Liszt Ferenc Tér on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

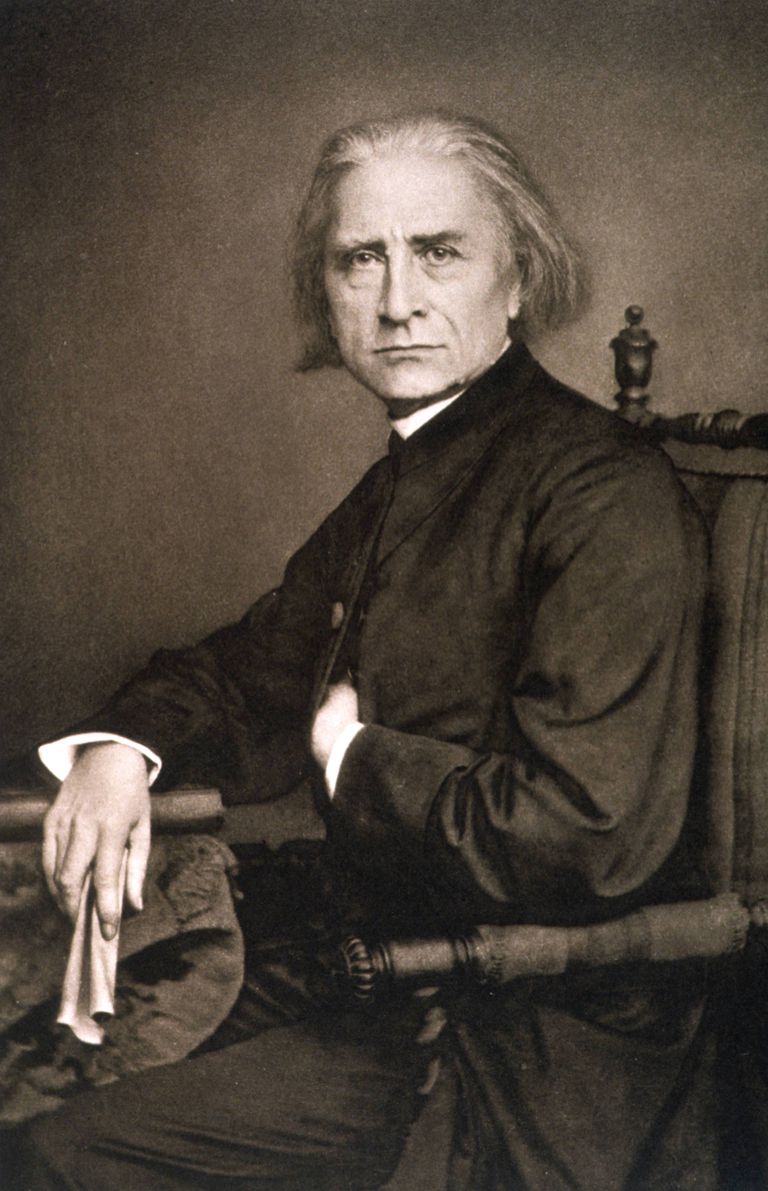

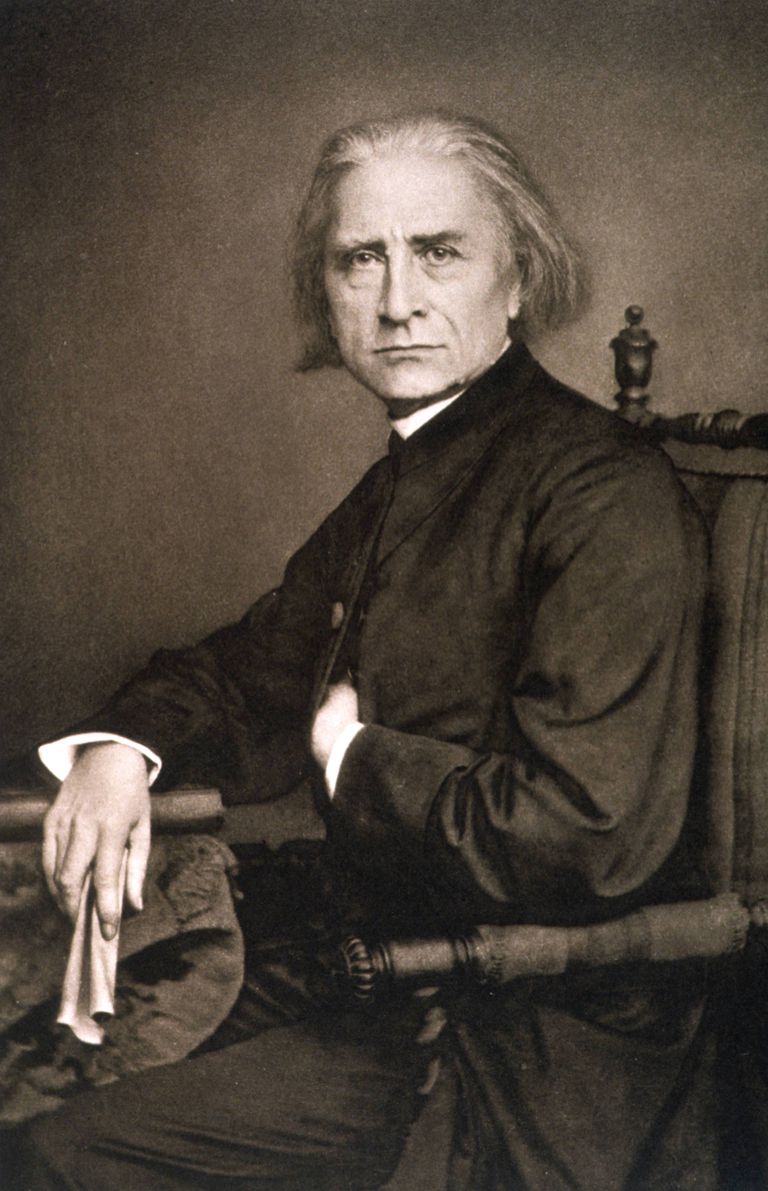

Franz Liszt (22 October 1811 – 31 July 1886) was a Hungarian composer,

Liszt fell very ill, to the extent that an obituary notice was printed in a Paris newspaper, and he underwent a long period of religious doubts and introspection. He stopped playing the piano and giving lessons, and developed an intense interest in religion, having many conversations with Abbé de Lamennais and Chrétien Urhan, a German-born violinist who introduced him to the Saint-Simonists. Lamennais dissuaded Liszt from becoming a monk or priest. Urhan was an early champion of Schubert, inspiring Liszt's own lifelong love of Schubert's songs. Much of Urhan's emotive music which moved beyond the Classical paradigm, such as ''Elle et moi, La Salvation angélique'' and ''Les Regrets'', may have helped to develop Liszt's taste and style.

During this period Liszt came into contact with many of the leading authors and artists of his day, including

Liszt fell very ill, to the extent that an obituary notice was printed in a Paris newspaper, and he underwent a long period of religious doubts and introspection. He stopped playing the piano and giving lessons, and developed an intense interest in religion, having many conversations with Abbé de Lamennais and Chrétien Urhan, a German-born violinist who introduced him to the Saint-Simonists. Lamennais dissuaded Liszt from becoming a monk or priest. Urhan was an early champion of Schubert, inspiring Liszt's own lifelong love of Schubert's songs. Much of Urhan's emotive music which moved beyond the Classical paradigm, such as ''Elle et moi, La Salvation angélique'' and ''Les Regrets'', may have helped to develop Liszt's taste and style.

During this period Liszt came into contact with many of the leading authors and artists of his day, including  After attending a concert featuring

After attending a concert featuring

After his separation from Marie, Liszt continued to tour Europe. His concerts in Berlin in the winter of 18411842 marked the start of a period of immense public enthusiasm and popularity for his performances, dubbed "

After his separation from Marie, Liszt continued to tour Europe. His concerts in Berlin in the winter of 18411842 marked the start of a period of immense public enthusiasm and popularity for his performances, dubbed "

In July 1848 Liszt settled in Weimar, where he had been appointed the honorary title of "

In July 1848 Liszt settled in Weimar, where he had been appointed the honorary title of "

After a visit to Rome and an audience with

After a visit to Rome and an audience with

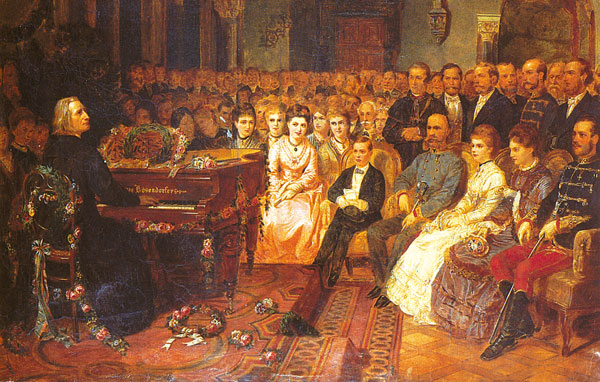

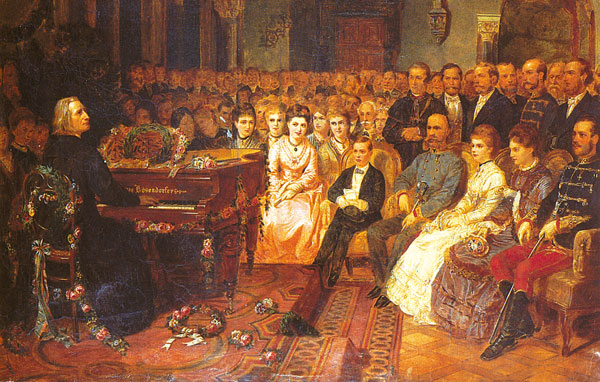

Up to 1840, most concerts featuring a solo pianist included other acts, such as an orchestra, singers and ballet. The increasing prominence of the solo piano virtuoso in the 1830s led to other acts on the bill being described as "assistant artists", with Liszt declaring his pre-eminence in a letter to a friend dated June 1839: "Le concert, c'est moi". Liszt is credited as the first pianist to give solo recitals in the modern sense of the word; the term was first applied to Liszt's concert at the

