The World's Columbian Exposition, also known as the Chicago World's Fair, was a

world's fair

A world's fair, also known as a universal exhibition, is a large global exhibition designed to showcase the achievements of nations. These exhibitions vary in character and are held in different parts of the world at a specific site for a perio ...

held in

Chicago

Chicago is the List of municipalities in Illinois, most populous city in the U.S. state of Illinois and in the Midwestern United States. With a population of 2,746,388, as of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, it is the List of Unite ...

from May 5 to October 31, 1893, to celebrate the 400th anniversary of

Christopher Columbus

Christopher Columbus (; between 25 August and 31 October 1451 – 20 May 1506) was an Italians, Italian explorer and navigator from the Republic of Genoa who completed Voyages of Christopher Columbus, four Spanish-based voyages across the At ...

's arrival in the

New World

The term "New World" is used to describe the majority of lands of Earth's Western Hemisphere, particularly the Americas, and sometimes Oceania."America." ''The Oxford Companion to the English Language'' (). McArthur, Tom, ed., 1992. New York: ...

in 1492.

The centerpiece of the Fair, held in

Jackson Park, was a large water pool representing the voyage that Columbus took to the New World. Chicago won the right to host the fair over several competing cities, including

New York City

New York, often called New York City (NYC), is the most populous city in the United States, located at the southern tip of New York State on one of the world's largest natural harbors. The city comprises five boroughs, each coextensive w ...

,

Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly known as Washington or D.C., is the capital city and federal district of the United States. The city is on the Potomac River, across from Virginia, and shares land borders with ...

, and

St. Louis

St. Louis ( , sometimes referred to as St. Louis City, Saint Louis or STL) is an independent city in the U.S. state of Missouri. It lies near the confluence of the Mississippi and the Missouri rivers. In 2020, the city proper had a populatio ...

. The exposition was an influential social and cultural event and had a profound effect on American

architecture

Architecture is the art and technique of designing and building, as distinguished from the skills associated with construction. It is both the process and the product of sketching, conceiving, planning, designing, and construction, constructi ...

, the arts, American industrial optimism, and Chicago's image.

The layout of the Chicago Columbian Exposition was predominantly designed by

John Wellborn Root

John Wellborn Root (January 10, 1850 – January 15, 1891) was an American architect who was based in Chicago with Daniel Burnham. He was one of the founders of the Chicago School style. Two of his buildings have been designated National Hist ...

,

Daniel Burnham

Daniel Hudson Burnham (September 4, 1846 – June 1, 1912) was an American architect and urban designer. A proponent of the ''Beaux-Arts architecture, Beaux-Arts'' movement, he may have been "the most successful power broker the American archi ...

,

Frederick Law Olmsted

Frederick Law Olmsted (April 26, 1822 – August 28, 1903) was an American landscape architect, journalist, Social criticism, social critic, and public administrator. He is considered to be the father of landscape architecture in the U ...

, and

Charles B. Atwood.

It was the prototype of what Burnham and his colleagues thought a city should be. It was designed to follow

Beaux-Arts principles of design, namely

neoclassical architecture

Neoclassical architecture, sometimes referred to as Classical Revival architecture, is an architectural style produced by the Neoclassicism, Neoclassical movement that began in the mid-18th century in Italy, France and Germany. It became one of t ...

principles based on symmetry, balance, and splendor. The color of the material generally used to cover the buildings' façades, white

staff, gave the fairgrounds its nickname, the White City. Many prominent architects designed its 14 "great buildings". Artists and musicians were featured in exhibits and many also made depictions and works of art inspired by the exposition.

The exposition covered , featuring nearly 200 new but temporary buildings of predominantly neoclassical architecture,

canal

Canals or artificial waterways are waterways or engineered channels built for drainage management (e.g. flood control and irrigation) or for conveyancing water transport vehicles (e.g. water taxi). They carry free, calm surface ...

s and

lagoon

A lagoon is a shallow body of water separated from a larger body of water by a narrow landform, such as reefs, barrier islands, barrier peninsulas, or isthmuses. Lagoons are commonly divided into ''coastal lagoons'' (or ''barrier lagoons'') an ...

s, and people and cultures from 46 countries.

More than 27 million people attended the exposition during its six-month run. Its scale and grandeur far exceeded the other

world's fairs, and it became a symbol of emerging

American exceptionalism

American exceptionalism is the belief that the United States is either distinctive, unique, or exemplary compared to other nations. Proponents argue that the Culture of the United States, values, Politics of the United States, political system ...

, much in the same way that the

Great Exhibition

The Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations, also known as the Great Exhibition or the Crystal Palace Exhibition (in reference to the temporary structure in which it was held), was an international exhibition that took ...

became a symbol of the

Victorian era

In the history of the United Kingdom and the British Empire, the Victorian era was the reign of Queen Victoria, from 20 June 1837 until her death on 22 January 1901. Slightly different definitions are sometimes used. The era followed the ...

United Kingdom.

Dedication ceremonies for the fair were held on October 21, 1892, but the fairgrounds were not opened to the public until May 1, 1893. The fair continued until October 30, 1893. In addition to recognizing the 400th anniversary of the discovery of the New World, the fair served to show the world that Chicago had risen from the ashes of the

Great Chicago Fire

The Great Chicago Fire was a conflagration that burned in the American city of Chicago, Illinois during October 8–10, 1871. The fire killed approximately 300 people, destroyed roughly of the city including over 17,000 structures, and left mor ...

, which had destroyed much of the city in 1871.

On October 9, 1893, the day designated as Chicago Day, the fair set a world record for outdoor event attendance, drawing 751,026 people. The debt for the fair was soon paid off with a check for $1.5 million (equivalent to $ in ). Chicago has commemorated the fair with one of the stars on its

municipal flag.

History

Planning and organization

Many prominent civic, professional, and commercial leaders from around the United States helped finance, coordinate, and manage the Fair, including Chicago shoe company owner Charles H. Schwab, Chicago railroad and manufacturing magnate

John Whitfield Bunn

:''This article concerns John Whitfield Bunn, Jacob Bunn, and the entrepreneurs who were interconnected with the Bunn brothers through association or familial and genealogical connection.''

John Whitfield Bunn (June 21, 1831 – June 7, 1920)Ill ...

, and Connecticut banking, insurance, and iron products magnate

Milo Barnum Richardson, among many others.

The fair was planned in the early 1890s during the

Gilded Age

In History of the United States, United States history, the Gilded Age is the period from about the late 1870s to the late 1890s, which occurred between the Reconstruction era and the Progressive Era. It was named by 1920s historians after Mar ...

of rapid industrial growth, immigration, and class tension. World's fairs, such as London's 1851

Crystal Palace Exhibition, had been successful in Europe as a way to bring together societies fragmented along class lines.

The first American attempt at a

world's fair in Philadelphia in 1876 drew crowds, but was a financial failure. Nonetheless, ideas about distinguishing the 400th anniversary of Columbus' landing started in the late 1880s. Civic leaders in St. Louis, New York City, Washington DC, and Chicago expressed interest in hosting a fair to generate profits, boost real estate values, and promote their cities. Congress was called on to decide the location. New York financiers

J. P. Morgan

John Pierpont Morgan Sr. (April 17, 1837 – March 31, 1913) was an American financier and investment banker who dominated corporate finance on Wall Street throughout the Gilded Age and Progressive Era. As the head of the banking firm that ...

,

Cornelius Vanderbilt

Cornelius Vanderbilt (May 27, 1794 – January 4, 1877), nicknamed "the Commodore", was an American business magnate who built his wealth in railroads and shipping. After working with his father's business, Vanderbilt worked his way into lead ...

, and

William Waldorf Astor

William Waldorf Astor, 1st Viscount Astor (31 March 1848 – 18 October 1919) was an American-English attorney, politician, hotelier, publisher and philanthropist. Astor was a scion of the very wealthy Astor family of New York City. He moved t ...

, among others, pledged $15 million to finance the fair if Congress awarded it to New York, while Chicagoans

Charles T. Yerkes,

Marshall Field

Marshall Field (August 18, 1834January 16, 1906) was an American entrepreneur and the founder of Marshall Field's, Marshall Field and Company, the Chicago-based department stores. His business was renowned for its then-exceptional level of qua ...

,

Philip Armour

Philip Danforth Armour Sr. (16 May 1832 – 6 January 1901) was an American meat packing industry, meatpacking industrialist who founded the Chicago-based firm of Armour & Company. Born on a farm in upstate New York, he initially gained financi ...

