Cold War (1962–1979) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Cold War (1962–1979) refers to the phase within the

The Cold War (1962–1979) refers to the phase within the

In Indonesia, the hardline anti-communist General Suharto wrested control from predecessor

In Indonesia, the hardline anti-communist General Suharto wrested control from predecessor  The Middle East remained a source of contention. Egypt, which received the bulk of its arms and economic assistance from the USSR, was a troublesome client, with a reluctant Soviet Union feeling obliged to assist in the 1967

The Middle East remained a source of contention. Egypt, which received the bulk of its arms and economic assistance from the USSR, was a troublesome client, with a reluctant Soviet Union feeling obliged to assist in the 1967  On 24 April 1974, the

On 24 April 1974, the  During the Vietnam War, North Vietnam used border areas of Cambodia as military bases, which Cambodian head of state

During the Vietnam War, North Vietnam used border areas of Cambodia as military bases, which Cambodian head of state

Officially claiming to be neutral, Finland lay in the grey zone between the Western countries and the Soviet Union. The

Officially claiming to be neutral, Finland lay in the grey zone between the Western countries and the Soviet Union. The

World Bank

North Vietnam received Soviet approval for its war effort in 1959; the Soviet Union sent 15,000 military advisors and annual arms shipments worth $450 million to North Vietnam during the war, while China sent 320,000 troops and annual arms shipments worth $180 million.

While the early years of the war had significant U.S. casualties, the administration assured the public that the war was winnable and would in the near future result in a U.S. victory. The U.S. public's faith in "the light at the end of the tunnel" was shattered on January 30, 1968, when the NLF mounted the Tet Offensive in South Vietnam. Although neither of these offensives accomplished any military objectives, the surprising capacity of an enemy to even launch such an offensive convinced many in the U.S. that victory was impossible.

A vocal and growing peace movement centered on college campuses became a prominent feature as the counterculture of the 1960s adopted a vocal anti-war position. Especially unpopular was the conscription, draft that threatened to send young men to fight in the jungles of Southeast Asia.

Elected in 1968, U.S. President Richard M. Nixon began a policy of slow disengagement from the war. The goal was to gradually build up the South Vietnamese Army so that it could fight the war on its own. This policy became the cornerstone of the so-called "Nixon Doctrine". As applied to Vietnam, the doctrine was called "Vietnamization". The goal of Vietnamization was to enable the South Vietnamese army to increasingly hold its own against the NLF and the North Vietnamese Army.

On October 10, 1969, Nixon ordered a squadron of 18 B-52 Stratofortress, B-52s loaded with nuclear weapons Operation Giant Lance, to race to the border of Soviet airspace in order to convince the

North Vietnam received Soviet approval for its war effort in 1959; the Soviet Union sent 15,000 military advisors and annual arms shipments worth $450 million to North Vietnam during the war, while China sent 320,000 troops and annual arms shipments worth $180 million.

While the early years of the war had significant U.S. casualties, the administration assured the public that the war was winnable and would in the near future result in a U.S. victory. The U.S. public's faith in "the light at the end of the tunnel" was shattered on January 30, 1968, when the NLF mounted the Tet Offensive in South Vietnam. Although neither of these offensives accomplished any military objectives, the surprising capacity of an enemy to even launch such an offensive convinced many in the U.S. that victory was impossible.

A vocal and growing peace movement centered on college campuses became a prominent feature as the counterculture of the 1960s adopted a vocal anti-war position. Especially unpopular was the conscription, draft that threatened to send young men to fight in the jungles of Southeast Asia.

Elected in 1968, U.S. President Richard M. Nixon began a policy of slow disengagement from the war. The goal was to gradually build up the South Vietnamese Army so that it could fight the war on its own. This policy became the cornerstone of the so-called "Nixon Doctrine". As applied to Vietnam, the doctrine was called "Vietnamization". The goal of Vietnamization was to enable the South Vietnamese army to increasingly hold its own against the NLF and the North Vietnamese Army.

On October 10, 1969, Nixon ordered a squadron of 18 B-52 Stratofortress, B-52s loaded with nuclear weapons Operation Giant Lance, to race to the border of Soviet airspace in order to convince the

By the last years of the Nixon administration, it had become clear that it was the Third World that remained the most volatile and dangerous source of world instability. Central to the Nixon-Henry Kissinger, Kissinger policy toward the Third World was the effort to maintain a stable status quo without involving the United States too deeply in local disputes. In 1969 and 1970, in response to the height of the Vietnam War, the President laid out the elements of what became known as the Nixon Doctrine, by which the United States would "participate in the defense and development of allies and friends" but would leave the "basic responsibility" for the future of those "friends" to the nations themselves. The Nixon Doctrine signified a growing contempt by the U.S. government for the United Nations, where underdeveloped nations were gaining influence through their sheer numbers, and increasing support to authoritarian regimes attempting to withstand popular challenges from within.

In the 1970s, for example, the Central Intelligence Agency, CIA poured substantial funds into Chile to help support the established government against a Marxist challenge. When the Marxist candidate for president,

By the last years of the Nixon administration, it had become clear that it was the Third World that remained the most volatile and dangerous source of world instability. Central to the Nixon-Henry Kissinger, Kissinger policy toward the Third World was the effort to maintain a stable status quo without involving the United States too deeply in local disputes. In 1969 and 1970, in response to the height of the Vietnam War, the President laid out the elements of what became known as the Nixon Doctrine, by which the United States would "participate in the defense and development of allies and friends" but would leave the "basic responsibility" for the future of those "friends" to the nations themselves. The Nixon Doctrine signified a growing contempt by the U.S. government for the United Nations, where underdeveloped nations were gaining influence through their sheer numbers, and increasing support to authoritarian regimes attempting to withstand popular challenges from within.

In the 1970s, for example, the Central Intelligence Agency, CIA poured substantial funds into Chile to help support the established government against a Marxist challenge. When the Marxist candidate for president,

