The Israeli–Palestinian conflict is an ongoing military and political conflict about

land

Land, also known as dry land, ground, or earth, is the solid terrestrial surface of Earth not submerged by the ocean or another body of water. It makes up 29.2% of Earth's surface and includes all continents and islands. Earth's land sur ...

and

self-determination

Self-determination refers to a people's right to form its own political entity, and internal self-determination is the right to representative government with full suffrage.

Self-determination is a cardinal principle in modern international la ...

within the territory of the former

Mandatory Palestine

Mandatory Palestine was a British Empire, British geopolitical entity that existed between 1920 and 1948 in the Palestine (region), region of Palestine, and after 1922, under the terms of the League of Nations's Mandate for Palestine.

After ...

.

Key aspects of the conflict include the

Israeli occupation of the West Bank

The West Bank, including East Jerusalem, has been under military occupation by Israel since 7 June 1967, when Israeli forces captured the territory, then ruled by Jordan, during the Six-Day War. The status of the West Bank as a militarily oc ...

and

Gaza Strip

The Gaza Strip, also known simply as Gaza, is a small territory located on the eastern coast of the Mediterranean Sea; it is the smaller of the two Palestinian territories, the other being the West Bank, that make up the State of Palestine. I ...

, the

status of Jerusalem

The status of Jerusalem has been described as "one of the most intractable issues in the Israeli–Palestinian conflict" due to the long-running territorial dispute between Israel and the Palestinians, both of which claim it as their capital ...

,

Israeli settlement

Israeli settlements, also called Israeli colonies, are the civilian communities built by Israel throughout the Israeli-occupied territories. They are populated by Israeli citizens, almost exclusively of Israeli Jews, Jewish identity or ethni ...

s, borders, security, water rights, the

permit regime in the West Bank and

in the Gaza Strip,

Palestinian freedom of movement,

and the

Palestinian right of return

The Palestinian right of return is the political position or principle that Palestinian refugees, both Immigrant generations#First generation, first-generation refugees ( people still alive ) and their descendants ( people ), have a right to ...

.

The conflict has its origins in the rise of

Zionism

Zionism is an Ethnic nationalism, ethnocultural nationalist movement that emerged in History of Europe#From revolution to imperialism (1789–1914), Europe in the late 19th century that aimed to establish and maintain a national home for the ...

in the late 19th century in Europe, a movement which aimed to establish a Jewish state through the

colonization

475px, Map of the year each country achieved List of sovereign states by date of formation, independence.

Colonization (British English: colonisation) is a process of establishing occupation of or control over foreign territories or peoples f ...

of

Palestine

Palestine, officially the State of Palestine, is a country in West Asia. Recognized by International recognition of Palestine, 147 of the UN's 193 member states, it encompasses the Israeli-occupied West Bank, including East Jerusalem, and th ...

, synchronously with the

first arrival of

Jewish settlers to

Ottoman Palestine

The region of Palestine (region), Palestine is part of the wider region of the Levant, which represents the land bridge between Africa and Eurasia.Steiner & Killebrew, p9: "The general limits ..., as defined here, begin at the Plain of ' ...

in 1882. The Zionist movement garnered the support of an imperial power in the 1917

Balfour Declaration

The Balfour Declaration was a public statement issued by the British Government in 1917 during the First World War announcing its support for the establishment of a "national home for the Jewish people" in Palestine, then an Ottoman regio ...

issued by Britain, which promised to support the creation of a "

Jewish homeland" in Palestine. Following

British occupation of the formerly

Ottoman region during

World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, Mandatory Palestine was established as a

British mandate. Increasing Jewish immigration led to tensions between Jews and Arabs which grew into

intercommunal conflict. In 1936,

an Arab revolt erupted demanding independence and an end to British support for Zionism, which was suppressed by the British.

Eventually tensions led to the

United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is the Earth, global intergovernmental organization established by the signing of the Charter of the United Nations, UN Charter on 26 June 1945 with the stated purpose of maintaining international peace and internationa ...

adopting a

partition plan in 1947, triggering

a civil war.

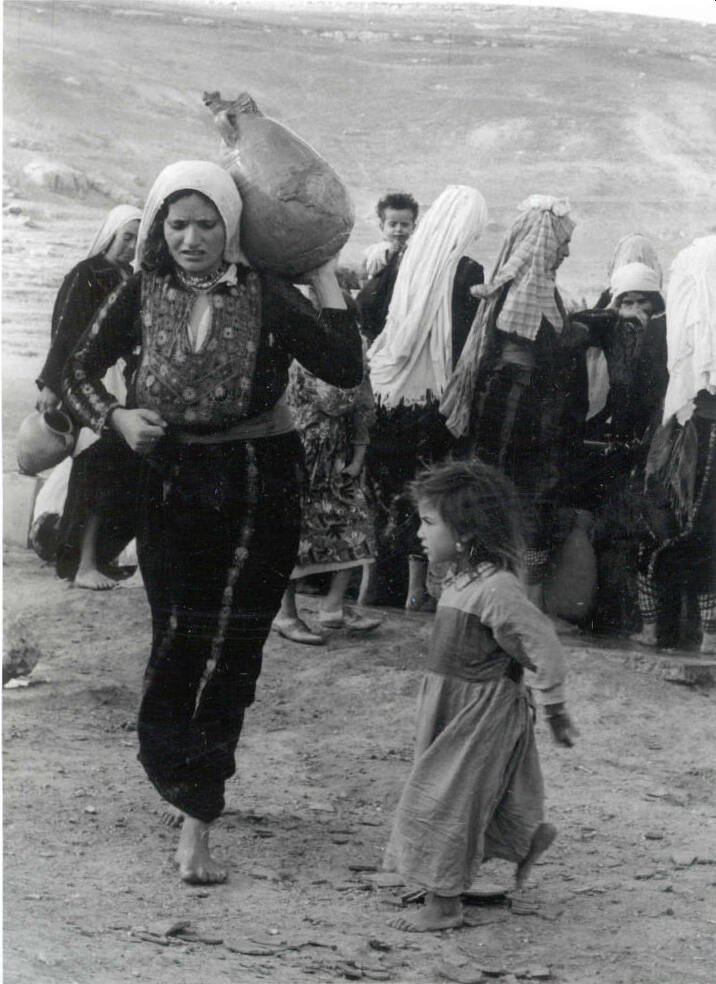

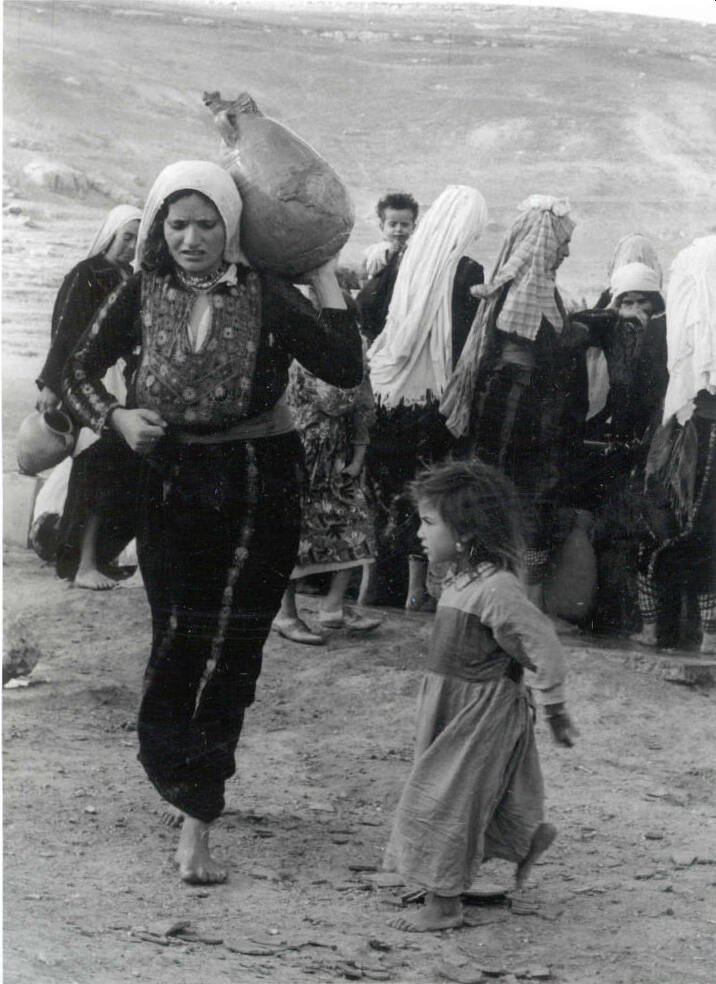

During the ensuing

1948 Palestine war

The 1948 Palestine war was fought in the territory of what had been, at the start of the war, British-ruled Mandatory Palestine. During the war, the British withdrew from Palestine, Zionist forces conquered territory and established the Stat ...

, more than half of the mandate's predominantly Palestinian Arab population

fled or were expelled by Israeli forces. By the

end

End, END, Ending, or ENDS may refer to:

End Mathematics

*End (category theory)

* End (topology)

* End (graph theory)

* End (group theory) (a subcase of the previous)

* End (endomorphism) Sports and games

*End (gridiron football)

*End, a division ...

of the war,

Israel

Israel, officially the State of Israel, is a country in West Asia. It Borders of Israel, shares borders with Lebanon to the north, Syria to the north-east, Jordan to the east, Egypt to the south-west, and the Mediterranean Sea to the west. Isr ...

was established on most of the former mandate's territory, and the

Gaza Strip

The Gaza Strip, also known simply as Gaza, is a small territory located on the eastern coast of the Mediterranean Sea; it is the smaller of the two Palestinian territories, the other being the West Bank, that make up the State of Palestine. I ...

and the

West Bank

The West Bank is located on the western bank of the Jordan River and is the larger of the two Palestinian territories (the other being the Gaza Strip) that make up the State of Palestine. A landlocked territory near the coast of the Mediter ...

were controlled by

Egypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

and

Jordan

Jordan, officially the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan, is a country in the Southern Levant region of West Asia. Jordan is bordered by Syria to the north, Iraq to the east, Saudi Arabia to the south, and Israel and the occupied Palestinian ter ...

respectively.

