John Robert Lewis (February 21, 1940 – July 17, 2020) was an American

civil rights activist

Civil and political rights are a class of rights that protect individuals' freedom from infringement by governments, social organizations, and private individuals. They ensure one's entitlement to participate in the civil and political life of ...

and politician who served in the

United States House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives is a chamber of the Bicameralism, bicameral United States Congress; it is the lower house, with the U.S. Senate being the upper house. Together, the House and Senate have the authority under Artic ...

for from 1987 until his death in 2020. He participated in the 1960

Nashville sit-ins

The Nashville sit-ins, which lasted from February 13 to May 10, 1960, were part of a protest to end racial segregation at lunch counters in downtown Nashville, Tennessee, Nashville, Tennessee. The sit-in campaign, coordinated by the Nashville S ...

and the

Freedom Rides

Freedom Riders were civil rights activists who rode interstate buses into the segregated Southern United States in 1961 and subsequent years to challenge the non-enforcement of the United States Supreme Court decisions '' Morgan v. Virginia' ...

, was the chairman of the

Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee

The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, and later, the Student National Coordinating Committee (SNCC, pronounced ) was the principal channel of student commitment in the United States to the civil rights movement during the 1960s. Emer ...

(SNCC) from 1963 to 1966, and was one of the "

Big Six" leaders of groups who organized the 1963

March on Washington

The March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom (commonly known as the March on Washington or the Great March on Washington) was held in Washington, D.C., on August 28, 1963. The purpose of the march was to advocate for the civil and economic rig ...

. Fulfilling many key roles in the

civil rights movement and its actions to end legalized

racial segregation in the United States

Facilities and services such as housing, healthcare, education, employment, and transportation have been systematically separated in the United States based on racial categorizations. Notably, racial segregation in the United States was the leg ...

, in 1965 Lewis led the first of three

Selma to Montgomery marches

The Selma to Montgomery marches were three Demonstration (protest), protest marches, held in 1965, along the highway from Selma, Alabama, to the state capital of Montgomery, Alabama, Montgomery. The marches were organized by Nonviolence, nonvi ...

across the

Edmund Pettus Bridge

The Edmund Pettus Bridge carries U.S. Route 80 Business (Selma, Alabama), U.S. Route 80 Business (US 80 Bus.) across the Alabama River in Selma, Alabama, United States. Built in 1940, it is named after Edmund Pettus, a former Confeder ...

where, in an incident that became known as

Bloody Sunday, state troopers and police attacked Lewis and the other marchers.

A member of the

Democratic Party, Lewis was first elected to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1986 and served 17 terms. The district he represented included most of

Atlanta

Atlanta ( ) is the List of capitals in the United States, capital and List of municipalities in Georgia (U.S. state), most populous city in the U.S. state of Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia. It is the county seat, seat of Fulton County, Georg ...

. Due to his length of service, he became the dean of the

Georgia congressional delegation. He was one of the leaders of the Democratic Party in the House, serving from 1991 as a

chief deputy whip and from 2003 as a

senior chief deputy whip. He received many honorary degrees and awards, including the

Presidential Medal of Freedom

The Presidential Medal of Freedom is the highest civilian award of the United States, alongside the Congressional Gold Medal. It is an award bestowed by decision of the president of the United States to "any person recommended to the President ...

in 2011.

Early life and education

John Robert Lewis was born near

Troy, Alabama

Troy is a city in and the county seat of Pike County, Alabama, United States. It was formally incorporated on February 4, 1843.

Between 1763 and 1783, the area where Troy sits was part of the colony of British West Florida.The Economy of Bri ...

, on February 21, 1940, the third of ten children of Willie Mae (née Carter) and Eddie Lewis.

[Stated on '']Finding Your Roots

''Finding Your Roots with Henry Louis Gates, Jr.'' is an American documentary television series hosted by Henry Louis Gates Jr. that premiered on March 25, 2012, on PBS. In each episode, celebrities are presented with a "book of life" that is com ...

'', PBS

The Public Broadcasting Service (PBS) is an American public broadcaster and non-commercial, free-to-air television network based in Arlington, Virginia. PBS is a publicly funded nonprofit organization and the most prominent provider of educat ...

, March 25, 2012. His parents were

sharecroppers in rural

Pike County, Alabama, of which Troy was the county seat.

[''Reporting Civil Rights: American Journalism 1963–1973, Part Two '' Carson, Clayborne, Garrow, David, Kovach, Polsgrove, Carol (Editorial Advisory Board), (Library of America: 2003) , pp. 15–16, 48, 56, 84, 323, 374, 384, 392, 491–94, 503, 505, 513, 556, 726, 751, 846, 873.] His great-grandfather, Frank Carter, had been born enslaved in the same county in 1862, and lived until Lewis was seven years old.

As a boy, Lewis aspired to be a preacher,

[ ( NPR station)] and at age five, he preached to his family's chickens on the farm.

As a young child, Lewis had little interaction with

white people

White is a Race (human categorization), racial classification of people generally used for those of predominantly Ethnic groups in Europe, European ancestry. It is also a Human skin color, skin color specifier, although the definition can var ...

, as his county was majority black by a large percentage and his family worked as farmers. By the time he was six, Lewis had seen only two white people in his life. Lewis recalls "I grew up in rural Alabama, very poor, very few books in our home." He describes his early education at a little school, walking distances from his home. "A beautiful little building, it was a

Rosenwald School. It was supported by the community, it was the only school we had." "I had a wonderful teacher in elementary school, and she told me 'read my child, read!' And I tried to read everything. I loved books. I remember in 1956, when I was 16 years old, with some of my brothers and sisters and cousins, going down to the public library, trying to get a library card, and we were told the library was for whites only and not for coloreds." As he grew older, he began taking trips into Troy with his family, where he continued to have experiences of racism and segregation. Lewis had relatives who lived in northern cities, and he learned from them that in the North, schools, buses, and businesses were integrated. When Lewis was 11, an uncle took him to

Buffalo, New York, where he became acutely aware of the contrast with Troy's segregation.

In 1955, Lewis first heard

Martin Luther King Jr.

Martin Luther King Jr. (born Michael King Jr.; January 15, 1929 – April 4, 1968) was an American Baptist minister, civil and political rights, civil rights activist and political philosopher who was a leader of the civil rights move ...

on the radio, and he closely followed King's

Montgomery bus boycott

The Montgomery bus boycott was a political and social boycott, protest campaign against the policy of racial segregation on the public transit system of Montgomery, Alabama. It was a foundational event in the civil rights movement in the United ...

later that year. At age 15, Lewis preached his first public sermon.

[ At 17, Lewis met ]Rosa Parks

Rosa Louise McCauley Parks (February 4, 1913 – October 24, 2005) was an American civil rights activist. She is best known for her refusal to move from her seat on a Montgomery, Alabama, bus, in defiance of Jim Crow laws, which sparke ...

, notable for her role in the bus boycott, and met King for the first time at the age of 18.Billy Graham

William Franklin Graham Jr. (; November 7, 1918 – February 21, 2018) was an American Evangelism, evangelist, ordained Southern Baptist minister, and Civil rights movement, civil rights advocate, whose broadcasts and world tours featuring liv ...

, a friend of King's, as someone who "helped change me".[Billy Graham passes away: Congressman John Lewis remembers the reverend]

11 Alive, February 21, 2018, Accessed October 6, 2020Nashville, Tennessee

Nashville, often known as Music City, is the capital and List of municipalities in Tennessee, most populous city in the U.S. state of Tennessee. It is the county seat, seat of Davidson County, Tennessee, Davidson County in Middle Tennessee, locat ...

, and was ordained as a Baptist

Baptists are a Christian denomination, denomination within Protestant Christianity distinguished by baptizing only professing Christian believers (believer's baptism) and doing so by complete Immersion baptism, immersion. Baptist churches ge ...

minister.[ He then earned a bachelor's degree in religion and philosophy from ]Fisk University

Fisk University is a Private university, private Historically black colleges and universities, historically black Liberal arts colleges in the United States, liberal arts college in Nashville, Tennessee. It was founded in 1866 and its campus i ...

, also a historically black college

Historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs) are institutions of higher education in the United States that were established before the Civil Rights Act of 1964 with the intention of serving African Americans. Most are in the Southern U ...

. He was a member of Phi Beta Sigma

Phi Beta Sigma Fraternity, Inc. () is a historically African American fraternity. It was founded at Howard University in Washington, D.C. in 1914. The fraternity's founders, A. Langston Taylor, Leonard F. Morse, and Charles I. Brown, wanted to ...

fraternity.

