Le Règne Animal on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Le Règne Animal'' () is the most famous work of the French

*''Le Règne Animal distribué d'après son organisation, pour servir de base à l'histoire naturelle des animaux et d'introduction à l'anatomie comparée'' (1st edition, 4 volumes, 1816) (Volumes I, II and IV by Cuvier; Volume III by

*''Le Règne Animal distribué d'après son organisation, pour servir de base à l'histoire naturelle des animaux et d'introduction à l'anatomie comparée'' (1st edition, 4 volumes, 1816) (Volumes I, II and IV by Cuvier; Volume III by

Each section, such as on reptiles at the start of Volume II (and the entire work) is introduced with an essay on distinguishing aspects of their zoology. In the case of the reptiles, the essay begins with the observation that their circulation is so arranged that only part of the blood pumped by the heart goes through the lungs; Cuvier discusses the implications of this arrangement, next observing that they have a relatively small brain compared to the mammals and birds, and that none of them incubate their eggs.

Next, Cuvier identifies the taxonomic divisions of the group, in this case four orders of reptiles, the chelonians (

Each section, such as on reptiles at the start of Volume II (and the entire work) is introduced with an essay on distinguishing aspects of their zoology. In the case of the reptiles, the essay begins with the observation that their circulation is so arranged that only part of the blood pumped by the heart goes through the lungs; Cuvier discusses the implications of this arrangement, next observing that they have a relatively small brain compared to the mammals and birds, and that none of them incubate their eggs.

Next, Cuvier identifies the taxonomic divisions of the group, in this case four orders of reptiles, the chelonians (

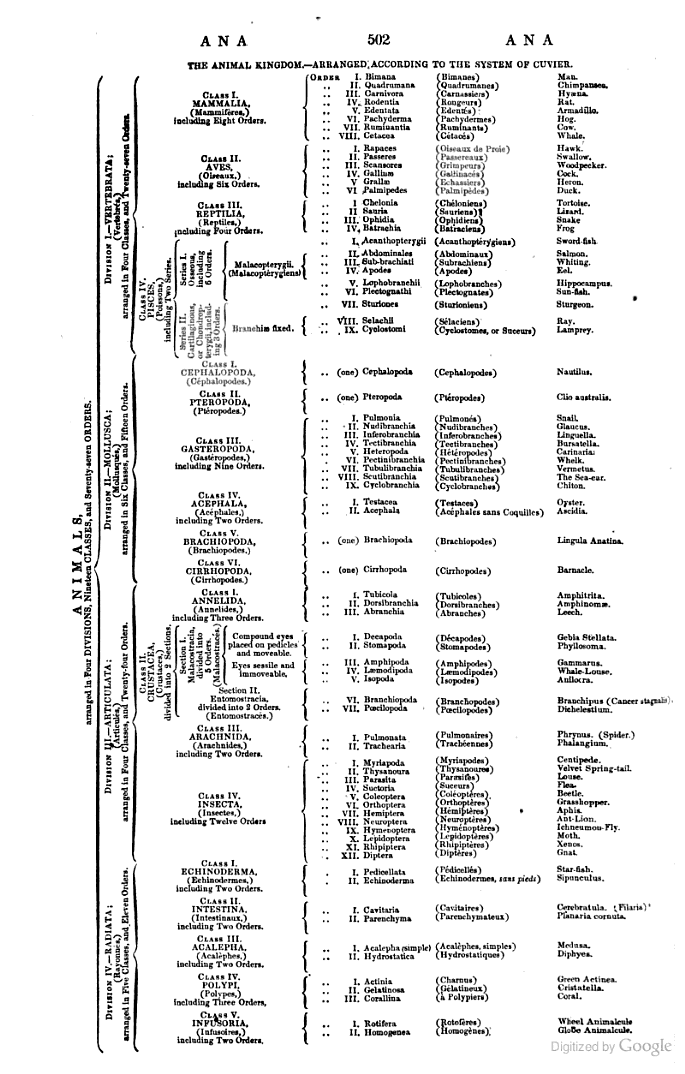

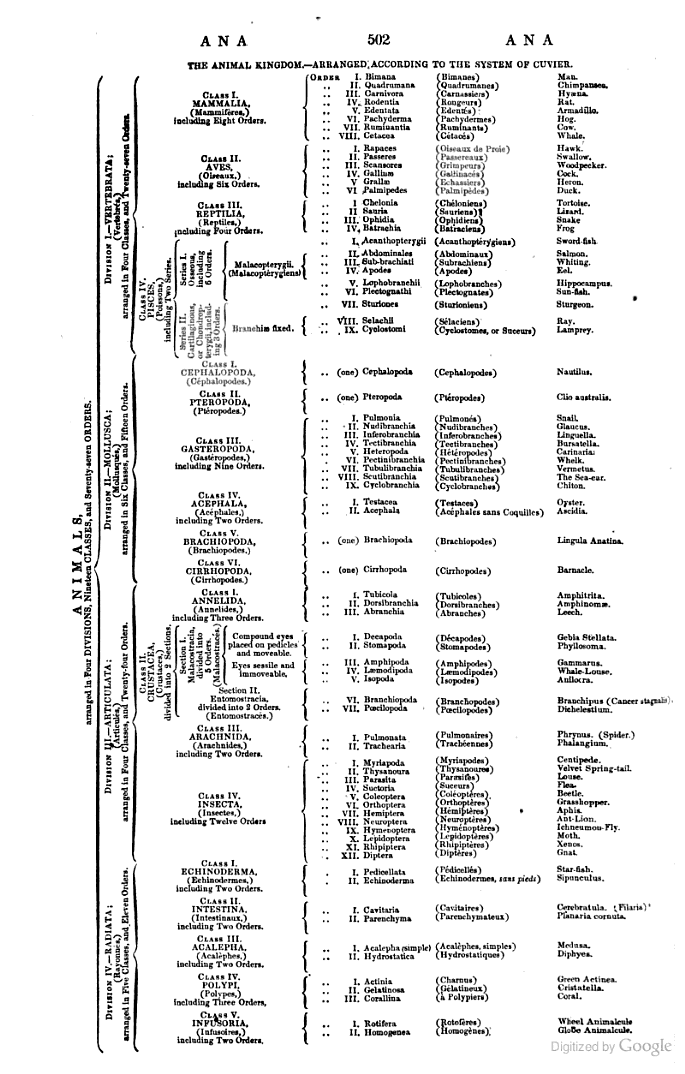

The classification adopted by Cuvier to define the natural structure of the animal kingdom, including both living and fossil forms, was as follows, the list forming the structure of the ''Règne Animal''. Where Cuvier's group names correspond (more or less) to modern taxa, these are named, in English if possible, in parentheses. The table from the 1828 ''

