Innu Map on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

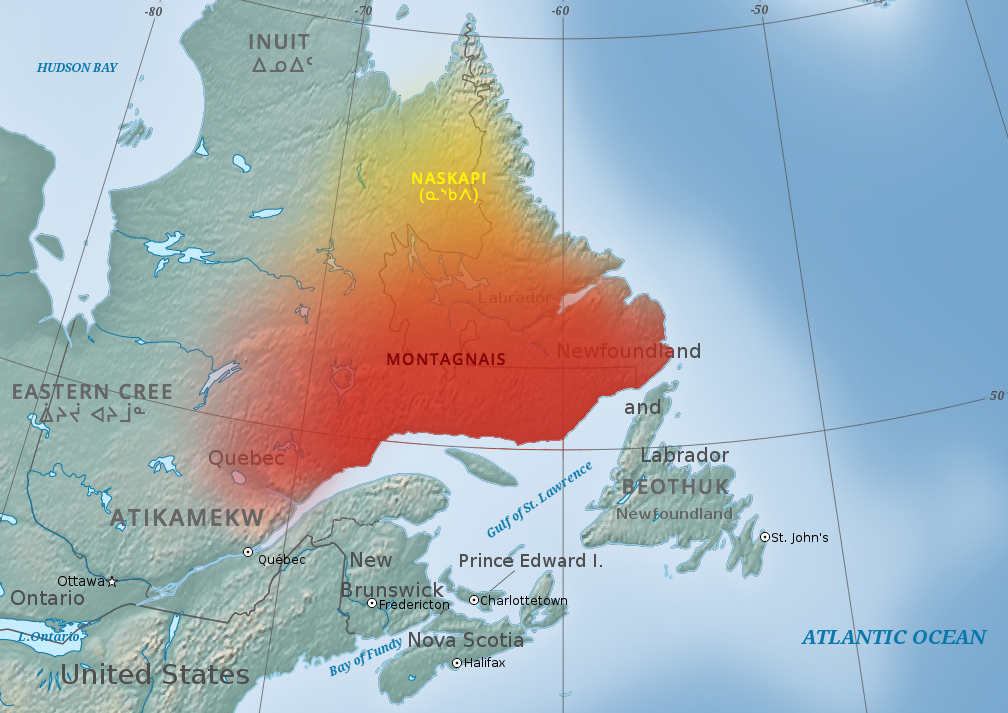

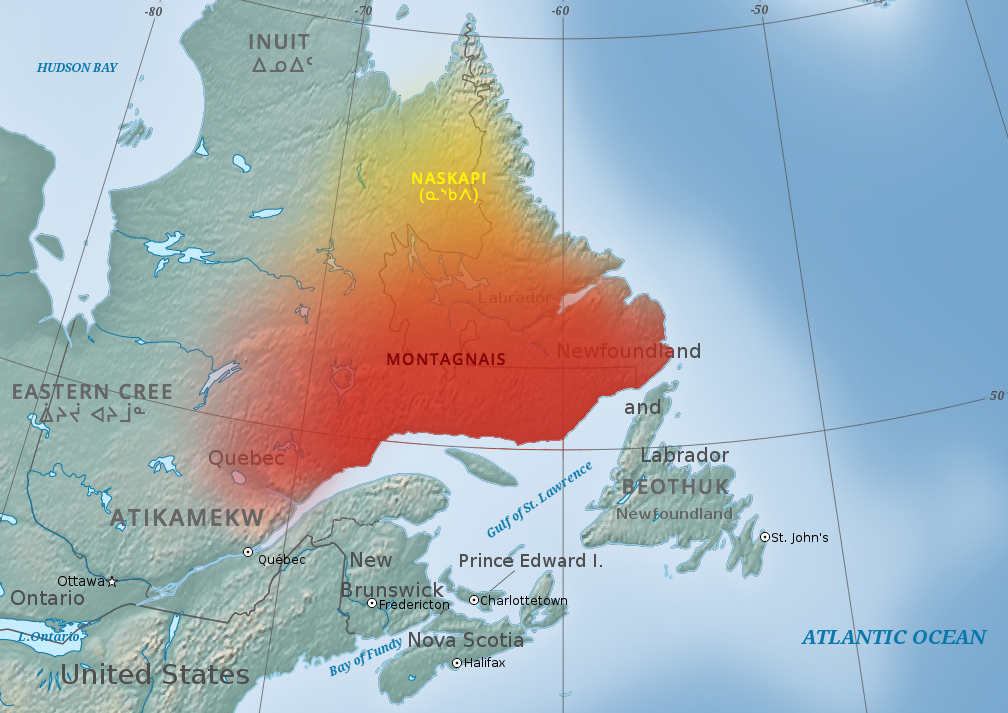

The Innu/Ilnu ('man, person'), formerly called Montagnais (French for '

The people are frequently classified by the geography of their primary locations:

*the ''Neenoilno'', live along the north shore of the Gulf of St. Lawrence, in Quebec; they have historically been referred to by Europeans as ''Montagnais'' (French for "

The people are frequently classified by the geography of their primary locations:

*the ''Neenoilno'', live along the north shore of the Gulf of St. Lawrence, in Quebec; they have historically been referred to by Europeans as ''Montagnais'' (French for "

/ref> By 2000, the Innu island community of Davis Inlet asked the Canadian government to assist with a local

''Legislative Gazette'' archives

(.pdf file). Retrieved March 20, 2009. According to the

"Sharon Fontaine-Ishpatao se plaît à jouer"

''Le Nord-Côtier'', August 2, 2022. *

Official website of the Innu Nation of Labrador.

Official website of the Naskapi Nation of Kawawachikamach, Quebec

{{Authority control Algonquian peoples Algonquian ethnonyms Ethnic groups in Canada Indigenous peoples in Canada

mountain people

Hill people, also referred to as mountain people, is a general term for people who live in the hills and mountains.

This includes all rugged land above and all land (including plateaus) above elevation.

The climate is generally harsh, with s ...

'; ), are the Indigenous Canadians

Indigenous peoples in Canada (also known as Aboriginals) are the Indigenous peoples within the boundaries of Canada. They comprise the First Nations, Inuit, and Métis, representing roughly 5.0% of the total Canadian population. There are over ...

who inhabit northeastern Labrador

Labrador () is a geographic and cultural region within the Canadian province of Newfoundland and Labrador. It is the primarily continental portion of the province and constitutes 71% of the province's area but is home to only 6% of its populatio ...

in present-day Newfoundland and Labrador

Newfoundland and Labrador is the easternmost province of Canada, in the country's Atlantic region. The province comprises the island of Newfoundland and the continental region of Labrador, having a total size of . As of 2025 the populatio ...

and some portions of Quebec

Quebec is Canada's List of Canadian provinces and territories by area, largest province by area. Located in Central Canada, the province shares borders with the provinces of Ontario to the west, Newfoundland and Labrador to the northeast, ...