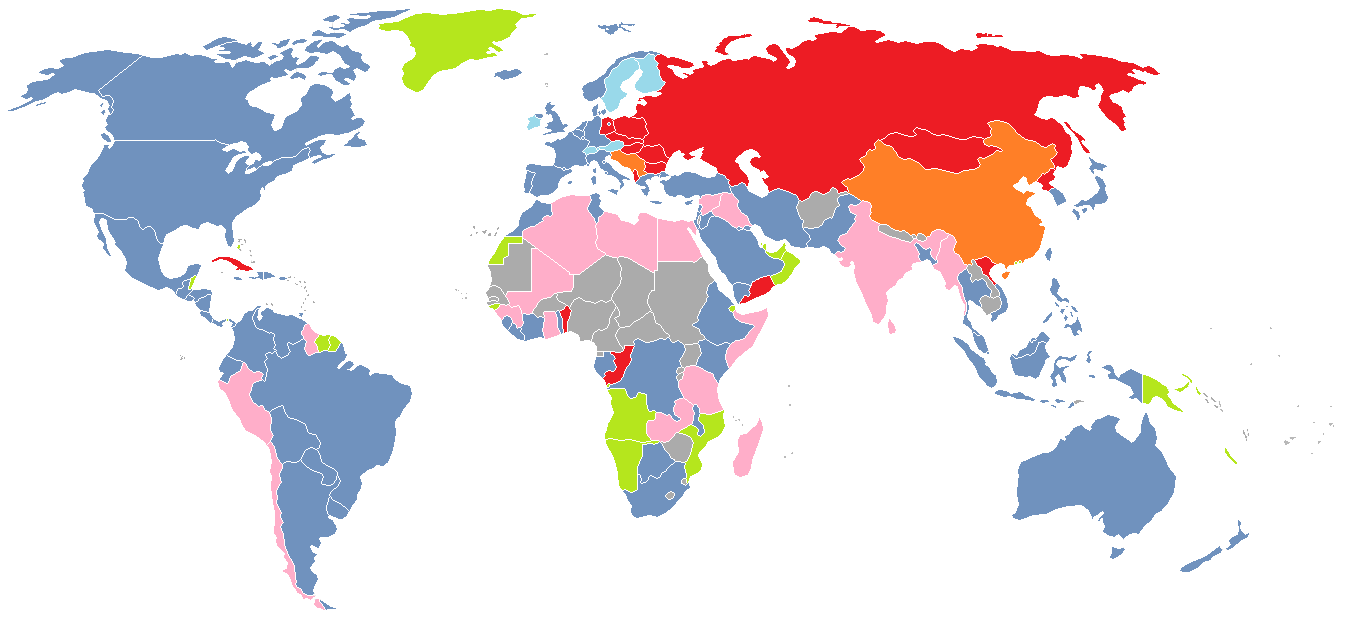

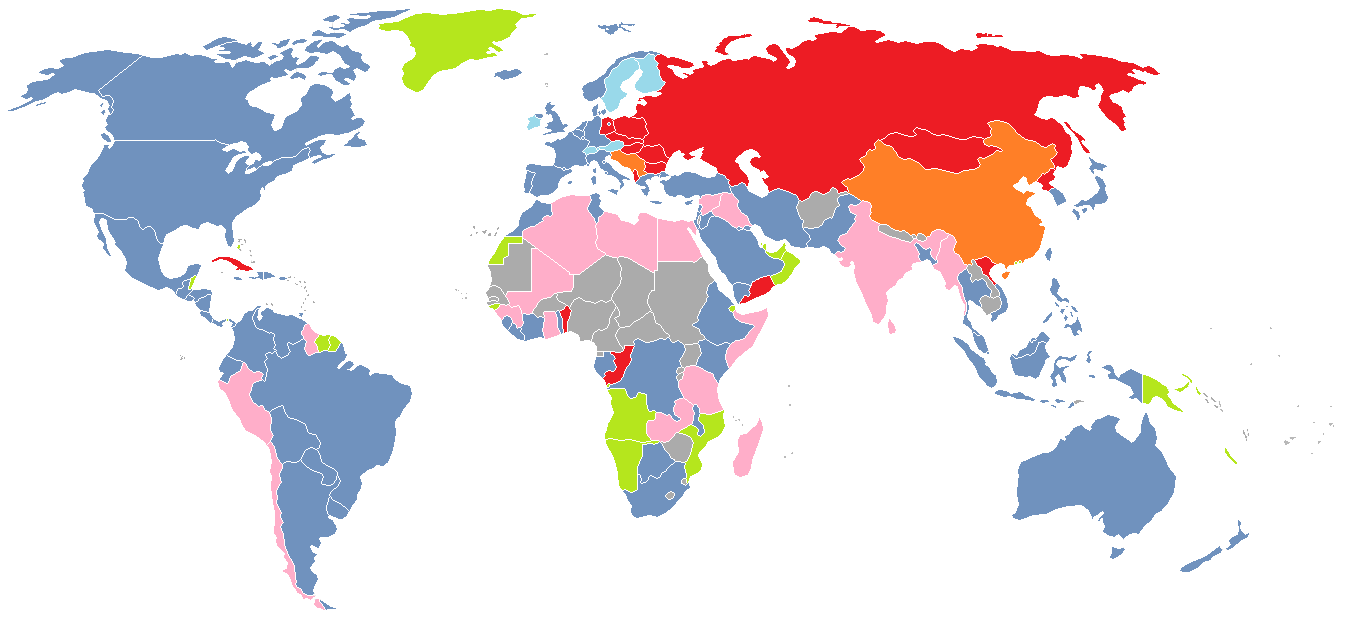

In the course of the 1960s and 1970s, Cold War participants struggled to adjust to a new, more complicated pattern of international relations in which the world was no longer divided into two clearly opposed blocs.

The Soviet Union achieved rough nuclear weapon, nuclear parity with the United States. From the beginning of the post-war period, Western Europe and Japan rapidly recovered from the destruction of World War II and sustained strong economic growth through the 1950s and 1960s, with per capita GDPs approaching those of the United States, while Eastern Bloc economies, Eastern Bloc economies stagnated. China, Japan, and Western Europe; the increasing nationalism of the Third World, and the growing disunity within the communist alliance all augured a new multipolar international structure. Moreover, the 1973 world oil shock created a dramatic shift in the economic fortunes of the superpowers. The rapid increase in the price of oil devastated the U.S. economy leading to "stagflation" and slow growth.

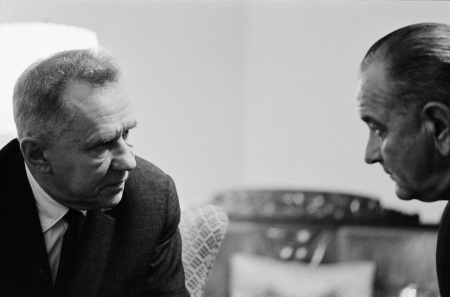

''Détente'' had both strategic and economic benefits for both sides of the Cold War, buoyed by their common interest in trying to check the further spread and proliferation of nuclear weapons. President Richard Nixon and Soviet leader

In the course of the 1960s and 1970s, Cold War participants struggled to adjust to a new, more complicated pattern of international relations in which the world was no longer divided into two clearly opposed blocs.

The Soviet Union achieved rough nuclear weapon, nuclear parity with the United States. From the beginning of the post-war period, Western Europe and Japan rapidly recovered from the destruction of World War II and sustained strong economic growth through the 1950s and 1960s, with per capita GDPs approaching those of the United States, while Eastern Bloc economies, Eastern Bloc economies stagnated. China, Japan, and Western Europe; the increasing nationalism of the Third World, and the growing disunity within the communist alliance all augured a new multipolar international structure. Moreover, the 1973 world oil shock created a dramatic shift in the economic fortunes of the superpowers. The rapid increase in the price of oil devastated the U.S. economy leading to "stagflation" and slow growth.

''Détente'' had both strategic and economic benefits for both sides of the Cold War, buoyed by their common interest in trying to check the further spread and proliferation of nuclear weapons. President Richard Nixon and Soviet leader  Cooperation on the Helsinki Accords led to several agreements on politics, economics and human rights. A series of arms control agreements such as SALT I and the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty were created to limit the development of strategic weapons and slow the arms race.

Meanwhile, the Soviet Union concluded friendship and cooperation treaties with several states in the noncommunist world, especially among Third World and Non-Aligned Movement states.

During ''Détente'', competition continued, especially in the Middle East and southern and eastern Africa. The two nations continued to compete with each other for influence in the resource-rich Third World. There was also increasing criticism of U.S. support for the Suharto regime in

Cooperation on the Helsinki Accords led to several agreements on politics, economics and human rights. A series of arms control agreements such as SALT I and the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty were created to limit the development of strategic weapons and slow the arms race.

Meanwhile, the Soviet Union concluded friendship and cooperation treaties with several states in the noncommunist world, especially among Third World and Non-Aligned Movement states.

During ''Détente'', competition continued, especially in the Middle East and southern and eastern Africa. The two nations continued to compete with each other for influence in the resource-rich Third World. There was also increasing criticism of U.S. support for the Suharto regime in

The Cold War (1962–1979) refers to the phase within the

The Cold War (1962–1979) refers to the phase within the Cold War

The Cold War was a period of global Geopolitics, geopolitical rivalry between the United States (US) and the Soviet Union (USSR) and their respective allies, the capitalist Western Bloc and communist Eastern Bloc, which lasted from 1947 unt ...

that spanned the period between the aftermath of the Cuban Missile Crisis

The Cuban Missile Crisis, also known as the October Crisis () in Cuba, or the Caribbean Crisis (), was a 13-day confrontation between the governments of the United States and the Soviet Union, when American deployments of Nuclear weapons d ...

in late October 1962, through the détente

''Détente'' ( , ; for, fr, , relaxation, paren=left, ) is the relaxation of strained relations, especially political ones, through verbal communication. The diplomacy term originates from around 1912, when France and Germany tried unsucces ...

period beginning in 1969, to the end of détente in the late 1970s.

The United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

maintained its Cold War engagement with the Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

during the period, despite internal preoccupations with the assassination of John F. Kennedy

John F. Kennedy, the 35th president of the United States, was assassinated while riding in a presidential motorcade through Dealey Plaza in Dallas, Texas, on November 22, 1963. Kennedy was in the vehicle with his wife Jacqueline Kennedy Onas ...

, the Civil Rights Movement and the opposition to United States involvement in the Vietnam War

Opposition to United States involvement in the Vietnam War began in 1965 with demonstrations against the escalating role of the United States in the Vietnam War, United States in the war. Over the next several years, these demonstrations grew ...

.

In 1968, Eastern Bloc

The Eastern Bloc, also known as the Communist Bloc (Combloc), the Socialist Bloc, the Workers Bloc, and the Soviet Bloc, was an unofficial coalition of communist states of Central and Eastern Europe, Asia, Africa, and Latin America that were a ...

member Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia ( ; Czech language, Czech and , ''Česko-Slovensko'') was a landlocked country in Central Europe, created in 1918, when it declared its independence from Austria-Hungary. In 1938, after the Munich Agreement, the Sudetenland beca ...

attempted the reforms of the Prague Spring

The Prague Spring (; ) was a period of liberalization, political liberalization and mass protest in

the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic. It began on 5 January 1968, when reformist Alexander Dubček was elected Secretary (title), First Secre ...

and was subsequently invaded by the Soviet Union and other Warsaw Pact members, who reinstated the Soviet model. By 1973, the US had withdrawn from the Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (1 November 1955 – 30 April 1975) was an armed conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia fought between North Vietnam (Democratic Republic of Vietnam) and South Vietnam (Republic of Vietnam) and their allies. North Vietnam w ...