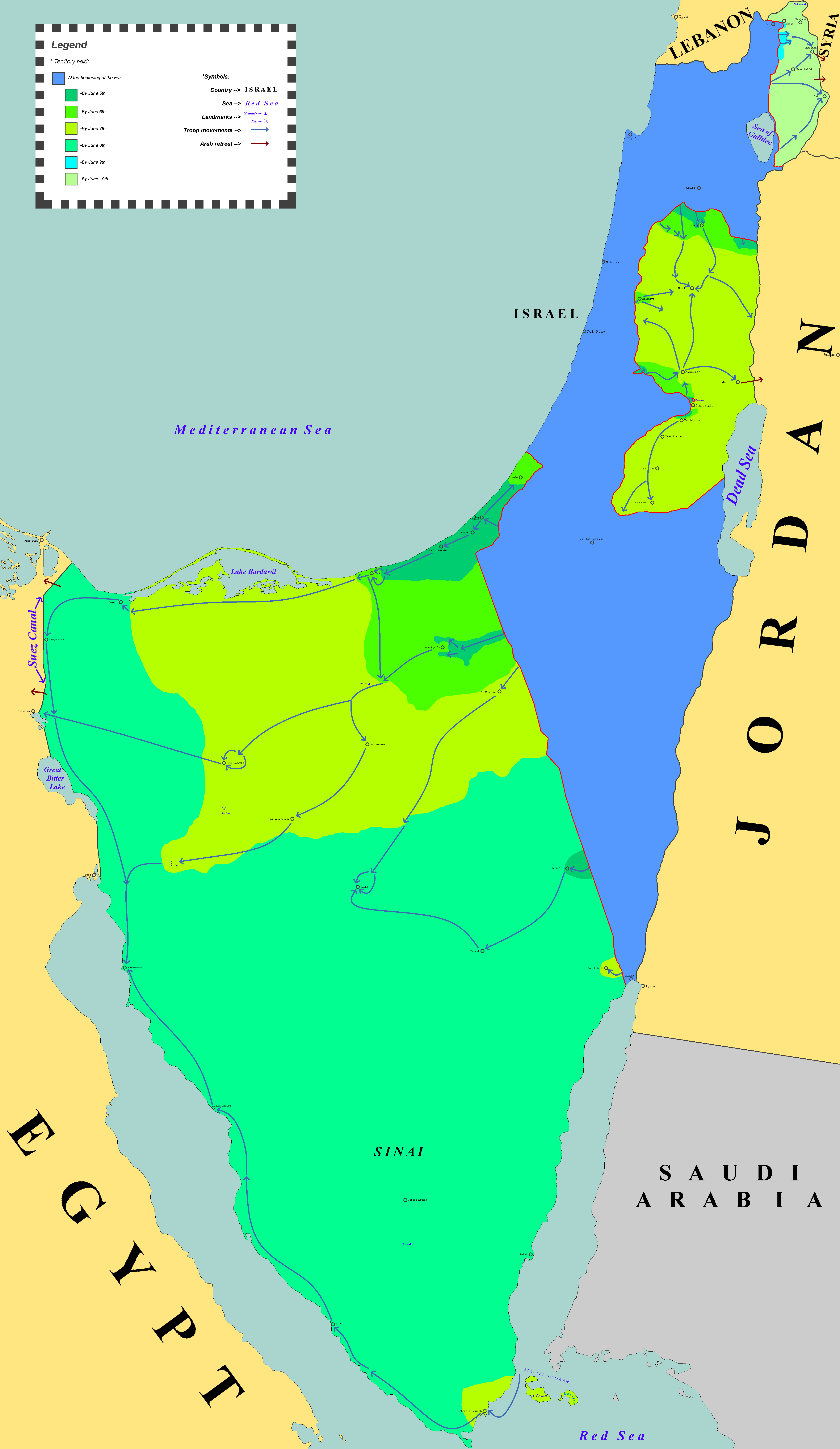

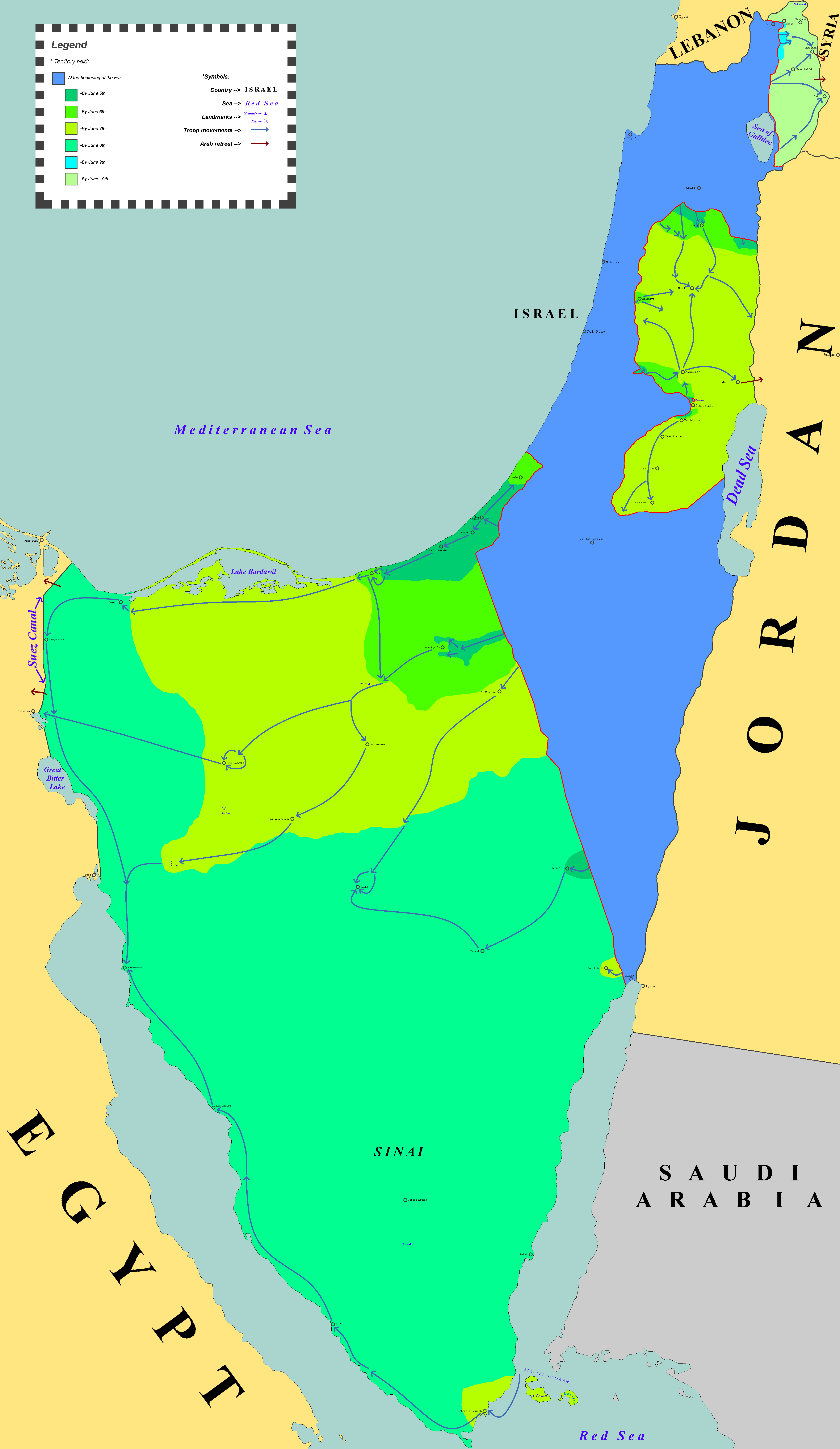

Since the 1967

Six-Day War

The Six-Day War, also known as the June War, 1967 Arab–Israeli War or Third Arab–Israeli War, was fought between Israel and a coalition of Arab world, Arab states, primarily United Arab Republic, Egypt, Syria, and Jordan from 5 to 10June ...

, Israel has been occupying the West Bank and the Gaza Strip, known collectively as the

Palestinian territories

The occupied Palestinian territories, also referred to as the Palestinian territories, consist of the West Bank (including East Jerusalem) and the Gaza Strip—two regions of the former Mandate for Palestine, British Mandate for Palestine ...

. Two Palestinian uprisings against Israel and its occupation erupted in 1987 and 2000, the

first and

second intifada

The Second Intifada (; ), also known as the Al-Aqsa Intifada, was a major uprising by Palestinians against Israel and its Israeli-occupied territories, occupation from 2000. Starting as a civilian uprising in Jerusalem and October 2000 prot ...

s respectively. Israel's occupation resulted in Israel constructing

illegal settlements there, creating a system of institutionalized discrimination against Palestinians under its occupation called

Israeli apartheid. This discrimination includes Israel's denial of Palestinian refugees from their right of return and

right to their lost properties. Israel has also

drawn international condemnation for

violating the human rights of the Palestinians.

