Italy–Yugoslavia Relations on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Italy–Yugoslavia relations (; sh-Latn-Cyrl, Odnosi Italije i Jugoslavije, Односи Италије и Југославије; ; ) are the cultural and political relations between Italy and

On 26 April 1915, the

On 26 April 1915, the

Before becoming the ''

Before becoming the ''

The

The

When the Fascist regime collapsed in 1943 and Italy capitulated, its eastern border territory was occupied by German forces, the authority of the

When the Fascist regime collapsed in 1943 and Italy capitulated, its eastern border territory was occupied by German forces, the authority of the  The end of the war on the Italian-Yugoslav border, after the Italian capitulation on 8 September 1943, was marked by the

The end of the war on the Italian-Yugoslav border, after the Italian capitulation on 8 September 1943, was marked by the

The

The

online

* Pavlović, Vojislav G. "Le conflit franco-italien dans les Balkans 1915–1935. Le rôle de la Yougoslavie." ''Balcanica'' 36 (2005): 163-20

online in French

* Zametica, Jovan. "Sir Austen Chamberlain and the Italo-Yugoslav crisis over Albania February-May 1927." ''Balcanica'' 36 (2005): 203-235

online

{{DEFAULTSORT:Italy-Yugoslavia Relations

Yugoslavia

, common_name = Yugoslavia

, life_span = 1918–19921941–1945: World War II in Yugoslavia#Axis invasion and dismemberment of Yugoslavia, Axis occupation

, p1 = Kingdom of SerbiaSerbia

, flag_p ...

in the 20th century, since the creation of Yugoslavia

Yugoslavia was a State (polity), state concept among the South Slavs, South Slavic intelligentsia and later popular masses from the 19th to early 20th centuries that culminated in its realization after the 1918 collapse of Austria-Hungary at th ...

in 1918 until its dissolution in 1992. Relations immediately after the end of World War I, and shortly before the rise of fascism in Italy, were severely affected and constantly tense due to the dispute over Dalmatia

Dalmatia (; ; ) is a historical region located in modern-day Croatia and Montenegro, on the eastern shore of the Adriatic Sea. Through time it formed part of several historical states, most notably the Roman Empire, the Kingdom of Croatia (925 ...

and the city-port of Fiume (Rijeka). Relations during the interwar years

In the history of the 20th century, the interwar period, also known as the interbellum (), lasted from 11 November 1918 to 1 September 1939 (20 years, 9 months, 21 days) – from the end of World War I (WWI) to the beginning of World War II ( ...

were hostile because of Italian demands for Yugoslav territory, contributing to decision by Italy

Italy, officially the Italian Republic, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe, Western Europe. It consists of Italian Peninsula, a peninsula that extends into the Mediterranean Sea, with the Alps on its northern land b ...

and Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

to invade Yugoslavia during World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

