This article covers worldwide

diplomacy

Diplomacy is the communication by representatives of State (polity), state, International organization, intergovernmental, or Non-governmental organization, non-governmental institutions intended to influence events in the international syste ...

and, more generally, the

international relations

International relations (IR, and also referred to as international studies, international politics, or international affairs) is an academic discipline. In a broader sense, the study of IR, in addition to multilateral relations, concerns al ...

of the

great power

A great power is a sovereign state that is recognized as having the ability and expertise to exert its influence on a global scale. Great powers characteristically possess military and economic strength, as well as diplomatic and soft power ...

s from 1814 to 1919. This era covers the period from the end of the

Napoleonic Wars

{{Infobox military conflict

, conflict = Napoleonic Wars

, partof = the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars

, image = Napoleonic Wars (revision).jpg

, caption = Left to right, top to bottom:Battl ...

and the

Congress of Vienna

The Congress of Vienna of 1814–1815 was a series of international diplomatic meetings to discuss and agree upon a possible new layout of the European political and constitutional order after the downfall of the French Emperor Napoleon, Napol ...

(1814–1815), to the end of the

First World War

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

and the

Paris Peace Conference (1919–1920).

Important themes include the rapid industrialization and growing power of

Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the north-west coast of continental Europe, consisting of the countries England, Scotland, and Wales. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the List of European ...

, the

United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

,

France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

,

Prussia

Prussia (; ; Old Prussian: ''Prūsija'') was a Germans, German state centred on the North European Plain that originated from the 1525 secularization of the Prussia (region), Prussian part of the State of the Teutonic Order. For centuries, ...

/

Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

, and, later in the period,

Italy

Italy, officially the Italian Republic, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe, Western Europe. It consists of Italian Peninsula, a peninsula that extends into the Mediterranean Sea, with the Alps on its northern land b ...

and

Japan

Japan is an island country in East Asia. Located in the Pacific Ocean off the northeast coast of the Asia, Asian mainland, it is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan and extends from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north to the East China Sea ...

. This led to

imperialist

Imperialism is the maintaining and extending of power over foreign nations, particularly through expansionism, employing both hard power (military and economic power) and soft power ( diplomatic power and cultural imperialism). Imperialism fo ...

and

colonialist

Colonialism is the control of another territory, natural resources and people by a foreign group. Colonizers control the political and tribal power of the colonised territory. While frequently an Imperialism, imperialist project, colonialism c ...

competitions for influence and power throughout the world, most famously the

Scramble for Africa

The Scramble for Africa was the invasion, conquest, and colonialism, colonisation of most of Africa by seven Western European powers driven by the Second Industrial Revolution during the late 19th century and early 20th century in the era of ...

in the 1880s and 1890s; the reverberations of which are still widespread and consequential in the 21st century. Britain established an informal economic network that, combined with its

colonies

A colony is a territory subject to a form of foreign rule, which rules the territory and its indigenous peoples separated from the foreign rulers, the colonizer, and their '' metropole'' (or "mother country"). This separated rule was often or ...

and its

Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

, made it the hegemonic nation until its power was challenged by the united Germany. It was a largely peaceful century, with no wars between the great powers, apart from the 1853–1871 interval, and

some wars between Russia and the

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

. After 1900, there was a

series of wars in the Balkan region, which exploded out of control into World War I (1914–1918) — a massively devastating event that was unexpected in its timing, duration, casualties, and long-term impact.

In 1814, diplomats recognized five great powers: France, Britain,

Russia

Russia, or the Russian Federation, is a country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia. It is the list of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the world, and extends across Time in Russia, eleven time zones, sharing Borders ...

,

Austria

Austria, formally the Republic of Austria, is a landlocked country in Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine Federal states of Austria, states, of which the capital Vienna is the List of largest cities in Aust ...

(in 1867–1918,

Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, also referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Dual Monarchy or the Habsburg Monarchy, was a multi-national constitutional monarchy in Central Europe#Before World War I, Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. A military ...

) and Prussia (in 1871–1918, the German Empire). Italy was added to this group after its

unification in 1860 ("Risorgimento"); by 1905 two rapidly growing non-European states, Japan and the United States, had joined the great powers.

Romania

Romania is a country located at the crossroads of Central Europe, Central, Eastern Europe, Eastern and Southeast Europe. It borders Ukraine to the north and east, Hungary to the west, Serbia to the southwest, Bulgaria to the south, Moldova to ...

,

Bulgaria

Bulgaria, officially the Republic of Bulgaria, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern portion of the Balkans directly south of the Danube river and west of the Black Sea. Bulgaria is bordered by Greece and Turkey t ...

,

Serbia

, image_flag = Flag of Serbia.svg

, national_motto =

, image_coat = Coat of arms of Serbia.svg

, national_anthem = ()

, image_map =

, map_caption = Location of Serbia (gree ...

, and

Montenegro

, image_flag = Flag of Montenegro.svg

, image_coat = Coat of arms of Montenegro.svg

, coa_size = 80

, national_motto =

, national_anthem = ()

, image_map = Europe-Mont ...

initially operated as autonomous vassals, for until about 1908–1912 they were legally still part of the

declining Ottoman Empire, before gaining their independence.

In 1914, on the eve of the First World War, there were two major blocs in Europe: the

Triple Entente

The Triple Entente (from French meaning "friendship, understanding, agreement") describes the informal understanding between the Russian Empire, the French Third Republic, and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. It was built upon th ...

formed by France, Britain, and Russia and the

Triple Alliance formed by Germany, Austria-Hungary, and Italy. Italy stayed neutral and joined the Entente in 1915, while the

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

and

Bulgaria

Bulgaria, officially the Republic of Bulgaria, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern portion of the Balkans directly south of the Danube river and west of the Black Sea. Bulgaria is bordered by Greece and Turkey t ...

joined the Central Powers. Neutrality was the policy of

Belgium

Belgium, officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. Situated in a coastal lowland region known as the Low Countries, it is bordered by the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Luxembourg to the southeas ...

, the

Netherlands

, Terminology of the Low Countries, informally Holland, is a country in Northwestern Europe, with Caribbean Netherlands, overseas territories in the Caribbean. It is the largest of the four constituent countries of the Kingdom of the Nether ...

,

Luxembourg

Luxembourg, officially the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg, is a landlocked country in Western Europe. It is bordered by Belgium to the west and north, Germany to the east, and France on the south. Its capital and most populous city, Luxembour ...

,

Denmark

Denmark is a Nordic countries, Nordic country in Northern Europe. It is the metropole and most populous constituent of the Kingdom of Denmark,, . also known as the Danish Realm, a constitutionally unitary state that includes the Autonomous a ...

,

Sweden

Sweden, formally the Kingdom of Sweden, is a Nordic countries, Nordic country located on the Scandinavian Peninsula in Northern Europe. It borders Norway to the west and north, and Finland to the east. At , Sweden is the largest Nordic count ...

,

Norway

Norway, officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic countries, Nordic country located on the Scandinavian Peninsula in Northern Europe. The remote Arctic island of Jan Mayen and the archipelago of Svalbard also form part of the Kingdom of ...

,

Greece

Greece, officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. Located on the southern tip of the Balkan peninsula, it shares land borders with Albania to the northwest, North Macedonia and Bulgaria to the north, and Turkey to th ...

,

Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic, is a country on the Iberian Peninsula in Southwestern Europe. Featuring Cabo da Roca, the westernmost point in continental Europe, Portugal borders Spain to its north and east, with which it share ...

,

Spain

Spain, or the Kingdom of Spain, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe with territories in North Africa. Featuring the Punta de Tarifa, southernmost point of continental Europe, it is the largest country in Southern Eur ...

