DRC Admin Level 1 2 on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), also known as the DR Congo, Congo-Kinshasa, or simply the Congo (the last ambiguously also referring to the neighbouring

BBC News website

Retrieved 9 December 2017. the nation is a prominent example of the " resource curse". Besides the capital Kinshasa, the two next largest cities,

Belgian exploration and administration took place from the 1870s until the 1920s. It was first led by

Belgian exploration and administration took place from the 1870s until the 1920s. It was first led by

''The Congo Free State – a colony of gross excess''.

September 2004. In a succession of negotiations, Leopold, professing humanitarian objectives in his capacity as chairman of the King Leopold formally acquired rights to the Congo territory at the Conference of Berlin in 1885 and made the land his private property. He named it the

King Leopold formally acquired rights to the Congo territory at the Conference of Berlin in 1885 and made the land his private property. He named it the

The Cambridge history of Africa: From the earliest times to c. 500 BC

,

The transition from the Congo Free State to the Belgian Congo was a break, but it also featured a large degree of continuity. The last governor-general of the Congo Free State, Baron

The transition from the Congo Free State to the Belgian Congo was a break, but it also featured a large degree of continuity. The last governor-general of the Congo Free State, Baron

In May 1960, a growing nationalist movement, the

In May 1960, a growing nationalist movement, the

Mobutu had the staunch support of the United States because of his opposition to communism; the U.S. believed that his administration would serve as an effective counter to communist movements in Africa. A

Mobutu had the staunch support of the United States because of his opposition to communism; the U.S. believed that his administration would serve as an effective counter to communist movements in Africa. A  In a campaign to identify himself with African nationalism, starting on 1 June 1966, Mobutu renamed the nation's cities: Léopoldville became Kinshasa (the country was known as Congo-Kinshasa), Stanleyville became

In a campaign to identify himself with African nationalism, starting on 1 June 1966, Mobutu renamed the nation's cities: Léopoldville became Kinshasa (the country was known as Congo-Kinshasa), Stanleyville became

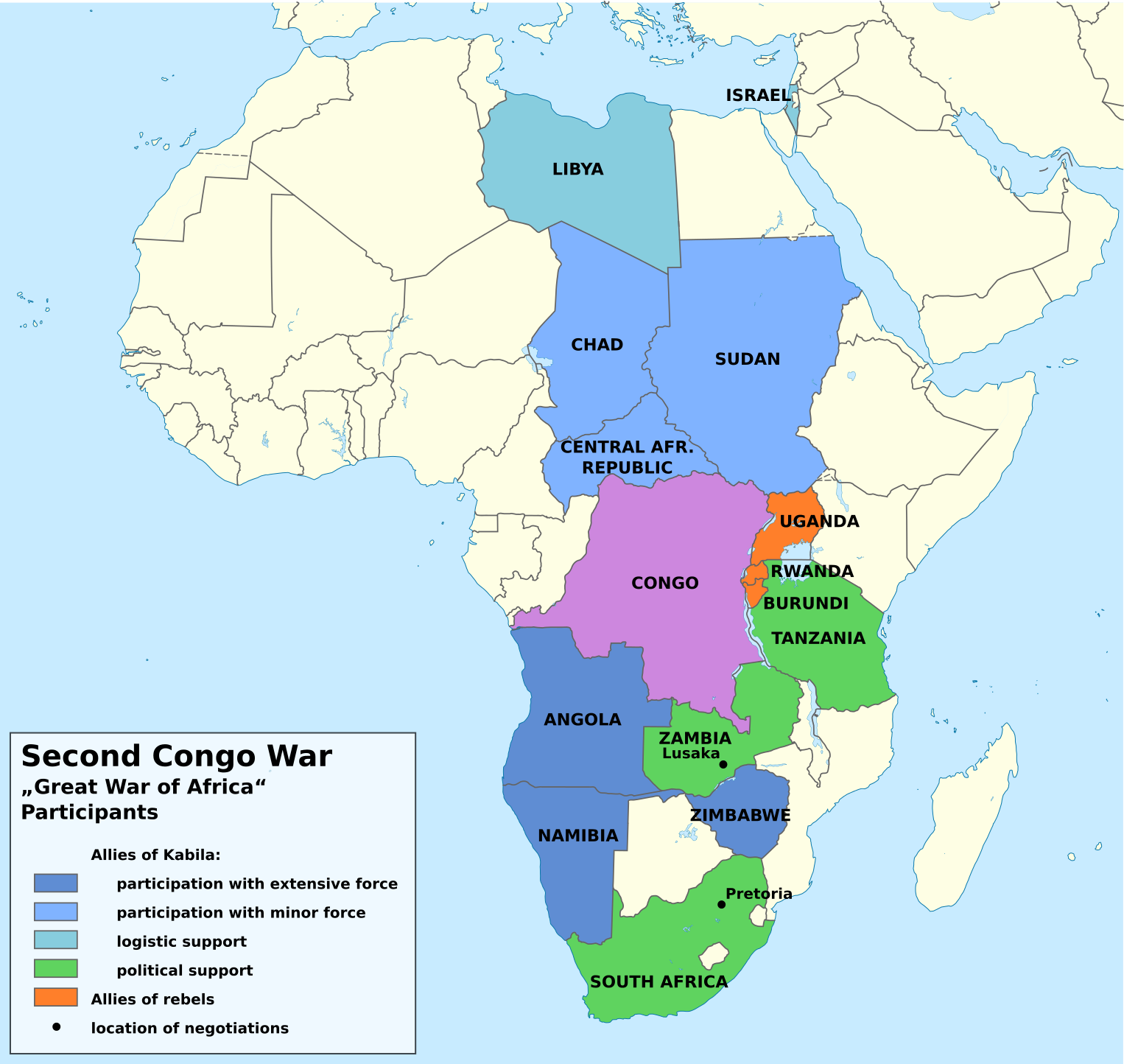

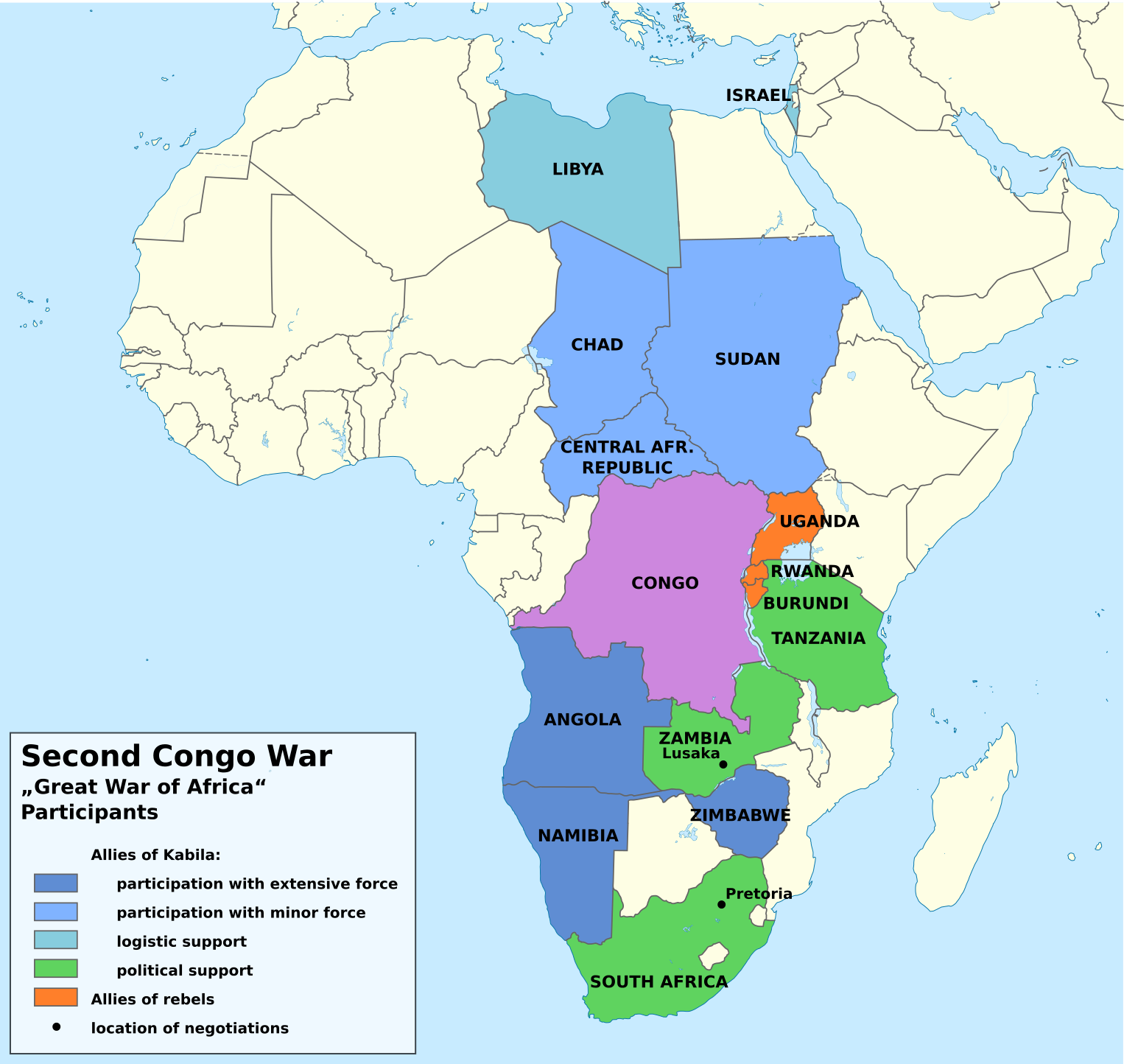

By 1996, following the

By 1996, following the

The DRC is located in central

The DRC is located in central

The global growth in demand for scarce raw materials and the industrial surges in China, India, Russia, Brazil and other

The global growth in demand for scarce raw materials and the industrial surges in China, India, Russia, Brazil and other

The International Criminal Court investigation in the Democratic Republic of the Congo was initiated by Kabila in April 2004. The International Criminal Court prosecutor opened the case in June 2004. Children in the military, Child soldiers have been used on a large scale in DRC, and in 2011 it was estimated that 30,000 children were still operating with armed groups. Instances of child labor and Forced labour, forced labor have been observed and reported in the United States Department of Labor, U.S. Department of Labor's ''Findings on the Worst Forms of Child Labor'' in the DRC in 2013 and six goods produced by the country's mining industry appear on the department's December 2014 ''List of Goods Produced by Child Labor or Forced Labor''.

