The University of Edinburgh ( sco, University o Edinburgh, gd, Oilthigh Dhùn Èideann; abbreviated as ''Edin.'' in

post-nominals) is a

public research university based in

Edinburgh

Edinburgh ( ; gd, Dùn Èideann ) is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 Council areas of Scotland, council areas. Historically part of the county of Midlothian (interchangeably Edinburghshire before 1921), it is located in Lothian ...

,

Scotland. Granted a

royal charter by King

James VI in 1582 and officially opened in 1583, it is one of Scotland's

four ancient universities and the

sixth-oldest university in continuous operation in the

English-speaking world.

The university played an important role in Edinburgh becoming a chief intellectual centre during the

Scottish Enlightenment

The Scottish Enlightenment ( sco, Scots Enlichtenment, gd, Soillseachadh na h-Alba) was the period in 18th- and early-19th-century Scotland characterised by an outpouring of intellectual and scientific accomplishments. By the eighteenth century ...

and contributed to the city being nicknamed the "

Athens of the North Athens of the North may refer to one of several cities in Northern Europe that, due to their prominence in science and culture, were likened to Classical Athens:

* A nickname for Edinburgh, Scotland, see: Etymology of Edinburgh

* A nickname for ...

."

Edinburgh is ranked among the top universities in the United Kingdom and the world.

Edinburgh is a member of several associations of research-intensive universities, including the

Coimbra Group,

League of European Research Universities,

Russell Group,

Una Europa, and

Universitas 21. In the

fiscal year ending 31 July 2021, it had a total income of £1.176 billion, of which £324.0 million was from research grants and contracts, with the

third-largest endowment in the UK, behind only

Cambridge

Cambridge ( ) is a university city and the county town in Cambridgeshire, England. It is located on the River Cam approximately north of London. As of the 2021 United Kingdom census, the population of Cambridge was 145,700. Cambridge beca ...

and

Oxford.

The university has five main campuses in the city of Edinburgh, which include many buildings of historical and architectural significance such as those in the

Old Town

In a city or town, the old town is its historic or original core. Although the city is usually larger in its present form, many cities have redesignated this part of the city to commemorate its origins after thorough renovations. There are ma ...

.

Edinburgh receives over 60,000 undergraduate applications per year, making it the second-most popular university in the UK by volume of applications.

It is the

eighth-largest university in the UK by enrolment, with 35,375 students in 2019/20.

Edinburgh had the eighth-highest average

UCAS points

The UCAS Tariff (formerly called UCAS Points System) is used to allocate points to post-16 qualifications (Level 3 qualifications on the Regulated Qualifications Framework). Universities and colleges may use it when making offers to applicants. A p ...

amongst British universities for new entrants in 2020.

The university continues to have links to the

British royal family, having had

Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh as its

chancellor

Chancellor ( la, cancellarius) is a title of various official positions in the governments of many nations. The original chancellors were the of Roman courts of justice—ushers, who sat at the or lattice work screens of a basilica or law cou ...

from 1953 to 2010 and

Anne, Princess Royal

Anne, Princess Royal (Anne Elizabeth Alice Louise; born 15 August 1950), is a member of the British royal family. She is the second child and only daughter of Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh, and the only sister of Kin ...

since March 2011.

The

alumni of the university includes some of the major figures of modern history. Inventor

Alexander Graham Bell

Alexander Graham Bell (, born Alexander Bell; March 3, 1847 – August 2, 1922) was a Scottish-born inventor, scientist and engineer who is credited with patenting the first practical telephone. He also co-founded the American Telephone and Te ...

,

naturalist Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English natural history#Before 1900, naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all speci ...

, philosopher

David Hume, and physicist

James Clerk Maxwell studied at Edinburgh, as did writers such as Sir

J. M. Barrie, Sir

Arthur Conan Doyle

Sir Arthur Ignatius Conan Doyle (22 May 1859 – 7 July 1930) was a British writer and physician. He created the character Sherlock Holmes in 1887 for '' A Study in Scarlet'', the first of four novels and fifty-six short stories about Ho ...

,

J. K. Rowling, Sir

Walter Scott, and

Robert Louis Stevenson. The university counts several heads of state and government amongst its graduates, including

three British Prime Ministers. Three

Supreme Court Justices of the UK were educated at Edinburgh. , 19

Nobel Prize laureates, four

Pulitzer Prize

The Pulitzer Prize () is an award for achievements in newspaper, magazine, online journalism, literature, and musical composition within the United States. It was established in 1917 by provisions in the will of Joseph Pulitzer, who had made h ...

winners, three

Turing Award winners, and an

Abel Prize

The Abel Prize ( ; no, Abelprisen ) is awarded annually by the King of Norway to one or more outstanding mathematicians. It is named after the Norwegian mathematician Niels Henrik Abel (1802–1829) and directly modeled after the Nobel Prizes. ...

laureate and

Fields Medal

The Fields Medal is a prize awarded to two, three, or four mathematicians under 40 years of age at the International Congress of the International Mathematical Union (IMU), a meeting that takes place every four years. The name of the award h ...

ist have been affiliated with Edinburgh as alumni or academic staff.

Edinburgh alumni have won a total of ten

Olympic gold medals

An Olympic medal is awarded to successful competitors at one of the Olympic Games. There are three classes of medal to be won: gold, silver, and bronze, awarded to first, second, and third place, respectively. The granting of awards is laid ou ...

.

History

Early history

In 1557, Bishop

Robert Reid of

St Magnus Cathedral on

Orkney

Orkney (; sco, Orkney; on, Orkneyjar; nrn, Orknøjar), also known as the Orkney Islands, is an archipelago in the Northern Isles of Scotland, situated off the north coast of the island of Great Britain. Orkney is 10 miles (16 km) north ...

made a

will

Will may refer to:

Common meanings

* Will and testament, instructions for the disposition of one's property after death

* Will (philosophy), or willpower

* Will (sociology)

* Will, volition (psychology)

* Will, a modal verb - see Shall and will

...

containing an endowment of 8,000

merks

The merk is a long-obsolete Scottish silver coin. Originally the same word as a money mark of silver, the merk was in circulation at the end of the 16th century and in the 17th century. It was originally valued at 13 shillings 4 pence (exactly ...

to build a college in Edinburgh.

Unusually for his time, Reid's vision included the teaching of

rhetoric

Rhetoric () is the art of persuasion, which along with grammar and logic (or dialectic), is one of the three ancient arts of discourse. Rhetoric aims to study the techniques writers or speakers utilize to inform, persuade, or motivate parti ...

and

poetry, alongside more traditional subjects such as

philosophy

Philosophy (from , ) is the systematized study of general and fundamental questions, such as those about existence, reason, knowledge, values, mind, and language. Such questions are often posed as problems to be studied or resolved. Some ...

.

However, the bequest was delayed by more than 25 years due to the religious revolution that led to the

Reformation Parliament of 1560.

The plans were revived in the late 1570s through efforts by the

Edinburgh Town Council

The politics of Edinburgh are expressed in the deliberations and decisions of the City of Edinburgh Council, in elections to the council, the Scottish Parliament and the UK Parliament.

Also, as Scotland's capital city, Edinburgh is host to th ...

, first minister of Edinburgh

James Lawson, and

Lord Provost William Little.

When Reid's descendants were unwilling to pay out the sum, the town council petitioned King

James VI and his

Privy Council

A privy council is a body that advises the head of state of a state, typically, but not always, in the context of a monarchic government. The word "privy" means "private" or "secret"; thus, a privy council was originally a committee of the mon ...

. The King brokered a monetary compromise and granted a

royal charter on 14 April 1582, empowering the town council to create a college of higher education.

A college established by secular authorities was unprecedented in

newly Presbyterian Scotland, as all previous Scottish universities had been founded through

papal bulls. Notably, Edinburgh was the fourth Scottish university in a period when the richer and more populous

England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe ...

had only two.