, and

Switzerland

Switzerland, officially the Swiss Confederation, is a landlocked country located in west-central Europe. It is bordered by Italy to the south, France to the west, Germany to the north, and Austria and Liechtenstein to the east. Switzerland ...

. The First World War unexpectedly pushed the great powers' military, diplomatic, social and economic capabilities to their limits. Germany, Austria–Hungary, the Ottoman Empire, and Bulgaria were defeated; Germany lost its great power status, Bulgaria lost more territory, and the others were broken up into collections of states. The winners Britain, France, Italy and Japan gained permanent seats at the governing council of the new

League of Nations

The League of Nations (LN or LoN; , SdN) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference (1919–1920), Paris Peace ...

. The United States, meant to be the fifth permanent member, decided to operate independently and never joined the League.

For the following periods, see

diplomatic history of World War I

The diplomatic history of World War I covers the non-military interactions among the major players during World War I. For the domestic histories of participants see home front during World War I. For a longer-term perspective see international re ...

and

international relations (1919–1939)

International relations (1919–1939) covers the main interactions shaping world history in this era, known as the interwar period, with emphasis on diplomacy and economic relations. The coverage here follows the diplomatic history of World War I. ...

.

1814–1830: Restoration and reaction

As the four major European powers (

Britain

Britain most often refers to:

* Great Britain, a large island comprising the countries of England, Scotland and Wales

* The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, a sovereign state in Europe comprising Great Britain and the north-eas ...

,

Prussia

Prussia (; ; Old Prussian: ''Prūsija'') was a Germans, German state centred on the North European Plain that originated from the 1525 secularization of the Prussia (region), Prussian part of the State of the Teutonic Order. For centuries, ...

,

Russia

Russia, or the Russian Federation, is a country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia. It is the list of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the world, and extends across Time in Russia, eleven time zones, sharing Borders ...

, and

Austria

Austria, formally the Republic of Austria, is a landlocked country in Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine Federal states of Austria, states, of which the capital Vienna is the List of largest cities in Aust ...

) opposing the

French Empire in the Napoleonic Wars saw Napoleon's power collapsing in 1814, they started planning for the postwar world. The

Treaty of Chaumont

The Treaty of Chaumont was a series of separately-signed but identically-worded agreements in 1814 between the Austrian Empire, the Kingdom of Prussia, the Russian Empire and the United Kingdom. They were dated 1 March 1814, although the actual s ...

of March 1814 reaffirmed decisions that had been made already and which would be ratified by the more important Congress of Vienna of 1814–15. They included the establishment of a

German Confederation

The German Confederation ( ) was an association of 39 predominantly German-speaking sovereign states in Central Europe. It was created by the Congress of Vienna in 1815 as a replacement of the former Holy Roman Empire, which had been dissolved ...

including both Austria and Prussia (plus the

Czech lands

The Czech lands or the Bohemian lands (, ) is a historical-geographical term which denotes the three historical regions of Bohemia, Moravia, and Czech Silesia out of which Czechoslovakia, and later the Czech Republic and Slovakia, were formed. ...

), the division of French protectorates and annexations into independent states, the restoration of the Bourbon kings of Spain, the enlargement of the Netherlands to include what in 1830 became modern Belgium, and the continuation of British subsidies to its allies. The

Treaty of Chaumont

The Treaty of Chaumont was a series of separately-signed but identically-worded agreements in 1814 between the Austrian Empire, the Kingdom of Prussia, the Russian Empire and the United Kingdom. They were dated 1 March 1814, although the actual s ...

united the powers to defeat Napoleon and became the cornerstone of the Concert of Europe, which formed the balance of power for the next two decades.

One goal of diplomacy throughout the period was to achieve a "

balance of power", so that no one or two powers would be dominant. If one power gained an advantage—for example by winning a war and acquiring new territory—its rivals might seek "compensation"—that is, territorial or other gains, even though they were not part of the war in the first place. The bystander might be angry if the winner of the war did not provide enough compensation. For example, in 1866, Prussia and supporting north German States defeated Austria and its southern German allies, but France was angry that it did not get any compensation to balance off the Prussian gains.

Congress of Vienna: 1814–1815

The Congress of Vienna (1814–1815) dissolved the Napoleonic Wars and attempted to restore the monarchies Napoleon had overthrown, ushering in an era of reaction. Under the leadership of

Klemens von Metternich

Klemens Wenzel Nepomuk Lothar, Prince of Metternich-Winneburg zu Beilstein ( ; 15 May 1773 – 11 June 1859), known as Klemens von Metternich () or Prince Metternich, was a German statesman and diplomat in the service of the Austrian Empire. ...

, the prime minister of Austria (1809–1848), and

Lord Castlereagh, the foreign minister of Great Britain (1812–1822), the Congress set up a system to preserve the peace. Under the

Concert of Europe

The Concert of Europe was a general agreement among the great powers of 19th-century Europe to maintain the European balance of power, political boundaries, and spheres of influence. Never a perfect unity and subject to disputes and jockeying ...

(or "Congress system"), the major European powers—Britain, Russia, Prussia, Austria, and (after 1818) France—pledged to meet regularly to resolve differences. This plan was the first of its kind in European history and seemed to promise a way to collectively manage European affairs and promote peace. It was the forerunner of the

League of Nations

The League of Nations (LN or LoN; , SdN) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference (1919–1920), Paris Peace ...

and the

United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is the Earth, global intergovernmental organization established by the signing of the Charter of the United Nations, UN Charter on 26 June 1945 with the stated purpose of maintaining international peace and internationa ...

.

[Norman Rich, ''Great Power Diplomacy: 1814–1914'' (1992) pp. 1–27.] Some historians see the more formal version of the Concert of Europe, constituting the immediate aftermath of the Vienna Congress, as collapsing by 1823,

while other historians see the Concert of Europe as persisting through most of the 19th century.

Historian Richard Langhorne sees the Concert as governing international relations between the European powers until the formation of Germany in 1871, and Concert mechanisms having a more loose but detectable influence in international politics as late as the outbreak of WWI.

The Congress resolved the

Polish–Saxon crisis at Vienna and the

question of Greek independence at

Laibach (Ljubljana).

Three major European congresses took place. The

Congress of Aix-la-Chapelle (1818)

The Congress of Aix-la-Chapelle, held in the autumn of 1818, was a high-level diplomatic meeting of France and the four allied powers Britain, Austria, Prussia and Russia, which had defeated it in 1814. The purpose was to decide the withdrawal of ...

ended the military occupation of France and adjusted downward the 700 million francs the French were obligated to pay as reparations. Tsar

Alexander I of Russia

Alexander I (, ; – ), nicknamed "the Blessed", was Emperor of Russia from 1801, the first king of Congress Poland from 1815, and the grand duke of Finland from 1809 to his death in 1825. He ruled Russian Empire, Russia during the chaotic perio ...

proposed the formation of an entirely new alliance, to include all of the signatories from the Vienna treaties, to guarantee the sovereignty, territorial integrity, and preservation of the ruling governments of all members of this new coalition. The tsar further proposed an international army, with the

Imperial Russian Army

The Imperial Russian Army () was the army of the Russian Empire, active from 1721 until the Russian Revolution of 1917. It was organized into a standing army and a state militia. The standing army consisted of Regular army, regular troops and ...

as its nucleus, to provide the wherewithal to intervene in any country that needed it. Lord Castlereagh saw this as a highly undesirable commitment to reactionary policies. He recoiled at the idea of Russian armies marching across Europe to put down popular uprisings. Furthermore, to admit all the smaller countries would create intrigue and confusion. Britain refused to participate, so the idea was abandoned.

The other meetings proved meaningless as each nation realized the Congresses were not to their advantage, where disputes were resolved with a diminishing degree of effectiveness.

