History of Namibia on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The history of Namibia has passed through several distinct stages from being colonised in the late nineteenth century to Namibia's independence on 21 March 1990.

From 1884,

During the 17th century the

During the 17th century the

The last group of people today considered

The last group of people today considered

The Nama's resistance proved to be unsuccessful, however, and in 1894 Witbooi was forced to sign a "protection treaty" with the Germans. The treaty allowed the Nama to keep their arms, and Witbooi was released having given his word of honour not to continue with the Hottentot uprising.

In 1894 major

The Nama's resistance proved to be unsuccessful, however, and in 1894 Witbooi was forced to sign a "protection treaty" with the Germans. The treaty allowed the Nama to keep their arms, and Witbooi was released having given his word of honour not to continue with the Hottentot uprising.

In 1894 major  Being the only German colony in Africa considered suitable for white settlement at the time, Namibia attracted an influx of German settlers. In 1903 there were 3,700 Germans living in the area, and by 1910 their number had increased to 13,000. Another reason for German settlement was the discovery of

Being the only German colony in Africa considered suitable for white settlement at the time, Namibia attracted an influx of German settlers. In 1903 there were 3,700 Germans living in the area, and by 1910 their number had increased to 13,000. Another reason for German settlement was the discovery of

To cope with the situation, Germany sent 14,000 additional troops who soon crushed the rebellion in the

To cope with the situation, Germany sent 14,000 additional troops who soon crushed the rebellion in the

In the period, four UN Commissioners for Namibia were appointed. South Africa refused to recognize any of these United Nations appointees. Nevertheless, discussions proceeded with UN Commissioner for Namibia N°2

In the period, four UN Commissioners for Namibia were appointed. South Africa refused to recognize any of these United Nations appointees. Nevertheless, discussions proceeded with UN Commissioner for Namibia N°2

By 9 February 1990, the Constituent Assembly had drafted and adopted a constitution. Independence Day on 21 March 1990, was attended by numerous international representatives, including the main players, the UN Secretary-General

By 9 February 1990, the Constituent Assembly had drafted and adopted a constitution. Independence Day on 21 March 1990, was attended by numerous international representatives, including the main players, the UN Secretary-General

Since independence Namibia has successfully completed the transition from white minority apartheid rule to a democratic society. Multiparty democracy was introduced and has been maintained, with local, regional and national elections held regularly. Several registered political parties are active and represented in the National Assembly, although

Since independence Namibia has successfully completed the transition from white minority apartheid rule to a democratic society. Multiparty democracy was introduced and has been maintained, with local, regional and national elections held regularly. Several registered political parties are active and represented in the National Assembly, although

excerpt

* Kössler, Reinhart. "Entangled history and politics: Negotiating the past between Namibia and Germany." ''Journal of contemporary African studies'' 26.3 (2008): 313–339

online

* Kössler, Reinhart. "Images of History and the Nation: Namibia and Zimbabwe compared." ''South African Historical Journal '' 62.1 (2010): 29–53. * Lyon, William Blakemore. "From Labour Elites to Garveyites: West African Migrant Labour in Namibia, 1892–1925." ''Journal of Southern African Studies'' 47.1 (2020): 37–55

online

* Silvester, Jeremy, and Jan-Bart Gewald. eds. ''Words cannot be found: German colonial rule in Namibia: an Annotated Reprint of the 1918 Blue Book'' (Brill, 2003). * Wallace, Marion. ''History of Namibia: From the Beginning to 1990'' (Oxford University Press, 2014)

excerpt

African Activist Archive Project

website has material on the struggle for independence and support in the U.S. for that struggle produced by many U.S. organizations includin

National Namibia Concerns

th

Lawyers' Committee for Civil Rights Under Law

and th

Evangelical Lutheran Church in America

and predecessor organizations). Other organizations on the Archive with significant material on Namibia include the American Committee on Africa, Episcopal Churchpeople for Southern Africa, and the Washington Office on Africa (available on the Browse page). * * Besenyo, Molnar

UN peacekeeping in Namibia

, Tradecraft Review, Periodical of the Military National Security Service, 2013, 1. Special Issue, 93–109 * * Pre-colonisation history * * * * Baster history * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:History Of Namibia History of Southern Africa by country

Namibia

Namibia, officially the Republic of Namibia, is a country on the west coast of Southern Africa. Its borders include the Atlantic Ocean to the west, Angola and Zambia to the north, Botswana to the east and South Africa to the south; in the no ...

was a German colony: German South West Africa

German South West Africa () was a colony of the German Empire from 1884 until 1915, though Germany did not officially recognise its loss of this territory until the 1919 Treaty of Versailles.

German rule over this territory was punctuated by ...

. After the First World War

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, the League of Nations

The League of Nations (LN or LoN; , SdN) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference (1919–1920), Paris Peace ...

gave South Africa a mandate

Mandate most often refers to:

* League of Nations mandates, quasi-colonial territories established under Article 22 of the Covenant of the League of Nations, 28 June 1919

* Mandate (politics), the power granted by an electorate

Mandate may also r ...

to administer the territory. Following World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, the League of Nations was dissolved in April 1946 and its successor, the United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is the Earth, global intergovernmental organization established by the signing of the Charter of the United Nations, UN Charter on 26 June 1945 with the stated purpose of maintaining international peace and internationa ...

, instituted a trusteeship system to reform the administration of the former League of Nations mandates and clearly establish majority rule and independence as eventual goals for the trust territories. South Africa objected arguing that a majority of the territory's people were content with South African rule.

Legal argument ensued over the course of the next twenty years until, in October 1966, the UN General Assembly

The United Nations General Assembly (UNGA or GA; , AGNU or AG) is one of the six principal organs of the United Nations (UN), serving as its main deliberative, policymaking, and representative organ. Currently in its 79th session, its powers, ...

decided to end the mandate, declaring that South Africa had no further right to administer the territory, and that henceforth South West Africa

South West Africa was a territory under Union of South Africa, South African administration from 1915 to 1990. Renamed ''Namibia'' by the United Nations in 1968, Independence of Namibia, it became independent under this name on 21 March 1990. ...

was to come under the direct responsibility of the UN (Resolution 2145 XXI of 27 October 1966).

Pre-colonial history

As early as 25 000 B.C., the first humans lived in the Huns Mountains in the South of Namibia. The painted stone plates that exist from that time not only prove that these settlements existed, they also belong among the oldest works of art in the world. A fragment of a hominoid jaw, estimated to be thirteen million years old, was found in theOtavi Mountains

Otavi is a town with 10,000 inhabitants in the Otjozondjupa Region of Namibia. Situated 360 km north of Windhoek, it is the district capital of the Otavi electoral constituency.

Geography

The towns of Otavi, Tsumeb (to the north) and Gro ...

. Findings of Stone Age

The Stone Age was a broad prehistory, prehistoric period during which Rock (geology), stone was widely used to make stone tools with an edge, a point, or a percussion surface. The period lasted for roughly 3.4 million years and ended b ...

weapons and tools are further proof that a long time ago early humans already hunted the wild animals of the region.

In the Brandberg Mountains, there are numerous rock paintings, most of them originating from around 2000 B.C. There is no reliable indication as to which ethnic groups created them. It is debatable whether the San (Bushmen), who alongside the Damara are the oldest ethnic group in Namibia, were the creators of these paintings.

The Nama only settled in southern Africa and southern Namibia during the first century B.C. In contrast to the San and Damara, they lived on the livestock they bred themselves.

The north – the Ovambo and Kavango

TheOvambo

Ovambo may refer to:

*Ovambo language, Bantu language of Namibia

**Ovambo people, Bantu people of Namibia

*Ovamboland, former Bantustan in South West Africa (now Namibia)

*Ovambo sparrowhawk

The Ovambo or Ovampo sparrowhawk, also known as Hilge ...

, and the smaller and closely related group Kavango, lived in northern Namibia, southern Angola

Angola, officially the Republic of Angola, is a country on the west-Central Africa, central coast of Southern Africa. It is the second-largest Portuguese-speaking world, Portuguese-speaking (Lusophone) country in both total area and List of c ...

and, in the case of the Kavango, western Zambia. Being settled people they had an economy based on farming, cattle and fishing, but they also produced metal goods. Both groups belonged to the Bantu

Bantu may refer to:

*Bantu languages, constitute the largest sub-branch of the Niger–Congo languages

*Bantu peoples, over 400 peoples of Africa speaking a Bantu language

* Bantu knots, a type of African hairstyle

*Black Association for National ...

nation. They rarely ventured south to the central parts of the country, since the conditions there did not suit their farming way of life, but they extensively traded their knives and agricultural implements.