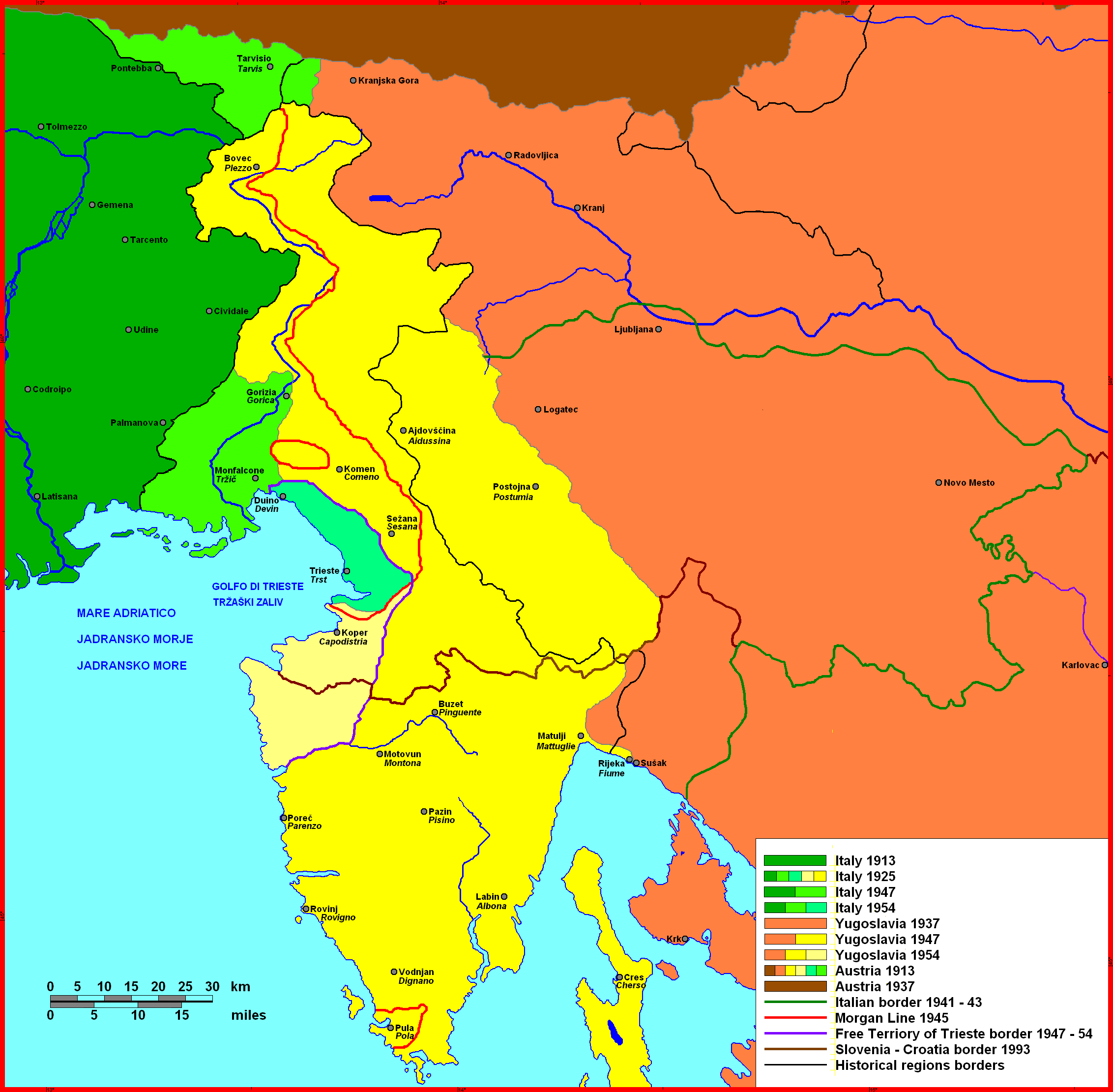

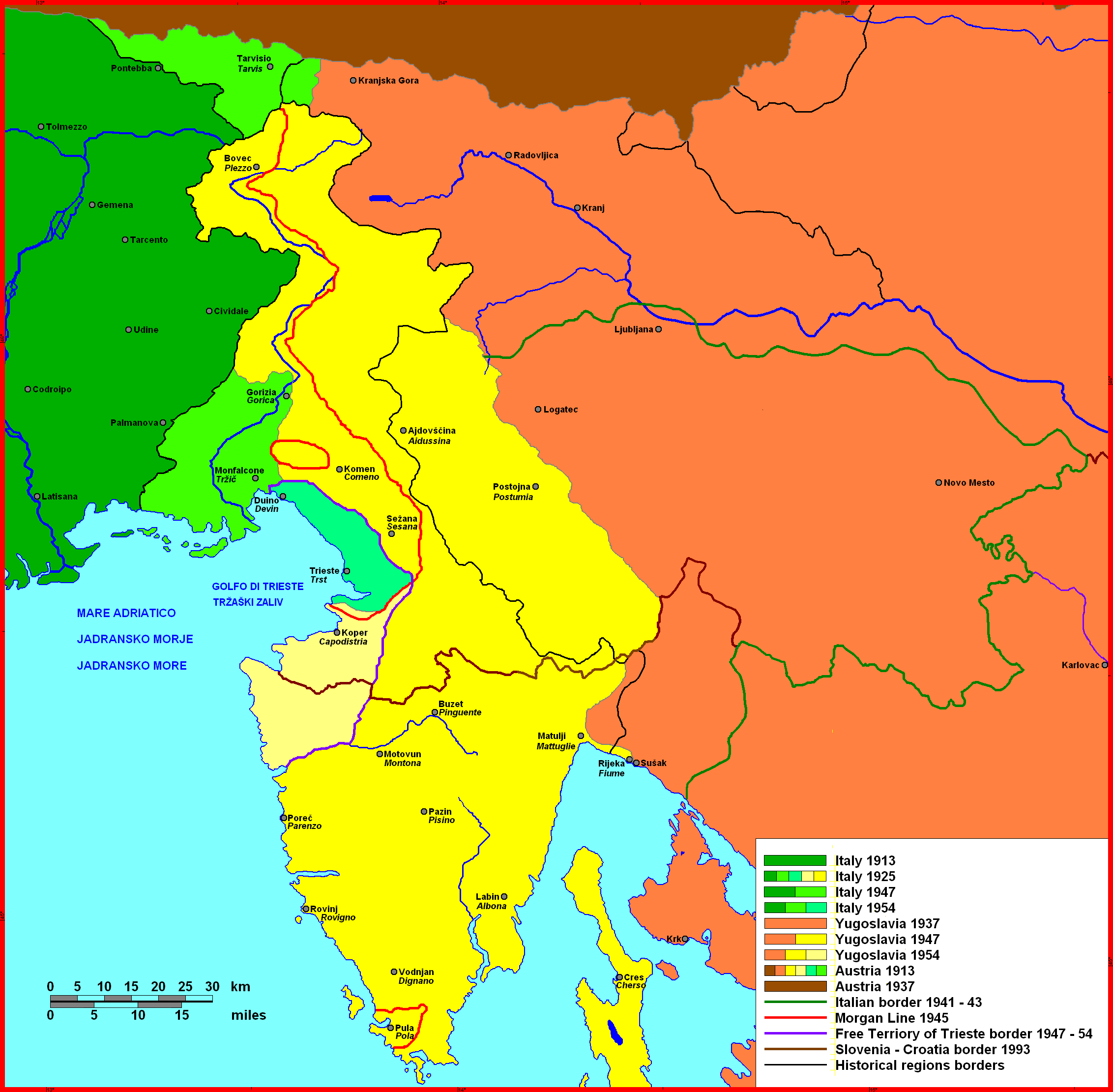

. After lingering tensions after the war over the status of the Free Territory of Trieste

The Free Territory of Trieste was an independent territory in Southern Europe between Italy and SFR Yugoslavia, Yugoslavia, facing the north part of the Adriatic Sea, under United Nations Security Council Resolution 16, direct responsibility of ...

, relations improved during the Cold War

The Cold War was a period of global Geopolitics, geopolitical rivalry between the United States (US) and the Soviet Union (USSR) and their respective allies, the capitalist Western Bloc and communist Eastern Bloc, which lasted from 1947 unt ...

.

Interwar period (1918–40)

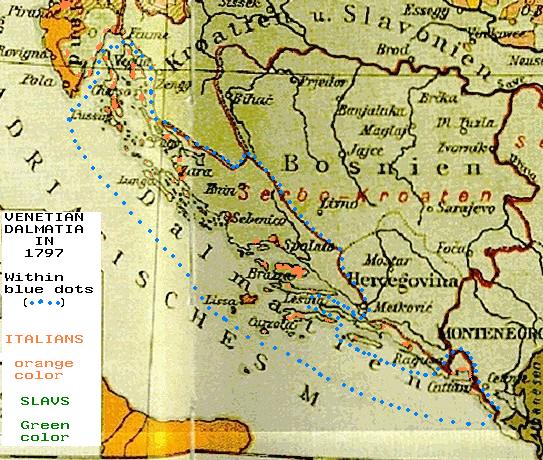

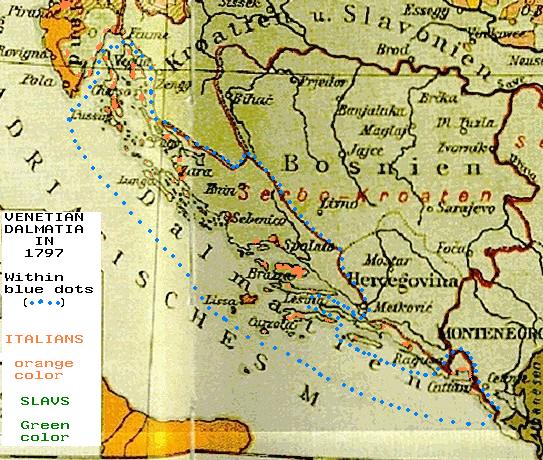

Border in Dalmatia

On 26 April 1915, the

On 26 April 1915, the Kingdom of Italy

The Kingdom of Italy (, ) was a unitary state that existed from 17 March 1861, when Victor Emmanuel II of Kingdom of Sardinia, Sardinia was proclamation of the Kingdom of Italy, proclaimed King of Italy, until 10 June 1946, when the monarchy wa ...

signed the secret Treaty of London with members of the Triple Entente

The Triple Entente (from French meaning "friendship, understanding, agreement") describes the informal understanding between the Russian Empire, the French Third Republic, and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. It was built upon th ...

. According to the pact, Italy was to declare war against the Triple Alliance; in exchange, she was to receive the Julian March

The Julian March ( Croatian and ), also called Julian Venetia (; ; ; ), is an area of southern Central Europe which is currently divided among Croatia, Italy, and Slovenia.

, northern Dalmatia

Dalmatia (; ; ) is a historical region located in modern-day Croatia and Montenegro, on the eastern shore of the Adriatic Sea. Through time it formed part of several historical states, most notably the Roman Empire, the Kingdom of Croatia (925 ...

and the protectorate over Albania

Albania ( ; or ), officially the Republic of Albania (), is a country in Southeast Europe. It is located in the Balkans, on the Adriatic Sea, Adriatic and Ionian Seas within the Mediterranean Sea, and shares land borders with Montenegro to ...

.

In March 1918, Ante Trumbić

Ante Trumbić (17 May 1864 – 17 November 1938) was a Yugoslav and Croatian lawyer and politician in the early 20th century.

Biography

Trumbić was born in Split in the Austrian crownland of Dalmatia and studied law at Zagreb, Vienna and G ...

, of the Yugoslav Committee

The Yugoslav Committee (, , ) was a World War I-era, unelected, '' ad-hoc'' committee. It largely consisted of émigré Croat, Slovene, and Bosnian Serb politicians and political activists whose aim was the detachment of Austro-Hungarian l ...

and the Italian representative, Andrea Torre, signed an agreement which clearly stated that the future border

Borders are generally defined as geography, geographical boundaries, imposed either by features such as oceans and terrain, or by polity, political entities such as governments, sovereign states, federated states, and other administrative divisio ...

between the Kingdom of Yugoslavia

The Kingdom of Yugoslavia was a country in Southeast Europe, Southeast and Central Europe that existed from 1918 until 1941. From 1918 to 1929, it was officially called the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes, but the term "Yugoslavia" () h ...

(the union of the Kingdom of Serbia

The Kingdom of Serbia was a country located in the Balkans which was created when the ruler of the Principality of Serbia, Milan I of Serbia, Milan I, was proclaimed king in 1882. Since 1817, the Principality was ruled by the Obrenović dynast ...

and the State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs

The State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs ( / ; ) was a political entity that was constituted in October 1918, at the end of World War I, by Slovenes, Croats and Serbs (Prečani (Serbs), Prečani) residing in what were the southernmost parts of th ...