The classification adopted by Cuvier to define the natural structure of the animal kingdom, including both living and fossil forms, was as follows, the list forming the structure of the ''Règne Animal''. Where Cuvier's group names correspond (more or less) to modern taxa, these are named, in English if possible, in parentheses. The table from the 1828 ''

The entomologist William Sharp Macleay, in his 1821 book ''Horae Entomologicae'' which put forward the short-lived " Quinarian" system of classification into 5 groups, each of 5 subgroups, etc., asserted that in the ''Règne Animal'' "Cuvier was notoriously deficient in the power of legitimate and intuitive generalization in arranging the animal series". The zoologist

The entomologist William Sharp Macleay, in his 1821 book ''Horae Entomologicae'' which put forward the short-lived " Quinarian" system of classification into 5 groups, each of 5 subgroups, etc., asserted that in the ''Règne Animal'' "Cuvier was notoriously deficient in the power of legitimate and intuitive generalization in arranging the animal series". The zoologist

Le Règne Animal Distribué d'après son Organisation, pour Servir de Base à l'Histoire Naturelle des Animaux et d'Introduction à l'Anatomie Comparée

'. Déterville libraire, Imprimerie de A. Belin, Paris, 4 Volumes, 1816.

Volume I

(introduction, mammals, birds)

Volume II

(reptiles, fish, molluscs, annelids)

Volume III

(crustaceans, arachnids, insects)

Volume IV

(zoophytes; tables, plates) {{DEFAULTSORT:Regne Animal 1816 non-fiction books Natural history books Zoology books

naturalist

Natural history is a domain of inquiry involving organisms, including animals, fungi, and plants, in their natural environment, leaning more towards observational than experimental methods of study. A person who studies natural history is cal ...

Georges Cuvier

Jean Léopold Nicolas Frédéric, baron Cuvier (23 August 1769 – 13 May 1832), known as Georges Cuvier (; ), was a French natural history, naturalist and zoology, zoologist, sometimes referred to as the "founding father of paleontology". Cuv ...

. It sets out to describe the natural structure of the whole of the animal kingdom based on comparative anatomy

Comparative anatomy is the study of similarities and differences in the anatomy of different species. It is closely related to evolutionary biology and phylogeny (the evolution of species).

The science began in the classical era, continuing in t ...

, and its natural history

Natural history is a domain of inquiry involving organisms, including animals, fungi, and plants, in their natural environment, leaning more towards observational than experimental methods of study. A person who studies natural history is cal ...

. Cuvier divided the animals into four ''embranchements'' ("Branches", roughly corresponding to phyla), namely vertebrates, molluscs, articulated animals (arthropods and annelids), and zoophytes (cnidaria and other phyla).

The work appeared in four octavo volumes in December 1816 (although it has "1817" on the title pages); a second edition in five volumes was brought out in 1829–1830 and a third, written by twelve "disciples" of Cuvier, in 1836–1849. In this classic work, Cuvier presented the results of his life's research into the structure of living and fossil animals. With the exception of the section on insect

Insects (from Latin ') are Hexapoda, hexapod invertebrates of the class (biology), class Insecta. They are the largest group within the arthropod phylum. Insects have a chitinous exoskeleton, a three-part body (Insect morphology#Head, head, ...

s, in which he was assisted by his friend Pierre André Latreille

Pierre André Latreille (; 29 November 1762 – 6 February 1833) was a French zoology, zoologist, specialising in arthropods. Having trained as a Roman Catholic priest before the French Revolution, Latreille was imprisoned, and only regained hi ...

, the whole of the work was his own. It was translated into English many times, often with substantial notes and supplementary material updating the book in accordance with the expansion of knowledge. It was also translated into German, Italian and other languages, and abridged in versions for children.

''Le Règne Animal'' was influential in being widely read, and in presenting accurate descriptions of groups of related animals, such as the living elephants

Elephants are the Largest and heaviest animals, largest living land animals. Three living species are currently recognised: the African bush elephant (''Loxodonta africana''), the African forest elephant (''L. cyclotis''), and the Asian ele ...

and the extinct mammoths

A mammoth is any species of the extinct elephantid genus ''Mammuthus.'' They lived from the late Miocene epoch (from around 6.2 million years ago) into the Holocene until about 4,000 years ago, with mammoth species at various times inhabi ...

, providing convincing evidence for evolution

Evolution is the change in the heritable Phenotypic trait, characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. It occurs when evolutionary processes such as natural selection and genetic drift act on genetic variation, re ...

ary change to readers including Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English Natural history#Before 1900, naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all speci ...

, although Cuvier himself rejected the possibility of evolution.

Context

As a boy,Georges Cuvier

Jean Léopold Nicolas Frédéric, baron Cuvier (23 August 1769 – 13 May 1832), known as Georges Cuvier (; ), was a French natural history, naturalist and zoology, zoologist, sometimes referred to as the "founding father of paleontology". Cuv ...

(1769-1832) read the Comte de Buffon

Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon (; 7 September 1707 – 16 April 1788) was a French naturalist, mathematician, and cosmologist. He held the position of ''intendant'' (director) at the ''Jardin du Roi'', now called the Jardin des plant ...

's ''Histoire Naturelle

The ''Histoire Naturelle, générale et particulière, avec la description du Cabinet du Roi'' (; ) is an encyclopaedic collection of 36 large (quarto) volumes written between 1749–1804, initially by the Georges-Louis Leclerc de Buffon, Comte ...

'' from the previous century, as well as Linnaeus

Carl Linnaeus (23 May 1707 – 10 January 1778), also known after ennoblement in 1761 as Carl von Linné,#Blunt, Blunt (2004), p. 171. was a Swedish biologist and physician who formalised binomial nomenclature, the modern system of naming o ...

and Fabricius. He was brought to Paris by Étienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire

Étienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire (; 15 April 177219 June 1844) was a French naturalist who established the principle of "unity of composition". He was a colleague of Jean-Baptiste Lamarck and expanded and defended Lamarck's evolutionary theorie ...

in 1795, not long after the French Revolution. He soon became a professor of animal anatomy

Anatomy () is the branch of morphology concerned with the study of the internal structure of organisms and their parts. Anatomy is a branch of natural science that deals with the structural organization of living things. It is an old scien ...

at the Musée National d'Histoire Naturelle, surviving changes of government from revolutionary to Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte (born Napoleone di Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French general and statesman who rose to prominence during the French Revolution and led Military career ...

ic to monarchy. Essentially on his own he created the discipline of vertebrate palaeontology and the accompanying comparative method. He demonstrated that animals had become extinct

Extinction is the termination of an organism by the death of its Endling, last member. A taxon may become Functional extinction, functionally extinct before the death of its last member if it loses the capacity to Reproduction, reproduce and ...