Bantu Migration – the Herero

During the 17th century the

During the 17th century the Herero

Herero may refer to:

* Herero people, a people belonging to the Bantu group, with about 240,000 members alive today

* Herero language, a language of the Bantu family (Niger-Congo group)

* Herero and Nama genocide

* Herero chat, a species of bird ...

, a pastoral

The pastoral genre of literature, art, or music depicts an idealised form of the shepherd's lifestyle – herding livestock around open areas of land according to the seasons and the changing availability of water and pasture. The target au ...

, nomadic people keeping cattle, moved into Namibia. They came from the east African lakes and entered Namibia from the northwest. First they resided in Kaokoland

Kaokoland was an administrative unit and a Bantustan in northern South West Africa (now Namibia). Established in 1980 during the apartheid era, it was intended to be a self-governing homeland of the Ovahimba, but an actual government was nev ...

, but in the middle of the 19th century some tribes moved farther south and into Damaraland. A number of tribes remained in Kaokoland: these were the Himba people

The Himba (singular: OmuHimba, plural: OvaHimba) are an ethnic group with an estimated population of about 50,000 people living in northern Namibia, in the Kunene Region (formerly Kaokoland) and on the other side of the Kunene River in southern A ...

, who are still there today. During German occupation of South West Africa

South West Africa was a territory under Union of South Africa, South African administration from 1915 to 1990. Renamed ''Namibia'' by the United Nations in 1968, Independence of Namibia, it became independent under this name on 21 March 1990. ...

about one third of the population was wiped out in a genocide that continues to provoke widespread indignation. An apology was sought in more recent times.

The Oorlams

In the 19th century white farmers, mostlyBoer

Boers ( ; ; ) are the descendants of the proto Afrikaans-speaking Free Burghers of the eastern Cape frontier in Southern Africa during the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries. From 1652 to 1795, the Dutch East India Company controlled the Dutch ...

s, moved further north, pushing the indigenous

Indigenous may refer to:

*Indigenous peoples

*Indigenous (ecology)

In biogeography, a native species is indigenous to a given region or ecosystem if its presence in that region is the result of only local natural evolution (though often populari ...

Khoisan peoples, who put up a fierce resistance, across the Orange River. Known as Oorlam

The Oorlam or Orlam people (also known as Orlaam, Oorlammers, Oerlams, or Orlamse Hottentots) are a subtribe of the Nama people, largely assimilated after their migration from the Cape Colony (today, part of South Africa) to Namaqualand and ...

s, these Khoisan adopted Boer customs and spoke a language similar to Afrikaans

Afrikaans is a West Germanic languages, West Germanic language spoken in South Africa, Namibia and to a lesser extent Botswana, Zambia, Zimbabwe and also Argentina where there is a group in Sarmiento, Chubut, Sarmiento that speaks the Pat ...

.

Armed with guns, the Oorlams caused instability as more and more came to settle in Namaqualand and eventually conflict arose between them and the Nama. Under the leadership of Jonker Afrikaner

Jonker Afrikaner (3 February 1785, 18 August 1861, Okahandja) was the fourth Captain of the Orlam in South West Africa, succeeding his father, Jager Afrikaner, in 1823. Soon after becoming ''Kaptein'', he left his father's settlement at Bly ...

, the Oorlams used their superior weapons to take control of the best grazing land. In the 1830s Jonker Afrikaner concluded an agreement with the Nama chief Oaseb whereby the Oorlams would protect the central grasslands of Namibia from the Herero who were then pushing south. In return Jonker Afrikaner was recognised as overlord, received tribute from the Nama, and settled at what today is Windhoek, on the borders of Herero territory. The Afrikaners soon came in conflict with the Herero who entered Damaraland from the south at about the same time as the Afrikaner started to expand farther north from Namaqualand. Both the Herero and the Afrikaner wanted to use the grasslands of Damaraland for their herds. This resulted in warfare between the Herero and the Oorlams as well as between the two of them and the Damara, who were the original inhabitants of the area. The Damara were displaced by the fighting and many were killed.

With their horses and guns, the Afrikaners proved to be militarily superior and forced the Herero to give them cattle as tribute.

Baster immigration

The last group of people today considered

The last group of people today considered indigenous

Indigenous may refer to:

*Indigenous peoples

*Indigenous (ecology)

In biogeography, a native species is indigenous to a given region or ecosystem if its presence in that region is the result of only local natural evolution (though often populari ...

that arrived in Namibia were the Basters

The Basters (also known as Baasters, Rehobothers, or Rehoboth Basters) are a Southern African ethnic group descended from Cape Coloureds and Nama of Khoisan origin. Since the second half of the 19th century, the Rehoboth Baster community has ...

; descendants of Boer men and African women (mostly Khoisan). Being Calvinist

Reformed Christianity, also called Calvinism, is a major branch of Protestantism that began during the 16th-century Protestant Reformation. In the modern day, it is largely represented by the Continental Reformed Protestantism, Continenta ...

and Afrikaans

Afrikaans is a West Germanic languages, West Germanic language spoken in South Africa, Namibia and to a lesser extent Botswana, Zambia, Zimbabwe and also Argentina where there is a group in Sarmiento, Chubut, Sarmiento that speaks the Pat ...

-speaking, they considered themselves to be culturally more "white" than "black". As with the Oorlams, they were forced northwards by the expansion of white settlers when, in 1868, a group of about 90 families crossed the Orange River

The Orange River (from Afrikaans/Dutch language, Dutch: ''Oranjerivier'') is a river in Southern Africa. It is the longest river in South Africa. With a total length of , the Orange River Basin extends from Lesotho into South Africa and Namibi ...

into Namibia.

The Basters settled in central Namibia, where they founded the city Rehoboth. In 1872 they founded the "Free Republic of Rehoboth" and adopted a constitution stating that the nation should be led by a "Kaptein" directly elected by the people, and that there should be a small parliament, or Volkraad, consisting of three directly elected citizens.

European influence and colonization

The first European to set foot on Namibian soil was the PortugueseDiogo Cão

Diogo Cão (; – 1486), also known as Diogo Cam, was a Portuguese mariner and one of the most notable explorers of the fifteenth century. He made two voyages along the west coast of Africa in the 1480s, exploring the Congo River and the coasts ...

in 1485, who stopped briefly on the Skeleton Coast

The Skeleton Coast is the northern part of the Atlantic coast of Namibia. Immediately south of Angola, it stretches from the Kunene River to the Swakop River, although the name is sometimes used to describe the entire Namib Desert coast. The in ...

, and raised a limestone cross there, on his exploratory mission along the west coast of Africa. The next European to visit Namibia was also a Portuguese, Bartholomeu Dias, who stopped at what today is known as Walvis Bay

Walvis Bay (; ; ) is a city in Namibia and the name of the bay on which it lies. It is the List of cities in Namibia, second largest city in Namibia and the largest coastal city in the country. The city covers an area of of land.

The bay is a ...

and Lüderitz

Lüderitz is a town in the ǁKaras Region of southern Namibia. It lies on one of the least hospitable coasts in Africa. It is a port developed around Robert Harbour and Shark Island. Lüderitz had a population of 16,125 people in 2023.

Th ...

(which he named Angra Pequena) on his way to round the Cape of Good Hope

The Cape of Good Hope ( ) is a rocky headland on the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic coast of the Cape Peninsula in South Africa.

A List of common misconceptions#Geography, common misconception is that the Cape of Good Hope is the southern tip of Afri ...

. The inhospitable Namib Desert

The Namib ( ; ) is a coastal desert in Southern Africa. According to the broadest definition, the Namib stretches for more than along the Atlantic coasts of Angola, Namibia, and northwest South Africa, extending southward from the Carunjamba Ri ...

constituted a formidable barrier and neither of the Portuguese explorers went far inland.

The area was vaguely regarded as Cafreria ("the land of the kaffirs") and similar terms over the next few centuries.