Named ''Tounis College'' (Town's College), the university opened its doors to students on 14 October 1583, with an attendance of 80–90.

At the time, the college mainly covered

liberal arts and

divinity.

Instruction began under the charge of a graduate from the

University of St Andrews, theologian

Robert Rollock, who first served as Regent, and from 1586 as principal of the college.

Initially Rollock was the sole instructor for first-year students, and he was expected to tutor the 1583 intake for all four years of their degree in every subject. The first cohort finished their studies in 1587, and 47 students graduated (or 'laureated') with an

M.A. degree.

When King James VI visited Scotland in 1617, he held a

disputation with the college's professors, after which he decreed that it should henceforth be called the "Colledge ''

ic' of King James". The university was known as both ''Tounis College'' and ''King James' College'' until it gradually assumed the name of the University of Edinburgh during the 17th century.

After the deposition of King

James II and VII

James VII and II (14 October 1633 16 September 1701) was King of England and King of Ireland as James II, and King of Scotland as James VII from the death of his elder brother, Charles II, on 6 February 1685. He was deposed in the Glorious Re ...

during the

Glorious Revolution

The Glorious Revolution; gd, Rèabhlaid Ghlòrmhor; cy, Chwyldro Gogoneddus , also known as the ''Glorieuze Overtocht'' or ''Glorious Crossing'' in the Netherlands, is the sequence of events leading to the deposition of King James II and ...

in 1688, the

Parliament of Scotland passed legislation designed to root out

Jacobite

Jacobite means follower of Jacob or James. Jacobite may refer to:

Religion

* Jacobites, followers of Saint Jacob Baradaeus (died 578). Churches in the Jacobite tradition and sometimes called Jacobite include:

** Syriac Orthodox Church, sometimes ...

sympathisers amongst university staff.

In Edinburgh, this led to the dismissal of Principal

Alexander Monro and several professors and regents after a government visitation in 1690. The university was subsequently led by Principal

Gilbert Rule, one of the inquisitors on the visitation committee.

18th and 19th century

The late 17th and early 18th centuries were marked by a power struggle between the university and town council, which had ultimate authority over staff appointments, curricula, and examinations.

After a series of challenges by the university, the conflict culminated in the council seizing the college records in 1704.

Relations were only gradually repaired over the next 150 years and suffered repeated setbacks.

The university expanded by founding a Faculty of Law in 1707, a Faculty of Arts in 1708, and a Faculty of Medicine in 1726. In 1762, Reverend

Hugh Blair was appointed by King

George III as the first

Regius Professor of Rhetoric and Belles-Lettres

The Regius Chair of Rhetoric and English Literature at the University of Edinburgh was established in 1762 (as the Regius Chair of Rhetoric and Belles Lettres). It is arguably the first professorship of English Literature established anywhere in ...

. This formalised literature as a subject and marks the foundation of the English Literature department, making Edinburgh the oldest centre of literary education in Britain.

During the 18th century, the university was at the centre of the

Scottish Enlightenment

The Scottish Enlightenment ( sco, Scots Enlichtenment, gd, Soillseachadh na h-Alba) was the period in 18th- and early-19th-century Scotland characterised by an outpouring of intellectual and scientific accomplishments. By the eighteenth century ...

. The ideas of the

Age of Enlightenment fell on especially fertile ground in Edinburgh because of the university's democratic and secular origin; its organization as a single entity instead of loosely connected colleges, which encouraged academic exchange; its adoption of the more flexible Dutch model of professorship, rather than having student cohorts taught by a single regent; and the lack of land endowments as its source of income, which meant its faculty operated in a more competitive environment.

Between 1750 and 1800, this system produced and attracted key Enlightenment figures such as chemist

Joseph Black, economist

Adam Smith

Adam Smith (baptized 1723 – 17 July 1790) was a Scottish economist and philosopher who was a pioneer in the thinking of political economy and key figure during the Scottish Enlightenment. Seen by some as "The Father of Economics"——� ...

, historian

William Robertson, philosophers

David Hume and

Dugald Stewart, physician

William Cullen, and early sociologist

Adam Ferguson, many of which taught concurrently.

By the time the

Royal Society of Edinburgh

The Royal Society of Edinburgh is Scotland's national academy of science and letters. It is a registered charity that operates on a wholly independent and non-partisan basis and provides public benefit throughout Scotland. It was established i ...

was founded in 1783, the university was regarded as one of the world's preeminent scientific institutions, and

Voltaire called Edinburgh a "hotbed of genius" as a result.

Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin ( April 17, 1790) was an American polymath who was active as a writer, scientist, inventor

An invention is a unique or novel device, method, composition, idea or process. An invention may be an improvement upon a m ...

believed that the university possessed "a set of as truly great men, Professors of the Several Branches of Knowledge, as have ever appeared in any Age or Country".

Thomas Jefferson felt that as far as science was concerned, "no place in the world can pretend to a competition with Edinburgh".

In 1785,

Henry Dundas introduced the

South Bridge Act in the

House of Commons; one of the bill's goals was to use

South Bridge as a location for the university, which had existed in a hotchpotch of buildings since its establishment. The site was used to construct

Old College, the university's first custom-built building, by architect

William Henry Playfair to plans by

Robert Adam. During the 18th century, the university developed a particular forte in teaching

anatomy and the developing science of

surgery

Surgery ''cheirourgikē'' (composed of χείρ, "hand", and ἔργον, "work"), via la, chirurgiae, meaning "hand work". is a medical specialty that uses operative manual and instrumental techniques on a person to investigate or treat a pat ...

, and it was considered one of the best medical schools in the English-speaking world. Bodies to be used for

dissection

Dissection (from Latin ' "to cut to pieces"; also called anatomization) is the dismembering of the body of a deceased animal or plant to study its anatomical structure. Autopsy is used in pathology and forensic medicine to determine the cause o ...

were brought to the university's Anatomy Theatre through a secret tunnel from a nearby house (today's College Wynd student accommodation), which was also used by murderers

Burke and Hare to deliver the corpses of their victims during the 1820s.

After 275 years of governance by the town council, the

Universities (Scotland) Act 1858 gave the university full authority over its own affairs.

The act established governing bodies including a university court and a general council, and redefined the roles of key officials like the chancellor, rector, and principal.

The

Edinburgh Seven

The Edinburgh Seven were the first group of matriculated undergraduate female students at any British university. They began studying medicine at the University of Edinburgh in 1869 and, although the Court of Session ruled that they should nev ...

were the first group of matriculated undergraduate female students at any British university. Led by

Sophia Jex-Blake, they began studying medicine at the University of Edinburgh in 1869. Although the university blocked them from graduating and qualifying as doctors, their campaign gained national attention and won them many supporters, including

Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English natural history#Before 1900, naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all speci ...

. Their efforts put the rights of women to higher education on the national political agenda, which eventually resulted in legislation allowing women to study at all Scottish universities in 1889. The university admitted women to graduate in medicine in 1893. In 2015, the Edinburgh Seven were commemorated with a plaque at the university, and in 2019 they were posthumously awarded with medical degrees.

Towards the end of the 19th century, Old College was becoming overcrowded. After a bequest from Sir

David Baxter, the university started planning new buildings in earnest. Sir

Robert Rowand Anderson won the public architectural competition and was commissioned to design new premises for the

Medical School

A medical school is a tertiary educational institution, or part of such an institution, that teaches medicine, and awards a professional degree for physicians. Such medical degrees include the Bachelor of Medicine, Bachelor of Surgery (MBBS, M ...

in 1877. Initially, the design incorporated a

campanile

A bell tower is a tower that contains one or more bells, or that is designed to hold bells even if it has none. Such a tower commonly serves as part of a Christian church, and will contain church bells, but there are also many secular bell tower ...

and a hall for examination and graduation, but this was seen as too ambitious. The new Medical School opened in 1884, but the building was not completed until 1888. After funds were donated by politician and brewer

William McEwan in 1894, a separate graduation building was constructed after all, also designed by Anderson. The resulting

McEwan Hall on

Bristo Square was presented to the university in 1897.