. They refer to their traditional homeland as ''Nitassinan

Nitassinan () is the ancestral homeland of the Innu, an indigenous people of Eastern Quebec and Labrador, Canada. Nitassinan means "our land" in the Innu language. The territory covers the eastern portion of the Labrador peninsula.'' Nitassi ...

'' ('Our Land', ᓂᑕᔅᓯᓇᓐ) or ''Innu-assi'' ('Innu Land').

The ancestors of the modern First Nations

First nations are indigenous settlers or bands.

First Nations, first nations, or first peoples may also refer to:

Indigenous groups

*List of Indigenous peoples

*First Nations in Canada, Indigenous peoples of Canada who are neither Inuit nor Mé ...

were known to have lived on these lands as hunter-gatherer

A hunter-gatherer or forager is a human living in a community, or according to an ancestrally derived Lifestyle, lifestyle, in which most or all food is obtained by foraging, that is, by gathering food from local naturally occurring sources, esp ...

s for many thousands of years. To support their seasonal hunting migrations, they created portable tents made of animal skins. Their subsistence activities were historically centred on hunting and trapping caribou

The reindeer or caribou (''Rangifer tarandus'') is a species of deer with circumpolar distribution, native to Arctic, subarctic, tundra, boreal, and mountainous regions of Northern Europe, Siberia, and North America. It is the only represe ...

, moose

The moose (: 'moose'; used in North America) or elk (: 'elk' or 'elks'; used in Eurasia) (''Alces alces'') is the world's tallest, largest and heaviest extant species of deer and the only species in the genus ''Alces''. It is also the tal ...

, deer

A deer (: deer) or true deer is a hoofed ruminant ungulate of the family Cervidae (informally the deer family). Cervidae is divided into subfamilies Cervinae (which includes, among others, muntjac, elk (wapiti), red deer, and fallow deer) ...

, and small game.

Their language, which changed over time from Old Montagnais to Innu-aimun

Innu-aimun or Montagnais is an Algonquian language spoken by over 10,000 Innu in Labrador and Quebec in Eastern Canada. It is a member of the Cree–Montagnais–Naskapi dialect continuum and is spoken in various dialects depending on the com ...

(popularly known since the French colonial era as Montagnais), is spoken throughout Nitassinan, with certain dialect differences. It is part of the Cree

The Cree, or nehinaw (, ), are a Indigenous peoples of the Americas, North American Indigenous people, numbering more than 350,000 in Canada, where they form one of the country's largest First Nations in Canada, First Nations. They live prim ...

–Montagnais–Naskapi

The Naskapi (Nascapi, Naskapee, Nascapee) are an Indigenous people of the Subarctic native to the historical region St'aschinuw (ᒋᑦ ᐊᔅᒋᓄᐤ, meaning 'our Clusivity, nclusiveland'), which was located in present day northern Qu ...

dialect continuum

A dialect continuum or dialect chain is a series of Variety (linguistics), language varieties spoken across some geographical area such that neighboring varieties are Mutual intelligibility, mutually intelligible, but the differences accumulat ...

, and is unrelated to the Inuit languages

The Inuit languages are a closely related group of Indigenous languages of the Americas, indigenous American languages traditionally spoken across the North American Arctic and the adjacent subarctic regions as far south as Labrador. The Inuit ...

of other nearby peoples.

The "Innu/Ilnu" consist of two regional tribal groups, with the Innus of Nutashkuan being the southernmost group and the Naskapi

The Naskapi (Nascapi, Naskapee, Nascapee) are an Indigenous people of the Subarctic native to the historical region St'aschinuw (ᒋᑦ ᐊᔅᒋᓄᐤ, meaning 'our Clusivity, nclusiveland'), which was located in present day northern Qu ...

being the northernmost group. Both groups differ in dialect and partly also in their way of life and culture. These differences include:

* the ''Ilnu'', ''Nehilaw'' or "Western/Southern Montagnais" in the south, speak the ''"l"''-dialect (Ilnu-Aimun or Nenueun / Neːhlweːuːn), and

* the ''Innu'' or "Eastern Montagnais" ("Central/Moisie Montagnais", "Eastern/Lower North Shore Montagnais", and "Labrador/North West River Montagnais") live further north; they speak the ''"n"''-dialect (Innu-Aimun)

Both groups are still called "Montagnais" in the official language of Crown–Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada

Crown''–''Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada (CIRNAC; )''Crown–Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada'' is the applied title under the Federal Identity Program; the legal title is Department of Crown''–''Indigenou ...

. The Naskapi ("people beyond the horizon", ᓇᔅᑲᐱ), who live further north, also identify as Innu or ''Iyiyiw''.

Today, about 28,960 people of Innu origin live in various Indian settlement An Indian settlement is a census subdivision outlined by the Canadian government Department of Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada for census

A census (from Latin ''censere'', 'to assess') is the procedure of systematically acqui ...

s and reserves in Quebec and Labrador. To avoid confusion with the Inuit

Inuit (singular: Inuk) are a group of culturally and historically similar Indigenous peoples traditionally inhabiting the Arctic and Subarctic regions of North America and Russia, including Greenland, Labrador, Quebec, Nunavut, the Northwe ...

, who belong to the Eskimo

''Eskimo'' () is a controversial Endonym and exonym, exonym that refers to two closely related Indigenous peoples: Inuit (including the Alaska Native Iñupiat, the Canadian Inuit, and the Greenlandic Inuit) and the Yupik peoples, Yupik (or Sibe ...

an peoples, today only the singular form "Innu/Ilnu" is used for the Innu, members of the large Cree-language family. The plural form of "Innut/Innuat/Ilnuatsh" has been abandoned.

Montagnais, Naskapi or Innu

The people are frequently classified by the geography of their primary locations:

*the ''Neenoilno'', live along the north shore of the Gulf of St. Lawrence, in Quebec; they have historically been referred to by Europeans as ''Montagnais'' (French for "

The people are frequently classified by the geography of their primary locations:

*the ''Neenoilno'', live along the north shore of the Gulf of St. Lawrence, in Quebec; they have historically been referred to by Europeans as ''Montagnais'' (French for "mountain people

Hill people, also referred to as mountain people, is a general term for people who live in the hills and mountains.

This includes all rugged land above and all land (including plateaus) above elevation.

The climate is generally harsh, with s ...

", English pronunciation: ), or ''Innu proper'' (''Nehilaw'' and ''Ilniw'' – "people")

*The ''Naskapi

The Naskapi (Nascapi, Naskapee, Nascapee) are an Indigenous people of the Subarctic native to the historical region St'aschinuw (ᒋᑦ ᐊᔅᒋᓄᐤ, meaning 'our Clusivity, nclusiveland'), which was located in present day northern Qu ...

'' (also known as ''Innu'' and ''Iyiyiw''), live farther north and are less numerous. The Innu recognize several distinctions among their people (e.g. Mushuau Innuat, Maskuanu, Uashau Innuat) based on different regional affiliations and speakers of various dialects of the Innu language.