) would be decided in a democratic way.

In November 1918, after the surrender of Austria-Hungary following the Armistice of Villa Giusti

The Armistice of Villa Giusti or Padua Armistice was an armistice convention with Austria-Hungary which de facto ended warfare between Allies and Associated Powers and Austria-Hungary during World War I. Italy represented the Allies and Associat ...

, Italy occupied militarily the Julian March

The Julian March ( Croatian and ), also called Julian Venetia (; ; ; ), is an area of southern Central Europe which is currently divided among Croatia, Italy, and Slovenia.

, Istria

Istria ( ; Croatian language, Croatian and Slovene language, Slovene: ; Italian language, Italian and Venetian language, Venetian: ; ; Istro-Romanian language, Istro-Romanian: ; ; ) is the largest peninsula within the Adriatic Sea. Located at th ...

, the Kvarner Gulf

The Kvarner Gulf (, or ; ; or ) sometimes also Kvarner Bay, is a bay in the northern Adriatic Sea, located between the Istrian peninsula and the northern Croatian Littoral mainland. The bay is a part of Croatia's internal waters.

The largest is ...

and Dalmatia

Dalmatia (; ; ) is a historical region located in modern-day Croatia and Montenegro, on the eastern shore of the Adriatic Sea. Through time it formed part of several historical states, most notably the Roman Empire, the Kingdom of Croatia (925 ...

, all Austro-Hungarian territories. On the Dalmatian coast, Italy established the Governorate of Dalmatia

The Governorate of Dalmatia (; ) was an administrative division of the Kingdom of Italy that existed during two periods, first from 1918 to 1920 and then from 1941 to 1943. The first Governorate of Dalmatia was established following the end of Wo ...

, which had the provisional aim of ferrying the territory towards full integration into the Kingdom of Italy, progressively importing national legislation in place of the previous one.

However, the Treaty of London was nullified in the Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles was a peace treaty signed on 28 June 1919. As the most important treaty of World War I, it ended the state of war between Germany and most of the Allies of World War I, Allied Powers. It was signed in the Palace ...

due to the objections of American president Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was the 28th president of the United States, serving from 1913 to 1921. He was the only History of the Democratic Party (United States), Democrat to serve as president during the Prog ...

. Italy received only the Julian March

The Julian March ( Croatian and ), also called Julian Venetia (; ; ; ), is an area of southern Central Europe which is currently divided among Croatia, Italy, and Slovenia.

, the Dalmatian city of Zara (Zadar), as well as the islands of Cherso (Cres), Lussino (Lošinj) and Lagosta (Lastovo). A large number of Dalmatian Italians

Dalmatian Italians (; ) are the historical Italian national minority living in the region of Dalmatia, now part of Croatia and Montenegro.

Historically, Italian language-speaking Dalmatians accounted for 12.5% of population in 1865, 5.8% in 18 ...

, (allegedly nearly 20,000), moved from the areas of Dalmatia assigned to Yugoslavia and resettled in Italy

Italy, officially the Italian Republic, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe, Western Europe. It consists of Italian Peninsula, a peninsula that extends into the Mediterranean Sea, with the Alps on its northern land b ...

(mainly in Zara). Following the conclusion of World War I and the disintegration of Austria-Hungary, Dalmatia became part of the newly formed Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes

The Kingdom of Yugoslavia was a country in Southeast and Central Europe that existed from 1918 until 1941. From 1918 to 1929, it was officially called the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes, but the term "Yugoslavia" () has been its colloq ...

(later renamed the Kingdom of Yugoslavia

The Kingdom of Yugoslavia was a country in Southeast Europe, Southeast and Central Europe that existed from 1918 until 1941. From 1918 to 1929, it was officially called the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes, but the term "Yugoslavia" () h ...

).

After the failure of a border agreement at the Paris Peace Conference, discussions continued between the Kingdom of Italy and the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. During 1920 the Italian government was under internal pressure to expand her borders as fair compensation for war victims and war debt. An example of this pressure was the publication of a forged

Forging is a manufacturing process involving the shaping of metal using localized compression (physics), compressive forces. The blows are delivered with a hammer (often a power hammer) or a die (manufacturing), die. Forging is often classif ...

letter purporting to be from Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln (February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was the 16th president of the United States, serving from 1861 until Assassination of Abraham Lincoln, his assassination in 1865. He led the United States through the American Civil War ...

to Macedonio Melloni

Macedonio Melloni (11 April 1798 – 11 August 1854) was an Italian physicist, notable for demonstrating that radiant heat has similar physical properties to those of light.

Life

Born at Parma, in 1824 he was appointed professor at the local Uni ...

, in which Lincoln had apparently acknowledged all the coast between Venice

Venice ( ; ; , formerly ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto Regions of Italy, region. It is built on a group of 118 islands that are separated by expanses of open water and by canals; portions of the city are li ...

and Cattaro

Kotor (Cyrillic: Котор, ), historically known as Cattaro (from Italian: ), is a town in Coastal region of Montenegro. It is located in a secluded part of the Bay of Kotor. The city has a population of 13,347 and is the administrative cen ...

as Italian national territory. Relations seemed to settle with the signing of the Treaty of Rapallo, the annexation by Italy of the Free State of Fiume

The Free State of Fiume () was an independent free state that existed from 1920 to 1924. Its territory of comprised the city of Fiume (today Rijeka, Croatia) and rural areas to its north, with a corridor to its west connecting it to the Kingdo ...

and the evacuation of the Governorate of Dalmatia.

Relations with the Kingdom of Yugoslavia were severely affected and constantly remained tense, because of the dispute over Dalmatia

Dalmatia (; ; ) is a historical region located in modern-day Croatia and Montenegro, on the eastern shore of the Adriatic Sea. Through time it formed part of several historical states, most notably the Roman Empire, the Kingdom of Croatia (925 ...

and over the city-port of Fiume (Rijeka). It had become a free state according to the League of Nations

The League of Nations (LN or LoN; , SdN) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference (1919–1920), Paris Peace ...

, but was occupied by some Italian rebels led by the writer Gabriele d'Annunzio. In 1924 the city was divided between Italy and Yugoslavia (the Treaty of Rapallo). Fascism

Fascism ( ) is a far-right, authoritarian, and ultranationalist political ideology and movement. It is characterized by a dictatorial leader, centralized autocracy, militarism, forcible suppression of opposition, belief in a natural social hie ...

came to Italy in 1922. Their policies included nationalistic Italianization

Italianization ( ; ; ; ; ; ) is the spread of Italian culture, language and identity by way of integration or assimilation. It is also known for a process organized by the Kingdom of Italy to force cultural and ethnic assimilation of the nati ...

courses of action, under which minority rights

Minority rights are the normal individual rights as applied to members of racial, ethnic, class, religious, linguistic or gender and sexual minorities, and also the collective rights accorded to any minority group.

Civil-rights movements oft ...

were severely reduced.

In 1925, the two countries signed the Treaty of Nettuno, but it took until 1928 before it was ratified in the Yugoslav parliament, after the assassination of Stjepan Radić

Assassination is the willful killing, by a sudden, secret, or planned attack, of a personespecially if prominent or important. It may be prompted by political, ideological, religious, financial, or military motives.

Assassinations are orde ...

.

Albania issue

Before becoming the ''

Before becoming the ''Duce

( , ) is an Italian title, derived from the Latin word , 'leader', and a cognate of ''duke''. National Fascist Party leader Benito Mussolini was identified by Fascists as ('The Leader') of the movement since the birth of the in 1919. In 192 ...

