François Arago on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Dominique François Jean Arago (), known simply as François Arago (; Catalan: , ; 26 February 17862 October 1853), was a French

In 1830, Arago, who always professed liberal opinions of the republican type, was elected a member of the chamber of deputies for the

In 1830, Arago, who always professed liberal opinions of the republican type, was elected a member of the chamber of deputies for the

* The study association for Applied Physics at the

* The study association for Applied Physics at the

A Mode of producing Arago's Rotation

'. 28 June 1879. (Philosophical magazine: a journal of theoretical, experimental and applied physics. Taylor & Francis., 1879)

''Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society'', 1854, volume 14, page 102 *

misused in ''The Da Vinci Code'' is in fact an art project by the Dutch artist Jan Dibbets (1941) made in 1987 as a tribute to the astronomer François Arago (1786–1853)

S.V. Arago The study association for applied physics

(Dutch) at the

Portrait of Francois F. Arago from the Lick Observatory Records Digital Archive, UC Santa Cruz Library's Digital Collections

« Arago et l’Observatoire de Paris »Virtual exhibition on Paris Observatory digital library

{{DEFAULTSORT:Arago, Francois 1786 births 1853 deaths 19th-century heads of state of France People from Pyrénées-Orientales Politicians from Occitania (administrative region) Moderate Republicans (France) Heads of state of France Ministers of war of France Ministers of marine and the colonies Members of the 2nd Chamber of Deputies of the July Monarchy Members of the 3rd Chamber of Deputies of the July Monarchy Members of the 4th Chamber of Deputies of the July Monarchy Members of the 5th Chamber of Deputies of the July Monarchy Members of the 6th Chamber of Deputies of the July Monarchy Members of the 7th Chamber of Deputies of the July Monarchy Members of the 1848 Constituent Assembly Members of the National Legislative Assembly of the French Second Republic 19th-century French mathematicians Scientists from Catalonia 19th-century French astronomers French atheists French Freemasons 19th-century French physicists Vision scientists French people of the Revolutions of 1848 École Polytechnique alumni Members of the French Academy of Sciences Honorary Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh Honorary members of the Saint Petersburg Academy of Sciences Members of the Royal Academy of Belgium Members of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences Members of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences Officers of the French Academy of Sciences Fellows of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences Foreign members of the Royal Society Recipients of the Copley Medal Recipients of the Pour le Mérite (civil class) Burials at Père Lachaise Cemetery 18th-century atheists 19th-century atheists Members of the Göttingen Academy of Sciences and Humanities French geodesists

mathematician

A mathematician is someone who uses an extensive knowledge of mathematics in their work, typically to solve mathematical problems. Mathematicians are concerned with numbers, data, quantity, mathematical structure, structure, space, Mathematica ...

, physicist

A physicist is a scientist who specializes in the field of physics, which encompasses the interactions of matter and energy at all length and time scales in the physical universe. Physicists generally are interested in the root or ultimate cau ...

, astronomer

An astronomer is a scientist in the field of astronomy who focuses on a specific question or field outside the scope of Earth. Astronomers observe astronomical objects, such as stars, planets, natural satellite, moons, comets and galaxy, galax ...

, freemason

Freemasonry (sometimes spelled Free-Masonry) consists of fraternal groups that trace their origins to the medieval guilds of stonemasons. Freemasonry is the oldest secular fraternity in the world and among the oldest still-existing organizati ...

, supporter of the Carbonari

The Carbonari () was an informal network of Secret society, secret revolutionary societies active in Italy from about 1800 to 1831. The Carbonari may have further influenced other revolutionary groups in France, Portugal, Spain, Brazil, Urugua ...

revolutionaries and politician.

Early life and work

Arago was born at Estagel, a small village of 3,000 nearPerpignan

Perpignan (, , ; ; ) is the prefectures in France, prefecture of the Pyrénées-Orientales departments of France, department in Southern France, in the heart of the plain of Roussillon, at the foot of the Pyrenees a few kilometres from the Me ...

, in the ' of Pyrénées-Orientales

Pyrénées-Orientales (; ; ; ), also known as Northern Catalonia, is a departments of France, department of the Regions of France, region of Occitania (administrative region), Occitania, Southern France, adjacent to the northern Spain, Spanish ...

, France, where his father held the position of Treasurer of the Mint.

His parents were François Bonaventure Arago (1754–1814) and Marie Arago (1755–1845).

Arago was the eldest of four brothers. Jean (1788–1836) emigrated to North America and became a general in the Mexican army. Jacques Étienne Victor (1799–1855) took part in Louis de Freycinet

Louis Claude de Saulces de Freycinet (7 August 1779 – 18 August 1841) was a French Navy officer. He circumnavigated the Earth, and in 1811 published the first map to show a full outline of the coastline of Australia.

Biography

He was born at M ...