.

In an earlier attempt to improve the classification of animals, Cuvier transferred the concepts of Antoine-Laurent de Jussieu

Antoine Laurent de Jussieu (; 12 April 1748 – 17 September 1836) was a French botanist, notable as the first to publish a natural classification of flowering plants; much of his system remains in use today. His classification was based on an e ...

's (1748-1836) method of natural classification, which had been presented in 1789 in ''Genera plantarum'', from botany

Botany, also called plant science, is the branch of natural science and biology studying plants, especially Plant anatomy, their anatomy, Plant taxonomy, taxonomy, and Plant ecology, ecology. A botanist or plant scientist is a scientist who s ...

to zoology

Zoology ( , ) is the scientific study of animals. Its studies include the anatomy, structure, embryology, Biological classification, classification, Ethology, habits, and distribution of all animals, both living and extinction, extinct, and ...

. In 1795, from a "fixist" perspective (denying the possibility of evolution

Evolution is the change in the heritable Phenotypic trait, characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. It occurs when evolutionary processes such as natural selection and genetic drift act on genetic variation, re ...

), Cuvier divided Linnaeus

Carl Linnaeus (23 May 1707 – 10 January 1778), also known after ennoblement in 1761 as Carl von Linné,#Blunt, Blunt (2004), p. 171. was a Swedish biologist and physician who formalised binomial nomenclature, the modern system of naming o ...

's two unsatisfactory classes ("insects" and "worms") into six classes of "white-blooded animals" or invertebrate

Invertebrates are animals that neither develop nor retain a vertebral column (commonly known as a ''spine'' or ''backbone''), which evolved from the notochord. It is a paraphyletic grouping including all animals excluding the chordata, chordate s ...

s: molluscs, crustaceans, insects and worms (differently understood), echinoderms and zoophytes. Cuvier divided the molluscs into three orders: cephalopods, gastropods and acephala. Still not satisfied, he continued to work on animal classification, culminating over twenty years later in the ''Règne Animal''.

For the ''Règne Animal'', using evidence from comparative anatomy and palaeontology

Paleontology, also spelled as palaeontology or palæontology, is the scientific study of the life of the past, mainly but not exclusively through the study of fossils. Paleontologists use fossils as a means to classify organisms, measure geo ...

—including his own observations—Cuvier divided the animal kingdom into four principal body plan

A body plan, (), or ground plan is a set of morphology (biology), morphological phenotypic trait, features common to many members of a phylum of animals. The vertebrates share one body plan, while invertebrates have many.

This term, usually app ...

s. Taking the central nervous system

The central nervous system (CNS) is the part of the nervous system consisting primarily of the brain, spinal cord and retina. The CNS is so named because the brain integrates the received information and coordinates and influences the activity o ...

as an animal's principal organ system which controlled all the other organ systems such as the circulatory and digestive systems, Cuvier distinguished four types of organisation of an animal's body:

* I. with a brain and a spinal cord (surrounded by parts of the skeleton)

* II. with organs linked by nerve fibres

* III. with two longitudinal, ventral nerve cords linked by a band with two ganglia positioned below the oesophagus

* IV. with a diffuse nervous system which is not clearly discernible

Grouping animals with these body plans resulted in four "embranchements" or branches (vertebrates, molluscs, the articulata that he claimed were natural (arguing that insects and annelid worms were related) and zoophytes (radiata

Radiata or Radiates is a historical taxonomic rank that was used to classify animals with Symmetry (biology)#Radial symmetry, radially symmetric body plans. The term Radiata is no longer accepted, as it united several different groupings of anim ...

)). This effectively broke with the mediaeval notion of the continuity of the living world in the form of the great chain of being

The great chain of being is a hierarchical structure of all matter and life, thought by medieval Christianity to have been decreed by God. The chain begins with God and descends through angels, Human, humans, Animal, animals and Plant, plants to ...

. It also set him in opposition to both Saint-Hilaire and Jean-Baptiste Lamarck

Jean-Baptiste Pierre Antoine de Monet, chevalier de Lamarck (1 August 1744 – 18 December 1829), often known simply as Lamarck (; ), was a French naturalist, biologist, academic, and soldier. He was an early proponent of the idea that biologi ...

. Lamarck claimed that species could transform through the influence of the environment, while Saint-Hilaire argued in 1820 that two of Cuvier's branches, the molluscs and radiata, could be united via various features, while the other two, articulata and vertebrates, similarly had parallels with each other. Then in 1830, Saint-Hilaire argued that these two groups could themselves be related, implying a single form of life from which all others could have evolved, and that Cuvier's four body plans were not fundamental.

Book

Editions

Pierre André Latreille

Pierre André Latreille (; 29 November 1762 – 6 February 1833) was a French zoology, zoologist, specialising in arthropods. Having trained as a Roman Catholic priest before the French Revolution, Latreille was imprisoned, and only regained hi ...

)

* --- (2nd edition, 5 volumes, 1829–1830)

* --- (3rd edition, 22 volumes, 1836–1849) known as the "Disciples edition"

The twelve "disciples" who contributed to the 3rd edition were Jean Victor Audouin (insects), Gerard Paul Deshayes (molluscs), Alcide d'Orbigny

Alcide Charles Victor Marie Dessalines d'Orbigny (6 September 1802 – 30 June 1857) was a French naturalist who made major contributions in many areas, including zoology (including malacology), palaeontology, geology, archaeology and anthropol ...

(birds), Antoine Louis Dugès (arachnids), Georges Louis Duvernoy (reptiles), Charles Léopold Laurillard (mammals in part), Henri Milne Edwards (crustaceans, annelids, zoophytes, and mammals in part), Francois Desire Roulin (mammals in part), Achille Valenciennes

Achille Valenciennes (9 August 1794 – 13 April 1865) was a French zoology, zoologist.

Valenciennes was born in Paris, and studied under Georges Cuvier. His study of parasitic worms in humans made an important contribution to the study of parasi ...

(fishes), Louis Michel François Doyère

Louis Michel François Doyère (born 28 January 1811 in Saint-Michel-des-Essartiers, Calvados; died 12 July 1863 in Bastia, Corsica) was a French zoologist and agronomist.

He was among the first zoologists to study tardigrades, describing speci ...

(insects), Charles Émile Blanchard (insects, zoophytes) and Jean Louis Armand de Quatrefages de Bréau (annelids, arachnids etc.).