Student activism and SNCC

Nashville Student Movement

As a student, Lewis became an activist in the civil rights movement. He organized sit-ins at segregated lunch counters in Nashville and took part in many other civil rights activities as part of the Nashville Student Movement. The Nashville sit-in movement was responsible for the desegregation of lunch counters in the city's downtown. Lewis was arrested and jailed many times during the

As a student, Lewis became an activist in the civil rights movement. He organized sit-ins at segregated lunch counters in Nashville and took part in many other civil rights activities as part of the Nashville Student Movement. The Nashville sit-in movement was responsible for the desegregation of lunch counters in the city's downtown. Lewis was arrested and jailed many times during the nonviolent

Nonviolence is the personal practice of not causing harm to others under any condition. It may come from the belief that hurting people, animals and/or the environment is unnecessary to achieve an outcome and it may refer to a general philosoph ...

activities to desegregate the city's downtown businesses. He was also instrumental in organizing bus boycotts and other nonviolent protests to support voting rights and racial equality.

During this time, Lewis said it was important to engage in "good trouble, necessary trouble" in order to achieve change, and he held to this credo throughout his life.

While a student, Lewis was invited to attend nonviolence

Nonviolence is the personal practice of not causing harm to others under any condition. It may come from the belief that hurting people, animals and/or the environment is unnecessary to achieve an outcome and it may refer to a general philosoph ...

workshops held at Clark Memorial United Methodist Church by the Rev. James Lawson and Rev. Kelly Miller Smith. Lewis and other students became dedicated to the discipline and philosophy of nonviolence, which he practiced for the rest of his life.

Freedom Riders

In 1961, Lewis became one of the 13 original Freedom Riders

Freedom Riders were civil rights activists who rode interstate buses into the Racial segregation in the United States, segregated Southern United States, Southern United States in 1961 and subsequent years to challenge the non-enforcement of t ...

.New Orleans

New Orleans (commonly known as NOLA or The Big Easy among other nicknames) is a Consolidated city-county, consolidated city-parish located along the Mississippi River in the U.S. state of Louisiana. With a population of 383,997 at the 2020 ...

to challenge the policies of Southern states along the route that had imposed segregated seating on the buses, which violated federal policy for interstate transportation. The "Freedom Ride", originated by the Fellowship of Reconciliation

The Fellowship of Reconciliation (FoR or FOR) is the name used by a number of religious nonviolent organizations, particularly in English-speaking countries. They are linked by affiliation to the International Fellowship of Reconciliation (IFOR). ...

and revived by James Farmer

James Leonard Farmer Jr. (January 12, 1920 – July 9, 1999) was an American civil rights activist and leader in the Civil Rights Movement "who pushed for nonviolent protest to dismantle segregation, and served alongside Martin Luther King Jr." ...

and the Congress of Racial Equality

The Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) is an African-American civil rights organization in the United States that played a pivotal role for African Americans in the civil rights movement. Founded in 1942, its stated mission is "to bring about ...

(CORE), was initiated to pressure the federal government to enforce the Supreme Court decision in ''Boynton v. Virginia

''Boynton v. Virginia'', 364 U.S. 454 (1960), was a List of landmark court decisions in the United States, landmark decision of the US Supreme Court.. The case overturned a Legal judgment, judgment conviction (law), convicting an African America ...

'' (1960), which declared segregated interstate bus travel to be unconstitutional. The Freedom Rides revealed the passivity of the local, state, and federal governments in the face of violence against law-abiding citizens.Alabama

Alabama ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Deep South, Deep Southern regions of the United States. It borders Tennessee to the north, Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia to the east, Florida and the Gu ...

police to protect the riders, even though the state was known for notorious racism, and did not undertake actions except assigning FBI

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) is the domestic Intelligence agency, intelligence and Security agency, security service of the United States and Federal law enforcement in the United States, its principal federal law enforcement ag ...

agents to record incidents. After extreme violence broke out in South Carolina

South Carolina ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders North Carolina to the north and northeast, the Atlantic Ocean to the southeast, and Georgia (U.S. state), Georg ...

and Alabama, the Kennedy Administration

John F. Kennedy's tenure as the List of presidents of the United States, 35th president of the United States began with Inauguration of John F. Kennedy, his inauguration on January 20, 1961, and ended with Assassination of John F. Kennedy, his ...

called for a "cooling-off" period, with a moratorium on Freedom Rides.Rock Hill, South Carolina

Rock Hill is the most populous city in York County, South Carolina, United States, and the List of municipalities in South Carolina, 5th-most populous city in the state. It is also the 4th-most populous city of the Charlotte metropolitan area, be ...

. When he tried to enter a whites-only waiting room, two white men attacked him, injuring his face and kicking him in the ribs. Two weeks later Lewis joined a Freedom Ride bound for Jackson, Mississippi

Jackson is the List of capitals in the United States, capital and List of municipalities in Mississippi, most populous city of the U.S. state of Mississippi. The city sits on the Pearl River (Mississippi–Louisiana), Pearl River and is locate ...

. Near the end of his life, Lewis said of this time, "We were determined not to let any act of violence keep us from our goal. We knew our lives could be threatened, but we had made up our minds not to turn back."CNN

Cable News Network (CNN) is a multinational news organization operating, most notably, a website and a TV channel headquartered in Atlanta. Founded in 1980 by American media proprietor Ted Turner and Reese Schonfeld as a 24-hour cable ne ...

during the 40th anniversary of the Freedom Rides, Lewis recounted the violence he and the 12 other original Freedom Riders endured. In Birmingham

Birmingham ( ) is a City status in the United Kingdom, city and metropolitan borough in the metropolitan county of West Midlands (county), West Midlands, within the wider West Midlands (region), West Midlands region, in England. It is the Lis ...

, the Riders were beaten by an unrestrained mob including KKK members (notified of their arrival by police) with baseball bats, chains, lead pipes, and stones. The police arrested them, and led them across the border into Tennessee before letting them go. The Riders reorganized and rode to Montgomery, where they were met with more violence at the local Greyhound station. There Lewis was hit in the head with a wooden crate. "It was very violent. I thought I was going to die. I was left lying at the Greyhound bus station in Montgomery unconscious", said Lewis, remembering the incident.

When CORE gave up on the Freedom Ride because of the violence, Lewis and fellow activist Diane Nash

Diane Judith Nash (born May 15, 1938) is an American civil rights activist, and a leader and strategist of the student wing of the Civil Rights Movement.

Nash's campaigns were among the most successful of the era. Her efforts included the first s ...

arranged for Nashville students from Fisk and other colleges to take it over and bring it to a successful conclusion.Michael Schwerner

Michael Henry Schwerner (November 6, 1939 – June 21, 1964) was an American civil rights activist. He was one of three Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) field workers murdered in rural Neshoba County, Mississippi, by members of the Ku Klux K ...

and Andrew Goodman from New York. They, along with James Chaney, a local African-American activist from Mississippi, were abducted and murdered in June 1964 in Neshoba County, Mississippi, by members of the Ku Klux Klan

The Ku Klux Klan (), commonly shortened to KKK or Klan, is an American Protestant-led Christian terrorism, Christian extremist, white supremacist, Right-wing terrorism, far-right hate group. It was founded in 1865 during Reconstruction era, ...

including law enforcement.

SNCC Chairman

In 1963, when Charles McDew stepped down as chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), Lewis, a founding member, was elected to take over. Lewis's experience was already widely respected. His courage and tenacious adherence to the philosophy of reconciliation and nonviolence had enabled him to emerge as a leader. He had already been arrested 24 times in the nonviolent movement for equal justice. As chairman of SNCC, Lewis was one of the "Big Six" leaders who were organizing the March on Washington

The March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom (commonly known as the March on Washington or the Great March on Washington) was held in Washington, D.C., on August 28, 1963. The purpose of the march was to advocate for the civil and economic rig ...

that summer. The youngest, he was scheduled as the fourth to speak, ahead of the final speaker, Dr. Martin Luther King. Other leaders were Whitney Young, A. Philip Randolph, James Farmer

James Leonard Farmer Jr. (January 12, 1920 – July 9, 1999) was an American civil rights activist and leader in the Civil Rights Movement "who pushed for nonviolent protest to dismantle segregation, and served alongside Martin Luther King Jr." ...

, and Roy Wilkins

Roy Ottoway Wilkins (August 30, 1901 – September 8, 1981) was an American civil rights leader from the 1930s to the 1970s. Wilkins' most notable role was his leadership of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), ...

.

Lewis had written a response to Kennedy's 1963 Civil Rights Bill. Lewis and his fellow SNCC workers had suffered from the federal government's passivity in the face of Southern violence.police brutality

Police brutality is the excessive and unwarranted use of force by law enforcement against an individual or Public order policing, a group. It is an extreme form of police misconduct and is a civil rights violation. Police brutality includes, b ...

, or to provide African Americans with the means to vote; he described the bill as "too little and too late". Advance copies of the speech were distributed on August 27 but encountered opposition from the other chairs of the march who demanded revisions. James Forman rapidly re-wrote the speech, replacing Lewis's initial assertion "we cannot support, wholeheartedly the ennedycivil rights bill" with "We support it with great reservations."