,

Gustavus Swift

Gustavus Franklin Swift, Sr. (June 24, 1839 – March 29, 1903) was an American business executive. He founded a meat-packing empire in the Midwest during the late 19th century, over which he presided until his death. He is credited with t ...

, and

Cyrus McCormick, Jr., offered to finance a Chicago fair. What finally persuaded Congress was Chicago banker

Lyman Gage, who raised several million additional dollars in a 24-hour period, over and above New York's final offer.

Chicago representatives not only fought for the world's fair for monetary reasons, but also for reasons of practicality. In a Senate hearing held in January 1890, representative

Thomas Barbour Bryan

Thomas Barbour Bryan (December 22, 1828 – January 26, 1906) was an American businessman, lawyer, and politician.

Born in Virginia, a member of the prestigious Barbour family on his mother's side, Bryan largely made a name for himself in Chic ...

argued that the most important qualities for a world's fair were "abundant supplies of good air and pure water", "ample space, accommodations and transportation for all exhibits and visitors". He argued that New York had too many obstructions, and Chicago would be able to use large amounts of land around the city where there was "not a house to buy and not a rock to blast" and that it would be located so that "the artisan and the farmer and the shopkeeper and the man of humble means" would be able to easily access the fair. Bryan continued to say that the fair was of "vital interest" to the West, and that the West wanted the location to be Chicago. The city spokesmen would continue to stress the essentials of a successful exposition and that only Chicago was fit to fill these exposition requirements.

The location of the fair was decided through several rounds of voting by the United States House of Representatives. The first ballot showed Chicago with a large lead over New York, St. Louis and Washington, D.C., but short of a majority. Chicago broke the 154-vote majority threshold on the eighth ballot, receiving 157 votes to New York's 107.

The exposition corporation and national exposition commission settled on

Jackson Park and an area around it as the fair site.

Daniel H. Burnham was selected as director of works, and

George R. Davis George Davis may refer to:

Entertainment

*George Davis (actor) (1889–1965), Dutch-born American actor

*George Davis (art director) (1914–1998), American art director

*George Davis (author) (1939), American novelist

*George Davis (editor) (1906 ...

as director-general. Burnham emphasized architecture and sculpture as central to the fair and assembled the period's top talent to design the buildings and grounds including

Frederick Law Olmsted

Frederick Law Olmsted (April 26, 1822 – August 28, 1903) was an American landscape architect, journalist, Social criticism, social critic, and public administrator. He is considered to be the father of landscape architecture in the U ...

for the grounds.

The temporary buildings were designed in an ornate

neoclassical style and painted white, resulting in the fair site being referred to as the "White City".

The Exposition's offices set up shop in the upper floors of the

Rand McNally Building on Adams Street, the world's first all-steel-framed skyscraper. Davis' team organized the exhibits with the help of

G. Brown Goode of the

Smithsonian. The Midway was inspired by the

1889 Paris Universal Exposition, which included ethnological "villages".

Civil rights leaders protested the refusal to include an African American exhibit.

Frederick Douglass

Frederick Douglass (born Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey, February 14, 1818 – February 20, 1895) was an American social reformer, Abolitionism in the United States, abolitionist, orator, writer, and statesman. He was the most impor ...

,

Ida B. Wells

Ida Bell Wells-Barnett (July 16, 1862 – March 25, 1931) was an American investigative journalist, sociologist, educator, and early leader in the civil rights movement. She was one of the founders of the National Association for the Advance ...

,

Irvine Garland Penn, and

Ferdinand Lee Barnet co-authored a pamphlet entitled "The Reason Why the Colored American is not in the World's Columbian Exposition – The Afro-American's Contribution to Columbian Literature" addressing the issue. Wells and Douglass argued, "when it is asked why we are excluded from the World's Columbian Exposition, the answer is Slavery."

Ten thousand copies of the pamphlet were circulated in the White City from the Haitian Embassy (where Douglass had been selected as its national representative), and the activists received responses from the delegations of England, Germany, France, Russia, and India.

The exhibition did include a limited number of exhibits put on by African Americans, including exhibits by the sculptor

Edmonia Lewis, a painting exhibit by scientist

George Washington Carver

George Washington Carver ( 1864 – January 5, 1943) was an American Agricultural science, agricultural scientist and inventor who promoted alternative crops to cotton and methods to prevent soil depletion. He was one of the most prominent bla ...

, and a statistical exhibit by

Joan Imogen Howard. Black individuals were also featured in white exhibits, such as

Nancy Green's portrayal of the character

Aunt Jemima for the R. T. Davis Milling Company.

Operation

The fair opened in May and ran through October 30, 1893. Forty-six nations participated in the fair, which was the first world's fair to have national pavilions. They constructed exhibits and pavilions and named national "delegates"; for example, Haiti selected

Frederick Douglass

Frederick Douglass (born Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey, February 14, 1818 – February 20, 1895) was an American social reformer, Abolitionism in the United States, abolitionist, orator, writer, and statesman. He was the most impor ...

to be its delegate. The Exposition drew over 27 million visitors. The fair was originally meant to be closed on Sundays, but the

Chicago Woman's Club petitioned that it stay open. The club felt that if the exposition was closed on Sunday, it would restrict those who could not take off work during the work-week from seeing it.

The exposition was located in

Jackson Park and on the

Midway Plaisance

The Midway Plaisance, known locally as the Midway, is a Chicago parks, public park on the Neighborhoods of Chicago#South side, South Side of Chicago, Illinois. It is one mile long by 220 yards wide and extends along 59th and 60th streets, joini ...

on in the neighborhoods of South Shore, Jackson Park Highlands,

Hyde Park, and

Woodlawn.

Charles H. Wacker was the director of the fair. The layout of the fairgrounds was created by Frederick Law Olmsted, and the Beaux-Arts architecture of the buildings was under the direction of Daniel Burnham, Director of Works for the fair. Renowned local architect

Henry Ives Cobb

Henry Ives Cobb (August 19, 1859 – March 27, 1931) was an architect from the United States. Based in Chicago in the last decades of the 19th century, he was known for his designs in the Richardsonian Romanesque and Gothic revival, Victori ...

designed several buildings for the exposition. The director of the American Academy in Rome,

Francis Davis Millet, directed the painted mural decorations. Indeed, it was a coming-of-age for the arts and architecture of the "

American Renaissance", and it showcased the burgeoning neoclassical and

Beaux-Arts styles.

Assassination of mayor and end of fair

The fair ended with the city in shock, as popular mayor

Carter Harrison III was assassinated by

Patrick Eugene Prendergast two days before the fair's closing. Closing ceremonies were canceled in favor of a public memorial service.

Jackson Park was returned to its status as a public park, in much better shape than its original swampy form. The lagoon was reshaped to give it a more natural appearance, except for the straight-line northern end where it still laps up against the steps on the south side of the Palace of Fine Arts/Museum of Science & Industry building. The

Midway Plaisance

The Midway Plaisance, known locally as the Midway, is a Chicago parks, public park on the Neighborhoods of Chicago#South side, South Side of Chicago, Illinois. It is one mile long by 220 yards wide and extends along 59th and 60th streets, joini ...

, a park-like boulevard which extends west from Jackson Park, once formed the southern boundary of the

University of Chicago

The University of Chicago (UChicago, Chicago, or UChi) is a Private university, private research university in Chicago, Illinois, United States. Its main campus is in the Hyde Park, Chicago, Hyde Park neighborhood on Chicago's South Side, Chic ...

, which was being built as the fair was closing (the university has since developed south of the Midway). The university's football team, the Maroons, were the original "

Monsters of the Midway

The Monsters of the Midway is most widely known as the nickname for the National Football League's Chicago Bears. The moniker initially belonged to the Chicago Maroons football , University of Chicago Maroons football team, which was a reference t ...

." The exposition is mentioned in the university's

alma mater

Alma mater (; : almae matres) is an allegorical Latin phrase meaning "nourishing mother". It personifies a school that a person has attended or graduated from. The term is related to ''alumnus'', literally meaning 'nursling', which describes a sc ...

: "The City White hath fled the earth, / But where the azure waters lie, / A nobler city hath its birth, / The City Gray that ne'er shall die."

