Prince

A prince is a male ruler (ranked below a king, grand prince, and grand duke) or a male member of a monarch's or former monarch's family. ''Prince'' is also a title of nobility (often highest), often hereditary, in some European states. The ...

, born , was a Japanese statesman who served as the first

prime minister of Japan

The is the head of government of Japan. The prime minister chairs the Cabinet of Japan and has the ability to select and dismiss its ministers of state. The prime minister also serves as the commander-in-chief of the Japan Self-Defense Force ...

from 1885 to 1888, and later from 1892 to 1896, in 1898, and from 1900 to 1901. He was a leading member of the ''

genrō'', a group of senior statesmen that dictated policy during the

Meiji era

The was an Japanese era name, era of History of Japan, Japanese history that extended from October 23, 1868, to July 30, 1912. The Meiji era was the first half of the Empire of Japan, when the Japanese people moved from being an isolated feu ...

.

Born into a poor farming family in the

Chōshū Domain, Itō and his father were adopted into a low-ranking

samurai

The samurai () were members of the warrior class in Japan. They were originally provincial warriors who came from wealthy landowning families who could afford to train their men to be mounted archers. In the 8th century AD, the imperial court d ...

family. After the

opening of Japan in 1854, he joined the nationalist ''

sonnō jōi'' movement before being sent to England to study at

University College London

University College London (Trade name, branded as UCL) is a Public university, public research university in London, England. It is a Member institutions of the University of London, member institution of the Federal university, federal Uni ...

in 1863. Following the

Meiji Restoration

The , referred to at the time as the , and also known as the Meiji Renovation, Revolution, Regeneration, Reform, or Renewal, was a political event that restored Imperial House of Japan, imperial rule to Japan in 1868 under Emperor Meiji. Althoug ...

of 1868, Itō was appointed the junior councilor for foreign affairs in the newly formed

Empire of Japan

The Empire of Japan, also known as the Japanese Empire or Imperial Japan, was the Japanese nation state that existed from the Meiji Restoration on January 3, 1868, until the Constitution of Japan took effect on May 3, 1947. From Japan–Kor ...

. In 1870, he traveled to the

United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

to study Western currency, and subsequently helped establish Japan's taxation system in 1871. Itō then set off on another overseas trip with the

Iwakura Mission

The Iwakura Mission or Iwakura Embassy (, ''Iwakura Shisetsudan'') was a Japanese diplomatic voyage to Europe and the United States conducted between 1871 and 1873 by leading statesmen and scholars of the Meiji period. It was not the only such m ...

to the U.S. and Europe. Upon his return to Japan in 1873, he became a full councilor and public works minister.

During the 1880s, Itō emerged as the ''

de facto'' leader of the

Meiji oligarchy. In 1881, he was officially entrusted with overseeing the drafting of

Japan's first Constitution. After traveling to Europe to study its nations'

political systems

In political science, a political system means the form of Political organisation, political organization that can be observed, recognised or otherwise declared by a society or state (polity), state.

It defines the process for making official gov ...

, Itō settled on adopting a constitution emulating that of Prussia by reserving considerable power with the emperor while limiting political parties' involvement in government. In 1885, he replaced the

Daijō-kan

The , also known as the Great Council of State, was (i) (''Daijō-kan'') the highest organ of Japan's premodern Imperial government under the Ritsuryō legal system during and after the Nara period or (ii) (''Dajō-kan'') the highest organ of Jap ...

with a cabinet composed of ministry heads, and himself took up the new position of prime minister. When a draft of the constitution was prepared in 1888, he established a supra-cabinet Privy Council led by himself to discuss and approve it on the emperor's behalf before having the

Meiji Constitution

The Constitution of the Empire of Japan ( Kyūjitai: ; Shinjitai: , ), known informally as the Meiji Constitution (, ''Meiji Kenpō''), was the constitution of the Empire of Japan which was proclaimed on February 11, 1889, and remained in ...

officially proclaimed in 1899. Even out of office as Japan's

head of government

In the Executive (government), executive branch, the head of government is the highest or the second-highest official of a sovereign state, a federated state, or a self-governing colony, autonomous region, or other government who often presid ...

, Itō continued to wield vast influence over the country's policies as a permanent imperial adviser, or ''genkun'', and as the President of the Emperor's

Privy Council.

On the world stage, Itō Hirobumi presided over an ambitious foreign policy. He strengthened diplomatic ties with the Western powers including

Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

, the

United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

and

especially the

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Northwestern Europe, off the coast of European mainland, the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

. In Asia, he oversaw the

First Sino-Japanese War

The First Sino-Japanese War (25 July 189417 April 1895), or the First China–Japan War, was a conflict between the Qing dynasty of China and the Empire of Japan primarily over influence in Joseon, Korea. In Chinese it is commonly known as th ...

and negotiated the surrender of China's ruling

Qing dynasty

The Qing dynasty ( ), officially the Great Qing, was a Manchu-led Dynasties of China, imperial dynasty of China and an early modern empire in East Asia. The last imperial dynasty in Chinese history, the Qing dynasty was preceded by the ...

on

terms aggressively favourable to Japan, including the

annexation

Annexation, in international law, is the forcible acquisition and assertion of legal title over one state's territory by another state, usually following military occupation of the territory. In current international law, it is generally held t ...

of

Taiwan

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia. The main geography of Taiwan, island of Taiwan, also known as ''Formosa'', lies between the East China Sea, East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocea ...

and the release of

Korea

Korea is a peninsular region in East Asia consisting of the Korean Peninsula, Jeju Island, and smaller islands. Since the end of World War II in 1945, it has been politically Division of Korea, divided at or near the 38th parallel north, 3 ...

from the

Chinese Imperial tribute system. While expanding his country's claims in Asia, Itō sought to avoid conflict with the

Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire that spanned most of northern Eurasia from its establishment in November 1721 until the proclamation of the Russian Republic in September 1917. At its height in the late 19th century, it covered about , roughl ...

through the policy of ''Man-Kan kōkan'' – the proposed surrender of

Manchuria

Manchuria is a historical region in northeast Asia encompassing the entirety of present-day northeast China and parts of the modern-day Russian Far East south of the Uda (Khabarovsk Krai), Uda River and the Tukuringra-Dzhagdy Ranges. The exact ...

to Russia's sphere of influence in exchange for recognition of Japanese

hegemony

Hegemony (, , ) is the political, economic, and military predominance of one State (polity), state over other states, either regional or global.

In Ancient Greece (ca. 8th BC – AD 6th c.), hegemony denoted the politico-military dominance of ...

in Korea. When Itō's attempts at diplomacy failed, Japan's incumbent prime minister,

Katsura Tarō, elected to abandon the pursuit of ''Man-Kan kōkan'' which ultimately resulted in the outbreak of the

Russo-Japanese War

The Russo-Japanese War (8 February 1904 – 5 September 1905) was fought between the Russian Empire and the Empire of Japan over rival imperial ambitions in Manchuria and the Korean Empire. The major land battles of the war were fought on the ...

.

After Japanese forces emerged victorious over Russia, the ensuing

Japan–Korea Treaty of 1905 made Itō the first Japanese

Resident-General

A resident minister, or resident for short, is a government official required to take up permanent residence in another country. A representative of his government, he officially has diplomatic functions which are often seen as a form of in ...

of Korea. He consented to the total annexation of Korea in response to pressure from the increasingly powerful

Imperial Army. Shortly thereafter, he resigned as Resident-General in 1909 and assumed office once again as President of the Imperial Privy Council. Four months later, Itō was assassinated by

Korean-independence activist and

nationalist

Nationalism is an idea or movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the State (polity), state. As a movement, it presupposes the existence and tends to promote the interests of a particular nation,Anthony D. Smith, Smith, A ...

An Jung-geun in

Harbin

Harbin, ; zh, , s=哈尔滨, t=哈爾濱, p=Hā'ěrbīn; IPA: . is the capital of Heilongjiang, China. It is the largest city of Heilongjiang, as well as being the city with the second-largest urban area, urban population (after Shenyang, Lia ...

,

Manchuria

Manchuria is a historical region in northeast Asia encompassing the entirety of present-day northeast China and parts of the modern-day Russian Far East south of the Uda (Khabarovsk Krai), Uda River and the Tukuringra-Dzhagdy Ranges. The exact ...

.

Early life and education

Origins and adoption

Itō Hirobumi was born Hayashi Risuke on 16 October 1841 (

Tenpō 12, 2nd day of the 9th month) in Tsukari village,

Suō Province (present-day

Hikari, Yamaguchi Prefecture), within the

Chōshū Domain. He was the son of Hayashi Jūzō, a farmer of humble origins. His father served a low-ranking

samurai

The samurai () were members of the warrior class in Japan. They were originally provincial warriors who came from wealthy landowning families who could afford to train their men to be mounted archers. In the 8th century AD, the imperial court d ...

named Itō Naoemon in the castle town of

Hagi. When Hirobumi was very young, his father was adopted into the Itō family along with his household, granting them samurai status, albeit at the lowest rank of ''chūgen'' (foot soldier). After the adoption, Risuke's name was changed to Itō Risuke, then Itō Shunsuke in 1858, and finally to Hirobumi around 1869. The name "Hirobumi" (博文), meaning "extensive learning", was reportedly suggested by

Takasugi Shinsaku and derived from ''

The Analects of Confucius''.