[C. W. Crawley. "International Relations, 1815–1830". In C. W. Crawley, ed., ''The New Cambridge Modern History'', Volume 9: War and Peace in an Age of Upheaval, 1793–1830. (1965) pp. 669–71, 676–77, 683–86.][Roy Bridge. "Allied Diplomacy in Peacetime: The Failure of the Congress 'System', 1815–23". In Alan Sked, ed., ''Europe's Balance of Power, 1815–1848'' (1979), pp' 34–53]

To achieve lasting peace, the

Concert of Europe

The Concert of Europe was a general agreement among the great powers of 19th-century Europe to maintain the European balance of power, political boundaries, and spheres of influence. Never a perfect unity and subject to disputes and jockeying ...

tried to maintain the balance of power. Until the 1860s the territorial boundaries laid down at the Congress of Vienna were maintained, and even more importantly, there was an acceptance of the theme of balance with no major aggression. Otherwise, the Congress system had "failed" by 1823.

In 1818 the British decided not to become involved in continental issues that did not directly affect them. They rejected the plan of Tsar Alexander I to suppress future revolutions. The Concert system fell apart as the common goals of the Great Powers were replaced by growing political and economic rivalries.

Artz says the Congress of Verona in 1822 "marked the end". There was no Congress called to restore the old system during the great

revolutionary upheavals of 1848 with their demands for revision of the Congress of Vienna's frontiers along national lines. Conservative monarchies formed the nominal

Holy Alliance

The Holy Alliance (; ), also called the Grand Alliance, was a coalition linking the absolute monarchist great powers of Austria, Prussia, and Russia, which was created after the final defeat of Napoleon at the behest of Emperor Alexander I of Rus ...

.

This alliance fragmented in the 1850s due to crises in the Ottoman Empire, described as the

Eastern Question.

British policies

British foreign policy was set by

George Canning

George Canning (; 11 April 17708 August 1827) was a British Tory statesman. He held various senior cabinet positions under numerous prime ministers, including two important terms as foreign secretary, finally becoming Prime Minister of the U ...

(1822–1827), who avoided close cooperation with other powers. Britain, with its unchallenged Royal Navy and increasing financial wealth and industrial strength, built its foreign policy on the principle that no state should be allowed to dominate the Continent. It wanted to support the

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

as a bulwark against Russian expansionism. It opposed interventions designed to suppress

liberal democracy

Liberal democracy, also called Western-style democracy, or substantive democracy, is a form of government that combines the organization of a democracy with ideas of liberalism, liberal political philosophy. Common elements within a liberal dem ...

, and was especially worried that France and Spain planned to suppress the independence movement underway in Latin America. Canning cooperated with the United States to promulgate the

Monroe Doctrine

The Monroe Doctrine is a foreign policy of the United States, United States foreign policy position that opposes European colonialism in the Western Hemisphere. It holds that any intervention in the political affairs of the Americas by foreign ...

to preserve newly independent Latin American states. His goal was to prevent French dominance and allow British merchants access to the opening markets.

Abolition of the international slave trade

An important liberal advance was the

abolition

Abolition refers to the act of putting an end to something by law, and may refer to:

*Abolitionism, abolition of slavery

*Capital punishment#Abolition of capital punishment, Abolition of the death penalty, also called capital punishment

*Abolitio ...

of the international slave trade. It began with legislation in Britain and the United States in 1807, which was increasingly enforced over subsequent decades by the

British Royal Navy patrols around Africa. Britain negotiated treaties, or coerced, other nations into agreeing. The result was a reduction of over 95% in the volume of the slave trade from Africa to the New World. About 1000 slaves a year were illegally brought into the United States, as well as some to

Spanish Cuba and the

Empire of Brazil

The Empire of Brazil was a 19th-century state that broadly comprised the territories which form modern Brazil and Uruguay until the latter achieved independence in 1828. The empire's government was a Representative democracy, representative Par ...

. Slavery was

abolished in the British Empire in 1833, the

French Republic in 1848, the

United States in 1865, and

Brazil in 1888.

Spain loses its colonies

Spain was at war with Britain from 1798 to 1808, and the British Royal Navy cut off Spain's contacts with its colonies. Trade was handled by neutral American and Dutch traders. The colonies set up temporary governments or juntas which were effectively independent from the

Spanish Empire

The Spanish Empire, sometimes referred to as the Hispanic Monarchy (political entity), Hispanic Monarchy or the Catholic Monarchy, was a colonial empire that existed between 1492 and 1976. In conjunction with the Portuguese Empire, it ushered ...

. The division exploded between Spaniards who were born in Spain (called ''

peninsulares

In the context of the Spanish Empire, a ''peninsular'' (, pl. ''peninsulares'') was a Spaniard born in Spain residing in the New World, Spanish East Indies, or Spanish Guinea. In the context of the Portuguese Empire, ''reinóis'' (singular ''r ...

'') versus those of Spanish descent born in

New Spain

New Spain, officially the Viceroyalty of New Spain ( ; Nahuatl: ''Yankwik Kaxtillan Birreiyotl''), originally the Kingdom of New Spain, was an integral territorial entity of the Spanish Empire, established by Habsburg Spain. It was one of several ...

(called ''

criollos

In Hispanic America, criollo () is a term used originally to describe people of full Spanish descent born in the viceroyalties. In different Latin American countries, the word has come to have different meanings, mostly referring to the local ...

'' in Spanish or "

creoles" in English). The two groups wrestled for power, with the ''criollos'' leading the call for independence and eventually winning that independence. Spain lost all of its American colonies, except Cuba and Puerto Rico, in a

complex series of revolts from 1808 to 1826.

Multiple revolutions in Latin America allowed the region to break free of the mother country. Repeated attempts to regain control failed, as Spain had no help from European powers. Indeed, Britain and the United States worked against Spain, enforcing the

Monroe Doctrine

The Monroe Doctrine is a foreign policy of the United States, United States foreign policy position that opposes European colonialism in the Western Hemisphere. It holds that any intervention in the political affairs of the Americas by foreign ...

. British merchants and bankers took a dominant role in Latin America. In 1824, the armies of generals

José de San Martín

José Francisco de San Martín y Matorras (; 25 February 177817 August 1850), nicknamed "the Liberator of Argentina, Chile and Peru", was an Argentine general and the primary leader of the southern and central parts of South America's succe ...

of Argentina and

Simón Bolívar

Simón José Antonio de la Santísima Trinidad Bolívar y Palacios (24July 178317December 1830) was a Venezuelan statesman and military officer who led what are currently the countries of Colombia, Venezuela, Ecuador, Peru, Panama, and Bol ...

of Venezuela defeated the last Spanish forces; the final defeat came at the

Battle of Ayacucho

The Battle of Ayacucho (, ) was a decisive military encounter during the Peruvian War of Independence. This battle secured the independence of Peru and ensured independence for the rest of belligerent South American states. In Peru it is conside ...

in southern

Peru

Peru, officially the Republic of Peru, is a country in western South America. It is bordered in the north by Ecuador and Colombia, in the east by Brazil, in the southeast by Bolivia, in the south by Chile, and in the south and west by the Pac ...

.

After the loss of its colonies, Spain played a minor role in international affairs. Spain kept Cuba, which repeatedly revolted in three wars of independence, culminating in the

Cuban War of Independence

The Cuban War of Independence (), also known in Cuba as the Necessary War (), fought from 1895 to 1898, was the last of three liberation wars that Cuba fought against Spain, the other two being the Ten Years' War (1868–1878) and the Litt ...