In 1793 the Dutch authority in the Cape decided to take control of Walvis Bay, since it was the only good deep-water harbour along the Skeleton Coast. When the United Kingdom took control of the Cape Colony

The Cape Colony (), also known as the Cape of Good Hope, was a British Empire, British colony in present-day South Africa named after the Cape of Good Hope. It existed from 1795 to 1802, and again from 1806 to 1910, when it united with three ...

in 1805, they also took over Walvis Bay. But colonial settlement in the area was limited, and neither the Dutch nor the British penetrated far into the country.

One of the first European groups to show interest in Namibia were the missionaries

A missionary is a member of a religious group who is sent into an area in order to promote its faith or provide services to people, such as education, literacy, social justice, health care, and economic development.Thomas Hale 'On Being a Miss ...

. In 1805 the London Missionary Society

The London Missionary Society was an interdenominational evangelical missionary society formed in England in 1795 at the instigation of Welsh Congregationalist minister Edward Williams. It was largely Reformed tradition, Reformed in outlook, with ...

began working in Namibia, moving north from the Cape Colony. In 1811 they founded the town Bethanie in southern Namibia, where they built a church, which was long considered to be Namibia's oldest building, before the site at ǁKhauxaǃnas

ǁKhauxaǃnas (Khoekhoegowab: ''passively defend people from an enemy'', Afrikaans / Dutch language, Dutch name Schans Vlakte: ''fortified valley'') is an uninhabited village with a ruined fortress in south-eastern Namibia, east of the Great Kar ...

which pre-dates European settlement was recognised.

In the 1840s the German Rhenish Mission Society

The Rhenish Missionary Society (''Rhenish'' of the river Rhine; , ''RMG'') was one of the largest Protestant missionary societies in Germany. Formed from smaller missions founded as far back as 1799, the Society was amalgamated on 23 September 1 ...

started working in Namibia and co-operating with the London Missionary Society.

It was not until the 19th century, when European powers sought to carve up the African continent between them in the so-called "Scramble for Africa

The Scramble for Africa was the invasion, conquest, and colonialism, colonisation of most of Africa by seven Western European powers driven by the Second Industrial Revolution during the late 19th century and early 20th century in the era of ...

", that Europeans – Germany in the forefront – became interested in Namibia.

The first territorial claim on a part of Namibia came when Britain occupied Walvis Bay

Walvis Bay (; ; ) is a city in Namibia and the name of the bay on which it lies. It is the List of cities in Namibia, second largest city in Namibia and the largest coastal city in the country. The city covers an area of of land.

The bay is a ...

, confirming the settlement of 1797, and permitted the Cape Colony to annex it in 1878. The annexation was an attempt to forestall German ambitions in the area, and it also guaranteed control of the good deepwater harbour on the way to the Cape Colony and other British colonies on Africa's east coast.

In 1883, a German trader, Adolf Lüderitz

Franz Adolf Eduard Lüderitz (16 July 1834 – end of October 1886) was a German merchant and the founder of German South West Africa, Imperial Germany's first colony. The coastal town of Lüderitz, located in the ǁKaras Region of souther ...

, bought Angra Pequena

Angra may refer to:

Places

* Bay of Angra (Baía de Angra), within Angra do Heroísmo on the Portuguese island of Terceira in the archipelago of the Azores

* Angra do Heroísmo, a municipality in the Azores, Portugal

* Angra dos Reis, a municipal ...

from the Nama chief Josef Frederiks II. The price he paid was 10,000 marks (ℳ) and 260 guns.

He soon renamed the coastal area after himself, giving it the name Lüderitz. Believing that Britain was soon about to declare the whole area a protectorate, Lüderitz advised the German chancellor Otto von Bismarck

Otto, Prince of Bismarck, Count of Bismarck-Schönhausen, Duke of Lauenburg (; born ''Otto Eduard Leopold von Bismarck''; 1 April 1815 – 30 July 1898) was a German statesman and diplomat who oversaw the unification of Germany and served as ...

to claim it. In 1884 Bismarck did so, thereby establishing German South West Africa

German South West Africa () was a colony of the German Empire from 1884 until 1915, though Germany did not officially recognise its loss of this territory until the 1919 Treaty of Versailles.

German rule over this territory was punctuated by ...

as a colony (Deutsch-Südwestafrika in German).

A region, the Caprivi Strip

The Caprivi Strip, also known simply as Caprivi, is a geographic salient protruding from the northeastern corner of Namibia. It is bordered by Botswana to the south and Angola and Zambia to the north. Namibia, Botswana and Zambia meet at a sing ...

, became a part of German South West Africa after the Heligoland-Zanzibar Treaty on 1 July 1890, between the United Kingdom and Germany. The Caprivi Strip in Namibia gave Germany access to the Zambezi River

The Zambezi (also spelled Zambeze and Zambesi) is the fourth-longest river in Africa, the longest east-flowing river in Africa and the largest flowing into the Indian Ocean from Africa. Its drainage basin covers , slightly less than half of t ...

and thereby to German colonies in East Africa. In exchange for the island of Heligoland

Heligoland (; , ; Heligolandic Frisian: , , Mooring Frisian: , ) is a small archipelago in the North Sea. The islands were historically possessions of Denmark, then became possessions of the United Kingdom from 1807 to 1890. Since 1890, the ...

in the North Sea, Britain assumed control of the island of Zanzibar

Zanzibar is a Tanzanian archipelago off the coast of East Africa. It is located in the Indian Ocean, and consists of many small Island, islands and two large ones: Unguja (the main island, referred to informally as Zanzibar) and Pemba Island. ...

in East Africa.

German South West Africa

Soon after declaring Lüderitz and a vast area along the Atlantic coast a German protectorate, German troops were deployed as conflicts with the native tribes flared up, most significantly with the Nama. Under the leadership of the tribal chief Hendrik Witbooi, the Nama put up a fierce resistance to the German occupation. Contemporary media called the conflict "The Hottentot Uprising". The Nama's resistance proved to be unsuccessful, however, and in 1894 Witbooi was forced to sign a "protection treaty" with the Germans. The treaty allowed the Nama to keep their arms, and Witbooi was released having given his word of honour not to continue with the Hottentot uprising.

In 1894 major

The Nama's resistance proved to be unsuccessful, however, and in 1894 Witbooi was forced to sign a "protection treaty" with the Germans. The treaty allowed the Nama to keep their arms, and Witbooi was released having given his word of honour not to continue with the Hottentot uprising.

In 1894 major Theodor Leutwein

Theodor Gotthilf Leutwein (9 May 1849 – 13 April 1921) was a German military officer and colonial administrator who served as Landeshauptmann and governor of German Southwest Africa from 1894 to 1905.

Life and career

Leutwein was born i ...

was appointed governor of German South West Africa. He tried without great success to apply the principle of "colonialism without bloodshed". The protection treaty did have the effect of stabilising the situation but pockets of rebellion persisted, and were put down by an elite German regiment Schutztruppe

(, Protection Force) was the official name of the colonial troops in the African territories of the German colonial empire from the late 19th century to 1918. Similar to other colonial armies, the consisted of volunteer European commissioned a ...

, while real peace was never achieved between the colonialists and the natives. The introduction of a veterinary pest-exclusion fence called the Red Line, which separated the north from the rest of the territory, led to more direct colonial rule south of the line and indirect control north of the line, leading to different political and economic outcomes for example between the northern Ovambo people

The Ovambo people (), also called Aawambo, Ambo, Aawambo (Ndonga, Nghandjera, Kwambi, Kwaluudhi, Kolonghadhi, Mbalantu, mbadja), or Ovawambo (Kwanyama), are a Bantu peoples, Bantu ethnic group native to Southern Africa, primarily modern Namibia. ...

compared to the more centrally located Herero people

The Herero () are a Bantu people, Bantu ethnic group inhabiting parts of Southern Africa. 178,987 Namibians identified as Ovaherero in the 2023 census. They speak Otjiherero, a Bantu language. Though the Herero primarily reside in Namibia, there ...

.