The

Students' Representative Council

{{Unreferenced, date=July 2014A students' representative council, also known as a students' administrative council, represents student interests in the government of a university, school or other educational institution. Generally the SRC forms par ...

(SRC) was founded in 1884 by student Robert Fitzroy Bell. In 1889, the SRC voted to establish Edinburgh University Union (EUU), to be housed in

Teviot Row House Teviot may refer to:

People

* Baron Teviot

* Earl of Teviot

Places

Australia

*Teviot, Queensland, a town in the Scenic Rim Region, Queensland

*Teviot Brook, a river in the Scenic Rim Region, Queensland

*Teviot Falls, Queensland

*Teviot Cr ...

on Bristo Square.

(EUSU) was founded in 1866, and

Edinburgh University Women's Union (renamed the Chambers Street Union in 1964) in October 1905. The SRC, EUU and Chambers Street Union merged to form

Edinburgh University Students' Association (EUSA) on 1 July 1973.

20th century

During

World War I, the Science and Medicine buildings had suffered from a lack of repairs or upgrades, which was exacerbated by an influx of students after the end of the war.

In 1919, the university bought the land of West Mains Farm in the south of the city for the development of a new satellite campus specialising in the sciences. On 6 July 1920, King

George V laid the foundation of the first new building (now called the

Joseph Black Building), housing the

Department of Chemistry

An academic department is a division of a university or school faculty devoted to a particular academic discipline. This article covers United States usage at the university level. In the United Kingdom and other Commonwealth countries, universi ...

.

The campus was named

King's Buildings in honour of George V.

New College on

The Mound was originally opened in 1846 as a

Free Church of Scotland Free Church of Scotland may refer to:

* Free Church of Scotland (1843–1900), seceded in 1843 from the Church of Scotland. The majority merged in 1900 into the United Free Church of Scotland; historical

* Free Church of Scotland (since 1900), rema ...

college, later of the

United Free Church of Scotland. Since the 1930s it has been the home of the School of Divinity. Prior to the 1929 reunion of the

Church of Scotland

The Church of Scotland ( sco, The Kirk o Scotland; gd, Eaglais na h-Alba) is the national church in Scotland.

The Church of Scotland was principally shaped by John Knox, in the Scottish Reformation, Reformation of 1560, when it split from t ...

, candidates for the ministry in the United Free Church studied at New College, whilst candidates for the Church of Scotland studied in the university's Faculty of Divinity. In 1935 the two institutions merged, with all operations moved to the New College site in Old Town. This freed up Old College for

Edinburgh Law School.

The

Polish School of Medicine

The Polish School of Medicine at the University of Edinburgh was established in March 1941. Initially, the idea was to meet the needs of the Polish Armed Forces for doctors but from the outstart, civilian students were admitted. Founded on the ...

was established in 1941 as a wartime academic initiative. While it was originally intended for students and doctors in the

Polish Armed Forces in the West, civilians were also allowed to take the courses, which were taught in Polish and awarded Polish medical degrees. When the school was closed in 1949, 336 students had matriculated, of which 227 students graduated with the equivalent of an

MBChB and a total of 19 doctors obtained a doctorate or

MD. A bronze plaque commemorating the Polish School of Medicine is located in the Quadrangle of the old Medical School in Teviot Place.

On 10 May 1951, the ''Royal (Dick) Veterinary College'', founded in 1823 by

William Dick, was reconstituted as the

Royal (Dick) School of Veterinary Studies and officially became part of the university. It achieved full faculty status as Faculty of Veterinary Medicine in 1964.

By the end of the 1950s, there were around 7,000 students matriculating annually, more than doubling the numbers from the turn of the century. The university addressed this partially through the redevelopment of

George Square, demolishing much of the area's historic houses and erecting modern buildings such as

40 George Square

40 George Square is a tower block in Edinburgh, Scotland forming part of the University of Edinburgh. Until September 2020 the tower was named David Hume Tower (often abbreviated as DHT). The building contains lecture theatres, teaching spaces, o ...

,

Appleton Tower

Appleton Tower is a tower block in Edinburgh, Scotland, owned by the University of Edinburgh.

History

When the University developed the George Square area in the 1960s, a large swathe of Georgian Edinburgh was demolished, leading to accusa ...

and the

Main Library.

On 1 August 1998, the ''Moray House Institute of Education'', founded in 1848, merged with the University of Edinburgh, becoming its Faculty of Education. Following the internal restructuring of the university in 2002, Moray House became known as the

Moray House School of Education.

It was renamed the Moray House School of Education and Sport in August 2019.

21st century

In the 1990s it became apparent that the old

Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh buildings in

Lauriston Place were no longer adequate for a modern teaching hospital.

Donald Dewar, the

Scottish Secretary at the time, authorized a joint project between private finance, local authorities, and the university to create a modern hospital and medical campus in the

Little France area of Edinburgh. The new campus was named the

BioQuarter

Edinburgh BioQuarter is one of the UK’s leading health innovation locations. It boasts an established and growing ecosystem where leaders in healthcare, academia, economic development and local government work together to deliver a shared vi ...

. The Chancellor's Building was opened on 12 August 2002 by

Prince Philip, housing the new

Edinburgh Medical School alongside the new Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh.

In 2007, the campus saw the addition of the

Euan MacDonald Centre as a research centre for

motor neuron diseases, which was part-funded by Scottish entrepreneur

Euan MacDonald and his father Donald. In August 2010, author

J. K. Rowling provided £10 million in funding to create the Anne Rowling Regenerative Neurology Clinic, which was officially opened in October 2013. The

Centre for Regenerative Medicine (CRM) is a

stem cell

In multicellular organisms, stem cells are undifferentiated or partially differentiated cells that can differentiate into various types of cells and proliferate indefinitely to produce more of the same stem cell. They are the earliest type o ...

research centre dedicated to the development of

regenerative treatments, which was opened in 2012. CRM is also home to applied scientists working with the

Scottish National Blood Transfusion Service (SNBTS) and Roslin Cells.

In December 2002, the

Edinburgh Cowgate Fire destroyed a number of university buildings, including some 3,000 m

2 of the

School of Informatics at 80

South Bridge. This was replaced with the

Informatics Forum on

Bristo Square, completed in July 2008. Also in 2002, the

Edinburgh Cancer Research Centre (ECRC) was opened on the

Western General Hospital site. In 2007, the

MRC Human Genetics Unit formed a partnership with the Centre for Genomic & Experimental Medicine and the ECRC to create the Institute of Genetics and Molecular Medicine (renamed the Institute of Genetics and Cancer in 2021) on the same site.

In April 2008, the

Roslin Institute – an

animal sciences research centre known for

cloning Dolly the sheep – became part of the Royal (Dick) School of Veterinary Studies. In 2011, the school moved into a new £60 million building on the Easter Bush campus, which now houses research and teaching facilities, and a hospital for small and farm animals.

Edinburgh College of Art

Edinburgh College of Art, founded in 1760, formally merged with the university's School of Arts, Culture and Environment on 1 August 2011. In 2014, the

Zhejiang University-University of Edinburgh Institute (ZJE) was founded as an international joint institute offering degrees in biomedical sciences, taught in English. The campus, located in

Haining,

Zhejiang Province

Zhejiang ( or , ; , also romanized as Chekiang) is an eastern, coastal province of the People's Republic of China. Its capital and largest city is Hangzhou, and other notable cities include Ningbo and Wenzhou. Zhejiang is bordered by Jiangs ...

,

China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, most populous country, with a Population of China, population exceeding 1.4 billion, slig ...

, was established on 15 March 2016.