Yoshida Shōin and early activism

In 1856, Itō was sent for guard duty in

Sagami Province

was a Provinces of Japan, province of Japan located in what is today the central and western Kanagawa Prefecture.Louis-Frédéric, Nussbaum, Louis-Frédéric. (2005). "''Kanagawa''" at . Sagami Province bordered the provinces of Izu Province, Izu ...

. There, in 1857, Kuruhara Ryōzō, a brother-in-law of

Kido Takayoshi

, formerly known as , was a Japanese statesman, samurai and ''Shishi (Japan), shishi'' who is considered one of the Three Great Nobles of the Restoration, three great nobles who led the Meiji Restoration.

Early life

Born Wada Kogorō on Augu ...

, recognized Itō's potential and encouraged his intellectual pursuits. Later that year, Itō returned to Chōshū and, with Kuruhara's introduction, enrolled in the

Shōka Sonjuku, a private academy run by the influential scholar and activist

Yoshida Shōin. The academy was a crucible for many future leaders of the

Meiji Restoration

The , referred to at the time as the , and also known as the Meiji Renovation, Revolution, Regeneration, Reform, or Renewal, was a political event that restored Imperial House of Japan, imperial rule to Japan in 1868 under Emperor Meiji. Althoug ...

, including Takasugi Shinsaku and

Yamagata Aritomo

Prince was a Japanese politician and general who served as prime minister of Japan from 1889 to 1891, and from 1898 to 1900. He was also a leading member of the '' genrō'', a group of senior courtiers and statesmen who dominated the politics ...

.

Yoshida Shōin's execution in the

Ansei Purge of 1859 profoundly impacted Itō, who, along with Kido Takayoshi and others, retrieved Yoshida's body for burial. Following this, Itō became deeply involved in the radical ''

Sonnō jōi'' (Revere the Emperor, Expel the Barbarians) movement. In 1862, he participated in an unsuccessful plot to assassinate Nagai Uta, a Chōshū official. Later that year, he took part in the burning of the British legation in

Edo. Subsequently, along with

Yamao Yōzō, he assassinated the Japanese classics scholar Hanawa Jirō Tadatomi, acting on a false report. Takii notes that Itō is the only Japanese prime minister known to have killed a person outside of a battlefield (except for

Kuroda Kiyotaka, who was rumored to have killed his wife).

Despite his early immersion in Shōin's ideology, Itō later distanced himself from its radicalism, viewing the anti-Western sentiment of the era as "entirely emotional" and lacking "thoughtful political calculations". He came to admire figures like Nagai Uta for their pragmatic "political strategy", signaling his own developing preference for statesmanship grounded in realism.

