Iran–United Kingdom Relations on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Iran–United Kingdom relations are the bilateral relations between the

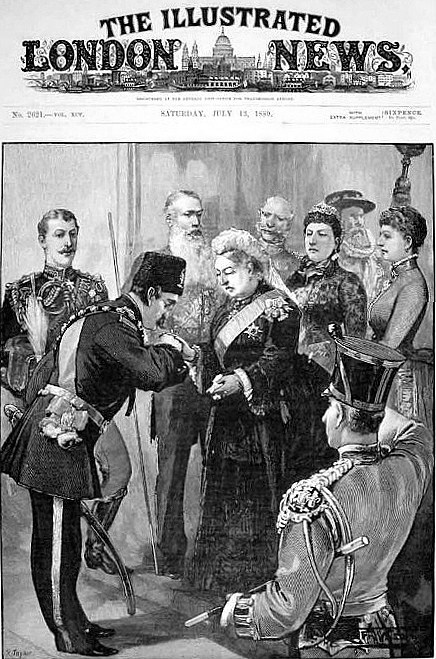

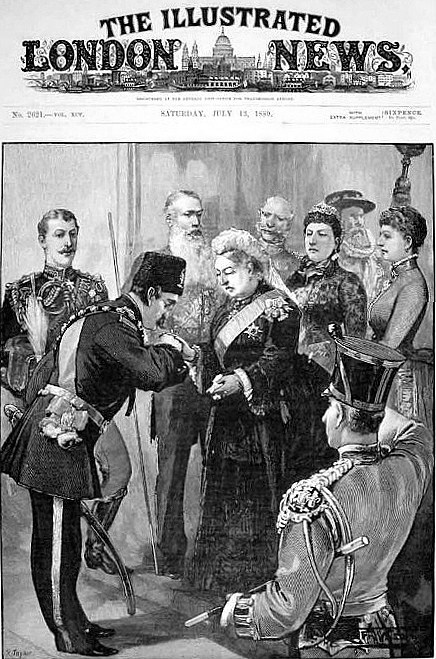

Anglo-Persian relations picked up momentum as a weakened

Anglo-Persian relations picked up momentum as a weakened

On 30 April 1980, the Iranian Embassy in London was taken over by a six-man terrorist team holding the building for six days until the hostages were rescued by a raid by the SAS. After the Revolution of Iran in 1979, Britain suspended all diplomatic relations with Iran. Britain did not have an embassy until it was reopened in 1988. A year after the re-establishment of the British embassy in Tehran,

On 30 April 1980, the Iranian Embassy in London was taken over by a six-man terrorist team holding the building for six days until the hostages were rescued by a raid by the SAS. After the Revolution of Iran in 1979, Britain suspended all diplomatic relations with Iran. Britain did not have an embassy until it was reopened in 1988. A year after the re-establishment of the British embassy in Tehran,

Sean Rayment, ''

In July 2013, the UK considered opening better relations with Iran "step-by-step" following the

In July 2013, the UK considered opening better relations with Iran "step-by-step" following the

On 19 July 2019, Iran media reported that the Swedish owned but British-flagged oil tanker ''Stena Impero'' had been seized by the Iranian Revolutionary Guard in the Strait of Hormuz. A first tanker, MV ''Mesdar'', which was a Liberian-flagged vessel managed in the UK, jointly Algerian and Japanese owned, was boarded but later released. Iran stated that the British-flagged ship had collided with and damaged an Iranian vessel, and had ignored warnings by Iranian authorities. During the incident HMS ''Montrose'' was stationed too far away to offer timely assistance; when the

On 19 July 2019, Iran media reported that the Swedish owned but British-flagged oil tanker ''Stena Impero'' had been seized by the Iranian Revolutionary Guard in the Strait of Hormuz. A first tanker, MV ''Mesdar'', which was a Liberian-flagged vessel managed in the UK, jointly Algerian and Japanese owned, was boarded but later released. Iran stated that the British-flagged ship had collided with and damaged an Iranian vessel, and had ignored warnings by Iranian authorities. During the incident HMS ''Montrose'' was stationed too far away to offer timely assistance; when the

Iran-UK relation timeline: BBC

UK-Iran relations - parstimes.com

The British-Iranian Chamber of Commerce

The Iran Society of London

The Irano-British Chamber of Commerce

Iran's Embassy in London

The British Embassy in Tehran

{{DEFAULTSORT:Iran-United Kingdom Relations

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Northwestern Europe, off the coast of European mainland, the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

and Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran (IRI) and also known as Persia, is a country in West Asia. It borders Iraq to the west, Turkey, Azerbaijan, and Armenia to the northwest, the Caspian Sea to the north, Turkmenistan to the nort ...

. Iran, which was called Persia by the West before 1935, has had political relations with England since the late Ilkhanate

The Ilkhanate or Il-khanate was a Mongol khanate founded in the southwestern territories of the Mongol Empire. It was ruled by the Il-Khans or Ilkhanids (), and known to the Mongols as ''Hülegü Ulus'' (). The Ilkhanid realm was officially known ...

period (13th century) when King Edward I of England sent Geoffrey of Langley to the Ilkhanid court to seek an alliance. Until the early nineteenth century, Iran was a remote and legendary country for Britain, so much so that the European country never seriously established a diplomatic center, such as a consulate or embassy

A diplomatic mission or foreign mission is a group of people from a Sovereign state, state or organization present in another state to represent the sending state or organization officially in the receiving or host state. In practice, the phrase ...

. By the middle of the nineteenth century, Iran grew in importance as a buffer state to the United Kingdom's dominion over India. Britain fostered conflict between Iran and Afghanistan

Afghanistan, officially the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan, is a landlocked country located at the crossroads of Central Asia and South Asia. It is bordered by Pakistan to the Durand Line, east and south, Iran to the Afghanistan–Iran borde ...

as a means of forestalling an Afghan invasion of India.

The UK seeds a number of proximity conflicts between Iran and its neighbouring states like Azerbaijan

Azerbaijan, officially the Republic of Azerbaijan, is a Boundaries between the continents, transcontinental and landlocked country at the boundary of West Asia and Eastern Europe. It is a part of the South Caucasus region and is bounded by ...

on the countries' borders, Afghanistan on the Hirmand river and United Arab Emirates

The United Arab Emirates (UAE), or simply the Emirates, is a country in West Asia, in the Middle East, at the eastern end of the Arabian Peninsula. It is a Federal monarchy, federal elective monarchy made up of Emirates of the United Arab E ...

on possession of three disputed islands.

History of Anglo-Iranian relations

Safavid era

In 1597, as Abbas I of Safavid sought to establish an alliance against his arch rival, the Ottomans, he receivedRobert Shirley

Sir Robert Shirley (or Sherley; c. 1581 – 13 July 1628) was an English traveller and adventurer, younger brother of Sir Anthony Shirley and Sir Thomas Shirley. He is notable for his help modernising and improving the Persian Safavid

...

, Anthony Shirley, and a group of 26 English envoys in Qazvin

Qazvin (; ; ) is a city in the Central District (Qazvin County), Central District of Qazvin County, Qazvin province, Qazvin province, Iran, serving as capital of the province, the county, and the district. It is the largest city in the provi ...

. Soon, the Shirley brothers were appointed by the Shah to organize and modernize the royal cavalry and train the army. The effects of these modernizations proved to be highly successful, as from then on the Safavids

The Guarded Domains of Iran, commonly called Safavid Iran, Safavid Persia or the Safavid Empire, was one of the largest and longest-lasting Iranian empires. It was ruled from 1501 to 1736 by the Safavid dynasty. It is often considered the begi ...

proved to be an equal force against their arch rival, immediately crushing them in the first war to come ( Ottoman–Safavid War (1603–1618)) and all other Safavid wars to come. Many more events followed, including the debut of the British East India Company

The East India Company (EIC) was an English, and later British, joint-stock company that was founded in 1600 and dissolved in 1874. It was formed to Indian Ocean trade, trade in the Indian Ocean region, initially with the East Indies (South A ...

into Persia, and the establishment of trade routes for silk though Jask

Jask ( and Balochi: جاشک) is a city in the Central District of Jask County, Hormozgan province, Iran, serving as capital of both the county and the district.

