Ice XII on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Variations in pressure and temperature give rise to different phases of

Variations in pressure and temperature give rise to different phases of

The accepted

The accepted

Ice from a theorized superionic water may possess two crystalline structures. At pressures in excess of such ''superionic ice'' would take on a

Ice from a theorized superionic water may possess two crystalline structures. At pressures in excess of such ''superionic ice'' would take on a

Ice, water, and

Ice, water, and

The

The

This estimate is naive, as it assumes the six out of 16 hydrogen configurations for oxygen atoms in the second set can be independently chosen, which is false. More complex methods can be employed to better approximate the exact number of possible configurations, and achieve results closer to measured values. Nagle (1966) used a series summation to obtain .

As an illustrative example of refinement, consider the following way to refine the second estimation method given above. According to it, six water molecules in a hexagonal ring would allow configurations. However, by explicit enumeration, there are actually 730 configurations. Now in the lattice, each oxygen atom participates in 12 hexagonal rings, so there are 2N rings in total for N oxygen atoms, or 2 rings for each oxygen atom, giving a refined result of .

This estimate is naive, as it assumes the six out of 16 hydrogen configurations for oxygen atoms in the second set can be independently chosen, which is false. More complex methods can be employed to better approximate the exact number of possible configurations, and achieve results closer to measured values. Nagle (1966) used a series summation to obtain .

As an illustrative example of refinement, consider the following way to refine the second estimation method given above. According to it, six water molecules in a hexagonal ring would allow configurations. However, by explicit enumeration, there are actually 730 configurations. Now in the lattice, each oxygen atom participates in 12 hexagonal rings, so there are 2N rings in total for N oxygen atoms, or 2 rings for each oxygen atom, giving a refined result of .

Ice XI is the hydrogen-ordered form of the ordinary form of ice. The total

Ice XI is the hydrogen-ordered form of the ordinary form of ice. The total

In 2016, the discovery of a new form of ice was announced. Characterized as a "porous water ice metastable at atmospheric temperatures", this new form was discovered by taking a filled ice and removing the non-water components, leaving the crystal structure behind, similar to how ice XVI, another porous form of ice, was synthesized from a

In 2016, the discovery of a new form of ice was announced. Characterized as a "porous water ice metastable at atmospheric temperatures", this new form was discovered by taking a filled ice and removing the non-water components, leaving the crystal structure behind, similar to how ice XVI, another porous form of ice, was synthesized from a

New Scientist,01 September 2010, Magazine issue 2776. The freely mobile hydrogen ions make superionic water almost as

Ice phases

(www.idc-online.com) * * *

Physik des Eises

(PDF in German, iktp.tu-dresden.de)

at LSBU's website.

Glass transition in hyperquenched water

from

Glassy Water

from

AIP accounting discovery of VHDA

HDA in space

{{Ice , expanded Glaciology Cryosphere Hydrogen storage

ice

Ice is water that is frozen into a solid state, typically forming at or below temperatures of 0 ° C, 32 ° F, or 273.15 K. It occurs naturally on Earth, on other planets, in Oort cloud objects, and as interstellar ice. As a naturally oc ...

, which have varying properties and molecular geometries. Currently, twenty-one phases, including both crystalline and amorphous

In condensed matter physics and materials science, an amorphous solid (or non-crystalline solid) is a solid that lacks the long-range order that is a characteristic of a crystal. The terms "glass" and "glassy solid" are sometimes used synonymousl ...

ices have been observed. In modern history, phases have been discovered through scientific research with various techniques including pressurization, force application, nucleation agents, and others.

On Earth, most ice is found in the hexagonal Ice Ih phase. Less common phases may be found in the atmosphere and underground due to more extreme pressures and temperatures. Some phases are manufactured by humans for nano scale uses due to their properties. In space, amorphous ice is the most common form as confirmed by observation. Thus, it is theorized to be the most common phase in the universe. Various other phases could be found naturally in astronomical objects.

Theory

Most liquids under increased pressure freeze at ''higher'' temperatures because the pressure helps to hold the molecules together. However, the strong hydrogen bonds in water make it different: for some pressures higher than , water freezes at a temperature ''below'' 0 °C. Subjected to higher pressures and varying temperatures, ice can form in nineteen separate known crystalline phases. With care, at least fifteen of these phases (one of the known exceptions being ice X) can be recovered at ambient pressure and low temperature inmetastable

In chemistry and physics, metastability is an intermediate energetic state within a dynamical system other than the system's state of least energy.

A ball resting in a hollow on a slope is a simple example of metastability. If the ball is onl ...

form. The types are differentiated by their crystalline structure, proton ordering, and density. There are also two metastable

In chemistry and physics, metastability is an intermediate energetic state within a dynamical system other than the system's state of least energy.

A ball resting in a hollow on a slope is a simple example of metastability. If the ball is onl ...

phases of ice under pressure, both fully hydrogen-disordered; these are Ice IV and Ice XII.

Crystal structure

The accepted

The accepted crystal structure

In crystallography, crystal structure is a description of ordered arrangement of atoms, ions, or molecules in a crystalline material. Ordered structures occur from intrinsic nature of constituent particles to form symmetric patterns that repeat ...

of ordinary ice was first proposed by Linus Pauling

Linus Carl Pauling ( ; February 28, 1901August 19, 1994) was an American chemist and peace activist. He published more than 1,200 papers and books, of which about 850 dealt with scientific topics. ''New Scientist'' called him one of the 20 gre ...

in 1935. The structure of ice Ih is the wurtzite lattice, roughly one of crinkled planes composed of tessellating

A tessellation or tiling is the covering of a surface, often a plane (mathematics), plane, using one or more geometric shapes, called ''tiles'', with no overlaps and no gaps. In mathematics, tessellation can be generalized to high-dimensiona ...

hexagonal rings, with an oxygen

Oxygen is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol O and atomic number 8. It is a member of the chalcogen group (periodic table), group in the periodic table, a highly reactivity (chemistry), reactive nonmetal (chemistry), non ...

atom on each vertex, and the edges of the rings formed by hydrogen bond

In chemistry, a hydrogen bond (H-bond) is a specific type of molecular interaction that exhibits partial covalent character and cannot be described as a purely electrostatic force. It occurs when a hydrogen (H) atom, Covalent bond, covalently b ...

s. The planes alternate in an ABAB pattern, with B planes being reflections of the A planes along the same axes as the planes themselves. The distance between oxygen atoms along each bond is about 275 pm and is the same between any two bonded oxygen atoms in the lattice. The angle between bonds in the crystal lattice is very close to the tetrahedral angle of 109.5°, which is also quite close to the angle between hydrogen atoms in the water molecule (in the gas phase), which is 105°.

This tetrahedral bonding angle of the water molecule essentially accounts for the unusually low density of the crystal lattice – it is beneficial for the lattice to be arranged with tetrahedral angles even though there is an energy penalty in the increased volume of the crystal lattice. As a result, the large hexagonal rings leave almost enough room for another water molecule to exist inside. This gives naturally occurring ice its rare property of being less dense than its liquid form. The tetrahedral-angled hydrogen-bonded hexagonal rings are also the mechanism that causes liquid water to be densest at 4 °C. Close to 0 °C, tiny hexagonal ice Ih-like lattices form in liquid water, with greater frequency closer to 0 °C. This effect decreases the density of the water, causing it to be densest at 4 °C when the structures form infrequently.

In the best-known form of ice, ice Ih, the crystal structure is characterized by the oxygen atoms forming hexagonal symmetry with near tetrahedral

In geometry, a tetrahedron (: tetrahedra or tetrahedrons), also known as a triangular pyramid, is a polyhedron composed of four triangular Face (geometry), faces, six straight Edge (geometry), edges, and four vertex (geometry), vertices. The tet ...

bonding angles. This structure is stable down to , as evidenced by x-ray diffraction and extremely high resolution thermal expansion measurements. Ice Ih is also stable under applied pressures of up to about where it transitions into ice III or ice II.

Amorphous ice

While most forms of ice are crystalline, several amorphous (or "vitreous") forms of ice also exist. Such ice is anamorphous solid

In condensed matter physics and materials science, an amorphous solid (or non-crystalline solid) is a solid that lacks the long-range order that is a characteristic of a crystal. The terms "glass" and "glassy solid" are sometimes used synonymousl ...

form of water, which lacks long-range order in its molecular arrangement. Amorphous ice is produced either by rapid cooling of liquid water to its glass transition temperature

The glass–liquid transition, or glass transition, is the gradual and reversible transition in amorphous materials (or in amorphous regions within semicrystalline materials) from a hard and relatively brittle "glassy" state into a viscous or rub ...

(about 136 K or −137 °C) in milliseconds (so the molecules do not have enough time to form a crystal lattice

In crystallography, crystal structure is a description of ordered arrangement of atoms, ions, or molecules in a crystal, crystalline material. Ordered structures occur from intrinsic nature of constituent particles to form symmetric patterns that ...

