Plasmodium falciparum on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Plasmodium falciparum'' is a

Falciparum malaria was familiar to the

Falciparum malaria was familiar to the

''P. falciparum'' does not have a fixed structure but undergoes continuous change during its life cycle. A sporozoite is spindle-shaped and 10–15 μm long. In the liver, it grows into an ovoid schizont of 30–70 μm in diameter. Each schizont produces merozoites, each of which is roughly 1.5 μm in length and 1 μm in diameter. In the erythrocyte the merozoite forms a ring-like structure, becoming a trophozoite. A trophozoite feeds on the haemoglobin and forms a granular pigment called haemozoin. Unlike those of other ''Plasmodium'' species, the gametocytes of ''P. falciparum'' are elongated and crescent-shaped, by which they are sometimes identified. A mature gametocyte is 8–12 μm long and 3–6 μm wide. The ookinete is also elongated measuring about 18–24 μm. An oocyst is rounded and can grow up to 80 μm in diameter. Microscopic examination of a blood film reveals only early (ring-form) trophozoites and gametocytes that are in the peripheral blood. Mature trophozoites or schizonts in peripheral blood smears, as these are usually sequestered in the tissues. On occasion, faint, comma-shaped, red dots are seen on the erythrocyte surface. These dots are Maurer's cleft and are secretory organelles that produce proteins and enzymes essential for nutrient uptake and immune evasion processes.

The apical complex, which is a combination of organelles, is an important structure. It contains secretory organelles called rhoptries and micronemes, which are vital for mobility, adhesion, host cell invasion, and parasitophorous vacuole formation. As an apicomplexan, it harbours a plastid, an

''P. falciparum'' does not have a fixed structure but undergoes continuous change during its life cycle. A sporozoite is spindle-shaped and 10–15 μm long. In the liver, it grows into an ovoid schizont of 30–70 μm in diameter. Each schizont produces merozoites, each of which is roughly 1.5 μm in length and 1 μm in diameter. In the erythrocyte the merozoite forms a ring-like structure, becoming a trophozoite. A trophozoite feeds on the haemoglobin and forms a granular pigment called haemozoin. Unlike those of other ''Plasmodium'' species, the gametocytes of ''P. falciparum'' are elongated and crescent-shaped, by which they are sometimes identified. A mature gametocyte is 8–12 μm long and 3–6 μm wide. The ookinete is also elongated measuring about 18–24 μm. An oocyst is rounded and can grow up to 80 μm in diameter. Microscopic examination of a blood film reveals only early (ring-form) trophozoites and gametocytes that are in the peripheral blood. Mature trophozoites or schizonts in peripheral blood smears, as these are usually sequestered in the tissues. On occasion, faint, comma-shaped, red dots are seen on the erythrocyte surface. These dots are Maurer's cleft and are secretory organelles that produce proteins and enzymes essential for nutrient uptake and immune evasion processes.

The apical complex, which is a combination of organelles, is an important structure. It contains secretory organelles called rhoptries and micronemes, which are vital for mobility, adhesion, host cell invasion, and parasitophorous vacuole formation. As an apicomplexan, it harbours a plastid, an

Humans are the intermediate hosts in which asexual reproduction occurs, and female anopheline mosquitos are the definitive hosts harbouring the sexual reproduction stage.

Humans are the intermediate hosts in which asexual reproduction occurs, and female anopheline mosquitos are the definitive hosts harbouring the sexual reproduction stage.

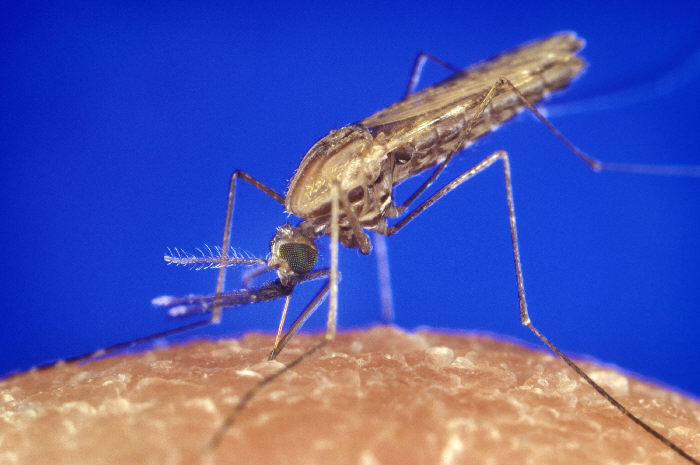

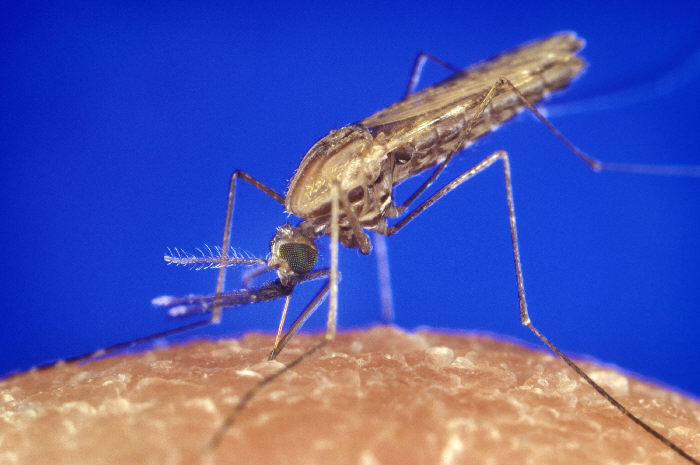

Infection in humans begins with the bite of an infected female ''Anopheles'' mosquito. Out of about 460 species of ''

Infection in humans begins with the bite of an infected female ''Anopheles'' mosquito. Out of about 460 species of ''

Authors: WHO. Number of pages: 194. Publication date: 2010. Languages: English. artemisinin-based combination therapies (ACTs) are the recommended first-line antimalarial treatments for uncomplicated malaria caused by ''P. falciparum''. WHO recommends combinations such as artemether/lumefantrine, artesunate/amodiaquine, artesunate/mefloquine, artesunate/sulfadoxine/pyrimethamine, and dihydroartemisinin/piperaquine. The choice of ACT is based on the level of resistance to the constituents in the combination. Artemisinin and its derivatives are not appropriate for monotherapy. As a second-line antimalarial treatment, when initial treatment does not work, an alternative ACT known to be effective in the region is recommended, such as artesunate plus tetracycline or

Colombian scientists develop computational tool to detect ''Plasmodium falciparum'' (in Spanish)

* * * * *

Malaria parasite species info at CDC

Web Atlas of Medical Parasitology

Species profile at Encyclopedia of Life

Taxonomy at UniProt

Profile at Scientists Against Malaria

PlasmoDB: The Plasmodium Genome Resource

UCSC Plasmodium Falciparum Browser

{{Authority control Articles containing video clips IARC Group 2A carcinogens Infectious causes of cancer Malaria falciparum Pathogenic microbes Parasites of humans Protozoal diseases Species described in 1881

unicellular

A unicellular organism, also known as a single-celled organism, is an organism that consists of a single cell, unlike a multicellular organism that consists of multiple cells. Organisms fall into two general categories: prokaryotic organisms and ...

protozoa

Protozoa (: protozoan or protozoon; alternative plural: protozoans) are a polyphyletic group of single-celled eukaryotes, either free-living or parasitic, that feed on organic matter such as other microorganisms or organic debris. Historically ...

n parasite

Parasitism is a Symbiosis, close relationship between species, where one organism, the parasite, lives (at least some of the time) on or inside another organism, the Host (biology), host, causing it some harm, and is Adaptation, adapted str ...

of human

Humans (''Homo sapiens'') or modern humans are the most common and widespread species of primate, and the last surviving species of the genus ''Homo''. They are Hominidae, great apes characterized by their Prehistory of nakedness and clothing ...

s and is the deadliest species of ''Plasmodium

''Plasmodium'' is a genus of unicellular eukaryotes that are obligate parasites of vertebrates and insects. The life cycles of ''Plasmodium'' species involve development in a Hematophagy, blood-feeding insect host (biology), host which then inj ...

