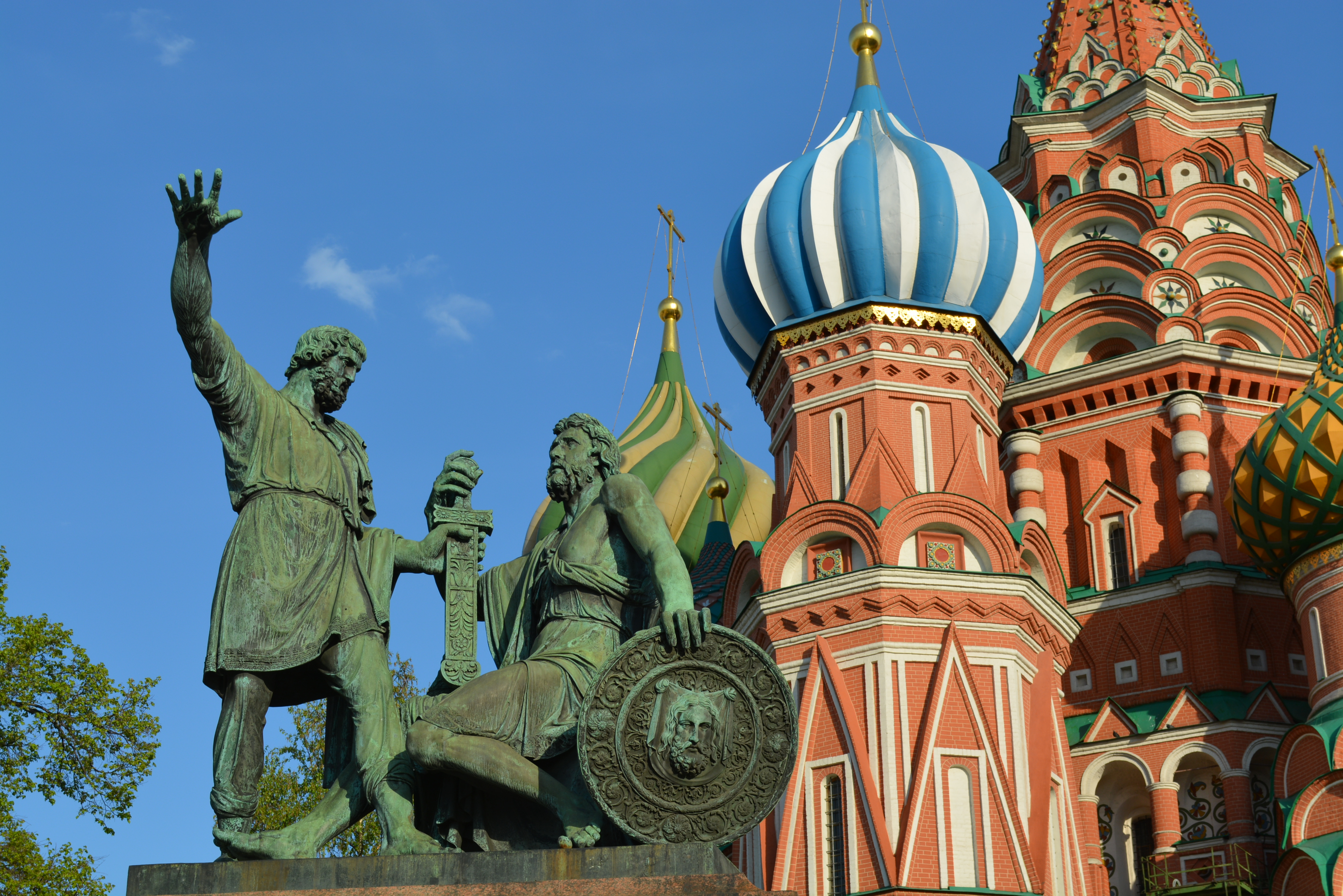

, and the pro-Polish boyars ended their support for the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. In 1611, Kuzma Minin

Kuzma Minin (), full name Kuzma Minich Zakhariev-Sukhoruky (; – May 21, 1616), was a Russian merchant who, together with Prince Dmitry Pozharsky, formed the popular uprising in Nizhny Novgorod against the Polish–Lithuanian occupation of Mosc ...

and Prince Dmitry Pozharsky

Dmitry Mikhaylovich Pozharsky ( rus, Дми́трий Миха́йлович Пожа́рский, p=ˈdmʲitrʲɪj mʲɪˈxajləvʲɪtɕ pɐˈʐarskʲɪj; 17 October 1577 – 30 April 1642) was a Tsardom of Russia, Russian prince known for his ...

formed a new army to launch a popular revolt

This is a chronological list of revolts organized by peasants.

Background

The history of peasant wars spans over two thousand years. A variety of factors fueled the emergence of the peasant revolt phenomenon, including:

* Tax resistance

* So ...

against the Polish occupation. The Poles captured Smolensk in June 1611, but began to retreat after they were ousted from Moscow in September 1612. In March 1613 the Russian Zemsky Sobor elected Michael Romanov

Michael I (; ) was Tsar of all Russia from 1613 after being elected by the Zemsky Sobor of 1613 until his death in 1645. He was elected by the Zemsky Sobor and was the first tsar of the House of Romanov, which succeeded the House of Rurik.

...

, the son of Patriarch Filaret of Moscow

Feodor Nikitich Romanov (, ; 1553 – 1 October 1633) was a Russian boyar who after temporary disgrace rose to become patriarch of Moscow as Filaret (, ), and became de facto ruler of Russia during the reign of his son, Mikhail Feodorovich.

B ...

, as tsar of Russia, thus inaugurating the Romanov dynasty

The House of Romanov (also transliterated as Romanoff; , ) was the reigning imperial house of Russia from 1613 to 1917. They achieved prominence after Anastasia Romanovna married Ivan the Terrible, the first crowned tsar of all Russia. Ni ...

and ending the Time of Troubles. With little military action between 1612 and 1617, the war finally ended in 1618 with the Truce of Deulino

The Truce of Deulino (also known as Peace or Treaty of Dywilino) concluded the Polish–Russian War of 1609–1618 between the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth and the Tsardom of Russia. It was signed in the village of on 11 December 1618 and t ...

, which granted the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth certain territorial concessions but preserved Russia's independence.

The war was the first major sign of the rivalry and uneasy relations between Poland and Russia which would last for centuries. Its aftermath had a long-lasting impact on Russian society, fostering a negative stereotype of Poland among Russians and, most notably, giving rise to the Romanov dynasty which ruled Russia for three centuries until the February Revolution

The February Revolution (), known in Soviet historiography as the February Bourgeois Democratic Revolution and sometimes as the March Revolution or February Coup was the first of Russian Revolution, two revolutions which took place in Russia ...

in 1917. It also left a noticeable mark on Russian culture, with renowned writers and composers portraying the war in works such as the play ''Boris Godunov'' by Alexander Pushkin

Alexander Sergeyevich Pushkin () was a Russian poet, playwright, and novelist of the Romantic era.Basker, Michael. Pushkin and Romanticism. In Ferber, Michael, ed., ''A Companion to European Romanticism''. Oxford: Blackwell, 2005. He is consid ...