's exploring voyage in the ''Uranie'' from 1817 to 1821, and on his return to France devoted himself to his journalism and the drama. The fourth brother, Étienne Vincent (1802–1892), is said to have collaborated with Honoré de Balzac

Honoré de Balzac ( , more commonly ; ; born Honoré Balzac; 20 May 1799 – 18 August 1850) was a French novelist and playwright. The novel sequence ''La Comédie humaine'', which presents a panorama of post-Napoleonic French life, is ...

in ''The Heiress of Birague'', and from 1822 to 1847 wrote a great number of light dramatic pieces, mostly in collaboration.

Showing decided military tastes, François Arago was sent to the municipal college of Perpignan

Perpignan (, , ; ; ) is the prefectures in France, prefecture of the Pyrénées-Orientales departments of France, department in Southern France, in the heart of the plain of Roussillon, at the foot of the Pyrenees a few kilometres from the Me ...

, where he began to study mathematics

Mathematics is a field of study that discovers and organizes methods, Mathematical theory, theories and theorems that are developed and Mathematical proof, proved for the needs of empirical sciences and mathematics itself. There are many ar ...

in preparation for the entrance examination of the . Within two years and a half he had mastered all the subjects prescribed for examination, and a great deal more, and, on going up for examination at Toulouse

Toulouse (, ; ; ) is a city in southern France, the Prefectures in France, prefecture of the Haute-Garonne department and of the Occitania (administrative region), Occitania region. The city is on the banks of the Garonne, River Garonne, from ...

, he astounded his examiner by his knowledge of J.-L. Lagrange's work.

Towards the close of 1803, Arago entered the , Paris, but apparently found the professors there incapable of imparting knowledge or maintaining discipline. The artillery

Artillery consists of ranged weapons that launch Ammunition, munitions far beyond the range and power of infantry firearms. Early artillery development focused on the ability to breach defensive walls and fortifications during sieges, and l ...

service was his ambition, and in 1804, through the advice and recommendation of Siméon Poisson, he received the appointment of secretary to the Paris Observatory

The Paris Observatory (, ), a research institution of the Paris Sciences et Lettres University, is the foremost astronomical observatory of France, and one of the largest astronomical centres in the world. Its historic building is on the Left Ban ...

. He now became acquainted with Pierre-Simon Laplace

Pierre-Simon, Marquis de Laplace (; ; 23 March 1749 – 5 March 1827) was a French polymath, a scholar whose work has been instrumental in the fields of physics, astronomy, mathematics, engineering, statistics, and philosophy. He summariz ...

, and through his influence was commissioned, with Jean-Baptiste Biot

Jean-Baptiste Biot (; ; 21 April 1774 – 3 February 1862) was a French people, French physicist, astronomer, and mathematician who co-discovered the Biot–Savart law of magnetostatics with Félix Savart, established the reality of meteorites, ma ...

, to complete the meridian arc

In geodesy and navigation, a meridian arc is the curve (geometry), curve between two points near the Earth's surface having the same longitude. The term may refer either to a arc (geometry), segment of the meridian (geography), meridian, or to its ...

measurements which had been begun by J. B. J. Delambre, and interrupted since the death of P. F. A. Méchain in 1804 (the meridian arc of Delambre and Méchain).

Arago and Biot left Paris in 1806 and began operations along the mountains of Spain.

Biot returned to Paris after they had determined the latitude of Formentera

Formentera (, ) is a Spanish island located in the Mediterranean Sea, which belongs to the Balearic Islands autonomous community (Spain) together with Mallorca, Menorca, and Ibiza.

Formentera is the smallest and most southerly island of the ...

, the southernmost point to which they were to carry the survey. Arago continued the work until 1809, his purpose being to measure a meridian arc in order to determine the exact length of a metre (see Paris meridian#History).

After Biot's departure, the political ferment caused by the entrance of the French into Spain extended to the Balearic Islands

The Balearic Islands are an archipelago in the western Mediterranean Sea, near the eastern coast of the Iberian Peninsula. The archipelago forms a Provinces of Spain, province and Autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Spain, ...

, and the population suspected Arago's movements and his lighting of fires on the top of Mount Galatzó ( Catalan: Mola de l'Esclop) as the activities of a spy for the invading army. Their reaction was such that he was obliged to give himself up for imprisonment in the fortress of Bellver in June 1808. On 28 July he escaped from the island in a fishing-boat, and after an adventurous voyage he reached Algiers

Algiers is the capital city of Algeria as well as the capital of the Algiers Province; it extends over many Communes of Algeria, communes without having its own separate governing body. With 2,988,145 residents in 2008Census 14 April 2008: Offi ...

on 3 August. From there he obtained a passage in a vessel bound for Marseille

Marseille (; ; see #Name, below) is a city in southern France, the Prefectures in France, prefecture of the Departments of France, department of Bouches-du-Rhône and of the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur Regions of France, region. Situated in the ...