'' of Italy, Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who, upon assuming office as Prime Minister of Italy, Prime Minister, became the dictator of Fascist Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 un ...

had clearly stated his thinking about Yugoslavia. He was creating a difference towards Serbia in which "Italy will always have friendly policy but with Yugoslavia she will have good relationship only if she accept that her destiny is n the Aegean and not heAdriatic Sea

The Adriatic Sea () is a body of water separating the Italian Peninsula from the Balkans, Balkan Peninsula. The Adriatic is the northernmost arm of the Mediterranean Sea, extending from the Strait of Otranto (where it connects to the Ionian Se ...

". The relationship between the two states ended after the signing of a friendship pact between the Kingdoms of Italy and Albania on 27 November 1926. This was the reason Yugoslavian minister of foreign affairs Momčilo Ninčić resigned his office, which also prompted others in the government to followed his suit. Ninčić did that "on the ground that the check sustained by his policy impelled him to take such a step".

With this pact, in the eyes of King Alexander

Alexander () is a male name of Greek origin. The most prominent bearer of the name is Alexander the Great, the king of the Ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia who created one of the largest empires in ancient history.

Variants listed here ar ...

, Italy entered the Yugoslav zone of influence; Mussolini was not interested in diplomatic protests from Belgrade

Belgrade is the Capital city, capital and List of cities in Serbia, largest city of Serbia. It is located at the confluence of the Sava and Danube rivers and at the crossroads of the Pannonian Basin, Pannonian Plain and the Balkan Peninsula. T ...

; Yugoslavia signed a secret military pact with France on 11 November 1927.

During this time the first contact between Ante Pavelić

Ante Pavelić (; 14 July 1889 – 28 December 1959) was a Croatian politician who founded and headed the fascist ultranationalist organization known as the Ustaše in 1929 and was dictator of the Independent State of Croatia (NDH), a fasc ...

(who wanted Italian help for the destruction of Yugoslavia) and the creation of an independent Croatia with official representatives from Italy. After the proclamation of a dictatorship in Yugoslavia, Ante Pavelić left "his" country and went into exile in Italy in October 1929. Mussolini gave the job of approaching and helping Croatian separatists to Italian parliamentary member Fulvio Suvich Fulvio is a given name. Notable people with the name include:

*Andrea Fulvio (c. 1470 – 1527), Renaissance humanist, poet and antiquarian of Rome, advisor to Raphael

*Fulvio de Assis (born 1981), Brazilian professional basketball player

*Fulvio B ...

in 1929.

After the proclamation of the 6 January Dictatorship, relations with the neighboring states remained "one of the chief concerns of the Belgrade Government". The Yugoslavian government was keenly interested in the renewal of the pact of friendship between Italy and Yugoslavia signed in Rome in 1924. Both the Foreign Minister Vojislav Marinković and the Acting Foreign Minister Kosta Kumanudi shared the same views on external affairs. The Prime Minister Petar Živković stated that the policy of his Government "would be peaceful and follow the same lines as those pursued heretofore by King Alexander's Government's." Nevertheless, the Yugoslav Government continued to monitor internal events in Albania, especially the crisis that forced Elias Vrioni, who had been regarded as "in very close touch with Mussolini", to leave the Tirana Government.

This poor relationship between the two kingdoms were best shown in the events of 1928 and 1929. The first diplomatic problems were born when Zog I

Zog I (born Ahmed Muhtar Zogolli; 8 October 18959 April 1961) was the leader of Albania from 1922 to 1939. At age 27, he first served as Albania's youngest ever Prime Minister (1922–1924), then as president (1925–1928), and finally as King ...

of Albania, with Italian help, proclaimed himself King of the Albanians

The King of Albania (Albanian language, Albanian: ''Mbreti i Shqipërisë'') was a title styled by the official ruler of Albania. While the medieval Capetian House of Anjou, AngevinKingdom of Albania (medieval), Kingdom of Albania was a monarchy, ...

. The majority of the population in Yugoslavian Kosovo

Kosovo, officially the Republic of Kosovo, is a landlocked country in Southeast Europe with International recognition of Kosovo, partial diplomatic recognition. It is bordered by Albania to the southwest, Montenegro to the west, Serbia to the ...

during this period were Albanians

The Albanians are an ethnic group native to the Balkan Peninsula who share a common Albanian ancestry, Albanian culture, culture, Albanian history, history and Albanian language, language. They are the main ethnic group of Albania and Kosovo, ...

in Yugoslavian eyes; this proclamation became an invitation for the creation of Greater Albania

Greater Albania () is an irredentist and nationalist concept that seeks to annex the lands that many Albanians consider to form their national homeland. It is based on claims on the present-day or historical presence of Albanian populations in ...

with Italian help. These fears were confirmed in 1929 when Italy refused to sign a new friendship agreement with Yugoslavia. The following year she allowed Ante Pavelić to live in Italy where he organized the Ustaše

The Ustaše (), also known by anglicised versions Ustasha or Ustashe, was a Croats, Croatian fascist and ultranationalist organization active, as one organization, between 1929 and 1945, formally known as the Ustaša – Croatian Revolutionar ...

(a Croatian fascist anti-Yugoslav movement).

Yugoslavia commenced secret negotiations with Italy in late 1930. To put more pressure on Belgrade

Belgrade is the Capital city, capital and List of cities in Serbia, largest city of Serbia. It is located at the confluence of the Sava and Danube rivers and at the crossroads of the Pannonian Basin, Pannonian Plain and the Balkan Peninsula. T ...

, Mussolini made a few speeches with the words "Dalmazia o morte" (Dalmatia or death); but the real demand was that Yugoslavia accept Italian supremacy in Albania. When this offer was refused in 1932, Yugoslavia started to look for new allies against his demands. Consequently, Yugoslavia signed a trade agreement with Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany, officially known as the German Reich and later the Greater German Reich, was the German Reich, German state between 1933 and 1945, when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party controlled the country, transforming it into a Totalit ...

in March 1934.

Later years

The Yugoslav kingAlexander

Alexander () is a male name of Greek origin. The most prominent bearer of the name is Alexander the Great, the king of the Ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia who created one of the largest empires in ancient history.

Variants listed here ar ...

was killed on 9 October 1934 by members of the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization

The Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (IMRO; ; ), was a secret revolutionary society founded in the Ottoman territories in Europe, that operated in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Founded in 1893 in Salonica, it initia ...

, helped by the Ustaše

The Ustaše (), also known by anglicised versions Ustasha or Ustashe, was a Croats, Croatian fascist and ultranationalist organization active, as one organization, between 1929 and 1945, formally known as the Ustaša – Croatian Revolutionar ...

. Italy was criticised for helping and financing them, sending all members to closed training camps where they received Italian support and control. The Ustaše did not forget the unfriendly actions taken by the Italian "controller" Ercole Conti.

Upon pressure from France, the Kingdom of Yugoslavia did not raise the issue of Italian international responsibilities in the regicide

Regicide is the purposeful killing of a monarch or sovereign of a polity and is often associated with the usurpation of power. A regicide can also be the person responsible for the killing. The word comes from the Latin roots of ''regis'' ...

before the League of Nations

The League of Nations (LN or LoN; , SdN) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference (1919–1920), Paris Peace ...

. After the coming to power of Milan Stojadinović

Milan Stojadinović ( sr-Cyrl, Милан Стојадиновић; 4 August 1888 – 26 October 1961) was a Serbs, Serbian and Kingdom of Yugoslavia, Yugoslav politician and economist who was the Prime Minister of Yugoslavia from 1935 to 1939. ...