Attractions

The World's Columbian Exposition was the first world's fair with an

area for amusements that was strictly separated from the exhibition halls. This area, developed by a young music promoter,

Sol Bloom, concentrated on

Midway Plaisance

The Midway Plaisance, known locally as the Midway, is a Chicago parks, public park on the Neighborhoods of Chicago#South side, South Side of Chicago, Illinois. It is one mile long by 220 yards wide and extends along 59th and 60th streets, joini ...

and introduced the term "midway" to American English to describe the area of a carnival or fair where

sideshow

In North America, a sideshow is an extra, secondary production associated with a circus, traveling carnival, carnival, fair, or other such attraction. They historically featured human oddity exhibits (so-called “Freak show, freak shows”), pr ...

s are located.

It included carnival rides, among them the original

Ferris Wheel

A Ferris wheel (also called a big wheel, giant wheel or an observation wheel) is an amusement ride consisting of a rotating upright wheel with multiple passenger-carrying components (commonly referred to as passenger cars, cabins, tubs, gondola ...

, built by

George Washington Gale Ferris Jr.

George Washington Gale Ferris Jr. (February 14, 1859 – November 22, 1896) was an American civil engineer. He is mostly known for creating the original Ferris Wheel for the 1893 Chicago World's Columbian Exposition.

Early life

Ferris was bor ...

This wheel was high and had 36 cars, each of which could accommodate 40 people.

The importance of the Columbian Exposition is highlighted by the use of ' ("Chicago wheel") in many Latin American countries such as Costa Rica and Chile in reference to the

Ferris wheel

A Ferris wheel (also called a big wheel, giant wheel or an observation wheel) is an amusement ride consisting of a rotating upright wheel with multiple passenger-carrying components (commonly referred to as passenger cars, cabins, tubs, gondola ...

. One attendee,

George C. Tilyou, later credited the sights he saw on the Chicago midway for inspiring him to create America's first major amusement park,

Steeplechase Park in

Coney Island

Coney Island is a neighborhood and entertainment area in the southwestern section of the New York City borough of Brooklyn. The neighborhood is bounded by Brighton Beach to its east, Lower New York Bay to the south and west, and Gravesend to ...

, New York.

The fair included life-size reproductions of Christopher Columbus' three ships, the ''

Niña'' (real name ''Santa Clara''), the ''

Pinta'', and the ''

Santa María''. These were intended to celebrate the 400th anniversary of Columbus' discovery of the Americas. The ships were constructed in Spain and then sailed to America for the exposition.

The celebration of Columbus was an intergovernmental project, coordinated by American special envoy

William Eleroy Curtis, the

Queen Regent of Spain, and

Pope Leo XIII

Pope Leo XIII (; born Gioacchino Vincenzo Raffaele Luigi Pecci; 2March 181020July 1903) was head of the Catholic Church from 20 February 1878 until his death in July 1903. He had the fourth-longest reign of any pope, behind those of Peter the Ap ...

. The ships were a very popular exhibit.

Eadweard Muybridge

Eadweard Muybridge ( ; 9 April 1830 – 8 May 1904, born Edward James Muggeridge) was an English photographer known for his pioneering work in photographic studies of motion, and early work in motion-picture Movie projector, projection.

He ...

gave a series of lectures on the Science of Animal Locomotion in the Zoopraxographical Hall, built specially for that purpose on Midway Plaisance. He used his

zoopraxiscope

The zoopraxiscope (initially named ''zoographiscope'' and ''zoogyroscope'') is an early device for displaying moving images and is considered an important predecessor of the movie projector. It was conceived by photographic pioneer Eadweard ...

to show his

moving pictures to a paying public. The hall was the first commercial movie theater.

The "Street in Cairo" included the popular dancer known as

Little Egypt. She introduced America to the suggestive version of the

belly dance known as the "

hootchy-kootchy", to a tune said to have been improvised by Sol Bloom (and now more commonly associated with snake charmers) which he had composed when his dancers had no music to dance to.

Bloom did not copyright the song, putting it immediately in the

public domain

The public domain (PD) consists of all the creative work to which no Exclusive exclusive intellectual property rights apply. Those rights may have expired, been forfeited, expressly Waiver, waived, or may be inapplicable. Because no one holds ...

.

Also included was the first

moving walkway

A moving walkway – also known as an autowalk, moving pavement, moving sidewalk, travolator, or travelator – is a slow-moving conveyor mechanism that transports people across a horizontal or inclined plane, over a short to medium distance. T ...

or travelator, which was designed by architect

Joseph Lyman Silsbee. It had two different divisions: one where passengers were seated, and one where riders could stand or walk. It ran in a loop down the length of a lakefront pier to a casino.

Although denied a spot at the fair,

Buffalo Bill Cody

William Frederick Cody (February 26, 1846January 10, 1917), better known as Buffalo Bill, was an American soldier, bison hunter, and showman. One of the most famous figures of the American Old West, Cody started his legend at the young age o ...

decided to come to Chicago anyway, setting up his ''Buffalo Bill's Wild West Show'' just outside the edge of the exposition. Nearby, historian

Frederick Jackson Turner

Frederick Jackson Turner (November 14, 1861 – March 14, 1932) was an American historian during the early 20th century, based at the University of Wisconsin-Madison until 1910, and then Harvard University. He was known primarily for his front ...

gave academic lectures reflecting on the end of the frontier which Buffalo Bill represented.

The

electrotachyscope

The (from German: 'Electrical Quick-Viewer') or Electrotachyscope is an early motion picture system developed by chronophotographer Ottomar Anschütz between 1886 and 1894. He made at least seven different versions of the machine, including a ...

of

Ottomar Anschütz

Ottomar Anschütz (16 May 1846 – 30 May 1907) was a German inventor, photographer, and chronophotographer.

He is widely seen as an early pioneer in the history of film technology. At the Postfuhramt in Berlin, Anschütz held the first showi ...

was demonstrated, which used a

Geissler tube

A Geissler tube is a precursor to modern gas discharge tubes, demonstrating the principles of electrical glow discharge, akin to contemporary neon lights, and central to the discovery of the electron. This device was developed in 1857 by Hein ...

to project the

illusion

An illusion is a distortion of the senses, which can reveal how the mind normally organizes and interprets sensory stimulation. Although illusions distort the human perception of reality, they are generally shared by most people.

Illusions may ...

of

moving images.

Louis Comfort Tiffany

Louis Comfort Tiffany (February 18, 1848 – January 17, 1933) was an American artist and designer who worked in the decorative arts and is best known for his work in stained glass. He is associated with the art nouveauLander, David"The Buyable ...

made his reputation with a stunning chapel designed and built for the Exposition. After the Exposition the

Tiffany Chapel was sold several times, even going back to Tiffany's estate. It was eventually reconstructed and restored and in 1999 it was installed at the

Charles Hosmer Morse Museum of American Art

The Charles Hosmer Morse Museum of American Art, a museum noted for its Art Nouveau collection, houses the most comprehensive collection of the works of Louis Comfort Tiffany found anywhere, a major collection of American art pottery, and fine ...

.

Architect

Kirtland Cutter's

Idaho Building, a rustic log construction, was a popular favorite, visited by an estimated 18 million people. The building's design and interior furnishings were a major precursor of the

Arts and Crafts movement

The Arts and Crafts movement was an international trend in the decorative and fine arts that developed earliest and most fully in the British Isles and subsequently spread across the British Empire and to the rest of Europe and America.

Initiat ...

.

The event also held a notable "hoochie coochie" dance show which led to Bloom becoming one of the earliest people in U.S. history to make large sums of money off of shows which were reminiscent of

striptease

A striptease is an erotic or exotic dance in which the performer gradually undresses, either partly or completely, in a seductive and sexually suggestive manner. The person who performs a striptease is commonly known as a "stripper", "exotic d ...

s.