The work was illustrated with tables and plates (at the end of Volume IV) covering only some of the species mentioned. A much larger set of illustrations, said by Cuvier to be "as accurate as they were elegant" was published by the entomologist Félix Édouard Guérin-Méneville

Félix Édouard Guérin-Méneville, also known as F. E. Guerin, (12 October 1799, in Toulon – 26 January 1874, in Paris) was a French entomologist.

Life and work

Guérin-Méneville changed his surname from Guérin in 1836. He was the author o ...

in his ''Iconographie du Règne Animal de G. Cuvier'', the nine volumes appearing between 1829 and 1844. The 448 quarto plates by Christophe Annedouche, Canu, Eugène Giraud, Lagesse, Lebrun, Vittore Pedretti, Plée and Smith illustrated some 6200 animals.

Translations

''Le Règne Animal'' was translated into languages including English, German and Italian. Many English translations and abridged versions were published and reprinted in the nineteenth century; records may be for the entire work or individual volumes, which were not necessarily dated, while old translations were often brought out in "new" editions by other publishers, making for a complex publication history. A translation by Edward Griffith (with assistance by Edward Pidgeon for some volumes and other specialists for other volumes) was published in 44 parts by G.B. Whittaker and partners from 1824 to 1835 and many times reprinted (up to 2012 and eBook format); another by G. Henderson in 1834–1837. A translation was made and published by the ornithologist William MacGillivray in Edinburgh in 1839–1840. Another version byEdward Blyth

Edward Blyth (23 December 1810 – 27 December 1873) was an English zoologist who worked for most of his life in India as a curator of zoology at the Asiatic Society, Royal Asiatic Society of Bengal in Calcutta.

He set about updating the museum ...

and others was published by William S. Orr and Co. in 1840. An abridged version by an "experienced teacher" was published by Longman, Brown, Green and Longman in London, and by Stephen Knapp in Coventry, in 1844. Kraus published an edition in New York in 1969. Other editions were brought out by H.G. Bohn in 1851 and W. Orr in 1854. An "easy introduction to the study of the animal kingdom: according to the natural method of Cuvier", together with examination questions on each chapter, was made by Annie Roberts and published in the 1850s by Thomas Varty.

A German translation by H.R. Schinz was published by J.S. Cotta in 1821–1825; another was made by Friedrich Siegmund Voigt and published by Brockhaus.

An Italian translation by G. de Cristofori was published by Stamperia Carmignani in 1832.

A Hungarian translation by Peter Vajda was brought out in 1841.

Approach

Each section, such as on reptiles at the start of Volume II (and the entire work) is introduced with an essay on distinguishing aspects of their zoology. In the case of the reptiles, the essay begins with the observation that their circulation is so arranged that only part of the blood pumped by the heart goes through the lungs; Cuvier discusses the implications of this arrangement, next observing that they have a relatively small brain compared to the mammals and birds, and that none of them incubate their eggs.

Next, Cuvier identifies the taxonomic divisions of the group, in this case four orders of reptiles, the chelonians (

Each section, such as on reptiles at the start of Volume II (and the entire work) is introduced with an essay on distinguishing aspects of their zoology. In the case of the reptiles, the essay begins with the observation that their circulation is so arranged that only part of the blood pumped by the heart goes through the lungs; Cuvier discusses the implications of this arrangement, next observing that they have a relatively small brain compared to the mammals and birds, and that none of them incubate their eggs.

Next, Cuvier identifies the taxonomic divisions of the group, in this case four orders of reptiles, the chelonians (tortoises

Tortoises ( ) are reptiles of the family Testudinidae of the order Testudines (Latin for "tortoise"). Like other turtles, tortoises have a turtle shell, shell to protect from predation and other threats. The shell in tortoises is generally hard ...

and turtles), saurians (lizards

Lizard is the common name used for all squamate reptiles other than snakes (and to a lesser extent amphisbaenians), encompassing over 7,000 species, ranging across all continents except Antarctica, as well as most oceanic island chains. The ...

), ophidians (snakes

Snakes are elongated Limbless vertebrate, limbless reptiles of the suborder Serpentes (). Cladistically Squamata, squamates, snakes are ectothermic, amniote vertebrates covered in overlapping Scale (zoology), scales much like other members of ...

) and batracians (amphibians

Amphibians are ectothermic, anamniote, anamniotic, tetrapod, four-limbed vertebrate animals that constitute the class (biology), class Amphibia. In its broadest sense, it is a paraphyletic group encompassing all Tetrapod, tetrapods, but excl ...

, now considered a separate class of vertebrates), describing each group in a single sentence. Thus the batracians are said to have a heart with a single atrium, a naked body (with no scales), and to pass with age from being fish-like to being like a quadruped or biped.

There is then a section heading, in this case "The first order of Reptiles, or The Chelonians", followed by a three-page essay on their zoology, starting with the fact that their hearts have two atria. The structure then repeats at a lower taxonomic level, with what Cuvier notes is one of Linnaeus's genera, '' Testudo'', the tortoises, with five sub-genera. The first sub-genus comprises the land tortoises; their zoology is summed up in a paragraph, which observes that they have a domed carapace

A carapace is a dorsal (upper) section of the exoskeleton or shell in a number of animal groups, including arthropods, such as crustaceans and arachnids, as well as vertebrates, such as turtles and tortoises. In turtles and tortoises, the unde ...

, with a solid bony support (the term being "charpente", commonly used of the structure of wooden beams that support a roof). He records that the legs are thick, with short digits joined for most of their length, five toenails on the forelegs, four on the hind legs.

Then (on the ninth page) he arrives at the first species in the volume, the Greek tortoise, ''Testudo graeca

Greek tortoise (''Testudo graeca''), also known as the spur-thighed tortoise or Moorish tortoise, is a species of tortoise in the family Testudinidae. It is a medium sized herbivorous testudinae, widely distributed in the Mediterranean region. ...

''. It is summed up in a paragraph, Cuvier noting that it is the commonest tortoise in Europe, living in Greece, Italy, Sardinia and (he writes) apparently all round the Mediterranean. He then gives its distinguishing marks, with a highly domed carapace, raised scales boldly marked with black and yellow marbling, and at the posterior edge a bulge over the tail. He gives its size—rarely reaching a foot in length; notes that it lives on leaves, fruit, insects and worms; digs a hole in which to pass the winter; mates in spring, and lays 4 or 5 eggs like those of a pigeon. The species is illustrated with two plates.