), or by compressing ordinary ice at low temperatures. The most common form on Earth, low-density ice, is usually formed in the laboratory by a slow accumulation of water vapor molecules (physical vapor deposition

Physical vapor deposition (PVD), sometimes called physical vapor transport (PVT), describes a variety of vacuum deposition methods which can be used to produce thin films and coatings on substrates including metals, ceramics, glass, and polym ...

) onto a very smooth metal

A metal () is a material that, when polished or fractured, shows a lustrous appearance, and conducts electrical resistivity and conductivity, electricity and thermal conductivity, heat relatively well. These properties are all associated wit ...

crystal surface under 120 K. In outer space it is expected to be formed in a similar manner on a variety of cold substrates, such as dust particles. By contrast, hyperquenched glassy water (HGW) is formed by spraying a fine mist of water droplets into a liquid such as propane around 80 K, or by hyperquenching fine micrometer-sized droplets on a sample-holder kept at liquid nitrogen

Liquid nitrogen (LN2) is nitrogen in a liquid state at cryogenics, low temperature. Liquid nitrogen has a boiling point of about . It is produced industrially by fractional distillation of liquid air. It is a colorless, mobile liquid whose vis ...

temperature, 77 K, in a vacuum. Cooling rates above 104 K/s are required to prevent crystallization of the droplets. At liquid nitrogen temperature, 77 K, HGW is kinetically stable and can be stored for many years.

Amorphous ices have the property of suppressing long-range density fluctuations and are, therefore, nearly hyperuniform. Classification

Classification is the activity of assigning objects to some pre-existing classes or categories. This is distinct from the task of establishing the classes themselves (for example through cluster analysis). Examples include diagnostic tests, identif ...

analysis suggests that low and high density amorphous ices are glass

Glass is an amorphous (non-crystalline solid, non-crystalline) solid. Because it is often transparency and translucency, transparent and chemically inert, glass has found widespread practical, technological, and decorative use in window pane ...

es.

Pressure-dependent states

Ice from a theorized superionic water may possess two crystalline structures. At pressures in excess of such ''superionic ice'' would take on a

Ice from a theorized superionic water may possess two crystalline structures. At pressures in excess of such ''superionic ice'' would take on a body-centered cubic

In crystallography, the cubic (or isometric) crystal system is a crystal system where the Crystal structure#Unit cell, unit cell is in the shape of a cube. This is one of the most common and simplest shapes found in crystals and minerals.

There ...

structure. However, at pressures in excess of the structure may shift to a more stable face-centered cubic

In crystallography, the cubic (or isometric) crystal system is a crystal system where the unit cell is in the shape of a cube. This is one of the most common and simplest shapes found in crystals and minerals.

There are three main varieties o ...

lattice. Some estimates suggest that at an extremely high pressure of around , ice would develop metal

A metal () is a material that, when polished or fractured, shows a lustrous appearance, and conducts electrical resistivity and conductivity, electricity and thermal conductivity, heat relatively well. These properties are all associated wit ...

lic properties.

Heat and entropy

Ice, water, and

Ice, water, and water vapour

Water vapor, water vapour, or aqueous vapor is the gaseous phase of water. It is one state of water within the hydrosphere. Water vapor can be produced from the evaporation or boiling of liquid water or from the sublimation of ice. Water vapor ...

can coexist at the triple point

In thermodynamics, the triple point of a substance is the temperature and pressure at which the three Phase (matter), phases (gas, liquid, and solid) of that substance coexist in thermodynamic equilibrium.. It is that temperature and pressure at ...

, which is at a pressure of . The kelvin

The kelvin (symbol: K) is the base unit for temperature in the International System of Units (SI). The Kelvin scale is an absolute temperature scale that starts at the lowest possible temperature (absolute zero), taken to be 0 K. By de ...

was defined as of the difference between this triple point and absolute zero

Absolute zero is the lowest possible temperature, a state at which a system's internal energy, and in ideal cases entropy, reach their minimum values. The absolute zero is defined as 0 K on the Kelvin scale, equivalent to −273.15 ° ...

, though this definition changed in May 2019. Unlike most other solids, ice is difficult to superheat. In an experiment, ice at −3 °C was superheated to about 17 °C for about 250 picoseconds.

The latent heat of melting is , and its latent heat of sublimation is . The high latent heat of sublimation is principally indicative of the strength of the hydrogen bond

In chemistry, a hydrogen bond (H-bond) is a specific type of molecular interaction that exhibits partial covalent character and cannot be described as a purely electrostatic force. It occurs when a hydrogen (H) atom, Covalent bond, covalently b ...

s in the crystal lattice. The latent heat of melting is much smaller, partly because liquid water near 0 °C also contains a significant number of hydrogen bonds. By contrast, the structure of ice II is hydrogen-ordered, which helps to explain the entropy change of 3.22 J/mol when the crystal structure changes to that of ice I. Also, ice XI, an orthorhombic, hydrogen-ordered form of ice Ih, is considered the most stable form at low temperatures.

The transition entropy from ice XIV to ice XII is estimated to be 60% of Pauling entropy based on DSC measurements. The formation of ice XIV from ice XII is more favoured at high pressure.

When medium-density amorphous ice is compressed, released and then heated, it releases a large amount of heat energy, unlike other water ices which return to their normal form after getting similar treatment.

Hydrogen disorder

The

The hydrogen

Hydrogen is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol H and atomic number 1. It is the lightest and abundance of the chemical elements, most abundant chemical element in the universe, constituting about 75% of all baryon, normal matter ...

atoms in the crystal lattice lie very nearly along the hydrogen bonds, and in such a way that each water molecule is preserved. This means that each oxygen atom in the lattice has two hydrogens adjacent to it: at about 101 pm along the 275 pm length of the bond for ice Ih. The crystal lattice allows a substantial amount of disorder in the positions of the hydrogen atoms frozen into the structure as it cools to absolute zero. As a result, the crystal structure contains some residual entropy inherent to the lattice and determined by the number of possible configurations of hydrogen positions that can be formed while still maintaining the requirement for each oxygen atom to have only two hydrogens in closest proximity, and each H-bond joining two oxygen atoms having only one hydrogen atom. This residual entropy is equal to = .

Calculations

There are various ways of approximating this number from first principles. The following is the one used byLinus Pauling

Linus Carl Pauling ( ; February 28, 1901August 19, 1994) was an American chemist and peace activist. He published more than 1,200 papers and books, of which about 850 dealt with scientific topics. ''New Scientist'' called him one of the 20 gre ...

.