(adapted into an opera by Modest Mussorgsky

Modest Petrovich Mussorgsky (; ; ; – ) was a Russian composer, one of the group known as "The Five (composers), The Five." He was an innovator of Music of Russia, Russian music in the Romantic music, Romantic period and strove to achieve a ...

), other operas including ''A Life for the Tsar

''A Life for the Tsar'' ( ) is a "patriotic-heroic tragic" opera in four acts with an epilogue by Mikhail Glinka. During the Soviet era the opera was known under the name '' Ivan Susanin'' ( ), due to the anti-monarchist censorship.

The original ...

'' by Mikhail Glinka

Mikhail Ivanovich Glinka ( rus, links=no, Михаил Иванович Глинка, Mikhail Ivanovich Glinka, mʲɪxɐˈil ɨˈvanəvʲɪdʑ ˈɡlʲinkə, Ru-Mikhail-Ivanovich-Glinka.ogg; ) was the first Russian composer to gain wide recognit ...

and '' Pan Voyevoda'' by Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov

Nikolai Andreyevich Rimsky-Korsakov. At the time, his name was spelled , which he romanized as Nicolas Rimsky-Korsakow; the BGN/PCGN transliteration of Russian is used for his name here; ALA-LC system: , ISO 9 system: .. (18 March 1844 – 2 ...

as well as films such as ''Minin and Pozharsky'' (1939) and ''1612'' (2007).

Name

In Polishhistoriography

Historiography is the study of the methods used by historians in developing history as an academic discipline. By extension, the term ":wikt:historiography, historiography" is any body of historical work on a particular subject. The historiog ...

, two military interventions immediately preceding the war, the aim of which was to place a tsar loyal to the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth on the Russian throne are called the '' Dimitriads'' and are considered a separate conflict: the ''First Dymitriad'' (1604–1606) and ''Second Dymitriad'' (1607–1609). The ''Polish–Russian War'' (1609–1618) can subsequently be divided into two wars of 1609–1611 and 1617–1618, and may or may not include the 1617–1618 campaign, which is sometimes referred to as ''Chodkiewicz uscoviteCampaign''. According to Russian historiography, the chaotic events of the war fall into the "Time of Troubles

The Time of Troubles (), also known as Smuta (), was a period of political crisis in Tsardom of Russia, Russia which began in 1598 with the death of Feodor I of Russia, Feodor I, the last of the Rurikids, House of Rurik, and ended in 1613 wit ...

". The conflict with Poles is commonly called the ''Polish Invasion'', ''Polish Intervention'', or more specifically the ''Polish Intervention of the Early Seventeenth Century''.

Background

Prelude to invasions

Boris Godunov

Boris Feodorovich Godunov (; ; ) was the ''de facto'' regent of Russia from 1585 to 1598 and then tsar from 1598 to 1605 following the death of Feodor I, the last of the Rurik dynasty. After the end of Feodor's reign, Russia descended into t ...

" color:godunovb

# fontsize:6

from:1605 till: 1605.5 text:" Feodor II" shift:(-30,10) color:godunovf

from:1605.5 till: 1606.4 text:"False Dmitry I

False Dmitry I or Pseudo-Demetrius I () reigned as the Tsar of all Russia from 10 June 1605 until his death on 17 May 1606 under the name of Dmitriy Ivanovich (). According to historian Chester S.L. Dunning, Dmitry was "the only Tsar ever raise ...

" shift:(17,-15) color:dimitryi

# fontsize:8

from:1606.4 till: 1610.7 text:" Vasili IV" color:szhujskiy

from:1610.7 till: 1613 text:" Vladislav IV" color:vladislav

from:1613 till:end text:"Michael I Michael I may refer to:

* Pope Michael I of Alexandria, Coptic Pope of Alexandria and Patriarch of the See of St. Mark in 743–767

* Michael I Rangabe, Byzantine Emperor (died in 844)

* Michael I Cerularius, Patriarch Michael I of Constantinop ...

" color:romanov

Russia

Russia, or the Russian Federation, is a country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia. It is the list of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the world, and extends across Time in Russia, eleven time zones, sharing Borders ...

was in a state of political and economic crisis. After the death of Tsar Ivan IV

Ivan IV Vasilyevich (; – ), commonly known as Ivan the Terrible,; ; monastic name: Jonah. was Grand Prince of Moscow and all Russia from 1533 to 1547, and the first Tsar and Grand Prince of all Russia from 1547 until his death in 1584. ...

("the Terrible") in 1584, and the death of his son Dimitri

Dimitri, Dimitry, Demetri or variations thereof may refer to: __NOTOC__

People Given name

* Dimitri (clown), Swiss clown and mime Dimitri Jakob Muller (1935–2016)

* Dimitri Atanasescu (1836–1907), Ottoman-born Aromanian teacher

* Dimitri Ayo ...

in 1591, several factions competed for the tsar's throne. In 1598, Boris Godunov

Boris Feodorovich Godunov (; ; ) was the ''de facto'' regent of Russia from 1585 to 1598 and then tsar from 1598 to 1605 following the death of Feodor I, the last of the Rurik dynasty. After the end of Feodor's reign, Russia descended into t ...

was crowned to the Russian throne, marking the end of the centuries long rule of the Rurik dynasty

The Rurik dynasty, also known as the Rurikid or Riurikid dynasty, as well as simply Rurikids or Riurikids, was a noble lineage allegedly founded by the Varangian prince Rurik, who, according to tradition, established himself at Novgorod in the ...

. While his policies were rather moderate and well-intentioned, his rule was marred by the general perception of its questionable legitimacy and allegations of his involvement in orchestrating the assassination of Dimitri. While Godunov managed to put the opposition to his rule under control, he did not manage to crush it completely. To add to his troubles, the first years of the 17th century were exceptionally cold. The drop in temperature was felt all over the world and was most likely caused by a severe eruption of a volcano in South America. In Russia, it resulted in a great famine that swept through the country from 1601 to 1603.

In late 1600, a Polish

In late 1600, a Polish diplomatic mission

A diplomatic mission or foreign mission is a group of people from a state or organization present in another state to represent the sending state or organization officially in the receiving or host state. In practice, the phrase usually denotes ...

led by Chancellor Lew Sapieha

Lew Sapieha (; ; 4 April 1557 – 7 July 1633) was a nobleman and statesman of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. He became Great Secretary of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania in 1580, Great Clerk of the Grand Duchy in 1581, Crown Chancellor in 1 ...

with Eliasz Pielgrzymowski and Stanisław Warszycki arrived in Moscow and proposed an alliance between the Commonwealth and Russia, which would include a future personal union

A personal union is a combination of two or more monarchical states that have the same monarch while their boundaries, laws, and interests remain distinct. A real union, by contrast, involves the constituent states being to some extent in ...