The university began hosting a

Wikimedian in Residence

A Wikipedian in residence or Wikimedian in residence (WiR) is a Wikipedia editor, a Wikipedian (or Wikimedian), who accepts a placement with an institution, typically an art gallery, library, archive, museum, cultural institution, learned soci ...

in 2016. The residency was made into a full-time position in 2019, with the Wikimedian involved in teaching and learning activities within the scope of the

University of Edinburgh WikiProject.

In 2018, the University of Edinburgh was a signatory to the £1.3 billion ''Edinburgh and South East Scotland City Region Deal'', in partnership with the UK and Scottish governments, six local authorities and all universities and colleges in the region. The university committed to delivering a range of economic benefits to the region through the ''Data-Driven Innovation'' initiative. In conjunction with

Heriot-Watt University

Heriot-Watt University ( gd, Oilthigh Heriot-Watt) is a public research university based in Edinburgh, Scotland. It was established in 1821 as the School of Arts of Edinburgh, the world's first mechanics' institute, and subsequently granted univ ...

, the deal created five innovation hubs: the Bayes Centre, Edinburgh Futures Institute (EFI), Usher Institute, Easter Bush, and one further hub based at Heriot-Watt, the National Robotarium. The deal also included creation of the Edinburgh International Data Facility, which performs high-speed data processing in a secure environment.

In September 2020, the university completed work on the ''Richard Verney Health Centre'' at its central area campus on Bristo Square. The facility houses a health centre and pharmacy, and the university's disability and counselling services. The university's largest current expansion project is the conversion of some of the historic Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh buildings in Lauriston Place, which had been vacated in 2003 and partially developed into the

Quartermile. The £120 million renovations and extension will provide space for the ''Edinburgh Futures Institute'', an interdisciplinary hub linking arts, humanities, and social sciences with other disciplines in the research and teaching of 'complex futures'.

Historical links

Edinburgh has a number of historical links to other universities, chiefly through its influential Medical School and its graduates, who established and developed institutions elsewhere in the world.

*

College of William & Mary: the

second-oldest college in the US was founded in 1693 by Edinburgh graduate

James Blair, who served as the college's founding president for fifty years.

*

Columbia University

Columbia University (also known as Columbia, and officially as Columbia University in the City of New York) is a private research university in New York City. Established in 1754 as King's College on the grounds of Trinity Church in Manha ...

: had its

Medical School

A medical school is a tertiary educational institution, or part of such an institution, that teaches medicine, and awards a professional degree for physicians. Such medical degrees include the Bachelor of Medicine, Bachelor of Surgery (MBBS, M ...

founded by

Samuel Bard, an Edinburgh medical graduate.

*

Dalhousie University

Dalhousie University (commonly known as Dal) is a large public research university in Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia ( ; ; ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is one of the three Maritime provinces and one of the fou ...

: Edinburgh alumnus

George Ramsay

George Burrell Ramsay (4 March 1855 – 7 October 1935) was a Scottish footballer and manager.

Ramsay was the secretary and manager of Aston Villa Football Club during the club's 'Golden Age'. As a player he was the first Aston Villa captain ...

, the 22nd

Lieutenant Governor of Nova Scotia

The lieutenant governor of Nova Scotia () is the viceregal representative in Nova Scotia of the , who operates distinctly within the province but is also shared equally with the ten other jurisdictions of Canada, as well as the other Commonwealt ...

, wanted to establish a non-denominational college in

Halifax open to all. The school was modelled after the University of Edinburgh, which students could attend regardless of religion or nationality.

*

Dartmouth College: had its

School of Medicine founded by

Nathan Smith, an alumnus of Edinburgh Medical School.

*

Harvard University: had its

Medical School

A medical school is a tertiary educational institution, or part of such an institution, that teaches medicine, and awards a professional degree for physicians. Such medical degrees include the Bachelor of Medicine, Bachelor of Surgery (MBBS, M ...

founded by three surgeons, one of whom was

Benjamin Waterhouse

Benjamin Waterhouse (March 4, 1754, Newport, Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations – October 2, 1846, Cambridge, Massachusetts) was a physician, co-founder and professor of Harvard Medical School. He is most well known for being ...

, an alumnus of Edinburgh Medical School.

*

McGill University: had its

Faculty of Medicine

A medical school is a tertiary educational institution, or part of such an institution, that teaches medicine, and awards a professional degree for physicians. Such medical degrees include the Bachelor of Medicine, Bachelor of Surgery (MBBS, M ...

founded by four physicians, which included Edinburgh alumni

Andrew Fernando Holmes and

John Stephenson.

*

University of Pennsylvania: had its

School of Medicine founded by Edinburgh graduate

John Morgan, who modelled it after Edinburgh Medical School.

*

Princeton University: had its academic syllabus and structure reformed along the lines of the University of Edinburgh and other Scottish universities by its sixth president

John Witherspoon, an Edinburgh theology graduate.

*

University of Sydney: founded in 1850 by Sir

Charles Nicholson, a graduate of Edinburgh Medical School.

*

Yale University: had its

School of Medicine co-founded by

Nathan Smith, an alumnus of Edinburgh Medical School.

Campuses and buildings

The university has five main sites in Edinburgh:

* Central Area

* King's Buildings

* BioQuarter

* Easter Bush

* Western General

The university is responsible for several significant historic and modern buildings across the city, including

St Cecilia's Hall

St Cecilia's Hall is a small concert hall and museum in the city of Edinburgh, Scotland, in the United Kingdom. It is on the corner of Niddry Street and the Cowgate, about south of the Royal Mile. The hall dates from 1763 and was the first purp ...

, Scotland's oldest purpose-built

concert hall

A concert hall is a cultural building with a stage that serves as a performance venue and an auditorium filled with seats.

This list does not include other venues such as sports stadia, dramatic theatres or convention centres that may ...

and the second oldest in use in the

British Isles

The British Isles are a group of islands in the North Atlantic Ocean off the north-western coast of continental Europe, consisting of the islands of Great Britain, Ireland, the Isle of Man, the Inner and Outer Hebrides, the Northern Isles (O ...

; Teviot Row House, the oldest purpose-built

students' union

A students' union, also known by many other names, is a student organization present in many colleges, universities, and high schools. In higher education, the students' union is often accorded its own building on the campus, dedicated to social, ...

building in the world;

and the restored 17th-century Mylne's Court student residence at the head of the

Royal Mile

The Royal Mile () is a succession of streets forming the main thoroughfare of the Old Town of the city of Edinburgh in Scotland. The term was first used descriptively in W. M. Gilbert's ''Edinburgh in the Nineteenth Century'' (1901), des ...

.

Central Area

The Central Area is spread around numerous squares and streets in Edinburgh's ''Southside'', with some buildings in Old Town. It is the university's oldest area, occupied primarily by the College of Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences and the

School of Informatics. The highest concentration of university buildings is around

George Square, which includes

40 George Square

40 George Square is a tower block in Edinburgh, Scotland forming part of the University of Edinburgh. Until September 2020 the tower was named David Hume Tower (often abbreviated as DHT). The building contains lecture theatres, teaching spaces, o ...

(formerly David Hume Tower),

Appleton Tower

Appleton Tower is a tower block in Edinburgh, Scotland, owned by the University of Edinburgh.

History

When the University developed the George Square area in the 1960s, a large swathe of Georgian Edinburgh was demolished, leading to accusa ...

,

Main Library, and

Gordon Aikman Lecture Theatre, the area's largest lecture hall. Around nearby

Bristo Square lie the

Dugald Stewart Building,

Informatics Forum,

McEwan Hall,

Potterrow Student Centre,

Teviot Row House Teviot may refer to:

People

* Baron Teviot

* Earl of Teviot

Places

Australia

*Teviot, Queensland, a town in the Scenic Rim Region, Queensland

*Teviot Brook, a river in the Scenic Rim Region, Queensland

*Teviot Falls, Queensland

*Teviot Cr ...

