History of Macedonia (ancient kingdom) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The kingdom of Macedonia was an ancient state in what is now the Macedonian region of

The kingdom of Macedonia was an ancient state in what is now the Macedonian region of

The Greek historians

The Greek historians

northern Greece

Northern Greece ( el, Βόρεια Ελλάδα, Voreia Ellada) is used to refer to the northern parts of Greece, and can have various definitions.

Administrative regions of Greece

Administrative term

The term "Northern Greece" is widely used ...

, founded in the mid-7th century BC during the period of Archaic Greece

Archaic Greece was the period in Greek history lasting from circa 800 BC to the second Persian invasion of Greece in 480 BC, following the Greek Dark Ages and succeeded by the Classical period. In the archaic period, Greeks settled across the ...

and lasting until the mid-2nd century BC. Led first by the Argead dynasty of kings, Macedonia became a vassal state

A vassal state is any state that has a mutual obligation to a superior state or empire, in a status similar to that of a vassal in the feudal system in medieval Europe. Vassal states were common among the empires of the Near East, dating back ...

of the Achaemenid Empire

The Achaemenid Empire or Achaemenian Empire (; peo, 𐎧𐏁𐏂, , ), also called the First Persian Empire, was an ancient Iranian empire founded by Cyrus the Great in 550 BC. Based in Western Asia, it was contemporarily the largest em ...

of ancient Persia

The history of Iran is intertwined with the history of a larger region known as Greater Iran, comprising the area from Anatolia in the west to the borders of Ancient India and the Syr Darya in the east, and from the Caucasus and the Eurasian Step ...

during the reigns of Amyntas I of Macedon

Amyntas I (Greek: Ἀμύντας Aʹ; 498 BC) was king of the Ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia (c. 547 – 512 / 511 BC) and then a vassal of Darius I from 512/511 to his death 498 BC, at the time of Achaemenid Macedonia. He was a son of Alce ...

() and his son Alexander I of Macedon (). The period of Achaemenid Macedonia came to an end in roughly 479 BC with the ultimate Greek victory against the second Persian invasion of Greece

The second Persian invasion of Greece (480–479 BC) occurred during the Greco-Persian Wars, as King Xerxes I of Persia sought to conquer all of Greece. The invasion was a direct, if delayed, response to the defeat of the first Persian invasion ...

led by Xerxes I

Xerxes I ( peo, 𐎧𐏁𐎹𐎠𐎼𐏁𐎠 ; grc-gre, Ξέρξης ; – August 465 BC), commonly known as Xerxes the Great, was the fourth King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire, ruling from 486 to 465 BC. He was the son and successor of ...

and the withdrawal of Persian forces from the European mainland.

During the age of Classical Greece

Classical Greece was a period of around 200 years (the 5th and 4th centuries BC) in Ancient Greece,The "Classical Age" is "the modern designation of the period from about 500 B.C. to the death of Alexander the Great in 323 B.C." (Thomas R. Martin ...

, Perdiccas II of Macedon

Perdiccas II ( gr, Περδίκκας, Perdíkkas) was a king of Macedonia from c. 448 BC to c. 413 BC. During the Peloponnesian War, he frequently switched sides between Sparta and Athens.

Family

Perdiccas II was the son of Alexander I, he ha ...

() became directly involved in the Peloponnesian War (431–404 BC) between Classical Athens

The city of Athens ( grc, Ἀθῆναι, ''Athênai'' .tʰɛ̂ː.nai̯ Modern Greek: Αθήναι, ''Athine'' or, more commonly and in singular, Αθήνα, ''Athina'' .'θi.na during the classical period of ancient Greece (480–323 BC) wa ...

and Sparta

Sparta (Doric Greek: Σπάρτα, ''Spártā''; Attic Greek: Σπάρτη, ''Spártē'') was a prominent city-state in Laconia, in ancient Greece. In antiquity, the city-state was known as Lacedaemon (, ), while the name Sparta referred ...

, shifting his alliance from one city-state to another while attempting to retain Macedonian control over the Chalcidice

Chalkidiki (; el, Χαλκιδική , also spelled Halkidiki, is a peninsula and regional units of Greece, regional unit of Greece, part of the region of Central Macedonia, in the Geographic regions of Greece, geographic region of Macedonia (Gr ...

peninsula. His reign was also marked by conflict and temporary alliances with the Thracian

The Thracians (; grc, Θρᾷκες ''Thrāikes''; la, Thraci) were an Indo-European speaking people who inhabited large parts of Eastern and Southeastern Europe in ancient history.. "The Thracians were an Indo-European people who occupied ...

ruler Sitalces

Sitalces (Sitalkes) (; Ancient Greek: Σιτάλκης, reigned 431–424 BC) was one of the great kings of the Thracian Odrysian state. The Suda called him Sitalcus (Σίταλκος).

He was the son of Teres I, and on the sudden death of ...

of the Odrysian Kingdom

The Odrysian Kingdom (; Ancient Greek: ) was a state grouping many Thracian tribes united by the Odrysae, which arose in the early 5th century BC and existed at least until the late 1st century BC. It consisted mainly of present-day Bulgaria an ...

. He eventually made peace with Athens, thus forming an alliance between the two that carried over into the reign of Archelaus I of Macedon (). His reign brought peace, stability, and financial security to the Macedonian realm, yet his little-understood assassination (perhaps by a royal page) left the kingdom in peril and conflict. The turbulent reign of Amyntas III of Macedon () witnessed devastating invasions by both the Illyria

In classical antiquity, Illyria (; grc, Ἰλλυρία, ''Illyría'' or , ''Illyrís''; la, Illyria, ''Illyricum'') was a region in the western part of the Balkan Peninsula inhabited by numerous tribes of people collectively known as the Illyr ...

n ruler Bardylis of the Dardani

The Dardani (; grc, Δαρδάνιοι, Δάρδανοι; la, Dardani) or Dardanians were a Paleo-Balkan people, who lived in a region that was named Dardania after their settlement there. They were among the oldest Balkan peoples, and their ...

and the Chalcidian city-state of Olynthos

Olynthus ( grc, Ὄλυνθος ''Olynthos'', named for the ὄλυνθος ''olunthos'', "the fruit of the wild fig tree") was an ancient city of Chalcidice, built mostly on two flat-topped hills 30–40m in height, in a fertile plain at the he ...

, both of which were defeated with the aid of foreign powers, the city-states of Thessaly

Thessaly ( el, Θεσσαλία, translit=Thessalía, ; ancient Thessalian: , ) is a traditional geographic and modern administrative region of Greece, comprising most of the ancient region of the same name. Before the Greek Dark Ages, The ...

and Sparta, respectively. Alexander II () invaded Thessaly but failed to hold Larissa, which was captured by Pelopidas

Pelopidas (; grc-gre, Πελοπίδας; died 364 BC) was an important Theban statesman and general in Greece, instrumental in establishing the mid-fourth century Theban hegemony.

Biography

Athlete and warrior

Pelopidas was a member of a ...

of Thebes, who made peace with Macedonia on condition that they surrender noble hostages, including the future king Philip II of Macedon

Philip II of Macedon ( grc-gre, Φίλιππος ; 382 – 21 October 336 BC) was the king ('' basileus'') of the ancient kingdom of Macedonia from 359 BC until his death in 336 BC. He was a member of the Argead dynasty, founders of the a ...

().

Philip II came to power when his older brother Perdiccas III of Macedon () was defeated and killed in battle by the forces of Bardylis. With the use of skillful diplomacy, Philip II was able to make peace with the Illyrians

The Illyrians ( grc, Ἰλλυριοί, ''Illyrioi''; la, Illyrii) were a group of Indo-European-speaking peoples who inhabited the western Balkan Peninsula in ancient times. They constituted one of the three main Paleo-Balkan populations, a ...

, Thracians

The Thracians (; grc, Θρᾷκες ''Thrāikes''; la, Thraci) were an Indo-European speaking people who inhabited large parts of Eastern and Southeastern Europe in ancient history.. "The Thracians were an Indo-European people who occupied ...

, Paeonians

Paeonians were an ancient Indo-European people that dwelt in Paeonia. Paeonia was an old country whose location was to the north of Ancient Macedonia, to the south of Dardania, to the west of Thrace and to the east of Illyria, most of their la ...

, and Athenians who threatened his borders. This allowed him time to dramatically reform the Ancient Macedonian army

The army of the Kingdom of Macedon was among the greatest military forces of the ancient world. It was created and made formidable by King Philip II of Macedon; previously the army of Macedon had been of little account in the politics of the Gre ...

, establishing the Macedonian phalanx

The Macedonian phalanx ( gr, Μακεδονική φάλαγξ) was an infantry formation developed by Philip II from the classical Greek phalanx, of which the main innovation was the use of the sarissa, a 6 meter pike. It was famously commande ...

that would prove crucial to his kingdom's success in subduing Greece, with the exception of Sparta. He gradually enhanced his political power by forming marriage alliances with foreign powers, destroying the Chalcidian League in the Olynthian War (349–348 BC), and becoming an elected member of the Thessalian

Thessaly ( el, Θεσσαλία, translit=Thessalía, ; ancient Thessalian: , ) is a traditional geographic and modern administrative region of Greece, comprising most of the ancient region of the same name. Before the Greek Dark Ages, Thess ...

and Amphictyonic League

In Archaic Greece, an amphictyony ( grc-gre, ἀμφικτυονία, a "league of neighbors"), or amphictyonic league, was an ancient religious association of tribes formed before the rise of the Greek '' poleis''.

The six Dorian cities of coasta ...

s for his role in defeating Phocis

Phocis ( el, Φωκίδα ; grc, Φωκίς) is one of the regional units of Greece. It is part of the administrative region of Central Greece. It stretches from the western mountainsides of Parnassus on the east to the mountain range of Va ...

in the Third Sacred War

The Third Sacred War (356–346 BC) was fought between the forces of the Delphic Amphictyonic League, principally represented by Thebes, and latterly by Philip II of Macedon, and the Phocians. The war was caused by a large fine imposed in ...

