People's Republic Of Yemen on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

South Yemen, officially the People's Democratic Republic of Yemen, abbreviated to Democratic Yemen, was a country in

In 1914, following the Anglo-Ottoman Convention of 1913, the British and the Ottomans divided

In 1914, following the Anglo-Ottoman Convention of 1913, the British and the Ottomans divided

The first uprising against the British was in Radfan on 14 October 1963, when 7,000 armed Radfani tribesmen, inspired by the coup in the north, joined the National Liberation Front (NLF) with the goals of turning the tribes of the

The first uprising against the British was in Radfan on 14 October 1963, when 7,000 armed Radfani tribesmen, inspired by the coup in the north, joined the National Liberation Front (NLF) with the goals of turning the tribes of the  By 1965, most western protectorates had fallen to the National Liberation Front. Hadhramaut seemed calm until 1966 because the English presence there was less than its counterpart in the western protectorates. Ali Salem al-Beidh and Haidar al-Attas joined the NLF faction in the eastern protectorates and prevented the sultans of the Kathiri Sultanate and the Qu'aiti Sultanate from entering their sultanates but allowed the Sultan of the Mahra back, in sympathy for his old age. Al-Beidh played a major role in gathering supporters in favor of the NLF in Hadhramaut, taking advantage of the near absence of the British in the eastern protectorates. In February 1966, the British had announced that they would withdraw from Aden and cancel all protection treaties with the sultanates and sheikhdoms by 1968. The announcement came as a shock to the protected sultans and sheiks, with one of the sultans expressing his fear of "being murdered in the street". The insurgents did not trust the promise, reasoning that the British wouldn't be abandoning their important base of Aden "without a real fight." By March 1967, the British had set the date for their departure to be on November of that year.

By 1965, most western protectorates had fallen to the National Liberation Front. Hadhramaut seemed calm until 1966 because the English presence there was less than its counterpart in the western protectorates. Ali Salem al-Beidh and Haidar al-Attas joined the NLF faction in the eastern protectorates and prevented the sultans of the Kathiri Sultanate and the Qu'aiti Sultanate from entering their sultanates but allowed the Sultan of the Mahra back, in sympathy for his old age. Al-Beidh played a major role in gathering supporters in favor of the NLF in Hadhramaut, taking advantage of the near absence of the British in the eastern protectorates. In February 1966, the British had announced that they would withdraw from Aden and cancel all protection treaties with the sultanates and sheikhdoms by 1968. The announcement came as a shock to the protected sultans and sheiks, with one of the sultans expressing his fear of "being murdered in the street". The insurgents did not trust the promise, reasoning that the British wouldn't be abandoning their important base of Aden "without a real fight." By March 1967, the British had set the date for their departure to be on November of that year.

Following Israel's victory in the

Following Israel's victory in the

The sultans tried to negotiate terms with the FLOSY, whom they calculated was the "lesser evil," but it came to little success. At that time, the British had advised the sultans to attend the ongoing Geneva negotiations between the British and the NLF, hoping that the United Nations would arrange a solution for them. The British demands were an orderly handover to the authorities, and that the new state not interfere in the affairs of any country in the Arabian Peninsula. The British were surprised by the presence of people they thought were loyal to them alongside the popular Qahtan. The NLF had used the sultans' absences and toppled the sultanates and made headway in Aden, Hadhramaut, Mahra, and the island of

The sultans tried to negotiate terms with the FLOSY, whom they calculated was the "lesser evil," but it came to little success. At that time, the British had advised the sultans to attend the ongoing Geneva negotiations between the British and the NLF, hoping that the United Nations would arrange a solution for them. The British demands were an orderly handover to the authorities, and that the new state not interfere in the affairs of any country in the Arabian Peninsula. The British were surprised by the presence of people they thought were loyal to them alongside the popular Qahtan. The NLF had used the sultans' absences and toppled the sultanates and made headway in Aden, Hadhramaut, Mahra, and the island of

On 22 June 1969, a radical

On 22 June 1969, a radical  The new government embarked on a programme of nationalisation, introduced central planning, put limits on housing ownership and rent, and implemented land reforms. By 1973, the GDP of South Yemen increased by 25 percent. Despite the conservative environment and resistance, women became legally equal to men,

The new government embarked on a programme of nationalisation, introduced central planning, put limits on housing ownership and rent, and implemented land reforms. By 1973, the GDP of South Yemen increased by 25 percent. Despite the conservative environment and resistance, women became legally equal to men,

On 13 January 1986, a violent struggle began in

On 13 January 1986, a violent struggle began in

South Yemen developed as a Marxist–Leninist, mostly secular society ruled first by the National Front, which later transformed into the ruling Yemeni Socialist Party.

South Yemen developed as a Marxist–Leninist, mostly secular society ruled first by the National Front, which later transformed into the ruling Yemeni Socialist Party.

The only avowedly Marxist–Leninist nation in the Middle East, South Yemen received significant

The only avowedly Marxist–Leninist nation in the Middle East, South Yemen received significant  South Yemen often had an outward foreign policy approach, guided by its state ideology of scientific socialism. This ideological commitment led to its support for ideologically consistent movements within its region. South Yemen would supply the Popular Front for the Liberation of the Occupied Arabian Gulf (PFLOAG), supplying the group with bases in its territory, and logistical and military support for the group, alongside facilitating Soviet aid to PFLOAG. When the PFLOAG began to falter against the Omani government, South Yemen ramped up its support for the group, eventually providing them with Artillery support against the Omani government in 1975, almost dragging the two into conflict. South Yemen also supported the Derg in Ethiopia, once more with the rationale of supporting the growth of a Marxist-Leninist bloc in the

South Yemen often had an outward foreign policy approach, guided by its state ideology of scientific socialism. This ideological commitment led to its support for ideologically consistent movements within its region. South Yemen would supply the Popular Front for the Liberation of the Occupied Arabian Gulf (PFLOAG), supplying the group with bases in its territory, and logistical and military support for the group, alongside facilitating Soviet aid to PFLOAG. When the PFLOAG began to falter against the Omani government, South Yemen ramped up its support for the group, eventually providing them with Artillery support against the Omani government in 1975, almost dragging the two into conflict. South Yemen also supported the Derg in Ethiopia, once more with the rationale of supporting the growth of a Marxist-Leninist bloc in the

Even as Islam eventually took root in Yemen, many traditional customs and laws persisted. Tribal loyalty continued to serve as the primary organizing principle, often taking precedence over both religious and national affiliations. This deep-rooted tribalism was further reinforced by persistent conflicts between rival Islamic sects, which fragmented the religious landscape and hindered the emergence of a unified Islamic identity. Rather than fostering a cohesive sense of community under Islam, these sectarian divisions contributed to a more pragmatic form of faith—one in which religious knowledge was often limited, and adherence to Islamic law was secondary to the authority of tribal customs.

As a result, secular tribal law ( 'urf), rooted in pre-Islamic tradition, remained more influential than Islamic law ( shari'ah). The region's isolation also meant that it escaped the homogenizing administrative reforms imposed by the

Even as Islam eventually took root in Yemen, many traditional customs and laws persisted. Tribal loyalty continued to serve as the primary organizing principle, often taking precedence over both religious and national affiliations. This deep-rooted tribalism was further reinforced by persistent conflicts between rival Islamic sects, which fragmented the religious landscape and hindered the emergence of a unified Islamic identity. Rather than fostering a cohesive sense of community under Islam, these sectarian divisions contributed to a more pragmatic form of faith—one in which religious knowledge was often limited, and adherence to Islamic law was secondary to the authority of tribal customs.

As a result, secular tribal law ( 'urf), rooted in pre-Islamic tradition, remained more influential than Islamic law ( shari'ah). The region's isolation also meant that it escaped the homogenizing administrative reforms imposed by the

Democratic Yemen had a "National Science Day" on 10 September.

According to the

Democratic Yemen had a "National Science Day" on 10 September.

