Norwegian language on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Norwegian ( ) is a North Germanic language from the Indo-European language family spoken mainly in

Like most of the languages in Europe, Norwegian derives from Proto-Indo-European. As early Indo-Europeans spread across Europe, they became isolated from each other and new languages developed. In northwest Europe, the

Like most of the languages in Europe, Norwegian derives from Proto-Indo-European. As early Indo-Europeans spread across Europe, they became isolated from each other and new languages developed. In northwest Europe, the

There is also predicative agreement of adjectives in all dialects of Norwegian and in the written languages, unlike related languages like German and Dutch. This feature of predicative agreement is shared among the Scandinavian languages. Predicative adjectives do not inflect for definiteness unlike the attributive adjectives.

This means that nouns will have to agree with the adjective when there is a copula verb involved, like in Bokmål: ('to be'), ('become'), ('looks like'), ('feels like') etc.

in English

* Arne Torp, Lars S. Vikør (1993), ''Hovuddrag i norsk språkhistorie (3.utgåve)'', Gyldendal Norsk Forlag AS 2003 * Lars S. Vikør (2015), ''Norwegian: Bokmål vs. Nynorsk''

on Språkrådet's website

Ordboka

– Online dictionary search, both Bokmål and Nynorsk. *

Norwegian as a Normal Language

in English, at ''Språkrådet''

Ordbøker og nettressurser

– a collection of dictionaries and online resources (in Norwegian) from ''Språkrådet'' {{DEFAULTSORT:Norwegian Language Norwegian language Fusional languages Languages of Norway North Germanic languages Scandinavian culture Stress-timed languages Subject–verb–object languages Tonal languages Verb-second languages West Scandinavian languages

Norway

Norway, officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic countries, Nordic country located on the Scandinavian Peninsula in Northern Europe. The remote Arctic island of Jan Mayen and the archipelago of Svalbard also form part of the Kingdom of ...

, where it is an official language. Along with Swedish and Danish, Norwegian forms a dialect continuum

A dialect continuum or dialect chain is a series of Variety (linguistics), language varieties spoken across some geographical area such that neighboring varieties are Mutual intelligibility, mutually intelligible, but the differences accumulat ...

of more or less mutually intelligible local and regional varieties; some Norwegian and Swedish dialects, in particular, are very close. These Scandinavia

Scandinavia is a subregion#Europe, subregion of northern Europe, with strong historical, cultural, and linguistic ties between its constituent peoples. ''Scandinavia'' most commonly refers to Denmark, Norway, and Sweden. It can sometimes also ...

n languages, together with Faroese and Icelandic as well as some extinct languages, constitute the North Germanic languages. Faroese and Icelandic are not mutually intelligible with Norwegian in their spoken form because continental Scandinavian has diverged from them. While the two Germanic languages

The Germanic languages are a branch of the Indo-European languages, Indo-European language family spoken natively by a population of about 515 million people mainly in Europe, North America, Oceania, and Southern Africa. The most widely spoke ...

with the greatest numbers of speakers, English and German, have close similarities with Norwegian, neither is mutually intelligible with it. Norwegian is a descendant of Old Norse

Old Norse, also referred to as Old Nordic or Old Scandinavian, was a stage of development of North Germanic languages, North Germanic dialects before their final divergence into separate Nordic languages. Old Norse was spoken by inhabitants ...

, the common language of the Germanic peoples

The Germanic peoples were tribal groups who lived in Northern Europe in Classical antiquity and the Early Middle Ages. In modern scholarship, they typically include not only the Roman-era ''Germani'' who lived in both ''Germania'' and parts of ...

living in Scandinavia during the Viking Age

The Viking Age (about ) was the period during the Middle Ages when Norsemen known as Vikings undertook large-scale raiding, colonising, conquest, and trading throughout Europe and reached North America. The Viking Age applies not only to their ...

.

Today there are two official forms of ''written'' Norwegian, (Riksmål) and (Landsmål), each with its own variants. developed from the Dano-Norwegian language that replaced Middle Norwegian as the elite language after the union of Denmark–Norway in the 16th and 17th centuries and then evolved in Norway, while was developed based upon a collective of spoken Norwegian dialects. Norwegian is one of the two official languages in Norway, along with Sámi, a group of Finno-Ugric languages spoken by less than one percent of the population. Norwegian is one of the working languages of the Nordic Council. Under the Nordic Language Convention, citizens of the Nordic countries

The Nordic countries (also known as the Nordics or ''Norden''; ) are a geographical and cultural region in Northern Europe, as well as the Arctic Ocean, Arctic and Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic oceans. It includes the sovereign states of Denm ...

who speak Norwegian have the opportunity to use it when interacting with official bodies in other Nordic countries without being liable for any interpretation or translation costs.

History

Origins

Like most of the languages in Europe, Norwegian derives from Proto-Indo-European. As early Indo-Europeans spread across Europe, they became isolated from each other and new languages developed. In northwest Europe, the

Like most of the languages in Europe, Norwegian derives from Proto-Indo-European. As early Indo-Europeans spread across Europe, they became isolated from each other and new languages developed. In northwest Europe, the Germanic languages

The Germanic languages are a branch of the Indo-European languages, Indo-European language family spoken natively by a population of about 515 million people mainly in Europe, North America, Oceania, and Southern Africa. The most widely spoke ...

evolved, further branching off into the North Germanic languages, of which Norwegian is one.