. While communists

Communism () is a sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology within the socialist movement, whose goal is the creation of a communist society, a socioeconomic order centered on common ownership of the means of production, d ...

gained power in some South East Asia

Southeast Asia is the geographical United Nations geoscheme for Asia#South-eastern Asia, southeastern region of Asia, consisting of the regions that are situated south of China, east of the Indian subcontinent, and northwest of the Mainland Au ...

n countries, they were divided by the Sino-Soviet Split

The Sino-Soviet split was the gradual worsening of relations between the People's Republic of China (PRC) and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) during the Cold War. This was primarily caused by divergences that arose from their ...

, with China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. With population of China, a population exceeding 1.4 billion, it is the list of countries by population (United Nations), second-most populous country after ...

moving closer to the Western camp, following US President

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States. The president directs the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United States Armed For ...

Richard Nixon's visit to China. In the 1960s and 1970s, the Third World

The term Third World arose during the Cold War to define countries that remained non-aligned with either NATO or the Warsaw Pact. The United States, Canada, Taiwan, Japan, South Korea, the Southern Cone, NATO, Western European countries and oth ...

was increasingly divided between governments backed by the Soviets (such as Libya

Libya, officially the State of Libya, is a country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It borders the Mediterranean Sea to the north, Egypt to Egypt–Libya border, the east, Sudan to Libya–Sudan border, the southeast, Chad to Chad–L ...

, Iraq

Iraq, officially the Republic of Iraq, is a country in West Asia. It is bordered by Saudi Arabia to Iraq–Saudi Arabia border, the south, Turkey to Iraq–Turkey border, the north, Iran to Iran–Iraq border, the east, the Persian Gulf and ...

, Syria

Syria, officially the Syrian Arab Republic, is a country in West Asia located in the Eastern Mediterranean and the Levant. It borders the Mediterranean Sea to the west, Turkey to Syria–Turkey border, the north, Iraq to Iraq–Syria border, t ...

, Egypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

and South Yemen

South Yemen, officially the People's Democratic Republic of Yemen, abbreviated to Democratic Yemen, was a country in South Arabia that existed in what is now southeast Yemen from 1967 until Yemeni unification, its unification with the Yemen A ...

), governments backed by NATO

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO ; , OTAN), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental organization, intergovernmental Transnationalism, transnational military alliance of 32 Member states of NATO, member s ...

(such as Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia, officially the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA), is a country in West Asia. Located in the centre of the Middle East, it covers the bulk of the Arabian Peninsula and has a land area of about , making it the List of Asian countries ...

), and a growing camp of non-aligned nations.

Third World and non-alignment in the 1960s and 1970s

Decolonization

Cold War politics were affected by decolonization in Africa, Asia, and to a limited extent, Latin America as well. The economic needs of emergingThird World

The term Third World arose during the Cold War to define countries that remained non-aligned with either NATO or the Warsaw Pact. The United States, Canada, Taiwan, Japan, South Korea, the Southern Cone, NATO, Western European countries and oth ...

states made them vulnerable to foreign influence and pressure. The era was characterized by a proliferation of anti-colonial national liberation movements, backed predominantly by the Soviet Union and the People's Republic of China. The Soviet leadership took a keen interest in the affairs of the fledgling ex-colonies because it hoped the cultivation of socialist clients there would deny their economic and strategic resources to the West. Eager to build its own global constituency, the People's Republic of China attempted to assume a leadership role among the decolonizing territories as well, appealing to its image as a non-white, non-European agrarian nation which too had suffered from the depredations of Western imperialism. Both nations promoted global decolonization as an opportunity to redress the balance of the world against Western Europe and the United States, and claimed that the political and economic problems of colonized peoples made them naturally inclined towards socialism.

Western fears of a conventional war with the communist bloc over the colonies soon shifted into fears of communist subversion and infiltration by proxy. The great disparities of wealth in many of the colonies between the colonized indigenous population and the colonizers provided fertile ground for the adoption of socialist ideology among many anti-colonial parties. This provided ammunition for Western propaganda which denounced many anti-colonial movements as being communist proxies.

As pressure for decolonization mounted, the departing colonial regimes attempted to transfer power to moderate and stable local governments committed to continued economic and political ties with the West. Political transitions were not always peaceful; for example, violence broke out in Anglophone Southern Cameroons

The Southern Cameroons was the southern part of the British League of Nations mandate territory of the British Cameroons in West Africa. Since 1961, it has been part of the Republic of Cameroon, where it makes up the Northwest Region and Southw ...

due to an unpopular union with Francophone Cameroon

Cameroon, officially the Republic of Cameroon, is a country in Central Africa. It shares boundaries with Nigeria to the west and north, Chad to the northeast, the Central African Republic to the east, and Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, and the R ...

following independence from those respective nations. The Congo Crisis

The Congo Crisis () was a period of Crisis, political upheaval and war, conflict between 1960 and 1965 in the Republic of the Congo (Léopoldville), Republic of the Congo (today the Democratic Republic of the Congo). The crisis began almost ...

broke out with the dissolution of the Belgian Congo

The Belgian Congo (, ; ) was a Belgian colonial empire, Belgian colony in Central Africa from 1908 until independence in 1960 and became the Republic of the Congo (Léopoldville). The former colony adopted its present name, the Democratic Repu ...

, after the new Congolese army mutinied against its Belgian officers, resulting in an exodus of the European population and plunging the territory into a civil war which raged throughout the mid-1960s. Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic, is a country on the Iberian Peninsula in Southwestern Europe. Featuring Cabo da Roca, the westernmost point in continental Europe, Portugal borders Spain to its north and east, with which it share ...

attempted to actively resist decolonization and was forced to contend with nationalist insurgencies in all of its African colonies until 1975. The presence of significant numbers of white settlers in Rhodesia

Rhodesia ( , ; ), officially the Republic of Rhodesia from 1970, was an unrecognised state, unrecognised state in Southern Africa that existed from 1965 to 1979. Rhodesia served as the ''de facto'' Succession of states, successor state to the ...

complicated attempts at decolonization there, and the former actually issued a unilateral declaration of independence

A unilateral declaration of independence (UDI) or "unilateral secession" is a formal process leading to the establishment of a new state by a subnational entity which declares itself independent and sovereign without a formal agreement with the ...

in 1965 to preempt an immediate transition to majority rule. The breakaway white government retained power in Rhodesia until 1979, despite a United Nations embargo and a devastating civil war

A civil war is a war between organized groups within the same Sovereign state, state (or country). The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies.J ...

with two rival guerrilla factions backed by the Soviets and Chinese, respectively.

Alliances

Somedeveloping countries

A developing country is a sovereign state with a less-developed Secondary sector of the economy, industrial base and a lower Human Development Index (HDI) relative to developed countries. However, this definition is not universally agreed upon. ...

devised a strategy that turned the Cold War into what they called "creative confrontation" – playing off the Cold War participants to their own advantage while maintaining non-aligned status. The diplomatic policy of non-alignment regarded the Cold War as a tragic and frustrating facet of international affairs, obstructing the overriding task of consolidating fledgling states

State most commonly refers to:

* State (polity), a centralized political organization that regulates law and society within a territory

**Sovereign state, a sovereign polity in international law, commonly referred to as a country

**Nation state, a ...

and their attempts to end economic backwardness, poverty, and disease. Non-alignment held that peaceful coexistence with the first-world and second-world nations was both preferable and possible. India

India, officially the Republic of India, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area; the List of countries by population (United Nations), most populous country since ...

's Jawaharlal Nehru

Jawaharlal Nehru (14 November 1889 – 27 May 1964) was an Indian anti-colonial nationalist, secular humanist, social democrat, and statesman who was a central figure in India during the middle of the 20th century. Nehru was a pr ...

saw neutralism as a means of forging a "third force" among non-aligned nations, much as France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

's Charles de Gaulle

Charles André Joseph Marie de Gaulle (22 November 18909 November 1970) was a French general and statesman who led the Free France, Free French Forces against Nazi Germany in World War II and chaired the Provisional Government of the French Re ...

attempted to do in Europe in the 1960s. The Egypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

ian leader Gamal Abdel Nasser

Gamal Abdel Nasser Hussein (15 January 1918 – 28 September 1970) was an Egyptian military officer and revolutionary who served as the second president of Egypt from 1954 until his death in 1970. Nasser led the Egyptian revolution of 1952 a ...

manoeuvres between the blocs in pursuit of his goals was one example of this.