Up to 1840, most concerts featuring a solo pianist included other acts, such as an orchestra, singers and ballet. The increasing prominence of the solo piano virtuoso in the 1830s led to other acts on the bill being described as "assistant artists", with Liszt declaring his pre-eminence in a letter to a friend dated June 1839: "Le concert, c'est moi". Liszt is credited as the first pianist to give solo recitals in the modern sense of the word; the term was first applied to Liszt's concert at the

After arriving in Paris in 1823,

After arriving in Paris in 1823,

Liszt's main contribution to program music was his thirteen symphonic poems, one-movement orchestral works in which some extramusical program or idea provides a narrative or illustrative element. The first twelve of these were written between 1848 and 1858, and the most well-known are ''

Liszt's main contribution to program music was his thirteen symphonic poems, one-movement orchestral works in which some extramusical program or idea provides a narrative or illustrative element. The first twelve of these were written between 1848 and 1858, and the most well-known are ''

American Liszt Society

* Programmes examining the life and works of Franz Liszt. :Scores * * * :Books * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Liszt, Franz Franz Liszt, 1811 births 1886 deaths 19th-century Hungarian classical composers 19th-century classical pianists 19th-century conductors (music) 19th-century Hungarian musicians 19th-century Hungarian male musicians 19th-century organists Catholic liturgical composers Classical composers of church music Composers for pedal piano Composers for piano Composers for pipe organ Academic staff of the Franz Liszt Academy of Music Honorary members of the Royal Philharmonic Society Pupils of Anton Reicha Hungarian classical organists Hungarian classical pianists Hungarian Freemasons Hungarian music educators Hungarian opera composers Hungarian people of German descent Hungarian philanthropists Hungarian Romantic composers Male classical pianists Hungarian male conductors (music) Hungarian male opera composers Hungarian male classical organists Members of the Third Order of Saint Francis Musicians from Paris Musicians from Weimar Organ improvisers People from Oberpullendorf District Piano educators Pupils of Carl Czerny Recipients of the Pour le Mérite (civil class) Hungarian emigrants to Germany Lieder composers

virtuoso

A virtuoso (from Italian ''virtuoso'', or ; Late Latin ''virtuosus''; Latin ''virtus''; 'virtue', 'excellence' or 'skill') is an individual who possesses outstanding talent and technical ability in a particular art or field such as fine arts, ...

pianist, conductor and teacher of the Romantic period

Romanticism (also known as the Romantic movement or Romantic era) was an artistic and intellectual movement that originated in Europe towards the end of the 18th century. The purpose of the movement was to advocate for the importance of subjec ...

. With a diverse body of work spanning more than six decades, he is considered to be one of the most prolific and influential composers of his era, and his piano works continue to be widely performed and recorded.

Liszt achieved success as a concert pianist from an early age, and received lessons from the esteemed musicians Carl Czerny

Carl Czerny (; ; 21 February 1791 – 15 July 1857) was an Austrian composer, teacher, and pianist of Czech origin whose music spanned the late Classical and early Romantic eras. His vast musical production amounted to over a thousand works an ...

and Antonio Salieri

Antonio Salieri (18 August 17507 May 1825) was an Italian composer and teacher of the classical period (music), classical period. He was born in Legnago, south of Verona, in the Republic of Venice, and spent his adult life and career as a subje ...

. He gained further renown for his performances during tours of Europe in the 1830s and 1840s, developing a reputation for technical brilliance as well as physical attractiveness. In a phenomenon dubbed "Lisztomania

Lisztomania or Liszt fever was the intense fan frenzy directed toward Hungarian composer Franz Liszt during his performances. This frenzy first occurred in Berlin in 1841 and the term was later coined by Heinrich Heine in a feuilleton he wrote o ...

", he rose to a degree of stardom and popularity among the public not experienced by the virtuosos who preceded him.

During this period and into his later life, Liszt was a friend, musical promoter and benefactor to many composers of his time, including Hector Berlioz

Louis-Hector Berlioz (11 December 1803 – 8 March 1869) was a French Romantic music, Romantic composer and conductor. His output includes orchestral works such as the ''Symphonie fantastique'' and ''Harold en Italie, Harold in Italy'' ...

, Frédéric Chopin

Frédéric François Chopin (born Fryderyk Franciszek Chopin; 1 March 181017 October 1849) was a Polish composer and virtuoso pianist of the Romantic period who wrote primarily for Piano solo, solo piano. He has maintained worldwide renown ...

, Robert Schumann

Robert Schumann (; ; 8 June 181029 July 1856) was a German composer, pianist, and music critic of the early Romantic music, Romantic era. He composed in all the main musical genres of the time, writing for solo piano, voice and piano, chamber ...

, Clara Schumann

Clara Josephine Schumann (; ; née Wieck; 13 September 1819 – 20 May 1896) was a German pianist, composer, and piano teacher. Regarded as one of the most distinguished pianists of the Romantic music, Romantic era, she exerted her influence o ...

and Richard Wagner

Wilhelm Richard Wagner ( ; ; 22 May 181313 February 1883) was a German composer, theatre director, essayist, and conductor who is chiefly known for his operas (or, as some of his mature works were later known, "music dramas"). Unlike most o ...

, among others. Liszt coined the terms " transcription" and "paraphrase", and would perform arrangements of his contemporaries' music to popularise it. Alongside Wagner, Liszt was one of the most prominent representatives of the New German School

The New German School (, ) is a term introduced in 1859 by Franz Brendel, editor of the ''Neue Zeitschrift für Musik'', to describe certain trends in German music. Although the term has frequently been used in essays and books about music histo ...

, a progressive group of composers involved in the "War of the Romantics

The "War of the Romantics" is a term used by some music historians to describe the schism among prominent musicians in the second half of the 19th century. Musical structure, the limits of chromatic harmony, and program music versus absolute mu ...

" who developed ideas of programmatic music

Program music or programmatic music is a type of instrumental art music that attempts to musically render an extramusical narrative. The narrative itself might be offered to the audience through the piece's title, or in the form of program not ...

and harmonic experimentation.

Liszt taught piano performance to hundreds of students throughout his life, many of whom went on to become notable performers. He left behind an extensive and diverse body of work that influenced his forward-looking contemporaries and anticipated 20th-century ideas and trends. Among Liszt's musical contributions were the concept of the symphonic poem

A symphonic poem or tone poem is a piece of orchestral music, usually in a single continuous movement, which illustrates or evokes the content of a poem, short story, novel, painting, landscape, or other (non-musical) source. The German term ( ...

, innovations in thematic transformation Thematic transformation (also known as thematic metamorphosis or thematic development) is a musical technique in which a leitmotif, or theme, is developed by changing the theme by using permutation ( transposition or modulation, inversion, and ret ...

and Impressionism in music

Impressionism in music was a movement among various composers in Western classical music (mainly during the late 19th and early 20th centuries) whose music focuses on mood and atmosphere, "conveying the moods and emotions aroused by the subject ...

, and the invention of the masterclass

Yanka Industries, Inc., doing business as MasterClass, is an American online education subscription platform on which students can access tutorials and lectures pre-recorded by experts in various fields. The concept for MasterClass was conceiv ...

as a method of teaching performance. In a radical departure from his earlier compositional styles, many of Liszt's later works also feature experiments in atonality

Atonality in its broadest sense is music that lacks a tonal center, or key. ''Atonality'', in this sense, usually describes compositions written from about the early 20th-century to the present day, where a hierarchy of harmonies focusing on ...

, foreshadowing developments in 20th-century classical music

20th-century classical music is Western art music that was written between the years 1901 and 2000, inclusive. Musical style diverged during the 20th century as it never had previously, so this century was without a dominant style. Modernism, i ...

. Today he is best known for his original piano works, such as the Hungarian Rhapsodies

The Hungarian Rhapsodies, S.244, R.106 (, , ), are a set of 19 piano pieces based on Hungarian folk themes, composed by Franz Liszt during 1846–1853, and later in 1882 and 1885. Liszt also arranged versions for orchestra, piano duet and pia ...

, '' Années de pèlerinage'', ''Transcendental Études

The ''Transcendental Études'' (), S.139, is a set of twelve compositions for piano by Franz Liszt. They were published in 1852 as a revision of an 1837 set (which had not borne the title "d'exécution transcendante"), which in turn were – f ...

'', " La campanella", and the Piano Sonata in B minor.

Life

Early life

Franz Liszt was born to Anna Liszt (née Maria Anna Lager) andAdam Liszt

Adamus List (; 16 December 177628 August 1827) was the father of composer and pianist Franz Liszt. Family background

As the second child of Georg Adam List and Katharina (née Baumann), he was born in Edelstal, Nemesvölgy (today Edelstal, Austri ...

on 22 October 1811, in the village of Doborján () in Sopron County

Sopron (German language, German: ''Ödenburg'', Slovak language, Slovak: ''Šopron'') was an administrative county (Comitatus (Kingdom of Hungary), comitatus) of the Kingdom of Hungary. Its territory is now divided between Austria and Hungary. Th ...