The word ''Naskapi'' was first recorded by French colonists in the 17th century. They applied it to distant Innu groups who were beyond the reach of Catholic missionary

A missionary is a member of a Religious denomination, religious group who is sent into an area in order to promote its faith or provide services to people, such as education, literacy, social justice, health care, and economic development.Thoma ...

influence. It was particularly applied to those people living in the lands that bordered Ungava Bay

Ungava Bay (; , ; /) is a bay in Nunavut, Canada separating Nunavik (far northern Quebec) from Baffin Island. Although not geographically apparent, it is a marginal sea of the Arctic Ocean. The bay is roughly oval-shaped, about at its widest p ...

and the northern Labrador coast, near the Inuit

Inuit (singular: Inuk) are a group of culturally and historically similar Indigenous peoples traditionally inhabiting the Arctic and Subarctic regions of North America and Russia, including Greenland, Labrador, Quebec, Nunavut, the Northwe ...

communities of northern Quebec and northern Labrador. Gradually it came to refer to the people known today as the Naskapi First Nation.

The Naskapi are traditionally nomad

Nomads are communities without fixed habitation who regularly move to and from areas. Such groups include hunter-gatherers, pastoral nomads (owning livestock), tinkers and trader nomads. In the twentieth century, the population of nomadic pa ...

ic peoples, in contrast with the more sedentary ''Montagnais'', who establish settled territories.

The ''Mushuau Innuat'' (plural), while related to the Naskapi, split off from the tribe in the 1900s. They were subject to a government relocation program at Davis Inlet

Davis Inlet was a Naskapi community in the Provinces and territories of Canada, Canadian province of Newfoundland and Labrador, formerly inhabited by the Mushuau Innu First Nation. It was named for its adjacent fjord, itself named for English ex ...

. Some of the families of the Naskapi Nation of Kawawachikamach have close relatives in the Cree

The Cree, or nehinaw (, ), are a Indigenous peoples of the Americas, North American Indigenous people, numbering more than 350,000 in Canada, where they form one of the country's largest First Nations in Canada, First Nations. They live prim ...

village of Whapmagoostui

Whapmagoostui (, "place of the beluga") is the northernmost Cree village in Quebec, Canada, located at the mouth of the Great Whale River () on the coast of Hudson Bay in Nunavik. About 906 Cree with about 650 Inuit, living in the neighbourin ...

, on the eastern shore of Hudson Bay

Hudson Bay, sometimes called Hudson's Bay (usually historically), is a large body of Saline water, saltwater in northeastern Canada with a surface area of . It is located north of Ontario, west of Quebec, northeast of Manitoba, and southeast o ...

.

Since 1990, the Montagnais people have generally chosen to be officially referred to as the ''Innu'', which means ''human being'' in ''Innu-aimun''. The Naskapi have continued to use the word ''Naskapi''.

Innu communities

Labrador communities

Quebec communities

Conseil tribal Mamit Innuat

About 3,700 membersConseil tribal Mamuitun

Over 23,000 membersKawawachikamach

History

The Innu were possibly the group identified inGreenlandic Norse

Greenlandic Norse is an extinct North Germanic language that was spoken in the Norse settlements of Greenland until their demise in the late 15th century. The language is primarily attested by runic inscriptions found in Greenland. The limited ...

by Norsemen

The Norsemen (or Northmen) were a cultural group in the Early Middle Ages, originating among speakers of Old Norse in Scandinavia. During the late eighth century, Scandinavians embarked on a Viking expansion, large-scale expansion in all direc ...

as ''Skræling

(Old Norse and , plural ) is the name the Norse Greenlanders used for the peoples they encountered in North America (Canada and Greenland). In surviving sources, it is first applied to the Thule people, the proto-Inuit group with whom the Nors ...

s''. They referred to Nitassinan

Nitassinan () is the ancestral homeland of the Innu, an indigenous people of Eastern Quebec and Labrador, Canada. Nitassinan means "our land" in the Innu language. The territory covers the eastern portion of the Labrador peninsula.'' Nitassi ...

as ''Markland

Markland () is the name given to one of three lands on North America's Atlantic shore discovered by Leif Eriksson around 1000 AD. It was located south of Helluland and north of Vinland.

Although it was never recorded to be settled by Norsemen, ...

''.

The Innu were historically allied with neighbouring Atikamekw

The Atikamekw are an Indigenous people in Canada. Their historic territory, ('Our Land'), is in the upper Saint-Maurice River valley of Quebec (about north of Montreal). One of the main communities is Manawan, about northeast of Montreal. ...

, Wolastoqiyik

The Wolastoqiyik, (, also known as the Maliseet or Malecite () are an Algonquian-speaking First Nation of the Wabanaki Confederacy. They are the Indigenous people of the Wolastoq ( Saint John River) valley and its tributaries. Their terri ...

(Maliseet) and Algonquin

Algonquin or Algonquian—and the variation Algonki(a)n—may refer to:

Languages and peoples

*Algonquian languages, a large subfamily of Native American languages in a wide swath of eastern North America from Canada to Virginia

**Algonquin la ...

peoples against their enemies, the Algonquian-speaking Mi'kmaq

The Mi'kmaq (also ''Mi'gmaq'', ''Lnu'', ''Mi'kmaw'' or ''Mi'gmaw''; ; , and formerly Micmac) are an Indigenous group of people of the Northeastern Woodlands, native to the areas of Canada's Atlantic Provinces, primarily Nova Scotia, New Bru ...

and Iroquoian-speaking Five Nations of the Iroquois

The Iroquois ( ), also known as the Five Nations, and later as the Six Nations from 1722 onwards; alternatively referred to by the Endonym and exonym, endonym Haudenosaunee ( ; ) are an Iroquoian languages, Iroquoian-speaking Confederation#Ind ...

Confederacy (known as ''Haudenosaunee''. During the Beaver Wars

The Beaver Wars (), also known as the Iroquois Wars or the French and Iroquois Wars (), were a series of conflicts fought intermittently during the 17th century in North America throughout the Saint Lawrence River valley in Canada and the Great L ...

(1609–1701), the Iroquois repeatedly invaded the Innu territories from their homelands south of the Great Lakes

The Great Lakes, also called the Great Lakes of North America, are a series of large interconnected freshwater lakes spanning the Canada–United States border. The five lakes are Lake Superior, Superior, Lake Michigan, Michigan, Lake Huron, H ...

. They took women and young males as captive slaves, and plundered their hunting grounds in search of more furs. Since these raids were made by the Iroquois with unprecedented brutality, the Innu themselves adopted the torment, torture, and cruelty of their enemies.

The Naskapi, on the other hand, usually had to confront the southward advancing Inuit in the east of the peninsula.

Innu oral tradition

Oral tradition, or oral lore, is a form of human communication in which knowledge, art, ideas and culture are received, preserved, and transmitted orally from one generation to another.Jan Vansina, Vansina, Jan: ''Oral Tradition as History'' (19 ...

describes the original encounters of the Innu and the French explorers led by Samuel de Champlain

Samuel de Champlain (; 13 August 1574#Fichier]For a detailed analysis of his baptismal record, see #Ritch, RitchThe baptism act does not contain information about the age of Samuel, neither his birth date nor his place of birth. – 25 December ...

as fraught with distrust. Neither group understood the language of the other, and the Innu were concerned about the motives of the French explorers.