The Democratic Republic of the Congo has prohibited same-sex marriage since 2006, and attitudes towards the LGBT rights in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, LGBT community are generally negative throughout the nation.

Violence against women is perceived by large sectors of society to be normal.

The United Nations Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women, Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women in 2006 expressed concern that in the post-war transition period, the promotion of women's human rights and gender equality is not seen as a priority. Mass rapes, sexual violence and sexual slavery are used as a weapon of war by the Armed Forces of the Democratic Republic of the Congo and armed groups in the eastern part of the country. The eastern part of the country in particular has been described as the "rape capital of the world" and the prevalence of sexual violence there described as the worst in the world.

The prevalence of Female genital mutilation is estimated at 5% of women and is illegal.

The International Criminal Court investigation in the Democratic Republic of the Congo was initiated by Kabila in April 2004. The International Criminal Court prosecutor opened the case in June 2004. Children in the military, Child soldiers have been used on a large scale in DRC, and in 2011 it was estimated that 30,000 children were still operating with armed groups. Instances of child labor and Forced labour, forced labor have been observed and reported in the United States Department of Labor, U.S. Department of Labor's ''Findings on the Worst Forms of Child Labor'' in the DRC in 2013 and six goods produced by the country's mining industry appear on the department's December 2014 ''List of Goods Produced by Child Labor or Forced Labor''.

The Democratic Republic of the Congo has prohibited same-sex marriage since 2006, and attitudes towards the LGBT rights in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, LGBT community are generally negative throughout the nation.

Violence against women is perceived by large sectors of society to be normal.

The United Nations Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women, Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women in 2006 expressed concern that in the post-war transition period, the promotion of women's human rights and gender equality is not seen as a priority. Mass rapes, sexual violence and sexual slavery are used as a weapon of war by the Armed Forces of the Democratic Republic of the Congo and armed groups in the eastern part of the country. The eastern part of the country in particular has been described as the "rape capital of the world" and the prevalence of sexual violence there described as the worst in the world.

The prevalence of Female genital mutilation is estimated at 5% of women and is illegal.

The economy of the DR Congo has grown from US$9.02 billion at the end of the Second Congo War in 2003 to US$72.48 billion in 2024 by List of countries by GDP (nominal), nominal GDP, and from International dollar, $29.23 billion to $190.13 billion by List of countries by GDP (PPP), PPP-adjusted GDP during the same time period. Minerals and metal, specifically

The economy of the DR Congo has grown from US$9.02 billion at the end of the Second Congo War in 2003 to US$72.48 billion in 2024 by List of countries by GDP (nominal), nominal GDP, and from International dollar, $29.23 billion to $190.13 billion by List of countries by GDP (PPP), PPP-adjusted GDP during the same time period. Minerals and metal, specifically

Smaller-scale economic activity from artisanal mining occurs in the Informal economy, informal sector and is not reflected in GDP data. A third of the DRC's diamonds are believed to be smuggled out of the country, making it difficult to quantify diamond production levels."Ranking Of The World's Diamond Mines By Estimated 2013 Production"

Smaller-scale economic activity from artisanal mining occurs in the Informal economy, informal sector and is not reflected in GDP data. A third of the DRC's diamonds are believed to be smuggled out of the country, making it difficult to quantify diamond production levels."Ranking Of The World's Diamond Mines By Estimated 2013 Production"

, ''Kitco'', 20 August 2013. In 2002, tin was discovered in the east of the country but to date has only been mined on a small scale. Smuggling of Conflict resource, conflict minerals such as coltan and cassiterite, ores of tantalum and tin, respectively, helped to fuel the war in the eastern Congo. Open-pit cobalt mining has led to Deforestation in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, deforestation and habitat destruction. Katanga Mining, Katanga Mining Limited, a Swiss-owned company, owns the Luilu Metallurgical Plant, which has a capacity of 175,000 tonnes of copper and 8,000 tonnes of cobalt per year, making it the largest cobalt refinery in the world. After a major rehabilitation program, the company resumed copper production operations in December 2007 and cobalt production in May 2008. During 2007–08, Joseph Kabila's administration entered a 'resources-for-infrastructure' deal with China, creating the joint venture Sicomines (''Sino-Congolais des Mines''), with the majority of the shares owned by the China Railway Engineering Corporation (CREC) while the DRC's Gécamines owned the rest. The company received mining rights in exchanged for investing US$3 billion into building infrastructure. Sicomines began production in 2015. The deal has received criticized for terms that appeared to be disproportionately favorable to China at the expense of the DRC. Félix Tshisekedi's administration ordered an investigation into the deal, which concluded that less than US$1 billion had been spent on infrastructure. Tshisekedi renegotiated the agreement to add new terms, and in 2024 this led to the infrastructure investment being increased to US$7 billion. In April 2013, anti-corruption NGOs revealed that Congolese tax authorities had failed to account for $88 million from the mining sector, despite booming production and positive industrial performance. The missing funds date from 2010 and tax bodies should have paid them into the central bank. Later in 2013, the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative suspended the country's candidacy for membership due to insufficient reporting, monitoring and independent audits, but in July 2013 the country improved its accounting and transparency practices to the point where the EITI gave the country full membership.

The DRC has of roads, out of which only are paved. It also has of railways, with most being narrow-gauge railway, narrow-gauge. The infrastructure is in a state of disrepair, and the national highway system is very limited; reaching the capital by road is not possible from many parts of the country. Since the early 2000s there have been improvements to the road network, but the dense forests and numerous rivers in the DRC make construction and maintenance difficult. Air and river transportation have an important role, due to the terrain and the poor state of the road and rail networks. Air travel has seen an increase since the early 2000s, with 24 city pairs having airline service as of 2007, although it has a poor safety record. All air carriers certified by the DRC have been banned from European Union airports because of inadequate safety standards. Despite this, airlines are seen as the most reliable form of domestic travel. There are eight airlines in the country, including the flag carrier Congo Airways, and several international airlines service N'djili Airport, Kinshasa's international airport. Besides Kinshasa there are three other international airports in the DRC, which are at Lubumbashi International Airport, Lubumbashi, Kisangani Bangoka International Airport, Kisangani, and Goma International Airport, Goma.

The DRC has about of navigable waterways, with the Congo River serving as the spine. Water transport has traditionally been the dominant means of moving around in the DRC and is also used to fill gaps between roads. Around two million tons of cargo pass through the port of Kinshasa on the Congo River every year, more than triple the volume moved by the national railroad company, ''Société nationale des chemins de fer du Congo'' (SNCC). River transports are owned by many private operators. The country's three economic hubs—Kinshasa in the west, Lubumbashi in the south, and Kinsangani in the northeast—are not connected by roads or rail. The rail system is concentrated in the southeast, and Kinshasa is connected by river ferry to Ilebo, where the rail line to Lubumbashi begins. This line is also critical for the movement of metal and minerals from the southern DRC to ports in Angola or South Africa (via Zambia) to be exported overseas. There is an electrified line between Kinshasa and the Atlantic seaport of Matadi. The track and rolling stock of the SNCC system is in poor condition, though the more recently built Matadi–Kinshasa line has better track.

There are 44 List of roads in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, national roads with a total of , but three of them are considered the most important. National Road 1 (Democratic Republic of the Congo), National Road No. 1 (RN1) is the main highway of the road system, connecting seaports in Kongo Central with Kinshasa and cities in the interior, such as Lubumbashi. RN1 reaches the border with Zambia in the south. National Road 2 (Democratic Republic of the Congo), National Road 2 (RN2) connects the central city of Mbuji-Mayi with Goma in the east, with most of it outside of the Kivu region being in a bad condition, and National Road 3 (Democratic Republic of the Congo), National Road 3 (RN3) connects Goma to Kisangani, from where a river boat can be taken to Kinshasa.