, in the Kingdom of Hungary

The Kingdom of Hungary was a monarchy in Central Europe that existed for nearly a millennium, from 1000 to 1946 and was a key part of the Habsburg monarchy from 1526-1918. The Principality of Hungary emerged as a Christian kingdom upon the Coro ...

, Austrian Empire

The Austrian Empire, officially known as the Empire of Austria, was a Multinational state, multinational European Great Powers, great power from 1804 to 1867, created by proclamation out of the Habsburg monarchy, realms of the Habsburgs. Duri ...

. Liszt's father was a land steward in the service of Prince Nikolaus II Esterházy; a keen amateur musician, he played the piano, cello, guitar and flute, and knew Haydn

Franz Joseph Haydn ( ; ; 31 March 173231 May 1809) was an Austrian composer of the Classical period (music), Classical period. He was instrumental in the development of chamber music such as the string quartet and piano trio. His contributions ...

and Hummel personally. A renowned child prodigy

A child prodigy is, technically, a child under the age of 10 who produces meaningful work in some domain at the level of an adult expert. The term is also applied more broadly to describe young people who are extraordinarily talented in some f ...

, Franz began to improvise at the piano from before the age of five, and his father diligently encouraged his progress. Franz also found exposure to music through attending Mass, as well as travelling Romani

Romani may refer to:

Ethnic groups

* Romani people, or Roma, an ethnic group of Indo-Aryan origin

** Romani language, an Indo-Aryan macrolanguage of the Romani communities

** Romanichal, Romani subgroup in the United Kingdom

* Romanians (Romanian ...

bands that toured the Hungarian countryside. His first public concert was in Sopron

Sopron (; , ) is a city in Hungary on the Austrian border, near Lake Neusiedl/Lake Fertő.

History

Ancient times-13th century

In the Iron Age a hilltop settlement with a burial ground existed in the neighbourhood of Sopron-Várhely.

When ...

in 1820 at the age of nine; its success led to further appearances in Pressburg

Bratislava (German: ''Pressburg'', Hungarian: ''Pozsony'') is the Capital city, capital and largest city of the Slovakia, Slovak Republic and the fourth largest of all List of cities and towns on the river Danube, cities on the river Danube. ...

and for Prince Nikolaus' court in Eisenstadt

Eisenstadt (; ; ; or ; ) is the capital city of the Provinces of Austria, Austrian state of Burgenland. With a population of 15,074 (as of 2023), it is the smallest state capital and the 38th-largest city in Austria overall. It lies at the foot o ...

. The publicity led to a group of wealthy sponsors offering to finance Franz's musical education in Vienna.

There, Liszt received piano lessons from Carl Czerny

Carl Czerny (; ; 21 February 1791 – 15 July 1857) was an Austrian composer, teacher, and pianist of Czech origin whose music spanned the late Classical and early Romantic eras. His vast musical production amounted to over a thousand works an ...

, who in his own youth had been a student of Beethoven and Hummel. Czerny, already extremely busy, had only grudgingly agreed to hear Liszt play, and had initially refused to entertain the idea of regular lessons. Being so impressed by the initial audition, however, Czerny taught Liszt regularly, free of charge, for the next eighteen months, at which point he felt he had nothing more to teach. Liszt remained grateful to his former teacher, later dedicating to him the ''Transcendental Études

The ''Transcendental Études'' (), S.139, is a set of twelve compositions for piano by Franz Liszt. They were published in 1852 as a revision of an 1837 set (which had not borne the title "d'exécution transcendante"), which in turn were – f ...

'' on their 1830 republication. Liszt also received lessons in composition from Antonio Salieri

Antonio Salieri (18 August 17507 May 1825) was an Italian composer and teacher of the classical period (music), classical period. He was born in Legnago, south of Verona, in the Republic of Venice, and spent his adult life and career as a subje ...

, the accomplished music director of the Viennese court who had previously taught Beethoven

Ludwig van Beethoven (baptised 17 December 177026 March 1827) was a German composer and pianist. He is one of the most revered figures in the history of Western music; his works rank among the most performed of the classical music repertoire ...

and Schubert

Franz Peter Schubert (; ; 31 January 179719 November 1828) was an Austrian composer of the late Classical period (music), Classical and early Romantic music, Romantic eras. Despite his short life, Schubert left behind a List of compositions ...

. Like Czerny, Salieri was highly impressed by Liszt's improvisation and sight-reading abilities.

Liszt's public debut in Vienna on 1 December 1822 was a great success. He was greeted in Austrian and Hungarian aristocratic circles and met Beethoven and Schubert

Franz Peter Schubert (; ; 31 January 179719 November 1828) was an Austrian composer of the late Classical period (music), Classical and early Romantic music, Romantic eras. Despite his short life, Schubert left behind a List of compositions ...

. To build on his son's success, Adam Liszt decided to take the family to Paris, the centre of the artistic world. At Liszt's final Viennese concert on 13 April 1823, Beethoven was reputed to have walked onstage and kissed Liszt on the forehead, to signify a kind of artistic christening. There is debate, however, on the extent to which this story is apocryphal. The family briefly returned to Hungary, and Liszt played a concert in traditional Hungarian dress, in order to emphasise his roots, in May 1823.

In 1824 a piece Liszt had written at the age of 11 – his Variation on a Waltz by Diabelli (S. 147) – appeared in of ''Vaterländischer Künstlerverein

''Vaterländischer Künstlerverein'' was a collaborative musical publication or anthology, incorporating 83 variations for piano on a theme by Anton Diabelli, written by 51 composers living in or associated with Austria. It was published in tw ...

'' as his first published composition. This volume, commissioned by Anton Diabelli

Anton (or Antonio) Diabelli (5 September 17818 April 1858) was an Austrian music publisher, editor and composer. Best known in his time as a publisher, he is most familiar today as the composer of the waltz on which Ludwig van Beethoven wrote ...

, includes 50 variations on his waltz by 50 different composers ( being taken up by Beethoven's 33 variations on the same theme, which are now separately better known simply as his ''Diabelli Variations

The ''33 Variations on a waltz by Anton Diabelli'', Op. 120, commonly known as the ''Diabelli Variations'', is a set of variations for the piano written between 1819 and 1823 by Ludwig van Beethoven on a waltz composed by Anton Diabelli. It for ...

''). Liszt was the youngest contributor to the project, described in it as "a boy of eleven years old"; Czerny was also a participant.

Paris

Having made significant sums from his concerts, Liszt and his family moved to Paris in 1823, with the hope of his attending theConservatoire de Paris

The Conservatoire de Paris (), or the Paris Conservatory, is a college of music and dance founded in 1795. Officially known as the Conservatoire National Supérieur de Musique et de Danse de Paris (; CNSMDP), it is situated in the avenue Jean Ja ...

. Even with a letter of recommendation from Chancellor Klemens von Metternich

Klemens Wenzel Nepomuk Lothar, Prince of Metternich-Winneburg zu Beilstein ( ; 15 May 1773 – 11 June 1859), known as Klemens von Metternich () or Prince Metternich, was a German statesman and diplomat in the service of the Austrian Empire. ...

, director Luigi Cherubini

Maria Luigi Carlo Zenobio Salvatore Cherubini ( ; ; 8 or 14 SeptemberWillis, in Sadie (Ed.), p. 833 1760 – 15 March 1842) was an Italian Classical and Romantic composer. His most significant compositions are operas and sacred music. Beethov ...

refused his entry, however, as the Conservatoire did not accept foreigners. Nevertheless, Liszt studied under Anton Reicha

Anton (Antonín, Antoine) Joseph Reicha (Rejcha) (26 February 1770 – 28 May 1836) was a Czech-born, Bavarian-educated, later naturalization, naturalized French composer and music theorist. A contemporary and lifelong friend of Ludwig van Be ...

and Ferdinando Paer

Ferdinando Paer (1 June 1771 – 3 May 1839) was an Italian composer known for his operas. He was of Austrian descent and used the German spelling Pär in application for printing in Venice, and later in France the spelling Paër.

Life

He was bor ...

, and gave a series of highly successful concerts debuting on 8 March 1824. Paer was involved in the Parisian theatrical and operatic scene, and through his connections Liszt staged his only opera, ''Don Sanche

''Don Sanche, ou Le château de l'amour'' (), S.1, is an opera in one act composed in 1824–25 by Franz Liszt in his early teen years, with French libretto by Théaulon and de Rancé, based on a story by Jean-Pierre Claris de Florian. For 30 y ...

'', which premiered shortly before his fourteenth birthday. The premiere was warmly received, but the opera only ran for four performances, and is now obscure. Accompanied by his father, Liszt toured France and England, where he played for King George IV

George IV (George Augustus Frederick; 12 August 1762 – 26 June 1830) was King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and King of Hanover from 29 January 1820 until his death in 1830. At the time of his accession to the throne, h ...

.

Adam Liszt died suddenly of typhoid fever

Typhoid fever, also known simply as typhoid, is a disease caused by '' Salmonella enterica'' serotype Typhi bacteria, also called ''Salmonella'' Typhi. Symptoms vary from mild to severe, and usually begin six to 30 days after exposure. Often th ...

in the summer of 1827, and for the next eight years Liszt continued to live in Paris with his mother. He gave up touring, and in order to earn money, he gave lessons on piano and composition, often from early morning until late at night. His students were scattered across the city and he had to cover long distances. Because of this, he kept uncertain hours and also took up smoking and drinking, habits he would continue throughout his life. During this period Liszt fell in love with one of his pupils, Caroline de Saint-Cricq, the daughter of Charles X Charles X may refer to:

* Charles X of France (1757–1836)

* Charles X Gustav (1622–1660), King of Sweden

* Charles, Cardinal de Bourbon (1523–1590), recognized as Charles X of France but renounced the royal title

See also

*

* King Charle ...