(356–346 BC). After the Macedonian victory over a coalition led by Athens and Thebes at the 338 BC Battle of Chaeronea, Philip established the League of Corinth

The League of Corinth, also referred to as the Hellenic League (from Greek Ἑλληνικός ''Hellenikos'', "pertaining to Greece and Greeks"), was a confederation of Greek states created by Philip II in 338–337 BC. The League was creat ...

and was elected as its hegemon

Hegemony (, , ) is the political, economic, and military predominance of one state over other states. In Ancient Greece (8th BC – AD 6th ), hegemony denoted the politico-military dominance of the ''hegemon'' city-state over other city-states. ...

in anticipation of commanding a united Greek invasion of the Achaemenid Empire under Macedonian

Macedonian most often refers to someone or something from or related to Macedonia.

Macedonian(s) may specifically refer to:

People Modern

* Macedonians (ethnic group), a nation and a South Slavic ethnic group primarily associated with North M ...

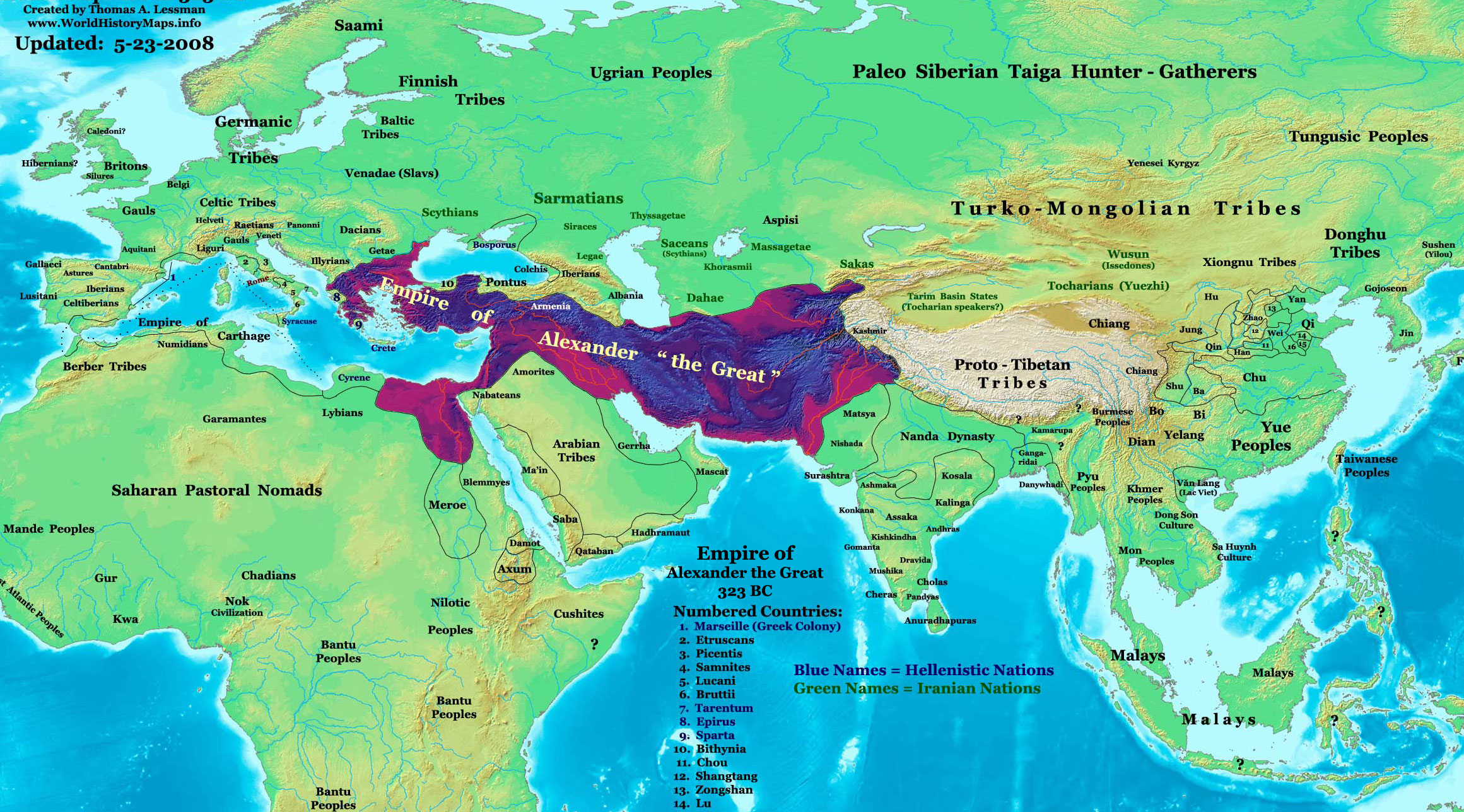

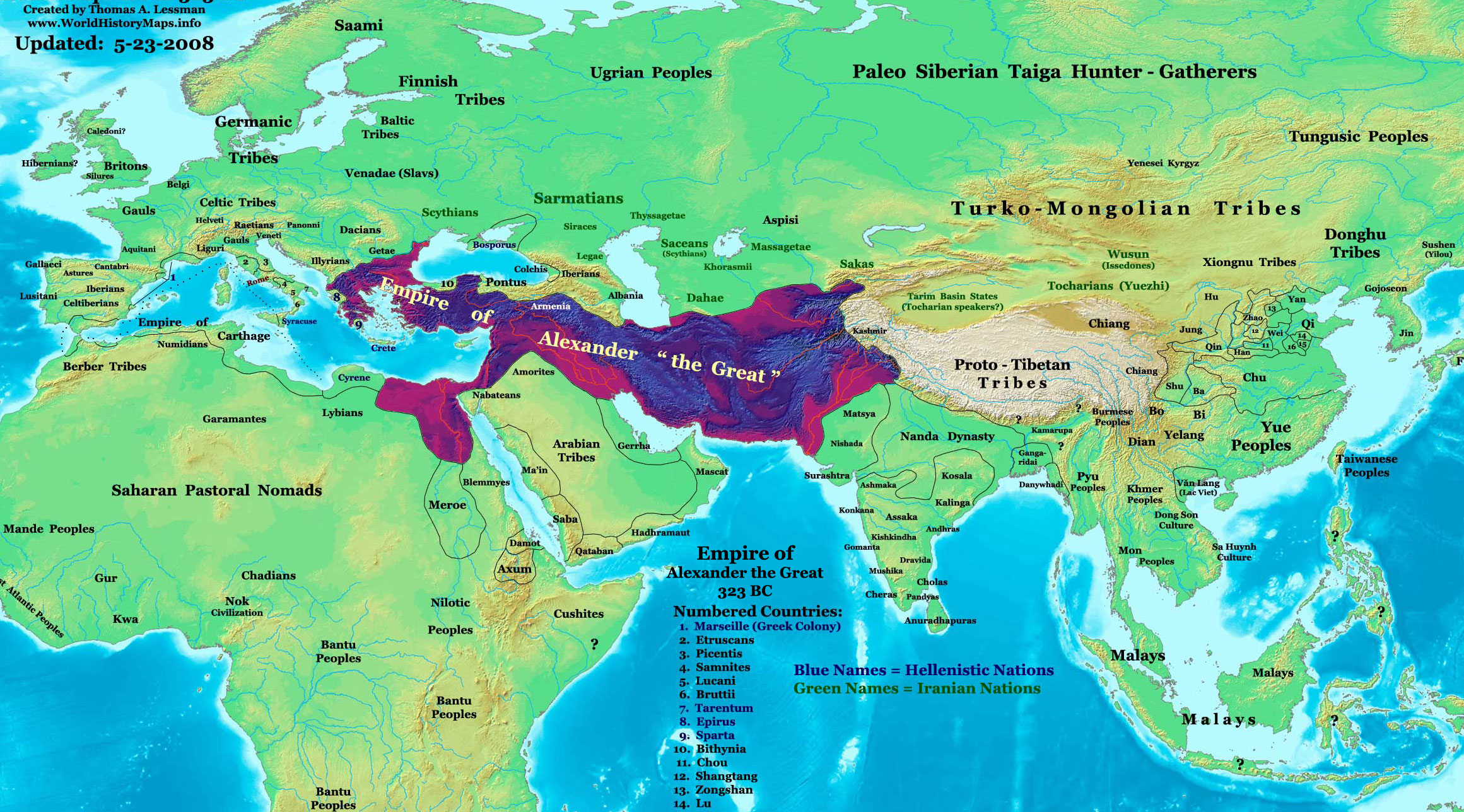

hegemony. However, when Philip II was assassinated by one of his bodyguards, he was succeeded by his son Alexander III, better known as Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon ( grc, Ἀλέξανδρος, Alexandros; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the ancient Greek kingdom of Macedon. He succeeded his father Philip II to ...

(), who invaded Achaemenid Egypt and Asia

Asia (, ) is one of the world's most notable geographical regions, which is either considered a continent in its own right or a subcontinent of Eurasia, which shares the continental landmass of Afro-Eurasia with Africa. Asia covers an ...

and toppled the rule of Darius III

Darius III ( peo, 𐎭𐎠𐎼𐎹𐎺𐎢𐏁 ; grc-gre, Δαρεῖος ; c. 380 – 330 BC) was the last Achaemenid King of Kings of Persia, reigning from 336 BC to his death in 330 BC.

Contrary to his predecessor Artaxerxes IV Arses, Dar ...

, who was forced to flee into Bactria

Bactria (; Bactrian: , ), or Bactriana, was an ancient region in Central Asia in Amu Darya's middle stream, stretching north of the Hindu Kush, west of the Pamirs and south of the Gissar range, covering the northern part of Afghanistan, so ...

(in what is now Afghanistan

Afghanistan, officially the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan,; prs, امارت اسلامی افغانستان is a landlocked country located at the crossroads of Central Asia and South Asia. Referred to as the Heart of Asia, it is bord ...

) where he was killed by one of his kinsmen, Bessus

Bessus or Bessos ( peo, *Bayaçā; grc-gre, Βήσσος), also known by his throne name Artaxerxes V ( peo, 𐎠𐎼𐎫𐎧𐏁𐏂𐎠 ; grc-gre, Ἀρταξέρξης; died summer 329 BC), was a Persian satrap of the eastern Achaemenid sa ...