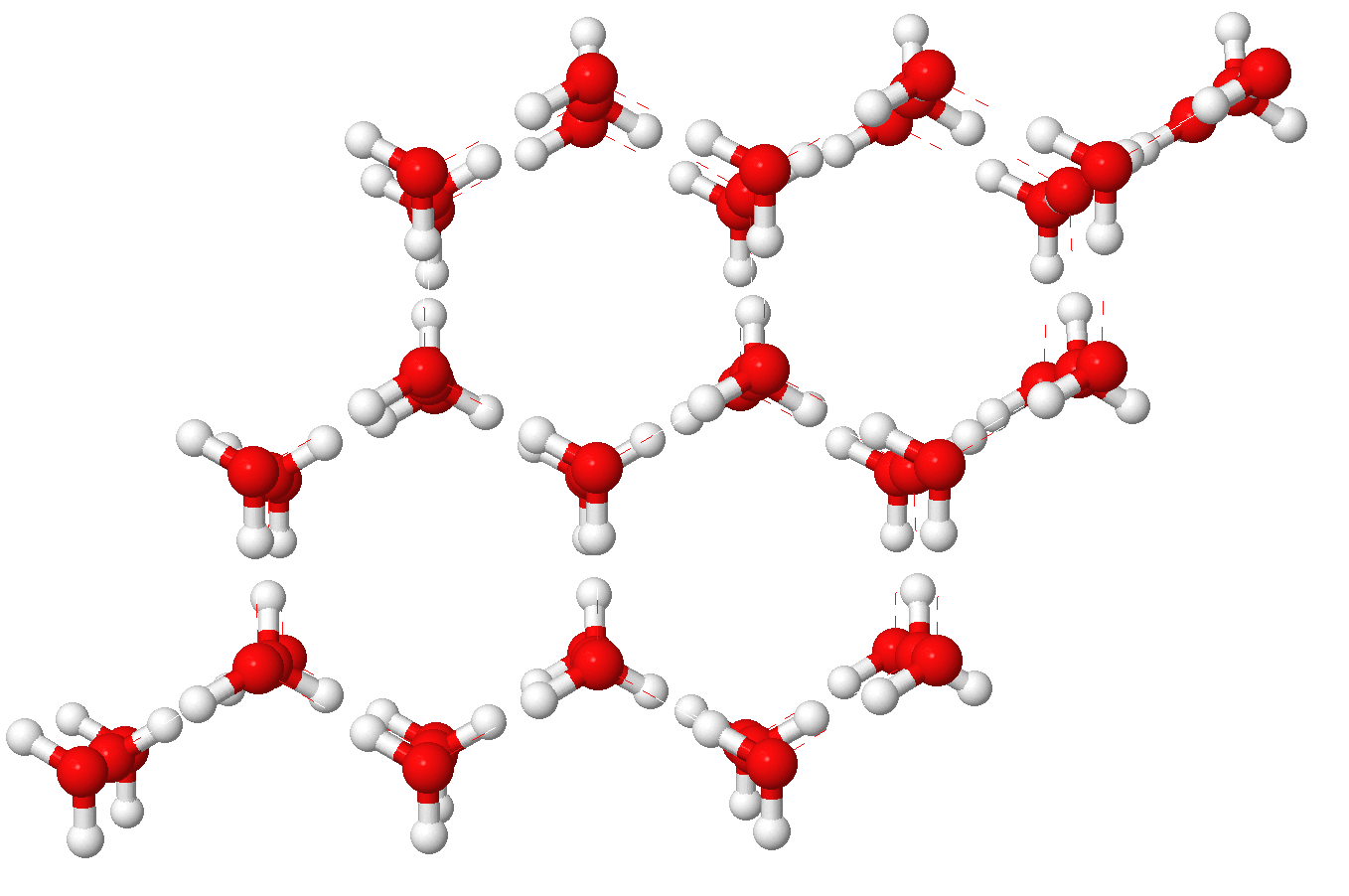

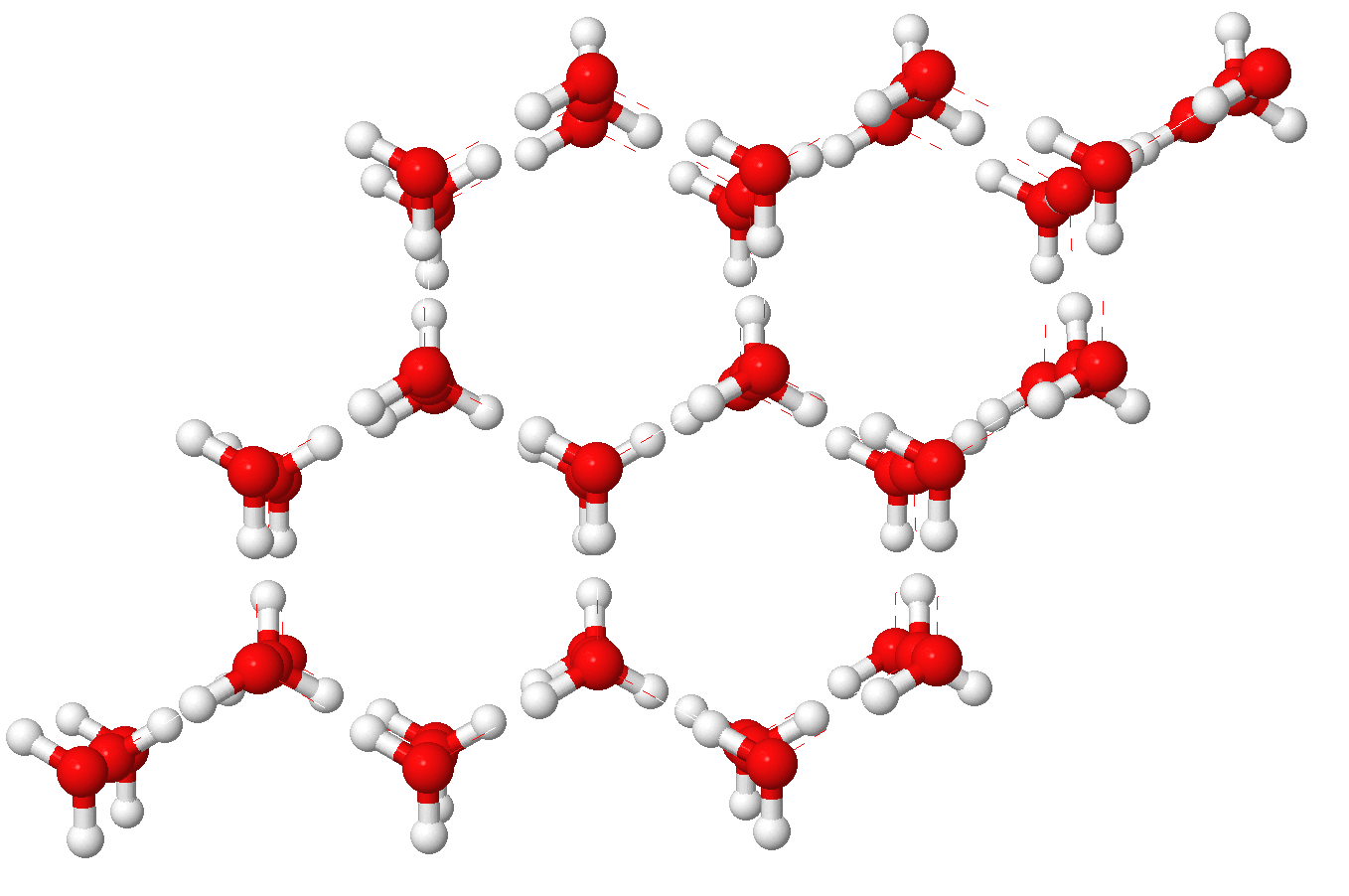

Suppose there are a given number of water molecules in an ice lattice. To compute its residual entropy, we need to count the number of configurations that the lattice can assume. The oxygen atoms are fixed at the lattice points, but the hydrogen atoms are located on the lattice edges. The problem is to pick one end of each lattice edge for the hydrogen to bond to, in a way that still makes sure each oxygen atom is bond to two hydrogen atoms.

The oxygen atoms can be divided into two sets in a checkerboard pattern, shown in the picture as black and white balls. Focus attention on the oxygen atoms in one set: there are of them. Each has four hydrogen bonds, with two hydrogens close to it and two far away. This means there are allowed configurations of hydrogens for this oxygen atom (see ''Binomial coefficient

In mathematics, the binomial coefficients are the positive integers that occur as coefficients in the binomial theorem. Commonly, a binomial coefficient is indexed by a pair of integers and is written \tbinom. It is the coefficient of the t ...

''). Thus, there are configurations that satisfy these atoms. But now, consider the remaining oxygen atoms: in general they won't be satisfied (i.e., they will not have precisely two hydrogen atoms near them). For each of those, there are possible placements of the hydrogen atoms along their hydrogen bonds, of which 6 are allowed. So, naively, we would expect the total number of configurations to be

Using Boltzmann's entropy formula

In statistical mechanics, Boltzmann's entropy formula (also known as the Boltzmann–Planck equation, not to be confused with the more general Boltzmann equation, which is a partial differential equation) is a probability equation relating the en ...

, we conclude that

where is the Boltzmann constant

The Boltzmann constant ( or ) is the proportionality factor that relates the average relative thermal energy of particles in a ideal gas, gas with the thermodynamic temperature of the gas. It occurs in the definitions of the kelvin (K) and the ...

and is the molar gas constant

The molar gas constant (also known as the gas constant, universal gas constant, or ideal gas constant) is denoted by the symbol or . It is the molar equivalent to the Boltzmann constant, expressed in units of energy per temperature increment pe ...

. So, the molar residual entropy is .

The same answer can be found in another way. First orient each water molecule randomly in each of the 6 possible configurations, then check that each lattice edge contains exactly one hydrogen atom. Assuming that the lattice edges are independent, then the probability that a single edge contains exactly one hydrogen atom is 1/2, and since there are edges in total, we obtain a total configuration count , as before.

Refinements

This estimate is naive, as it assumes the six out of 16 hydrogen configurations for oxygen atoms in the second set can be independently chosen, which is false. More complex methods can be employed to better approximate the exact number of possible configurations, and achieve results closer to measured values. Nagle (1966) used a series summation to obtain .

As an illustrative example of refinement, consider the following way to refine the second estimation method given above. According to it, six water molecules in a hexagonal ring would allow configurations. However, by explicit enumeration, there are actually 730 configurations. Now in the lattice, each oxygen atom participates in 12 hexagonal rings, so there are 2N rings in total for N oxygen atoms, or 2 rings for each oxygen atom, giving a refined result of .

This estimate is naive, as it assumes the six out of 16 hydrogen configurations for oxygen atoms in the second set can be independently chosen, which is false. More complex methods can be employed to better approximate the exact number of possible configurations, and achieve results closer to measured values. Nagle (1966) used a series summation to obtain .

As an illustrative example of refinement, consider the following way to refine the second estimation method given above. According to it, six water molecules in a hexagonal ring would allow configurations. However, by explicit enumeration, there are actually 730 configurations. Now in the lattice, each oxygen atom participates in 12 hexagonal rings, so there are 2N rings in total for N oxygen atoms, or 2 rings for each oxygen atom, giving a refined result of .