According to the

Women's rights under the socialist government were widely regarded as the most progressive in the region. Following the National Front's (NF) adoption of Marxist-Leninist principles in 1968, the South Yemeni government actively promoted the emancipation of women as part of its broader ideological goals. In 1978, the NF was renamed the Yemeni Socialist Party and implemented a series of social and legal reforms inspired by Eastern European models, many of which directly affected the status of women.

The General Union of Yemeni Women played a central role in advancing gender equality and was closely integrated into both the party and state apparatus. Women from the union held positions across all levels of the ruling party's structure, including representation within its central and regional committees.

Significant legal changes were introduced to dismantle religious and traditional restrictions on women. The 1974 Family Law curtailed polygamy, abolished unilateral male divorce ('' talaq''), upheld a woman's right to child custody after divorce, and prohibited both early and non-consensual marriages. These reforms also banned arranged marriages, and transferred jurisdiction over personal status issues from religious authorities to state institutions. Women were granted full legal equality with men, and equal rights in divorce were codified.

Beyond legislation, the state pursued a broader cultural and social transformation. Women were actively encouraged to participate in sectors traditionally reserved for men, including the military, judiciary, and political spheres. Education and workforce integration were seen as key to achieving women's emancipation. From independence onward, girls and women had access to all levels of education, including technical and vocational training. A major literacy campaign between 1972 and 1976 prioritized female participation. These efforts contributed to South Yemen achieving one of the highest female labor force participation rates in the Arab world at the time.

Women's rights under the socialist government were widely regarded as the most progressive in the region. Following the National Front's (NF) adoption of Marxist-Leninist principles in 1968, the South Yemeni government actively promoted the emancipation of women as part of its broader ideological goals. In 1978, the NF was renamed the Yemeni Socialist Party and implemented a series of social and legal reforms inspired by Eastern European models, many of which directly affected the status of women.

The General Union of Yemeni Women played a central role in advancing gender equality and was closely integrated into both the party and state apparatus. Women from the union held positions across all levels of the ruling party's structure, including representation within its central and regional committees.

Significant legal changes were introduced to dismantle religious and traditional restrictions on women. The 1974 Family Law curtailed polygamy, abolished unilateral male divorce ('' talaq''), upheld a woman's right to child custody after divorce, and prohibited both early and non-consensual marriages. These reforms also banned arranged marriages, and transferred jurisdiction over personal status issues from religious authorities to state institutions. Women were granted full legal equality with men, and equal rights in divorce were codified.

Beyond legislation, the state pursued a broader cultural and social transformation. Women were actively encouraged to participate in sectors traditionally reserved for men, including the military, judiciary, and political spheres. Education and workforce integration were seen as key to achieving women's emancipation. From independence onward, girls and women had access to all levels of education, including technical and vocational training. A major literacy campaign between 1972 and 1976 prioritized female participation. These efforts contributed to South Yemen achieving one of the highest female labor force participation rates in the Arab world at the time.

During British rule, economic development in South Yemen was restricted to the city of

During British rule, economic development in South Yemen was restricted to the city of

Limited natural resources posed challenges to the economic development of the People's Democratic Republic of Yemen (PDRY). Despite this constraint, significant, albeit modest, oil reserves were discovered shortly after the country's unification in 1990. However, the YSP government did not benefit from oil exports to fund its development initiatives.

Over time, economic policies in the PDRY underwent a transformation, shifting from an initial focus on developing the state sector to promoting cooperative and joint private-public enterprises. By the late 1980s, there was a notable presence of industries in Aden and around Al Mukalla in Hadramawt, producing a range of essential goods such as plastics, batteries, cigarettes, matches, tomato paste, dairy products, and fish canning.

Within the industrial sector, the state implemented welfarist labor laws that were widely enforced. These laws included regulations aimed at safeguarding women in the workforce by prohibiting night shifts and hazardous occupations. Additionally, the legislation ensured that workers received salaries that enabled them to maintain reasonable living standards. Trade unions in the PDRY primarily functioned as state entities rather than as negotiating bodies, playing a significant role in upholding labor regulations and standards.

Limited natural resources posed challenges to the economic development of the People's Democratic Republic of Yemen (PDRY). Despite this constraint, significant, albeit modest, oil reserves were discovered shortly after the country's unification in 1990. However, the YSP government did not benefit from oil exports to fund its development initiatives.

Over time, economic policies in the PDRY underwent a transformation, shifting from an initial focus on developing the state sector to promoting cooperative and joint private-public enterprises. By the late 1980s, there was a notable presence of industries in Aden and around Al Mukalla in Hadramawt, producing a range of essential goods such as plastics, batteries, cigarettes, matches, tomato paste, dairy products, and fish canning.

Within the industrial sector, the state implemented welfarist labor laws that were widely enforced. These laws included regulations aimed at safeguarding women in the workforce by prohibiting night shifts and hazardous occupations. Additionally, the legislation ensured that workers received salaries that enabled them to maintain reasonable living standards. Trade unions in the PDRY primarily functioned as state entities rather than as negotiating bodies, playing a significant role in upholding labor regulations and standards.

The following airlines had operated from the PDRY:

* Alyemda – Democratic Yemen Airlines (1961–1996). Joined Yemenia, the airline of the former YAR.

*The Brothers Air Services was formed by Sayid Zein A. Baharoon who used the "Brothers" nomenclature in his merchant enterprises. Known as BASCO, this fledgling airline lasted only a short time.

The following airlines had operated from the PDRY:

* Alyemda – Democratic Yemen Airlines (1961–1996). Joined Yemenia, the airline of the former YAR.

*The Brothers Air Services was formed by Sayid Zein A. Baharoon who used the "Brothers" nomenclature in his merchant enterprises. Known as BASCO, this fledgling airline lasted only a short time.

South Yemen Anthem (1969–1979)

National anthem of Yemen (second and last anthem of South Yemen)

Constitution of the People's Democratic Republic of Yemen

(as amended 31 October 1978) * Th

PDRY Archives

(in Arabic) of Ali Nasir Muhammad {{coord, 12, 48, N, 45, 02, E, type:country, display=title

South Arabia

South Arabia (), or Greater Yemen, is a historical region that consists of the southern region of the Arabian Peninsula in West Asia, mainly centered in what is now the Republic of Yemen, yet it has also historically included Najran, Jazan, ...

that existed in what is now southeast Yemen

Yemen, officially the Republic of Yemen, is a country in West Asia. Located in South Arabia, southern Arabia, it borders Saudi Arabia to Saudi Arabia–Yemen border, the north, Oman to Oman–Yemen border, the northeast, the south-eastern part ...

from 1967 until its unification with the Yemen Arab Republic in 1990. The sole communist state

A communist state, also known as a Marxist–Leninist state, is a one-party state in which the totality of the power belongs to a party adhering to some form of Marxism–Leninism, a branch of the communist ideology. Marxism–Leninism was ...

in the Middle East

The Middle East (term originally coined in English language) is a geopolitical region encompassing the Arabian Peninsula, the Levant, Turkey, Egypt, Iran, and Iraq.

The term came into widespread usage by the United Kingdom and western Eur ...

and the Arab world

The Arab world ( '), formally the Arab homeland ( '), also known as the Arab nation ( '), the Arabsphere, or the Arab states, comprises a large group of countries, mainly located in West Asia and North Africa. While the majority of people in ...

, it comprised the southern and eastern governorates of the present-day Republic of Yemen, including the Socotra Archipelago. It bordered the Yemen Arab Republic to the northwest, Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia, officially the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA), is a country in West Asia. Located in the centre of the Middle East, it covers the bulk of the Arabian Peninsula and has a land area of about , making it the List of Asian countries ...

to the north, Oman

Oman, officially the Sultanate of Oman, is a country located on the southeastern coast of the Arabian Peninsula in West Asia and the Middle East. It shares land borders with Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and Yemen. Oman’s coastline ...

to the east, the Arabian Sea

The Arabian Sea () is a region of sea in the northern Indian Ocean, bounded on the west by the Arabian Peninsula, Gulf of Aden and Guardafui Channel, on the northwest by Gulf of Oman and Iran, on the north by Pakistan, on the east by India, and ...

to the southeast, and the Gulf of Aden

The Gulf of Aden (; ) is a deepwater gulf of the Indian Ocean between Yemen to the north, the Arabian Sea to the east, Djibouti to the west, and the Guardafui Channel, the Socotra Archipelago, Puntland in Somalia and Somaliland to the south. ...

to the south. Its capital and largest city was Aden

Aden () is a port city located in Yemen in the southern part of the Arabian peninsula, on the north coast of the Gulf of Aden, positioned near the eastern approach to the Red Sea. It is situated approximately 170 km (110 mi) east of ...