The French asked permission to settle on the Innu's coastal land, which the Innu called ''Uepishtikueiau''. This eventually developed as Quebec City

Quebec City is the capital city of the Provinces and territories of Canada, Canadian province of Quebec. As of July 2021, the city had a population of 549,459, and the Census Metropolitan Area (including surrounding communities) had a populati ...

. According to oral tradition, the Innu at first declined their request. The French demonstrated their ability to farm wheat

Wheat is a group of wild and crop domestication, domesticated Poaceae, grasses of the genus ''Triticum'' (). They are Agriculture, cultivated for their cereal grains, which are staple foods around the world. Well-known Taxonomy of wheat, whe ...

on the land and promised they would share their bounty with the Innu in the future, which the Innu accepted.

Two distinct versions of the oral history describe the outcome. In the first, the French used gifts of farmed food and manufactured goods to encourage the Innu to become dependent on them. Then, the French changed it to a mercantile relationship: trading these items to the Innu in exchange for furs. When the nomadic Innu went inland for the winter, the French increased the size and population of their settlement considerably, eventually completely displacing the Innu.

The second, and more widespread, version of the oral history describes a more immediate conflict. In this version, the Innu taught the French how to survive in their traditional lands. Once the French had learned enough to survive on their own, they began to resent the Innu. The French began to attack the Innu, who retaliated in an attempt to reclaim their ancestral territory. The Innu had a disadvantage in numbers and weaponry, and eventually began to avoid the area rather than risk further defeat. During this conflict, the French colonists took many Innu women as wives. French women did not immigrate to New France in the early period.

French explorer Samuel de Champlain eventually became involved in the Innu's conflict with the Iroquois, who were ranging north from their traditional territory around the Great Lakes in present-day New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

New York may also refer to:

Places United Kingdom

* ...

and Pennsylvania. On July 29, 1609, at Ticonderoga or Crown Point, New York

Crown Point is a town in Essex County, New York, United States, located on the west shore of Lake Champlain. The population was 2,024 at the 2010 census. The name of the town is a direct translation of the original French name, .

The town is on ...

, (historians are not sure which of these two places), Champlain and his party encountered a group of Iroquois, likely Mohawk, who were the easternmost tribe of the Five Nations of the Iroquois Confederacy. A battle began the next day. As two hundred Iroquois advanced on Champlain's position, a native guide pointed out the three enemy chiefs to the French. According to legend, Champlain fired his arquebus

An arquebus ( ) is a form of long gun that appeared in Europe and the Ottoman Empire during the 15th century. An infantryman armed with an arquebus is called an arquebusier.

The term ''arquebus'' was applied to many different forms of firearms ...

and killed two of the Mohawk chiefs with one shot; one of his men shot and killed the third. The Mohawk reportedly fled the scene. Although the French also traded extensively with the Mohawk and other Iroquois, and converted some to Catholicism, they also continued to have armed conflicts with them.

Historical bands

The southern bands of the Montagnais-Naksapi were encountered by Europeans early in the seventeenth century while the northern ones, except for some on James Bay, were not well known until the nineteenth century. The following are bands of the Montagnais-Naksapi in the 17th century: * Bersimis, around the Bersimis River * Chicoutimi, north ofChicoutimi

Chicoutimi ( , ) is the most populous borough (arrondissement) of the city of Saguenay in Quebec, Canada.

It is situated at the confluence of the Saguenay and Chicoutimi rivers. During the 20th century, it became the main administrative and ...

* Chisedec, around Seven Islands and around the Moise River

* Escoumains, around the Escoumains River

* Godbout, around the Godbout River

* Mistassini, around Lake Mistassini

Lake Mistassini () is the largest natural lake by surface area in the province of Quebec, Canada, with a total surface area of approximately and a net area (water surface area only) of . It is located in the Jamésie region of the province, app ...

* Nichikun, around Nichikun Lake

* Ouchestigouetch, at the heads of Manikuagan and Kaniapiskau Rivers.

* Oumamiwek (or Ste. Marguerite), west of the Ste. Marguerite River

* Papinachois, at the head of the Bersimis River and east of it

* Tadousac, west of the lower Saguenay River

__NOTOC__

The Saguenay River (, ) is a major river of Quebec, Canada.

It drains Lac Saint-Jean in the Laurentian Highlands, leaving at Alma and running east; the city of Saguenay is located on the river. It drains into the Saint Lawrence River. ...

By 1850, the Chisedec, Oumamiwek, and Papinachois had disappeared or been renamed, and many new bands in the north of Nitassinan were discovered:

* Barren Ground, on the middle course of the George River

* Big River, around the Great Whale and Fort George River

A fortification (also called a fort, fortress, fastness, or stronghold) is a military construction designed for the defense of territories in warfare, and is used to establish rule in a region during peacetime. The term is derived from Lati ...

s

* Davis Inlet, south of the Barren Ground band

* Eastmain, north of the Eastmain River

The Eastmain River, formerly written East Main, is a river in west central Quebec. It rises in central Quebec and flows west to James Bay, draining an area of . The First Nations Cree village of Eastmain is located beside the mouth.

Name

Eastm ...

.

* Kaniapiskau, at the head of the Kaniapiskau River

* Michikamau, around Michikamau Lake

* Mingan, on the Mingan River

* Musquaro (or Romaine), on the Olomanoshibo River

* Natashkwan, on the Natashkwan River

* Northwest River, north of Hamilton Inlet

__NOTOC__

Hamilton Inlet is a fjord-like inlet of Groswater Bay on the Labrador coast of the Canadian province of Newfoundland and Labrador. Together with Lake Melville, it forms its province's largest estuary, extending over inland to Happy V ...

and on the Northwest River

* Petisikapau, in the country around Petisikapau Lake

* Rupert House, around Rupert Bay

Rupert Bay is a large bay located on the south-east shore of James Bay, in Canada. Although the coast is part of the province of Quebec, the waters of the bay are under jurisdiction of the territory of Nunavut.

Geography

This bay has a width of ...

and the Rupert River

The Rupert River is a river in Quebec, Canada. From its headwaters in Lake Mistassini, the largest natural lake in Quebec, it flows west into Rupert Bay on James Bay. The Rupert drains an area of .

There is some extremely large whitewater on ...

* St. Augustin, on the St. Augustin River

* Shelter Bay, around modern-day Shelter Bay

* Ungava, southwest of the Ungava Bay

Ungava Bay (; , ; /) is a bay in Nunavut, Canada separating Nunavik (far northern Quebec) from Baffin Island. Although not geographically apparent, it is a marginal sea of the Arctic Ocean. The bay is roughly oval-shaped, about at its widest p ...

* Waswanipi, on the Waswanipi River

The Waswanipi River is a tributary of Matagami Lake. The Waswanipi River flows in the Municipality of Eeyou Istchee Baie-James in the administrative region of Nord-du-Québec, in Quebec, Canada.