Known phases

These phases are named according to the Bridgman nomenclature. The majority have only been created in the laboratory at different temperatures and pressures.History of research

Ice II

The properties of ice II were first described and recorded by Gustav Heinrich Johann Apollon Tammann in 1900 during his experiments with ice under high pressure and low temperatures. Having produced ice III, Tammann then tried condensing the ice at a temperature between under of pressure. Tammann noted that in this state ice II was denser than he had observed ice III to be. He also found that both types of ice can be kept at normalatmospheric pressure

Atmospheric pressure, also known as air pressure or barometric pressure (after the barometer), is the pressure within the atmosphere of Earth. The standard atmosphere (symbol: atm) is a unit of pressure defined as , which is equivalent to 1,013. ...

in a stable condition so long as the temperature is kept at that of liquid air

Liquid Air was the marque of an automobile planned by Liquid Air Power and Automobile Co. of Boston and New York City in 1899. page 1432

A factory location was acquired in Boston, Massachusetts in 1899 and Liquid Air claimed they would constr ...

, which slows the change in conformation back to ice Ih.

In later experiments by Bridgman in 1912, it was shown that the difference in volume between ice II and ice III was in the range of . This difference had not been discovered by Tammann due to the small change and was why he had been unable to determine an equilibrium curve between the two. The curve showed that the structural change from ice III to ice II was more likely to happen if the medium had previously been in the structural conformation of ice II. However, if a sample of ice III that had never been in the ice II state was obtained, it could be supercooled even below −70 °C without it changing into ice II. Conversely, however, any superheating of ice II was not possible in regards to retaining the same form. Bridgman found that the equilibrium curve between ice II and ice IV was much the same as with ice III, having the same stability properties and small volume change. The curve between ice II and ice V was extremely different, however, with the curve's bubble being essentially a straight line and the volume difference being almost always .

Search for a hydrogen-disordered counterpart

As ice II is completely hydrogen ordered, the presence of its disordered counterpart is a great matter of interest. Shephard et al. investigated the phase boundaries of NH4F-doped ices because NH4F has been reported to be a hydrogen disordering reagent. However, adding 2.5 mol% of NH4F resulted in the disappearance of ice II instead of the formation of a disordered ice II. According to the DFC calculation by Nakamura et al., the phase boundary between ice II and its disordered counterpart is estimated to be in the stability region of liquid water.Ice IV

1981 research by Engelhardt and Kamb elucidated crystal structure of ice IV through a low-temperature single-crystal X-ray diffraction, describing it as a rhombohedral unit cell with a space group of R-3c. This research mentioned that the structure of ice IV could be derived from the structure of ice Ic by cutting and forming some hydrogen bondings and adding subtle structural distortions. Shephard et al. compressed the ambient phase of NH4F, an isostructural material of ice, to obtain NH4F II, whose hydrogen-bonded network is similar to ice IV. As the compression of ice Ih results in the formation of high-density amorphous ice (HDA), not ice IV, they claimed that the compression-induced conversion of ice I into ice IV is important, naming it "Engelhardt–Kamb collapse" (EKC). They suggested that the reason why we cannot obtain ice IV directly from ice Ih is that ice Ih is hydrogen-disordered; if oxygen atoms are arranged in the ice IV structure, hydrogen bonding may not be formed due to the donor-acceptor mismatch. and Raman The disordered nature of Ice IV was confirmed by neutron powder diffraction studies by Lobban (1998) and Klotz et al. (2003). In addition, the entropy difference between ice VI (disordered phase) and ice IV is very small, according to Bridgman's measurement. Several organic nucleating reagents had been proposed to selectively crystallize ice IV from liquid water, but even with such reagents, the crystallization of ice IV from liquid water was very difficult and seemed to be a random event. In 2001, Salzmann and his coworkers reported a whole new method to prepare ice IV ''reproducibly''; when high-density amorphous ice (HDA) is heated at a rate of 0.4 K/min and a pressure of 0.81 GPa, ice IV is crystallized at about 165 K. What governs the crystallization products is the heating rate; fast heating (over 10 K/min) results in the formation of single-phase ice XII.Search for a hydrogen-ordered counterpart

The ordered counterpart of ice IV has never been reported yet. 2011 research by Salzmann's group reported more detailed DSC data where the endothermic feature becomes larger as the sample is quench-recovered at higher pressure. They proposed three scenarios to explain the experimental results: weak hydrogen-ordering, orientational glass transition, and mechanical distortions. reported the DSC thermograms of HCl-doped ice IV finding an endothermic feature at about 120 K. Ten years later, Rosu-Finsen and Salzmann (2021) reported more detailed DSC data where the endothermic feature becomes larger as the sample is quench-recovered at higher pressure. They proposed three scenarios to explain the experimental results: weak hydrogen-ordering, orientational glass transition, and mechanical distortions.Ice VII

Ice VII is the only disordered phase of ice that can be ordered by simple cooling. (While ice Ih theoretically transforms into proton-ordered ice XI on geologic timescales, in practice it is necessary to add small amounts of KOH catalyst.) It forms (ordered) ice VIII below 273 K up to ~8 GPa. Above this pressure, the VII–VIII transition temperature drops rapidly, reaching 0 K at ~60 GPa.. Thus, ice VII has the largest stability field of all of the molecular phases of ice. The cubic oxygen sub-lattices that form the backbone of the ice VII structure persist to pressures of at least 128 GPa;. this pressure is substantially higher than that at which water loses its molecular character entirely, forming ice X. In high pressure ices, protonic diffusion (movement of protons around the oxygen lattice) dominates molecular diffusion, an effect which has been measured directly.Ice XI

Ice XI is the hydrogen-ordered form of the ordinary form of ice. The total

Ice XI is the hydrogen-ordered form of the ordinary form of ice. The total internal energy

The internal energy of a thermodynamic system is the energy of the system as a state function, measured as the quantity of energy necessary to bring the system from its standard internal state to its present internal state of interest, accoun ...

of ice XI is about one sixth lower than ice Ih, so in principle it should naturally form when ice Ih is cooled to below 72 K. The low temperature required to achieve this transition is correlated with the relatively low energy difference between the two structures. Hints of hydrogen-ordering in ice had been observed as early as 1964, when Dengel et al. attributed a peak in thermo-stimulated depolarization (TSD) current to the existence of a proton-ordered ferroelectric phase. However, they could not conclusively prove that a phase transition had taken place, and Onsager pointed out that the peak could also arise from the movement of defects and lattice imperfections. Onsager suggested that experimentalists look for a dramatic change in heat capacity by performing a careful calorimetric experiment. A phase transition to ice XI was first identified experimentally in 1972 by Shuji Kawada and others.

Water molecules in ice Ih are surrounded by four semi-randomly directed hydrogen

Hydrogen is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol H and atomic number 1. It is the lightest and abundance of the chemical elements, most abundant chemical element in the universe, constituting about 75% of all baryon, normal matter ...

bonds. Such arrangements should change to the more ordered arrangement of hydrogen bonds found in ice XI at low temperatures, so long as localized proton hopping is sufficiently enabled; a process that becomes easier with increasing pressure. Correspondingly, ice XI is believed to have a triple point

In thermodynamics, the triple point of a substance is the temperature and pressure at which the three Phase (matter), phases (gas, liquid, and solid) of that substance coexist in thermodynamic equilibrium.. It is that temperature and pressure at ...

with hexagonal ice and gaseous water at (~72 K, ~0 Pa). Ice Ih that has been transformed to ice XI and then back to ice Ih, on raising the temperature, retains some hydrogen-ordered domains and more easily transforms back to ice XI again. A neutron powder diffraction study found that small hydrogen-ordered domains can exist up to 111 K.

There are distinct differences in the Raman spectra between ices Ih and XI, with ice XI showing much stronger peaks in the translational (~230 cm−1), librational (~630 cm−1) and in-phase asymmetric stretch (~3200 cm−1) regions.

Ice Ic also has a proton-ordered form. The total internal energy of ice XIc was predicted as similar as ice XIh.

Ferroelectric properties

Ice XI isferroelectric

In physics and materials science, ferroelectricity is a characteristic of certain materials that have a spontaneous electric polarization that can be reversed by the application of an external electric field. All ferroelectrics are also piezoel ...

, meaning that it has an intrinsic polarization. To qualify as a ferroelectric it must also exhibit polarization switching under an electric field, which has not been conclusively demonstrated but which is implicitly assumed to be possible. Cubic ice also has a ferrolectric phase and in this case the ferroelectric properties of the ice have been experimentally demonstrated on monolayer thin films. In a similar experiment, ferroelectric layers of hexagonal ice were grown on a platinum (111) surface. The material had a polarization that had a decay length of 30 monolayers suggesting that thin layers of ice XI can be grown on substrates at low temperature without the use of dopants. One-dimensional nano-confined ferroelectric ice XI was created in 2010.