, but on 16 August, just as the vessel was nearing Marseille, it fell into the hands of a Spanish corsair. With the rest the crew, Arago was taken to Roses

A rose is either a woody perennial flowering plant of the genus ''Rosa'' (), in the family Rosaceae (), or the flower it bears. There are over three hundred species and tens of thousands of cultivars. They form a group of plants that can be e ...

, and imprisoned first in a windmill, and afterwards in a fortress, until the town fell into the hands of the French, when the prisoners were transferred to Palamos.

After three months' imprisonment, Arago and the others were released on the demand of the dey

Dey (, from ) was the title given to the rulers of the regencies of Algiers, Tripolitania,Bertarelli (1929), p. 203. and Tunis under the Ottoman Empire from 1671 onwards. Twenty-nine ''deys'' held office from the establishment of the deylicate ...

of Algiers, and again set sail for Marseille on 28 November, but then within sight of their port they were driven back by a northerly wind to Bougie on the coast of Africa. Transport to Algiers by sea from this place would have occasioned a weary delay of three months; Arago, therefore, set out over land, guided by a Muslim priest, and reached it on Christmas Day. After six months in Algiers he once again, on 21 June 1809, set sail for Marseille, where he had to undergo a monotonous and inhospitable quarantine in the lazaretto

A lazaretto ( ), sometimes lazaret or lazarette ( ), is a quarantine station for maritime travelers. Lazarets can be ships permanently at anchor, isolated islands, or mainland buildings. In some lazarets, postal items were also disinfected, usu ...

, before his difficulties were over. The first letter he received, while in the lazaretto, was from Alexander von Humboldt

Friedrich Wilhelm Heinrich Alexander von Humboldt (14 September 1769 – 6 May 1859) was a German polymath, geographer, natural history, naturalist, List of explorers, explorer, and proponent of Romanticism, Romantic philosophy and Romanticism ...

; and this was the origin of a connection which, in Arago's words, "lasted over forty years without a single cloud ever having troubled it."

Scientific studies

Arago had succeeded in preserving the records of his survey; and his first act on his return home was to deposit them in theBureau des Longitudes

__NOTOC__

The ''Bureau des Longitudes'' () is a French scientific institution, founded by decree of 25 June 1795 and charged with the improvement of nautical navigation, standardisation of time-keeping, geodesy and astronomical observation. Durin ...

at Paris. As a reward for his adventurous conduct in the cause of science, he was elected a member of the French Academy of Sciences

The French Academy of Sciences (, ) is a learned society, founded in 1666 by Louis XIV at the suggestion of Jean-Baptiste Colbert, to encourage and protect the spirit of French Scientific method, scientific research. It was at the forefron ...

, at the remarkably early age of twenty-three, and before the close of 1809 he was chosen by the council of the to succeed Gaspard Monge

Gaspard Monge, Comte de Péluse (; 9 May 1746 – 28 July 1818) was a French mathematician, commonly presented as the inventor of descriptive geometry, (the mathematical basis of) technical drawing, and the father of differential geometry. Dur ...

in the chair of analytical geometry. At the same time he was named by the emperor one of the astronomers of the Paris Observatory

The Paris Observatory (, ), a research institution of the Paris Sciences et Lettres University, is the foremost astronomical observatory of France, and one of the largest astronomical centres in the world. Its historic building is on the Left Ban ...

, which was accordingly his residence till his death. It was in this capacity that he delivered his remarkably successful series of popular lectures in astronomy, which were continued from 1812 to 1845.

In 1818 or 1819 he proceeded along with Biot to execute geodetic operations on the coasts of France, England and Scotland. They measured the length of the seconds pendulum

A seconds pendulum is a pendulum whose period is precisely two seconds; one second for a swing in one direction and one second for the return swing, a frequency of 0.5 Hz.

Principles

A pendulum is a weight suspended from a pivot so tha ...

at Leith

Leith (; ) is a port area in the north of Edinburgh, Scotland, founded at the mouth of the Water of Leith and is home to the Port of Leith.

The earliest surviving historical references are in the royal charter authorising the construction of ...

, Scotland, and in the Shetland Islands

Shetland (until 1975 spelled Zetland), also called the Shetland Islands, is an archipelago in Scotland

Scotland is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It contains nearly one-third of the Uni ...

, the results of the observations being published in 1821, along with those made in Spain. Arago was elected a member of the Bureau des Longitudes immediately afterwards, and contributed to each of its Annuals, for about twenty-two years, important scientific notices on astronomy and meteorology

Meteorology is the scientific study of the Earth's atmosphere and short-term atmospheric phenomena (i.e. weather), with a focus on weather forecasting. It has applications in the military, aviation, energy production, transport, agricultur ...

and occasionally on civil engineering

Civil engineering is a regulation and licensure in engineering, professional engineering discipline that deals with the design, construction, and maintenance of the physical and naturally built environment, including public works such as roads ...

, as well as interesting memoirs of members of the Academy.

