Hebrew Language on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

In May 2023, Scott Stripling published the finding of what he claims to be the oldest known Hebrew inscription, a curse tablet found at Mount Ebal, dated from around 3200 years ago. The presence of the Hebrew name of god, Yahweh, as three letters, ''Yod-Heh-Vav'' (YHV), according to the author and his team meant that the tablet is Hebrew and not Canaanite. However, practically all professional archeologists and epigraphers apart from Stripling's team claim that there is no text on this object.

In July 2008, Israeli archaeologist Yossi Garfinkel discovered a ceramic shard at Khirbet Qeiyafa that he claimed may be the earliest Hebrew writing yet discovered, dating from around 3,000 years ago. Hebrew University archaeologist Amihai Mazar said that the inscription was "proto-Canaanite" but cautioned that differentiation between the scripts, and between the languages themselves in that period, remains unclear", and suggested that calling the text Hebrew might be going too far.

The Gezer calendar also dates back to the 10th century BCE at the beginning of the Monarchic period, the traditional time of the reign of David and Solomon. Classified as Archaic Biblical Hebrew, the calendar presents a list of seasons and related agricultural activities. The Gezer calendar (named after the city in whose proximity it was found) is written in an old Semitic script, akin to the Phoenician one that, through the Greeks and Etruscans, later became the

In May 2023, Scott Stripling published the finding of what he claims to be the oldest known Hebrew inscription, a curse tablet found at Mount Ebal, dated from around 3200 years ago. The presence of the Hebrew name of god, Yahweh, as three letters, ''Yod-Heh-Vav'' (YHV), according to the author and his team meant that the tablet is Hebrew and not Canaanite. However, practically all professional archeologists and epigraphers apart from Stripling's team claim that there is no text on this object.

In July 2008, Israeli archaeologist Yossi Garfinkel discovered a ceramic shard at Khirbet Qeiyafa that he claimed may be the earliest Hebrew writing yet discovered, dating from around 3,000 years ago. Hebrew University archaeologist Amihai Mazar said that the inscription was "proto-Canaanite" but cautioned that differentiation between the scripts, and between the languages themselves in that period, remains unclear", and suggested that calling the text Hebrew might be going too far.

The Gezer calendar also dates back to the 10th century BCE at the beginning of the Monarchic period, the traditional time of the reign of David and Solomon. Classified as Archaic Biblical Hebrew, the calendar presents a list of seasons and related agricultural activities. The Gezer calendar (named after the city in whose proximity it was found) is written in an old Semitic script, akin to the Phoenician one that, through the Greeks and Etruscans, later became the

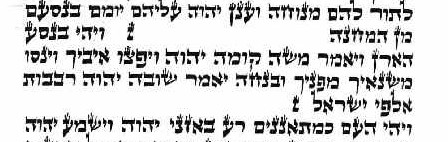

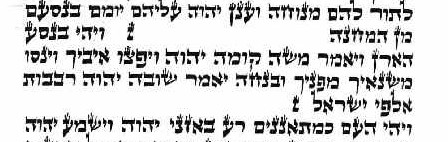

Standard Biblical Hebrew, also called Biblical Hebrew, Early Biblical Hebrew, Classical Biblical Hebrew or Classical Hebrew (in the narrowest sense), around the 8th to 6th centuries BCE, corresponding to the late Monarchic period and the Babylonian exile. It is represented by the bulk of the Hebrew Bible that attains much of its present form around this time.

* Late Biblical Hebrew, from the 5th to the 3rd centuries BCE, corresponding to the Persian period and represented by certain texts in the Hebrew Bible, notably the books of Ezra and Nehemiah. Basically similar to Classical Biblical Hebrew, apart from a few foreign words adopted for mainly governmental terms, and some syntactical innovations such as the use of the particle ''she-'' (alternative of "asher", meaning "that, which, who"). It adopted the Imperial Aramaic script (from which the modern Hebrew script descends).

* Israelian Hebrew is a proposed northern dialect of biblical Hebrew, believed to have existed in all eras of the language, in some cases competing with late biblical Hebrew as an explanation for non-standard linguistic features of biblical texts.

Standard Biblical Hebrew, also called Biblical Hebrew, Early Biblical Hebrew, Classical Biblical Hebrew or Classical Hebrew (in the narrowest sense), around the 8th to 6th centuries BCE, corresponding to the late Monarchic period and the Babylonian exile. It is represented by the bulk of the Hebrew Bible that attains much of its present form around this time.

* Late Biblical Hebrew, from the 5th to the 3rd centuries BCE, corresponding to the Persian period and represented by certain texts in the Hebrew Bible, notably the books of Ezra and Nehemiah. Basically similar to Classical Biblical Hebrew, apart from a few foreign words adopted for mainly governmental terms, and some syntactical innovations such as the use of the particle ''she-'' (alternative of "asher", meaning "that, which, who"). It adopted the Imperial Aramaic script (from which the modern Hebrew script descends).

* Israelian Hebrew is a proposed northern dialect of biblical Hebrew, believed to have existed in all eras of the language, in some cases competing with late biblical Hebrew as an explanation for non-standard linguistic features of biblical texts.

In the early 6th century BCE, the Neo-Babylonian Empire conquered the ancient Kingdom of Judah, destroying much of

In the early 6th century BCE, the Neo-Babylonian Empire conquered the ancient Kingdom of Judah, destroying much of

After the Talmud, various regional literary dialects of Medieval Hebrew evolved. The most important is Tiberian Hebrew or Masoretic Hebrew, a local dialect of Tiberias in Galilee that became the standard for vocalizing the Hebrew Bible and thus still influences all other regional dialects of Hebrew. This Tiberian Hebrew from the 7th to 10th century CE is sometimes called "Biblical Hebrew" because it is used to pronounce the Hebrew Bible; however, properly it should be distinguished from the historical Biblical Hebrew of the 6th century BCE, whose original pronunciation must be reconstructed. Tiberian Hebrew incorporates the scholarship of the Masoretes (from ''masoret'' meaning "tradition"), who added vowel points and grammar points to the Hebrew letters to preserve much earlier features of Hebrew, for use in chanting the Hebrew Bible. The Masoretes inherited a biblical text whose letters were considered too sacred to be altered, so their markings were in the form of pointing in and around the letters. The Syriac alphabet, precursor to the Arabic alphabet, also developed vowel pointing systems around this time. The Aleppo Codex, a Hebrew Bible with the Masoretic pointing, was written in the 10th century, likely in Tiberias, and survives into the present day. It is perhaps the most important Hebrew manuscript in existence.

During the Golden age of Jewish culture in Spain, important work was done by grammarians in explaining the grammar and vocabulary of Biblical Hebrew; much of this was based on the work of the grammarians of Classical Arabic. Important Hebrew grammarians were , Jonah ibn Janah, Abraham ibn Ezra and later (in Provence), . A great deal of poetry was written, by poets such as , Solomon ibn Gabirol, Judah ha-Levi, Moses ibn Ezra and Abraham ibn Ezra, in a "purified" Hebrew based on the work of these grammarians, and in Arabic quantitative or strophic meters. This literary Hebrew was later used by Italian Jewish poets.

The need to express scientific and philosophical concepts from Classical Greek and Medieval Arabic motivated Medieval Hebrew to borrow terminology and grammar from these other languages, or to coin equivalent terms from existing Hebrew roots, giving rise to a distinct style of philosophical Hebrew. This is used in the translations made by the family. (Original Jewish philosophical works were usually written in Arabic.) Another important influence was

After the Talmud, various regional literary dialects of Medieval Hebrew evolved. The most important is Tiberian Hebrew or Masoretic Hebrew, a local dialect of Tiberias in Galilee that became the standard for vocalizing the Hebrew Bible and thus still influences all other regional dialects of Hebrew. This Tiberian Hebrew from the 7th to 10th century CE is sometimes called "Biblical Hebrew" because it is used to pronounce the Hebrew Bible; however, properly it should be distinguished from the historical Biblical Hebrew of the 6th century BCE, whose original pronunciation must be reconstructed. Tiberian Hebrew incorporates the scholarship of the Masoretes (from ''masoret'' meaning "tradition"), who added vowel points and grammar points to the Hebrew letters to preserve much earlier features of Hebrew, for use in chanting the Hebrew Bible. The Masoretes inherited a biblical text whose letters were considered too sacred to be altered, so their markings were in the form of pointing in and around the letters. The Syriac alphabet, precursor to the Arabic alphabet, also developed vowel pointing systems around this time. The Aleppo Codex, a Hebrew Bible with the Masoretic pointing, was written in the 10th century, likely in Tiberias, and survives into the present day. It is perhaps the most important Hebrew manuscript in existence.