The DRC has of roads, out of which only are paved. It also has of railways, with most being narrow-gauge railway, narrow-gauge. The infrastructure is in a state of disrepair, and the national highway system is very limited; reaching the capital by road is not possible from many parts of the country. Since the early 2000s there have been improvements to the road network, but the dense forests and numerous rivers in the DRC make construction and maintenance difficult. Air and river transportation have an important role, due to the terrain and the poor state of the road and rail networks. Air travel has seen an increase since the early 2000s, with 24 city pairs having airline service as of 2007, although it has a poor safety record. All air carriers certified by the DRC have been banned from European Union airports because of inadequate safety standards. Despite this, airlines are seen as the most reliable form of domestic travel. There are eight airlines in the country, including the flag carrier Congo Airways, and several international airlines service N'djili Airport, Kinshasa's international airport. Besides Kinshasa there are three other international airports in the DRC, which are at Lubumbashi International Airport, Lubumbashi, Kisangani Bangoka International Airport, Kisangani, and Goma International Airport, Goma.

The DRC has about of navigable waterways, with the Congo River serving as the spine. Water transport has traditionally been the dominant means of moving around in the DRC and is also used to fill gaps between roads. Around two million tons of cargo pass through the port of Kinshasa on the Congo River every year, more than triple the volume moved by the national railroad company, ''Société nationale des chemins de fer du Congo'' (SNCC). River transports are owned by many private operators. The country's three economic hubs—Kinshasa in the west, Lubumbashi in the south, and Kinsangani in the northeast—are not connected by roads or rail. The rail system is concentrated in the southeast, and Kinshasa is connected by river ferry to Ilebo, where the rail line to Lubumbashi begins. This line is also critical for the movement of metal and minerals from the southern DRC to ports in Angola or South Africa (via Zambia) to be exported overseas. There is an electrified line between Kinshasa and the Atlantic seaport of Matadi. The track and rolling stock of the SNCC system is in poor condition, though the more recently built Matadi–Kinshasa line has better track.

There are 44 List of roads in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, national roads with a total of , but three of them are considered the most important. National Road 1 (Democratic Republic of the Congo), National Road No. 1 (RN1) is the main highway of the road system, connecting seaports in Kongo Central with Kinshasa and cities in the interior, such as Lubumbashi. RN1 reaches the border with Zambia in the south. National Road 2 (Democratic Republic of the Congo), National Road 2 (RN2) connects the central city of Mbuji-Mayi with Goma in the east, with most of it outside of the Kivu region being in a bad condition, and National Road 3 (Democratic Republic of the Congo), National Road 3 (RN3) connects Goma to Kisangani, from where a river boat can be taken to Kinshasa.

The The World Factbook, CIA World Factbook estimated the population to be over 115 million as of 2024. Between 1950 and 2000, the country's population nearly quadrupled from 12.2 million to 46.9 million. Since 2000, it has maintained a high growth rate of about 3–3.5% per year, growing from 47 million to an estimated 112 million.

The The World Factbook, CIA World Factbook estimated the population to be over 115 million as of 2024. Between 1950 and 2000, the country's population nearly quadrupled from 12.2 million to 46.9 million. Since 2000, it has maintained a high growth rate of about 3–3.5% per year, growing from 47 million to an estimated 112 million.

*Luba-Kasai language, Luba-Kasaï

*Kongo people, Kongo

*Mongo people, Mongo

*Luba-Katanga language, Lubakat

*Lulua people, Lulua

*Tetela people, Tetela

*Nande language, Nande

*Ngbandi people, Ngbandi

*Ngombe language, Ngombe

*Yaka people, Yaka

*Ngbaka languages, Ngbaka

In , the UN estimated the country's population to be million, a rapid increase from 39.1 million in 1992 despite the ongoing war. As many as 250 ethnic groups have been identified and named. About 600,000 Congo Pygmies, Pygmies live in the DRC.

*Luba-Kasai language, Luba-Kasaï

*Kongo people, Kongo

*Mongo people, Mongo

*Luba-Katanga language, Lubakat

*Lulua people, Lulua

*Tetela people, Tetela

*Nande language, Nande

*Ngbandi people, Ngbandi

*Ngombe language, Ngombe

*Yaka people, Yaka

*Ngbaka languages, Ngbaka

In , the UN estimated the country's population to be million, a rapid increase from 39.1 million in 1992 despite the ongoing war. As many as 250 ethnic groups have been identified and named. About 600,000 Congo Pygmies, Pygmies live in the DRC.

Christianity is the predominant religion of the DRC. A 2013–14 survey, conducted by the Demographic and Health Surveys Program in 2013–2014 indicated that Christians constituted 93.7% of the population (with Catholics making up 29.7%, Protestants 26.8%, and other Christians 37.2%). A new Christian religious movement, Kimbanguism, had the adherence of 2.8%, while Muslims made up 1%. Other recent estimates have found Christianity the majority religion, followed by 95.8% of the population according to a 2010 Pew Research Center estimate, while the CIA World Factbook reports this figure to be 95.9%. The proportion of followers of Islam is variously estimated from 1% to 12%.

There are about 35 million Catholics in the country with six archdioceses and 41 dioceses. The impact of the Catholic Church is difficult to overestimate. Schatzberg has called it the country's "only truly national institution apart from the state." Its schools have educated over 60% of the nation's primary school students and more than 40% of its secondary students. The church owns and manages an extensive network of hospitals, schools, and clinics, as well as many diocesan economic enterprises, including farms, ranches, stores, and artisans' shops.

Sixty-two Protestant denominations are federated under the umbrella of the Church of Christ in the Congo. It is often referred to as ''the Protestant Church'', since it covers most of the DRC Protestants. With more than 25 million members, it constitutes List of the largest Protestant denominations, one of the largest Protestant bodies in the world.

Kimbanguism was seen as a threat to the colonial regime and was banned by the Belgians. Kimbanguism, officially "the church of Christ on Earth by the prophet Simon Kimbangu", has about three million members, Sources quoted are ''The World Factbook'' (1998), 'official government web site' of ''Democratic Republic of Congo''. Retrieved 25 May 2007. primarily among the Bakongo of Kongo Central and Kinshasa.

Islam has been present in the Democratic Republic of the Congo since the 18th century, when Arab traders from East Africa pushed into the interior for ivory- and slave-trading purposes. Today, Muslims constitute approximately 1% of the Congolese population according to the Pew Research Center. The majority are Sunni Islam, Sunni Muslims.

Christianity is the predominant religion of the DRC. A 2013–14 survey, conducted by the Demographic and Health Surveys Program in 2013–2014 indicated that Christians constituted 93.7% of the population (with Catholics making up 29.7%, Protestants 26.8%, and other Christians 37.2%). A new Christian religious movement, Kimbanguism, had the adherence of 2.8%, while Muslims made up 1%. Other recent estimates have found Christianity the majority religion, followed by 95.8% of the population according to a 2010 Pew Research Center estimate, while the CIA World Factbook reports this figure to be 95.9%. The proportion of followers of Islam is variously estimated from 1% to 12%.

There are about 35 million Catholics in the country with six archdioceses and 41 dioceses. The impact of the Catholic Church is difficult to overestimate. Schatzberg has called it the country's "only truly national institution apart from the state." Its schools have educated over 60% of the nation's primary school students and more than 40% of its secondary students. The church owns and manages an extensive network of hospitals, schools, and clinics, as well as many diocesan economic enterprises, including farms, ranches, stores, and artisans' shops.

Sixty-two Protestant denominations are federated under the umbrella of the Church of Christ in the Congo. It is often referred to as ''the Protestant Church'', since it covers most of the DRC Protestants. With more than 25 million members, it constitutes List of the largest Protestant denominations, one of the largest Protestant bodies in the world.

Kimbanguism was seen as a threat to the colonial regime and was banned by the Belgians. Kimbanguism, officially "the church of Christ on Earth by the prophet Simon Kimbangu", has about three million members, Sources quoted are ''The World Factbook'' (1998), 'official government web site' of ''Democratic Republic of Congo''. Retrieved 25 May 2007. primarily among the Bakongo of Kongo Central and Kinshasa.

Islam has been present in the Democratic Republic of the Congo since the 18th century, when Arab traders from East Africa pushed into the interior for ivory- and slave-trading purposes. Today, Muslims constitute approximately 1% of the Congolese population according to the Pew Research Center. The majority are Sunni Islam, Sunni Muslims.

The first members of the Baháʼí Faith to live in the country came from Uganda in 1953. Four years later, the first local administrative council was elected. In 1970, the National Spiritual Assembly (national administrative council) was first elected. Though the religion was banned in the 1970s and 1980s, due to misrepresentations of foreign governments, the ban was lifted by the end of the 1980s. In 2012, plans were announced to build a national Baháʼí House of Worship in the country.

Traditional religions embody such concepts as monotheism, animism, vitalism, spirit worship, spirit and ancestor worship, witchcraft, and sorcery and vary widely among ethnic groups. The syncretic sects often merge elements of Christianity with traditional beliefs and rituals and are not recognized by mainstream churches as part of Christianity. New variants of ancient beliefs have become widespread, led by US-inspired Pentecostal churches which have been in the forefront of witchcraft accusations, particularly against children and the elderly. Children accused of witchcraft are sent away from homes and family, often to live on the street, which can lead to physical violence against these children. There are charities supporting street children such as the Congo Children Trust. The Congo Children Trust's flagship project is Kimbilio, which works to reunite street children in

The first members of the Baháʼí Faith to live in the country came from Uganda in 1953. Four years later, the first local administrative council was elected. In 1970, the National Spiritual Assembly (national administrative council) was first elected. Though the religion was banned in the 1970s and 1980s, due to misrepresentations of foreign governments, the ban was lifted by the end of the 1980s. In 2012, plans were announced to build a national Baháʼí House of Worship in the country.