Arago's earliest physical researches were on the pressure

Pressure (symbol: ''p'' or ''P'') is the force applied perpendicular to the surface of an object per unit area over which that force is distributed. Gauge pressure (also spelled ''gage'' pressure)The preferred spelling varies by country and eve ...

of steam

Steam is water vapor, often mixed with air or an aerosol of liquid water droplets. This may occur due to evaporation or due to boiling, where heat is applied until water reaches the enthalpy of vaporization. Saturated or superheated steam is inv ...

at different temperatures, and the velocity

Velocity is a measurement of speed in a certain direction of motion. It is a fundamental concept in kinematics, the branch of classical mechanics that describes the motion of physical objects. Velocity is a vector (geometry), vector Physical q ...

of sound, 1818 to 1822. His magnet

A magnet is a material or object that produces a magnetic field. This magnetic field is invisible but is responsible for the most notable property of a magnet: a force that pulls on other ferromagnetic materials, such as iron, steel, nickel, ...

ic observations mostly took place from 1823 to 1826. He discovered rotatory magnetism, what has been called Arago's rotations, and the fact that most bodies could be magnetized; these discoveries were completed and explained by Michael Faraday

Michael Faraday (; 22 September 1791 – 25 August 1867) was an English chemist and physicist who contributed to the study of electrochemistry and electromagnetism. His main discoveries include the principles underlying electromagnetic inducti ...

.

Arago warmly supported Augustin-Jean Fresnel

Augustin-Jean Fresnel (10 May 1788 – 14 July 1827) was a French civil engineer and physicist whose research in optics led to the almost unanimous acceptance of the wave theory of light, excluding any remnant of Isaac Newton, Newton's c ...

's optical

Optics is the branch of physics that studies the behaviour and properties of light, including its interactions with matter and the construction of instruments that use or detect it. Optics usually describes the behaviour of visible, ultravio ...

theories, helping to confirm Fresnel's wave theory of light

In physics, physical optics, or wave optics, is the branch of optics that studies interference, diffraction, polarization, and other phenomena for which the ray approximation of geometric optics is not valid. This usage tends not to include effec ...

by observing what is now known as the spot of Arago. The two philosophers conducted together those experiments on the polarization of light which led to the inference that the vibration

Vibration () is a mechanical phenomenon whereby oscillations occur about an equilibrium point. Vibration may be deterministic if the oscillations can be characterised precisely (e.g. the periodic motion of a pendulum), or random if the os ...

s of the luminiferous ether were transverse to the direction of motion

In physics, motion is when an object changes its position with respect to a reference point in a given time. Motion is mathematically described in terms of displacement, distance, velocity, acceleration, speed, and frame of reference to an o ...

, and that polarization consisted of a resolution of rectilinear propagation

Rectilinear propagation describes the tendency of electromagnetic waves (light) to travel in a straight line. Light does not deviate when travelling through a homogeneous medium, which has the same refractive index throughout; otherwise, light exp ...

into components at right angles to each other. The subsequent invention of the polariscope and discovery of Rotary polarization are due to Arago. He invented the first polarization filter in 1812. He was the first to perform a polarimetric observation of a comet when he discovered polarized light from the tail of the Great Comet of 1819.

The general idea of the experimental determination of the velocity of light

The speed of light in vacuum, commonly denoted , is a universal physical constant exactly equal to ). It is exact because, by international agreement, a metre is defined as the length of the path travelled by light in vacuum during a time i ...

in the manner subsequently effected by Hippolyte Fizeau

Armand Hippolyte Louis Fizeau (; 23 September 1819 – 18 September 1896) was a French physicist who, in 1849, measured the speed of light to within 5% accuracy. In 1851, he measured the speed of light in moving water in an experiment known as t ...

and Léon Foucault

Jean Bernard Léon Foucault (, ; ; 18 September 1819 – 11 February 1868) was a French physicist best known for his demonstration of the Foucault pendulum, a device demonstrating the effect of Earth's rotation. He also made an early measuremen ...

was suggested by Arago in 1838, but his failing eyesight prevented his arranging the details or making the experiments.

Arago's fame as an experimenter and discoverer rests mainly on his contributions to magnetism in the co-discovery with Léon Foucault

Jean Bernard Léon Foucault (, ; ; 18 September 1819 – 11 February 1868) was a French physicist best known for his demonstration of the Foucault pendulum, a device demonstrating the effect of Earth's rotation. He also made an early measuremen ...

of eddy currents, and still more to optics

Optics is the branch of physics that studies the behaviour and properties of light, including its interactions with matter and the construction of optical instruments, instruments that use or Photodetector, detect it. Optics usually describes t ...

