Elk Haus NÖ on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The elk (: ''elk'' or ''elks''; ''Cervus canadensis'') or wapiti, is the second largest species within the

Members of the

Members of the

File:Audubon-eastern-elk.jpg, Artist's depiction of

Elk have thick bodies with slender legs and short tails. They have a shoulder height of with a nose-to-tail length of . Males are larger and weigh while females weigh . The largest of the subspecies is the Roosevelt elk (''C. c. roosevelti''), found west of the

Elk have thick bodies with slender legs and short tails. They have a shoulder height of with a nose-to-tail length of . Males are larger and weigh while females weigh . The largest of the subspecies is the Roosevelt elk (''C. c. roosevelti''), found west of the  During the fall, elk grow a thicker coat of hair, which helps to insulate them during the winter. Both male and female North American elk grow thin neck manes; females of other subspecies may not. By early summer, the heavy winter coat has been shed. Elk are known to rub against trees and other objects to help remove hair from their bodies. All elk have small and clearly defined rump patches with short tails. They have different coloration based on the seasons and types of habitats, with gray or lighter coloration prevalent in the winter and a more reddish, darker coat in the summer. Subspecies living in arid climates tend to have lighter colored coats than do those living in forests. Most have lighter yellow-brown to orange-brown coats in contrast to dark brown hair on the head, neck, and legs during the summer. Forest-adapted Manchurian and Alaskan wapitis have red or reddish-brown coats with less contrast between the body coat and the rest of the body during the summer months. Calves are born spotted, as is common with many deer species, and lose them by the end of summer. Adult Manchurian wapiti may retain a few orange spots on the back of their summer coats until they are older. This characteristic has also been observed in the forest-adapted European red deer.

During the fall, elk grow a thicker coat of hair, which helps to insulate them during the winter. Both male and female North American elk grow thin neck manes; females of other subspecies may not. By early summer, the heavy winter coat has been shed. Elk are known to rub against trees and other objects to help remove hair from their bodies. All elk have small and clearly defined rump patches with short tails. They have different coloration based on the seasons and types of habitats, with gray or lighter coloration prevalent in the winter and a more reddish, darker coat in the summer. Subspecies living in arid climates tend to have lighter colored coats than do those living in forests. Most have lighter yellow-brown to orange-brown coats in contrast to dark brown hair on the head, neck, and legs during the summer. Forest-adapted Manchurian and Alaskan wapitis have red or reddish-brown coats with less contrast between the body coat and the rest of the body during the summer months. Calves are born spotted, as is common with many deer species, and lose them by the end of summer. Adult Manchurian wapiti may retain a few orange spots on the back of their summer coats until they are older. This characteristic has also been observed in the forest-adapted European red deer.

A bull interacts with cows in his harem in two ways: herding and courtship. When a female wanders too far away from the harem's range, the male will rush ahead of her, block her path and aggressively rush her back to the harem. Herding behavior is accompanied by a stretched out and lowered neck and the antlers laid back. A bull may get violent and hit the cow with his antlers. During courtship, the bull is more peaceful and approaches her with his head and antlers raised. The male signals his intention to test the female for sexual receptivity by flicking his tongue. If not ready, a cow will lower her head and weave from side to side while opening and closing her mouth. The bull will stop in response in order not to scare her. Otherwise, the bull will copiously lick the female and then mount her.

Younger, less dominant bulls, known as "spike bulls", because their antlers have not yet forked, will harass unguarded cows. These bulls are impatient and will not perform any courtship rituals and will continue to pursue a female even when she signals him to stop. As such, they are less reproductively successful, and a cow may stay close to the big bull to avoid harassment. Dominant bulls are intolerant of spike bulls and will chase them away from their harems.

The

A bull interacts with cows in his harem in two ways: herding and courtship. When a female wanders too far away from the harem's range, the male will rush ahead of her, block her path and aggressively rush her back to the harem. Herding behavior is accompanied by a stretched out and lowered neck and the antlers laid back. A bull may get violent and hit the cow with his antlers. During courtship, the bull is more peaceful and approaches her with his head and antlers raised. The male signals his intention to test the female for sexual receptivity by flicking his tongue. If not ready, a cow will lower her head and weave from side to side while opening and closing her mouth. The bull will stop in response in order not to scare her. Otherwise, the bull will copiously lick the female and then mount her.

Younger, less dominant bulls, known as "spike bulls", because their antlers have not yet forked, will harass unguarded cows. These bulls are impatient and will not perform any courtship rituals and will continue to pursue a female even when she signals him to stop. As such, they are less reproductively successful, and a cow may stay close to the big bull to avoid harassment. Dominant bulls are intolerant of spike bulls and will chase them away from their harems.

The

As is true for many species of deer, especially those in mountainous regions, elk

As is true for many species of deer, especially those in mountainous regions, elk

Elk are ruminants and therefore have four-chambered stomachs. Unlike white-tailed deer and moose, which are chiefly browsers, elk are similar to

Elk are ruminants and therefore have four-chambered stomachs. Unlike white-tailed deer and moose, which are chiefly browsers, elk are similar to

The elk ranges from central Asia through to Siberia and east Asia and in North America. They can be found in open deciduous woodlands, boreal forests, upland moors, mountainous areas and grasslands. The

The elk ranges from central Asia through to Siberia and east Asia and in North America. They can be found in open deciduous woodlands, boreal forests, upland moors, mountainous areas and grasslands. The

As of 2014, population figures for all North American elk subspecies were around one million. Prior to the European colonization of North America, there were an estimated 10 million on the continent.

There are many past and ongoing examples of reintroduction into areas of the US. Elk were reintroduced in

As of 2014, population figures for all North American elk subspecies were around one million. Prior to the European colonization of North America, there were an estimated 10 million on the continent.

There are many past and ongoing examples of reintroduction into areas of the US. Elk were reintroduced in

Elk have played an important role in the cultural history of a number of peoples.

Elk have played an important role in the cultural history of a number of peoples.