Geography

The main hydrographic slopes adjacent ...

* White Whale River, between Lake Minto and Little Whale River

The Little Whale River (; ) is a river in Nunavik, Quebec, Canada. With an area of , it is ranked as the 35th largest river basin in Quebec.

The Cree named a segment of the Little Whale River near its mouth as ''Wâpamekustus'', which is similar ...

and eastward to the Kaniapiskau River

Present status

The Innu ofLabrador

Labrador () is a geographic and cultural region within the Canadian province of Newfoundland and Labrador. It is the primarily continental portion of the province and constitutes 71% of the province's area but is home to only 6% of its populatio ...

and those living on the north shore of the Gulf of St. Lawrence in the Canadian Shield

The Canadian Shield ( ), also called the Laurentian Shield or the Laurentian Plateau, is a geologic shield, a large area of exposed Precambrian igneous and high-grade metamorphic rocks. It forms the North American Craton (or Laurentia), th ...

region have never officially ceded their territory to Canada by way of treaty or other agreement. But, as European-Canadians began widespread forest and mining operations at the turn of the 20th century, the Innu became increasingly settled in coastal communities and in the interior of Quebec. The Canadian

Canadians () are people identified with the country of Canada. This connection may be residential, legal, historical or cultural. For most Canadians, many (or all) of these connections exist and are collectively the source of their being ''C ...

and provincial governments, the Catholic

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

, Moravian, and Anglican

Anglicanism, also known as Episcopalianism in some countries, is a Western Christianity, Western Christian tradition which developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the ...

churches, all encouraged the Innu to settle in more permanent, majority-style communities, in the belief that their lives would improve with this adaptation. This coercive assimilation resulted in the Innue giving up some traditional activities (hunting, trapping

Animal trapping, or simply trapping or ginning, is the use of a device to remotely catch and often kill an animal. Animals may be trapped for a variety of purposes, including for meat, fur trade, fur/feathers, sport hunting, pest control, and w ...

, fishing). Because of these social disruptions and the systemic disadvantages faced by Indigenous peoples, community life in the permanent settlements often became associated with high levels of substance abuse

Substance misuse, also known as drug misuse or, in older vernacular, substance abuse, is the use of a drug in amounts or by methods that are harmful to the individual or others. It is a form of substance-related disorder, differing definition ...

, domestic violence

Domestic violence is violence that occurs in a domestic setting, such as in a marriage

Marriage, also called matrimony or wedlock, is a culturally and often legally recognised union between people called spouses. It establishes r ...

, and suicide

Suicide is the act of intentionally causing one's own death.

Risk factors for suicide include mental disorders, physical disorders, and substance abuse. Some suicides are impulsive acts driven by stress (such as from financial or ac ...

among the Innu.

Labrador Innu organizations and land claims

In 1999,Survival International

Survival International is a human rights organisation formed in 1969, a London based charity that campaigns for the collective rights of Indigenous, tribal and uncontacted peoples.

The organisation's campaigns generally focus on tribal people ...

published a study of the Innu communities of Labrador. It assessed the adverse effects of the Canadian government's relocating the people far from their ancestral lands and preventing them from practising their ancient way of life.

The Innu people of Labrador formally organized the Naskapi Montagnais Innu Association in 1976 to protect their rights, lands, and way of life against industrialization and other outside forces. The organization changed its name to the Innu Nation in 1990 and functions today as the governing body of the Labrador Innu. The group has won recognition for its members as status Indians

The Indian Register is the official record of people registered under the ''Indian Act'' in Canada, called status Indians or ''registered Indians''. People registered under the ''Indian Act'' have rights and benefits that are not granted to othe ...

under Canada's ''Indian Act

The ''Indian Act'' () is a Canadian Act of Parliament that concerns registered Indians, their bands, and the system of Indian reserves. First passed in 1876 and still in force with amendments, it is the primary document that defines how t ...

'' in 2002 and is currently involved in land claim and self-governance negotiations with the federal and provincial governments.

In addition to the Innu Nation, residents at both Natuashish and Sheshatshiu elect Band Councils to represent community concerns. The chiefs of both councils sit on the Innu Nation's board of directors and the three groups work in cooperation with one another.

The Innu Nation's efforts to raise awareness about the environmental impacts of a mining project in Voisey's Bay

Voisey's Bay is a bay of the Atlantic Ocean in Labrador, Canada. The bay is located south of the community of Nain. The bay is heavily indented with numerous inlets and islands and is extremely rocky. It is the site of the Voisey's Bay Mine.

...

were documented in Marjorie Beaucage's 1997 film ''Ntapueu ... i am telling the truth.''

Davis Inlet, Labrador

In the 1999 study of Innu communities in Labrador, Survival International concluded that government policies violated contemporaryinternational law

International law, also known as public international law and the law of nations, is the set of Rule of law, rules, norms, Customary law, legal customs and standards that State (polity), states and other actors feel an obligation to, and generall ...

in human rights, and drew parallels with the treatment of Tibetans by the People's Republic of China. According to the study, from 1990 to 1997, the Innu community of Davis Inlet

Davis Inlet was a Naskapi community in the Provinces and territories of Canada, Canadian province of Newfoundland and Labrador, formerly inhabited by the Mushuau Innu First Nation. It was named for its adjacent fjord, itself named for English ex ...

had a suicide rate more than twelve times the Canadian average, and well over three times the rate often observed in isolated northern villages.''Canada's Tibet: The Killing of the Innu,'' a report from Survival International (PDF file)/ref> By 2000, the Innu island community of Davis Inlet asked the Canadian government to assist with a local

addiction

Addiction is a neuropsychological disorder characterized by a persistent and intense urge to use a drug or engage in a behavior that produces natural reward, despite substantial harm and other negative consequences. Repetitive drug use can ...

public health crisis. At their request, the community was relocated to a nearby mainland site, now known as ''Natuashish''. At the same time, the Canadian government created the Natuashish and Sheshatshiu band councils under the ''Indian Act''.

Kawawachikamach, Quebec

Naskapi Nation of Kawawachikamach, Quebec, signed a comprehensive land claims settlement, the '' Northeastern Quebec Agreement''; they did so in 1978. As a consequence, the Naskapi of Kawawachikamach are no longer subject to certain provisions of the ''Indian Act''. All the Innu communities of Quebec are still subject to the Act.New York Power Authority controversy

TheNew York Power Authority

The New York Power Authority (NYPA) is a public benefit corporation owned by the State of New York and is the largest state public power utility in the United States. It provides some of the lowest-cost electricity in the nation, operating 16 ge ...