. The United States demanded reforms from Spain, which Spain refused. The U.S.

intervened by war in 1898. Winning easily, the U.S. took Cuba and gave it partial independence. The U.S. also took the Spanish colonies of the Philippines and Guam. Though it still had small

colonial holdings in North Africa and Equatorial Guinea, Spain's role in international affairs was essentially over.

Greek independence: 1821–1833

The

Greek War of Independence

The Greek War of Independence, also known as the Greek Revolution or the Greek Revolution of 1821, was a successful war of independence by Greek revolutionaries against the Ottoman Empire between 1821 and 1829. In 1826, the Greeks were assisted ...

was the major military conflict in the 1820s. The Great Powers supported the Greeks, but did not want the Ottoman Empire destroyed. Greece was initially to be an autonomous state under Ottoman

suzerainty

A suzerain (, from Old French "above" + "supreme, chief") is a person, state (polity)">state or polity who has supremacy and dominant influence over the foreign policy">polity.html" ;"title="state (polity)">state or polity">state (polity)">st ...

, but by 1832, in the

Treaty of Constantinople, it was recognized as a fully independent kingdom.

After some initial success the Greek rebels were beset by internal disputes. The Ottomans, with major aid from

Egypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

, cruelly crushed the rebellion and harshly punished the Greeks. Humanitarian concerns in Europe were outraged, as typified by English poet

Lord Byron

George Gordon Byron, 6th Baron Byron (22 January 1788 – 19 April 1824) was an English poet. He is one of the major figures of the Romantic movement, and is regarded as being among the greatest poets of the United Kingdom. Among his best-kno ...

. The context of the three Great Powers' intervention was Russia's long-running expansion at the expense of the decaying Ottoman Empire. However Russia's ambitions in the region were seen as a major geostrategic threat by the other European powers. Austria feared the disintegration of the Ottoman Empire would destabilize its southern borders. Russia gave strong emotional support for the fellow

Orthodox Christian Greeks. The British were motivated by strong public support for the Greeks. Fearing unilateral Russian action in support of the Greeks, Britain and France bound Russia by treaty to a joint intervention which aimed to secure Greek autonomy whilst preserving Ottoman territorial integrity as a check on Russia.

The Powers agreed, by the

Treaty of London (1827), to force the Ottoman government to grant the Greeks autonomy within the empire and despatched naval squadrons to Greece to enforce their policy. The decisive Allied naval victory at the

Battle of Navarino

The Battle of Navarino was a naval battle fought on 20 October (O.S. 8 October) 1827, during the Greek War of Independence (1821–1829), in Navarino Bay (modern Pylos), on the west coast of the Peloponnese peninsula, in the Ionian Sea. Allied ...

broke the military power of the Ottomans and their Egyptian allies. Victory saved the fledgling

Greek Republic from collapse. But it required two more military interventions, by Russia in the form of the

Russo-Turkish War of 1828–29 and by a

French expeditionary force to the Peloponnese to force the withdrawal of Ottoman forces from central and southern Greece and to finally secure Greek independence.

Travel, trade, and communications

The world became much smaller as long-distance travel and communications improved dramatically. Every decade there were more ships, more scheduled destinations, faster trips, and lower fares for passengers and cheaper rates for merchandise. This facilitated international trade and international organization. After 1860, the enormous expansion of wheat production in the United States flooded the world market, lowering prices by 40%, and (along with the expansion of local potato farming) made a major contribution to the nutritional welfare of the poor.

Travel

Underwater telegraph cables

Underwater telegraph cables linked the world's major trading nations by the 1860s.

Cargo

sailing ship

A sailing ship is a sea-going vessel that uses sails mounted on Mast (sailing), masts to harness the power of wind and propel the vessel. There is a variety of sail plans that propel sailing ships, employing Square rig, square-rigged or Fore-an ...

s were slow; the average speed of all long-distance Mediterranean voyages to Palestine was only 2.8 knots. Passenger ships achieved greater speed by sacrificing cargo space. The sailing ship records were held by the

clipper

A clipper was a type of mid-19th-century merchant sailing vessel, designed for speed. The term was also retrospectively applied to the Baltimore clipper, which originated in the late 18th century.

Clippers were generally narrow for their len ...

, a very fast sailing ship of the 1843–1869 era. Clippers were narrow for their length, could carry limited bulk freight, small by later 19th-century standards, and had a large total sail area. Their average speed was six knots and they carried passengers across the globe, primarily on the trade routes between Britain and its colonies in the east, in

trans-Atlantic trade, and the New York-to-San Francisco route round

Cape Horn

Cape Horn (, ) is the southernmost headland of the Tierra del Fuego archipelago of southern Chile, and is located on the small Hornos Island. Although not the most southerly point of South America (which is Águila Islet), Cape Horn marks the nor ...

during the

California Gold Rush

The California gold rush (1848–1855) began on January 24, 1848, when gold was found by James W. Marshall at Sutter's Mill in Coloma, California. The news of gold brought approximately 300,000 people to California from the rest of the U ...

. The much faster steam-powered, iron-hulled

ocean liner

An ocean liner is a type of passenger ship primarily used for transportation across seas or oceans. Ocean liners may also carry cargo or mail, and may sometimes be used for other purposes (such as for pleasure cruises or as hospital ships). The ...

became the dominant mode of passenger transportation from the 1850s to the 1950s. It used coal—and needed many coaling stations. After 1900 oil replaced coal and did not require frequent refueling.

Transportation

Freight rates on ocean traffic held steady in the 18th century down to about 1840, and then began a rapid downward plunge. The British dominated world exports, and rates for British freight fell 70% from 1840 to 1910. The

Suez Canal

The Suez Canal (; , ') is an artificial sea-level waterway in Egypt, Indo-Mediterranean, connecting the Mediterranean Sea to the Red Sea through the Isthmus of Suez and dividing Africa and Asia (and by extension, the Sinai Peninsula from the rest ...

cut the shipping time from London to India by a third when it opened in 1869. The same ship could make more voyages in a year, so it could charge less and carry more goods every year.

Technological innovation was steady. Iron hulls replaced wood by mid-century; after 1870, steel replaced iron. It took much longer for steam engines to replace sails. Note the sailing ship across from the ''Lusitania'' in the photograph above. Wind was free, and could move the ship at an average speed of 2–3 knots, unless it was becalmed. Coal was expensive and required coaling stations along the route. A common solution was for a merchant ship to rely mostly on its sails, and only use the steam engine as a backup. The first steam engines were very inefficient, using a great deal of coal. For an ocean voyage in the 1860s, half of the cargo space was given over to coal. The problem was especially acute for warships, because their combat range using coal was strictly limited. Only the British Empire had a network of coaling stations that permitted a global scope for the Royal Navy. Steady improvement gave high-powered compound engines which were much more efficient. The boilers and pistons were built of steel, which could handle much higher pressures than iron. They were first used for high-priority cargo, such as mail and passengers. The arrival of the

steam turbine engine around 1907 dramatically improved efficiency, and the increasing use of oil after 1910 meant far less cargo space had to be devoted to the fuel supply.

Communications

By the 1850s, railways and telegraph lines connected all the major cities inside Western Europe, as well as those inside the United States. Instead of greatly reducing the need for travel, the telegraph made travel easier to plan and replaced the slow long-distance mail service.

Submarine cables were laid to link the continents by telegraph, which was a reality by the 1860s.

1830–1850s

Britain continued as the most important power, followed by Russia, France, Prussia, and Austria. The United States was growing rapidly in size, population and economic strength, especially after its defeat of Mexico in 1848. While the U.S. was generally successful in its efforts to avoid international entanglements, the slavery issue became more and more internally divisive.

The

Crimean War

The Crimean War was fought between the Russian Empire and an alliance of the Ottoman Empire, the Second French Empire, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, and the Kingdom of Sardinia (1720–1861), Kingdom of Sardinia-Piedmont fro ...