's minister of commerce, Pierre de Saint-Cricq. Her father, however, insisted that the affair be broken off.

Liszt fell very ill, to the extent that an obituary notice was printed in a Paris newspaper, and he underwent a long period of religious doubts and introspection. He stopped playing the piano and giving lessons, and developed an intense interest in religion, having many conversations with Abbé de Lamennais and Chrétien Urhan, a German-born violinist who introduced him to the Saint-Simonists. Lamennais dissuaded Liszt from becoming a monk or priest. Urhan was an early champion of Schubert, inspiring Liszt's own lifelong love of Schubert's songs. Much of Urhan's emotive music which moved beyond the Classical paradigm, such as ''Elle et moi, La Salvation angélique'' and ''Les Regrets'', may have helped to develop Liszt's taste and style.

During this period Liszt came into contact with many of the leading authors and artists of his day, including

Liszt fell very ill, to the extent that an obituary notice was printed in a Paris newspaper, and he underwent a long period of religious doubts and introspection. He stopped playing the piano and giving lessons, and developed an intense interest in religion, having many conversations with Abbé de Lamennais and Chrétien Urhan, a German-born violinist who introduced him to the Saint-Simonists. Lamennais dissuaded Liszt from becoming a monk or priest. Urhan was an early champion of Schubert, inspiring Liszt's own lifelong love of Schubert's songs. Much of Urhan's emotive music which moved beyond the Classical paradigm, such as ''Elle et moi, La Salvation angélique'' and ''Les Regrets'', may have helped to develop Liszt's taste and style.

During this period Liszt came into contact with many of the leading authors and artists of his day, including Victor Hugo

Victor-Marie Hugo, vicomte Hugo (; 26 February 1802 – 22 May 1885) was a French Romanticism, Romantic author, poet, essayist, playwright, journalist, human rights activist and politician.

His most famous works are the novels ''The Hunchbac ...

, Alphonse de Lamartine

Alphonse Marie Louis de Prat de Lamartine (; 21 October 179028 February 1869) was a French author, poet, and statesman. Initially a moderate royalist, he became one of the leading critics of the July Monarchy of Louis-Philippe, aligning more w ...

, George Sand

Amantine Lucile Aurore Dupin de Francueil (; 1 July 1804 – 8 June 1876), best known by her pen name George Sand (), was a French novelist, memoirist and journalist. Being more renowned than either Victor Hugo or Honoré de Balz ...

and Alfred de Vigny

Alfred Victor, Comte de Vigny (; 27 March 1797 – 17 September 1863) was a French poet and early French Romanticism, Romanticist. He also produced novels, plays, and translations of Shakespeare.

Biography

Vigny was born in Loches (a town to wh ...

. He composed practically nothing in the years between his father's death and the July Revolution of 1830

The French Revolution of 1830, also known as the July Revolution (), Second French Revolution, or ("Three Glorious ays), was a second French Revolution after the first of 1789–99. It led to the overthrow of King Charles X, the French B ...

, which inspired him to sketch a symphony based on the events of the "three glorious days" (this piece was left unfinished, and later reworked as '' Héroïde funèbre''). Liszt met Hector Berlioz

Louis-Hector Berlioz (11 December 1803 – 8 March 1869) was a French Romantic music, Romantic composer and conductor. His output includes orchestral works such as the ''Symphonie fantastique'' and ''Harold en Italie, Harold in Italy'' ...

on 4 December 1830, the day before the premiere of the ''Symphonie fantastique

' (''Fantastic Symphony: Episode in the Life of an Artist … in Five Sections'') Opus number, Op. 14, is a program music, programmatic symphony written by Hector Berlioz in 1830. The first performance was at the Paris Conservatoire on 5 December ...

''. Berlioz's music made a strong impression on Liszt, and the two quickly became friends. Liszt also befriended Frédéric Chopin

Frédéric François Chopin (born Fryderyk Franciszek Chopin; 1 March 181017 October 1849) was a Polish composer and virtuoso pianist of the Romantic period who wrote primarily for Piano solo, solo piano. He has maintained worldwide renown ...

around this time.

After attending a concert featuring

After attending a concert featuring Niccolò Paganini

Niccolò (or Nicolò) Paganini (; ; 27 October 178227 May 1840) was an Italian violinist and composer. He was the most celebrated violin virtuoso of his time, and left his mark as one of the pillars of modern violin technique. His 24 Caprices ...

in April 1832, Liszt resolved to become as great a virtuoso on the piano as Paganini was on the violin. He dramatically increased his practice, sometimes practising for up to fourteen hours a day, and in 1838 published the six ''Études d'exécution transcendante d'après Paganini'' (later revised as '' Grandes études de Paganini''), aiming to represent Paganini's virtuosity on the keyboard. The process of Liszt completely redeveloping his technique is often described as a direct result of attending Paganini's concert, but it is likely that he had already begun this work previously, during the period 18281832.

Touring Europe

Affair with Countess Marie d'Agoult

In 1833, Liszt began a relationship with the CountessMarie d'Agoult

Marie Catherine Sophie, Comtesse d'Agoult (born de Flavigny; 31 December 18055 March 1876), was a French romanticism, romantic author and historian, known also by her pen name, Daniel Stern.

Life

Marie was born in Frankfurt am Main, Germany, w ...

, who was married to a French cavalry officer but living independently. In order to escape scandal they moved to Geneva

Geneva ( , ; ) ; ; . is the List of cities in Switzerland, second-most populous city in Switzerland and the most populous in French-speaking Romandy. Situated in the southwest of the country, where the Rhône exits Lake Geneva, it is the ca ...

in 1835; their daughter Blandine was born there on 18 December. Liszt taught at the newly founded Geneva Conservatoire and contributed essays for ''L'Artiste

''L’Artiste'' was a weekly illustrated review published in Paris from 1831 to 1904, supplying "the richest single source of contemporary commentary on artists, exhibitions and trends from the Romanticism, Romantic era to the end of the ninetee ...

'' and the ''Revue et gazette musicale de Paris

The ' () was a weekly musical review founded in 1827 by the Belgian musicologist, teacher and composer François-Joseph Fétis, then working as professor of counterpoint and fugue at the Conservatoire de Paris. It was the first French-languag ...

''.

For the next four years, Liszt and the countess lived together. In 1835 and 1836 they travelled around Switzerland, and from August 1837 until November 1839 they toured Italy. It was these travels that later inspired the composer to write his cycle of piano collections entitled '' Années de pèlerinage'' (''Years of Pilgrimage''). Their daughter, Cosima, was born in Como

Como (, ; , or ; ) is a city and (municipality) in Lombardy, Italy. It is the administrative capital of the Province of Como. Nestled at the southwestern branch of the picturesque Lake Como, the city is a renowned tourist destination, ce ...

on 24 December 1837, and their son Daniel on 9 May 1839 in Rome

Rome (Italian language, Italian and , ) is the capital city and most populated (municipality) of Italy. It is also the administrative centre of the Lazio Regions of Italy, region and of the Metropolitan City of Rome. A special named with 2, ...

.

That autumn relations between them became strained. Liszt heard that plans for a Beethoven Monument in Bonn were in danger of collapse for lack of funds and pledged his support, raising funds through concerts. The countess returned to Paris with the children, while Liszt gave six concerts in Vienna, then toured Hungary. Liszt would later spend holidays with Marie and their children on the island of Nonnenwerth on the Rhine in the summers of 1841 and 1843. In May 1844, the couple finally separated.

The Ivory Duel

Swiss pianistSigismond Thalberg

Sigismond Thalberg (8 January 1812 – 27 April 1871) was an Austrian composer and one of the most distinguished virtuoso pianists of the 19th century.

Family

Thalberg was born in Pâquis near Geneva on 8 January 1812. Thalberg asserted that he ...

moved to Paris in 1835 after several successful years of touring. His concerts there were extremely well received, and Liszt, at the time living in Geneva, received news of them from his friends in Paris. In the autumn of 1836 Liszt published an unfavourable review of several of Thalberg's compositions in the ''Gazette musicale'', calling them "boring" and "mediocre". A published exchange of views ensued between Liszt and Thalberg's supporter, the critic François-Joseph Fétis

François-Joseph Fétis (; 25 March 1784 – 26 March 1871) was a Belgian musicologist, critic, teacher and composer. He was among the most influential music intellectuals in continental Europe. His enormous compilation of biographical data in the ...

.

Liszt heard Thalberg perform for the first time at the Paris Conservatoire in February 1837, and to settle the disagreement the two pianists each arranged a performance for the public to compare them the following month. Liszt performed his own ''Grande fantaisie sur des motifs de Niobe'' and Weber's '' Konzertstück in F minor''. This was considered to be inconclusive, so the two agreed to perform at the same concert for comparison on 31 March, at the salon of the Princess of Belgiojoso, in aid of Italian refugees. Thalberg opened with his ''Fantasia on Rossini's "Moses"'', then Liszt performed his ''Niobe'' fantasy.

The result of this "duel" is disputed. Critic Jules Janin

Jules Gabriel Janin (; 16 February 1804 – 19 June 1874) was a French writer and critic.

Life and career

Born in Saint-Étienne (Loire), Janin's father was a lawyer, and he was educated first at St. Étienne, and then at the lycée Louis-le-Gr ...

's report in ''Journal des débats

The ''Journal des débats'' (, ''Journal of Debates'') was a French newspaper, published between 1789 and 1944 that changed title several times. Created shortly after the first meeting of the Estates-General of 1789, it was, after the outbreak ...