Demographics Population

At the time of the 2006 National Census, the city' ...

in the Strait of Hormuz

The Strait of Hormuz ( ''Tangeh-ye Hormoz'' , ''Maḍīq Hurmuz'') is a strait between the Persian Gulf and the Gulf of Oman. It provides the only sea passage from the Persian Gulf to the open ocean and is one of the world's most strategica ...

in 1616. It was from here where the likes of Sir John Malcolm

Major-General Sir John Malcolm GCB, KLS (2 May 1769 – 30 May 1833) was a Scottish soldier, diplomat, East India Company administrator, statesman, and historian.

Early life

Sir John Malcolm was born in 1769, one of seventeen children of G ...

later gained influence into the Qajarid throne.

Qajar era

Anglo-Persian relations picked up momentum as a weakened

Anglo-Persian relations picked up momentum as a weakened Safavid

The Guarded Domains of Iran, commonly called Safavid Iran, Safavid Persia or the Safavid Empire, was one of the largest and longest-lasting Iranian empires. It was ruled from 1501 to 1736 by the Safavid dynasty. It is often considered the begi ...

empire, after the short-lived revival by the military genius Nader Shah

Nader Shah Afshar (; 6 August 1698 or 22 October 1688 – 20 June 1747) was the founder of the Afsharid dynasty of Iran and one of the most powerful rulers in Iranian history, ruling as shah of Iran (Persia) from 1736 to 1747, when he was a ...

(r. 1736-1747), eventually gave way to the Qajarid dynasty, which was quickly absorbed into domestic turmoil and rivalry, while competing colonial powers rapidly sought a stable foothold in the region. While the Portuguese, British, and Dutch, competed for the south and southeast of Persia in the Persian Gulf

The Persian Gulf, sometimes called the Arabian Gulf, is a Mediterranean seas, mediterranean sea in West Asia. The body of water is an extension of the Arabian Sea and the larger Indian Ocean located between Iran and the Arabian Peninsula.Un ...

, Imperial Russia

Imperial is that which relates to an empire, emperor/empress, or imperialism.

Imperial or The Imperial may also refer to:

Places

United States

* Imperial, California

* Imperial, Missouri

* Imperial, Nebraska

* Imperial, Pennsylvania

* ...

was largely left unchallenged in the north as it plunged southward to establish dominance in Persia's northern territories.

A weakened and bankrupted royal court under Fath Ali Shah

Fath-Ali Shah Qajar (; 5 August 1772 – 24 October 1834) was the second Shah of Qajar Iran. He reigned from 17 June 1797 until his death on 24 October 1834. His reign saw the irrevocable ceding of Iran's northern territories in the Caucasus, com ...

was forced to sign the Treaty of Gulistan

The Treaty of Gulistan (also spelled Golestan: ; ) was a peace treaty concluded between the Russian Empire and Qajar Iran on 24 October 1813 in the village of Gülüstan, Goranboy, Gulistan (now in Goranboy District, the Goranboy District of Azerb ...

in 1813, followed by the Treaty of Turkmenchay

The Treaty of Turkmenchay (; ) was an agreement between Qajar Iran and the Russian Empire, which concluded the Russo-Persian War (1826–1828). It was second of the series of treaties (the first was the 1813 Treaty of Gulistan and the last, the ...

after efforts by Abbas Mirza

Abbas Mirza (; 26 August 1789 – 25 October 1833) was the Qajar dynasty, Qajar crown prince of Qajar Iran, Iran during the reign of his father Fath-Ali Shah Qajar (). As governor of the vulnerable Azerbaijan (Iran), Azerbaijan province, he played ...

failed to secure Persia's northern front against Imperial Russia

Imperial is that which relates to an empire, emperor/empress, or imperialism.

Imperial or The Imperial may also refer to:

Places

United States

* Imperial, California

* Imperial, Missouri

* Imperial, Nebraska

* Imperial, Pennsylvania

* ...

. The treaties were prepared by the Sir Gore Ouseley with the aid of the British Foreign Office

The Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) is the ministry of foreign affairs and a ministerial department of the government of the United Kingdom.

The office was created on 2 September 2020 through the merger of the Foreign an ...

in London

London is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of both England and the United Kingdom, with a population of in . London metropolitan area, Its wider metropolitan area is the largest in Wester ...

. In fact, Iran's current southern and eastern boundaries were determined by none other than the British during the Anglo-Persian War

The Anglo-Persian War, also known as the Anglo-Iranian War (), was a war fought between the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, United Kingdom and Qajar Iran, Iran, which was ruled by the Qajar dynasty. The war had the British oppose a ...

(1856 to 1857). After repelling Nasereddin Shah's attack in Herat

Herāt (; Dari/Pashto: هرات) is an oasis city and the third-largest city in Afghanistan. In 2020, it had an estimated population of 574,276, and serves as the capital of Herat Province, situated south of the Paropamisus Mountains (''Se ...

in 1857, the British government assigned Frederic John Goldsmid of the Indo-European Telegraph Department to determine the borders between Persia and British India

The provinces of India, earlier presidencies of British India and still earlier, presidency towns, were the administrative divisions of British governance in South Asia. Collectively, they have been called British India. In one form or another ...

during the 1860s.

By the end of the 19th century, Britain's dominance became so pronounced that Khuzestan

Khuzestan province () is one of the 31 Provinces of Iran. Located in the southwest of the country, the province borders Iraq and the Persian Gulf, covering an area of . Its capital is the city of Ahvaz. Since 2014, it has been part of Iran's ...

, Bushehr

Bushehr (; ) is a port city in the Central District (Bushehr County), Central District of Bushehr County, Bushehr province, Bushehr province, Iran, serving as capital of the province, the county, and the district.

Etymology

The roots of the n ...

, and a host of other cities in southern Persia were occupied by Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the north-west coast of continental Europe, consisting of the countries England, Scotland, and Wales. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the List of European ...

, and the central government in Tehran

Tehran (; , ''Tehrân'') is the capital and largest city of Iran. It is the capital of Tehran province, and the administrative center for Tehran County and its Central District (Tehran County), Central District. With a population of around 9. ...

was left with no power to even select its own ministers without the approval of the Anglo-Russian consulates. Morgan Shuster, for example, had to resign under tremendous British and Russian pressure on the royal court. Shuster's book ''The Strangling of Persia'' is a recount of the details of these events, a harsh criticism of Britain

Britain most often refers to:

* Great Britain, a large island comprising the countries of England, Scotland and Wales

* The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, a sovereign state in Europe comprising Great Britain and the north-eas ...

and Imperial Russia

Imperial is that which relates to an empire, emperor/empress, or imperialism.

Imperial or The Imperial may also refer to:

Places

United States

* Imperial, California

* Imperial, Missouri

* Imperial, Nebraska

* Imperial, Pennsylvania

* ...

.

Pahlavi era

Of the public outcry against the inability of the Persian throne to maintain its political and economic independence from Great Britain andImperial Russia

Imperial is that which relates to an empire, emperor/empress, or imperialism.

Imperial or The Imperial may also refer to:

Places

United States

* Imperial, California

* Imperial, Missouri

* Imperial, Nebraska

* Imperial, Pennsylvania

* ...

in the face of events such as the Anglo-Russian Convention of 1907 and "the 1919 treaty", one result was the Persian Constitutional Revolution

The Persian Constitutional Revolution (, or ''Enghelāb-e Mashrūteh''), also known as the Constitutional Revolution of Iran, took place between 1905 and 1911 during the Qajar Iran, Qajar era. The revolution led to the establishment of a Majl ...

, which eventually resulted in the fall of the Qajar dynasty.

The great tremor of the Persian political landscape occurred when the involvement of General Edmund Ironside eventually led to the rise of Reza Shah Pahlavi

Reza Shah Pahlavi born Reza Khan (15 March 1878 – 26 July 1944) was shah of Iran from 1925 to 1941 and founder of the roughly 53 years old Pahlavi dynasty. Originally a military officer, he became a politician, serving as minister of war an ...

in the 1920s. The popular view that the British were involved in the 1921 coup was noted as early as March 1921 by the American embassy and relayed to the Iran desk at the Foreign Office. A British Embassy report from 1932 concedes that the British put Reza Shah "on the throne".