The international community, with the exception of the United States and Israel, has been in consensus since the 1980s regarding a settlement of the conflict on the basis of a

two-state solution

The two-state solution is a proposed approach to resolving the Israeli–Palestinian conflict, by creating two states on the territory of the former Mandatory Palestine. It is often contrasted with the one-state solution, which is the esta ...

along the

1967 borders

The Green Line, or 1949 Armistice border, is the demarcation line set out in the 1949 Armistice Agreements between the armies of Israel and those of its neighbors (Egypt, Jordan, Lebanon, and Syria) after the 1948 Arab–Israeli War. It served ...

and a just resolution for Palestinian refugees. The United States and Israel have instead preferred bilateral negotiations rather than a resolution of the conflict on the basis of

international law

International law, also known as public international law and the law of nations, is the set of Rule of law, rules, norms, Customary law, legal customs and standards that State (polity), states and other actors feel an obligation to, and generall ...

. In recent years, public support for a two-state solution has decreased, with Israeli policy reflecting an interest in maintaining the occupation rather than seeking a permanent resolution to the conflict. In 2007, Israel tightened its

blockade of the Gaza Strip

The restrictions on movement and goods in Gaza imposed by Israel date to the early 1990s. After Hamas took over in 2007, Israel significantly intensified existing movement restrictions and imposed a complete blockade on the movement of good ...

and made official its policy of isolating it from the West Bank. Since then, Israel has framed its relationship with Gaza in terms of the

laws of war

The law of war is a component of international law that regulates the conditions for initiating war (''jus ad bellum'') and the conduct of hostilities (''jus in bello''). Laws of war define sovereignty and nationhood, states and territories, ...

rather than in terms of its status as an

occupying power

Military occupation, also called belligerent occupation or simply occupation, is temporary hostile control exerted by a ruling power's military apparatus over a sovereign territory that is outside of the legal boundaries of that ruling pow ...

. In

a July 2024 ruling, the

International Court of Justice

The International Court of Justice (ICJ; , CIJ), or colloquially the World Court, is the only international court that Adjudication, adjudicates general disputes between nations, and gives advisory opinions on International law, internation ...

(ICJ) rebuffed Israel's stance, determining that the Palestinian territories constitute one political unit and that Israel continues to illegally occupy the West Bank and Gaza Strip. The ICJ also determined that Israeli policies violate the

. Since 2006, Hamas and Israel have fought

several wars. Attacks by

Hamas-led armed groups in October 2023 in Israel were followed by

another war. Israel's actions in Gaza since the start of the war have been described by international law experts, genocide scholars and human rights organizations as

genocidal

Genocide is violence that targets individuals because of their membership of a group and aims at the destruction of a people. Raphael Lemkin, who first coined the term, defined genocide as "the destruction of a nation or of an ethnic group" b ...

.

History

The Israeli–Palestinian conflict began in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, with the development of political Zionism and the arrival of Zionist settlers to Palestine.

During the early 20th century, Arab nationalism also grew within the

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

. To gain support from the Arab nationalists in the war against the Ottoman Empire, Great Britain promised support for the formation of an independent Arab state in Palestine in the

McMahon–Hussein correspondence

The McMahon–Hussein correspondence is a series of letters that were exchanged during World War I, in which the government of the United Kingdom agreed to recognize Arab independence in a large region after the war Quid pro quo, in exchange ...

. The

British Empire

The British Empire comprised the dominions, Crown colony, colonies, protectorates, League of Nations mandate, mandates, and other Dependent territory, territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It bega ...

supplied a large amount of weapons to the

Arab revolt

The Arab Revolt ( ), also known as the Great Arab Revolt ( ), was an armed uprising by the Hashemite-led Arabs of the Hejaz against the Ottoman Empire amidst the Middle Eastern theatre of World War I.

On the basis of the McMahon–Hussein Co ...

1916-1918. With support from the

Arab revolt

The Arab Revolt ( ), also known as the Great Arab Revolt ( ), was an armed uprising by the Hashemite-led Arabs of the Hejaz against the Ottoman Empire amidst the Middle Eastern theatre of World War I.

On the basis of the McMahon–Hussein Co ...

the British Empire defeated the Ottoman's forces and took control of Palestine, Jordan and Syria. It later transpired that the British and French governments had secretly made the

Sykes-Picot Agreement in 1916 not to allow the formation of an independent Arab state. In July 1920, the short-lived

Arab Kingdom of Syria

The Syrian Arab Kingdom (, ') was a self-proclaimed, unrecognized monarchy existing briefly in the territory of Bilad al-Sham, historical Syria. It was announced on 5 October 1918 as a fully independent Arab constitutional government with the perm ...

, with Emir

Faisal (one of the leaders of the Arab Revolt) as king and tolerated by Britain, was crushed by French armed forces, equipped with modern artillery.

While

Jewish colonization began during this period, it was not until the arrival of more

ideologically Zionist immigrants in the decade preceding the First World War that the landscape of Ottoman Palestine would start to significantly change.

Land purchases, the eviction of tenant Arab peasants and armed confrontation with Jewish para-military units would all contribute to the Palestinian population's growing fear of territorial displacement and dispossession.

From early on, the leadership of the Zionist movement had the idea of "transferring" (a euphemism for

ethnic cleansing

Ethnic cleansing is the systematic forced removal of ethnic, racial, or religious groups from a given area, with the intent of making the society ethnically homogeneous. Along with direct removal such as deportation or population transfer, it ...

) the Arab Palestinian population out of the land for the purpose of establishing a Jewish demographic majority. According to the Israeli historian

Benny Morris

Benny Morris (; born 8 December 1948) is an Israeli historian. He was a professor of history in the Middle East Studies department of Ben-Gurion University of the Negev in the city of Beersheba, Israel. Morris was initially associated with the ...

the idea of transfer was "inevitable and inbuilt into Zionism". The Arab population felt this threat as early as the 1880s with the arrival of the first aliyah.

Chaim Weizmann

Chaim Azriel Weizmann ( ; 27 November 1874 – 9 November 1952) was a Russian-born Israeli statesman, biochemist, and Zionist leader who served as president of the World Zionist Organization, Zionist Organization and later as the first pre ...

's efforts to build British support for the Zionist movement would eventually secure the

Balfour Declaration

The Balfour Declaration was a public statement issued by the British Government in 1917 during the First World War announcing its support for the establishment of a "national home for the Jewish people" in Palestine, then an Ottoman regio ...

, a public statement issued by the British government in 1917 during the First World War announcing support for the establishment of a "national home for the Jewish people" in Palestine.

1920s

With the creation of the

British Mandate in Palestine after the end of the first world war, large-scale Jewish immigration began accompanied by the development of a separate Jewish-controlled sector of the economy supported by foreign capital. The more ardent Zionist ideologues of the

Second Aliyah

The Second Aliyah () was an aliyah (Jewish immigration to the Land of Israel) that took place between 1904 and 1914, during which approximately 35,000 Jews, mostly from Russia, with some from Yemen, immigrated into Ottoman Palestine.

The Sec ...

would become the leaders of the

Yishuv

The Yishuv (), HaYishuv Ha'ivri (), or HaYishuv HaYehudi Be'Eretz Yisra'el () was the community of Jews residing in Palestine prior to the establishment of the State of Israel in 1948. The term came into use in the 1880s, when there were about 2 ...

starting in the 1920s and believed in the separation of Jewish and Arab societies.

Amin al-Husseini

Mohammed Amin al-Husseini (; 4 July 1974) was a Palestinian Arab nationalist and Muslim leader in Mandatory Palestine. was the scion of the family of Jerusalemite Arab nobles, who trace their origins to the Islamic prophet Muhammad.

Hussein ...

, appointed as

Grand Mufti of Jerusalem

The Grand Mufti of Jerusalem is the Sunni Muslim cleric in charge of Jerusalem's Islamic holy places, including Al-Aqsa. The position was created by the British military government led by Ronald Storrs in 1918.See Islamic Leadership in Jerusa ...

by the British

High Commissioner Herbert Samuel, immediately marked

Jewish national movement and

Jewish immigration to Palestine as the sole enemy to his cause,

He usseiniincited and headed anti-Jewish riots in April 1920. ... He promoted the Muslim character of Jerusalem and ... injected a religious character into the struggle against Zionism

Zionism is an Ethnic nationalism, ethnocultural nationalist movement that emerged in History of Europe#From revolution to imperialism (1789–1914), Europe in the late 19th century that aimed to establish and maintain a national home for the ...

. This was the backdrop to his agitation concerning Jewish rights at the Western (Wailing) Wall that led to the bloody riots of August 1929... was the chief organizer of the riots of 1936 and the rebellion from 1937, as well as of the mounting internal terror against Arab opponents.

initiating large-scale riots against the Jews as early as 1920

in Jerusalem and in 1921

in Jaffa. Among the results of the violence was the establishment of the Jewish paramilitary force

Haganah

Haganah ( , ) was the main Zionist political violence, Zionist paramilitary organization that operated for the Yishuv in the Mandatory Palestine, British Mandate for Palestine. It was founded in 1920 to defend the Yishuv's presence in the reg ...

. In 1929, a series of violent

riots

A riot or mob violence is a form of civil disorder commonly characterized by a group lashing out in a violent public disturbance against authority, property, or people.

Riots typically involve destruction of property, public or private. The p ...

resulted in the deaths of 133 Jews and 116 Arabs, with significant Jewish casualties in

Hebron

Hebron (; , or ; , ) is a Palestinian city in the southern West Bank, south of Jerusalem. Hebron is capital of the Hebron Governorate, the largest Governorates of Palestine, governorate in the West Bank. With a population of 201,063 in ...

and

Safed

Safed (), also known as Tzfat (), is a city in the Northern District (Israel), Northern District of Israel. Located at an elevation of up to , Safed is the highest city in the Galilee and in Israel.

Safed has been identified with (), a fortif ...