'' asserted that there was no clear winner: "Two victors and no vanquished; it is fitting to say with the poet '". Belgiojoso declined to declare a winner, famously concluding that "Thalberg is the first pianist in the worldLiszt is unique." The biographer Alan Walker

Alan Olav Walker (born 24 August 1997) is a Norwegian DJ and record producer. His songs "Faded (Alan Walker song), Faded", "Sing Me to Sleep", "Alone (Alan Walker song), Alone", "All Falls Down (Alan Walker song), All Falls Down" (with Noah Cy ...

, however, believes that "Liszt received the ovation of the evening and all doubts about his supremacy were dispelled. As for Thalberg, his humiliation was complete. He virtually disappeared from the concert platform after this date."

Lisztomania

After his separation from Marie, Liszt continued to tour Europe. His concerts in Berlin in the winter of 18411842 marked the start of a period of immense public enthusiasm and popularity for his performances, dubbed "

After his separation from Marie, Liszt continued to tour Europe. His concerts in Berlin in the winter of 18411842 marked the start of a period of immense public enthusiasm and popularity for his performances, dubbed "Lisztomania

Lisztomania or Liszt fever was the intense fan frenzy directed toward Hungarian composer Franz Liszt during his performances. This frenzy first occurred in Berlin in 1841 and the term was later coined by Heinrich Heine in a feuilleton he wrote o ...

" by Heinrich Heine

Christian Johann Heinrich Heine (; ; born Harry Heine; 13 December 1797 – 17 February 1856) was an outstanding poet, writer, and literary criticism, literary critic of 19th-century German Romanticism. He is best known outside Germany for his ...

in 1844. In a fashion that has been described as similar to "the mass hysteria associated with revivalist meetings or 20th-century rock stars", women fought over his cigar stubs and coffee dregs, and his silk handkerchiefs and velvet gloves, which they ripped to shreds as souvenirs. This atmosphere was fuelled in great part by the artist's mesmeric personality and stage presence: he was regarded as handsome, and Heine wrote of his showmanship during concerts: "How powerful, how shattering was his mere physical appearance".

It is estimated that Liszt appeared in public well over one thousand times during this eight-year period. Moreover, his great fame as a pianist, which he would continue to enjoy long after he had officially retired from the concert stage, was based mainly on his accomplishments during this time.

Adding to his reputation was that Liszt gave away much of the proceeds of his work to charity and humanitarian causes. He donated large sums to the building fund of Cologne Cathedral

Cologne Cathedral (, , officially , English: Cathedral Church of Saint Peter) is a cathedral in Cologne, North Rhine-Westphalia belonging to the Catholic Church. It is the seat of the Archbishop of Cologne and of the administration of the Archd ...

and St. Stephen's Basilica

St. Stephen's Basilica ( ) is a Roman Catholic basilica in Budapest, Hungary. It is named in honour of Stephen, the first King of Hungary (c. 975–1038), whose right hand is housed in the reliquary.

Since the renaming of the primatial see, it ...

in Pest, and made private donations to public services such as hospitals and schools, as well as charitable organizations such as the Leipzig Musicians Pension Fund. After the Great Fire of Hamburg

The great fire of Hamburg began early on 5 May 1842, in Deichstraße and burned until the morning of 8 May, destroying about one third of the buildings in the Altstadt, Hamburg, Altstadt. It killed 51 people and destroyed 1,700 residences and se ...

in May 1842, he gave concerts in aid of those left homeless.

During a tour of Ukraine in 1847, Liszt played in Kiev

Kyiv, also Kiev, is the capital and most populous List of cities in Ukraine, city of Ukraine. Located in the north-central part of the country, it straddles both sides of the Dnieper, Dnieper River. As of 1 January 2022, its population was 2, ...

, where he met the Polish Princess Carolyne zu Sayn-Wittgenstein

Princess Carolyne zu Sayn-Wittgenstein (née Iwanowska, ; 8 February 18199 March 1887) was a Polish noblewoman who is best known for her 40-year relationship with musician Franz Liszt. She was also an amateur journalist and essayist. It is conj ...

. For some time he had been considering retiring from the life of a travelling virtuoso to concentrate on composition, and at this point he made the decision to take up a court position in Weimar

Weimar is a city in the state (Germany), German state of Thuringia, in Central Germany (cultural area), Central Germany between Erfurt to the west and Jena to the east, southwest of Leipzig, north of Nuremberg and west of Dresden. Together w ...

. Having known Liszt for only a few weeks, Carolyne resolved to join him there. After a tour of Turkey and Russia that summer, Liszt gave the final paid concert of his career at Elizabetgrad in September, then spent the winter with the princess at her estate in Woronińce. By retiring from the concert platform at the age of 35, while still at the height of his powers, Liszt succeeded in keeping the legend of his playing untarnished.

Weimar

In July 1848 Liszt settled in Weimar, where he had been appointed the honorary title of "

In July 1848 Liszt settled in Weimar, where he had been appointed the honorary title of "Kapellmeister

( , , ), from German (chapel) and (master), literally "master of the chapel choir", designates the leader of an ensemble of musicians. Originally used to refer to somebody in charge of music in a chapel, the term has evolved considerably in i ...

Extraordinaire" six years previously. He acted as the official court kapellmeister at the expense of Grand Duchess Maria Pavlovna of Russia until 1859, jointly with Hippolyte André Jean Baptiste Chélard

Hippolyte André Jean Baptiste Chélard (1 February 1789 – 12 February 1861) was a French composer, violist, and conductor of the Classical era.

He was born in Paris and studied composition with François-Joseph Gossec and viola with Rodolphe ...

until his retirement in 1852. During this period Liszt acted as conductor at court concerts and on special occasions at the theatre, arranged several festivals celebrating the work of Berlioz and Wagner, and produced the premiere of ''Lohengrin

Lohengrin () is a character in German Arthurian literature. The son of Parzival (Percival), he is a knight of the Holy Grail sent in a boat pulled by swans to rescue a maiden who can never ask his identity. His story, which first appears in Wo ...

''. He gave lessons to a number of pianists, including the great virtuoso Hans von Bülow

Freiherr Hans Guido von Bülow (; 8 January 1830 – 12 February 1894) was a German conductor, pianist, and composer of the Romantic era. As one of the most distinguished conductors of the 19th century, his activity was critical for establishi ...

, who married Liszt's daughter Cosima in 1857 (she would later marry Wagner). Liszt's work during this period made Weimar a nexus for modern music.

As kapellmeister Liszt was required to submit every programme to the court Intendant

An intendant (; ; ) was, and sometimes still is, a public official, especially in France, Spain, Portugal, and Latin America. The intendancy system was a centralizing administrative system developed in France. In the War of the Spanish Success ...

for prior approval. This did not cause large problems until the appointment of Franz von Dingelstedt

Franz von Dingelstedt (30 June 1814 – 15 May 1881) was a German poet, dramatist and theatre administrator.

Life and career

Dingestedt was born at Halsdorf, Hesse-Kassel (or Hesse-Cassel), Germany, and later studied at the University of Marbur ...

in 1857, who reduced the number of music productions, rejected Liszt's choices of repertoire, and even organised a demonstration against Liszt's 1858 premiere of . Faced with this opposition, Liszt resigned in 1858.

At first, after arriving in Weimar, Princess Carolyne lived apart from Liszt, in order to avoid suspicions of impropriety. She wished eventually to marry Liszt, but since her husband, Russian military officer Prince Nicholas von Sayn-Wittgenstein, was still alive, she had to convince the Roman Catholic authorities that her marriage to him had been invalid. Her appeal to the Archbishop of St Petersburg

Saint Petersburg, formerly known as Petrograd and later Leningrad, is the List of cities and towns in Russia by population, second-largest city in Russia after Moscow. It is situated on the Neva, River Neva, at the head of the Gulf of Finland ...

for an annulment

Annulment is a legal procedure within secular and religious legal systems for declaring a marriage null and void. Unlike divorce, it is usually retroactive, meaning that an annulled marriage is considered to be invalid from the beginning alm ...

, lodged before leaving Russia, was ultimately unsuccessful, and the couple abandoned pretence and began to live together in the autumn of 1848.

Nicholas was aware that the couple's marriage had effectively ended, and Carolyne and Nicholas reached an agreement to annul in 1850 whereby the prince would receive some of Carolyne's estates. However, this arrangement was struck down in 1851 by the consistory court

A consistory court is a type of ecclesiastical court, especially within the Church of England where they were originally established pursuant to a charter of King William the Conqueror, and still exist today, although since about the middle of th ...

of Zhytomyr

Zhytomyr ( ; see #Names, below for other names) is a city in the north of the western half of Ukraine. It is the Capital city, administrative center of Zhytomyr Oblast (Oblast, province), as well as the administrative center of the surrounding ...

. Throughout the decade the couple would continue to negotiate through the complex situation.

The New German School and the War of the Romantics

In 1859Franz Brendel

Karl Franz Brendel (26 November 1811 – 25 November 1868) was a German music critic, journalist and musicologist born in Stolberg, Saxony-Anhalt, Stolberg, the son of a successful mining engineer named :de:Christian Friedrich Brendel, Christian ...

coined the name "New German School

The New German School (, ) is a term introduced in 1859 by Franz Brendel, editor of the ''Neue Zeitschrift für Musik'', to describe certain trends in German music. Although the term has frequently been used in essays and books about music histo ...

" in his publication , to refer to the musicians associated with Liszt while he was in Weimar. The most prominent members other than Liszt were Wagner, though he rejected the label, and Berlioz. The group also included Peter Cornelius

Carl August Peter Cornelius (24 December 1824 – 26 October 1874) was a German composer, writer about music, poet and translator.