After Lewis, Dr. King gave his now celebrated "I Have a Dream" speech. Historian Howard Zinn

Howard Zinn (August 24, 1922January 27, 2010) was an American historian and a veteran of World War II. He was chair of the history and social sciences department at Spelman College, and a political science professor at Boston University. Zinn ...

later wrote of this occasion:

In 1964, SNCC opened Freedom Schools, launched the Mississippi Freedom Summer

Freedom Summer, also known as Mississippi Freedom Summer (sometimes referred to as the Freedom Summer Project or the Mississippi Summer Project), was a campaign launched by civil rights movement, American civil rights activists in June 1964 to r ...

for voter education and registration. Lewis coordinated SNCC's efforts for Freedom Summer, a campaign to register black voters in Mississippi and to engage college student activists in aiding the campaign. Lewis traveled the country, encouraging students to spend their summer break trying to help people vote in Mississippi, which had the lowest number of black voters and strong resistance to the movement.

In 1965 Lewis organized some of the voter registration efforts during the 1965 Selma voting rights campaign, and became nationally known during his prominent role in the Selma to Montgomery marches

The Selma to Montgomery marches were three Demonstration (protest), protest marches, held in 1965, along the highway from Selma, Alabama, to the state capital of Montgomery, Alabama, Montgomery. The marches were organized by Nonviolence, nonvi ...

. On March 7, 1965 – a day that would become known as " Bloody Sunday" – Lewis and fellow activist Hosea Williams

Hosea Lorenzo Williams (January 5, 1926 – November 16, 2000) was an American American civil rights movement, civil rights leader, activist, ordained minister, businessman, philanthropist, scientist, and politician. He was considered a member ...

led over 600 marchers across the Edmund Pettus Bridge

The Edmund Pettus Bridge carries U.S. Route 80 Business (Selma, Alabama), U.S. Route 80 Business (US 80 Bus.) across the Alabama River in Selma, Alabama, United States. Built in 1940, it is named after Edmund Pettus, a former Confeder ...

in Selma, Alabama

Selma is a city in and the county seat of Dallas County, in the Black Belt region of south central Alabama and extending to the west. Located on the banks of the Alabama River, the city has a population of 17,971 as of the 2020 census. Abou ...

. At the end of the bridge and the city-county boundary, they were met by Alabama State Troopers who ordered them to disperse. When the marchers stopped to pray, the police discharged tear gas

Tear gas, also known as a lachrymatory agent or lachrymator (), sometimes colloquially known as "mace" after the Mace (spray), early commercial self-defense spray, is a chemical weapon that stimulates the nerves of the lacrimal gland in the ey ...

and mounted troopers charged the demonstrators, beating them with nightsticks. Lewis's skull was fractured, but he was aided in escaping across the bridge to Brown Chapel, a church in Selma that served as the movement's headquarters. Lewis bore scars on his head from this incident for the rest of his life.

Lewis served as SNCC chairman until 1966, when he was replaced by Stokely Carmichael.

Field Foundation, SRC, and VEP (1966–1977)

In 1966, Lewis moved to New York City to take a job as the associate director of the Field Foundation of New York.Southern Regional Council

The Southern Regional Council (SRC) is a reform-oriented organization created in 1944 to avoid racial violence and promote racial equality in the Southern United States. Voter registration and political-awareness campaigns are used toward this ...

's Community Organization Project.1973–1975 recession

The 1973–1975 recession or 1970s recession was a period of economic stagnation in much of the Western world (i.e. the United States, Canada, Western Europe, Australia, and New Zealand) during the 1970s, putting an end to the overall post–W ...

,

Early work in government (1977–1986)

In January 1977, incumbent Democratic U.S. Congressman

In January 1977, incumbent Democratic U.S. Congressman Andrew Young

Andrew Jackson Young Jr. (born March 12, 1932) is an American politician, diplomat, and activist. Beginning his career as a pastor, Young was an early leader in the civil rights movement, serving as executive director of the Southern Christia ...

of Georgia's 5th congressional district resigned to become the U.S. Ambassador to the U.N. under President Jimmy Carter

James Earl Carter Jr. (October 1, 1924December 29, 2024) was an American politician and humanitarian who served as the 39th president of the United States from 1977 to 1981. A member of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party ...

. In the March 1977 open primary, Atlanta City Council

The Atlanta City Council (formerly the Atlanta Board of Aldermen until 1974) is the main municipal legislative body for the city of Atlanta, Georgia, United States. It consists of 16 members: the council president, twelve members elected from di ...

man Wyche Fowler ranked first with 40% of the vote, failing to reach the 50% threshold to win outright. Lewis ranked second with 29% of the vote.Atlanta City Council

The Atlanta City Council (formerly the Atlanta Board of Aldermen until 1974) is the main municipal legislative body for the city of Atlanta, Georgia, United States. It consists of 16 members: the council president, twelve members elected from di ...

. He won with 69% of the vote, and served on the council until 1986.

U.S. House of Representatives

Elections

1986

After nine years as a member of the

After nine years as a member of the U.S. House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives is a chamber of the bicameral United States Congress; it is the lower house, with the U.S. Senate being the upper house. Together, the House and Senate have the authority under Article One of th ...

, Wyche Fowler gave up the seat to make a successful run for the U.S. Senate. Lewis decided to run for the 5th district again. In the August Democratic primary, where a victory was considered tantamount to election, State Senator Julian Bond

Horace Julian Bond (January 14, 1940 – August 15, 2015) was an American social activist, leader of the civil rights movement, politician, professor, and writer. While he was a student at Morehouse College in Atlanta, Georgia, during the ea ...

ranked first with 47%, just three points shy of winning outright. Lewis finished in second place with 35%. In the run-off, Lewis pulled an upset against Bond, defeating him 52% to 48%.cocaine

Cocaine is a tropane alkaloid and central nervous system stimulant, derived primarily from the leaves of two South American coca plants, ''Erythroxylum coca'' and ''Erythroxylum novogranatense, E. novogranatense'', which are cultivated a ...

, and suggesting that Bond had lied about his civil rights activism.

1988–2018

Lewis was reelected 18 times, dropping below 70 percent of the vote in the general election only once in 1994, when he defeated Republican Dale Dixon by a 38-point margin, 69%–31%. He ran unopposed in 1996, 2004,

Tenure

Overview

Lewis represented Georgia's 5th congressional district, one of the most consistently Democratic districts in the nation. Since its formalization in 1845, the district has been represented by a Democrat for most of its history.

Lewis was one of the most liberal congressmen to have represented a district in the Deep South. He was categorized as a "Hard-Core Liberal" by On the Issues

On the Issues or OnTheIssues is an American non-partisan, non-profit organization providing information to American voters on American candidates, primarily via their website. The organization was started in 1996, went non-profit in 2000, and is ...

.The Washington Post

''The Washington Post'', locally known as ''The'' ''Post'' and, informally, ''WaPo'' or ''WP'', is an American daily newspaper published in Washington, D.C., the national capital. It is the most widely circulated newspaper in the Washington m ...

'' described Lewis in 1998 as "a fiercely partisan Democrat but ... also fiercely independent".The Atlanta Journal-Constitution

''The Atlanta Journal-Constitution'' (''AJC'') is an American daily newspaper based in metropolitan area of Atlanta, Georgia. It is the flagship publication of Cox Enterprises. The ''Atlanta Journal-Constitution'' is the result of the merger ...

'' said Lewis was the "only former major civil rights leader who extended his fight for human rights and racial reconciliation to the halls of Congress".The Atlanta Journal-Constitution

''The Atlanta Journal-Constitution'' (''AJC'') is an American daily newspaper based in metropolitan area of Atlanta, Georgia. It is the flagship publication of Cox Enterprises. The ''Atlanta Journal-Constitution'' is the result of the merger ...

'' also said that to "those who know him, from U.S. senators to 20-something congressional aides", he is called the "conscience of Congress".gay rights

Rights affecting lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer (LGBTQ) people vary greatly by country or jurisdiction—encompassing everything from the legal recognition of same-sex marriage to the death penalty for homosexuality.

Not ...

and national health insurance

National health insurance (NHI), sometimes called statutory health insurance (SHI), is a system of health insurance that insures a national population against the costs of health care. It may be administered by the public sector, the private sector ...

.Gulf War

, combatant2 =

, commander1 =

, commander2 =

, strength1 = Over 950,000 soldiers3,113 tanks1,800 aircraft2,200 artillery systems

, page = https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/GAOREPORTS-PEMD-96- ...

, and the 2000 U.S. trade agreement with China that passed the House. He opposed the Clinton administration

Bill Clinton's tenure as the 42nd president of the United States began with his first inauguration on January 20, 1993, and ended on January 20, 2001. Clinton, a Democrat from Arkansas, took office following his victory over Republican in ...

on NAFTA and welfare reform.Operation Uphold Democracy

Operation Uphold Democracy was a multinational military intervention designed to remove the military regime led and installed by Raoul Cédras after the 1991 Haitian coup d'état overthrew the elected President Jean-Bertrand Aristide. The op ...