. He showed that a magnetic needle, made to oscillate over nonferrous surfaces, such as water, glass, copper, etc., falls more rapidly in the extent of its oscillations according as it is more or less approached to the surface. This discovery, which earned him the Copley Medal

The Copley Medal is the most prestigious award of the Royal Society of the United Kingdom, conferred "for sustained, outstanding achievements in any field of science". The award alternates between the physical sciences or mathematics and the bio ...

of the Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

in 1825, was followed by another, that a rotating plate of copper tends to communicate its motion to a magnetic needle suspended over it, which he called "magnetism of rotation" but (after Faraday's explanation of 1832) is now known as eddy current. Arago is also fairly entitled to be regarded as having proved the long-suspected connexion between the aurora borealis

An aurora ( aurorae or auroras),

also commonly known as the northern lights (aurora borealis) or southern lights (aurora australis), is a natural light display in Earth's sky, predominantly observed in high-latitude regions (around the Arc ...

and the variations of the magnetic elements. In 1827 he was elected an associated member of the Royal Institute of the Netherlands, when that institute became the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences

The Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences (, KNAW) is an organization dedicated to the advancement of science and literature in the Netherlands. The academy is housed in the Trippenhuis in Amsterdam.

In addition to various advisory a ...

in 1851, he became foreign member. In 1828, he was elected a foreign member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences

The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences () is one of the Swedish Royal Academies, royal academies of Sweden. Founded on 2 June 1739, it is an independent, non-governmental scientific organization that takes special responsibility for promoting nat ...

.

In optics, Arago not only made important optical discoveries on his own, but is credited with stimulating the genius of Jean-Augustin Fresnel, with whose history, as well as that of Étienne-Louis Malus and Thomas Young, this part of his life is closely interwoven.

Shortly after the beginning of the 19th century the labours of at least three philosophers were shaping the doctrine of the undulatory, or wave, theory of light. Fresnel's arguments in favour of that theory found little favour with Laplace, Poisson and Biot, the champions of the emission theory; but they were ardently espoused by Humboldt and by Arago, who had been appointed by the Academy to report on the paper. This was the foundation of an intimate friendship between Arago and Fresnel, and of a determination to carry on together further fundamental laws of the polarization of light known by their means. As a result of this work, Arago constructed a polariscope, which he used for some interesting observations on the polarization of the light of the sky. He also discovered the power of rotatory polarization exhibited by quartz

Quartz is a hard, crystalline mineral composed of silica (silicon dioxide). The Atom, atoms are linked in a continuous framework of SiO4 silicon–oxygen Tetrahedral molecular geometry, tetrahedra, with each oxygen being shared between two tet ...

.

Among Arago's many contributions to the support of the undulatory hypothesis, comes the ''experimentum crucis'' which he proposed to carry out for measuring directly the velocity of light in air and in water and glass. On the emission theory the velocity should be accelerated by an increase of density in the medium; on the wave theory, it should be retarded. In 1838 he communicated to the Academy the details of his apparatus, which utilized the relaying mirrors employed by Charles Wheatstone

Sir Charles Wheatstone (; 6 February 1802 – 19 October 1875) was an English physicist and inventor best known for his contributions to the development of the Wheatstone bridge, originally invented by Samuel Hunter Christie, which is used to m ...

in 1835 for measuring the velocity of the electric discharge; but owing to the great care required in the carrying out of the project, and to the interruption to his labours caused by the revolution of 1848, it was the spring of 1850 before he was ready to put his idea to the test; and then his eyesight suddenly gave way. Before his death, however, the retardation of light in denser media was demonstrated by the experiments of H. L. Fizeau and B. L. Foucault, which, with improvements in detail, were based on the plan proposed by him.

Politics and legacy

In 1830, Arago, who always professed liberal opinions of the republican type, was elected a member of the chamber of deputies for the

In 1830, Arago, who always professed liberal opinions of the republican type, was elected a member of the chamber of deputies for the Pyrénées-Orientales

Pyrénées-Orientales (; ; ; ), also known as Northern Catalonia, is a departments of France, department of the Regions of France, region of Occitania (administrative region), Occitania, Southern France, adjacent to the northern Spain, Spanish ...

''département

In the administrative divisions of France, the department (, ) is one of the three levels of government under the national level (" territorial collectivities"), between the administrative regions and the communes. There are a total of 101 ...

'', and he employed his talents of eloquence and scientific knowledge in all questions connected with public education, the rewards of inventors, and the encouragement of the mechanical and practical sciences. Many of the most creditable national enterprises, dating from this period, are due to his advocacy – such as the reward to Louis Daguerre

Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre ( ; ; 18 November 1787 – 10 July 1851) was a France, French scientist, artist and photographer, recognized for his invention of the eponymous daguerreotype process of photography. He became known as one of th ...

for the invention of photography, the grant for the publication of the works of Fermat

Pierre de Fermat (; ; 17 August 1601 – 12 January 1665) was a French mathematician who is given credit for early developments that led to infinitesimal calculus, including his technique of adequality. In particular, he is recognized for his d ...

and Laplace

Pierre-Simon, Marquis de Laplace (; ; 23 March 1749 – 5 March 1827) was a French polymath, a scholar whose work has been instrumental in the fields of physics, astronomy, mathematics, engineering, statistics, and philosophy. He summariz ...