Study in Britain and return

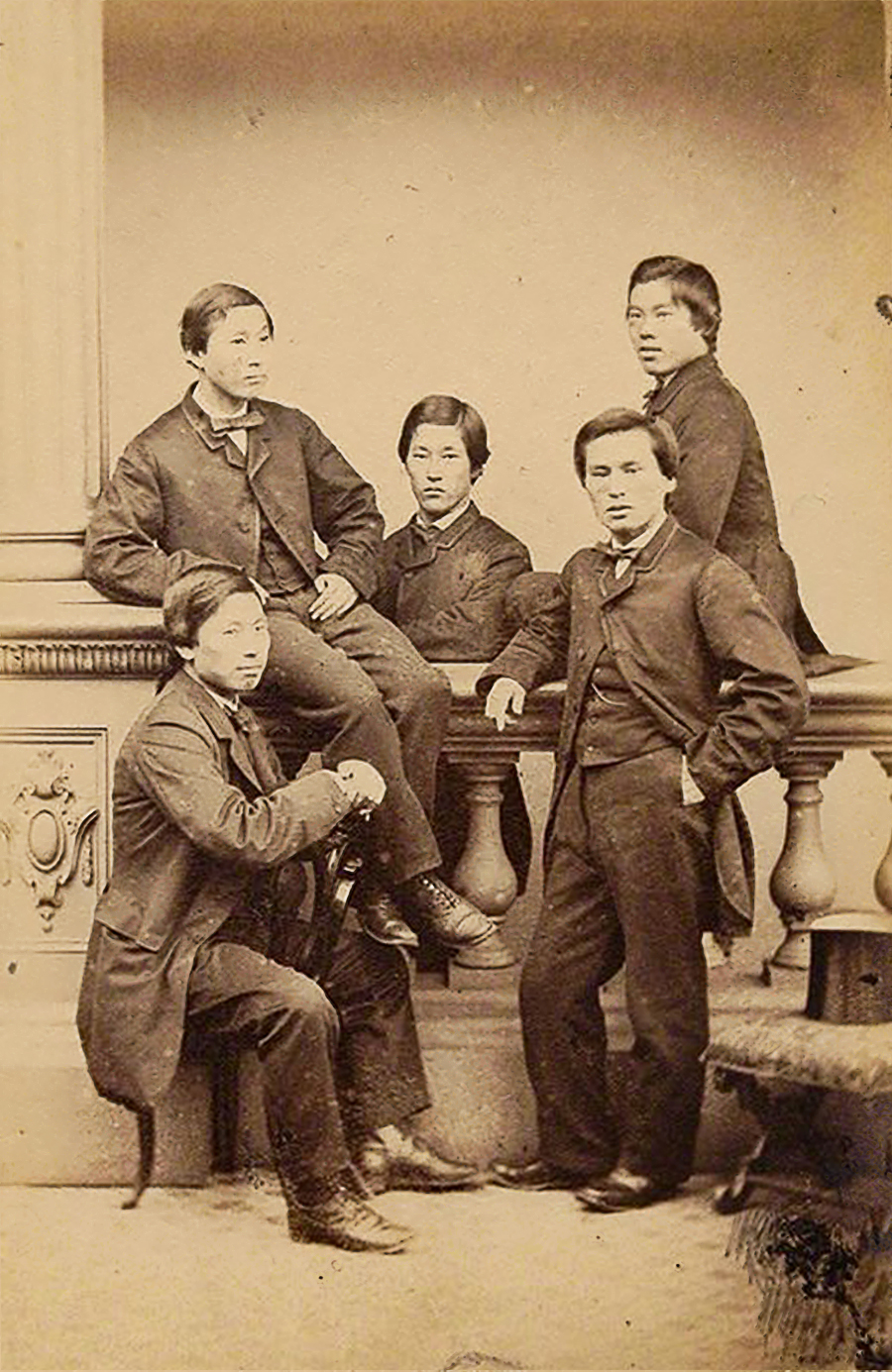

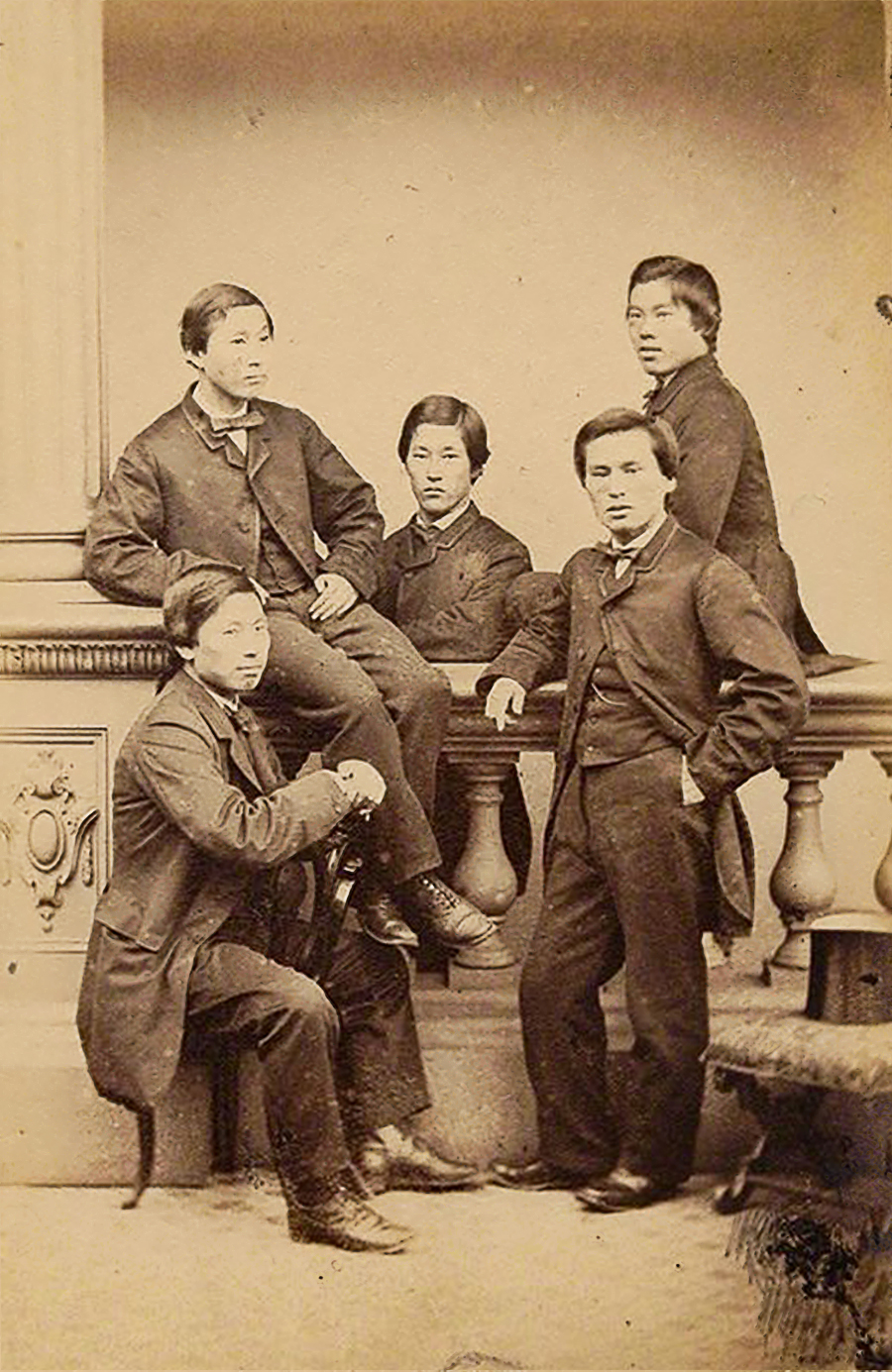

Driven by a strong desire for Western knowledge, Itō was selected as one of the

Chōshū Five to secretly travel to Britain in 1863 for study, an act that violated the

Tokugawa shogunate

The Tokugawa shogunate, also known as the was the military government of Japan during the Edo period from 1603 to 1868.

The Tokugawa shogunate was established by Tokugawa Ieyasu after victory at the Battle of Sekigahara, ending the civil wars ...

's ban on overseas travel. The Chōshū Domain's leadership, including Sufu Masanosuke, saw this as crucial for acquiring "human tools" and understanding Western civilization to prepare Japan for future international engagement. Itō and

Inoue Kaoru departed Japan on 27 June 1863, arriving in London on 4 November. The five students commenced their studies at

University College London

University College London (Trade name, branded as UCL) is a Public university, public research university in London, England. It is a Member institutions of the University of London, member institution of the Federal university, federal Uni ...

, lodging with Professor Alexander Williamson and immersing themselves in English language and Western customs.

Itō's initial period of study in Britain was cut short. After about six months, he and Inoue Kaoru decided to return to Japan upon learning from ''

The Times

''The Times'' is a British Newspaper#Daily, daily Newspaper#National, national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its modern name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its si ...

'' about the

Bombardment of Shimonoseki by Western powers and the conflict between the

Satsuma Domain

The , briefly known as the , was a Han system, domain (''han'') of the Tokugawa shogunate of Japan during the Edo period from 1600 to 1871.

The Satsuma Domain was based at Kagoshima Castle in Satsuma Province, the core of the modern city of ...

and a British naval squadron. Their aim was to persuade the Chōshū leaders of the impracticality of expelling foreigners.

This first overseas experience, though brief, proved to be a pivotal moment in Itō's life. He returned to Japan in July 1864, during a period of national crisis. His firsthand knowledge of the West and his newly acquired English skills made him an invaluable asset. Following Chōshū's defeat by the allied Western naval forces at Shimonoseki, Itō played a crucial role as a negotiator in the peace talks. This experience launched his career as a skilled negotiator, a talent Yoshida Shōin had earlier recognized. His time in Britain broadened his perspective beyond narrow domainal loyalties and the anti-foreign movement, fostering an independent spirit and a commitment to "extensive learning" (the meaning of "Hirobumi"). Itō developed a functional command of English, later delivering speeches in the language during the Iwakura Mission and maintaining a habit of reading English publications. He frequently gave interviews to Western media without an interpreter and conducted correspondence in English throughout his career.

Early Meiji statesman

Rise in the Meiji government

After the

Meiji Restoration

The , referred to at the time as the , and also known as the Meiji Renovation, Revolution, Regeneration, Reform, or Renewal, was a political event that restored Imperial House of Japan, imperial rule to Japan in 1868 under Emperor Meiji. Althoug ...

in 1868, Itō's understanding of Western affairs became a significant asset, propelling his career in the new imperial government. In February 1868, he was assigned to a role in foreign affairs. Later that year, he was appointed the first governor of

Hyōgo Prefecture

is a Prefectures of Japan, prefecture of Japan located in the Kansai region of Honshu. Hyōgo Prefecture has a population of 5,469,762 () and a geographic area of . Hyōgo Prefecture borders Kyoto Prefecture to the east, Osaka Prefecture to th ...

, which included the recently opened port of

Kobe

Kobe ( ; , ), officially , is the capital city of Hyōgo Prefecture, Japan. With a population of around 1.5 million, Kobe is Japan's List of Japanese cities by population, seventh-largest city and the third-largest port city after Port of Toky ...

. This position placed him at the forefront of Japan's diplomatic and international trade activities.

In February 1869, Itō submitted a significant policy paper, "Principles for National Policy" (''Kokuze kōmoku''), also known as the "Hyōgo Proposal". This comprehensive six-point plan advocated for:

# The establishment of a monarchy.

# The centralization of political and military power under imperial rule, which included supporting the

return of feudal domains to the emperor (''hanseki hōkan'').

# Active engagement and interaction with foreign countries.

# The elimination of

traditional class distinctions and the granting of greater freedom to the populace.

# The promotion of scientific learning and knowledge acquisition from around the world.

# International cooperation and the definitive end of anti-foreignism (''jōi'').

The proposal strongly emphasized the necessity "to let people throughout Japan learn the science behind the scientific achievements of the world, thereby spreading knowledge of the natural sciences". This highlighted Itō's early and enduring focus on education as a cornerstone of national development, reflecting his role as what Takii Kazuhiro terms a "statesman of knowledge". He urged the government to cultivate a "civilized and enlightened" populace and proposed the establishment of universities in Tokyo and

Kyoto

Kyoto ( or ; Japanese language, Japanese: , ''Kyōto'' ), officially , is the capital city of Kyoto Prefecture in the Kansai region of Japan's largest and most populous island of Honshu. , the city had a population of 1.46 million, making it t ...

.

Itō was profoundly influenced by the example of the United States, viewing its founding as a model for creating a unified nation-state where national prosperity was driven by the "united hearts and minds of the people". He advocated for transcending narrow domainal loyalties to forge a cohesive Japanese national identity.

Financial and monetary reforms

In 1870, while serving as deputy vice-minister of finance, Itō traveled to the United States to study its financial and monetary institutions. This investigative tour, which lasted from December 1870 to June 1871, directly influenced the establishment of Japan's New Currency Regulation (''Shinka Jōrei'') in 1871. This landmark legislation placed Japan on the

gold standard

A gold standard is a backed currency, monetary system in which the standard economics, economic unit of account is based on a fixed quantity of gold. The gold standard was the basis for the international monetary system from the 1870s to the ...

, aligning its monetary system with those of Western nations. Itō was a fervent champion of this reform, dispatching a memorandum from the U.S. that argued for its adoption based on the successful experience of "civilized Western countries". While the move to the gold standard was considered radical by some contemporaries, Takii notes that the reform also incorporated elements of continuity with Japan's pre-existing monetary framework.

Itō also played a pivotal role in the development of a modern banking system in Japan. He advocated for the creation of a bank of issue, and in December 1872, the National Bank Regulation (''Kokuritsu Ginkō Jōrei'') was promulgated, drawing inspiration from America's

National Bank Act

The National Banking Acts of 1863 and 1864 were two United States federal banking acts that established a system of national banks chartered at the federal level, and created the United States National Banking System. They encouraged developmen ...

. His proposal envisioned a system where national banks would be authorized to issue banknotes backed by government bonds. This was part of a strategy to gradually replace inconvertible paper currency with banknotes convertible into specie. This methodical, step-by-step approach to monetary reform was an early manifestation of the gradualism that would become a hallmark of Itō's broader reform philosophy.

Iwakura Mission and shift to gradualism

From late 1871 to 1873, Itō served as one of four deputy ambassadors in the

Iwakura Mission

The Iwakura Mission or Iwakura Embassy (, ''Iwakura Shisetsudan'') was a Japanese diplomatic voyage to Europe and the United States conducted between 1871 and 1873 by leading statesmen and scholars of the Meiji period. It was not the only such m ...