, and

old Medical School, which still houses pre-clinical medical courses and biomedical sciences.

, one of

Edinburgh University Students' Association's main buildings, is located nearby, as is

Edinburgh College of Art in

Lauriston. North of George Square lies the university's

Old College housing

Edinburgh Law School,

New College on

The Mound housing the School of Divinity, and

St Cecilia's Hall

St Cecilia's Hall is a small concert hall and museum in the city of Edinburgh, Scotland, in the United Kingdom. It is on the corner of Niddry Street and the Cowgate, about south of the Royal Mile. The hall dates from 1763 and was the first purp ...

. Some of these buildings are used to host events during the

Edinburgh International Festival and the

Edinburgh Festival Fringe

The Edinburgh Festival Fringe (also referred to as The Fringe, Edinburgh Fringe, or Edinburgh Fringe Festival) is the world's largest arts and media festival, which in 2019 spanned 25 days and featured more than 59,600 performances of 3,841 dif ...

every summer.

Pollock Halls

Pollock Halls, adjoining

Holyrood Park to the east, is the university's largest residence hall for undergraduate students in their first year. The complex houses over 2,000 students during term time and consists of ten named buildings with communal green spaces between them. The two original buildings,

St Leonard's Hall

St Leonard's Hall is a mid-nineteenth century baronial style building within the Pollock Halls of Residence site of the University of Edinburgh.

The hall was designed by John Lessels, and built in 1869-1870 for Thomas Nelson Junior, of the Tho ...

and

Salisbury Green

Salisbury Green is an eighteenth-century house, on the Pollock Halls of Residence site of the University of Edinburgh.

Originally built around 1780 by Alexander Scott, it is one of the two original buildings on site, along with St Leonard's H ...

, were built in the 19th century, while the majority of Pollock Halls dates from the 1960s and early 2000s. Two of the older houses in Pollock Halls were demolished in 2002, and a new building, Chancellor's Court, was built in their place and opened in 2003. Self-catered flats elsewhere account for the majority of university-provided accommodation. The area also includes the John McIntyre Conference Centre opened in 2009, which is the university's premier conference space.

Holyrood

The Holyrood campus, just off the

Royal Mile

The Royal Mile () is a succession of streets forming the main thoroughfare of the Old Town of the city of Edinburgh in Scotland. The term was first used descriptively in W. M. Gilbert's ''Edinburgh in the Nineteenth Century'' (1901), des ...

, used to be the site for ''Moray House Institute for Education'' until it merged with the university on 1 August 1998.

The university has since extended this campus. The buildings include redeveloped and extended Sports Science, Physical Education and Leisure Management facilities at St Leonard's Land linked to the Sports Institute in the

Pleasance. The £80 million O'Shea Hall at Holyrood was named after the former principal of the university Sir

Timothy O'Shea and was opened by

Princess Anne in 2017, providing a living and social environment for postgraduate students. The Outreach Centre, Institute for Academic Development (University Services Group), and Edinburgh Centre for Professional Legal Studies are also located at Holyrood.

King's Buildings

The King's Buildings campus is located in the south of the city. Most of the Science and Engineering College's research and teaching activities take place at the campus, which occupies a 35-hectare site. It includes the

Alexander Graham Bell

Alexander Graham Bell (, born Alexander Bell; March 3, 1847 – August 2, 1922) was a Scottish-born inventor, scientist and engineer who is credited with patenting the first practical telephone. He also co-founded the American Telephone and Te ...

Building (for mobile phones and digital communications systems),

James Clerk Maxwell Building (the administrative and teaching centre of the

School of Physics and Astronomy and School of Mathematics),

Joseph Black Building (home to the

School of Chemistry),

Royal Observatory,

Swann Building (the Wellcome Trust Centre for Cell Biology),

Waddington Building (the Centre for Systems Biology at Edinburgh),

William Rankine Building (School of Engineering's Institute for Infrastructure and Environment), and others. Until 2012, the KB campus was served by three libraries: Darwin Library, James Clerk Maxwell Library, and Robertson Engineering and Science Library. These were replaced by the Noreen and Kenneth Murray Library opened for the academic year 2012/13. The campus also hosts the National e-Science Centre (NeSC),

Scotland's Rural College (SRUC), Scottish Institute for Enterprise (SIE), Scottish Microelectronics Centre (SMC), and Scottish Universities Environmental Research Centre (SUERC).

BioQuarter

The BioQuarter campus, based in the Little France area, is home to the majority of medical facilities of the university, alongside the Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh. The campus houses the Anne Rowling Regenerative Neurology Clinic,

Centre for Regenerative Medicine, Chancellor's Building,

Euan MacDonald Centre, and Queen's Medical Research Institute, which opened in 2005.

The Chancellor's Building has two large lecture theatres and a medical library connected to the Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh by a series of corridors.

Easter Bush

The Easter Bush campus, located seven miles south of the city, houses the Jeanne Marchig International Centre for Animal Welfare Education,

Roslin Institute, Royal (Dick) School of Veterinary Studies, and Veterinary Oncology and Imaging Centre.

The

Roslin Institute is an animal sciences research institute which is sponsored by

BBSRC. The Institute won international fame in 1996, when its researchers Sir

Ian Wilmut,

Keith Campbell and their colleagues created

Dolly the sheep, the first

mammal

Mammals () are a group of vertebrate animals constituting the class Mammalia (), characterized by the presence of mammary glands which in females produce milk for feeding (nursing) their young, a neocortex (a region of the brain), fur or ...

to be cloned from an adult cell. A year later

Polly and Molly were cloned, both sheep contained a human gene.

Western General

The Western General campus, in proximity to the

Western General Hospital, contains the Biomedical Research Facility, Edinburgh Clinical Research Facility, and Institute of Genetics and Cancer (formerly the Institute of Genetics and Molecular Medicine).

File:Appleton Tower (39773534912).jpg, Appleton Tower

Appleton Tower is a tower block in Edinburgh, Scotland, owned by the University of Edinburgh.

History

When the University developed the George Square area in the 1960s, a large swathe of Georgian Edinburgh was demolished, leading to accusa ...

File:Edinburgh Architecture - The University of Edinburgh Business School, Buccleuch Place (geograph 2458971).jpg, Business School

A business school is a university-level institution that confers degrees in business administration or management. A business school may also be referred to as school of management, management school, school of business administration, o ...

File:Centre for Regenerative Medicine, University of Edinburgh.jpg, Centre for Regenerative Medicine

File:Erskine Williamson Building.jpg, Erskine Williamson

Erskine Douglas Williamson (born 10 April 1886 in Edinburgh – 25 December 1923) was a Scottish geophysicist.

Life

Following degrees from the University of Edinburgh and a period on a Research Scholarship from the Carnegie Trust of Scotland, ...

Building, King's Buildings

File:Informatics Forum University of Edinburgh.JPG, Informatics Forum, School of Informatics

File:No Canter Today (geograph 6738087).jpg, Roslin Institute

File:Main Entrance, Edinburgh Royal Infirmary - geograph.org.uk - 432996.jpg, Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh, School of Medicine

File:Royal (Dick) School of Veterinary Studies Main Building.jpg, Royal (Dick) School of Veterinary Studies

Organisation and administration

Governance

In common with the other

ancient universities of Scotland, and in contrast to nearly all other pre-1992 universities which are established by

royal charters, the University of Edinburgh is constituted by the

Universities (Scotland) Acts 1858 to 1966. These acts provide for three major bodies in the governance of the university: the

University Court, the

General Council, and the

''Senatus Academicus''.