Proto-Norse is thought to have evolved as a northern dialect of Proto-Germanic

Proto-Germanic (abbreviated PGmc; also called Common Germanic) is the linguistic reconstruction, reconstructed proto-language of the Germanic languages, Germanic branch of the Indo-European languages.

Proto-Germanic eventually developed from ...

during the first centuries AD in what is today Southern Sweden. It is the earliest stage of a characteristically North Germanic language, and the language attested in the Elder Futhark inscriptions, the oldest form of the runic alphabets. A number of inscriptions are memorials to the dead, while others are magical in content. The oldest are carved on loose objects, while later ones are chiseled in runestones. They are the oldest written record of any Germanic language.

Around 800 AD, the script was simplified to the Younger Futhark, and inscriptions became more abundant. At the same time, the beginning of the Viking Age

The Viking Age (about ) was the period during the Middle Ages when Norsemen known as Vikings undertook large-scale raiding, colonising, conquest, and trading throughout Europe and reached North America. The Viking Age applies not only to their ...

led to the spread of Old Norse

Old Norse, also referred to as Old Nordic or Old Scandinavian, was a stage of development of North Germanic languages, North Germanic dialects before their final divergence into separate Nordic languages. Old Norse was spoken by inhabitants ...

to Iceland

Iceland is a Nordic countries, Nordic island country between the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic and Arctic Oceans, on the Mid-Atlantic Ridge between North America and Europe. It is culturally and politically linked with Europe and is the regi ...

, Greenland, and the Faroe Islands

The Faroe Islands ( ) (alt. the Faroes) are an archipelago in the North Atlantic Ocean and an autonomous territory of the Danish Realm, Kingdom of Denmark. Located between Iceland, Norway, and the United Kingdom, the islands have a populat ...

. Viking colonies also existed in parts of the British Isles, France (Normandy

Normandy (; or ) is a geographical and cultural region in northwestern Europe, roughly coextensive with the historical Duchy of Normandy.

Normandy comprises Normandy (administrative region), mainland Normandy (a part of France) and insular N ...

), North America, and Kievan Rus. In all of these places except Iceland and the Faroes, Old Norse speakers went extinct or were absorbed into the local population.

The Roman alphabet

Around 1030, Christianity came toScandinavia

Scandinavia is a subregion#Europe, subregion of northern Europe, with strong historical, cultural, and linguistic ties between its constituent peoples. ''Scandinavia'' most commonly refers to Denmark, Norway, and Sweden. It can sometimes also ...

, bringing with it an influx of Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

borrowings and the Roman alphabet. These new words were related to church practices and ceremonies, although many other loanwords related to general culture also entered the language.

The Scandinavian languages at this time are not considered to be separate languages, although there were minor differences among what are customarily called Old Icelandic, Old Norwegian

Old Norwegian ( and ), also called Norwegian Norse, is an early form of the Norwegian language that was spoken between the 11th and 14th century; it is a transitional stage between Old West Norse and Middle Norwegian.

Its distinction from O ...

, Old Gutnish, Old Danish, and Old Swedish.

11th━15th century

Low German influence

The economic and political dominance of the Hanseatic League between 1250 and 1450 in the main Scandinavian cities brought large Middle Low German–speaking populations to Norway. The influence of their language on Scandinavian is comparable with that of French on English after theNorman conquest

The Norman Conquest (or the Conquest) was the 11th-century invasion and occupation of England by an army made up of thousands of Normans, Norman, French people, French, Flemish people, Flemish, and Bretons, Breton troops, all led by the Du ...

.

Decline of written Norwegian

In the late Middle Ages, dialects began to develop in Scandinavia because the population was rural and little travel occurred. When the Reformation came from Germany, Martin Luther's High German translation of the Bible was quickly translated into Swedish, Danish, and Icelandic. Norway entered a union with Denmark in 1397 and Danish, over time, replaced Middle Norwegian as the language of the elite, the church, literature, and the law. When the union with Denmark ended in 1814, the Dano-Norwegian ''koiné'' had become the mother tongue of around 1% of the population.Danish to Norwegian standardisation

From the 1840s, some writers experimented with a Norwegianised form of written Danish. Knud Knudsen proposed to change spelling and inflection in accordance with the Dano-Norwegian ''koiné'', known as "cultivated everyday speech." A small adjustment in this direction was implemented in the first official reform of the Danish language in Norway in 1862 and more extensively after his death in two official reforms in 1907 and 1917. Meanwhile, a nationalistic movement strove for the development of a new written Norwegian. Ivar Aasen, a botanist and self-taught linguist, began his work to create a new Norwegian language at the age of 22. He traveled around the country collecting words and examples of grammar from the dialects and comparing the dialects among the different regions. He examined the development of Icelandic, which had largely escaped the influences under which Norwegian had come. He called his work, which was published in several books from 1848 to 1873, Landsmål, meaning 'national language'. The name ''Landsmål'' is sometimes interpreted as 'rural language' or 'country language', but this was clearly not Aasen's intended meaning. The name of the Danish language in Norway was a topic of hot dispute throughout the 19th century. Its proponents claimed that it was a language common to Norway and Denmark, and no more Danish than Norwegian. The proponents of Landsmål thought that the Danish character of the language should not be concealed. In 1899, Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson proposed the neutral name '' Riksmål'', meaning 'national language' like ''Landsmål'', and this was officially adopted along with the 1907 spelling reform. The name ''Riksmål'' is sometimes interpreted as 'state language', but this meaning is secondary at best. (Compare to Danish ''rigsmål'' from where the name was borrowed.) After the personal union with Sweden was dissolved in 1905, both languages were developed further and reached what is now considered their classic forms after a reform in 1917. Riksmål was, in 1929, officially renamed ''Bokmål'' (literally 'book language'), and Landsmål to ''Nynorsk'' (literally 'new Norwegian'). A proposition to substitute Danish-Norwegian () for ''Bokmål'' lost in parliament by a single vote. The name ''Nynorsk'', the linguistic term for modern Norwegian, was chosen to contrast with Danish and emphasise the historical connection to Old Norwegian. Today, this meaning is often lost, and it is commonly mistaken as a "new" Norwegian in contrast to the "real" Norwegian Bokmål. Bokmål and Nynorsk were made closer by a reform in 1938. This was a result of a state policy to merge Nynorsk and Bokmål into a single language, to be called ''Samnorsk''. A 1946 poll showed that this policy was supported by 79% of Norwegians at the time. However, opponents of the official policy still managed to create a massive protest movement against ''Samnorsk'' in the 1950s, fighting in particular the use of "radical" forms in Bokmål text books in schools. In the reform in 1959, the 1938 reform was partially reversed in Bokmål, but Nynorsk was changed further towards Bokmål. Since then Bokmål has reverted even further toward traditional Riksmål, while Nynorsk still adheres to the 1959 standard. Therefore, a small minority of Nynorsk enthusiasts use a more conservative standard called Høgnorsk. The Samnorsk policy had little influence after 1960, and was officially abandoned in 2002.Phonology