A novel chapter in Anglo-Iranian relations had begun when Iran canceled its capitulation agreements with foreign powers in 1928. Iran's success in revoking the capitulation treaties, and the failure of the Anglo-Iranian Agreement of 1919 earlier, led to intense diplomatic efforts by the British government to regularize relations between the two countries on a treaty basis. The most intractable challenge, however, proved to be Iran's assiduous efforts to revise the terms whereby the APOC retained near monopoly control over the oil industry in Iran as a result of the concession granted to William Knox D'Arcy

William Knox D'Arcy (11 October 18491 May 1917) was a British-Australian businessman who was one of the principal founders of the Energy in Iran, oil and petrochemical industry in Persia (Iran). The D’Arcy Concession was signed in 1901 and all ...

in 1901 by the Qajar King of the period.

The attempt to revise the terms of the oil concession on a more favorable basis for Iran led to protracted negotiations that took place in Tehran, Lausanne

Lausanne ( , ; ; ) is the capital and largest List of towns in Switzerland, city of the Swiss French-speaking Cantons of Switzerland, canton of Vaud, in Switzerland. It is a hilly city situated on the shores of Lake Geneva, about halfway bet ...

, London and Paris between Teymourtash and the Chairman of APOC, Sir John Cadman, spanning the years from 1928 to 1932. Despite much progress, Rezā Shāh Pahlavi was soon to assert his authority by dramatically inserting himself into the negotiations. The Monarch attended a meeting of the Council of Ministers in November 1932, and after publicly rebuking Teymourtash for his failure to secure an agreement, dictated a letter to cabinet canceling the D'Arcy Agreement. The Iranian Government notified APOC that it would cease further negotiations and demanded cancellation of the D'Arcy concession. Rejecting the cancellation, the British government espoused the claim on behalf of APOC and brought the dispute before the Permanent Court of International Justice

The Permanent Court of International Justice, often called the World Court, existed from 1922 to 1946. It was an international court attached to the League of Nations. Created in 1920 (although the idea of an international court was several cent ...

at The Hague

The Hague ( ) is the capital city of the South Holland province of the Netherlands. With a population of over half a million, it is the third-largest city in the Netherlands. Situated on the west coast facing the North Sea, The Hague is the c ...

, asserting that it regarded itself "as entitled to take all such measures as the situation may demand for the Company's protection." At this point, Hassan Taqizadeh

Sayyed Hasan Taqizādeh (; September 27, 1878 in Tabriz, Iran – January 28, 1970 in Tehran, Iran) was an influential Iranian politician and diplomat, of Azerbaijani origin, during the Qajar era under the reign of Mohammad Ali Shah Qajar ...

, the new Iranian minister to have been entrusted the task of assuming responsibility for the oil dossier, was to intimate to the British that the cancellation was simply meant to expedite negotiations and that it would constitute political suicide for Iran to withdraw from negotiations.

Rezā Shāh was removed from power abruptly during the Anglo-Soviet invasion of Iran

The Anglo-Soviet invasion of Iran, also known as the Anglo-Soviet invasion of Persia, was the joint invasion of the neutral Imperial State of Iran by the United Kingdom and the Soviet Union in August 1941. The two powers announced that they w ...

during World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

. The new Shah, Crown Prince

A crown prince or hereditary prince is the heir apparent to the throne in a royal or imperial monarchy. The female form of the title, crown princess, is held by a woman who is heir apparent or is married to the heir apparent.

''Crown prince ...

Mohammad Reza Pahlavi

Mohammad Reza Pahlavi (26 October 1919 – 27 July 1980) was the last List of monarchs of Iran, Shah of Iran, ruling from 1941 to 1979. He succeeded his father Reza Shah and ruled the Imperial State of Iran until he was overthrown by the ...

, signed a Tripartite Treaty Alliance with Britain and the Soviet Union in January 1942, to aid in the allied war effort in a non-military way.

Contemporary era

In 1951, the Iranians nationalized the oil through a parliamentary bill on 21 March 1951. This caused a lot of tension between Iran and the UK. After the events of 1953, scores of Iranian political activists from the National and Communist parties were jailed or killed. This coup only added to the deep mistrust towards the British in Iran. It has since been very common in Iranian culture to mistrust British government. The end ofWorld War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

brought the start of American dominance in Iran's political arena, and with an anti-Soviet Cold War

The Cold War was a period of global Geopolitics, geopolitical rivalry between the United States (US) and the Soviet Union (USSR) and their respective allies, the capitalist Western Bloc and communist Eastern Bloc, which lasted from 1947 unt ...

brewing, the United States quickly moved to convert Iran into an anti-communist bloc, thus considerably diminishing Britain's influence on Iran for years to come. Operation Ajax and the fall of Prime Minister Mosaddegh was perhaps the last of the large British involvements in Iranian politics in the Pahlavi era. The British forces began to withdraw from Persian Gulf

The Persian Gulf, sometimes called the Arabian Gulf, is a Mediterranean seas, mediterranean sea in West Asia. The body of water is an extension of the Arabian Sea and the larger Indian Ocean located between Iran and the Arabian Peninsula.Un ...

in 1968. This was done out of economic considerations as the British simply could not continue to afford the costs of administration. (See also East of Suez

''East of Suez'' is a term used in United Kingdom, British military and political discussions in reference to interests east of the Suez Canal, and may or may not include the Middle East.

). As part of this policy, in 1971, the then British government decided not to support the Shah and eventually, the patronage of the United Kingdom ended, and consequently, this role was filled by the US.

The Islamic Republic

On 30 April 1980, the Iranian Embassy in London was taken over by a six-man terrorist team holding the building for six days until the hostages were rescued by a raid by the SAS. After the Revolution of Iran in 1979, Britain suspended all diplomatic relations with Iran. Britain did not have an embassy until it was reopened in 1988. A year after the re-establishment of the British embassy in Tehran,

On 30 April 1980, the Iranian Embassy in London was taken over by a six-man terrorist team holding the building for six days until the hostages were rescued by a raid by the SAS. After the Revolution of Iran in 1979, Britain suspended all diplomatic relations with Iran. Britain did not have an embassy until it was reopened in 1988. A year after the re-establishment of the British embassy in Tehran, Ayatollah Khomeini

Ruhollah Musavi Khomeini (17 May 1900 or 24 September 19023 June 1989) was an Iranian revolutionary, politician, political theorist, and religious leader. He was the founder of the Islamic Republic of Iran and the main leader of the Iranian ...

issued a ''fatwa

A fatwa (; ; ; ) is a legal ruling on a point of Islamic law (sharia) given by a qualified Islamic jurist ('' faqih'') in response to a question posed by a private individual, judge or government. A jurist issuing fatwas is called a ''mufti'', ...

'' ordering Muslims across the world to kill British author Salman Rushdie

Sir Ahmed Salman Rushdie ( ; born 19 June 1947) is an Indian-born British and American novelist. His work often combines magic realism with historical fiction and primarily deals with connections, disruptions, and migrations between Eastern wor ...

. Diplomatic ties with London were broken off only to be resumed at a chargé d'affaires

A (), plural ''chargés d'affaires'', often shortened to ''chargé'' (French) and sometimes in colloquial English to ''charge-D'', is a diplomat who serves as an embassy's chief of mission in the absence of the ambassador. The term is Frenc ...

level in 1990.

Current relations

Post-Cold War

Relations normalized in 1997 during PresidentMohammad Khatami

Mohammad Khatami (born 14 October 1943) is an Iranian politician and Shia cleric who served as the fifth president of Iran from 3 August 1997 to 3 August 2005. He also served as Iran's Minister of Culture from 1982 to 1992. Later, he was critic ...

's reformist administration, with Jack Straw

John Whitaker Straw (born 3 August 1946) is a British politician who served in the Cabinet from 1997 to 2010 under the Labour governments of Tony Blair and Gordon Brown. He held two of the traditional Great Offices of State, as Home Secretar ...

becoming the first high-ranking British politician to visit Tehran in 2001 since the revolution. A setback occurred in 2002 when David Reddaway was rejected by Tehran as London's ambassador, on charges of being a spy, and further deteriorated two years later when Iran seized eight British sailors in Arvand River near the border with Iraq. The sailors were pardoned and attended a goodbye ceremony with President Ahmadinejad shortly after they were released.