, and the evacuation of Jews from Hebron and Gaza.

1936–1939 Arab revolt

In the early 1930s, the Arab national struggle in Palestine had drawn many Arab nationalist militants from across the Middle East, such as

Sheikh Izz ad-Din al-Qassam from Syria, who established the Black Hand militant group and had prepared the grounds for the

1936–1939 Arab revolt in Palestine

A popular uprising by Palestinian Arabs in Mandatory Palestine against the British administration, later known as the Great Revolt, the Great Palestinian Revolt, or the Palestinian Revolution, lasted from 1936 until 1939. The movement sought i ...

. Following the death of al-Qassam at the hands of the British in late 1935, tensions erupted in 1936 into the Arab general strike and general boycott. The strike soon deteriorated into violence, and the Arab revolt was bloodily repressed by the British assisted by the British armed forces of the

Jewish Settlement Police, the

Jewish Supernumerary Police

The Jewish Supernumerary Police (Hebrew: ''Shotrim Musafim''), sometimes referred to as Jewish Auxiliary Police, were a branch of the Guards ('' Notrim'') set up by the British in the British Mandate of Palestine in June 1936.

The British autho ...

, and

Special Night Squads.

The suppression of the revolt would leave at least 10% of the adult male population killed, wounded, imprisoned or exiled. Between the expulsion of much of the Arab leadership and the weakening of the economy, the Palestinians would struggle to confront the growing Zionist movement.

The cost and risks associated with the revolt and the ongoing

inter-communal conflict led to a shift in British policies in the region and the appointment of the

Peel Commission which recommended creation of a small Jewish country, which the two main Zionist leaders,

Chaim Weizmann

Chaim Azriel Weizmann ( ; 27 November 1874 – 9 November 1952) was a Russian-born Israeli statesman, biochemist, and Zionist leader who served as president of the World Zionist Organization, Zionist Organization and later as the first pre ...

and

David Ben-Gurion

David Ben-Gurion ( ; ; born David Grün; 16 October 1886 – 1 December 1973) was the primary List of national founders, national founder and first Prime Minister of Israel, prime minister of the State of Israel. As head of the Jewish Agency ...

, accepted on the basis that it would allow for later expansion. The subsequent

White Paper of 1939

The White Paper of 1939Occasionally also known as the MacDonald White Paper (e.g. Caplan, 2015, p.117) after Malcolm MacDonald, the British Colonial Secretary, who presided over its creation. was a policy paper issued by the British governmen ...

, which rejected a Jewish state and sought to limit Jewish immigration to the region, was the breaking point in relations between British authorities and the Zionist movement.

1940–1947

The renewed violence, which continued sporadically until the beginning of World War II, ended with around 5,000 casualties on the Arab side and 700 combined on the British and Jewish side total. With the eruption of

World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, the situation in Mandatory Palestine calmed down. It allowed a shift towards a more moderate stance among Palestinian Arabs under the leadership of the Nashashibi clan and even the establishment of the Jewish–Arab

Palestine Regiment under British command, fighting Germans in North Africa. The more radical exiled faction of al-Husseini, however, tended to cooperate with Nazi Germany, and participated in the establishment of a pro-Nazi propaganda machine throughout the Arab world. The

defeat of Arab nationalists in Iraq and subsequent relocation of al-Husseini to Nazi-occupied Europe tied his hands regarding field operations in Palestine, though he regularly demanded that the Italians and the Germans

bomb Tel Aviv.

The

Jewish Agency for Palestine

The Jewish Agency for Israel (), formerly known as the Jewish Agency for Palestine, is the largest Jews, Jewish non-profit organization in the world. It was established in 1929 as the operative branch of the World Zionist Organization (WZO).

...

and

Palestinian National Defense Party called on Palestine's Jewish and Arab youth to volunteer for the British Army. 30,000 Palestinian Jews and 12,000 Palestinian Arabs enlisted in the British armed forces during the war, while a

Jewish Brigade

The Jewish Infantry Brigade Group, more commonly known as the Jewish Brigade Group or Jewish Brigade, was a military formation of the British Army in the World War II, Second World War. It was formed in late 1944 and was recruited among Yishuv, Y ...

was created in 1944.

By the end of World War II, a crisis over the fate of

Holocaust survivors

Holocaust survivors are people who survived the Holocaust, defined as the persecution and attempted annihilation of the Jews by Nazi Germany and its collaborators before and during World War II in Europe and North Africa. There is no universall ...

from Europe led to renewed tensions between the

Yishuv

The Yishuv (), HaYishuv Ha'ivri (), or HaYishuv HaYehudi Be'Eretz Yisra'el () was the community of Jews residing in Palestine prior to the establishment of the State of Israel in 1948. The term came into use in the 1880s, when there were about 2 ...

and Mandate authorities. By 1944, Jewish groups began to conduct military-style operations against the British, with the aim of persuading Great Britain to accept the formation of a Jewish state. This culminated in the

Jewish insurgency in Mandatory Palestine

The Jewish insurgency in Mandatory Palestine, known in the United Kingdom as the Palestine Emergency, was a paramilitary campaign carried out by Zionist militias and underground groups—including Haganah, Lehi (militant group), Lehi, and Irgun ...

. This sustained Zionist paramilitary campaign of resistance against British authorities, along with the increased illegal immigration of Jewish refugees and 1947 United Nations partition, led to eventual withdrawal of the British from Palestine.

1947 United Nations partition plan

On 29 November 1947, the

General Assembly of the United Nations

The United Nations General Assembly (UNGA or GA; , AGNU or AG) is one of the six principal organs of the United Nations (UN), serving as its main deliberative, policymaking, and representative organ. Currently in its 79th session, its powers, ...

adopted

Resolution 181(II) recommending the adoption and implementation of a plan to partition Palestine into an Arab state, a Jewish state and the City of Jerusalem.

[Baum, Noa]

"Historical Time Line for Israel/Palestine."

UMass Amherst. 5 April 2005. 14 March 2013. Palestinian Arabs were opposed to the partition. Zionists accepted the partition but planned to expand Israel's borders beyond what was allocated to it by the UN. On the next day,

Palestine was swept by violence, igniting the first phase of the

Palestine War. For four months, under continuous Arab provocation and attack, the Yishuv was usually on the defensive while occasionally retaliating. The

Arab League

The Arab League (, ' ), officially the League of Arab States (, '), is a regional organization in the Arab world. The Arab League was formed in Cairo on 22 March 1945, initially with seven members: Kingdom of Egypt, Egypt, Kingdom of Iraq, ...

supported the Arab struggle by forming the volunteer-based

Arab Liberation Army, supporting the Palestinian Arab

Army of the Holy War

The Army of the Holy War or Holy War Army (; ''Jaysh al-Jihād al-Muqaddas'') was a Palestinian Arab irregular force in the 1947–1948 civil war in Mandatory Palestine led by Abd al-Qadir al-Husayni and Hasan Salama. The force has been de ...

, under the leadership of

Abd al-Qadir al-Husayni and

Hasan Salama. On the Jewish side, the civil war was managed by the major underground militias – the

Haganah

Haganah ( , ) was the main Zionist political violence, Zionist paramilitary organization that operated for the Yishuv in the Mandatory Palestine, British Mandate for Palestine. It was founded in 1920 to defend the Yishuv's presence in the reg ...

,

Irgun

The Irgun (), officially the National Military Organization in the Land of Israel, often abbreviated as Etzel or IZL (), was a Zionist paramilitary organization that operated in Mandatory Palestine between 1931 and 1948. It was an offshoot of th ...

and

Lehi – strengthened by numerous Jewish veterans of World War II and foreign volunteers. By spring 1948, it was already clear that the Arab forces were nearing a total collapse, while Yishuv forces gained more and more territory, creating a large scale

refugee problem of Palestinian Arabs.

1948 Arab–Israeli War

Following the

Declaration of the Establishment of the State of Israel

The Israeli Declaration of Independence, formally the Declaration of the Establishment of the State of Israel (), was proclaimed on 14 May 1948 (5 Iyar 5708), at the end of the civil war phase and beginning of the international phase of the ...

on 14 May 1948, the Arab League decided to intervene on behalf of Palestinian Arabs, marching their forces into former British Palestine, beginning the main phase of the

1948 Arab–Israeli War

The 1948 Arab–Israeli War, also known as the First Arab–Israeli War, followed the 1947–1948 civil war in Mandatory Palestine, civil war in Mandatory Palestine as the second and final stage of the 1948 Palestine war. The civil war becam ...

.

The overall fighting, leading to around 15,000 casualties, resulted in cease-fire and armistice agreements of 1949, with Israel holding much of the former Mandate territory, Jordan occupying and later annexing the

West Bank

The West Bank is located on the western bank of the Jordan River and is the larger of the two Palestinian territories (the other being the Gaza Strip) that make up the State of Palestine. A landlocked territory near the coast of the Mediter ...

and Egypt taking over the Gaza Strip, where the

All-Palestine Government

The All-Palestine Government (, ') was established on 22 September 1948, during the 1948 Arab–Israeli War, to govern the Egyptian-controlled territory in Gaza, which Egypt had on the same day declared as the All-Palestine Protectorate. It w ...

was declared by the Arab League on 22 September 1948.

The

1947–1948 civil war in Mandatory Palestine and 1948 Arab-Israeli War resulted in the

ethnic cleansing of 750,000 Palestinian Arabs.

In 1950, Israel passed the

Law of Return

The Law of Return (, ''ḥok ha-shvūt'') is an Israeli law, passed on 5 July 1950, which gives Jews, people with one or more Jewish grandparent, and their spouses the right to Aliyah, relocate to Israel and acquire Israeli nationality law, Isra ...

, which allowed Jews and their spouses to become citizens with voting rights, even if they had never lived there before.