. This pretender to the throne was eventually executed by Alexander, yet the latter eventually succumbed to an unknown illness at the age of 32, whose death led to the Partition of Babylon

The Partition of Babylon was the first of the conferences and ensuing agreements that divided the territories of Alexander the Great. It was held at Babylon in June 323 BC.

Alexander’s death at the age of 32 had left an empire that stretched fro ...

by his former generals, the ''diadochi

The Diadochi (; singular: Diadochus; from grc-gre, Διάδοχοι, Diádochoi, Successors, ) were the rival generals, families, and friends of Alexander the Great who fought for control over his empire after his death in 323 BC. The Wa ...

'', chief among them being Antipater

Antipater (; grc, , translit=Antipatros, lit=like the father; c. 400 BC319 BC) was a Macedonian general and statesman under the subsequent kingships of Philip II of Macedon and his son, Alexander the Great. In the wake of the collaps ...

, regent of Alexander IV of Macedon

Alexander IV ( Greek: ; 323/322– 309 BC), sometimes erroneously called Aegus in modern times, was the son of Alexander the Great (Alexander III of Macedon) and Princess Roxana of Bactria.

Birth

Alexander IV was the son of Alexande ...

(). This event ushered in the Hellenistic period

In Classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Mediterranean history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the emergence of the Roman Empire, as signified by the Battle of Actium in ...

in West Asia

Western Asia, West Asia, or Southwest Asia, is the westernmost subregion of the larger geographical region of Asia, as defined by some academics, UN bodies and other institutions. It is almost entirely a part of the Middle East, and includes A ...

and the Mediterranean world, leading to the formation of the Ptolemaic, Seleucid

The Seleucid Empire (; grc, Βασιλεία τῶν Σελευκιδῶν, ''Basileía tōn Seleukidōn'') was a Greek state in West Asia that existed during the Hellenistic period from 312 BC to 63 BC. The Seleucid Empire was founded by the M ...

, and Attalid

The Kingdom of Pergamon or Attalid kingdom was a Greek state during the Hellenistic period that ruled much of the Western part of Asia Minor from its capital city of Pergamon. It was ruled by the Attalid dynasty (; grc-x-koine, Δυναστε ...

successor kingdoms in the former territories of Alexander's empire.

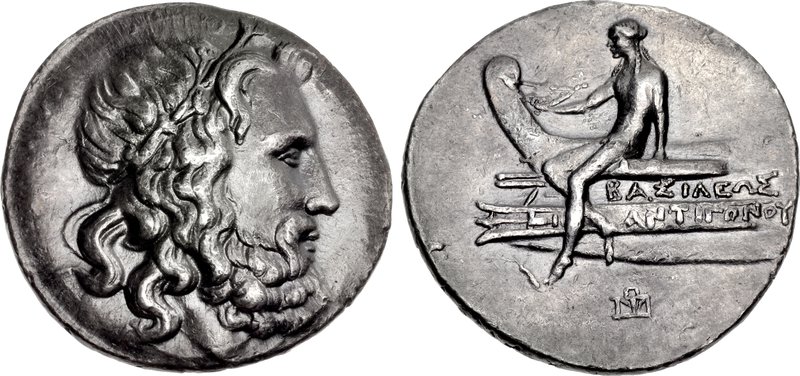

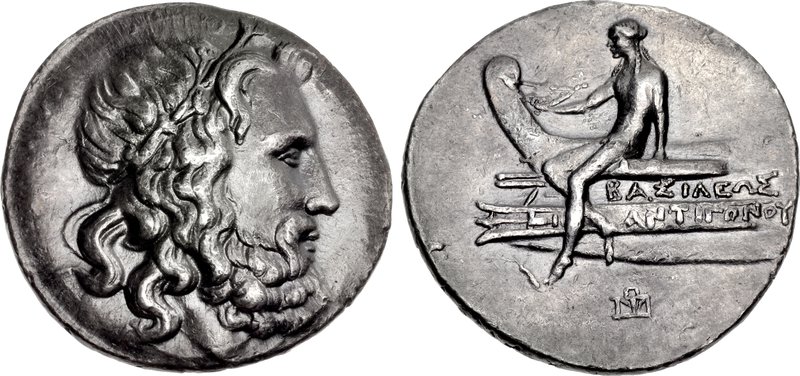

Macedonia continued its role as the dominant state of Hellenistic Greece

Hellenistic Greece is the historical period of the country following Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the annexation of the classical Greek Achaean League heartlands by the Roman Republic. This culminated ...

, yet its authority became diminished due to civil wars between the Antipatrid and nascent Antigonid dynasty

The Antigonid dynasty (; grc-gre, Ἀντιγονίδαι) was a Hellenistic dynasty of Dorian Greek provenance, descended from Alexander the Great's general Antigonus I Monophthalmus ("the One-Eyed") that ruled mainly in Macedonia.

History

...

. After surviving crippling invasions by Pyrrhus of Epirus

Pyrrhus (; grc-gre, Πύρρος ; 319/318–272 BC) was a Greek king and statesman of the Hellenistic period.Plutarch. ''Parallel Lives'',Pyrrhus... He was king of the Greek tribe of Molossians, of the royal Aeacid house, and later he became ...

, Lysimachus

Lysimachus (; Greek: Λυσίμαχος, ''Lysimachos''; c. 360 BC – 281 BC) was a Thessalian officer and successor of Alexander the Great, who in 306 BC, became King of Thrace, Asia Minor and Macedon.

Early life and career

Lysimachus was ...

, Seleucus I Nicator

Seleucus I Nicator (; ; grc-gre, Σέλευκος Νικάτωρ , ) was a Macedonian Greek general who was an officer and successor ( ''diadochus'') of Alexander the Great. Seleucus was the founder of the eponymous Seleucid Empire. In the po ...

, and the Celtic Galatians, Macedonia under the leadership of Antigonus II of Macedon () was able to subdue Athens and defend against the naval onslaught of Ptolemaic Egypt in the Chremonidean War (267–261 BC). However, the rebellion of Aratus of Sicyon in 351 BC led to the formation of the Achaean League

The Achaean League (Greek: , ''Koinon ton Akhaion'' "League of Achaeans") was a Hellenistic-era confederation of Greek city states on the northern and central Peloponnese. The league was named after the region of Achaea in the northwestern Pelop ...

, which proved to be a perennial problem for the ambitions of the Macedonian kings in mainland Greece. Macedonian power saw a resurgence under Antigonus III Doson

Antigonus III Doson ( el, Ἀντίγονος Γ΄ Δώσων, 263–221 BC) was king of Macedon from 229 BC to 221 BC. He was a member of the Antigonid dynasty.

Family background

Antigonus III Doson was a half-cousin of his predecessor, Demetr ...

(), who defeated the Spartans under Cleomenes III

Cleomenes III ( grc, Κλεομένης) was one of the two kings of Sparta from 235 to 222 BC. He was a member of the Agiad dynasty and succeeded his father, Leonidas II. He is known for his attempts to reform the Spartan state.

From 229 to ...

in the Cleomenean War

The Cleomenean WarPolybius. ''The Rise of the Roman Empire'', 2.46. (229/228–222 BC) was fought between Sparta and the Achaean League for the control of the Peloponnese. Under the leadership of king Cleomenes III, Sparta initially had the uppe ...

(229–222 BC). Although Philip V of Macedon

Philip V ( grc-gre, Φίλιππος ; 238–179 BC) was king ( Basileus) of Macedonia from 221 to 179 BC. Philip's reign was principally marked by an unsuccessful struggle with the emerging power of the Roman Republic. He would lead Macedon aga ...

() managed to defeat the Aetolian League

The Aetolian (or Aitolian) League ( grc-gre, Κοινὸν τῶν Αἰτωλῶν) was a confederation of tribal communities and cities in ancient Greece centered in Aetolia in central Greece. It was probably established during the early Hellen ...

in the Social War (220–217 BC)

The Social War, also War of the Allies and the Aetolian War, was fought from 220 BC to 217 BC between the Hellenic League under Philip V of Macedon and the Aetolian League, Sparta and Elis. It was ended with the Peace of Naupactus.

Background ...

, his attempts to project Macedonian power into the Adriatic Sea

The Adriatic Sea () is a body of water separating the Italian Peninsula from the Balkans, Balkan Peninsula. The Adriatic is the northernmost arm of the Mediterranean Sea, extending from the Strait of Otranto (where it connects to the Ionian Sea) ...

and formation of a Macedonian–Carthaginian Treaty with Hannibal

Hannibal (; xpu, 𐤇𐤍𐤁𐤏𐤋, ''Ḥannibaʿl''; 247 – between 183 and 181 BC) was a Carthaginian general and statesman who commanded the forces of Carthage in their battle against the Roman Republic during the Second Pu ...

alarmed the Roman Republic

The Roman Republic ( la, Res publica Romana ) was a form of government of Rome and the era of the classical Roman civilization when it was run through public representation of the Roman people. Beginning with the overthrow of the Roman Kingd ...

, which convinced a coalition of Greek city-states to attack Macedonia while Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus ( legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

focused on defeating Hannibal in Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical ...

. Rome was ultimately victorious in the First

First or 1st is the ordinal form of the number one (#1).

First or 1st may also refer to:

*World record, specifically the first instance of a particular achievement

Arts and media Music

* 1$T, American rapper, singer-songwriter, DJ, and reco ...

(214–205 BC) and Second Macedonian War

The Second Macedonian War (200–197 BC) was fought between Macedon, led by Philip V of Macedon, and Rome, allied with Pergamon and Rhodes. Philip was defeated and was forced to abandon all possessions in southern Greece, Thrace and As ...

(200–197 BC) against Philip V, who was also defeated in the Cretan War (205–200 BC)

The Cretan War (205–200 BC) was fought by King Philip V of Macedon, the Aetolian League, many Cretan cities (of which Olous and Hierapytna were the most important) and Spartan pirates against the forces of Rhodes and later Attalus I o ...

by a coalition led by Rhodes

Rhodes (; el, Ρόδος , translit=Ródos ) is the largest and the historical capital of the Dodecanese islands of Greece. Administratively, the island forms a separate municipality within the Rhodes regional unit, which is part of the S ...