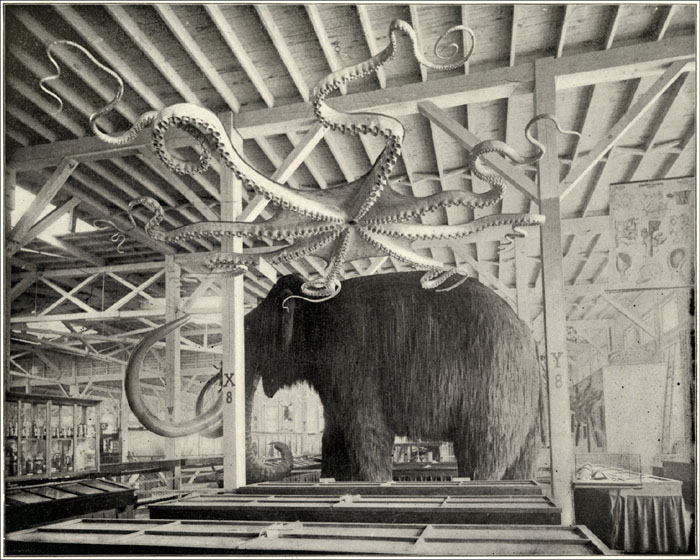

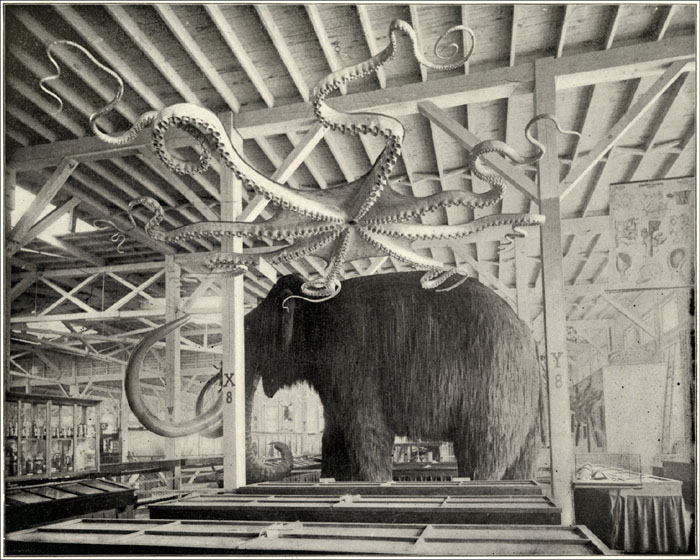

Anthropology

There was an Anthropology Building at the World's Fair. Nearby, "The Cliff Dwellers" featured a rock and timber structure that was painted to recreate Battle Rock Mountain in Colorado, a stylized recreation of an American Indian cliff dwelling with pottery, weapons, and other relics on display.

[Joseph M. Di Cola & David Stone (2012]

Chicago's 1893 World's Fair

, page 21 There was also an

Eskimo

''Eskimo'' () is a controversial Endonym and exonym, exonym that refers to two closely related Indigenous peoples: Inuit (including the Alaska Native Iñupiat, the Canadian Inuit, and the Greenlandic Inuit) and the Yupik peoples, Yupik (or Sibe ...

display. There were also birch bark

wigwam

A wigwam, wikiup, wetu (Wampanoag), or wiigiwaam (Ojibwe, in syllabics: ) is a semi-permanent domed dwelling formerly used by certain Native American tribes and First Nations people and still used for ceremonial events. The term ''wikiup'' ...

s of the

Penobscot

The Penobscot (Abenaki: ''Pαnawάhpskewi'') are an Indigenous people in North America from the Northeastern Woodlands region. They are organized as a federally recognized tribe in Maine and as a First Nations band government in the Atlantic p ...

tribe. Nearby was a working model Indian school, organized by the Office of Indian Affairs, that housed delegations of Native American students and their teachers from schools around the country for weeks at a time.

Rail

The ''

John Bull

John Bull is a national personification of England, especially in political cartoons and similar graphic works. He is usually depicted as a stout, middle-aged, country-dwelling, jolly and matter-of-fact man. He originated in satirical works of ...

'' locomotive was displayed. It was only 62 years old, having been built in 1831. It was the first locomotive acquisition by the

Smithsonian Institution

The Smithsonian Institution ( ), or simply the Smithsonian, is a group of museums, Education center, education and Research institute, research centers, created by the Federal government of the United States, U.S. government "for the increase a ...

. The locomotive ran under its own power from

Washington, DC

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly known as Washington or D.C., is the capital city and Federal district of the United States, federal district of the United States. The city is on the Potomac River, across from ...

, to Chicago to participate, and returned to Washington under its own power again when the exposition closed. In 1981 it was the oldest surviving operable

steam locomotive

A steam locomotive is a locomotive that provides the force to move itself and other vehicles by means of the expansion of steam. It is fuelled by burning combustible material (usually coal, Fuel oil, oil or, rarely, Wood fuel, wood) to heat ...

in the world when it ran under its own power again.

A

Baldwin 2-4-2 locomotive was showcased at the exposition, and subsequently the type was known as the ''Columbia''.

An original

frog

A frog is any member of a diverse and largely semiaquatic group of short-bodied, tailless amphibian vertebrates composing the order (biology), order Anura (coming from the Ancient Greek , literally 'without tail'). Frog species with rough ski ...

switch and portion of the superstructure of the famous 1826

Granite Railway

The Granite Railway was one of the first railroads in the United States, built to carry granite from Quincy, Massachusetts, to a dock on the Neponset River in Milton. From there boats carried the heavy stone to Charlestown for construction ...

in Massachusetts could be viewed. This was the first commercial railroad in the United States to evolve into a

common carrier

A common carrier in common law countries (corresponding to a public carrier in some civil law (legal system), civil law systems,Encyclopædia Britannica CD 2000 "Civil-law public carrier" from "carriage of goods" usually called simply a ''carrier ...

without an intervening closure. The railway brought granite stones from a rock quarry in

Quincy, Massachusetts

Quincy ( ) is a city in Norfolk County, Massachusetts, Norfolk County, Massachusetts, United States. It is the largest city in the county. Quincy is part of the Greater Boston area as one of Boston's immediate southern suburbs. Its population in ...

, so that the

Bunker Hill Monument

The Bunker Hill Monument is a monument erected at the site of the Battle of Bunker Hill in Boston, Massachusetts, which was among the first major battles between the United Colonies and the British Empire in the American Revolutionary War. The 2 ...

could be erected in Boston. The frog switch is now on public view in

East Milton Square, Massachusetts, on the original

right-of-way of the Granite Railway.

Transportation by rail was the major mode of transportation. A 26-track train station was built at the southwest corner of the fair. While trains from around the country would unload there, there was a local train to shuttle tourists from the Chicago Grand Central Station to the fair. The newly built

Chicago and South Side Rapid Transit Railroad

The South Side Elevated Railroad (originally Chicago and South Side Rapid Transit Railroad) was the first elevated rapid transit line in Chicago, Illinois. The line ran from downtown Chicago to East 63rd branch (CTA), Jackson Park, with branches ...

also served passengers from

Congress Terminal to the fairgrounds at

Jackson Park. The line exists today as part of the

CTA Green Line.

Country and state exhibition buildings

Forty-six countries had pavilions at the exposition.

Norway

Norway, officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic countries, Nordic country located on the Scandinavian Peninsula in Northern Europe. The remote Arctic island of Jan Mayen and the archipelago of Svalbard also form part of the Kingdom of ...

participated by sending the ''

Viking

Vikings were seafaring people originally from Scandinavia (present-day Denmark, Norway, and Sweden),

who from the late 8th to the late 11th centuries raided, pirated, traded, and settled throughout parts of Europe.Roesdahl, pp. 9� ...

'', a replica of the

Gokstad ship

The Gokstad ship is a 9th-century Viking ship found in a burial mound at Gokstad in Sandar, Norway, Sandar, Sandefjord, Vestfold, Norway. It is displayed at the Viking Ship Museum (Oslo), Viking Ship Museum in Oslo, Norway. It is the largest pr ...

. It was built in Norway and sailed across the

Atlantic Ocean

The Atlantic Ocean is the second largest of the world's five borders of the oceans, oceanic divisions, with an area of about . It covers approximately 17% of Earth#Surface, Earth's surface and about 24% of its water surface area. During the ...

by 12 men, led by Captain Magnus Andersen. In 1919, this ship was moved to

Lincoln Park

Lincoln Park is a park along Lake Michigan on the North Side of Chicago, Illinois. Named after US president Abraham Lincoln, it is the city's largest public park and stretches for from Grand Avenue (500 N), on the south, to near Ardmore Avenu ...

. It was relocated in 1996 to Good Templar Park in

Geneva, Illinois

Geneva is a city in and the county seat of Kane County, Illinois, United States. It is located in the far western side of the Chicago suburbs. Per the 2020 United States Census, 2020 census, the population was 21,393.

Geneva is part of a Tri-Ci ...

, where it awaits renovation.

Thirty-four U.S. states also had their own pavilions.