.

South Yemen's origins can be traced to 1874 with the creation of the British Colony of Aden and the Aden Protectorate, which consisted of two-thirds of present-day Yemen. Prior to 1937, what was to become the Colony of Aden had been governed as a part of British India, originally as the Aden Settlement subordinate to the Bombay Presidency and then as a Chief Commissioner's province. After the collapse of Aden Protectorate, a state of emergency was declared in 1963, when the National Liberation Front (NLF) and the Front for the Liberation of Occupied South Yemen (FLOSY) rebelled against the British rule. The Federation of South Arabia

The Federation of South Arabia (FSA; ') was a federal state under British protectorate, British protection in what would become South Yemen. Its capital was Aden.

History

Originally formed on April 4, 1962 from 15 states of the Federation ...

and the Protectorate of South Arabia were overthrown to become the People's Republic of Southern Yemen (PRSY) on 30 November 1967.

On 22 June 1969, the Marxist–Leninist faction of the NLF led by Abdel Fattah Ismail and Salim Rubai Ali, overthrew the Nasserist President Qahtan al-Shaabi in an internal bloodless coup that was later called the Corrective Move. The Marxist–Leninist takeover later led to the creation of the Yemeni Socialist Party (YSP), and South Yemen's transformation into a one-party, socialist state

A socialist state, socialist republic, or socialist country is a sovereign state constitutionally dedicated to the establishment of socialism. This article is about states that refer to themselves as socialist states, and not specifically ...

. The official name of the state was changed a year after the reforms to the People's Democratic Republic of Yemen (PDRY), and was able to establish strong relations with Cuba

Cuba, officially the Republic of Cuba, is an island country, comprising the island of Cuba (largest island), Isla de la Juventud, and List of islands of Cuba, 4,195 islands, islets and cays surrounding the main island. It is located where the ...

, East Germany

East Germany, officially known as the German Democratic Republic (GDR), was a country in Central Europe from Foundation of East Germany, its formation on 7 October 1949 until German reunification, its reunification with West Germany (FRG) on ...

, North Korea

North Korea, officially the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK), is a country in East Asia. It constitutes the northern half of the Korea, Korean Peninsula and borders China and Russia to the north at the Yalu River, Yalu (Amnok) an ...

, China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. With population of China, a population exceeding 1.4 billion, it is the list of countries by population (United Nations), second-most populous country after ...

, and the Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

. Despite its efforts to bring stability into the region, it was involved in a brief civil war in 1986. The PDRY unified with the Yemen Arab Republic, on 22 May 1990 to form the present-day Republic of Yemen.

Background

British arrival in Yemen

The first political intercourse between Yemen and the British took place in 1799 during the French invasion of Egypt and Syria, when a naval force was sent from Britain, with a detachment of troops from India, to occupy the island of Perim and prevent all communication of the French in Egypt with the Indian Ocean, by way of the Red Sea. Due to the lack of water supply, the barren and inhospitable island of Perim was found unsuitable for troops, and the Sultan of Lahej, Ahmed bin Abdul Karim, received the detachment for some time atAden

Aden () is a port city located in Yemen in the southern part of the Arabian peninsula, on the north coast of the Gulf of Aden, positioned near the eastern approach to the Red Sea. It is situated approximately 170 km (110 mi) east of ...

. He proposed to enter into an alliance and to grant Aden as a permanent station, but the offer was declined. A treaty was, however, concluded with the Sultan in 1802 by Admiral Home Popham, who was instructed to enter into political and commercial alliances with the Chiefs of the Arabian coast of the Red Sea. By the early 1800s, the British were looking for a coaling station where they could fuel their steamship

A steamship, often referred to as a steamer, is a type of steam-powered vessel, typically ocean-faring and seaworthy, that is propelled by one or more steam engines that typically move (turn) propellers or paddlewheels. The first steamships ...

s through their journey from the Suez Canal

The Suez Canal (; , ') is an artificial sea-level waterway in Egypt, Indo-Mediterranean, connecting the Mediterranean Sea to the Red Sea through the Isthmus of Suez and dividing Africa and Asia (and by extension, the Sinai Peninsula from the rest ...

to the British Raj

The British Raj ( ; from Hindustani language, Hindustani , 'reign', 'rule' or 'government') was the colonial rule of the British The Crown, Crown on the Indian subcontinent,

*

* lasting from 1858 to 1947.

*

* It is also called Crown rule ...

. The British tried to negotiate with the Mahra Sultanate to buy the island of Socotra

Socotra, locally known as Saqatri, is a Yemeni island in the Indian Ocean. Situated between the Guardafui Channel and the Arabian Sea, it lies near major shipping routes. Socotra is the largest of the six islands in the Socotra archipelago as ...

, located in the Arabian Sea

The Arabian Sea () is a region of sea in the northern Indian Ocean, bounded on the west by the Arabian Peninsula, Gulf of Aden and Guardafui Channel, on the northwest by Gulf of Oman and Iran, on the north by Pakistan, on the east by India, and ...

, but the Sultan

Sultan (; ', ) is a position with several historical meanings. Originally, it was an Arabic abstract noun meaning "strength", "authority", "rulership", derived from the verbal noun ', meaning "authority" or "power". Later, it came to be use ...

of Mahra refused, telling the British naval officer tasked with the mission that the island was "the gift of the Almighty to the Mahris". In 1835, a year after the British had given up on Socotra, they had attempted to purchase the port city of Aden and its inlet

An inlet is a typically long and narrow indentation of a shoreline such as a small arm, cove, bay, sound, fjord, lagoon or marsh, that leads to an enclosed larger body of water such as a lake, estuary, gulf or marginal sea.

Overview

In ...

from the Sultan of Lahej, Muhsin Bin Fadl, but they failed. In 1837, the ''Duria Dawla'', an Indian ship flying the Union Jack

The Union Jack or Union Flag is the ''de facto'' national flag of the United Kingdom. The Union Jack was also used as the official flag of several British colonies and dominions before they adopted their own national flags.

It is sometimes a ...

, crashed near the east coast of Aden and was looted by local tribesmen. A year after the incident, in 1838, British officials arrived in Lahej and demanded 12,000 Maria Theresa thalers (MTT) as compensation for the losses. The sultan, unable to pay that sum of money, was forced to cede Aden to the British for a sum of 8,700 MTT a year. On 19 January 1839, the British East India Company

The East India Company (EIC) was an English, and later British, joint-stock company that was founded in 1600 and dissolved in 1874. It was formed to Indian Ocean trade, trade in the Indian Ocean region, initially with the East Indies (South A ...

landed Royal Marines

The Royal Marines provide the United Kingdom's amphibious warfare, amphibious special operations capable commando force, one of the :Fighting Arms of the Royal Navy, five fighting arms of the Royal Navy, a Company (military unit), company str ...

at Aden

Aden () is a port city located in Yemen in the southern part of the Arabian peninsula, on the north coast of the Gulf of Aden, positioned near the eastern approach to the Red Sea. It is situated approximately 170 km (110 mi) east of ...

to retain full control of Aden and stop attacks by pirates against British shipping to India.