During the Golden age of Jewish culture in Spain, important work was done by grammarians in explaining the grammar and vocabulary of Biblical Hebrew; much of this was based on the work of the grammarians of Classical Arabic. Important Hebrew grammarians were , Jonah ibn Janah, Abraham ibn Ezra and later (in Provence), . A great deal of poetry was written, by poets such as , Solomon ibn Gabirol, Judah ha-Levi, Moses ibn Ezra and Abraham ibn Ezra, in a "purified" Hebrew based on the work of these grammarians, and in Arabic quantitative or strophic meters. This literary Hebrew was later used by Italian Jewish poets.

The need to express scientific and philosophical concepts from Classical Greek and Medieval Arabic motivated Medieval Hebrew to borrow terminology and grammar from these other languages, or to coin equivalent terms from existing Hebrew roots, giving rise to a distinct style of philosophical Hebrew. This is used in the translations made by the family. (Original Jewish philosophical works were usually written in Arabic.) Another important influence was

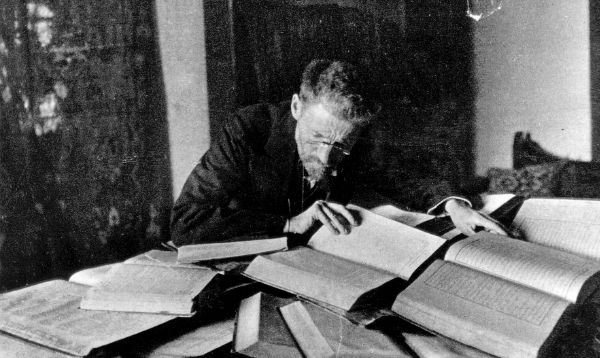

Hebrew has been revived several times as a literary language, most significantly by the Haskalah (Enlightenment) movement of early and mid-19th-century Germany. In the early 19th century, a form of spoken Hebrew had emerged in the markets of Jerusalem between Jews of different linguistic backgrounds to communicate for commercial purposes. This Hebrew dialect was to a certain extent a pidgin. Near the end of that century the Jewish activist Eliezer Ben-Yehuda, owing to the ideology of the national revival (, , later Zionism), began reviving Hebrew as a modern spoken language. Eventually, as a result of the local movement he created, but more significantly as a result of the new groups of immigrants known under the name of the Second Aliyah, it replaced a score of languages spoken by Jews at that time. Those languages were Jewish dialects of local languages, including Judaeo-Spanish (also called "Judezmo" and "Ladino"),

Hebrew has been revived several times as a literary language, most significantly by the Haskalah (Enlightenment) movement of early and mid-19th-century Germany. In the early 19th century, a form of spoken Hebrew had emerged in the markets of Jerusalem between Jews of different linguistic backgrounds to communicate for commercial purposes. This Hebrew dialect was to a certain extent a pidgin. Near the end of that century the Jewish activist Eliezer Ben-Yehuda, owing to the ideology of the national revival (, , later Zionism), began reviving Hebrew as a modern spoken language. Eventually, as a result of the local movement he created, but more significantly as a result of the new groups of immigrants known under the name of the Second Aliyah, it replaced a score of languages spoken by Jews at that time. Those languages were Jewish dialects of local languages, including Judaeo-Spanish (also called "Judezmo" and "Ladino"),

Standard Hebrew, as developed by Eliezer Ben-Yehuda, was based on Mishnaic spelling and Sephardi Hebrew pronunciation. However, the earliest speakers of Modern Hebrew had Yiddish as their native language and often introduced calques from Yiddish and phono-semantic matchings of international words.

Despite using Sephardic Hebrew pronunciation as its primary basis, modern Israeli Hebrew has adapted to Ashkenazi Hebrew

Standard Hebrew, as developed by Eliezer Ben-Yehuda, was based on Mishnaic spelling and Sephardi Hebrew pronunciation. However, the earliest speakers of Modern Hebrew had Yiddish as their native language and often introduced calques from Yiddish and phono-semantic matchings of international words.

Despite using Sephardic Hebrew pronunciation as its primary basis, modern Israeli Hebrew has adapted to Ashkenazi Hebrew

Modern Hebrew is the primary official language of the State of Israel. , there are about 9 million Hebrew speakers worldwide, of whom 7 million speak it fluently.

Currently, 90% of Israeli Jews are proficient in Hebrew, and 70% are highly proficient. Some 60% of Israeli Arabs are also proficient in Hebrew, and 30% report having a higher proficiency in Hebrew than in Arabic. In total, about 53% of the Israeli population speaks Hebrew as a native language, while most of the rest speak it fluently. In 2013 Hebrew was the native language of 49% of Israelis over the age of 20, with Russian,

Modern Hebrew is the primary official language of the State of Israel. , there are about 9 million Hebrew speakers worldwide, of whom 7 million speak it fluently.

Currently, 90% of Israeli Jews are proficient in Hebrew, and 70% are highly proficient. Some 60% of Israeli Arabs are also proficient in Hebrew, and 30% report having a higher proficiency in Hebrew than in Arabic. In total, about 53% of the Israeli population speaks Hebrew as a native language, while most of the rest speak it fluently. In 2013 Hebrew was the native language of 49% of Israelis over the age of 20, with Russian,

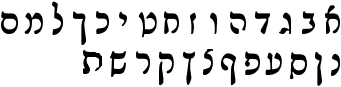

Users of the language write Modern Hebrew from right to left using the Hebrew alphabet – an "impure" abjad, or consonant-only script, of 22 letters. The ancient Paleo-Hebrew alphabet resembles those used for Canaanite and Phoenician. Modern scripts derive from the "square" letter form, known as ''Ashurit'' (Assyrian), which developed from the Aramaic script. A cursive Hebrew script is used in handwriting: the letters tend to appear more circular in form when written in cursive, and sometimes vary markedly from their printed equivalents. The medieval version of the cursive script forms the basis of another style, known as Rashi script. When necessary, vowels are indicated by diacritic marks above or below the letter representing the syllabic onset, or by use of '' matres lectionis'', which are consonantal letters used as vowels. Further diacritics may serve to indicate variations in the pronunciation of the consonants (e.g. ''bet''/''vet'', ''shin''/''sin''); and, in some contexts, to indicate the punctuation, accentuation and musical rendition of Biblical texts (see Hebrew cantillation).

Users of the language write Modern Hebrew from right to left using the Hebrew alphabet – an "impure" abjad, or consonant-only script, of 22 letters. The ancient Paleo-Hebrew alphabet resembles those used for Canaanite and Phoenician. Modern scripts derive from the "square" letter form, known as ''Ashurit'' (Assyrian), which developed from the Aramaic script. A cursive Hebrew script is used in handwriting: the letters tend to appear more circular in form when written in cursive, and sometimes vary markedly from their printed equivalents. The medieval version of the cursive script forms the basis of another style, known as Rashi script. When necessary, vowels are indicated by diacritic marks above or below the letter representing the syllabic onset, or by use of '' matres lectionis'', which are consonantal letters used as vowels. Further diacritics may serve to indicate variations in the pronunciation of the consonants (e.g. ''bet''/''vet'', ''shin''/''sin''); and, in some contexts, to indicate the punctuation, accentuation and musical rendition of Biblical texts (see Hebrew cantillation).

Official website

of the Academy of the Hebrew Language

Official website

of the Historical Dictionary Project of the Hebrew Language

Hebrew language

at the National Library of Israel *

A Guide to Hebrew

at BBC Online

Official website

of Morfix, a Hebrew-English dictionary

Hebrew language

at the

Hebrew Basic Course

by the Foreign Service Institute {{DEFAULTSORT:Hebrew Language Canaanite languages Fusional languages Jewish languages Languages attested from the 10th century BC Languages of Israel Verb–subject–object languages Hebrews

Hebrew (; ''ʿÎbrit'') is a Northwest Semitic language within the Afroasiatic language family. A regional dialect of the Canaanite languages, it was natively spoken by the Israelites and remained in regular use as a first language until after 200 CE and as the liturgical language of Judaism (since the Second Temple period) and Samaritanism. The language was revived as a spoken language in the 19th century, and is the only successful large-scale example of linguistic revival. It is the only Canaanite language, as well as one of only two Northwest Semitic languages, with the other being Aramaic, still spoken today.

The earliest examples of written Paleo-Hebrew date back to the 10th century BCE. Nearly all of the Hebrew Bible is written in

, via Latin from the Ancient Greek () and Aramaic ''Biblical Hebrew

Biblical Hebrew ( or ), also called Classical Hebrew, is an archaic form of the Hebrew language, a language in the Canaanite languages, Canaanitic branch of the Semitic languages spoken by the Israelites in the area known as the Land of Isra ...