While the sound systems of Norwegian and Swedish are similar, considerable variation exists among the dialects.Consonants

The retroflex consonants only appear in East Norwegian dialects as a result of sandhi, combining with , , , , and . The realization of the rhotic depends on the dialect. In Eastern, Central, and Northern Norwegian dialects, it is a flap , whereas in Western and Southern Norway, and for some speakers also in Eastern Norway, it is uvular or . And in the dialects of North-Western Norway, it is realized as , much like the trilled of Spanish.Vowels

Accent

Norwegian is a pitch-accent language with two distinct pitch patterns, like Swedish. They are used to differentiate two-syllable words with otherwise identical pronunciation. For example, in many East Norwegian dialects, the word ('farmers') is pronounced using the simpler tone 1, while ('beans' or 'prayers') uses the more complex tone 2. Though spelling differences occasionally differentiate written words, in most cases the minimal pairs are written alike, since written Norwegian has no explicit accent marks. In most eastern low-tone dialects, accent 1 uses a low flat pitch in the first syllable, while accent 2 uses a high, sharply falling pitch in the first syllable and a low pitch in the beginning of the second syllable. In both accents, these pitch movements are followed by a rise of intonational nature (phrase accent)—the size (and presence) of which signals emphasis or focus, and corresponds in function to the normal accent in languages that lack lexical tone, such as English. That rise culminates in the final syllable of an accentual phrase, while the utterance-final fall common in most languages is either very small or absent. There are significant variations in pitch accent between dialects. Thus, in most of western and northern Norway (the so-called high-pitch dialects) accent 1 is falling, while accent 2 is rising in the first syllable and falling in the second syllable or somewhere around the syllable boundary. The pitch accents (as well as the peculiar phrase accent in the low-tone dialects) give the Norwegian language a "singing" quality that makes it easy to distinguish from other languages. Accent 1 generally occurs in words that were monosyllabic inOld Norse

Old Norse, also referred to as Old Nordic or Old Scandinavian, was a stage of development of North Germanic languages, North Germanic dialects before their final divergence into separate Nordic languages. Old Norse was spoken by inhabitants ...

, and accent 2 in words that were polysyllabic.