's proposed contract in 2009 with the province of Quebec

Quebec is Canada's List of Canadian provinces and territories by area, largest province by area. Located in Central Canada, the province shares borders with the provinces of Ontario to the west, Newfoundland and Labrador to the northeast, ...

to buy power from its extensive hydroelectric dam

Hydroelectricity, or hydroelectric power, is Electricity generation, electricity generated from hydropower (water power). Hydropower supplies 15% of the world's electricity, almost 4,210 TWh in 2023, which is more than all other Renewable energ ...

facilities has generated controversy, because it was dependent on construction of a new dam complex and transmission lines that would have interfered with the traditional ways of the Innu.Katrina Kieltyka, "Sierra Club fighting plan to buy Canadian power: Say hydroelectric dams would harm indigenous people," ''Legislative Gazette'', March 16, 2009, p. 21, available a''Legislative Gazette'' archives

(.pdf file). Retrieved March 20, 2009. According to the

Sierra Club

The Sierra Club is an American environmental organization with chapters in all 50 U.S. states, Washington, D.C., Washington D.C., and Puerto Rico. The club was founded in 1892, in San Francisco, by preservationist John Muir. A product of the Pro ...

:

The Innu community, the Sierra Club, and the National Lawyers Guild

The National Lawyers Guild (NLG) is a progressive public interest association of lawyers, law students, paralegals, jailhouse lawyers, law collective members, and other activist legal workers, in the United States. The group was founded in 193 ...

are fighting to prevent this proposed contract, which would have to be approved by New York's Governor, under his regulatory authority. The problem is that construction of required electric transmission

Electricity is the set of physical phenomena associated with the presence and motion of matter possessing an electric charge. Electricity is related to magnetism, both being part of the phenomenon of electromagnetism, as described by Maxwel ...

lines would hinder the Innu's hunting-gathering-fishing lifestyle:

Chief Grégoire's comments at a press conference in Albany, New York

Albany ( ) is the List of capitals in the United States, capital city of the U.S. state of New York (state), New York. It is located on the west bank of the Hudson River, about south of its confluence with the Mohawk River. Albany is the oldes ...

were translated, but whether from French or Innu-aimun

Innu-aimun or Montagnais is an Algonquian language spoken by over 10,000 Innu in Labrador and Quebec in Eastern Canada. It is a member of the Cree–Montagnais–Naskapi dialect continuum and is spoken in various dialects depending on the com ...

is not clear.

Natuashish and Sheshatshiu, Newfoundland and Labrador

Innu have only been in Sheshatshiu since furtrading post

A trading post, trading station, or trading house, also known as a factory in European and colonial contexts, is an establishment or settlement where goods and services could be traded.

Typically a trading post allows people from one geogr ...

s were established by the Hudson's Bay Company

The Hudson's Bay Company (HBC), originally the Governor and Company of Adventurers of England Trading Into Hudson’s Bay, is a Canadian holding company of department stores, and the oldest corporation in North America. It was the owner of the ...

in North West River in the mid-1700s and only in Davis Inlet / Natuashish since 1771, when the Moravian Church set up the first mission at Nuneingoak on the Labrador coast. Danny Williams, the then Premier of Newfoundland and Labrador

The premier of Newfoundland and Labrador is the first minister and head of government for the Canadian province of Newfoundland and Labrador. Since 1949, the premier's duties and office has been the successor to the ministerial position of the p ...

struck a deal on September 26, 2008, with Labrador's Innu to permit construction of Muskrat Falls Generating Station

The Muskrat Falls Generating Station is a hydroelectric generating station on the Churchill River in Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada. It is located downstream of the Churchill Falls Generating Station. The station at Muskrat Falls has a capaci ...

, a hydroelectric megaproject

A megaproject is an extremely large-scale construction and investment project.

A more general definition is "Megaprojects are temporary endeavours (i.e. projects) characterised by: large investment commitment, vast complexity (especially in org ...

to proceed on the proposed Lower Churchill site. They also negotiated compensation for another project on the Upper Churchill, where large tracts of traditional Innu hunting lands were flooded.

Culture

Ethnobotany

Ethnobotany is an interdisciplinary field at the interface of natural and social sciences that studies the relationships between humans and plants. It focuses on traditional knowledge of how plants are used, managed, and perceived in human socie ...

The Innu people grate the inner bark of ''Abies balsamea

''Abies balsamea'' or balsam fir is a North American fir, native to most of eastern and central Canada (Newfoundland (island), Newfoundland west to central Alberta) and the northeastern United States (Minnesota east to Maine, and south in the Ap ...

'' (balsam fir) and eat it to benefit the diet.

Traditional crafts

Traditional Innu craft is demonstrated in the Innu tea doll. These children's toys originally served a dual purpose for nomadic Innu tribes. When travelling vast distances over challenging terrain, the people left nothing behind. They believed that "Crow" would take it away. Everyone, including young children, helped to transport essential goods. Innu women made intricate dolls fromcaribou

The reindeer or caribou (''Rangifer tarandus'') is a species of deer with circumpolar distribution, native to Arctic, subarctic, tundra, boreal, and mountainous regions of Northern Europe, Siberia, and North America. It is the only represe ...

hides and scraps of cloth. They filled the dolls with tea and gave them to young girls to carry on long journeys. The girls could play with the dolls while also carrying important goods. Every able-bodied person carried something. Men generally carried the heavier bags and women would carry young children.

Traditional clothing, style and accessories

Men wore caribou pants and boots with a buckskin long shirt, all made by women. With the introduction of trade cloth from the French and English, people began replacing the buckskin shirts with ones made of cloth. Most still wore boots and pants made from caribou hide. Women wore long dresses of buckskin. Contemporary Innu women have often replaced these with manufactured pants and jackets. Women traditionally wore their hair long or in two coils. Men wore theirs long. Both genders wore necklaces made of bone and bead. Smoke pipes were used by both genders, marked for women as shorter. If a man killed a bear, it was a sign of joy and initiation into adulthood and the man would wear a necklace made from the bear's claws.Housing

The houses of the Montagnais were cone shaped. The Naskapi made long, domed houses covered in caribou hides. These days thehearth

A hearth () is the place in a home where a fire is or was traditionally kept for home heating and for cooking, usually constituted by a horizontal hearthstone and often enclosed to varying degrees by any combination of reredos (a low, partial ...

is a metal stove in the centre of the house.

Traditional foods

Animals traditionally eaten includedmoose

The moose (: 'moose'; used in North America) or elk (: 'elk' or 'elks'; used in Eurasia) (''Alces alces'') is the world's tallest, largest and heaviest extant species of deer and the only species in the genus ''Alces''. It is also the tal ...

, caribou, porcupine

Porcupines are large rodents with coats of sharp Spine (zoology), spines, or quills, that protect them against predation. The term covers two Family (biology), families of animals: the Old World porcupines of the family Hystricidae, and the New ...

, rabbits, marten

A marten is a weasel-like mammal in the genus ''Martes'' within the subfamily Guloninae, in the family Mustelidae. They have bushy tails and large paws with partially retractile claws. The fur varies from yellowish to dark brown, depending on ...

, woodchuck

The groundhog (''Marmota monax''), also known as the woodchuck, is a rodent of the family Sciuridae, belonging to the group of large ground squirrels known as marmots.

A lowland creature of North America, it is found through much of the Easte ...