, calling the operation a "mission of peace". In 1998, when Clinton was considering a military strike against Iraq, Lewis said he would back the president if American forces were ordered into action. In 2001, three days after the September 11 attacks

The September 11 attacks, also known as 9/11, were four coordinated Islamist terrorist suicide attacks by al-Qaeda against the United States in 2001. Nineteen terrorists hijacked four commercial airliners, crashing the first two into ...

, Lewis voted to give President George W. Bush

George Walker Bush (born July 6, 1946) is an American politician and businessman who was the 43rd president of the United States from 2001 to 2009. A member of the Bush family and the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party, he i ...

authority to use force against the perpetrators of 9/11 in a vote that was 420–1; Lewis called it probably one of his toughest votes.Iraq War

The Iraq War (), also referred to as the Second Gulf War, was a prolonged conflict in Iraq lasting from 2003 to 2011. It began with 2003 invasion of Iraq, the invasion by a Multi-National Force – Iraq, United States-led coalition, which ...

.Associated Press

The Associated Press (AP) is an American not-for-profit organization, not-for-profit news agency headquartered in New York City.

Founded in 1846, it operates as a cooperative, unincorporated association, and produces news reports that are dist ...

said he was "the first major House figure to suggest impeaching George W. Bush", arguing that the president "deliberately, systematically violated the law" in authorizing the National Security Agency

The National Security Agency (NSA) is an intelligence agency of the United States Department of Defense, under the authority of the director of national intelligence (DNI). The NSA is responsible for global monitoring, collection, and proces ...

to conduct wiretaps without a warrant. Lewis said, "He is not king, he is president."Libya

Libya, officially the State of Libya, is a country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It borders the Mediterranean Sea to the north, Egypt to Egypt–Libya border, the east, Sudan to Libya–Sudan border, the southeast, Chad to Chad–L ...

. Lewis voted against the resolution.

In a 2002 op-ed, Lewis mentioned a response by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. to an anti-Zionist

Anti-Zionism is opposition to Zionism. Although anti-Zionism is a heterogeneous phenomenon, all its proponents agree that the creation of the State of Israel in 1948, and the movement to create a sovereign Jewish state in the Palestine (region) ...

student at a 1967 Harvard meeting, quoting "When people criticize Zionists they mean Jews, you are talking anti-Semitism

Antisemitism or Jew-hatred is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who harbours it is called an antisemite. Whether antisemitism is considered a form of racism depends on the school of thought. Antisemi ...

." In describing the special relationship between African Americans and American Jews in working for liberation and peace, he also gave other statements by King to the same effect, including one from March 25, 1968: "Peace for Israel means security, and we must stand with all our might to protect its right to exist, its territorial integrity. I see Israel as one of the great outposts of democracy in the world, and a marvelous example of what can be done, how desert land can be transformed into an oasis of brotherhood and democracy. Peace for Israel means security and that security must be a reality."

Lewis "strongly disagreed" with the movement for Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions

Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions (BDS) is a nonviolent Palestinian-led movement promoting boycotts, divestments, and economic sanctions against Israel. Its objective is to pressure Israel to meet what the BDS movement describes as Israel's ...

(BDS) against Israel and co-sponsored a resolution condemning the pro-Palestinian group, but he supported Representatives Ilhan Omar and Rashida Tlaib

Rashida Harbi Tlaib ( ; born July 24, 1976) is an American lawyer and politician serving as a U.S. representative from Michigan since 2019, representing the state's 12th congressional district since 2023. A member of the Democratic Party, sh ...

's House resolution opposing U.S. anti-boycott legislation banning the boycott of Israel. He explained his support as "a simple demonstration of my ongoing commitment to the ability of every American to exercise the fundamental First Amendment

First most commonly refers to:

* First, the ordinal form of the number 1

First or 1st may also refer to:

Acronyms

* Faint Images of the Radio Sky at Twenty-Centimeters, an astronomical survey carried out by the Very Large Array

* Far Infrared a ...

right to protest through nonviolent actions".

Protests

In January 2001, Lewis boycotted the inauguration of George W. Bush by staying in his Atlanta

Atlanta ( ) is the List of capitals in the United States, capital and List of municipalities in Georgia (U.S. state), most populous city in the U.S. state of Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia. It is the county seat, seat of Fulton County, Georg ...

district. He did not attend the swearing-in because he did not believe Bush was the true elected president. Later, Lewis joined 30 other House Democrats who voted to not count the 20 electoral votes from Ohio

Ohio ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. It borders Lake Erie to the north, Pennsylvania to the east, West Virginia to the southeast, Kentucky to the southwest, Indiana to the ...

in the 2004 presidential election.

In March 2003, Lewis spoke to a crowd of 30,000 in Oregon during an anti-war protest before the start of the Iraq War

The Iraq War (), also referred to as the Second Gulf War, was a prolonged conflict in Iraq lasting from 2003 to 2011. It began with 2003 invasion of Iraq, the invasion by a Multi-National Force – Iraq, United States-led coalition, which ...

. In 2006 and 2009 he was arrested for protesting against the genocide in Darfur outside the Sudanese embassy. He was one of eight U.S. Representatives, from six states, arrested while holding a sit-in near the west side of the U.S. Capitol building, to advocate for immigration reform.

2008 presidential election

At first, Lewis supported Hillary Clinton

Hillary Diane Rodham Clinton ( Rodham; born October 26, 1947) is an American politician, lawyer and diplomat. She was the 67th United States secretary of state in the administration of Barack Obama from 2009 to 2013, a U.S. senator represent ...

, endorsing her presidential campaign on October 12, 2007.superdelegate

In American politics, a superdelegate is a delegate to a presidential nominating convention who is seated automatically.

In Democratic National Conventions, superdelegates—described in formal party rules as the party leaders and electe ...

vote for Barack Obama

Barack Hussein Obama II (born August 4, 1961) is an American politician who was the 44th president of the United States from 2009 to 2017. A member of the Democratic Party, he was the first African American president in American history. O ...

: "Something is happening in America and people are prepared and ready to make that great leap."Politico

''Politico'' (stylized in all caps), known originally as ''The Politico'', is an American political digital newspaper company founded by American banker and media executive Robert Allbritton in 2007. It covers politics and policy in the Unit ...

'' said that "it would be a seminal moment in the race if John Lewis were to switch sides."

On February 27, 2008, Lewis formally changed his support and endorsed Obama.John McCain

John Sidney McCain III (August 29, 1936 – August 25, 2018) was an American statesman and United States Navy, naval officer who represented the Arizona, state of Arizona in United States Congress, Congress for over 35 years, first as ...

and his running mate Sarah Palin

Sarah Louise Palin (; Heath; born February 11, 1964) is an American politician, commentator, and author who served as the ninth governor of Alaska from 2006 until her resignation in 2009. She was the 2008 Republican vice presidential nomi ...

and accusing them of "sowing the seeds of hatred and division" in a way that brought to mind the late Gov. George Wallace

George Corley Wallace Jr. (August 25, 1919 – September 13, 1998) was an American politician who was the 45th and longest-serving governor of Alabama (1963–1967; 1971–1979; 1983–1987), and the List of longest-serving governors of U.S. s ...

and "another destructive period" in American political history. McCain said he was "saddened" by the criticism from "a man I've always admired", and called on Obama to repudiate Lewis's statement. Obama responded to the statement, saying that he "does not believe that John McCain or his policy criticism is in any way comparable to George Wallace or his segregationist

Racial segregation is the separation of people into racial or other ethnic groups in daily life. Segregation can involve the spatial separation of the races, and mandatory use of different institutions, such as schools and hospitals by peopl ...

policies".

2016 firearm safety legislation sit-in

On June 22, 2016, House Democrats, led by Lewis and Massachusetts Representative Katherine Clark, began a sit-in demanding House Speaker

On June 22, 2016, House Democrats, led by Lewis and Massachusetts Representative Katherine Clark, began a sit-in demanding House Speaker Paul Ryan

Paul Davis Ryan (born January 29, 1970) is an American politician who served as the List of Speakers of the United States House of Representatives, 54th speaker of the United States House of Representatives from 2015 to 2019. A member of the ...

allow a vote on gun-safety legislation in the aftermath of the Orlando nightclub shooting

On , 2016, 29-year-old Omar Mateen shot and killed 49 people and wounded 53 more in a mass shooting at Pulse, a gay nightclub in Orlando, Florida, United States before Orlando Police officers fatally shot him after a three-hour standoff.

I ...

. Speaker ''pro tempore

''Pro tempore'' (), abbreviated ''pro tem'' or ''p.t.'', is a Latin phrase which best translates to 'for the time being' in English. This phrase is often used to describe a person who acts as a '' locum tenens'' ('placeholder'). The phrase is ...

'' Daniel Webster

Daniel Webster (January 18, 1782 – October 24, 1852) was an American lawyer and statesman who represented New Hampshire and Massachusetts in the U.S. Congress and served as the 14th and 19th United States Secretary of State, U.S. secretary o ...

ordered the House into recess, but Democrats refused to leave the chamber for nearly 26 hours.