'' that causes malaria

Malaria is a Mosquito-borne disease, mosquito-borne infectious disease that affects vertebrates and ''Anopheles'' mosquitoes. Human malaria causes Signs and symptoms, symptoms that typically include fever, Fatigue (medical), fatigue, vomitin ...

in humans. The parasite is transmitted through the bite of a female ''Anopheles

''Anopheles'' () is a genus of mosquito first described by the German entomologist Johann Wilhelm Meigen, J. W. Meigen in 1818, and are known as nail mosquitoes and marsh mosquitoes. Many such mosquitoes are Disease vector, vectors of the paras ...

'' mosquito

Mosquitoes, the Culicidae, are a Family (biology), family of small Diptera, flies consisting of 3,600 species. The word ''mosquito'' (formed by ''Musca (fly), mosca'' and diminutive ''-ito'') is Spanish and Portuguese for ''little fly''. Mos ...

and causes the disease's most dangerous form, falciparum malaria. ''P. falciparum'' is therefore regarded as the deadliest parasite in humans. It is also associated with the development of blood cancer (Burkitt's lymphoma

Burkitt's lymphoma is a cancer of the lymphatic system, particularly B lymphocytes found in the germinal center. It is named after Denis Parsons Burkitt, the Irish surgeon who first described the disease in 1958 while working in equatorial Africa ...

) and is classified as a Group 2A (probable) carcinogen.

The species originated from the malarial parasite '' Laverania'' found in gorilla

Gorillas are primarily herbivorous, terrestrial great apes that inhabit the tropical forests of equatorial Africa. The genus ''Gorilla'' is divided into two species: the eastern gorilla and the western gorilla, and either four or five su ...

s, around 10,000 years ago. Alphonse Laveran was the first to identify the parasite in 1880, and named it ''Oscillaria malariae''. Ronald Ross

Sir Ronald Ross (13 May 1857 – 16 September 1932) was a British medical doctor who received the Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine in 1902 for his work on the transmission of malaria, becoming the first British Nobel laureate, and the f ...

discovered its transmission by mosquito in 1897. Giovanni Battista Grassi

Giovanni Battista Grassi (27 March 1854 – 4 May 1925) was an Italian people, Italian physician and zoologist, best known for his pioneering works on parasitology, especially on malariology. He was Professor of Comparative Zoology at the Unive ...

elucidated the complete transmission from a female anopheline mosquito to humans in 1898. In 1897, William H. Welch created the name ''Plasmodium falciparum'', which ICZN formally adopted in 1954. ''P. falciparum'' assumes several different forms during its life cycle. The human-infective stage are sporozoites from the salivary gland of a mosquito. The sporozoites grow and multiply in the liver

The liver is a major metabolic organ (anatomy), organ exclusively found in vertebrates, which performs many essential biological Function (biology), functions such as detoxification of the organism, and the Protein biosynthesis, synthesis of var ...

to become merozoites. These merozoites invade the erythrocytes

Red blood cells (RBCs), referred to as erythrocytes (, with -''cyte'' translated as 'cell' in modern usage) in academia and medical publishing, also known as red cells, erythroid cells, and rarely haematids, are the most common type of blood cel ...

(red blood cells) to form trophozoites, schizonts and gametocytes, during which the symptoms of malaria are produced. In the mosquito, the gametocytes undergo sexual reproduction to a zygote

A zygote (; , ) is a eukaryote, eukaryotic cell (biology), cell formed by a fertilization event between two gametes.

The zygote's genome is a combination of the DNA in each gamete, and contains all of the genetic information of a new individ ...

, which turns into ookinete. Ookinete forms oocyte

An oocyte (, oöcyte, or ovocyte) is a female gametocyte or germ cell involved in reproduction. In other words, it is an immature ovum, or egg cell. An oocyte is produced in a female fetus in the ovary during female gametogenesis. The female ger ...

s from which sporozoites are formed.

In 2022, some 249 million cases of malaria worldwide resulted in an estimated 608,000 deaths, with 80 percent being 5 years old or less. Nearly all malarial deaths are caused by ''P. falciparum'', and 95% of such cases occur in Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent after Asia. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 20% of Earth's land area and 6% of its total surfac ...

. In Sub-Saharan Africa, almost 100% of cases were due to ''P. falciparum'', whereas in most other regions where malaria is endemic, other, less virulent plasmodial species predominate.

History

Falciparum malaria was familiar to the

Falciparum malaria was familiar to the ancient Greeks

Ancient Greece () was a northeastern Mediterranean civilization, existing from the Greek Dark Ages of the 12th–9th centuries BC to the end of classical antiquity (), that comprised a loose collection of culturally and linguistically re ...

, who gave the general name (''pyretós'') "fever". Hippocrates

Hippocrates of Kos (; ; ), also known as Hippocrates II, was a Greek physician and philosopher of the Classical Greece, classical period who is considered one of the most outstanding figures in the history of medicine. He is traditionally referr ...

(c. 460–370 BCE) gave several descriptions on tertian fever and quartan fever. It was prevalent throughout the ancient Egyptian and Roman civilizations. It was the Romans who named the disease "malaria"—''mala'' for bad, and ''aria'' for air, as they believed that the disease was spread by contaminated air, or miasma.

Discovery

A German physician, Johann Friedrich Meckel, must have been the first to see ''P. falciparum'' but without knowing what it was. In 1847, he reported the presence of black pigment granules from the blood and spleen of a patient who died of malaria. The French Army physician Charles Louis Alphonse Laveran, while working at Bône Hospital (nowAnnaba

Annaba (), formerly known as Bon, Bona and Bône, is a seaport city in the northeastern corner of Algeria, close to the border with Tunisia. Annaba is near the small Seybouse River and is in the Annaba Province. With a population of about 263,65 ...

in Algeria), correctly identified the parasite as a causative pathogen of malaria in 1880. He presented his discovery before the French Academy of Medicine in Paris and published it in ''The Lancet

''The Lancet'' is a weekly peer-reviewed general medical journal, founded in England in 1823. It is one of the world's highest-impact academic journals and also one of the oldest medical journals still in publication.

The journal publishes ...

'' in 1881. He gave it the scientific name ''Oscillaria malariae''. However, his discovery was received with skepticism, mainly because by that time, leading physicians such as Theodor Albrecht Edwin Klebs and Corrado Tommasi-Crudeli claimed that they had discovered a bacterium (which they called ''Bacillus malariae'') as the pathogen of malaria. Laveran's discovery was only widely accepted after five years when Camillo Golgi

Camillo Golgi (; 7 July 184321 January 1926) was an Italian biologist and pathologist known for his works on the central nervous system. He studied medicine at the University of Pavia (where he later spent most of his professional career) bet ...

confirmed the parasite using better microscopes and staining techniques. Laveran was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine

The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine () is awarded yearly by the Nobel Assembly at the Karolinska Institute for outstanding discoveries in physiology or medicine. The Nobel Prize is not a single prize, but five separate prizes that, acco ...

in 1907 for his work. In 1900, the Italian zoologist Giovanni Battista Grassi

Giovanni Battista Grassi (27 March 1854 – 4 May 1925) was an Italian people, Italian physician and zoologist, best known for his pioneering works on parasitology, especially on malariology. He was Professor of Comparative Zoology at the Unive ...

categorized ''Plasmodium

''Plasmodium'' is a genus of unicellular eukaryotes that are obligate parasites of vertebrates and insects. The life cycles of ''Plasmodium'' species involve development in a Hematophagy, blood-feeding insect host (biology), host which then inj ...

'' species based on the timing of fever in the patient; malignant tertian malaria was caused by ''Laverania malariae'' (now ''P. falciparum''), benign tertian malaria by ''Haemamoeba vivax'' (now '' P. vivax''), and quartan malaria by ''Haemamoeba malariae'' (now '' P. malariae'').

The British physician Patrick Manson formulated the mosquito-malaria theory in 1894; until that time, malarial parasites were believed to be spread in air as miasma, a Greek word for pollution. His colleague Ronald Ross

Sir Ronald Ross (13 May 1857 – 16 September 1932) was a British medical doctor who received the Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine in 1902 for his work on the transmission of malaria, becoming the first British Nobel laureate, and the f ...

of the Indian Medical Service validated the theory while working in India. Ross discovered in 1897 that malarial parasites lived in certain mosquitoes. The next year, he demonstrated that a malarial parasite of birds could be transmitted by mosquitoes from one bird to another. Around the same time, Grassi demonstrated that ''P. falciparum'' was transmitted in humans only by female anopheline mosquito (in his case '' Anopheles claviger''). Ross, Manson and Grassi were nominated for the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1902. Under controversial circumstances, only Ross was selected for the award.