Contents

The classification adopted by Cuvier to define the natural structure of the animal kingdom, including both living and fossil forms, was as follows, the list forming the structure of the ''Règne Animal''. Where Cuvier's group names correspond (more or less) to modern taxa, these are named, in English if possible, in parentheses. The table from the 1828 ''

The classification adopted by Cuvier to define the natural structure of the animal kingdom, including both living and fossil forms, was as follows, the list forming the structure of the ''Règne Animal''. Where Cuvier's group names correspond (more or less) to modern taxa, these are named, in English if possible, in parentheses. The table from the 1828 ''Penny Cyclopaedia

''The Penny Cyclopædia'' published by the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge was a multi-volume encyclopedia edited by George Long (scholar), George Long and published by Charles Knight (publisher), Charles Knight alongside the ''Penn ...

'' indicates species that were thought to belong to each group in Cuvier's taxonomy

image:Hierarchical clustering diagram.png, 280px, Generalized scheme of taxonomy

Taxonomy is a practice and science concerned with classification or categorization. Typically, there are two parts to it: the development of an underlying scheme o ...

. The four major divisions were known as ''embranchements'' ("branches").

* I. Vertébrés. (Vertebrates

Vertebrates () are animals with a vertebral column (backbone or spine), and a cranium, or skull. The vertebral column surrounds and protects the spinal cord, while the cranium protects the brain.

The vertebrates make up the subphylum Vertebra ...

)

** Mammifères (Mammals

A mammal () is a vertebrate animal of the class Mammalia (). Mammals are characterised by the presence of milk-producing mammary glands for feeding their young, a broad neocortex region of the brain, fur or hair, and three middle e ...

): 1. Bimanes, 2. Quadrumanes, 3. Carnassiers (Carnivores

A carnivore , or meat-eater (Latin, ''caro'', genitive ''carnis'', meaning meat or "flesh" and ''vorare'' meaning "to devour"), is an animal or plant whose nutrition and energy requirements are met by consumption of animal tissues (mainly mu ...

), 4. Rongeurs (Rodents

Rodents (from Latin , 'to gnaw') are mammals of the order Rodentia ( ), which are characterized by a single pair of continuously growing incisors in each of the upper and lower jaws. About 40% of all mammal species are rodents. They are n ...

), 5. Édentés ( Edentates), 6. Pachydermes ( Pachyderms), 7. Ruminants (Ruminants

Ruminants are herbivorous grazing or browsing artiodactyls belonging to the suborder Ruminantia that are able to acquire nutrients from plant-based food by Enteric fermentation, fermenting it in a specialized stomach prior to digestion, principa ...

), 8. Cétacés (Cetaceans

Cetacea (; , ) is an infraorder of aquatic mammals belonging to the order Artiodactyla that includes whales, dolphins and porpoises. Key characteristics are their fully aquatic lifestyle, streamlined body shape, often large size and exclusively c ...

).

** Oiseaux (Birds

Birds are a group of warm-blooded vertebrates constituting the class (biology), class Aves (), characterised by feathers, toothless beaked jaws, the Oviparity, laying of Eggshell, hard-shelled eggs, a high Metabolism, metabolic rate, a fou ...

): 1. Oiseaux de proie (Birds of prey

Birds of prey or predatory birds, also known as (although not the same as) raptors, are hypercarnivorous bird species that actively predation, hunt and feed on other vertebrates (mainly mammals, reptiles and smaller birds). In addition to speed ...

), 2. Passereaux ( Passerines), 3. Grimpeurs ( Piciformes), 4. Gallinacés ( Gallinaceous birds), 5. Échassiers (Wader

245px, A flock of Red_knot.html" ;"title="Dunlins and Red knot">Dunlins and Red knots

Waders or shorebirds are birds of the order Charadriiformes commonly found wikt:wade#Etymology 1, wading along shorelines and mudflats in order to foraging, ...

s), 6. Palmipèdes (Anseriformes

Anseriformes is an order (biology), order of birds also known as waterfowl that comprises about 180 living species of birds in three families: Anhimidae (three species of screamers), Anseranatidae (the magpie goose), and Anatidae, the largest f ...

).

** Reptiles (Reptiles

Reptiles, as commonly defined, are a group of tetrapods with an ectothermic metabolism and Amniotic egg, amniotic development. Living traditional reptiles comprise four Order (biology), orders: Testudines, Crocodilia, Squamata, and Rhynchocepha ...

, inc. Amphibians): 1. Chéloniens ( Chelonii), 2. Sauriens (Lizards

Lizard is the common name used for all squamate reptiles other than snakes (and to a lesser extent amphisbaenians), encompassing over 7,000 species, ranging across all continents except Antarctica, as well as most oceanic island chains. The ...

), 3. Ophidiens (Snakes

Snakes are elongated Limbless vertebrate, limbless reptiles of the suborder Serpentes (). Cladistically Squamata, squamates, snakes are ectothermic, amniote vertebrates covered in overlapping Scale (zoology), scales much like other members of ...

), 4. Batraciens (Amphibians

Amphibians are ectothermic, anamniote, anamniotic, tetrapod, four-limbed vertebrate animals that constitute the class (biology), class Amphibia. In its broadest sense, it is a paraphyletic group encompassing all Tetrapod, tetrapods, but excl ...

).

** Poissons (Fishes

A fish (: fish or fishes) is an aquatic, anamniotic, gill-bearing vertebrate animal with swimming fins and a hard skull, but lacking limbs with digits. Fish can be grouped into the more basal jawless fish and the more common jawed ...

): 1. Chrondroptérygiens à branchies fixes (Chondrichthyes

Chondrichthyes (; ) is a class of jawed fish that contains the cartilaginous fish or chondrichthyans, which all have skeletons primarily composed of cartilage. They can be contrasted with the Osteichthyes or ''bony fish'', which have skeleto ...

), 2. Sturioniens ou Chrondroptérygiens à branchies libres (Sturgeon

Sturgeon (from Old English ultimately from Proto-Indo-European language, Proto-Indo-European *''str̥(Hx)yón''-) is the common name for the 27 species of fish belonging to the family Acipenseridae. The earliest sturgeon fossils date to the ...

s), 3. Plectognates (Tetraodontiformes

Tetraodontiformes (), also known as the Plectognathi, is an order of ray-finned fishes which includes the pufferfishes and related taxa. This order has been classified as a suborder of the order Perciformes, although recent studies have found ...

), 4. Lophobranches ( Syngnathidae), 5. Malacoptérygiens abdominaux, 6. Malacoptérygiens subbrachiens, 7. Malacoptérygiens apodes, 8. Acanthoptérygiens ( Acanthopterygians).

* II. Mollusques. (Molluscs

Mollusca is a phylum of protostome, protostomic invertebrate animals, whose members are known as molluscs or mollusks (). Around 76,000 extant taxon, extant species of molluscs are recognized, making it the second-largest animal phylum ...