. They proposed that after one monarch's death without heirs, the other would become the ruler of both countries. However, Tsar Godunov declined the union proposal and settled on extending the Treaty of Jam Zapolski, which ended the Lithuanian wars of the 16th century, by 22 years (to 1622).

Sigismund and the Commonwealth magnates knew full well that they were not capable of any serious invasion of Russia; the Commonwealth army was too small, its treasury always empty, and the war lacked popular support. However, as the situation in Russia deteriorated, Sigismund and many Commonwealth magnate

The term magnate, from the late Latin ''magnas'', a great man, itself from Latin ''magnus'', "great", means a man from the higher nobility, a man who belongs to the high office-holders or a man in a high social position, by birth, wealth or ot ...

s, especially those with estates and forces near the Russian border, began to look for a way to profit from the chaos and weakness of their eastern neighbour. This proved easy, as in the meantime many Russian boyar

A boyar or bolyar was a member of the highest rank of the feudal nobility in many Eastern European states, including Bulgaria, Kievan Rus' (and later Russia), Moldavia and Wallachia (and later Romania), Lithuania and among Baltic Germans. C ...

s, disgruntled by the ongoing civil war, tried to entice various neighbors, including the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, into intervening. Some of them looked to their own profits, trying to organize support for their own ascension to the Russian throne. Others looked to their western neighbor, the Commonwealth, and its attractive Golden Freedom

Golden Liberty (; , ), sometimes referred to as Golden Freedoms, Nobles' Democracy or Nobles' Commonwealth ( or ''Złota wolność szlachecka'') was a political system in the Kingdom of Poland and, after the Union of Lublin (1569), in the Polish ...

s, and together with some Polish politicians planned for some kind of union between those two states. Yet others tried to tie their fates with that of Sweden in what became known as the De la Gardie Campaign and the Ingrian War

The Ingrian War () was a conflict fought between the Swedish Empire and the Tsardom of Russia which lasted between 1610 and 1617. It can be seen as part of Russia's Time of Troubles, and is mainly remembered for the attempt to put a Swedish duk ...

.

Advocates for a union of Poland–Lithuania with Russia proposed a plan similar to the original Polish–Lithuanian Union of Lublin

The Union of Lublin (; ) was signed on 1 July 1569 in Lublin, Poland, and created a single state, the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, one of the largest countries in Europe at the time. It replaced the personal union of the Crown of the Kingd ...

involving a common foreign policy and military; the right for nobility to choose the place where they would live and to buy landed estates; removal of barriers for trade and transit; introduction of a single currency; increased religious tolerance in Russia (especially the right to build churches of non-Orthodox faiths); and the sending of boyar children for education in more developed Polish academies (like the Jagiellonian University

The Jagiellonian University (, UJ) is a public research university in Kraków, Poland. Founded in 1364 by Casimir III the Great, King Casimir III the Great, it is the oldest university in Poland and one of the List of oldest universities in con ...

). However, this project never gained much support. Many boyars feared that the union with the predominantly Catholic Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania would endanger Russia's Orthodox traditions and opposed anything that threatened Russian culture, especially the policies aimed at curtailing the influence of the Orthodox Church, intermarriage and education in Polish schools that had already led to successful Polonization

Polonization or Polonisation ()In Polish historiography, particularly pre-WWII (e.g., L. Wasilewski. As noted in Смалянчук А. Ф. (Smalyanchuk 2001) Паміж краёвасцю і нацыянальнай ідэяй. Польскі ...

of the Ruthenian lands under Polish control.

Polish invasion (1605–1606)

For most of the 17th century, Sigismund III was occupied with internal problems of his own, like the Nobles' Rebellion in the Commonwealth and the wars with Sweden and in Moldavia. However, the impostor

For most of the 17th century, Sigismund III was occupied with internal problems of his own, like the Nobles' Rebellion in the Commonwealth and the wars with Sweden and in Moldavia. However, the impostor False Dmitry I

False Dmitry I or Pseudo-Demetrius I () reigned as the Tsar of all Russia from 10 June 1605 until his death on 17 May 1606 under the name of Dmitriy Ivanovich (). According to historian Chester S.L. Dunning, Dmitry was "the only Tsar ever raise ...

appeared in Poland in 1603 and soon found enough support among powerful magnates such as Michał Wiśniowiecki

Michał Wiśniowiecki (; died 1616) was a Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth szlachcic, prince at Wiśniowiec, magnate, son of Michał Wiśniowiecki (1529-1584), Michał Wiśniowiecki, grandfather of future Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth monarch, ...

, Lew, and Jan Piotr Sapieha

Jan Piotr Sapieha (English: ''John Peter Sapieha'', 1569–1611) was a Polish-Lithuanian nobleman, general, politician, diplomat, governor of Uświat county, member of the Parliament and a skilled commander of the Polish troops stationing in th ...

, who provided him with funds for a campaign against Godunov. Commonwealth magnates looked forward to material gains from the campaign and control over Russia through False Dmitriy. In addition, both Polish magnates and Russian boyars advanced plans for a union between the Commonwealth and Russia, similar to the one Lew Sapieha had discussed in 1600 (when the idea had been dismissed by Godunov). Finally, the proponents of Catholicism saw in Dmitry a tool to spread the influence of their Church eastwards, and after promises of a united Catholic dominated Russo-Polish entity waging a war on the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

, Jesuit

The Society of Jesus (; abbreviation: S.J. or SJ), also known as the Jesuit Order or the Jesuits ( ; ), is a religious order (Catholic), religious order of clerics regular of pontifical right for men in the Catholic Church headquartered in Rom ...

s also provided him with funds and education. Although Sigismund declined to support Dmitry officially with the full might of the Commonwealth, the Polish king was always happy to support pro-Catholic initiatives and provided him with the sum of 4,000 zlotys–enough for a few hundred soldiers. Nonetheless, some of Dmitriy's supporters, especially among those involved in the rebellion

Rebellion is an uprising that resists and is organized against one's government. A rebel is a person who engages in a rebellion. A rebel group is a consciously coordinated group that seeks to gain political control over an entire state or a ...

, actively worked to have Dmitry replace Sigismund. In exchange, in June 1604 Dmitry promised the Commonwealth "half of Smolensk

Smolensk is a city and the administrative center of Smolensk Oblast, Russia, located on the Dnieper River, west-southwest of Moscow.