The first such effort, the Asian Relations Conference

The Asian Relations Conference was an international conference that took place in New Delhi from 23 March to 2 April, 1947. Organized by the Indian Council of World Affairs (ICWA), the Conference was hosted by Jawaharlal Nehru, then the Vice-P ...

, held in New Delhi

New Delhi (; ) is the Capital city, capital of India and a part of the Delhi, National Capital Territory of Delhi (NCT). New Delhi is the seat of all three branches of the Government of India, hosting the Rashtrapati Bhavan, New Parliament ...

in 1947, pledged support for all national movements against colonial rule and explored the basic problems of Asian peoples. Perhaps the most famous Third World

The term Third World arose during the Cold War to define countries that remained non-aligned with either NATO or the Warsaw Pact. The United States, Canada, Taiwan, Japan, South Korea, the Southern Cone, NATO, Western European countries and oth ...

conclave was the Bandung Conference

The first large-scale Asian–African or Afro–Asian Conference (), also known as the Bandung Conference, was a meeting of Asian and African states, most of which were newly independent, which took place on 18–24 April 1955 in Bandung, We ...

of African and Asian nations in 1955 to discuss mutual interests and strategy, which ultimately led to the establishment of the Non-Aligned Movement

The Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) is a forum of 121 countries that Non-belligerent, are not formally aligned with or against any major power bloc. It was founded with the view to advancing interests of developing countries in the context of Cold W ...

in 1961. The conference was attended by twenty-nine countries representing more than half the population of the world. As at New Delhi, anti-imperialism

Anti-imperialism in political science and international relations is opposition to imperialism or neocolonialism. Anti-imperialist sentiment typically manifests as a political principle in independence struggles against intervention or influen ...

, economic development, and cultural cooperation were the principal topics. There was a strong push in the Third World to secure a voice in the councils of nations, especially the United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is the Earth, global intergovernmental organization established by the signing of the Charter of the United Nations, UN Charter on 26 June 1945 with the stated purpose of maintaining international peace and internationa ...

, and to receive recognition of their new sovereign status. Representatives of these new states were also extremely sensitive to slights and discriminations, particularly if they were based on race. In all the nations of the Third World, living standard

Standard of living is the level of income, comforts and services available to an individual, community or society. A contributing factor to an individual's quality of life, standard of living is generally concerned with objective metrics outside ...

s were wretchedly low. Some, such as India, Nigeria

Nigeria, officially the Federal Republic of Nigeria, is a country in West Africa. It is situated between the Sahel to the north and the Gulf of Guinea in the Atlantic Ocean to the south. It covers an area of . With Demographics of Nigeria, ...

, and Indonesia

Indonesia, officially the Republic of Indonesia, is a country in Southeast Asia and Oceania, between the Indian Ocean, Indian and Pacific Ocean, Pacific oceans. Comprising over List of islands of Indonesia, 17,000 islands, including Sumatra, ...

, were becoming regional powers, most were too small and poor to aspire to this status.

Initially having a roster of 51 members, the UN General Assembly

The United Nations General Assembly (UNGA or GA; , AGNU or AG) is one of the six principal organs of the United Nations (UN), serving as its main deliberative, policymaking, and representative organ. Currently in its 79th session, its powers, ...

had increased to 126 by 1970. The dominance of Western members dropped to 40% of the membership, with Afro-Asian states holding the balance of power. The ranks of the General Assembly swelled rapidly as former colonies won independence, thus forming a substantial voting bloc with members from Latin America

Latin America is the cultural region of the Americas where Romance languages are predominantly spoken, primarily Spanish language, Spanish and Portuguese language, Portuguese. Latin America is defined according to cultural identity, not geogr ...

. Anti-imperialist

Imperialism is the maintaining and extending of power over foreign nations, particularly through expansionism, employing both hard power (military and economic power) and soft power ( diplomatic power and cultural imperialism). Imperialism fo ...

sentiment, reinforced by the communists, often translated into anti-Western positions, but the primary agenda among non-aligned countries was to secure passage of social and economic assistance measures. Superpower refusal to fund such programs has often undermined the effectiveness of the non-aligned coalition, however. The Bandung Conference symbolized continuing efforts to establish regional organizations designed to forge unity of policy and economic cooperation among Third World nations. The Organization of African Unity

The Organisation of African Unity (OAU; , OUA) was an African intergovernmental organization established on 25 May 1963 in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, with 33 signatory governments. Some of the key aims of the OAU were to encourage political and ec ...

(OAU) was created in Addis Ababa

Addis Ababa (; ,) is the capital city of Ethiopia, as well as the regional state of Oromia. With an estimated population of 2,739,551 inhabitants as of the 2007 census, it is the largest city in the country and the List of cities in Africa b ...

, Ethiopia

Ethiopia, officially the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, is a landlocked country located in the Horn of Africa region of East Africa. It shares borders with Eritrea to the north, Djibouti to the northeast, Somalia to the east, Ken ...

, in 1963 because African leaders believed that disunity played into the hands of the superpowers. The OAU was designed

:''to promote the unity and solidarity of the African states; to coordinate and intensify the cooperation and efforts to achieve a better life for the peoples of Africa; to defend their sovereignty; to eradicate all forms of colonialism in Africa and to promote international cooperation...''

The OAU required a policy of non-alignment from each of its 30 member states and spawned several subregional economic groups similar in concept to the European Common Market. The OAU has also pursued a policy of political cooperation with other Third World regional coalitions, especially with Arab

Arabs (, , ; , , ) are an ethnic group mainly inhabiting the Arab world in West Asia and North Africa. A significant Arab diaspora is present in various parts of the world.

Arabs have been in the Fertile Crescent for thousands of years ...

countries.

Much of the frustration expressed by non-aligned nations stemmed from the vastly unequal relationship between rich and poor states. The resentment, strongest where key resources and local economies have been exploited by multinational Western corporations, has had a major impact on world events. The formation of the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries

The Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC ) is an organization enabling the co-operation of leading oil-producing and oil-dependent countries in order to collectively influence the global oil market and maximize Profit (eco ...

(OPEC) in 1960 reflected these concerns. OPEC devised a strategy of counter-penetration, whereby it hoped to make industrial economies that relied heavily on oil imports vulnerable to Third World pressures. Initially, the strategy had resounding success. Dwindling foreign aid from the United States and its allies, coupled with the West's pro-Israel

Israel, officially the State of Israel, is a country in West Asia. It Borders of Israel, shares borders with Lebanon to the north, Syria to the north-east, Jordan to the east, Egypt to the south-west, and the Mediterranean Sea to the west. Isr ...

policies, angered the Arab nations in OPEC. In 1973, the group quadrupled the price of crude oil. The sudden rise in the energy costs intensified inflation and recession in the West and underscored the interdependence of world societies. The next year the non-aligned bloc in the United Nations passed a resolution demanding the creation of a new international economic order

The New International Economic Order (NIEO) is a set of proposals advocated by developing countries to end economic colonialism and dependency through a new interdependent economy. The main NIEO document recognized that the current international e ...

in which resources, trade, and markets would be distributed fairly.

Non-aligned states forged still other forms of economic cooperation as leverage against the superpowers. OPEC, the OAU, and the Arab League

The Arab League (, ' ), officially the League of Arab States (, '), is a regional organization in the Arab world. The Arab League was formed in Cairo on 22 March 1945, initially with seven members: Kingdom of Egypt, Egypt, Kingdom of Iraq, ...

had overlapping members, and in the 1970s the Arabs began extending huge financial assistance to African nations in an effort to reduce African economic dependence on the United States and the Soviet Union. However, the Arab League has been torn by dissension between authoritarian pro-Soviet states, such as Nasser's Egypt and Assad's Syria

Syria, officially the Syrian Arab Republic, is a country in West Asia located in the Eastern Mediterranean and the Levant. It borders the Mediterranean Sea to the west, Turkey to Syria–Turkey border, the north, Iraq to Iraq–Syria border, t ...

, and the aristocratic-monarchial (and generally pro-Western) regimes, such as Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia, officially the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA), is a country in West Asia. Located in the centre of the Middle East, it covers the bulk of the Arabian Peninsula and has a land area of about , making it the List of Asian countries ...

and Oman

Oman, officially the Sultanate of Oman, is a country located on the southeastern coast of the Arabian Peninsula in West Asia and the Middle East. It shares land borders with Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and Yemen. Oman’s coastline ...

. And while the OAU has witnessed some gains in African cooperation, its members were generally primarily interested in pursuing their own national interests rather than those of continental dimensions. At a 1977 Afro-Arab summit conference in Cairo

Cairo ( ; , ) is the Capital city, capital and largest city of Egypt and the Cairo Governorate, being home to more than 10 million people. It is also part of the List of urban agglomerations in Africa, largest urban agglomeration in Africa, L ...