)

** Céphalopodes. (Cephalopods

A cephalopod is any member of the molluscan Taxonomic rank, class Cephalopoda (Greek language, Greek plural , ; "head-feet") such as a squid, octopus, cuttlefish, or nautilus. These exclusively marine animals are characterized by bilateral symm ...

)

** Ptéropodes. ( Pteropods)

** Gastéropodes (Gastropods

Gastropods (), commonly known as slugs and snails, belong to a large taxonomic class of invertebrates within the phylum Mollusca called Gastropoda ().

This class comprises snails and slugs from saltwater, freshwater, and from the land. Ther ...

): 1. Nudibranches (Nudibranchs

Nudibranchs () are a group of soft-bodied marine gastropod molluscs, belonging to the order Nudibranchia, that shed their shells after their larval stage. They are noted for their often extraordinary colours and striking forms, and they have be ...

), 2. Inférobranches, 3. Tectibranches, 4. Pulmonés ( Pulmonata), 5. Pectinibranches, 6. Scutibranches, 7. Cyclobranches.

** Acéphales: 1. Testacés (Bivalves

Bivalvia () or bivalves, in previous centuries referred to as the Lamellibranchiata and Pelecypoda, is a class of aquatic molluscs (marine and freshwater) that have laterally compressed soft bodies enclosed by a calcified exoskeleton consis ...

), 2. Sans coquilles ( Tunicates).

** Brachiopodes. (Brachiopods

Brachiopods (), phylum Brachiopoda, are a phylum of animals that have hard "valves" (shells) on the upper and lower surfaces, unlike the left and right arrangement in bivalve molluscs. Brachiopod valves are hinged at the rear end, while the fron ...

, now a separate phylum)

** Cirrhopodes. (Barnacles

Barnacles are arthropods of the subclass Cirripedia in the subphylum Crustacea. They are related to crabs and lobsters, with similar nauplius larvae. Barnacles are exclusively marine invertebrates; many species live in shallow and tidal water ...

, now in Crustacea)

* III. Articulés. (Articulated animals: now Arthropods

Arthropods ( ) are invertebrates in the phylum Arthropoda. They possess an arthropod exoskeleton, exoskeleton with a cuticle made of chitin, often Mineralization (biology), mineralised with calcium carbonate, a body with differentiated (Metam ...

and Annelids)

** Annélides (Annelids

The annelids (), also known as the segmented worms, are animals that comprise the phylum Annelida (; ). The phylum contains over 22,000 extant species, including ragworms, earthworms, and leeches. The species exist in and have adapted to vario ...

): 1. Tubicoles, 2. Dorsibranches, 3. Abranches.

** Crustacés (Crustaceans

Crustaceans (from Latin meaning: "those with shells" or "crusted ones") are invertebrate animals that constitute one group of Arthropod, arthropods that are traditionally a part of the subphylum Crustacea (), a large, diverse group of mainly aquat ...

): 1. Décapodes (Decapods

The Decapoda or decapods, from Ancient Greek δεκάς (''dekás''), meaning "ten", and πούς (''poús''), meaning "foot", is a large order (biology), order of crustaceans within the class Malacostraca, and includes crabs, lobsters, crayfis ...

), 2. Stomapodes ( Stomatopods), 3. Amphipodes (Amphipods

Amphipoda () is an order (biology), order of malacostracan crustaceans with no carapace and generally with laterally compressed bodies. Amphipods () range in size from and are mostly detritivores or scavengers. There are more than 10,700 amphip ...

), 4. Isopodes (Isopods

Isopoda is an Order (biology), order of crustaceans. Members of this group are called isopods and include both Aquatic animal, aquatic species and Terrestrial animal, terrestrial species such as woodlice. All have rigid, segmented exoskeletons ...

), 5. Branchiopodes ( Branchiopods).

** Arachnides (Arachnids

Arachnids are arthropods in the class Arachnida () of the subphylum Chelicerata. Arachnida includes, among others, spiders, scorpions, ticks, mites, pseudoscorpions, harvestmen, camel spiders, whip spiders and vinegaroons.

Adult arachnids ...

): 1. Pulmonaires, 2. Trachéennes.

** Insectes (Insects

Insects (from Latin ') are hexapod invertebrates of the class Insecta. They are the largest group within the arthropod phylum. Insects have a chitinous exoskeleton, a three-part body (head, thorax and abdomen), three pairs of jointed ...

, inc. Myriapods

Myriapods () are the members of subphylum Myriapoda, containing arthropods such as millipedes and centipedes. The group contains about 13,000 species, all of them terrestrial.

Although molecular evidence and similar fossils suggests a diversifi ...

): 1. Myriapodes, 2. Thysanoures (Thysanura

Thysanura is the now Deprecation, deprecated name of what was, for over a century, recognised as an Order (biology), order in the Class (biology), class Insecta. The two constituent groups within the former order, the Archaeognatha (jumping bristle ...

), 3. Parasites, 4. Suceurs, 5. Coléoptères (Coleoptera

Beetles are insects that form the Taxonomic rank, order Coleoptera (), in the superorder Holometabola. Their front pair of wings are hardened into wing-cases, elytra, distinguishing them from most other insects. The Coleoptera, with about 40 ...

), 6. Orthoptères (Orthoptera

Orthoptera () is an order of insects that comprises the grasshoppers, locusts, and crickets, including closely related insects, such as the bush crickets or katydids and wētā. The order is subdivided into two suborders: Caelifera – gras ...

), 7. Hémiptères (Hemiptera

Hemiptera (; ) is an order of insects, commonly called true bugs, comprising more than 80,000 species within groups such as the cicadas, aphids, planthoppers, leafhoppers, assassin bugs, bed bugs, and shield bugs. They range in size from ...

), 8. Névroptères (Neuroptera

The insect order (biology), order Neuroptera, or net-winged insects, includes the lacewings, mantidflies, antlions, and their relatives. The order consists of some 6,000 species. Neuroptera is grouped together with the Megaloptera (alderflies, f ...

), 9. Hyménoptères (Hymenoptera

Hymenoptera is a large order of insects, comprising the sawflies, wasps, bees, and ants. Over 150,000 living species of Hymenoptera have been described, in addition to over 2,000 extinct ones. Many of the species are parasitic.

Females typi ...

), 10. Lépidoptères (Lepidoptera

Lepidoptera ( ) or lepidopterans is an order (biology), order of winged insects which includes butterflies and moths. About 180,000 species of the Lepidoptera have been described, representing 10% of the total described species of living organ ...

), 11. Ripiptères (Strepsiptera

The Strepsiptera () are an order of insects with eleven extant families that include about 600 described species. They are endoparasites of other insects, such as bees, wasps, leafhoppers, Zygentoma, silverfish, and cockroaches. Females of most s ...