First mentioned in 863, it is one of the oldest cities in Russia. It has been a regional capital for most of ...

territory". Many were skeptical about the future of this endeavor. Jan Zamoyski

Jan Sariusz Zamoyski (; 19 March 1542 – 3 June 1605) was a Polish nobleman, magnate, statesman and the 1st '' ordynat'' of Zamość. He served as the Royal Secretary from 1565, Deputy Chancellor from 1576, Grand Chancellor of the Crown f ...

, opposed to most of Sigismund's policies, later referred to the entire False Dmitry I affair as a "comedy worthy of Plautus

Titus Maccius Plautus ( ; 254 – 184 BC) was a Roman playwright of the Old Latin period. His comedies are the earliest Latin literary works to have survived in their entirety. He wrote Palliata comoedia, the genre devised by Livius Andro ...

or Terentius".

When Boris Godunov

Boris Feodorovich Godunov (; ; ) was the ''de facto'' regent of Russia from 1585 to 1598 and then tsar from 1598 to 1605 following the death of Feodor I, the last of the Rurik dynasty. After the end of Feodor's reign, Russia descended into t ...

heard about the pretender, he claimed that the man was just a runaway monk called Grigory Otrepyev, although on what information he based this claim is unclear. Godunov's support among the Russians began to wane, especially when he tried to spread counter-rumors. Some of the Russian boyar

A boyar or bolyar was a member of the highest rank of the feudal nobility in many Eastern European states, including Bulgaria, Kievan Rus' (and later Russia), Moldavia and Wallachia (and later Romania), Lithuania and among Baltic Germans. C ...

s also claimed to accept Dmitry as such support gave them legitimate reasons not to pay taxes to Godunov.

Dmitry attracted a number of followers, formed a small army, and, supported by approximately 3500 soldiers of the Commonwealth magnates' private armies and the mercenaries bought by Dmitriy's own cash, rode to Russia in June 1604. Some of Godunov's other enemies, including approximately 2,000 southern

Dmitry attracted a number of followers, formed a small army, and, supported by approximately 3500 soldiers of the Commonwealth magnates' private armies and the mercenaries bought by Dmitriy's own cash, rode to Russia in June 1604. Some of Godunov's other enemies, including approximately 2,000 southern Cossack

The Cossacks are a predominantly East Slavic Eastern Christian people originating in the Pontic–Caspian steppe of eastern Ukraine and southern Russia. Cossacks played an important role in defending the southern borders of Ukraine and Rus ...

s, joined Dimitry's forces on his way to Moscow. Dmitriy's forces fought two engagements with reluctant Russian soldiers; his army won the first at Novhorod-Siverskyi

Novhorod-Siverskyi (, , , ''Novgorod-Severskiy''), historically known as Novhorod-Siversk () or Novgorod-Seversk (), is a historic city in Chernihiv Oblast, northern Ukraine. It serves as the administrative center of Novhorod-Siverskyi Raion, alth ...

, soon capturing Chernigov

Chernihiv (, ; , ) is a city and municipality in northern Ukraine, which serves as the administrative center of Chernihiv Oblast and Chernihiv Raion within the oblast. Chernihiv's population is

The city was designated as a Hero City of Ukrain ...

, Putivl, Sevsk Sevsk () is the name of several inhabited localities in Russia.

;Urban localities

*Sevsk, Bryansk Oblast, a town in Sevsky District of Bryansk Oblast;

;Rural localities

* Sevsk, Kemerovo Oblast, a settlement in Burlakovskaya Rural Territory of Pr ...

, and Kursk

Kursk (, ) is a types of inhabited localities in Russia, city and the administrative center of Kursk Oblast, Russia, located at the confluence of the Kur (Kursk Oblast), Kur, Tuskar, and Seym (river), Seym rivers. It has a population of

Kursk ...

, but badly lost the second Battle of Dobrynichi and nearly disintegrated. Dmitry's cause was only saved by the news of the death of Tsar Boris Godunov.

The sudden death of the Tsar on 13 April 1605 removed the main barrier to further advances by Dimitry. Russian troops began to defect to his side, and, on 1 June, boyars in Moscow imprisoned the newly crowned tsar, Boris's son Feodor II, and the boy's mother, later brutally murdering them. On 20 June the impostor made his triumphal entry into Moscow, and on 21 July he was crowned Tsar by a new Patriarch

The highest-ranking bishops in Eastern Orthodoxy, Oriental Orthodoxy, the Roman Catholic Church (above major archbishop and primate), the Hussite Church, Church of the East, and some Independent Catholic Churches are termed patriarchs (and ...

of his own choosing, the Greek Cypriot

Greek Cypriots (, ) are the ethnic Greek population of Cyprus, forming the island's largest ethnolinguistic community. According to the 2023 census, 719,252 respondents recorded their ethnicity as Greek, forming almost 99% of the 737,196 Cypri ...

Patriarch Ignatius, who as bishop of Ryazan

Ryazan (, ; also Riazan) is the largest types of inhabited localities in Russia, city and administrative center of Ryazan Oblast, Russia. The city is located on the banks of the Oka River in Central Russia, southeast of Moscow. As of the 2010 C ...

had been the first church leader to recognize Dmitry as Tsar. The alliance with Poland was furthered by Dimitriy's marriage ('' per procura'' in Kraków

, officially the Royal Capital City of Kraków, is the List of cities and towns in Poland, second-largest and one of the oldest cities in Poland. Situated on the Vistula River in Lesser Poland Voivodeship, the city has a population of 804,237 ...

) with the daughter of Jerzy Mniszech

Jerzy Mniszech (c. 1548 – 1613) was a Polish nobleman and diplomat in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. Member of the House of Mniszech. Krajczy koronny in 1574, castellan of Radom in 1583, voivode of Sandomierz Voivodship in 1590, ...

, Marina Mniszech

Marina Mniszech or Mnishek (, ; , ; – 24 December 1614) was a Polish noblewoman who was the tsaritsa of all Russia in May 1606 during the Time of Troubles as the wife of False Dmitry I. Following the death of her husband, she later married ...

, a Polish noblewoman with whom Dmitry had fallen in love while in Poland. The new Tsarina outraged many Russians by refusing to convert from Catholicism to the Russian Orthodox faith. Commonwealth king Sigismund was a prominent guest at this wedding. Marina soon left to join her husband in Moscow, where she was crowned a Tsarina in May.

While Dmitry's rule itself was nondescript and devoid of significant blunders, his position was weak. Many boyars felt they could gain more influence, even the throne, for themselves, and many were still wary of Polish cultural influence, especially in view of Dmitriy's court being increasingly dominated by the aliens he brought with himself from Poland. The Golden Freedoms

Golden Liberty (; , ), sometimes referred to as Golden Freedoms, Nobles' Democracy or Nobles' Commonwealth ( or ''Złota wolność szlachecka'') was a political system in the Kingdom of Poland and, after the Union of Lublin (1569), in the Polish ...