1956 Suez Crisis

Through the 1950s, Jordan and Egypt supported the

Palestinian Fedayeen

Palestinian fedayeen () are militants or guerrillas of a nationalist orientation from among the Palestinian people. Most Palestinians consider the fedayeen to be Resistance movement, freedom fighters, while most Israelis consider them to be Pa ...

militants' cross-border attacks into Israel, while Israel carried out

its own reprisal operations in the host countries. The 1956

Suez Crisis

The Suez Crisis, also known as the Second Arab–Israeli War, the Tripartite Aggression in the Arab world and the Sinai War in Israel, was a British–French–Israeli invasion of Egypt in 1956. Israel invaded on 29 October, having done so w ...

resulted in a short-term Israeli occupation of the Gaza Strip and exile of the

All-Palestine Government

The All-Palestine Government (, ') was established on 22 September 1948, during the 1948 Arab–Israeli War, to govern the Egyptian-controlled territory in Gaza, which Egypt had on the same day declared as the All-Palestine Protectorate. It w ...

, which was later restored with Israeli withdrawal. The All-Palestine Government was completely abandoned by Egypt in 1959 and was officially merged into the

United Arab Republic

The United Arab Republic (UAR; ) was a sovereign state in the Middle East from 1958 to 1971. It was initially a short-lived political union between Republic of Egypt (1953–1958), Egypt (including Occupation of the Gaza Strip by the United Ara ...

, to the detriment of the Palestinian national movement.

Gaza Strip

The Gaza Strip, also known simply as Gaza, is a small territory located on the eastern coast of the Mediterranean Sea; it is the smaller of the two Palestinian territories, the other being the West Bank, that make up the State of Palestine. I ...

then was put under the authority of the Egyptian military administrator, making it a de facto military occupation. In 1964, however, a new organization, the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), was established by Yasser Arafat.

It immediately won the support of most Arab League governments and was granted a seat in the

Arab League

The Arab League (, ' ), officially the League of Arab States (, '), is a regional organization in the Arab world. The Arab League was formed in Cairo on 22 March 1945, initially with seven members: Kingdom of Egypt, Egypt, Kingdom of Iraq, ...

.

1967 Six-Day War

In the

1967 Arab-Israel War, Israel occupied the Palestinian West Bank, East Jerusalem, Gaza Strip, Egyptian Sinai, Syrian Golan Heights, and two islands in the

Gulf of Aqaba

The Gulf of Aqaba () or Gulf of Eilat () is a large gulf at the northern tip of the Red Sea, east of the Sinai Peninsula and west of the Arabian Peninsula. Its coastline is divided among four countries: Egypt, Israel, Jordan, and Saudi Arabia.

...

.

The war exerted a significant effect upon Palestinian nationalism, as the PLO was unable to establish any control on the ground and ultimately established its headquarters in Jordan, from where it supported the Jordanian army during the

War of Attrition

The War of Attrition (; ) involved fighting between Israel and Egypt, Jordan, the Palestine Liberation Organisation (PLO) and their allies from 1967 to 1970.

Following the 1967 Six-Day War, no serious diplomatic efforts were made to resolve t ...

. However, the Palestinian base in Jordan collapsed with the

Jordanian–Palestinian civil war in 1970, after which the PLO was forced to relocate to South Lebanon.

In the mid-1970s, the international community converged on a framework to resolve the conflict through the establishment of an independent Palestinian state in the West Bank and Gaza. This "

land for peace

Land for peace is a legalistic interpretation of UN Security Council Resolution 242 which has been used as the basis of subsequent Arab–Israeli peace making. The name ''Land for Peace'' is derived from the wording of the resolution's first ope ...

" proposal was endorsed by the

ICJ

The International Court of Justice (ICJ; , CIJ), or colloquially the World Court, is the only international court that Adjudication, adjudicates general disputes between nations, and gives advisory opinions on International law, internation ...

and

UN.

1973 Yom Kippur War

On 6 October 1973, a coalition of Arab forces consisting of mainly Egypt and Syria launched a surprise attack against Israel on the Jewish holy day of Yom Kippur. Despite this, the war concluded with an Israeli victory, with both sides suffering tremendous casualties.

Following the end of the war, the UN Security Council passed Resolution 338 confirming the land-for-peace principle established in Resolution 242, initiating the Middle East peace process. The Arab defeat would play an important role in the PLO's willingness to pursue a negotiated settlement to the conflict, while many Israelis began to believe that the area under Israeli occupation could not be held indefinitely by force.

The Camp David Accords, agreed upon by Israel and Egypt in 1978, primarily aimed to establish a peace treaty between the two countries. The accords also proposed the creation of a "Self-Governing Authority" for the Arab population in the West Bank and Gaza Strip, excluding Jerusalem, under Israeli control. A peace treaty based on these accords was signed in 1979, leading to Israel's withdrawal from the occupied Egyptian Sinai Peninsula by 1982.

1982 Lebanon War

During the

Lebanese Civil War

The Lebanese Civil War ( ) was a multifaceted armed conflict that took place from 1975 to 1990. It resulted in an estimated 150,000 fatalities and led to the exodus of almost one million people from Lebanon.

The religious diversity of the ...

, Palestinian militants continued to launch attacks against Israel while also battling opponents within Lebanon. In 1978, the

Coastal Road massacre led to the Israeli full-scale invasion known as

Operation Litani

The 1978 South Lebanon conflict, also known as the First Israeli invasion of Lebanon and codenamed Operation Litani by Israel, began when Israel invaded southern Lebanon up to the Litani River in March 1978. It was in response to the Coas ...

. This operation sought to dislodge the from Lebanon while expanding the area under the control of the Israeli allied Christian militias in southern Lebanon. The operation succeeded in leaving a large portion of the south in control of the Israeli proxy which would eventually form the

South Lebanon Army

The South Lebanon Army or South Lebanese Army (SLA; , ), also known as the Lahad Army () or as the De Facto Forces (DFF), was a Christianity in Lebanon, Christian-dominated militia in Lebanon. It was founded by Lebanese military officer Saad H ...

. Under United States pressure, Israeli forces would eventually withdraw from Lebanon.

In 1982, Israel, having secured its southern border with Egypt, sought to resolve the Palestinian issue by attempting to dismantle the military and political power of the PLO in Lebanon. The goal was to establish a friendly regime in Lebanon and continue its policy of settlement and annexation in occupied Palestine.

[: "The real driving force behind Israel's invasion of Lebanon, however, was Ariel Sharon, whose aims were much more ambitious and far-reaching. From his first day at the Defense Ministry, Sharon started planning the invasion of Lebanon. He developed what came to be known as the "big plan" for using Israel's military power to establish political hegemony in the Middle East. The first aim of Sharon's plan was to destroy the PLO's military infrastructure in Lebanon and to undermine it as a political organization. The second aim was to establish a new political order in Lebanon by helping Israel's Maronite friends, headed by Bashir Gemayel, to form a government that would proceed to sign a peace treaty with Israel. For this to be possible, it was necessary, third, to expel the Syrian forces from Lebanon or at least to weaken seriously the Syrian presence there. In Sharon's big plan, the war in Lebanon was intended to transform the situation not only in Lebanon but in the whole Middle East. The destruction of the PLO would break the backbone of Palestinian nationalism and facilitate the absorption of the West Bank into Greater Israel. The resulting influx of Palestinians from Lebanon and the West Bank into Jordan would eventually sweep away the Hashemite monarchy and transform the East Bank into a Palestinian state. Sharon reasoned that Jordan's conversion into a Palestinian state would end international pressures on Israel to withdraw from the West Bank. Begin was not privy to all aspects of Sharon's ambitious geopolitical scenario, but the two men were united by their desire to act against the PLO in Lebanon."] The PLO had observed the latest ceasefire with Israel and shown a preference for negotiations over military operations. As a result, Israel sought to remove the PLO as a potential negotiating partner. Most Palestinian militants were defeated within several weeks, Beirut was captured, and the PLO headquarters were evacuated to Tunisia in June by Yasser Arafat's decision.

First Intifada (1987–1993)

The first Palestinian uprising began in 1987 as a response to Israel's military occupation, escalating attacks on Palestinians, and policies of settlement building and collective punishment. The uprising largely consisted of nonviolent acts of civil disobedience and protest, and was largely led by grassroots popular, youth, and women's committees.

By the early 1990s, the conflict, termed the

First Intifada

The First Intifada (), also known as the First Palestinian Intifada, was a sustained series of Nonviolent resistance, non-violent protests, acts of civil disobedience, Riot, riots, and Terrorism, terrorist attacks carried out by Palestinians ...

, was the focus of international settlement efforts, in part motivated by the success of the Egyptian–Israeli peace treaty of 1982. Eventually the

Israeli–Palestinian peace process

Intermittent discussions are held by various parties and proposals put forward in an attempt to resolve the Israeli–Palestinian conflict through a peace process. Since the 1970s, there has been a parallel effort made to find terms upon which ...

led to the

Oslo Accords

The Oslo Accords are a pair of interim agreements between Israel and the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO): the Oslo I Accord, signed in Washington, D.C., in 1993; and the Oslo II Accord, signed in Taba, Egypt, in 1995. They marked the st ...

of 1993, allowing the PLO to relocate from Tunisia and take ground in the

West Bank

The West Bank is located on the western bank of the Jordan River and is the larger of the two Palestinian territories (the other being the Gaza Strip) that make up the State of Palestine. A landlocked territory near the coast of the Mediter ...

and

Gaza Strip

The Gaza Strip, also known simply as Gaza, is a small territory located on the eastern coast of the Mediterranean Sea; it is the smaller of the two Palestinian territories, the other being the West Bank, that make up the State of Palestine. I ...