, the relationship between the two kingdoms improved. A trade agreement

A trade agreement (also known as trade pact) is a wide-ranging taxes, tariff and trade treaty that often includes investment guarantees. It exists when two or more countries agree on terms that help them trade with each other. The most common tra ...

was signed on 1 October 1936, followed by renewed negotiations which resulted in the signing of further agreements on 25 March 1937 stating the commencement of an officially friendly relationship. An agreement was also signed settling all border issues, while Italy provided information to Yugoslavia about the identities and place of residence for 510 Ustaše members. In 1939, Galeazzo Ciano

Gian Galeazzo Ciano, 2nd Count of Cortellazzo and Buccari ( , ; 18 March 1903 – 11 January 1944), was an Italian diplomat and politician who served as Italian Minister of Foreign Affairs, Foreign Minister in the government of his father-in-law ...

directly negotiated with Milan Stojadinović

Milan Stojadinović ( sr-Cyrl, Милан Стојадиновић; 4 August 1888 – 26 October 1961) was a Serbs, Serbian and Kingdom of Yugoslavia, Yugoslav politician and economist who was the Prime Minister of Yugoslavia from 1935 to 1939. ...

the annexation of Albania

Albania ( ; or ), officially the Republic of Albania (), is a country in Southeast Europe. It is located in the Balkans, on the Adriatic Sea, Adriatic and Ionian Seas within the Mediterranean Sea, and shares land borders with Montenegro to ...

by Italy. On that occasion, the Yugoslav regent Prince Pavle

Prince Paul of Yugoslavia, also known as Paul Karađorđević (, English transliteration: ''Paul Karageorgevich''; 27 April 1893 – 14 September 1976), was prince regent of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia during the minority of King Peter II of Yugos ...

, fired and arrested Stojadinović; from then on, Italian-Yugoslav relations rapidly deteriorated.

In the last two years before the start of World War II, Italy almost broke off diplomatic contact with Yugoslavia and started negotiations with Germany and the Ustaše. Italy recalled General Gastone Gambara from Spain in 1940 so that he could take control of forces which would attack Banovina of Croatia

The Banovina of Croatia or Banate of Croatia ( sh-Latn-Cyrl, separator=, Banovina Hrvatska, Бановина Хрватска) was an administrative subdivision ( banovina) of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia between 1939 and 1941. It was formed by a m ...

(a Yugoslav province). This offensive was only delayed because of the Italian declaration of war against France on 10 June 1940. Italy created plans of attack on Yugoslavia in February 1940 with the primary objective of taking Šibenik

Šibenik (), historically known as Sebenico (), is a historic town in Croatia, located in central Dalmatia, where the river Krka (Croatia), Krka flows into the Adriatic Sea. Šibenik is one of the oldest Croatia, Croatian self-governing cities ...

, Split

Split(s) or The Split may refer to:

Places

* Split, Croatia, the largest coastal city in Croatia

* Split Island, Canada, an island in the Hudson Bay

* Split Island, Falkland Islands

* Split Island, Fiji, better known as Hạfliua

Arts, enter ...

and Kotor

Kotor (Cyrillic script, Cyrillic: Котор, ), historically known as Cattaro (from Italian language, Italian: ), is a town in Coastal Montenegro, Coastal region of Montenegro. It is located in a secluded part of the Bay of Kotor. The city has ...

so that the Adriatic situation would be eased. The only problem with this plan was that Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (20 April 1889 – 30 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was the dictator of Nazi Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his suicide in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the lea ...

wanted to create an alliance between the two kingdoms against Greece

Greece, officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. Located on the southern tip of the Balkan peninsula, it shares land borders with Albania to the northwest, North Macedonia and Bulgaria to the north, and Turkey to th ...

. During negotiations in late 1940, Italy offered Thessaloniki

Thessaloniki (; ), also known as Thessalonica (), Saloniki, Salonika, or Salonica (), is the second-largest city in Greece (with slightly over one million inhabitants in its Thessaloniki metropolitan area, metropolitan area) and the capital cit ...

to Yugoslavia but it was rejected. Only when Hitler put forward a similar offer in March 1941 was it accepted, and Yugoslavia become a member of the Axis powers

The Axis powers, originally called the Rome–Berlin Axis and also Rome–Berlin–Tokyo Axis, was the military coalition which initiated World War II and fought against the Allies of World War II, Allies. Its principal members were Nazi Ge ...

on 25 March 1941. Hitler ordered an attack on Yugoslavia following the coup d'état on 27 March; two days later the new Yugoslav prime minister, Dušan Simović

Dušan Simović (; 28 October 1882 – 26 August 1962) was a Yugoslav Serb Army general (Kingdom of Yugoslavia), army general who served as Chief of the General Staff (Yugoslavia)#Royal Yugoslav Armed Forces (1920–1941), Chief of the General Sta ...

, asked for Italian help in restoring relations with Germany. Simović warned Italy that Yugoslavia would overrun Italian Albania if the Axis powers declared war. This war would start on 6 April 1941 and end with the destruction of the Yugoslav Kingdom on 17 April.

Second World War (1940–45)

Italian-German invasion of Yugoslavia

The

The Invasion of Yugoslavia

The invasion of Yugoslavia, also known as the April War or Operation 25, was a Nazi Germany, German-led attack on the Kingdom of Yugoslavia by the Axis powers which began on 6 April 1941 during World War II. The order for the invasion was put fo ...

(code-name Directive 25 or Operation 25) was the Axis powers

The Axis powers, originally called the Rome–Berlin Axis and also Rome–Berlin–Tokyo Axis, was the military coalition which initiated World War II and fought against the Allies of World War II, Allies. Its principal members were Nazi Ge ...

' attack on the Kingdom of Yugoslavia which began on 6 April 1941 during World War II. The invasion ended with the unconditional surrender of the Royal Yugoslav Army

The Yugoslav Army ( sh-Latn-Cyrl, Jugoslovenska vojska, JV, Југословенска војска, ЈВ), commonly the Royal Yugoslav Army, was the principal Army, ground force of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. It existed from the establishment of ...

on 17 April 1941, the annexation and occupation of the region by the Axis powers and the creation of the Independent State of Croatia

The Independent State of Croatia (, NDH) was a World War II–era puppet state of Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy (1922–1943), Fascist Italy. It was established in parts of Axis occupation of Yugoslavia, occupied Yugoslavia on 10 April 1941, ...

(''Nezavisna Država Hrvatska'', or NDH). Italy annexed the area constituting the province of Ljubljana

The Province of Ljubljana (, , ) was the central-southern area of Slovenia. In 1941, it was annexed by the Kingdom of Italy, and after 1943 occupied by Nazi Germany. Created on May 3, 1941, it was abolished on May 9, 1945, when the Slovene Parti ...

, the area merged with the province of Fiume

The Province of Fiume (or Province of Carnaro) was a province of the Kingdom of Italy from 1924 to 1943, then under control of the Italian Social Republic and German Wehrmacht from 1943 to 1945. Its capital was the city of Rijeka, Fiume. It too ...

and the areas making up the second Governorate of Dalmatia

The Governorate of Dalmatia (; ) was an administrative division of the Kingdom of Italy that existed during two periods, first from 1918 to 1920 and then from 1941 to 1943. The first Governorate of Dalmatia was established following the end of Wo ...

.

The Italian Second Army crossed the border soon after the Germans. They faced the Yugoslavian Seventh Army. The Italians encountered limited resistance and occupied parts of Slovenia

Slovenia, officially the Republic of Slovenia, is a country in Central Europe. It borders Italy to the west, Austria to the north, Hungary to the northeast, Croatia to the south and southeast, and a short (46.6 km) coastline within the Adriati ...

, Croatia

Croatia, officially the Republic of Croatia, is a country in Central Europe, Central and Southeast Europe, on the coast of the Adriatic Sea. It borders Slovenia to the northwest, Hungary to the northeast, Serbia to the east, Bosnia and Herze ...

, and the coast of Dalmatia

Dalmatia (; ; ) is a historical region located in modern-day Croatia and Montenegro, on the eastern shore of the Adriatic Sea. Through time it formed part of several historical states, most notably the Roman Empire, the Kingdom of Croatia (925 ...