, declaring all nobility equal, that were supported by lesser nobility, threatened the most powerful of the boyars. Thus the boyars, headed by Prince Vasily Shuyski, began to plot against Dmitry and his pro-Polish faction, accusing him of homosexuality, spreading Roman Catholicism

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

and Polish customs, and selling Russia to Jesuits

The Society of Jesus (; abbreviation: S.J. or SJ), also known as the Jesuit Order or the Jesuits ( ; ), is a religious order (Catholic), religious order of clerics regular of pontifical right for men in the Catholic Church headquartered in Rom ...

and the Pope. They gained popular support, especially as Dmitry was visibly supported by a few hundred irregular Commonwealth forces, which still garrisoned Moscow, and often engaged in various criminal acts, angering the local population.

On the morning of 17 May 1606, about two weeks after the marriage, conspirators stormed the Kremlin

The Moscow Kremlin (also the Kremlin) is a fortified complex in Moscow, Russia. Located in the centre of the country's capital city, the Moscow Kremlin comprises five palaces, four cathedrals, and the enclosing Kremlin Wall along with the K ...

. Dmitry tried to flee through a window but broke his leg in the fall. One of the plotters shot him dead on the spot. At first, the body was put on display, but it was later cremated; the ashes were reportedly shot from a cannon toward Poland. Dmitriy's reign had lasted a mere ten months. Vasili Shuyski took his place as Tsar. About five hundred of Dmitriy's Commonwealth supporters were killed, imprisoned, or forced to leave Russia.

Second Polish invasion (1607–1609)

Tsar Vasili Shuyski was unpopular and weak in Russia and his reign was far from stable. He was perceived as anti-Polish; he had led the coup against the first False Dmitry, killing over 500 Polish soldiers in Moscow and imprisoning a Polish envoy. The civil war raged on, as in 1607 the False Dmitry II appeared, again supported by some Polish

Tsar Vasili Shuyski was unpopular and weak in Russia and his reign was far from stable. He was perceived as anti-Polish; he had led the coup against the first False Dmitry, killing over 500 Polish soldiers in Moscow and imprisoning a Polish envoy. The civil war raged on, as in 1607 the False Dmitry II appeared, again supported by some Polish magnate

The term magnate, from the late Latin ''magnas'', a great man, itself from Latin ''magnus'', "great", means a man from the higher nobility, a man who belongs to the high office-holders or a man in a high social position, by birth, wealth or ot ...

s and 'recognized' by Marina Mniszech as her first husband. This brought him the support of the magnates of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth who had supported False Dmitry I before. Adam Wiśniowiecki

Adam Wiśniowiecki (c. 1566 – 1622) Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth szlachcic and magnate. Supported False Dmitriy I during the Muscovy Time of Troubles, famous, together with Konstanty Wiśniowiecki (1564-1641), for being the 'finders' of ...

, Roman Różyński, Jan Piotr Sapieha

Jan Piotr Sapieha (English: ''John Peter Sapieha'', 1569–1611) was a Polish-Lithuanian nobleman, general, politician, diplomat, governor of Uświat county, member of the Parliament and a skilled commander of the Polish troops stationing in th ...

decided to support the second pretender as well, supplying him with some early funds and about 7,500 soldiers. The pillaging of his army, especially of the Lisowczycy

Lisowczyks or Lisowczycy (; also known as ''Straceńcy'' ('lost men' or 'forlorn hope') or (company of ); or in singular form: Lisowczyk or ) was the name of an early 17th-century irregular unit of the Polish–Lithuanian light cavalry. The Lis ...

mercenaries

A mercenary is a private individual who joins an War, armed conflict for personal profit, is otherwise an outsider to the conflict, and is not a member of any other official military. Mercenaries fight for money or other forms of payment rath ...

led by Aleksander Lisowski, contributed to the placard in Sergiyev Posad

Sergiyev Posad ( rus, Сергиев Посад, p=ˈsʲɛrgʲɪ(j)ɪf pɐˈsat) is a city that is the administrative center of Sergiyevo-Posadsky District in Moscow Oblast, Russia. Population:

The city contains the Trinity Lavra of St. Sergi ...

: "three plagues: typhus

Typhus, also known as typhus fever, is a group of infectious diseases that include epidemic typhus, scrub typhus, and murine typhus. Common symptoms include fever, headache, and a rash. Typically these begin one to two weeks after exposu ...

, Tatars

Tatars ( )Tatar

in the Collins English Dictionary are a group of Turkic peoples across Eas ...

and Poles". In 1608 together with Aleksander Kleczkowski, Lisowczycy, leading a few hundred in the Collins English Dictionary are a group of Turkic peoples across Eas ...

Don Cossack

Don Cossacks (, ) or Donians (, ), are Cossacks who settled along the middle and lower Don. Historically, they lived within the former Don Cossack Host (, ), which was either an independent or an autonomous democratic republic in present-da ...

s working for the Commonwealth, ragtag szlachta

The ''szlachta'' (; ; ) were the nobility, noble estate of the realm in the Kingdom of Poland, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, and the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. Depending on the definition, they were either a warrior "caste" or a social ...

and mercenaries, defeated the army of tsar Vasili Shuyski led by Zakhary Lyapunov

Zakhary Petrovich Lyapunov () (? - after 1612) was a Russian political figure of the early 17th century, brother of Prokopy Lyapunov.

Biography

In 1605, Zakhary Lyapunov took the side of False Dmitri I. Upon the latter's death in 1606, he to ...

and Ivan Khovansky at the Battle of Zaraysk and captured Mikhailov and Kolomna

Kolomna (, ) is a historic types of inhabited localities in Russia, city in Moscow Oblast, Russia, situated at the confluence of the Moskva River, Moskva and Oka Rivers, (by rail) southeast of Moscow. Population:

History

Mentioned for the fir ...

. Then Lisowczycy advanced towards Moscow but was defeated by Vasiliy Buturlin at the Battle of Medvezhiy Brod, losing most of his plunder. When Polish commander Jan Piotr Sapieha

Jan Piotr Sapieha (English: ''John Peter Sapieha'', 1569–1611) was a Polish-Lithuanian nobleman, general, politician, diplomat, governor of Uświat county, member of the Parliament and a skilled commander of the Polish troops stationing in th ...

failed to win the siege of Troitse-Sergiyeva Lavra, Lisowczycy retreated to the vicinity of Rakhmantsevo. Soon, however, came successes (pillages) at Kostroma

Kostroma (, ) is a historic city and the administrative center of Kostroma Oblast, Russia. A part of the Golden Ring of Russian cities, it is located at the confluence of the rivers Volga and Kostroma. In the 2021 census, the population is 267, ...

, Soligalich

Soligalich () is a town and the administrative center of Soligalichsky District in Kostroma Oblast, Russia, located on the right bank of the Kostroma River. Population:

History

It originated as an important center of saltworks, which suppli ...