. Macedonia was forced to relinquish its holdings in Greece outside of Macedonia proper, while the Third Macedonian War

The Third Macedonian War (171–168 BC) was a war fought between the Roman Republic and King Perseus of Macedon. In 179 BC, King Philip V of Macedon died and was succeeded by his ambitious son Perseus. He was anti-Roman and stirred anti-Roman ...

(171–168 BC) succeeded in toppling the monarchy altogether, after which Rome placed Perseus of Macedon

Perseus ( grc-gre, Περσεύς; 212 – 166 BC) was the last king ('' Basileus'') of the Antigonid dynasty, who ruled the successor state in Macedon created upon the death of Alexander the Great. He was the last Antigonid to rule Macedon, aft ...

() under house arrest and established four client state

A client state, in international relations, is a state that is economically, politically, and/or militarily subordinate to another more powerful state (called the "controlling state"). A client state may variously be described as satellite sta ...

republics in Macedonia. In an attempt to dissuade rebellion in Macedonia, Rome imposed stringent constitutions in these states that limited their economic growth and interactivity. However, Andriscus

Andriscus ( grc, Ἀνδρίσκος, ''Andrískos''; 154/153 BC – 146 BC), also often referenced as Pseudo-Philip, was a Greek pretender who became the last independent king of Macedon in 149 BC as Philip VI ( grc-gre, Φίλιππος, ''P ...

, a pretender to the throne claiming descent from the Antigonids, briefly revived the Macedonian monarchy during the Fourth Macedonian War

The Fourth Macedonian War (150–148 BC) was fought between Macedon, led by the pretender Andriscus, and the Roman Republic. It was the last of the Macedonian Wars, and was the last war to seriously threaten Roman control of Greece until the ...

(150–148 BC). His forces were crushed at the second Battle of Pydna by the Roman general Quintus Caecilius Metellus Macedonicus

Quintus Caecilius Metellus Macedonicus (c. 188 BC – 116 BC/115 BC) was a statesman and general of the Roman Republic during the second century BC. He was praetor in 148 BC, consul in 143 BC, the Proconsul of Hispania Citerior in 142 BC an ...

, leading to the establishment of the Roman province of Macedonia

Macedonia ( grc-gre, Μακεδονία) was a province of the Roman Empire, encompassing the territory of the former Antigonid Kingdom of Macedonia, which had been conquered by Rome in 168 BC at the conclusion of the Third Macedonian War. The p ...

and the initial period of Roman Greece

Greece in the Roman era describes the Roman conquest of Greece, as well as the period of Greek history when Greece was dominated first by the Roman Republic and then by the Roman Empire.

The Roman era of Greek history began with the Corinthia ...

.

Early history and legend

The Greek historians

The Greek historians Herodotus

Herodotus ( ; grc, , }; BC) was an ancient Greek historian and geographer from the Greek city of Halicarnassus, part of the Persian Empire (now Bodrum, Turkey) and a later citizen of Thurii in modern Calabria ( Italy). He is known for ...

and Thucydides

Thucydides (; grc, , }; BC) was an Athenian historian and general. His '' History of the Peloponnesian War'' recounts the fifth-century BC war between Sparta and Athens until the year 411 BC. Thucydides has been dubbed the father of " scient ...

reported the legend

A legend is a genre of folklore that consists of a narrative featuring human actions, believed or perceived, both by teller and listeners, to have taken place in human history. Narratives in this genre may demonstrate human values, and possess ...

that the Macedonian kings of the Argead dynasty were descendants of Temenus

In Greek mythology, Temenus ( el, Τήμενος, ''Tḗmenos'') was a son of Aristomachus and brother of Cresphontes and Aristodemus.

Temenus was a great-great-grandson of Heracles and helped lead the fifth and final attack on Mycenae in the ...

of Argos, Peloponnese, who was believed to have had the mythical Heracles

Heracles ( ; grc-gre, Ἡρακλῆς, , glory/fame of Hera), born Alcaeus (, ''Alkaios'') or Alcides (, ''Alkeidēs''), was a divine hero in Greek mythology, the son of Zeus and Alcmene, and the foster son of Amphitryon.By his adopt ...

as one of his ancestors.; ; . The legend states that three brothers and descendants of Temenus wandered from Illyria

In classical antiquity, Illyria (; grc, Ἰλλυρία, ''Illyría'' or , ''Illyrís''; la, Illyria, ''Illyricum'') was a region in the western part of the Balkan Peninsula inhabited by numerous tribes of people collectively known as the Illyr ...

to Upper Macedonia

Upper Macedonia (Greek: Ἄνω Μακεδονία, ''Ánō Makedonía'') is a geographical and tribal term to describe the upper/western of the two parts in which, together with Lower Macedonia, the ancient kingdom of Macedon was roughly divided. ...

, where a local king nearly had them killed and forced into exile due to an omen that the youngest, Perdiccas

Perdiccas ( el, Περδίκκας, ''Perdikkas''; 355 BC – 321/320 BC) was a general of Alexander the Great. He took part in the Macedonian campaign against the Achaemenid Empire, and, following Alexander's death in 323 BC, rose to become ...

, would become king. The latter eventually obtained the title after settling near the alleged gardens of Midas

Midas (; grc-gre, Μίδας) was the name of a king in Phrygia with whom several myths became associated, as well as two later members of the Phrygian royal house.

The most famous King Midas is popularly remembered in Greek mythology for his ...

next to Mount Bermius in Lower Macedonia. Other legends, mentioned by the Roman historians Livy

Titus Livius (; 59 BC – AD 17), known in English as Livy ( ), was a Roman historian. He wrote a monumental history of Rome and the Roman people, titled , covering the period from the earliest legends of Rome before the traditional founding in ...

, Velleius

Marcus Velleius Paterculus (; c. 19 BC – c. AD 31) was a Roman historian, soldier and senator. His Roman history, written in a highly rhetorical style, covered the period from the end of the Trojan War to AD 30, but is most useful for the pe ...

and Justin and by the Greek biographer Plutarch

Plutarch (; grc-gre, Πλούταρχος, ''Ploútarchos''; ; – after AD 119) was a Greek Middle Platonist philosopher, historian, biographer, essayist, and priest at the Temple of Apollo in Delphi. He is known primarily for his ...

and the Greek geographer Pausanias stated that Caranus of Macedon was the first Macedonian king and that he was succeeded by Perdiccas I.. Greeks of the Classical period generally accepted the origin story provided by Herodotus, or another involving lineage from Zeus

Zeus or , , ; grc, Δῐός, ''Diós'', label=genitive Boeotian Aeolic and Laconian grc-dor, Δεύς, Deús ; grc, Δέος, ''Déos'', label=genitive el, Δίας, ''Días'' () is the sky and thunder god in ancient Greek religion, ...

, chief god of the Greek pantheon, lending credence to the idea that the Macedonian ruling house possessed the divine right of kings

In European Christianity, the divine right of kings, divine right, or God's mandation is a political and religious doctrine of political legitimacy of a monarchy. It stems from a specific metaphysical framework in which a monarch is, befor ...

. Herodotus wrote that Alexander I of Macedon () convinced the ''Hellanodikai The ''Hellanodikai'' ( grc, , literally meaning ''Judges of the Greeks''; sing. Ἑλλανοδίκας Ancient Olympic Games that his Argive lineage could be traced back to Temenus, and thus his perceived Greek identity permitted him to enter the Olympic competitions.

Very little is known about the first five kings of Macedonia (or the first eight kings depending on which royal chronology is accepted). There is much greater evidence for the reigns of  The kingdom was situated in the fertile alluvial plain, watered by the rivers Haliacmon and Axius, called Lower Macedonia, north of

The kingdom was situated in the fertile alluvial plain, watered by the rivers Haliacmon and Axius, called Lower Macedonia, north of

Alexander I, who Herodotus claimed was entitled ''

Alexander I, who Herodotus claimed was entitled '' Perdiccas II was obliged to send aid to the Athenian general

Perdiccas II was obliged to send aid to the Athenian general

Historical sources offer wildly different and confused accounts as to who assassinated Archelaus I, although it likely involved a

Historical sources offer wildly different and confused accounts as to who assassinated Archelaus I, although it likely involved a

The exact date in which Philip II initiated reforms to radically transform the Macedonian army's organization, equipment, and training is unknown, including the formation of the

The exact date in which Philip II initiated reforms to radically transform the Macedonian army's organization, equipment, and training is unknown, including the formation of the  After campaigning against the Thracian ruler Cersobleptes, Philip II began his war against the Chalcidian League in 349 BC, which had been reestablished in 375 BC following a temporary disbandment. Despite an Athenian intervention by Charidemus, Olynthos was captured by Philip II in 348 BC, whereupon he sold its inhabitants into slavery, bringing back some Athenian citizens to Macedonia as slaves as well. The Athenians, especially in a series of speeches by

After campaigning against the Thracian ruler Cersobleptes, Philip II began his war against the Chalcidian League in 349 BC, which had been reestablished in 375 BC following a temporary disbandment. Despite an Athenian intervention by Charidemus, Olynthos was captured by Philip II in 348 BC, whereupon he sold its inhabitants into slavery, bringing back some Athenian citizens to Macedonia as slaves as well. The Athenians, especially in a series of speeches by  After his election by the League of Corinth as their commander-in-chief (''

After his election by the League of Corinth as their commander-in-chief (''

Before Philip II was assassinated in the summer of 336 BC, relations with his son Alexander had degenerated to the point where he excluded him entirely from his planned invasion of Asia, choosing instead for him to act as regent of Greece and deputy ''hegemon'' of the League of Corinth. This, alongside his mother Olympias' apparent concern over Philip II bearing another potential heir with his new wife Cleopatra Eurydice, have led scholars to wrangle over the idea of her and Alexander's possible roles in Philip's murder. Nonetheless, Alexander III () was immediately proclaimed king by an assembly of the army and leading aristocrats, chief among them being