(1853–1856) was the only large scale conflict between major powers during this time frame. It became notorious for its very high casualties and very small impact in the long run. Britain strengthened its colonial system, especially in the

British Raj

The British Raj ( ; from Hindustani language, Hindustani , 'reign', 'rule' or 'government') was the colonial rule of the British The Crown, Crown on the Indian subcontinent,

*

* lasting from 1858 to 1947.

*

* It is also called Crown rule ...

(India), while France rebuilt its colonies in Asia and North Africa. Russia continued its expansion south (toward Persia) and east (into Siberia). The Ottoman Empire steadily weakened, losing control in parts of the Balkans to the new states of Greece and Serbia.

In the

Treaty of London, signed in 1839, the Great Powers guaranteed the neutrality of Belgium. Its importance came to a head in 1914 when Germany invaded Belgium in an attempt to outflank and defeat the French. The Germans dismissed the agreement (which predated the formation of Imperial Germany) as a "scrap of paper" in defiance of a British ultimatum to withdraw from Belgium soil immediately leading the United Kingdom to declare war on Germany.

British policies

Britain's repeal in 1846 of the tariff on food imports, called the

Corn Laws

The Corn Laws were tariffs and other trade restrictions on imported food and corn enforced in the United Kingdom between 1815 and 1846. The word ''corn'' in British English denotes all cereal grains, including wheat, oats and barley. The la ...

, marked a major turning point that made free trade the national policy of Great Britain into the 20th century. Repeal demonstrated the power of "Manchester-school" industrial interests over protectionist agricultural interests.

From 1830 to 1865, with a few interruptions,

Lord Palmerston

Henry John Temple, 3rd Viscount Palmerston (20 October 1784 – 18 October 1865), known as Lord Palmerston, was a British statesman and politician who served as prime minister of the United Kingdom from 1855 to 1858 and from 1859 to 1865. A m ...

set British foreign policy. He had six main goals that he pursued: first, he defended British interests whenever they seemed threatened, and upheld Britain's prestige abroad. Second, he was a master at using the media to win public support from all ranks of society. Third, he promoted the spread of constitutional Liberal governments like in Britain, along the model of the

1832 Reform Act. He therefore welcomed liberal revolutions as in France (1830), and Greece (1843). Fourth, he promoted British nationalism, looking for advantages for his nation as in the Belgian revolt of 1830 and the Italian unification of 1859. He avoided wars, and operated with only a very small British Army. He felt the best way to promote peace was to maintain a balance of power to prevent any nation—especially France or Russia—from dominating Europe.

Palmerston cooperated with France when necessary for the balance of power, but did not make permanent alliances with anyone. He tried to keep autocratic nations like Russia and Austria in check; he supported liberal regimes because they led to greater stability in the international system. However he also supported the autocratic Ottoman Empire because it blocked Russian expansion. Second in importance to Palmerston was

Lord Aberdeen, a diplomat, foreign minister and prime minister. Before the Crimean War debacle that ended his career he scored numerous diplomatic triumphs, starting in 1813–1814 when as ambassador to the Austrian Empire he negotiated the alliances and financing that led to the defeat of Napoleon. In Paris he normalized relations with the newly restored Bourbon government and convinced his government they could be trusted. He worked well with top European diplomats such as his friends

Klemens von Metternich

Klemens Wenzel Nepomuk Lothar, Prince of Metternich-Winneburg zu Beilstein ( ; 15 May 1773 – 11 June 1859), known as Klemens von Metternich () or Prince Metternich, was a German statesman and diplomat in the service of the Austrian Empire. ...

in Vienna and

François Guizot

François Pierre Guillaume Guizot (; 4 October 1787 – 12 September 1874) was a French historian, orator and Politician, statesman. Guizot was a dominant figure in French politics between the July Revolution, Revolution of 1830 and the Revoluti ...

in Paris. He brought Britain into the center of Continental diplomacy on critical issues, such as the local wars in Greece, Portugal and Belgium. Simmering troubles with the United States were ended by compromising the border dispute in Maine that gave most of the land to the Americans but gave Canada a strategically important link to a warm water port. Aberdeen played a central role in provoking and winning the

Opium Wars

The Opium Wars () were two conflicts waged between China and Western powers during the mid-19th century.

The First Opium War was fought from 1839 to 1842 between China and Britain. It was triggered by the Chinese government's campaign to ...

against China, gaining control of Hong Kong in the process.

Belgian Revolution

Catholic Belgium in 1830 broke away from the

Protestantism

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that emphasizes Justification (theology), justification of sinners Sola fide, through faith alone, the teaching that Salvation in Christianity, salvation comes by unmerited Grace in Christianity, divin ...

of

United Kingdom of the Netherlands

The United Kingdom of the Netherlands is the unofficial name given to the Kingdom of the Netherlands as it existed from 1815 to 1839. The United Netherlands was created in the aftermath of the Napoleonic Wars through the fusion of territories t ...

and established an independent

Kingdom of Belgium

Belgium, officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. Situated in a coastal lowland region known as the Low Countries, it is bordered by the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Luxembourg to the southe ...

. Southern liberals and

Catholics

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics worldwide as of 2025. It is among the world's oldest and largest international institut ...

(mostly

French speaking) united against King

William I William I may refer to:

Kings

* William the Conqueror (–1087), also known as William I, King of England

* William I of Sicily (died 1166)

* William I of Scotland (died 1214), known as William the Lion

* William I of the Netherlands and Luxembour ...

's autocratic rule and efforts to put Dutch education on equal standing with French (in the Southern parts of the kingdom). There were high levels of unemployment and industrial unrest among the working classes. There was small-scale fighting but it took years before the Netherlands finally recognized defeat. In 1839 the Dutch accepted Belgian independence by signing the

Treaty of London. The major powers guaranteed Belgian independence.

Revolutions of 1848

The

Revolutions of 1848

The revolutions of 1848, known in some countries as the springtime of the peoples or the springtime of nations, were a series of revolutions throughout Europe over the course of more than one year, from 1848 to 1849. It remains the most widespre ...

were a series of uncoordinated political upheavals throughout Europe in 1848. They attempted to overthrow reactionary monarchies. This was the most widespread

revolutionary wave in European history. It reached most of Europe, but much less so in the Americas, Britain and Belgium, where

liberalism

Liberalism is a Political philosophy, political and moral philosophy based on the Individual rights, rights of the individual, liberty, consent of the governed, political equality, the right to private property, and equality before the law. ...

was recently established. However the reactionary forces prevailed, especially with Russian help, and many rebels went into exile. There were some social reforms.

The revolutions were essentially

liberal democratic

Liberal democracy, also called Western-style democracy, or substantive democracy, is a form of government that combines the organization of a democracy with ideas of liberal political philosophy. Common elements within a liberal democracy are: ...

in nature, with the aim of removing the old monarchical structures and creating independent

nation state

A nation state, or nation-state, is a political entity in which the State (polity), state (a centralized political organization ruling over a population within a territory) and the nation (a community based on a common identity) are (broadly ...

s. The revolutions spread across Europe after an initial revolution began in

France in February. Over 50 countries were affected. Liberal ideas had been in the air for a decade and activists from each country drew from the common pool, but they did not form direct links with revolutionaries in nearby countries.

Key contributing factors were widespread dissatisfaction with old established political leadership, demands for more participation in government and democracy, demands for

freedom of the press

Freedom of the press or freedom of the media is the fundamental principle that communication and expression through various media, including printed and electronic Media (communication), media, especially publication, published materials, shoul ...