, the acquisition of the museum of Cluny, the development of railways and electric telegraphs, the improvement of the reneile. In 1839, Arago reported the invention of photography to stunned listeners of a joint meeting of the academies of Arts and Sciences.

In 1830, Arago also was appointed director of the Observatory, and as a member of the chamber of deputies he was able to obtain grants of money for rebuilding it in part, and for the addition of magnificent instruments. In the same year, too, he was chosen perpetual secretary of the Academy of Sciences, the place of Joseph Fourier

Jean-Baptiste Joseph Fourier (; ; 21 March 1768 – 16 May 1830) was a French mathematician and physicist born in Auxerre, Burgundy and best known for initiating the investigation of Fourier series, which eventually developed into Fourier analys ...

. Arago threw himself into its service, and by his faculty of making friends he gained at once for it and for himself a worldwide reputation. As perpetual secretary it was his duty to pronounce historical eulogies on deceased members; and for this duty his rapidity and facility of thought, and his happy piquancy of style, and his extensive knowledge peculiarly adapted him. He was elected a Foreign Honorary Member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences

The American Academy of Arts and Sciences (The Academy) is one of the oldest learned societies in the United States. It was founded in 1780 during the American Revolution by John Adams, John Hancock, James Bowdoin, Andrew Oliver, and other ...

in 1832.

In 1834, Arago again visited Scotland

Scotland is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It contains nearly one-third of the United Kingdom's land area, consisting of the northern part of the island of Great Britain and more than 790 adjac ...

, to attend the meeting of the British Association

The British Science Association (BSA) is a charity and learned society founded in 1831 to aid in the promotion and development of science. Until 2009 it was known as the British Association for the Advancement of Science (BA). The current Chief ...

at Edinburgh

Edinburgh is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 Council areas of Scotland, council areas. The city is located in southeast Scotland and is bounded to the north by the Firth of Forth and to the south by the Pentland Hills. Edinburgh ...

. From this time till 1848 he led a life of comparative quiet – although he continued to work within the Academy and the Observatory to produce a multitude of contributions to all departments of physical science – but on the fall of Louis-Philippe

Louis Philippe I (6 October 1773 – 26 August 1850), nicknamed the Citizen King, was King of the French from 1830 to 1848, the penultimate monarch of France, and the last French monarch to bear the title "King". He abdicated from his throne ...

he left his laboratory to join the Provisional Government (24 February 1848). He was entrusted with two important functions, that had never before been given to one person, viz. the ministry of marine and colonies (24 February 184811 May 1848) and ministry of war (5 April 184811 May 1848); in the former capacity he improved rations in the navy and abolished flogging. He also abolished political oaths of all kinds and, against an array of moneyed interests, succeeded in procuring the abolition of slavery

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the political movement to end slavery and liberate enslaved individuals around the world.

The first country to fully outlaw slavery was France in 1315, but it was later used in its colonies. T ...

in the French colonies.

On 10 May 1848, Arago was elected a member of the Executive Power Commission, a governing body of the French Republic. He was made President of the Executive Power Commission (11 May 1848) and served in this capacity as provisional head of state until 24 June 1848, when collective resignation of the commission was submitted to the National Constituent Assembly. At the beginning of May 1852, when the government of Louis Napoleon required an oath of allegiance from all its functionaries, Arago peremptorily refused, and sent in his resignation of his post as astronomer at the Bureau des Longitudes. This, however, the prince president declined to accept, and made "an exception in favour of a savant whose works had thrown lustre on France, and whose existence the government would regret to embitter."

Cape Gregory in Oregon

Oregon ( , ) is a U.S. state, state in the Pacific Northwest region of the United States. It is a part of the Western U.S., with the Columbia River delineating much of Oregon's northern boundary with Washington (state), Washington, while t ...

was named by Captain Cook

Captain James Cook (7 November 1728 – 14 February 1779) was a British Royal Navy officer, explorer, and cartographer famous for his three voyages of exploration to the Pacific and Southern Oceans, conducted between 1768 and 1779. He complet ...

on 12 March 1778 after Saint Gregory, the saint of that day; it was renamed Cape Arago after François Arago.

Last years

Arago remained a consistent republican to the end, and after the coup d'état of 1852, though suffering first fromdiabetes

Diabetes mellitus, commonly known as diabetes, is a group of common endocrine diseases characterized by sustained high blood sugar levels. Diabetes is due to either the pancreas not producing enough of the hormone insulin, or the cells of th ...

, then from Bright's disease

Bright's disease is a historical classification of kidney diseases that are described in modern medicine as acute or chronic nephritis. It was characterized by swelling and the presence of albumin in the urine. It was frequently accompanied ...