. In addition to the Second Army, Italy had four divisions of the Ninth Army on the Yugoslavian border with Albania. These formations were so situated against a Yugoslav offensive on that front. Around 300 Ustaše volunteers under the command of Ante Pavelic accompanied the Italian Second Army during the invasion; about the same number of Ustaše were attached to the German Army

The German Army (, 'army') is the land component of the armed forces of Federal Republic of Germany, Germany. The present-day German Army was founded in 1955 as part of the newly formed West German together with the German Navy, ''Marine'' (G ...

and other Axis allies.

The Independent State of Croatia was founded on 10 April 1941, after the invasion of Yugoslavia by the Axis powers. The state was technically a monarchy and Italian protectorate

A protectorate, in the context of international relations, is a State (polity), state that is under protection by another state for defence against aggression and other violations of law. It is a dependent territory that enjoys autonomy over ...

from the signing of the Rome agreements on 19 May 1941 until the Italian capitulation on 8 September 1943; but the king-designate, the Prince Aimone of Savoy-Aosta, refused to assume the kingship in opposition to the Italian annexation of the Croat

The Croats (; , ) are a South Slavs, South Slavic ethnic group native to Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina and other neighboring countries in Central Europe, Central and Southeastern Europe who share a common Croatian Cultural heritage, ancest ...

-populated Yugoslav region of Dalmatia.

End of the war

When the Fascist regime collapsed in 1943 and Italy capitulated, its eastern border territory was occupied by German forces, the authority of the

When the Fascist regime collapsed in 1943 and Italy capitulated, its eastern border territory was occupied by German forces, the authority of the Italian Social Republic

The Italian Social Republic (, ; RSI; , ), known prior to December 1943 as the National Republican State of Italy (; SNRI), but more popularly known as the Republic of Salò (, ), was a List of World War II puppet states#Germany, German puppe ...

in this zone being largely theoretical. The Yugoslav 4th Army, together with the Slovenian 9th Corps entered Trieste

Trieste ( , ; ) is a city and seaport in northeastern Italy. It is the capital and largest city of the Regions of Italy#Autonomous regions with special statute, autonomous region of Friuli-Venezia Giulia, as well as of the Province of Trieste, ...

on 1 May 1945. The 2nd (New Zealand) Division of the British 8th Army arrived the next day and forced the surrender of 2,000 German Army

The German Army (, 'army') is the land component of the armed forces of Federal Republic of Germany, Germany. The present-day German Army was founded in 1955 as part of the newly formed West German together with the German Navy, ''Marine'' (G ...

soldiers holding out in Trieste which had refused to capitulate to partisan troops. An uneasy truce developed between Allied and Yugoslav troops occupying the area until British General Sir William Morgan proposed a partition of the territory and the removal of Yugoslav troops from the area occupied by the Allies. Josip Broz Tito

Josip Broz ( sh-Cyrl, Јосип Броз, ; 7 May 1892 – 4 May 1980), commonly known as Tito ( ; , ), was a Yugoslavia, Yugoslav communist revolutionary and politician who served in various positions of national leadership from 1943 unti ...

agreed in principle on 23 May as the British XIII Corps was moving forward to the proposed demarcation line. An agreement was signed in Duino

Duino (, ) is today a seaside resort on the northern Adriatic Sea, Adriatic coast. It is a ''hamlet (place), hamlet'' of Duino-Aurisina, a municipality (''comune'') of the Friuli–Venezia Giulia region of northeastern Italy. The settlement, pict ...

on 10 June, creating the Morgan Line

The Morgan Line (, ) was the line of demarcation set up after World War II in the region known as Julian March which prior to the war belonged to the Kingdom of Italy. The Morgan Line was the border between two military administrations in the reg ...

. Yugoslav soldiers withdrew by 12 June 1945.

The end of the war on the Italian-Yugoslav border, after the Italian capitulation on 8 September 1943, was marked by the

The end of the war on the Italian-Yugoslav border, after the Italian capitulation on 8 September 1943, was marked by the foibe massacres

The foibe massacres (; ; ), or simply the foibe, refers to ethnic cleansing, mass killings and deportations both during and immediately after World War II, mainly committed by Yugoslav Partisans and OZNA in the Italian Empire, then-Italian terri ...

(perpetrated by Yugoslav partisans) that took place mainly in Istria

Istria ( ; Croatian language, Croatian and Slovene language, Slovene: ; Italian language, Italian and Venetian language, Venetian: ; ; Istro-Romanian language, Istro-Romanian: ; ; ) is the largest peninsula within the Adriatic Sea. Located at th ...

from 1946 to 1949, the Istrian–Dalmatian exodus

The Istrian–Dalmatian exodus (; ; ) was the post-World War II exodus and departure of local ethnic Italians (Istrian Italians and Dalmatian Italians) as well as ethnic Slovenes and Croats from Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, Yugosla ...

, which involved the emigration of around 350,000 Istrian Italians

Istrian Italians (; ; ) are an ethnic group from the Adriatic region of Istria in modern northwestern Croatia and southwestern Slovenia. Istrian Italians descend from the original Latinized population of Roman Histria, from the Venetian-speaki ...

and Dalmatian Italians

Dalmatian Italians (; ) are the historical Italian national minority living in the region of Dalmatia, now part of Croatia and Montenegro.

Historically, Italian language-speaking Dalmatians accounted for 12.5% of population in 1865, 5.8% in 18 ...

, and the issue of Trieste.

The Istrian-Dalmatian exodus indicates the departure of ethnic

An ethnicity or ethnic group is a group of people with shared attributes, which they collectively believe to have, and long-term endogamy. Ethnicities share attributes like language, culture, common sets of ancestry, traditions, society, re ...

Italians from Istria, Rijeka

Rijeka (;

Fiume ( �fjuːme in Italian and in Fiuman dialect, Fiuman Venetian) is the principal seaport and the List of cities and towns in Croatia, third-largest city in Croatia. It is located in Primorje-Gorski Kotar County on Kvarner Ba ...

(Fiume) and Dalmatia after World War II. At the time of the exodus, these territories were part of the SR Croatia

The Socialist Republic of Croatia ( sh-Latn-Cyrl, separator=" / ", Socijalistička Republika Hrvatska, Социјалистичка Република Хрватска), commonly abbreviated as SR Croatia and referred to as simply Croatia, was a ...

and SR Slovenia

The Socialist Republic of Slovenia (, sh-Latn-Cyrl, separator=" / ", Socijalistička Republika Slovenija, Социјалистичка Република Словенија), commonly referred to as Socialist Slovenia or simply Slovenia, was one ...

(then parts of SFR Yugoslavia). According to some sources, the exodus was incited by the Yugoslav government, while the Italian government offered incentives for immigration. These territories were ethnically mixed, with Italian, Slovenian, Croatian, Serbian and other communities. Istria, including Rijeka and parts of Dalmatia, including Zadar

Zadar ( , ), historically known as Zara (from Venetian and Italian, ; see also other names), is the oldest continuously inhabited city in Croatia. It is situated on the Adriatic Sea, at the northwestern part of Ravni Kotari region. Zadar ...

, had been annexed to Italy after World War I.

From 1947, after the war, Istrian Italians and Dalmatian Italians were subject by Yugoslav authorities to less violent forms of intimidation, such as nationalization, expropriation, and discriminatory taxation, which gave them little option other than emigration. The exodus started in 1943 and ended completely only in 1960. According to the census organized in Croatia

Croatia, officially the Republic of Croatia, is a country in Central Europe, Central and Southeast Europe, on the coast of the Adriatic Sea. It borders Slovenia to the northwest, Hungary to the northeast, Serbia to the east, Bosnia and Herze ...

in 2001 and that organized in Slovenia

Slovenia, officially the Republic of Slovenia, is a country in Central Europe. It borders Italy to the west, Austria to the north, Hungary to the northeast, Croatia to the south and southeast, and a short (46.6 km) coastline within the Adriati ...

in 2002, the Italians who remained in the former Yugoslavia

, common_name = Yugoslavia

, life_span = 1918–19921941–1945: World War II in Yugoslavia#Axis invasion and dismemberment of Yugoslavia, Axis occupation

, p1 = Kingdom of SerbiaSerbia

, flag_p ...

amounted to 21,894 people (2,258 in Slovenia and 19,636 in Croatia).