Before Philip II was assassinated in the summer of 336 BC, relations with his son Alexander had degenerated to the point where he excluded him entirely from his planned invasion of Asia, choosing instead for him to act as regent of Greece and deputy ''hegemon'' of the League of Corinth. This, alongside his mother Olympias' apparent concern over Philip II bearing another potential heir with his new wife Cleopatra Eurydice, have led scholars to wrangle over the idea of her and Alexander's possible roles in Philip's murder. Nonetheless, Alexander III () was immediately proclaimed king by an assembly of the army and leading aristocrats, chief among them being  Despite his skills as a commander, Alexander perhaps undercut his own rule by demonstrating signs of

Despite his skills as a commander, Alexander perhaps undercut his own rule by demonstrating signs of  When Alexander the Great died at Babylon in 323 BC, his mother Olympias immediately accused Antipater and his faction with poisoning him, although there is no evidence to confirm this. With no official

When Alexander the Great died at Babylon in 323 BC, his mother Olympias immediately accused Antipater and his faction with poisoning him, although there is no evidence to confirm this. With no official  A council of the army convened immediately after Alexander's death in Babylon, naming Philip III as king and the

A council of the army convened immediately after Alexander's death in Babylon, naming Philip III as king and the

Pyrrhus lost much of his support among the Macedonians in 273 BC when his unruly Gallic mercenaries plundered the royal cemetery of Aigai. Pyrrhus pursued Antigonus II in Greece, yet while he was occupied with the war in the

Pyrrhus lost much of his support among the Macedonians in 273 BC when his unruly Gallic mercenaries plundered the royal cemetery of Aigai. Pyrrhus pursued Antigonus II in Greece, yet while he was occupied with the war in the  However, in 251 BC, Aratus of Sicyon led a rebellion against Antigonus II and in 250 BC, Ptolemy II openly threw his support behind the self-proclaimed king Alexander of Corinth. Although Alexander died in 246 BC and Antigonus was able to score a naval victory against the Ptolemies at the Battle of Andros, the Macedonians lost the Acrocorinth to the forces of Aratus in 243 BC, followed by the induction of Corinth into the Achaean League. Antigonus II finally made peace with the Achaean League in a treaty of 240 BC, ceding the territories that he had lost in Greece. Antigonus II died in 239 BC and was succeeded by his son Demetrius II of Macedon (). Seeking an alliance with Macedonia to defend against the Aetolians, the

However, in 251 BC, Aratus of Sicyon led a rebellion against Antigonus II and in 250 BC, Ptolemy II openly threw his support behind the self-proclaimed king Alexander of Corinth. Although Alexander died in 246 BC and Antigonus was able to score a naval victory against the Ptolemies at the Battle of Andros, the Macedonians lost the Acrocorinth to the forces of Aratus in 243 BC, followed by the induction of Corinth into the Achaean League. Antigonus II finally made peace with the Achaean League in a treaty of 240 BC, ceding the territories that he had lost in Greece. Antigonus II died in 239 BC and was succeeded by his son Demetrius II of Macedon (). Seeking an alliance with Macedonia to defend against the Aetolians, the  Although the Achaean League had been fighting Macedonia for decades, Aratus sent an embassy to Antigonus III in 226 BC seeking an unexpected alliance now that the reformist king

Although the Achaean League had been fighting Macedonia for decades, Aratus sent an embassy to Antigonus III in 226 BC seeking an unexpected alliance now that the reformist king

In 215 BC, at the height of the

In 215 BC, at the height of the  While Philip V was ensnared in a conflict with several Greek maritime powers, Rome viewed these unfolding events as an opportunity to punish a former ally of Hannibal, come to the aid of its Greek allies, and commit to a war that perhaps required a limited amount of resources in order to achieve victory. With

While Philip V was ensnared in a conflict with several Greek maritime powers, Rome viewed these unfolding events as an opportunity to punish a former ally of Hannibal, come to the aid of its Greek allies, and commit to a war that perhaps required a limited amount of resources in order to achieve victory. With  While becoming increasingly entangled in Greek affairs and failing to please all sides in various disputes, the Roman Senate decided in 184/183 BC to force Philip V to abandon the cities of Aenus and Maronea, since these were declared free cities in the Treaty of Apamea. It also assuaged the fears of Eumenes II that these Macedonian-held settlements would no longer threaten the security of his possessions in the Hellespont.

While becoming increasingly entangled in Greek affairs and failing to please all sides in various disputes, the Roman Senate decided in 184/183 BC to force Philip V to abandon the cities of Aenus and Maronea, since these were declared free cities in the Treaty of Apamea. It also assuaged the fears of Eumenes II that these Macedonian-held settlements would no longer threaten the security of his possessions in the Hellespont.

Ancient Macedonia

a

Livius

by Jona Lendering * (''Philip, Demosthenes and the Fall of the Polis''). Yale University courses

Lecture 24

''Introduction to Ancient Greek History''

Heracles to Alexander The Great: Treasures From The Royal Capital of Macedon, A Hellenic Kingdom in the Age of Democracy

Ashmolean Museum of Art and Archaeology, University of Oxford {{Ancient Syria and Mesopotamia Macedonia (ancient kingdom) Ancient Macedonia Hellenistic Macedonia

Amyntas I of Macedon

Amyntas I (Greek: Ἀμύντας Aʹ; 498 BC) was king of the Ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia (c. 547 – 512 / 511 BC) and then a vassal of Darius I from 512/511 to his death 498 BC, at the time of Achaemenid Macedonia. He was a son of Alce ...

() and his successor Alexander I, especially due to the aid given by the latter to the Persian commander Mardonius at the Battle of Platea in 479 BC, during the Greco-Persian Wars

The Greco-Persian Wars (also often called the Persian Wars) were a series of conflicts between the Achaemenid Empire and Greek city-states that started in 499 BC and lasted until 449 BC. The collision between the fractious political world of th ...

. Although stating that the first several kings listed by Herodotus were most likely legendary figures, historian Robert Malcolm Errington uses the rough estimate of twenty-five years for the reign of each of these kings to assume that the capital Aigai (modern Vergina

Vergina ( el, Βεργίνα, ''Vergína'' ) is a small town in northern Greece, part of Veria municipality in Imathia, Central Macedonia. Vergina was established in 1922 in the aftermath of the population exchanges after the Treaty of ...

) could have been under their rule since roughly the mid-7th century BC, during the Archaic period.

The kingdom was situated in the fertile alluvial plain, watered by the rivers Haliacmon and Axius, called Lower Macedonia, north of

The kingdom was situated in the fertile alluvial plain, watered by the rivers Haliacmon and Axius, called Lower Macedonia, north of Mount Olympus

Mount Olympus (; el, Όλυμπος, Ólympos, also , ) is the highest mountain in Greece. It is part of the Olympus massif near the Thermaic Gulf of the Aegean Sea, located in the Olympus Range on the border between Thessaly and Macedonia, be ...

. Around the time of Alexander I, the Argead Macedonians started to expand into Upper Macedonia, lands inhabited by independent Greek tribes like the Lyncestae and the Elimiotae, and to the west, beyond the Axius river, into the Emathia, Eordaia

Eordaia ( el, Εορδαία) is a municipality in the Kozani regional unit, Greece. The seat of the municipality is the town Ptolemaida. The municipality has an area of 708.807 km2. The population was 45,592 in 2011.

Municipality

The mun ...

, Bottiaea

Bottiaea (Greek: ''Bottiaia'') was a geographical region of ancient Macedonia and an administrative district of the Macedonian Kingdom. It was previously inhabited by the Bottiaeans, a people of uncertain origin, later expelled by the Macedoni ...

, Mygdonia

Mygdonia (; el, Μυγδονία / Μygdonia) was an ancient territory, part of Ancient Thrace, later conquered by Macedon, which comprised the plains around Therma (Thessalonica) together with the valleys of Klisali and Besikia, including the ...

, Crestonia

Crestonia (or Crestonice) ( el, Κρηστωνία) was an ancient region immediately north of Mygdonia. The Echeidorus river, which flowed through Mygdonia into the Thermaic Gulf, had its source in Crestonia. It was partly occupied by a remnant of ...

and Almopia

Almopia ( el, Αλμωπία), or Enotia, also known in the Middle Ages as Moglena (Greek: Μογλενά, Macedonian and Bulgarian: Меглен or Мъглен), is a municipality and a former province (επαρχία) of the Pella regional uni ...

; regions settled by, among others, many Thracian tribes

This is a list of ancient tribes in Thrace and Dacia ( grc, Θρᾴκη, Δακία) including possibly or partly Thracian or Dacian tribes, and non-Thracian or non-Dacian tribes that inhabited the lands known as Thrace and Dacia. A great number o ...

. To the north of Macedonia lay various non-Greek peoples such as the Paeonians

Paeonians were an ancient Indo-European people that dwelt in Paeonia. Paeonia was an old country whose location was to the north of Ancient Macedonia, to the south of Dardania, to the west of Thrace and to the east of Illyria, most of their la ...

due north, the Thracians

The Thracians (; grc, Θρᾷκες ''Thrāikes''; la, Thraci) were an Indo-European speaking people who inhabited large parts of Eastern and Southeastern Europe in ancient history.. "The Thracians were an Indo-European people who occupied ...

to the northeast, and the Illyrians

The Illyrians ( grc, Ἰλλυριοί, ''Illyrioi''; la, Illyrii) were a group of Indo-European-speaking peoples who inhabited the western Balkan Peninsula in ancient times. They constituted one of the three main Paleo-Balkan populations, a ...

, with whom the Macedonians were frequently in conflict, to the northwest. To the south lay Thessaly

Thessaly ( el, Θεσσαλία, translit=Thessalía, ; ancient Thessalian: , ) is a traditional geographic and modern administrative region of Greece, comprising most of the ancient region of the same name. Before the Greek Dark Ages, The ...

, with whose inhabitants the Macedonians had much in common, both culturally and politically, while to the west lay Epirus

sq, Epiri rup, Epiru

, native_name_lang =

, settlement_type = Historical region

, image_map = Epirus antiquus tabula.jpg

, map_alt =

, map_caption = Map of ancient Epirus by Heinrich ...