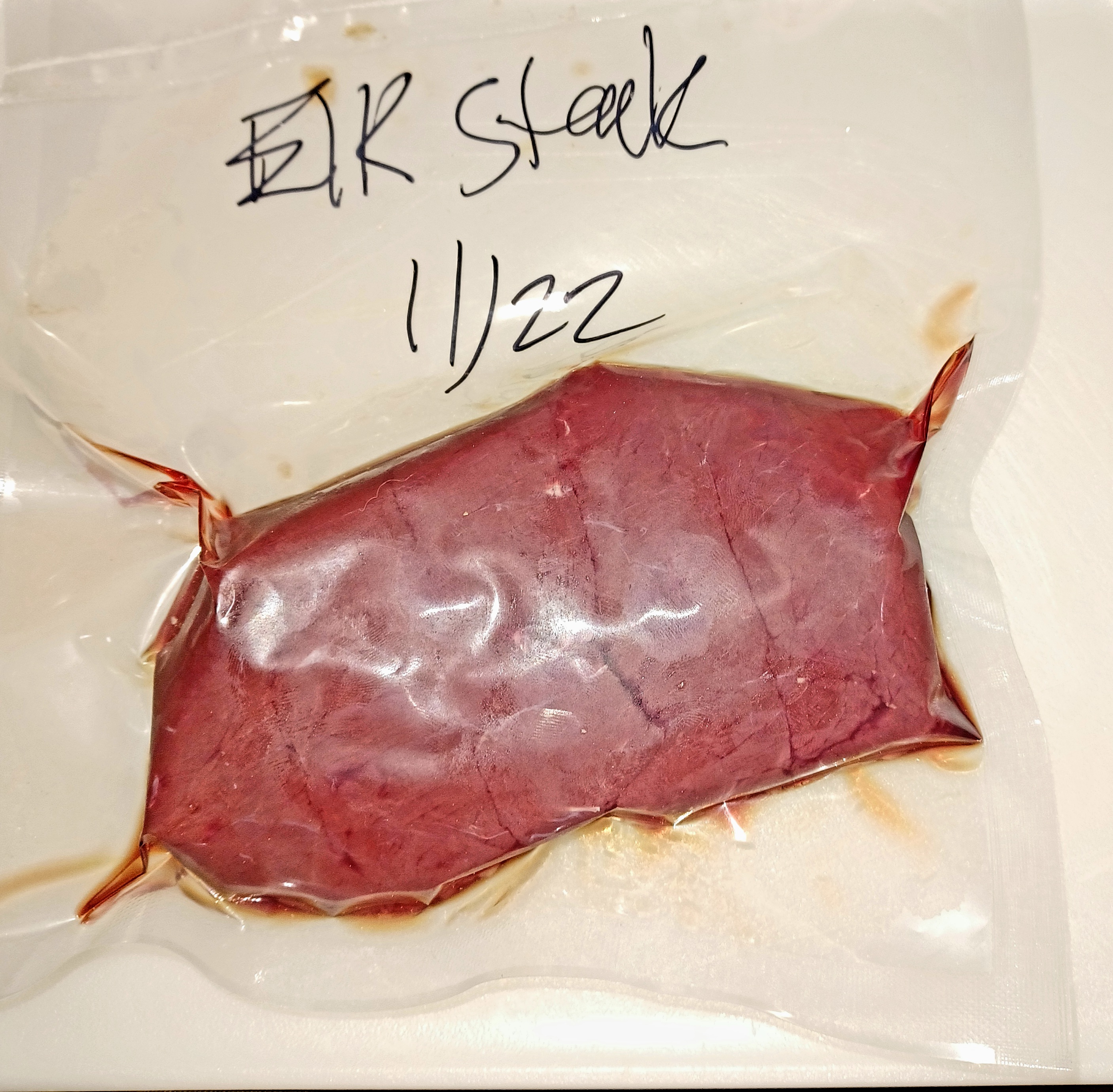

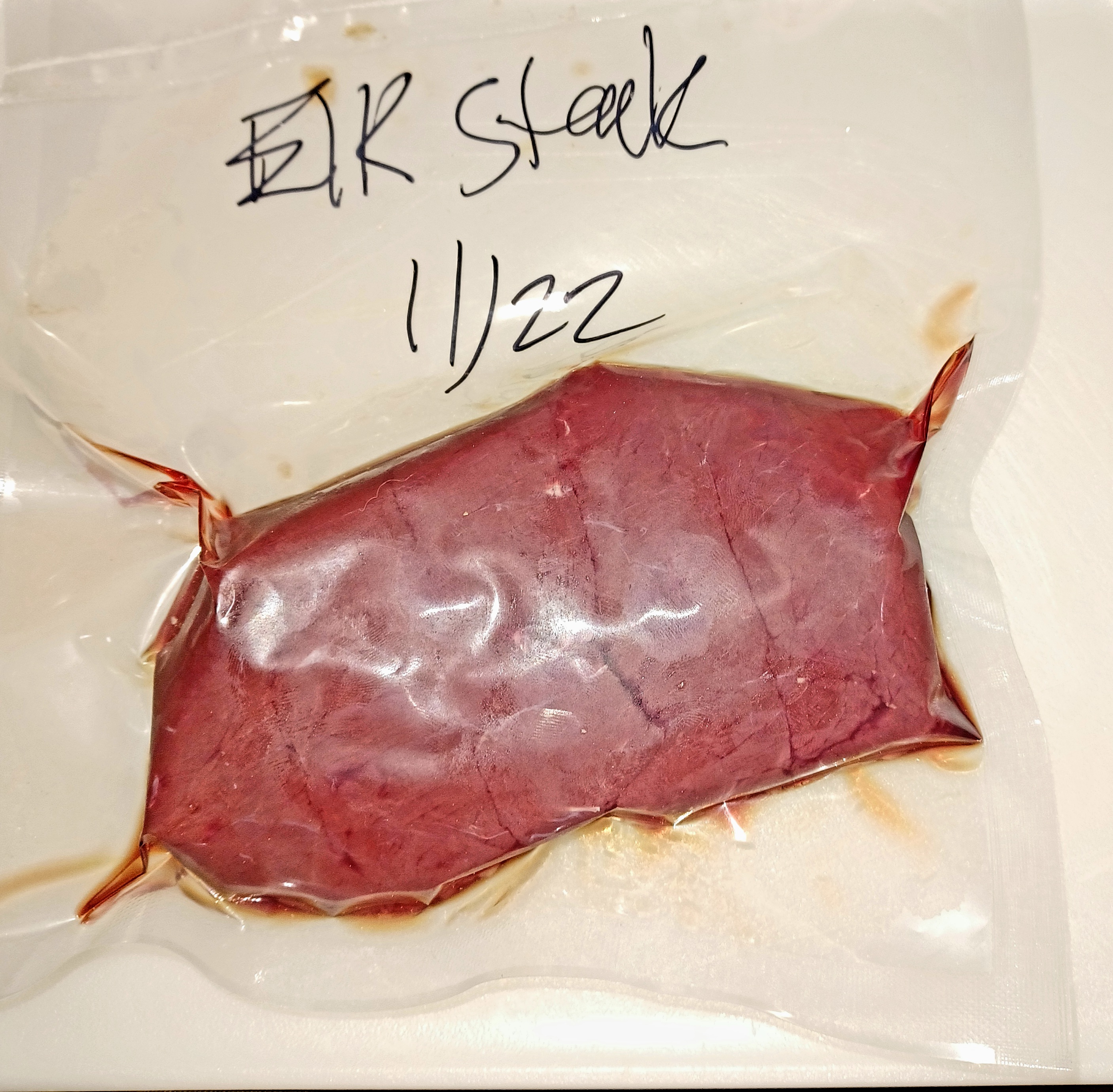

Although the 2006 National Survey from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service does not provide breakdown figures for each game species, hunting of wild elk is most likely the primary economic impact.

While elk are not generally harvested for meat production on a large scale, some restaurants offer the meat as a specialty item and it is also available in some grocery stores. The meat is higher in

Although the 2006 National Survey from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service does not provide breakdown figures for each game species, hunting of wild elk is most likely the primary economic impact.

While elk are not generally harvested for meat production on a large scale, some restaurants offer the meat as a specialty item and it is also available in some grocery stores. The meat is higher in

Arizona Elk

Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation

Smithsonian Institution - North American Mammals: ''Cervus'' (''elaphus'') ''canadensis''

{{Taxonbar, from=Q180404 Red deer Extant Pleistocene first appearances Fauna of Central Asia Fauna of East Asia Fauna of Siberia Herbivorous mammals Fauna of the Holarctic realm Mammals described in 1777 Mammals of Canada Mammals of the United States Mammals of East Asia Taxa named by Johann Christian Polycarp Erxleben National symbols of Djibouti

deer

A deer (: deer) or true deer is a hoofed ruminant ungulate of the family Cervidae (informally the deer family). Cervidae is divided into subfamilies Cervinae (which includes, among others, muntjac, elk (wapiti), red deer, and fallow deer) ...

family, Cervidae

A deer (: deer) or true deer is a hoofed ruminant ungulate of the family Cervidae (informally the deer family). Cervidae is divided into subfamilies Cervinae (which includes, among others, muntjac, elk (wapiti), red deer, and fallow deer) a ...

, and one of the largest terrestrial mammal

A mammal () is a vertebrate animal of the Class (biology), class Mammalia (). Mammals are characterised by the presence of milk-producing mammary glands for feeding their young, a broad neocortex region of the brain, fur or hair, and three ...

s in its native range of North America and Central and East Asia

East Asia is a geocultural region of Asia. It includes China, Japan, Mongolia, North Korea, South Korea, and Taiwan, plus two special administrative regions of China, Hong Kong and Macau. The economies of Economy of China, China, Economy of Ja ...

. The word "elk" originally referred to the European variety of the moose

The moose (: 'moose'; used in North America) or elk (: 'elk' or 'elks'; used in Eurasia) (''Alces alces'') is the world's tallest, largest and heaviest extant species of deer and the only species in the genus ''Alces''. It is also the tal ...

, ''Alces alces'', but was transferred to ''Cervus canadensis'' by North American colonists.

The name "wapiti" is derived from a Shawnee

The Shawnee ( ) are a Native American people of the Northeastern Woodlands. Their language, Shawnee, is an Algonquian language.

Their precontact homeland was likely centered in southern Ohio. In the 17th century, they dispersed through Ohi ...

and Cree

The Cree, or nehinaw (, ), are a Indigenous peoples of the Americas, North American Indigenous people, numbering more than 350,000 in Canada, where they form one of the country's largest First Nations in Canada, First Nations. They live prim ...

word meaning "white rump", after the distinctive light fur around the tail region which the animals may fluff-up or raise to signal their agitation or distress to one another, when fleeing perceived threats, or among males courting females and sparring

Sparring is a form of training common to many combat sports. It can encompass a range of activities and techniques such as punching, kicking, grappling, throwing, wrestling or submission work dependent on style. Although the precise form varies, ...

for dominance. A similar trait is seen in other artiodactyl

Artiodactyls are placental mammals belonging to the order Artiodactyla ( , ). Typically, they are ungulates which bear weight equally on two (an even number) of their five toes (the third and fourth, often in the form of a hoof). The other t ...

species, like the bighorn sheep

The bighorn sheep (''Ovis canadensis'') is a species of Ovis, sheep native to North America. It is named for its large Horn (anatomy), horns. A pair of horns may weigh up to ; the sheep typically weigh up to . Recent genetic testing indicates th ...

, pronghorn

The pronghorn (, ) (''Antilocapra americana'') is a species of artiodactyl (even-toed, hoofed) mammal indigenous to interior western and central North America. Though not an antelope, it is known colloquially in North America as the American ante ...

and the white-tailed deer

The white-tailed deer (''Odocoileus virginianus''), also known Common name, commonly as the whitetail and the Virginia deer, is a medium-sized species of deer native to North America, North, Central America, Central and South America. It is the ...

, to varying degrees.