, with much of its present form in the dialect that scholars believe flourished around the 6th century BCE, during the time of the Babylonian captivity. For this reason, Hebrew has been referred to by Jews as '' Lashon Hakodesh'' (, ) since ancient times. The language was not referred to by the name ''Hebrew'' in the Bible, but as ''Yehudit'' () or ''Səpaṯ Kəna'an'' (). Mishnah Gittin 9:8 refers to the language as ''Ivrit'', meaning Hebrew; however, Mishnah Megillah refers to the language as ''Ashurit'', meaning Assyrian, which is derived from the name of the alphabet used, in contrast to ''Ivrit'', meaning the Paleo-Hebrew alphabet.

Hebrew ceased to be a regular spoken language sometime between 200 and 400 CE, as it declined in the aftermath of the unsuccessful Bar Kokhba revolt, which was carried out against the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ruled the Mediterranean and much of Europe, Western Asia and North Africa. The Roman people, Romans conquered most of this during the Roman Republic, Republic, and it was ruled by emperors following Octavian's assumption of ...

by the Jews of Judaea. Aramaic and, to a lesser extent, Greek were already in use as international languages, especially among societal elites and immigrants. Hebrew survived into the medieval period as the language of Jewish liturgy, rabbinic literature, intra-Jewish commerce, and Jewish poetic literature. The first dated book printed in Hebrew was published by Abraham Garton in Reggio ( Calabria, Italy) in 1475. With the rise of Zionism in the 19th century, the Hebrew language experienced a full-scale revival as a spoken and literary language. The creation of a modern version of the ancient language was led by Eliezer Ben-Yehuda. Modern Hebrew (''Ivrit'') became the main language of the Yishuv in Palestine, and subsequently the official language of the State of Israel.

Estimates of worldwide usage include five million speakers in 1998, and over nine million people in 2013. After Israel, the United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

has the largest Hebrew-speaking population, with approximately 220,000 fluent speakers (see Israeli Americans and Jewish Americans). Pre-revival forms of Hebrew are used for prayer or study in Jewish and Samaritan communities around the world today; the latter group utilizes the Samaritan dialect as their liturgical tongue. As a non-first language

A first language (L1), native language, native tongue, or mother tongue is the first language a person has been exposed to from birth or within the critical period hypothesis, critical period. In some countries, the term ''native language'' ...

, it is studied mostly by non-Israeli Jews and students in Israel, by archaeologists and linguists specializing in the Middle East

The Middle East (term originally coined in English language) is a geopolitical region encompassing the Arabian Peninsula, the Levant, Turkey, Egypt, Iran, and Iraq.

The term came into widespread usage by the United Kingdom and western Eur ...

and its civilizations, and by theologians in Christian seminaries.

Etymology

The modern English word "Hebrew" is derived fromOld French

Old French (, , ; ) was the language spoken in most of the northern half of France approximately between the late 8th -4; we might wonder whether there's a point at which it's appropriate to talk of the beginnings of French, that is, when it wa ...

, via Latin">-4; we might wonder whether there's a point at which it's appropriate to talk of the beginnings of French, that is, when it wa ...Biblical Hebrew

Biblical Hebrew ( or ), also called Classical Hebrew, is an archaic form of the Hebrew language, a language in the Canaanite languages, Canaanitic branch of the Semitic languages spoken by the Israelites in the area known as the Land of Isra ...

(), one of several names for the Israelite (Jews">Jewish

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of History of ancient Israel and Judah, ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, rel ...

and Samaritan) people, or the Hebrews">Samaritans">Samaritan) people, or the Hebrews. It is traditionally understood to be an adjective based on the name of Abraham's ancestor, Eber, mentioned in . The name is believed to be based on the Semitic root ''ʕ-b-r'' (), meaning "beyond", "other side", "across"; interpretations of the term "Hebrew" generally render its meaning as roughly "from the other side f the river/desert—i.e., an exonym for the inhabitants of the land of Israel and Judah, perhaps from the perspective of Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia is a historical region of West Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the Fertile Crescent. Today, Mesopotamia is known as present-day Iraq and forms the eastern geographic boundary of ...

, Phoenicia or Transjordan (with the river referred to being perhaps the Euphrates

The Euphrates ( ; see #Etymology, below) is the longest and one of the most historically important rivers of West Asia. Tigris–Euphrates river system, Together with the Tigris, it is one of the two defining rivers of Mesopotamia (). Originati ...

, Jordan

Jordan, officially the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan, is a country in the Southern Levant region of West Asia. Jordan is bordered by Syria to the north, Iraq to the east, Saudi Arabia to the south, and Israel and the occupied Palestinian ter ...

or Litani; or maybe the northern Arabian Desert between Babylonia and Canaan). Compare the word '' Habiru'' or cognate Assyrian ''ebru'', of identical meaning.

One of the earliest references to the language's name as "''Ivrit''" is found in the prologue to the Book of Sirach, from the 2nd century BCE. The Hebrew Bible does not use the term "Hebrew" in reference to the language of the Hebrew people; its later historiography, in the Book of Kings, refers to it as ''Yehudit'' " Judahite (language)".

History

Hebrew belongs to the Canaanite group of languages. Canaanite languages are a branch of the Northwest Semitic family of languages. Hebrew was the spoken language in the Iron Age kingdoms ofIsrael

Israel, officially the State of Israel, is a country in West Asia. It Borders of Israel, shares borders with Lebanon to the north, Syria to the north-east, Jordan to the east, Egypt to the south-west, and the Mediterranean Sea to the west. Isr ...

and Judah during the period from about 1200 to 586 BCE. Epigraphic evidence from this period confirms the widely accepted view that the earlier layers of biblical literature reflect the language used in these kingdoms. Furthermore, the content of Hebrew inscriptions suggests that the written texts closely mirror the spoken language of that time.

Scholars debate the degree to which Hebrew was a spoken vernacular in ancient times following the Babylonian exile when the predominant international language in the region was Old Aramaic.

Hebrew was extinct as a colloquial language by late antiquity, but it continued to be used as a literary language, especially in Spain, as the language of commerce between Jews of different native languages, and as the liturgical language of Judaism, evolving various dialects of literary Medieval Hebrew, until its revival as a spoken language in the late 19th century.

Oldest Hebrew inscriptions

In May 2023, Scott Stripling published the finding of what he claims to be the oldest known Hebrew inscription, a curse tablet found at Mount Ebal, dated from around 3200 years ago. The presence of the Hebrew name of god, Yahweh, as three letters, ''Yod-Heh-Vav'' (YHV), according to the author and his team meant that the tablet is Hebrew and not Canaanite. However, practically all professional archeologists and epigraphers apart from Stripling's team claim that there is no text on this object.

In July 2008, Israeli archaeologist Yossi Garfinkel discovered a ceramic shard at Khirbet Qeiyafa that he claimed may be the earliest Hebrew writing yet discovered, dating from around 3,000 years ago. Hebrew University archaeologist Amihai Mazar said that the inscription was "proto-Canaanite" but cautioned that differentiation between the scripts, and between the languages themselves in that period, remains unclear", and suggested that calling the text Hebrew might be going too far.

The Gezer calendar also dates back to the 10th century BCE at the beginning of the Monarchic period, the traditional time of the reign of David and Solomon. Classified as Archaic Biblical Hebrew, the calendar presents a list of seasons and related agricultural activities. The Gezer calendar (named after the city in whose proximity it was found) is written in an old Semitic script, akin to the Phoenician one that, through the Greeks and Etruscans, later became the

In May 2023, Scott Stripling published the finding of what he claims to be the oldest known Hebrew inscription, a curse tablet found at Mount Ebal, dated from around 3200 years ago. The presence of the Hebrew name of god, Yahweh, as three letters, ''Yod-Heh-Vav'' (YHV), according to the author and his team meant that the tablet is Hebrew and not Canaanite. However, practically all professional archeologists and epigraphers apart from Stripling's team claim that there is no text on this object.

In July 2008, Israeli archaeologist Yossi Garfinkel discovered a ceramic shard at Khirbet Qeiyafa that he claimed may be the earliest Hebrew writing yet discovered, dating from around 3,000 years ago. Hebrew University archaeologist Amihai Mazar said that the inscription was "proto-Canaanite" but cautioned that differentiation between the scripts, and between the languages themselves in that period, remains unclear", and suggested that calling the text Hebrew might be going too far.