Written language

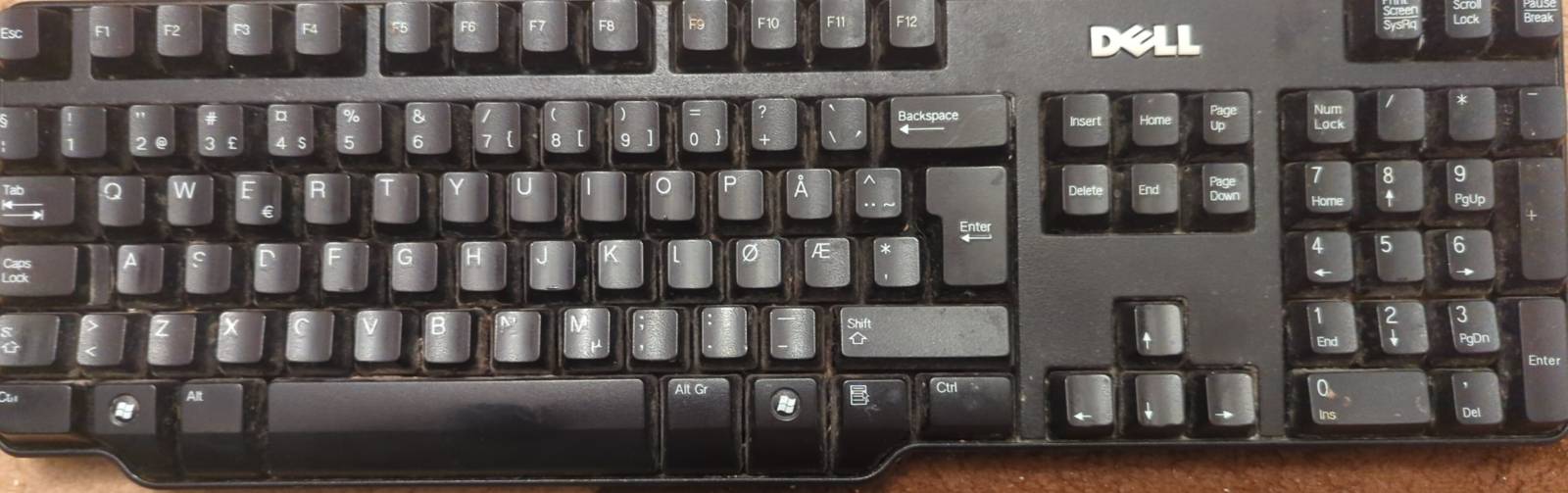

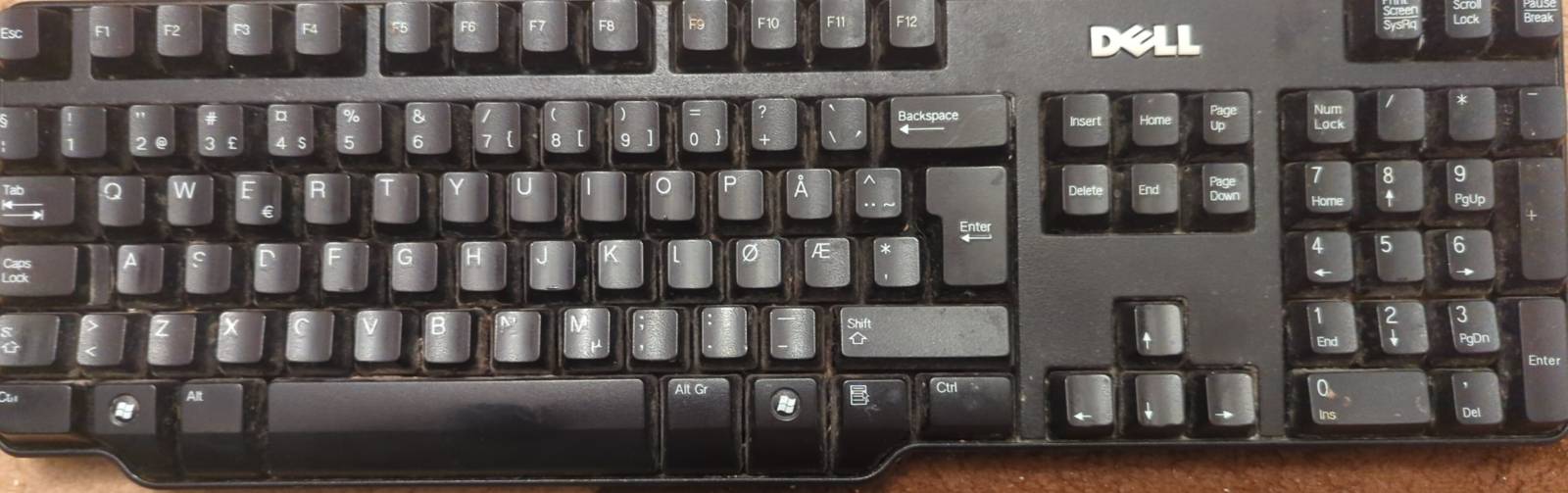

Alphabet

The Norwegian alphabet has 29 letters. The letters ''c'', ''q'', ''w'', ''x'' and ''z'' are only used in loanwords. As loanwords are assimilated into Norwegian, their spelling might change to reflect Norwegian pronunciation and the principles of Norwegian orthography, e.g. '' zebra'' in Norwegian is written . Due to historical reasons, some otherwise Norwegian family names are also written using these letters. Some letters may be modified by diacritics: ''é'', ''è'', ''ê'', ''ó'', ''ò'', and ''ô''. In Nynorsk, ''ì'' and ''ù'' and ''ỳ'' are occasionally seen as well. The diacritics are not compulsory, but may in a few cases distinguish between different meanings of the word, e.g.: ('for/to'), ('went'), ('furrow') and ('fodder'). Loanwords may be spelled with other diacritics, most notably ''ï, ü'', ''á'' and ''à''.Bokmål and Nynorsk

The two legally recognized forms of ''written'' Norwegian are '' Bokmål'' (literally 'book tongue') and ''Nynorsk

Nynorsk (; ) is one of the two official written standards of the Norwegian language, the other being Bokmål. From 12 May 1885, it became the state-sanctioned version of Ivar Aasen's standard Norwegian language (''Landsmål''), parallel to the Da ...

'' ('new Norwegian'), which are regulated by the Language Council of Norway (). Two other written forms without official status also exist. One, called '' Riksmål'' ('national language'), is today to a large extent the same language as Bokmål though somewhat closer to the Danish language. It is regulated by the unofficial Norwegian Academy, which translates the name as 'Standard Norwegian'. The other is '' Høgnorsk'' ('High Norwegian'), a more purist form of Nynorsk, which maintains the language in an original form as given by Ivar Aasen and rejects most of the reforms from the 20th century; this form has limited use.

Nynorsk and Bokmål provide standards for how to write Norwegian, but not for how to speak the language. No standard of spoken Norwegian is officially sanctioned, and most Norwegians speak their own dialects in all circumstances. Thus, unlike in many other countries, the use of any Norwegian dialect, whether it coincides with the written norms or not, is accepted as correct ''spoken'' Norwegian. However, in areas where East Norwegian dialects are used, a tendency exists to accept a de facto spoken standard for this particular regional dialect, Urban East Norwegian or Standard East Norwegian (), in which the vocabulary coincides with Bokmål. Outside Eastern Norway, this spoken variation is not used.