, and some other cities.

Dmitry speedily captured Karachev

Karachev () is a types of inhabited localities in Russia, town and the administrative center of Karachevsky District in Bryansk Oblast, Russia. Population:

History

First chronicled in 1146, it was the capital of one of the Upper Oka Principal ...

, Bryansk

Bryansk (, ) is a types of inhabited localities in Russia, city and the administrative center of Bryansk Oblast, Russia, situated on the Desna (river), Desna River, southwest of Moscow. It has a population of 379,152 at the 2021 census.

Bryans ...

, and other towns. He was reinforced by the Poles, and in the spring of 1608 advanced upon Moscow, routing the army of Tsar Vasily Shuyski at Bolkhov

Bolkhov () is a town and the administrative center of Bolkhovsky District in Oryol Oblast, Russia, located on the Nugr River ( Oka's tributary), from Oryol, the administrative center of the oblast. Population: 12,800 (1969); 20,703 (1897). ...

. Dmitry's promises of the wholesale confiscation of the estates of the boyars drew many common people to his side. The village of Tushino

Tushino ( rus, Тушино, p=ˈtuʂɨnə) is a former village and town to the north of Moscow, which has been part of the city's area since 1960. Between 1939 and 1960, Tushino was classed as a separate town. The Skhodnya River flows across the ...

, about twelve kilometers from the capital, was converted into an armed camp, where Dmitry gathered his army. His forces initially included 7,000 Polish soldiers, 10,000 Cossacks, and 10,000 other soldiers, including former members of the failed rokosz of Zebrzydowski, but his force grew gradually in power, and soon exceeded 100,000 men. He raised another illustrious captive, Feodor Romanov, to the rank of Patriarch

The highest-ranking bishops in Eastern Orthodoxy, Oriental Orthodoxy, the Roman Catholic Church (above major archbishop and primate), the Hussite Church, Church of the East, and some Independent Catholic Churches are termed patriarchs (and ...

, enthroning him as Patriarch Filaret, and won the allegiance of the cities of Yaroslavl

Yaroslavl (; , ) is a city and the administrative center of Yaroslavl Oblast, Russia, located northeast of Moscow. The historic part of the city is a World Heritage Site, and is located at the confluence of the Volga and the Kotorosl rivers. ...

, Kostroma

Kostroma (, ) is a historic city and the administrative center of Kostroma Oblast, Russia. A part of the Golden Ring of Russian cities, it is located at the confluence of the rivers Volga and Kostroma. In the 2021 census, the population is 267, ...

, Vologda

Vologda (, ) is a types of inhabited localities in Russia, city and the administrative center of Vologda Oblast, Russia, located on the river Vologda (river), Vologda within the watershed of the Northern Dvina. Population:

The city serves as ...

, Kashin, and several others. However, his fortunes were soon to reverse, as the Commonwealth decided to take a more active stance in the Russian civil wars.

War (1609–1618)

Polish victories (1609–1610)

In 1609 the Zebrzydowski Rebellion ended when Tsar Vasili signed a military alliance with

In 1609 the Zebrzydowski Rebellion ended when Tsar Vasili signed a military alliance with Charles IX of Sweden

Charles IX, also Carl (; 4 October 1550 – 30 October 1611), reigned as King of Sweden from 1604 until his death. He was the youngest son of King Gustav I () and of his second wife, Margaret Leijonhufvud, the brother of King Eric XIV and of ...

(on 28 February 1609). The Commonwealth king Sigismund III, whose primary goal was to regain the Swedish throne, got permission from the Polish Sejm (Parliament) to declare war

A declaration of war is a formal act by which one state announces existing or impending war activity against another. The declaration is a performative speech act (or the public signing of a document) by an authorized party of a national gover ...

on Russia

Russia, or the Russian Federation, is a country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia. It is the list of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the world, and extends across Time in Russia, eleven time zones, sharing Borders ...

. He viewed it as an excellent opportunity to expand the Commonwealth's territory and sphere of influence

In the field of international relations, a sphere of influence (SOI) is a spatial region or concept division over which a state or organization has a level of cultural, economic, military, or political exclusivity.

While there may be a formal a ...

, with hopes that the eventual outcome of the war would Catholicize Orthodox

Orthodox, Orthodoxy, or Orthodoxism may refer to:

Religion

* Orthodoxy, adherence to accepted norms, more specifically adherence to creeds, especially within Christianity and Judaism, but also less commonly in non-Abrahamic religions like Neo-pag ...

Russia (in this he was strongly supported by the Pope) and enable him to defeat Sweden. This plan also allowed him to give a purpose to the numerous restless former supporters of Zebrzydowski, luring them with promises of wealth and fame awaiting members of the campaign beyond the Commonwealth's eastern border. A book published that year by the well-travelled Polish Silesian nobleman, courtier

A courtier () is a person who attends the royal court of a monarch or other royalty. The earliest historical examples of courtiers were part of the retinues of rulers. Historically the court was the centre of government as well as the officia ...

and political activist Paweł Palczowski of Palczowic, ''Kolęda moskiewska'' (''The Muscovite Carol''), compared Russia to the Indian empires of the New World

The term "New World" is used to describe the majority of lands of Earth's Western Hemisphere, particularly the Americas, and sometimes Oceania."America." ''The Oxford Companion to the English Language'' (). McArthur, Tom, ed., 1992. New York: ...

, full of golden cities and easy to conquer. The treatise

A treatise is a Formality, formal and systematic written discourse on some subject concerned with investigating or exposing the main principles of the subject and its conclusions."mwod:treatise, Treatise." Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary. Acc ...

was written to promote Polish colonialism and persuade delegates of the Sejm in January 1609 to support Sigismund III's expedition to Muscovy Muscovy or Moscovia () is an alternative name for the Principality of Moscow (1263–1547) and the Tsardom of Russia (1547–1721).

It may also refer to:

*Muscovy Company, an English trading company chartered in 1555

*Muscovy duck (''Cairina mosch ...

. Palczowski himself participated in and perished during Sigismund's Muscovy expedition.Sarmatian Review, Rice University, Texas, January 2011, Vol. XXXI, No. 1., p. 1561; ''The Muscovite Carol (Kolęda moskiewska)'' by Paweł Palczowski of Palczowic. Edited by Grzegorz Franczak/ref> Some Russian boyars assured Sigismund of their support by offering the throne to his son, Prince Wladislaus IV of Poland, Władysław. Previously, Sigismund had been unwilling to commit the majority of Polish forces or his time to the internal conflict in Russia, but in 1609 those factors made him re-evaluate and drastically change his policy. Although many Polish nobles and soldiers were fighting for the second False Dmitry at the time, Sigismund III and the troops under his command did not support Dimitriy for the throne – Sigismund wanted Russia himself. The entry of Sigismund into Russia caused the majority of the Polish supporters of False Dmitry II to desert him and contributed to his defeat. A series of subsequent disasters induced False Dmitry II to flee his camp disguised as a peasant and to go to Kostroma together with Marina. Dmitry made another unsuccessful attack on Moscow, and, supported by the

Don Cossacks

Don Cossacks (, ) or Donians (, ), are Cossacks who settled along the middle and lower Don River (Russia), Don. Historically, they lived within the former Don Cossack Host (, ), which was either an independent or an autonomous democratic rep ...