There was a long debate on the taxonomy. It was only in 1954 the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature

The International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature (ICZN) is an organization dedicated to "achieving stability and sense in the scientific naming of animals". Founded in 1895, it currently comprises 26 commissioners from 20 countries.

Orga ...

officially approved the binominal ''Plasmodium falciparum''. The valid genus ''Plasmodium'' was created by two Italian physicians Ettore Marchiafava and Angelo Celli in 1885. The Greek word ''plasma'' means "mould" or "form"; ''oeidēs'' means "to see" or "to know." The species name was introduced by an American physician William Henry Welch in 1897. It is derived from the Latin ''falx'', meaning "sickle" and ''parum'' meaning "like or equal to another".

Origin and evolution

''P. falciparum'' is now generally accepted to have evolved from '' Laverania'' (a subgenus of ''Plasmodium'' found in apes) species present in gorillas in Western Africa. Genetic diversity indicates that the human protozoan emerged around 10,000 years ago. The closest relative of ''P. falciparum'' is ''P. praefalciparum'', a parasite ofgorilla

Gorillas are primarily herbivorous, terrestrial great apes that inhabit the tropical forests of equatorial Africa. The genus ''Gorilla'' is divided into two species: the eastern gorilla and the western gorilla, and either four or five su ...

s, as supported by mitochondrial

A mitochondrion () is an organelle found in the cells of most eukaryotes, such as animals, plants and fungi. Mitochondria have a double membrane structure and use aerobic respiration to generate adenosine triphosphate (ATP), which is used ...

, apicoplast

An apicoplast is a derived non-photosynthetic plastid found in most Apicomplexa, including ''Toxoplasma gondii'', and ''Plasmodium falciparum'' and other ''Plasmodium'' spp. (parasites causing malaria), but not in others such as ''Cryptosporidium' ...

ic and nuclear DNA

Nuclear DNA (nDNA), or nuclear deoxyribonucleic acid, is the DNA contained within each cell nucleus of a eukaryotic organism. It encodes for the majority of the genome in eukaryotes, with mitochondrial DNA and plastid DNA coding for the rest. ...

sequences. These two species are closely related to the chimpanzee

The chimpanzee (; ''Pan troglodytes''), also simply known as the chimp, is a species of Hominidae, great ape native to the forests and savannahs of tropical Africa. It has four confirmed subspecies and a fifth proposed one. When its close rel ...

parasite ''P. reichenowi'', which was previously thought to be the closest relative of ''P. falciparum''. ''P. falciparum'' was also once thought to originate from a parasite of birds.

Levels of genetic polymorphism are extremely low within the ''P. falciparum'' genome compared to that of closely related, ape infecting species of ''Plasmodium'' (including ''P. praefalciparum''). This suggests that the origin of ''P. falciparum'' in humans is recent, as a single ''P. praefalciparum'' strain became capable of infecting humans. The genetic information of ''P. falciparum'' has signaled a recent expansion that coincides with the agricultural revolution. The development of extensive agriculture likely increased mosquito population densities by giving rise to more breeding sites, which may have triggered the evolution and expansion of ''P. falciparum''.

Structure

''P. falciparum'' does not have a fixed structure but undergoes continuous change during its life cycle. A sporozoite is spindle-shaped and 10–15 μm long. In the liver, it grows into an ovoid schizont of 30–70 μm in diameter. Each schizont produces merozoites, each of which is roughly 1.5 μm in length and 1 μm in diameter. In the erythrocyte the merozoite forms a ring-like structure, becoming a trophozoite. A trophozoite feeds on the haemoglobin and forms a granular pigment called haemozoin. Unlike those of other ''Plasmodium'' species, the gametocytes of ''P. falciparum'' are elongated and crescent-shaped, by which they are sometimes identified. A mature gametocyte is 8–12 μm long and 3–6 μm wide. The ookinete is also elongated measuring about 18–24 μm. An oocyst is rounded and can grow up to 80 μm in diameter. Microscopic examination of a blood film reveals only early (ring-form) trophozoites and gametocytes that are in the peripheral blood. Mature trophozoites or schizonts in peripheral blood smears, as these are usually sequestered in the tissues. On occasion, faint, comma-shaped, red dots are seen on the erythrocyte surface. These dots are Maurer's cleft and are secretory organelles that produce proteins and enzymes essential for nutrient uptake and immune evasion processes.

The apical complex, which is a combination of organelles, is an important structure. It contains secretory organelles called rhoptries and micronemes, which are vital for mobility, adhesion, host cell invasion, and parasitophorous vacuole formation. As an apicomplexan, it harbours a plastid, an

''P. falciparum'' does not have a fixed structure but undergoes continuous change during its life cycle. A sporozoite is spindle-shaped and 10–15 μm long. In the liver, it grows into an ovoid schizont of 30–70 μm in diameter. Each schizont produces merozoites, each of which is roughly 1.5 μm in length and 1 μm in diameter. In the erythrocyte the merozoite forms a ring-like structure, becoming a trophozoite. A trophozoite feeds on the haemoglobin and forms a granular pigment called haemozoin. Unlike those of other ''Plasmodium'' species, the gametocytes of ''P. falciparum'' are elongated and crescent-shaped, by which they are sometimes identified. A mature gametocyte is 8–12 μm long and 3–6 μm wide. The ookinete is also elongated measuring about 18–24 μm. An oocyst is rounded and can grow up to 80 μm in diameter. Microscopic examination of a blood film reveals only early (ring-form) trophozoites and gametocytes that are in the peripheral blood. Mature trophozoites or schizonts in peripheral blood smears, as these are usually sequestered in the tissues. On occasion, faint, comma-shaped, red dots are seen on the erythrocyte surface. These dots are Maurer's cleft and are secretory organelles that produce proteins and enzymes essential for nutrient uptake and immune evasion processes.

The apical complex, which is a combination of organelles, is an important structure. It contains secretory organelles called rhoptries and micronemes, which are vital for mobility, adhesion, host cell invasion, and parasitophorous vacuole formation. As an apicomplexan, it harbours a plastid, an apicoplast

An apicoplast is a derived non-photosynthetic plastid found in most Apicomplexa, including ''Toxoplasma gondii'', and ''Plasmodium falciparum'' and other ''Plasmodium'' spp. (parasites causing malaria), but not in others such as ''Cryptosporidium' ...

, similar to plant chloroplast

A chloroplast () is a type of membrane-bound organelle, organelle known as a plastid that conducts photosynthesis mostly in plant cell, plant and algae, algal cells. Chloroplasts have a high concentration of chlorophyll pigments which captur ...

s, which they probably acquired by engulfing (or being invaded by) a eukaryotic

The eukaryotes ( ) constitute the Domain (biology), domain of Eukaryota or Eukarya, organisms whose Cell (biology), cells have a membrane-bound cell nucleus, nucleus. All animals, plants, Fungus, fungi, seaweeds, and many unicellular organisms ...

alga

Algae ( , ; : alga ) is an informal term for any organisms of a large and diverse group of photosynthetic organisms that are not plants, and includes species from multiple distinct clades. Such organisms range from unicellular microalgae, suc ...

and retaining the algal plastid as a distinctive organelle

In cell biology, an organelle is a specialized subunit, usually within a cell (biology), cell, that has a specific function. The name ''organelle'' comes from the idea that these structures are parts of cells, as Organ (anatomy), organs are to th ...

encased within four membranes. The apicoplast is involved in the synthesis of lipid

Lipids are a broad group of organic compounds which include fats, waxes, sterols, fat-soluble vitamins (such as vitamins A, D, E and K), monoglycerides, diglycerides, phospholipids, and others. The functions of lipids include storing ...

s and several other compounds and provides an attractive drug target. During the asexual blood stage of infection, an essential function of the apicoplast is to produce the isoprenoid precursors isopentenyl pyrophosphate (IPP) and dimethylallyl pyrophosphate (DMAPP) via the MEP (non-mevalonate) pathway.