University Court

The University Court is the university's governing body and the

legal person of the university, chaired by the

rector

Rector (Latin for the member of a vessel's crew who steers) may refer to:

Style or title

*Rector (ecclesiastical), a cleric who functions as an administrative leader in some Christian denominations

*Rector (academia), a senior official in an edu ...

and consisting of the principal,

Lord Provost of Edinburgh, and of

Assessors appointed by the rector, chancellor,

Edinburgh Town Council

The politics of Edinburgh are expressed in the deliberations and decisions of the City of Edinburgh Council, in elections to the council, the Scottish Parliament and the UK Parliament.

Also, as Scotland's capital city, Edinburgh is host to th ...

, General Council, and ''Senatus Academicus''. By the Universities (Scotland) Act 1889, it is a body corporate, with perpetual succession and a common seal. All property belonging to the university at the passing of the Act was vested in the Court. The present powers of the Court are further defined in the Universities (Scotland) Act 1966, including the administration and management of the university's revenue and property, the regulation of staff salaries, and the establishment and composition of committees of its own members or others.

General Council

The General Council consists of

graduates

Graduation is the awarding of a diploma to a student by an educational institution. It may also refer to the ceremony that is associated with it. The date of the graduation ceremony is often called graduation day. The graduation ceremony is a ...

,

academic staff, current and former University Court members. It was established to ensure that graduates have a continuing voice in the management of the university. The Council is required to meet twice per year to consider matters affecting the wellbeing and prosperity of the university. The Universities (Scotland) Act 1966 gave the Council the power to consider draft ordinances and resolutions, to be presented with an

annual report

An annual report is a comprehensive report on a company's activities throughout the preceding year. Annual reports are intended to give shareholders and other interested people information about the company's activities and financial performance. ...

of the work and activities of the university, and to receive an audited

financial statement. The Council elects the chancellor of the university and three Assessors on the University Court.

''Senatus Academicus''

The ''Senatus Academicus'' is the university's supreme academic body, chaired by the principal and consisting of the professors, heads of departments, and a number of

readers,

lecturer

Lecturer is an List of academic ranks, academic rank within many universities, though the meaning of the term varies somewhat from country to country. It generally denotes an academic expert who is hired to teach on a full- or part-time basis. T ...

s and other teaching and research staff. The core function of the ''Senatus'' is to regulate and supervise the teaching and discipline of the university and to promote research. The ''Senatus'' elects four Assessors on the University Court. The ''Senatus'' meets three times per year, hosting a presentation and discussion session which is open to all members of staff at each meeting.

University officials

The university's three most significant officials are its chancellor, rector, and principal, whose rights and responsibilities are largely derived from the Universities (Scotland) Act 1858.

The office of

chancellor

Chancellor ( la, cancellarius) is a title of various official positions in the governments of many nations. The original chancellors were the of Roman courts of justice—ushers, who sat at the or lattice work screens of a basilica or law cou ...

serves as the titular head and highest office of the university. Their duties include conferring degrees and enhancing the profile and reputation of the university on national and global levels.

The chancellor is elected by the university's

General Council, and a person generally remains in the office for life. Previous chancellors include former

prime minister Arthur Balfour and novelist Sir

J. M. Barrie.

has held the position since March 2011 succeeding

Prince Philip.

She is also Patron of the university's Royal (Dick) School of Veterinary Studies.

The office of

rector

Rector (Latin for the member of a vessel's crew who steers) may refer to:

Style or title

*Rector (ecclesiastical), a cleric who functions as an administrative leader in some Christian denominations

*Rector (academia), a senior official in an edu ...

is elected every three years by the staff and matriculated students. The primary role of the rector is to preside at the University Court.

The rector also chairs meetings of the General Council in absence of the chancellor. They work closely with students and

Edinburgh University Students' Association. Previous rectors include

microbiologist

A microbiologist (from Ancient Greek, Greek ) is a scientist who studies microscopic life forms and processes. This includes study of the growth, interactions and characteristics of Microorganism, microscopic organisms such as bacteria, algae, f ...

Sir

Alexander Fleming

Sir Alexander Fleming (6 August 1881 – 11 March 1955) was a Scottish physician and microbiologist, best known for discovering the world's first broadly effective antibiotic substance, which he named penicillin. His discovery in 1928 of what ...

, and former Prime Ministers Sir

Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 Winston Churchill in the Second World War, dur ...

and

David Lloyd George. The current rector is human rights lawyer

Debora Kayembe

Debora Kayembe Buba (born in April 1975) is a Scottish human rights lawyer and political activist. She has served on the board of the Scottish Refugee Council, and is a member of the office of the prosecutor at the International Criminal Court an ...

, who has held the position since March 2021.

The

principal is responsible for the overall operation of the university in a

chief executive role.

The principal is formally nominated by the Curators of Patronage and appointed by the University Court. They are the President of the

''Senatus Academicus'' and a member of the University Court

''ex officio''.

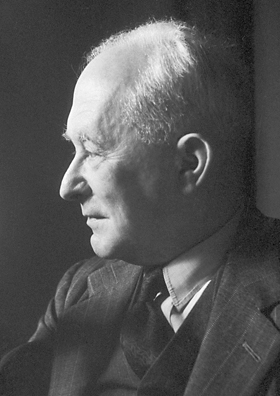

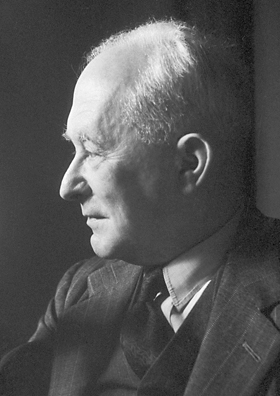

The principal is also automatically appointed vice-chancellor, in which role they confer degrees on behalf of the chancellor. Previous principals include physicist Sir

Edward Victor Appleton

Sir Edward Victor Appleton (6 September 1892 – 21 April 1965) was an English physicist, Nobel Prize winner (1947) and pioneer in radiophysics. He studied, and was also employed as a lab technician, at Bradford College from 1909 to 1911.

He w ...

and

religious philosopher Stewart Sutherland. The current principal is

nephrologist Peter Mathieson, who has held the position since February 2018.

Colleges and schools

In 2002, the university was reorganised from its nine

faculties into three 'Colleges'. While technically not a

collegiate university, it comprises the Colleges of Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences (CAHSS), Science & Engineering (CSE) and Medicine & Vet Medicine (CMVM). Within these colleges are 'Schools', which either represent one academic discipline such as Informatics or assemble adjacent academic disciplines such as the School of History, Classics and Archaeology. While bound by College-level policies, individual Schools can differ in their organisation and governance. As of 2021, the university has 21 schools in total.

Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences

The College took on its current name of Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences in 2016 after absorbing the Edinburgh College of Art in 2011. CAHSS offers more than 280 undergraduate degree programmes, 230 taught postgraduate programmes, and 200 research postgraduate programmes. Twenty subjects offered by the college were ranked within the top 10 nationally in the 2022 ''Complete University Guide''. It includes the oldest English Literature department in Britain,

which was ranked 7th globally in the 2021 ''

QS Rankings by Subject'' in English Language & Literature. The college hosts Scotland's

ESRC Doctoral Training Centre (DTC), the Scottish Graduate School of Social Science. The college is the largest of the three colleges by enrolment, with 26,130 students and 3,089 academic staff.

Medicine and Veterinary Medicine

Edinburgh Medical School was widely considered the best medical school in the English-speaking world throughout the 18th century and the first half of the 19th century and contributed significantly to the university's international reputation. Graduates of the medical school have founded medical schools and universities all over the world including 5 out of the 7

Ivy League medical schools (

Harvard

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of hig ...

,

Yale,

Columbia

Columbia may refer to:

* Columbia (personification), the historical female national personification of the United States, and a poetic name for America

Places North America Natural features

* Columbia Plateau, a geologic and geographic region in ...