, oil producers pledged $1.5 billion in aid to Africa. Recent divisions within OPEC have made concerted action more difficult. Nevertheless, the 1973 world oil shock provided dramatic evidence of the potential power of resource suppliers in dealing with the more developed world

A developed country, or advanced country, is a sovereign state that has a high quality of life, developed economy, and advanced technological infrastructure relative to other less industrialized nations. Most commonly, the criteria for eval ...

.

Escalations

Under theLyndon B. Johnson

Lyndon Baines Johnson (; August 27, 1908January 22, 1973), also known as LBJ, was the 36th president of the United States, serving from 1963 to 1969. He became president after the assassination of John F. Kennedy, under whom he had served a ...

administration

Administration may refer to:

Management of organizations

* Management, the act of directing people towards accomplishing a goal: the process of dealing with or controlling things or people.

** Administrative assistant, traditionally known as a se ...

, the US took a more hardline stance on Latin America—sometimes called the " Mann Doctrine". In 1964, the Brazilian military overthrew the government of João Goulart

João Belchior Marques Goulart (; 1 March 1919 – 6 December 1976), commonly known as Jango, was a Brazilian politician who served as the president of Brazil from 1961 until a military coup d'état deposed him in 1964. He was considered the ...

with US backing. In April 1965, the US sent 22,000 troops to the Dominican Republic

The Dominican Republic is a country located on the island of Hispaniola in the Greater Antilles of the Caribbean Sea in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean. It shares a Maritime boundary, maritime border with Puerto Rico to the east and ...

in an intervention, into the Dominican Civil War between supporters of deposed president Juan Bosch and supporters of General Elías Wessin y Wessin, citing the threat of the emergence of a Cuban-style revolution in Latin America. The OAS deployed soldiers through the mostly Brazilian Inter-American Peace Force. Héctor García-Godoy acted as provisional president, until conservative former president Joaquín Balaguer won the 1966 presidential election against non-campaigning Juan Bosch. Activists for Bosch's Dominican Revolutionary Party were violently harassed by the Dominican police and armed forces.

In Indonesia, the hardline anti-communist General Suharto wrested control from predecessor

In Indonesia, the hardline anti-communist General Suharto wrested control from predecessor Sukarno

Sukarno (6 June 1901 – 21 June 1970) was an Indonesian statesman, orator, revolutionary, and nationalist who was the first president of Indonesia, serving from 1945 to 1967.

Sukarno was the leader of the Indonesian struggle for independenc ...

in an attempt to establish a "New Order". From 1965 to 1966, with the aid of the US and other Western governments, the military led the mass killing of more than 500,000 members and sympathizers of the Indonesian Communist Party and other leftist organizations, and detained hundreds of thousands in prison camps under inhumane conditions. A top-secret CIA report stated that the massacres "rank as one of the worst mass murder

Mass murder is the violent crime of murder, killing a number of people, typically simultaneously or over a relatively short period of time and in close geographic proximity. A mass murder typically occurs in a single location where one or more ...

s of the 20th century, along with the Soviet purges of the 1930s, the Nazi mass murders during the Second World War, and the Maoist bloodbath of the early 1950s." These killings served US interests and constitute a major turning point in the Cold War as the balance of power shifted in Southeast Asia.

Escalating the scale of American intervention in the conflict between Ngô Đình Diệm

Ngô Đình Diệm ( , or ; ; 3 January 1901 – 2 November 1963) was a South Vietnamese politician who was the final prime minister of the State of Vietnam (1954–1955) and later the first president of South Vietnam ( Republic of ...

's South Vietnam

South Vietnam, officially the Republic of Vietnam (RVN; , VNCH), was a country in Southeast Asia that existed from 1955 to 1975. It first garnered Diplomatic recognition, international recognition in 1949 as the State of Vietnam within the ...

ese government and the communist National Front for the Liberation of South Vietnam

The Viet Cong (VC) was an epithet and umbrella term to refer to the communist-driven armed movement and united front organization in South Vietnam. It was formally organized as and led by the National Liberation Front of South Vietnam, and ...

(NLF) insurgents opposing it, Johnson deployed 575,000 troops in Southeast Asia to defeat the NLF and their North Vietnamese allies in the Vietnam War, but his costly policy weakened the US economy and sparked domestic anti-war protests, which led to the US withdrawal by 1972. Without American support, South Vietnam was conquered by North Vietnam in 1975; the US reputation suffered as the world saw the defeat of a superpower at the hands of one of the poorest nations.

The Middle East remained a source of contention. Egypt, which received the bulk of its arms and economic assistance from the USSR, was a troublesome client, with a reluctant Soviet Union feeling obliged to assist in the 1967

The Middle East remained a source of contention. Egypt, which received the bulk of its arms and economic assistance from the USSR, was a troublesome client, with a reluctant Soviet Union feeling obliged to assist in the 1967 Six-Day War

The Six-Day War, also known as the June War, 1967 Arab–Israeli War or Third Arab–Israeli War, was fought between Israel and a coalition of Arab world, Arab states, primarily United Arab Republic, Egypt, Syria, and Jordan from 5 to 10June ...

and the War of Attrition

The War of Attrition (; ) involved fighting between Israel and Egypt, Jordan, the Palestine Liberation Organisation (PLO) and their allies from 1967 to 1970.

Following the 1967 Six-Day War, no serious diplomatic efforts were made to resolve t ...

against pro-Western Israel

Israel, officially the State of Israel, is a country in West Asia. It Borders of Israel, shares borders with Lebanon to the north, Syria to the north-east, Jordan to the east, Egypt to the south-west, and the Mediterranean Sea to the west. Isr ...

. Despite the beginning of an Egyptian shift from a pro-Soviet to a pro-American orientation in 1972, the Soviets supported Egypt and Syria

Syria, officially the Syrian Arab Republic, is a country in West Asia located in the Eastern Mediterranean and the Levant. It borders the Mediterranean Sea to the west, Turkey to Syria–Turkey border, the north, Iraq to Iraq–Syria border, t ...

during the Yom Kippur War

The Yom Kippur War, also known as the Ramadan War, the October War, the 1973 Arab–Israeli War, or the Fourth Arab–Israeli War, was fought from 6 to 25 October 1973 between Israel and a coalition of Arab world, Arab states led by Egypt and S ...

, as the US supported Israel. Although pre-Sadat Egypt had been the largest recipient of Soviet aid in the Middle East, the Soviets were successful in establishing close relations with communist South Yemen

South Yemen, officially the People's Democratic Republic of Yemen, abbreviated to Democratic Yemen, was a country in South Arabia that existed in what is now southeast Yemen from 1967 until Yemeni unification, its unification with the Yemen A ...

, as well as the nationalist governments of Algeria

Algeria, officially the People's Democratic Republic of Algeria, is a country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It is bordered to Algeria–Tunisia border, the northeast by Tunisia; to Algeria–Libya border, the east by Libya; to Alger ...

and Iraq

Iraq, officially the Republic of Iraq, is a country in West Asia. It is bordered by Saudi Arabia to Iraq–Saudi Arabia border, the south, Turkey to Iraq–Turkey border, the north, Iran to Iran–Iraq border, the east, the Persian Gulf and ...

. Iraq signed a 15-year Treaty of Friendship and Cooperation with the Soviet Union in 1972. According to Charles R. H. Tripp, the treaty upset "the US-sponsored security system established as part of the Arab Cold War

The Arab Cold War ( ''al-ḥarb al-`arabiyyah al-bāridah'') was a political rivalry in the Arab world from the early 1950s to the late 1970s and a part of the wider Cold War. It is generally accepted that the beginning of the Arab Cold War is ...

. It appeared that any enemy of the Baghdad regime was a potential ally of the United States." In response, the US covertly financed Kurdish rebels during the Second Iraqi–Kurdish War; the Kurds were defeated in 1975, leading to the forcible relocation of hundreds of thousands of Kurdish civilians. Indirect Soviet assistance to the Palestinian side of the Israeli–Palestinian conflict

The Israeli–Palestinian conflict is an ongoing military and political conflict about Territory, land and self-determination within the territory of the former Mandatory Palestine. Key aspects of the conflict include the Israeli occupation ...

included support for Yasser Arafat

Yasser Arafat (4 or 24 August 1929 – 11 November 2004), also popularly known by his Kunya (Arabic), kunya Abu Ammar, was a Palestinian political leader. He was chairman of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) from 1969 to 2004, Presid ...

's Palestine Liberation Organization

The Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO; ) is a Palestinian nationalism, Palestinian nationalist coalition that is internationally recognized as the official representative of the Palestinians, Palestinian people in both the occupied Pale ...

(PLO).