Following the landing in Aden, the British established informal treaties of protection with nine sheikhdoms and sultanates in the surrounding region."Yemen". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica Inc., 2013. Web. 22 September 2013 This was more a precautionary measure to prevent the Imams of Yemen

The Imams of Yemen, later also titled the Kings of Yemen, were religiously consecrated leaders ( imams) belonging to the Zaidi branch of Shia Islam. They established a blend of religious and temporal-political rule in parts of Yemen from 897. T ...

from storming Aden, which was something the sheikhdoms did not want to happen. These agreements allowed the British to maintain control, using the existing tribal structures to assert their influence. Since the region was plagued by frequent tribal conflicts and no single ruler held enough sway to unify the tribes, there was little threat to British dominance. This fragmentation not only prevented any strong opposition but also delayed the formation of a broader national identity. The British, in turn, benefited from a system that was both efficient and inexpensive, spending only around $5,435 a year in subsidies to secure the loyalty of twenty-five sultans. By avoiding direct administration and relying on a policy of strategic dependence, the British were able to expand their influence. By 1914, they had treaties with nearly every sultan in the region.

Partitioning Yemen

In 1914, following the Anglo-Ottoman Convention of 1913, the British and the Ottomans divided

In 1914, following the Anglo-Ottoman Convention of 1913, the British and the Ottomans divided Arabia

The Arabian Peninsula (, , or , , ) or Arabia, is a peninsula in West Asia, situated north-east of Africa on the Arabian plate. At , comparable in size to India, the Arabian Peninsula is the largest peninsula in the world.

Geographically, the ...

into two parts: the northwest under Ottoman control and influence, and the southeast under British control and influence. Although a further agreement, which came to be later known as the Violet Line, was negotiated, the Ottomans planned an invasion of the Aden Protectorate in cooperation with local tribes. They had gathered significant strength at Cheikh Saïd. On 5 November 1914, during the First World War

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, the British declared war on the Ottomans, who responded with their declaration a few days later, on 11 November. Although the Ottomans managed to capture the Sultanate of Lahej and reach the city of Aden, they were later expelled by the British. Around the same time, the British-sponsored Arab Revolt in the Hejaz broke out, diverting Ottoman attention from Aden and effectively ending their campaign. The Armistice of Mudros, signed in 1918, officially concluded the war and forced the Ottomans out of Arabia, leading to the establishment of the Kingdom of Yemen.

During the period between the two World Wars, Aden grew significantly in strategic value to the British. Positioned near the entrance to the Persian Gulf

The Persian Gulf, sometimes called the Arabian Gulf, is a Mediterranean seas, mediterranean sea in West Asia. The body of water is an extension of the Arabian Sea and the larger Indian Ocean located between Iran and the Arabian Peninsula.Un ...

, it played a crucial role in safeguarding maritime routes through the Suez Canal

The Suez Canal (; , ') is an artificial sea-level waterway in Egypt, Indo-Mediterranean, connecting the Mediterranean Sea to the Red Sea through the Isthmus of Suez and dividing Africa and Asia (and by extension, the Sinai Peninsula from the rest ...

and was close to the newly discovered oil reserves in the Arabian Peninsula

The Arabian Peninsula (, , or , , ) or Arabia, is a peninsula in West Asia, situated north-east of Africa on the Arabian plate. At , comparable in size to India, the Arabian Peninsula is the largest peninsula in the world.

Geographically, the ...

. Recognizing its increased importance, Britain formally designated Aden as a Crown Colony

A Crown colony or royal colony was a colony governed by Kingdom of England, England, and then Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain or the United Kingdom within the English overseas possessions, English and later British Empire. There was usua ...

in 1937 and implemented a full colonial administrative system. This move further diminished the authority of local rulers, as Britain took full control over governance and policy decisions. The centralization of power in British hands sparked several small-scale uprisings. In response, Yemeni leaders, often supported by British forces, resorted to harsh and repressive tactics to suppress dissent and maintain order among the tribes.

Beginning of the end of British rule in Yemen

In 1952, Arab nationalism began to sweep across theArab world

The Arab world ( '), formally the Arab homeland ( '), also known as the Arab nation ( '), the Arabsphere, or the Arab states, comprises a large group of countries, mainly located in West Asia and North Africa. While the majority of people in ...

, starting in Egypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

, accompanied by anti-colonial sentiments. Nationalist pressures prompted the rulers of the Aden Protectorate states to renew efforts at forming a federation. On 11 February 1959, six of these states signed an accord to form the Federation of the Emirates of South Arabia. Over the next three years, nine additional sheikhdoms joined, and on 18 January 1963, Aden Colony was merged with the federation, creating the new Federation of South Arabia

The Federation of South Arabia (FSA; ') was a federal state under British protectorate, British protection in what would become South Yemen. Its capital was Aden.

History

Originally formed on April 4, 1962 from 15 states of the Federation ...

(FSA), although all but four sheikhdoms out of twenty-one had joined the union. Meanwhile, the Qu'aiti and Kathiri sultanates of Hadhramaut

Hadhramaut ( ; ) is a geographic region in the southern part of the Arabian Peninsula which includes the Yemeni governorates of Hadhramaut, Shabwah and Mahrah, Dhofar in southwestern Oman, and Sharurah in the Najran Province of Saudi A ...

, along with Mahra, and Upper Yafa

Upper Yafa or Upper Yafa'i ( ''),'' officially the State of Upper Yafa ( '')'', was a military alliance in the British Aden Protectorate and the Protectorate of South Arabia. It was ruled by the Harharah dynasty and its capital was Mahjaba, ...

refused to join either of the federations and became the Protectorate of South Arabia, marking the end of the Aden Protectorate. The FSA did not succeed for several reasons, the first of which was the British insistence that the State of Aden would be part of the entity, which was rejected by the commercial elite of Aden, most of whom were Indians, Persians

Persians ( ), or the Persian people (), are an Iranian ethnic group from West Asia that came from an earlier group called the Proto-Iranians, which likely split from the Indo-Iranians in 1800 BCE from either Afghanistan or Central Asia. They ...

, and Jews

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of History of ancient Israel and Judah, ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, rel ...

, because they feared that Aden's wealth would be taken away by the neighboring sheikhdoms. On the other hand, the leaders of the sheikhdoms had little experience with federal rule and had no desire for cooperation. In addition to all that, there were differences between the sheikhdoms over who should head the federation's new government.

In 26 September 1962, a successful coup carried out against the Kingdom of Yemen by the , supported by Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser

Gamal Abdel Nasser Hussein (15 January 1918 – 28 September 1970) was an Egyptian military officer and revolutionary who served as the second president of Egypt from 1954 until his death in 1970. Nasser led the Egyptian revolution of 1952 a ...

—who had led the Egyptian Revolution of 1952

The Egyptian revolution of 1952, also known as the 1952 coup d'état () and the 23 July Revolution (), was a period of profound political, economic, and societal change in Egypt. On 23 July 1952, the revolution began with the toppling of King ...

against British rule—resulted in the establishment of the Yemen Arab Republic.Sandler, Stanley. ''Ground Warfare: The International Encyclopedia''. Vol. 1 (2002): p. 977. "Egypt immediately began sending military supplies and troops to assist the Republicans... On the royalist side Jordan and Saudi Arabia were furnishing military aid, and Britain lent diplomatic support. In addition to Egyptian aid, the Soviet Union supplied 24 MiG-19s to the republicans." This coup inspired organizations, such as the local branch of the Movement of Arab Nationalists and the Aden Trade Union Congress, to form the National Liberation Front (NLF) and the Front for the Liberation of Occupied South Yemen (FLOSY), respectively. Supporters of the NLF were from the countryside of Radfan, Yafa', and Ad-Dali, while the supporters of the FLOSY were mainly the citizens of Aden. This is because tribal affiliations played a major role in attracting supporters.

History

Decolonization and NLF seizure of power

The first uprising against the British was in Radfan on 14 October 1963, when 7,000 armed Radfani tribesmen, inspired by the coup in the north, joined the National Liberation Front (NLF) with the goals of turning the tribes of the

The first uprising against the British was in Radfan on 14 October 1963, when 7,000 armed Radfani tribesmen, inspired by the coup in the north, joined the National Liberation Front (NLF) with the goals of turning the tribes of the Federation of South Arabia

The Federation of South Arabia (FSA; ') was a federal state under British protectorate, British protection in what would become South Yemen. Its capital was Aden.