, with whom the Macedonians had a peaceful relationship and in the 4th century BC formed an alliance against Illyrian raids. Prior to the 4th century BC, the kingdom covered a region approximately corresponding to the western

Western may refer to:

Places

*Western, Nebraska, a village in the US

* Western, New York, a town in the US

*Western Creek, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western Junction, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western world, countries that i ...

and central

Central is an adjective usually referring to being in the center of some place or (mathematical) object.

Central may also refer to:

Directions and generalised locations

* Central Africa, a region in the centre of Africa continent, also known a ...

parts of the region of Macedonia in modern Greece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders wit ...

.

After Darius I of Persia

Darius I ( peo, 𐎭𐎠𐎼𐎹𐎺𐎢𐏁 ; grc-gre, Δαρεῖος ; – 486 BCE), commonly known as Darius the Great, was a Persian ruler who served as the third King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire, reigning from 522 BCE until his ...

() launched a military campaign against the Scythians

The Scythians or Scyths, and sometimes also referred to as the Classical Scythians and the Pontic Scythians, were an ancient Eastern

* : "In modern scholarship the name 'Sakas' is reserved for the ancient tribes of northern and eastern Cent ...

in Europe in 513 BC, he left behind his general Megabazus

Megabazus (Old Persian: ''Bagavazdā'' or ''Bagabāzu'', grc, Μεγαβάζος), son of Megabates, was a highly regarded Persian general under Darius, to whom he was a first-degree cousin. Most of the information about Megabazus comes from ...

to quell the Paeonians, Thracians, and coastal Greek city-states of the southern Balkans

The Balkans ( ), also known as the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with various geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throughout the who ...

. In 512/511 BC Megabazus sent envoys demanding Macedonian submission as a vassal state

A vassal state is any state that has a mutual obligation to a superior state or empire, in a status similar to that of a vassal in the feudal system in medieval Europe. Vassal states were common among the empires of the Near East, dating back ...

to the Achaemenid Empire

The Achaemenid Empire or Achaemenian Empire (; peo, 𐎧𐏁𐏂, , ), also called the First Persian Empire, was an ancient Iranian empire founded by Cyrus the Great in 550 BC. Based in Western Asia, it was contemporarily the largest em ...

of ancient Persia

The history of Iran is intertwined with the history of a larger region known as Greater Iran, comprising the area from Anatolia in the west to the borders of Ancient India and the Syr Darya in the east, and from the Caucasus and the Eurasian Step ...

, to which Amyntas I responded by formally accepting the hegemony

Hegemony (, , ) is the political, economic, and military predominance of one state over other states. In Ancient Greece (8th BC – AD 6th ), hegemony denoted the politico-military dominance of the ''hegemon'' city-state over other city-states. ...

of the Persian king of kings. This began the period of Achaemenid Macedonia, which lasted for roughly three decades. The Macedonian kingdom was largely autonomous

In developmental psychology and moral, political, and bioethical philosophy, autonomy, from , ''autonomos'', from αὐτο- ''auto-'' "self" and νόμος ''nomos'', "law", hence when combined understood to mean "one who gives oneself one's ...

and outside of Persian control, but was expected to provide troops and provisions for the Achaemenid army.. Amyntas II

Amyntas II ( grc, Ἀμύντας) or Amyntas the Little, was the king of the Ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia for a short time, ''circa'' 393 BC. Thucydides describes him as a son of Philip, the brother of king Perdiccas II. He first succe ...

, son of Amyntas I's daughter Gygaea of Macedon

Gygaea ( el, Γυγαίη) was a daughter of Amyntas I and sister of Alexander I of Macedon. She was given away in marriage by her brother to the Persian General Bubares. Herodotus also mentions a son of Bubares and Gygaea, called Amyntas, wh ...

and her husband Bubares

Bubares ( el, Βουβάρης, died after 480 BC) was a Persian nobleman and engineer in the service of the Achaemenid Empire of the 5th century BC. He was one of the sons of Megabazus, and a second-degree cousin of Xerxes I.

Marriage to the s ...

, son of Megabazus, was given the Phrygia

In classical antiquity, Phrygia ( ; grc, Φρυγία, ''Phrygía'' ) was a kingdom in the west central part of Anatolia, in what is now Asian Turkey, centered on the Sangarios River. After its conquest, it became a region of the great empire ...

n city of Alabanda as an appanage

An appanage, or apanage (; french: apanage ), is the grant of an estate, title, office or other thing of value to a younger child of a sovereign, who would otherwise have no inheritance under the system of primogeniture. It was common in much ...

by Xerxes I

Xerxes I ( peo, 𐎧𐏁𐎹𐎠𐎼𐏁𐎠 ; grc-gre, Ξέρξης ; – August 465 BC), commonly known as Xerxes the Great, was the fourth King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire, ruling from 486 to 465 BC. He was the son and successor of ...

(), to secure the Persian-Macedonian marriage alliance A marriage of state is a diplomatic marriage or union between two members of different nation-states or internally, between two power blocs, usually in authoritarian societies and is a practice which dates back into ancient times, as far back as ear ...

. Persian authority over Macedonia was interrupted by the Ionian Revolt

The Ionian Revolt, and associated revolts in Aeolis, Doris, Cyprus and Caria, were military rebellions by several Greek regions of Asia Minor against Persian rule, lasting from 499 BC to 493 BC. At the heart of the rebellion was the dissatisfa ...

(499–493 BC), yet the Persian general Mardonius was able to subjugate Macedonia, bringing it under Persian rule. It is doubtful, though, that Macedonia was ever officially included within a Persian satrap

A satrap () was a governor of the provinces of the ancient Median and Achaemenid Empires and in several of their successors, such as in the Sasanian Empire and the Hellenistic empires.

The satrap served as viceroy to the king, though with cons ...

y (i.e. province). The Macedonian king Alexander I must have viewed his subordination as an opportunity to aggrandize his own position, since he used Persian military support to extend his own borders. The Macedonians provided military aid to Xerxes I during the Second Persian invasion of Greece

The second Persian invasion of Greece (480–479 BC) occurred during the Greco-Persian Wars, as King Xerxes I of Persia sought to conquer all of Greece. The invasion was a direct, if delayed, response to the defeat of the first Persian invasion ...

in 480–479 BC, which saw Macedonians and Persians fighting against a Greek coalition led by Athens

Athens ( ; el, Αθήνα, Athína ; grc, Ἀθῆναι, Athênai (pl.) ) is both the capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Greece, largest city of Greece. With a population close to four million, it is also the seventh List ...

and Sparta

Sparta (Doric Greek: Σπάρτα, ''Spártā''; Attic Greek: Σπάρτη, ''Spártē'') was a prominent city-state in Laconia, in ancient Greece. In antiquity, the city-state was known as Lacedaemon (, ), while the name Sparta referred ...

. Following the Greek victory at Salamis, the Persians sent Alexander I as an envoy to Athens, hoping to strike an alliance with their erstwhile foe, yet his diplomatic mission was rebuffed. Achaemenid control over Macedonia ceased when the Persians were ultimately defeated by the Greeks and fled the Greek mainland in Europe.

Involvement in the Classical Greek world

proxenos

Proxeny or ( grc-gre, προξενία) in ancient Greece was an arrangement whereby a citizen (chosen by the city) hosted foreign ambassadors at his own expense, in return for honorary titles from the state. The citizen was called (; plural: o ...

'' and '' euergetes'' ('benefactor') by the Athenians, cultivated a close relationship with the Greeks following the Persian defeat and withdrawal, sponsoring the erection of statues at both major panhellenic sanctuaries at Delphi

Delphi (; ), in legend previously called Pytho (Πυθώ), in ancient times was a sacred precinct that served as the seat of Pythia, the major oracle who was consulted about important decisions throughout the ancient classical world. The oracl ...

and Olympia. After his death in 454 BC, he was granted the posthumous title Alexander I 'the Philhellene' ('friend of the Greeks'), perhaps designated by later Hellenistic Alexandrian scholars, most certainly preserved by the Greco-Roman

The Greco-Roman civilization (; also Greco-Roman culture; spelled Graeco-Roman in the Commonwealth), as understood by modern scholars and writers, includes the geographical regions and countries that culturally—and so historically—were dir ...

historian Dio Chrysostom, and most likely influenced by Macedonian propaganda of the 4th century BC that emphasized the positive role the ancestors of Philip II () had in Greek affairs. Alexander I's successor Perdicas II () was not only saddled with internal revolt by the petty kings of Upper Macedonia, but also faced serious challenges to Macedonian territorial integrity

Territorial integrity is the principle under international law that gives the right to sovereign states to defend their borders and all territory in them of another state. It is enshrined in Article 2(4) of the UN Charter and has been recognized ...

by Sitalces

Sitalces (Sitalkes) (; Ancient Greek: Σιτάλκης, reigned 431–424 BC) was one of the great kings of the Thracian Odrysian state. The Suda called him Sitalcus (Σίταλκος).

He was the son of Teres I, and on the sudden death of ...

, a ruler in Thrace

Thrace (; el, Θράκη, Thráki; bg, Тракия, Trakiya; tr, Trakya) or Thrake is a geographical and historical region in Southeast Europe, now split among Bulgaria, Greece, and Turkey, which is bounded by the Balkan Mountains to ...

, and the Athenians, who fought four separate wars against Macedonia under Perdiccas II. During his reign, Athenian settlers began to encroach upon his coastal territories in Lower Macedonia to gather resources such as timber

Lumber is wood that has been processed into dimensional lumber, including Beam (structure), beams and plank (wood), planks or boards, a stage in the process of wood production. Lumber is mainly used for construction framing, as well as fini ...

and pitch in support of their navy, a practice that was actively encouraged by the Athenian leader Pericles

Pericles (; grc-gre, wikt:Περικλῆς, Περικλῆς; c. 495 – 429 BC) was a Greeks, Greek politician and general during the Fifth-century Athens, Golden Age of Athens. He was prominent and influential in Athens, Athenian politi ...

when he had colonists settle among the Bisaltae along the Strymon River. From 476 BC onward, the Athenians coerced some of the coastal towns of Macedonia along the Aegean Sea

The Aegean Sea ; tr, Ege Denizi (Greek: Αιγαίο Πέλαγος: "Egéo Pélagos", Turkish: "Ege Denizi" or "Adalar Denizi") is an elongated embayment of the Mediterranean Sea between Europe and Asia. It is located between the Balkans an ...

to join the Athenian-led Delian League

The Delian League, founded in 478 BC, was an association of Greek city-states, numbering between 150 and 330, under the leadership of Athens, whose purpose was to continue fighting the Persian Empire after the Greek victory in the Battle of Pl ...

as tributary states

A tributary state is a term for a pre-modern state in a particular type of subordinate relationship to a more powerful state which involved the sending of a regular token of submission, or tribute, to the superior power (the suzerain). This t ...

and in 437/436 BC founded the city of Amphipolis

Amphipolis ( ell, Αμφίπολη, translit=Amfipoli; grc, Ἀμφίπολις, translit=Amphipolis) is a municipality in the Serres regional unit, Macedonia, Greece. The seat of the municipality is Rodolivos. It was an important ancient Gr ...

at the mouth of the Strymon River for access to timber as well as gold and silver from the Pangaion Hills.