Elk dwell in open forest and forest-edge habitats, grazing on grasses and sedges and browsing higher-growing plants, leaves, twigs and bark. Male elk have large, blood- and nerve-filled antler

Antlers are extensions of an animal's skull found in members of the Cervidae (deer) Family (biology), family. Antlers are a single structure composed of bone, cartilage, fibrous tissue, skin, nerves, and blood vessels. They are generally fo ...

s, which they routinely shed

A shed is typically a simple, single-storey (though some sheds may have two or more stories and or a loft) roofed structure, often used for storage, for hobby, hobbies, or as a workshop, and typically serving as outbuilding, such as in a bac ...

each year as the weather warms. Males also engage in ritualized mating behaviors during the mating season

Seasonal breeders are animal species that successfully mate only during certain times of the year. These times of year allow for the optimization of survival of young due to factors such as ambient temperature, food and water availability, and ch ...

, including posturing to attract females, antler-wrestling (sparring), and ''bugling'', a loud series of throaty whistles, bellows, screams, and other vocalizations that establish dominance over other males and aim to attract females.

Elk were long believed to belong to a subspecies

In Taxonomy (biology), biological classification, subspecies (: subspecies) is a rank below species, used for populations that live in different areas and vary in size, shape, or other physical characteristics (Morphology (biology), morpholog ...

of the European red deer

The red deer (''Cervus elaphus'') is one of the largest deer species. A male red deer is called a stag or Hart (deer), hart, and a female is called a doe or hind. The red deer inhabits most of Europe, the Caucasus Mountains region, Anatolia, Ir ...

(''Cervus elaphus''), but evidence from many mitochondrial DNA

Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA and mDNA) is the DNA located in the mitochondrion, mitochondria organelles in a eukaryotic cell that converts chemical energy from food into adenosine triphosphate (ATP). Mitochondrial DNA is a small portion of the D ...

genetic studies, beginning in 1998, shows that the two are distinct species

A species () is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of the appropriate sexes or mating types can produce fertile offspring, typically by sexual reproduction. It is the basic unit of Taxonomy (biology), ...

. The elk's wider rump-patch and paler-hued antlers are key morphological differences that distinguish ''C. canadensis'' from ''C. elaphus''. Although it is currently only native to North America, Central, East

East is one of the four cardinal directions or points of the compass. It is the opposite direction from west and is the direction from which the Sun rises on the Earth.

Etymology

As in other languages, the word is formed from the fact that ea ...

and North Asia

North Asia or Northern Asia () is the northern region of Asia, which is defined in geography, geographical terms and consists of three federal districts of Russia: Ural Federal District, Ural, Siberian Federal District, Siberian, and the Far E ...

, elk once had a much wider distribution in the past; prehistoric populations were present across Eurasia

Eurasia ( , ) is a continental area on Earth, comprising all of Europe and Asia. According to some geographers, Physical geography, physiographically, Eurasia is a single supercontinent. The concept of Europe and Asia as distinct continents d ...

and into Western Europe

Western Europe is the western region of Europe. The region's extent varies depending on context.

The concept of "the West" appeared in Europe in juxtaposition to "the East" and originally applied to the Western half of the ancient Mediterranean ...

during the Late Pleistocene

The Late Pleistocene is an unofficial Age (geology), age in the international geologic timescale in chronostratigraphy, also known as the Upper Pleistocene from a Stratigraphy, stratigraphic perspective. It is intended to be the fourth division ...

, surviving into the early Holocene

The Holocene () is the current geologic time scale, geological epoch, beginning approximately 11,700 years ago. It follows the Last Glacial Period, which concluded with the Holocene glacial retreat. The Holocene and the preceding Pleistocene to ...

in Southern Sweden and the Alps

The Alps () are some of the highest and most extensive mountain ranges in Europe, stretching approximately across eight Alpine countries (from west to east): Monaco, France, Switzerland, Italy, Liechtenstein, Germany, Austria and Slovenia.

...

. The now-extinct North American Merriam's elk

The Merriam's elk (''Cervus canadensis merriami'') is an extinct subspecies of elk once found in the arid lands of the southwestern United States (in Arizona, New Mexico and Texas), as well as in Mexico. From the first New World arrival of Europ ...

subspecies (''Cervus canadensis merriami'') once ranged south into Mexico

Mexico, officially the United Mexican States, is a country in North America. It is the northernmost country in Latin America, and borders the United States to the north, and Guatemala and Belize to the southeast; while having maritime boundar ...

. The wapiti has also successfully adapted

In biology, adaptation has three related meanings. Firstly, it is the dynamic evolutionary process of natural selection that fits organisms to their environment, enhancing their evolutionary fitness. Secondly, it is a state reached by the p ...

to countries outside of its natural range where it has been introduced, including Argentina

Argentina, officially the Argentine Republic, is a country in the southern half of South America. It covers an area of , making it the List of South American countries by area, second-largest country in South America after Brazil, the fourt ...

and New Zealand

New Zealand () is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and List of islands of New Zealand, over 600 smaller islands. It is the List of isla ...

; the animal's adaptability in these areas may, in fact, be so successful as to threaten the sensitive endemic

Endemism is the state of a species being found only in a single defined geographic location, such as an island, state, nation, country or other defined zone; organisms that are indigenous to a place are not endemic to it if they are also foun ...

ecosystems and species it encounters.

As a member of the Artiodactyla order (and distant relative of the Bovidae

The Bovidae comprise the family (biology), biological family of cloven-hoofed, ruminant mammals that includes Bos, cattle, bison, Bubalina, buffalo, antelopes (including Caprinae, goat-antelopes), Ovis, sheep and Capra (genus), goats. A member o ...

), elk are susceptible to several infectious disease

An infection is the invasion of tissue (biology), tissues by pathogens, their multiplication, and the reaction of host (biology), host tissues to the infectious agent and the toxins they produce. An infectious disease, also known as a transmis ...

s which can be transmitted to or from domesticated livestock

Livestock are the Domestication, domesticated animals that are raised in an Agriculture, agricultural setting to provide labour and produce diversified products for consumption such as meat, Egg as food, eggs, milk, fur, leather, and wool. The t ...

. Efforts to eliminate infectious diseases from elk populations, primarily by vaccination

Vaccination is the administration of a vaccine to help the immune system develop immunity from a disease. Vaccines contain a microorganism or virus in a weakened, live or killed state, or proteins or toxins from the organism. In stimulating ...

, have had mixed success. Some cultures revere the elk as having spiritual significance. Antlers and velvet are used in traditional medicine

Traditional medicine (also known as indigenous medicine or folk medicine) refers to the knowledge, skills, and practices rooted in the cultural beliefs of various societies, especially Indigenous groups, used for maintaining health and treatin ...

s in parts of Asia; the production of ground antler and velvet supplements is also a thriving naturopathic

Naturopathy, or naturopathic medicine, is a form of alternative medicine. A wide array of practices branded as "natural", "non-invasive", or promoting "self-healing" are employed by its practitioners, who are known as naturopaths. Difficult ...

industry in several countries, including the United States, China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. With population of China, a population exceeding 1.4 billion, it is the list of countries by population (United Nations), second-most populous country after ...

and Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its Provinces and territories of Canada, ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, making it the world's List of coun ...

. The elk is hunted as a game species, and their meat is lean and higher in protein

Proteins are large biomolecules and macromolecules that comprise one or more long chains of amino acid residue (biochemistry), residues. Proteins perform a vast array of functions within organisms, including Enzyme catalysis, catalysing metab ...

than beef

Beef is the culinary name for meat from cattle (''Bos taurus''). Beef can be prepared in various ways; Cut of beef, cuts are often used for steak, which can be cooked to varying degrees of doneness, while trimmings are often Ground beef, grou ...

or chicken

The chicken (''Gallus gallus domesticus'') is a domesticated subspecies of the red junglefowl (''Gallus gallus''), originally native to Southeast Asia. It was first domesticated around 8,000 years ago and is now one of the most common and w ...

.

Naming and etymology

By the 17th century, ''Alces alces'' (moose, called "elk" in Europe) had long beenextirpated

Local extinction, also extirpation, is the termination of a species (or other taxon) in a chosen geographic area of study, though it still exists elsewhere. Local extinctions are contrasted with global extinctions.

Local extinctions mark a chan ...

from the British Isles

The British Isles are an archipelago in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean off the north-western coast of continental Europe, consisting of the islands of Great Britain, Ireland, the Isle of Man, the Inner Hebrides, Inner and Outer Hebr ...

, and the meaning of the word "elk" to English-speakers became rather vague, acquiring a meaning similar to "large deer". The name ''wapiti'' is from the Shawnee

The Shawnee ( ) are a Native American people of the Northeastern Woodlands. Their language, Shawnee, is an Algonquian language.

Their precontact homeland was likely centered in southern Ohio. In the 17th century, they dispersed through Ohi ...

and Cree

The Cree, or nehinaw (, ), are a Indigenous peoples of the Americas, North American Indigenous people, numbering more than 350,000 in Canada, where they form one of the country's largest First Nations in Canada, First Nations. They live prim ...

word (in Cree syllabics

Cree syllabics are the versions of Canadian Aboriginal syllabics used to write Cree language, Cree dialects, including the original syllabics system created for Cree and Ojibwe language, Ojibwe. There are two main varieties of syllabics for Cre ...