, squirrel; Canada goose

The Canada goose (''Branta canadensis''), sometimes called Canadian goose, is a large species of goose with a black head and neck, white cheeks, white under its chin, and a brown body. It is native to the arctic and temperate regions of North A ...

, snow goose

The snow goose (''Anser caerulescens'') is a species of goose native to North America. Both white and dark morphs exist, the latter often known as blue goose. Its name derives from the typically white plumage. The species was previously placed ...

, brants, ducks, teal

alt=American teal duck (male), Green-winged teal (male)

Teal is a greenish-blue color. Its name comes from that of a bird—the Eurasian teal (''Anas crecca'')—which presents a similarly colored stripe on its head. The word is often used ...

, loon

Loons (North American English) or divers (British English, British / Irish English) are a group of aquatic birds found in much of North America and northern Eurasia. All living species of loons are members of the genus ''Gavia'', family (biolog ...

s, spruce grouse, woodcock

The woodcocks are a group of seven or eight very similar living species of sandpipers in the genus ''Scolopax''. The genus name is Latin for a snipe or woodcock, and until around 1800 was used to refer to a variety of waders. The English name ...

, snipe

A snipe is any of about 26 wading bird species in three genera in the family Scolopacidae. They are characterized by a very long, slender bill, eyes placed high on the head, and cryptic/ camouflaging plumage. ''Gallinago'' snipe have a nearly ...

, passenger pigeon

The passenger pigeon or wild pigeon (''Ectopistes migratorius'') is an bird extinction, extinct species of Columbidae, pigeon that was endemic to North America. Its common name is derived from the French word ''passager'', meaning "passing by" ...

s, ptarmigan

''Lagopus'' is a genus of birds in the grouse subfamily commonly known as ptarmigans (). The genus contains four living species with numerous described subspecies, all living in tundra or cold upland areas.

Taxonomy and etymology

The genus ''L ...

; whitefish, lake trout

The lake trout (''Salvelinus namaycush'') is a freshwater Salvelinus, char living mainly in lakes in Northern North America. Other names for it include mackinaw, namaycush, lake char (or charr), touladi, togue, laker, and grey trout. In Lake Sup ...

, salmon, Arctic char

The Arctic char or Arctic charr (''Salvelinus alpinus'') is a cold-water fish in the family Salmonidae, native to alpine lakes, as well as Arctic and subarctic coastal waters in the Holarctic realm, Holarctic.

Distribution and habitat

It Spaw ...

, seal

Seal may refer to any of the following:

Common uses

* Pinniped, a diverse group of semi-aquatic marine mammals, many of which are commonly called seals, particularly:

** Earless seal, also called "true seal"

** Fur seal

** Eared seal

* Seal ( ...

(''naskapi'') pike, walleye

The walleye (''Sander vitreus'', Synonym (taxonomy), synonym ''Stizostedion vitreum''), also called the walleyed pike, yellow pike, yellow pikeperch or yellow pickerel, is a freshwater perciform fish native to most of Canada and to the Northern ...

, suckerfish (''Catostomidae''), sturgeon

Sturgeon (from Old English ultimately from Proto-Indo-European language, Proto-Indo-European *''str̥(Hx)yón''-) is the common name for the 27 species of fish belonging to the family Acipenseridae. The earliest sturgeon fossils date to the ...

, catfish

Catfish (or catfishes; order (biology), order Siluriformes or Nematognathi) are a diverse group of ray-finned fish. Catfish are common name, named for their prominent barbel (anatomy), barbels, which resemble a cat's whiskers, though not ...

, lamprey

Lampreys (sometimes inaccurately called lamprey eels) are a group of Agnatha, jawless fish comprising the order (biology), order Petromyzontiformes , sole order in the Class (biology), class Petromyzontida. The adult lamprey is characterize ...

, and smelt. Fish were eaten roasted or smoke-dried. Moose meat and several types of fish were also smoked. Oat bannock, introduced by the French in the 16th century, became a staple and Indigenous bannock is still eaten today. Meat was eaten frozen, raw or roasted, and caribou was sometimes boiled in a stew. Pemmican

Pemmican () (also pemican in older sources) is a mixture of tallow, dried meat, and sometimes dried berries. A calorie-rich food, it can be used as a key component in prepared meals or eaten raw. Historically, it was an important part of indigeno ...

was made with moose or caribou.

Plants traditionally eaten included raspberries, blueberries, strawberries, cherries, wild grape Wild grape may refer to:

* ''Vitis'' species; specially ''Vitis vinifera'' subsp. ''sylvestris'' (the wild ancestor of ''Vitis vinifera''), ''Vitis californica'' (California wild grape), '' Vitis girdiana'' (desert wild grape), and '' Vitis ripari ...

s, hazelnut

The hazelnut is the fruit of the hazel tree and therefore includes any of the nuts deriving from species of the genus '' Corylus'', especially the nuts of the species ''Corylus avellana''. They are also known as cobnuts or filberts according to ...

s, crab apples, red martagon bulbs, Indian potato, and maple-tree sap

Sap is a fluid transported in the xylem cells (vessel elements or tracheids) or phloem sieve tube elements of a plant. These cells transport water and nutrients throughout the plant.

Sap is distinct from latex, resin, or cell sap; it is a s ...

for sweetening. Cornmeal

Maize meal is a meal (coarse flour) ground from dried maize. It is a common staple food and is ground to coarse, medium, and fine consistencies, but it is not as fine as wheat flour can be.Herbst, Sharon, ''Food Lover's Companion'', Third Editi ...

was traded with other First Nations peoples

There is no generally accepted definition of Indigenous peoples, although in the 21st century the focus has been on self-identification, cultural difference from other groups in a state, a special relationship with their traditional territ ...

, such as the Iroquois, Algonquin, and Abenaki

The Abenaki ( Abenaki: ''Wαpánahki'') are Indigenous people of the Northeastern Woodlands of Canada and the United States. They are an Algonquian-speaking people and part of the Wabanaki Confederacy. The Eastern Abenaki language was pred ...

, and made into apon (cornbread

Cornbread is a quick bread made with cornmeal, associated with the cuisine of the Southern United States, with origins in Native American cuisine. It is an example of batter bread. Dumplings and pancakes made with finely ground cornmeal are st ...

), which sometimes also included oat or wheat flour when it became available. Pine needle tea was meant to keep away infections and colds resulting from the harsh weather.

Buckskin

Traditionally, buckskin leather was a most important material used for clothing, boots, moccasins, house covers and storage. Women prepared the hides and many of the products made from it. They scraped the hides to remove all fur, then left them outside to freeze. The next step was to stretch the hide on a frame. They rubbed it with a mixture of animal brain and pine needle tea to soften it. The dampened hide was formed into a ball and left overnight. In the morning, it would be stretched again, then placed over a smoker to smoke and tan it. The hide was left overnight. The finished hide was called buckskin.Mythology

The oral traditions of the Innu are noted as similar to those of other Cree-speaking cultures. Of particular relevance is Tshakapesh, alunar

Lunar most commonly means "of or relating to the Moon".