, recovered a hold over all of south-eastern Russia. He was killed, however, while half drunk, on 11 December 1610 by a Qasim Tatar princeling Pyotr Urusov, whom Dimitriy had flogged on a previous occasion.

A Commonwealth army under the command of Hetman

''Hetman'' is a political title from Central and Eastern Europe, historically assigned to military commanders (comparable to a field marshal or imperial marshal in the Holy Roman Empire). First used by the Czechs in Bohemia in the 15th century, ...

Stanisław Żółkiewski

Stanisław Żółkiewski (; 1547 – 7 October 1620) was a Polish people, Polish szlachta, nobleman of the Lubicz coat of arms, a magnate, military commander, and Chancellor (Poland), Chancellor of the Polish Crown in the Polish–Lithuanian C ...

, who was generally opposed to this conflict but could not disobey the king's orders, crossed the border and on 29 September 1609 laid siege to Smolensk, an important city Russia had captured from Lithuania in 1514. Smolensk

Smolensk is a city and the administrative center of Smolensk Oblast, Russia, located on the Dnieper River, west-southwest of Moscow.

First mentioned in 863, it is one of the oldest cities in Russia. It has been a regional capital for most of ...

was manned by fewer than 1,000 Russian men commanded by the voivod Mikhail Shein

Mikhail Borisovich Shein (, ) (late 1570s–1634) was a leading Russian general during the reign of Tsar Mikhail Romanov. Despite his tactical skills and successful military career, he ended up losing his army in a failed attempt to besiege Smol ...

, while Żółkiewski commanded 12,000 troops. However, Smolensk had one major advantage: the previous Tsar, Boris Godunov, had sponsored the fortification of the city with a massive fortress completed in 1602. The Poles found it impenetrable; they settled into a long siege, firing artillery into the city, attempting to tunnel under the moat

A moat is a deep, broad ditch dug around a castle, fortification, building, or town, historically to provide it with a preliminary line of defence. Moats can be dry or filled with water. In some places, moats evolved into more extensive water d ...

, and building earthen rampart

Rampart may refer to:

* Rampart (fortification), a defensive wall or bank around a castle, fort or settlement

Rampart may also refer to:

* LAPD Rampart Division, a division of the Los Angeles Police Department

** Rampart scandal, a blanket ter ...

s, remnants of which can still be seen today. The siege lasted 20 months before the Poles with the help of a Russian defector named Andrei Dedishin eventually succeeded in taking the fortress.

Not all of the Commonwealth attacks were successful. An early attack, led by Hetman Jan Karol Chodkiewicz

Jan Karol Chodkiewicz (; 1561 – 24 September 1621) was a Polish–Lithuanian identity, Polish–Lithuanian military commander of the Grand Ducal Lithuanian Army, who was from 1601 Field Hetman of Lithuania, and from 1605 Grand Hetman of Lit ...

with 2,000 men, ended in defeat when the unpaid Commonwealth army mutinied and compelled their leader to retreat through the heart of Russia and back to Smolensk. Not until Crown Prince Władysław, arrived with tardy reinforcements did the war assume a different character. In the meantime, Lisowczycy took and plundered Pskov

Pskov ( rus, Псков, a=Ru-Псков.oga, p=psˈkof; see also Names of Pskov in different languages, names in other languages) is a types of inhabited localities in Russia, city in northwestern Russia and the administrative center of Pskov O ...

in 1610 and clashed with the Swedes operating in Russia during the Ingrian War

The Ingrian War () was a conflict fought between the Swedish Empire and the Tsardom of Russia which lasted between 1610 and 1617. It can be seen as part of Russia's Time of Troubles, and is mainly remembered for the attempt to put a Swedish duk ...

.

Several different visions of the campaign and political goals clashed in the Polish camp. Some of the former members of the Zebrzydowski Rebellion, opponents of Sigismund, actually advanced proposals to have Sigismund dethroned and Dmitriy, or even Shuyski, elected king. Żółkiewski, who from the beginning opposed the invasion of Russia, came into conflict with Sigismund over the scope, methods, and goal of the campaign. Żółkiewski represented the traditional views of Polish nobility, the szlachta

The ''szlachta'' (; ; ) were the nobility, noble estate of the realm in the Kingdom of Poland, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, and the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. Depending on the definition, they were either a warrior "caste" or a social ...

, which did not support waging aggressive and dangerous wars against a strong enemy like Russia. Thus Żółkiewski favored the plans for peaceful and voluntary union, much like that with Lithuania. Żółkiewski offered Russian boyars rights and religious freedom, envisioning an association resulting in the creation of the Polish–Lithuanian–Muscovite Commonwealth. To that end, he felt that Moscow's cooperation should be gained via diplomacy, not force. Sigismund III, however, did not want to engage in political deals and compromises, especially when these had to include concessions to the Orthodox Church. Sigismund was a vocal, almost fanatical, supporter of the Catholic Church

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

and Counter-Reformation

The Counter-Reformation (), also sometimes called the Catholic Revival, was the period of Catholic resurgence that was initiated in response to, and as an alternative to or from similar insights as, the Protestant Reformations at the time. It w ...

, and believed that he could win everything and take Moscow by force, and then establish his own rule along with the rule of Roman Catholicism.

Poles in Moscow (1610)

On 31 January 1610 Sigismund received a delegation of boyars opposed to Shuyski, who asked Władysław to become the tsar. On 24 February Sigismund sent them a letter in which he agreed to do so, but only when Moscow was at peace.battle of Klushino

The Battle of Klushino, or the Battle of Kłuszyn, was fought on 4 July 1610, between forces of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth and the Tsardom of Russia during the Polish–Russian War, part of Russia's Time of Troubles. The battle occu ...

(Kłuszyn), where 7,000 Polish elite cavalry, the winged hussars, led by the hetman himself, defeated the numerically superior Russian army of about 35,000–40,000 soldiers. This giant and surprising defeat of the Russians shocked everyone and opened a new phase in the conflict.