The Gezer calendar also dates back to the 10th century BCE at the beginning of the Monarchic period, the traditional time of the reign of David and Solomon. Classified as Archaic Biblical Hebrew, the calendar presents a list of seasons and related agricultural activities. The Gezer calendar (named after the city in whose proximity it was found) is written in an old Semitic script, akin to the Phoenician one that, through the Greeks and Etruscans, later became the Latin alphabet

The Latin alphabet, also known as the Roman alphabet, is the collection of letters originally used by the Ancient Rome, ancient Romans to write the Latin language. Largely unaltered except several letters splitting—i.e. from , and from � ...

of ancient Rome

In modern historiography, ancient Rome is the Roman people, Roman civilisation from the founding of Rome, founding of the Italian city of Rome in the 8th century BC to the Fall of the Western Roman Empire, collapse of the Western Roman Em ...

. The Gezer calendar is written without any vowel

A vowel is a speech sound pronounced without any stricture in the vocal tract, forming the nucleus of a syllable. Vowels are one of the two principal classes of speech sounds, the other being the consonant. Vowels vary in quality, in loudness a ...

s, and it does not use consonants to imply vowels even in the places in which later Hebrew spelling requires them.

Numerous older tablets have been found in the region with similar scripts written in other Semitic languages, for example, Proto-Sinaitic. It is believed that the original shapes of the script go back to Egyptian hieroglyphs

Ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs ( ) were the formal writing system used in Ancient Egypt for writing the Egyptian language. Hieroglyphs combined Ideogram, ideographic, logographic, syllabic and alphabetic elements, with more than 1,000 distinct char ...

, though the phonetic values are instead inspired by the acrophonic principle. The common ancestor of Hebrew and Phoenician is called Canaanite, and was the first to use a Semitic alphabet distinct from that of Egyptian. One ancient document is the famous Moabite Stone, written in the Moabite dialect; the Siloam inscription, found near Jerusalem

Jerusalem is a city in the Southern Levant, on a plateau in the Judaean Mountains between the Mediterranean Sea, Mediterranean and the Dead Sea. It is one of the List of oldest continuously inhabited cities, oldest cities in the world, and ...

, is an early example of Hebrew. Less ancient samples of Archaic Hebrew include the ostraca found near Lachish, which describe events preceding the final capture of Jerusalem by Nebuchadnezzar and the Babylonian captivity of 586 BCE.

Classical Hebrew

Biblical Hebrew

In its widest sense, Biblical Hebrew refers to the spoken language of ancient Israel flourishing between and . It comprises several evolving and overlapping dialects. The phases of Classical Hebrew are often named after important literary works associated with them. * Archaic Biblical Hebrew, also called Old Hebrew or Paleo-Hebrew, from the 10th to the 6th century BCE, corresponding to the Monarchic Period until the Babylonian exile and represented by certain texts in the Hebrew Bible ( Tanakh), notably the Song of Moses (Exodus 15) and the Song of Deborah (Judges 5). It was written in the Paleo-Hebrew alphabet. A script descended from this, the Samaritan alphabet, is still used by the Samaritans. * Standard Biblical Hebrew, also called Biblical Hebrew, Early Biblical Hebrew, Classical Biblical Hebrew or Classical Hebrew (in the narrowest sense), around the 8th to 6th centuries BCE, corresponding to the late Monarchic period and the Babylonian exile. It is represented by the bulk of the Hebrew Bible that attains much of its present form around this time.

* Late Biblical Hebrew, from the 5th to the 3rd centuries BCE, corresponding to the Persian period and represented by certain texts in the Hebrew Bible, notably the books of Ezra and Nehemiah. Basically similar to Classical Biblical Hebrew, apart from a few foreign words adopted for mainly governmental terms, and some syntactical innovations such as the use of the particle ''she-'' (alternative of "asher", meaning "that, which, who"). It adopted the Imperial Aramaic script (from which the modern Hebrew script descends).

* Israelian Hebrew is a proposed northern dialect of biblical Hebrew, believed to have existed in all eras of the language, in some cases competing with late biblical Hebrew as an explanation for non-standard linguistic features of biblical texts.

Standard Biblical Hebrew, also called Biblical Hebrew, Early Biblical Hebrew, Classical Biblical Hebrew or Classical Hebrew (in the narrowest sense), around the 8th to 6th centuries BCE, corresponding to the late Monarchic period and the Babylonian exile. It is represented by the bulk of the Hebrew Bible that attains much of its present form around this time.

* Late Biblical Hebrew, from the 5th to the 3rd centuries BCE, corresponding to the Persian period and represented by certain texts in the Hebrew Bible, notably the books of Ezra and Nehemiah. Basically similar to Classical Biblical Hebrew, apart from a few foreign words adopted for mainly governmental terms, and some syntactical innovations such as the use of the particle ''she-'' (alternative of "asher", meaning "that, which, who"). It adopted the Imperial Aramaic script (from which the modern Hebrew script descends).

* Israelian Hebrew is a proposed northern dialect of biblical Hebrew, believed to have existed in all eras of the language, in some cases competing with late biblical Hebrew as an explanation for non-standard linguistic features of biblical texts.

Early post-Biblical Hebrew

* Dead Sea Scroll Hebrew from the 3rd century BCE to the 1st century CE, corresponding to the Hellenistic and Roman Periods before the destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem, and represented by the Qumran Scrolls that form most (but not all) of the Dead Sea Scrolls. Commonly abbreviated as DSS Hebrew, also called Qumran Hebrew. The Imperial Aramaic script of the earlier scrolls in the 3rd century BCE evolved into the Hebrew square script of the later scrolls in the 1st century CE, also known as ''ketav Ashuri'' (Assyrian script), still in use today. * Mishnaic Hebrew from the 1st to the 3rd or 4th century CE, corresponding to the Roman Period after the destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem and represented by the bulk of the Mishnah and Tosefta within the Talmud and by the Dead Sea Scrolls, notably the Bar Kokhba letters and the Copper Scroll. Also called Tannaitic Hebrew or Early Rabbinic Hebrew. Sometimes the above phases of spoken Classical Hebrew are simplified into "Biblical Hebrew" (including several dialects from the 10th century BCE to 2nd century BCE and extant in certain Dead Sea Scrolls) and "Mishnaic Hebrew" (including several dialects from the 3rd century BCE to the 3rd century CE and extant in certain other Dead Sea Scrolls).M. Segal, ''A Grammar of Mishnaic Hebrew'' (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1927). However, today most Hebrew linguists classify Dead Sea Scroll Hebrew as a set of dialects evolving out of Late Biblical Hebrew and into Mishnaic Hebrew, thus including elements from both but remaining distinct from either. Qimron, Elisha (1986). ''The Hebrew of the Dead Sea Scrolls''. Harvard Semitic Studies 29. (Atlanta: Scholars Press). By the start of the Byzantine Period in the 4th century CE, Classical Hebrew ceased as a regularly spoken language, roughly a century after the publication of the Mishnah, apparently declining since the aftermath of the catastrophic Bar Kokhba revolt around 135 CE.Displacement by Aramaic

Jerusalem

Jerusalem is a city in the Southern Levant, on a plateau in the Judaean Mountains between the Mediterranean Sea, Mediterranean and the Dead Sea. It is one of the List of oldest continuously inhabited cities, oldest cities in the world, and ...

and exiling its population far to the east in Babylon. During the Babylonian captivity, many Israelites learned Aramaic, the closely related Semitic language of their captors. Thus, for a significant period, the Jewish

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of History of ancient Israel and Judah, ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, rel ...

elite became influenced by Aramaic.

After Cyrus the Great conquered Babylon, he allowed the Jewish people to return from captivity. In time, a local version of Aramaic came to be spoken in Israel alongside Hebrew. By the beginning of the Common Era

Common Era (CE) and Before the Common Era (BCE) are year notations for the Gregorian calendar (and its predecessor, the Julian calendar), the world's most widely used calendar era. Common Era and Before the Common Era are alternatives to the ...

, Aramaic was the primary colloquial language of Samarian, Babylonian and Galileean Jews, and western and intellectual Jews spoke Greek, but a form of so-called Rabbinic Hebrew continued to be used as a vernacular in Judea until it was displaced by Aramaic, probably in the 3rd century CE. Certain Sadducee, Pharisee, Scribe, Hermit, Zealot and Priest classes maintained an insistence on Hebrew, and all Jews maintained their identity with Hebrew songs and simple quotations from Hebrew texts.