National African American Museum

In 1988, the year after he was sworn into Congress, Lewis introduced a bill to create a national African American museum in Washington. The bill failed, and for 15 years he continued to introduce it with each new Congress. Each time it was blocked in the Senate, most often by conservative Southern Senator Jesse Helms

Jesse Alexander Helms Jr. (October 18, 1921 – July 4, 2008) was an American politician. A leader in the Conservatism in the United States, conservative movement, he served as a senator from North Carolina from 1973 to 2003. As chairman of the ...

. In 2003, Helms retired. The bill won bipartisan support, and President George W. Bush signed the bill to establish the museum, with the Smithsonian's Board of Regents to establish the location. The National Museum of African American History and Culture, located adjacent to the Washington Monument

The Washington Monument is an obelisk on the National Mall in Washington, D.C., built to commemorate George Washington, a Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father of the United States, victorious commander-in-chief of the Continen ...

, held its opening ceremony on September 25, 2016.

2016 presidential election

Lewis supported

Lewis supported Hillary Clinton

Hillary Diane Rodham Clinton ( Rodham; born October 26, 1947) is an American politician, lawyer and diplomat. She was the 67th United States secretary of state in the administration of Barack Obama from 2009 to 2013, a U.S. senator represent ...

in the 2016 Democratic presidential primaries against Bernie Sanders

Bernard Sanders (born September8, 1941) is an American politician and activist who is the Seniority in the United States Senate, senior United States Senate, United States senator from the state of Vermont. He is the longest-serving independ ...

. Regarding Sanders' role in the civil rights movement, Lewis remarked "To be very frank, I never saw him, I never met him. I chaired the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee

The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, and later, the Student National Coordinating Committee (SNCC, pronounced ) was the principal channel of student commitment in the United States to the civil rights movement during the 1960s. Emer ...

for three years, from 1963 to 1966. I was involved in sit-ins, in the Freedom Rides

Freedom Riders were civil rights activists who rode interstate buses into the segregated Southern United States in 1961 and subsequent years to challenge the non-enforcement of the United States Supreme Court decisions '' Morgan v. Virginia' ...

, the March on Washington

The March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom (commonly known as the March on Washington or the Great March on Washington) was held in Washington, D.C., on August 28, 1963. The purpose of the march was to advocate for the civil and economic rig ...

, the March from Selma to Montgomery ... but I met Hillary Clinton". Former Congressman and Hawaii Governor Neil Abercrombie

Neil Abercrombie (born June 26, 1938) is an American politician who served as the seventh governor of Hawaii from 2010 to 2014. He is a member of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party.

Born in Buffalo, New York, Abercrombie is a ...

wrote a letter to Lewis expressing his disappointment with Lewis's comments about Sanders. Lewis later clarified his statement, saying "During the late 1950s and 1960s when I was more engaged, anders

Anders is a male name in Scandinavian languages and Fering, Fering North Frisian, an equivalent of the Greek Andreas ("manly") and the English Andrew. It originated from Andres (name), Andres via metathesis (linguistics), metathesis.

In Sweden, A ...

was not there. I did not see him around. I have never seen him in the South. But if he was there, if he was involved someplace, I was not aware of it ... The fact that I did not meet him in the movement does not mean I doubted that Senator Sanders participated in the civil rights movement, neither was I attempting to disparage his activism."

In a January 2016 interview, Lewis compared Donald Trump

Donald John Trump (born June 14, 1946) is an American politician, media personality, and businessman who is the 47th president of the United States. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party, he served as the 45 ...

, then the Republican front-runner for the presidential nomination, to former Alabama Governor George Wallace

George Corley Wallace Jr. (August 25, 1919 – September 13, 1998) was an American politician who was the 45th and longest-serving governor of Alabama (1963–1967; 1971–1979; 1983–1987), and the List of longest-serving governors of U.S. s ...

: "I've been around a while and Trump reminds me so much of a lot of the things that George Wallace said and did. I think demagogues are pretty dangerous, really ... We shouldn't divide people, we shouldn't separate people."NBC

The National Broadcasting Company (NBC) is an American commercial broadcast television and radio network serving as the flagship property of the NBC Entertainment division of NBCUniversal, a subsidiary of Comcast. It is one of NBCUniversal's ...

's Chuck Todd

Charles David Todd (born April 8, 1972) is an American television journalist who was the 12th moderator of NBC's ''Meet the Press''. During his time at NBC News between 2007 and 2025, Todd also hosted ''Meet the Press Now'', its daily edition ...

for ''Meet the Press

''Meet the Press'' is a weekly American television Sunday morning talk show broadcast on NBC. It is the List of longest-running television shows by category, longest-running program on American television, though its format has changed since th ...

'', Lewis stated: "I don't see the president-elect as a legitimate president." He added, "I think the Russians participated in having this man get elected, and they helped destroy the candidacy of Hillary Clinton. I don't plan to attend the inauguration

In government and politics, inauguration is the process of swearing a person into office and thus making that person the incumbent. Such an inauguration commonly occurs through a formal ceremony or special event, which may also include an inau ...

. I think there was a conspiracy on the part of the Russians, and others, that helped him get elected. That's not right. That's not fair. That's not the open, democratic process." Trump replied on Twitter the following day, suggesting that Lewis should "spend more time on fixing and helping his district, which is in horrible shape and falling apart (not to ..mention crime infested) rather than falsely complaining about the election results", and accusing Lewis of being "All talk, talk, talk – no action or results. Sad!" Trump's statement about Lewis's district was rated as "Mostly False" by PolitiFact

PolitiFact.com is an American nonprofit project operated by the Poynter Institute in St. Petersburg, Florida, with offices there and in Washington, D.C. It began in 2007 as a project of the ''Tampa Bay Times'' (then the ''St. Petersburg Times ...

, and he was criticized for attacking a civil rights leader such as Lewis, especially one who was brutally beaten for the cause, and especially on Martin Luther King weekend.John McCain

John Sidney McCain III (August 29, 1936 – August 25, 2018) was an American statesman and United States Navy, naval officer who represented the Arizona, state of Arizona in United States Congress, Congress for over 35 years, first as ...

acknowledged Lewis as "an American hero" but criticized him, saying: "this is not the first time that Congressman Lewis has taken a very extreme stand and condemned without any shred of evidence for doing so an incoming president of the United States. This is a stain on Congressman Lewis's reputation – no one else's."

A few days later, Lewis said that he would not attend Trump's inauguration because he did not believe that Trump was the true elected president. "It will be the first (inauguration) that I miss since I've been in Congress. You cannot be at home with something that you feel that is wrong, is not right", he said. Lewis had failed to attend George W. Bush's inauguration in 2001 because he believed that he too was not a legitimately elected president. Lewis's statement was rated as "Pants on Fire" by PolitiFact.

2020 presidential election

Lewis endorsed Joe Biden

Joseph Robinette Biden Jr. (born November 20, 1942) is an American politician who was the 46th president of the United States from 2021 to 2025. A member of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, he served as the 47th vice p ...

for president on April 7, 2020, a day before Biden effectively secured the Democratic nomination. He recommended Biden pick a woman of color as his running mate.

Committee assignments

Lewis served on the following Congressional committees at the time of his death:

* Committee on Ways and Means

** Subcommittee on Oversight (Chair)

* United States Congress Joint Committee on Taxation

The Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) is a Committee of the U.S. Congress established under the Internal Revenue Code at .

Structure

The Joint Committee is composed of ten Members: five from the Senate Finance Committee and five from the House ...

Caucus memberships

Lewis was a member of over 40 caucuses, including:Congressional Black Caucus

The Congressional Black Caucus (CBC) is made up of Black members of the United States Congress. Representative Yvette Clarke from New York, the current chairperson, succeeded Steven Horsford from Nevada in 2025. Although most members belong ...

* Congressional Progressive Caucus

* Congressional Brazil Caucuswhip

A whip is a blunt weapon or implement used in a striking motion to create sound or pain. Whips can be used for flagellation against humans or animals to exert control through pain compliance or fear of pain, or be used as an audible cue thro ...

in the Democratic caucus.

Biographies

Lewis's 1998 autobiography ''Walking with the Wind: A Memoir of the Movement'', co-written with Mike D'Orso, won the Robert F. Kennedy Book Award, the Anisfield-Wolf Book Award, the Christopher Award

The Christopher Award (established 1949) is presented to the producers, directors, and writers of books, films and television specials that "affirm the highest values of the human spirit". It is given by The Christophers, a Christian organizatio ...

and the Lillian Smith Book Award. It appeared on numerous bestseller lists, was selected as a ''New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''NYT'') is an American daily newspaper based in New York City. ''The New York Times'' covers domestic, national, and international news, and publishes opinion pieces, investigative reports, and reviews. As one of ...

'' Notable Book of the Year, was named by the American Library Association

The American Library Association (ALA) is a nonprofit organization based in the United States that promotes libraries and library education internationally. It is the oldest and largest library association in the world.