, other demands made by the

working class

The working class is a subset of employees who are compensated with wage or salary-based contracts, whose exact membership varies from definition to definition. Members of the working class rely primarily upon earnings from wage labour. Most c ...

, the upsurge of

nationalism

Nationalism is an idea or movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the state. As a movement, it presupposes the existence and tends to promote the interests of a particular nation, Smith, Anthony. ''Nationalism: Theory, I ...

, and the regrouping of established government forces. Liberalism at this time meant the replacement of

autocratic governments by

constitutional states under the

rule of law

The essence of the rule of law is that all people and institutions within a Body politic, political body are subject to the same laws. This concept is sometimes stated simply as "no one is above the law" or "all are equal before the law". Acco ...

. It had become the creed of the

bourgeoisie

The bourgeoisie ( , ) are a class of business owners, merchants and wealthy people, in general, which emerged in the Late Middle Ages, originally as a "middle class" between the peasantry and aristocracy. They are traditionally contrasted wi ...

, but they were not in power. It was the main factor in France. The main factor in the German, Italian and Austrian states was nationalism. Stimulated by the Romantic movement, nationalism had aroused numerous ethnic/language groups in their common past. Germans and Italians lived under multiple governments and demanded to be united in their own national state. Regarding the

Austrian Empire

The Austrian Empire, officially known as the Empire of Austria, was a Multinational state, multinational European Great Powers, great power from 1804 to 1867, created by proclamation out of the Habsburg monarchy, realms of the Habsburgs. Duri ...

, the many ethnicities suppressed by foreign rule—especially Hungarians—fought for a revolution.

The uprisings were led by temporary coalitions of reformers, the middle classes and workers, which did not hold together for long. The start was in France, where large crowds forced King

Louis Philippe I

Louis Philippe I (6 October 1773 – 26 August 1850), nicknamed the Citizen King, was King of the French from 1830 to 1848, the penultimate monarch of France, and the last French monarch to bear the title "King". He abdicated from his throne ...

to abdicate. Across Europe came the sudden realization that it was indeed possible to destroy a monarchy. Tens of thousands of people were killed, and many more were forced into exile. Significant lasting reforms included the abolition of

serfdom

Serfdom was the status of many peasants under feudalism, specifically relating to manorialism and similar systems. It was a condition of debt bondage and indentured servitude with similarities to and differences from slavery. It developed du ...

in Austria and Hungary, the end of

absolute monarchy in Denmark, and the introduction of

representative democracy

Representative democracy, also known as indirect democracy or electoral democracy, is a type of democracy where elected delegates represent a group of people, in contrast to direct democracy. Nearly all modern Western-style democracies func ...

in the Netherlands. The revolutions were most important in

France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

, the Netherlands, the

states of the German Confederation

The states of the German Confederation were member states of the German Confederation, from 20 June 1815 until 24 August 1866.

On the whole, its territory nearly coincided with that remaining in the Holy Roman Empire at the outbreak of the Fren ...

,

Italy

Italy, officially the Italian Republic, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe, Western Europe. It consists of Italian Peninsula, a peninsula that extends into the Mediterranean Sea, with the Alps on its northern land b ...

, and the

Austrian Empire

The Austrian Empire, officially known as the Empire of Austria, was a Multinational state, multinational European Great Powers, great power from 1804 to 1867, created by proclamation out of the Habsburg monarchy, realms of the Habsburgs. Duri ...

.

Reactionary forces ultimately prevailed, aided by Russian military intervention in Hungary, and the strong traditional

aristocracies and

established churches. The revolutionary surge was sudden and unexpected, catching the traditional forces unprepared. But the revolutionaries were also unprepared – they had no plans on how to hold power when it was suddenly in their hands, and bickered endlessly. Reaction came much more gradually, but the aristocrats had the advantages of vast wealth, large networks of contacts, many subservient subjects, and the specific goal in mind of returning to the old status quo.

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire was only briefly involved in the Napoleonic Wars through the

French campaign in Egypt and Syria

The French invasion of Egypt and Syria (1798–1801) was a military expedition led by Napoleon Bonaparte during the French Revolutionary Wars. The campaign aimed to undermine British trade routes, expand French influence, and establish a ...

, 1798–1801. It was not invited to the Vienna Conference. During this period the Empire steadily weakened militarily, and lost most of its holdings in Europe (starting with Greece) and in North Africa (starting with Egypt). Its greatest enemy was Russia, while its chief supporter was Britain.

As the 19th century progressed the Ottoman Empire grew weaker militarily and economically. It lost more and more control over local governments especially in Europe. It started borrowing large sums and went bankrupt in 1875. Britain increasingly became its chief ally and protector, even fighting the

Crimean War

The Crimean War was fought between the Russian Empire and an alliance of the Ottoman Empire, the Second French Empire, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, and the Kingdom of Sardinia (1720–1861), Kingdom of Sardinia-Piedmont fro ...

against Russia in the 1850s to help it survive. Three British leaders played major roles.

Lord Palmerston

Henry John Temple, 3rd Viscount Palmerston (20 October 1784 – 18 October 1865), known as Lord Palmerston, was a British statesman and politician who served as prime minister of the United Kingdom from 1855 to 1858 and from 1859 to 1865. A m ...

, who in the 1830–1865 era considered the Ottoman Empire an essential component in the balance of power, was the most favourable toward Constantinople.

William Gladstone

William Ewart Gladstone ( ; 29 December 1809 – 19 May 1898) was a British politican, starting as Conservative MP for Newark and later becoming the leader of the Liberal Party.

In a career lasting over 60 years, he was Prime Minister ...

in the 1870s sought to build a Concert of Europe that would support the survival of the empire. In the 1880s and 1890s

Lord Salisbury

Robert Arthur Talbot Gascoyne-Cecil, 3rd Marquess of Salisbury (; 3 February 183022 August 1903), known as Lord Salisbury, was a British statesman and Conservative Party (UK), Conservative politician who served as Prime Minister of the United ...

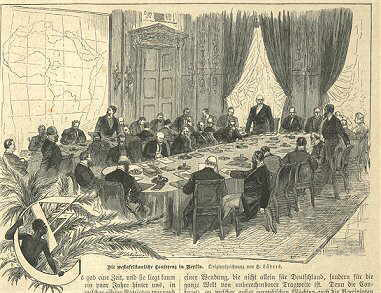

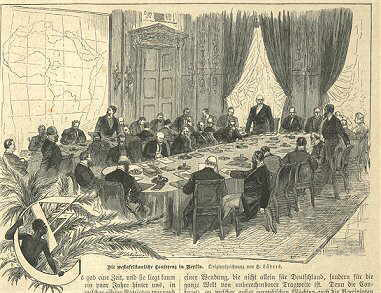

contemplated an orderly dismemberment of it, in such a way as to reduce rivalry between the greater powers. The Berlin Conference on Africa of 1884 was, except for the abortive Hague Conference of 1899, the last great international political summit before 1914. Gladstone stood alone in advocating concerted instead of individual action regarding the internal administration of Egypt, the reform of the Ottoman Empire, and the opening-up of Africa. Bismarck and Lord Salisbury rejected Gladstone's position and were more representative of the consensus.

Serbian independence

A successful uprising against the Ottomans marked the foundation of

modern Serbia. The Serbian Revolution took place between 1804 and 1835, as this territory evolved from an

Ottoman province into a

constitutional monarchy

Constitutional monarchy, also known as limited monarchy, parliamentary monarchy or democratic monarchy, is a form of monarchy in which the monarch exercises their authority in accordance with a constitution and is not alone in making decisions. ...

and a modern

Serbia

, image_flag = Flag of Serbia.svg

, national_motto =

, image_coat = Coat of arms of Serbia.svg

, national_anthem = ()

, image_map =

, map_caption = Location of Serbia (gree ...