, a comprehensive eighteen-month diplomatic and investigative tour of the United States and Europe. The primary objectives of the mission were to initiate preliminary negotiations for the revision of the

unequal treaties imposed on Japan by Western powers and to observe and study various aspects of Western civilization, including political systems, industry, and education. Itō had been a key proponent of such an undertaking, having earlier suggested sending government officials abroad to study treaty revision and related international practices.

During the mission's initial leg in the United States, Itō's English proficiency and confident demeanor were notable, although his assertive style occasionally caused friction with some colleagues, such as

Sasaki Takayuki. In January 1872, at a welcoming event in

San Francisco

San Francisco, officially the City and County of San Francisco, is a commercial, Financial District, San Francisco, financial, and Culture of San Francisco, cultural center of Northern California. With a population of 827,526 residents as of ...

, he delivered a widely reported and spirited address, subsequently known as the "rising sun speech" (''hinomaru enzetsu''). In this speech, he proudly described Japan's rapid advancements in adopting Western institutions and proclaimed the nation's strong aspiration to achieve a high level of civilization and take its place among the advanced nations of the world.

A significant diplomatic misstep occurred in

Washington D.C. when Itō and fellow deputy ambassador

Ōkubo Toshimichi advocated for immediate treaty renegotiation with the United States, deviating from the mission's original plan to engage with Western powers collectively at a later stage. They even returned to Japan briefly to secure the necessary full

Letters of Credence for this purpose. However, upon their return to Washington, they discovered that the other mission members, having become aware of the complexities and potential disadvantages of unilateral

most-favored-nation clauses, had decided to adhere to the original strategy. This "Letters of Credence Incident" resulted in considerable embarrassment for Itō and significantly strained his relationship with

Kido Takayoshi

, formerly known as , was a Japanese statesman, samurai and ''Shishi (Japan), shishi'' who is considered one of the Three Great Nobles of the Restoration, three great nobles who led the Meiji Restoration.

Early life

Born Wada Kogorō on Augu ...

, another influential member of the mission.

Despite this setback, the Iwakura Mission proved to be a profoundly transformative experience for Itō, significantly shaping his political philosophy. His direct observations of political conditions in Europe, including periods of instability in France and the intricacies of

Otto von Bismarck

Otto, Prince of Bismarck, Count of Bismarck-Schönhausen, Duke of Lauenburg (; born ''Otto Eduard Leopold von Bismarck''; 1 April 1815 – 30 July 1898) was a German statesman and diplomat who oversaw the unification of Germany and served as ...

's

Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

, coupled with his intensive study of Western governmental and legal institutions, particularly in

Prussia

Prussia (; ; Old Prussian: ''Prūsija'') was a Germans, German state centred on the North European Plain that originated from the 1525 secularization of the Prussia (region), Prussian part of the State of the Teutonic Order. For centuries, ...

, led him to a deeper appreciation for the importance of well-established institutions and a more measured, gradual approach to national reform. He was particularly impressed by Kido Takayoshi's systematic and methodical study of various government systems encountered during the tour. This experience solidified Itō's transition from a proponent of more radical reforms to an advocate for gradual, systematic institution-building. He returned to Japan in September 1873, more convinced than ever of Japan's potential for successful modernization, but now firmly believing that gradualism, adapted to Japan's specific conditions, was the most effective path forward.

Father of the Meiji Constitution

Building the foundations (1873–1881)

Upon his return to Japan from the Iwakura Mission in September 1873, Itō was immediately thrust into the intense political debate surrounding the ''

Seikanron'' (debate over conquering

Korea

Korea is a peninsular region in East Asia consisting of the Korean Peninsula, Jeju Island, and smaller islands. Since the end of World War II in 1945, it has been politically Division of Korea, divided at or near the 38th parallel north, 3 ...

). He aligned himself with senior leaders like Iwakura Tomomi, Kido Takayoshi, and Ōkubo Toshimichi, who opposed a military expedition to Korea, advocating instead for a focus on domestic development and gradual reform. Following the "Political Crisis of 1873" (''Meiji rokunen seihen''), which saw the resignation of key proponents of the expedition, including

Saigō Takamori

Saigō Takamori (; 23 January 1828 – 24 September 1877) was a Japanese samurai and politician who was one of the most influential figures in Japanese history. He played a key role in the Meiji Restoration, which overthrew the Tokugawa shogunate ...

, Itō was appointed as a councilor (''

sangi'') and concurrently as

minister of public works, solidifying his position as a key figure in the government.

In November 1873, Itō, along with

Terashima Munenori, was tasked with "investigating constitutional government" (''seitai torishirabe''), marking the formal beginning of Japan's journey towards a written constitution. He was significantly influenced by the ideas of Kido and Ōkubo, both of whom submitted memorials to the throne advocating for the eventual establishment of a constitutional system that would include popular participation, to be achieved through a gradual process. Itō began to formulate concrete plans, proposing the convention of prefectural governors to form a lower assembly and the expansion of an existing imperial advisory body, the ''Jakō-no-ma'', into an upper assembly. These initiatives culminated in the

Osaka Conference of 1875, a meeting of key Meiji leaders that resulted in an imperial edict promising the gradual establishment of constitutional government. This edict led to the creation of the Assembly of Prefectural Governors and the

Genrōin

The was a Government of Meiji Japan#Establishment of a national assembly, national assembly in early Meiji period, Meiji Japan, established after the Osaka Conference of 1875. It is also referred to as the Senate of Japan, being the word used ...

(Chamber of Elders), institutions Itō saw as precursors to a future parliament.

In an 1880 opinion paper on the future constitution, submitted to

Emperor Meiji

, posthumously honored as , was the 122nd emperor of Japan according to the List of emperors of Japan, traditional order of succession, reigning from 1867 until his death in 1912. His reign is associated with the Meiji Restoration of 1868, which ...

, Itō reiterated his cautious approach. He advised against hastily establishing a full-fledged parliament, proposing instead a further strengthening of the Genrōin and the introduction of a system of public auditors, selected from the general populace, to oversee fiscal matters and promote transparency. This proposal underscored his commitment to gradualism and his belief that the emperor should publicly demonstrate this principle of measured reform.

Political Crisis of 1881 and European tour

The political landscape underwent a significant upheaval with the "Political Crisis of 1881". Councilor

Ōkuma Shigenobu controversially submitted a proposal directly to the throne (or via an intermediary, aiming for direct imperial attention) advocating for the immediate adoption of a British-style parliamentary cabinet system and the rapid establishment of a national assembly, with elections to be held as early as the following year. This move, perceived as a challenge to the established oligarchic leadership and their gradualist approach, combined with public outcry over the "Hokkaido Colonization Office Scandal" (in which government assets were to be sold cheaply to private interests connected to some officials), led to Ōkuma's dismissal from government. A crucial outcome of this crisis was an imperial edict promising the establishment of a

National Diet

, transcription_name = ''Kokkai''

, legislature = 215th Session of the National Diet

, coa_pic = Flag of Japan.svg

, house_type = Bicameral

, houses =

, foundation=29 November 1890(), leader1_type ...

(parliament) by the year 1890. It was also decided that the forthcoming constitution would be primarily modeled on that of Prussia (Germany), rather than the British system favored by Ōkuma.

In March 1882, Itō embarked on an extensive year-and-a-half-long study tour of Europe, with the primary mission of researching various European constitutions and systems of government in preparation for drafting Japan's own. His objective, as Takii Kazuhiro notes, was not merely to study constitutional texts but to understand "how to give living substance to that framework" – to learn how to effectively operate a constitutional state. In

Berlin

Berlin ( ; ) is the Capital of Germany, capital and largest city of Germany, by both area and List of cities in Germany by population, population. With 3.7 million inhabitants, it has the List of cities in the European Union by population withi ...

, he attended lectures by the legal scholar Professor

Rudolf von Gneist, but found Gneist's emphasis on historical jurisprudence and his skepticism about transplanting constitutional models less directly applicable to Japan's immediate needs. Itō encountered strong anti-parliamentarian sentiments in Germany, with both Gneist and even Kaiser

Wilhelm I

Wilhelm I (Wilhelm Friedrich Ludwig; 22 March 1797 – 9 March 1888) was King of Prussia from 1861 and German Emperor from 1871 until his death in 1888. A member of the House of Hohenzollern, he was the first head of state of a united Germany. ...

expressing reservations about the establishment of a powerful parliament, particularly in a nation without a long tradition of such institutions.

A more formative part of his European tour was his time in

Vienna

Vienna ( ; ; ) is the capital city, capital, List of largest cities in Austria, most populous city, and one of Federal states of Austria, nine federal states of Austria. It is Austria's primate city, with just over two million inhabitants. ...