While there is no doubt that at a certain point, Hebrew was displaced as the everyday spoken language of most Jews, and that its chief successor in the Middle East was the closely related Aramaic language, then Greek, scholarly opinions on the exact dating of that shift have changed very much."Hebrew" in ''The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church'', edit. F.L. Cross, first edition (Oxford, 1958), 3rd edition (Oxford 1997). ''The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church'' which once said, in 1958 in its first edition, that Hebrew "ceased to be a spoken language around the fourth century BCE", now says, in its 1997 (third) edition, that Hebrew "continued to be used as a spoken and written language in the New Testament period". In the first half of the 20th century, most scholars followed Abraham Geiger and Gustaf Dalman in thinking that Aramaic became a spoken language in the land of Israel as early as the beginning of Israel's Hellenistic period in the 4th century BCE, and that as a corollary Hebrew ceased to function as a spoken language around the same time. Moshe Zvi Segal, Joseph Klausner and Ben Yehuda are notable exceptions to this view. During the latter half of the 20th century, accumulating archaeological evidence and especially linguistic analysis of the Dead Sea Scrolls has disproven that view. The Dead Sea Scrolls, uncovered in 1946–1948 near Qumran revealed ancient Jewish texts overwhelmingly in Hebrew, not Aramaic.

The Qumran scrolls indicate that Hebrew texts were readily understandable to the average Jew, and that the language had evolved since Biblical times as spoken languages do. Recent scholarship recognizes that reports of Jews speaking in Aramaic indicate a multilingual society, not necessarily the primary language spoken. Alongside Aramaic, Hebrew co-existed within Israel as a spoken language.The Cambridge History of Judaism: The late Roman-Rabbinic period. 2006. P.460 Most scholars now date the demise of Hebrew as a spoken language to the end of the Roman period, or about 200 CE. It continued on as a literary language down through the Byzantine period from the 4th century CE.

The exact roles of Aramaic and Hebrew remain hotly debated. A trilingual scenario has been proposed for the land of Israel. Hebrew functioned as the local mother tongue with powerful ties to Israel's history, origins and golden age and as the language of Israel's religion; Aramaic functioned as the international language with the rest of the Middle East; and eventually Greek functioned as another international language with the eastern areas of the Roman Empire. William Schniedewind argues that after waning in the Persian period, the religious importance of Hebrew grew in the Hellenistic and Roman periods, and cites epigraphical evidence that Hebrew survived as a vernacular language – though both its grammar and its writing system had been substantially influenced by Aramaic. According to another summary, Greek was the language of government, Hebrew the language of prayer, study and religious texts, and Aramaic was the language of legal contracts and trade. There was also a geographic pattern: according to Bernard Spolsky, by the beginning of the Common Era, " Judeo-Aramaic was mainly used in Galilee in the north, Greek was concentrated in the former colonies and around governmental centers, and Hebrew monolingualism continued mainly in the southern villages of Judea." In other words, "in terms of dialect geography, at the time of the tannaim Palestine could be divided into the Aramaic-speaking regions of Galilee and Samaria and a smaller area, Judaea, in which Rabbinic Hebrew was used among the descendants of returning exiles."Fernandez, Miguel Perez (1997). ''An Introductory Grammar of Rabbinic Hebrew''. BRILL. In addition, it has been surmised that Koine Greek was the primary vehicle of communication in coastal cities and among the upper class of Jerusalem

Jerusalem is a city in the Southern Levant, on a plateau in the Judaean Mountains between the Mediterranean Sea, Mediterranean and the Dead Sea. It is one of the List of oldest continuously inhabited cities, oldest cities in the world, and ...

, while Aramaic was prevalent in the lower class of Jerusalem, but not in the surrounding countryside.Spolsky, B. (1985). "Jewish Multilingualism in the First century: An Essay in Historical Sociolinguistics", Joshua A. Fishman (ed.), ''Readings in The Sociology of Jewish Languages'', Leiden: E. J. Brill, pp. 35–50. Also adopted by Smelik, Willem F. 1996. The Targum of Judges. P.9 After the suppression of the Bar Kokhba revolt in the 2nd century CE, Judaeans were forced to disperse. Many relocated to Galilee, so most remaining native speakers of Hebrew at that last stage would have been found in the north.Spolsky, B. (1985), p. 40. and ''passim''

Many scholars have pointed out that Hebrew continued to be used alongside Aramaic during Second Temple times, not only for religious purposes but also for nationalistic reasons, especially during revolts such as the Maccabean Revolt (167–160 BCE) and the emergence of the Hasmonean kingdom, the Great Jewish Revolt (66–73 CE), and the Bar Kokhba revolt (132–135 CE). The nationalist significance of Hebrew manifested in various ways throughout this period. Michael Owen Wise notes that "Beginning with the time of the Hasmonean revolt ..Hebrew came to the fore in an expression akin to modern nationalism. A form of classical Hebrew was now a more significant written language than Aramaic within Judaea." This nationalist aspect was further emphasized during periods of conflict, as Hannah Cotton observing in her analysis of legal documents during the Jewish revolts against Rome that "Hebrew became the symbol of Jewish nationalism, of the independent Jewish State." The nationalist use of Hebrew is evidenced in several historical documents and artefacts, including the composition of 1 Maccabees in archaizing Hebrew, Hasmonean coinage under John Hyrcanus (134-104 BCE), and coins from both the Great Revolt and Bar Kokhba Revolt featuring exclusively Hebrew and Palaeo-Hebrew script inscriptions. This deliberate use of Hebrew and Paleo-Hebrew script in official contexts, despite limited literacy, served as a symbol of Jewish nationalism and political independence.

The Christian New Testament

The New Testament (NT) is the second division of the Christian biblical canon. It discusses the teachings and person of Jesus in Christianity, Jesus, as well as events relating to Christianity in the 1st century, first-century Christianit ...

contains some Semitic place names and quotes. The language of such Semitic glosses (and in general the language spoken by Jews in scenes from the New Testament) is often referred to as "Hebrew" in the text, although this term is often re-interpreted as referring to Aramaic instead and is rendered accordingly in recent translations. Nonetheless, these glosses can be interpreted as Hebrew as well.

Mishnah and Talmud

The term "Mishnaic Hebrew" generally refers to the Hebrew dialects found in the Talmud, excepting quotations from the Hebrew Bible. The dialects organize into Mishnaic Hebrew (also called Tannaitic Hebrew, Early Rabbinic Hebrew, or Mishnaic Hebrew I), which was a spoken language, and Amoraic Hebrew (also called Late Rabbinic Hebrew or Mishnaic Hebrew II), which was a literary language. The earlier section of the Talmud is the Mishnah that was published around 200 CE, although many of the stories take place much earlier, and were written in the earlier Mishnaic dialect. The dialect is also found in certain Dead Sea Scrolls. Mishnaic Hebrew is considered to be one of the dialects of Classical Hebrew that functioned as a living language in the land of Israel. A transitional form of the language occurs in the other works of Tannaitic literature dating from the century beginning with the completion of the Mishnah. These include the halachic Midrashim ( Sifra, Sifre, Mekhilta etc.) and the expanded collection of Mishnah-related material known as the Tosefta. The Talmud contains excerpts from these works, as well as further Tannaitic material not attested elsewhere; the generic term for these passages is '' Baraitot''. The dialect of all these works is very similar to Mishnaic Hebrew. About a century after the publication of the Mishnah, Mishnaic Hebrew fell into disuse as a spoken language. By the third century CE, sages could no longer identify the Hebrew names of many plants mentioned in the Mishnah. Only a few sages, primarily in the southern regions, retained the ability to speak the language and attempted to promote its use. According to the Jerusalem Talmud, Megillah 1:9: "Rebbi Jonathan from Bet Guvrrin said, four languages are appropriate that the world should use them, and they are these: The Foreign Language (Greek) for song, Latin for war, Syriac for elegies, Hebrew for speech. Some are saying, also Assyrian (Hebrew script) for writing." The later section of the Talmud, the Gemara, generally comments on the Mishnah and Baraitot in two forms of Aramaic. Nevertheless, Hebrew survived as a liturgical and literary language in the form of later Amoraic Hebrew, which occasionally appears in the text of the Gemara, particularly in the Jerusalem Talmud and the classical aggadah midrashes. Hebrew was always regarded as the language of Israel's religion, history and national pride, and after it faded as a spoken language, it continued to be used as a ''lingua franca

A lingua franca (; ; for plurals see ), also known as a bridge language, common language, trade language, auxiliary language, link language or language of wider communication (LWC), is a Natural language, language systematically used to make co ...

'' among scholars and Jews traveling in foreign countries. After the 2nd century CE when the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ruled the Mediterranean and much of Europe, Western Asia and North Africa. The Roman people, Romans conquered most of this during the Roman Republic, Republic, and it was ruled by emperors following Octavian's assumption of ...

exiled most of the Jewish population of Jerusalem following the Bar Kokhba revolt, they adapted to the societies in which they found themselves, yet letters, contracts, commerce, science, philosophy, medicine, poetry and laws continued to be written mostly in Hebrew, which adapted by borrowing and inventing terms.