. The first part of the period, from 1804 to 1815, was marked by a violent struggle for independence with two armed uprisings. The later period (1815–1835) witnessed a peaceful consolidation of political power of the increasingly autonomous Serbia, culminating in the recognition of the right to hereditary rule by

Serbian princes

Serbian may refer to:

* Pertaining to Serbia in Southeast Europe; in particular

**Serbs, a South Slavic ethnic group native to the Balkans

** Serbian language

** Serbian culture

**Demographics of Serbia, includes other ethnic groups within the co ...

in 1830 and 1833 and the territorial expansion of the young monarchy. The adoption of the first written

Constitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organization or other type of entity, and commonly determines how that entity is to be governed.

When these pri ...

in 1835 abolished

feudalism

Feudalism, also known as the feudal system, was a combination of legal, economic, military, cultural, and political customs that flourished in Middle Ages, medieval Europe from the 9th to 15th centuries. Broadly defined, it was a way of struc ...

and

serfdom

Serfdom was the status of many peasants under feudalism, specifically relating to manorialism and similar systems. It was a condition of debt bondage and indentured servitude with similarities to and differences from slavery. It developed du ...

, and made the country

suzerain

A suzerain (, from Old French "above" + "supreme, chief") is a person, state (polity)">state or polity who has supremacy and dominant influence over the foreign policy and economic relations of another subordinate party or polity, but allows i ...

.

Crimean War

The Crimean War (1853–1856) was fought between Russia on the one hand and an alliance of Great Britain, France, Sardinia, and the Ottoman Empire on the other. Russia was defeated.

In 1851, France under Emperor

Napoleon III

Napoleon III (Charles-Louis Napoléon Bonaparte; 20 April 18089 January 1873) was President of France from 1848 to 1852 and then Emperor of the French from 1852 until his deposition in 1870. He was the first president, second emperor, and last ...

compelled the

Sublime Porte

The Sublime Porte, also known as the Ottoman Porte or High Porte ( or ''Babıali''; ), was a synecdoche or metaphor used to refer collectively to the central government of the Ottoman Empire in Istanbul. It is particularly referred to the buildi ...

(the Ottoman government) to recognize it as the protector of Christian sites in the Holy Land. Russia denounced this claim, since it claimed to be the protector of all Eastern Orthodox Christians in the Ottoman Empire. France sent its fleet to the Black Sea; Russia responded with its own show of force. In 1851, Russia sent troops into the

Ottoman provinces of

Moldavia

Moldavia (, or ; in Romanian Cyrillic alphabet, Romanian Cyrillic: or ) is a historical region and former principality in Eastern Europe, corresponding to the territory between the Eastern Carpathians and the Dniester River. An initially in ...

and

Wallachia

Wallachia or Walachia (; ; : , : ) is a historical and geographical region of modern-day Romania. It is situated north of the Lower Danube and south of the Southern Carpathians. Wallachia was traditionally divided into two sections, Munteni ...

. Britain, now fearing for the security of the Ottoman Empire, sent a fleet to join with the French expecting the Russians would back down. Diplomatic efforts failed. The Sultan declared war against Russia in October 1851. Following an Ottoman naval disaster in November, Britain and France declared war against Russia. Most of the battles took place in the

Crimean peninsula

Crimea ( ) is a peninsula in Eastern Europe, on the northern coast of the Black Sea, almost entirely surrounded by the Black Sea and the smaller Sea of Azov. The Isthmus of Perekop connects the peninsula to Kherson Oblast in mainland Ukrai ...

, which the Allies finally seized.

Russia was defeated and was forced to accept the

Treaty of Paris, signed on 30 March 1856, ending the war. The Powers promised to respect Ottoman independence and territorial integrity. Russia gave up a little land and relinquished its claim to a protectorate over the

Christians in the Ottoman domains. In a major blow to Russian power and prestige, the

Black Sea

The Black Sea is a marginal sea, marginal Mediterranean sea (oceanography), mediterranean sea lying between Europe and Asia, east of the Balkans, south of the East European Plain, west of the Caucasus, and north of Anatolia. It is bound ...

was

demilitarized

A demilitarized zone (DMZ or DZ) is an area in which treaties or agreements between states, military powers or contending groups forbid military installations, activities, or personnel. A DZ often lies along an established frontier or boundary ...

, and an international commission was set up to guarantee

freedom of commerce and navigation on the

Danube River

The Danube ( ; see also other names) is the second-longest river in Europe, after the Volga in Russia. It flows through Central and Southeastern Europe, from the Black Forest south into the Black Sea. A large and historically important riv ...

. Moldavia and Wallachia remained under nominal Ottoman rule, but would be granted independent constitutions and national assemblies.

New rules of wartime commerce were set out: (1)

privateer

A privateer is a private person or vessel which engages in commerce raiding under a commission of war. Since robbery under arms was a common aspect of seaborne trade, until the early 19th century all merchant ships carried arms. A sovereign o ...

ing was illegal; (2) a neutral flag covered enemy goods except

contraband

Contraband (from Medieval French ''contrebande'' "smuggling") is any item that, relating to its nature, is illegal to be possessed or sold. It comprises goods that by their nature are considered too dangerous or offensive in the eyes of the leg ...

; (3) neutral goods, except contraband, were not liable to capture under an enemy flag; (4) a

blockade

A blockade is the act of actively preventing a country or region from receiving or sending out food, supplies, weapons, or communications, and sometimes people, by military force.

A blockade differs from an embargo or sanction, which are ...

, to be legal, had to be effective.

The war helped modernize warfare by introducing major new technologies such as

railways

Rail transport (also known as train transport) is a means of transport using wheeled vehicles running in tracks, which usually consist of two parallel steel rails. Rail transport is one of the two primary means of land transport, next to roa ...

, the

telegraph

Telegraphy is the long-distance transmission of messages where the sender uses symbolic codes, known to the recipient, rather than a physical exchange of an object bearing the message. Thus flag semaphore is a method of telegraphy, whereas ...

, and

modern nursing methods. In the long run the war marked a turning point in Russian domestic and foreign policy. The Imperial Russian Army demonstrated its weakness, its poor leadership, and its lack of modern weapons and technology.

Russia's weak economy was unable to fully support its military adventures, so in the future it redirected its attention to much weaker Muslim areas in Central Asia, and left Europe alone. Russian intellectuals used the humiliating defeat to demand fundamental reform of the government and social system. The war weakened both Russia and Austria, so they could no longer promote stability. This opened the way for Napoleon III,

Cavour (in Italy) and

Otto von Bismarck

Otto, Prince of Bismarck, Count of Bismarck-Schönhausen, Duke of Lauenburg (; born ''Otto Eduard Leopold von Bismarck''; 1 April 1815 – 30 July 1898) was a German statesman and diplomat who oversaw the unification of Germany and served as ...

(in Germany) to launch a series of wars in the 1860s that reshaped Europe.

Moldavia and Wallachia

In a largely peaceful transition, the

Ottoman vassal states of

Moldavia

Moldavia (, or ; in Romanian Cyrillic alphabet, Romanian Cyrillic: or ) is a historical region and former principality in Eastern Europe, corresponding to the territory between the Eastern Carpathians and the Dniester River. An initially in ...

and

Wallachia

Wallachia or Walachia (; ; : , : ) is a historical and geographical region of modern-day Romania. It is situated north of the Lower Danube and south of the Southern Carpathians. Wallachia was traditionally divided into two sections, Munteni ...

broke away slowly from the Ottoman Empire,

uniting into what would become modern

Romania

Romania is a country located at the crossroads of Central Europe, Central, Eastern Europe, Eastern and Southeast Europe. It borders Ukraine to the north and east, Hungary to the west, Serbia to the southwest, Bulgaria to the south, Moldova to ...

in 1859, and finally achieving independence in 1878. The two principalities had long been under Ottoman control, but both Russia and Austria also wanted them, making the region a site of conflict in the 19th century. The population was largely Orthodox in religion and spoke

Romanian, although there were certain

ethnic minorities

The term "minority group" has different meanings, depending on the context. According to common usage, it can be defined simply as a group in society with the least number of individuals, or less than half of a population. Usually a minority g ...