, complicated by dropsy, he resigned his post as astronomer rather than take the oath of allegiance

An oath of allegiance is an oath whereby a subject or citizen acknowledges a duty of allegiance and swears loyalty to a monarch or a country. In modern republics, oaths are sworn to the country in general, or to the country's constitution. For ...

. Napoleon III

Napoleon III (Charles-Louis Napoléon Bonaparte; 20 April 18089 January 1873) was President of France from 1848 to 1852 and then Emperor of the French from 1852 until his deposition in 1870. He was the first president, second emperor, and last ...

gave directions that the old man should be in no way disturbed, and should be left free to say and do what he liked. In the summer of 1853 Arago was advised by his physicians to try the effect of his native air, and he accordingly set out to the eastern Pyrenees

The Pyrenees are a mountain range straddling the border of France and Spain. They extend nearly from their union with the Cantabrian Mountains to Cap de Creus on the Mediterranean coast, reaching a maximum elevation of at the peak of Aneto. ...

, but this was ineffective and he died in Paris. His grave is at the famous Père Lachaise Cemetery

Père Lachaise Cemetery (, , formerly , ) is the largest cemetery in Paris, France, at . With more than 3.5 million visitors annually, it is the most visited necropolis in the world.

Buried at Père Lachaise are many famous figures in the ...

in Paris. Arago was an atheist.

Named after Arago

* The study association for Applied Physics at the

* The study association for Applied Physics at the University of Twente

The University of Twente ( ; Abbreviation, abbr. ) is a Public university, public technical university located in Enschede, Netherlands.

The university has been placed in the top 170 universities in the world by multiple central ranking tables. ...

was named after Arago.

* His name is one of the 72 names inscribed on the Eiffel Tower.

* The outer main-belt asteroid 1005 Arago, an inner ring of Neptune, the lunar crater '' Arago'' as well as the Martian crater '' Arago'' were also named in his honor.

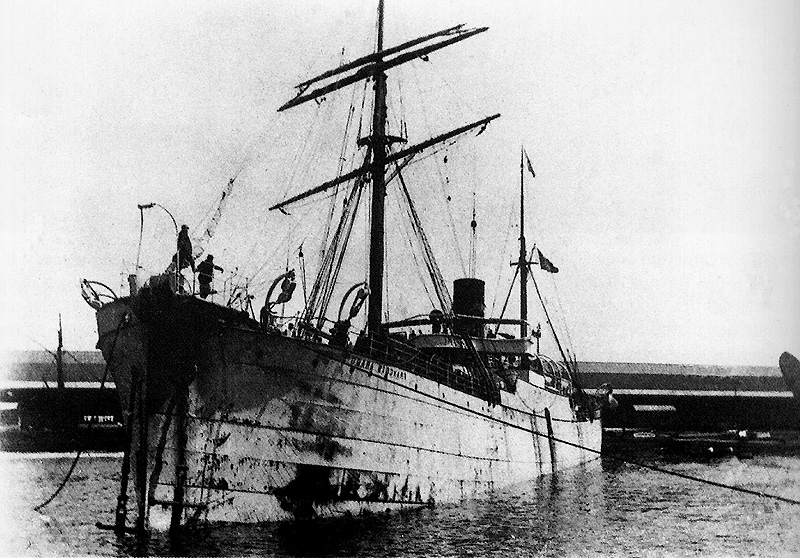

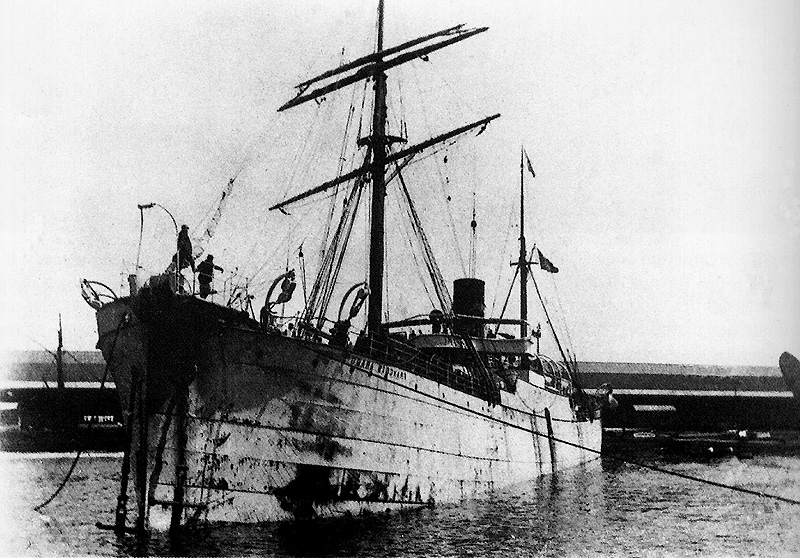

* Two French cable ships were named after him, the ''François Arago'' of 1882 and the ''Arago'' of 1914/1931.