In February 2004, following the earthquake in Bam, Prince Charles

Charles III (Charles Philip Arthur George; born 14 November 1948) is King of the United Kingdom and the 14 other Commonwealth realms.

Charles was born at Buckingham Palace during the reign of his maternal grandfather, King George VI, and ...

and then President Mohammad Khatami

Mohammad Khatami (born 14 October 1943) is an Iranian politician and Shia cleric who served as the fifth president of Iran from 3 August 1997 to 3 August 2005. He also served as Iran's Minister of Culture from 1982 to 1992. Later, he was critic ...

visited the city.

On 28 November 2011 Iran downgraded its relations with Britain due to new sanctions put in place by the UK. The next day a band of students and Basiji attacked the UK embassy compound in Tehran, damaging property and driving the embassy staff away. On 30 November 2011, in response to the attack, the UK closed its embassy in Tehran and ordered the Iranian embassy in London closed.

According to a 2013 BBC

The British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) is a British public service broadcaster headquartered at Broadcasting House in London, England. Originally established in 1922 as the British Broadcasting Company, it evolved into its current sta ...

World Service poll, only 5% of British people view Iran's influence positively, with 84% expressing a negative view. According to a 2012 Pew Global Attitudes Survey, 16% of British people viewed Iran favorably, compared to 68% which viewed it unfavorably; 91% of British people oppose Iranian acquisition of nuclear weapons

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either nuclear fission, fission (fission or atomic bomb) or a combination of fission and nuclear fusion, fusion reactions (thermonuclear weap ...

and 79% approve of "tougher sanctions" on Iran, while 51% of British people support use of military force to prevent Iran from developing nuclear weapons.

From July 2012 until October 2013, British interests in Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran (IRI) and also known as Persia, is a country in West Asia. It borders Iraq to the west, Turkey, Azerbaijan, and Armenia to the northwest, the Caspian Sea to the north, Turkmenistan to the nort ...

were maintained by the Swedish embassy in Tehran

Tehran (; , ''Tehrân'') is the capital and largest city of Iran. It is the capital of Tehran province, and the administrative center for Tehran County and its Central District (Tehran County), Central District. With a population of around 9. ...

while Iranian

Iranian () may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to Iran

** Iranian diaspora, Iranians living outside Iran

** Iranian architecture, architecture of Iran and parts of the rest of West Asia

** Iranian cuisine, cooking traditions and practic ...

interests in the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Northwestern Europe, off the coast of European mainland, the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

were maintained by the Omani embassy in London

London is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of both England and the United Kingdom, with a population of in . London metropolitan area, Its wider metropolitan area is the largest in Wester ...

.

In July 2013, it was announced that the UK would consider opening better relations with Iran "step-by-step" following the election

An election is a formal group decision-making process whereby a population chooses an individual or multiple individuals to hold Public administration, public office.

Elections have been the usual mechanism by which modern representative d ...

of President Hassan Rouhani

Hassan Rouhani (; born Hassan Fereydoun, 12 November 1948) is an Iranian peoples, Iranian politician who served as the seventh president of Iran from 2013 to 2021. He is also a sharia lawyer ("Wakil"), academic, former diplomat and Islamic cl ...

.

On October 8, 2013, Britain and Iran announced that they would each appoint a chargé d'affaires

A (), plural ''chargés d'affaires'', often shortened to ''chargé'' (French) and sometimes in colloquial English to ''charge-D'', is a diplomat who serves as an embassy's chief of mission in the absence of the ambassador. The term is Frenc ...

to work toward resuming full diplomatic relations.

On February 20, 2014, the Iranian Embassy in London was restored and the two countries agreed to restart diplomatic relations. On August 23, 2015, the British Embassy in Tehran officially reopened.

Trade

The first Persian Ambassador to the United Kingdom was Mirza Albohassan Khan Ilchi Kabir. The '' Herald Tribune'' on 22 January 2006 reported a rise in British exports to Iran from £296 million in 2000 to £443.8 million in 2004. A spokesperson for ''UK Trade and Investment'' was quoted saying that "Iran has become more attractive because it now pursues a more liberal economic policy". As of 2009, the total assets frozen inBritain

Britain most often refers to:

* Great Britain, a large island comprising the countries of England, Scotland and Wales

* The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, a sovereign state in Europe comprising Great Britain and the north-eas ...

under the EU (European Union) and UN sanctions against Iran

There have been a number of international sanctions against Iran imposed by a number of countries, especially the United States, and international entities. Iran was the most sanctioned country in the world until it was surpassed by Russia, follo ...

are approximately £976m ($1.64 billion). In November 2011, Britain severed all ties with Iranian banks as part of a package of sanctions from the US, UK and Canada aimed at confronting Tehran's nuclear programme.

Political tension

The confrontation between theUnited States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

–European Union

The European Union (EU) is a supranational union, supranational political union, political and economic union of Member state of the European Union, member states that are Geography of the European Union, located primarily in Europe. The u ...

pact on one side and Iran on the other over Iran's nuclear program

The Nuclear technology, nuclear program of Iran is one of the most scrutinized nuclear programs in the world. The military capabilities of the program are possible through its mass Enriched uranium, enrichment activities in facilities such a ...

also continues to develop, remaining a serious obstacle in the improvement of Tehran

Tehran (; , ''Tehrân'') is the capital and largest city of Iran. It is the capital of Tehran province, and the administrative center for Tehran County and its Central District (Tehran County), Central District. With a population of around 9. ...

–London

London is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of both England and the United Kingdom, with a population of in . London metropolitan area, Its wider metropolitan area is the largest in Wester ...

ties.

A confidential letter by UK diplomat John Sawers to French, German and US diplomats, dated 16 March 2006, twice referred to the intention to have the United Nations Security Council

The United Nations Security Council (UNSC) is one of the six principal organs of the United Nations (UN) and is charged with ensuring international peace and security, recommending the admission of new UN members to the General Assembly, an ...

refer to Chapter VII of the United Nations Charter

The Charter of the United Nations is the foundational treaty of the United Nations (UN). It establishes the purposes, governing structure, and overall framework of the United Nations System, UN system, including its United Nations System#Six ...

in order to put pressure on Iran. Chapter VII describes the Security Council's power to authorize economic, diplomatic, and military sanctions, as well as the use of military force, to resolve disputes.

The ''Sunday Telegraph

''The Sunday Telegraph'' is a British broadsheet newspaper, first published on 5 February 1961 and published by the Telegraph Media Group, a division of Press Holdings. It is the sister paper of ''The Daily Telegraph

''The Daily Telegr ...

'' reported that a secret, high-level meeting would take place on 3 April 2006 between the UK government and military chiefs regarding plans to attack Iran.Government in secret talks about strike against IranSean Rayment, ''

Sunday Telegraph

''The Sunday Telegraph'' is a British broadsheet newspaper, first published on 5 February 1961 and published by the Telegraph Media Group, a division of Press Holdings. It is the sister paper of ''The Daily Telegraph

''The Daily Telegr ...

'', 2 April 2006 The Telegraph cited "a senior Foreign Office source" saying that "The belief in some areas of Whitehall is that an attack is now all but inevitable. There will be no invasion of Iran but the nuclear sites will be destroyed." The BBC

The British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) is a British public service broadcaster headquartered at Broadcasting House in London, England. Originally established in 1922 as the British Broadcasting Company, it evolved into its current sta ...

reported a denial that the meeting would take place, but no denial of the alleged themes of the meeting, by the UK Ministry of Defence, and that "there is well sourced and persistent speculation that American covert activities aimed at Iran are already underway".MoD denies Iran military meetingBBC

The British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) is a British public service broadcaster headquartered at Broadcasting House in London, England. Originally established in 1922 as the British Broadcasting Company, it evolved into its current sta ...

, 2 April 2006

2004 Iranian seizure of Royal Navy personnel

On 21 June 2004, eight sailors and Royal Marines were seized by forces of the Revolutionary Guards' Navy while training Iraqi river patrol personnel in thePersian Gulf

The Persian Gulf, sometimes called the Arabian Gulf, is a Mediterranean seas, mediterranean sea in West Asia. The body of water is an extension of the Arabian Sea and the larger Indian Ocean located between Iran and the Arabian Peninsula.Un ...

.