The work of noted feminist author

Kate McPhelim Cleary was featured during the opening of the Nebraska Day ceremonies at the fair, which included a reading of her poem "Nebraska". Among the state buildings present at the fair were California, Colorado, Connecticut, Florida, Massachusetts, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, and Texas; each was meant to be architecturally representative of the corresponding states.

Four

United States territories

Territories of the United States are sub-national administrative divisions and dependent territories overseen by the federal government of the United States. The American territories differ from the U.S. states and Indian reservations in th ...

also had pavilions located in one building:

Arizona

Arizona is a U.S. state, state in the Southwestern United States, Southwestern region of the United States, sharing the Four Corners region of the western United States with Colorado, New Mexico, and Utah. It also borders Nevada to the nort ...

,

New Mexico

New Mexico is a state in the Southwestern United States, Southwestern region of the United States. It is one of the Mountain States of the southern Rocky Mountains, sharing the Four Corners region with Utah, Colorado, and Arizona. It also ...

,

Oklahoma

Oklahoma ( ; Choctaw language, Choctaw: , ) is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States. It borders Texas to the south and west, Kansas to the north, Missouri to the northea ...

, and

Utah

Utah is a landlocked state in the Mountain states, Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. It is one of the Four Corners states, sharing a border with Arizona, Colorado, and New Mexico. It also borders Wyoming to the northea ...

.

Visitors to the Louisiana Pavilion were each given a seedling of a cypress tree. This resulted in the spread of cypress trees to areas where they were not native. Cypress trees from those seedlings can be found in many areas of West Virginia, where they flourish in the climate.

The

''Illinois'' was a detailed, full-scale mockup of an

''Indiana''-class battleship, constructed as a naval exhibit.

Guns and artillery

The German firm

Krupp

Friedrich Krupp AG Hoesch-Krupp (formerly Fried. Krupp AG and Friedrich Krupp GmbH), trade name, trading as Krupp, was the largest company in Europe at the beginning of the 20th century as well as Germany's premier weapons manufacturer dur ...

had a pavilion of artillery, which apparently had cost one million dollars to stage,

including a coastal gun of 42 cm in bore (16.54 inches) and a length of 33 calibres (45.93 feet, 14 meters). A breech-loaded gun, it weighed 120.46

long ton

The long ton, also known as the imperial ton, displacement ton,Dictionary.com - ''"a unit for measuring the displacement of a vessel, equal to a long ton of 2240 pounds (about 1016 kg) or 35 cu. ft. (1 cu. m) of seawater."'' or British ton, is a ...

s (122.4 metric tons). According to the company's marketing: "It carried a charge projectile weighing from 2,200 to 2,500 pounds which, when driven by 900 pounds of

brown powder, was claimed to be able to penetrate at 2,200 yards a wrought-iron plate three feet thick if placed at right angles."

Nicknamed "The Thunderer", the gun had an advertised range of 15 miles. On this occasion

John Schofield declared Krupps' guns "the greatest peacemakers in the world".

This gun was later seen as a precursor of the company's World War I

Dicke Berta howitzers.

Religions

The 1893

Parliament of the World's Religions

There have been several meetings referred to as a Parliament of the World's Religions, the first being the World's Parliament of Religions of 1893, which was an attempt to create a global dialogue of faiths. The event was celebrated by another c ...

, which ran from September 11 to September 27, marked the first formal gathering of representatives of Eastern and Western spiritual traditions from around the world. According to

Eric J. Sharpe

Eric John Sharpe (19 September 1933 – 19 October 2000) was the founding Professor of Religious Studies at the University of Sydney, Australia. He was a major scholar in the Phenomenology (philosophy), phenomenology of religion, the history of m ...

,

Tomoko Masuzawa, and others, the event was considered radical at the time, since it allowed non-Christian faiths to speak on their own behalf.

For example, it is recognized as the first public mention of the

Baháʼí Faith

The Baháʼí Faith is a religion founded in the 19th century that teaches the Baháʼí Faith and the unity of religion, essential worth of all religions and Baháʼí Faith and the unity of humanity, the unity of all people. Established by ...

in North America;

it was not taken seriously by European scholars until the 1960s.

Moving walkway

Along the banks of the lake, patrons on the way to the casino were taken on a

moving walkway

A moving walkway – also known as an autowalk, moving pavement, moving sidewalk, travolator, or travelator – is a slow-moving conveyor mechanism that transports people across a horizontal or inclined plane, over a short to medium distance. T ...

designed by architect

Joseph Lyman Silsbee, the first of its kind open to the public, called ''The Great Wharf, Moving Sidewalk'', it allowed people to walk along or ride in seats.

Horticulture

Horticultural exhibits at the Horticultural Hall included

cacti

A cactus (: cacti, cactuses, or less commonly, cactus) is a member of the plant family Cactaceae (), a family of the order Caryophyllales comprising about 127 genera with some 1,750 known species. The word ''cactus'' derives, through Latin, ...

and

orchid

Orchids are plants that belong to the family Orchidaceae (), a diverse and widespread group of flowering plants with blooms that are often colourful and fragrant. Orchids are cosmopolitan plants that are found in almost every habitat on Eart ...

s as well as other plants in a

greenhouse

A greenhouse is a structure that is designed to regulate the temperature and humidity of the environment inside. There are different types of greenhouses, but they all have large areas covered with transparent materials that let sunlight pass an ...

.

Architecture

White City

Most of the buildings of the fair were designed in the

neoclassical architecture

Neoclassical architecture, sometimes referred to as Classical Revival architecture, is an architectural style produced by the Neoclassicism, Neoclassical movement that began in the mid-18th century in Italy, France and Germany. It became one of t ...

style. The area at the Court of Honor was known as The White City. Façades were made not of stone, but of a mixture of plaster, cement, and jute fiber called

staff, which was painted white, giving the buildings their "gleam". Architecture critics derided the structures as "decorated sheds." The buildings were clad in white

stucco

Stucco or render is a construction material made of aggregates, a binder, and water. Stucco is applied wet and hardens to a very dense solid. It is used as a decorative coating for walls and ceilings, exterior walls, and as a sculptural and ...

, which, in comparison to the

tenement

A tenement is a type of building shared by multiple dwellings, typically with flats or apartments on each floor and with shared entrance stairway access. They are common on the British Isles, particularly in Scotland. In the medieval Old Town, E ...

s of Chicago, seemed illuminated. It was also called the White City because of the extensive use of street lights, which made the boulevards and buildings usable at night.

In 1892, working under extremely tight deadlines to complete construction, director of works Daniel Burnham appointed

Francis Davis Millet to replace the fair's official director of color-design, William Pretyman. Pretyman had resigned following a dispute with Burnham. After experimenting, Millet settled on a mix of oil and white lead

whitewash

Whitewash, calcimine, kalsomine, calsomine, asbestis or lime paint is a type of paint made from slaked lime ( calcium hydroxide, Ca(OH)2) or chalk (calcium carbonate, CaCO3), sometimes known as "whiting". Various other additives are sometimes ...

that could be applied using compressed air

spray paint

Spray paint (formally aerosol paint) is paint that comes in a sealed, pressurized can and is released in an aerosol spray when a valve button is depressed. The propellant is what the container of pressurized gas is called. When the pressure hol ...

ing to the buildings, taking considerably less time than traditional brush painting.

Joseph Binks, maintenance supervisor at Chicago's

Marshall Field's Wholesale Store, who had been using this method to apply whitewash to the subbasement walls of the store, got the job to paint the Exposition buildings. Claims this was the first use of spray painting may be apocryphal since journals from that time note this form of painting had already been in use in the railroad industry from the early 1880s.

Many of the buildings included sculptural details and, to meet the Exposition's opening deadline, chief architect Burnham sought the help of

Chicago Art Institute instructor

Lorado Taft

Lorado Zadok Taft (April 29, 1860 – October 30, 1936) was an American sculptor, writer and educator. Part of the American Renaissance movement, his monumental pieces include, ''Fountain of Time'', ''Spirit of the Great Lakes'', and ''The ...

to help complete them. Taft's efforts included employing a group of talented women sculptors from the Institute known as "the

White Rabbits" to finish some of the buildings, getting their name from Burnham's comment "Hire anyone, even white rabbits if they'll do the work."

The words "Thine alabaster cities gleam" from the song "

America the Beautiful

"America the Beautiful" is an American patriotic song. Its lyrics were written by Katharine Lee Bates and its music was composed by church organist and choirmaster Samuel A. Ward at Grace Church (Newark), Grace Episcopal Church in Newark, New ...