* Boulevard Arago, Paris

Honours

* : Officer of the Order of Leopold. * 1842 PrussianPour le Mérite

The (; , ), also informally known as the ''Blue Max'' () after German WWI flying ace Max Immelmann, is an order of merit established in 1740 by King Frederick II of Prussia. Separated into two classes, each with their own designs, the was ...

for Sciences and Arts.

Publications

Arago's works were published after his death under the direction J. A. Barral, in 17 vols., 8vo, 1854–1862 (); also separately his ''Astronomie populaire'', in 4 vols.; ''Notices biographiques'', in 3 vols.; ''Indices scientifiques'', in 5 vols.; ''Voyages scientifiques'', in 1 vol.; ''Grimoires scientifiques'', in 2 vols.; ''Mélanges'', in I vol.; and ''Tables analytiques et documents importants (with portrait)'', in 1 vol. English translations of the following portions of Arago's works have appeared: * ''Treatise on Comets'', by C. Gold, C.B. (London, 1833); also translated W. H. Smyth and Grant (London, 1861) *''Euloge of James Watt'', by Muirhead (London, 1839); also translated, with notes, by Brougham *''Popular Lectures on Astronomy'', by Walter Kelly and Rev. L. Tomlinson (London, 1854); also translated by Dr W. H. Smyth and Prof. R. Grant, 2 vols. (London, 1855) *''Arago's Autography'', translated by the Rev. Baden Powell (London, 1855, 58) *''Arago's Meteorological Essays'', with introduction byAlexander von Humboldt

Friedrich Wilhelm Heinrich Alexander von Humboldt (14 September 1769 – 6 May 1859) was a German polymath, geographer, natural history, naturalist, List of explorers, explorer, and proponent of Romanticism, Romantic philosophy and Romanticism ...

, translated under the supervision of Colonel Edward Sabine

Sir Edward Sabine (; 14 October 1788 – 26 June 1883) was an Irish physicist, geodesist,astronomer, geophysicist, ornithologist, polar explorer, soldier, and the 30th president of the Royal Society.

He led the effort to establish a system o ...

(London, 1855)

*

See also

* The works of Antonin Mercié *History of the metre

During the French Revolution, the traditional units of measure were to be replaced by consistent measures based on natural phenomena. As a base unit of length, scientists had favoured the seconds pendulum (a pendulum with a half-period of ...

*Seconds pendulum

A seconds pendulum is a pendulum whose period is precisely two seconds; one second for a swing in one direction and one second for the return swing, a frequency of 0.5 Hz.

Principles

A pendulum is a weight suspended from a pivot so tha ...

References

Further reading

* * * * Walter Baily,A Mode of producing Arago's Rotation

'. 28 June 1879. (Philosophical magazine: a journal of theoretical, experimental and applied physics. Taylor & Francis., 1879)

External links

* * *''Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society'', 1854, volume 14, page 102 *

misused in ''The Da Vinci Code'' is in fact an art project by the Dutch artist Jan Dibbets (1941) made in 1987 as a tribute to the astronomer François Arago (1786–1853)

S.V. Arago The study association for applied physics

(Dutch) at the

University of Twente

The University of Twente ( ; Abbreviation, abbr. ) is a Public university, public technical university located in Enschede, Netherlands.

The university has been placed in the top 170 universities in the world by multiple central ranking tables. ...

is named after François Arago.

Portrait of Francois F. Arago from the Lick Observatory Records Digital Archive, UC Santa Cruz Library's Digital Collections

« Arago et l’Observatoire de Paris »

{{DEFAULTSORT:Arago, Francois 1786 births 1853 deaths 19th-century heads of state of France People from Pyrénées-Orientales Politicians from Occitania (administrative region) Moderate Republicans (France) Heads of state of France Ministers of war of France Ministers of marine and the colonies Members of the 2nd Chamber of Deputies of the July Monarchy Members of the 3rd Chamber of Deputies of the July Monarchy Members of the 4th Chamber of Deputies of the July Monarchy Members of the 5th Chamber of Deputies of the July Monarchy Members of the 6th Chamber of Deputies of the July Monarchy Members of the 7th Chamber of Deputies of the July Monarchy Members of the 1848 Constituent Assembly Members of the National Legislative Assembly of the French Second Republic 19th-century French mathematicians Scientists from Catalonia 19th-century French astronomers French atheists French Freemasons 19th-century French physicists Vision scientists French people of the Revolutions of 1848 École Polytechnique alumni Members of the French Academy of Sciences Honorary Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh Honorary members of the Saint Petersburg Academy of Sciences Members of the Royal Academy of Belgium Members of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences Members of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences Officers of the French Academy of Sciences Fellows of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences Foreign members of the Royal Society Recipients of the Copley Medal Recipients of the Pour le Mérite (civil class) Burials at Père Lachaise Cemetery 18th-century atheists 19th-century atheists Members of the Göttingen Academy of Sciences and Humanities French geodesists