, beginning in August 1882, where he studied with the political economist Professor

Lorenz von Stein. Stein's ''Staatswissenschaft'' (science of the state) had a profound impact on Itō. Stein's theories emphasized the critical role of effective state administration (''Verwaltung'') as a necessary complement to constitutional government (''Verfassung''), arguing for a system that could reconcile parliamentary mechanisms with the broader public interest and efficient governance of the state. This approach resonated deeply with Itō's pragmatic desire for practical guidelines for establishing and managing a constitutional state. Stein's ideas provided Itō with a sophisticated conceptual framework that moved beyond the abstract natural law theories then popular among some popular rights advocates in Japan, offering instead a model of a state grounded in administrative capacity and historical context. Furthermore, Stein stressed the importance of a robust system of education to support a constitutional state and cultivate an informed citizenry, reinforcing Itō's own belief in the concept of a "knowledge-based state". Itō returned to Japan in August 1883, equipped with new insights and renewed confidence for the task of constitution-making.

Drafting and promulgation, first premiership (1885–1888)

Upon his return from Europe, Itō assumed leadership of the newly established Bureau for Investigation of Constitutional Systems (''Seido Torishirabe Kyoku'') within the

Imperial Household Ministry in 1884. This body was specifically created to draft the constitution. He worked closely with a team of legal scholars and officials, including

Inoue Kowashi (often considered the principal drafter of the text),

Itō Miyoji, and

Kaneko Kentarō. While Inoue Kowashi was a strong proponent of the German model, Itō's extensive research across Europe, including his period of study in London, contributed to a broader and more nuanced understanding of constitutional principles. According to Takii Kazuhiro, Itō's overarching goal was to design a state structure that could effectively channel the energy and capabilities of an educated populace, integrating them into the machinery of government.

Several key institutional reforms led by Itō paved the way for the new constitutional order:

* Establishment of the

Cabinet System (1885): Itō spearheaded the creation of Japan's modern cabinet system, becoming the nation's first

Prime Minister

A prime minister or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. A prime minister is not the head of state, but r ...

. This reform replaced the traditional

Daijōkan (Grand Council of State) system. In principle, it opened cabinet positions to individuals beyond the traditional aristocracy, based on merit and ability.

* Founding of the

Imperial University (1886): He established the Imperial University (later the University of Tokyo) with the specific aim of educating and training a competent bureaucratic elite to administer the modern state. Within the university, the ''Kokka Gakkai'' (Society for Staatswissenschaft) was founded, with Itō's support, to serve as a policy research institution and think-tank.

* Creation of the

Privy Council (1888): After resigning as Prime Minister in April 1888, Itō became the first president of the

Privy Council. This body was initially formed to deliberate on the draft constitution and the

Imperial Household Law. Itō envisioned it as a high-level advisory body to the emperor on important political matters, serving to institutionalize the emperor's constitutional role while keeping the monarch separate from direct involvement in day-to-day political affairs and partisan disputes.

The

Meiji Constitution

The Constitution of the Empire of Japan ( Kyūjitai: ; Shinjitai: , ), known informally as the Meiji Constitution (, ''Meiji Kenpō''), was the constitution of the Empire of Japan which was proclaimed on February 11, 1889, and remained in ...

was officially promulgated on 11 February 1889. In speeches delivered shortly after the promulgation, Itō emphasized that the constitution was granted by the Emperor, a framework rooted in Japan's unique national polity (''

kokutai'') where sovereignty ultimately resided in the monarch. At the same time, he consistently stressed that the constitution also guaranteed popular participation in government through the Diet and acknowledged the inevitable emergence and role of political parties in a constitutional system. He conceived of a system where the emperor exercised sovereignty in accordance with the provisions of the constitution, with various administrative agencies acting on his behalf and responsible to the state. His underlying vision was for a "people-centered government", where an educated and politically aware populace would contribute to the nation's strength and development. For Itō, the promulgation of the constitution was not an endpoint but rather the foundational framework for the ongoing, gradual evolution of popular and responsible government in Japan.

Continued political career

Worldview and approach to governance

A core element of Itō's worldview was the belief in constant change and evolution in political systems. He recognized that as Japan modernized and its people became more educated and politically aware, the nature of its governance would also need to adapt. While he initially championed a "transcendental" cabinet that stood above partisan politics, his experiences, particularly after the promulgation of the Meiji Constitution, led him to acknowledge the inevitable rise and importance of political parties. In a letter to

Inoue Kaoru in August 1889, he criticized the

Kuroda Kiyotaka cabinet for its inflexibility and failure to prepare the populace for constitutional government, likening the process of nurturing a civilized nation to cultivating a seed into a healthy plant over many years. This reflects his consistent emphasis on gradualism and the cultivation of an informed citizenry capable of participating in constitutional government.

Itō's approach to governance was pragmatic. He believed that effective leadership required guiding the flow of political change rather than rigidly resisting it, steering the nation towards stable constitutional government. This involved not only establishing institutions but also fostering a "spirit of tolerance", a belief in freedom of speech, and orderly parliamentary proceedings.

Second and third premierships (1892–1896, 1898)

Itō remained a powerful figure even out of the Prime Minister's office, primarily through his leadership of the Privy Council. The first session of the

Imperial Diet was held in November 1890. In August 1892, Itō formed his second cabinet, serving as Prime Minister until August 1896. This period was marked by the outbreak of the

First Sino-Japanese War

The First Sino-Japanese War (25 July 189417 April 1895), or the First China–Japan War, was a conflict between the Qing dynasty of China and the Empire of Japan primarily over influence in Joseon, Korea. In Chinese it is commonly known as th ...

(1894–1895). Following Japan's victory, Itō was involved in the negotiations for the

Treaty of Shimonoseki in 1895.

Itō formed his third cabinet in January 1898. During this brief premiership, he expressed his intention to found a political party. However, facing difficulties in managing the government and opposition from figures like

Yamagata Aritomo

Prince was a Japanese politician and general who served as prime minister of Japan from 1889 to 1891, and from 1898 to 1900. He was also a leading member of the '' genrō'', a group of senior courtiers and statesmen who dominated the politics ...

to his party plans, Itō dissolved the

House of Representatives

House of Representatives is the name of legislative bodies in many countries and sub-national entities. In many countries, the House of Representatives is the lower house of a bicameral legislature, with the corresponding upper house often ...

in June 1898. Later that month, with the merger of the opposition Liberal and Progressive parties into the

Kenseitō

The was a political party in the Meiji period Empire of Japan.

History

The ''Kenseitō'' was founded in June 1898, as a merger of the Shimpotō headed by Ōkuma Shigenobu and the Liberal Party (Jiyūtō) led by Itagaki Taisuke, with Ōkuma a ...

, Itō resigned as Prime Minister, recommending that

Ōkuma Shigenobu and

Itagaki Taisuke

Kazoku, Count Itagaki Taisuke (板垣 退助, 21 May 1837 – 16 July 1919) was a Japanese samurai, politician, and leader of the Freedom and People's Rights Movement (自由民権運動, ''Jiyū Minken Undō''), which evolved into Japan's firs ...

form Japan's first party cabinet. This was a significant moment, signaling a shift in Itō's approach towards acknowledging the practical necessity of party-based support for governance.

Relations with China

Itō Hirobumi's engagement with China was a significant, though complex, aspect of his later career, influencing his views on regional stability, economic development, and Japan's role in East Asia. His two-month visit to Korea and China in August–November 1898, undertaken shortly after the dissolution of his third cabinet, proved particularly formative.

During this trip, Itō was warmly received by Chinese reformers, including

Kang Youwei, who saw Meiji Japan as a model for China's own modernization. He arrived in Beijing at the height of the

Hundred Days' Reform movement, led by the

Guangxu Emperor

The Guangxu Emperor (14 August 1871 – 14 November 1908), also known by his temple name Emperor Dezong of Qing, personal name Zaitian, was the tenth Emperor of China, emperor of the Qing dynasty, and the ninth Qing emperor to rule over China ...

. However, Itō found himself on the fringes of the 1898 coup engineered by

Empress Dowager Cixi

Empress Dowager Cixi ( ; 29 November 1835 – 15 November 1908) was a Manchu noblewoman of the Yehe Nara clan who effectively but periodically controlled the Chinese government in the late Qing dynasty as empress dowager and regent for almost 50 ...

, which abruptly ended the reforms and led to the persecution of its leaders. While Itō was critical of the reformers' precipitous approach and maintained a cautious distance from their movement, he was deeply concerned by the ensuing political instability and the purge of reformist intellectuals. He intervened to help some reformers, like

Liang Qichao

Liang Qichao (Chinese: 梁啓超; Wade–Giles: ''Liang2 Chʻi3-chʻao1''; Yale romanization of Cantonese, Yale: ''Lèuhng Kái-chīu''; ) (February 23, 1873 – January 19, 1929) was a Chinese politician, social and political activist, jour ...

, escape to Japan and advocated for the protection of others.

Itō's encounters with prominent Chinese officials like

Zhang Zhidong

Zhang Zhidong ( zh, t=張之洞) (2 September 18374 October 1909) was a Chinese politician who lived during the late Qing dynasty. Along with Zeng Guofan, Li Hongzhang and Zuo Zongtang, Zhang Zhidong was one of the four most famous offici ...