Medieval Hebrew

Maimonides

Moses ben Maimon (1138–1204), commonly known as Maimonides (, ) and also referred to by the Hebrew acronym Rambam (), was a Sephardic rabbi and Jewish philosophy, philosopher who became one of the most prolific and influential Torah schola ...

, who developed a simple style based on Mishnaic Hebrew for use in his law code, the . Subsequent rabbinic literature is written in a blend between this style and the Aramaized Rabbinic Hebrew of the Talmud.

Hebrew persevered through the ages as the main language for written purposes by all Jewish communities around the world for a large range of uses—not only liturgy, but also poetry, philosophy, science and medicine, commerce, daily correspondence and contracts. There have been many deviations from this generalization such as Bar Kokhba's letters to his lieutenants, which were mostly in Aramaic, and Maimonides' writings, which were mostly in Arabic; but overall, Hebrew did not cease to be used for such purposes. For example, the first Middle East printing press, in Safed (modern Israel), produced a small number of books in Hebrew in 1577, which were then sold to the nearby Jewish world. This meant not only that well-educated Jews in all parts of the world could correspond in a mutually intelligible language, and that books and legal documents published or written in any part of the world could be read by Jews in all other parts, but that an educated Jew could travel and converse with Jews in distant places, just as priests and other educated Christians could converse in Latin. For example, Rabbi Avraham Danzig wrote the ' in Hebrew, as opposed to Yiddish

Yiddish, historically Judeo-German, is a West Germanic language historically spoken by Ashkenazi Jews. It originated in 9th-century Central Europe, and provided the nascent Ashkenazi community with a vernacular based on High German fused with ...

, as a guide to '' Halacha'' for the "''average'' 17-year-old" (Ibid. Introduction 1). Similarly, Rabbi Yisrael Meir Kagan's purpose in writing the ' was to "produce a work that could be studied daily so that Jews might know the proper procedures to follow minute by minute". The work was nevertheless written in Talmudic Hebrew and Aramaic, since, "the ordinary Jew f Eastern Europeof a century ago, was fluent enough in this idiom to be able to follow the Mishna Berurah without any trouble."

Revival

Hebrew has been revived several times as a literary language, most significantly by the Haskalah (Enlightenment) movement of early and mid-19th-century Germany. In the early 19th century, a form of spoken Hebrew had emerged in the markets of Jerusalem between Jews of different linguistic backgrounds to communicate for commercial purposes. This Hebrew dialect was to a certain extent a pidgin. Near the end of that century the Jewish activist Eliezer Ben-Yehuda, owing to the ideology of the national revival (, , later Zionism), began reviving Hebrew as a modern spoken language. Eventually, as a result of the local movement he created, but more significantly as a result of the new groups of immigrants known under the name of the Second Aliyah, it replaced a score of languages spoken by Jews at that time. Those languages were Jewish dialects of local languages, including Judaeo-Spanish (also called "Judezmo" and "Ladino"),

Hebrew has been revived several times as a literary language, most significantly by the Haskalah (Enlightenment) movement of early and mid-19th-century Germany. In the early 19th century, a form of spoken Hebrew had emerged in the markets of Jerusalem between Jews of different linguistic backgrounds to communicate for commercial purposes. This Hebrew dialect was to a certain extent a pidgin. Near the end of that century the Jewish activist Eliezer Ben-Yehuda, owing to the ideology of the national revival (, , later Zionism), began reviving Hebrew as a modern spoken language. Eventually, as a result of the local movement he created, but more significantly as a result of the new groups of immigrants known under the name of the Second Aliyah, it replaced a score of languages spoken by Jews at that time. Those languages were Jewish dialects of local languages, including Judaeo-Spanish (also called "Judezmo" and "Ladino"), Yiddish

Yiddish, historically Judeo-German, is a West Germanic language historically spoken by Ashkenazi Jews. It originated in 9th-century Central Europe, and provided the nascent Ashkenazi community with a vernacular based on High German fused with ...

, Judeo-Arabic and Bukhori (Tajiki), or local languages spoken in the Jewish diaspora such as Russian, Persian and Arabic

Arabic (, , or , ) is a Central Semitic languages, Central Semitic language of the Afroasiatic languages, Afroasiatic language family spoken primarily in the Arab world. The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) assigns lang ...

.

The major result of the literary work of the Hebrew intellectuals along the 19th century was a lexical modernization of Hebrew. New words and expressions were adapted as neologisms from the large corpus of Hebrew writings since the Hebrew Bible, or borrowed from Arabic (mainly by Ben-Yehuda) and older Aramaic and Latin. Many new words were either borrowed from or coined after European languages, especially English, Russian, German, and French. Modern Hebrew became an official language in British-ruled Palestine in 1921 (along with English and Arabic), and then in 1948 became an official language of the newly declared State of Israel. Hebrew is the most widely spoken language in Israel today.

In the Modern Period, from the 19th century onward, the literary Hebrew tradition revived as the spoken language of modern Israel, called variously ''Israeli Hebrew'', ''Modern Israeli Hebrew'', ''Modern Hebrew'', ''New Hebrew'', ''Israeli Standard Hebrew'', ''Standard Hebrew'' and so on. Israeli Hebrew exhibits some features of Sephardic Hebrew from its local Jerusalemite tradition but adapts it with numerous neologisms, borrowed terms (often technical) from European languages and adopted terms (often colloquial) from Arabic.

The literary and narrative use of Hebrew was revived beginning with the Haskalah movement. The first secular periodical in Hebrew, (The Gatherer), was published by maskilim in Königsberg (today's Kaliningrad) from 1783 onwards. In the mid-19th century, publications of several Eastern European Hebrew-language newspapers (e.g. , founded in Ełk in 1856) multiplied. Prominent poets were Hayim Nahman Bialik and Shaul Tchernichovsky; there were also novels written in the language.

The revival of the Hebrew language as a mother tongue was initiated in the late 19th century by the efforts of Ben-Yehuda. He joined the Jewish national movement and in 1881 immigrated to Palestine, then a part of the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

. Motivated by the surrounding ideals of renovation and rejection of the diaspora " shtetl" lifestyle, Ben-Yehuda set out to develop tools for making the literary and liturgical language into everyday spoken language. However, his brand of Hebrew followed norms that had been replaced in Eastern Europe by different grammar and style, in the writings of people like Ahad Ha'am and others. His organizational efforts and involvement with the establishment of schools and the writing of textbooks pushed the vernacularization activity into a gradually accepted movement. It was not, however, until the 1904–1914 Second Aliyah that Hebrew had caught real momentum in Ottoman Palestine with the more highly organized enterprises set forth by the new group of immigrants. When the British Mandate of Palestine recognized Hebrew as one of the country's three official languages (English, Arabic, and Hebrew, in 1922), its new formal status contributed to its diffusion. A constructed modern language with a truly Semitic vocabulary and written appearance, although often European in phonology

Phonology (formerly also phonemics or phonematics: "phonemics ''n.'' 'obsolescent''1. Any procedure for identifying the phonemes of a language from a corpus of data. 2. (formerly also phonematics) A former synonym for phonology, often pre ...

, was to take its place among the current languages of the nations.

While many saw his work as fanciful or even blasphemous (because Hebrew was the holy language of the Torah and therefore some thought that it should not be used to discuss everyday matters), many soon understood the need for a common language amongst Jews of the British Mandate who at the turn of the 20th century were arriving in large numbers from diverse countries and speaking different languages. A Committee of the Hebrew Language was established. After the establishment of Israel, it became the Academy of the Hebrew Language. The results of Ben-Yehuda's lexicographical work were published in a dictionary (''The Complete Dictionary of Ancient and Modern Hebrew'', Ben-Yehuda Dictionary). The seeds of Ben-Yehuda's work fell on fertile ground, and by the beginning of the 20th century, Hebrew was well on its way to becoming the main language of the Jewish population of both Ottoman and British Palestine. At the time, members of the Old Yishuv and a very few Hasidic sects, most notably those under the auspices of Satmar, refused to speak Hebrew and spoke only Yiddish.

In the Soviet Union, the use of Hebrew, along with other Jewish cultural and religious activities, was suppressed. Soviet authorities considered the use of Hebrew "reactionary" since it was associated with Zionism, and the teaching of Hebrew at primary and secondary schools was officially banned by the People's Commissariat for Education as early as 1919, as part of an overall agenda aiming to secularize education (the language itself did not cease to be studied at universities for historical and linguistic purposes). The official ordinance stated that Yiddish, being the spoken language of the Russian Jews, should be treated as their only national language, while Hebrew was to be treated as a foreign language. Hebrew books and periodicals ceased to be published and were seized from the libraries, although liturgical texts were still published until the 1930s. Despite numerous protests, a policy of suppression of the teaching of Hebrew operated from the 1930s on. Later in the 1980s in the USSR, Hebrew studies reappeared due to people struggling for permission to go to Israel ( refuseniks). Several of the teachers were imprisoned, e.g. Yosef Begun, Ephraim Kholmyansky, Yevgeny Korostyshevsky and others responsible for a Hebrew learning network connecting many cities of the USSR.