: or ), meaning "white rump". There is a subspecies of wapiti in Mongolia

Mongolia is a landlocked country in East Asia, bordered by Russia to the north and China to the south and southeast. It covers an area of , with a population of 3.5 million, making it the world's List of countries and dependencies by po ...

called the Altai wapiti

The Altai wapiti, sometimes called the Altai elk, or simply the Altai Deer, is a subspecies of ''Cervus canadensis'' found in the forest hills of southern Siberia, northwestern Mongolia, and northern Xinjiang province of China

China, offi ...

(''Cervus canadensis sibiricus''), also known as the Altai maral.

According to the ''Oxford English Dictionary

The ''Oxford English Dictionary'' (''OED'') is the principal historical dictionary of the English language, published by Oxford University Press (OUP), a University of Oxford publishing house. The dictionary, which published its first editio ...

'', the etymology of the word "elk" is "of obscure history". In Classical Antiquity

Classical antiquity, also known as the classical era, classical period, classical age, or simply antiquity, is the period of cultural History of Europe, European history between the 8th century BC and the 5th century AD comprising the inter ...

, the European ''Alces alces'' was known as and , words probably borrowed from a Germanic language

The Germanic languages are a branch of the Indo-European language family spoken natively by a population of about 515 million people mainly in Europe, North America, Oceania, and Southern Africa. The most widely spoken Germanic language, ...

or another language of northern Europe. By the 8th century, during the Early Middle Ages

The Early Middle Ages (or early medieval period), sometimes controversially referred to as the Dark Ages (historiography), Dark Ages, is typically regarded by historians as lasting from the late 5th to the 10th century. They marked the start o ...

, the moose was known as derived from the Proto-Germanic

Proto-Germanic (abbreviated PGmc; also called Common Germanic) is the linguistic reconstruction, reconstructed proto-language of the Germanic languages, Germanic branch of the Indo-European languages.

Proto-Germanic eventually developed from ...

: ''*elho-'', ''*elhon-'' and possibly connected with the . Later, the species became known in Middle English

Middle English (abbreviated to ME) is a form of the English language that was spoken after the Norman Conquest of 1066, until the late 15th century. The English language underwent distinct variations and developments following the Old English pe ...

as ''elk'', ''elcke'', or ''elke'', appearing in the Latinized form ''alke'', with the spelling ''alce'' borrowed directly from . Noting that ''elk'' "is not the normal phonetic representative" of the Old English ''elch'', the ''Oxford English Dictionary'' derives ''elk'' from , itself from .

The American ''Cervus canadensis'' was recognized as a relative of the red deer (''Cervus elaphus'') of Europe, and so ''Cervus canadensis'' were referred to as "red deer". Richard Hakluyt

Richard Hakluyt (; 1553 – 23 November 1616) was an English writer. He is known for promoting the British colonization of the Americas, English colonization of North America through his works, notably ''Divers Voyages Touching the Discov ...

refers to North America as a "lande ... full of many beastes, as redd dere" in his 1584 '' Discourse Concerning Western Planting''. Similarly, John Smith's 1616 ''A Description of New England

''A Description of New England'' (in full: ''A description of New England, or, Observations and discoveries in the north of America in the year of Our Lord 1614, with the success of six ships that went the next year, 1615'') is a work written by ...

'' referred to red deer. Sir William Talbot's 1672 English translation of John Lederer

John Lederer was a 17th-century German physician and an explorer of the Appalachian Mountains. He and the members of his party became the first Europeans to crest the Blue Ridge Mountains (1669) and the first to see the Shenandoah Valley and the ...

's Latin ''Discoveries'' likewise called the species "red deer", but noted in parentheses

A bracket is either of two tall fore- or back-facing punctuation marks commonly used to isolate a segment of text or data from its surroundings. They come in four main pairs of shapes, as given in the box to the right, which also gives their n ...

that they were "for their unusual largeness improperly termed Elks by ignorant people". Both Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (, 1743July 4, 1826) was an American Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the third president of the United States from 1801 to 1809. He was the primary author of the United States Declaration of Indepe ...

's 1785 ''Notes on the State of Virginia

''Notes on the State of Virginia'' (1785) is a book written by the American statesman, philosopher, and planter Thomas Jefferson. He completed the first version in 1781 and updated and enlarged the book in 1782 and 1783. It originated in Jeffers ...

'' and David Bailie Warden

David Bailie Warden (1772-1845) was a republican insurgent in the Irish Rebellion of 1798 and, in later exile, a United States consul in Paris. While in American service Warden protested the corruption of diplomatic service by the "avaricious" s ...

's 1816 ''Statistical, Political, and Historical Account of the United States'' used "red deer" to refer to ''Cervus canadensis''.

Taxonomy

Members of the

Members of the genus

Genus (; : genera ) is a taxonomic rank above species and below family (taxonomy), family as used in the biological classification of extant taxon, living and fossil organisms as well as Virus classification#ICTV classification, viruses. In bino ...

''Cervus

''Cervus'' is a genus of deer that primarily are native to Eurasia, although one species occurs in northern Africa and another in North America. In addition to the species presently placed in this genus, it has included a whole range of other s ...

'' (and hence early relatives or possible ancestors of the elk) first appear in the fossil

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserve ...

record 25 million years ago, during the Oligocene

The Oligocene ( ) is a geologic epoch (geology), epoch of the Paleogene Geologic time scale, Period that extends from about 33.9 million to 23 million years before the present ( to ). As with other older geologic periods, the rock beds that defin ...

in Eurasia

Eurasia ( , ) is a continental area on Earth, comprising all of Europe and Asia. According to some geographers, Physical geography, physiographically, Eurasia is a single supercontinent. The concept of Europe and Asia as distinct continents d ...

, but do not appear in the North American fossil record until the early Miocene

The Miocene ( ) is the first epoch (geology), geological epoch of the Neogene Period and extends from about (Ma). The Miocene was named by Scottish geologist Charles Lyell; the name comes from the Greek words (', "less") and (', "new") and mea ...

. The extinct Irish elk

The Irish elk (''Megaloceros giganteus''), also called the giant deer or Irish deer, is an extinct species of deer in the genus '' Megaloceros'' and is one of the largest deer that ever lived. Its range extended across northern Eurasia during th ...

(''Megaloceros'') was not a member of the genus ''Cervus'' but rather the largest member of the wider deer family (Cervidae) known from the fossil record.

Until recently, red deer and elk were considered to be one species, ''Cervus elaphus'', with over a dozen subspecies. But mitochondria

A mitochondrion () is an organelle found in the cells of most eukaryotes, such as animals, plants and fungi. Mitochondria have a double membrane structure and use aerobic respiration to generate adenosine triphosphate (ATP), which is us ...

l DNA studies conducted in 2004 on hundreds of samples from red deer and elk subspecies and other species of the ''Cervus'' deer family, strongly indicate that elk, or wapiti, should be a distinct species, namely ''Cervus canadensis''. DNA evidence validates that elk are more closely related to Thorold's deer

Thorold's deer (''Cervus albirostris'')Pitraa, Fickela, Meijaard, Groves (2004). ''Evolution and phylogeny of old world deer.'' Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 33: 880–895. is a threatened species of deer found in the grassland, shrublan ...

(''C. albirostris'') and even sika deer

The sika deer (''Cervus nippon''), also known as the northern spotted deer or the Japanese deer, is a species of deer native to much of East Asia and introduced to other parts of the world. Previously found from northern Vietnam in the south t ...

(''C. nippon'') than they are to the red deer.

Elk and red deer produce fertile offspring in captivity, and the two species have freely inter-bred in New Zealand

New Zealand () is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and List of islands of New Zealand, over 600 smaller islands. It is the List of isla ...

's Fiordland National Park

Fiordland National Park is a national park in the south-west corner of South Island of New Zealand. It is the largest of the 13 National parks of New Zealand, national parks in New Zealand, with an area covering , and a major part of the Te W� ...

. The cross-bred animals have resulted in the disappearance of virtually all pure elk blood from the area. Key morphological differences that distinguish ''C. canadensis'' from ''C. elaphus'' are the former's wider rump patch and paler-hued antlers.

Subspecies

There are numeroussubspecies

In Taxonomy (biology), biological classification, subspecies (: subspecies) is a rank below species, used for populations that live in different areas and vary in size, shape, or other physical characteristics (Morphology (biology), morpholog ...

of elk described, with six from North America and four from Asia, although some taxonomists

In biology, taxonomy () is the scientific study of naming, defining ( circumscribing) and classifying groups of biological organisms based on shared characteristics. Organisms are grouped into taxa (singular: taxon), and these groups are given ...

consider them different ecotype

Ecotypes are organisms which belong to the same species but possess different phenotypical features as a result of environmental factors such as elevation, climate and predation. Ecotypes can be seen in wide geographical distributions and may event ...

s or races of the same species (adapted to local environments through minor changes in appearance and behavior). Populations vary in antler shape and size, body size, coloration and mating behavior. DNA

Deoxyribonucleic acid (; DNA) is a polymer composed of two polynucleotide chains that coil around each other to form a double helix. The polymer carries genetic instructions for the development, functioning, growth and reproduction of al ...

investigations of the Eurasian subspecies revealed that phenotypic

In genetics, the phenotype () is the set of observable characteristics or traits of an organism. The term covers the organism's morphology (physical form and structure), its developmental processes, its biochemical and physiological propert ...

variation in antlers, mane and rump patch development are based on "climatic-related lifestyle factors".