History 19th century ...

as its Nonfiction Book of the Year, and was included among ''Newsweek

''Newsweek'' is an American weekly news magazine based in New York City. Founded as a weekly print magazine in 1933, it was widely distributed during the 20th century and has had many notable editors-in-chief. It is currently co-owned by Dev P ...

'' magazine's 2009 list of "50 Books For Our Times". It was critically acclaimed, with ''The Washington Post

''The Washington Post'', locally known as ''The'' ''Post'' and, informally, ''WaPo'' or ''WP'', is an American daily newspaper published in Washington, D.C., the national capital. It is the most widely circulated newspaper in the Washington m ...

'' calling it "the definitive account of the civil rights movement" and the ''Los Angeles Times

The ''Los Angeles Times'' is an American Newspaper#Daily, daily newspaper that began publishing in Los Angeles, California, in 1881. Based in the Greater Los Angeles city of El Segundo, California, El Segundo since 2018, it is the List of new ...

'' proclaiming it "destined to become a classic in civil rights literature".

His life is also the subject of a 2002 book for young people, ''John Lewis: From Freedom Rider to Congressman''. In 2012, Lewis released ''Across That Bridge'', written with Brenda Jones, to mixed reviews. ''Publishers Weekly

''Publishers Weekly'' (''PW'') is an American weekly trade news magazine targeted at publishers, librarians, booksellers, and literary agents. Published continuously since 1872, it has carried the tagline, "The International News Magazine of ...

''s review said, "At its best, the book provides a testament to the power of nonviolence in social movements ... At its worst, it resembles an extended campaign speech."

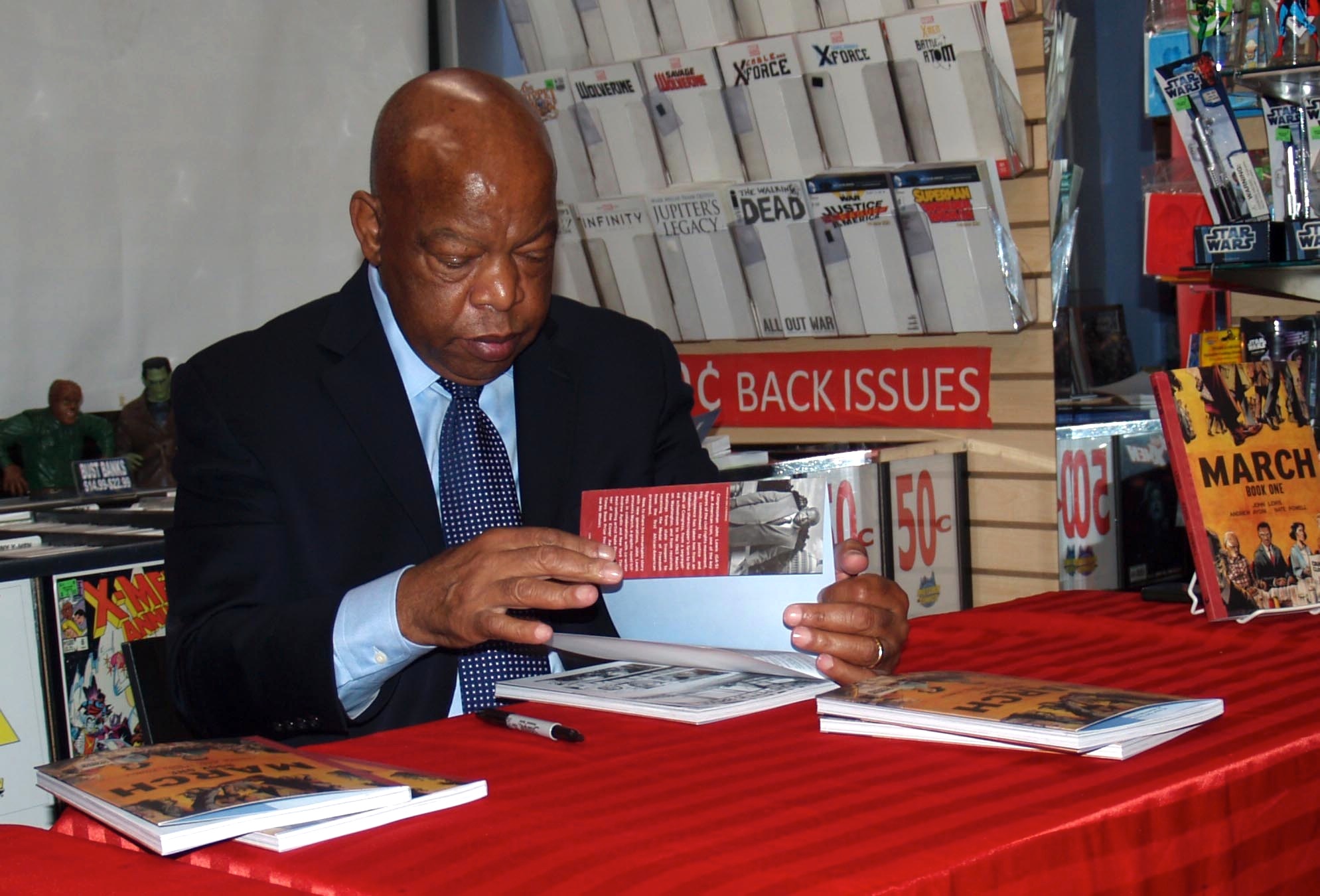

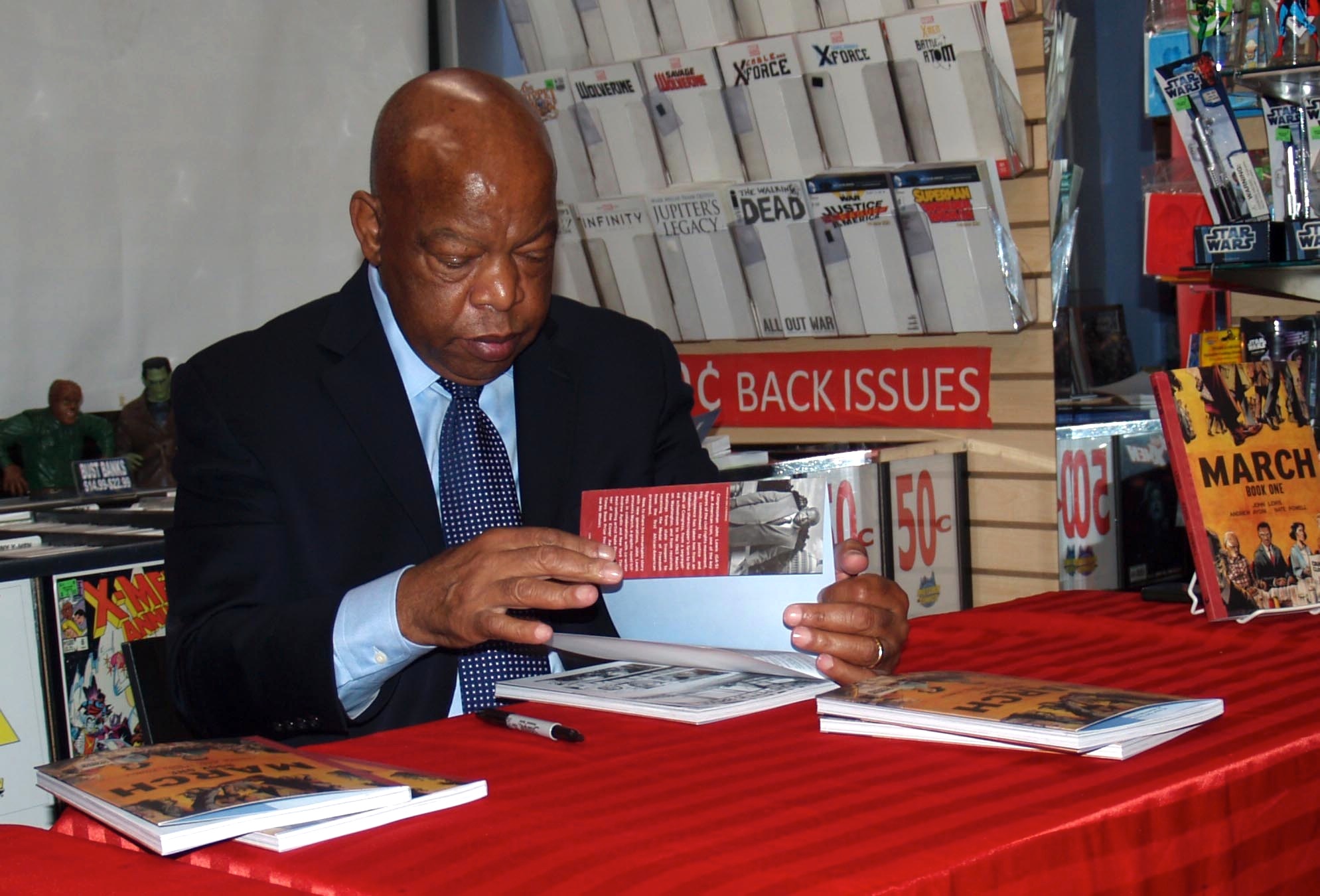

''March'' (2013)

In 2013, Lewis became the first member of Congress to write a

In 2013, Lewis became the first member of Congress to write a graphic novel

A graphic novel is a self-contained, book-length form of sequential art. The term ''graphic novel'' is often applied broadly, including fiction, non-fiction, and Anthology, anthologized work, though this practice is highly contested by comics sc ...