Genome

In 1995 the Malaria Genome Project was set up to sequence the genome of ''P. falciparum''. The genome of itsmitochondrion

A mitochondrion () is an organelle found in the cell (biology), cells of most eukaryotes, such as animals, plants and fungi. Mitochondria have a double lipid bilayer, membrane structure and use aerobic respiration to generate adenosine tri ...

was reported in 1995, that of the nonphotosynthetic plastid

A plastid is a membrane-bound organelle found in the Cell (biology), cells of plants, algae, and some other eukaryotic organisms. Plastids are considered to be intracellular endosymbiotic cyanobacteria.

Examples of plastids include chloroplasts ...

known as the apicoplast in 1996, and the sequence of the first nuclear chromosome

A chromosome is a package of DNA containing part or all of the genetic material of an organism. In most chromosomes, the very long thin DNA fibers are coated with nucleosome-forming packaging proteins; in eukaryotic cells, the most import ...

(chromosome 2) in 1998. The sequence of chromosome 3 was reported in 1999 and the entire genome was reported on 3 October 2002. The roughly 24-megabase genome is extremely AT-rich (about 80%) and is organised into 14 chromosomes. Just over 5,300 genes were described. Many genes involved in antigenic variation are located in the subtelomeric regions of the chromosomes. These are divided into the ''var'', ''rif'', and ''stevor'' families. Within the genome, there exist 59 ''var'', 149 ''rif'', and 28 ''stevor'' genes, along with multiple pseudogenes and truncations. It is estimated that 551, or roughly 10%, of the predicted nuclear-encoded proteins

Proteins are large biomolecules and macromolecules that comprise one or more long chains of amino acid residues. Proteins perform a vast array of functions within organisms, including catalysing metabolic reactions, DNA replication, re ...

are targeted to the apicoplast

An apicoplast is a derived non-photosynthetic plastid found in most Apicomplexa, including ''Toxoplasma gondii'', and ''Plasmodium falciparum'' and other ''Plasmodium'' spp. (parasites causing malaria), but not in others such as ''Cryptosporidium' ...

, while 4.7% of the proteome

A proteome is the entire set of proteins that is, or can be, expressed by a genome, cell, tissue, or organism at a certain time. It is the set of expressed proteins in a given type of cell or organism, at a given time, under defined conditions. P ...

is targeted to the mitochondria.

Life cycle

Humans are the intermediate hosts in which asexual reproduction occurs, and female anopheline mosquitos are the definitive hosts harbouring the sexual reproduction stage.

Humans are the intermediate hosts in which asexual reproduction occurs, and female anopheline mosquitos are the definitive hosts harbouring the sexual reproduction stage.

In humans

Infection in humans begins with the bite of an infected female ''Anopheles'' mosquito. Out of about 460 species of ''

Infection in humans begins with the bite of an infected female ''Anopheles'' mosquito. Out of about 460 species of ''Anopheles

''Anopheles'' () is a genus of mosquito first described by the German entomologist Johann Wilhelm Meigen, J. W. Meigen in 1818, and are known as nail mosquitoes and marsh mosquitoes. Many such mosquitoes are Disease vector, vectors of the paras ...

'' mosquito

Mosquitoes, the Culicidae, are a Family (biology), family of small Diptera, flies consisting of 3,600 species. The word ''mosquito'' (formed by ''Musca (fly), mosca'' and diminutive ''-ito'') is Spanish and Portuguese for ''little fly''. Mos ...

, more than 70 species transmit falciparum malaria. ''Anopheles gambiae

The ''Anopheles gambiae'' complex consists of at least seven morphologically indistinguishable species of mosquitoes in the genus ''Anopheles''. The complex was recognised in the 1960s and includes the most important vectors of malaria in sub- ...

'' is one of the best known and most prevalent vectors, particularly in Africa.

The infective stage called the sporozoite

Apicomplexans, a group of intracellular parasites, have life cycle stages that allow them to survive the wide variety of environments they are exposed to during their complex life cycle. Each stage in the life cycle of an apicomplexan organis ...

is released from the salivary glands through the proboscis of the mosquito to enter through the skin during feeding. The mosquito saliva contains antihaemostatic and anti-inflammatory enzymes that disrupt blood clotting

Coagulation, also known as clotting, is the process by which blood changes from a liquid to a gel, forming a thrombus, blood clot. It results in hemostasis, the cessation of blood loss from a damaged vessel, followed by repair. The process of co ...

and inhibit the pain reaction. Typically, each infected bite contains 20–200 sporozoites. A proportion of sporozoites invade liver cells (hepatocyte

A hepatocyte is a cell of the main parenchymal tissue of the liver. Hepatocytes make up 80% of the liver's mass.

These cells are involved in:

* Protein synthesis

* Protein storage

* Transformation of carbohydrates

* Synthesis of cholesterol, bi ...

s). The sporozoites move in the bloodstream by gliding

Gliding is a recreational activity and competitive air sports, air sport in which pilots fly glider aircraft, unpowered aircraft known as Glider (sailplane), gliders or sailplanes using naturally occurring currents of rising air in the atmospher ...

, which is driven by a motor made up of the proteins actin

Actin is a family of globular multi-functional proteins that form microfilaments in the cytoskeleton, and the thin filaments in muscle fibrils. It is found in essentially all eukaryotic cells, where it may be present at a concentration of ...

and myosin

Myosins () are a Protein family, family of motor proteins (though most often protein complexes) best known for their roles in muscle contraction and in a wide range of other motility processes in eukaryotes. They are adenosine triphosphate, ATP- ...

beneath their plasma membrane

The cell membrane (also known as the plasma membrane or cytoplasmic membrane, and historically referred to as the plasmalemma) is a biological membrane that separates and protects the interior of a cell from the outside environment (the extr ...

.

Liver stage or exo-erythrocytic schizogony

Entering the hepatocytes, the parasite loses its apical complex and surface coat and transforms into a trophozoite. Within the parasitophorous vacuole of the hepatocyte, it undergoes 13–14 rounds of mitosis which produce asyncytial

A syncytium (; : syncytia; from Greek: σύν ''syn'' "together" and κύτος ''kytos'' "box, i.e. cell") or symplasm is a multinucleate cell that can result from multiple cell fusions of uninuclear cells (i.e., cells with a single nucleus), in ...

cell ( coenocyte) called a schizont. This process is called schizogony. A schizont contains tens of thousands of nuclei. From the surface of the schizont, tens of thousands of haploid (1n) daughter cells called merozoites emerge. The liver stage can produce up to 90,000 merozoites, which are eventually released into the bloodstream in parasite-filled vesicles called merosomes.

Blood stage or erythrocytic schizogony

Merozoites use the apicomplexan invasion organelles ( apical complex, pellicle, and surface coat) to recognize and enter the host erythrocyte (red blood cell

Red blood cells (RBCs), referred to as erythrocytes (, with -''cyte'' translated as 'cell' in modern usage) in academia and medical publishing, also known as red cells, erythroid cells, and rarely haematids, are the most common type of blood cel ...

). The merozoites first bind to the erythrocyte in a random orientation. It then reorients such that the apical complex is in proximity to the erythrocyte membrane. The parasite forms a parasitophorous vacuole, to allow for its development inside the erythrocyte

Red blood cells (RBCs), referred to as erythrocytes (, with -''cyte'' translated as 'cell' in modern usage) in academia and medical publishing, also known as red cells, erythroid cells, and rarely haematids, are the most common type of blood ce ...

. This infection cycle occurs in a highly synchronous fashion, with roughly all of the parasites throughout the blood in the same stage of development. This precise clocking mechanism is dependent on the human host's own circadian rhythm

A circadian rhythm (), or circadian cycle, is a natural oscillation that repeats roughly every 24 hours. Circadian rhythms can refer to any process that originates within an organism (i.e., Endogeny (biology), endogenous) and responds to the env ...

.

Within the erythrocyte, the parasite metabolism depends on the digestion of haemoglobin

Hemoglobin (haemoglobin, Hb or Hgb) is a protein containing iron that facilitates the transportation of oxygen in red blood cells. Almost all vertebrates contain hemoglobin, with the sole exception of the fish family Channichthyidae. Hemoglobi ...

. The clinical symptoms of malaria such as fever, anemia, and neurological disorder are produced during the blood stage.

The parasite can also alter the morphology of the erythrocyte, causing knobs on the erythrocyte membrane. Infected erythrocytes are often sequestered in various human tissues or organs, such as the heart, liver, and brain. This is caused by parasite-derived cell surface proteins being present on the erythrocyte membrane, and it is these proteins that bind to receptors in human cells. Sequestration in the brain causes cerebral malaria, a very severe form of the disease, which increases the victim's likelihood of death.