Of the six subspecies of elk known to have inhabited North America in historical times, four remain, including the Roosevelt (''C. canadensis roosevelti''), Tule

''Schoenoplectus acutus'' ( syn. ''Scirpus acutus, Schoenoplectus lacustris, Scirpus lacustris'' subsp. ''acutus''), called tule , common tule, hardstem tule, tule rush, hardstem bulrush, or viscid bulrush, is a giant species of sedge in the p ...

(''C. c. nannodes''), Manitoban (''C. c. manitobensis'') and Rocky Mountain elk

The Rocky Mountain elk (''Cervus canadensis nelsoni'') is a subspecies of elk found in the Rocky Mountains and adjacent ranges of Western North America.

Description

The Rocky Mountain Elks are the second largest animals in the elk subfamily, ...

(''C. c. nelsoni''). The eastern elk

The eastern elk (''Cervus canadensis canadensis'') is an extinct subspecies or distinct population of elk that inhabited the northern and eastern United States, and southern Canada. The last eastern elk was shot in Pennsylvania on September 1, 1 ...

(''C. c. canadensis'') and Merriam's elk

The Merriam's elk (''Cervus canadensis merriami'') is an extinct subspecies of elk once found in the arid lands of the southwestern United States (in Arizona, New Mexico and Texas), as well as in Mexico. From the first New World arrival of Europ ...

(''C. c. merriami'') subspecies have been extinct for at least a century.

Four subspecies described from the Asian continent include the Altai wapiti

The Altai wapiti, sometimes called the Altai elk, or simply the Altai Deer, is a subspecies of ''Cervus canadensis'' found in the forest hills of southern Siberia, northwestern Mongolia, and northern Xinjiang province of China

China, offi ...

(''C. c. sibiricus'') and the Tianshan wapiti (''C. c. songaricus''). Two distinct subspecies found in China, Mongolia

Mongolia is a landlocked country in East Asia, bordered by Russia to the north and China to the south and southeast. It covers an area of , with a population of 3.5 million, making it the world's List of countries and dependencies by po ...

, the Korean Peninsula

Korea is a peninsular region in East Asia consisting of the Korean Peninsula, Jeju Island, and smaller islands. Since the end of World War II in 1945, it has been politically divided at or near the 38th parallel between North Korea (Dem ...

and Siberia

Siberia ( ; , ) is an extensive geographical region comprising all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has formed a part of the sovereign territory of Russia and its predecessor states ...

are the Manchurian wapiti

The Manchurian wapiti (''Cervus canadensis xanthopygus'') is a putative subspecies of the wapiti native to East Asia. It may be identified as its own species, ''Cervus xanthopygus''.

Description

The Manchurian wapiti's coat is reddish brown dur ...

(''C. c. xanthopygus'') and the Alashan wapiti (''C. c. alashanicus''). The Manchuria

Manchuria is a historical region in northeast Asia encompassing the entirety of present-day northeast China and parts of the modern-day Russian Far East south of the Uda (Khabarovsk Krai), Uda River and the Tukuringra-Dzhagdy Ranges. The exact ...

n subspecies is darker, and more reddish, in coloration than other populations. The Alashan wapiti of northern Central China

Central China () is a List of regions of China, region in China. It mainly includes the provinces of China, provinces of Henan, Hubei and Hunan. Jiangxi is sometimes also regarded to be part of this region. Central China is now officially par ...

is the smallest of all the subspecies, has the lightest coloration, and is one of the least-studied.

Recent DNA analyses suggest that there are no more than three or four total subspecies of elk. All American forms, aside from possibly the Tule and the Roosevelt's elk, seem to belong to one subspecies—''Cervus c. canadensis''; even the Siberian elk (''C. c. sibiricus'') is, more or less, physically identical to the American forms, and thus may belong to this subspecies, too. However, the Manchurian wapiti (''C. c. xanthopygus'') is clearly distinct from the Siberian forms, but not distinguishable from the Alashan wapiti. Still, due to the insufficient genetic material that rejects monophyly of ''C. canadensis'', some researchers consider it premature to include the Manchurian wapiti as a true subspecies of wapiti, and that it likely needs to be elevated to its own species, ''C. xanthopygus''. The Chinese forms (the Sichuan deer, Kansu red deer, and Tibetan red deer

The Tibetan red deer (''Cervus canadensis wallichi'') also known as ''shou'', is a subspecies of elk/wapiti native to the southern Tibetan highlands and Bhutan. Once believed to be near-extinct, its population has increased to over 8,300, the ma ...

) also belong to the wapiti, and were not distinguishable from each other by mitochondrial DNA studies. These Chinese subspecies are sometimes treated as a distinct species, namely the Central Asian red deer

The Central Asian red deer (''Cervus hanglu''), also known as the Tarim red deer, is a deer species native to Central Asia, where it used to be widely distributed, but is scattered today with small population units in several countries. It has be ...

(''Cervus hanglu''), which also includes the Kashmir stag

The Kashmir stag, also called hangul (), is a subspecies of Central Asian red deer endemic to Kashmir and surrounding areas. It is found in dense riverine forests in the valleys and mountains of Jammu and Kashmir and northern Himachal Pradesh. ...

.

* North American group

** Roosevelt's elk (''C. c. roosevelti'')

** Tule elk

The tule elk (''Cervus canadensis nannodes'') is a subspecies of elk found only in California, ranging from the grasslands and marshlands of the Central Valley to the grassy hills on the coast. The subspecies name derives from the tule (), ...

(''C. c. nannodes'')

** Manitoban elk

The Manitoban elk (''Cervus canadensis manitobensis'') is a subspecies of elk found in the Midwestern United States (specifically North Dakota) and southern regions of the Canadian Prairies (specifically Manitoba, Saskatchewan, and north-central ...

(''C. c. manitobensis'')

** Rocky Mountain elk

The Rocky Mountain elk (''Cervus canadensis nelsoni'') is a subspecies of elk found in the Rocky Mountains and adjacent ranges of Western North America.

Description

The Rocky Mountain Elks are the second largest animals in the elk subfamily, ...

(''C. c. nelsoni'')

** Eastern elk

The eastern elk (''Cervus canadensis canadensis'') is an extinct subspecies or distinct population of elk that inhabited the northern and eastern United States, and southern Canada. The last eastern elk was shot in Pennsylvania on September 1, 1 ...

(''C. c. canadensis''; extinct)

** Merriam's elk

The Merriam's elk (''Cervus canadensis merriami'') is an extinct subspecies of elk once found in the arid lands of the southwestern United States (in Arizona, New Mexico and Texas), as well as in Mexico. From the first New World arrival of Europ ...

(''C. c. merriami''; extinct)

* Asian/Eastern group

** Altai wapiti

The Altai wapiti, sometimes called the Altai elk, or simply the Altai Deer, is a subspecies of ''Cervus canadensis'' found in the forest hills of southern Siberia, northwestern Mongolia, and northern Xinjiang province of China

China, offi ...

(''C. c. sibiricus'')

** Tian Shan wapiti

The Tian Shan wapiti or Tian Shan maral (''Cervus canadensis songaricus''), is a subspecies of ''C. canadensis''. It is also called the Tian Shan elk in North American English.

Description

It is native to the Tian Shan Mountains in eastern K ...

(''C. c. songaricus'')

** Manchurian wapiti

The Manchurian wapiti (''Cervus canadensis xanthopygus'') is a putative subspecies of the wapiti native to East Asia. It may be identified as its own species, ''Cervus xanthopygus''.

Description

The Manchurian wapiti's coat is reddish brown dur ...

(''C. c. xanthopygus'')

** Alashan wapiti (''C. c. alashanicus'')

** Tibetan red deer

The Tibetan red deer (''Cervus canadensis wallichi'') also known as ''shou'', is a subspecies of elk/wapiti native to the southern Tibetan highlands and Bhutan. Once believed to be near-extinct, its population has increased to over 8,300, the ma ...

(''C. c. wallichii'')

eastern elk

The eastern elk (''Cervus canadensis canadensis'') is an extinct subspecies or distinct population of elk that inhabited the northern and eastern United States, and southern Canada. The last eastern elk was shot in Pennsylvania on September 1, 1 ...

File:The deer of all lands (1898) Altai wapiti.png, Illustration of Altai wapiti

The Altai wapiti, sometimes called the Altai elk, or simply the Altai Deer, is a subspecies of ''Cervus canadensis'' found in the forest hills of southern Siberia, northwestern Mongolia, and northern Xinjiang province of China

China, offi ...