2007 Iranian seizure of Royal Navy personnel

On 23 March 2007 fifteen Royal Navy personnel were seized by the naval forces of the Iranian Revolutionary Guard for allegedly having strayed into Iranian waters. Eight sailors and seven Royal Marines on two boats from HMS ''Cornwall'' were detained at 10:30 local time by six Guard boats of the IRGC Navy. They were subsequently taken to Tehran. Iran reported that the sailors are well. About 200 students targeted the British Embassy on 1 April 2007 calling for the expulsion of the country's ambassador because of the standoff over Iran's capture of 15 British sailors and marines. The protesters chanted "Death to Britain" and "Death to America

"Death to America" is an anti-American political slogan widely used in Iran,Arash KaramiKhomeini Orders Media to End 'Death to America' Chant, Iran Pulse, October 13, 2013 Afghanistan, Lebanon, Yemen, Iraq, and Pakistan. Ruhollah Khomeini, the f ...

".Protest in Iran targets British EmbassyChina Daily

''China Daily'' ( zh, s=中国日报, p=Zhōngguó Rìbào) is an English-language daily newspaper owned by the Central Propaganda Department of the Chinese Communist Party.

Overview

''China Daily'' has the widest print circulation of any ...

, 1 April 2007 Speculation on the Iranians' motivations for this action ran rampant; with the Iranians under tremendous pressure on a number of fronts from the United States, the Revolutionary Guard Corps

The Libyan Revolutionary Guard Corps (''Liwa Haris al-Jamahiriya''), also known as the Jamahiriyyah Guard, was a paramilitary elite unit that played the role of key protection force of the regime of Muammar Gaddafi, until his death in October 2 ...

could have been responding to any one of a number of perceived threats.

On 3 April 2007, Prime Minister

A prime minister or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. A prime minister is not the head of state, but r ...

Tony Blair

Sir Anthony Charles Lynton Blair (born 6 May 1953) is a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1997 to 2007 and Leader of the Labour Party (UK), Leader of the Labour Party from 1994 to 2007. He was Leader ...

advised that "the next 48 hours will be critical" in defusing the crisis. At approximately 1:20 PM GMT, Iran's president announced that the 8 sailors would be 'pardoned'. The following day, he announced all 15 British personnel would be released immediately "in celebration of the Prophet's birthday and Easter."

2007 Nuclear policy disagreements

On March 18, 2007,Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran (IRI) and also known as Persia, is a country in West Asia. It borders Iraq to the west, Turkey, Azerbaijan, and Armenia to the northwest, the Caspian Sea to the north, Turkmenistan to the nort ...

, under fire from Western powers over its atomic program, criticized Britain's plans to renew its nuclear arsenal as a "serious setback" to international disarmament

Disarmament is the act of reducing, limiting, or abolishing Weapon, weapons. Disarmament generally refers to a country's military or specific type of weaponry. Disarmament is often taken to mean total elimination of weapons of mass destruction, ...

efforts. Britain's parliament backed Prime Minister Tony Blair

Sir Anthony Charles Lynton Blair (born 6 May 1953) is a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1997 to 2007 and Leader of the Labour Party (UK), Leader of the Labour Party from 1994 to 2007. He was Leader ...

's plans to renew the country's Trident missile nuclear weapons system.

"Britain does not have the right to question others when they're not complying with their obligations" referring to the obligation by the U.K., United States, Russia and France to disarm under the NPT accord and "It is very unfortunate that the UK, which is always calling for non-proliferation not only has not given up the weapons but has taken a serious step toward further development of nuclear weapons

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either nuclear fission, fission (fission or atomic bomb) or a combination of fission and nuclear fusion, fusion reactions (thermonuclear weap ...

," Iran's envoy to the International Atomic Energy Agency

The International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) is an intergovernmental organization that seeks to promote the peaceful use of nuclear technology, nuclear energy and to inhibit its use for any military purpose, including nuclear weapons. It was ...

, told a conference examining the Trident decision.

Arms sales

Despite the political pressure and sanctions, a probe by customs officers suggests that at least seven British arms dealers have been supplying the Iranian air force, its elite Revolutionary Guard Corps, and the country's controversial nuclear ambitions. A UK businessman was caught smuggling components for use in guided missiles through a front company that proved to be the Iranian Ministry of Defence. Another case involves a group that included several Britons which, investigators alleged, attempted to export components intended to enhance the performance of Iranian aircraft. Other examples involve a British millionaire arms dealer caught trading machine-guns used by the SAS and capable of firing 800 rounds a minute with a Tehran-based weapons supplier.Gholhak Garden

In 2006 a dispute about the ownership of Gholhak Garden, a large British diplomatic compound in northern Tehran was raised in the Iranian Parliament when 162 MPs wrote to the speaker. The British Embassy have occupied the site since at least 1934 and assert that they have legal ownership but the issue was raised again in 2007 when a group of MPs claimed that the ownership papers for the site were unlawful under the laws extant in 1934. In July 2007 a conference was held to discuss the ownership of the compound but was not attended by the British side.Asylum

On 14 March 2008, Britain said it would reconsider the asylum application of a gay Iranian teenager who claims he will be persecuted if he is returned home. He had fled to theNetherlands

, Terminology of the Low Countries, informally Holland, is a country in Northwestern Europe, with Caribbean Netherlands, overseas territories in the Caribbean. It is the largest of the four constituent countries of the Kingdom of the Nether ...

and sought asylum there; however, the Dutch government turned him down, saying the case should be dealt with in Britain, where he first applied.

Escalating war talk

As talk of strikes and counter-strikes in relation to war talk between the United States-Israel-Iran trio heated up in 2008, a senior Iranian official suggested his regime should target London to deter such an attack. The head of the Europe and US Department in the Iranian Foreign Ministry, Wahid Karimi, said an attack on London could deter the US from attacking Tehran. He said: "The most appropriate means of deterrence that Iran has, in addition to a retaliatory operation in the ersian Gulfregion, is to take action against London." He also suggested a propensity to attack could arise from a "usually adventuresome" second term presidency. He said: "US presidents are usually adventuresome in their second terms... ichardNixon, disgraced by the Watergate scandal; onaldReagan, with the 'Irangate' adventure; nd BillClinton, with Monica Lewinsky—and perhaps George Bush, the sitting president, will create a scandal connected to Iran's legitimate nuclear activity so as not to be left behind." His speculation led him to suggest a clash could occur between the 2008 U.S. presidential elections and by the time the new president enters office in January 2009. "In the worst-case scenario, George Bush may perhaps persuade the president-elect to carry out an ill-conceived operation against Iran, prior to January 20, 2009—that is, before the regime is handed over and he ends his presence in the White House. The next president of the US will have to deal with the consequences."2009 Iranian election controversy

In the aftermath of the disputed 2009 Iranian presidential election and the protests that followed, UK-Iran relations were further tested. On 19 June 2009, theSupreme Leader of Iran

The supreme leader of Iran, also referred to as the supreme leader of the Islamic Revolution, but officially called the supreme leadership authority, is the head of state and the highest political and religious authority of Iran (above the Presi ...

Ayatollah Khamenei described the British Government

His Majesty's Government, abbreviated to HM Government or otherwise UK Government, is the central government, central executive authority of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland.

as the "most evil" of those in the Western nations, accusing the British government of sending spies into Iran to stir emotions at the time of the elections, although it has been suggested by British diplomats that the statement was using the UK as a " proxy" for the United States, in order to prevent damaging US–Iranian relations. Nonetheless, the British Government, unhappy at the statement, summoned the Iranian ambassador

An ambassador is an official envoy, especially a high-ranking diplomat who represents a state and is usually accredited to another sovereign state or to an international organization as the resident representative of their own government or so ...

Rasul Movaheddian to the Foreign Office

Foreign may refer to:

Government

* Foreign policy, how a country interacts with other countries

* Ministry of Foreign Affairs, in many countries

** Foreign Office, a department of the UK government

** Foreign office and foreign minister

* United ...

to lodge a protest. Iran then proceeded to expel two British diplomats

A diplomat (from ; romanized ''diploma'') is a person appointed by a state, intergovernmental, or nongovernmental institution to conduct diplomacy with one or more other states or international organizations.