, with the launch of a trilogy titled ''March

March is the third month of the year in both the Julian and Gregorian calendars. Its length is 31 days. In the Northern Hemisphere, the meteorological beginning of spring occurs on the first day of March. The March equinox on the 20 or 2 ...

''. The ''March'' trilogy is a black and white comics trilogy about the Civil Rights Movement, told through the perspective of civil rights leader and U.S. Congressman John Lewis. The first volume, ''March: Book One'' is written by Lewis and Andrew Aydin, illustrated and lettered by Nate Powell and was published in August 2013,New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''NYT'') is an American daily newspaper based in New York City. ''The New York Times'' covers domestic, national, and international news, and publishes opinion pieces, investigative reports, and reviews. As one of ...

'' bestseller for graphic novels and spent more than a year on the lists.

''March: Book One'' received an "Author Honor" from the American Library Association

The American Library Association (ALA) is a nonprofit organization based in the United States that promotes libraries and library education internationally. It is the oldest and largest library association in the world.

History 19th century ...

's 2014 Coretta Scott King Book Awards, which honors an African American author of a children's book. ''Book One'' also became the first graphic novel to win a Robert F. Kennedy Book Award, receiving a "Special Recognition" bust in 2014.

''March: Book One'' was selected by first-year reading programs in 2014 at Michigan State University

Michigan State University (Michigan State or MSU) is a public university, public Land-grant university, land-grant research university in East Lansing, Michigan, United States. It was founded in 1855 as the Agricultural College of the State o ...

, Georgia State University

Georgia State University (Georgia State, State, or GSU) is a Public university, public research university in Atlanta, Georgia, United States. Founded in 1913, it is one of the University System of Georgia's four research universities. It is al ...

, and Marquette University

Marquette University () is a Private university, private Jesuit research university in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, United States. It was established as Marquette College on August 28, 1881, by John Henni, the first Archbishop of the Roman Catholic Ar ...

.

''March: Book Two'' was released in 2015 and immediately became both a ''New York Times'' and ''Washington Post'' bestseller for graphic novels.

The release of ''March: Book Three'' in August 2016 brought all three volumes into the top 3 slots of the ''New York Times'' bestseller list for graphic novels for 6 consecutive weeks. The third volume was announced as the recipient of the 2017 Printz Award for excellence in young-adult literature, the Coretta Scott King Award, the YALSA Award for Excellence in Nonfiction, the 2016 National Book Award

The National Book Awards (NBA) are a set of annual U.S. literary awards. At the final National Book Awards Ceremony every November, the National Book Foundation presents the National Book Awards and two lifetime achievement awards to authors. ...

in Young People's Literature, and the Sibert Medal

The Robert F. Sibert Informational Book Medal established by the Association for Library Service to Children in 2001 with support from Bound to Stay Bound Books, Inc., is awarded annually to the writer and illustrator of the most distinguished in ...

at the American Library Association

The American Library Association (ALA) is a nonprofit organization based in the United States that promotes libraries and library education internationally. It is the oldest and largest library association in the world.

History 19th century ...

's annual Midwinter Meeting in January 2017.

The ''March'' trilogy received the Carter G. Woodson Book Award in the Secondary (grades 7–12) category in 2017.

''Run'' (2018)

In 2018, Lewis and Andrew Aydin co-wrote another graphic novel as a sequel to the ''March'' series entitled ''Run'', which documents Lewis's life after the passage of the Civil Rights Act. The authors teamed with illustrator Afua Richardson for the book, which was originally scheduled to be released in August 2018, but was later rescheduled. It was released on August 3, 2021, a year after his death, as it was one of his last endeavours before he died. Nate Powell, who illustrated ''March'', also contributed to the art.

Personal life

Marriage and family

Lewis met his future wife Lillian Miles at a New Year's Eve party hosted by Xernona Clayton. Lillian worked for the library of Atlanta University at the time. The two of them married one year later in 1968. In 1976, they had a son, who also works in politics. Lillian died on December 31, 2012, their 45th marriage anniversary

He has a grandson who lives in Paris.

Illness and death

On December 29, 2019, Lewis announced that he had been diagnosed with stage IV pancreatic cancer

Pancreatic cancer arises when cell (biology), cells in the pancreas, a glandular organ behind the stomach, begin to multiply out of control and form a Neoplasm, mass. These cancerous cells have the malignant, ability to invade other parts of ...

. He remained in the Washington D.C. area for his treatment. Lewis stated: "I have been in some kind of fight – for freedom, equality, basic human rights – for nearly my entire life. I have never faced a fight quite like the one I have now."

On July 17, 2020, Lewis died in Atlanta

Atlanta ( ) is the List of capitals in the United States, capital and List of municipalities in Georgia (U.S. state), most populous city in the U.S. state of Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia. It is the county seat, seat of Fulton County, Georg ...

at the age of 80, on the same day in the same city as his friend and fellow civil rights activist C.T. Vivian. Lewis had been the final surviving "Big Six" civil rights icon.

Then-president Donald Trump

Donald John Trump (born June 14, 1946) is an American politician, media personality, and businessman who is the 47th president of the United States. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party, he served as the 45 ...

ordered all flags to be flown at half-staff

Half-mast or half-staff (American English) refers to a flag flying below the summit of a ship mast, a pole on land, or a pole on a building. In many countries this is seen as a symbol of respect, mourning, distress, or, in some cases, a sal ...

in response to Lewis's death. Condolences also came from the international community, with Swedish Prime Minister Stefan Löfven, French President Emmanuel Macron

Emmanuel Jean-Michel Frédéric Macron (; born 21 December 1977) is a French politician who has served as President of France and Co-Prince of Andorra since 2017. He was Ministry of Economy and Finance (France), Minister of Economics, Industr ...

, Irish President Michael D. Higgins among others, all memorializing Lewis.

Funeral services

Public ceremonies honoring Lewis began in his hometown of Troy, Alabama

Troy is a city in and the county seat of Pike County, Alabama, United States. It was formally incorporated on February 4, 1843.

Between 1763 and 1783, the area where Troy sits was part of the colony of British West Florida.The Economy of Bri ...

at Troy University, which had denied him admission in 1957 due to racial segregation

Racial segregation is the separation of people into race (human classification), racial or other Ethnicity, ethnic groups in daily life. Segregation can involve the spatial separation of the races, and mandatory use of different institutions, ...

. His casket was then taken for a memorial held at the historic Brown Chapel AME Church in Selma, Alabama

Selma is a city in and the county seat of Dallas County, in the Black Belt region of south central Alabama and extending to the west. Located on the banks of the Alabama River, the city has a population of 17,971 as of the 2020 census. Abou ...

. Calls to rename the Edmund Pettus Bridge

The Edmund Pettus Bridge carries U.S. Route 80 Business (Selma, Alabama), U.S. Route 80 Business (US 80 Bus.) across the Alabama River in Selma, Alabama, United States. Built in 1940, it is named after Edmund Pettus, a former Confeder ...

in Selma, in Lewis's honor grew after his death. On July 26, 2020, his casket, carried in a horse-drawn caisson, traveled the same route over the bridge that he walked during the Bloody Sunday march from Selma to Montgomery, before his lying in state

Lying in state is the tradition in which the body of a deceased official, such as a head of state, is placed in a state building, either outside or inside a coffin, to allow the public to pay their respects. It traditionally takes place in a ...

at the Alabama State Capitol in Montgomery.

United States House of Representatives Speaker Nancy Pelosi

Nancy Patricia Pelosi ( ; ; born March 26, 1940) is an American politician who was the List of Speakers of the United States House of Representatives, 52nd speaker of the United States House of Representatives, serving from 2007 to 2011 an ...

and Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell

Addison Mitchell McConnell III (; born February 20, 1942) is an American politician and attorney serving as the senior United States senator from Kentucky, a seat he has held since 1985. McConnell is in his seventh Senate term and is the long ...

announced that Lewis would lie in state in the United States Capitol Rotunda on July 27 and 28, with a public viewing and procession through Washington, D.C. He is the first African-American lawmaker to be so honored in the Rotunda; in October 2019 his colleague, representative Elijah Cummings

Elijah Eugene Cummings (January 18, 1951October 17, 2019) was an American politician and civil rights advocate who served in the United States House of Representatives for from 1996 until his death in 2019, when he was succeeded by his predecess ...