File:The deer of all lands (1898) Bedford's deer.png, Illustration of Manchurian wapiti

The Manchurian wapiti (''Cervus canadensis xanthopygus'') is a putative subspecies of the wapiti native to East Asia. It may be identified as its own species, ''Cervus xanthopygus''.

Description

The Manchurian wapiti's coat is reddish brown dur ...

File:The deer of all lands (1898) Hangul.png, Illustration of Kashmir stag

The Kashmir stag, also called hangul (), is a subspecies of Central Asian red deer endemic to Kashmir and surrounding areas. It is found in dense riverine forests in the valleys and mountains of Jammu and Kashmir and northern Himachal Pradesh. ...

Characteristics

Cascade Range

The Cascade Range or Cascades is a major mountain range of western North America, extending from southern British Columbia through Washington (state), Washington and Oregon to Northern California. It includes both non-volcanic mountains, such as m ...

in the U.S. state

In the United States, a state is a constituent political entity, of which there are 50. Bound together in a political union, each state holds governmental jurisdiction over a separate and defined geographic territory where it shares its so ...

s of California

California () is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States that lies on the West Coast of the United States, Pacific Coast. It borders Oregon to the north, Nevada and Arizona to the east, and shares Mexico–United States border, an ...

, Oregon

Oregon ( , ) is a U.S. state, state in the Pacific Northwest region of the United States. It is a part of the Western U.S., with the Columbia River delineating much of Oregon's northern boundary with Washington (state), Washington, while t ...

and Washington

Washington most commonly refers to:

* George Washington (1732–1799), the first president of the United States

* Washington (state), a state in the Pacific Northwest of the United States

* Washington, D.C., the capital of the United States

** A ...

, and in the Canadian province of British Columbia

British Columbia is the westernmost Provinces and territories of Canada, province of Canada. Situated in the Pacific Northwest between the Pacific Ocean and the Rocky Mountains, the province has a diverse geography, with rugged landscapes that ...

. Roosevelt elk have been introduced into Alaska

Alaska ( ) is a non-contiguous U.S. state on the northwest extremity of North America. Part of the Western United States region, it is one of the two non-contiguous U.S. states, alongside Hawaii. Alaska is also considered to be the north ...

, where the largest males are estimated to weigh up to . More typically, male Roosevelt elk weigh around , while females weigh .. Male tule elk weigh while females weigh . The whole weights of adult male Manitoban elk range from . Females have a mean weight of . The elk is the second largest extant species of deer, after the moose

The moose (: 'moose'; used in North America) or elk (: 'elk' or 'elks'; used in Eurasia) (''Alces alces'') is the world's tallest, largest and heaviest extant species of deer and the only species in the genus ''Alces''. It is also the tal ...

.

Antlers are made of bone, which can grow at a rate of per day. While actively growing, a soft layer of highly vascularized skin known as velvet

Velvet is a type of woven fabric with a dense, even pile (textile), pile that gives it a distinctive soft feel. Historically, velvet was typically made from silk. Modern velvet can be made from silk, linen, cotton, wool, synthetic fibers, silk ...

covers and protects them. This is shed in the summer when the antlers have fully developed. Bull elk typically have around six tines on each antler. The Siberian and North American elk carry the largest antlers while the Altai wapiti has the smallest. Roosevelt bull antlers can weigh . The formation and retention of antlers are testosterone

Testosterone is the primary male sex hormone and androgen in Male, males. In humans, testosterone plays a key role in the development of Male reproductive system, male reproductive tissues such as testicles and prostate, as well as promoting se ...

-driven. In late winter and early spring, the testosterone level drops, which causes the antlers to shed.

During the fall, elk grow a thicker coat of hair, which helps to insulate them during the winter. Both male and female North American elk grow thin neck manes; females of other subspecies may not. By early summer, the heavy winter coat has been shed. Elk are known to rub against trees and other objects to help remove hair from their bodies. All elk have small and clearly defined rump patches with short tails. They have different coloration based on the seasons and types of habitats, with gray or lighter coloration prevalent in the winter and a more reddish, darker coat in the summer. Subspecies living in arid climates tend to have lighter colored coats than do those living in forests. Most have lighter yellow-brown to orange-brown coats in contrast to dark brown hair on the head, neck, and legs during the summer. Forest-adapted Manchurian and Alaskan wapitis have red or reddish-brown coats with less contrast between the body coat and the rest of the body during the summer months. Calves are born spotted, as is common with many deer species, and lose them by the end of summer. Adult Manchurian wapiti may retain a few orange spots on the back of their summer coats until they are older. This characteristic has also been observed in the forest-adapted European red deer.

During the fall, elk grow a thicker coat of hair, which helps to insulate them during the winter. Both male and female North American elk grow thin neck manes; females of other subspecies may not. By early summer, the heavy winter coat has been shed. Elk are known to rub against trees and other objects to help remove hair from their bodies. All elk have small and clearly defined rump patches with short tails. They have different coloration based on the seasons and types of habitats, with gray or lighter coloration prevalent in the winter and a more reddish, darker coat in the summer. Subspecies living in arid climates tend to have lighter colored coats than do those living in forests. Most have lighter yellow-brown to orange-brown coats in contrast to dark brown hair on the head, neck, and legs during the summer. Forest-adapted Manchurian and Alaskan wapitis have red or reddish-brown coats with less contrast between the body coat and the rest of the body during the summer months. Calves are born spotted, as is common with many deer species, and lose them by the end of summer. Adult Manchurian wapiti may retain a few orange spots on the back of their summer coats until they are older. This characteristic has also been observed in the forest-adapted European red deer.

Behavior and ecology

Elk are among the mostgregarious

Sociality is the degree to which individuals in an animal population tend to associate in social groups (gregariousness) and form cooperative societies.

Sociality is a survival response to evolutionary pressures. For example, when a mother was ...

deer species. During the summer group size can reach 400 individuals. For most of the year, adult males and females are segregated into different herds. Female herds are larger while bulls form small groups and may even travel alone. Young bulls may associate with older bulls or female groups. Male and female herds come together during the mating season, which may begin in late August. Males try to intimidate rivals by vocalizing and displaying with their antlers. If neither bull backs down, they engage in antler wrestling, sometimes sustaining serious injuries.

Bulls have a loud, high-pitched, whistle-like vocalization known as ''bugling'', which advertise the male's fitness over great distances. Unusual for a vocalization produced by a large animal, buglings can reach a frequency of 4000 Hz. This is achieved by blowing air from the glottis

The glottis (: glottises or glottides) is the opening between the vocal folds (the rima glottidis). The glottis is crucial in producing sound from the vocal folds.

Etymology

From Ancient Greek ''γλωττίς'' (glōttís), derived from ''γ ...

through the nasal cavities. Elk can produce deeper pitched (150 Hz) sounds using the larynx

The larynx (), commonly called the voice box, is an organ (anatomy), organ in the top of the neck involved in breathing, producing sound and protecting the trachea against food aspiration. The opening of larynx into pharynx known as the laryngeal ...

. Cows produce an alarm bark to alert other members of the herd to danger, while calves will produce a high-pitched scream when attacked.

Reproduction and life cycle

Female elk have a shortestrus

The estrous cycle (, originally ) is a set of recurring physiological changes induced by reproductive hormones in females of mammalian subclass Theria. Estrous cycles start after sexual maturity in females and are interrupted by anestrous phas ...

cycle of only a day or two, and matings usually involve a dozen or more attempts. By the autumn of their second year, females can produce one and, very rarely, two offspring. Reproduction is most common when cows weigh at least . Dominant bulls follow groups of cows during the rut from August into early winter. A bull will defend his harem of 20 cows or more from competing bulls and predators. Bulls also dig holes in the ground called wallows, in which they urinate and roll their bodies. A male elk's urethra points upward so that urine is sprayed almost at a right angle to the penis. The urine soaks into their hair and gives them a distinct smell which attracts cows.

A bull interacts with cows in his harem in two ways: herding and courtship. When a female wanders too far away from the harem's range, the male will rush ahead of her, block her path and aggressively rush her back to the harem. Herding behavior is accompanied by a stretched out and lowered neck and the antlers laid back. A bull may get violent and hit the cow with his antlers. During courtship, the bull is more peaceful and approaches her with his head and antlers raised. The male signals his intention to test the female for sexual receptivity by flicking his tongue. If not ready, a cow will lower her head and weave from side to side while opening and closing her mouth. The bull will stop in response in order not to scare her. Otherwise, the bull will copiously lick the female and then mount her.

Younger, less dominant bulls, known as "spike bulls", because their antlers have not yet forked, will harass unguarded cows. These bulls are impatient and will not perform any courtship rituals and will continue to pursue a female even when she signals him to stop. As such, they are less reproductively successful, and a cow may stay close to the big bull to avoid harassment. Dominant bulls are intolerant of spike bulls and will chase them away from their harems.