), 12. Diptères (Diptera

Flies are insects of the order Diptera, the name being derived from the Greek δι- ''di-'' "two", and πτερόν ''pteron'' "wing". Insects of this order use only a single pair of wings to fly, the hindwings having evolved into advance ...

).

* IV. Zoophytes. (Zoophytes

A zoophyte (animal-plant) is an obsolete term for an organism thought to be intermediate between animals and plants, or an animal with plant-like attributes or appearance. In the 19th century they were reclassified as Radiata which included vario ...

, called Radiata

Radiata or Radiates is a historical taxonomic rank that was used to classify animals with Symmetry (biology)#Radial symmetry, radially symmetric body plans. The term Radiata is no longer accepted, as it united several different groupings of anim ...

in English translations; now Cnidaria and other phyla)

** Échinodermes (Echinoderms

An echinoderm () is any animal of the phylum Echinodermata (), which includes starfish, brittle stars, sea urchins, sand dollars and sea cucumbers, as well as the sessile sea lilies or "stone lilies". While bilaterally symmetrical as larv ...

): 1. Pédicellés, 2. Sans pieds.

** Intestinaux (Helminth

Parasitic worms, also known as helminths, are a polyphyletic group of large macroparasites; adults can generally be seen with the naked eye. Many are intestinal worms that are soil-transmitted and infect the gastrointestinal tract. Other par ...

s): 1. Cavitaires, 2. Parenchymateux.

** Acalèphes (Jellyfish

Jellyfish, also known as sea jellies or simply jellies, are the #Life cycle, medusa-phase of certain gelatinous members of the subphylum Medusozoa, which is a major part of the phylum Cnidaria. Jellyfish are mainly free-swimming marine animal ...

and other free-floating polyps): 1. Fixes, 2. Libres.

** Polypes (Cnidaria

Cnidaria ( ) is a phylum under kingdom Animalia containing over 11,000 species of aquatic invertebrates found both in fresh water, freshwater and marine environments (predominantly the latter), including jellyfish, hydroid (zoology), hydroids, ...

): 1. Nus, 2. À polypiers.

** Infusoires (Infusoria

Infusoria is a word used to describe various freshwater microorganisms, including ciliates, copepods, Euglena, euglenoids, planktonic crustaceans, protozoa, unicellular algae and small invertebrates. Some authors (e.g., Otto Bütschli, Bütschli) ...

, various protista

A protist ( ) or protoctist is any Eukaryote, eukaryotic organism that is not an animal, Embryophyte, land plant, or fungus. Protists do not form a Clade, natural group, or clade, but are a Paraphyly, paraphyletic grouping of all descendants o ...

n phyla): 1. Rotifères (Rotifers

The rotifers (, from Latin 'wheel' and 'bearing'), sometimes called wheel animals or wheel animalcules, make up a phylum (Rotifera ) of microscopic and near-microscopic pseudocoelomate animals.

They were first described by Rev. John Harris ...

), 2. Homogènes.

Reception

Contemporary

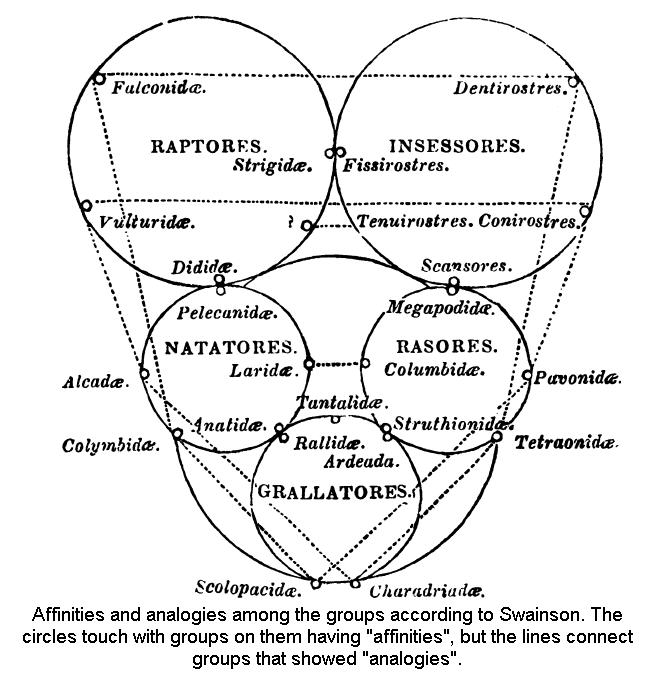

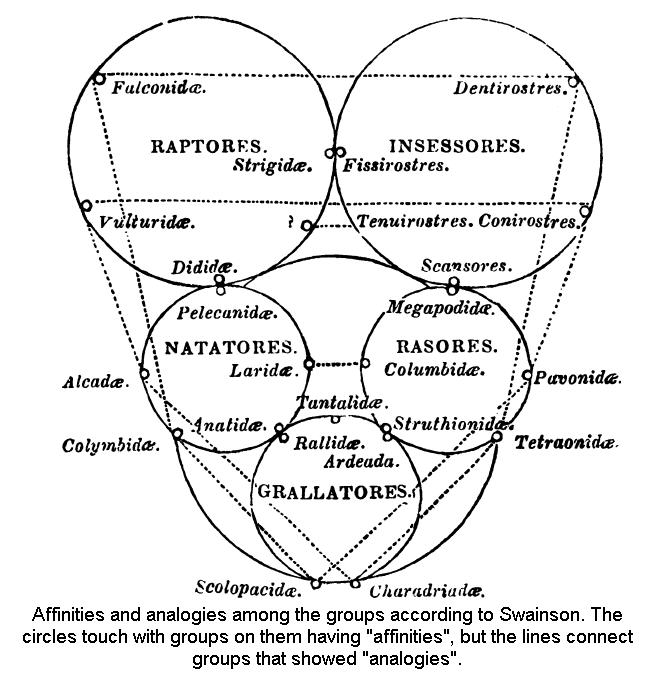

The entomologist William Sharp Macleay, in his 1821 book ''Horae Entomologicae'' which put forward the short-lived " Quinarian" system of classification into 5 groups, each of 5 subgroups, etc., asserted that in the ''Règne Animal'' "Cuvier was notoriously deficient in the power of legitimate and intuitive generalization in arranging the animal series". The zoologist

The entomologist William Sharp Macleay, in his 1821 book ''Horae Entomologicae'' which put forward the short-lived " Quinarian" system of classification into 5 groups, each of 5 subgroups, etc., asserted that in the ''Règne Animal'' "Cuvier was notoriously deficient in the power of legitimate and intuitive generalization in arranging the animal series". The zoologist William Swainson

William Swainson Fellow of the Linnean Society, FLS, Fellow of the Royal Society, FRS (8 October 1789 – 6 December 1855), was an English ornithologist, Malacology, malacologist, Conchology, conchologist, entomologist and artist.