The main functions of diplomats a ...

from the country, accusing them of "activities inconsistent with their diplomatic status". On 23 June 2009, the British Government responded, expelling two Iranian diplomats from the United Kingdom. Prime Minister

A prime minister or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. A prime minister is not the head of state, but r ...

Gordon Brown

James Gordon Brown (born 20 February 1951) is a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and Leader of the Labour Party (UK), Leader of the Labour Party from 2007 to 2010. Previously, he was Chancellor of the Ex ...

stated that he was unhappy at having to take the action, but suggested there was no option after what he described as 'unjustified' actions by Iran. On 24 June 2009, Iranian Foreign Minister Manouchehr Mottaki announced that the country was considering 'downgrading' its ties with the UK.

Four days later it was reported that Iranian authorities had arrested a number of British embassy staff in Tehran citing their "considerable role" in the recent unrest. After this event, the UK Government responded strongly demanding that the Iranian authorities release the British staff immediately as it stated that Iran's accusations are baseless without evidence. After the arrest of UK staff, the European Union

The European Union (EU) is a supranational union, supranational political union, political and economic union of Member state of the European Union, member states that are Geography of the European Union, located primarily in Europe. The u ...

(EU) has also demanded that UK staff be released in Iran under international law and if the UK staff are not released then the EU threatens a 'strong response'. On December 29, 2009, Britain was warned by Iranian Foreign Minister Manouchehr Mottaki to state "Britain will get slapped in the mouth if it does not stop its nonsense."

The Queen's College, Oxford

The Queen's College is a constituent college of the University of Oxford, England. The college was founded in 1341 by Robert de Eglesfield in honour of Philippa of Hainault, queen of England. It is distinguished by its predominantly neoclassi ...

established the Neda Agha-Soltan Graduate Scholarship in 2009, named after Neda Agha-Soltan

Neda Agha-Soltan ( – ''Nedā Āghā-Soltān''; 23 January 1983 – 20 June 2009) was an Iranian student of philosophy, who was participating in the 2009 Iranian presidential election protests, 2009 presidential election protests with ...

, who died in the protests that followed the election. This led to a letter of protest to the college from the Iranian embassy in London, signed by the deputy ambassador, Safarali Eslamian. The letter disputed the circumstances of her death, and said that there was "supporting evidence indicating a pre-made scenario". Eslamain wrote, "It seems that the University of Oxford has stepped up involvement in a politically motivated campaign which is not only in sharp contract with its academic objectives, but also is linked with a chain of events in post-Iranian presidential elections blamed for British interference both at home and abroad". The letter also said that the "decision to abuse Neda's case to establish a graduate scholarship will highly politicise your academic institution, undermining your scientific credibility—along with British press which made exceptionally a lot of hue and cry on Neda's death—will make Oxford at odd with the rest of the world's academic institutions." Eslamain asked for the university's governing board to be informed of "the Iranian views", and finished by saying, "Surely, your steps to achieve your attractions through non-politically supported programs can better heal the wounds of her family and her nation." Following publication of the Iranian letter, ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British Newspaper#Daily, daily Newspaper#National, national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its modern name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its si ...

'' was told by UK diplomatic sources, speaking anonymously, that the scholarship had put "another nail into the coffin" of relations between Britain and Iran. If the government had been asked, the sources were reported as saying, it would have advised against the move, because it was felt that Iran would see it as an act of provocation, and because it would interfere with efforts to free Iranians working for the British Embassy in Tehran who had been detained for alleging participating in the post-election protests. A college spokesman said that the scholarship had not been set up as part of a political decision, and if the initial donations had been refused, this would have been interpreted as a political decision too.

2009 international arbitration court ruling

In April 2009 the British government lost its final appeal in the arbitration court of theInternational Chamber of Commerce

The International Chamber of Commerce (ICC; French: ''Chambre de commerce internationale'') is the largest, most representative business organization in the world. ICC represents over 45 million businesses in over 170 countries who have interest ...

at The Hague

The Hague ( ) is the capital city of the South Holland province of the Netherlands. With a population of over half a million, it is the third-largest city in the Netherlands. Situated on the west coast facing the North Sea, The Hague is the c ...

against a payment of $650 million to Iran. The money is compensation for an arms deal dating from the 1970s which then did not come about due to the occurrence of the Iranian Revolution

The Iranian Revolution (, ), also known as the 1979 Revolution, or the Islamic Revolution of 1979 (, ) was a series of events that culminated in the overthrow of the Pahlavi dynasty in 1979. The revolution led to the replacement of the Impe ...

. The Shah's government had ordered 1,500 Chieftain tank

The FV4201 Chieftain was the primary main battle tank (MBT) of the United Kingdom from the 1960s into 1990s. Introduced in 1967, it was among the most heavily armed MBTs at the time, mounting a 120 mm Royal Ordnance L11 gun, equivalent to t ...

s and 250 Chieftain armoured recovery vehicle

An armoured recovery vehicle (ARV) is typically a powerful tank or armoured personnel carrier (APC) chassis modified for use during combat for military vehicle recovery (towing) or repair of battle-damaged, stuck, and/or inoperable armoured f ...

s (ARVs) in a contract worth £650 million, but only 185 vehicles had been delivered before the revolution occurred. The contract also covered the provision of training to the Iranian army and the construction of a factory near Isfahan

Isfahan or Esfahan ( ) is a city in the Central District (Isfahan County), Central District of Isfahan County, Isfahan province, Iran. It is the capital of the province, the county, and the district. It is located south of Tehran. The city ...

to build tank parts and ammunition. In order to recover some of the costs 279 of the Chieftains were sold to Jordan

Jordan, officially the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan, is a country in the Southern Levant region of West Asia. Jordan is bordered by Syria to the north, Iraq to the east, Saudi Arabia to the south, and Israel and the occupied Palestinian ter ...

and 29 of the ARVs to Iraq

Iraq, officially the Republic of Iraq, is a country in West Asia. It is bordered by Saudi Arabia to Iraq–Saudi Arabia border, the south, Turkey to Iraq–Turkey border, the north, Iran to Iran–Iraq border, the east, the Persian Gulf and ...

, who used them against Iran in the Iran–Iraq War

The Iran–Iraq War, also known as the First Gulf War, was an armed conflict between Iran and Iraq that lasted from September 1980 to August 1988. Active hostilities began with the Iraqi invasion of Iran and lasted for nearly eight years, unti ...

. The UK continued to deliver tank parts to Iran after the revolution but finally stopped following the outbreak of the Iranian hostage crisis in 1979.

The British government has itself confirmed it has to pay the money and the ruling, which originated in The Hague

The Hague ( ) is the capital city of the South Holland province of the Netherlands. With a population of over half a million, it is the third-largest city in the Netherlands. Situated on the west coast facing the North Sea, The Hague is the c ...

, received coverage in ''The Independent

''The Independent'' is a British online newspaper. It was established in 1986 as a national morning printed paper. Nicknamed the ''Indy'', it began as a broadsheet and changed to tabloid format in 2003. The last printed edition was publis ...

''. Britain had already placed £486 million with the court in 2002 to pay for any ruling against it. The settlement is worth £390 million that will come out of this fund. Iran has yet to officially apply to receive the money but when it does so will not receive it, instead it will join £976 million of Iranian assets frozen by the UK due to EU sanctions.

2011 attack on the British Embassy

On 29 November 2011, despite heavy police resistance, two compounds of the British embassy in Tehran were stormed by Iranian protesters. The protesters smashed windows, ransacked offices, set fire to government documents, and burned a British flag. Six British diplomats were initially reported by the Iranian semi-official news agency Mehr as being taken hostage, while later reports indicated that in fact they were escorted to safety by the police. The storming of the British embassy followed from the 2011 joint American-British-Canadian sanctions and the Iranian government'sGuardian Council

The Guardian Council (also called Council of Guardians or Constitutional Council, ) is an appointed and constitutionally mandated 12-member council that wields considerable power and influence in the Islamic Republic of Iran.

The constitution ...

approving a parliamentary bill expelling the British ambassador as a result of those sanctions. A British flag

The national flag of the United Kingdom is the Union Jack, also known as the Union Flag.

The design of the Union Jack dates back to the Act of Union 1801, which united the Kingdom of Great Britain and the Kingdom of Ireland (previously in p ...

was taken down and replaced by the Iranian flag by the protesters. The British Foreign Office

The Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) is the ministry of foreign affairs and a ministerial department of the government of the United Kingdom.