, lay in state in the Capitol Statuary Hall. Health concerns related to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic (also known as the coronavirus pandemic and COVID pandemic), caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), began with an disease outbreak, outbreak of COVID-19 in Wuhan, China, in December ...

led to a decision to have his casket displayed outdoors on the East Front steps during the public viewing hours, rather than the usual line of people in the Rotunda filing past the casket to pay their respects. On July 29, 2020, Lewis's casket left the U.S. Capitol and was transported back to Atlanta, Georgia, where he lay in state at the Georgia State Capitol

The Georgia State Capitol is an architecturally and historically significant building in Atlanta, Georgia, United States. The building has been named a National Historic Landmark which is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. As t ...

.

Among the distinguished speakers at his final funeral service at Atlanta's Ebenezer Baptist Church were former U.S. Presidents Bill Clinton

William Jefferson Clinton (né Blythe III; born August 19, 1946) is an American politician and lawyer who was the 42nd president of the United States from 1993 to 2001. A member of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, ...

, George W. Bush

George Walker Bush (born July 6, 1946) is an American politician and businessman who was the 43rd president of the United States from 2001 to 2009. A member of the Bush family and the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party, he i ...

, and Barack Obama

Barack Hussein Obama II (born August 4, 1961) is an American politician who was the 44th president of the United States from 2009 to 2017. A member of the Democratic Party, he was the first African American president in American history. O ...

, who gave the eulogy. Former President Jimmy Carter

James Earl Carter Jr. (October 1, 1924December 29, 2024) was an American politician and humanitarian who served as the 39th president of the United States from 1977 to 1981. A member of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party ...

, unable to travel during the COVID-19 pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic (also known as the coronavirus pandemic and COVID pandemic), caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), began with an disease outbreak, outbreak of COVID-19 in Wuhan, China, in December ...

due to his advanced age, sent a statement to be read during the service. The then-current President Donald Trump

Donald John Trump (born June 14, 1946) is an American politician, media personality, and businessman who is the 47th president of the United States. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party, he served as the 45 ...

did not attend the service. Lewis was buried at Atlanta's historic South-View Cemetery.

Lewis penned an op-ed to the nation that was published in ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''NYT'') is an American daily newspaper based in New York City. ''The New York Times'' covers domestic, national, and international news, and publishes opinion pieces, investigative reports, and reviews. As one of ...

'' on the day of his funeral. In it, he called on the younger generation to continue the work for justice and an end to hate.

Honors

Lewis was honored by having the 1997 sculpture by Thornton Dial, '' The Bridge'', placed at Ponce de Leon Avenue and

Lewis was honored by having the 1997 sculpture by Thornton Dial, '' The Bridge'', placed at Ponce de Leon Avenue and Freedom Park

In the Philippines, a freedom park is a centrally located public space where political gatherings, rallies and demonstrations may be held without the need of prior permission from government authorities. Similar to free speech zones in the United ...

, Atlanta, dedicated to him by the artist. In 1999, Lewis was awarded the Wallenberg Medal from the University of Michigan

The University of Michigan (U-M, U of M, or Michigan) is a public university, public research university in Ann Arbor, Michigan, United States. Founded in 1817, it is the oldest institution of higher education in the state. The University of Mi ...

in recognition of his courageous lifelong commitment to the defense of civil and human rights. In that same year, he received the Four Freedoms Award for the Freedom of Speech.

In 2001, the John F. Kennedy Library Foundation awarded Lewis the Profile in Courage Award

The Profile in Courage Award is a private award created by the Kennedy family to recognize displays of courage similar to those John F. Kennedy originally described in his book of the same name. It is given to individuals (often elected offici ...

"for his extraordinary courage, leadership and commitment to civil rights". It is a lifetime achievement award and has been given out only twice, John Lewis and William Winter (in 2008). The next year he was awarded the Spingarn Medal

The Spingarn Medal is awarded annually by the NAACP, National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) for an outstanding achievement by an African Americans, African American. The award was created in 1914 by Joel Elias Spingarn, ...

from the NAACP

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) is an American civil rights organization formed in 1909 as an interracial endeavor to advance justice for African Americans by a group including W. E. B. Du&nbs ...

.

In 2004, Lewis received the Golden Plate Award of the American Academy of Achievement

The American Academy of Achievement, colloquially known as the Academy of Achievement, is a nonprofit educational organization that recognizes some of the highest-achieving people in diverse fields and gives them the opportunity to meet one ano ...

presented by Awards Council member James Earl Jones.

In 2006, he received the U.S. Senator John Heinz

Henry John Heinz III (October 23, 1938 – April 4, 1991) was an American businessman and politician who served as a United States Senate, United States senator from Pennsylvania from 1977 until Merion air disaster, his death in 1991. An he ...

Award for Greatest Public Service by an Elected or Appointed Official, an award given out annually by Jefferson Awards for Public Service. In September 2007, Lewis was awarded the Dole Leadership Prize from the Robert J. Dole Institute of Politics at the University of Kansas

The University of Kansas (KU) is a public research university with its main campus in Lawrence, Kansas, United States. Two branch campuses are in the Kansas City metropolitan area on the Kansas side: the university's medical school and hospital ...

.March on Washington

The March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom (commonly known as the March on Washington or the Great March on Washington) was held in Washington, D.C., on August 28, 1963. The purpose of the march was to advocate for the civil and economic rig ...

present on the stage during the inauguration of Barack Obama. Obama signed a commemorative photograph for Lewis with the words, "Because of you, John. Barack Obama."[

In 2010, Lewis was awarded the First LBJ Liberty and Justice for All Award, given to him by the Lyndon Baines Johnson Foundation,]Presidential Medal of Freedom

The Presidential Medal of Freedom is the highest civilian award of the United States, alongside the Congressional Gold Medal. It is an award bestowed by decision of the president of the United States to "any person recommended to the President ...

by President Barack Obama

Barack Hussein Obama II (born August 4, 1961) is an American politician who was the 44th president of the United States from 2009 to 2017. A member of the Democratic Party, he was the first African American president in American history. O ...

. In 2016, it was announced that a future

In 2016, it was announced that a future United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the naval warfare, maritime military branch, service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is the world's most powerful navy with the largest Displacement (ship), displacement, at 4.5 millio ...

underway replenishment oiler would be named . Also in 2016, Lewis and fellow Selma marcher Frederick Reese accepted Congressional Gold Medal

The Congressional Gold Medal is the oldest and highest civilian award in the United States, alongside the Presidential Medal of Freedom. It is bestowed by vote of the United States Congress, signed into law by the president. The Gold Medal exp ...

s which were bestowed to the "foot soldiers" of the Selma marchers. The same year, Lewis was awarded the Liberty Medal at the National Constitution Center. The prestigious award has been awarded to international leaders from Malala Yousafzai

Malala Yousafzai (; , pronunciation: ; born 12 July 1997) is a Pakistani female education activist, film and television producer, and the 2014 Nobel Peace Prize laureate at the age of 17. She is the youngest Nobel Prize laureate in history, ...

to the 14th Dalai Lama

The 14th Dalai Lama (born 6 July 1935; full spiritual name: Jetsun Jamphel Ngawang Lobsang Yeshe Tenzin Gyatso, shortened as Tenzin Gyatso; ) is the incumbent Dalai Lama, the highest spiritual leader and head of Tibetan Buddhism. He served a ...

, presidents George Bush and Bill Clinton and other dignitaries and visionaries. The timing of Lewis's award coincided with the 150th anniversary of the 14th amendment. In 2020, Lewis was awarded the Walter P. Reuther Humanitarian Award by Wayne State University

Wayne State University (WSU) is a public university, public research university in Detroit, Michigan, United States. Founded in 1868, Wayne State consists of 13 schools and colleges offering approximately 375 programs. It is Michigan's third-l ...

, the UAW, and the Reuther family.

Lewis gave numerous commencement addresses, including at the School of Visual Arts

The School of Visual Arts New York City (SVA NYC) is a private for-profit art school in New York City. It was founded in 1947 and is a member of the Association of Independent Colleges of Art and Design.

History

This school was started by Silas ...

(SVA) in 2014,[Herbowy, Greg (Fall 2014). "Q+A: Congressman John Lewis, Andrew Aydin & Nate Powell." '' Visual Arts Journal''. pp. 48–51.] Bates College

Bates College () is a Private college, private Liberal arts colleges in the United States, liberal arts college in Lewiston, Maine. Anchored by the Historic Quad, the campus of Bates totals with a small urban campus which includes 33 Victorian ...

(in Lewiston, Maine

Lewiston (; ) is the List of municipalities in Maine, second most populous city in the U.S. state of Maine, with the city's population at 37,121 as of the 2020 United States census. The city lies halfway between Augusta, Maine, Augusta, the sta ...

) and Washington University in St. Louis in 2016,Bard College

Bard College is a private college, private Liberal arts colleges in the United States, liberal arts college in Annandale-on-Hudson, New York. The campus overlooks the Hudson River and Catskill Mountains within the Hudson River Historic District ...