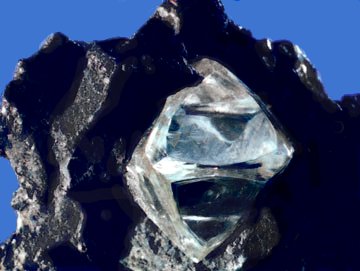

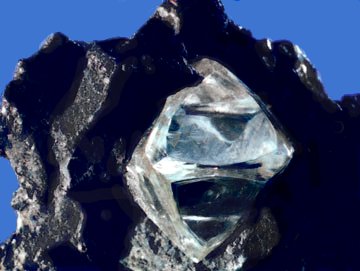

Being the only German colony in Africa considered suitable for white settlement at the time, Namibia attracted an influx of German settlers. In 1903 there were 3,700 Germans living in the area, and by 1910 their number had increased to 13,000. Another reason for German settlement was the discovery of

Being the only German colony in Africa considered suitable for white settlement at the time, Namibia attracted an influx of German settlers. In 1903 there were 3,700 Germans living in the area, and by 1910 their number had increased to 13,000. Another reason for German settlement was the discovery of diamonds

Diamond is a solid form of the element carbon with its atoms arranged in a crystal structure called diamond cubic. Diamond is tasteless, odourless, strong, brittle solid, colourless in pure form, a poor conductor of electricity, and insol ...

in 1908. Diamond production continues to be a very important part of Namibia's economy.

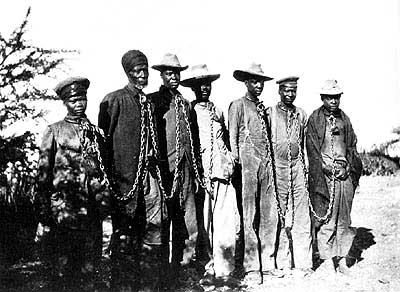

The settlers were encouraged by the government to expropriate land from the natives, and forced labour – hard to distinguish from slavery – was used. As a result, relations between the German settlers and the natives deteriorated.

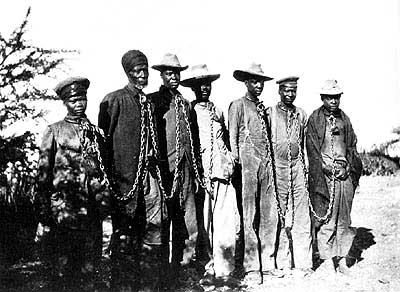

The Herero and Nama wars

The ongoing local rebellions escalated in 1904 into the Herero and Nama Wars when the Herero attacked remote farms on the countryside, killing approximately 150 Germans. The outbreak of rebellion was considered to be a result of Theodor Leutwein's softer tactics, and he was replaced by the more notorious GeneralLothar von Trotha

Adrian Dietrich Lothar von Trotha (3 July 1848 – 31 March 1920) was a German military commander during the European new colonial era. As a brigade commander of the East Asian Expedition Corps, he was involved in suppressing the Boxer Rebelli ...

.

In the beginning of the war the Herero, under the leadership of chief Samuel Maharero

Samuel Maharero (1856 – 14 March 1923) was a Paramount Chief of the Herero people in German South West Africa (today Namibia) during their revolts and in connection with the events surrounding the Herero and Nama genocide. Today he is con ...

, had the upper hand. With good knowledge of the terrain they had little problem in defending themselves against the Schutztruppe (initially numbering only 766). Soon the Nama people joined the war, again under the leadership of Hendrik Witbooi.

To cope with the situation, Germany sent 14,000 additional troops who soon crushed the rebellion in the

To cope with the situation, Germany sent 14,000 additional troops who soon crushed the rebellion in the Battle of Waterberg

The Battle of Waterberg (Battle of Ohamakari) took place on August 11, 1904, at the Waterberg, German South West Africa (modern day Namibia), and was the decisive battle in the German campaign against the Herero.

Armies

The German Imperial F ...

in 1904. Earlier von Trotha issued an ultimatum to the Herero, denying them citizenship rights and ordering them to leave the country or be killed. To escape, the Herero retreated into the waterless Omaheke

Omaheke (the Otjiherero word for sandveld) is one of the fourteen regions of Namibia, the least populous region. Its capital is Gobabis. It lies in eastern Namibia on the border with Botswana and is the western extension of the Kalahari Desert. Th ...

region, a western arm of the Kalahari Desert

The Kalahari Desert is a large semiarid climate, semiarid sandy savanna in Southern Africa covering including much of Botswana as well as parts of Namibia and South Africa.

It is not to be confused with the Angolan, Namibian, and South African ...

, where many of them died of thirst. The German forces guarded every water source and were given orders to shoot any adult male Herero on sight; later orders included killing all Herero and Nama, including children. Only a few of them managed to escape into neighbouring British territories. These tragic events, known as the ''Herero and Nama Genocide'', resulted in the death of between 24,000 and 65,000 Herero (estimated at 50% to 70% of the total Herero population) and 10,000 Nama (50% of the total Nama population). The genocide was characterized by widespread death by starvation and from consumption of well water which had been poisoned by the Germans in the Namib Desert

The Namib ( ; ) is a coastal desert in Southern Africa. According to the broadest definition, the Namib stretches for more than along the Atlantic coasts of Angola, Namibia, and northwest South Africa, extending southward from the Carunjamba Ri ...

.Dan Kroll, "Securing our water supply: protecting a vulnerable resource", PennWell Corp/University of Michigan Press, pg. 22

Descendants of Lothar von Trotha apologized to six chiefs of Herero royal houses for the actions of their ancestor on 7 October 2007.

South African rule

In 1915, duringWorld War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the Southern Africa, southernmost country in Africa. Its Provinces of South Africa, nine provinces are bounded to the south by of coastline that stretches along the Atlantic O ...

launched a military campaign and occupied the German colony of South West Africa

South West Africa was a territory under Union of South Africa, South African administration from 1915 to 1990. Renamed ''Namibia'' by the United Nations in 1968, Independence of Namibia, it became independent under this name on 21 March 1990. ...

.

In February 1917, Mandume Ya Ndemufayo, the last king of the Kwanyama of Ovamboland

Ovamboland, also referred to as Owamboland, was a Bantustan and later a non-geographic ethnic-based second-tier authority, the Representative Authority of the Ovambos, in South West Africa (present-day Namibia).

The apartheid government stat ...

, was killed in a joint attack by South African forces for resisting South African sovereignty

Sovereignty can generally be defined as supreme authority. Sovereignty entails hierarchy within a state as well as external autonomy for states. In any state, sovereignty is assigned to the person, body or institution that has the ultimate au ...

over his people.

On 17 December 1920, South Africa undertook administration of South West Africa under the terms of Article 22 of the Covenant of the League of Nations

The League of Nations (LN or LoN; , SdN) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference (1919–1920), Paris Peace ...

and a Class C Mandate

Mandate most often refers to:

* League of Nations mandates, quasi-colonial territories established under Article 22 of the Covenant of the League of Nations, 28 June 1919

* Mandate (politics), the power granted by an electorate

Mandate may also r ...

agreement by the League Council. The Class C mandate, supposed to be used for the least developed territories, gave South Africa full power of administration and legislation over the territory, but required that South Africa promote the material and moral well-being and social progress of the people.

Following the League's supersession by the United Nations in 1946, South Africa refused to surrender its earlier mandate to be replaced by a United Nations Trusteeship agreement, requiring closer international monitoring of the territory's administration. Although the South African government wanted to incorporate South West Africa into its territory, it never officially did so, although it was administered as the ''de facto'' 'fifth province', with the white minority having representation in the whites-only Parliament of South Africa

The Parliament of the Republic of South Africa is South Africa's legislature. It is located in Cape Town; the country's legislative capital city, capital.

Under the present Constitution of South Africa, the bicameralism, bicameral Parliamen ...

. In 1959, the colonial forces in Windhoek sought to remove black residents further away from the white area of town. The residents protested and the subsequent killing of eleven protesters spawned a major Namibian nationalist following and the formation of united black opposition to South African rule.