In East Africa, a territorial dispute between Somalia

Somalia, officially the Federal Republic of Somalia, is the easternmost country in continental Africa. The country is located in the Horn of Africa and is bordered by Ethiopia to the west, Djibouti to the northwest, Kenya to the southwest, th ...

and Ethiopia

Ethiopia, officially the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, is a landlocked country located in the Horn of Africa region of East Africa. It shares borders with Eritrea to the north, Djibouti to the northeast, Somalia to the east, Ken ...

over the Ogaden

Ogaden (pronounced and often spelled ''Ogadēn''; , ) is one of the historical names used for the modern Somali Region. It is also natively referred to as Soomaali Galbeed (). The region forms the eastern portion of Ethiopia and borders Somalia ...

region resulted in the Ogaden War

The Ogaden War, also known as the Ethio-Somali War (, ), was a military conflict between Somali Democratic Republic, Somalia and derg, Ethiopia fought from July 1977 to March 1978 over control of the sovereignty of the Ogaden region. Somalia ...

. Around June 1977, Somali troops occupied the Ogaden and began advancing inland towards Ethiopian positions in the Ahmar Mountains. Both countries were client states of the Soviet Union; Somalia was led by Marxist military leader Siad Barre

Mohammed Siad Barre (, Osmanya script: , ''Muhammad Ziād Barīy''; 6 October 1919 – 2 January 1995) was a Somali military officer, politician, and revolutionary who served as the third president of Somalia from 21 October 1969 to 26 Janu ...

, and Ethiopia was controlled by the Derg

The Derg or Dergue (, ), officially the Provisional Military Administrative Council (PMAC), was the military junta that ruled Ethiopia, including present-day Eritrea, from 1974 to 1987, when they formally "Civil government, civilianized" the ...

, a cabal of generals loyal to the pro-Soviet Mengistu Haile Mariam

Mengistu Haile Mariam (, pronunciation: ; born 21 May 1937) is an Ethiopian former politician, revolutionary, and military officer who served as the head of state of Ethiopia from 1977 to 1991. He was General Secretary of the Workers' Party o ...

, who had declared the Provisional Military Government of Socialist Ethiopia in 1975. The Soviets initially attempted to exert a moderating influence on both states, but in November 1977 Barre broke off relations with Moscow and expelled his Soviet military advisers. He turned to China and the Safari Club

The Safari Club was a covert alliance of intelligence services formed in 1976 that ran clandestine operations around Africa at a time when the United States Congress had limited the power of the CIA after years of abuses and when Portugal was d ...

—a group of pro-American intelligence agencies including those of Iran, Egypt, Saudi Arabia—for support. While declining to take a direct part in hostilities, the Soviet Union did provide the impetus for a successful Ethiopian counteroffensive to expel Somalia from the Ogaden. The counteroffensive was planned at the command level by Soviet advisers and bolstered by the delivery of millions of dollars' of sophisticated Soviet arms. About 11,000 Cuban troops spearheaded the primary effort, after receiving hasty training on the newly delivered Soviet weapons systems by East German instructors.

In Chile

Chile, officially the Republic of Chile, is a country in western South America. It is the southernmost country in the world and the closest to Antarctica, stretching along a narrow strip of land between the Andes, Andes Mountains and the Paci ...

, the Socialist Party

Socialist Party is the name of many different political parties around the world. All of these parties claim to uphold some form of socialism, though they may have very different interpretations of what "socialism" means. Statistically, most of th ...

candidate Salvador Allende

Salvador Guillermo Allende Gossens (26 June 1908 – 11 September 1973) was a Chilean socialist politician who served as the 28th president of Chile from 1970 until Death of Salvador Allende, his death in 1973 Chilean coup d'état, 1973. As a ...

won the presidential election of 1970, thereby becoming the first democratically elected Marxist to become president of a country in the Americas. The CIA targeted Allende for removal and operated to undermine his support domestically, which contributed to unrest culminating in General Augusto Pinochet

Augusto José Ramón Pinochet Ugarte (25 November 1915 – 10 December 2006) was a Chilean military officer and politician who was the dictator of Military dictatorship of Chile, Chile from 1973 to 1990. From 1973 to 1981, he was the leader ...

's 1973 Chilean coup d'état

The 1973 Chilean coup d'état () was a military overthrow of the democratic socialist president of Chile Salvador Allende and his Popular Unity (Chile), Popular Unity coalition government. Allende, who has been described as the first Marxist ...

. Pinochet consolidated power as a military dictator, Allende's reforms of the economy were rolled back, and leftist opponents were killed or detained in internment camps under the Dirección de Inteligencia Nacional

The Dirección de Inteligencia Nacional (DINA; ) was the secret police of Chile during the dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet. The DINA has been referred to as "Pinochet's Gestapo". Established in November 1973 as a Chilean Army intelligence unit ...

(DINA). Socialist states—with the exception of China and Romania

Romania is a country located at the crossroads of Central Europe, Central, Eastern Europe, Eastern and Southeast Europe. It borders Ukraine to the north and east, Hungary to the west, Serbia to the southwest, Bulgaria to the south, Moldova to ...

—broke off relations with Chile. The Pinochet regime would go on to be one of the leading participants in Operation Condor

Operation Condor (; ) was a campaign of political repression by the right-wing dictatorships of the Southern Cone of South America, involving intelligence operations, coups, and assassinations of left-wing sympathizers in South America which fo ...

, an international campaign of assassination and state terrorism

State terrorism is terrorism conducted by a state against its own citizens or another state's citizens.

It contrasts with '' state-sponsored terrorism'', in which a violent non-state actor conducts an act of terror under sponsorship of a state. ...

organized by right-wing military dictatorships in the Southern Cone

The Southern Cone (, ) is a geographical and cultural subregion composed of the southernmost areas of South America, mostly south of the Tropic of Capricorn. Traditionally, it covers Argentina, Chile, and Uruguay, bounded on the west by the Pac ...

of South America that was covertly supported by the US government.

Carnation Revolution

The Carnation Revolution (), code-named Operation Historic Turn (), also known as the 25 April (), was a military coup by military officers that overthrew the Estado Novo government on 25 April 1974 in Portugal. The coup produced major socia ...

succeeded in ousting Marcelo Caetano

Marcello José das Neves Alves Caetano (17 August 1906 – 26 October 1980) was a Portuguese politician and scholar. He was the second and last leader of the Estado Novo after succeeding António de Oliveira Salazar. He served as prime mini ...

and Portugal's right-wing '' Estado Novo'' government, sounding the death knell for the Portuguese Empire.

Independence was hastily granted to several Portuguese colonies, including Angola

Angola, officially the Republic of Angola, is a country on the west-Central Africa, central coast of Southern Africa. It is the second-largest Portuguese-speaking world, Portuguese-speaking (Lusophone) country in both total area and List of c ...

, where the disintegration of colonial rule was followed by a civil war.

There were three rival militant factions competing for power in Angola: the People's Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA), the National Union for the Total Independence of Angola

The National Union for the Total Independence of Angola (, abbr. UNITA) is the second-largest political party in Angola. Founded in 1966, UNITA fought alongside the People's Movement for the Liberation of Angola ( MPLA) and the National Lib ...

(UNITA), and the National Liberation Front of Angola

The National Front for the Liberation of Angola (; abbreviated FNLA) is a political party and former militant organisation that fought for Angolan independence from Portugal in the war of independence, under the leadership of Holden Roberto.

F ...

(FNLA).

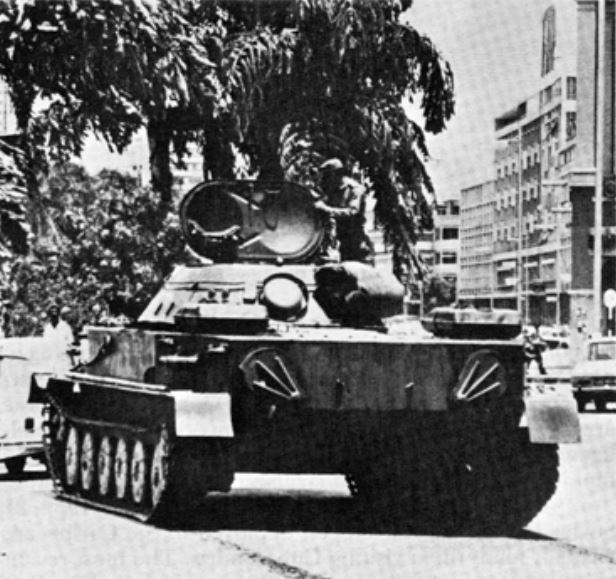

While all three had socialist leanings, the MPLA was the only party with close ties to the Soviet Union. Its adherence to the concept of a Soviet one-party state alienated it from the FNLA and UNITA, which began portraying themselves as anti-communist and pro-Western. When the Soviets began supplying the MPLA with arms, the CIA and China offered substantial covert aid to the FNLA and UNITA. The MPLA eventually requested direct military support from Moscow in the form of ground troops, but the Soviets declined, offering to send advisers but no combat personnel. Cuba was more forthcoming and began amassing troops in Angola to assist the MPLA. By November 1975, there were over a thousand Cuban soldiers in the country. The persistent buildup of Cuban troops and Soviet weapons allowed the MPLA to secure victory and blunt an abortive intervention by Zairean and South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the Southern Africa, southernmost country in Africa. Its Provinces of South Africa, nine provinces are bounded to the south by of coastline that stretches along the Atlantic O ...

n troops, which had deployed in a belated attempt to assist the FNLA and UNITA.