History

Originally formed on April 4, 1962 from 15 states of the Federation ...

against the British, and achieving independence through guerrilla warfare

Guerrilla warfare is a form of unconventional warfare in which small groups of irregular military, such as rebels, partisans, paramilitary personnel or armed civilians, which may include recruited children, use ambushes, sabotage, terrori ...

. The strategy of the NLF was to harass and exhaust the British military using hit-and-run tactics

Hit-and-run tactics are a Military tactics, tactical doctrine of using short surprise attacks, withdrawing before the enemy can respond in force, and constantly maneuvering to avoid full engagement with the enemy. The purpose is not to decisive ...

. By 10 December 1963, the uprising had reached Aden

Aden () is a port city located in Yemen in the southern part of the Arabian peninsula, on the north coast of the Gulf of Aden, positioned near the eastern approach to the Red Sea. It is situated approximately 170 km (110 mi) east of ...

. An NLF grenade attack against the High Commissioner of Aden, Kennedy Trevaskis, killed the High Commissioner's adviser and a bystander, and injured fifty other people. On that day, a state of emergency was declared in Aden. On January 1964, the British responded by a 3-month bombing campaign in Radfan, which subdued the insurgents. The insurgency in Radfan began raising questions in the Parliament of the United Kingdom

The Parliament of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland is the supreme legislative body of the United Kingdom, and may also legislate for the Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories. It meets at the Palace ...

on what should the fate of Aden and the protectorates be.

By 1965, most western protectorates had fallen to the National Liberation Front. Hadhramaut seemed calm until 1966 because the English presence there was less than its counterpart in the western protectorates. Ali Salem al-Beidh and Haidar al-Attas joined the NLF faction in the eastern protectorates and prevented the sultans of the Kathiri Sultanate and the Qu'aiti Sultanate from entering their sultanates but allowed the Sultan of the Mahra back, in sympathy for his old age. Al-Beidh played a major role in gathering supporters in favor of the NLF in Hadhramaut, taking advantage of the near absence of the British in the eastern protectorates. In February 1966, the British had announced that they would withdraw from Aden and cancel all protection treaties with the sultanates and sheikhdoms by 1968. The announcement came as a shock to the protected sultans and sheiks, with one of the sultans expressing his fear of "being murdered in the street". The insurgents did not trust the promise, reasoning that the British wouldn't be abandoning their important base of Aden "without a real fight." By March 1967, the British had set the date for their departure to be on November of that year.

By 1965, most western protectorates had fallen to the National Liberation Front. Hadhramaut seemed calm until 1966 because the English presence there was less than its counterpart in the western protectorates. Ali Salem al-Beidh and Haidar al-Attas joined the NLF faction in the eastern protectorates and prevented the sultans of the Kathiri Sultanate and the Qu'aiti Sultanate from entering their sultanates but allowed the Sultan of the Mahra back, in sympathy for his old age. Al-Beidh played a major role in gathering supporters in favor of the NLF in Hadhramaut, taking advantage of the near absence of the British in the eastern protectorates. In February 1966, the British had announced that they would withdraw from Aden and cancel all protection treaties with the sultanates and sheikhdoms by 1968. The announcement came as a shock to the protected sultans and sheiks, with one of the sultans expressing his fear of "being murdered in the street". The insurgents did not trust the promise, reasoning that the British wouldn't be abandoning their important base of Aden "without a real fight." By March 1967, the British had set the date for their departure to be on November of that year.

Following Israel's victory in the

Following Israel's victory in the Six-Day War

The Six-Day War, also known as the June War, 1967 Arab–Israeli War or Third Arab–Israeli War, was fought between Israel and a coalition of Arab world, Arab states, primarily United Arab Republic, Egypt, Syria, and Jordan from 5 to 10June ...

of June 1967, which was considered a humiliation for the Arab world

The Arab world ( '), formally the Arab homeland ( '), also known as the Arab nation ( '), the Arabsphere, or the Arab states, comprises a large group of countries, mainly located in West Asia and North Africa. While the majority of people in ...

, the anti-colonial sentiment was at its all-time high due to Britain's role in the creation of Israel following the First World War

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

. Slogans like "A bullet against Britain is a bullet against Israel" appeared, and attacks against the British had increased. Graffiti of the acronyms of the NLF and FLOSY had filled the streets in Aden, and the infighting between those two groups for power had increased. In the same month, an NLF-directed Arab Police mutiny in Crater ambushed a British military patrol and slaughtered three Argyll & Sutherland Highlanders and captured the city of Crater. The capture of Crater was considered a significant victory for the Arab world. Colin Mitchell, also known as "Mad Mitch," led his battalion back into Crater and retook it with minimal casualties. However, his methods were deemed too extreme, and he was ejected from the army. The battle later came to be known as "the last battle of the British Empire." According to the American consul in Aden, the British handling of the insurgents "evolved from attempting to take them unharmed to summary justice in the streets."

Independence

The sultans tried to negotiate terms with the FLOSY, whom they calculated was the "lesser evil," but it came to little success. At that time, the British had advised the sultans to attend the ongoing Geneva negotiations between the British and the NLF, hoping that the United Nations would arrange a solution for them. The British demands were an orderly handover to the authorities, and that the new state not interfere in the affairs of any country in the Arabian Peninsula. The British were surprised by the presence of people they thought were loyal to them alongside the popular Qahtan. The NLF had used the sultans' absences and toppled the sultanates and made headway in Aden, Hadhramaut, Mahra, and the island of

The sultans tried to negotiate terms with the FLOSY, whom they calculated was the "lesser evil," but it came to little success. At that time, the British had advised the sultans to attend the ongoing Geneva negotiations between the British and the NLF, hoping that the United Nations would arrange a solution for them. The British demands were an orderly handover to the authorities, and that the new state not interfere in the affairs of any country in the Arabian Peninsula. The British were surprised by the presence of people they thought were loyal to them alongside the popular Qahtan. The NLF had used the sultans' absences and toppled the sultanates and made headway in Aden, Hadhramaut, Mahra, and the island of Socotra

Socotra, locally known as Saqatri, is a Yemeni island in the Indian Ocean. Situated between the Guardafui Channel and the Arabian Sea, it lies near major shipping routes. Socotra is the largest of the six islands in the Socotra archipelago as ...

. On 7 November, the Federal Army came out in support of the NLF, and the British government was forced to negotiate a hasty handover. On 20 November, the British government eventually recognized the NLF as the de facto new power in the land, and spent their last 10 days trying to pare down their promised aid from £60 million to £12 million. The last British troops departed eleven hours before the birth of the new People’s Republic of South Yemen at midnight on 29–30 November, marking an end to 128 years of colonial rule, and on 14 December 1967, it was admitted into the United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is the Earth, global intergovernmental organization established by the signing of the Charter of the United Nations, UN Charter on 26 June 1945 with the stated purpose of maintaining international peace and internationa ...

as a member state.

The National Liberation Front had the upper hand at the expense of the Front for the Liberation of Occupied South Yemen, whose members were divided between joining the National Front or leaving for North Yemen. Abdullah Al-Asnag and Mohammed Basindawa left for the Yemen Arab Republic. Qahtan al-Shaabi assumed the presidency of a state that had never existed before, with a collapsed economy. Civilian workers and businessmen left, British support stopped, and the closure of the Suez Canal in 1967 reduced the number of ships crossing Aden by 75%.

On 11 December 1967, the lands of what was called the "feudal

Feudalism, also known as the feudal system, was a combination of legal, economic, military, cultural, and political customs that flourished in Middle Ages, medieval Europe from the 9th to 15th centuries. Broadly defined, it was a way of struc ...

symbols and British agents" were confiscated, and the state was divided into six governorates. The move aimed to end tribal aspects in the state and ignore the tribal borders between the defunct sheikhdoms. On 16 June 1969, Qahtan fired Interior Minister Muhammad Ali Haitham, but the latter withdrew his ties to With the tribes and the army, he was able to ally himself with Muhammad Saleh Al-Awlaki, and they reassembled the leftist forces that President Qahtan Al-Shaabi had dispersed. They were able to arrest him and place him under house arrest.