In 1991 Milovan Đilas

Milovan Djilas (; sr-Cyrl-Latn, Милован Ђилас, Milovan Đilas, ; 12 June 1911 – 20 April 1995) was a Yugoslav communist politician, theorist and author. He was a key figure in the Partisan movement during World War II, as well ...

was to say "''I remember that in 1946 me and Edvard Kardelj went to Istria to organize the anti-Italian propaganda. It was all about proving to the Allied Commission that those lands were Yugoslav and not Italian: we organized manifestations with signs and flags.''

''But wasn't it true?'' (journalist's question)

''Of course it wasn't. Better still, it was just partly true, because in reality Italians were the majority in the towns, not in the villages. It was therefore necessary to persuade them to leave with every kind of pressions. So it was told us and so it was done.''"

At the end of World War II the former Italian territories in Istria and Dalmatia became part of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia

The Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (commonly abbreviated as SFRY or SFR Yugoslavia), known from 1945 to 1963 as the Federal People's Republic of Yugoslavia, commonly referred to as Socialist Yugoslavia or simply Yugoslavia, was a country ...

by the Paris Peace Treaty

The Paris Peace Treaties () were signed on 10 February 1947 following the end of World War II in 1945. The Paris Peace Conference lasted from 29 July until 15 October 1946. The victorious wartime Allied powers (principally the United Kingdom, ...

(1947), the only exception being the communes of Muggia

Muggia (; ; ) is an Italian (municipality) in the Province of Trieste, regional decentralization entity of Trieste, in the region of Friuli-Venezia Giulia on the border with Slovenia. It has 12,703 inhabitants.

Lying on the eastern flank of th ...

and San Dorligo della Valle

San Dorligo della Valle (; or ) is a (municipality) in the Regional decentralization entity of Trieste in the Italian region of Friuli-Venezia Giulia, located about southeast of Trieste, on the border with Slovenia. it had a population of 6,0 ...

.

The Free Territory of Trieste

The Free Territory of Trieste was an independent territory in Southern Europe between Italy and SFR Yugoslavia, Yugoslavia, facing the north part of the Adriatic Sea, under United Nations Security Council Resolution 16, direct responsibility of ...

was established by demand of the United Nations Security Council

The United Nations Security Council (UNSC) is one of the six principal organs of the United Nations (UN) and is charged with ensuring international peace and security, recommending the admission of new UN members to the General Assembly, an ...

through its Resolution 16 of January 1947, under Article 24 of the UN charter

The Charter of the United Nations is the foundational treaty of the United Nations (UN). It establishes the purposes, governing structure, and overall framework of the United Nations System, UN system, including its United Nations System#Six ...

, calling for the creation of a free state in Trieste and the region surrounding it. A permanent statute codifying its provisions was to become recognized under international law

International law, also known as public international law and the law of nations, is the set of Rule of law, rules, norms, Customary law, legal customs and standards that State (polity), states and other actors feel an obligation to, and generall ...

upon the appointment of an international governor approved by the Quatripartite Powers. On 15 September 1947, the peace treaty between the United Nations and Italy was ratified, establishing the Free Territory of Trieste. The official languages were Slovene, Italian and Croatian. However, the territory did not receive its planned self-government and it was maintained under military occupation

Military occupation, also called belligerent occupation or simply occupation, is temporary hostile control exerted by a ruling power's military apparatus over a sovereign territory that is outside of the legal boundaries of that ruling pow ...

, respecting the division into two zones as decided by the Morgan Line

The Morgan Line (, ) was the line of demarcation set up after World War II in the region known as Julian March which prior to the war belonged to the Kingdom of Italy. The Morgan Line was the border between two military administrations in the reg ...

: Zone A, which was 222.5 km2 and had 262,406 residents including Trieste, was administered by British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies.

* British national identity, the characteristics of British people and culture ...

and American forces, while Zone B, which was 515.5 km2 with 71,000 residents including north-western Istria, was administered by the Yugoslav People's Army

The Yugoslav People's Army (JNA/; Macedonian language, Macedonian, Montenegrin language, Montenegrin and sr-Cyrl-Latn, Југословенска народна армија, Jugoslovenska narodna armija; Croatian language, Croatian and ; , J ...

.

Between October 1947 and March 1948 the Soviet Union rejected the candidacy of 12 nominations for governor, at which point the Tripartite Powers (the United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

, the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Northwestern Europe, off the coast of European mainland, the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

and France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

), issued a note to Moscow

Moscow is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Russia by population, largest city of Russia, standing on the Moskva (river), Moskva River in Central Russia. It has a population estimated at over 13 million residents with ...

and Belgrade on 20 March 1948, recommending that the territory be returned to Italian sovereignty. No governor was ever appointed under the terms of the UN Resolution

A United Nations resolution (UN resolution) is a formal text adopted by a United Nations (UN) body. Although any UN body can issue resolutions, in practice most resolutions are issued by the Security Council or the General Assembly, in the f ...

. The Territory thus never functioned as a real independent state

Independence is a condition of a nation, country, or state, in which residents and population, or some portion thereof, exercise self-government, and usually sovereignty, over its territory. The opposite of independence is the status of a ...

. Even so, its formal status was generally respected and it issued its own postage stamps. The break between the Tito government and the USSR in mid-1948 resulted in the proposal to return the territory to Italy being suspended until 1954.

After World War II, Italian irredentism

Italian irredentism ( ) was a political movement during the late 19th and early 20th centuries in Kingdom of Italy, Italy with irredentism, irredentist goals which promoted the Unification of Italy, unification of geographic areas in which indig ...

disappeared along with the defeated Fascists and the Monarchy of the House of Savoy

The House of Savoy (, ) is a royal house (formally a dynasty) of Franco-Italian origin that was established in 1003 in the historical region of Savoy, which was originally part of the Kingdom of Burgundy and now lies mostly within southeastern F ...

. After the Treaty of Paris (1947) and the Treaty of Osimo (1975), all territorial claims were abandoned by the Italian Republic

Italy, officially the Italian Republic, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe, Western Europe. It consists of Italian Peninsula, a peninsula that extends into the Mediterranean Sea, with the Alps on its northern land b ...

. The Italian irredentist movement thus vanished from Italian politics.

Cold War (1945–89)

Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia

The Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (commonly abbreviated as SFRY or SFR Yugoslavia), known from 1945 to 1963 as the Federal People's Republic of Yugoslavia, commonly referred to as Socialist Yugoslavia or simply Yugoslavia, was a country ...

was one of only two European countries that were liberated by its own forces during World War II, with limited assistance and participation by the Allies. It received support from the Western democracies and the Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

, and at the end of the war no foreign troops were stationed on its soil. Partly as a result, the country found itself halfway between the two camps at the onset of the Cold War

The Cold War was a period of global Geopolitics, geopolitical rivalry between the United States (US) and the Soviet Union (USSR) and their respective allies, the capitalist Western Bloc and communist Eastern Bloc, which lasted from 1947 unt ...

.

In 1947–1948, the Soviet Union attempted to command obedience from Yugoslavia, primarily on issues of foreign policy

Foreign policy, also known as external policy, is the set of strategies and actions a State (polity), state employs in its interactions with other states, unions, and international entities. It encompasses a wide range of objectives, includ ...