During the 1960s, as the European powers granted independence to their colonies and trust territories in Africa, pressure mounted on South Africa to do so in Namibia, which was then South West Africa. On the dismissal (1966) by the International Court of Justice

The International Court of Justice (ICJ; , CIJ), or colloquially the World Court, is the only international court that Adjudication, adjudicates general disputes between nations, and gives advisory opinions on International law, internation ...

of a complaint brought by Ethiopia

Ethiopia, officially the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, is a landlocked country located in the Horn of Africa region of East Africa. It shares borders with Eritrea to the north, Djibouti to the northeast, Somalia to the east, Ken ...

and Liberia

Liberia, officially the Republic of Liberia, is a country on the West African coast. It is bordered by Sierra Leone to Liberia–Sierra Leone border, its northwest, Guinea to Guinea–Liberia border, its north, Ivory Coast to Ivory Coast–Lib ...

against South Africa's continued presence in the territory, the U.N. General Assembly revoked South Africa's mandate. Under the growing international pressure to legitimize its annexation of Namibia, South Africa established in 1962 the ‘Commission of Enquiry into South West Africa Affairs’, better known as the Odendaal commission, named after Frans Hendrik Odendaal, who headed the commission. Its goal was to introduce South African racist homeland politics in Namibia, while at the same time present the occupation as a progressive and scientific way to develop and support the people in Namibia.

Namibian struggle for independence

In 1966,South West Africa People's Organisation

The South West Africa People's Organisation (SWAPO ; , SWAVO; , SWAVO), officially known as the SWAPO Party of Namibia, is a political party and former independence movement in Namibia (formerly South West Africa). Founded in 1960, it has been ...

's (SWAPO) military wing, the People's Liberation Army of Namibia

The People's Liberation Army of Namibia (PLAN) was the military wing of the South West Africa People's Organisation (SWAPO). It fought against the South African Defence Force (SADF) and South West Africa Territorial Force (SWATF) during the S ...

(PLAN) began guerrilla attacks on South African forces, infiltrating the territory from bases in Zambia

Zambia, officially the Republic of Zambia, is a landlocked country at the crossroads of Central Africa, Central, Southern Africa, Southern and East Africa. It is typically referred to being in South-Central Africa or Southern Africa. It is bor ...

. The first attack of this kind was the battle at Omugulugwombashe

Omugulugwombashe (also: ''Ongulumbashe'', official: ''Omugulu gwOombashe''; Otjiherero: ''giraffe leg'') is a List of villages and settlements in Namibia, settlement in the Tsandi Constituency, Tsandi electoral constituency in the Omusati Region o ...

on 26 August. After Angola became independent in 1975, SWAPO established bases in the southern part of the country. Hostilities intensified over the years, especially in Ovamboland.

In a 1971 advisory opinion, the International Court of Justice

The International Court of Justice (ICJ; , CIJ), or colloquially the World Court, is the only international court that Adjudication, adjudicates general disputes between nations, and gives advisory opinions on International law, internation ...

upheld UN authority over Namibia, determining that the South African presence in Namibia was illegal and that South Africa therefore was obliged to withdraw its administration from Namibia immediately. The Court also advised UN member states to refrain from implying legal recognition or assistance to the South African presence.

The summer 1971-72 saw a general strike of 25% of the entire working population of contract workers (13,000 people), starting in Windhoek and Walvis Bay and soon spreading to Tsumeb

Tsumeb (; ) is a city of around 35,000 inhabitants and the largest town in the Oshikoto Region, Oshikoto region in northern Namibia.

Tsumeb, since its founding in 1905, has been primarily a mining town. The town is the site of a deep mine (the ...

and other mines. In response to the contract system, which has been characterized close to slavery, and in support of Namibian independence.

In 1975, South Africa sponsored the Turnhalle Constitutional Conference

The Turnhalle Constitutional Conference was a conference held in Windhoek

Windhoek (; ; ) is the capital and largest city of Namibia. It is located in central Namibia in the Khomas Highland plateau area, at around above sea level, almost e ...

, which sought an "internal settlement" to Namibia. Excluding SWAPO, the conference mainly included bantustan

A Bantustan (also known as a Bantu peoples, Bantu homeland, a Black people, black homeland, a Khoisan, black state or simply known as a homeland; ) was a territory that the National Party (South Africa), National Party administration of the ...

leaders as well as white Namibian political parties.

International pressure

In 1977, the Western Contact Group (WCG) was formed including Canada, France,West Germany

West Germany was the common English name for the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG) from its formation on 23 May 1949 until German reunification, its reunification with East Germany on 3 October 1990. It is sometimes known as the Bonn Republi ...

, the United Kingdom, and the United States. They launched a joint diplomatic effort to bring an internationally acceptable transition to independence for Namibia. The WCG's efforts led to the presentation in 1978 of Security Council Resolution 435 for settling the Namibian problem. The ''settlement proposal'', as it became known, was worked out after lengthy consultations with South Africa, the front-line states (Angola

Angola, officially the Republic of Angola, is a country on the west-Central Africa, central coast of Southern Africa. It is the second-largest Portuguese-speaking world, Portuguese-speaking (Lusophone) country in both total area and List of c ...

, Botswana

Botswana, officially the Republic of Botswana, is a landlocked country in Southern Africa. Botswana is topographically flat, with approximately 70 percent of its territory part of the Kalahari Desert. It is bordered by South Africa to the sou ...

, Mozambique

Mozambique, officially the Republic of Mozambique, is a country located in Southeast Africa bordered by the Indian Ocean to the east, Tanzania to the north, Malawi and Zambia to the northwest, Zimbabwe to the west, and Eswatini and South Afr ...

, Tanzania

Tanzania, officially the United Republic of Tanzania, is a country in East Africa within the African Great Lakes region. It is bordered by Uganda to the northwest; Kenya to the northeast; the Indian Ocean to the east; Mozambique and Malawi to t ...

, Zambia

Zambia, officially the Republic of Zambia, is a landlocked country at the crossroads of Central Africa, Central, Southern Africa, Southern and East Africa. It is typically referred to being in South-Central Africa or Southern Africa. It is bor ...

, and Zimbabwe

file:Zimbabwe, relief map.jpg, upright=1.22, Zimbabwe, relief map

Zimbabwe, officially the Republic of Zimbabwe, is a landlocked country in Southeast Africa, between the Zambezi and Limpopo Rivers, bordered by South Africa to the south, Bots ...

), SWAPO, UN officials, and the Western Contact Group. It called for the holding of elections in Namibia under UN supervision and control, the cessation of all hostile acts by all parties, and restrictions on the activities of South African and Namibian military, paramilitary, and police.

South Africa agreed to cooperate in achieving the implementation of Resolution 435. Nonetheless, in December 1978, in defiance of the UN proposal, it unilaterally held elections

An election is a formal group decision-making process whereby a population chooses an individual or multiple individuals to hold public office.

Elections have been the usual mechanism by which modern representative democracy has operated ...

, which were boycotted by SWAPO and a few other political parties. South Africa continued to administer Namibia through its installed multiracial coalitions and an appointed Administrator-General. Negotiations after 1978 focused on issues such as supervision of elections connected with the implementation of the ''settlement proposal''.

Negotiations and transition

In the period, four UN Commissioners for Namibia were appointed. South Africa refused to recognize any of these United Nations appointees. Nevertheless, discussions proceeded with UN Commissioner for Namibia N°2

In the period, four UN Commissioners for Namibia were appointed. South Africa refused to recognize any of these United Nations appointees. Nevertheless, discussions proceeded with UN Commissioner for Namibia N°2 Martti Ahtisaari

Martti Oiva Kalevi Ahtisaari (, 23 June 1937 – 16 October 2023) was a Finnish politician, the tenth president of Finland, from 1994 to 2000, a Nobel Peace Prize laureate, and a United Nations diplomat and mediation, mediator noted for his inte ...

who played a key role in getting the Constitutional Principles agreed in 1982 by the front-line states, SWAPO, and the Western Contact Group. This agreement created the framework for Namibia's democratic constitution. The US Government's role as mediator was both critical and disputed throughout the period, one example being the intense efforts in 1984 to obtain withdrawal of the South African Defence Force

The South African Defence Force (SADF) (Afrikaans: ''Suid-Afrikaanse Weermag'') comprised the armed forces of South Africa from 1957 until 1994. Shortly before the state reconstituted itself as a republic in 1961, the former Union Defence Fo ...

(SADF) from southern Angola. The so-called "constructive engagement

Constructive engagement was the name given to the conciliatory foreign policy of the Reagan administration towards the apartheid regime in South Africa. Devised by Chester Crocker, Reagan's U.S. Assistant Secretary of State for African Affairs ...