The

A bull interacts with cows in his harem in two ways: herding and courtship. When a female wanders too far away from the harem's range, the male will rush ahead of her, block her path and aggressively rush her back to the harem. Herding behavior is accompanied by a stretched out and lowered neck and the antlers laid back. A bull may get violent and hit the cow with his antlers. During courtship, the bull is more peaceful and approaches her with his head and antlers raised. The male signals his intention to test the female for sexual receptivity by flicking his tongue. If not ready, a cow will lower her head and weave from side to side while opening and closing her mouth. The bull will stop in response in order not to scare her. Otherwise, the bull will copiously lick the female and then mount her.

Younger, less dominant bulls, known as "spike bulls", because their antlers have not yet forked, will harass unguarded cows. These bulls are impatient and will not perform any courtship rituals and will continue to pursue a female even when she signals him to stop. As such, they are less reproductively successful, and a cow may stay close to the big bull to avoid harassment. Dominant bulls are intolerant of spike bulls and will chase them away from their harems.

The gestation

Gestation is the period of development during the carrying of an embryo, and later fetus, inside viviparous animals (the embryo develops within the parent). It is typical for mammals, but also occurs for some non-mammals. Mammals during pregn ...

period is eight to nine months and the offspring weigh around . When the females are near to giving birth, they tend to isolate themselves from the main herd, and will remain isolated until the calf is large enough to escape predators. Calves are born spotted, as is common with many deer species, and they lose their spots by the end of summer. After two weeks, calves are able to join the herd, and are fully weaned at two months of age. Elk calves are as large as an adult white-tailed deer

The white-tailed deer (''Odocoileus virginianus''), also known Common name, commonly as the whitetail and the Virginia deer, is a medium-sized species of deer native to North America, North, Central America, Central and South America. It is the ...

by the time they are six months old. Elk will leave their natal (birth) ranges before they are three years old. Males disperse more often than females, as adult cows are more tolerant of female offspring from previous years. Elk live 20 years or more in captivity but average 10 to 13 years in the wild. In some subspecies that suffer less predation, they may live an average of 15 years in the wild.

Migration

As is true for many species of deer, especially those in mountainous regions, elk

As is true for many species of deer, especially those in mountainous regions, elk migrate

Migration, migratory, or migrate may refer to: Human migration

* Human migration, physical movement by humans from one region to another

** International migration, when peoples cross state boundaries and stay in the host state for some minimum le ...

into areas of higher altitude in the spring, following the retreating snows, and the opposite direction in the fall. Hunting pressure impacts migration and movement. During the winter, they favor wooded areas for the greater availability of food to eat. Elk do not appear to benefit from thermal cover. The Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem elk herds comprise as many as 40,000 individuals. During the spring and fall, they take part in the longest elk migration in the continental U.S., traveling as much as between summer and winter ranges. The Teton herd consists of between 9,000 and 13,000 elk and they spend winters on the National Elk Refuge

The National Elk Refuge is a Wildlife Refuge located in Jackson Hole in the U.S. state of Wyoming. It was created in 1912 to protect habitat and provide sanctuary for one of the largest elk (also known as wapiti) herds. With a total of , the ...

, having migrated south from the southern portions of Yellowstone National Park

Yellowstone National Park is a List of national parks of the United States, national park of the United States located in the northwest corner of Wyoming, with small portions extending into Montana and Idaho. It was established by the 42nd U ...

and west from the Shoshone

The Shoshone or Shoshoni ( or ), also known by the endonym Newe, are an Native Americans in the United States, Indigenous people of the United States with four large cultural/linguistic divisions:

* Eastern Shoshone: Wyoming

* Northern Shoshon ...

and Bridger–Teton National Forest

Bridger–Teton National Forest is located in western Wyoming, United States. The forest consists of , making it the third largest National forest (United States), National Forest outside Alaska. The forest stretches from Yellowstone National ...

s.

Diet

Elk are ruminants and therefore have four-chambered stomachs. Unlike white-tailed deer and moose, which are chiefly browsers, elk are similar to

Elk are ruminants and therefore have four-chambered stomachs. Unlike white-tailed deer and moose, which are chiefly browsers, elk are similar to cattle

Cattle (''Bos taurus'') are large, domesticated, bovid ungulates widely kept as livestock. They are prominent modern members of the subfamily Bovinae and the most widespread species of the genus '' Bos''. Mature female cattle are calle ...

in that they are primarily grazers. But like other deer, they also browse

Browsing is a kind of orienting strategy. It is supposed to identify something of relevance for the browsing organism. In context of humans, it is a metaphor taken from the animal kingdom. It is used, for example, about people browsing open sh ...

. Elk have a tendency to do most of their feeding in the mornings and evenings, seeking sheltered areas in between feedings to digest. Their diets vary somewhat depending on the season, with native grasses being a year-round supplement, tree bark (e.g. cedar

Cedar may refer to:

Trees and plants

*''Cedrus'', common English name cedar, an Old-World genus of coniferous trees in the plant family Pinaceae

* Cedar (plant), a list of trees and plants known as cedar

Places United States

* Cedar, Arizona

...

, wintergreen

Wintergreen is a group of aromatic plants. The term ''wintergreen'' once commonly referred to plants that remain green (continue photosynthesis) throughout the winter. The term ''evergreen'' is now more commonly used for this characteristic.

...

, eastern hemlock

''Tsuga canadensis'', also known as eastern hemlock, eastern hemlock-spruce, or Canadian hemlock, and in the French-speaking regions of Canada as ''pruche du Canada'', is a coniferous tree native to eastern North America. It is the state tree of ...

, sumac

Sumac or sumach ( , )—not to be confused with poison sumac—is any of the roughly 35 species of flowering plants in the genus ''Rhus'' (and related genera) of the cashew and mango tree family, Anacardiaceae. However, it is '' Rhus coriaria ...

, jack pine

Jack pine (''Pinus banksiana''), also known as grey pine or scrub pine, is a North American pine.

Distribution and habitat

Its native range in Canada is east of the Rocky Mountains from the Mackenzie River in the Northwest Territories t ...

, red maple

''Acer rubrum'', the red maple, also known as swamp maple, water maple, or soft maple, is one of the most common and widespread deciduous trees of eastern and central North America. The U.S. Forest Service recognizes it as the most abundant nati ...

, staghorn, and basswood

''Tilia americana'' is a species of tree in the family Malvaceae, native to eastern North America, from southeast Manitoba east to New Brunswick, southwest to northeast Oklahoma, southeast to South Carolina, and west along the Niobrara River to ...

) being consumed in winter, and sedge

The Cyperaceae () are a family of graminoid (grass-like), monocotyledonous flowering plants known as wikt:sedge, sedges. The family (biology), family is large; botanists have species description, described some 5,500 known species in about 90 ...

s, forbs

A forb or phorb is a herbaceous flowering plant that is not a graminoid (grass, sedge, or rush). The term is used in botany and in vegetation ecology especially in relation to grasslands and understory. Typically, these are eudicots without wood ...

, and tree sprouts during the summer. Favorites of the elk include dandelion

''Taraxacum'' () is a genus of flowering plants in the family Asteraceae, which consists of species commonly known as dandelions. The scientific and hobby study of the genus is known as taraxacology. The genus has a near-cosmopolitan distribu ...

s, aster

Aster or ASTER may refer to:

Biology

* ''Aster'' (genus), a genus of flowering plants

** List of ''Aster'' synonyms, other genera formerly included in ''Aster'' and still called asters in English

* Aster (cell biology), a cellular structure shap ...

, hawkweed

''Hieracium'' (),

known by the common name hawkweed and classically as (from ancient Greek ἱέραξ, 'hawk'),

is a genus of flowering plant in the family Asteraceae, and closely related to dandelion (''Taraxacum''), chicory (''Cichorium''), ...

, violet

Violet may refer to:

Common meanings

* Violet (color), a spectral color with wavelengths shorter than blue

* One of a list of plants known as violet, particularly:

** ''Viola'' (plant), a genus of flowering plants

Places United States

* Vi ...

s, clover

Clovers, also called trefoils, are plants of the genus ''Trifolium'' (), consisting of about 300 species of flowering plants in the legume family Fabaceae originating in Europe. The genus has a cosmopolitan distribution with the highest diversit ...

, and the occasional mushroom

A mushroom or toadstool is the fleshy, spore-bearing Sporocarp (fungi), fruiting body of a fungus, typically produced above ground on soil or another food source. ''Toadstool'' generally refers to a poisonous mushroom.

The standard for the n ...

. Elk consume an average of of vegetation daily. Particularly fond of aspen

Aspen is a common name for certain tree species in the Populus sect. Populus, of the ''Populus'' (poplar) genus.

Species

These species are called aspens:

* ''Populus adenopoda'' – Chinese aspen (China, south of ''P. tremula'')

* ''Populus da ...

sprouts which rise in the spring, elk have had some impact on aspen groves which have been declining in some regions where elk exist. Range and wildlife managers conduct surveys of elk pellet groups to monitor populations and resource use.