Traditional religions embody such concepts as monotheism, animism, vitalism, spirit worship, spirit and ancestor worship, witchcraft, and sorcery and vary widely among ethnic groups. The syncretic sects often merge elements of Christianity with traditional beliefs and rituals and are not recognized by mainstream churches as part of Christianity. New variants of ancient beliefs have become widespread, led by US-inspired Pentecostal churches which have been in the forefront of witchcraft accusations, particularly against children and the elderly. Children accused of witchcraft are sent away from homes and family, often to live on the street, which can lead to physical violence against these children. There are charities supporting street children such as the Congo Children Trust. The Congo Children Trust's flagship project is Kimbilio, which works to reunite street children in

In 2014, the literacy rate for the population between the ages of 15 and 49 was estimated to be 75.9% (88.1% male and 63.8% female) according to a Demographic and Health Surveys, DHS nationwide survey. The education system is governed by three government ministries: the ''Ministère de l'Enseignement Primaire, Secondaire et Professionnel (MEPSP''), the ''Ministère de l'Enseignement Supérieur et Universitaire (MESU)'' and the ''Ministère des Affaires Sociales (MAS)''. Primary education is neither free nor compulsory, even though the Congolese constitution says it should be (Article 43 of the 2005 Congolese Constitution).

As a result of the First Congo War, First and

In 2014, the literacy rate for the population between the ages of 15 and 49 was estimated to be 75.9% (88.1% male and 63.8% female) according to a Demographic and Health Surveys, DHS nationwide survey. The education system is governed by three government ministries: the ''Ministère de l'Enseignement Primaire, Secondaire et Professionnel (MEPSP''), the ''Ministère de l'Enseignement Supérieur et Universitaire (MESU)'' and the ''Ministère des Affaires Sociales (MAS)''. Primary education is neither free nor compulsory, even though the Congolese constitution says it should be (Article 43 of the 2005 Congolese Constitution).

As a result of the First Congo War, First and

www.dol.gov

2005 Findings on the Worst Forms of Child Labor, Bureau of International Labor Affairs, U.S. Department of Labor (2006). ''This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.'' Since the end of the civil war, the situation has improved tremendously, with the number of children enrolled in primary schools rising from 5.5 million in 2002 to 16.8 million in 2018, and the number of children enrolled in secondary schools rising from 2.8 million in 2007 to 4.6 million in 2015 according to UNESCO. Actual school attendance has also improved greatly in recent years, with primary school net attendance estimated to be 82.4% in 2014 (82.4% of children ages 6–11 attended school; 83.4% for boys, 80.6% for girls).

The List of hospitals in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, hospitals in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) include the Kinshasa General Hospital, General Hospital of Kinshasa. The DRC has the world's second-highest rate of infant mortality (after Chad). In April 2011, through aid from GAVI, Global Alliance for Vaccines, a new vaccine to prevent Streptococcus pneumoniae, pneumococcal disease was introduced around Kinshasa. In 2012, it was estimated that about 1.1% of adults aged 15–49 were living with HIV/AIDS. Malaria and yellow fever are problems. In May 2019, the death toll from the 2018–19 Kivu Ebola epidemic, Ebola outbreak in DRC surpassed 1,000.

The incidence of yellow fever-related fatalities in DRC is relatively low. According to the World Health Organization's (WHO) report in 2021, only two individuals died due to yellow fever in DRC.

According to the World Bank Group, in 2016, 26,529 people died on the roads in DRC due to traffic accidents.

Maternal health is poor in DRC. According to 2010 estimates, DRC has the 17th highest Maternal death, maternal mortality rate in the world. According to UNICEF, 43.5% of children under five are Stunted growth, stunted.

United Nations emergency food relief agency warned that amid the escalating conflict and worsening situation following Coronavirus disease 2019, COVID-19 in the DRC, millions of lives were at risk as they could die of hunger. According to the data of the World Food Programme, in 2020, four in ten people in Congo lacked food security and about 15.6 million were facing a potential hunger crisis.

Air pollution levels in the Democratic Republic of the Congo are very unhealthy. In 2020, annual average air pollution in the DRC stood at 34.2 μg/m3, which is almost 6.8 times the World Health Organization PM2.5 guideline (5 μg/m3: set in September 2021). These pollution levels are estimated to reduce the life expectancy of an average citizen of the DRC by almost 2.9 years. Currently, the DRC does not have a national ambient air quality standard.

The List of hospitals in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, hospitals in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) include the Kinshasa General Hospital, General Hospital of Kinshasa. The DRC has the world's second-highest rate of infant mortality (after Chad). In April 2011, through aid from GAVI, Global Alliance for Vaccines, a new vaccine to prevent Streptococcus pneumoniae, pneumococcal disease was introduced around Kinshasa. In 2012, it was estimated that about 1.1% of adults aged 15–49 were living with HIV/AIDS. Malaria and yellow fever are problems. In May 2019, the death toll from the 2018–19 Kivu Ebola epidemic, Ebola outbreak in DRC surpassed 1,000.

The incidence of yellow fever-related fatalities in DRC is relatively low. According to the World Health Organization's (WHO) report in 2021, only two individuals died due to yellow fever in DRC.

According to the World Bank Group, in 2016, 26,529 people died on the roads in DRC due to traffic accidents.

Maternal health is poor in DRC. According to 2010 estimates, DRC has the 17th highest Maternal death, maternal mortality rate in the world. According to UNICEF, 43.5% of children under five are Stunted growth, stunted.

United Nations emergency food relief agency warned that amid the escalating conflict and worsening situation following Coronavirus disease 2019, COVID-19 in the DRC, millions of lives were at risk as they could die of hunger. According to the data of the World Food Programme, in 2020, four in ten people in Congo lacked food security and about 15.6 million were facing a potential hunger crisis.

Air pollution levels in the Democratic Republic of the Congo are very unhealthy. In 2020, annual average air pollution in the DRC stood at 34.2 μg/m3, which is almost 6.8 times the World Health Organization PM2.5 guideline (5 μg/m3: set in September 2021). These pollution levels are estimated to reduce the life expectancy of an average citizen of the DRC by almost 2.9 years. Currently, the DRC does not have a national ambient air quality standard.

The culture of the Democratic Republic of the Congo reflects the diversity of its numerous ethnic groups and their differing ways of life throughout the country—from the mouth of the River Congo on the coast, upriver through the rainforest and savanna in its centre, to the more densely populated mountains in the far east. Since the late 19th century, traditional ways of life have undergone changes brought about by colonialism, the struggle for independence, the stagnation of the Mobutu era, and most recently, the First and Second Congo Wars. Despite these pressures, the customs and cultures of the Congo have retained much of their individuality. The country's 81 million inhabitants (2016) are mainly rural. The 30% who live in urban areas have been the most open to Western culture, Western influences.

The culture of the Democratic Republic of the Congo reflects the diversity of its numerous ethnic groups and their differing ways of life throughout the country—from the mouth of the River Congo on the coast, upriver through the rainforest and savanna in its centre, to the more densely populated mountains in the far east. Since the late 19th century, traditional ways of life have undergone changes brought about by colonialism, the struggle for independence, the stagnation of the Mobutu era, and most recently, the First and Second Congo Wars. Despite these pressures, the customs and cultures of the Congo have retained much of their individuality. The country's 81 million inhabitants (2016) are mainly rural. The 30% who live in urban areas have been the most open to Western culture, Western influences.

''The Dark Side of Globalization. The Vicious Cycle of Exploitation from World Market Integration: Lesson from the Congo''

, Working Papers in Economics and Statistics 31, University Innsbruck 2007. * Exenberger, Andreas/Hartmann, Simon

''Doomed to Disaster? Long-term Trajectories of Exploitation in the Congo''