The office was created on 2 September 2020 through the merger of the Foreign an ...

responded by saying "We are outraged by this. It is utterly unacceptable and we condemn it." According to Iranian state news agencies, the protesters were largely composed of young adults. On 30 November William Hague

William Jefferson Hague, Baron Hague of Richmond (born 26 March 1961) is a British politician and life peer who was Leader of the Conservative Party and Leader of the Opposition from 1997 to 2001 and Deputy Leader from 2005 to 2010. He was th ...

announced that all Iranian diplomats had been expelled and given 48 hours to leave the United Kingdom.

Since 2011

The UK Defence SecretaryPhilip Hammond

Philip Hammond, Baron Hammond of Runnymede (born 4 December 1955) is a British politician and life peer who served as Chancellor of the Exchequer from 2016 to 2019 and Foreign Secretary from 2014 to 2016, having previously served as Defence ...

warned that Britain might take military action against Iran if it carries out its threat to block the Strait of Hormuz

The Strait of Hormuz ( ''Tangeh-ye Hormoz'' , ''Maḍīq Hurmuz'') is a strait between the Persian Gulf and the Gulf of Oman. It provides the only sea passage from the Persian Gulf to the open ocean and is one of the world's most strategica ...

. He said any attempt by Iran to block the strategically important waterway in retaliation for sanctions against its oil exports would be "illegal and unsuccessful" and the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

would join any action to keep it open. British defence officials met US Secretary of Defense

The United States secretary of defense (acronym: SecDef) is the head of the United States Department of Defense (DoD), the executive department of the U.S. Armed Forces, and is a high-ranking member of the federal cabinet. DoDD 5100.1: Enclos ...

Leon Panetta

Leon Edward Panetta (born June 28, 1938) is an American retired politician and government official who has served under several Democratic administrations as secretary of defense (2011–2013), director of the CIA (2009–2011), White House chi ...

on 6 January to criticize other members of the NATO

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO ; , OTAN), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental organization, intergovernmental Transnationalism, transnational military alliance of 32 Member states of NATO, member s ...

for not being willing to commit resources to joint operations, including in Libya

Libya, officially the State of Libya, is a country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It borders the Mediterranean Sea to the north, Egypt to Egypt–Libya border, the east, Sudan to Libya–Sudan border, the southeast, Chad to Chad–L ...

and Afghanistan

Afghanistan, officially the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan, is a landlocked country located at the crossroads of Central Asia and South Asia. It is bordered by Pakistan to the Durand Line, east and south, Iran to the Afghanistan–Iran borde ...

. The following day, UK officials reported its intention to send its most powerful naval forces to the Persian Gulf

The Persian Gulf, sometimes called the Arabian Gulf, is a Mediterranean seas, mediterranean sea in West Asia. The body of water is an extension of the Arabian Sea and the larger Indian Ocean located between Iran and the Arabian Peninsula.Un ...

to counter any Iranian attempt to close the Strait of Hormuz

The Strait of Hormuz ( ''Tangeh-ye Hormoz'' , ''Maḍīq Hurmuz'') is a strait between the Persian Gulf and the Gulf of Oman. It provides the only sea passage from the Persian Gulf to the open ocean and is one of the world's most strategica ...

. The Type 45 destroyer would arrive in the Gulf by the end of January. According to officials, the ship is capable of shooting down "any missile in Iran's armoury."

In July 2013, the UK considered opening better relations with Iran "step-by-step" following the

In July 2013, the UK considered opening better relations with Iran "step-by-step" following the election

An election is a formal group decision-making process whereby a population chooses an individual or multiple individuals to hold Public administration, public office.

Elections have been the usual mechanism by which modern representative d ...

of President Hassan Rouhani

Hassan Rouhani (; born Hassan Fereydoun, 12 November 1948) is an Iranian peoples, Iranian politician who served as the seventh president of Iran from 2013 to 2021. He is also a sharia lawyer ("Wakil"), academic, former diplomat and Islamic cl ...

, and in October of the same year, both countries announced that they would each appoint a chargé d'affaires

A (), plural ''chargés d'affaires'', often shortened to ''chargé'' (French) and sometimes in colloquial English to ''charge-D'', is a diplomat who serves as an embassy's chief of mission in the absence of the ambassador. The term is Frenc ...

to work toward resuming full diplomatic relations. This was done on 20 February 2014, and the British government announced in June 2014 that it would soon re-open its Tehran embassy. Embassies in each other's countries were simultaneously reopened in 2015. The ceremony in Tehran was attended by UK Foreign Secretary Philip Hammond

Philip Hammond, Baron Hammond of Runnymede (born 4 December 1955) is a British politician and life peer who served as Chancellor of the Exchequer from 2016 to 2019 and Foreign Secretary from 2014 to 2016, having previously served as Defence ...

, the first British Foreign Secretary to visit Iran since Jack Straw in 2003, who attended the reopening of the Iranian embassy in London, along with Iran's deputy foreign minister Mehdi Danesh Yazdi. Diplomat Ajay Sharma was named as the UK's charge d'affaires but a full ambassador was expected to be appointed in the coming months. In September 2016, both countries restored diplomatic relations to their pre-2011 level, with Nicholas Hopton being appointed British Ambassador in Tehran.

British prime minister David Cameron

David William Donald Cameron, Baron Cameron of Chipping Norton (born 9 October 1966) is a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 2010 to 2016. Until 2015, he led the first coalition government in the UK s ...

and Iranian President Hassan Rouhani

Hassan Rouhani (; born Hassan Fereydoun, 12 November 1948) is an Iranian peoples, Iranian politician who served as the seventh president of Iran from 2013 to 2021. He is also a sharia lawyer ("Wakil"), academic, former diplomat and Islamic cl ...

met on the sidelines of a United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is the Earth, global intergovernmental organization established by the signing of the Charter of the United Nations, UN Charter on 26 June 1945 with the stated purpose of maintaining international peace and internationa ...

in September 2014, marking the highest-level direct contact between the two countries since the 1979 Islamic revolution.

In April 2016, an Iranian-British dual citizen Nazanin Zaghari-Ratcliffe was arrested while visiting Iran with her daughter. She was found guilty of "plotting to topple the Iranian government" in September 2016 and sentenced to 5 years in prison. Her husband led a concerted campaign to have her released maintaining that she "was imprisoned as leverage for a debt owed by the UK over its failure to deliver tanks to Iran in 1979." After her initial sentence expired in March 2021 she was charged and found guilty of propaganda activities against the government and sentenced to one year in prison. She was finally released on 16 March 2022, which was reported to be related to the UK paying a historic debt for tanks paid for by Iran in the 1970s but never delivered.

Theresa May

Theresa Mary May, Baroness May of Maidenhead (; ; born 1 October 1956), is a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and Leader of the Conservative Party from 2016 to 2019. She previously served as Home Secretar ...

, who succeeded Cameron as prime minister in July 2016, accused Iran of "aggressive regional actions" in the Middle East, including stirring trouble in Iraq, Lebanon and Syria, and this led to a deterioration in relations In response, Iran's Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei

Ali Hosseini Khamenei (; born 19 April 1939) is an Iranian cleric and politician who has served as the second supreme leader of Iran since 1989. He previously served as the third President of Iran, president from 1981 to 1989. Khamenei's tenure ...

condemned Britain as a "source of evil and misery" for the Middle East.

The British intelligence officials concluded that Iran was responsible for a cyberattack

A cyberattack (or cyber attack) occurs when there is an unauthorized action against computer infrastructure that compromises the confidentiality, integrity, or availability of its content.

The rising dependence on increasingly complex and inte ...

on the British Parliament

The Parliament of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland is the supreme legislative body of the United Kingdom, and may also legislate for the Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories. It meets at the Palace of ...

lasting 12 hours that compromised around 90 email accounts of MPs in June 2017.

On 7 July 2022, The Royal Navy of Britain reported that one of its warships had arrested smugglers in international waters south of Iran early this year after seizing Iranian armaments, including surface-to-air missiles and cruise missile engines.