" were inspired by the White City.

Role in the City Beautiful movement

The White City is largely credited for ushering in the

City Beautiful movement

The City Beautiful movement was a reform philosophy of North American architecture and urban planning that flourished during the 1890s and 1900s with the intent of introducing beautification and monumental grandeur in cities. It was a part of th ...

and planting the seeds of modern city planning. The highly integrated design of the landscapes, promenades, and structures provided a vision of what is possible when planners, landscape architects, and architects work together on a comprehensive design scheme.

The White City inspired cities to focus on the beautification of the components of the city in which municipal government had control; streets, municipal art, public buildings, and public spaces. The designs of the City Beautiful Movement (closely tied with the municipal art movement) are identifiable by their classical architecture, plan symmetry, picturesque views, and axial plans, as well as their magnificent scale. Where the municipal art movement focused on beautifying one feature in a city, the City Beautiful movement began to make improvements on the scale of the district. The White City of the World's Columbian Exposition inspired the

Merchants Club of Chicago to commission

Daniel Burnham

Daniel Hudson Burnham (September 4, 1846 – June 1, 1912) was an American architect and urban designer. A proponent of the ''Beaux-Arts architecture, Beaux-Arts'' movement, he may have been "the most successful power broker the American archi ...

to create the Plan of Chicago in 1909.

Great buildings

There were fourteen main "great buildings"

centered around a giant reflective pool called the Grand Basin. Buildings included:

* The Administration Building, designed by

Richard Morris Hunt

Richard Morris Hunt (October 31, 1827 – July 31, 1895) was an American architect of the nineteenth century and an eminent figure in the history of architecture of the United States. He helped shape New York City with his designs for the 1902 ...

* The Agricultural Building, designed by

Charles McKim of

McKim, Mead & White

McKim, Mead & White was an American architectural firm based in New York City. The firm came to define architectural practice, urbanism, and the ideals of the American Renaissance in ''fin de siècle'' New York.

The firm's founding partners, Cha ...

* The Manufactures and Liberal Arts Building, designed by

George B. Post

George Browne Post (December15, 1837November28, 1913) was an American architect trained in the Beaux-Arts tradition. Active from 1869 almost until his death, he was recognized as a master of several contemporary American architectural genres, an ...

. If this building were standing today, it would rank third in volume (8,500,000m

3) and eighth in footprint (130,000 m

2) on

list of largest buildings

Buildings around the world listed by usable space (volume), footprint (area), and floor space (area) comprise single structures that are suitable for continuous human occupancy. There are, however, some Nonbuilding structure#Exceptions, exception ...

.

It exhibited works related to literature, science, art and music.

* The Mines and Mining Building, designed by

Solon Spencer Beman

* The Electricity Building, designed by

Henry Van Brunt and

Frank Maynard Howe

* The Machinery Hall, designed by

Robert Swain Peabody of Peabody and Stearns

*

The Woman's Building, designed by

Sophia Hayden

* The Transportation Building, designed by

Adler & Sullivan

Adler & Sullivan was an architectural firm founded by Dankmar Adler and Louis Sullivan in Chicago. Among its projects was the multi-purpose Auditorium Building in Chicago and the Wainwright Building skyscraper in St Louis. In 1883 Louis Sullivan ...

* The Fisheries Building designed by

Henry Ives Cobb

Henry Ives Cobb (August 19, 1859 – March 27, 1931) was an architect from the United States. Based in Chicago in the last decades of the 19th century, he was known for his designs in the Richardsonian Romanesque and Gothic revival, Victori ...

* Forestry Building designed by

Charles B. Atwood

* Horticultural Building designed by

Jenney and Mundie

* Anthropology Building designed by

Charles B. Atwood

Transportation Building

Louis Sullivan

Louis Henry Sullivan (September 3, 1856 – April 14, 1924) was an American architect, and has been called a "father of skyscrapers" and "father of modernism". He was an influential architect of the Chicago school (architecture), Chicago ...

's polychrome proto-Modern Transportation Building was an outstanding exception to the prevailing style, as he tried to develop an organic American form. Years later, in 1922, he wrote that the classical style of the White City had set back modern American architecture by forty years.

As detailed in

Erik Larson's popular history ''

The Devil in the White City

''The Devil in the White City: Murder, Magic, and Madness at the Fair That Changed America'' is a 2003 historical non-fiction book by Erik Larson presented in a novelistic style. Set in Chicago during the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition, it ...

'', extraordinary effort was required to accomplish the exposition, and much of it was unfinished on opening day. The famous

Ferris Wheel

A Ferris wheel (also called a big wheel, giant wheel or an observation wheel) is an amusement ride consisting of a rotating upright wheel with multiple passenger-carrying components (commonly referred to as passenger cars, cabins, tubs, gondola ...

, which proved to be a major attendance draw and helped save the fair from bankruptcy, was not finished until June, because of waffling by the board of directors the previous year on whether to build it. Frequent debates and disagreements among the developers of the fair added many delays. The spurning of

Buffalo Bill

William Frederick Cody (February 26, 1846January 10, 1917), better known as Buffalo Bill, was an American soldier, bison hunter, and showman. One of the most famous figures of the American Old West, Cody started his legend at the young age ...

's Wild West Show proved a serious financial mistake. Buffalo Bill set up his highly popular show next door to the fair and brought in a great deal of revenue that he did not have to share with the developers. Nonetheless, construction and operation of the fair proved to be a windfall for Chicago workers during the serious economic recession that was sweeping the country.

Surviving structures

File:1893 Nina Pinta Santa Maria replicas.jpg, alt=Nina, Pinta, Santa Maria replicas., '' Pinta'', '' Santa María'', and '' Niña'' replicas from Spain.

File:Viking, replica of the Gokstad Viking ship, at the Chicago World Fair 1893.jpg, alt=Viking, replica of the Gokstad Viking ship., ''Viking

Vikings were seafaring people originally from Scandinavia (present-day Denmark, Norway, and Sweden),

who from the late 8th to the late 11th centuries raided, pirated, traded, and settled throughout parts of Europe.Roesdahl, pp. 9� ...

'', a replica of the Gokstad ship

The Gokstad ship is a 9th-century Viking ship found in a burial mound at Gokstad in Sandar, Norway, Sandar, Sandefjord, Vestfold, Norway. It is displayed at the Viking Ship Museum (Oslo), Viking Ship Museum in Oslo, Norway. It is the largest pr ...

.

File:Chicago expo White City fire.jpg, alt=White City fire, After the fair, the White City on fire.

Almost all of the fair's structures were designed to be temporary; of the more than 200 buildings erected for the fair, the only two which still stand in place are the

Palace of Fine Arts

The Palace of Fine Arts is a monumental structure located in the Marina District of San Francisco, California, originally built for the 1915 Panama–Pacific International Exposition to exhibit works of art. Completely rebuilt from 1964 to 197 ...

and the

World's Congress Auxiliary Building. From the time the fair closed until 1920, the Palace of Fine Arts housed the Field Columbian Museum (now the

Field Museum of Natural History

The Field Museum of Natural History (FMNH), also known as The Field Museum, is a natural history museum in Chicago, Illinois, and is one of the largest such museums in the world. The museum is popular for the size and quality of its educationa ...

, since relocated); in 1933 (having been completely rebuilt in permanent materials), the Palace building re-opened as the

Museum of Science and Industry. The second building, the World's Congress Building, was one of the few buildings not built in Jackson Park, instead it was built downtown in

Grant Park. The cost of construction of the World's Congress Building was shared with the

Art Institute of Chicago

The Art Institute of Chicago, founded in 1879, is one of the oldest and largest art museums in the United States. The museum is based in the Art Institute of Chicago Building in Chicago's Grant Park (Chicago), Grant Park. Its collection, stewa ...

, which, as planned, moved into the building (the museum's current home) after the close of the fair.

The three other significant buildings that survived the fair represented Norway, the Netherlands, and the State of Maine. The

Norway

Norway, officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic countries, Nordic country located on the Scandinavian Peninsula in Northern Europe. The remote Arctic island of Jan Mayen and the archipelago of Svalbard also form part of the Kingdom of ...

Building was a recreation of a traditional wooden

stave church

A stave church is a medieval wooden Christian church building once common in north-western Europe. The name derives from the building's structure of post and lintel construction, a type of timber framing where the load-bearing ore-pine posts ...