Paper to be presented at the Workshop "Colonial Extraction in the Netherlands Indies and Belgian Congo: Institutions, Institutional Change and Long Term Consequences", Utrecht 3–4 December 2010. * Gondola, Ch. Didier, "The History of Congo", Westport: Greenwood Press, 2002. * Joris, Lieve, translated by Waters, Liz, ''The Rebels' Hour'', Atlantic, 2008. * Justenhoven, Heinz-Gerhard; Ehrhart, Hans Georg. Intervention im Kongo: eine kritische Analyse der Befriedungspolitik von UN und EU. Stuttgart: Kohlhammer Verlag, 2008. (In German) . * Barbara Kingsolver, Kingsolver, Barbara. ''The Poisonwood Bible'' HarperCollins, 1998. * Larémont, Ricardo René, ed. 2005. ''Borders, nationalism and the African state''. Boulder, Colorado and London: Lynne Rienner Publishers. * Lemarchand, Reni and Hamilton, Lee; ''Burundi: Ethnic Conflict and Genocide.'' Woodrow Wilson Center Press, 1994. * Mealer, Bryan: "All Things Must Fight To Live", 2008. . * Linda Melvern, Melvern, Linda, ''Conspiracy to Murder: The Rwandan Genocide and the International Community''. Verso, 2004. * Miller, Eric: "The Inability of Peacekeeping to Address the Security Dilemma", 2010. . * Mwakikagile, Godfrey, ''Nyerere and Africa: End of an Era'', Third Edition, New Africa Press, 2006, "Chapter Six: Congo in The Sixties: The Bleeding Heart of Africa", pp. 147–205, ; Mwakikagile, Godfrey, ''Africa and America in The Sixties: A Decade That Changed The Nation and The Destiny of A Continent'', First Edition, New Africa Press, 2006, ; ''Congo in The Sixties,'' , 2009; ''Africa: Dawn of a New Era,'' , 2015. * Nzongola-Ntalaja, Georges, ''The Congo from Leopold to Kabila: A People's History'', 2002. * O'Hanlon, Redmond, ''Congo Journey'', 1996. * O'Hanlon, Redmond, ''No Mercy: A Journey into the Heart of the Congo'', 1998. * Prunier, Gérard, ''Africa's World War: Congo, the Rwandan Genocide, and the Making of a Continental Catastrophe'', 2011 (also published as ''From Genocide to Continental War: The Congolese Conflict and the Crisis of Contemporary Africa: The Congo Conflict and the Crisis of Contemporary Africa''). * Renton, David; Seddon, David; Zeilig, Leo. ''The Congo: Plunder and Resistance'', 2007. . * Reyntjens, Filip, ''The Great African War: Congo and Regional Geopolitics, 1996–2006 '', 2009. * Rorison, Sean, ''Bradt Travel Guide: Congo — Democratic Republic/Republic'', 2008. * Schulz, Manfred. ''Entwicklungsträger in der DR Kongo: Entwicklungen in Politik, Wirtschaft, Religion, Zivilgesellschaft und Kultur'', Berlin: Lit, 2008, (in German) . * Stearns, Jason: ''Dancing in the Glory of Monsters: The Collapse of the Congo and the Great War of Africa'', Public Affairs, 2011. * Tayler, Jeffrey, ''Facing the Congo'', 2001. * Turner, Thomas, ''The Congo Wars: Conflict, Myth and Reality'', 2007. * David Van Reybrouck, Van Reybrouck, David, ''Congo: The Epic History of a People'', 2014 * Wrong, Michela, ''In the Footsteps of Mr. Kurtz: Living on the Brink of Disaster in Mobutu's Congo''.

Official website.

Country Profile

from the BBC News

Democratic Republic of the Congo

''The World Factbook''. Central Intelligence Agency.

Democratic Republic of the Congo

from ''UCB Libraries GovPubs'' * *

The Democratic Republic of Congo from Global Issues

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Congo, Democratic Republic Of The Democratic Republic of the Congo, French-speaking countries and territories Member states of the Organisation internationale de la Francophonie Member states of the African Union Least developed countries Republics Member states of the United Nations Central African countries States and territories established in 1960 1960 establishments in the Republic of the Congo (Léopoldville) Countries in Africa

Republic of the Congo

The Republic of the Congo, also known as Congo-Brazzaville, the Congo Republic or simply the Congo (the last ambiguously also referring to the neighbouring Democratic Republic of the Congo), is a country located on the western coast of Central ...

), is a country in Central Africa

Central Africa (French language, French: ''Afrique centrale''; Spanish language, Spanish: ''África central''; Portuguese language, Portuguese: ''África Central'') is a subregion of the African continent comprising various countries accordin ...

. By land area, it is the second-largest country in Africa and the 11th-largest in the world. With a population of around 112 million, the DR Congo is the most populous nominally Francophone country in the world. French is the official and most widely spoken language, though there are over 200 indigenous languages. The national capital and largest city is Kinshasa

Kinshasa (; ; ), formerly named Léopoldville from 1881–1966 (), is the Capital city, capital and Cities of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, largest city of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Kinshasa is one of the world's fastest-grow ...

, which is also the economic center. The country is bordered by the Republic of the Congo

The Republic of the Congo, also known as Congo-Brazzaville, the Congo Republic or simply the Congo (the last ambiguously also referring to the neighbouring Democratic Republic of the Congo), is a country located on the western coast of Central ...

, the Cabinda exclave of Angola, and the South Atlantic Ocean

The Atlantic Ocean is the second largest of the world's five borders of the oceans, oceanic divisions, with an area of about . It covers approximately 17% of Earth#Surface, Earth's surface and about 24% of its water surface area. During the ...

to the west; the Central African Republic

The Central African Republic (CAR) is a landlocked country in Central Africa. It is bordered by Chad to Central African Republic–Chad border, the north, Sudan to Central African Republic–Sudan border, the northeast, South Sudan to Central ...

and South Sudan

South Sudan (), officially the Republic of South Sudan, is a landlocked country in East Africa. It is bordered on the north by Sudan; on the east by Ethiopia; on the south by the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Uganda and Kenya; and on the ...

to the north; Uganda

Uganda, officially the Republic of Uganda, is a landlocked country in East Africa. It is bordered to the east by Kenya, to the north by South Sudan, to the west by the Democratic Republic of the Congo, to the south-west by Rwanda, and to the ...

, Rwanda

Rwanda, officially the Republic of Rwanda, is a landlocked country in the Great Rift Valley of East Africa, where the African Great Lakes region and Southeast Africa converge. Located a few degrees south of the Equator, Rwanda is bordered by ...

, Burundi

Burundi, officially the Republic of Burundi, is a landlocked country in East Africa. It is located in the Great Rift Valley at the junction between the African Great Lakes region and Southeast Africa, with a population of over 14 million peop ...

, and Tanzania

Tanzania, officially the United Republic of Tanzania, is a country in East Africa within the African Great Lakes region. It is bordered by Uganda to the northwest; Kenya to the northeast; the Indian Ocean to the east; Mozambique and Malawi to t ...

(across Lake Tanganyika

Lake Tanganyika ( ; ) is an African Great Lakes, African Great Lake. It is the world's List of lakes by volume, second-largest freshwater lake by volume and the List of lakes by depth, second deepest, in both cases after Lake Baikal in Siberia. ...

) to the east; and Zambia

Zambia, officially the Republic of Zambia, is a landlocked country at the crossroads of Central Africa, Central, Southern Africa, Southern and East Africa. It is typically referred to being in South-Central Africa or Southern Africa. It is bor ...

and Angola

Angola, officially the Republic of Angola, is a country on the west-Central Africa, central coast of Southern Africa. It is the second-largest Portuguese-speaking world, Portuguese-speaking (Lusophone) country in both total area and List of c ...

to the south

South is one of the cardinal directions or compass points. The direction is the opposite of north and is perpendicular to both west and east.

Etymology

The word ''south'' comes from Old English ''sūþ'', from earlier Proto-Germanic ''*sunþa ...

. Centered on the Congo Basin

The Congo Basin () is the sedimentary basin of the Congo River. The Congo Basin is located in Central Africa, in a region known as west equatorial Africa. The Congo Basin region is sometimes known simply as the Congo. It contains some of the larg ...

, most of the country's terrain

Terrain (), alternatively relief or topographical relief, is the dimension and shape of a given surface of land. In physical geography, terrain is the lay of the land. This is usually expressed in terms of the elevation, slope, and orientati ...

is covered by dense rainforests and crossed by many rivers, while the east and southeast are mountainous.

The territory of the Congo was first inhabited by Central African foragers around 90,000 years ago and was settled in the Bantu expansion

Bantu may refer to:

* Bantu languages, constitute the largest sub-branch of the Niger–Congo languages

* Bantu peoples, over 400 peoples of Africa speaking a Bantu language

* Bantu knots, a type of African hairstyle

* Black Association for Natio ...

about 2,000 to 3,000 years ago. In the west, the Kingdom of Kongo

The Kingdom of Kongo ( or ''Wene wa Kongo;'' ) was a kingdom in Central Africa. It was located in present-day northern Angola, the western portion of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, southern Gabon and the Republic of the Congo. At its gre ...

ruled around the mouth of the Congo River

The Congo River, formerly also known as the Zaire River, is the second-longest river in Africa, shorter only than the Nile, as well as the third-largest river in the world list of rivers by discharge, by discharge volume, following the Amazon Ri ...

from the 14th to the 19th century. In the center and east, the empires of Mwene Muji

Mwene Muji was a polity around Lake Mai-Ndombe in the Congo Basin, likely stretching south to Idiofa. It bordered the Tio Kingdom among others to its southwest. Mwene Muji dominated the region of the Lower Kasai. It was ruled by the BaNunu, ho ...

, Luba, and Lunda ruled between the 15th and 19th centuries. These kingdoms were broken up by Europeans during the colonization of the Congo Basin

Colonization of the Congo Basin refers to the European colonization of the Congo Basin of tropical Africa. It was the last part of the continent to be colonized. By the end of the 19th century, the Basin had been carved up by European colonial ...

. King Leopold II of Belgium

Leopold II (9 April 1835 – 17 December 1909) was the second king of the Belgians from 1865 to 1909, and the founder and sole owner of the Congo Free State from 1885 to 1908.