Life

He was born in Mainz to Carl Joseph Gerhard (1793–1843) and Friederike (1789–1867) Cornelius, actors in ...

, Hans von Bülow and Joachim Raff

Joseph Joachim Raff (27 May 182224 or 25 June 1882) was a German-Swiss composer, pedagogue and pianist.James Deaville'Raff, (Joseph) Joachim' in ''Grove Music Online'' (2001)

Biography

Raff was born in Lachen, Switzerland, Lachen in Switzerland. ...

. The School was a loose confederation of progressive composers, mainly grouped together as a challenge to supposed conservatives such as Mendelssohn and Brahms

Johannes Brahms (; ; 7 May 1833 – 3 April 1897) was a German composer, virtuoso pianist, and conductor of the mid- Romantic period. His music is noted for its rhythmic vitality and freer treatment of dissonance, often set within studied ye ...

, and so the term is considered to be of limited use in describing a particular movement or set of unified principles. What commonalities the composers had were around the development of programmatic music

Program music or programmatic music is a type of instrumental art music that attempts to musically render an extramusical narrative. The narrative itself might be offered to the audience through the piece's title, or in the form of program not ...

, harmonic experimentation, wide-ranging modulation and formal innovations such as the use of leitmotif

A leitmotif or () is a "short, recurring musical phrase" associated with a particular person, place, or idea. It is closely related to the musical concepts of ''idée fixe'' or ''motto-theme''. The spelling ''leitmotif'' is a partial angliciz ...

s and thematic transformation Thematic transformation (also known as thematic metamorphosis or thematic development) is a musical technique in which a leitmotif, or theme, is developed by changing the theme by using permutation ( transposition or modulation, inversion, and ret ...

.

The disagreements between the two factions is often described as the "War of the Romantics

The "War of the Romantics" is a term used by some music historians to describe the schism among prominent musicians in the second half of the 19th century. Musical structure, the limits of chromatic harmony, and program music versus absolute mu ...

". The "war" was largely carried out through articles, essays and reviews. Each side claimed Beethoven

Ludwig van Beethoven (baptised 17 December 177026 March 1827) was a German composer and pianist. He is one of the most revered figures in the history of Western music; his works rank among the most performed of the classical music repertoire ...

as its predecessor. A number of festivals were arranged to showcase the music of the New German School, notably in Leipzig in 1859 and Weimar in 1861. The Allgemeiner Deutscher Musikverein

The Allgemeiner Deutscher Musikverein (ADMV, "General German Music Association") was a German musical association founded in 1861 by Franz Liszt and Franz Brendel, to embody the musical ideals of the New German School of music.

Background

At th ...

, intrinsically linked to the School, was founded at this time, with Liszt becoming its honorary president in 1873. However, as most of Liszt's work from the 1860s and 1870s received little attention, and Brendel and Berlioz died in the late 1860s, the focus of the progressive movement in music moved to Bayreuth

Bayreuth ( or ; High Franconian German, Upper Franconian: Bareid, ) is a Town#Germany, town in northern Bavaria, Germany, on the Red Main river in a valley between the Franconian Jura and the Fichtel Mountains. The town's roots date back to 11 ...

with Wagner in the 1870s, who definitively moved on from the School and the .

Rome

After a visit to Rome and an audience with

After a visit to Rome and an audience with Pope Pius IX

Pope Pius IX (; born Giovanni Maria Battista Pietro Pellegrino Isidoro Mastai-Ferretti; 13 May 1792 – 7 February 1878) was head of the Catholic Church from 1846 to 1878. His reign of nearly 32 years is the longest verified of any pope in hist ...

in 1860, Carolyne finally secured an annulment. It was planned that she and Liszt would marry in Rome, on 22 October 1861, Liszt's 50th birthday. Liszt arrived in Rome on 21 October, but a Vatican official had arrived the previous day in order to stop the marriage. This was a result of the machinations of Cardinal Hohenlohe, who wanted to protect a complex inheritance agreement brokered by Tsar Alexander II

Alexander II ( rus, Алекса́ндр II Никола́евич, Aleksándr II Nikoláyevich, p=ɐlʲɪˈksandr ftɐˈroj nʲɪkɐˈlajɪvʲɪtɕ; 29 April 181813 March 1881) was Emperor of Russia, King of Poland and Grand Duke of Finland fro ...

. Carolyne subsequently gave up all attempts to marry Liszt, even after her husband's death in 1864; she became a recluse, working for the rest of her life on a long work critical of the Catholic Church.

The 1860s were a period of great sadness in Liszt's private life. On 13 December 1859, he lost his 20-year-old son Daniel to an unknown illness. On 11 September 1862 his 26-year-old daughter Blandine also died, having contracted sepsis

Sepsis is a potentially life-threatening condition that arises when the body's response to infection causes injury to its own tissues and organs.

This initial stage of sepsis is followed by suppression of the immune system. Common signs and s ...

after surgery on a breast growth which developed shortly after giving birth to a son she named in memory of Daniel. In letters to friends, Liszt announced that he would retreat to a solitary living.

He moved to the monastery , just outside Rome, where on 20 June 1863 he took up quarters in a small, spartan apartment. He had a piano in his cell, and he continued to compose. He had already joined the Third Order of Saint Francis

The Third Order of Saint Francis, or Franciscan Tertiaries, is the third order of the Franciscan tradition of Christianity, founded by the medieval Italian Catholic friar Francis of Assisi.

Francis founded the Third Order, originally called t ...

previously, on 23 June 1857. On 25 April 1865 he received the tonsure

Tonsure () is the practice of cutting or shaving some or all of the hair on the scalp as a sign of religious devotion or humility. The term originates from the Latin word ' (meaning "clipping" or "shearing") and referred to a specific practice in ...

at the hands of Cardinal Hohenlohe, who had previously worked against Carolyne's efforts to secure an annulment; the two men became close friends. On 31 July 1865 Liszt received the four minor orders of porter

Porter may refer to:

Companies

* Porter Airlines, Canadian airline based in Toronto

* Porter Chemical Company, a defunct U.S. toy manufacturer of chemistry sets

* Porter Motor Company, defunct U.S. car manufacturer

* H.K. Porter, Inc., a locom ...

, lector

Lector is Latin for one who reads, whether aloud or not. In modern languages it takes various forms, as either a development or a loan, such as , , and . It has various specialized uses.

Academic

The title ''lector'' may be applied to lecturers ...

, exorcist

In some religions, an exorcist (from the Greek „ἐξορκιστής“) is a person who is believed to be able to cast out the devil or performs the ridding of demons or other supernatural beings who are alleged to have possessed a person ...

and acolyte

An acolyte is an assistant or follower assisting the celebrant in a religious service or procession. In many Christian denominations, an acolyte is anyone performing ceremonial duties such as lighting altar candles. In others, the term is used f ...

. After this ordination he was often called " Liszt". On 14 August 1879, he was made an honorary canon

Canon or Canons may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* Canon (fiction), the material accepted as officially written by an author or an ascribed author

* Literary canon, an accepted body of works considered as high culture

** Western canon, th ...

of Albano.

In 1867 Liszt was commissioned to write a piece for the coronation ceremony of Franz Joseph

Franz Joseph I or Francis Joseph I ( ; ; 18 August 1830 – 21 November 1916) was Emperor of Austria, King of Hungary, and the ruler of the Grand title of the emperor of Austria, other states of the Habsburg monarchy from 1848 until his death ...

and Elisabeth of Bavaria

Elisabeth (born Duchess Elisabeth Amalie Eugenie in Bavaria; 24 December 1837 – 10 September 1898), nicknamed Sisi or Sissi, was Empress of Austria and Queen of Hungary from her marriage to Franz Joseph I of Austria on 24 April 1854 until h ...

, and he travelled to Budapest

Budapest is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns of Hungary, most populous city of Hungary. It is the List of cities in the European Union by population within city limits, tenth-largest city in the European Union by popul ...

to conduct it. The ''Hungarian Coronation Mass'' was performed on 8 June 1867, at the coronation ceremony in the Matthias Church

The Church of the Assumption of the Buda Castle (), more commonly known as the Matthias Church () and more rarely as the Coronation Church of Buda, is a Catholic church in Holy Trinity Square, Budapest, Hungary, in front of the Fisherman's Bastion ...

by Buda Castle

Buda Castle (, ), formerly also called the Royal Palace () and the Royal Castle (, ), is the historical castle and palace complex of the King of Hungary, Hungarian kings in Budapest. First completed in 1265, the Baroque architecture, Baroque pa ...

in a six-section form. After the first performance, the Offertory was added and, two years later, the Gradual.

"Tripartite existence"

Grand Duke Charles Alexander had been attempting to arrange Liszt's return to Weimar ever since he had left, and in January 1869 Liszt agreed to a residency to give masterclasses in piano playing. He was based in the Hofgärtnerei (court gardener's house), where he taught for the next seventeen years. From 1872 until the end of his life, Liszt made regular journeys between Rome, Weimar and Budapest, continuing what he called his ("tripartite

Tripartite means composed of or split into three parts, or refers to three parties. Specifically, it may also refer to any of the following:

* 3 (number)

* Tripartite alignment, in linguistics

* Tripartite motto, or hendiatris, a figure of speech ...

existence"). It is estimated that he travelled at least 4,000 miles a year during this period in his life – an exceptional figure given his advancing age and the rigors of road and rail in the 1870s.