. After the Fair it was relocated to Lake Geneva, and in 1935 was moved to a museum called

Little Norway in

Blue Mounds, Wisconsin. In 2015 it was dismantled and shipped back to Norway, where it was restored and reassembled. The second is the

Maine State Building, designed by Charles Sumner Frost, which was purchased by the Ricker family of

Poland Spring, Maine. They moved the building to their resort to serve as a library and art gallery. The Poland Spring Preservation Society now owns the building, which was listed on the

National Register of Historic Places

The National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) is the Federal government of the United States, United States federal government's official United States National Register of Historic Places listings, list of sites, buildings, structures, Hist ...

in 1974. The third is

The Dutch House, which was moved to

Brookline, Massachusetts

Brookline () is an affluent town in Norfolk County, Massachusetts, United States, and part of the Greater Boston, Boston metropolitan area. An exclave of Norfolk County, Brookline borders six of Boston's neighborhoods: Brighton, Boston, Brighton ...

.

The

1893 Viking ship that was sailed to the Exposition from Norway by Captain Magnus Andersen is located in

Geneva, Illinois

Geneva is a city in and the county seat of Kane County, Illinois, United States. It is located in the far western side of the Chicago suburbs. Per the 2020 United States Census, 2020 census, the population was 21,393.

Geneva is part of a Tri-Ci ...

. The ship is open to visitors on scheduled days April through October.

The main altar at

St. John Cantius in Chicago, as well as its matching two side altars, are reputed to be from the Columbian Exposition.

Since many of the other buildings at the fair were intended to be temporary, they were removed after the fair. The White City so impressed visitors (at least before air pollution began to darken the façades) that plans were considered to refinish the exteriors in marble or some other material. These plans were abandoned in July 1894, when much of the fair grounds was destroyed in a fire.

Gallery

File:Chi-fair-13-20080924.jpg, The Administration Building and Grand Court during the October 9, 1893, commemoration of the 22nd anniversary of the Chicago Fire.

File:Chicago expo Manufactures bldg.jpg, The Manufactures and Liberal Arts Building, seen from the southwest.

File:Chicago expo Horticultural bldg.jpg, Horticultural Building, with Illinois Building in the background.

File:Chicago expo Machinery Hall.jpg, A view toward the Peristyle from Machinery Hall.

File:Chicago expo Midway Plaisance.jpg, Midway Plaisance

File:The World's Columbian exposition, Chicago, 1893 (1893) (14593740420).jpg, Frederick MacMonnies' Columbian Fountain.

File:columex.jpg, "Canal of Venice" during Chicago World's Fair 1893

File:Die Gartenlaube (1893) b 417.jpg, President Cleveland opens the World's Fair, as depicted by Rudolf Cronau in 1893

Later criticisms

Frank Lloyd Wright

Frank Lloyd Wright Sr. (June 8, 1867 – April 9, 1959) was an American architect, designer, writer, and educator. He designed List of Frank Lloyd Wright works, more than 1,000 structures over a creative period of 70 years. Wright played a key ...

later wrote that "By this overwhelming rise of grandomania I was confirmed in my fear that a native architecture would be set back at least fifty years."

According to

University of Notre Dame

The University of Notre Dame du Lac (known simply as Notre Dame; ; ND) is a Private university, private Catholic research university in Notre Dame, Indiana, United States. Founded in 1842 by members of the Congregation of Holy Cross, a Cathol ...

history professor Gail Bederman, the event symbolized a male-dominated and Eurocentrist society. In her 1995 text ''Manliness and Civilization'', she writes, "The White City, with its vision of future perfection and of the advanced racial power of manly commerce and technology, constructed civilization as an ideal of white male power."

According to Bederman, people of color were barred entirely from participating in the organization of the White City and were instead given access only to the Midway exhibit, "which specialized in spectacles of barbarous races – 'authentic' villages of Samoans, Egyptians, Dahomans, Turks, and other exotic peoples, populated by actual imported 'natives.'"

Two small exhibits were included in the White City's "Woman's Building" which addressed women of color. One, entitled "Afro-American" was installed in a distant corner of the building.

The other, called "Woman's Work in Savagery," included baskets, weavings, and African, Polynesian, and Native American arts. Though they were produced by living women of color, the materials were represented as relics from the distant past, embodying "the work of white women's own distant evolutionary foremothers."

Visitors

Helen Keller

Helen Adams Keller (June 27, 1880 – June 1, 1968) was an American author, disability rights advocate, political activist and lecturer. Born in West Tuscumbia, Alabama, she lost her sight and her hearing after a bout of illness when ...

, along with her mentor

Anne Sullivan and Dr.

Alexander Graham Bell

Alexander Graham Bell (; born Alexander Bell; March 3, 1847 – August 2, 1922) was a Scottish-born Canadian Americans, Canadian-American inventor, scientist, and engineer who is credited with patenting the first practical telephone. He als ...

, visited the fair in summer 1893. Keller described the fair in her autobiography ''

The Story of My Life''. Early in July, a

Wellesley College

Wellesley College is a Private university, private Women's colleges in the United States, historically women's Liberal arts colleges in the United States, liberal arts college in Wellesley, Massachusetts, United States. Founded in 1870 by Henr ...

English teacher named

Katharine Lee Bates

Katharine Lee Bates (August 12, 1859 – March 28, 1929) was an American author and poet, chiefly remembered for her anthem "America the Beautiful", but also for her many books and articles on social reform, on which she was a noted speaker.

B ...

visited the fair. The White City later inspired the reference to "alabaster cities" in her poem and lyrics "

America the Beautiful

"America the Beautiful" is an American patriotic song. Its lyrics were written by Katharine Lee Bates and its music was composed by church organist and choirmaster Samuel A. Ward at Grace Church (Newark), Grace Episcopal Church in Newark, New ...

". The exposition was extensively reported by Chicago publisher

William D. Boyce's reporters and artists.

There is a very detailed and vivid description of all facets of this fair by the

Persian

Persian may refer to:

* People and things from Iran, historically called ''Persia'' in the English language

** Persians, the majority ethnic group in Iran, not to be conflated with the Iranic peoples

** Persian language, an Iranian language of the ...

traveler Mirza Mohammad Ali Mo'in ol-Saltaneh written in

Persian

Persian may refer to:

* People and things from Iran, historically called ''Persia'' in the English language

** Persians, the majority ethnic group in Iran, not to be conflated with the Iranic peoples

** Persian language, an Iranian language of the ...

. He departed from

Persia

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran (IRI) and also known as Persia, is a country in West Asia. It borders Iraq to the west, Turkey, Azerbaijan, and Armenia to the northwest, the Caspian Sea to the north, Turkmenistan to the nort ...

on April 20, 1892, especially for the purpose of visiting the World's Columbian Exposition.

Pierre de Coubertin

Charles Pierre de Frédy, Baron de Coubertin (; born Pierre de Frédy; 1 January 1863 – 2 September 1937), also known as Pierre de Coubertin and Baron de Coubertin, was a French educator and historian, co-founder of the International Olympic ...

visited the fair with his friends

Paul Bourget and

Samuel Jean de Pozzi. He devotes the first chapter of his book ''Souvenirs d'Amérique et de Grèce'' (1897) to the visit.

Swami Vivekananda

Swami Vivekananda () (12 January 1863 – 4 July 1902), born Narendranath Datta, was an Indian Hindus, Hindu monk, philosopher, author, religious teacher, and the chief disciple of the Indian mystic Ramakrishna. Vivekananda was a major figu ...

visited the fair to attend the

Parliament of the World's Religions

There have been several meetings referred to as a Parliament of the World's Religions, the first being the World's Parliament of Religions of 1893, which was an attempt to create a global dialogue of faiths. The event was celebrated by another c ...

and delivered his famous speech ''Sisters and Brothers of America!''.

Kubota Beisen was an official delegate of Japan. As an artist, he sketched hundreds of scenes, some of which were later used to make woodblock print books about the Exhibition. Serial killer

H. H. Holmes attended the fair with two of his eventual victims, Annie and Minnie Williams.

Bulgaria

Bulgaria, officially the Republic of Bulgaria, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern portion of the Balkans directly south of the Danube river and west of the Black Sea. Bulgaria is bordered by Greece and Turkey t ...

n writer

Aleko Konstantinov

Aleko Konstantinov () (1 January 1863 – 11 May 1897) ( NS: 13 January 1863 – 23 May 1897) was a Bulgarian writer, best known for his character Bay Ganyo, one of the most popular characters in Bulgarian fiction.