Reforms and the establishment of a Marxist-Leninist state

The National Liberation Front, now rebranded as the National Front, had approximately 26,000 members, a small number of university-educated leaders, and all of them, without exception, had no experience in government. The front was divided into two right-wing and left-wing sections. The right-wingers and their popular leader, Qahtan, did not want to make major changes in the prevailing social and economic structure and took a conservative stance toward "liberating all Arab lands from colonialism, supporting the resistance of the Palestinian people, and supporting socialist regimes around the world to resist imperialism and colonial forces in the Third World." The leftist faction of the National Front was also promoting and opposing the establishment of popular forces and proposals to nationalize lands, and they were not preoccupied with the struggle of social classes. Qahtan wanted the continuation of existing institutions and their development. The leftist faction "wanted a social and economic transformation that would serve the broad segment of the working people instead of the wealthy minority," as they put it. on 20 March 1968, Qahtan's right-wing faction dismissed all leftist leaders from the government and party membership and was able to put down a rebellion led by leftist factions in the army in May of the same year. In July, August, and December 1968, the popular Qahtan faced new rebellions from leftist parties because all Arab countries welcomed the front. The National Liberation Front received a cold reception, as regimes like Egypt wanted to merge the National Front with the Front for the Liberation of Occupied South Yemen. The leftist faction was more numerous than the supporters of the popular Qahtan, and they wanted a regime that would lead the masses and face the great challenges facing the new state, the most important of which was the bankruptcy of the treasury. On 22 June 1969, a radical

On 22 June 1969, a radical Marxist

Marxism is a political philosophy and method of socioeconomic analysis. It uses a dialectical and materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to analyse class relations, social conflic ...

wing of the NLF formed a presidential committee of five people: Salim Rubaya Ali, who became president, Muhammad Saleh Al-Awlaki, Ali Antar, Abdel Fattah Ismail, and Muhammad Ali Haitham, who became prime minister. They gained power in an event known as the " Corrective Move". This radical wing reorganised the country into the People's Democratic Republic of Yemen (PDRY) on 30 November 1970. Subsequently, all political parties were amalgamated into the National Liberation Front, renamed the Yemeni Socialist Party, which became the only legal party. This group took an extreme leftist line and declared its support for the Palestinians and the Dhofar Revolution. West Germany severed its relationship with the state due to its recognition of East Germany. The United States also severed its relationship in October 1969. The new powers issued a new constitution, nationalized foreign banks and insurance companies, and changed the name of the state to The People's Democratic Republic of Yemen in line with the Marxist-Leninist approach they followed. A centrally planned economy was established. The People's Democratic Republic of Yemen established close ties with the Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

, the German Democratic Republic

East Germany, officially known as the German Democratic Republic (GDR), was a country in Central Europe from Foundation of East Germany, its formation on 7 October 1949 until German reunification, its reunification with West Germany (FRG) on ...

, Cuba

Cuba, officially the Republic of Cuba, is an island country, comprising the island of Cuba (largest island), Isla de la Juventud, and List of islands of Cuba, 4,195 islands, islets and cays surrounding the main island. It is located where the ...

, and the Palestinian Liberation Organization. East Germany

East Germany, officially known as the German Democratic Republic (GDR), was a country in Central Europe from Foundation of East Germany, its formation on 7 October 1949 until German reunification, its reunification with West Germany (FRG) on ...

's constitution of 1968 even served as a kind of blueprint for the PDRY's first constitution.

The new government embarked on a programme of nationalisation, introduced central planning, put limits on housing ownership and rent, and implemented land reforms. By 1973, the GDP of South Yemen increased by 25 percent. Despite the conservative environment and resistance, women became legally equal to men,

The new government embarked on a programme of nationalisation, introduced central planning, put limits on housing ownership and rent, and implemented land reforms. By 1973, the GDP of South Yemen increased by 25 percent. Despite the conservative environment and resistance, women became legally equal to men, polygamy

Polygamy (from Late Greek , "state of marriage to many spouses") is the practice of marriage, marrying multiple spouses. When a man is married to more than one wife at the same time, it is called polygyny. When a woman is married to more tha ...

, child marriage

Child marriage is a practice involving a marriage or domestic partnership, formal or informal, that includes an individual under 18 and an adult or other child.*

*

*

*

Research has found that child marriages have many long-term negative co ...

and arranged marriage were all banned by law and equal rights in divorce were sanctioned; all of supported and protected by the state General Union of Yemeni Women. The Republic also secularised education and sharia law

Sharia, Sharī'ah, Shari'a, or Shariah () is a body of religious law that forms a part of the Islamic tradition based on scriptures of Islam, particularly the Qur'an and hadith. In Islamic terminology ''sharīʿah'' refers to immutable, inta ...

was replaced by a state legal code. Slavery in Yemen, which had been abolished in North Yemen by the 1962 revolution, was now abolished also in South Yemen.

The major communist powers assisted in the building of the PDRY's armed forces. Strong support from Moscow resulted in Soviet naval forces gaining access to naval facilities in South Yemen. The most significant among them, a Soviet naval and air base on the island of Socotra for operations in the Indian Ocean.

1986 Civil War

On 13 January 1986, a violent struggle began in

On 13 January 1986, a violent struggle began in Aden

Aden () is a port city located in Yemen in the southern part of the Arabian peninsula, on the north coast of the Gulf of Aden, positioned near the eastern approach to the Red Sea. It is situated approximately 170 km (110 mi) east of ...

between Ali Nasir's supporters and supporters of the returned Ismail, who wanted power back. This conflict, known as the South Yemen Civil War

The South Yemeni crisis, colloquially referred to in Yemen as the events of '86, was a failed coup d'etat and brief civil war which took place on January 13, 1986, in South Yemen. The civil war developed as a result of ideological differences, ...

, lasted for more than a month and resulted in thousands of casualties, Ali Nasir's ouster, and Ismail's disappearance and presumed death. Some 60,000 people, including the deposed Ali Nasir, fled to the YAR. Ali Salim al-Beidh, an ally of Ismail who had succeeded in escaping the attack on pro-Ismail members of the Politburo

A politburo () or political bureau is the highest organ of the central committee in communist parties. The term is also sometimes used to refer to similar organs in socialist and Islamist parties, such as the UK Labour Party's NEC or the Poli ...

, then became General Secretary of the Yemeni Socialist Party.

Unification

Against the background of the ''perestroika

''Perestroika'' ( ; rus, перестройка, r=perestrojka, p=pʲɪrʲɪˈstrojkə, a=ru-perestroika.ogg, links=no) was a political reform movement within the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) during the late 1980s, widely associ ...

'' in the USSR

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

, the main backer of the PDRY, political reforms were started in the late 1980s. Political prisoners were released, political parties were formed, and the system of justice was reckoned to be more equitable than in the North. In May 1988, the YAR and PDRY governments came to an understanding that considerably reduced tensions, including agreement to renew discussions concerning unification, to establish a joint oil exploration area along their undefined border, to demilitarise the border, and to allow Yemenis unrestricted border passage based on only a national identification card. In November 1989, after returning from the Soviet–Afghan War

The Soviet–Afghan War took place in the Democratic Republic of Afghanistan from December 1979 to February 1989. Marking the beginning of the 46-year-long Afghan conflict, it saw the Soviet Union and the Armed Forces of the Democratic Republic o ...

, Osama bin Laden

Osama bin Laden (10 March 19572 May 2011) was a militant leader who was the founder and first general emir of al-Qaeda. Ideologically a pan-Islamist, Bin Laden participated in the Afghan ''mujahideen'' against the Soviet Union, and support ...

offered to send the newly formed al-Qaeda

, image = Flag of Jihad.svg

, caption = Jihadist flag, Flag used by various al-Qaeda factions

, founder = Osama bin Laden{{Assassinated, Killing of Osama bin Laden

, leaders = {{Plainlist,

* Osama bin Lad ...

to overthrow the South Yemeni government on behalf of Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia, officially the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA), is a country in West Asia. Located in the centre of the Middle East, it covers the bulk of the Arabian Peninsula and has a land area of about , making it the List of Asian countries ...