" by US diplomatic interests was viewed negatively by those who supported internationally recognised independence, while to others US policy seemed to be aimed more towards restraining Soviet-Cuban influence in Angola and linking that to the issue of Namibian independence. In addition, US moves seemed to encourage the South Africans to delay independence by taking initiatives that would keep the Soviet-Cubans in Angola, such as dominating large tracts of southern Angola militarily while at the same time providing surrogate forces for the Angolan opposition movement, UNITA

The National Union for the Total Independence of Angola (, abbr. UNITA) is the second-largest political party in Angola. Founded in 1966, UNITA fought alongside the People's Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA) and the National Liberat ...

. From 1985 to 1989, a Transitional Government of National Unity Transitional Government of National Unity may refer to:

* Transitional Government of National Unity (Chad), a government in Chad between 1979 and 1982

* Transitional Government of National Unity (Namibia), a government in South West Africa (Namibia ...

, backed by South Africa and various ethnic political parties, tried unsuccessfully for recognition by the United Nations. Finally, in 1987 when prospects for Namibian independence seemed to be improving, the fourth UN Commissioner for Namibia Bernt Carlsson was appointed. Upon South Africa's relinquishing control of Namibia, Commissioner Carlsson's role would be to administer the country, formulate its framework constitution, and organize free and fair elections based upon a non-racial universal franchise.

In May 1988, a US mediation team – headed by Chester A. Crocker, US Assistant Secretary of State for African Affairs – brought negotiators from Angola

Angola, officially the Republic of Angola, is a country on the west-Central Africa, central coast of Southern Africa. It is the second-largest Portuguese-speaking world, Portuguese-speaking (Lusophone) country in both total area and List of c ...

, Cuba

Cuba, officially the Republic of Cuba, is an island country, comprising the island of Cuba (largest island), Isla de la Juventud, and List of islands of Cuba, 4,195 islands, islets and cays surrounding the main island. It is located where the ...

, and South Africa, and observers from the Soviet Union together in London. Intense diplomatic activity characterized the next 7 months, as the parties worked out agreements to bring peace to the region and make possible the implementation of UN Security Council

The United Nations Security Council (UNSC) is one of the six principal organs of the United Nations (UN) and is charged with ensuring international peace and security, recommending the admission of new UN members to the General Assembly, an ...

Resolution 435 (UNSCR 435). At the Ronald Reagan

Ronald Wilson Reagan (February 6, 1911 – June 5, 2004) was an American politician and actor who served as the 40th president of the United States from 1981 to 1989. He was a member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party a ...

/Mikhail Gorbachev

Mikhail Sergeyevich Gorbachev (2 March 1931 – 30 August 2022) was a Soviet and Russian politician who served as the last leader of the Soviet Union from 1985 to dissolution of the Soviet Union, the country's dissolution in 1991. He served a ...

summit in Moscow (29 May – 1 June 1988) between leaders of the United States and the Soviet Union, it was decided that Cuban troops would be withdrawn from Angola, and Soviet military aid would cease, as soon as South Africa withdrew from Namibia. Agreements to give effect to these decisions were drawn up for signature in New York in December 1988. Cuba, South Africa, and the People's Republic of Angola agreed to a complete withdrawal of foreign troops from Angola. This agreement, known as the ''Brazzaville Protocol'', established a Joint Monitoring Commission (JMC) with the United States and the Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

as observers. The Tripartite Accord, comprising a bilateral agreement between Cuba and Angola, and a tripartite agreement between Angola, Cuba and South Africa whereby South Africa agreed to hand control of Namibia to the United Nations, were signed at UN headquarters

, image = Midtown Manhattan Skyline 004 (cropped).jpg

, image_size = 275px

, caption = View of the complex from Long Island City in 2021; from left to right: the Secretariat, Conference, and General Assembly buildi ...

in New York City on 22 December 1988. (UN Commissioner N°4 Bernt Carlsson

Bernt Wilmar Carlsson (21 November 1938 – 21 December 1988) was a Swedish social democrat and diplomat who served as Assistant-Secretary-General of the United Nations and United Nations Commissioner for Namibia from July 1987 until he died on ...

was not present at the signing ceremony. He was killed on flight Pan Am 103 which exploded over Lockerbie

Lockerbie (, ) is a town in Dumfries and Galloway, located in south-western Scotland. The 2001 Census recorded its population as 4,009. The town had an estimated population of in . The town came to international attention in December 1988 when ...

, Scotland

Scotland is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It contains nearly one-third of the United Kingdom's land area, consisting of the northern part of the island of Great Britain and more than 790 adjac ...

on 21 December 1988 ''en route'' from London

London is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of both England and the United Kingdom, with a population of in . London metropolitan area, Its wider metropolitan area is the largest in Wester ...

to New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

New York may also refer to:

Places United Kingdom

* ...

. South African foreign minister, Pik Botha

Roelof Frederik "Pik" Botha, (27 April 1932 – 12 October 2018) was a South African politician who served as the country's foreign minister in the last years of the apartheid era, the longest-serving in South African history. Known as a lib ...

, and an official delegation of 22 had a lucky escape. Their booking on Pan Am 103 was cancelled at the last minute and Pik Botha

Roelof Frederik "Pik" Botha, (27 April 1932 – 12 October 2018) was a South African politician who served as the country's foreign minister in the last years of the apartheid era, the longest-serving in South African history. Known as a lib ...

, together with a smaller delegation, caught the earlier Pan Am 101 flight to New York.)

Within a month of the signing of the New York Accords, South African president P. W. Botha

Pieter Willem Botha, ( , ; 12 January 1916 – 31 October 2006) was a South African politician who served as the last Prime Minister of South Africa from 1978 to 1984 and as the first executive State President of South Africa from 1984 until ...

suffered a mild stroke, which prevented him from attending a meeting with Namibian leaders on 20 January 1989. His place was taken by acting president J. Christiaan Heunis. Botha had fully recuperated by 1 April 1989 when implementation of UNSCR 435 officially started and the South African–appointed Administrator-General, Louis Pienaar

Louis Alexander Pienaar (23 June 1926 – 5 November 2012) was a South African lawyer and diplomat. He was the last white Administrator of South-West Africa, from 1985 through Namibian independence in 1990. Pienaar later served as a minister in ...

, began the territory's transition to independence. Former UN Commissioner N°2 and now UN Special Representative Martti Ahtisaari

Martti Oiva Kalevi Ahtisaari (, 23 June 1937 – 16 October 2023) was a Finnish politician, the tenth president of Finland, from 1994 to 2000, a Nobel Peace Prize laureate, and a United Nations diplomat and mediation, mediator noted for his inte ...

arrived in Windhoek in April 1989 to head the UN Transition Assistance Group's (UNTAG

The United Nations Transition Assistance Group (UNTAG) was a United Nations (UN) peacekeeping force deployed from April 1989 to March 1990 in Namibia, known at the time as South West Africa, to monitor the peace process and elections there. N ...

) mission.

The transition got off to a shaky start. Contrary to SWAPO President Sam Nujoma

Samuel Shafiishuna Daniel Nujoma ( ; 12May 19298February 2025) was a Namibian revolutionary, anti-apartheid activist and politician who served three terms as the first president of Namibia, from 1990 to 2005. Nujoma was a founding member and t ...

's written assurances to the UN Secretary General to abide by a cease-fire and repatriate only unarmed Namibians, it was alleged that approximately 2,000 armed members of the People's Liberation Army of Namibia (PLAN), SWAPO's military wing, crossed the border from Angola in an apparent attempt to establish a military presence in northern Namibia. UNTAG's Martti Ahtisaari

Martti Oiva Kalevi Ahtisaari (, 23 June 1937 – 16 October 2023) was a Finnish politician, the tenth president of Finland, from 1994 to 2000, a Nobel Peace Prize laureate, and a United Nations diplomat and mediation, mediator noted for his inte ...

took advice from Margaret Thatcher

Margaret Hilda Thatcher, Baroness Thatcher (; 13 October 19258 April 2013), was a British stateswoman who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1979 to 1990 and Leader of the Conservative Party (UK), Leader of th ...