Ice XV

Although the parent phase ice VI was discovered in 1935, corresponding proton-ordered forms (ice XV) had not been observed until 2009. Theoretically, the proton ordering in ice VI was predicted several times; for example,density functional theory

Density functional theory (DFT) is a computational quantum mechanical modelling method used in physics, chemistry and materials science to investigate the electronic structure (or nuclear structure) (principally the ground state) of many-body ...

calculations predicted the phase transition temperature is 108 K and the most stable ordered structure is antiferroelectric in the space group ''Cc'', while an antiferroelectric ''P''212121 structure were found 4 K per water molecule higher in energy.

On 14 June 2009, Christoph Salzmann and colleagues at the University of Oxford reported having experimentally reported an ordered phase of ice VI, named ice XV, and say that its properties differ significantly from those predicted. In particular, ice XV is antiferroelectric rather than ferroelectric

In physics and materials science, ferroelectricity is a characteristic of certain materials that have a spontaneous electric polarization that can be reversed by the application of an external electric field. All ferroelectrics are also piezoel ...

as had been predicted.

In detail, ice XV has a smaller density (larger unit-cell volume) than ice VI. This makes the VI-to-XV disorder-to-order transition much favoured at low pressures. Indeed, differential scanning calorimetry

Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) is a thermoanalytical technique in which the difference in the amount of heat required to increase the temperature of a sample and reference is measured as a function of temperature. Both the sample and re ...

by Shephard and Salzmann revealed that reheating quench-recovered HCl-doped ice XV at ambient pressure even produces exotherms originating from transient ordering, ''i.e.'' more ordered ice XV is obtained at ambient pressure. Being consistent with this, the ice VI-XV transition is reversible at ambient pressure. It was also shown that HCl-doping is selectively effective in producing ice XV while other acids and bases (HF, LiOH, HClO4, HBr) do not significantly enhance ice XV formations.

Based on powder neutron diffraction, the crystal structure of ice XV has been investigated in detail. Some researchers suggested that, in combination with density functional theory calculations, none of the possible perfectly ordered orientational configurations are energetically favoured. This implies that there are several energetically close configurations that coexist in ice XV. They proposed 'the orthorhombic ''Pmmn'' space group as a plausible space group to describe the time-space averaged structure of ice XV.

Other researchers argued that ''P''-1 model is still the best (with the second best candidate of ''P''21), whereas Rietveld refinement using the Pmmn space group only works well for poorly ordered samples. The lattice parameters, in particular ''b'' and ''c'', are good indicators of the ice XV formation. Combining density functional theory calculations, they successfully constructed fully ordered model in ''P''-1 and showed that experimental diffraction data should be analysed using space groups that permit full hydrogen order while the Pmmn model only accepts partially ordered structures.

Ice XVII

In 2016, the discovery of a new form of ice was announced. Characterized as a "porous water ice metastable at atmospheric temperatures", this new form was discovered by taking a filled ice and removing the non-water components, leaving the crystal structure behind, similar to how ice XVI, another porous form of ice, was synthesized from a

In 2016, the discovery of a new form of ice was announced. Characterized as a "porous water ice metastable at atmospheric temperatures", this new form was discovered by taking a filled ice and removing the non-water components, leaving the crystal structure behind, similar to how ice XVI, another porous form of ice, was synthesized from a clathrate hydrate

Clathrate hydrates, or gas hydrates, clathrates, or hydrates, are crystalline water-based solids physically resembling ice, in which small non-polar molecules (typically gases) or polar molecules with large hydrophobic moieties are trapped ins ...

.

To create ice XVII, the researchers first produced filled ice in a stable phase named C from a mixture of hydrogen (H) and water (HO), using temperatures from and pressures from , and C are all stable solid phases of a mixture of H and HO molecules, formed at high pressures. Although sometimes referred to as clathrate hydrate

Clathrate hydrates, or gas hydrates, clathrates, or hydrates, are crystalline water-based solids physically resembling ice, in which small non-polar molecules (typically gases) or polar molecules with large hydrophobic moieties are trapped ins ...

s (or clathrates), they lack the cagelike structure generally found in clathrate hydrates, and are more properly referred to as filled ices. The filled ice is then placed in a vacuum, and the temperature gradually increased until the hydrogen frees itself from the crystal structure. If kept at a temperature range between , after about two hours, the structure will have emptied itself of any detectable hydrogen molecules. The resulting form is metastable

In chemistry and physics, metastability is an intermediate energetic state within a dynamical system other than the system's state of least energy.

A ball resting in a hollow on a slope is a simple example of metastability. If the ball is onl ...

at room pressure while under , but collapses into ice I (ordinary ice) when brought above . The crystal structure is hexagonal in nature, and the pores are helical channels with a diameter of about .

Cubic ice

It was reported in 2020 that cubic ice based onheavy water

Heavy water (deuterium oxide, , ) is a form of water (molecule), water in which hydrogen atoms are all deuterium ( or D, also known as ''heavy hydrogen'') rather than the common hydrogen-1 isotope (, also called ''protium'') that makes up most o ...

(DO) can be formed from ice XVII. This was done by heating specifically prepared DO ice XVII powder. The result was free of structural deformities compared to standard cubic ice, or ice I. This discovery was reported around the same time another research group announced that they were able to obtain pure DO cubic ice by first synthesizing filled ice in the C phase, and then decompressing it.

Ice XVIII (superionic water)

In 1988, predictions of the so-called superionic water state were made. In superionic water, water molecules break apart and the oxygen ions crystallize into an evenly spaced lattice while the hydrogen ions float around freely within the oxygen lattice.Weird water lurking inside giant planetsNew Scientist,01 September 2010, Magazine issue 2776. The freely mobile hydrogen ions make superionic water almost as

conductive

In physics and electrical engineering, a conductor is an object or type of material that allows the flow of Electric charge, charge (electric current) in one or more directions. Materials made of metal are common electrical conductors. The flow ...

as typical metals, making it a superionic conductor. The ice appears black in color. It is distinct from ionic water, which is a hypothetical liquid state characterized by a disordered soup of hydrogen and oxygen ions.

The initial evidence came from optical measurements of laser-heated water in a diamond anvil cell

A diamond anvil cell (DAC) is a high-pressure device used in geology, engineering, and materials science experiments. It permits the compression of a small (sub- millimeter-sized) piece of material to extreme pressures, typically up to around 1 ...

, and from optical measurements of water shocked by extremely powerful lasers. The first definitive evidence for the crystal structure of the oxygen lattice in superionic water came from x-ray measurements on laser-shocked water which were reported in 2019. In 2005 Laurence Fried led a team at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory

Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL) is a Federally funded research and development centers, federally funded research and development center in Livermore, California, United States. Originally established in 1952, the laboratory now i ...

(LLNL) to recreate the formative conditions of superionic water. Using a technique involving smashing water molecules between diamond

Diamond is a Allotropes of carbon, solid form of the element carbon with its atoms arranged in a crystal structure called diamond cubic. Diamond is tasteless, odourless, strong, brittle solid, colourless in pure form, a poor conductor of e ...

s and super heating it with laser

A laser is a device that emits light through a process of optical amplification based on the stimulated emission of electromagnetic radiation. The word ''laser'' originated as an acronym for light amplification by stimulated emission of radi ...

s they observed frequency shifts which indicated that a phase transition

In physics, chemistry, and other related fields like biology, a phase transition (or phase change) is the physical process of transition between one state of a medium and another. Commonly the term is used to refer to changes among the basic Sta ...

had taken place. The team also created computer model

Computer simulation is the running of a mathematical model on a computer, the model being designed to represent the behaviour of, or the outcome of, a real-world or physical system. The reliability of some mathematical models can be determin ...

s which indicated that they had indeed created superionic water. In 2013 Hugh F. Wilson, Michael L. Wong, and Burkhard Militzer at the University of California, Berkeley published a paper predicting the face-centered cubic

In crystallography, the cubic (or isometric) crystal system is a crystal system where the unit cell is in the shape of a cube. This is one of the most common and simplest shapes found in crystals and minerals.

There are three main varieties o ...

lattice structure that would emerge at higher pressures. Additional experimental evidence was found by Marius Millot and colleagues in 2018 by inducing high pressure on water between diamonds and then shocking the water using a laser pulse.

, it is theorized that superionic ice can possess two crystalline structures. At pressures in excess of it is predicted that superionic ice would take on a body-centered cubic

In crystallography, the cubic (or isometric) crystal system is a crystal system where the Crystal structure#Unit cell, unit cell is in the shape of a cube. This is one of the most common and simplest shapes found in crystals and minerals.

There ...

structure. However, at pressures in excess of 100 GPa, and temperatures above 2000 K, it is predicted that the structure would shift to a more stable face-centered cubic

In crystallography, the cubic (or isometric) crystal system is a crystal system where the unit cell is in the shape of a cube. This is one of the most common and simplest shapes found in crystals and minerals.

There are three main varieties o ...

lattice.