=Trophozoite

= After invading the erythrocyte, the parasite loses its specific invasion organelles (apical complex and surface coat) and de-differentiates into a round trophozoite located within a parasitophorous vacuole. The trophozoite feeds on the haemoglobin of the erythrocyte, digesting its proteins and converting (by biocrystallization) the remaining heme into insoluble and chemically inert β-hematin crystals called haemozoin. The young trophozoite (or "ring" stage, because of its morphology on stained blood films) grows substantially before undergoing multiplication.=Schizont

= At the schizont stage, the parasite replicates its DNA multiple times and multiple mitotic divisions occur asynchronously. Cell division and multiplication in the erythrocyte is called erythrocytic schizogony. Each schizont forms 16-18 merozoites. The red blood cells are ruptured by the merozoites. The liberated merozoites invade fresh erythrocytes. A free merozoite is in the bloodstream for roughly 60 seconds before it enters another erythrocyte. The duration of one complete erythrocytic schizogony is approximately 48 hours. This gives rise to the characteristic clinical manifestations of falciparum malaria, such as fever and chills, corresponding to the synchronous rupture of the infected erythrocytes.=Gametocyte

= Some merozoites differentiate into sexual forms, male and femalegametocyte

A gametocyte is a eukaryotic germ cell that divides by mitosis into other gametocytes or by meiosis into gametids during gametogenesis. Male gametocytes are called ''spermatocytes'', and female gametocytes are called ''oocytes''.

Development

T ...

s. These gametocytes take roughly 7–15 days to reach full maturity, through the process called gametocytogenesis. These are then taken up by a female ''Anopheles'' mosquito during a blood meal.

Incubation period

The time of appearance of the symptoms from infection (calledincubation period

Incubation period (also known as the latent period or latency period) is the time elapsed between exposure to a pathogenic organism, a chemical, or ionizing radiation, radiation, and when symptoms and signs are first apparent. In a typical infect ...

) is shortest for ''P. falciparum'' among ''Plasmodium'' species. An average incubation period is 11 days, but may range from 9 to 30 days. In isolated cases, prolonged incubation periods as long as 2, 3 or even 8 years have been recorded. Pregnancy and co-infection with HIV are important conditions for delayed symptoms. Parasites can be detected from blood samples by the 10th day after infection (pre-patent period).

In mosquitoes

Within the mosquito midgut, the female gamete maturation process entails slight morphological changes, becoming more enlarged and spherical. The male gametocyte undergoes a rapid nuclear division within 15 minutes, producing eight flagellated microgametes by a process called exflagellation. The flagellated microgamete fertilizes the female macrogamete to produce adiploid

Ploidy () is the number of complete sets of chromosomes in a cell, and hence the number of possible alleles for autosomal and pseudoautosomal genes. Here ''sets of chromosomes'' refers to the number of maternal and paternal chromosome copies, ...

cell called a zygote

A zygote (; , ) is a eukaryote, eukaryotic cell (biology), cell formed by a fertilization event between two gametes.

The zygote's genome is a combination of the DNA in each gamete, and contains all of the genetic information of a new individ ...

. The zygote then develops into an ookinete. The ookinete is a motile cell, capable of invading other organs of the mosquito. It traverses the peritrophic membrane of the mosquito midgut and crosses the midgut epithelium. Once through the epithelium, the ookinete enters the basal lamina

The basal lamina is a layer of extracellular matrix secreted by the epithelial cells, on which the epithelium sits. It is often incorrectly referred to as the basement membrane, though it does constitute a portion of the basement membrane. The b ...

and settles into an immotile oocyst. For several days, the oocyst undergoes 10 to 11 rounds of cell division to create a syncytial

A syncytium (; : syncytia; from Greek: σύν ''syn'' "together" and κύτος ''kytos'' "box, i.e. cell") or symplasm is a multinucleate cell that can result from multiple cell fusions of uninuclear cells (i.e., cells with a single nucleus), in ...

cell ( sporoblast) containing thousands of nuclei. Meiosis takes place inside the sporoblast to produce over 3,000 haploid daughter cells called sporozoites on the surface of the mother cell. Immature sporozoites break through the oocyst wall into the haemolymph

Hemolymph, or haemolymph, is a fluid, similar to the blood in invertebrates, that circulates in the inside of the arthropod's body, remaining in direct contact with the animal's tissues. It is composed of a fluid plasma in which hemolymph ce ...

. They migrate to the mosquito salivary glands where they undergo further development and become infective to humans.

Effects of plant secondary metabolites on ''P. falciparum''

Mosquitoes are known to forage on plant nectar for sugar meal, the primary source of energy and nutrients for their survival and other biological process such as host seeking for blood or searching for oviposition sites. Researchers have recently discovered that mosquitoes are very selective about their sugar meal sources. For example ''Anopheles'' mosquitos prefer some plants over others, specifically those containing compounds that hinder the development and survival of malaria parasites inside the mosquito. This discovery offers an opportunity to look into what could be playing a role in these behavior changes in mosquitoes and also find out what they ingest when they foraged on the selected plants. In other studies, it has been shown that sources of sugars and some secondary metabolites e.g. ricinine, have contrasting effects on mosquito capacity to transmit the parasites malaria.

Meiosis

''Plasmodium falciparum'' ishaploid

Ploidy () is the number of complete sets of chromosomes in a cell (biology), cell, and hence the number of possible alleles for Autosome, autosomal and Pseudoautosomal region, pseudoautosomal genes. Here ''sets of chromosomes'' refers to the num ...

(one set of chromosomes) during its reproductive stages in human blood and liver. When a mosquito takes a blood meal from a plasmodium

''Plasmodium'' is a genus of unicellular eukaryotes that are obligate parasites of vertebrates and insects. The life cycles of ''Plasmodium'' species involve development in a Hematophagy, blood-feeding insect host (biology), host which then inj ...

infected human host, this meal may include haploid microgamete

A gamete ( ) is a Ploidy#Haploid and monoploid, haploid cell that fuses with another haploid cell during fertilization in organisms that Sexual reproduction, reproduce sexually. Gametes are an organism's reproductive cells, also referred to as s ...

s and macrogamete

A gamete ( ) is a Ploidy#Haploid and monoploid, haploid cell that fuses with another haploid cell during fertilization in organisms that Sexual reproduction, reproduce sexually. Gametes are an organism's reproductive cells, also referred to as s ...

s. Such gametes can fuse within the mosquito to form a diploid (2N) plasmodium zygote

A zygote (; , ) is a eukaryote, eukaryotic cell (biology), cell formed by a fertilization event between two gametes.

The zygote's genome is a combination of the DNA in each gamete, and contains all of the genetic information of a new individ ...

, the only diploid stage in the life cycle of these parasites. The zygote can undergo another round of chromosome

A chromosome is a package of DNA containing part or all of the genetic material of an organism. In most chromosomes, the very long thin DNA fibers are coated with nucleosome-forming packaging proteins; in eukaryotic cells, the most import ...

replication to form an ookinete (4N) (see Figure: Life cycle of plasmodium). The ookinete that differentiates from the zygote is a highly mobile stage that invades the mosquito midgut. The ookinetes can undergo meiosis

Meiosis () is a special type of cell division of germ cells in sexually-reproducing organisms that produces the gametes, the sperm or egg cells. It involves two rounds of division that ultimately result in four cells, each with only one c ...

involving two meiotic divisions leading to the release of haploid sporozoites (see Figure). The sporozoite is an elongated crescent-shaped invasive stage. These sporozoites may migrate to the mosquito’s salivary glands and can enter a human host when the mosquito takes a blood meal. The sporozoite then can move to the human host liver and infect hepatocyte

A hepatocyte is a cell of the main parenchymal tissue of the liver. Hepatocytes make up 80% of the liver's mass.

These cells are involved in:

* Protein synthesis

* Protein storage

* Transformation of carbohydrates

* Synthesis of cholesterol, bi ...

s.

The profile of genes encoded by plasmodium that are employed in meiosis has some overlap with the profile of genes employed in meiosis in other more well-studied organisms, but is more divergent and is lacking some components of the meiotic process found in other organisms. During plasmodium meiosis, recombination occurs between homologous chromosomes as in other organisms.