, who was visiting Southern Africa at the time, and authorized a limited contingent of South African troops to assist the South West African Police in restoring order. A period of intense fighting followed, during which 375 PLAN fighters were killed. At a hastily arranged meeting of the Joint Monitoring Commission in Mount Etjo, a game park outside Otjiwarongo

Otjiwarongo (Herero language, Herero for "beautiful place") is a city of 49,000 inhabitants in the Otjozondjupa Region of Namibia. It is the district capital of the Otjiwarongo Constituency, Otjiwarongo electoral constituency and also the capital ...

, it was agreed to confine the South African forces to base and return PLAN elements to Angola. While that problem was resolved, minor disturbances in the north continued throughout the transition period.

In October 1989, under orders of the UN Security Council, Pretoria was forced to demobilize some 1,600 members of Koevoet

Koevoet (, Afrikaans for ''Crowbar (tool), crowbar'', also known as Operation K or SWAPOL-COIN) was the counterinsurgency branch of the South West African Police (SWAPOL). Its formations included white South African police officers, usually se ...

(Afrikaans for ''crowbar''). The Koevoet issue had been one of the most difficult UNTAG faced. This counter-insurgency unit was formed by South Africa after the adoption of UNSCR 435, and was not, therefore, mentioned in the Settlement Proposal or related documents. The UN regarded Koevoet as a paramilitary unit which ought to be disbanded but the unit continued to deploy in the north in armoured and heavily armed convoys. In June 1989, the Special Representative told the Administrator-General that this behavior was totally inconsistent with the ''settlement proposal'', which required the police to be lightly armed. Moreover, the vast majority of the Koevoet personnel were quite unsuited for continued employment in the South West African Police ( SWAPOL). The Security Council, in its resolution of 29 August, therefore demanded the disbanding of Koevoet and dismantling of its command structures. South African foreign minister, Pik Botha, announced on 28 September 1989 that 1,200 ex-Koevoet members would be demobilized with effect from the following day. A further 400 such personnel were demobilized on 30 October. These demobilizations were supervised by UNTAG military monitors.

The 11-month transition period ended relatively smoothly. Political prisoners were granted amnesty, discriminatory legislation was repealed, South Africa withdrew all its forces from Namibia, and some 42,000 refugees returned safely and voluntarily under the auspices of the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Refugees

The Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) is a United Nations agency mandated to aid and protect refugees, forcibly displaced communities, and stateless people, and to assist in their voluntary repatriation, l ...

(UNHCR). Almost 98% of registered voters turned out to elect members of the Constituent Assembly. The elections were held in November 1989, overseen by foreign observers, and were certified as free and fair by the UN Special Representative, with SWAPO

The South West Africa People's Organisation (SWAPO ; , SWAVO; , SWAVO), officially known as the SWAPO Party of Namibia, is a political party and former independence movement in Namibia (formerly South West Africa). Founded in 1960, it has been ...

taking 57% of the vote, just short of the two-thirds necessary to have a free hand in revising the framework constitution that had been formulated not by UN Commissioner Bernt Carlsson but by the South African appointee Louis Pienaar

Louis Alexander Pienaar (23 June 1926 – 5 November 2012) was a South African lawyer and diplomat. He was the last white Administrator of South-West Africa, from 1985 through Namibian independence in 1990. Pienaar later served as a minister in ...

. The opposition Democratic Turnhalle Alliance

The Popular Democratic Movement (PDM), formerly Democratic Turnhalle Alliance (DTA), is an amalgamation of political parties in Namibia, registered as one singular party for representation purposes. In coalition with the United Democratic Front ...

received 29% of the vote. The Constituent Assembly held its first meeting on 21 November 1989 and resolved unanimously to use the 1982 Constitutional Principles in Namibia's new constitution.

Independence

By 9 February 1990, the Constituent Assembly had drafted and adopted a constitution. Independence Day on 21 March 1990, was attended by numerous international representatives, including the main players, the UN Secretary-General

By 9 February 1990, the Constituent Assembly had drafted and adopted a constitution. Independence Day on 21 March 1990, was attended by numerous international representatives, including the main players, the UN Secretary-General Javier Pérez de Cuéllar

Javier Felipe Ricardo Pérez de Cuéllar de la Guerra ( , ; 19 January 1920 – 4 March 2020) was a Peruvian diplomat and politician who served as the fifth secretary-general of the United Nations from 1982 to 1991. He later served as prime min ...

and President of South Africa F W de Klerk, who jointly conferred formal independence on Namibia. United States Secretary of State

The United States secretary of state (SecState) is a member of the executive branch of the federal government of the United States and the head of the U.S. Department of State.

The secretary of state serves as the principal advisor to the ...

James Baker

James Addison Baker III (born April 28, 1930) is an American attorney, diplomat and statesman. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party, he served as the 10th White House chief of staff and 67th United States secretary ...

arrived to Namibia on 19 March to join the celebration marking Namibia's independence.

Sam Nujoma

Samuel Shafiishuna Daniel Nujoma ( ; 12May 19298February 2025) was a Namibian revolutionary, anti-apartheid activist and politician who served three terms as the first president of Namibia, from 1990 to 2005. Nujoma was a founding member and t ...

was sworn in as the first President of Namibia

The president of Namibia is the head of state and head of government of Namibia. The president directs the executive branch of the Government of Namibia, government, acts as chair of the Cabinet of Namibia, Cabinet and is the commander-in-chie ...

watched by Nelson Mandela

Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela ( , ; born Rolihlahla Mandela; 18 July 1918 – 5 December 2013) was a South African Internal resistance to apartheid, anti-apartheid activist and politician who served as the first president of South Africa f ...

(who had been released from prison shortly beforehand) and representatives from 147 countries, including 20 heads of state.

On 1 March 1994, the coastal enclave of Walvis Bay

Walvis Bay (; ; ) is a city in Namibia and the name of the bay on which it lies. It is the List of cities in Namibia, second largest city in Namibia and the largest coastal city in the country. The city covers an area of of land.

The bay is a ...

and 12 offshore islands were transferred to Namibia by South Africa. This followed three years of bilateral negotiations between the two governments and the establishment of a transitional Joint Administrative Authority (JAA) in November 1992 to administer the territory. The peaceful resolution of this territorial dispute was praised by the international community, as it fulfilled the provisions of the UNSCR 432 (1978), which declared Walvis Bay to be an integral part of Namibia.

Independent Namibia

Since independence Namibia has successfully completed the transition from white minority apartheid rule to a democratic society. Multiparty democracy was introduced and has been maintained, with local, regional and national elections held regularly. Several registered political parties are active and represented in the National Assembly, although

Since independence Namibia has successfully completed the transition from white minority apartheid rule to a democratic society. Multiparty democracy was introduced and has been maintained, with local, regional and national elections held regularly. Several registered political parties are active and represented in the National Assembly, although SWAPO

The South West Africa People's Organisation (SWAPO ; , SWAVO; , SWAVO), officially known as the SWAPO Party of Namibia, is a political party and former independence movement in Namibia (formerly South West Africa). Founded in 1960, it has been ...

Party has won every election since independence. The transition from the 15-year rule of President Sam Nujoma

Samuel Shafiishuna Daniel Nujoma ( ; 12May 19298February 2025) was a Namibian revolutionary, anti-apartheid activist and politician who served three terms as the first president of Namibia, from 1990 to 2005. Nujoma was a founding member and t ...

to his successor, Hifikepunye Pohamba

Hifikepunye Lucas Pohamba (born 18 August 1935) is a Namibian politician who served as the second president of Namibia from 21 March 2005 to 21 March 2015. He won the 2004 Namibian presidential election, 2004 presidential election overwhelming ...

in 2005 went smoothly.

Namibian government has promoted a policy of national reconciliation and issued an amnesty for those who had fought on either side during the liberation war. The civil war in Angola

Angola, officially the Republic of Angola, is a country on the west-Central Africa, central coast of Southern Africa. It is the second-largest Portuguese-speaking world, Portuguese-speaking (Lusophone) country in both total area and List of c ...

had a limited impact on Namibians living in the north of the country. In 1998, Namibia Defence Force

The Namibian Defence Force (NDF) comprises the national military forces of Namibia. It was created when the country, then known as South West Africa, gained independence from apartheid South Africa in 1990. Chapter 15 of the Constitution of Nami ...