, establishing the

Palestinian National Authority

The Palestinian Authority (PA), officially known as the Palestinian National Authority (PNA), is the Fatah-controlled government body that exercises partial civil control over the Palestinian enclaves in the Israeli-occupied West Bank as a c ...

. The peace process also had significant opposition among elements of Palestinian society, such as Hamas and Palestinian Islamic Jihad, who immediately initiated a campaign of attacks targeting Israelis. Following hundreds of casualties and a wave of anti-government propaganda, Israeli Prime Minister

Rabin was assassinated by an

Israeli far-right extremist who objected to the peace initiative. This struck a serious blow to the peace process, which in 1996 led to the newly elected government of Israel backing off from the process, to some degree.

Second Intifada (2000–2005)

Following several years of unsuccessful negotiations, the conflict re-erupted as the

Second Intifada

The Second Intifada (; ), also known as the Al-Aqsa Intifada, was a major uprising by Palestinians against Israel and its Israeli-occupied territories, occupation from 2000. Starting as a civilian uprising in Jerusalem and October 2000 prot ...

in September 2000.

The violence, escalating into an open conflict between the

Palestinian National Security Forces

The Palestinian National Security Forces (NSF; ) are the paramilitary security forces of the Palestinian National Authority. The name may either refer to all National Security Forces, including some special services but not including the Inter ...

and the

Israel Defense Forces

The Israel Defense Forces (IDF; , ), alternatively referred to by the Hebrew-language acronym (), is the national military of the State of Israel. It consists of three service branches: the Israeli Ground Forces, the Israeli Air Force, and ...

, lasted until 2004/2005 and led to thousands of fatalities. In 2005, Israeli Prime Minister Sharon ordered the

removal of Israeli settlers and soldiers from Gaza. Israel and its Supreme Court formally declared an end to occupation, saying it "had no effective control over what occurred" in Gaza.

However, the

United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is the Earth, global intergovernmental organization established by the signing of the Charter of the United Nations, UN Charter on 26 June 1945 with the stated purpose of maintaining international peace and internationa ...

,

Human Rights Watch

Human Rights Watch (HRW) is an international non-governmental organization that conducts research and advocacy on human rights. Headquartered in New York City, the group investigates and reports on issues including War crime, war crimes, crim ...

and many other international bodies and

NGOs

A non-governmental organization (NGO) is an independent, typically nonprofit organization that operates outside government control, though it may get a significant percentage of its funding from government or corporate sources. NGOs often focus ...

continue to consider Israel to be the occupying power of the Gaza Strip as Israel controls Gaza Strip's airspace, territorial waters and controls the movement of people or goods in or out of Gaza by air or sea.

Fatah–Hamas split (2006–2007)

In 2006, Hamas won a plurality of 44% in the

Palestinian parliamentary election. Israel responded it would begin

economic sanctions

Economic sanctions or embargoes are Commerce, commercial and Finance, financial penalties applied by states or institutions against states, groups, or individuals. Economic sanctions are a form of Coercion (international relations), coercion tha ...

unless Hamas agreed to accept prior Israeli–Palestinian agreements, forswear violence, and recognize Israel's right to exist, all of which Hamas rejected. After internal Palestinian political struggle between Fatah and Hamas erupted into the

2007 Battle of Gaza, Hamas took full control of the area. In 2007, Israel imposed a naval

blockade on the Gaza Strip, and cooperation with Egypt allowed a ground blockade of the Egyptian border.

The tensions between Israel and Hamas escalated until late 2008, when Israel launched operation

Cast Lead upon Gaza, resulting in thousands of civilian casualties and billions of dollars in damage. By February 2009, a ceasefire was signed with international mediation between the parties, though the occupation and small and sporadic eruptions of violence continued.

In 2011, a Palestinian Authority attempt to gain UN membership as a fully sovereign state failed. In Hamas-controlled Gaza, sporadic rocket attacks on Israel and Israeli air raids continued to occur. In November 2012, Palestinian representation in the UN was upgraded to a non-member observer state, and its mission title was changed from "Palestine (represented by PLO)" to "

State of Palestine

Palestine, officially the State of Palestine, is a country in West Asia. Recognized by International recognition of Palestine, 147 of the UN's 193 member states, it encompasses the Israeli-occupied West Bank, including East Jerusalem, and th ...

". In 2014,

another war broke out between Israel and Gaza, resulting in over 70 Israeli and over 2,000 Palestinian casualties.

2023–present Gaza war

After the 2014 war and

2021 crisis, Hamas began planning an attack on Israel. In 2022, Netanyahu returned to power while headlining a hardline

far-right

Far-right politics, often termed right-wing extremism, encompasses a range of ideologies that are marked by ultraconservatism, authoritarianism, ultranationalism, and nativism. This political spectrum situates itself on the far end of the ...

government

A government is the system or group of people governing an organized community, generally a State (polity), state.

In the case of its broad associative definition, government normally consists of legislature, executive (government), execu ...

, which led to greater political strife in Israel and clashes in the Palestinian territories. This culminated in

a surprise attack launched by Hamas-led militant groups on southern Israel from the Gaza Strip on 7 October 2023, in which more than 1,200 Israeli civilians and military personnel were killed, and around

250 were taken hostage into Gaza. The

Israeli military retaliated by

declaring war on Hamas and conducting an extensive

aerial bombardment campaign on Gaza, followed by a

large-scale ground invasion with the stated goal of destroying Hamas, freeing hostages, and controlling security in Gaza afterwards. Israel killed tens of thousands of Palestinians, including civilians and combatants and

displaced almost two million people. South Africa

accused Israel of

genocide

Genocide is violence that targets individuals because of their membership of a group and aims at the destruction of a people. Raphael Lemkin, who first coined the term, defined genocide as "the destruction of a nation or of an ethnic group" by ...

at the

International Court of Justice

The International Court of Justice (ICJ; , CIJ), or colloquially the World Court, is the only international court that Adjudication, adjudicates general disputes between nations, and gives advisory opinions on International law, internation ...

and called for an immediate ceasefire.

[ALT Link]

/ref> The court issued an order requiring Israel to take all measures to prevent any acts contrary to the 1948 Genocide Convention,West Bank

The West Bank is located on the western bank of the Jordan River and is the larger of the two Palestinian territories (the other being the Gaza Strip) that make up the State of Palestine. A landlocked territory near the coast of the Mediter ...

, Hezbollah

Hezbollah ( ; , , ) is a Lebanese Shia Islamist political party and paramilitary group. Hezbollah's paramilitary wing is the Jihad Council, and its political wing is the Loyalty to the Resistance Bloc party in the Lebanese Parliament. I ...

in Lebanon

Lebanon, officially the Republic of Lebanon, is a country in the Levant region of West Asia. Situated at the crossroads of the Mediterranean Basin and the Arabian Peninsula, it is bordered by Syria to the north and east, Israel to the south ...

and northern Israel, and other Iranian-backed militias in Syria. Iranian-backed militias also engaged in clashes with the United States, while the Houthis

The Houthis, officially known as Ansar Allah, is a Zaydism, Zaydi Shia Islamism, Shia Islamist political and military organization that emerged from Yemen in the 1990s. It is predominantly made up of Zaydi Shias, with their namesake leadersh ...

blockaded the Red Sea in protest, to which the United States responded with airstrikes in Yemen

Yemen, officially the Republic of Yemen, is a country in West Asia. Located in South Arabia, southern Arabia, it borders Saudi Arabia to Saudi Arabia–Yemen border, the north, Oman to Oman–Yemen border, the northeast, the south-eastern part ...

, Iraq, and Syria.

Attempts to reach a peaceful settlement

The PLO's participation in diplomatic negotiations was dependent on its complete disavowal of terrorism and recognition of Israel's "right to exist." This stipulation required the PLO to abandon its objective of reclaiming all of historic Palestine and instead focus on the 22 percent which came under Israeli military control in 1967.Palestinian Declaration of Independence

The Palestinian Declaration of Independence formally established the State of Palestine, and was written by Palestinians, Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish and proclaimed by Yasser Arafat on 15 November 1988 (5 Rabi' al-Thani, Rabiʽ al-Thani 1409 ...

formally consecrated this objective. This declaration, which was based on resolutions from the Palestine National Council sessions in the late 1970s and 1980s, advocated for the creation of a Palestinian state comprising the West Bank, Gaza Strip, and East Jerusalem, within the borders set by the 1949 armistice lines prior to 5 June 1967. Following the declaration, Arafat explicitly denounced all forms of terrorism and affirmed the PLO's acceptance of UN Resolutions 242 and 338, as well as the recognition of Israel's right to exist. All the conditions defined by Henry Kissinger for US negotiations with the PLO had now been met.

Then-Israeli prime minister Yitzhak Shamir

Yitzhak Shamir (, ; born Yitzhak Yezernitsky; October 22, 1915 – June 30, 2012) was an Israeli politician and the seventh prime minister of Israel, serving two terms (1983–1984, 1986–1992). Before the establishment of the State of Israel, ...

stood behind the stance that the PLO was a terrorist organization. He maintained a strict stance against any concessions, including withdrawal from occupied Palestinian territories, recognition of or negotiations with the PLO, and especially the establishment of a Palestinian state. Shamir viewed the U.S. decision to engage in dialogue with the PLO as a mistake that threatened the existing territorial status quo. He argued that negotiating with the PLO meant accepting the existence of a Palestinian state and hence was unacceptable.