In 2018, the existence of superionic ice was confirmed in a laboratory setting. To create the required pressure, LLNL researchers compressed small amounts of water between pieces of diamond. At , the water became ice VII, a form that is solid at room temperature. This ice, trapped within diamond anvil cell

A diamond anvil cell (DAC) is a high-pressure device used in geology, engineering, and materials science experiments. It permits the compression of a small (sub- millimeter-sized) piece of material to extreme pressures, typically up to around 1 ...

s, was taken to the University of Rochester

The University of Rochester is a private university, private research university in Rochester, New York, United States. It was founded in 1850 and moved into its current campus, next to the Genesee River in 1930. With approximately 30,000 full ...

to be blasted with a laser. For less than a billionth of a second, the ice was subjected to conditions similar to those within the mantle of an ice giant

An ice giant is a giant planet composed mainly of elements heavier than hydrogen and helium, such as oxygen, carbon, nitrogen, and sulfur. There are two ice giants in the Solar System: Uranus and Neptune.

In astrophysics and planetary science ...

. The temperature in the diamond cells rose thousands of degrees, and the pressure increased to over a million times that of Earth's atmosphere. The experiment concluded that the current in the conductive water was indeed carried by ions rather than electrons and thus pointed to the water being superionic. More recent experiments from the same LLNL team used x-ray crystallography on laser-shocked water droplets to determine that the oxygen ions enter a face-centered-cubic phase, which was dubbed ice XVIII and reported in the journal ''Nature'' in May 2019.

Ice XIX

The first report regarding ice XIX was published in 2018 by Thomas Loerting's group from Austria. They quenched HCl-doped ice VI to 77 K at different pressures between 1.0 and 1.8 GPa to collectdifferential scanning calorimetry

Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) is a thermoanalytical technique in which the difference in the amount of heat required to increase the temperature of a sample and reference is measured as a function of temperature. Both the sample and re ...

(DSC) thermograms, dielectric spectrum, Raman spectrum, and X-ray diffraction

X-ray diffraction is a generic term for phenomena associated with changes in the direction of X-ray beams due to interactions with the electrons around atoms. It occurs due to elastic scattering, when there is no change in the energy of the waves. ...

patterns. In the DSC signals, there was an endothermic feature at about 110 K in addition to the endotherm corresponding to the ice XV-VI transition. Additionally, the Raman spectra, dielectric properties, and the ratio of the lattice parameters differed from those of ice XV. Based on these observations, they proposed the existence of a second hydrogen-ordered phase of ice VI, naming it ice beta-XV.

In 2019, Alexander Rosu-Finsen and Christoph Salzman argued that there was no need to consider this to be a new phase of ice, and proposed a "deep-glassy" state scenario. According to their DSC data, the size of the endothermic feature depends not only on quench-recovery pressure but also on the heating rate and annealing duration at 93 K. They also collected neutron diffraction profiles of quench-recovered deuterium

Deuterium (hydrogen-2, symbol H or D, also known as heavy hydrogen) is one of two stable isotopes of hydrogen; the other is protium, or hydrogen-1, H. The deuterium nucleus (deuteron) contains one proton and one neutron, whereas the far more c ...

chloride-doped, D2O ice VI/XV prepared at different pressures of 1.0, 1.4 and 1.8 GPa, to show that there were no significant differences among them. They concluded that the low-temperature endotherm originated from kinetic features related to glass transitions of deep glassy states of ''disordered'' ice VI.

Distinguishing between the two scenarios (new hydrogen-ordered phase vs. deep-glassy disordered ice VI) became an open question and the debate between the two groups has continued. Thoeny et al. (Loerting's group) collected another series of Raman spectra of ice beta-XV, and reported that (i) ice XV prepared by the protocol reported previously contains both ice XV and ice beta-XV domains; (ii) upon heating, Raman spectra of ice beta-XV showed loss of H-order. In contrast, Salzmann's group again argued for the plausibility of a 'deep-glassy state' scenario based on neutron diffraction and neutron inelastic scattering experiments. Based on their experimental results, ice VI and deep-glassy ice VI share very similar features based on both elastic (diffraction) scattering and inelastic scattering experiments, and are different from the properties of ice XV.

In 2021, further crystallographic evidence for a new phase (ice XIX) was individually reported by three groups: Yamane et al. (Hiroyuki Kagi and Kazuki Komatsu's group from Japan), Gasser et al. (Loerting's group), and Salzmann's group. Yamane et al. collected neutron diffraction profiles ''in situ'' (''i.e.'' under high pressure) and found new Bragg features completely different from both ice VI and ice XV. They performed Rietveld refinement of the profiles based on the supercell of ice XV and proposed some leading candidates for the space group of ice XIX: P-4, Pca21, Pcc2, P21/a, and P21/c. They also measured dielectric spectra ''in situ'' and determined phase boundaries of ices VI/XV/XIX. They found that the sign of the slope of the boundary turns negative from positive at 1.6 GPa indicating the existence of two different phases by the Clausius–Clapeyron relation

The Clausius–Clapeyron relation, in chemical thermodynamics, specifies the temperature dependence of pressure, most importantly vapor pressure, at a discontinuous phase transition between two phases of matter of a single constituent. It is nam ...

.

Gasser et al. also collected powder neutron diffractograms of quench-recovered ices VI, XV, and XIX and found similar crystallographic features to those reported by Yamane et al., concluding that P-4 and Pcc2 are the plausible space group candidates. Both Yamane et al.'s and Gasser et al.'s results suggested a partially hydrogen-ordered structure. Gasser et al. also found an isotope effect using DSC; the low-temperature endotherm for DCl-doped D2O ice XIX was significantly smaller than that of HCl-doped H2O ice XIX, and that doping of 0.5% of H2O into D2O is sufficient for the ordering transition.

Several months later, Salzmann et al. published a paper based on ''in-situ'' powder neutron diffraction experiments of ice XIX. In a change from their previous reports, they accepted the idea of the new phase (ice XIX) as they observed similar features to the previous two reports. However, they refined their diffraction profiles based on a disordered structural model (Pbcn) and argued that new Bragg reflections can be explained by distortions of ice VI, so ice XIX may still be regarded as a deep-glassy state of ice VI. The crystal structure of ice XIX including hydrogen order/disorder is still under debate as of 2022.

Practical implications

Earth's natural environment

Photograph showing details of an ice cube under magnification. Ice Ih is the form of ice commonly seen on Earth. Phase space of ice Ih with respect to other ice phases. Virtually all ice in thebiosphere

The biosphere (), also called the ecosphere (), is the worldwide sum of all ecosystems. It can also be termed the zone of life on the Earth. The biosphere (which is technically a spherical shell) is virtually a closed system with regard to mat ...

is ice Ih (pronounced: ice one h, also known as ice-phase-one). Ice Ih exhibits many peculiar properties that are relevant to the existence of life and regulation of global climate. For instance, its density is lower than that of liquid water

Water is an inorganic compound with the chemical formula . It is a transparent, tasteless, odorless, and nearly colorless chemical substance. It is the main constituent of Earth's hydrosphere and the fluids of all known living organisms ( ...

. This is attributed to the presence of hydrogen bonds

In chemistry, a hydrogen bond (H-bond) is a specific type of molecular interaction that exhibits partial covalent character and cannot be described as a purely electrostatic force. It occurs when a hydrogen (H) atom, covalently bonded to a mo ...

which causes atoms to become closer in the liquid phase. Because of this, ice Ih floats on water, which is highly unusual when compared to other materials. The solid phase of materials is usually more closely and neatly packed and has a higher density than the liquid phase. When lakes freeze, they do so only at the surface, while the bottom of the lake remains near because water is densest at this temperature. This anomalous behavior of water and ice is what allows fish to survive harsh winters. The density of ice Ih increases when cooled, down to about ; below that temperature, the ice expands again (negative thermal expansion

Negative thermal expansion (NTE) is an unusual physicochemical process in which some materials contract upon heating, rather than expand as most other materials do. The most well-known material with NTE is water at 0 to 3.98 °C. Also, the d ...

).

Besides ice Ih, a small amount of ice Ic may occasionally present in the upper atmosphere clouds. It is believed to be responsible for the observation of Scheiner's halo, a rare ring that occurs near 28 degrees from the Sun or the Moon. However, many atmospheric samples which were previously described as cubic ice were later shown to be stacking disordered ice with trigonal symmetry, and it has been dubbed the ″most faceted ice phase in a literal and a more general sense.″ The first true samples of cubic ice were only reported in 2020.

Low-density ASW (LDA), also known as hyperquenched glassy water, may be responsible for noctilucent clouds

Noctilucent clouds (NLCs), or night shining clouds, are tenuous cloud-like phenomena in the upper atmosphere of Earth. When viewed from space, they are called polar mesospheric clouds (PMCs), detectable as a diffuse scattering layer of water ice ...

on Earth and is usually formed by deposition of water vapor in cold or vacuum conditions. Ice clouds form at and below the Earth's high latitude mesopause (~90 km) where temperatures have been observed to fall as to below 100 K. It has been suggested that homogeneous nucleation of ice particles results in low density amorphous ice. Amorphous ice is likely confined to the coldest parts of the clouds and stacking disordered ice I is thought to dominate elsewhere in these polar mesospheric clouds.