,

Pennsylvania and

Dartmouth Dartmouth may refer to:

Places

* Dartmouth, Devon, England

** Dartmouth Harbour

* Dartmouth, Massachusetts, United States

* Dartmouth, Nova Scotia, Canada

* Dartmouth, Victoria, Australia

Institutions

* Dartmouth College, Ivy League university i ...

),

Vermont,

McGill,

Sydney

Sydney ( ) is the capital city of the state of New South Wales, and the most populous city in both Australia and Oceania. Located on Australia's east coast, the metropolis surrounds Sydney Harbour and extends about towards the Blue Mountain ...

,

Montréal, the

Royal Postgraduate Medical School (now part of

Imperial College London), the

Cape Town,

Birkbeck,

Middlesex Hospital and the

London School of Medicine for Women (both now part of

UCL).

In the 21st century, the reputation of the medical school has excelled; the school is associated with 13 Nobel Prize recipients: 7 recipients of the

Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine and 6 recipients of the

Nobel Prize in Chemistry. The medical school in 2022 was ranked 1st in the UK by the

Guardian

Guardian usually refers to:

* Legal guardian, a person with the authority and duty to care for the interests of another

* ''The Guardian'', a British daily newspaper

(The) Guardian(s) may also refer to:

Places

* Guardian, West Virginia, Unite ...

University Guide, In 2021, it was ranked third in the UK by

The Times University Guide, and the Complete University Guide. It also ranked 21st in the world by both the

Times Higher Education World University Rankings and the

QS World University Rankings in the same year.

The

Royal (Dick) School of Veterinary Studies is a world leader in veterinary education, research and practice. The eight original faculties formed four Faculty Groups in August 1992. Medicine and Veterinary Medicine became one of these, and in 2002 became the smallest of the three colleges, with 7,740 students and 1,896 academic staff.

The university's teaching hospitals include the

Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh,

Western General Hospital,

St John's Hospital, Livingston

St John's Hospital is the main general hospital in Livingston, West Lothian, Scotland. Located in the Howden area of the town, it serves Livingston and the wider West Lothian region. St John's is a teaching hospital for the University of Edinbur ...

,

Roodlands Hospital, and

Royal Hospital for Children and Young People.

Science and Engineering

In the 16th century, science was taught as "

natural philosophy" in the university. The 17th century saw the institution of the University Chairs of Mathematics and Botany, followed the next century by Chairs of Natural History, Astronomy, Chemistry and Agriculture. It was Edinburgh's professors who took a leading part in the formation of the

Royal Society of Edinburgh

The Royal Society of Edinburgh is Scotland's national academy of science and letters. It is a registered charity that operates on a wholly independent and non-partisan basis and provides public benefit throughout Scotland. It was established i ...

in 1783.

Joseph Black, Professor of Medicine and Chemistry at the time, founded the world's first Chemical Society in 1785.

The first named degrees of Bachelor and Doctor of Science was instituted in 1864, and a separate Faculty of Science was created in 1893 after three centuries of scientific advances at Edinburgh.

The

Regius Chair in Engineering was established in 1868, and the Regius Chair in Geology in 1871. In 1991 the Faculty of Science was renamed the Faculty of Science and Engineering, and in 2002 it became the College of Science and Engineering. The college has 11,745 students and 2,937 academic staff.

Sub-units, centres and institutes

Some subunits, centres and institutes within the university are listed as follows:

Academic profile

The university is a member of the

Russell Group of research-led British universities, and the ''

Sutton 13'' group of top-ranked universities in the UK. It is the only British university to be a member of both the

Coimbra Group and the

League of European Research Universities, and it is a founding member of

Una Europa and

Universitas 21, both international associations of research-intensive universities. The university maintains historically strong ties with the neighbouring

Heriot-Watt University

Heriot-Watt University ( gd, Oilthigh Heriot-Watt) is a public research university based in Edinburgh, Scotland. It was established in 1821 as the School of Arts of Edinburgh, the world's first mechanics' institute, and subsequently granted univ ...

for teaching and research. Edinburgh also offers a wide range of free online

MOOC

A massive open online course (MOOC ) or an open online course is an online course aimed at unlimited participation and open access via the Web. In addition to traditional course materials, such as filmed lectures, readings, and problem sets, m ...

courses on three global platforms

Coursera,

Edx and

FutureLearn

FutureLearn is a British digital education platform founded in December 2012. The company is jointly owned by The Open University and SEEK Ltd. It is a Massive Open Online Course (MOOC)ExpertTrack microcredential and Degree learning platform. ...

.

Admissions

In 2020, Edinburgh had the seventh-highest average entry standards amongst universities in the UK, with new undergraduates averaging 190

UCAS points

The UCAS Tariff (formerly called UCAS Points System) is used to allocate points to post-16 qualifications (Level 3 qualifications on the Regulated Qualifications Framework). Universities and colleges may use it when making offers to applicants. A p ...

, equivalent to just above AAAaa in

A-level

The A-Level (Advanced Level) is a subject-based qualification conferred as part of the General Certificate of Education, as well as a school leaving qualification offered by the educational bodies in the United Kingdom and the educational aut ...

grades.

It gave offers of admission to 52.3% of its 18 year old applicants in 2019, the fifth-lowest amongst the

Russell Group.

As the number of places available for Scottish and

EU students are capped by the

Scottish Government since students do not pay tuition fees, students applying from the rest of the UK and outside the EU have a higher likelihood of an offer. Excluding courses within

Edinburgh College of Art, the most competitive courses for Scottish/EU applicants in 2020 were International Relations, Oral Health Science, and Politics, Philosophy & Economics (PPE), with offer rates of 9%, 10% and 11%, respectively. In comparison, students from the rest of the UK have a 40% chance of receiving an offer for International Relations, while students from outside the EU have an 80% chance.

For the academic year 2019/20, 36.8% of Edinburgh's new undergraduates were

privately educated, the second-highest proportion among mainstream British universities, behind only

Oxford. As of August 2021, it has a higher proportion of female than male students with a male to female ratio of 38:62 in the undergraduate population, and the undergraduate student body is composed of 30% Scottish students, 32% from the rest of the UK, 10% from the EU, and 28% from outside the EU.

Graduation

At graduation ceremonies, graduates are being 'capped' with the ''Geneva bonnet'', which involves the university's principal tapping them on the head with the cap while they receive their graduation certificate.

The velvet-and-silk hat has been used for over 150 years, and legend says that it was originally made from cloth taken from the breeches of 16th-century scholars

John Knox

John Knox ( gd, Iain Cnocc) (born – 24 November 1572) was a Scottish minister, Reformed theologian, and writer who was a leader of the country's Reformation. He was the founder of the Presbyterian Church of Scotland.

Born in Giffordgat ...

or

George Buchanan. However, when the hat was last restored in the early 2000s, a label dated 1849 was discovered bearing the name of Edinburgh tailor Henry Banks, although some doubt remains whether he manufactured or restored the hat.

In 2006, a university emblem that had been taken into space by astronaut and Edinburgh graduate

Piers Sellers was incorporated into the ''Geneva bonnet''.

Library system

Pre-dating the university by three years, Edinburgh University Library was founded in 1580 through the donation of a large collection by Clement Litill, and today is the largest academic library collection in Scotland. The

Brutalist

Brutalist architecture is an architectural style that emerged during the 1950s in the United Kingdom, among the reconstruction projects of the post-war era. Brutalist buildings are characterised by Minimalism (art), minimalist constructions th ...

style eight-storey Main Library building in

George Square was designed by Sir

Basil Spence. At the time of its completion in 1967, it was the largest building of its type in the UK, and today is a

category A listed building. The library system also includes many specialised libraries at the college and school level.

Exchange programmes

The university offers students the opportunity to study in Europe and beyond via the

European Union

The European Union (EU) is a supranational political and economic union of member states that are located primarily in Europe. The union has a total area of and an estimated total population of about 447million. The EU has often been ...

's

Erasmus+ programme and a variety of international exchange agreements with around 300 partners institutions in nearly 40 countries worldwide.