Born in Brussels as the second but eldest-surviving son of King Leo ...

acquired rights to the Congo territory in 1885 and called it the Congo Free State

The Congo Free State, also known as the Independent State of the Congo (), was a large Sovereign state, state and absolute monarchy in Central Africa from 1885 to 1908. It was privately owned by Leopold II of Belgium, King Leopold II, the const ...

. In 1908, Leopold ceded

The act of cession is the assignment of property to another entity. In international law it commonly refers to land transferred by treaty. Ballentine's Law Dictionary defines cession as "a surrender; a giving up; a relinquishment of jurisdicti ...

the territory after international pressure in response to widespread atrocities, and it became a Belgian colony. Congo achieved independence

Independence is a condition of a nation, country, or state, in which residents and population, or some portion thereof, exercise self-government, and usually sovereignty, over its territory. The opposite of independence is the status of ...

from Belgium

Belgium, officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. Situated in a coastal lowland region known as the Low Countries, it is bordered by the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Luxembourg to the southeas ...

in 1960 and was immediately confronted by a series of secessionist movements, the assassination of Prime Minister Patrice Lumumba

Patrice Émery Lumumba ( ; born Isaïe Tasumbu Tawosa; 2 July 192517 January 1961) was a Congolese politician and independence leader who served as the first prime minister of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (then known as the Republic o ...

, and the seizure of power by Mobutu Sese Seko

Mobutu Sese Seko Kuku Ngbendu wa za Banga ( ; born Joseph-Désiré Mobutu; 14 October 1930 – 7 September 1997), often shortened to Mobutu Sese Seko or Mobutu and also known by his initials MSS, was a Congolese politician and military officer ...

in 1965. Mobutu renamed the country Zaire

Zaire, officially the Republic of Zaire, was the name of the Democratic Republic of the Congo from 1971 to 18 May 1997. Located in Central Africa, it was, by area, the third-largest country in Africa after Sudan and Algeria, and the 11th-la ...

in 1971 and imposed a personalist dictatorship

A dictatorship is an autocratic form of government which is characterized by a leader, or a group of leaders, who hold governmental powers with few to no limitations. Politics in a dictatorship are controlled by a dictator, and they are faci ...

.

Instability caused by the influx of refugees from the Rwandan Civil War

The Rwandan Civil War was a large-scale civil war in Rwanda which was fought between the Rwandan Armed Forces, representing the country's government, and the rebel Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) from 1October 1990 to 18 July 1994. The war arose ...

into the eastern part of the country led to the First Congo War

The First Congo War, also known as Africa's First World War, was a Civil war, civil and international military conflict that lasted from 24 October 1996 to 16 May 1997, primarily taking place in Zaire (which was renamed the Democratic Republi ...

from 1996 to 1997, ending in the overthrow of Mobutu. Its name was changed back to the DRC and it was confronted by the Second Congo War

The Second Congo War, also known as Africa's World War or the Great War of Africa, was a major conflict that began on 2 August 1998, in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, just over a year after the First Congo War. The war initially erupted ...

from 1998 to 2003, which resulted in the deaths of 5.4 million people and the assassination of President Laurent-Désiré Kabila

Laurent-Désiré Kabila (; 27 November 1939 – 16 January 2001) usually known as Laurent Kabila or Kabila the Father (American English, US: ), was a Congolese rebel and politician who served as the third president of the Democratic Republic of t ...

. The war, widely described as the deadliest conflict since World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, ended under President Joseph Kabila

Joseph Kabila Kabange ( , ; born 4 June 1971) is a Congolese politician and former military officer who served as the fourth President of the Democratic Republic of the Congo from 2001 to 2019. He took office ten days after the assassination o ...

, who restored relative stability to much of the country, although fighting continued at a lower level mainly in the east. Human rights

Human rights are universally recognized Morality, moral principles or Social norm, norms that establish standards of human behavior and are often protected by both Municipal law, national and international laws. These rights are considered ...

remained poor, and there were frequent abuses, such as forced disappearances

An enforced disappearance (or forced disappearance) is the secret abduction or imprisonment of a person with the support or acquiescence of a State (polity), state followed by a refusal to acknowledge the person's fate or whereabouts with the i ...

, torture, arbitrary imprisonment and restrictions on civil liberties. Kabila stepped down in 2019, the country's first peaceful transition of power

A peaceful transition or transfer of power is a concept important to democracy, democratic governments in which the leadership of a government peacefully hands over control of government to a newly elected leadership. This may be after elections o ...

since independence, after Félix Tshisekedi

Félix Antoine Tshisekedi Tshilombo (; born 13 June 1963) is a Congolese politician who has served as the fifth president of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, since 2019.

He was the leader of the Union for Democracy and Social Progress (Demo ...

won the highly contentious 2018 general election. Since the early 2000s, there have been over 100 armed groups active in the DRC, mainly concentrated in the Kivu region. One of its largest cities, Goma

Goma is a city in the eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo. It is the Capital city, capital and largest city of the North Kivu, North Kivu Province; it is located on the northern shore of Lake Kivu and shares borders with the Bukumu Chiefdo ...

, was occupied by the March 23 Movement

The March 23 Movement (), often abbreviated as M23 and also known as the Congolese Revolutionary Army (), is a Congolese Rwandan-backed rebel paramilitary group. Based in the eastern regions of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, it operates ...

(M23) rebels briefly in 2012 and again in 2025. The M23 uprising escalated in early 2025 after the capture of multiple cities in the east, including with military support from Rwanda

Rwanda, officially the Republic of Rwanda, is a landlocked country in the Great Rift Valley of East Africa, where the African Great Lakes region and Southeast Africa converge. Located a few degrees south of the Equator, Rwanda is bordered by ...

, which has caused a conflict between the two countries.

Despite being incredibly rich in natural resource

Natural resources are resources that are drawn from nature and used with few modifications. This includes the sources of valued characteristics such as commercial and industrial use, aesthetic value, scientific interest, and cultural value. ...

s, the DRC is one of the poorest countries in the world, having suffered from political instability, a lack of infrastructure, rampant corruption, and centuries of both commercial and colonial extraction and exploitation, followed by more than 60 years of independence, with little widespread development;

BBC. (9 October 2013). "DR Congo: Cursed by its natural wealth"BBC News website

Retrieved 9 December 2017. the nation is a prominent example of the " resource curse". Besides the capital Kinshasa, the two next largest cities,

Lubumbashi

Lubumbashi ( , ; former ; former ) is the second-largest Cities of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, city in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, located in the country's southeasternmost part, along the border with Zambia. The capital ...

and Mbuji-Mayi

Mbuji-Mayi (formerly Bakwanga) is a city and the capital of Kasai-Oriental Province in the south-central Democratic Republic of Congo. It is thought to be the second largest city in the country, after the capital Kinshasa and ahead of Lubumbashi ...

, are both mining communities

A mining community, also known as a mining town or a mining camp, is a community that houses miners. Mining communities are usually created around a mine or a quarry.

Historical mining communities Australia

* Ballarat, Victoria

* Bendig ...

. The DRC's largest exports are raw mineral

In geology and mineralogy, a mineral or mineral species is, broadly speaking, a solid substance with a fairly well-defined chemical composition and a specific crystal structure that occurs naturally in pure form.John P. Rafferty, ed. (2011): Mi ...

s and metal

A metal () is a material that, when polished or fractured, shows a lustrous appearance, and conducts electrical resistivity and conductivity, electricity and thermal conductivity, heat relatively well. These properties are all associated wit ...

, which accounted for 80% of exports in 2023, with China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. With population of China, a population exceeding 1.4 billion, it is the list of countries by population (United Nations), second-most populous country after ...

being its largest trade partner. In 2024, DR Congo's level of human development was ranked 180th out of 193 countries by the Human Development Index

The Human Development Index (HDI) is a statistical composite index of life expectancy, Education Index, education (mean years of schooling completed and expected years of schooling upon entering the education system), and per capita income i ...

and it is classified as being one of the least developed countries

The least developed countries (LDCs) are developing countries listed by the United Nations that exhibit the lowest indicators of socioeconomic development. The concept of LDCs originated in the late 1960s and the first group of LDCs was listed b ...

by the United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is the Earth, global intergovernmental organization established by the signing of the Charter of the United Nations, UN Charter on 26 June 1945 with the stated purpose of maintaining international peace and internationa ...

(UN). , following two decades of various civil wars and continued internal conflicts, around one million Congolese refugees were still living in neighbouring countries. Two million children are at risk of starvation, and the fighting has displaced 7.3 million people. The country is a member of the United Nations, Non-Aligned Movement

The Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) is a forum of 121 countries that Non-belligerent, are not formally aligned with or against any major power bloc. It was founded with the view to advancing interests of developing countries in the context of Cold W ...

, African Union

The African Union (AU) is a continental union of 55 member states located on the continent of Africa. The AU was announced in the Sirte Declaration in Sirte, Libya, on 9 September 1999, calling for the establishment of the African Union. The b ...

, COMESA

The Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA) is a regional economic community in Africa with twenty-one member states stretching from Tunisia to Eswatini. COMESA was formed in December 1994, replacing a Preferential Trade Area whi ...

, Southern African Development Community

The Southern African Development Community (SADC) is an inter-governmental organization headquartered in Gaborone, Botswana.