In 2018, ice VII was identified among inclusions found in natural diamonds

Diamond is a solid form of the element carbon with its atoms arranged in a crystal structure called diamond cubic. Diamond is tasteless, odourless, strong, brittle solid, colourless in pure form, a poor conductor of electricity, and insol ...

. Due to this demonstration that ice VII exists in nature, the International Mineralogical Association

Founded in 1958, the International Mineralogical Association (IMA) is an international group of 40 national societies. The goal is to promote the science of mineralogy and to standardize the nomenclature of the 5000 plus known mineral species. ...

duly classified ice VII as a distinct mineral

In geology and mineralogy, a mineral or mineral species is, broadly speaking, a solid substance with a fairly well-defined chemical composition and a specific crystal structure that occurs naturally in pure form.John P. Rafferty, ed. (2011): Mi ...

. The ice VII was presumably formed when water trapped inside the diamonds retained the high pressure of the deep mantle due to the strength and rigidity of the diamond lattice, but cooled down to surface temperatures, producing the required environment of high pressure without high temperature.

Ice XI is thought to be a more stable conformation than ice Ih, and so it may form on Earth. However, the transformation is very slow. According to one report, in Antarctic conditions it is estimated to take at least 100,000 years to form without the assistance of catalysts. Ice XI was sought and found in Antarctic ice that was about 100 years old in 1998. A further study in 2004 was not able to reproduce this finding, however, after studying Antarctic ice which was around 3000 years old. The 1998 Antarctic study also claimed that the transformation temperature (ice XI => ice Ih) is , which is far higher than the temperature of the expected triple point mentioned above (72 K, ~0 Pa). Ice XI was also found in experiments using pure water at very low temperature (~10 K) and low pressure – conditions thought to be present in the upper atmosphere. Recently, small domains of ice XI were found to form in pure water; its phase transition back to ice Ih occurred at 72 K while under hydrostatic pressure conditions of up to 70 MPa.

Human industry

Amorphous ice is used in some scientific experiments, especially incryo-electron microscopy

Cryogenic electron microscopy (cryo-EM) is a transmission electron microscopy technique applied to samples cooled to cryogenic temperatures. For biological specimens, the structure is preserved by embedding in an environment of vitreous ice. An ...

of biomolecules. The individual molecules can be preserved for imaging in a state close to what they are in liquid water.

Ice XVII can repeatedly adsorb

Adsorption is the adhesion of atoms, ions or molecules from a gas, liquid or dissolved solid to a surface. This process creates a film of the ''adsorbate'' on the surface of the ''adsorbent''. This process differs from absorption, in which ...

and release hydrogen molecules without degrading its structure. The total amount of hydrogen that ice XVII can adsorb depends on the amount of pressure applied, but hydrogen molecules can be adsorbed by ice XVII even at pressures as low as a few millibars if the temperature is under . The adsorbed hydrogen molecules can then be released, or desorbed, through the application of heat. This was an unexpected property of ice XVII, and could allow it to be used for hydrogen storage, an issue often mentioned in environmental technology

Environmental technology (or envirotech) is the use of engineering and technological approaches to understand and address issues that affect the environment with the aim of fostering environmental improvement. It involves the application of scien ...

.

Aside from storing hydrogen via compression or liquification

In materials science, liquefaction is a process that generates a liquid from a solid or a gas or that generates a non-liquid phase which behaves in accordance with fluid dynamics.

It occurs both naturally and artificially. As an example of t ...

, it can also be stored within a solid substance, either via a reversible chemical process ( chemisorption) or by having the hydrogen molecules attach to the substance via the van der Waals force

In molecular physics and chemistry, the van der Waals force (sometimes van der Waals' force) is a distance-dependent interaction between atoms or molecules. Unlike ionic or covalent bonds, these attractions do not result from a chemical elec ...

( physisorption). The latter process can occur within ice XVII. In physisorption, there is no chemical reaction, and the chemical bond between the two atoms within a hydrogen molecule remains intact. Because of this, the number of adsorption–desorption cycles ice XVII can withstand is "theoretically infinite".

One significant advantage of using ice XVII as a hydrogen storage medium is the low cost of the only two chemicals involved: hydrogen and water. In addition, ice XVII has shown the ability to store hydrogen at an H to HO molar ratio above 40%, higher than the theoretical maximum ratio for sII clathrate hydrates, another potential storage medium. However, if ice XVII is used as a storage medium, it must be kept under a temperature of or risk being destabilized.

Outer space

In outer space, hexagonal crystalline ice (the predominant form found on Earth) is extremely rare. Known examples are typically associated with volcanic action. Water in theinterstellar medium

The interstellar medium (ISM) is the matter and radiation that exists in the outer space, space between the star systems in a galaxy. This matter includes gas in ionic, atomic, and molecular form, as well as cosmic dust, dust and cosmic rays. It f ...

is instead dominated by amorphous ice, making it likely the most common form of water in the universe.

Amorphous ice can be separated from crystalline ice based on its near-infrared

Infrared (IR; sometimes called infrared light) is electromagnetic radiation (EMR) with wavelengths longer than that of visible light but shorter than microwaves. The infrared spectral band begins with the waves that are just longer than those of ...

and infrared spectrum. At near-IR wavelengths, the characteristics of the 1.65, 3.1, and 4.53 μm water absorption lines are dependent on the ice temperature and crystal order. The peak strength of the 1.65 μm band as well as the structure of the 3.1 μm band are particularly useful in identifying the crystallinity of water ice.

At longer IR wavelengths, amorphous and crystalline ice have characteristically different absorption bands at 44 and 62 μm in that the crystalline ice has significant absorption at 62 μm while amorphous ice does not. In addition, these bands can be used as a temperature indicator at very low temperatures where other indicators (such as the 3.1 and 12 μm bands) fail. This is useful studying ice in the interstellar medium and circumstellar disks. However, observing these features is difficult because the atmosphere is opaque at these wavelengths, requiring the use of space-based infrared observatories.

Properties of the amorphous ice in the Solar System

In general, amorphous ice can form below ~130 K. At this temperature, water molecules are unable to form the crystalline structure commonly found on Earth. Amorphous ice may also form in the coldest region of the Earth's atmosphere, the summer polar mesosphere, wherenoctilucent clouds

Noctilucent clouds (NLCs), or night shining clouds, are tenuous cloud-like phenomena in the upper atmosphere of Earth. When viewed from space, they are called polar mesospheric clouds (PMCs), detectable as a diffuse scattering layer of water ice ...

exist. These low temperatures are readily achieved in astrophysical environments such as molecular clouds, circumstellar disks, and the surfaces of objects in the outer Solar System. In the laboratory, amorphous ice transforms into crystalline ice if it is heated above 130 K, although the exact temperature of this conversion is dependent on the environment and ice growth conditions. The reaction is irreversible and exothermic, releasing 1.26–1.6 kJ/mol.

An additional factor in determining the structure of water ice is deposition rate. Even if it is cold enough to form amorphous ice, crystalline ice will form if the flux of water vapor onto the substrate is less than a temperature-dependent critical flux. This effect is important to consider in astrophysical environments where the water flux can be low. Conversely, amorphous ice can be formed at temperatures higher than expected if the water flux is high, such as flash-freezing events associated with cryovolcanism.

At temperatures less than 77 K, irradiation from ultraviolet photons as well as high-energy electrons and ions can damage the structure of crystalline ice, transforming it into amorphous ice. Amorphous ice does not appear to be significantly affected by radiation at temperatures less than 110 K, though some experiments suggest that radiation might lower the temperature at which amorphous ice begins to crystallize.

Peter Jenniskens and David F. Blake demonstrated in 1994 that a form of high-density amorphous ice is also created during vapor deposition of water on low-temperature (< 30 K) surfaces such as interstellar grains. The water molecules do not fully align to create the open cage structure of low-density amorphous ice. Many water molecules end up at interstitial positions. When warmed above 30 K, the structure re-aligns and transforms into the low-density form.

Molecular clouds, circumstellar disks, and the primordial solar nebula

Molecular cloud

A molecular cloud—sometimes called a stellar nursery if star formation is occurring within—is a type of interstellar cloud of which the density and size permit absorption nebulae, the formation of molecules (most commonly molecular hydrogen, ...

s have extremely low temperatures (~10 K), falling well within the amorphous ice regime. The presence of amorphous ice in molecular clouds has been observationally confirmed. When molecular clouds collapse to form stars, the temperature of the resulting circumstellar disk

A Circumstellar disc (or circumstellar disk) is a torus, pancake or ring-shaped accretion disk of matter composed of gas, dust, planetesimals, asteroids, or collision fragments in orbit around a star. Around the youngest stars, they are the res ...

isn't expected to rise above 120 K, indicating that the majority of the ice should remain in an amorphous state. However, if the temperature rises high enough to sublimate the ice, then it can re-condense into a crystalline form since the water flux rate is so low. This is expected to be the case in the circumstellar disk of IRAS 09371+1212, where signatures of crystallized ice were observed despite a low temperature of 30–70 K.