, but Prince Turki bin Faisal found the plan reckless and declined. In 1990, the parties reached a full agreement on joint governing of Yemen, and the countries were effectively merged as Yemen

Yemen, officially the Republic of Yemen, is a country in West Asia. Located in South Arabia, southern Arabia, it borders Saudi Arabia to Saudi Arabia–Yemen border, the north, Oman to Oman–Yemen border, the northeast, the south-eastern part ...

.

Government and politics

South Yemen developed as a Marxist–Leninist, mostly secular society ruled first by the National Front, which later transformed into the ruling Yemeni Socialist Party.

South Yemen developed as a Marxist–Leninist, mostly secular society ruled first by the National Front, which later transformed into the ruling Yemeni Socialist Party.

Government

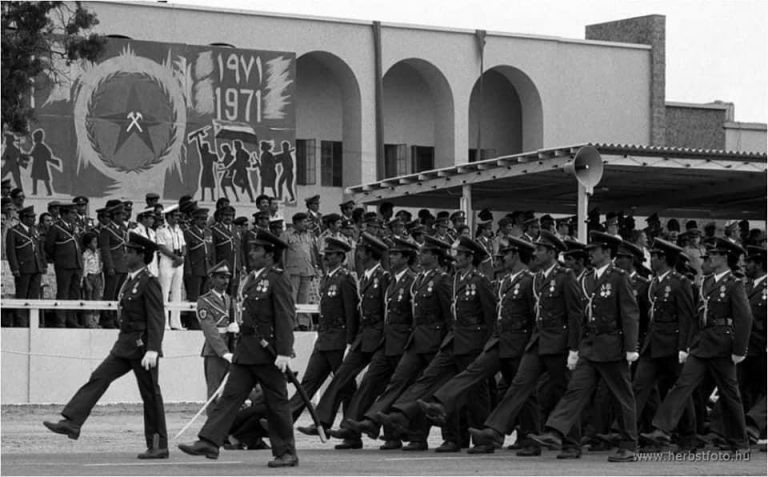

The legislative body, the Supreme People's Council, was elected by the people for five years. The Council was appointed by the General Command of the National Liberation Front in 1971. The collective head of state, also known as the Presidium of the Supreme People's Council, was elected by the Supreme People's Council for five years as well. The sole ruling political party was the Yemen Socialist Party. In 1978, the Election Law No. 18 introduced significant democratic reforms, guaranteeing universal, equal, secret, and direct elections for all citizens aged 18 or over. The law explicitly affirmed women's right to vote. Candidates could run as either members of the Yemen Socialist Party or as independents, and had to be at least 24 years old. The executive body was known as theCouncil of Ministers

Council of Ministers is a traditional name given to the supreme Executive (government), executive organ in some governments. It is usually equivalent to the term Cabinet (government), cabinet. The term Council of State is a similar name that also m ...

, and was formed by the Supreme People's Council. Local representative bodies were the people's councils, and their decisions were taken into account when the members of the Supreme People's Council were governing. Local executive bodies were the executive bureaus of the people's councils.

The highest court was the Supreme Court of South Yemen; other courts in the country included courts of appeal and the provincial courts, and the courts of first instance were known as the district courts or magistrate courts. In Aden, there was a structured judicial system with a supreme court

In most legal jurisdictions, a supreme court, also known as a court of last resort, apex court, high (or final) court of appeal, and court of final appeal, is the highest court within the hierarchy of courts. Broadly speaking, the decisions of ...

.

Foreign relations

The only avowedly Marxist–Leninist nation in the Middle East, South Yemen received significant

The only avowedly Marxist–Leninist nation in the Middle East, South Yemen received significant foreign aid

In international relations, aid (also known as international aid, overseas aid, foreign aid, economic aid or foreign assistance) is – from the perspective of governments – a voluntary transfer of resources from one country to another. The ...

and other assistance from the USSR

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

and East Germany

East Germany, officially known as the German Democratic Republic (GDR), was a country in Central Europe from Foundation of East Germany, its formation on 7 October 1949 until German reunification, its reunification with West Germany (FRG) on ...

, which stationed several hundred officers of the Stasi in the country to train the nation's secret police

image:Putin-Stasi-Ausweis.png, 300px, Vladimir Putin's secret police identity card, issued by the East German Stasi while he was working as a Soviet KGB liaison officer from 1985 to 1989. Both organizations used similar forms of repression.

Secre ...

and establish another arms trafficking route to Palestine

Palestine, officially the State of Palestine, is a country in West Asia. Recognized by International recognition of Palestine, 147 of the UN's 193 member states, it encompasses the Israeli-occupied West Bank, including East Jerusalem, and th ...

. The East Germans did not leave until 1990, when the Yemeni government declined to pay their salaries which had been terminated with the dissolution of the Stasi during German reunification

German reunification () was the process of re-establishing Germany as a single sovereign state, which began on 9 November 1989 and culminated on 3 October 1990 with the dissolution of the East Germany, German Democratic Republic and the int ...

. By the mid-1980s, the Soviet Union, under Mikhail Gorbachev

Mikhail Sergeyevich Gorbachev (2 March 1931 – 30 August 2022) was a Soviet and Russian politician who served as the last leader of the Soviet Union from 1985 to dissolution of the Soviet Union, the country's dissolution in 1991. He served a ...

, had largely distanced itself from South Yemen.

South Yemen often had an outward foreign policy approach, guided by its state ideology of scientific socialism. This ideological commitment led to its support for ideologically consistent movements within its region. South Yemen would supply the Popular Front for the Liberation of the Occupied Arabian Gulf (PFLOAG), supplying the group with bases in its territory, and logistical and military support for the group, alongside facilitating Soviet aid to PFLOAG. When the PFLOAG began to falter against the Omani government, South Yemen ramped up its support for the group, eventually providing them with Artillery support against the Omani government in 1975, almost dragging the two into conflict. South Yemen also supported the Derg in Ethiopia, once more with the rationale of supporting the growth of a Marxist-Leninist bloc in the

South Yemen often had an outward foreign policy approach, guided by its state ideology of scientific socialism. This ideological commitment led to its support for ideologically consistent movements within its region. South Yemen would supply the Popular Front for the Liberation of the Occupied Arabian Gulf (PFLOAG), supplying the group with bases in its territory, and logistical and military support for the group, alongside facilitating Soviet aid to PFLOAG. When the PFLOAG began to falter against the Omani government, South Yemen ramped up its support for the group, eventually providing them with Artillery support against the Omani government in 1975, almost dragging the two into conflict. South Yemen also supported the Derg in Ethiopia, once more with the rationale of supporting the growth of a Marxist-Leninist bloc in the Horn of Africa

The Horn of Africa (HoA), also known as the Somali Peninsula, is a large peninsula and geopolitical region in East Africa.Robert Stock, ''Africa South of the Sahara, Second Edition: A Geographical Interpretation'', (The Guilford Press; 2004), ...

. However, this faltered after Somalia re-aligned with the West in the Ogaden War

The Ogaden War, also known as the Ethio-Somali War (, ), was a military conflict between Somali Democratic Republic, Somalia and derg, Ethiopia fought from July 1977 to March 1978 over control of the sovereignty of the Ogaden region. Somalia ...

, leading South Yemen to solely supply the Derg, in line with the Soviet Union and Cuba

Cuba, officially the Republic of Cuba, is an island country, comprising the island of Cuba (largest island), Isla de la Juventud, and List of islands of Cuba, 4,195 islands, islets and cays surrounding the main island. It is located where the ...

. This put South Yemen at odds with most of the Arab World.

Relations between South Yemen and several nearby states were poor. Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia, officially the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA), is a country in West Asia. Located in the centre of the Middle East, it covers the bulk of the Arabian Peninsula and has a land area of about , making it the List of Asian countries ...

only established diplomatic relations in 1976, initially hosting pro-British exiles and supporting armed clashes in the border regions of South Yemen. Relations with Oman declined through the 1970s as the South Yemeni government supported the insurgent Marxist Popular Front for the Liberation of Oman (PFLO). Relations with Ba'athist Iraq

Ba'athist Iraq, officially the Iraqi Republic (1968–1992) and later the Republic of Iraq (1992–2003), was the Iraqi state between 1968 and 2003 under the one-party rule of the Arab Socialist Ba'ath Party – Iraq Region, Iraqi regional bra ...

were also low, as South Yemen offered asylum to several Iraqi communists.