Research in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem

The Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem (GYE) is one of the last remaining large, nearly intact ecosystems in the northern temperate zone of Earth. It is located within the northern Rocky Mountains, in areas of northwestern Wyoming, southwestern Monta ...

has found that supplemental feeding of concentrated alfalfa

Alfalfa () (''Medicago sativa''), also called lucerne, is a perennial plant, perennial flowering plant in the legume family Fabaceae. It is cultivated as an important forage crop in many countries around the world. It is used for grazing, hay, ...

pellets leads to significant alterations in the elks' microbiome

A microbiome () is the community of microorganisms that can usually be found living together in any given habitat. It was defined more precisely in 1988 by Whipps ''et al.'' as "a characteristic microbial community occupying a reasonably wel ...

. The elk gut microbiome is typically characterized by a diverse community of bacteria specialized in breaking down complex plant fibers and cellulose

Cellulose is an organic compound with the chemical formula, formula , a polysaccharide consisting of a linear chain of several hundred to many thousands of glycosidic bond, β(1→4) linked glucose, D-glucose units. Cellulose is an important s ...

, whereas the supplementally fed gut microbiome may have less fiber-digesting bacteria. Therefore, transitioning from natural foraging to concentrated alfalfa pellets can cause changes in the gut microbiome that might affect the elk's ability to efficiently digest their natural diet or could potentially lead to imbalances that affect overall health.

Predators and defensive tactics

Predators of elk includewolves

The wolf (''Canis lupus''; : wolves), also known as the grey wolf or gray wolf, is a canine native to Eurasia and North America. More than thirty subspecies of ''Canis lupus'' have been recognized, including the dog and dingo, though gr ...

, coyotes

The coyote (''Canis latrans''), also known as the American jackal, prairie wolf, or brush wolf, is a species of canine native to North America. It is smaller than its close relative, the gray wolf, and slightly smaller than the closely relat ...

, brown

Brown is a color. It can be considered a composite color, but it is mainly a darker shade of orange. In the CMYK color model used in printing and painting, brown is usually made by combining the colors Orange (colour), orange and black.

In the ...

and black

Black is a color that results from the absence or complete absorption of visible light. It is an achromatic color, without chroma, like white and grey. It is often used symbolically or figuratively to represent darkness.Eva Heller, ''P ...

bears

Bears are carnivoran mammals of the family Ursidae (). They are classified as caniforms, or doglike carnivorans. Although only eight species of bears are extant, they are widespread, appearing in a wide variety of habitats throughout most o ...

, cougars

The cougar (''Puma concolor'') (, '' KOO-gər''), also called puma, mountain lion, catamount and panther is a large small cat native to the Americas. It inhabits North, Central and South America, making it the most widely distributed wild ...

, and Siberian tigers

The Siberian tiger or Amur tiger is a population of the tiger subspecies '' Panthera tigris tigris'' native to Northeast China, the Russian Far East, and possibly North Korea. It once ranged throughout the Korean Peninsula, but currently inhab ...

. Coyote

The coyote (''Canis latrans''), also known as the American jackal, prairie wolf, or brush wolf, is a species of canis, canine native to North America. It is smaller than its close relative, the Wolf, gray wolf, and slightly smaller than the c ...

packs mostly prey on elk calves, though they can sometimes take a winter- or disease-weakened adult. In the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem

The Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem (GYE) is one of the last remaining large, nearly intact ecosystems in the northern temperate zone of Earth. It is located within the northern Rocky Mountains, in areas of northwestern Wyoming, southwestern Monta ...

, which includes Yellowstone National Park, bears are the most significant predators of calves while healthy bulls have never been recorded to be killed by bears and such encounters can be fatal for bears. The killing of cows in their prime is more likely to affect population growth than the killing of bulls or calves.

Elk may avoid predation by switching from grazing to browsing. Grazing puts an elk in the compromising situation of being in an open area with its head down, leaving it unable to see what is going on in the surrounding area. Living in groups also lessens the risk of an individual falling to predation. Large bull elk are less vulnerable and can afford to wander alone, while cows stay in larger groups for protection for their calves. Bulls are more vulnerable to predation by wolves in late winter, after they have been weakened by months of chasing females and fighting. Males that have recently lost their antlers are more likely to be preyed upon.

Parasites and disease

At least 53 species ofprotist

A protist ( ) or protoctist is any eukaryotic organism that is not an animal, land plant, or fungus. Protists do not form a natural group, or clade, but are a paraphyletic grouping of all descendants of the last eukaryotic common ancest ...

and animal parasite

Parasitism is a Symbiosis, close relationship between species, where one organism, the parasite, lives (at least some of the time) on or inside another organism, the Host (biology), host, causing it some harm, and is Adaptation, adapted str ...

s have been identified in elk. Most of these parasites seldom lead to significant mortality among wild or captive elk. '' Parelaphostrongylus tenuis'' (brainworm or meningeal worm) is a parasitic nematode

The nematodes ( or ; ; ), roundworms or eelworms constitute the phylum Nematoda. Species in the phylum inhabit a broad range of environments. Most species are free-living, feeding on microorganisms, but many are parasitic. Parasitic worms (h ...

known to affect the spinal cord and brain tissue of elk and other species, leading to death. The definitive host is the white-tailed deer, in which it normally has no ill effects. Snails and slugs, the intermediate hosts, can be inadvertently consumed by elk during grazing. The liver fluke

Liver fluke is a collective name of a polyphyletic group of parasitic trematodes under the phylum Platyhelminthes.

They are principally parasites of the liver of various mammals, including humans. Capable of moving along the blood circulation, ...

''Fascioloides magna

''Fascioloides magna'', also known as giant liver fluke, large American liver fluke or deer fluke, is trematode parasite that occurs in wild and domestic ruminants in North America and Europe. Adult flukes occur in the liver of the definitive hos ...

'' and the nematode ''Dictyocaulus viviparus

''Dictyocaulus viviparus'' is a species of nematodes belonging to the family Dictyocaulidae.

The species has cosmopolitan distribution

In biogeography, a cosmopolitan distribution is the range of a taxon that extends across most or all of ...

'' are also commonly found parasites that can be fatal to elk.

Chronic wasting disease

Chronic wasting disease (CWD), sometimes called zombie deer disease, is a transmissible spongiform encephalopathy (TSE) affecting deer. TSEs are a family of diseases thought to be caused by misfolded proteins called prions and include simila ...

, transmitted by a misfolded protein known as a prion

A prion () is a Proteinopathy, misfolded protein that induces misfolding in normal variants of the same protein, leading to cellular death. Prions are responsible for prion diseases, known as transmissible spongiform encephalopathy (TSEs), w ...

, affects the brain tissue in elk, and has been detected throughout their range in North America. First documented in the late 1960s in mule deer, the disease has affected elk on game farms and in the wild in a number of regions. Elk that have contracted the disease begin to show weight loss, changes in behavior, increased watering needs, excessive salivation and urinating and difficulty swallowing, and at an advanced stage, the disease leads to death. No risks to humans have been documented, nor has the disease been demonstrated to pose a threat to domesticated cattle. In 2002, South Korea

South Korea, officially the Republic of Korea (ROK), is a country in East Asia. It constitutes the southern half of the Korea, Korean Peninsula and borders North Korea along the Korean Demilitarized Zone, with the Yellow Sea to the west and t ...

banned the importation of elk antler velvet due to concerns about chronic wasting disease.

The Gram-negative

Gram-negative bacteria are bacteria that, unlike gram-positive bacteria, do not retain the crystal violet stain used in the Gram staining method of bacterial differentiation. Their defining characteristic is that their cell envelope consists ...

bacteria

Bacteria (; : bacterium) are ubiquitous, mostly free-living organisms often consisting of one Cell (biology), biological cell. They constitute a large domain (biology), domain of Prokaryote, prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micr ...

l disease brucellosis

Brucellosis is a zoonosis spread primarily via ingestion of raw milk, unpasteurized milk from infected animals. It is also known as undulant fever, Malta fever, and Mediterranean fever.

The bacteria causing this disease, ''Brucella'', are small ...

occasionally affects elk in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, the only place in the U.S. where the disease is still known to exist, though this can extend out to the Bighorn Mountains

The Bighorn Mountains ( or ) are a mountain range in northern Wyoming and southern Montana in the United States, forming a northwest-trending spur from the Rocky Mountains extending approximately northward on the Great Plains. They are separa ...

. In domesticated cattle, brucellosis causes infertility, abortions, and reduced milk production. It is transmitted to humans as undulant fever, producing influenza

Influenza, commonly known as the flu, is an infectious disease caused by influenza viruses. Symptoms range from mild to severe and often include fever, runny nose, sore throat, muscle pain, headache, coughing, and fatigue. These sympto ...

-like symptoms that may last for years. Though bison are more likely to transmit the disease to other animals, elk inadvertently transmitted brucellosis to horses in Wyoming and cattle in Idaho

Idaho ( ) is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Pacific Northwest and Mountain states, Mountain West subregions of the Western United States. It borders Montana and Wyoming to the east, Nevada and Utah to the south, and Washington (state), ...