Interaction with human immune system

Immune response

A single anopheline mosquito can transmit hundreds of ''P. falciparum'' sporozoites in a single bite under experimental conditions, but, in nature, the number is generally less than 80. The sporozoites do not enter the bloodstream directly, but rather remain in the skin for two to three hours. About 15–20% of the sporozoites enter the lymphatic system, where they activatedendritic cells

A dendritic cell (DC) is an antigen-presenting cell (also known as an ''accessory cell'') of the mammalian immune system. A DC's main function is to process antigen material and present it on the cell surface to the T cells of the immune system ...

, which send them for destruction by T lymphocytes ( CD8+ T cells). At 48 hours after infection, ''Plasmodium''-specific CD8+ T cells can be detected in the lymph nodes

A lymph node, or lymph gland, is a kidney-shaped Organ (anatomy), organ of the lymphatic system and the adaptive immune system. A large number of lymph nodes are linked throughout the body by the lymphatic vessels. They are major sites of lymphoc ...

connected to the skin cells. Most of the sporozoites remaining in the skin tissue are subsequently killed by the innate immune system

The innate immune system or nonspecific immune system is one of the two main immunity strategies in vertebrates (the other being the adaptive immune system). The innate immune system is an alternate defense strategy and is the dominant immune s ...

. The sporozoite glycoprotein specifically activates mast cells

A mast cell (also known as a mastocyte or a labrocyte) is a resident cell of connective tissue that contains many granules rich in histamine and heparin. Specifically, it is a type of granulocyte derived from the myeloid stem cell that is a ...

. The mast cells then produce signaling molecules such as TNFα and MIP-2, which activate cell eaters (professional phagocytes) such as neutrophils and macrophages

Macrophages (; abbreviated MPhi, φ, MΦ or MP) are a type of white blood cell of the innate immune system that engulf and digest pathogens, such as cancer cells, microbes, cellular debris and foreign substances, which do not have proteins that ...

.

Only a small number (0.5-5%) of sporozoites enter the bloodstream into the liver. In the liver, the activated CD8+ T cells from the lymph bind the sporozoites through the circumsporozoite protein (CSP). Antigen presentation

Antigen presentation is a vital immune process that is essential for T cell immune response triggering. Because T cells recognize only fragmented antigens displayed on cell surfaces, antigen processing must occur before the antigen fragment can ...

by dendritic cells in the skin tissue to T cells is also a crucial process. From this stage onward, the parasites produce different proteins that help suppress communication of the immune cells. Even at the height of the infection, when red blood cells (RBCs) are ruptured, the immune signals are not strong enough to activate macrophages or natural killer cells.

Immune system evasion

Although ''P. falciparum'' is easily recognized by the human immune system while in the bloodstream, it evades immunity by producing over 2,000 cell membrane antigens. The initial infective stage sporozoites produce circumsporozoite protein (CSP), which binds to hepatocytes. Binding to and entering into the hepatocytes is aided by thrombospondin-related anonymous protein (TRAP). TRAP and other secretory proteins (including sporozoite microneme protein essential for cell traversal 1, SPECT1 and SPECT2) from microneme allow the sporozoite to move through the blood, avoiding immune cells and penetrating hepatocytes. During erythrocyte invasion, merozoites release merozoite cap protein-1 (MCP1), apical membrane antigen 1 (AMA1), erythrocyte-binding antigens (EBA), myosin A tail domain interacting protein (MTIP), and merozoite surface proteins (MSPs). Of these MSPs, MSP1 and MSP2 are primarily responsible for avoiding immune cells. The virulence of ''P. falciparum'' is mediated by erythrocyte membrane proteins, which are produced by the schizonts and trophozoites inside the erythrocytes and are displayed on the erythrocyte membrane. PfEMP1 is the most important, capable of acting as both an antigen and an adhesion molecule.Pathogenicity

The clinical symptoms of falciparum malaria are produced by the rupture and destruction of erythrocytes by the merozoites. High fever, called paroxysm, is the most basic indication. The fever has a characteristic cycle of hot stage, cold stage, and sweating stages. Since each erythrocytic schizogony takes a cycle of 48 hours, i.e., two days, the febrile symptom appears every third day. This is the reason the infection is classically named tertian malignant fever (tertian, a derivative of a Latin word that means "third"). The most common symptoms arefever

Fever or pyrexia in humans is a symptom of an anti-infection defense mechanism that appears with Human body temperature, body temperature exceeding the normal range caused by an increase in the body's temperature Human body temperature#Fever, s ...

(>92% of cases), chills

Chills is a feeling of coldness occurring during a high fever, but sometimes is also a common symptom which occurs alone in specific people. It occurs during fever due to the release of cytokines and prostaglandins as part of the inflammatory ...

(79%), headaches

A headache, also known as cephalalgia, is the symptom of pain in the face, head, or neck. It can occur as a migraine, tension-type headache, or cluster headache. There is an increased risk of depression in those with severe headaches.

Head ...

(70%), and sweating (64%). Dizziness

Dizziness is an imprecise term that can refer to a sense of disorientation in space, vertigo, or lightheadedness. It can also refer to Balance disorder, disequilibrium or a non-specific feeling, such as giddiness or foolishness.

Dizziness is a ...

, malaise

In medicine, malaise is a feeling of general discomfort, uneasiness or lack of wellbeing and often the first sign of an infection or other disease. It is considered a vague termdescribing the state of simply not feeling well. The word has exist ...

, muscle pain, abdominal pain

Abdominal pain, also known as a stomach ache, is a symptom associated with both non-serious and serious medical issues. Since the abdomen contains most of the body's vital organs, it can be an indicator of a wide variety of diseases. Given th ...

, nausea

Nausea is a diffuse sensation of unease and discomfort, sometimes perceived as an urge to vomit. It can be a debilitating symptom if prolonged and has been described as placing discomfort on the chest, abdomen, or back of the throat.

Over 30 d ...

, vomiting

Vomiting (also known as emesis, puking and throwing up) is the forceful expulsion of the contents of one's stomach through the mouth and sometimes the nose.

Vomiting can be the result of ailments like food poisoning, gastroenteritis, pre ...

, mild diarrhea

Diarrhea (American English), also spelled diarrhoea or diarrhœa (British English), is the condition of having at least three loose, liquid, or watery bowel movements in a day. It often lasts for a few days and can result in dehydration d ...

, and dry cough are also generally associated. High heartrate, jaundice

Jaundice, also known as icterus, is a yellowish or, less frequently, greenish pigmentation of the skin and sclera due to high bilirubin levels. Jaundice in adults is typically a sign indicating the presence of underlying diseases involving ...

, pallor

Pallor is a pale color of the skin that can be caused by illness, emotional shock or stress, stimulant use, or anemia, and is the result of a reduced amount of oxyhaemoglobin and may also be visible as pallor of the conjunctivae of the eye ...

, orthostatic hypotension

Orthostatic hypotension, also known as postural hypotension, is a medical condition wherein a person's blood pressure drops when they are standing up ( orthostasis) or sitting down. Primary orthostatic hypotension is also often referred to as ne ...

, enlarged liver, and enlarged spleen are also diagnosed.

The insoluble β-hematin crystal, haemozoin, produced from the digestion of haemoglobin of the RBCs is the main agent that affects body organs. Acting as a blood toxin, haemozoin-containing RBCs cannot be attacked by phagocytes during the immune response to malaria. The phagocytes can ingest free haemozoins liberated after the rupture of RBCs by which they are induced to initiate chains of inflammatory reaction that results in increased fever. It is the haemozoin that is deposited in body organs such as the spleen and liver, as well as in kidneys and lungs, to cause their enlargement and discolouration. Because of this, haemozoin is also known as malarial pigment.

Unlike other forms of malaria, which show regular periodicity of fever, falciparum, though exhibiting a 48-hour cycle, usually presents as irregular bouts of fever''.'' This difference is due to the ability of ''P. falciparum'' merozoites to invade a large number of RBCs sequentially without coordinated intervals, which is not seen in other malarial parasites. ''P. falciparum'' is therefore responsible for almost all severe human illnesses and deaths due to malaria, in a condition called pernicious or complicated or severe malaria. Complicated malaria occurs more commonly in children under age 5, and sometimes in pregnant women (a condition specifically called pregnancy-associated malaria). Women become susceptible to severe malaria during their first pregnancy. Susceptibility to severe malaria is reduced in subsequent pregnancies due to increased antibody levels against variant surface antigens

In immunology, an antigen (Ag) is a molecule, moiety, foreign particulate matter, or an allergen, such as pollen, that can bind to a specific antibody or T-cell receptor. The presence of antigens in the body may trigger an immune response.