,

viceroy of Huguang, were particularly significant. Despite the political turmoil, Itō and Zhang found common ground in their advocacy for gradual reform and their appreciation for Western science and technology, albeit within a framework that respected national context. Itō was particularly interested in Zhang's efforts to develop industry in the

Hubei

Hubei is a province of China, province in Central China. It has the List of Chinese provincial-level divisions by GDP, seventh-largest economy among Chinese provinces, the second-largest within Central China, and the third-largest among inland ...

region, including the

Hanyang Steel Mill. Their meeting facilitated an agreement for Japan's

Yahata Steel Works to obtain

iron ore

Iron ores are rocks and minerals from which metallic iron can be economically extracted. The ores are usually rich in iron oxides and vary in color from dark grey, bright yellow, or deep purple to rusty red. The iron is usually found in the f ...

from China's

Daye mine, a development that marked the beginning of significant Japan-China economic cooperation in this sector, though it later became a point of contention in imperialistic narratives.

While pessimistic about China's immediate political future due to its internal divisions and the perceived rigidity of its institutions, Itō was highly optimistic about its economic potential. He believed that Japan, as a more advanced nation in the region, had a role to play in fostering economic ties and promoting "civilization" – by which he meant modern science, industry, and rational governance – in China. His vision for Japan involved steering clear of direct political interference in China while actively engaging with its economy, seeing mutual benefit in regional development. He consistently argued against territorial expansion for its own sake, emphasizing that economic prosperity and the exchange of knowledge were more important. However, he also spoke of Japan's "moral obligation" as a "pioneer of modernization" to guide China and Korea, a stance that, while framed in terms of shared progress, carried paternalistic undertones. His experiences in China in 1898 reinforced his belief in a gradual, education-focused approach to modernization and informed his strategy for Japan's engagement with the continent, emphasizing economic cooperation and the cultivation of a "nation of commerce".

Stumping for the Constitution

Following the promulgation of the Meiji Constitution in 1889, Itō embarked on extensive speaking tours across Japan in 1899, the tenth anniversary of the event. His primary aim was to "enlighten the people of his country and help equip them to become members of a constitutional state". These tours were not primarily for partisan political gain but to propagate the ideals of constitutionalism and popular government. He used a sophisticated media strategy, ensuring that reporters from newspapers like the ''

Tōkyō Nichinichi Shinbun'' accompanied him, and his speeches were widely disseminated and even compiled into a book.

In these speeches, Itō emphasized that the constitution guaranteed the people's right to participate in government and that a "civilized government" was predicated on an educated and politically aware populace. He argued that as the people's knowledge and intellect grew, their involvement in supervising the government would become essential. He promoted "practical science" and apolitical education, which he believed would foster a competent citizenry capable of contributing to national prosperity and effective governance, rather than engaging in empty political rhetoric. This reflected his long-held belief, first articulated in his 1879 proposal "On Education" (''Kyōiku-gi''), that education should focus on practical skills and knowledge to counteract excessively passionate political debate.

Treaty revision and foreign relations

A major national goal during Itō's career was the revision of the

unequal treaties imposed on Japan by Western powers in the mid-19th century. The new treaties, which abolished

extraterritoriality

In international law, extraterritoriality or exterritoriality is the state of being exempted from the jurisdiction of local law, usually as the result of diplomatic negotiations.

Historically, this primarily applied to individuals, as jurisdict ...

and partially restored tariff autonomy, came into effect in July–August 1899. Itō saw this as a momentous occasion, marking Japan's full entry into the international community and the "mixed residence" (''naichi zakkyo'') of Japanese and foreigners. He countered fears of economic invasion by arguing that opening the country would facilitate Japan's economic growth through competition and the absorption of Western knowledge and experience. His primary concern was that Japan should face the world "with the magnanimity of a great nation" and maintain its "civilized" status.

His views on patriotism (''aikokushin'') were pragmatic, emphasizing economic development and national wealth creation over ideological fervor or

jingoism. "Without wealth the culture of the people cannot advance", he stated, advocating for patriotism that served practical ends.

Founding of the Rikken Seiyūkai

Despite his earlier advocacy for a "transcendental" cabinet, Itō's thinking on the role of political parties evolved. He became increasingly dissatisfied with the existing state of party politics in Japan, which he viewed as fractious and often detrimental to national harmony and effective governance. His decision to form a new political party stemmed from a desire to reform party politics from within and to create an organization that could support his vision of constitutional government.

In September 1900, Itō founded the

Rikken Seiyūkai

The was one of the main political party, political parties in the pre-war Empire of Japan. It was also known simply as the ''Seiyūkai''.

Founded on September 15, 1900, by Itō Hirobumi,David S. Spencer, "Some Thoughts on the Political Devel ...

(Friends of Constitutional Government), becoming its first president. This marked the birth of Japan's first political party capable of taking the reins of government, and it became a dominant force in Japanese politics for decades, eventually evolving into the modern

Liberal Democratic Party.

Motivations and ideals

Itō envisioned the Seiyūkai not merely as a vehicle for gaining political power but as a new kind of political organization – a "society" (''kai'') rather than a traditional "party" (''tō''), a term he felt carried connotations of self-serving factions (''hōtō''). He aimed to create an organization that could transcend narrow partisan interests and act for the public benefit. According to Takii Kazuhiro's re-evaluation, the Seiyūkai was part of Itō's broader plan to revamp Japan's administrative system and bureaucracy to meet the demands of a new industrial era and to more fully realize the potential of constitutional government by expanding popular participation. He saw the party as a means to channel the rising political awareness of local leaders, businessmen, and industrialists into constructive engagement with the state.

The Seiyūkai was intended to function as a "think-tank", a repository of knowledge and expertise drawn from various segments of society, capable of formulating sound policies for national development. Itō believed that a responsible party should supply competent personnel to the cabinet and contribute to harmonious governance, rather than simply seeking to control the executive branch.

Formation, fourth premiership (1900–1901)

The formation of the Seiyūkai was not without difficulties. Itō's attempts to rally support from the business and financial communities met with limited success. Prominent figures like

Shibusawa Eiichi, while sympathetic to Itō's policies, were hesitant to directly join the party, partly due to a traditional disdain among entrepreneurs for direct political involvement and partly due to interference from established political and business interests, such as those connected to

Iwasaki Yanosuke, who was aligned with Ōkuma's Progressive Party. Ultimately, the Seiyūkai was formed largely on the existing organizational base of the Kenseitō (the former Liberal Party faction), led by figures like

Hoshi Tōru.

Itō's draft rules for the Seiyūkai emphasized several key principles:

# The Emperor's prerogative in appointing cabinet ministers, with the party not opposing appointments from outside its ranks.

# The cabinet's role as an advisory body to the Emperor and a body of responsible government, free from direct party interference.

# A focus on administrative reform through the selection of competent individuals for government posts, regardless of party affiliation.

# A commitment to acting for the public benefit and avoiding undue involvement in local interests.

# Strong leadership by the party president in public pronouncements and parliamentary activities.

These rules reflected Itō's ideal of a party that maintained a distinction between itself and the cabinet, promoted national unity, and was led with clear authority and discipline. He advocated for a "salon-like" or club-style organization for the party's local branches to encourage broad participation and the free exchange of ideas, while simultaneously insisting on strong central leadership.

Soon after its founding, Itō formed his fourth cabinet in October 1900, with most ministerial posts filled by Seiyūkai members. However, this cabinet was short-lived, plagued by internal disunity and difficulties in managing party members' demands for posts. Itō resigned as Prime Minister in May 1901. He continued as president of the Seiyūkai but faced ongoing challenges in instilling his ideals of party discipline and national-level focus. Disappointment over issues like the government's handling of the

Anglo-Japanese Alliance (which he had initially opposed in favor of a Russo-Japanese entente) and internal party conflicts led to his resignation as Seiyūkai president in July 1903. He was succeeded as party leader by

Saionji Kinmochi

Kazoku, Prince was a Japanese politician who served as Prime Minister of Japan, prime minister of Japan from 1906 to 1908, and from 1911 to 1912. As the last surviving member of the ''genrō'', the group of senior statesmen who had directed pol ...

.

Constitutional Reforms of 1907

Even after stepping down from active party leadership, Itō continued to be deeply involved in shaping Japan's constitutional framework. From 1903, as reappointed president of the Imperial Household Research Committee (which he had first headed in 1899), he embarked on a major project of constitutional reforms, culminating in significant legislative changes in 1907. These reforms aimed to consolidate the national structure, clarify the emperor's role, and strengthen the cabinet's authority in governance.

The committee's primary task, under Itō's guidance and with the detailed work of legal scholar

Ariga Nagao, was to restructure the imperial household system and integrate it more fully as an organ of the state, rather than a separate entity. This involved revising the Imperial Household Law and establishing a unified system of national laws that clearly positioned the imperial household within the state's constitutional framework. The Kōshikirei Order (Order concerning Forms of Imperial Rescripts, Statutes, and Other State Documents) of 1907 was a key outcome, establishing procedures for issuing imperial edicts and revising fundamental laws, including the Meiji Constitution and the Imperial Household Law itself.