University-wide exchanges are open to almost any student whose degree permits a year abroad and who can find a suitable course combination. The list of partner institutions is shown as follows (part of):

*

Asia-Pacific

Asia-Pacific (APAC) is the part of the world near the western Pacific Ocean. The Asia-Pacific region varies in area depending on context, but it generally includes East Asia, Russian Far East, South Asia, Southeast Asia, Australia and Pacific Isla ...

:

Fudan University,

University of Hong Kong,

University of Melbourne,

Seoul National University

Seoul National University (SNU; ) is a national public research university located in Seoul, South Korea. Founded in 1946, Seoul National University is largely considered the most prestigious university in South Korea; it is one of the three "S ...

,

University of Sydney,

National University of Singapore

The National University of Singapore (NUS) is a national public research university in Singapore. Founded in 1905 as the Straits Settlements and Federated Malay States Government Medical School, NUS is the oldest autonomous university in the c ...

,

Nanyang Technological University

The Nanyang Technological University (NTU) is a national research university in Singapore. It is the second oldest autonomous university in the country and is considered as one of the most prestigious universities in the world by various inte ...

*

Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a subcontinent of Eurasia and it is located enti ...

:

University of Amsterdam,

University of Copenhagen,

University of Helsinki,

Lund University,

Sciences Po

, motto_lang = fr

, mottoeng = Roots of the Future

, type = Public university, Public research university''Grande école''

, established =

, founder = Émile Boutmy

, a ...

,

University College Dublin,

Uppsala University

*

Latin America:

National Autonomous University of Mexico

The National Autonomous University of Mexico ( es, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, UNAM) is a public research university in Mexico. It is consistently ranked as one of the best universities in Latin America, where it's also the bigges ...

,

Pontifical Catholic University of Chile,

University of São Paulo

*

Northern America:

Boston College

Boston College (BC) is a private Jesuit research university in Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts. Founded in 1863, the university has more than 9,300 full-time undergraduates and nearly 5,000 graduate students. Although Boston College is classifie ...

,

Barnard College of Columbia University

Barnard College of Columbia University is a private women's liberal arts college in the borough of Manhattan in New York City. It was founded in 1889 by a group of women led by young student activist Annie Nathan Meyer, who petitioned Columbia U ...

,

University of California (except for

Merced and

San Francisco),

Caltech,

University of Chicago,

Cornell University

Cornell University is a private statutory land-grant research university based in Ithaca, New York. It is a member of the Ivy League. Founded in 1865 by Ezra Cornell and Andrew Dickson White, Cornell was founded with the intention to ...

,

Georgetown University,

McGill University,

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill,

University of Pennsylvania,

University of Texas at Austin,

University of Toronto,

University of Virginia,

Washington University in St. Louis

Subject-specific exchanges are open to students studying in particular schools or subject areas, including exchange programmes with

Carnegie Mellon University

Carnegie Mellon University (CMU) is a private research university in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. One of its predecessors was established in 1900 by Andrew Carnegie as the Carnegie Technical Schools; it became the Carnegie Institute of Technology ...

,

Emory University,

EPFL,

ETH Zurich

(colloquially)

, former_name = eidgenössische polytechnische Schule

, image = ETHZ.JPG

, image_size =

, established =

, type = Public

, budget = CHF 1.896 billion (2021)

, rector = Günther Dissertori

, president = Joël Mesot

, ac ...

,

ESSEC Business School,

ENS Paris,

HEC Paris

HEC Paris (french: École des hautes études commerciales de Paris) is a business school, and one of the most prestigious and selective grandes écoles, located in Jouy-en-Josas, France. HEC offers Master in Management, MSc International Fi ...

,

Humboldt University of Berlin

The Humboldt University of Berlin (german: link=no, Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, abbreviated HU Berlin) is a public university, public research university in the central borough of Mitte in Berlin, Germany.

The university was established ...

,

Karolinska Institute,

Kyoto University

, mottoeng = Freedom of academic culture

, established =

, type = National university, Public (National)

, endowment = ¥ 316 billion (2.4 1000000000 (number), billion USD)

, faculty = 3,480 (Teaching Staff)

, administrative_staff ...

,

LMU Munich,

University of Michigan,

Peking University

Peking University (PKU; ) is a public research university in Beijing, China. The university is funded by the Ministry of Education.

Peking University was established as the Imperial University of Peking in 1898 when it received its royal charter ...

,

Rhode Island School of Design,

Sorbonne University,

TU München

The Technical University of Munich (TUM or TU Munich; german: Technische Universität München) is a public research university in Munich, Germany. It specializes in engineering, technology, medicine, and applied and natural sciences.

Establis ...

,

Waseda University,

Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania, and others.

Rankings and reputation

In the 2021

Research Excellence Framework (REF), which evaluated work produced between 2014 and 2021, Edinburgh ranked 4th by research power and 15th by GPA amongst British universities. The university fell four places in GPA when compared to the 2014 REF, but retained its place in research power. 90 per cent of the university's research activity was judged to be 'world leading' (4*) or 'internationally excellent' (3*), and five departments – Computer Science, Informatics, Sociology, Anthropology, and Development Studies – were ranked as the best in the UK.

In the 2015 ''THE Global Employability University Ranking'', Edinburgh ranked 23rd in the world and 4th in the UK for graduate employability as voted by international recruiters. A 2015 government report found that Edinburgh was one of only two Scottish universities (along with

St Andrews

St Andrews ( la, S. Andrea(s); sco, Saunt Aundraes; gd, Cill Rìmhinn) is a town on the east coast of Fife in Scotland, southeast of Dundee and northeast of Edinburgh. St Andrews had a recorded population of 16,800 , making it Fife's fou ...

) that some London-based elite recruitment firms considered applicants from, especially in the field of financial services and investment banking. When ''

The New York Times'' ranked universities based on the employability of graduates as evaluated by recruiters from top companies in 20 countries in 2012, Edinburgh was placed at 42nd in the world and 7th in Britain.

Edinburgh was ranked 24th in the world and 5th in the UK by the 2021

''Aggregate Ranking of Top Universities'', a league table based on the three major world university rankings,

''ARWU'',

''QS'' and

''THE''.

In the 2022

''U.S. News & World Report'', Edinburgh ranked 32nd globally and 5th nationally. The 2021

''World Reputation Rankings'' placed Edinburgh at 30th worldwide and 6th nationwide.

In 2021, it ranked 63rd amongst the universities around the world by the ''

SCImago Institutions Rankings''.

The noticeable disparity between Edinburgh's research capacity,

endowment

Endowment most often refers to:

*A term for human penis size

It may also refer to: Finance

*Financial endowment, pertaining to funds or property donated to institutions or individuals (e.g., college endowment)

*Endowment mortgage, a mortgage to b ...

and international status on the one hand, and its ranking in national league tables on the other, is largely due to the impact of measures of 'student satisfaction'. Edinburgh was ranked last in the UK for teaching quality in the 2012

National Student Survey, with the 2015 ''

Good University Guide

Three national rankings of universities in the United Kingdom are published annually – by ''The Complete University Guide'', ''The Guardian'' and jointly by ''The Times'' and ''The Sunday Times''. Rankings have also been produced in the past ...

'' stating that this stemmed from "questions to do with the promptness, usefulness and extent of academic feedback", and that the university "still has a long way to go to turn around a poor position". Edinburgh improved only marginally over the next years, with the 2021 ''Good University Guide'' still ranking it in the bottom 10 domestically in both teaching quality and student experience. Edinburgh was ranked 122nd out of 128 universities for student satisfaction in the 2022 ''

Complete University Guide'', although it was ranked 12th overall.

The 2022 ''

Guardian University Guide'' ranked Edinburgh 12th overall, but 101st out of 119 universities in course satisfaction, and lowest among all universities in satisfaction with feedback.