The peace process

The term "peace process" refers to the step-by-step approach to resolving the conflict. Having originally entered into usage to describe the US mediated negotiations between Israel and surrounding Arab countries, notably Egypt, the term "peace-process" has grown to be associated with an emphasis on the negotiation process rather than on presenting a comprehensive solution to the conflict.[: "On the contrary, in August 1996 the PLO honored its commitment to revoke its original charter, which had denied the legitimacy of Israel and called for the armed liberation of all of Palestine. As well, by 1996 the PA and its police forces had become increasingly successful in their efforts to end the terrorism of Hamas and other Islamic extremists, even cooperating with the Israeli forces. As a result, there were now far fewer terrorist attacks than in the preceding few years."]

Meron Benvenisti, former deputy mayor of Jerusalem, observed that life became harsher for Palestinians during this period as state violence increased and Palestinian land continued to be expropriated as settlements expanded.

Creation of the Palestinian Authority and security cooperation

Core to the Oslo Accords was the creation of the Palestinian Authority and the security cooperation it would enter into with the Israeli military authorities in what has been described as the "outsourcing" of the occupation to the PA.Dennis Ross

Dennis B. Ross (born November 26, 1948) is an American diplomat and author. He served as the Director of Policy Planning in the State Department under President George H. W. Bush, the special Middle East coordinator under President Bill Clinton ...

describes the Wye as having successfully reduced both violent and non-violent protests, both of which he considers to be "inconsistent with the spirit of Wye." Watson claims that the PA frequently violated its obligations to curb incitement and its record on curbing terrorism and other security obligations under the Wye River Memorandum was, at best, mixed.

Oslo Accords (1993, 1995)

In 1993, Israeli officials led by

In 1993, Israeli officials led by Yitzhak Rabin

Yitzhak Rabin (; , ; 1 March 1922 – 4 November 1995) was an Israeli politician, statesman and general. He was the prime minister of Israel, serving two terms in office, 1974–1977, and from 1992 until Assassination of Yitzhak Rabin, his ass ...

and Palestinian leaders from the Palestine Liberation Organization

The Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO; ) is a Palestinian nationalism, Palestinian nationalist coalition that is internationally recognized as the official representative of the Palestinians, Palestinian people in both the occupied Pale ...

led by Yasser Arafat

Yasser Arafat (4 or 24 August 1929 – 11 November 2004), also popularly known by his Kunya (Arabic), kunya Abu Ammar, was a Palestinian political leader. He was chairman of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) from 1969 to 2004, Presid ...

strove to find a peaceful solution through what became known as the Oslo peace process. A crucial milestone in this process was Arafat's letter of recognition of Israel's right to exist. Emblematic of the asymmetry in the Oslo process, Israel was not required to, and did not, recognize the right of a Palestinian state to exist. In 1993, the Declaration of Principles (or Oslo I) was signed and set forward a framework for future Israeli–Palestinian negotiations, in which key issues would be left to "final status" talks. The stipulations of the Oslo agreements ran contrary to the international consensus for resolving the conflict; the agreements did not uphold Palestinian self-determination or statehood and repealed the internationally accepted interpretation of UN Resolution 242 that land cannot be acquired by war.assassination of Yitzhak Rabin

Yitzhak Rabin, the prime minister of Israel, was assassinated on 4 November 1995 at 21:30, at the end of a rally in support of the Oslo Accords at the Kings of Israel Square in Tel Aviv. The assailant was Yigal Amir, an Israeli law student and u ...

in November 1995 and the election of Netanyahu in 1996, finally unraveling when Arafat and Ehud Barak

Ehud Barak ( ; born Ehud Brog; 12 February 1942) is an Israeli former general and politician who served as the Prime Minister of Israel, prime minister from 1999 to 2001. He was leader of the Israeli Labor Party, Labor Party between 1997 and 20 ...

failed to reach an agreement at Camp David in July 2000 and later at Taba in 2001.

Camp David Summit (2000)

In July 2000, US President Bill Clinton convened a peace summit between Palestinian President Yasser Arafat and Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Barak. Barak reportedly put forward the following as "bases for negotiation", via the US to the Palestinian President: a non-militarized Palestinian state split into 3–4 parts containing 87–92% of the West Bank after having already given up 78% of historic Palestine. Thus, an Israeli offer of 91 percent of the West Bank (5,538km2 of the West Bank translates into only 86 percent from the Palestinian perspective), including Arab parts of East Jerusalem and the entire Gaza Strip,[

After the Camp David summit, a narrative emerged, supported by Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Barak and his foreign minister Shlomo Ben-Ami, as well as US officials including Dennis Ross and Madeleine Albright, that Yasser Arafat had rejected a generous peace offer from Israel and instead incited a violent uprising. This narrative suggested that Arafat was not interested in a two-state solution, but rather aimed to destroy Israel and take over all of Palestine. This view was widely accepted in US and Israeli public opinion. Nearly all scholars and most Israeli and US officials involved in the negotiations have rejected this narrative. These individuals include prominent Israeli negotiators, the IDF chief of staff, the head of the IDF's intelligence bureau, the head of the Shin Bet as well as their advisors.][: "After Camp David, a new mythology emerged perpetrated by Barak and his foreign minister Shlomo Ben-Ami, with the support of Dennis Ross, Clinton's secretary of state Madeleine Albright, and to a considerable extent Clinton himself. The mythology holds that at Camp David, Barak made a generous and unprecedented offer to the Palestinians, only to be met by a shocking if not perverse rejection by Arafat who then ordered a violent uprising at just the moment when the chances for peace had never been greater.

For example, shortly after the conclusion of Camp David, Ben-Ami gave a long interview with Haaretz, claiming that Arafat did not go to Camp David to reach a compromise settlement but rather treated the negotiations as "a huge camouflage net behind which he sought to undermine the very idea of two states for two nations. ... Camp David collapsed over the fact that he Palestiniansrefused to get in the game. They refused to make a counterproposal ... and didn't succeed in conveying ... that at some point the demands would have an end."

The implied premise of Barak and Ben-Ami was that Arafat thought the Palestinians held all the cards, so that if he held out long enough, he would eventually reach his goal: the destruction of Israel in stages and the takeover of all of historic Palestine. This view became widely accepted in US and Israeli public opinion...

This and other Camp David mythologies have been rejected, both at the time and in retrospect, by nearly all scholars and knowledgeable journalists and by most Israeli and US officials who participated in the negotiations. In particular, they were challenged in interviews and memoirs by the leading Israeli negotiators, among them Ron Pundak, Yossi Beilin, Oden Era, Shaul Arieli, Yossi Ginosser, Moshe Amirav, and General Amnon Lipkin-Shahak, chief of staff of the IDF in 1995–1998. As well, the mythologies were strongly—and subsequently, publicly—rejected by Israel's leading military intelligence officials, including Ami Ayalon, the 2000 head of Shin Bet, and Matti Steinberg, his chief advisor—and by Amos Malka, head of the IDF's military intelligence bureau, and his second in command, Ephraim Lavie."]

No tenable solution was crafted which would satisfy both Israeli and Palestinian demands, even under intense US pressure. Clinton has long blamed Arafat for the collapse of the summit. In the months following the summit, Clinton appointed former US Senator George J. Mitchell

George John Mitchell Jr. (born August 20, 1933) is an American politician, diplomat, and lawyer. A leading member of the Democratic Party, he served as a United States senator from Maine from 1980 to 1995, and as Senate Majority Leader from 19 ...

to lead a fact-finding committee aiming to identify strategies for restoring the peace process. The committee's findings were published in 2001 with the dismantlement of existing Israeli settlements and Palestinian crackdown on militant activity being one strategy.

Developments following Camp David

Following the failed summit Palestinian and Israeli negotiators continued to meet in small groups through August and September 2000 to try to bridge the gaps between their respective positions. The United States prepared its own plan to resolve the outstanding issues. Clinton's presentation of the US proposals was delayed by the advent of the

Following the failed summit Palestinian and Israeli negotiators continued to meet in small groups through August and September 2000 to try to bridge the gaps between their respective positions. The United States prepared its own plan to resolve the outstanding issues. Clinton's presentation of the US proposals was delayed by the advent of the Second Intifada

The Second Intifada (; ), also known as the Al-Aqsa Intifada, was a major uprising by Palestinians against Israel and its Israeli-occupied territories, occupation from 2000. Starting as a civilian uprising in Jerusalem and October 2000 prot ...

at the end of September.[

Clinton's plan, eventually presented on 23 December 2000, proposed the establishment of a sovereign Palestinian state in the Gaza Strip and 94–96 percent of the West Bank plus the equivalent of 1–3 percent of the West Bank in land swaps from pre-1967 Israel. On Jerusalem, the plan stated that "the general principle is that Arab areas are Palestinian and that Jewish areas are Israeli." The holy sites were to be split on the basis that Palestinians would have sovereignty over the Temple Mount/Noble sanctuary, while the Israelis would have sovereignty over the Western Wall. On refugees the plan suggested a number of proposals including financial compensation, the right of return to the Palestinian state, and Israeli acknowledgment of suffering caused to the Palestinians in 1948. Security proposals referred to a "non-militarized" Palestinian state, and an international force for border security. Both sides accepted Clinton's plan][

]

Taba Summit (2001)

The Israeli negotiation team presented a new map at the Taba Summit

The Taba Summit (also known as Taba Talks, Taba Conference or shortened to Taba) were talks between Israel and the Palestinian Authority, held from 21 to 27 January 2001 in Taba, Egypt. The talks took place during a political transition period � ...

in Taba, Egypt, in January 2001. The proposition removed the "temporarily Israeli controlled" areas, and the Palestinian side accepted this as a basis for further negotiation. With Israeli elections looming the talks ended without an agreement but the two sides issued a joint statement attesting to the progress they had made: "The sides declare that they have never been closer to reaching an agreement and it is thus our shared belief that the remaining gaps could be bridged with the resumption of negotiations following the Israeli elections." The following month the Likud

Likud (, ), officially known as Likud – National Liberal Movement (), is a major Right-wing politics, right-wing, political party in Israel. It was founded in 1973 by Menachem Begin and Ariel Sharon in an alliance with several right-wing par ...

party candidate Ariel Sharon

Ariel Sharon ( ; also known by his diminutive Arik, ; 26 February 192811 January 2014) was an Israeli general and politician who served as the prime minister of Israel from March 2001 until April 2006.