On 28 November 2024, former British soldier, Daniel Khalife was found guilty of spying for Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran (IRI) and also known as Persia, is a country in West Asia. It borders Iraq to the west, Turkey, Azerbaijan, and Armenia to the northwest, the Caspian Sea to the north, Turkmenistan to the nort ...

. His first known contact with Iranian intelligence occurred in September 2018, soon after he joined the military. He also contacted a man linked to the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps

The Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), also known as the Iranian Revolutionary Guards, is a multi-service primary branch of the Islamic Republic of Iran Armed Forces, Iranian Armed Forces. It was officially established by Ruhollah Khom ...

(IRGC) via Facebook

Facebook is a social media and social networking service owned by the American technology conglomerate Meta Platforms, Meta. Created in 2004 by Mark Zuckerberg with four other Harvard College students and roommates, Eduardo Saverin, Andre ...

and further built relationships with other Iranian contacts. During his military service, Khalife photographed a list containing the names of 15 soldiers, including some members of the elite Special Air Service

The Special Air Service (SAS) is a special forces unit of the British Army. It was founded as a regiment in 1941 by David Stirling, and in 1950 it was reconstituted as a corps. The unit specialises in a number of roles including counter-terr ...

(SAS) and Special Boat Service

The Special Boat Service (SBS) is the special forces unit of the United Kingdom's Royal Navy. The SBS can trace its origins back to the Second World War when the Army Special Boat Section was formed in 1940. After the Second World War, the Roy ...

(SBS); it is believed that he sent the list to his Iranian contacts and later deleted the correspondence. He also collected a "very large body of restricted and classified

Classified may refer to:

General

*Classified information, material that a government body deems to be sensitive

*Classified advertising or "classifieds"

Music

*Classified (rapper) (born 1977), Canadian rapper

* The Classified, a 1980s American ro ...

material" and appears to have sent Iran at least two classified documents, one of which containing information on drones, the other on "Intelligence

Intelligence has been defined in many ways: the capacity for abstraction, logic, understanding, self-awareness, learning, emotional knowledge, reasoning, planning, creativity, critical thinking, and problem-solving. It can be described as t ...

, Surveillance

Surveillance is the monitoring of behavior, many activities, or information for the purpose of information gathering, influencing, managing, or directing. This can include observation from a distance by means of electronic equipment, such as ...

& Reconnaissance

In military operations, military reconnaissance () or scouting is the exploration of an area by military forces to obtain information about enemy forces, the terrain, and civil activities in the area of operations. In military jargon, reconnai ...

". One forged document Khalife sent to the Iranians stated that the British government

His Majesty's Government, abbreviated to HM Government or otherwise UK Government, is the central government, central executive authority of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland.

refused to negotiate the release of Nazanin Zaghari-Ratcliffe, thereby putting her in danger.

Tanker detention and Strait of Hormuz tensions

On 4 July 2019, Royal Marines boarded the Iranian-owned tanker ''Grace 1'' by helicopter offGibraltar

Gibraltar ( , ) is a British Overseas Territories, British Overseas Territory and British overseas cities, city located at the southern tip of the Iberian Peninsula, on the Bay of Gibraltar, near the exit of the Mediterranean Sea into the A ...

where it was detained. The reason given was to enforce European Union

The European Union (EU) is a supranational union, supranational political union, political and economic union of Member state of the European Union, member states that are Geography of the European Union, located primarily in Europe. The u ...

sanctions against Syria

Syria, officially the Syrian Arab Republic, is a country in West Asia located in the Eastern Mediterranean and the Levant. It borders the Mediterranean Sea to the west, Turkey to Syria–Turkey border, the north, Iraq to Iraq–Syria border, t ...

n entities, as the tanker was suspected of heading to Baniyas Refinery named in the sanctions that concern Syrian oil exports. Gibraltar had passed regulations permitting the detention the day before. Spain's foreign minister Josep Borrell

Josep Borrell Fontelles (; born 24 April 1947) is a Spanish politician who served as High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy and Vice-President of the European Commission from 2019 to 2024. A member of the Spani ...

stated that the detention was carried out at the request of the United States. An Iranian Foreign Ministry official called the seizure "piracy," stating that the UK does not have the right to implement sanctions against other nations "in an extraterritorial manner".

On 10 July 2019, tensions were raised further when boats belonging to Iran's Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps

The Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), also known as the Iranian Revolutionary Guards, is a multi-service primary branch of the Islamic Republic of Iran Armed Forces, Iranian Armed Forces. It was officially established by Ruhollah Khom ...

approached a British Petroleum

BP p.l.c. (formerly The British Petroleum Company p.l.c. and BP Amoco p.l.c.; stylised in all lowercase) is a British multinational oil and gas company headquartered in London, England. It is one of the oil and gas " supermajors" and one of ...

tanker, ''British Heritage'', impeding it while it was transiting the Strait of Hormuz

The Strait of Hormuz ( ''Tangeh-ye Hormoz'' , ''Maḍīq Hurmuz'') is a strait between the Persian Gulf and the Gulf of Oman. It provides the only sea passage from the Persian Gulf to the open ocean and is one of the world's most strategica ...

. The Royal Navy frigate positioned themselves between the boats and ship so that it could continue its journey.

On 14 July 2019, British Foreign Secretary Jeremy Hunt

Sir Jeremy Richard Streynsham Hunt (born 1 November 1966) is a British politician who served as Chancellor of the Exchequer from 2022 to 2024 and Foreign Secretary from 2018 to 2019, having previously served as Secretary of State for Health a ...

said ''Grace 1'' could be released if the UK received guarantees the oil — 2.1 million barrels worth — would not go to Syria.

On 19 July 2019, Iran media reported that the Swedish owned but British-flagged oil tanker ''Stena Impero'' had been seized by the Iranian Revolutionary Guard in the Strait of Hormuz. A first tanker, MV ''Mesdar'', which was a Liberian-flagged vessel managed in the UK, jointly Algerian and Japanese owned, was boarded but later released. Iran stated that the British-flagged ship had collided with and damaged an Iranian vessel, and had ignored warnings by Iranian authorities. During the incident HMS ''Montrose'' was stationed too far away to offer timely assistance; when the

On 19 July 2019, Iran media reported that the Swedish owned but British-flagged oil tanker ''Stena Impero'' had been seized by the Iranian Revolutionary Guard in the Strait of Hormuz. A first tanker, MV ''Mesdar'', which was a Liberian-flagged vessel managed in the UK, jointly Algerian and Japanese owned, was boarded but later released. Iran stated that the British-flagged ship had collided with and damaged an Iranian vessel, and had ignored warnings by Iranian authorities. During the incident HMS ''Montrose'' was stationed too far away to offer timely assistance; when the Type 23 frigate

The Type 23 frigate or Duke class is a class of frigates built for the United Kingdom's Royal Navy. The ships are named after British Dukes, thus leading to the class being commonly known as the Duke class. The first Type 23, , was commission ...

arrived it was ten minutes too late. HMS ''Montrose'' was slated to be replaced by , however in light of events it was decided that both ships would subsequently be deployed together.

On 15 August 2019 Gibraltar released ''Grace 1'' after stating that it had received assurances she would not go to Syria. The Iranian government later stated that it had issued no assurances that the oil would not be delivered to Syria and reasserted its intention to continue supplying oil to the Arab nation. On 26 August, Iranian government spokesman Ali Rabiei announced that the 2.1 million barrels of crude had been sold to an unnamed buyer, in either Kalamata, Greece or Mersin, Turkey. A US court issued a warrant of seizure against the tanker because it was convinced that the tanker was owned by the IRGC

The Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), also known as the Iranian Revolutionary Guards, is a multi-service primary branch of the Iranian Armed Forces. It was officially established by Ruhollah Khomeini as a military branch in May 1979 i ...

, which is deemed by Washington a foreign terrorist organization.

On 15 August 2019 the UK's new Boris Johnson

Alexander Boris de Pfeffel Johnson (born 19 June 1964) is a British politician and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and Leader of the Conservative Party (UK), Leader of the Conservative Party from 2019 to 2022. He wa ...

-led government agreed to join the U.S. in its Persian Gulf

The Persian Gulf, sometimes called the Arabian Gulf, is a Mediterranean seas, mediterranean sea in West Asia. The body of water is an extension of the Arabian Sea and the larger Indian Ocean located between Iran and the Arabian Peninsula.Un ...