Life

Swains ...

, also a Quinarian, added that "no person of such transcendent talents and ingenuity, ever made so little use of his observations towards a natural arrangement as M. Cuvier."

The '' Magazine of Natural History'' of 1829 expressed surprise at the long interval between the first and second editions, surmising that there were too few scientific readers in France, apart from those in Paris itself; it notes that while the first volume was little changed, the treatment of fish was considerably altered in volume II, while the section on the Articulata was greatly enlarged (to two volumes, IV and V) and written by M. Latreille. It also expressed the hope that there would be an English equivalent of Cuvier's work, given the popularity of natural history resulting from the works of Thomas Bewick

Thomas Bewick (c. 11 August 1753 – 8 November 1828) was an English wood engraving, wood-engraver and natural history author. Early in his career he took on all kinds of work such as engraving cutlery, making the wood blocks for advertisements, ...

(''A History of British Birds

''A History of British Birds'' is a natural history book by Thomas Bewick, published in two volumes. Volume 1, ''Land Birds'', appeared in 1797. Volume 2, ''Water Birds'', appeared in 1804. A supplement was published in 1821. The text in ''Land ...

'' 1797–1804) and George Montagu ('' Ornithological Dictionary'', 1802). The same review covers Félix Édouard Guérin-Méneville

Félix Édouard Guérin-Méneville, also known as F. E. Guerin, (12 October 1799, in Toulon – 26 January 1874, in Paris) was a French entomologist.

Life and work

Guérin-Méneville changed his surname from Guérin in 1836. He was the author o ...

's ''Iconographie du Règne Animal de M. le Baron Cuvier'', which offered illustrations of all Cuvier's genera (except for the birds).

The ''Foreign Review'' of 1830 broadly admired Cuvier's work, but disagreed with his classification. It commented that "From the comprehensive nature of the ''Règne Animal'', embracing equally the structure and history of all the existing and extinct races of animals, this work may be viewed as an epitome of M. Cuvier's zoological labours; and it presents the best outline, which exists in any language, of the present state of zoology and comparative anatomy." The review continued less favourably, however, that "We cannot help thinking that the science of comparative anatomy is now so far advanced, as to afford the means of distributing the animal kingdom on some more uniform and philosophical principles,—as on the modifications of those systems or functions which are most general in the animal economy". The review argued that the vertebrate division relied on the presence of a vertebral column, "a part of the organization of comparatively little importance in the economy"; it found the basis of the mollusca on "the general softness of the body" no better; the choice of the presence of articulations no better either, in the third division; while in the fourth it points out that while the echinoderms may fit well into the chosen scheme, it did not apply "to the entozoa, zoophyta, and infusoria, which constitute by much the greatest portion of this division." But the review notes that "the general distribution of the animal kingdom established by M. Cuvier in this work, are founded on a more extensive and minute survey of the organization than had ever before been taken, and many of the most important distinctions among the orders and families are the result of his own researches."

Writing in the ''Monthly Review'' of 1834, the pre-Darwinian evolutionist surgeon Sir William Lawrence commented that "the ''Regne Animal'' of Cuvier is, in short, an abridged expression of the entire science. He carried the lights derived from his zoological researches into kindred but obscure parts of nature." Lawrence calls the work "an arrangement of the animal kingdom nearly approaching to perfection; grounded on principles so accurate, that the place which any animal occupies in this scheme, already indicates the leading circumstances in its structure, economy, and habits."

The book was in the library of ''HMS Beagle

HMS ''Beagle'' was a 10-gun brig-sloop of the Royal Navy, one of more than 100 ships of this class. The vessel, constructed at a cost of £7,803, was launched on 11 May 1820 from the Woolwich Dockyard on the River Thames. Later reports say ...

'' for Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English Natural history#Before 1900, naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all speci ...

's voyage. In ''The Origin of Species

''On the Origin of Species'' (or, more completely, ''On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life'')The book's full original title was ''On the Origin of Species by M ...

'' (1859), in a chapter on the difficulties facing the theory, Darwin comments that "The expression of conditions of existence, so often insisted on by the illustrious Cuvier, is fully embraced by the principle of natural selection

Natural selection is the differential survival and reproduction of individuals due to differences in phenotype. It is a key mechanism of evolution, the change in the Heredity, heritable traits characteristic of a population over generation ...

." Darwin continues, reflecting both on Cuvier's emphasis on the conditions of existence, and Jean-Baptiste Lamarck

Jean-Baptiste Pierre Antoine de Monet, chevalier de Lamarck (1 August 1744 – 18 December 1829), often known simply as Lamarck (; ), was a French naturalist, biologist, academic, and soldier. He was an early proponent of the idea that biologi ...

's theory of acquiring heritable characteristics from those Cuvieran conditions: "For natural selection acts by either now adapting the varying parts of each being to its organic and inorganic conditions of life; or by having adapted them during long-past periods of time: the adaptations being aided in some cases by use and disuse, being slightly affected by the direct action of the external conditions of life, and being in all cases subjected to the several laws of growth. Hence, in fact, the law of the Conditions of Existence is the higher law; as it includes, through the inheritance of former adaptations, that of Unity of Type."

Modern

The palaeontologist Philippe Taquet wrote that "the ''Règne Animal'' was an attempt to create a complete inventory of the animal kingdom and to formulate a natural classification underpinned by the principles of the 'correlation of parts'.." He adds that with the book "Cuvier introduced clarity into natural history, accurately reproducing the actual ordering of animals." Taquet further notes that while Cuvier rejected evolution, it was paradoxically "the precision of his anatomical descriptions and the importance of his research on fossil bones", showing for instance that mammoths were extinct elephants, that enabled later naturalists including Darwin to argue convincingly that animals had evolved.Notes

References

External links

* Cuvier, Georges; Latreille, Pierre André.Le Règne Animal Distribué d'après son Organisation, pour Servir de Base à l'Histoire Naturelle des Animaux et d'Introduction à l'Anatomie Comparée

'. Déterville libraire, Imprimerie de A. Belin, Paris, 4 Volumes, 1816.

Volume I

(introduction, mammals, birds)

Volume II

(reptiles, fish, molluscs, annelids)

Volume III

(crustaceans, arachnids, insects)

Volume IV

(zoophytes; tables, plates) {{DEFAULTSORT:Regne Animal 1816 non-fiction books Natural history books Zoology books