An ...

that appear on infected erythrocytes. But increased immunity in the mother increases susceptibility to malaria in newborn babies.

''P. falciparum'' works via sequestration, a process by which group of infected RBCs are clustered, which is not exhibited by any other species of malarial parasites. The mature schizonts change the surface properties of infected erythrocytes, causing them to stick to blood vessel walls (cytoadherence). This leads to obstruction of the microcirculation and results in dysfunction of multiple organs, such as the brain in cerebral malaria

Malaria is a mosquito-borne infectious disease that affects vertebrates and '' Anopheles'' mosquitoes. Human malaria causes symptoms that typically include fever, fatigue, vomiting, and headaches. In severe cases, it can cause jaundice, s ...

.

Cerebral malaria is the most dangerous condition of any malarial infection and the most severe form of neurological disorders

Neurological disorders represent a complex array of medical conditions that fundamentally disrupt the functioning of the nervous system. These Disorder of consciousness, disorders affect the brain, spinal cord, and nerve networks, presenting unique ...

. According to the WHO definition, the clinical symptom is indicated by coma and diagnosis by a high level of merozoites in the peripheral blood samples. It is the deadliest form of malaria, and to it are attributed to 0.2 million to over a million annual deaths throughout the ages. Most deaths are of children of below 5 years of age. It occurs when the merozoites invade the brain and cause brain damage of varying degrees. Death is caused by oxygen deprivation (hypoxia) due to inflammatory cytokine production and vascular leakage induced by the merozoites. Among the surviving individuals, persistent medical conditions such as neurological impairment, intellectual disability

Intellectual disability (ID), also known as general learning disability (in the United Kingdom), and formerly mental retardation (in the United States), Rosa's Law, Pub. L. 111-256124 Stat. 2643(2010).Archive is a generalized neurodevelopmental ...

, and behavioural problems exist. Among them, epilepsy

Epilepsy is a group of Non-communicable disease, non-communicable Neurological disorder, neurological disorders characterized by a tendency for recurrent, unprovoked Seizure, seizures. A seizure is a sudden burst of abnormal electrical activit ...

is the most common condition, and cerebral malaria is the leading cause of acquired epilepsy among African children.

The reappearance of falciparum symptom, a phenomenon called recrudescence, is often seen in survivors. Recrudescence can occur even after successful antimalarial medication. It may take a few months or even several years. In some individuals, it takes as long as three years. In isolated cases, the duration can reach or exceed 10 years. It is also a common incident among pregnant women.

Distribution and epidemiology

''P. falciparum'' is endemic in 84 countries, and is found in all continents except Europe. Historically, it was present in most European countries, but improved health conditions led to the disappearance in the early 20th century. The only European country where it used to be historically prevalent, and from where we got the name malaria, Italy had been declared malaria-eradicated country. In 1947, the Italian government launched the National Malaria Eradication Program, and following, an anti-mosquito campaign was implemented using DDT. The WHO declared Italy free of malaria in 1970. There were an estimated 263 million cases of malaria worldwide in 2023, resulting in an estimated 597,000 deaths. The infection is most prevalent in Africa, where 95% of malaria deaths occur. Children under five years of age are most affected, and 67% of malaria deaths occurred in this age group. 80% of the infection is found in Sub-Saharan Africa, 7% in South-East Asia, and 2% in the Eastern Mediterranean. Nigeria has the highest incidence, with 27% of the total global cases. Outside Africa, India has the highest incidence, with 4.5% of the global burden. Europe is regarded as a malaria-free region. Historically, the parasite and its disease had been most well-known in Europe. But medical programmes since the early 20th century, such as insecticide spraying, drug therapy, and environmental engineering, resulted in complete eradication in the 1970s. It is estimated that approximately 2.4 billion people are at constant risk of infection.Treatment

History

In 1640, Huan del Vego first employed thetincture

A tincture is typically an extract of plant or animal material dissolved in ethanol (ethyl alcohol). Solvent concentrations of 25–60% are common, but may run as high as 90%.Groot Handboek Geneeskrachtige Planten by Geert Verhelst In chemistr ...

of the cinchona

''Cinchona'' (pronounced or ) is a genus of flowering plants in the family Rubiaceae containing at least 23 species of trees and shrubs. All are native to the Tropical Andes, tropical Andean forests of western South America. A few species are ...

bark for treating malaria; the native Indians of Peru

Peru, officially the Republic of Peru, is a country in western South America. It is bordered in the north by Ecuador and Colombia, in the east by Brazil, in the southeast by Bolivia, in the south by Chile, and in the south and west by the Pac ...

and Ecuador had been using it even earlier for treating fevers. Thompson (1650) introduced this "Jesuits

The Society of Jesus (; abbreviation: S.J. or SJ), also known as the Jesuit Order or the Jesuits ( ; ), is a religious order (Catholic), religious order of clerics regular of pontifical right for men in the Catholic Church headquartered in Rom ...

' bark" to England

England is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is located on the island of Great Britain, of which it covers about 62%, and List of islands of England, more than 100 smaller adjacent islands. It ...

. Its first recorded use there was by John Metford of Northampton

Northampton ( ) is a town and civil parish in Northamptonshire, England. It is the county town of Northamptonshire and the administrative centre of the Unitary authorities of England, unitary authority of West Northamptonshire. The town is sit ...

in 1656. Morton (1696) presented the first detailed description of the clinical picture of malaria and of its treatment with cinchona. Gize (1816) studied the extraction of crystalline quinine

Quinine is a medication used to treat malaria and babesiosis. This includes the treatment of malaria due to ''Plasmodium falciparum'' that is resistant to chloroquine when artesunate is not available. While sometimes used for nocturnal leg ...

from the cinchona bark and Pelletier and Caventou (1820) in France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

extracted pure quinine alkaloid

Alkaloids are a broad class of natural product, naturally occurring organic compounds that contain at least one nitrogen atom. Some synthetic compounds of similar structure may also be termed alkaloids.

Alkaloids are produced by a large varie ...

s, which they named quinine and cinchonine

Cinchonine is an alkaloid found in ''Cinchona officinalis''. It is used in asymmetric synthesis in organic chemistry. It is a stereoisomer and pseudo-enantiomer of cinchonidine.

It is structurally similar to quinine, an antimalarial drug.

It i ...

. The total synthesis of quinine was achieved by American chemists R.B. Woodward and W.E. Doering in 1944. Woodward received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1965.

Attempts to make synthetic antimalarials began in 1891. Atabrine, developed in 1933, was used widely throughout the Pacific in World War II, but was unpopular because of its adverse effects. In the late 1930s, the Germans developed chloroquine

Chloroquine is an antiparasitic medication that treats malaria. It works by increasing the levels of heme in the blood, a substance toxic to the malarial parasite. This kills the parasite and stops the infection from spreading. Certain types ...

, which went into use in the North African campaigns. Creating a secret military project called Project 523, Mao Zedong

Mao Zedong pronounced ; traditionally Romanization of Chinese, romanised as Mao Tse-tung. (26December 18939September 1976) was a Chinese politician, revolutionary, and political theorist who founded the People's Republic of China (PRC) in ...

encouraged Chinese scientists to find new antimalarials after seeing the casualties in the Vietnam War. Tu Youyou discovered artemisinin in the 1970s from sweet wormwood ('' Artemisia annua''). This drug became known to Western scientists in the late 1980s and early 1990s and is now a standard treatment. Tu won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 2015.