Born in Kfar Malal in Mandatory Palestin ...

defeated Ehud Barak in the Israeli elections and was elected as Israeli prime minister on 7 February 2001. Sharon's new government chose not to resume the high-level talks.[

]

Road map for peace (2002–2003)

One peace proposal, presented by the

One peace proposal, presented by the Quartet

In music, a quartet (, , , , ) is an ensemble of four singers or instrumental performers.

Classical String quartet

In classical music, one of the most common combinations of four instruments in chamber music is the string quartet. String quar ...

of the European Union, Russia, the United Nations and the United States on 17 September 2002, was the Road Map for Peace. This plan did not attempt to resolve difficult questions such as the fate of Jerusalem or Israeli settlements, but left that to be negotiated in later phases of the process. The proposal never made it beyond the first phase, whose goals called for a halt to both Israeli settlement construction and Israeli–Palestinian violence. Neither goal has been achieved as of November 2015.

The Annapolis Conference was a Middle East

The Annapolis Conference was a Middle East peace conference

A peace conference is a diplomatic meeting where representatives of states, armies, or other warring parties converge to end hostilities by negotiation and signing and ratifying a peace treaty.

Significant international peace conferences in ...

held on 27 November 2007, at the United States Naval Academy

The United States Naval Academy (USNA, Navy, or Annapolis) is a United States Service academies, federal service academy in Annapolis, Maryland. It was established on 10 October 1845 during the tenure of George Bancroft as United States Secre ...

in Annapolis, Maryland

Annapolis ( ) is the capital of the U.S. state of Maryland. It is the county seat of Anne Arundel County and its only incorporated city. Situated on the Chesapeake Bay at the mouth of the Severn River, south of Baltimore and about east ...

, United States. The conference aimed to revive the Israeli–Palestinian peace process

Intermittent discussions are held by various parties and proposals put forward in an attempt to resolve the Israeli–Palestinian conflict through a peace process. Since the 1970s, there has been a parallel effort made to find terms upon which ...

and implement the ''" Roadmap for peace"''. The conference ended with the issuing of a joint statement from all parties. After the Annapolis Conference, the negotiations were continued. Both Mahmoud Abbas and Ehud Olmert presented each other with competing peace proposals. Ultimately no agreement was reached.[''Joint Understanding Read by President Bush at Annapolis Conference'']

. Memorial Hall, United States Naval Academy

The United States Naval Academy (USNA, Navy, or Annapolis) is a United States Service academies, federal service academy in Annapolis, Maryland. It was established on 10 October 1845 during the tenure of George Bancroft as United States Secre ...

, Annapolis, Maryland; 27 November 2007

Arab Peace Initiative (2002, 2007, 2017)

The Arab Peace Initiative ( ''Mubādirat as-Salām al-ʿArabīyyah''), also known as the Saudi Initiative, was first proposed by Crown Prince

The Arab Peace Initiative ( ''Mubādirat as-Salām al-ʿArabīyyah''), also known as the Saudi Initiative, was first proposed by Crown Prince Abdullah of Saudi Arabia

Abdullah bin Abdulaziz Al Saud (, ; 1 August 1924 – 23 January 2015) was King of Saudi Arabia, King and Prime Minister of Saudi Arabia from 1 August 2005 until his death in 2015. Prior to his accession, he was Crown Prince of Saudi Arabia si ...

at the 2002 Beirut summit. The initiative is a proposed solution to the Arab–Israeli conflict as a whole, and the Israeli–Palestinian conflict in particular. The initiative was initially published on 28 March 2002, at the Beirut summit, and agreed upon again at the 2007 Riyadh summit. Unlike the Road Map for Peace, it spelled out "final solution" borders based on the UN borders established before the 1967 Six-Day War

The Six-Day War, also known as the June War, 1967 Arab–Israeli War or Third Arab–Israeli War, was fought between Israel and a coalition of Arab world, Arab states, primarily United Arab Republic, Egypt, Syria, and Jordan from 5 to 10June ...

. It offered full normalization of relations with Israel, in exchange for the withdrawal of its forces from all the occupied territories, including the Golan Heights

The Golan Heights, or simply the Golan, is a basaltic plateau at the southwest corner of Syria. It is bordered by the Yarmouk River in the south, the Sea of Galilee and Hula Valley in the west, the Anti-Lebanon mountains with Mount Hermon in t ...

, to recognize "an independent Palestinian state with East Jerusalem as its capital" in the West Bank and Gaza Strip, as well as a "just solution" for the Palestinian refugees.

The Palestinian Authority

The Palestinian Authority (PA), officially known as the Palestinian National Authority (PNA), is the Fatah-controlled government body that exercises partial civil control over the Palestinian enclaves in the Israeli occupation of the West Bank, ...

led by Yasser Arafat

Yasser Arafat (4 or 24 August 1929 – 11 November 2004), also popularly known by his Kunya (Arabic), kunya Abu Ammar, was a Palestinian political leader. He was chairman of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) from 1969 to 2004, Presid ...

immediately embraced the initiative. His successor Mahmoud Abbas

Mahmoud Abbas (; born 15 November 1935), also known by the Kunya (Arabic), kunya Abu Mazen (, ), is a Palestinian politician who has been serving as the second president of Palestine and the President of the Palestinian National Authority, P ...

also supported the plan and officially asked U.S. President Barack Obama

Barack Hussein Obama II (born August 4, 1961) is an American politician who was the 44th president of the United States from 2009 to 2017. A member of the Democratic Party, he was the first African American president in American history. O ...

to adopt it as part of his Middle East policy.Hamas

The Islamic Resistance Movement, abbreviated Hamas (the Arabic acronym from ), is a Palestinian nationalist Sunni Islam, Sunni Islamism, Islamist political organisation with a military wing, the Qassam Brigades. It has Gaza Strip under Hama ...

, the elected government of the Gaza Strip

The Gaza Strip, also known simply as Gaza, is a small territory located on the eastern coast of the Mediterranean Sea; it is the smaller of the two Palestinian territories, the other being the West Bank, that make up the State of Palestine. I ...

, was deeply divided,Ariel Sharon

Ariel Sharon ( ; also known by his diminutive Arik, ; 26 February 192811 January 2014) was an Israeli general and politician who served as the prime minister of Israel from March 2001 until April 2006.

Born in Kfar Malal in Mandatory Palestin ...

rejected the initiative as a "non-starter"Ehud Olmert

Ehud Olmert (; , ; born 30 September 1945) is an Israeli politician and lawyer who served as the prime minister of Israel from 2006 to 2009.

The son of a former Herut politician, Olmert was first elected to the Knesset for Likud in 1973, at th ...

gave a cautious welcome to the plan. In 2015, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu

Benjamin Netanyahu (born 21 October 1949) is an Israeli politician who has served as the prime minister of Israel since 2022, having previously held the office from 1996 to 1999 and from 2009 to 2021. Netanyahu is the longest-serving prime min ...

expressed tentative support for the Initiative,

Current status

Apartheid

In July 2024, the International Court of Justice

The International Court of Justice (ICJ; , CIJ), or colloquially the World Court, is the only international court that Adjudication, adjudicates general disputes between nations, and gives advisory opinions on International law, internation ...

determined that Israeli policies violate the .[Aeyal Gross]

'The ICJ Just Demolished One of Israel's Key Defenses of the Occupation,'

Haaretz

''Haaretz'' (; originally ''Ḥadshot Haaretz'' – , , ) is an List of newspapers in Israel, Israeli newspaper. It was founded in 1918, making it the longest running newspaper currently in print in Israel. The paper is published in Hebrew lan ...

19 July 2024. As of 2022, all the major Israeli and international human rights organizations were in agreement that Israeli actions constituted the crime of apartheid

The crime of apartheid is defined by the 2002 Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court as inhumane acts of a character similar to other crimes against humanity "committed in the context of an institutionalized regime of systematic oppres ...

. In April 2021, Human Rights Watch

Human Rights Watch (HRW) is an international non-governmental organization that conducts research and advocacy on human rights. Headquartered in New York City, the group investigates and reports on issues including War crime, war crimes, crim ...

released its report ''A Threshold Crossed'', describing the policies of Israel towards Palestinians living in Israel, the West Bank and Gaza constituted the crime of apartheid

The crime of apartheid is defined by the 2002 Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court as inhumane acts of a character similar to other crimes against humanity "committed in the context of an institutionalized regime of systematic oppres ...

.Amnesty International

Amnesty International (also referred to as Amnesty or AI) is an international non-governmental organization focused on human rights, with its headquarters in the United Kingdom. The organization says that it has more than ten million members a ...

on 1 February 2022.

In 2018, the Knesset

The Knesset ( , ) is the Unicameralism, unicameral legislature of Israel.

The Knesset passes all laws, elects the President of Israel, president and Prime Minister of Israel, prime minister, approves the Cabinet of Israel, cabinet, and supe ...

passed the Nation-State law which the Israeli legal group Adalah nicknamed the "Apartheid law." Adalah described the Nation-State law as "constitutionally enshrining Jewish supremacy and the identity of the State of Israel as the nation-state of the Jewish people." The Nation-State law is a Basic Law

A basic law is either a codified constitution, or in countries with uncodified constitutions, a law designed to have the effect of a constitution. The term ''basic law'' is used in some places as an alternative to "constitution" and may be inte ...