War broke out in 433 BC when Athens, perhaps seeking additional cavalry and resources in anticipation of the Peloponnesian War (431–404 BC), allied with a brother and cousin of Perdiccas II who were in open rebellion against him.. This led Perdiccas to seek alliances with Athens' rivals Sparta

Sparta (Doric Greek: Σπάρτα, ''Spártā''; Attic Greek: Σπάρτη, ''Spártē'') was a prominent city-state in Laconia, in ancient Greece. In antiquity, the city-state was known as Lacedaemon (, ), while the name Sparta referred ...

and Corinth

Corinth ( ; el, Κόρινθος, Kórinthos, ) is the successor to an ancient city, and is a former municipality in Corinthia, Peloponnese, which is located in south-central Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform, it has been part ...

, yet when his efforts were rejected he instead promoted the rebellion of nearby nominal Athenian allies in Chalcidice

Chalkidiki (; el, Χαλκιδική , also spelled Halkidiki, is a peninsula and regional units of Greece, regional unit of Greece, part of the region of Central Macedonia, in the Geographic regions of Greece, geographic region of Macedonia (Gr ...

, winning over the important city of Potidaea

__NOTOC__

Potidaea (; grc, Ποτίδαια, ''Potidaia'', also Ποτείδαια, ''Poteidaia'') was a colony founded by the Corinthians around 600 BC in the narrowest point of the peninsula of Pallene, the westernmost of three peninsulas at ...

. Athens responded by sending a naval invasion force that captured Therma

Therma or Thermē ( grc, Θέρμα, ) was a Greek city founded by Eretrians or Corinthians in late 7th century BC in ancient Mygdonia (which was later incorporated into Macedon), situated at the northeastern extremity of a great gulf of the Aege ...

and laid siege to Pydna

Pydna (in Greek: Πύδνα, older transliteration: Pýdna) was a Greek city in ancient Macedon, the most important in Pieria. Modern Pydna is a small town and a former municipality in the northeastern part of Pieria regional unit, Greece. Sinc ...

. However, they were unsuccessful in retaking Chalcidice and Potidaea due to stretching their forces thin by fighting the Macedonians and their allies on multiple fronts, and therefore sued for peace with Macedonia.. War resumed shortly after with the Athenian capture of Beroea and Macedonian aid given to the Potidaeans during an Athenian siege, yet by 431 BC, the Athenians and Macedonians concluded a peace treaty and alliance orchestrated by the Thracian ruler Sitalces of the Odrysian kingdom

The Odrysian Kingdom (; Ancient Greek: ) was a state grouping many Thracian tribes united by the Odrysae, which arose in the early 5th century BC and existed at least until the late 1st century BC. It consisted mainly of present-day Bulgaria an ...

. The Athenians had hoped to use Sitalces against the Macedonians, but due to Sitalces' desire to focus on acquiring more Thracian allies, he convinced Athens to make peace with Macedonia on the condition that he provide cavalry and peltast

A ''peltast'' ( grc-gre, πελταστής ) was a type of light infantryman, originating in Thrace and Paeonia, and named after the kind of shield he carried. Thucydides mentions the Thracian peltasts, while Xenophon in the Anabasis distin ...

s for the Athenian army in Chalcidice. Under this arrangement, Perdiccas II was given back Therma and no longer had to contend with his rebellious brother, Athens, and Sitacles all at once; in exchange he aided the Athenians in their subjugation of settlements in Chalcidice.

In 429 BC, Perdiccas II sent aid to the Spartan commander Cnemus in Acarnania

Acarnania ( el, Ἀκαρνανία) is a region of west-central Greece that lies along the Ionian Sea, west of Aetolia, with the Achelous River for a boundary, and north of the gulf of Calydon, which is the entrance to the Gulf of Corinth. Today ...

, but the Macedonian forces arrived too late to enter the Battle of Naupactus, which ended in an Athenian victory.. In that same year, Sitalces, according to Thucydides, invaded Macedonia at the behest of Athens to aid them in subduing Chalcidice and to punish Perdiccas II for violating the terms of their peace treaty

A peace treaty is an agreement between two or more hostile parties, usually countries or governments, which formally ends a state of war between the parties. It is different from an armistice, which is an agreement to stop hostilities; a surr ...

. However, given Sitalces' huge Thracian invading force (allegedly 150,000 soldiers) and a nephew of Perdiccas II that he intended to place on the Macedonian throne after toppling the latter's regime, Athens must have become wary of acting on their supposed alliance since they failed to provide him with promised naval support. Sitalces eventually retreated from Macedonia, perhaps due to logistical

Logistics is generally the detailed organization and implementation of a complex operation. In a general business sense, logistics manages the flow of goods between the point of origin and the point of consumption to meet the requirements of ...

concerns: a shortage of provisions and harsh winter conditions.

In 424 BC, Perdiccas began to play a prominent role in the Peloponnesian War by aiding the Spartan general Brasidas

Brasidas ( el, Βρασίδας, died 422 BC) was the most distinguished Spartan officer during the first decade of the Peloponnesian War who fought in battle of Amphipolis and Pylos. He died during the Second Battle of Amphipolis while winning ...

in convincing Athenian allies in Thrace to defect and ally with Sparta. After failing to convince Perdiccas II to make peace with Arrhabaeus of Lynkestis (a small region of Upper Macedonia), Brasidas agreed to aid the Macedonian fight against Arrhabaeus, although he expressed his concerns about leaving his Chalcidian allies to their own devices against Athens, as well as the fearsome Illyrian reinforcements arriving on the side of Arrhabaeus. The massive combined force commanded by Arrhabaeus apparently caused the army of Perdiccas II to flee in haste before the battle began, which enraged the Spartans under Brasidas, who proceeded to snatch pieces of the Macedonian baggage train left unprotected. Subsequently, Perdiccas II not only made peace with Athens but switched sides, blocking Peloponnesian reinforcements from reaching Brasidas via Thessaly. The treaty offered Athens economic concessions, but it also guaranteed internal stability in Macedonia since Arrhabaeus and other domestic detractors were convinced to lay down their arms and accept Perdiccas II as their suzerain

Suzerainty () is the rights and obligations of a person, state or other polity who controls the foreign policy and relations of a tributary state, while allowing the tributary state to have internal autonomy. While the subordinate party is ca ...

lord.

Perdiccas II was obliged to send aid to the Athenian general

Perdiccas II was obliged to send aid to the Athenian general Cleon

Cleon (; grc-gre, wikt:Κλέων, Κλέων, ; died 422 BC) was an Classical Athens, Athenian strategos, general during the Peloponnesian War. He was the first prominent representative of the commercial class in Athenian politics, although he w ...

, but he and Brasidas died in 422 BC, and the Peace of Nicias

The Peace of Nicias was a peace treaty signed between the Greek city-states of Athens and Sparta in March 421 BC that ended the first half of the Peloponnesian War.

In 425 BC, the Spartans had lost the battles of Pylos and Sphacteria, a sever ...

struck in the following year between Athens and Sparta nullified the Macedonian king's responsibilities as an erstwhile Athenian ally. After the Battle of Mantinea in 418 BC, Sparta and Argos formed a new alliance, which, alongside the threat of neighboring '' poleis'' in Chalcidice who were aligned with Sparta, induced Perdiccas II to abandon his Athenian alliance in favor of Sparta once again. This proved to be a strategic error, since Argos quickly switched sides as a pro-Athenian democracy

Democracy (From grc, δημοκρατία, dēmokratía, ''dēmos'' 'people' and ''kratos'' 'rule') is a form of government in which people, the people have the authority to deliberate and decide legislation ("direct democracy"), or to choo ...

, allowing Athens to punish Macedonia with a naval blockade

A blockade is the act of actively preventing a country or region from receiving or sending out food, supplies, weapons, or communications, and sometimes people, by military force.

A blockade differs from an embargo or sanction, which ar ...

in 417 BC along with the resumption of military activity in Chalcidice. Perdiccas II agreed to a peace settlement and alliance with Athens once more in 414 BC and, on his death a year later, was succeeded by his son Archelaus I

Archelaus I (; grc-gre, Ἀρχέλαος ) was king of the ancient Greek kingdom of Macedon from 413 to 399 BC. He was a capable and beneficent ruler, known for the sweeping changes he made in state administration, the military, and commerce. ...

().

Archelaus I maintained good relations with Athens throughout his reign, relying on Athens to provide naval support in his 410 BC siege of Pydna, and in exchange providing Athens with timber and naval equipment. With improvements to military organization and building of new infrastructure such as fortresses, Archelaus was able to strengthen Macedonia and project his power into Thessaly, where he aided his allies; yet he faced some internal revolt as well as problems fending off Illyria

In classical antiquity, Illyria (; grc, Ἰλλυρία, ''Illyría'' or , ''Illyrís''; la, Illyria, ''Illyricum'') was a region in the western part of the Balkan Peninsula inhabited by numerous tribes of people collectively known as the Illyr ...

n incursions led by Sirras. Although he retained Aigai as a ceremonial and religious center, Archelaus I moved the capital

Capital may refer to:

Common uses

* Capital city, a municipality of primary status

** List of national capital cities

* Capital letter, an upper-case letter Economics and social sciences

* Capital (economics), the durable produced goods used fo ...

of the kingdom north to Pella

Pella ( el, Πέλλα) is an ancient city located in Central Macedonia, Greece. It is best-known for serving as the capital city of the ancient Greek kingdom of Macedon, and was the birthplace of Alexander the Great.