A crucial aspect of these reforms was the effort to bolster the power of the Prime Minister and the cabinet, particularly in relation to the military. The revised Cabinet Organization Order, implemented alongside the Kōshikirei Order, restored the requirement for the Prime Minister to countersign all laws and imperial ordinances, an attempt to curb the military's practice of ''iaku jōsō'' (direct appeal to the emperor on military matters, bypassing the cabinet). Itō envisioned a system of responsible government led by a strong cabinet, with the emperor acting as a constitutional monarch whose prerogatives were exercised in accordance with law and through designated state organs.

However, these efforts to subordinate the military to cabinet control met with strong resistance from army leaders, particularly

Yamagata Aritomo

Prince was a Japanese politician and general who served as prime minister of Japan from 1889 to 1891, and from 1898 to 1900. He was also a leading member of the '' genrō'', a group of senior courtiers and statesmen who dominated the politics ...

. The ensuing compromise resulted in the promulgation of Military Ordinance No. 1 ("On Military Ordinances") in September 1907, which, while intended by some in government (like Home Minister

Hara Takashi) to codify and thus limit ''iaku jōsō'', effectively institutionalized the military's right of direct appeal for "supreme command-related matters". This outcome, though a partial setback for Itō's goal of full cabinet supremacy, was seen by him as a step towards clarifying the military's constitutional position, with the ongoing intent to bring military administration under greater legal and cabinet oversight, particularly during his subsequent role in Korea. The 1907 reforms, therefore, represented a complex and somewhat ambiguous development in Meiji constitutionalism, aiming to create a more integrated and powerful state but also inadvertently solidifying a degree of military independence.

Resident-General of Korea

Itō Hirobumi's final major role was as the first

Resident-General of Korea, a position he assumed in March 1906 following the establishment of Japan's protectorate over Korea via the

Second Japan–Korea Treaty (Eulsa Treaty) in November 1905. This period of his career is among the most controversial, directly preceding Japan's full annexation of Korea in 1910.

Dual role and objectives

During his tenure as Resident-General, Itō simultaneously continued his work on constitutional reforms in Japan as president of the Imperial Household Research Committee. Takii Kazuhiro argues that these two roles were interconnected; Itō's administration in Korea was, in part, an attempt to implement and test his ideas on governance and constitutionalism, particularly regarding the control of the military, which he hoped could serve as a precedent for reforms in Japan.

Itō approached the governance of Korea with a philosophy of "civilization", aiming to modernize the country through gradual reforms in its political, economic, and social structures. He emphasized democracy (popular government), the

rule of law

The essence of the rule of law is that all people and institutions within a Body politic, political body are subject to the same laws. This concept is sometimes stated simply as "no one is above the law" or "all are equal before the law". Acco ...

, and gradualism as the guiding principles for Korea's development, much as he had for Japan. He believed that an educated populace was key to national advancement and initially expressed hope for Korea's potential for self-government.

Policies and challenges

A central part of Itō's agenda was educational reform. He advocated for the introduction of Western-style practical science and the establishment of a modern education system, aiming to move Korea away from its traditional

Confucian

Confucianism, also known as Ruism or Ru classicism, is a system of thought and behavior originating in ancient China, and is variously described as a tradition, philosophy, religion, theory of government, or way of life. Founded by Confucius ...

-centric learning, which he viewed as anachronistic and detrimental to progress. He sought to depoliticize the Korean imperial court and integrate it into a rationalized state structure, similar to his efforts with the Japanese imperial system.

However, Itō's policies faced immense challenges. His gradualist approach clashed with the growing

Korean nationalist movement, which fiercely resisted Japanese interference and sought immediate independence. His efforts to win over Korean intellectuals and Confucian scholars were largely unsuccessful, as his modernization agenda was perceived as an imposition by a foreign power. The

Hague Secret Emissary Affair in 1907, where

Emperor Gojong

Gojong (; 8 September 1852 – 21 January 1919), personal name Yi Myeongbok (), later Yi Hui (), also known as the Gwangmu Emperor (), was the penultimate List of monarchs of Korea, Korean monarch. He ruled Korea for 43 years, from 1864 to 19 ...

attempted to appeal to international powers against the protectorate, led to Gojong's forced abdication and the signing of the

Third Japan–Korea Treaty, which significantly expanded the Resident-General's powers and effectively brought Korean domestic administration under Japanese control.

Itō also worked to assert civilian control over the Japanese military garrison in Korea, a continuation of his efforts in Japan to subordinate the military to the cabinet. The ordinance establishing the Residency-General, which Itō himself drafted, granted him the authority to command the Japanese troops in Korea, a rare power for a civilian official. He used this authority to limit military expansion and check arbitrary actions by the army.

Shift towards annexation and resignation

Despite his initial emphasis on reform and gradual development, the persistent Korean resistance and the complex geopolitical situation led Itō to eventually acquiesce to the idea of annexing Korea. While he had previously counseled caution, viewing annexation as "extremely difficult and burdensome", by April 1909, he agreed to the proposal put forward by Foreign Minister

Komura Jutarō and Prime Minister

Katsura Tarō. This shift is attributed by Takii to Japan's decision to secure Korea in exchange for ceasing its pursuit of interests in

Manchuria

Manchuria is a historical region in northeast Asia encompassing the entirety of present-day northeast China and parts of the modern-day Russian Far East south of the Uda (Khabarovsk Krai), Uda River and the Tukuringra-Dzhagdy Ranges. The exact ...

, a compromise reached amidst international pressures, particularly concerning the

Gando territorial dispute with China. For Itō, preventing deeper military entanglement in Manchuria became a paramount concern.

Itō resigned as Resident-General in June 1909. Even as he agreed to annexation, his dictated memo outlined a post-annexation structure for Korea that included a two-house parliament with elected Korean representatives and a responsible cabinet composed of Koreans, supervised by a Japanese viceroy. This suggests that even in the context of annexation, Itō envisioned a degree of Korean autonomy and popular participation, though whether this was a realistic or achievable plan remains debatable.

Assassination

On 26 October 1909, Itō Hirobumi was assassinated at the

Harbin

Harbin, ; zh, , s=哈尔滨, t=哈爾濱, p=Hā'ěrbīn; IPA: . is the capital of Heilongjiang, China. It is the largest city of Heilongjiang, as well as being the city with the second-largest urban area, urban population (after Shenyang, Lia ...

railway station in Manchuria. He was there to meet with

Vladimir Kokovtsov

Count Vladimir Nikolayevich Kokovtsov (; – 29 January 1943) was a Russian politician who served as the fourth prime minister of Russia from 1911 to 1914, during the reign of Emperor Nicholas II.

Early life

He was born in Borovichi, Borov ...

, a Russian representative, to discuss regional issues, including Manchuria. As Itō stepped off the train, he was shot multiple times by

An Jung-geun, a Korean nationalist and independence activist. An viewed Itō as the prime architect of Japan's usurpation of Korean sovereignty and held him responsible for the loss of Korean independence. Itō's death sent shockwaves through Japan and the international community. His assassination removed a powerful, albeit controversial, voice from Japanese politics and is considered by some historians to have accelerated Japan's path towards the

full annexation of Korea, which occurred in August 1910.

Legacy

Itō Hirobumi remains a highly significant and complex figure in modern Japanese history. He is widely recognized as a principal architect of the Meiji state, the "father of the Meiji Constitution", and a driving force behind Japan's rapid modernization in the late 19th century. His achievements include the establishment of key institutions such as the cabinet system, the Imperial University, the Diet, and the Privy Council, all of which laid the groundwork for modern Japanese governance. His founding of the Rikken Seiyūkai was a pivotal step in the development of party politics in Japan.

However, his legacy is also deeply controversial, particularly due to his role as Resident-General of Korea and his part in the process that led to Korea's annexation. While some interpretations, such as that of Takii Kazuhiro, emphasize his commitment to gradualism, civilization-building, and constitutionalism, even in his approach to Korea, he is widely viewed in Korea as a symbol of Japanese imperialism.

Takii Kazuhiro's scholarship presents Itō not as an unprincipled opportunist, but as a "statesman of knowledge" (''chi no seijika'') who consistently pursued a vision of a strong, civilized, and constitutional Japanese state. This interpretation highlights Itō's lifelong emphasis on education, the acquisition of practical knowledge, and the gradual development of popular participation in government as essential components of nation-building. His efforts to integrate the imperial institution into a modern constitutional framework and to balance executive power with parliamentary mechanisms were central to his political project.

The complexities of his legacy are reflected in the contrasting ways he is remembered: in Japan, often as a great modernizer, and in Korea, as a key figure in its colonization. His assassination by An Jung-geun is a stark reminder of the deep enmities engendered by

Japan's imperial expansion. Reconciling these different facets of Itō Hirobumi's life and impact remains an ongoing task for historians.