, which resulted in the Tito–Stalin split

The Tito–Stalin split or the Soviet–Yugoslav split was the culmination of a conflict between the political leaderships of Yugoslavia and the Soviet Union, under Josip Broz Tito and Joseph Stalin, respectively, in the years following World W ...

and almost ignited an armed conflict. A period of very cool relations with the Soviet Union followed, during which the US and the UK considered persuading Yugoslavia into the newly formed NATO

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO ; , OTAN), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental organization, intergovernmental Transnationalism, transnational military alliance of 32 Member states of NATO, member s ...

. This changed in 1953 with the Trieste crisis, a tense dispute between Yugoslavia and the Western Allies over the eventual Yugoslav-Italian border (see Free Territory of Trieste

The Free Territory of Trieste was an independent territory in Southern Europe between Italy and SFR Yugoslavia, Yugoslavia, facing the north part of the Adriatic Sea, under United Nations Security Council Resolution 16, direct responsibility of ...

), and with Yugoslav-Soviet reconciliation in 1956. This ambivalent position at the start of the Cold War matured into the non-aligned foreign policy which Yugoslavia actively espoused until its dissolution.

The issue of the status of Trieste was finally settled with the Treaty of Osimo, signed on 10 November 1975 by the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia and the Italian Republic in Osimo

Osimo is a town and ''comune'' of the Marche region of Italy, in the province of Ancona. The municipality covers a hilly area located approximately south of the port city of Ancona and the Adriatic Sea.

History

The oldest archaeological evide ...

, Italy, to definitely divide the Free Territory of Trieste between the two states. The treaty was written in French and became effective on 11 October 1977. It was based on the memorandum of understanding signed in London in 1954, which had handed over the civil administration of Zone A to Italy and Zone B to Yugoslavia. Zone A, including the city of Trieste, became the Italian Province of Trieste

The province of Trieste () is a province in the autonomous Friuli-Venezia Giulia region of Italy. Its capital is the city of Trieste. It has an area of and a population of 228,049. It has a coastal length of . Abolished in 2017, it was reestabl ...

, but Yugoslavia was granted free access to its port.

Dissolution of Yugoslavia

The period of thebreakup of Yugoslavia

After a period of political and economic crisis in the 1980s, the constituent republics of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia split apart in the early 1990s. Unresolved issues from the breakup caused a series of inter-ethnic Yugoslav ...

coincided with a season of political scandals and turmoil in Italy (the Tangentopoli

(; ) was a nationwide judicial investigation into political corruption in Italy held in the early 1990s, resulting in the demise of the First Italian Republic and the disappearance of many political parties. Some politicians and industry leade ...

affair and Mani Pulite

(; ) was a nationwide judicial investigation into political corruption in Italy held in the early 1990s, resulting in the demise of the First Italian Republic and the disappearance of many political parties. Some politicians and industry leade ...

inquiry), which brought de-consolidation of the Italian party system and a temporary general weakness in Italian foreign policy.

In this short time frame, Italy mainly backed its allies' moves in the Yugoslav crisis, such as the February 1991 German initiative, US-inspired, of threatening economic isolation of Yugoslavia in the lack of multi-party elections. In 1992, following the US, the Vatican, and the EC, Italy recognized the independence of Slovenia

Slovenia, officially the Republic of Slovenia, is a country in Central Europe. It borders Italy to the west, Austria to the north, Hungary to the northeast, Croatia to the south and southeast, and a short (46.6 km) coastline within the Adriati ...

and Croatia

Croatia, officially the Republic of Croatia, is a country in Central Europe, Central and Southeast Europe, on the coast of the Adriatic Sea. It borders Slovenia to the northwest, Hungary to the northeast, Serbia to the east, Bosnia and Herze ...

.''Dichiarazione congiunta sullo stabilimento di relazioni diplomatiche'' (Lubiana, 17 January 1992) Italy also recognized Bosnia and Herzegovina

Bosnia and Herzegovina, sometimes known as Bosnia-Herzegovina and informally as Bosnia, is a country in Southeast Europe. Situated on the Balkans, Balkan Peninsula, it borders Serbia to the east, Montenegro to the southeast, and Croatia to th ...

and Macedonia

Macedonia (, , , ), most commonly refers to:

* North Macedonia, a country in southeastern Europe, known until 2019 as the Republic of Macedonia

* Macedonia (ancient kingdom), a kingdom in Greek antiquity

* Macedonia (Greece), a former administr ...

.

Aftermath

* Croatia–Italy relations * Italy–Montenegro relations * Italy–Slovenia relations * Italy–Serbia relationsSee also

*Foreign relations of Italy

The foreign relations of the Italian Republic are the Italian government's external relations with the outside world. Located in Europe, Italy has been considered a major Western power since its unification in 1860. Its main allies are the NA ...

* Foreign relations of Yugoslavia

Foreign relations of Yugoslavia (; ; ; ) were international relations of the Interwar period, interwar Kingdom of Yugoslavia and the Cold War Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. During its existence, the country was the founding member ...

* Yugoslavia–European Communities relations

* Mediterranean Games

The Mediterranean Games is a multi-sport event organised by the International Committee of Mediterranean Games (CIJM). It is held every four years among athletes from countries bordering the Mediterranean Sea in Africa, Asia and Europe. The fi ...

* Death and state funeral of Josip Broz Tito

Josip Broz Tito, President of Yugoslavia and leader of the League of Communists of Yugoslavia, died on 4 May 1980 following a prolonged illness. His state funeral was held four days later on 8 May, drawing a significant amount of statesmen ...

* Yugoslavia at the 1956 Winter Olympics

* Yugoslavia at the 1960 Summer Olympics

* Italy at the 1984 Winter Olympics

* Italy in the Eurovision Song Contest 1990

* Yugoslavia in the Eurovision Song Contest 1991

* Dalmatian Italians

Dalmatian Italians (; ) are the historical Italian national minority living in the region of Dalmatia, now part of Croatia and Montenegro.

Historically, Italian language-speaking Dalmatians accounted for 12.5% of population in 1865, 5.8% in 18 ...

Works cited

* *Notes

Further reading

* Latinović, Goran. "Yugoslav-Italian Economic Relations (1918‒1929): Main Aspects." ''Balcanica'' 46 (2015): 171-19online

* Pavlović, Vojislav G. "Le conflit franco-italien dans les Balkans 1915–1935. Le rôle de la Yougoslavie." ''Balcanica'' 36 (2005): 163-20

online in French

* Zametica, Jovan. "Sir Austen Chamberlain and the Italo-Yugoslav crisis over Albania February-May 1927." ''Balcanica'' 36 (2005): 203-235

online

{{DEFAULTSORT:Italy-Yugoslavia Relations

Yugoslavia

, common_name = Yugoslavia

, life_span = 1918–19921941–1945: World War II in Yugoslavia#Axis invasion and dismemberment of Yugoslavia, Axis occupation

, p1 = Kingdom of SerbiaSerbia

, flag_p ...

Yugoslavia

, common_name = Yugoslavia

, life_span = 1918–19921941–1945: World War II in Yugoslavia#Axis invasion and dismemberment of Yugoslavia, Axis occupation

, p1 = Kingdom of SerbiaSerbia

, flag_p ...

Yugoslavia

, common_name = Yugoslavia

, life_span = 1918–19921941–1945: World War II in Yugoslavia#Axis invasion and dismemberment of Yugoslavia, Axis occupation

, p1 = Kingdom of SerbiaSerbia

, flag_p ...

Yugoslavia

, common_name = Yugoslavia

, life_span = 1918–19921941–1945: World War II in Yugoslavia#Axis invasion and dismemberment of Yugoslavia, Axis occupation

, p1 = Kingdom of SerbiaSerbia

, flag_p ...

1918 establishments in Europe

Italy

Italy, officially the Italian Republic, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe, Western Europe. It consists of Italian Peninsula, a peninsula that extends into the Mediterranean Sea, with the Alps on its northern land b ...

Bosnia and Herzegovina–Italy relations

Italy–Kosovo relations

Italy–Montenegro relations

Italy–North Macedonia relations