During the Vietnam War, North Vietnam used border areas of Cambodia as military bases, which Cambodian head of state

During the Vietnam War, North Vietnam used border areas of Cambodia as military bases, which Cambodian head of state Norodom Sihanouk

Norodom Sihanouk (; 31 October 192215 October 2012) was a member of the House of Norodom, Cambodian royal house who led the country as Monarchy of Cambodia, King, List of heads of state of Cambodia, Chief of State and Prime Minister of Cambodi ...

tolerated in an attempt to preserve Cambodia's neutrality. Following Sihanouk's March 1970 deposition by pro-American general Lon Nol

Marshal Lon Nol (, also ; 13 November 1913 – 17 November 1985) was a Cambodian military officer and politician who served as Prime Minister of Cambodia twice (1966–67; 1969–71), as well as serving repeatedly as defence minister and provi ...

, who ordered the North Vietnamese to leave Cambodia, North Vietnam attempted to overrun Cambodia following negotiations with Nuon Chea

Nuon Chea (; born Lao Kim Lorn; 7 July 1926 – 4 August 2019), also known as Long Bunruot () or Rungloet Laodi ( ), was a Cambodian communism, communist politician and revolutionary who was the chief ideologist of the Khmer Rouge. He also briefl ...

, the second-in-command of the Cambodian communists (dubbed the Khmer Rouge

The Khmer Rouge is the name that was popularly given to members of the Communist Party of Kampuchea (CPK), and by extension to Democratic Kampuchea, which ruled Cambodia between 1975 and 1979. The name was coined in the 1960s by Norodom Sihano ...

) fighting to overthrow the Cambodian government. Sihanouk fled to China with the establishment of the GRUNK

The Royal Government of National Union of Kampuchea (, GRUNK; ) was a government-in-exile of Cambodia, based in Beijing and Hong Kong, that was in existence between 1970 and 1976, and was briefly in control of the country starting from 1975.

Th ...

in Beijing. American and South Vietnamese forces responded to these actions with a bombing campaign and a ground incursion, which contributed to the violence of the civil war

A civil war is a war between organized groups within the same Sovereign state, state (or country). The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies.J ...

that soon enveloped all of Cambodia. US carpet bombing lasted until 1973, and while it prevented the Khmer Rouge from seizing the capital, it accelerated the collapse of rural society, increased social polarization, and killed tens of thousands.

After taking power and distancing himself from the Vietnamese, pro-China Khmer Rouge leader Pol Pot

Pol Pot (born Saloth Sâr; 19 May 1925 – 15 April 1998) was a Cambodian politician, revolutionary, and dictator who ruled the communist state of Democratic Kampuchea from 1976 until Cambodian–Vietnamese War, his overthrow in 1979. During ...

killed 1.5 to 2 million Cambodians in the Killing Fields, roughly a quarter of the population (commonly labelled the Cambodian genocide

The Cambodian genocide was the systematic persecution and killing of Cambodian citizens by the Khmer Rouge under the leadership of Pol Pot. It resulted in the deaths of 1.5 to 2 million people from 1975 to 1979, nearly 25% of Cambodia's populati ...

). Martin Shaw described these atrocities as "the purest genocide of the Cold War era." Backed by the Kampuchean United Front for National Salvation

The Kampuchean United Front for National Salvation (, UNGEGN: ''Rônâsĕrs Samôkki Sângkrŏăh Chéatĕ Kâmpŭchéa''; , FUNSK), often simply referred to as Salvation Front, was the nucleus of a new Cambodian regime that would topple the K ...

, an organization of Khmer pro-Soviet Communists and Khmer Rouge defectors, Vietnam invaded Cambodia on 22 December 1978. The invasion

An invasion is a Offensive (military), military offensive of combatants of one geopolitics, geopolitical Legal entity, entity, usually in large numbers, entering territory (country subdivision), territory controlled by another similar entity, ...

succeeded in deposing Pol Pot, but the new state struggled to gain international recognition beyond the Soviet Bloc sphere. Despite the international outcry at Pol Pot regime's gross human rights violations, representatives of the Khmer Rouge were allowed to be seated in the UN General Assembly

The United Nations General Assembly (UNGA or GA; , AGNU or AG) is one of the six principal organs of the United Nations (UN), serving as its main deliberative, policymaking, and representative organ. Currently in its 79th session, its powers, ...

, with strong support from China, Western powers, and the member countries of ASEAN

The Association of Southeast Asian Nations,

commonly abbreviated as ASEAN, is a regional grouping of 10 states in Southeast Asia "that aims to promote economic and security cooperation among its ten members." Together, its member states r ...

. Cambodia became bogged down in a guerrilla war led from refugee camps located on the border with Thailand

Thailand, officially the Kingdom of Thailand and historically known as Siam (the official name until 1939), is a country in Southeast Asia on the Mainland Southeast Asia, Indochinese Peninsula. With a population of almost 66 million, it spa ...

. Following the destruction of the Khmer Rouge, the national reconstruction of Cambodia was hampered, and Vietnam suffered a punitive Chinese attack. Although unable to deter Vietnam from ousting Pol Pot, China demonstrated that its Cold War communist adversary, the Soviet Union, was unable to protect its Vietnamese ally. Former U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger

Henry Alfred Kissinger (May 27, 1923 – November 29, 2023) was an American diplomat and political scientist who served as the 56th United States secretary of state from 1973 to 1977 and the 7th National Security Advisor (United States), natio ...

wrote that "China succeeded in exposing the limits of... ovietstrategic reach" and speculated that the desire to "compensate for their ineffectuality" contributed to the Soviets' decision to intervene in Afghanistan a year later.

French withdrawal from NATO military structures

The unity of NATO was breached early in its history, with a crisis occurring duringCharles de Gaulle

Charles André Joseph Marie de Gaulle (22 November 18909 November 1970) was a French general and statesman who led the Free France, Free French Forces against Nazi Germany in World War II and chaired the Provisional Government of the French Re ...

's presidency of France. De Gaulle protested at the strong role of the United States in the organization and what he perceived as a special relationship

The Special Relationship is an unofficial term for relations between the United Kingdom and the United States.

Special Relationship also may refer to:

* Special relationship (international relations), other exceptionally strong ties between nat ...

between the United States and the United Kingdom. In a memorandum sent to President Dwight D. Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower (born David Dwight Eisenhower; October 14, 1890 – March 28, 1969) was the 34th president of the United States, serving from 1953 to 1961. During World War II, he was Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionar ...

and Prime Minister Harold Macmillan

Maurice Harold Macmillan, 1st Earl of Stockton (10 February 1894 – 29 December 1986), was a British statesman and Conservative Party (UK), Conservative politician who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1957 to 1963. Nickn ...

on 17 September 1958, he argued for the creation of a tripartite directorate that would put France on an equal footing with the United States and the United Kingdom, and also for the expansion of NATO's coverage to include geographical areas of interest to France, most notably French Algeria

French Algeria ( until 1839, then afterwards; unofficially ; ), also known as Colonial Algeria, was the period of History of Algeria, Algerian history when the country was a colony and later an integral part of France. French rule lasted until ...

, where France was waging a counter-insurgency and sought NATO assistance. De Gaulle considered the response he received to be unsatisfactory and began the development of an independent French nuclear deterrent. In 1966, he withdrew France from NATO's military structures and expelled NATO troops from French soil.

Finlandization

Officially claiming to be neutral, Finland lay in the grey zone between the Western countries and the Soviet Union. The

Officially claiming to be neutral, Finland lay in the grey zone between the Western countries and the Soviet Union. The YYA Treaty

The Agreement of Friendship, Cooperation, and Mutual Assistance of 1948, also known as the YYA Treaty from the Finnish () ( Swedish: was the basis for Finno–Soviet relations from 1948 to 1992. It was the main instrument in implementing ...

(Finno-Soviet Pact of ''Friendship, Cooperation, and Mutual Assistance'') gave the Soviet Union some leverage in Finnish domestic politics, which was later used as the term "Finlandization" by the West German press, meaning "to become like Finland". This meant, among other things, the Soviet adaptation spread to the editors of mass media

Mass media include the diverse arrays of media that reach a large audience via mass communication.