After the news of Klushino spread, support for Tsar Shuyski almost completely evaporated. Żółkiewski soon convinced the Russian units at Tsaryovo, which were much stronger than the ones at Kłuszyn, to capitulate and to swear an oath of loyalty to Władysław. Then he incorporated them into his army and moved towards Moscow. In August 1610 many Russian

After the news of Klushino spread, support for Tsar Shuyski almost completely evaporated. Żółkiewski soon convinced the Russian units at Tsaryovo, which were much stronger than the ones at Kłuszyn, to capitulate and to swear an oath of loyalty to Władysław. Then he incorporated them into his army and moved towards Moscow. In August 1610 many Russian boyar

A boyar or bolyar was a member of the highest rank of the feudal nobility in many Eastern European states, including Bulgaria, Kievan Rus' (and later Russia), Moldavia and Wallachia (and later Romania), Lithuania and among Baltic Germans. C ...

s accepted that Sigismund III was victorious and that Władysław would become the next tsar if he converted to Eastern Orthodoxy

Eastern Orthodoxy, otherwise known as Eastern Orthodox Christianity or Byzantine Christianity, is one of the three main Branches of Christianity, branches of Chalcedonian Christianity, alongside Catholic Church, Catholicism and Protestantism ...

. The Russian Duma

A duma () is a Russian assembly with advisory or legislative functions.

The term ''boyar duma'' is used to refer to advisory councils in Russia from the 10th to 17th centuries. Starting in the 18th century, city dumas were formed across Russia ...

voted for Tsar Shuyski to be removed from the throne. Shuyski's family, including the tsar, were captured, and Shuyski was reportedly taken to a monastery, forcibly shaved as a monk, and compelled to remain at the monastery under guard. He was later sent to Warsaw, as a kind of war trophy, and eventually died in Gostynin

Gostynin is a town in central Poland with 19,414 inhabitants (2004). It is the capital of Gostynin County in the Masovian Voivodship.

History

Gostynin has a long and rich history, which dates back to the early Middle Ages. In the 6th century, a ...

.

Shortly after Shuyski was removed, both Żółkiewski and the second False Dmitri arrived at Moscow with their separate armies. It was a tense moment, filled with the confusion of the conflict. Various pro- and anti-Polish, Swedish, and domestic boyar factions vied for temporary control of the situation. The Russian army and the people themselves were unsure if this was an invasion and that they should close and defend the city, or if it was a liberating force that should be allowed in and welcomed as allies. After a few skirmishes, the pro-Polish faction gained dominance, and the Poles were allowed into Moscow on 8 October. The boyars opened Moscow's gates to the Polish troops and asked Żółkiewski to protect them from anarchy. The Moscow Kremlin

The Moscow Kremlin (also the Kremlin) is a fortified complex in Moscow, Russia. Located in the centre of the country's capital city, the Moscow Kremlin comprises five palaces, four cathedrals, and the enclosing Kremlin Wall along with the K ...

was then garrisoned by Polish troops commanded by Aleksander Gosiewski. On 27 July a treaty was signed between the boyars and Żółkiewski promising the Russian boyars the same vast privileges the Polish Szlachta had, in exchange for them recognizing Władysław as the new tsar. However, Żółkiewski did not know that Sigismund, who remained at Smolensk, already had other plans.

In the meantime, Żółkiewski and the second False Dmitriy, formerly reluctant allies, began to part ways. The second False Dmitry had lost much of his influence over the Polish court, and Żółkiewski would eventually try to drive Dmitry from the capital. Żółkiewski soon began manoeuvring for a tsar of Polish origin, particularly the 15-year-old Prince Władysław. The boyars had offered the throne to Władysław at least twice, in the hopes of having the liberal Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth end the

In the meantime, Żółkiewski and the second False Dmitriy, formerly reluctant allies, began to part ways. The second False Dmitry had lost much of his influence over the Polish court, and Żółkiewski would eventually try to drive Dmitry from the capital. Żółkiewski soon began manoeuvring for a tsar of Polish origin, particularly the 15-year-old Prince Władysław. The boyars had offered the throne to Władysław at least twice, in the hopes of having the liberal Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth end the despotic

In political science, despotism () is a form of government in which a single entity rules with absolute power. Normally, that entity is an individual, the despot (as in an autocracy), but societies which limit respect and power to specific gr ...

rule of their current tsars. Through Żółkiewski's work, the pro-Polish factions among the boyars (composed of knyazes Fyodor Mstislavsky, Vasily Galitzine

Prince Vasily Vasilyevich Golitsyn (, tr. ; 1643–1714) was a Russian aristocrat and statesman of the 17th century. He belonged to the Golitsyn as well as Romodanovsky Muscovite noble families. His main political opponent was his cousin Princ ...

, Fyodor Sheremetev, Daniil Mezetsky and diaks Vasily Telepnyov, and Tomiło Łagowski) gained dominance and once again a majority of the boyars said that they would support Władysław for the throne, if he converted to Orthodoxy and if the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth returned the fortresses that they had captured in the war.

However, Sigismund, supported by some of the more devout and zealous nobility, was completely opposed to the conversion of the prince. From that point the planned Polish–Lithuanian–Muscovite union began to fall apart. Offended and angered by Sigismund, the boyars dragged their feet on supporting Władysław. They were divided between electing Vasily Galitzine

Prince Vasily Vasilyevich Golitsyn (, tr. ; 1643–1714) was a Russian aristocrat and statesman of the 17th century. He belonged to the Golitsyn as well as Romodanovsky Muscovite noble families. His main political opponent was his cousin Princ ...

, Michael Romanov

Michael I (; ) was Tsar of all Russia from 1613 after being elected by the Zemsky Sobor of 1613 until his death in 1645. He was elected by the Zemsky Sobor and was the first tsar of the House of Romanov, which succeeded the House of Rurik.

...

(also 15 years old), or the second False Dmitriy. Żółkiewski acted quickly, making promises without the consent of the still-absent king, and the boyars elected Władysław as the new tsar. Żółkiewski had the most prominent of the opponents, Fyodor Romanov, Michael's father and the patriarch of Moscow

The Patriarch of Moscow and all Rus (), also known as the Patriarch of Moscow and all Russia, is the title of the primate of the Russian Orthodox Church (ROC). It is often preceded by the honorific "His Holiness". As the ordinary of the diocese ...

, exiled from Russia to secure Polish support. After the election of Władysław, the second False Dmitry fled from Tushino

Tushino ( rus, Тушино, p=ˈtuʂɨnə) is a former village and town to the north of Moscow, which has been part of the city's area since 1960. Between 1939 and 1960, Tushino was classed as a separate town. The Skhodnya River flows across the ...

, a city near Moscow, to his base at Kaluga

Kaluga (, ) is a types of inhabited localities in Russia, city and the administrative center of Kaluga Oblast, Russia. It stands on the Oka River southwest of Moscow. Its population was 337,058 at the 2021 census.

Kaluga's most famous residen ...

. However, his position was precarious even there, and he was killed on 20 December by one of his own men. Marina Mniszech, though, was pregnant with the new "heir" to the Russian throne, Ivan Dmitriyevich, and she would still be a factor in Russian politics until her eventual death in 1614.