From the 16th to the 19th centuries, Danish was the standard written language of Norway. As a result, the development of modern written Norwegian has been subject to strong controversy related to nationalism, rural versus urban discourse, and Norway's literary history. Historically, Bokmål is a Norwegianised variety of Danish, while Nynorsk is a language form based on Norwegian dialects and puristic opposition to Danish. The now-abandoned official policy to merge Bokmål and Nynorsk into one common language called ''Samnorsk'' through a series of spelling reforms has created a wide spectrum of varieties of both Bokmål and Nynorsk. The unofficial form known as ''Riksmål'' is considered more conservative than Bokmål and is far closer to Danish while the unofficial ''Høgnorsk'' is more conservative than Nynorsk and is far closer to Faroese, Icelandic and Old Norse

Old Norse, also referred to as Old Nordic or Old Scandinavian, was a stage of development of North Germanic languages, North Germanic dialects before their final divergence into separate Nordic languages. Old Norse was spoken by inhabitants ...

.

Norwegians are educated in both Bokmål and Nynorsk. Each student gets assigned a native form based on which school they go to, whence the other form (known as ) will be a mandatory school subject from elementary school through high school. For instance, a Norwegian whose main language form is Bokmål will study Nynorsk as a mandatory subject throughout both elementary and high school. A 2005 poll indicates that 86.3% use primarily Bokmål as their daily written language, 5.5% use both Bokmål and Nynorsk, and 7.5% use primarily Nynorsk. Broadly speaking, Nynorsk writing is widespread in western Norway, though not in major urban areas, and also in the upper parts of mountain valleys in the southern and eastern parts of Norway. Examples are Setesdal, the western part of Telemark county () and several municipalities in Hallingdal, Valdres, and Gudbrandsdalen. It is little used elsewhere, but 30–40 years ago, it also had strongholds in many rural parts of Trøndelag (mid-Norway) and the southern part of northern Norway ( Nordland county). Today, Nynorsk is the official language of not only four of the nineteen Norwegian counties but also various municipalities in five other counties. NRK, the Norwegian broadcasting corporation, broadcasts in both Bokmål and Nynorsk, and all governmental agencies are required to support both written languages. Bokmål is used in 92% of all written publications, and Nynorsk in 8% (2000).

Like some other European countries, Norway has an official "advisory board" Språkrådet (Norwegian Language Council) that determines, after approval from the Ministry of Culture, official spelling, grammar, and vocabulary for the Norwegian language. The board's work has been subject to considerable controversy throughout the years.

Both Nynorsk and Bokmål have a great variety of optional forms. The Bokmål that uses the forms that are close to Riksmål is called ''moderate'' or ''conservative'', depending on one's viewpoint, while the Bokmål that uses the forms that are close to Nynorsk is called ''radical''. Nynorsk has forms that are close to the original Landsmål and forms that are close to Bokmål.

Riksmål

Opponents of the spelling reforms aimed at bringing Bokmål closer to Nynorsk have retained the name Riksmål and employ spelling and grammar that predate the Samnorsk movement. Riksmål and conservative versions of Bokmål have been the ''de facto'' standard written language of Norway for most of the 20th century, being used by large newspapers, encyclopedias, and a significant proportion of the population of the capital Oslo, surrounding areas, and other urban areas, as well as much of the literary tradition. Since the reforms of 1981 and 2003 (effective in 2005), the official Bokmål can be adapted to be almost identical with modern Riksmål. The differences between written Riksmål and Bokmål are comparable to American and British English differences. Riksmål is regulated by the Norwegian Academy, which determines acceptable spelling, grammar, and vocabulary.Høgnorsk

There is also an unofficial form of Nynorsk, called ''Høgnorsk'', discarding the post-1917 reforms, and thus close to Ivar Aasen's original Landsmål. It is supported by Ivar Aasen-sambandet, but has found no widespread use.Current usage

In 2010, 86.5% of the pupils in the primary and lower secondary schools in Norway receive education in Bokmål, while 13.0% receive education in Nynorsk. From the eighth grade onwards, pupils are required to learn both. Out of the 431 municipalities in Norway, 161 have declared that they wish to communicate with the central authorities in Bokmål, 116 (representing 12% of the population) in Nynorsk, while 156 are neutral. Of 4,549 state publications in 2000, 8% were in Nynorsk, and 92% in Bokmål. The large national newspapers (, and ''VG'') are published in Bokmål or Riksmål. Some major regional newspapers (including and '' Stavanger Aftenblad''), many political journals, and many local newspapers use both Bokmål and Nynorsk. A newer trend is to write in dialect for informal use. When writing an SMS, Facebook update, or fridge note, many people, especially young ones, write approximations of the way they talk rather than using Bokmål or Nynorsk.Dialects

There is general agreement that a wide range of differences makes it difficult to estimate the number of different Norwegian dialects. Variations in grammar, syntax, vocabulary, and pronunciation cut across geographical boundaries and can create a distinct dialect at the level of farm clusters. Dialects are in some cases so dissimilar as to be unintelligible to unfamiliar listeners. Many linguists note a trend toward regionalization of dialects that diminishes the differences at such local levels; there is, however, a renewed interest in preserving dialects.Grammar

Nouns

Norwegian nouns are inflected for number (singular/plural) and for definiteness (indefinite/definite). In a few dialects, definite nouns are also inflected for the dative case. Norwegian nouns belong to three noun classes (genders): masculine, feminine and neuter. All feminine nouns can optionally be inflected using masculine noun class morphology in Bokmål due to its Danish heritage. In comparison, the use of all three genders (including the feminine) is mandatory in Nynorsk. All Norwegian dialects have traditionally retained all the three grammatical genders fromOld Norse

Old Norse, also referred to as Old Nordic or Old Scandinavian, was a stage of development of North Germanic languages, North Germanic dialects before their final divergence into separate Nordic languages. Old Norse was spoken by inhabitants ...

to some extent. The only exceptions are the dialect of Bergen and a few upper class sociolects at the west end of Oslo that have completely lost the feminine gender.