Goals

The SADC's goal is to further regional socio-economic cooperation and integration as well as political and se ...

, , and Economic Community of Central African States

The Economic Community of Central African States (ECCAS; , CEEAC; , CEEAC; , CEEAC) is an Economic Community of the African Union for promotion of regional economic co-operation in Central Africa. It "aims to achieve collective autonomy, raise ...

.

Etymology

The Democratic Republic of the Congo is named after theCongo River

The Congo River, formerly also known as the Zaire River, is the second-longest river in Africa, shorter only than the Nile, as well as the third-largest river in the world list of rivers by discharge, by discharge volume, following the Amazon Ri ...

, which flows through the country. The Congo River is the world's deepest river and the world's third-largest river by discharge. The ''Comité d'études du haut Congo'' ("Committee for the Study of the Upper Congo"), established by King Leopold II of Belgium

Leopold II (9 April 1835 – 17 December 1909) was the second king of the Belgians from 1865 to 1909, and the founder and sole owner of the Congo Free State from 1885 to 1908.

Born in Brussels as the second but eldest-surviving son of King Leo ...

in 1876, and the International Association of the Congo

The International Association of the Congo (), also known as the International Congo Society, was an association founded on 17 November 1879 by Leopold II of Belgium to further his interests in the Congo. It replaced the Belgian Committee for S ...

, established by him in 1879, were also named after the river.

The Congo River was named by early European sailors after the Kingdom of Kongo

The Kingdom of Kongo ( or ''Wene wa Kongo;'' ) was a kingdom in Central Africa. It was located in present-day northern Angola, the western portion of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, southern Gabon and the Republic of the Congo. At its gre ...

and its Bantu inhabitants, the Kongo people

The Kongo people (also , singular: or ''M'kongo; , , singular: '') are a Bantu ethnic group primarily defined as the speakers of Kikongo. Subgroups include the Beembe, Bwende, Vili, Sundi, Yombe, Dondo, Lari, and others.

They have li ...

, when they encountered them in the 16th century. The word ''Kongo'' comes from the Kongo language

Kongo or Kikongo is one of the Bantu languages spoken by the Kongo people living in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), the Republic of the Congo, Gabon, and Angola. It is a tonal language. The vast majority of present-day speakers live ...

(also called ''Kikongo''). According to American writer Samuel Henry Nelson: "It is probable that the word 'Kongo' itself implies a public gathering and that it is based on the root ''konga'', 'to gather' (trans tive." The modern name of the Kongo people, ''Bakongo'', was introduced in the early 20th century.

The Democratic Republic of the Congo has been known in the past as, in chronological order, the Congo Free State

The Congo Free State, also known as the Independent State of the Congo (), was a large Sovereign state, state and absolute monarchy in Central Africa from 1885 to 1908. It was privately owned by Leopold II of Belgium, King Leopold II, the const ...

, Belgian Congo

The Belgian Congo (, ; ) was a Belgian colonial empire, Belgian colony in Central Africa from 1908 until independence in 1960 and became the Republic of the Congo (Léopoldville). The former colony adopted its present name, the Democratic Repu ...

, the Republic of the Congo-Léopoldville, the Democratic Republic of the Congo and the Republic of Zaire

Zaire, officially the Republic of Zaire, was the name of the Democratic Republic of the Congo from 1971 to 18 May 1997. Located in Central Africa, it was, by area, the third-largest country in Africa after Sudan and Algeria, and the 11th-la ...

, before returning to its current name the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

At the time of independence, the country was named the Republic of the Congo-Léopoldville to distinguish it from its neighbour Congo, officially the Republic of the Congo

The Republic of the Congo, also known as Congo-Brazzaville, the Congo Republic or simply the Congo (the last ambiguously also referring to the neighbouring Democratic Republic of the Congo), is a country located on the western coast of Central ...

. With the promulgation of the Luluabourg Constitution on 1 August 1964, the country became the DRC but was renamed Zaire

Zaire, officially the Republic of Zaire, was the name of the Democratic Republic of the Congo from 1971 to 18 May 1997. Located in Central Africa, it was, by area, the third-largest country in Africa after Sudan and Algeria, and the 11th-la ...

(a past name for the Congo River) on 27 October 1971 by President Mobutu Sese Seko

Mobutu Sese Seko Kuku Ngbendu wa za Banga ( ; born Joseph-Désiré Mobutu; 14 October 1930 – 7 September 1997), often shortened to Mobutu Sese Seko or Mobutu and also known by his initials MSS, was a Congolese politician and military officer ...

as part of his '' Authenticité'' initiative.

The word ''Zaire'' is from a Portuguese adaptation of a Kikongo word ''nzadi'' ("river"), a truncation of ''nzadi o nzere'' ("river swallowing rivers"). The river was known as ''Zaire'' during the 16th and 17th centuries; ''Congo'' seems to have replaced ''Zaire'' gradually in English usage during the 18th century, and ''Congo'' is the preferred English name in 19th-century literature, although references to ''Zaire'' as the name used by the natives (i.e., derived from Portuguese usage) remained common.

In 1992, the Sovereign National Conference voted to change the name of the country to the "Democratic Republic of the Congo", but the change was not made. The country's name was later restored by President Laurent-Désiré Kabila

Laurent-Désiré Kabila (; 27 November 1939 – 16 January 2001) usually known as Laurent Kabila or Kabila the Father (American English, US: ), was a Congolese rebel and politician who served as the third president of the Democratic Republic of t ...

when he overthrew Mobutu in 1997. To distinguish it from the neighboring Republic of the Congo, it is sometimes referred to as ''Congo (Kinshasa)'', ''Congo-Kinshasa'', or ''Big Congo''. Its name is sometimes also abbreviated as ''Congo DR'', ''DR Congo'', ''DRC'', ''the DROC'', and ''RDC'' (in French).

History

Early history

The geographical area now known as the Democratic Republic of the Congo was populated as early as 90,000 years ago, as shown by the 1988 discovery of theSemliki harpoon The Semliki harpoon, also known as the Katanda harpoon, refers to a group of complex barbed harpoon heads carved from bone, which were found at an archaeologic site on the Semliki River in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (formerly Zaire); the ...

at Katanda, one of the oldest barbed harpoons ever found, believed to have been used to catch giant river catfish.

Bantu peoples

The Bantu peoples are an Indigenous peoples of Africa, indigenous ethnolinguistic grouping of approximately 400 distinct native Demographics of Africa, African List of ethnic groups of Africa, ethnic groups who speak Bantu languages. The language ...

reached Central Africa

Central Africa (French language, French: ''Afrique centrale''; Spanish language, Spanish: ''África central''; Portuguese language, Portuguese: ''África Central'') is a subregion of the African continent comprising various countries accordin ...

at some point during the first millennium BC, then gradually started to expand southward. Their propagation was accelerated by the adoption of pastoralism

Pastoralism is a form of animal husbandry where domesticated animals (known as "livestock") are released onto large vegetated outdoor lands (pastures) for grazing, historically by nomadic people who moved around with their herds. The anim ...

and of Iron Age

The Iron Age () is the final epoch of the three historical Metal Ages, after the Chalcolithic and Bronze Age. It has also been considered as the final age of the three-age division starting with prehistory (before recorded history) and progre ...

techniques. The people living in the south and southwest were foraging groups, whose technology involved only minimal use of metal technologies. The development of metal tools during this time period revolutionized agriculture. This led to the displacement of the African pygmies

The African Pygmies (or Congo Pygmies, variously also Central African foragers, African rainforest hunter-gatherers (RHG) or Forest People of Central Africa) are a group of ethnicities Indigenous peoples of Africa, native to Central Africa, ...

. Following the Bantu migrations, a period of state and class formation began circa 700 with three centres in the modern-day territory; one to the west around Pool Malebo

The Pool Malebo, formerly Stanley Pool, also known as Mpumbu, Lake Nkunda or Lake Nkuna by local indigenous people in pre-colonial times, is a lake-like widening in the lower reaches of the Congo River.

, one east around Lake Mai-Ndombe

Lake Mai-Ndombe (, ) is a large freshwater lake in Mai-Ndombe province in western Democratic Republic of the Congo.

The lake is within the Tumba-Ngiri-Maindombe area, the largest Wetland of International Importance recognized by the Ramsar Con ...

, and a third even further east and south around the Upemba Depression

The Upemba Depression (or Kamalondo Depression) is a large marshy bowl area (Depression (geology), depression) in the Democratic Republic of the Congo comprising some fifty lakes, including 22 of relatively large size including Lake Upemba (530&nbs ...

.

By the 13th century, there were three main confederations of states in the western Congo Basin around Pool Malebo. In the east were the Seven Kingdoms of Kongo dia Nlaza

The Seven Kingdoms of Kongo dia Nlaza were a confederation of states in west Central Africa at least from the 13th century. They were absorbed into the Kingdom of Kongo in the 16th century, being mentioned in the titles of King Alvaro II in 1583. I ...

, considered to be the oldest and most powerful, which likely included Nsundi

Nsundi was a province of the old Kingdom of Kongo

The Kingdom of Kongo ( or ''Wene wa Kongo;'' ) was a kingdom in Central Africa. It was located in present-day northern Angola, the western portion of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, south ...