Liszt's time in Budapest was the result of efforts from the Hungarian government in attracting him to work there. The plan of the foundation of the Royal Academy of Music

The Royal Academy of Music (RAM) in London, England, is one of the oldest music schools in the UK, founded in 1822 by John Fane and Nicolas-Charles Bochsa. It received its royal charter in 1830 from King George IV with the support of the firs ...

was agreed upon by the Hungarian Parliament in 1873, and in March 1875 Liszt was nominated its president. The academy was officially opened on 14 November 1875 with Liszt's colleague Ferenc Erkel

Ferenc Erkel ( , ; November 7, 1810June 15, 1893) was a Hungarian composer, conductor and pianist. He was the father of Hungarian grand opera, written mainly on historical themes, which are still often performed in Hungary. He also composed t ...

as director and Kornél Ábrányi

Kornél Ábrányi (; 15 October 1822 – 20 December 1903) was a Hungary, Hungarian pianist, music writer and music theory, theorist, and composer. He was born in Szentgyörgyábrány. A pupil of Frédéric Chopin, and a close friend of Franz Lisz ...

and Robert Volkmann

Friedrich Robert Volkmann (6 April 1815 – 30 October 1883) was a German composer.

Life

Robert Volkmann was born in Lommatzsch near Meißen in the Kingdom of Saxony. His father, a music director for a church, trained him in music to prepare him ...

on the staff. Liszt himself only arrived to deliver lessons in March 1876. From 1881 when in Budapest he would stay in an apartment in the Academy, where he taught pupils in much the same way as he did in Weimar. In 1925, the institution was renamed in honour of Liszt.

Final years

Liszt fell down a flight of stairs at the Hofgärtnerei in July 1881, and remained bedridden for several weeks after this accident. He had been in good health up to that point, but a number of ailments subsequently manifested, such as acataract

A cataract is a cloudy area in the lens (anatomy), lens of the eye that leads to a visual impairment, decrease in vision of the eye. Cataracts often develop slowly and can affect one or both eyes. Symptoms may include faded colours, blurry or ...

in the left eye, dental issues and fatigue. Since around 1877 he had become increasingly plagued by feelings of desolation, despair and preoccupation with death—feelings that he expressed in his works from this period. As he told Lina Ramann, "I carry a deep sadness of the heart which must now and then break out in sound."

On 13 January 1886, while Claude Debussy

Achille Claude Debussy (; 22 August 1862 – 25 March 1918) was a French composer. He is sometimes seen as the first Impressionism in music, Impressionist composer, although he vigorously rejected the term. He was among the most influe ...

was staying at the Villa Medici

The Villa Medici () is a sixteenth-century Italian Mannerist villa and an architectural complex with 7-hectare Italian garden, contiguous with the more extensive Borghese gardens, on the Pincian Hill next to Trinità dei Monti in the historic ...

in Rome, Liszt met him there with Paul Vidal

Paul Antonin Vidal (16 June 1863 – 9 April 1931) was a French composer, conductor and music teacher mainly active in Paris.Charlton D. Paul Vidal. In: ''The New Grove Dictionary of Opera.'' Macmillan, London and New York, 1997.

Life and caree ...

and Ernest Hébert

Antoine Auguste Ernest Hébert (; 3 November 1817 – 5 December 1908) was a French academic painter.

Biography

Hébert was born in Grenoble, son of a notary in Grenoble, and moved in 1835 to Paris to study law. He simultaneously took ar ...

, director of the French Academy. Liszt played "Au bord d'une source

''Au bord d'une source'' ("Beside a Spring") is a piano piece by Franz Liszt; it is the 4th piece of the first suite of '' Années de Pèlerinage'' ("Years of Pilgrimage").

There are three separate versions of ''Au bord d'une source''. The firs ...

" from '' Années de pèlerinage'', as well as his arrangement of Schubert's ''Ave Maria'' for the musicians. Debussy in later years described Liszt's pedalling as "like a form of breathing."

Liszt travelled to Bayreuth

Bayreuth ( or ; High Franconian German, Upper Franconian: Bareid, ) is a Town#Germany, town in northern Bavaria, Germany, on the Red Main river in a valley between the Franconian Jura and the Fichtel Mountains. The town's roots date back to 11 ...

in the summer of 1886. This was in order to support his daughter Cosima, who was running the festival

A festival is an event celebrated by a community and centering on some characteristic aspect or aspects of that community and its religion or cultures. It is often marked as a local or national holiday, Melā, mela, or Muslim holidays, eid. A ...

but struggling to generate sufficient interest. The festival was dedicated to the works of her husband Richard Wagner, and had opened ten years previously; Wagner had died in 1883. Already frail, in his final week of life Liszt's health deteriorated further, as he experienced a fever, cough and delirium.

He died during the festival, near midnight on 31 July 1886, at the age of 74officially as a result of pneumonia

Pneumonia is an Inflammation, inflammatory condition of the lung primarily affecting the small air sacs known as Pulmonary alveolus, alveoli. Symptoms typically include some combination of Cough#Classification, productive or dry cough, ches ...

, which he had contracted prior to arriving in Bayreuth, although the true cause of death may have been a heart attack

A myocardial infarction (MI), commonly known as a heart attack, occurs when Ischemia, blood flow decreases or stops in one of the coronary arteries of the heart, causing infarction (tissue death) to the heart muscle. The most common symptom ...

. He was buried on 3 August 1886, in the , according to Cosima's wishes; despite controversy over this as his final resting place, Liszt's body was never moved.

Relationships with other composers

Hector Berlioz

Berlioz

Louis-Hector Berlioz (11 December 1803 – 8 March 1869) was a French Romantic music, Romantic composer and conductor. His output includes orchestral works such as the ''Symphonie fantastique'' and ''Harold en Italie, Harold in Italy'' ...

and Liszt first met on 4 December 1830, the day before the premiere of Berlioz's ''Symphonie fantastique

' (''Fantastic Symphony: Episode in the Life of an Artist … in Five Sections'') Opus number, Op. 14, is a program music, programmatic symphony written by Hector Berlioz in 1830. The first performance was at the Paris Conservatoire on 5 December ...

''. The two quickly became very close friends, exchanging intimate letters on their respective love lives, which also reveal that Liszt was aware of Berlioz's fixation on suicide. Liszt acted as a witness at Berlioz's wedding to Harriet Smithson in 1833, despite cautioning Berlioz against it, and they worked together at several concerts over the following three years, and again in 1841 and 1844. In Weimar, the two composers revised ''Benvenuto Cellini

Benvenuto Cellini (, ; 3 November 150013 February 1571) was an Italian goldsmith, sculptor, and author. His best-known extant works include the ''Cellini Salt Cellar'', the sculpture of ''Perseus with the Head of Medusa'', and his autobiography ...

'', and Liszt organised a "Berlioz Week." It included ''Roméo et Juliette

''Roméo et Juliette'' (, ''Romeo and Juliet'') is an opera in five acts by Charles Gounod to a French libretto by Jules Barbier and Michel Carré, based on ''Romeo and Juliet'' by William Shakespeare. It was first performed at the Théâtre Ly ...

'' and part of ''La damnation de Faust

''La Damnation de Faust'' (English: ''The Damnation of Faust''), Op. 24 is a French musical composition for four solo voices, full seven-part chorus, large children's chorus and orchestra by the French composer Hector Berlioz. He called it a ' ...

'', which was later dedicated to Liszt. In return, Liszt dedicated his ''Faust Symphony

''A Faust Symphony in three character pictures'' (), List of compositions by Franz Liszt (S.1 - S.350), S.108, or simply the "''Faust Symphony''", is a choral symphony written by Hungarians, Hungarian composer Franz Liszt inspired by Johann Wolfga ...

'' to Berlioz.

The orchestration of Berlioz had an influence on Liszt, especially with regards to his symphonic poems. Berlioz saw orchestration as part of the compositional process, rather than a final task to undertake after the music had already been written. Berlioz joined Liszt and Wagner as a figurehead of the New German School

The New German School (, ) is a term introduced in 1859 by Franz Brendel, editor of the ''Neue Zeitschrift für Musik'', to describe certain trends in German music. Although the term has frequently been used in essays and books about music histo ...

, but an unwilling one, as he was unconvinced by Wagner's ideas about the "music of the future

"Music of the Future" ("") is the title of an essay by Richard Wagner, first published in French translation in 1860 as "La musique de l'avenir" and published in the original German in 1861. It was intended to introduce the librettos of Wagner's o ...

".

Frédéric Chopin

Chopin and Liszt first met in the early 1830s, both moving in the same circles of artists residing in Paris. Liszt attended Chopin's first Paris performance at theSalle Pleyel

The Salle Pleyel (, meaning "Pleyel Hall") is a concert hall in the 8th arrondissement of Paris, France, designed by the acoustician Gustave Lyon together with the architect Jacques Marcel Auburtin, who died in 1926, and the work was completed i ...

on 26 February 1832, which he admired greatly, and by mid-1833 the two had become close friends. They performed together a number of times, often for charity, and since Chopin only performed in public about 12 times, these events comprise a large proportion of his total appearances.

Their relationship cooled in the early 1840s, and several reasons have been suggested for this, including that Marie d'Agoult

Marie Catherine Sophie, Comtesse d'Agoult (born de Flavigny; 31 December 18055 March 1876), was a French romanticism, romantic author and historian, known also by her pen name, Daniel Stern.

Life

Marie was born in Frankfurt am Main, Germany, w ...

was infatuated with Chopin, or Liszt with Aurore Dupin

Amantine Lucile Aurore Dupin de Francueil (; 1 July 1804 – 8 June 1876), best known by her pen name George Sand (), was a French novelist, memoirist and journalist. Being more renowned than either Victor Hugo or Honoré de Balz ...