Former residence of Itō in Hagi

The house where Itō lived from age 14 in Hagi after his father was adopted by Itō Naoemon still exists, and is preserved as a museum. It is a one-story house with a thatched roof and a gabled roof, with a total floor area of 29

''tsubo'' and is located 150 meters south of the

Shōkasonjuku Academy. The adjacent villa is a portion of a house built by Itō in 1907 in Oimura, Shimoebara-gun, Tokyo (currently

Shinagawa, Tokyo

is a Special wards of Tokyo, special ward in the Tokyo, Tokyo Metropolis in Japan. The Ward refers to itself as Shinagawa City in English. The Ward is home to ten embassies.

, the Ward had an estimated population of 380,293 and a population d ...

). It was a large Western-style mansion, of which three structures, a part of the entrance, a large hall, and a detached room, were transported Hagi. The large hall has a mirrored ceiling and its wooden paneling uses 1000-year old cedar trees from

Yoshino.

The buildings were collectively designated a

National Historic Site in 1932.

On 26 October 1932, the Japanese unveiled in Seoul the Hakubun-ji (

博文寺) Buddhist Temple dedicated to Prince Itō. Full official name "Prince Itō Memorial Temple (伊藤公爵祈念寺院)". Situated in then Susumu Tadashidan Park on the north slope of Namsan, which after liberation became Jangchungdan Park 장충단 공원. From October 1945, the main hall served as student home, ca. 1960 replaced by a guest house of the Park Chung-Hee administration, then reconstructed and again a student guest house. In 1979 it was incorporated into the grounds of the Shilla Hotel then opened. Several other parts of the temple are still at the site.

Personal life

Itō Hirobumi married Itō Umeko, who was the daughter of Kida Kyūbei of Jōnokoshi, Shimonoseki, in 1866. He had previously been married to Irie Sumiko from 1863, but they divorced in 1866. He had a son-in-law,

Suematsu Kenchō, and an adopted son,

Yūkichi (1870–1931).

Honours

Japanese

Peerages

*Count (7 July 1884)

*Marquess (5 August 1895)

*Prince (21 September 1907)

Decorations

* Grand Cordon of the

Order of the Rising Sun

The is a Japanese honors system, Japanese order, established in 1875 by Emperor Meiji. The Order was the first national decoration awarded by the Japanese government, created on 10 April 1875 by decree of the Council of State. The badge feat ...

(2 November 1877)

*

Grand Cordon of the

Order of the Rising Sun with Paulownia Flowers (11 February 1889)

* Grand Cordon of the

Order of the Chrysanthemum (5 August 1895)

* Collar of the Order of the Chrysanthemum (1 April 1906)

Court ranks

*Fifth rank, junior grade (1868)

*Fifth rank (1869)

*Fourth rank (1870)

*Senior fourth rank (18 February 1874)

*Third rank (27 December 1884)

*Second rank (19 October 1886)

*Senior second rank (20 December 1895)

*

Junior First Rank

The court ranks of Japan, also known in Japanese language, Japanese as ''ikai'' (位階), are indications of an individual's court rank in Japan based on the system of the Nation, state. ''Ikai'' as a system was the indication of the rank of burea ...

(26 October 1909; posthumous)

Foreign

* :

** Knight 1st Class of the

Order of the Crown (29 December 1884)

** Grand Cross of the

Order of the Red Eagle (22 December 1886); in Brilliants (December 1901)

** : Grand Cross of the

Order of the White Falcon (29 September 1882)

* :

** Knight of the

Order of the White Eagle (17 September 1883)

** Knight of the

Order of St. Alexander Nevsky (19 March 1896); in Brilliants (28 November 1901)

*

Sweden-Norway: Commander Grand Cross of the

Order of Vasa

The Royal Order of Vasa () is a Swedish order of chivalry founded on 29 May 1772 by Gustav III, King Gustav III. It is awarded to Swedish citizens for service to state and society especially in the fields of agriculture, mining and commerce.

His ...

(25 May 1885)

* : Knight 1st Class of the

Order of the Iron Crown (27 September 1885)

*

Siam: Grand Cross of the

Order of the Crown of Siam (24 January 1888)

* : Grand Cross of the

Order of Charles III

The Royal and Distinguished Spanish Order of Charles III, originally Royal and Much Distinguished Order of Charles III (, originally ; Abbreviation, Abbr.: OC3) is a knighthood and one of the three preeminent Order of merit, orders of merit bes ...

(26 October 1896)

* : Grand Cordon of the

Royal Order of Leopold (4 October 1897)

* : Grand Cross of the

Legion of Honour

The National Order of the Legion of Honour ( ), formerly the Imperial Order of the Legion of Honour (), is the highest and most prestigious French national order of merit, both military and Civil society, civil. Currently consisting of five cl ...

(29 April 1898)

* :

Order of the Double Dragon, Class I Grade III (5 December 1898)

* : Honorary Grand Cross of the

Order of the Bath

The Most Honourable Order of the Bath is a British order of chivalry founded by King George I of Great Britain, George I on 18 May 1725. Recipients of the Order are usually senior British Armed Forces, military officers or senior Civil Service ...

(civil division) (14 January 1902)

* : Knight of the

Supreme Order of the Most Holy Annunciation

The Supreme Order of the Most Holy Annunciation () is a Catholic order of chivalry, originating in County of Savoy, Savoy. It eventually was the pinnacle of the Orders, decorations, and medals of Italy#The Kingdom of Italy, honours system in the ...

(16 January 1902)

* : Grand Cordon of the

Order of the Golden Ruler (18 April 1904)

Popular culture

See also

*

Japanese students in Britain

References

Works cited

*

*

Nish, Ian (1998). ''The Iwakura Mission to America and Europe: A New Assessment''. Richmond, Surrey: Japan Library. . .

Further reading

* Edward, I. "Japan's Decision to Annex Taiwan: A Study of Itō-Mutsu Diplomacy, 1894–95". ''Journal of Asian Studies'' 37#1 (1977): 61–72.

* Hamada Kengi (1936). ''Prince Ito''. Tokyo: Sanseido Co.

* Johnston, John T.M. (1917). ''World Patriots''. New York: World Patriots Co.

* Kusunoki Sei'ichirō (1991). ''Nihon shi omoshiro suiri: Nazo no satsujin jiken wo oe''. Tokyo: Futami bunko.

* Ladd, George T. (1908)

''In Korea with Marquis Ito''* Nakamura Kaju (1910)

''Prince Ito: The Man and the Statesman: A Brief History of His Life''.New York: Japanese-American commercial weekly and Anraku Pub. Co.

* Palmer, Frederick (1901). "Marquis Ito: The Great Man of Japan". ''Scribner’s Magazine'' 30(5), 613–621.

External links

*

About Japan: A Teacher's ResourceIdeas about how to teach about Ito Hirobumi in a K–12 classroom

*

*

, -

, -

, -

, -

, -

, -

, -

, -

, -

, -

, -

, -

{{DEFAULTSORT:Itō, Hirobumi

1841 births

1909 deaths

19th-century prime ministers of Japan

20th-century prime ministers of Japan

Alumni of University College London

An Jung-geun

Assassinated prime ministers of Japan

Commanders Grand Cross of the Order of Vasa

Critics of religions

Deaths by firearm in China

Deified Japanese men

Ministers for foreign affairs of Japan

Grand Cross of the Legion of Honour

Honorary Knights Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath

Japanese atheists

Japanese diplomats

Japanese expatriates in the United Kingdom

Japanese imperialism and colonialism

Japanese people murdered abroad

Japanese people of the Russo-Japanese War

Japanese politicians assassinated in the 20th century

Japanese Residents-General of Korea

Kazoku

Keijō nippō people

Members of the House of Peers (Japan)

Members of the Iwakura Mission

Mōri retainers

Nobles of the Meiji Restoration

People from Chōshū Domain

People from Hikari, Yamaguchi

People murdered in China

People of the First Sino-Japanese War

Politicians assassinated in the 1900s

Politicians from Yamaguchi Prefecture

Recipients of the Order of the Rising Sun with Paulownia Flowers

Rikken Seiyūkai politicians

Rikken Seiyūkai prime ministers of Japan

Samurai

Driven by a strong desire for Western knowledge, Itō was selected as one of the Chōshū Five to secretly travel to Britain in 1863 for study, an act that violated the

Driven by a strong desire for Western knowledge, Itō was selected as one of the Chōshū Five to secretly travel to Britain in 1863 for study, an act that violated the  From late 1871 to 1873, Itō served as one of four deputy ambassadors in the

From late 1871 to 1873, Itō served as one of four deputy ambassadors in the  The political landscape underwent a significant upheaval with the "Political Crisis of 1881". Councilor Ōkuma Shigenobu controversially submitted a proposal directly to the throne (or via an intermediary, aiming for direct imperial attention) advocating for the immediate adoption of a British-style parliamentary cabinet system and the rapid establishment of a national assembly, with elections to be held as early as the following year. This move, perceived as a challenge to the established oligarchic leadership and their gradualist approach, combined with public outcry over the "Hokkaido Colonization Office Scandal" (in which government assets were to be sold cheaply to private interests connected to some officials), led to Ōkuma's dismissal from government. A crucial outcome of this crisis was an imperial edict promising the establishment of a