, Mbata

Bambata, or Bhambatha kaMancinza (c. 1865–1906?), also known as Mbata Bhambatha, was a Zulu chief of the amaZondi clan in the Colony of Natal and son of Mancinza. He is famous for his role in an armed rebellion in 1906 when the poll ta ...

, Mpangu, and possibly Kundi and Okanga. South of these was Mpemba which stretched from modern-day Angola

Angola, officially the Republic of Angola, is a country on the west-Central Africa, central coast of Southern Africa. It is the second-largest Portuguese-speaking world, Portuguese-speaking (Lusophone) country in both total area and List of c ...

to the Congo River

The Congo River, formerly also known as the Zaire River, is the second-longest river in Africa, shorter only than the Nile, as well as the third-largest river in the world list of rivers by discharge, by discharge volume, following the Amazon Ri ...

. It included various kingdoms such as Mpemba Kasi Mpemba Kasi is the traditional name of a large Bantu kingdom which was the northernmost territory of the confederation Mpemba, and to the south of the Mbata Kingdom. It merged with that state to form the Kingdom of Kongo

The Kingdom of Kongo ...

and Vunda. To its west across the Congo River was a confederation of three small states; Vungu The kingdom of Vungu or Bungu was a historic state located in Mayombe (between the present-day Republic of Congo and the present-day Democratic Republic of Congo). In the 13th century it led a confederation of itself, Ngoyo, and Kakongo. It neighbo ...

(its leader), Kakongo

Kakongo was a small kingdom located on the Atlantic coast of Central Africa, in the modern-day Republic of the Congo and Cabinda Province, Angola. In the 13th century, it formed part of a confederation led by Vungu. Along with its neighboring kin ...

, and Ngoyo

Ngoyo was a kingdom of the Woyo ethnic group, located in the south of Cabinda and on the Atlantic coast of Central Africa, just north of the Congo River. In the 13th century it formed part of a confederation led by Vungu. Ngoyo tradition hel ...

.

The Kingdom of Kongo

The Kingdom of Kongo ( or ''Wene wa Kongo;'' ) was a kingdom in Central Africa. It was located in present-day northern Angola, the western portion of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, southern Gabon and the Republic of the Congo. At its gre ...

was founded in the 14th century and dominated the western region. The empire of Mwene Muji

Mwene Muji was a polity around Lake Mai-Ndombe in the Congo Basin, likely stretching south to Idiofa. It bordered the Tio Kingdom among others to its southwest. Mwene Muji dominated the region of the Lower Kasai. It was ruled by the BaNunu, ho ...

was founded around Lake Mai-Ndombe. From the Upemba Depression the Luba Empire

The Luba Empire or Kingdom of Luba was a pre-colonial Central African state that arose in the marshy grasslands of the Upemba Depression in what is now southern Democratic Republic of Congo.

Origins and foundation

Archaeological research shows t ...

and Lunda Empire

The Lunda Empire or Kingdom of Lunda was a confederation of states in what is now the Democratic Republic of Congo, north-eastern Angola, and north-western Zambia. Its central state was in Katanga Province, Katanga.

Origin

Initially, the core of ...

emerged in the 15th and 17th centuries respectfully dominated the eastern region.

Congo Free State (1877–1908)

Belgian exploration and administration took place from the 1870s until the 1920s. It was first led by

Belgian exploration and administration took place from the 1870s until the 1920s. It was first led by Henry Morton Stanley

Sir Henry Morton Stanley (born John Rowlands; 28 January 1841 – 10 May 1904) was a Welsh-American explorer, journalist, soldier, colonial administrator, author, and politician famous for his exploration of Central Africa and search for missi ...

, who undertook his explorations under the sponsorship of King Leopold II of Belgium

Leopold II (9 April 1835 – 17 December 1909) was the second king of the Belgians from 1865 to 1909, and the founder and sole owner of the Congo Free State from 1885 to 1908.

Born in Brussels as the second but eldest-surviving son of King Leo ...

. The eastern regions of the precolonial Congo were heavily disrupted by constant slave raiding

Slave raiding is a military raid for the purpose of capturing people and bringing them from the raid area to serve as slaves. Once seen as a normal part of warfare, it is nowadays widely considered a war crime. Slave raiding has occurred sinc ...

, mainly from Arab–Swahili slave traders such as the infamous Tippu Tip

Tippu Tip, or Tippu Tib (– June 14, 1905), real name Ḥamad ibn Muḥammad ibn Jumʿah ibn Rajab ibn Muḥammad ibn Saʿīd al Murjabī (), was an Afro-Omani ivory and slave owner and trader, explorer, governor and plantation owner. He ...

, who was well known to Stanley.

Leopold had designs on what was to become the Congo as a colony.Keyes, Michael''The Congo Free State – a colony of gross excess''.

September 2004. In a succession of negotiations, Leopold, professing humanitarian objectives in his capacity as chairman of the

front organization

A front organization is any entity set up by and controlled by another organization, such as intelligence agencies, organized crime groups, terrorist organizations, secret societies, banned organizations, religious or political groups, advocacy ...

'' Association Internationale Africaine'', actually played one European rival against another. King Leopold formally acquired rights to the Congo territory at the Conference of Berlin in 1885 and made the land his private property. He named it the

King Leopold formally acquired rights to the Congo territory at the Conference of Berlin in 1885 and made the land his private property. He named it the Congo Free State

The Congo Free State, also known as the Independent State of the Congo (), was a large Sovereign state, state and absolute monarchy in Central Africa from 1885 to 1908. It was privately owned by Leopold II of Belgium, King Leopold II, the const ...

. Leopold's regime began various infrastructure projects, such as the construction of the railway that ran from the coast to the capital of Leopoldville (now Kinshasa), which took eight years to complete.

In the Free State, colonists coerced the local population into producing rubber, for which the spread of automobiles and development of rubber tires created a growing international market. Rubber sales made a fortune for Leopold, who built several buildings in Brussels

Brussels, officially the Brussels-Capital Region, (All text and all but one graphic show the English name as Brussels-Capital Region.) is a Communities, regions and language areas of Belgium#Regions, region of Belgium comprising #Municipalit ...

and Ostend

Ostend ( ; ; ; ) is a coastal city and municipality in the province of West Flanders in the Flemish Region of Belgium. It comprises the boroughs of Mariakerke, Raversijde, Stene and Zandvoorde, and the city of Ostend proper – the la ...

to honor himself and his country. To enforce the rubber quotas, the ''Force Publique

The ''Force Publique'' (, "Public Force"; ) was the military of the Congo Free State and the Belgian Congo from 1885 to 1960. It was established after Belgian Army officers travelled to the Free State to found an armed force in the colony on L ...

'' was called in and made the practice of cutting off the limbs of the natives a matter of policy.Fage, John D. (1982)The Cambridge history of Africa: From the earliest times to c. 500 BC

,

Cambridge University Press

Cambridge University Press was the university press of the University of Cambridge. Granted a letters patent by King Henry VIII in 1534, it was the oldest university press in the world. Cambridge University Press merged with Cambridge Assessme ...

. p. 748; Under the Congo Free State concessions were granted to private industry, granting a monopoly over violence and resource extraction. The most violent of these concession regions, were surrounding rubber plantations. Concession regions would align with villages, employing local chiefs to aid in enforce strict quotas. Failure to comply or to meet quotas would result in kidnaping of family, held ransom until quotas could be met or physical violence. Violence was carried out by "village sentries," European militias employed to ensure collection. These sentries were granted full impunity for violence, without proper oversight were known to kill and eat underperforming workers.

During 1885–1908, at least 10 million Congolese died as a consequence of exploitation and disease. In some areas the population declined dramatically – it has been estimated that sleeping sickness

African trypanosomiasis is an insect-borne parasitic infection of humans and other animals.

Human African trypanosomiasis (HAT), also known as African sleeping sickness or simply sleeping sickness, is caused by the species '' Trypanosoma b ...

and smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by Variola virus (often called Smallpox virus), which belongs to the genus '' Orthopoxvirus''. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (W ...

killed nearly half the population in the areas surrounding the lower Congo River.

News of the abuses began to circulate. In 1904, the British consul at Boma in the Congo, Roger Casement

Roger David Casement (; 1 September 1864 – 3 August 1916), known as Sir Roger Casement, CMG, between 1911 and 1916, was a diplomat and Irish nationalist executed by the United Kingdom for treason during World War I. He worked for the Britis ...

, was instructed by the British government to investigate. His report, called the Casement Report

The Casement Report was a 1904 document written at the behest of the Government of the United Kingdom, British Government by Roger Casement (1864–1916)—a British diplomat and future Irish War of Independence, Irish independence fighter—detai ...

, confirmed the accusations of humanitarian abuses. The Belgian Parliament forced Leopold II to set up an independent commission of inquiry. Its findings confirmed Casement's report of abuses, concluding that the population of the Congo had been "reduced by half" during this period. Hochschild, Adam. ''King Leopold's Ghost

''King Leopold's Ghost: A Story of Greed, Terror and Heroism in Colonial Africa'' (1998) is a best-selling popular history book by Adam Hochschild that explores the exploitation of the Congo Free State by King Leopold II of the Belgians betw ...

'', Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 1999; Determining precisely how many people died is impossible, as no accurate records exist.

Belgian Congo (1908–1960)