Uncomplicated malaria

According to WHO guidelines 2010,Guidelines for the treatment of malaria, second editionAuthors: WHO. Number of pages: 194. Publication date: 2010. Languages: English. artemisinin-based combination therapies (ACTs) are the recommended first-line antimalarial treatments for uncomplicated malaria caused by ''P. falciparum''. WHO recommends combinations such as artemether/lumefantrine, artesunate/amodiaquine, artesunate/mefloquine, artesunate/sulfadoxine/pyrimethamine, and dihydroartemisinin/piperaquine. The choice of ACT is based on the level of resistance to the constituents in the combination. Artemisinin and its derivatives are not appropriate for monotherapy. As a second-line antimalarial treatment, when initial treatment does not work, an alternative ACT known to be effective in the region is recommended, such as artesunate plus tetracycline or

doxycycline

Doxycycline is a Broad-spectrum antibiotic, broad-spectrum antibiotic of the Tetracycline antibiotics, tetracycline class used in the treatment of infections caused by bacteria and certain parasites. It is used to treat pneumonia, bacterial p ...

or clindamycin, and quinine

Quinine is a medication used to treat malaria and babesiosis. This includes the treatment of malaria due to ''Plasmodium falciparum'' that is resistant to chloroquine when artesunate is not available. While sometimes used for nocturnal leg ...

plus tetracycline or doxycycline or clindamycin. Any of these combinations is to be given for 7 days. For pregnant women, the recommended first-line treatment during the first trimester is quinine plus clindamycin for 7 days. Artesunate plus clindamycin for 7 days is indicated if this treatment fails. For travellers returning to nonendemic countries, atovaquone/ proguanil, artemether/lumefantrineany and quinine plus doxycycline or clindamycin are recommended.

Severe malaria

For adults,intravenous

Intravenous therapy (abbreviated as IV therapy) is a medical technique that administers fluids, medications and nutrients directly into a person's vein. The intravenous route of administration is commonly used for rehydration or to provide nutr ...

(IV) or intramuscular

Intramuscular injection, often abbreviated IM, is the injection of a substance into a muscle. In medicine, it is one of several methods for parenteral administration of medications. Intramuscular injection may be preferred because muscles hav ...

(IM) artesunate is recommended. Quinine is an acceptable alternative if parenteral artesunate is not available.

For children, especially in the malaria-endemic areas of Africa, artesunate IV or IM, quinine (IV infusion or divided IM injection), and artemether IM are recommended.

Parenteral antimalarials should be administered for a minimum of 24 hours, irrespective of the patient's ability to tolerate oral medication earlier. Thereafter, complete treatment is recommended including a complete course of ACT or quinine plus clindamycin or doxycycline.

Vaccination

RTS,S is the only candidate for the malaria vaccine to have gone through clinical trials. Analysis of the results of the phase III trial (conducted between 2011 and 2016) revealed a rather low efficacy (20-39% depending on age, with up to 50% in 5–17-month aged babies), indicating that the vaccine will not lead to full protection and eradication. On October 6, 2021, the World Health Organization recommended malaria vaccination for children at risk.Cancer

TheInternational Agency for Research on Cancer

The International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC; ) is an intergovernmental agency forming part of the World Health Organization of the United Nations.

Its role is to conduct and coordinate research into the causes of cancer. It also cance ...

(IARC) has classified malaria due to ''P. falciparum'' as a Group 2A carcinogen, meaning that the parasite is probably a cancer-causing agent in humans. Its association with a blood cell (lymphocyte

A lymphocyte is a type of white blood cell (leukocyte) in the immune system of most vertebrates. Lymphocytes include T cells (for cell-mediated and cytotoxic adaptive immunity), B cells (for humoral, antibody-driven adaptive immunity), an ...

) cancer called Burkitt's lymphoma

Burkitt's lymphoma is a cancer of the lymphatic system, particularly B lymphocytes found in the germinal center. It is named after Denis Parsons Burkitt, the Irish surgeon who first described the disease in 1958 while working in equatorial Africa ...

is established. Burkitt's lymphoma was discovered by Denis Burkitt in 1958 by African children, and he later speculated that the cancer was likely due to certain infectious diseases. In 1964, a virus, later called Epstein–Barr virus

The Epstein–Barr virus (EBV), also known as human herpesvirus 4 (HHV-4), is one of the nine known Herpesviridae#Human herpesvirus types, human herpesvirus types in the Herpesviridae, herpes family, and is one of the most common viruses in ...

(EBV) after the discoverers, was identified from the cancer cells. The virus was subsequently proved to be the direct cancer agent and is now classified as Group 1 carcinogen.

In 1989, it was realised that EBV requires other infections such as malaria to cause lymphocyte transformation. It was reported that the incidence of Burkitt's lymphoma decreased with effective treatment of malaria over several years. The actual role played by ''P. falciparum'' remained unclear for the next two-and-half decades. EBV had been known to induce lymphocytes to become cancerous using its viral proteins (antigens such as EBNA-1, EBNA-2, LMP1, and LMP2A). From 2014, it became clear that ''P. falciparum'' contributes to the development of the lymphoma. ''P. falciparum''-infected erythrocytes directly bind to B lymphocytes through the CIDR1α domain of PfEMP1. This binding activates toll-like receptors

Toll-like receptors (TLRs) are a class of proteins that play a key role in the innate immune system. They are single-pass membrane protein, single-spanning receptor (biochemistry), receptors usually expressed on sentinel cells such as macrophages ...

( TLR7 and TLR10) causing continuous activation of lymphocytes to undergo proliferation and differentiation into plasma cells, thereby increasing the secretion of IgM and cytokines

Cytokines () are a broad and loose category of small proteins (~5–25 kDa) important in cell signaling.

Cytokines are produced by a broad range of cells, including immune cells like macrophages, B cell, B lymphocytes, T cell, T lymphocytes ...

. This, in turn, activates an enzyme called activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID), which tends to cause mutation in the DNA (by double-strand break) of EBV-infected lymphocytes. The damaged DNA undergoes uncontrolled replication, thus making the cell cancerous.

Influence on the human genome

The high mortality andmorbidity

A disease is a particular abnormal condition that adversely affects the structure or function of all or part of an organism and is not immediately due to any external injury. Diseases are often known to be medical conditions that are asso ...

caused by ''P. falciparum'' has placed great selective pressure on the human genome

The human genome is a complete set of nucleic acid sequences for humans, encoded as the DNA within each of the 23 distinct chromosomes in the cell nucleus. A small DNA molecule is found within individual Mitochondrial DNA, mitochondria. These ar ...

. Several genetic factors provide some resistance to ''Plasmodium'' infection, including sickle cell trait, thalassaemia traits, glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency

Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency (G6PDD), also known as favism, is the most common enzyme deficiency anemia worldwide. It is an inborn error of metabolism that predisposes to red blood cell breakdown. Most of the time, those who ar ...

, and the absence of Duffy antigen

Duffy antigen/chemokine receptor (DARC), also known as Fy glycoprotein (FY) or CD234 (Cluster of Differentiation 234), is a protein that in humans is encoded by the ''ACKR1'' gene.

The Duffy antigen is located on the surface of red blood cells, ...

s on red blood cells. E. A. Beet, a doctor working in Southern Rhodesia

Southern Rhodesia was a self-governing British Crown colony in Southern Africa, established in 1923 and consisting of British South Africa Company (BSAC) territories lying south of the Zambezi River. The region was informally known as South ...

(now Zimbabwe

file:Zimbabwe, relief map.jpg, upright=1.22, Zimbabwe, relief map

Zimbabwe, officially the Republic of Zimbabwe, is a landlocked country in Southeast Africa, between the Zambezi and Limpopo Rivers, bordered by South Africa to the south, Bots ...

) had observed in 1948 that sickle-cell disease

Sickle cell disease (SCD), also simply called sickle cell, is a group of inherited haemoglobin-related blood disorders. The most common type is known as sickle cell anemia. Sickle cell anemia results in an abnormality in the oxygen-carrying ...

was related to a lower rate of malaria infections. This suggestion was reiterated by J. B. S. Haldane in 1948, who suggested that thalassaemia might provide similar protection. This hypothesis has since been confirmed and extended to hemoglobin E and hemoglobin C.

See also

* Malaria Atlas Project * List of parasites (human) * UCSC Malaria Genome BrowserReferences

Further reading

Colombian scientists develop computational tool to detect ''Plasmodium falciparum'' (in Spanish)

* * * * *

External links

Malaria parasite species info at CDC

Web Atlas of Medical Parasitology

Species profile at Encyclopedia of Life

Taxonomy at UniProt

Profile at Scientists Against Malaria

PlasmoDB: The Plasmodium Genome Resource

UCSC Plasmodium Falciparum Browser

{{Authority control Articles containing video clips IARC Group 2A carcinogens Infectious causes of cancer Malaria falciparum Pathogenic microbes Parasites of humans Protozoal diseases Species described in 1881