Modern Hebrew

phonology

Phonology (formerly also phonemics or phonematics: "phonemics ''n.'' 'obsolescent''1. Any procedure for identifying the phonemes of a language from a corpus of data. 2. (formerly also phonematics) A former synonym for phonology, often pre ...

in some respects, mainly the following:

* the replacement of pharyngeal articulation in the letters ''chet'' () and ''ayin'' () by most Hebrew speakers with uvular big>and glottal big> respectively, by most Hebrew speakers.

* the conversion of ( ) from an alveolar flap to a voiced uvular fricative or uvular trill , by most of the speakers, like in most varieties of standard German or Yiddish. ''see Guttural R''

* the pronunciation (by many speakers) of '' tzere'' <> as in some contexts (''sifréj'' and ''téjša'' instead of Sephardic ''sifré'' and ''tésha'')

* the partial elimination of vocal '' Shva'' <> (''zmán'' instead of Sephardic ''zĕman'')

* in popular speech, penultimate stress in proper names (''Dvóra'' instead of ''Dĕvorá''; ''Yehúda'' instead of ''Yĕhudá'') and some other words

* similarly in popular speech, penultimate stress in verb forms with a second person plural suffix (''katávtem'' "you wrote" instead of ''kĕtavtém'').

The vocabulary of Israeli Hebrew is much larger than that of earlier periods. According to Ghil'ad Zuckermann:

In Israel, Modern Hebrew is currently taught in institutions called Ulpanim (singular: Ulpan). There are government-owned, as well as private, Ulpanim offering online courses and face-to-face programs.

Current status

Arabic

Arabic (, , or , ) is a Central Semitic languages, Central Semitic language of the Afroasiatic languages, Afroasiatic language family spoken primarily in the Arab world. The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) assigns lang ...

, French, English, Yiddish

Yiddish, historically Judeo-German, is a West Germanic language historically spoken by Ashkenazi Jews. It originated in 9th-century Central Europe, and provided the nascent Ashkenazi community with a vernacular based on High German fused with ...

and Ladino being the native tongues of most of the rest. Some 26% of immigrants from the former Soviet Union and 12% of Arabs reported speaking Hebrew poorly or not at all.

Steps have been taken to keep Hebrew the primary language of use, and to prevent large-scale incorporation of English words into the Hebrew vocabulary. The Academy of the Hebrew Language of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem currently invents about 2,000 new Hebrew words each year for modern words by finding an original Hebrew word that captures the meaning, as an alternative to incorporating more English words into Hebrew vocabulary. The Haifa

Haifa ( ; , ; ) is the List of cities in Israel, third-largest city in Israel—after Jerusalem and Tel Aviv—with a population of in . The city of Haifa forms part of the Haifa metropolitan area, the third-most populous metropolitan area i ...

municipality has banned officials from using English words in official documents, and is fighting to stop businesses from using only English signs to market their services. In 2012, a Knesset bill for the preservation of the Hebrew language was proposed, which includes the stipulation that all signage in Israel must first and foremost be in Hebrew, as with all speeches by Israeli officials abroad. The bill's author, MK Akram Hasson, stated that the bill was proposed as a response to Hebrew "losing its prestige" and children incorporating more English words into their vocabulary.

Hebrew is one of several languages for which the constitution of South Africa calls to be respected in their use for religious purposes. Also, Hebrew is an official national minority language in Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It extends from the Baltic Sea in the north to the Sudetes and Carpathian Mountains in the south, bordered by Lithuania and Russia to the northeast, Belarus and Ukrai ...

, since 6 January 2005. Hamas has made Hebrew a compulsory language taught in schools in the Gaza Strip.

Phonology

Biblical Hebrew

Biblical Hebrew ( or ), also called Classical Hebrew, is an archaic form of the Hebrew language, a language in the Canaanite languages, Canaanitic branch of the Semitic languages spoken by the Israelites in the area known as the Land of Isra ...

had a typical Semitic consonant inventory, with pharyngeal , a series of "emphatic" consonants (possibly ejective, but this is debated), lateral fricative , and in its older stages also uvular . merged into in later Biblical Hebrew, and underwent allophonic spirantization to (known as begadkefat

Begadkefat (also begedkefet) is the phenomenon of lenition affecting the non-emphatic consonant, emphatic stop consonants of Biblical Hebrew and Aramaic when they are preceded by a vowel and not gemination, geminated. The name is also given to si ...

). The earliest Biblical Hebrew vowel system contained the Proto-Semitic vowels as well as , but this system changed dramatically over time.

By the time of the Dead Sea Scrolls, had shifted to in the Jewish traditions, though for the Samaritans it merged with instead. The Tiberian reading tradition of the Middle Ages had the vowel system , though other Medieval reading traditions had fewer vowels.

A number of reading traditions have been preserved in liturgical use. In Oriental ( Sephardi and Mizrahi) Jewish reading traditions, the emphatic consonants are realized as pharyngealized, while the Ashkenazi

Ashkenazi Jews ( ; also known as Ashkenazic Jews or Ashkenazim) form a distinct subgroup of the Jewish diaspora, that Ethnogenesis, emerged in the Holy Roman Empire around the end of the first millennium Common era, CE. They traditionally spe ...

(northern and eastern European) traditions have lost emphatics and pharyngeals (although according to Ashkenazi law, pharyngeal articulation is preferred over uvular or glottal articulation when representing the community in religious service such as prayer and Torah reading), and show the shift of to . The Samaritan tradition has a complex vowel system that does not correspond closely to the Tiberian systems.

Modern Hebrew pronunciation developed from a mixture of the different Jewish reading traditions, generally tending towards simplification. In line with Sephardi Hebrew pronunciation, emphatic consonants have shifted to their ordinary counterparts, to , and are not present. Most Israelis today also merge with , do not have contrastive gemination, and pronounce as a uvular fricative or a voiced velar fricative rather than an alveolar trill, because of Ashkenazi Hebrew influences. The consonants and have become phonemic due to loan words, and has similarly been re-introduced.

Consonants

Notes: # Proto-Semitic was still pronounced as in Biblical Hebrew, but no letter was available in the Phoenician alphabet, so the letter had two pronunciations, representing both and . Later on, however, merged with , but the old spelling was largely retained, and the two pronunciations of were distinguished graphically in Tiberian Hebrew as vs. < . # Biblical Hebrew as of the 3rd century BCE apparently still distinguished the phonemes versus and versus , as witnessed by transcriptions in theSeptuagint

The Septuagint ( ), sometimes referred to as the Greek Old Testament or The Translation of the Seventy (), and abbreviated as LXX, is the earliest extant Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible from the original Biblical Hebrew. The full Greek ...

. As in the case of , no letters were available to represent these sounds, and existing letters did double duty: for and for . In all of these cases, however, the sounds represented by the same letter eventually merged, leaving no evidence (other than early transcriptions) of the former distinctions.

# Hebrew and Aramaic underwent begadkefat

Begadkefat (also begedkefet) is the phenomenon of lenition affecting the non-emphatic consonant, emphatic stop consonants of Biblical Hebrew and Aramaic when they are preceded by a vowel and not gemination, geminated. The name is also given to si ...

spirantization at a certain point, whereby the stop sounds were softened to the corresponding fricatives (written ''ḇ ḡ ḏ ḵ p̄ ṯ'') when occurring after a vowel and not geminated. This change probably happened after the original Old Aramaic phonemes disappeared in the 7th century BCE, and most likely occurred after the loss of Hebrew .According to the generally accepted view, it is unlikely that begadkefat spirantization occurred before the merger of and , or else and would have to be contrastive, which is cross-linguistically rare. However, Blau argues that it is possible that lenited and could coexist even if pronounced identically, since one would be recognized as an alternating allophone (as apparently is the case in Nestorian Syriac). See . It is known to have occurred in Hebrew by the 2nd century. After a certain point this alternation became contrastive in word-medial and final position (though bearing low functional load), but in word-initial position they remained allophonic. No text access via Google Books. In Modern Hebrew, the distinction has a higher functional load due to the loss of gemination, although only the three fricatives are still preserved (the fricative is pronounced in modern Hebrew). (The others are pronounced like the corresponding stops, as Modern Hebrew pronunciation was based on the Sephardic pronunciation which lost the distinction)

Grammar

Hebrew grammar is partly analytic, expressing such forms as dative, ablative and accusative using prepositional particles rather than grammatical cases. However, inflection plays a decisive role in the formation of verbs and nouns. For example, nouns have a construct state, called "''smikhut''", to denote the relationship of "belonging to": this is the converse of thegenitive case

In grammar, the genitive case ( abbreviated ) is the grammatical case that marks a word, usually a noun, as modifying another word, also usually a noun—thus indicating an attributive relationship of one noun to the other noun. A genitive ca ...

of more inflected languages. Words in ''smikhut'' are often combined with hyphens. In modern speech, the use of the construct is sometimes interchangeable with the preposition "''shel''", meaning "of". There are many cases, however, where older declined forms are retained (especially in idiomatic expressions and the like), and "person"- enclitics are widely used to "decline" prepositions.