, such as Jews and Greeks. The provinces were occupied by Russia after the

Treaty of Adrianople in 1829. Russian and Turkish troops combined to suppress the

Moldavian and

Wallachian revolutions of 1848. During the Crimean War, Austria took control of the principalities. The population decided on unification on the basis of historical, cultural and ethnic connections. It took effect in 1859 after the double election of

Alexandru Ioan Cuza

Alexandru Ioan Cuza (, or Alexandru Ioan I, also Anglicised as Alexander John Cuza; 20 March 1820 – 15 May 1873) was the first ''domnitor'' (prince) of the Romanian Principalities through his double election as List of monarchs of Moldavia ...

as Prince of the

United Principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia

The United Principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia (), commonly called United Principalities or Wallachia and Moldavia, was the personal union of the Principality of Moldavia and the Principality of Wallachia. The union was formed on when Alexa ...

(renamed the United Principalities of Romania in 1862).

With Russian intervention, the

Kingdom of Romania

The Kingdom of Romania () was a constitutional monarchy that existed from with the crowning of prince Karl of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen as King of Romania, King Carol I of Romania, Carol I (thus beginning the Romanian royal family), until 1947 wit ...

officially became independent in 1878. It then focused its attention on

Transylvania

Transylvania ( or ; ; or ; Transylvanian Saxon dialect, Transylvanian Saxon: ''Siweberjen'') is a List of historical regions of Central Europe, historical and cultural region in Central Europe, encompassing central Romania. To the east and ...

, a region historically part of

Hungary

Hungary is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning much of the Pannonian Basin, Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Croatia and ...

but with about two million ethnic

Romanians

Romanians (, ; dated Endonym and exonym, exonym ''Vlachs'') are a Romance languages, Romance-speaking ethnic group and nation native to Central Europe, Central, Eastern Europe, Eastern, and Southeastern Europe. Sharing a Culture of Romania, ...

. Finally, when the

Austro-Hungarian Empire collapsed at the end of the World War I,

Romania

Romania is a country located at the crossroads of Central Europe, Central, Eastern Europe, Eastern and Southeast Europe. It borders Ukraine to the north and east, Hungary to the west, Serbia to the southwest, Bulgaria to the south, Moldova to ...

united with Transylvania.

United States defeats Mexico, 1846–1848

Mexico

Mexico, officially the United Mexican States, is a country in North America. It is the northernmost country in Latin America, and borders the United States to the north, and Guatemala and Belize to the southeast; while having maritime boundar ...

refused to recognize the 1845 U.S.

annexation of Texas. It considered the

Republic of Texas

The Republic of Texas (), or simply Texas, was a country in North America that existed for close to 10 years, from March 2, 1836, to February 19, 1846. Texas shared borders with Centralist Republic of Mexico, the Republic of the Rio Grande, an ...

to be Mexican territory—it did not recognize the 1836

Velasco treaty signed by then Mexican President and Commander-in-Chief

Antonio López de Santa Anna

Antonio de Padua María Severino López de Santa Anna y Pérez de Lebrón (21 February 1794 – 21 June 1876),Callcott, Wilfred H., "Santa Anna, Antonio Lopez De,''Handbook of Texas Online'' Retrieved 18 April 2017. often known as Santa Anna, wa ...

under duress while he was a prisoner of the

Texian Army

The Texian Army, also known as the Revolutionary Army and Army of the People, was the land warfare branch of the Texian armed forces during the Texas Revolution. It spontaneously formed from the Texian Militia in October 1835 following the Bat ...

, after being defeated in the final battle of the

Texas Revolution

The Texas Revolution (October 2, 1835 – April 21, 1836) was a rebellion of colonists from the United States and Tejanos (Hispanic Texans) against the Centralist Republic of Mexico, centralist government of Mexico in the Mexican state of ...

. Of particular issue for Mexico was Texas' claim of sovereignty stretching down to the

Rio Grande

The Rio Grande ( or ) in the United States or the Río Bravo (del Norte) in Mexico (), also known as Tó Ba'áadi in Navajo language, Navajo, is one of the principal rivers (along with the Colorado River) in the Southwestern United States a ...

. While this was the border stipulated to at Velasco, the Texian government never managed to cement its authority south of the

Neuces. Regardless Texas operated as a de facto independent republic during the interim between the revolution and being annexed into the U.S. Following the admission of Texas as an American state-based on the border dilineated in the treaty of Velasco, Mexico severed diplomatic ties with U.S., and both countries moved to occupy the disputed territory. The situation quickly escalated; after the

Mexican Army

The Mexican Army () is the combined Army, land and Air Force, air branch and is the largest part of the Mexican Armed Forces; it is also known as the National Defense Army.

The Army is under the authority of the Secretariat of National Defense o ...

ambushed U.S. forces patrolling the area, the United States declared war in May 1846. The

United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the primary Land warfare, land service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is designated as the Army of the United States in the United States Constitution.Article II, section 2, clause 1 of th ...

quickly took the initiative, capturing

Santa Fe de Nuevo México

Santa Fe de Nuevo México (; shortened as Nuevo México or Nuevo Méjico, and translated as New Mexico in English) was a province of the Spanish Empire and New Spain, and later a territory of independent Mexico. The first capital was San Juan d ...

and

Alta California

Alta California (, ), also known as Nueva California () among other names, was a province of New Spain formally established in 1804. Along with the Baja California peninsula, it had previously comprised the province of , but was made a separat ...

, and invading

northern Mexico

Northern Mexico ( ), commonly referred as , is an informal term for the northern cultural and geographical area in Mexico. Depending on the source, it contains some or all of the states of Baja California, Baja California Sur, Chihuahua (state), ...

. In March 1847, the

U.S. Navy and Marines commenced the siege of Veracruz, Mexico's largest port. After securing the harbor, the U.S. invasion army proceeded on to

capture Mexico City in September, by which time virtually all of Mexico had been overrun by U.S. forces. The

Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo

The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo officially ended the Mexican–American War (1846–1848). It was signed on 2 February 1848 in the town of Villa de Guadalupe, Mexico City, Guadalupe Hidalgo.

After the defeat of its army and the fall of the cap ...

was signed in February 1848, ending the war, the terms included Mexican recognition of Texas as an American state according to the borders agreed to at Velasco, in addition, Mexico ceded their

northern frontier territories to the U.S. in exchange for $15 million (US dollars), America further agreed to forgive $3.25 million in Mexican debt. In total, Mexico relinquished about 55% of its pre-war territorial claims to the United States.

Brazil and Argentina

Brazil in 1822

became independent of Lisbon. Externally, it faced pressure from Great Britain to end its participation in the

Atlantic slave trade

The Atlantic slave trade or transatlantic slave trade involved the transportation by slave traders of Slavery in Africa, enslaved African people to the Americas. European slave ships regularly used the triangular trade route and its Middle Pass ...

. Brazil fought wars in the

La Plata river region: the

Cisplatine War

The Cisplatine War was an armed conflict fought in the 1820s between the Empire of Brazil and the United Provinces of the Río de la Plata over control of Brazil's Cisplatina province. It was fought in the aftermath of the United Provinces' an ...

against Argentina (in 1825); the

Platine War