According to Marit Westergaard, approximately 80% of nouns in Norwegian are masculine.

Norwegian and other Scandinavian languages use a suffix to indicate definiteness of a noun, unlike English which has a separate article, ''the'', to indicate the same.

In general, almost all nouns in Bokmål follow these patterns (like the words in the examples above):

In contrast, almost all nouns in Nynorsk follow these patterns (the noun gender system is more pronounced than in Bokmål):

There is in general no way to infer what grammatical gender a specific noun has, but there are some patterns of nouns where the gender can be inferred. For instance, all nouns ending in -''nad'' will be masculine in both Bokmål and Nynorsk (for instance the noun , which means 'job application'). Most nouns ending in -''ing'' will be feminine, like the noun ('expectation').

There are some common irregular nouns, many of which are irregular in both Bokmål and Nynorsk, like the following:

In Nynorsk, even though the irregular word is masculine, it is inflected like a feminine word in the plural. Another word with the same irregular inflection is ('son – sons').

In Nynorsk, nouns ending in -''ing'' typically have masculine plural inflections, like the word in the following table. But they are treated as feminine nouns in every other way.

Genitive of nouns

In general, thegenitive case

In grammar, the genitive case ( abbreviated ) is the grammatical case that marks a word, usually a noun, as modifying another word, also usually a noun—thus indicating an attributive relationship of one noun to the other noun. A genitive ca ...

has died out in modern Norwegian and there are only some remnants of it in certain expressions: ('to the mountains'), ('to the sea'). To show ownership, there is an enclitic -''s'' similar to English -''s''; ('Sondre's nice car', ''Sondre'' being a personal name). There are also reflexive possessive pronouns, , , , ; ('It is Sondre's'). In both Bokmål and modern Nynorsk, there is often a mix of both of these to mark possession, though it is more common in Nynorsk to use the reflexive pronouns; in Nynorsk use of the reflexive possessive pronouns is generally encouraged to avoid mixing the enclitic -''s'' with the historical grammatical case remnants of the language. The reflexive pronouns agree in gender and number with the noun.

The enclitic -''s'' in Norwegian evolved as a shorthand expression for the possessive pronouns , , and .

Adjectives

Norwegian adjectives, like those of Swedish and Danish, inflect for definiteness, gender, number and for comparison (affirmative/comparative/superlative). Inflection for definiteness follows two paradigms, called "weak" and "strong", a feature shared among theGermanic languages

The Germanic languages are a branch of the Indo-European languages, Indo-European language family spoken natively by a population of about 515 million people mainly in Europe, North America, Oceania, and Southern Africa. The most widely spoke ...

.

The following table summarizes the inflection of adjectives in Norwegian. The indefinite affirmative inflection can vary between adjectives, but in general the paradigm illustrated below is the most common.

Predicate adjectives follow only the indefinite inflection table. Unlike attributive adjectives, they are not inflected for definiteness.

In most dialects, some verb participles used as adjectives have a separate form in both definite and plural uses, and sometimes also in the masculine-feminine singular. In some Southwestern dialects, the definite adjective is also declined in gender and number with one form for feminine and plural, and one form for masculine and neuter.

= Definite inflection

= In Norwegian, a definite noun has a suffixed definite article (cf. above) compared to English which in general uses the separate word ''the'' to indicate the same. However, when a definite noun is preceded by an adjective, the adjective also gets a definite inflection, shown in the inflection table above. There is also another definite marker, , that has to agree in gender with the noun when the definite noun is accompanied by an adjective. It comes before the adjective and has the following forms Examples of definite affirmative inflection of adjectives (Bokmål): * ('The ''stolen'' car') * ('The ''pretty'' girl') * ('The ''green'' apple') * ('The ''stolen'' cars') If the adjective is dropped completely, the meaning of the preceding article before the noun changes, as shown in this example. Examples (Bokmål): * ('That car') * ('That girl') * ('That apple') * ('Those cars') Examples of definite comparative and superlative inflection of adjectives (Bokmål): * ('The ''greener'' apple') * ('The ''greenest'' apple') Definiteness is also signaled by using possessive pronouns or any uses of a noun in its genitive form in either Nynorsk or Bokmål: ('my green house'), ('my green car'), ('my receding gums'), ('the president's old house').= Indefinite inflection

= Examples (Bokmål): * ('A ''green'' car') * ('A ''pretty'' girl') * ('A ''green'' apple') * ('Many ''green'' cars') Examples of comparative and superlative inflections in Bokmål: ('a greener car'), ('greenest car').Verbs

Norwegian verbs are not conjugated for person or number, unlike English and most European languages, though a few Norwegian dialects do conjugate for number. Norwegian verbs are conjugated according to mainly three grammatical moods: indicative, imperative and subjunctive, though the subjunctive mood has largely fallen out of use and is mainly found in a few common frozen expressions. The imperative is formed by removing the last vowel of the infinitive verb form, just like in the other Scandinavian languages. Indicative verbs are conjugated for tense: present,past

The past is the set of all Spacetime#Definitions, events that occurred before a given point in time. The past is contrasted with and defined by the present and the future. The concept of the past is derived from the linear fashion in which human ...