Lunar may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* ''Lunar'' (series), a series of video games

* "Lunar" (song), by David Guetta

* "Lunar", a song by Priestess from the 2009 album ''Prior t ...

folk hero.

The spirits they believed in are Caribou Master

The Caribou Master, variously known as Kanipinikassikueu, Katipenimitak, Papakashtshishk, or Caribou Man is a powerful spirit in traditional Innu religion and mythology, an indigenous people of present-day Canada and Quebec. In the myth, an Innu ma ...

, Atshen, and Matshishkapeu.

Film and television

The Innu people were profiled in '' Carcajou et le péril blanc (Kauapishit Miam Kuakuatshen Etentakuess)'', a documentary film series by Arthur Lamothe which were among the first films in the history of cinema to depict indigenous peoples speaking their own languages. Other important later films set in Innu communities have included the narrative feature films '' Le Dep'', '' Mesnak'' and ''Kuessipan

''Kuessipan'' is a Canadian drama film, directed by Myriam Verreault and released in 2019. An adaptation of Naomi Fontaine's eponymous novel, the script was co-written by Fontaine and Verreault. Its plot centres on Mikuan (Sharon Fontaine-Ishpat ...

'', and the documentary films '' Innu Nikamu: Resist and Sing'' and '' Call Me Human''.

Transportation

In traditional Innu communities, people walked or usedsnowshoe

Snowshoes are specialized outdoor gear for walking over snow. Their large footprint spreads the user's weight out and allows them to travel largely on top of rather than through snow. Adjustable bindings attach them to appropriate winter footw ...

s. While people still walk and use snowshoes where necessary for hunting or trapping, many Innu communities rely heavily on trucks, SUVs, and cars; in northern Innu communities, people use snowmobile

A snowmobile, also known as a snowmachine (chiefly Alaskan), motor sled (chiefly Canadian), motor sledge, skimobile, snow scooter, or simply a sled is a motorized vehicle designed for winter travel and recreation on snow.

Their engines normally ...

s for hunting and general transportation.

Notable people

* An Antane-Kapesh, writer *Joséphine Bacon

Joséphine Bacon (born April 23, 1947), is an Innu poet from Pessamit in Quebec. She publishes in French and Innu-aimun. She has also worked as a translator, community researcher, documentary filmmaker, curator and as a songwriter for Chloé Sa ...

, poet

* Jani Bellefleur-Kaltush, filmmaker

* Bernard Cleary, politician"Meet Canada's first Innu MP, the Bloc's Bernard Cleary". ''The Hill Times

''The Hill Times'' is a Canadian twice-weekly newspaper and daily news website, published in Ottawa, Ontario, which covers the Parliament of Canada, the federal government, and other federal political news. Founded in 1989 by Ross Dickson and Jim ...

'', November 8, 2004.

*Naomi Fontaine

Naomi Fontaine is a Canadians, Canadian writer from Quebec, noted as one of the most prominent First Nations in Canada, First Nations writers in contemporary francophone Canadian literature. She is a member of the Innu nation.

Biography

A member ...

, writer

* Sharon Fontaine-Ishpatao, actressSylvain Turcotte"Sharon Fontaine-Ishpatao se plaît à jouer"

''Le Nord-Côtier'', August 2, 2022. *

Jonathan Genest-Jourdain

Jonathan Genest-Jourdain (born July 16, 1979) is a Canadian politician from Quebec. Genest-Jourdain served as the New Democratic Party Member of Parliament for Manicouagan and as a member of the Official Opposition Shadow Cabinet in the 41st C ...

, politician

*Michel Jean

Michel Jean is a Canadian television journalist and author. He was the weekend anchor of ''TVA Nouvelles'' on TVA until retiring from the network in 2024, and was formerly an anchor on TVA's newsmagazine ''JE'' and for the 24-hour news channel ...

, journalist and writer

* Jean-Luc Kanapé, conservationist and actor

*Natasha Kanapé Fontaine

Natasha Kanapé Fontaine (born 1991) is an Innu poet and actress. Born in Pessamit, Quebec, Fontaine first became noticed in 2012 as part of the Montreal poetry scene. Her first poetry collection, ''Do Not Enter My Soul in Your Shoes'', earned h ...

, writer

* Kanen, musician

* Carole Labarre, writer

* Matiu, musician

*Claude McKenzie

Claude McKenzie (born 1967 in Schefferville, Quebec)Claude McKenzie

at Les filles électriques

, musician (at Les filles électriques

Kashtin

Kashtin were a Canadians, Canadian folk rock duo in the 1980s and 1990s, one of the most commercially successful and famous musical groups in First Nations in Canada, First Nations history.

Career

The band was formed in 1984 by Claude McKenzie a ...

)

*Geneviève McKenzie-Sioui

Geneviève McKenzie-Sioui, sometimes performing under the name Shanipiap, is an Innu musician, writer, television creator, and activist in Quebec. Born in Matimekosh in 1956, she later relocated to Wendake, Quebec, Wendake. She is a singer-songwr ...

, musician

*Rita Mestokosho

Rita Mestokosho (born 1966 in Ekuanitshit Innu reserve in Quebec, in the Côte-Nord region) is an Innu writer and poet, councillor for culture and education in the Innu nation.

Biography

Indigenous activist

Born in the small Innu village ...

, poet

* Peter Penashue, politician

* Scott-Pien Picard, musician

* Laurie Rousseau-Nepton, astrophysicist

*Shauit

Shauit is a Canadian singer-songwriter, who blends traditional First Nations music, primarily in the Innu-aimun language, with pop-rock and reggae music.

Originally from Maliotenam, Quebec, he is the son of an Acadian father and an Innu

...

, musician

*Florent Vollant

Florent Vollant (born August 10, 1959 in Labrador) is a Canadian singer-songwriter. An Innu from Maliotenam, Quebec, he was half of the popular folk music duo Kashtin, one of the most significant musical groups in First Nations history. He has sub ...

, musician (Kashtin

Kashtin were a Canadians, Canadian folk rock duo in the 1980s and 1990s, one of the most commercially successful and famous musical groups in First Nations in Canada, First Nations history.

Career

The band was formed in 1984 by Claude McKenzie a ...

)

See also

* Violence against indigenous women *Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women

Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women are instances of violence against Indigenous women in Canada and the United States, notably those in the First Nations in Canada and Native American communities, but also amongst other Indigenous peoples s ...

Notes

Citations

General bibliography

* Rogers, Edward S., and Leacock, Eleanor (1981). "Montagnais-Naskapi". In J. Helm (Ed.), ''Handbook of North American Indians

The ''Handbook of North American Indians'' is a series of edited scholarly and reference volumes in Native American studies, published by the Smithsonian Institution beginning in 1978. Planning for the handbook series began in the late 1960s and ...

: Subarctic'' (Vol. 6, pp. 169–189). Washington: Smithsonian Institution.

External links

Official website of the Innu Nation of Labrador.

Official website of the Naskapi Nation of Kawawachikamach, Quebec

{{Authority control Algonquian peoples Algonquian ethnonyms Ethnic groups in Canada Indigenous peoples in Canada