(NDF) troops were sent to the Democratic Republic of the Congo

The Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), also known as the DR Congo, Congo-Kinshasa, or simply the Congo (the last ambiguously also referring to the neighbouring Republic of the Congo), is a country in Central Africa. By land area, it is t ...

as part of a Southern African Development Community

The Southern African Development Community (SADC) is an inter-governmental organization headquartered in Gaborone, Botswana.

Goals

The SADC's goal is to further regional socio-economic cooperation and integration as well as political and se ...

(SADC) contingent. In August 1999, a secessionist attempt in the northeastern Caprivi region was successfully quashed.

Re-election of Sam Nujoma

Sam Nujoma won the presidential elections of 1994 with 76.34% of the votes. There was only one other candidate, Mishake Muyongo of the DTA. In 1998, with one year until the scheduled presidential election when Sam Nujoma would not be allowed to participate in since he had already served the two terms that the constitution allows, SWAPO amended the constitution, allowing three terms instead of two. They were able to do this since SWAPO had a two-thirds majority in both theNational Assembly of Namibia

The National Assembly is the lower chamber of Namibia's bicameral Parliament. Its laws must be approved by the National Council, the upper house. Since 2014, it has a total of 104 members. 96 members are directly elected through a system of cl ...

and the National Council, which is the minimum needed to amend the constitution.

Sam Nujoma was reelected as president in 1999, winning the election, that had a 62.1% turnout with 76.82%. Second was Ben Ulenga

Ben Ulenga (born Benjamin Crispus Ulenga on June 22, 1952Profi ...

from the Congress of Democrats

The Congress of Democrats (CoD) is a Namibian opposition party without representation in the National Assembly and was led by Ben Ulenga from 2004 to 2015. It was established in 1999, prior to that year's general elections, and started off w ...

(COD), that won 10.49% of the votes.

Ben Ulenga is a former SWAPO member and Deputy Minister

Deputy minister is a title borne by politicians or officials in certain countries governed under a parliamentary system. A deputy minister is positioned in some way "under" a minister, who is a full member of Cabinet, in charge of a particular sta ...

of Environment and Tourism, and High Commissioner to the United Kingdom.

He left SWAPO and became one of the founding members of COD in 1998, after clashing with his party on several questions. He did not approve of the amendment to the constitution, and criticised Namibia's involvement in Congo.

Nujoma was succeeded as President of Namibia by Hifikepunye Pohamba

Hifikepunye Lucas Pohamba (born 18 August 1935) is a Namibian politician who served as the second president of Namibia from 21 March 2005 to 21 March 2015. He won the 2004 Namibian presidential election, 2004 presidential election overwhelming ...

in 2005.

Land reform

One of SWAPO's policies, that had been formulated long before the party came into power, wasland reform

Land reform (also known as agrarian reform) involves the changing of laws, regulations, or customs regarding land ownership, land use, and land transfers. The reforms may be initiated by governments, by interested groups, or by revolution.

Lan ...

. Namibia's colonial and Apartheid

Apartheid ( , especially South African English: , ; , ) was a system of institutionalised racial segregation that existed in South Africa and South West Africa (now Namibia) from 1948 to the early 1990s. It was characterised by an ...

past had resulted in a situation where about 20 percent of the population owned about 75 percent of all the land.

Land was supposed to be redistributed mostly from the white minority to previously landless communities and ex-combatants. The land reform has been slow, mainly because Namibia's constitution only allows land to be bought from farmers willing to sell. Also, the price of land is very high in Namibia, which further complicates the matter. Squatting

Squatting is the action of occupying an abandoned or unoccupied area of land or a building (usually residential) that the squatter does not own, rent or otherwise have lawful permission to use. The United Nations estimated in 2003 that there wer ...

occurs when internal migrants move to the cities and live in informal settlements

Informal housing or informal settlement can include any form of housing, shelter, or settlement (or lack thereof) which is illegal, falls outside of government control or regulation, or is not afforded protection by the state. As such, the info ...

.

President Sam Nujoma has been vocal in his support of Zimbabwe

file:Zimbabwe, relief map.jpg, upright=1.22, Zimbabwe, relief map

Zimbabwe, officially the Republic of Zimbabwe, is a landlocked country in Southeast Africa, between the Zambezi and Limpopo Rivers, bordered by South Africa to the south, Bots ...

and its president Robert Mugabe

Robert Gabriel Mugabe (; ; 21 February 1924 – 6 September 2019) was a Zimbabwean revolutionary and politician who served as Prime Minister of Zimbabwe from 1980 to 1987 and then as President from 1987 to 2017. He served as Leader of th ...

. During the land crisis in Zimbabwe, where the government confiscated white farmers' land by force, fears rose among the white minority and the western world that the same method would be used in Namibia.

Involvement in conflicts in Angola and DRC

In 1999 Namibia signed a mutual defence pact with its northern neighbourAngola

Angola, officially the Republic of Angola, is a country on the west-Central Africa, central coast of Southern Africa. It is the second-largest Portuguese-speaking world, Portuguese-speaking (Lusophone) country in both total area and List of c ...

.

This affected the Angolan Civil War

The Angolan Civil War () was a civil war in Angola, beginning in 1975 and continuing, with interludes, until 2002. The war began immediately after Angola became independent from Portugal in November 1975. It was a power struggle between two for ...

that had been ongoing since Angola's independence in 1975. Both being leftist movements, SWAPO wanted to support the ruling party MPLA

The People's Movement for the Liberation of Angola (, abbr. MPLA), from 1977–1990 called the People's Movement for the Liberation of Angola – Labour Party (), is an Angolan social democratic political party. The MPLA fought against the P ...

in Angola to fight the rebel movement UNITA

The National Union for the Total Independence of Angola (, abbr. UNITA) is the second-largest political party in Angola. Founded in 1966, UNITA fought alongside the People's Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA) and the National Liberat ...

, whose stronghold was in southern Angola. The defence pact allowed Angolan troops to use Namibian territory when attacking UNITA.

The Angolan civil war resulted in a large number of Angolan refugees coming to Namibia. At its peak in 2001 there were over 30,000 Angolan refugees in Namibia. The calmer situation in Angola has made it possible for many of them to return to their home with the help of UNHCR

The Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) is a United Nations agency mandated to aid and Humanitarian protection, protect refugees, Internally displaced person, forcibly displaced communities, and Statelessness, s ...

, and in 2004 only 12,600 remained in Namibia.

Most of them reside in the refugee camp

A refugee camp is a temporary Human settlement, settlement built to receive refugees and people in refugee-like situations. Refugee camps usually accommodate displaced people who have fled their home country, but camps are also made for in ...

Osire Osire is a refugee camp in central Namibia, situated 200 km north of the capital Windhoek next to the main road C30 road (Namibia), C30 from Gobabis to Otjiwarongo. It was established in 1992 to accommodate refugees from Angola, Burundi, the Democra ...

north of Windhoek

Windhoek (; ; ) is the capital and largest city of Namibia. It is located in central Namibia in the Khomas Highland plateau area, at around above sea level, almost exactly at the country's geographical centre. The population of Windhoek, which ...

.

Namibia also intervened in the Second Congo War

The Second Congo War, also known as Africa's World War or the Great War of Africa, was a major conflict that began on 2 August 1998, in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, just over a year after the First Congo War. The war initially erupted ...

, sending troops in support of the Democratic Republic of Congo

The Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), also known as the DR Congo, Congo-Kinshasa, or simply the Congo (the last ambiguously also referring to the neighbouring Republic of the Congo), is a country in Central Africa. By land area, it is t ...

's president Laurent-Désiré Kabila

Laurent-Désiré Kabila (; 27 November 1939 – 16 January 2001) usually known as Laurent Kabila or Kabila the Father (American English, US: ), was a Congolese rebel and politician who served as the third president of the Democratic Republic of t ...

.

The Caprivi conflict

The Caprivi conflict was an armed conflict between the Caprivi Liberation Army (CLA), a rebel group working for the secession of theCaprivi Strip

The Caprivi Strip, also known simply as Caprivi, is a geographic salient protruding from the northeastern corner of Namibia. It is bordered by Botswana to the south and Angola and Zambia to the north. Namibia, Botswana and Zambia meet at a sing ...

, and the Namibian government. It started in 1994 and had its peak in the early hours of 2 August 1999 when CLA launched an attack in Katima Mulilo