Morphology

Like all Semitic languages, the Hebrew language exhibits a pattern of stems consisting typically of " triliteral", or 3-consonant consonantal roots, from which nouns, adjectives, and verbs are formed in various ways: e.g. by inserting vowels, doubling consonants, lengthening vowels and/or adding prefixes, suffixes or infixes. 4-consonant roots also exist and became more frequent in the modern language due to a process of coining verbs from nouns that are themselves constructed from 3-consonant verbs. Some triliteral roots lose one of their consonants in most forms and are called "Nakhim" (Resting). Hebrew uses a number of one-letter prefixes that are added to words for various purposes. These are called inseparable prepositions or "Letters of Use" (). Such items include: the definite article ''ha-'' () (= "the"); prepositions ''be-'' () (= "in"), ''le-'' () (= "to"; a shortened version of the preposition ''el''), ''mi-'' () (= "from"; a shortened version of the preposition ''min''); conjunctions ''ve-'' () (= "and"), ''she-'' () (= "that"; a shortened version of the Biblical conjunction ''asher''), ''ke-'' () (= "as", "like"; a shortened version of the conjunction ''kmo''). The vowel accompanying each of these letters may differ from those listed above, depending on the first letter or vowel following it. The rules governing these changes are hardly observed in colloquial speech as most speakers tend to employ the regular form. However, they may be heard in more formal circumstances. For example, if a preposition is put before a word that begins with a moving Shva, then the preposition takes the vowel (and the initial consonant may be weakened): colloquial ''be-kfar'' (= "in a village") corresponds to the more formal ''bi-khfar''. The definite article may be inserted between a preposition or a conjunction and the word it refers to, creating composite words like ''mé-ha-kfar'' (= "from the village"). The latter also demonstrates the change in the vowel of ''mi-''. With ''be'', ''le'' and ''ke'', the definite article is assimilated into the prefix, which then becomes ''ba'', ''la'' or ''ka''. Thus *''be-ha-matos'' becomes ''ba-matos'' (= "in the plane"). This does not happen to ''mé'' (the form of "min" or "mi-" used before the letter "he"), therefore ''mé-ha-matos'' is a valid form, which means "from the airplane". :''* indicates that the given example is grammatically non-standard''.Syntax

Like most other languages, the vocabulary of the Hebrew language is divided into verbs, nouns, adjectives and so on, and its sentence structure can be analyzed by terms like object, subject and so on. * Though earlyBiblical Hebrew

Biblical Hebrew ( or ), also called Classical Hebrew, is an archaic form of the Hebrew language, a language in the Canaanite languages, Canaanitic branch of the Semitic languages spoken by the Israelites in the area known as the Land of Isra ...

had a VSO ordering, this gradually transitioned to a subject-verb-object ordering. Many Hebrew sentences have several correct orders of words.

* In Hebrew, there is no indefinite article

In grammar, an article is any member of a class of dedicated words that are used with noun phrases to mark the identifiability of the referents of the noun phrases. The category of articles constitutes a part of speech.

In English, both "the ...

.

* Hebrew sentences do not have to include verbs; the copula in the present tense is omitted. For example, the sentence "I am here" ( ') has only two words; one for I () and one for here (). In the sentence "I am that person" ( '), the word for "am" corresponds to the word for "he" (). However, this is usually omitted. Thus, the sentence () is more often used and means the same thing.

*Negative and interrogative sentences have the same order as the regular declarative one. A question that has a yes/no answer begins with (''ha'im'', an interrogative form of 'if'), but it is largely omitted in informal speech.

* In Hebrew there is a specific preposition ( ') for direct objects that would not have a preposition marker in English. The English phrase "he ate the cake" would in Hebrew be ' (literally, "He ate the cake"). The word , however, can be omitted, making ' ("He ate the cake"). Former Israeli Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion was convinced that should never be used as it elongates the sentence without adding meaning.

* In spoken Hebrew is also often contracted to , e.g. instead of (the ' indicates non-standard use). This phenomenon has also been found by researchers in the Bar Kokhba documents: , writing instead of , as well as and so on.

Writing system

Users of the language write Modern Hebrew from right to left using the Hebrew alphabet – an "impure" abjad, or consonant-only script, of 22 letters. The ancient Paleo-Hebrew alphabet resembles those used for Canaanite and Phoenician. Modern scripts derive from the "square" letter form, known as ''Ashurit'' (Assyrian), which developed from the Aramaic script. A cursive Hebrew script is used in handwriting: the letters tend to appear more circular in form when written in cursive, and sometimes vary markedly from their printed equivalents. The medieval version of the cursive script forms the basis of another style, known as Rashi script. When necessary, vowels are indicated by diacritic marks above or below the letter representing the syllabic onset, or by use of '' matres lectionis'', which are consonantal letters used as vowels. Further diacritics may serve to indicate variations in the pronunciation of the consonants (e.g. ''bet''/''vet'', ''shin''/''sin''); and, in some contexts, to indicate the punctuation, accentuation and musical rendition of Biblical texts (see Hebrew cantillation).

Users of the language write Modern Hebrew from right to left using the Hebrew alphabet – an "impure" abjad, or consonant-only script, of 22 letters. The ancient Paleo-Hebrew alphabet resembles those used for Canaanite and Phoenician. Modern scripts derive from the "square" letter form, known as ''Ashurit'' (Assyrian), which developed from the Aramaic script. A cursive Hebrew script is used in handwriting: the letters tend to appear more circular in form when written in cursive, and sometimes vary markedly from their printed equivalents. The medieval version of the cursive script forms the basis of another style, known as Rashi script. When necessary, vowels are indicated by diacritic marks above or below the letter representing the syllabic onset, or by use of '' matres lectionis'', which are consonantal letters used as vowels. Further diacritics may serve to indicate variations in the pronunciation of the consonants (e.g. ''bet''/''vet'', ''shin''/''sin''); and, in some contexts, to indicate the punctuation, accentuation and musical rendition of Biblical texts (see Hebrew cantillation).

Liturgical use in Judaism

Hebrew has always been used as the language of prayer and study, and the following pronunciation systems are found. Ashkenazi Hebrew, originating in Central and Eastern Europe, is still widely used in Ashkenazi Jewish religious services and studies in Israel and abroad, particularly in the Haredi and other Orthodox communities. It was influenced byYiddish

Yiddish, historically Judeo-German, is a West Germanic language historically spoken by Ashkenazi Jews. It originated in 9th-century Central Europe, and provided the nascent Ashkenazi community with a vernacular based on High German fused with ...

pronunciation.

Sephardi Hebrew is the traditional pronunciation of the Spanish and Portuguese Jews and Sephardi Jews in the countries of the former Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

, with the exception of Yemenite Hebrew. This pronunciation, in the form used by the Jerusalem Sephardic community, is the basis of the Hebrew phonology of Israeli native speakers. It was influenced by Ladino pronunciation.

Mizrahi (Oriental) Hebrew is actually a collection of dialects spoken liturgically by Jews in various parts of the Arab and Islam

Islam is an Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the Quran, and the teachings of Muhammad. Adherents of Islam are called Muslims, who are estimated to number Islam by country, 2 billion worldwide and are the world ...

ic world. It was derived from the old Arabic language

Arabic (, , or , ) is a Central Semitic languages, Central Semitic language of the Afroasiatic languages, Afroasiatic language family spoken primarily in the Arab world. The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) assigns lang ...

, and in some cases influenced by Sephardi Hebrew. Yemenite Hebrew or ''Temanit'' differs from other Mizrahi dialects by having a radically different vowel system, and distinguishing between different diacritically marked consonants that are pronounced identically in other dialects (for example gimel and "ghimel".)

These pronunciations are still used in synagogue ritual and religious study in Israel and elsewhere, mostly by people who are not native speakers of Hebrew. However, some traditionalist Israelis use liturgical pronunciations in prayer.