Life and career

Born to an ...

visited the fair and wrote his

nonfiction

Non-fiction (or nonfiction) is any document or media content that attempts, in good faith, to convey information only about the real world, rather than being grounded in imagination. Non-fiction typically aims to present topics objectively ...

book ''

To Chicago and Back''.

Souvenirs

Examples of exposition souvenirs can be found in various American museum collections. One example, copyrighted in 1892 by John W. Green, is a folding

hand fan

A handheld fan, or simply hand fan, is a broad, flat surface that is waved back and forth to create an airflow. Generally, purpose-made handheld fans are folding fans, which are shaped like a Circular sector, sector of a circle and made of a thi ...

with detailed illustrations of landscapes and architecture. Charles W Goldsmith produced a set of ten postcard designs, each in full colour, showing the buildings constructed for the exhibition.

Columbian Exposition coins were also minted for the event.

Electricity

The effort to power the Fair with electricity, which became a demonstration piece for

Westinghouse Electric

The Westinghouse Electric Corporation was an American manufacturing company founded in 1886 by George Westinghouse and headquartered in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. It was originally named "Westinghouse Electric & Manufacturing Company" and was ...

and the

alternating current

Alternating current (AC) is an electric current that periodically reverses direction and changes its magnitude continuously with time, in contrast to direct current (DC), which flows only in one direction. Alternating current is the form in w ...

system they had been developing for many years, took place at the end of what has been called the

War of the currents

The war of the currents was a series of events surrounding the introduction of competing electric power transmission systems in the late 1880s and early 1890s. It grew out of two lighting systems developed in the late 1870s and early 1880s: arc l ...

between DC and AC. Westinghouse initially did not put in a bid to power the Fair but agreed to be the contractor for a local Chicago company that put in a low bid of US$510,000 to supply an alternating current-based system.

[Richard Moran (2007) ''Executioner's Current: Thomas Edison, George Westinghouse, and the Invention of the Electric Chair'', Knopf Doubleday, p. 97]

Edison General Electric, which at the time was merging with the

Thomson-Houston Electric Company

The Thomson-Houston Electric Company was a manufacturing company that was one of the precursors of General Electric.

History

The company began as the American Electric Company, founded by Elihu Thomson and Edwin Houston. In 1882, Charles Al ...

to form

General Electric

General Electric Company (GE) was an American Multinational corporation, multinational Conglomerate (company), conglomerate founded in 1892, incorporated in the New York (state), state of New York and headquartered in Boston.

Over the year ...

, put in a US$1.72 million bid to power the Fair and its planned 93,000 incandescent lamps with

direct current

Direct current (DC) is one-directional electric current, flow of electric charge. An electrochemical cell is a prime example of DC power. Direct current may flow through a conductor (material), conductor such as a wire, but can also flow throug ...

. After the Fair committee went over both proposals, Edison General Electric re-bid their costs at $554,000 but Westinghouse underbid them by 70 cents per lamp to get the contract.

[Quentin R. Skrabec, ''George Westinghouse: Gentle Genius'', pp. 135–137] Westinghouse could not use the Edison incandescent lamp since the patent belonged to General Electric and they had successfully sued to stop use of all patent infringing designs. Since Edison specified a sealed globe of glass in his design Westinghouse found a way to sidestep the Edison patent by quickly developing a lamp with a ground-glass stopper in one end, based on a Sawyer-Man "stopper" lamp patent they already had. The lamps worked well but were short-lived, requiring a small army of workmen to constantly replace them.

Westinghouse Electric had severely underbid the contract and struggled to supply all the equipment specified, including twelve 1,000-horsepower single-phase AC generators and all the lighting and other equipment required. They also had to fend off a last-minute lawsuit by General Electric claiming the Westinghouse Sawyer-Man-based stopper lamp infringed on the Edison incandescent lamp patent.

The International Exposition was held in an Electricity Building which was devoted to electrical exhibits. A statue of

Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin (April 17, 1790) was an American polymath: a writer, scientist, inventor, statesman, diplomat, printer, publisher and Political philosophy, political philosopher.#britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Wood, 2021 Among the m ...

was displayed at the entrance. The exposition featured interior and exterior light and displays as well as displays of

Thomas Edison

Thomas Alva Edison (February11, 1847October18, 1931) was an American inventor and businessman. He developed many devices in fields such as electric power generation, mass communication, sound recording, and motion pictures. These inventions, ...

's

kinetoscope

The Kinetoscope is an early motion picture exhibition device, designed for films to be viewed by one person at a time through a peephole viewer window. The Kinetoscope was not a movie projector, but it introduced the basic approach that woul ...

,

search light

Searching may refer to:

Music

* " Searchin", a 1957 song originally performed by The Coasters

* "Searching" (China Black song), a 1991 song by China Black

* "Searchin" (CeCe Peniston song), a 1993 song by CeCe Peniston

* " Searchin' (I Gott ...

s, a

seismograph

A seismometer is an instrument that responds to ground displacement and shaking such as caused by quakes, volcanic eruptions, and explosions. They are usually combined with a timing device and a recording device to form a seismograph. The out ...

, electric

incubators for chicken eggs, and

Morse code

Morse code is a telecommunications method which Character encoding, encodes Written language, text characters as standardized sequences of two different signal durations, called ''dots'' and ''dashes'', or ''dits'' and ''dahs''. Morse code i ...

telegraph

Telegraphy is the long-distance transmission of messages where the sender uses symbolic codes, known to the recipient, rather than a physical exchange of an object bearing the message. Thus flag semaphore is a method of telegraphy, whereas ...

.

All the exhibits were from commercial enterprises. Participants included General Electric, Brush,

Western Electric

Western Electric Co., Inc. was an American electrical engineering and manufacturing company that operated from 1869 to 1996. A subsidiary of the AT&T Corporation for most of its lifespan, Western Electric was the primary manufacturer, supplier, ...

, and Westinghouse. The Westinghouse Company displayed several

polyphase system

A polyphase system (the term coined by Silvanus Thompson) is a means of distributing alternating-current (AC) electrical power that utilizes more than one AC phase, which refers to the phase offset value (in degrees) between AC in multiple co ...

s. The exhibits included a

switchboard, polyphase generators, step-up

transformer

In electrical engineering, a transformer is a passive component that transfers electrical energy from one electrical circuit to another circuit, or multiple Electrical network, circuits. A varying current in any coil of the transformer produces ...

s, transmission line, step-down transformers, commercial size

induction motor

An induction motor or asynchronous motor is an AC motor, AC electric motor in which the electric current in the rotor (electric), rotor that produces torque is obtained by electromagnetic induction from the magnetic field of the stator winding ...

s and

synchronous motor

A synchronous electric motor is an AC electric motor in which, at steady state,

the rotation of the shaft is synchronized with the frequency of the supply current; the rotation period is exactly equal to an integer number of AC cycles. Sync ...

s, and rotary direct current converters (including an operational railway motor). The working scaled system allowed the public a view of a system of polyphase power which could be transmitted over long distances, and be utilized, including the supply of direct current. Meters and other auxiliary devices were also present.

Part of the space occupied by the Westinghouse Company was devoted to demonstrations of electrical devices developed by

Nikola Tesla

Nikola Tesla (;["Tesla"](_blank)

. ''Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary''. ; 10 July 1856 – 7 ...

including

induction motor

An induction motor or asynchronous motor is an AC motor, AC electric motor in which the electric current in the rotor (electric), rotor that produces torque is obtained by electromagnetic induction from the magnetic field of the stator winding ...

s and the

generators used to power the system. The

rotating magnetic field A rotating magnetic field (RMF) is the resultant magnetic field produced by a system of Electromagnetic coil, coils symmetrically placed and supplied with Polyphase system, polyphase currents. A rotating magnetic field can be produced by a poly-phas ...

that drove these motors was explained through a series of demonstrations including an ''

Egg of Columbus'' that used the

two-phase coil in the induction motors to spin a copper egg making it stand on end.

Tesla himself showed up for a week in August to attend the

International Electrical Congress The International Electrical Congress was a series of international meetings, from 1881 to 1904, in the then new field of applied electricity. The first meeting was initiated by the French government, including official national representatives, le ...

, being held at the fair's Agriculture Hall, and put on a series of demonstrations of his wireless lighting system in a specially set up darkened room at the Westinghouse exhibit. These included demonstrations he had previously performed throughout America and Europe