, and future. The present and past tense also have a passive form for the infinitive.

There are four non-finite verb forms: infinitive, passive infinitive, and the two participles: perfective/past participle and imperfective/present participle.

The participles are verbal adjectives. The imperfective participle is not declined, whereas the perfect participle is declined for gender (though not in Bokmål) and number like strong, affirmative adjectives. The definite form of the participle is identical to the plural form.

As with other Germanic languages, Norwegian verbs can be divided into two conjugation classes; weak verbs and strong verbs.

Ergative verbs

There are ergative verbs in both Bokmål and Nynorsk, where there are two different conjugation patterns depending on if the verb takes an object or not. In Bokmål, there are only two different conjugations for the preterite tense for the strong verbs, while Nynorsk has different conjugations for all tenses, like Swedish and a majority of Norwegian dialects. Some weak verbs are also ergative and are differentiated for all tenses in both Bokmål and Nynorsk, like , both of which meaning 'to lie down', but does not take an object while requires an object. corresponds to the English verb 'lay', while corresponds to the English verb 'lie'. There are, however, many verbs that do not have a direct translation to English verbs.Pronouns

Norwegian personal pronouns are declined according to case: nominative and accusative. Like English, pronouns in Bokmål and Nynorsk are the only class that has case declension. Some of the dialects that have preserved the dative in nouns, also have a dative case instead of the accusative case in personal pronouns, while others have accusative in pronouns and dative in nouns, effectively giving these dialects three distinct cases. In the most comprehensive Norwegian grammar, Norsk referansegrammatikk, the categorization of personal pronouns by person, gender, and number is not regarded as inflection. Pronouns are a closed class in Norwegian. Since December 2017, the gender-neutral pronoun is present in the Norwegian Academy's dictionary ( NAOB). In June 2022, the Language Council of Norway ( Språkrådet) started including in both Bokmål and Nynorsk Norwegian standards. The words for 'mine', 'yours' etc. are dependent on the gender of the noun described. Like adjectives, they have to agree in gender with the noun. Bokmål has two sets of third-person pronouns. and refer to male and female individuals respectively; and refer to impersonal or inanimate nouns, of masculine/feminine or neutral gender respectively. In contrast, Nynorsk and most dialects use the same set of pronouns ('he'), ('she') and ('it') for both personal and impersonal references, like in German, Icelandic andOld Norse

Old Norse, also referred to as Old Nordic or Old Scandinavian, was a stage of development of North Germanic languages, North Germanic dialects before their final divergence into separate Nordic languages. Old Norse was spoken by inhabitants ...

. also has expletive and cataphoric uses like in the English examples ''it rains'' and ''it was known by everyone (that) he had travelled the world''.

Ordering of possessive pronouns

The ordering of possessive pronouns is somewhat freer than in Swedish or Danish. When there is no adjective, the most common word order is the one used in the examples in the table above, where the possessive comes after the noun, while the noun is in its definite form; ('my book'). If one wishes to emphasize the owner of the noun, the possessive pronoun will usually be placed first. In Bokmål, however, due to its Danish origins, one could choose to always write the possessive first: ('my car'), but this may sound very formal. Some dialects that have been very influenced by Danish also do this; some speakers in Bærum and the west of Oslo may always use this word order. When there is an adjective describing the noun, the possessive pronoun will always come first: ('my own car').Determiners

The closed class of Norwegian determiners are declined in gender and number in agreement with their argument. Not all determiners are inflected.Numerals

Particle classes

Norwegian has five closed classes without inflection, i.e. lexical categories with grammatical function and a finite number of members that may not be distinguished by morphological criteria. These are interjections, conjunctions, subjunctions, prepositions, and adverbs. The inclusion of adverbs here requires that traditional adverbs that are inflected in comparison be classified as adjectives, as is sometimes done.Adverbs

Adverbs can be formed from adjectives in Norwegian. English usually creates adverbs from adjectives by the suffix ''-ly'', like the adverb ''beautifully'' from the adjective ''beautiful.'' By comparison,Scandinavian languages

The North Germanic languages make up one of the three branches of the Germanic languages—a sub-family of the Indo-European languages—along with the West Germanic languages and the extinct East Germanic languages. The language group is al ...

usually form adverbs from adjectives by the grammatical neuter singular form of the adjective. This is in general true for both Bokmål and Nynorsk.

Example ( Bokmål):

* ('He is terribleNynorsk

Nynorsk (; ) is one of the two official written standards of the Norwegian language, the other being Bokmål. From 12 May 1885, it became the state-sanctioned version of Ivar Aasen's standard Norwegian language (''Landsmål''), parallel to the Da ...

):

* ('She is beautifulCompound words

In Norwegian compound words, thehead

A head is the part of an organism which usually includes the ears, brain, forehead, cheeks, chin, eyes, nose, and mouth, each of which aid in various sensory functions such as sight, hearing, smell, and taste. Some very simple ani ...

, i.e. the part determining the compound's class, is the last part. If the compound word is constructed from many different nouns, the last noun in the compound noun will determine the gender of the compound noun. Only the first part has primary stress. For instance, the compound ('think tank') has primary stress on the first syllable and is a masculine noun since the noun is masculine.