On site of the ancient cit ...

, which was then positioned by a lake with a river connecting it to the Aegean Sea. He improved Macedonia's currency

A currency, "in circulation", from la, currens, -entis, literally meaning "running" or "traversing" is a standardization of money in any form, in use or circulation as a medium of exchange, for example banknotes and coins.

A more general ...

by minting coin

A coin is a small, flat (usually depending on the country or value), round piece of metal or plastic used primarily as a medium of exchange or legal tender. They are standardized in weight, and produced in large quantities at a mint in orde ...

s with a higher silver content as well as issuing separate copper coinage.. His royal court attracted the presence of well-known intellectuals such as the Athenian playwright

A playwright or dramatist is a person who writes plays.

Etymology

The word "play" is from Middle English pleye, from Old English plæġ, pleġa, plæġa ("play, exercise; sport, game; drama, applause"). The word "wright" is an archaic English ...

Euripides

Euripides (; grc, Εὐριπίδης, Eurīpídēs, ; ) was a tragedian of classical Athens. Along with Aeschylus and Sophocles, he is one of the three ancient Greek tragedians for whom any plays have survived in full. Some ancient scholars ...

.

Historical sources offer wildly different and confused accounts as to who assassinated Archelaus I, although it likely involved a

Historical sources offer wildly different and confused accounts as to who assassinated Archelaus I, although it likely involved a homosexual

Homosexuality is romantic attraction, sexual attraction, or sexual behavior between members of the same sex or gender. As a sexual orientation, homosexuality is "an enduring pattern of emotional, romantic, and/or sexual attractions" to pe ...

love affair with royal pages at his court. What ensued was a power struggle lasting from 399 to 393 BC of four different monarchs claiming the throne: Orestes, son of Archelaus I; Aeropus II, uncle, regent

A regent (from Latin : ruling, governing) is a person appointed to govern a state ''pro tempore'' (Latin: 'for the time being') because the monarch is a minor, absent, incapacitated or unable to discharge the powers and duties of the monarchy, ...

, and murderer of Orestes; Pausanias, son of Aeropus II; and Amyntas II

Amyntas II ( grc, Ἀμύντας) or Amyntas the Little, was the king of the Ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia for a short time, ''circa'' 393 BC. Thucydides describes him as a son of Philip, the brother of king Perdiccas II. He first succe ...

, who was married to the youngest daughter of Archelaus I.; . Very little is known about this period, although each of these monarchs aside from Orestes managed to mint debased currency imitating that of Archelaus I.. Finally, Amyntas III (), son of Arrhidaeus and grandson of Amyntas I, succeeded to the throne by killing Pausanias.

The Greek historian Diodorus Siculus provided a seemingly conflicting account about Illyrian invasions occurring in 393 BC and 383 BC, which may have been representative of a single invasion led by Bardylis of the Dardani

The Dardani (; grc, Δαρδάνιοι, Δάρδανοι; la, Dardani) or Dardanians were a Paleo-Balkan people, who lived in a region that was named Dardania after their settlement there. They were among the oldest Balkan peoples, and their ...

. In this event, Amyntas III is said to have fled his own kingdom and returned with the support of Thessalian allies, while a possible pretender

A pretender is someone who claims to be the rightful ruler of a country although not recognized as such by the current government. The term is often used to suggest that a claim is not legitimate.Curley Jr., Walter J. P. ''Monarchs-in-Waiting'' ...

to the throne named Argaeus had ruled temporarily in Amyntas III's absence. When the powerful Chalcidian city of Olynthos

Olynthus ( grc, Ὄλυνθος ''Olynthos'', named for the ὄλυνθος ''olunthos'', "the fruit of the wild fig tree") was an ancient city of Chalcidice, built mostly on two flat-topped hills 30–40m in height, in a fertile plain at the he ...

was allegedly poised to overthrow Amyntas III and conquer the Macedonian kingdom, Teleutias, brother of the Spartan king Agesilaus II

Agesilaus II (; grc-gre, Ἀγησίλαος ; c. 442 – 358 BC) was king of Sparta from c. 399 to 358 BC. Generally considered the most important king in the history of Sparta, Agesilaus was the main actor during the period of Spartan hegemo ...

, sailed to Macedonia with a large Spartan force to provide critical aid to Amyntas III. The result of this campaign in 379 BC was the surrender of Olynthos and the abolition of the Chalcidian League.

Amyntas III had children with two wives, but it was his eldest son by his marriage with Eurydice I who succeeded him as Alexander II (). When Alexander II invaded Thessaly and occupied Larissa

Larissa (; el, Λάρισα, , ) is the capital and largest city of the Thessaly region in Greece. It is the fifth-most populous city in Greece with a population of 144,651 according to the 2011 census. It is also capital of the Larissa regiona ...

and Crannon

Cranon ( grc, Κρανών) or Crannon (Κραννών) was a town and polis (city-state) of Pelasgiotis, in ancient Thessaly, situated southwest of Larissa, and at the distance of 100 stadia from Gyrton, according to Strabo. Spelling differs ...

as a challenge to the suzerainty of the ''tagus

The Tagus ( ; es, Tajo ; pt, Tejo ; see below) is the longest river in the Iberian Peninsula. The river rises in the Montes Universales near Teruel, in mid-eastern Spain, flows , generally west with two main south-westward sections, to ...

'' (supreme Thessalian military leader) Alexander of Pherae

Alexander ( grc, Ἀλέξανδρος) was Tyrant or Despot of Pherae in Thessaly, ruling from 369 to c. 356 BC. Following the assassination of Jason, the tyrant of Pherae and Tagus of Thessaly, in 370 BC, his brother Polydorus ruled for a year ...

, the Thessalians appealed to Pelopidas

Pelopidas (; grc-gre, Πελοπίδας; died 364 BC) was an important Theban statesman and general in Greece, instrumental in establishing the mid-fourth century Theban hegemony.

Biography

Athlete and warrior

Pelopidas was a member of a ...

of Thebes for help to expel both of these rival overlord

An overlord in the English feudal system was a lord of a manor who had subinfeudated a particular manor, estate or fee, to a tenant. The tenant thenceforth owed to the overlord one of a variety of services, usually military service or s ...

s. After Pelopidas captured Larissa, Alexander II made peace and allied with Thebes, handing over noble hostage

A hostage is a person seized by an abductor in order to compel another party, one which places a high value on the liberty, well-being and safety of the person seized, such as a relative, employer, law enforcement or government to act, or ref ...

s including his brother and future king, Philip II. Afterwards, Ptolemy of Aloros assassinated his brother-in-law Alexander II and acted as regent for the latter's younger brother Perdiccas III (). Ptolemy's intervention in Thessaly in 367 BC provoked another Theban invasion by Pelopidas, who was undermined when Ptolemy bribed his mercenaries not to fight, thus leading to a newly proposed alliance between Macedonia and Thebes, but only on the condition that more hostages, including one of his Ptolemy's sons, were to be handed over to Thebes.; . By 365 BC, Perdiccas III had reached the age of majority

The age of majority is the threshold of legal adulthood as recognized or declared in law. It is the moment when minors cease to be considered such and assume legal control over their persons, actions, and decisions, thus terminating the contro ...

and took the opportunity to kill his regent Ptolemy, initiating a sole reign marked by internal stability, financial recovery, fostering of Greek intellectualism at his court, and the return of his brother Philip from Thebes. However, Perdiccas III also dealt with an Athenian invasion by Timotheus, son of Conon

Conon ( el, Κόνων) (before 443 BC – c. 389 BC) was an Athenian general at the end of the Peloponnesian War, who led the Athenian naval forces when they were defeated by a Peloponnesian fleet in the crucial Battle of Aegospotami; later he ...

, that led to the loss of Methone and Pydna

Pydna (in Greek: Πύδνα, older transliteration: Pýdna) was a Greek city in ancient Macedon, the most important in Pieria. Modern Pydna is a small town and a former municipality in the northeastern part of Pieria regional unit, Greece. Sinc ...

, while an invasion of Illyrians led by Bardylis succeeded in killing Perdiccas III and 4,000 Macedonian troops in battle.

Rise of Macedon

Philip II of Macedon

Philip II of Macedon ( grc-gre, Φίλιππος ; 382 – 21 October 336 BC) was the king ('' basileus'') of the ancient kingdom of Macedonia from 359 BC until his death in 336 BC. He was a member of the Argead dynasty, founders of the a ...

(), who spent much of his adolescence

Adolescence () is a transitional stage of physical and psychological development that generally occurs during the period from puberty to adulthood (typically corresponding to the age of majority). Adolescence is usually associated with t ...

as a political hostage in Thebes, was twenty-four years old when he acceded to the throne and immediately faced crises that threatened to topple his leadership. However, with the use of deft diplomacy, he was able to convince the Thracians under Berisades to cease their support of Pausanias, a pretender to the throne, and the Athenians to halt their backing of another pretender named Arg(a)eus (perhaps the same who had caused trouble for Amyntas III). He achieved these by bribing the Thracians and their Paeonian

In antiquity, Paeonia or Paionia ( grc, Παιονία, Paionía) was the land and kingdom of the Paeonians or Paionians ( grc, Παίονες, Paíones).

The exact original boundaries of Paeonia, like the early history of its inhabitants, a ...

allies and removing a garrison of Macedonian troops from Amphipolis, establishing a treaty with Athens that relinquished his claims to that city. He was also able to make peace with the Illyrians who had threatened his borders.

Macedonian phalanx

The Macedonian phalanx ( gr, Μακεδονική φάλαγξ) was an infantry formation developed by Philip II from the classical Greek phalanx, of which the main innovation was the use of the sarissa, a 6 meter pike. It was famously commande ...

armed with long pikes (i.e. the ''sarissa

The sarisa or sarissa ( el, σάρισα) was a long spear or pike about in length. It was introduced by Philip II of Macedon and was used in his Macedonian phalanxes as a replacement for the earlier dory, which was considerably shorter. The ...