Broadcast media transmit information electronically via media such as films, radio, recorded music, or television. Digital media comprises b ...

, sparking strong forms of self-control, self-censorship Self-censorship is the act of censoring or classifying one's own discourse, typically out of fear or deference to the perceived preferences, sensibilities, or infallibility of others, and often without overt external pressure. Self-censorship is c ...

(which included the banning of anti-Soviet books) and pro-Soviet attitudes. Most of the elite of media and politics shifted their attitudes to match the values that the Soviets were thought to favor and approve. Only after the ascent of Mikhail Gorbachev

Mikhail Sergeyevich Gorbachev (2 March 1931 – 30 August 2022) was a Soviet and Russian politician who served as the last leader of the Soviet Union from 1985 to dissolution of the Soviet Union, the country's dissolution in 1991. He served a ...

to Soviet leadership in 1985 did mass media in Finland gradually begin to criticise the Soviet Union more. When the Soviet Union allowed non-communist governments to take power in Eastern Europe, Gorbachev suggested they could look to Finland as an example to follow.

For West German conservative politicians, especially the Bavaria

Bavaria, officially the Free State of Bavaria, is a States of Germany, state in the southeast of Germany. With an area of , it is the list of German states by area, largest German state by land area, comprising approximately 1/5 of the total l ...

n Prime Minister Franz Josef Strauss, the case of Finlandization served as a warning, for example, about how a great power dictates its much smaller neighbor in its internal affairs and the neighbor's independence becomes formal. During the Cold War, Finlandization was seen not only in Bavaria but also in Western intelligence service

An intelligence agency is a government agency responsible for the collection, analysis, and exploitation of information in support of law enforcement, national security, military, public safety, and foreign policy objectives.

Means of info ...

s as a threat that completely free states had to be warned about in advance. To combat Finlandization, propaganda books and newspaper articles were published through CIA-funded research institutes and media companies, which denigrated Finnish neutrality policy and its pro-Soviet President Urho Kekkonen

Urho Kaleva Kekkonen (; 3 September 1900 – 31 August 1986), often referred to by his initials UKK, was a Finnish politician who served as the eighth and longest-serving president of Finland from 1956 to 1982. He also served as Prime Minister ...

; this was one factor in making room for the East-West espionage on Finnish soil between the two great powers.

However, Finland maintained capitalism

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their use for the purpose of obtaining profit. This socioeconomic system has developed historically through several stages and is defined by ...

unlike most other countries bordering the Soviet Union. Even though being a neighbor to the Soviet Union sometimes resulted in overcautious concern in foreign policy, Finland developed closer co-operation with the other Nordic countries

The Nordic countries (also known as the Nordics or ''Norden''; ) are a geographical and cultural region in Northern Europe, as well as the Arctic Ocean, Arctic and Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic oceans. It includes the sovereign states of Denm ...

and declared itself even more neutral in superpower politics, although in the later years, support for capitalism was even more widespread.Growth and Equity in FinlandWorld Bank

1968 invasion of Czechoslovakia

A period of political liberalization took place in 1968 inEastern Bloc

The Eastern Bloc, also known as the Communist Bloc (Combloc), the Socialist Bloc, the Workers Bloc, and the Soviet Bloc, was an unofficial coalition of communist states of Central and Eastern Europe, Asia, Africa, and Latin America that were a ...

country Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia ( ; Czech language, Czech and , ''Česko-Slovensko'') was a landlocked country in Central Europe, created in 1918, when it declared its independence from Austria-Hungary. In 1938, after the Munich Agreement, the Sudetenland beca ...

called the Prague Spring. The event was spurred by several events, including economic reforms that addressed an early 1960s economic downturn. In April, Czechoslovakian leader Alexander Dubček

Alexander Dubček (; 27 November 1921 – 7 November 1992) was a Slovaks, Slovak statesman who served as the First Secretary of the Presidium of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia (KSČ) (''de facto'' leader of Czech ...

launched an " Action Program" of liberalizations, which included increasing freedom of the press, freedom of speech and freedom of movement, along with an economic emphasis on consumer goods

A final good or consumer good is a final product ready for sale that is used by the consumer to satisfy current wants or needs, unlike an intermediate good, which is used to produce other goods. A microwave oven or a bicycle is a final good.

W ...

, the possibility of a multiparty government and limiting the power of the secret police. Initial reaction within the Eastern Bloc was mixed, with Hungary

Hungary is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning much of the Pannonian Basin, Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Croatia and ...

's János Kádár

János József Kádár (; ; né Czermanik; 26 May 1912 – 6 July 1989) was a Hungarian Communist leader and the General Secretary of the Hungarian Socialist Workers' Party, a position he held for 32 years. Declining health led to his retireme ...

expressing support, while Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev

Leonid Ilyich Brezhnev (19 December 190610 November 1982) was a Soviet politician who served as the General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1964 until Death and state funeral of Leonid Brezhnev, his death in 1982 as w ...

and others grew concerned about Dubček's reforms, which they feared might weaken the Eastern Bloc's position during the Cold War. On August 3, representatives from the Soviet Union, East Germany, Poland, Hungary, Bulgaria, and Czechoslovakia met in Bratislava

Bratislava (German: ''Pressburg'', Hungarian: ''Pozsony'') is the Capital city, capital and largest city of the Slovakia, Slovak Republic and the fourth largest of all List of cities and towns on the river Danube, cities on the river Danube. ...

and signed the Bratislava Declaration

The Bratislava Declaration was the result of the conference held in Bratislava on 3 August 1968 by the representatives of the Communist and Worker's parties of People's Republic of Bulgaria, Bulgaria, Hungarian People's Republic, Hungary, E ...

, which declaration affirmed unshakable fidelity to Marxism-Leninism and proletarian internationalism

Proletarian internationalism, sometimes referred to as international socialism, is the perception of all proletarian revolutions as being part of a single global class struggle rather than separate localized events. It is based on the theory th ...

and declared an implacable struggle against "bourgeois" ideology and all "anti-socialist" forces.

On the night of August 20–21, 1968, Eastern Bloc armies from four Warsaw Pact countries – the Soviet Union, Bulgaria

Bulgaria, officially the Republic of Bulgaria, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern portion of the Balkans directly south of the Danube river and west of the Black Sea. Bulgaria is bordered by Greece and Turkey t ...

, Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It extends from the Baltic Sea in the north to the Sudetes and Carpathian Mountains in the south, bordered by Lithuania and Russia to the northeast, Belarus and Ukrai ...

and Hungary

Hungary is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning much of the Pannonian Basin, Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Croatia and ...

– invaded Czechoslovakia. The invasion comported with the Brezhnev Doctrine, a policy of compelling Eastern Bloc states to subordinate national interests to those of the Bloc as a whole and the exercise of a Soviet right to intervene if an Eastern Bloc country appeared to shift towards capitalism. The invasion was followed by a wave of emigration, including an estimated 70,000 Czechs initially fleeing, with the total eventually reaching 300,000. In April 1969, Dubček was replaced as first secretary by Gustáv Husák

Gustáv Husák ( , ; ; 10 January 1913 – 18 November 1991) was a Czechoslovak politician who served as the long-time First Secretary of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia from 1969 to 1987 and the President of Czechoslovakia from 1975 ...

, and a period of "normalization

Normalization or normalisation refers to a process that makes something more normal or regular. Science

* Normalization process theory, a sociological theory of the implementation of new technologies or innovations

* Normalization model, used in ...

" began. Husák reversed Dubček's reforms, purged the party of liberal members, dismissed opponents from public office, reinstated the power of the police authorities, sought to re-centralize

Centralisation or centralization (American English) is the process by which the activities of an organisation, particularly those regarding planning, decision-making, and framing strategies and policies, become concentrated within a particular ...

the economy and re-instated the disallowance of political commentary in mainstream media and by persons not considered to have "full political trust". The international image of the Soviet Union suffered considerably, especially among Western student movements inspired by the "New Left

The New Left was a broad political movement that emerged from the counterculture of the 1960s and continued through the 1970s. It consisted of activists in the Western world who, in reaction to the era's liberal establishment, campaigned for freer ...

" and non-Aligned Movement states. Mao Zedong

Mao Zedong pronounced ; traditionally Romanization of Chinese, romanised as Mao Tse-tung. (26December 18939September 1976) was a Chinese politician, revolutionary, and political theorist who founded the People's Republic of China (PRC) in ...

's People's Republic of China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. With population of China, a population exceeding 1.4 billion, it is the list of countries by population (United Nations), second-most populous country after ...

, for example, condemned both the Soviets and the Americans as imperialists.

Brezhnev Doctrine