For the primordial solar nebula, there is much uncertainty as to the crystallinity of water ice during the circumstellar disk and planet formation phases. If the original amorphous ice survived the molecular cloud collapse, then it should have been preserved at heliocentric distances beyond Saturn's orbit (~12 AU).

Comets

The possibility of the presence of amorphous water ice in comets and the release of energy during the phase transition to a crystalline state was first proposed as a mechanism for comet outbursts. Evidence of amorphous ice in comets is found in the high levels of activity observed in long-period, Centaur, and Jupiter Family comets at heliocentric distances beyond ~6 AU. These objects are too cold for the sublimation of water ice, which drives comet activity closer to the Sun, to have much of an effect. Thermodynamic models show that the surface temperatures of those comets are near the amorphous/crystalline ice transition temperature of ~130 K, supporting this as a likely source of the activity. The runaway crystallization of amorphous ice can produce the energy needed to power outbursts such as those observed for Centaur Comet 29P/Schwassmann–Wachmann 1.Kuiper Belt objects

With radiation equilibrium temperatures of 40–50 K, the objects in the Kuiper Belt are expected to have amorphous water ice. While water ice has been observed on several objects, the extreme faintness of these objects makes it difficult to determine the structure of the ices. The signatures of crystalline water ice was observed on50000 Quaoar

Quaoar ( minor-planet designation: 50000 Quaoar) is a ringed dwarf planet in the Kuiper Belt, a ring of many icy planetesimals beyond Neptune. It has an elongated ellipsoidal shape with an average diameter of , about half the size of the d ...

, perhaps due to resurfacing events such as impacts or cryovolcanism.

Icy moons

The Near-Infrared Mapping Spectrometer (NIMS) on NASA's Galileo spacecraft spectroscopically mapped the surface ice of the Jovian satellites Europa, Ganymede, andCallisto

CALLISTO (''Cooperative Action Leading to Launcher Innovation in Stage Toss-back Operations'') is a reusable VTVL Prototype, demonstrator propelled by a small 40 kN Japanese LOX-LH2 rocket engine. It is being developed jointly by the CNES, French ...

. The temperatures of these moons range from 90 to 160 K, warm enough that amorphous ice is expected to crystallize on relatively short timescales. However, it was found that Europa has primarily amorphous ice, Ganymede has both amorphous and crystalline ice, and Callisto is primarily crystalline. This is thought to be the result of competing forces: the thermal crystallization of amorphous ice versus the conversion of crystalline to amorphous ice by the flux of charged particles from Jupiter. Closer to Jupiter than the other three moons, Europa receives the highest level of radiation and thus through irradiation has the most amorphous ice. Callisto is the farthest from Jupiter, receiving the lowest radiation flux and therefore maintaining its crystalline ice. Ganymede, which lies between the two, exhibits amorphous ice at high latitudes and crystalline ice at the lower latitudes. This is thought to be the result of the moon's intrinsic magnetic field, which would funnel the charged particles to higher latitudes and protect the lower latitudes from irradiation. Ganymede's interior probably includes a liquid water ocean with tens to hundreds of kilometers of ice V at its base.

The surface ice of Saturn's moon Enceladus was mapped by the Visual and Infrared Mapping Spectrometer (VIMS) on the NASA/ESA/ASI Cassini space probe. The probe found both crystalline and amorphous ice, with a higher degree of crystallinity at the " tiger stripe" cracks on the surface and more amorphous ice between these regions. The crystalline ice near the tiger stripes could be explained by higher temperatures caused by geological activity that is the suspected cause of the cracks. The amorphous ice might be explained by flash freezing from cryovolcanism, rapid condensation of molecules from water geysers, or irradiation of high-energy particles from Saturn. Similarly, one of the inner layers of Titan

Titan most often refers to:

* Titan (moon), the largest moon of Saturn

* Titans, a race of deities in Greek mythology

Titan or Titans may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment

Fictional entities

Fictional locations

* Titan in fiction, fictiona ...

is believed to contain ice VI.

Medium-density amorphous ice may be present on Europa, as the experimental conditions of its formation are expected to occur there as well. It is possible that the MDA ice's unique property of releasing a large amount of heat energy after being released from compression could be responsible for 'ice quakes' within the thick ice layers.

Planets

Because ice XI can theoretically form at low pressures at temperatures between 50–70 K – temperatures present in astrophysical environments of the outer solar system and within permanently shaded polar craters on the Moon and Mercury. Ice XI forms most easily around 70 K – paradoxically, it takes longer to form at lower temperatures. Extrapolating from experimental measurements, it is estimated to take ~50 years to form at 70 K and ~300 million years at 50 K. It is theorized to be present in places like the upper atmospheres ofUranus

Uranus is the seventh planet from the Sun. It is a gaseous cyan-coloured ice giant. Most of the planet is made of water, ammonia, and methane in a Supercritical fluid, supercritical phase of matter, which astronomy calls "ice" or Volatile ( ...

and Neptune

Neptune is the eighth and farthest known planet from the Sun. It is the List of Solar System objects by size, fourth-largest planet in the Solar System by diameter, the third-most-massive planet, and the densest giant planet. It is 17 t ...

and on Pluto

Pluto (minor-planet designation: 134340 Pluto) is a dwarf planet in the Kuiper belt, a ring of Trans-Neptunian object, bodies beyond the orbit of Neptune. It is the ninth-largest and tenth-most-massive known object to directly orbit the Su ...

and Charon.

Ice VII may comprise the ocean floor of Europa as well as extrasolar planets (such as Awohali, and Enaiposha) that are largely made of water.

Small domains of ice XI could exist in the atmospheres of Jupiter and Saturn as well. The fact that small domains of ice XI can exist at temperatures up to 111 K has some scientists speculating that it may be fairly common in interstellar space, with small 'nucleation seeds' spreading through space and converting regular ice, much like the fabled ice-nine

Ice-nine is a fictional material that appears in Kurt Vonnegut's 1963 novel ''Cat's Cradle''. Ice-nine is described as a Polymorphism (materials science), polymorph of ice which instead of melting at 0 °C (32 °F), melts at 45.8 � ...

mentioned in Vonnegut's ''Cat's Cradle

''Cat's Cradle'' is a satirical postmodern novel, with science fiction elements, by American writer Kurt Vonnegut. Vonnegut's fourth novel, it was first published on March 18, 1963, exploring and satirizing issues of science, technology, the p ...

''. The possible roles of ice XI in interstellar space and planet formation have been the subject of several research papers. Until observational confirmation of ice XI in outer space is made, the presence of ice XI in space remains controversial owing to the aforementioned criticism raised by Iitaka. The infrared absorption spectra of ice XI was studied in 2009 in preparation for searches for ice XI in space.

It is theorized that the ice giant

An ice giant is a giant planet composed mainly of elements heavier than hydrogen and helium, such as oxygen, carbon, nitrogen, and sulfur. There are two ice giants in the Solar System: Uranus and Neptune.

In astrophysics and planetary science ...

planets Uranus

Uranus is the seventh planet from the Sun. It is a gaseous cyan-coloured ice giant. Most of the planet is made of water, ammonia, and methane in a Supercritical fluid, supercritical phase of matter, which astronomy calls "ice" or Volatile ( ...

and Neptune

Neptune is the eighth and farthest known planet from the Sun. It is the List of Solar System objects by size, fourth-largest planet in the Solar System by diameter, the third-most-massive planet, and the densest giant planet. It is 17 t ...

hold a layer of superionic water. Machine learning

Machine learning (ML) is a field of study in artificial intelligence concerned with the development and study of Computational statistics, statistical algorithms that can learn from data and generalise to unseen data, and thus perform Task ( ...

and free-energy methods predict close-packed superionic phases to be stable over a wide temperature and pressure range, and a body-centred cubic superionic phase to be kinetically favoured, but stable over a small window of parameters. On the other hand, there are also studies that suggest that other elements present inside the interiors of these planets, particularly carbon

Carbon () is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol C and atomic number 6. It is nonmetallic and tetravalence, tetravalent—meaning that its atoms are able to form up to four covalent bonds due to its valence shell exhibiting 4 ...

, may prevent the formation of superionic water.

Notes

References

Further reading

Ice phases

(www.idc-online.com) * * *

Physik des Eises

(PDF in German, iktp.tu-dresden.de)

External links

* *at LSBU's website.

Glass transition in hyperquenched water

from

Nature

Nature is an inherent character or constitution, particularly of the Ecosphere (planetary), ecosphere or the universe as a whole. In this general sense nature refers to the Scientific law, laws, elements and phenomenon, phenomena of the physic ...

(requires registration)

Glassy Water

from

Science

Science is a systematic discipline that builds and organises knowledge in the form of testable hypotheses and predictions about the universe. Modern science is typically divided into twoor threemajor branches: the natural sciences, which stu ...

, on phase diagrams of water (requires registration)

AIP accounting discovery of VHDA

HDA in space

{{Ice , expanded Glaciology Cryosphere Hydrogen storage