, also known by her pen name George Sand

Amantine Lucile Aurore Dupin de Francueil (; 1 July 1804 – 8 June 1876), best known by her pen name George Sand (), was a French novelist, memoirist and journalist. Being more renowned than either Victor Hugo or Honoré de Balz ...

, or that Liszt used Chopin's home for a rendezvous with Marie Pleyel

Marie-Félicité-Denise Pleyel (née Moke; 4 July or 4 September 1811 – 30 March 1875) was a Belgian concert pianist.

Early life

With a father from Torhout in Flemish-speaking Belgium who was a language teacher, and a German mother who ran ...

, the wife of Chopin's friend Camille. The two musicians had very different personalities, with Liszt being extroverted and outgoing while Chopin was more introverted and reflective, so it is possible that the two never had an extremely close friendship to begin with, and the fact that they did not live physically close together would have been another barrier. On the topic, Liszt commented to Chopin's biographer Frederick Niecks

Frederick Niecks (3 February 184524 June 1924) was a German musical scholar and author who resided in Scotland for most of his life. He is best remembered for his biographies of Frédéric Chopin and Robert Schumann.

Biography

Friedrich Mater ...

that Marie d'Agoult and Aurore Dupin had frequently disagreed, and the musicians had felt obliged to side with their respective partners. Alex Szilasi suggests that Chopin took offence at an equivocal 1841 review by Liszt, and was perhaps jealous of Liszt's popularity, while Liszt in turn may have been jealous of Chopin's reputation as a serious composer.

Very shortly after Chopin's death in 1849, Liszt had a monument erected in his memory and began to write a biography. Chopin's relatives and friends found the timing of this insensitive, and many declined to help with Liszt's enquiries.

Scholars disagree on the extent to which Chopin and Liszt influenced each others' compositions. Charles Rosen

Charles Welles Rosen (May 5, 1927December 9, 2012) was an American pianist and writer on music. He is remembered for his career as a concert pianist, for his recordings, and for his many writings, notable among them the book '' The Classical St ...

identifies similarities between Chopin's Étude Op. 10, No. 9 and the early version of Liszt's Transcendental Étude No. 10, but Alan Walker

Alan Olav Walker (born 24 August 1997) is a Norwegian DJ and record producer. His songs "Faded (Alan Walker song), Faded", "Sing Me to Sleep", "Alone (Alan Walker song), Alone", "All Falls Down (Alan Walker song), All Falls Down" (with Noah Cy ...

argues that no such connection exists. Stylistic similarities between other studies, Chopin's ''Nocturnes

A nocturne is a musical composition that is inspired by, or evocative of, the night.

History

The term ''nocturne'' (from French '' nocturne'' "of the night") was first applied to musical pieces in the 18th century, when it indicated an ensembl ...

'' and Liszt's '' Consolations'', and even an influence on the ornamentation and fingering of Liszt's works, have been proposed.

Robert and Clara Schumann

In 1837 Liszt wrote a positive review ofRobert Schumann

Robert Schumann (; ; 8 June 181029 July 1856) was a German composer, pianist, and music critic of the early Romantic music, Romantic era. He composed in all the main musical genres of the time, writing for solo piano, voice and piano, chamber ...

's ''Impromptus'' and piano sonatas no. 1 and no. 3. The two began to correspond, and the following year he met Schumann's fiancée Clara Wieck

Clara Josephine Schumann (; ; née Wieck; 13 September 1819 – 20 May 1896) was a German pianist, composer, and piano teacher. Regarded as one of the most distinguished pianists of the Romantic era, she exerted her influence over the course o ...

, to whom he dedicated the early version of '' Grandes études de Paganini''. Schumann in turn dedicated '' Fantasie in C'' to Liszt. The two met for the first time in Dresden

Dresden (; ; Upper Saxon German, Upper Saxon: ''Dräsdn''; , ) is the capital city of the States of Germany, German state of Saxony and its second most populous city after Leipzig. It is the List of cities in Germany by population, 12th most p ...

in 1840.

Schumann resigned as editor of the music journal ''Neue Zeitschrift für Musik

The New Journal of Music (, and abbreviated to NZM) is a music magazine, co-founded in Leipzig by Robert Schumann, his teacher and future father-in law Friedrich Wieck, Julius Knorr and his close friend Ludwig Schuncke. Its first issue appe ...

'' in 1844, ten years after founding it. The journal was taken over the following year by Franz Brendel

Karl Franz Brendel (26 November 1811 – 25 November 1868) was a German music critic, journalist and musicologist born in Stolberg, Saxony-Anhalt, Stolberg, the son of a successful mining engineer named :de:Christian Friedrich Brendel, Christian ...

, who used it to publicise and support Liszt's New German School, to Schumann's chagrin. In 1848 Liszt attended a performance of the Piano Trio No. 1 being held in his honour in the Schumanns' home. Liszt arrived two hours late with Wagner (who had not been invited), derided the piece, and spoke ill of the recently deceased Mendelssohn

Jakob Ludwig Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy (3 February 18094 November 1847), widely known as Felix Mendelssohn, was a German composer, pianist, organist and conductor of the early Romantic period. Mendelssohn's compositions include symphonie ...

. This upset the Schumanns, and Robert physically assaulted Liszt.

The relationship between Liszt and the couple remained frosty. Liszt dedicated his 1854 piano sonata to Robert, who had by that point been committed to a mental institution in Endenich. Clara asked for Liszt's help that year in finding a performance venue in order to earn an income. Liszt arranged an all-Schumann concert with Clara as the star performer and published an extremely positive review, but Clara did not express any gratitude. In a posthumous edition of Robert's works, Clara changed the dedication of the ''Fantasie'' from Liszt to herself. After Liszt's death, she wrote in her diary "He was an eminent keyboard virtuoso but a dangerous example for the young.... As a composer he was terrible."

Richard Wagner

Wagner

Wilhelm Richard Wagner ( ; ; 22 May 181313 February 1883) was a German composer, theatre director, essayist, and conductor who is chiefly known for his operas (or, as some of his mature works were later known, "music dramas"). Unlike most o ...

first met Liszt in Paris in 1841, while living in poverty after fleeing Riga

Riga ( ) is the capital, Primate city, primate, and List of cities and towns in Latvia, largest city of Latvia. Home to 591,882 inhabitants (as of 2025), the city accounts for a third of Latvia's total population. The population of Riga Planni ...

to escape creditors. Liszt was at this point a famous pianist, whereas Wagner was unknown; unlike Wagner, Liszt did not remember the meeting. In 1844 Liszt attended a performance of Wagner's first major success, the opera ''Rienzi

' (''Rienzi, the last of the tribunes''; WWV 49) is an 1842 opera by Richard Wagner in five acts, with the libretto written by the composer after Edward Bulwer-Lytton's novel of the same name (1835). The title is commonly shortened to ''Rienzi' ...

'', in Dresden. The two met in Berlin at the instigation of Wilhelmine Schröder-Devrient

Wilhelmine Schröder-Devrient ( Schröder; 6 December 180426 January 1860), was a German operatic soprano. As a singer, she combined a rare quality of tone with dramatic intensity of expression, which was as remarkable on the concert platform as ...

, and Wagner later sent Liszt the scores of ''Rienzi'' and ''Tannhäuser

Tannhäuser (; ), often stylized "The Tannhäuser", was a German Minnesinger and traveling poet. Historically, his biography, including the dates he lived, is obscure beyond the poetry, which suggests he lived between 1245 and 1265.

His name ...

'' in an attempt to elicit approval. Liszt settled in Weimar in 1848, and the two grew close, Wagner still being located in Dresden. Wagner wrote to Liszt a number of times soliciting financial help.

In 1849 Liszt sheltered Wagner after the latter's involvement in the failed May Uprising in Dresden

The May Uprising took place in Dresden, Kingdom of Saxony in 1849; it was one of the last of the series of events known as the Revolutions of 1848.

Events leading to the May Uprising

In the German states, revolutions began in March 1848, start ...

. Liszt arranged a false passport and lent Wagner money to allow him to escape Germany for Switzerland, and for the next ten years continued to send money and visit, as well as petition officials for a pardon which eventually came in 1860.

To publicise Wagner's music, Liszt staged ''Tannhäuser'' in 1849, for the first time outside Dresden, and published two transcriptions from it, writing to Wagner "Once and for all, number me in future among your most zealous and devoted admirers; near or far, count on me and make use of me." In 1850 he arranged the premiere of ''Lohengrin

Lohengrin () is a character in German Arthurian literature. The son of Parzival (Percival), he is a knight of the Holy Grail sent in a boat pulled by swans to rescue a maiden who can never ask his identity. His story, which first appears in Wo ...

'', which Wagner dedicated to Liszt, and he also mounted performances of ''Der fliegende Holländer

' (''The Flying Dutchman''), Wagner-Werk-Verzeichnis, WWV 63, is a German-language opera, with libretto and music by Richard Wagner. The central theme is redemption through love. Wagner Conducting, conducted the premiere at the Königliches Hofthe ...

''. Liszt had intended to dedicate the 1857 ''Dante Symphony

''A Symphony to Dante's Divine Comedy'', S.109, or simply the "''Dante Symphony''", is a choral symphony composed by Franz Liszt. Written in the high romantic style, it is based on Dante Alighieri's journey through Hell and Purgatory, as depicted ...

'' to Wagner, but upon being told this Wagner replied that, while a fine piece, he would prefer to receive money. Liszt was offended by this comment, and did not publish the dedication.

By 1864 Wagner had begun an affair with Liszt's daughter Cosima, who was married to Liszt's erstwhile pupil Hans von Bülow