Compound words are written together in Norwegian, which can cause words to become very long, for example (' maximum likelihood estimator') and ('human rights organizations'). Other examples are the title ('Chief Justice of the Supreme Court', originally a combination of '' supreme court'' and the actual title, '' justiciar'') and the translation for ''A Midsummer Night's Dream''.

If they are not written together, each part is naturally read with primary stress, and the meaning of the compound is lost. Examples of this in English are the difference between a green house and a greenhouse or a black board and a blackboard.

This is sometimes forgotten, occasionally with humorous results. Instead of writing, for example, ' ('lamb chops'), people make the mistake of writing ('lame', or 'paralyzed', 'chops'). The original message can even be reversed, as when (lit. 'smoke-free', meaning no smoking) becomes ('smoke freely').

Other examples include:

* ('Terrace dies') instead of ('Terrace door')

* ('Tuna bites', verb) instead of ('Tuna bits', noun)

* ('Lard calls', verb) instead of ('Doughnuts')

* ('Theft guaranteed') instead of ('Theft-proof')

* ('Fried chicken lives', verb) instead of ('Fried chicken liver', noun)

* ('Butter bread', verb) instead of ('Sandwich')

* ('Cut fish', verb) instead of ('Clipfish')

* ('On cottage the roof') instead of ('On the cottage roof')

* ('Too Norway') instead of ('Everything for Norway', the royal motto of Norway)

These misunderstandings occur because most nouns can be interpreted as verbs or other types of words.

Similar misunderstandings can be achieved in English too. The following are examples of phrases that both in Norwegian and English mean one thing as a compound word, and something different when regarded as separate words:

* ('spellchecker') or ('spell checker')

* ('cookbook') or ('cook book')

* ('real handmade waffles') or ('real hand made waffles')

Syntax

Word order

Norwegian syntax is predominantly SVO. The subject occupies the sentence-initial position, followed by the verb and then the object. Like many other Germanic languages, it follows the V2 rule, which means that the finite verb is invariably the second element in a sentence. For example: * ('I eat fish ''today''= Negation

= Negation in Norwegian is expressed by the word , which literally means 'not' and is placed after the finite verb. Exceptions are embedded clauses. * ('The dog did not return with the ball.') * ('It was the dog that did not return.') Contractions with the negation, as is accepted in for example English (''cannot'', ''hadn't'', ''didn't'') are limited to dialects and colloquial speech. In this case contractions apply to the negation and the verb. Otherwise is applied in similar ways as the English ''not'' and general negation.= Adverbs

= Adverbs follow the verb they modify. Depending on the type of adverb, the order in which they appear in the phrase is pre-determined. Manner adverbs for example, precede temporal adverbs. Switching the order of these adverbs would not render the phrase ungrammatical, but would make it sound awkward. Compare this to the English phrase "John probably already ate dinner." Switching the adverbs' position (''already'' and ''probably'') to "John already probably ate dinner" is not incorrect, but sounds unnatural. For more information, see Cartographic syntax. * ('She sang touchingly beautiful.') * ('She sang unbelievably loud.') The adverb may precede the verb when the focus of the sentence is shifted. If special attention should be directed on the temporal aspect of the sentence, the adverb can be fronted. Since the V2 rule requires the finite verb to syntactically occupy the second position in the clause, the verb consequently also moves in front of the subject. * . (Today'', I want to drink coffee.') * . (Today'', I eat fish.') Only one adverb may precede the verb, unless it belongs to a bigger constituent, in which case it does not modify the main verb in the phrase, but is part of the constituent. * . ('She ate the soup quickly yesterday.') * . ('Yesterday she ate the soup quickly.') * , ('The team that played the best had left the pitch.')= Adjectives

= Attributive adjectives always precede the noun that they modify. * ('The three big fat heavy red books stood on the shelf.') * ('The other fortunately long thin key fit'.)See also

* Det Norske Akademi for Sprog og Litteratur * Comparison of Danish, Norwegian and Swedish * Noregs Mållag * Norsk Ordbok * Riksmålsforbundet * Russenorsk * Tone (linguistics)References

Bibliography

* Olav T. Beito, ''Nynorsk grammatikk. Lyd- og ordlære'', Det Norske Samlaget, Oslo 1986, * Rolf Theil Endresen, Hanne Gram Simonsen, Andreas Sveen, ''Innføring i lingvistikk'' (2002), * Jan Terje Faarlund, Svein Lie, Kjell Ivar Vannebo, ''Norsk referansegrammatikk'', Universitetsforlaget, Oslo 1997, 2002 (3rd edition), (Bokmål and Nynorsk) * Philip Holmes, Hans-Olav Enger, ''Norwegian: A Comprehensive Grammar'', Routledge, Abingdon, 2018, * The Norwegian Language Council (1994), ''Language usage in Norway's civil service''in English

* Arne Torp, Lars S. Vikør (1993), ''Hovuddrag i norsk språkhistorie (3.utgåve)'', Gyldendal Norsk Forlag AS 2003 * Lars S. Vikør (2015), ''Norwegian: Bokmål vs. Nynorsk''

on Språkrådet's website

External links

Ordboka

– Online dictionary search, both Bokmål and Nynorsk. *

Norwegian as a Normal Language

in English, at ''Språkrådet''

Ordbøker og nettressurser

– a collection of dictionaries and online resources (in Norwegian) from ''Språkrådet'' {{DEFAULTSORT:Norwegian Language Norwegian language Fusional languages Languages of Norway North Germanic languages Scandinavian culture Stress-timed languages Subject–verb–object languages Tonal languages Verb-second languages West Scandinavian languages