The United States listed South Yemen as a “state sponsor of terrorism” between 1979 and the Yemeni reunification. Diplomatic relations with the United States had been broken on 24 October 1969 because of disagreements with US policy in the Middle East. They were not restored until shortly before reunification.

Relations with North Yemen

Unlike the early decades of other partitioned states such asEast Germany

East Germany, officially known as the German Democratic Republic (GDR), was a country in Central Europe from Foundation of East Germany, its formation on 7 October 1949 until German reunification, its reunification with West Germany (FRG) on ...

and West Germany

West Germany was the common English name for the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG) from its formation on 23 May 1949 until German reunification, its reunification with East Germany on 3 October 1990. It is sometimes known as the Bonn Republi ...

, North Korea

North Korea, officially the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK), is a country in East Asia. It constitutes the northern half of the Korea, Korean Peninsula and borders China and Russia to the north at the Yalu River, Yalu (Amnok) an ...

and South Korea

South Korea, officially the Republic of Korea (ROK), is a country in East Asia. It constitutes the southern half of the Korea, Korean Peninsula and borders North Korea along the Korean Demilitarized Zone, with the Yellow Sea to the west and t ...

, or North Vietnam

North Vietnam, officially the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV; ; VNDCCH), was a country in Southeast Asia from 1945 to 1976, with sovereignty fully recognized in 1954 Geneva Conference, 1954. A member of the communist Eastern Bloc, it o ...

and South Vietnam

South Vietnam, officially the Republic of Vietnam (RVN; , VNCH), was a country in Southeast Asia that existed from 1955 to 1975. It first garnered Diplomatic recognition, international recognition in 1949 as the State of Vietnam within the ...

, all of which faced tense relations or sometimes total war

Total war is a type of warfare that includes any and all (including civilian-associated) resources and infrastructure as legitimate military targets, mobilises all of the resources of society to fight the war, and gives priority to warfare ov ...

s, the relations between the Yemen Arab Republic (North Yemen) and the People's Democratic Republic of Yemen (South Yemen) remained relatively friendly throughout most of their existence, although conflicts did arise. Fighting broke out in 1972, and the short-lived conflict was resolved with negotiations, where it was declared unification would eventually occur.

However, these plans were put on hold in 1979, as the PDRY funded Red rebels in the YAR, and the war was only prevented by an Arab League

The Arab League (, ' ), officially the League of Arab States (, '), is a regional organization in the Arab world. The Arab League was formed in Cairo on 22 March 1945, initially with seven members: Kingdom of Egypt, Egypt, Kingdom of Iraq, ...

intervention. The goal of unity was reaffirmed by the northern and southern heads of state during a summit meeting in Kuwait

Kuwait, officially the State of Kuwait, is a country in West Asia and the geopolitical region known as the Middle East. It is situated in the northern edge of the Arabian Peninsula at the head of the Persian Gulf, bordering Iraq to Iraq–Kuwait ...

in March 1979.

In 1980, PDRY president Abdul Fattah Ismail

Abdul Fattah Ismail Ali Al-Jawfi (; 28 July 1939 – 13 January 1986) was a Yemeni Marxist politician and revolutionary who was the ''de facto'' leader of South Yemen from 1978 to 1980 after the overthrow of President Salim Rubaya Ali. He served ...

resigned and went into exile in Moscow, having lost the confidence of his sponsors in the USSR

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

. His successor, Ali Nasir Muhammad, took a less interventionist stance toward both North Yemen and neighbouring Oman

Oman, officially the Sultanate of Oman, is a country located on the southeastern coast of the Arabian Peninsula in West Asia and the Middle East. It shares land borders with Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and Yemen. Oman’s coastline ...

.

Administrative divisions

Following independence, South Yemen was divided into sixgovernorate

A governorate or governate is an administrative division headed by a governor. As English-speaking nations tend to call regions administered by governors either states or provinces, the term ''governorate'' is typically used to calque divisions ...

s (Arabic: ), with roughly natural boundaries. From 1967 to 1978, each was given a name by numeral. The state changed this practice in the mid-1980s but gave the governorates geographical or historical names and ensured that their borders did not coincide with tribal allegiances. Today, this legacy contributes to misunderstanding and confusion when discussing political issues and allegiances in Yemen. The islands of Kamaran (until 1972, when North Yemen seized it), Perim, Socotra

Socotra, locally known as Saqatri, is a Yemeni island in the Indian Ocean. Situated between the Guardafui Channel and the Arabian Sea, it lies near major shipping routes. Socotra is the largest of the six islands in the Socotra archipelago as ...

, Abd-el-Kuri, Samha (inhabited), Darsah and others uninhabited from the Socotra archipelago were districts () of the First/Aden Governorate being under the Prime Minister's supervision.

Geography

Located at the southwestern corner of the Arabian Peninsula, South Yemen occupied a wedge-shaped territory that tapered toward the Bab al-Mandab strait, the maritime chokepoint between theRed Sea

The Red Sea is a sea inlet of the Indian Ocean, lying between Africa and Asia. Its connection to the ocean is in the south, through the Bab-el-Mandeb Strait and the Gulf of Aden. To its north lie the Sinai Peninsula, the Gulf of Aqaba, and th ...

and the Indian Ocean

The Indian Ocean is the third-largest of the world's five oceanic divisions, covering or approximately 20% of the water area of Earth#Surface, Earth's surface. It is bounded by Asia to the north, Africa to the west and Australia (continent), ...

. The country's territorial claims included the volcanic island of Perim within the strait and the larger island of Socotra

Socotra, locally known as Saqatri, is a Yemeni island in the Indian Ocean. Situated between the Guardafui Channel and the Arabian Sea, it lies near major shipping routes. Socotra is the largest of the six islands in the Socotra archipelago as ...

, a semi-desert landmass situated in the Arabian Sea. The total area of South Yemen was estimated at approximately 208,106 square kilometers (80,345 square miles), although this figure remains approximate due to the lack of fully demarcated borders with North Yemen and Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia, officially the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA), is a country in West Asia. Located in the centre of the Middle East, it covers the bulk of the Arabian Peninsula and has a land area of about , making it the List of Asian countries ...

, particularly in the southern expanse of the Rub' al Khali.

Topography and geology

The lands of South Yemen are rugged and barren, a fact that played a role in the social, cultural, and economic development of the south, unlike the northern regions of Yemen. Their population in 1967 did not exceed two million people, while northern Yemen exceeded six million. Most of the population of the south was concentrated in the western regions of Lahij and its environs, and these alone constituted more than 60% of the population; 10% were bedouins. South Yemen's landscape was shaped by a prominent mountain chain that mirrors the Red Sea coast of the Arabian Peninsula, extending from the Gulf of Aqaba southward to the Bab al-Mandab before curving northeast along theGulf of Aden

The Gulf of Aden (; ) is a deepwater gulf of the Indian Ocean between Yemen to the north, the Arabian Sea to the east, Djibouti to the west, and the Guardafui Channel, the Socotra Archipelago, Puntland in Somalia and Somaliland to the south. ...

and the Arabian Sea

The Arabian Sea () is a region of sea in the northern Indian Ocean, bounded on the west by the Arabian Peninsula, Gulf of Aden and Guardafui Channel, on the northwest by Gulf of Oman and Iran, on the north by Pakistan, on the east by India, and ...

toward Ras Musandam at the entrance to the Persian Gulf

The Persian Gulf, sometimes called the Arabian Gulf, is a Mediterranean seas, mediterranean sea in West Asia. The body of water is an extension of the Arabian Sea and the larger Indian Ocean located between Iran and the Arabian Peninsula.Un ...

. This terrain includes a coastal plain of Tihamah, varying in width from a few kilometers to over sixty, which gradually ascends to foothills and then sharply rises to mountain ranges where peaks exceed 2,000 meters.