classical anarchism on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

According to different scholars, the history of anarchism either goes back to ancient and prehistoric

ideologies

An ideology is a set of beliefs or values attributed to a person or group of persons, especially those held for reasons that are not purely about belief in certain knowledge, in which "practical elements are as prominent as theoretical ones". Form ...

and social structures

In the social sciences, social structure is the aggregate of patterned social arrangements in society that are both emergent from and determinant of the actions of individuals. Likewise, society is believed to be grouped into structurally rel ...

, or begins in the 19th century as a formal movement. As scholars and anarchist philosophers have held a range of views on what anarchism means, it is difficult to outline its history unambiguously. Some feel anarchism is a distinct, well-defined movement stemming from 19th-century class conflict

In political science, the term class conflict, class struggle, or class war refers to the economic antagonism and political tension that exist among social classes because of clashing interests, competition for limited resources, and inequali ...

, while others identify anarchist traits long before the earliest civilisations existed.

Prehistoric

Prehistory, also called pre-literary history, is the period of human history between the first known use of stone tools by hominins million years ago and the beginning of recorded history with the invention of writing systems. The use o ...

society existed without formal hierarchies

A hierarchy (from Greek: , from , 'president of sacred rites') is an arrangement of items (objects, names, values, categories, etc.) that are represented as being "above", "below", or "at the same level as" one another. Hierarchy is an importan ...

, which some anthropologists have described as similar to anarchism

Anarchism is a political philosophy and Political movement, movement that seeks to abolish all institutions that perpetuate authority, coercion, or Social hierarchy, hierarchy, primarily targeting the state (polity), state and capitalism. A ...

. The first traces of formal anarchist thought can be found in ancient Greece

Ancient Greece () was a northeastern Mediterranean civilization, existing from the Greek Dark Ages of the 12th–9th centuries BC to the end of classical antiquity (), that comprised a loose collection of culturally and linguistically r ...

and China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. With population of China, a population exceeding 1.4 billion, it is the list of countries by population (United Nations), second-most populous country after ...

, where numerous philosophers questioned the necessity of the state

State most commonly refers to:

* State (polity), a centralized political organization that regulates law and society within a territory

**Sovereign state, a sovereign polity in international law, commonly referred to as a country

**Nation state, a ...

and declared the moral right of the individual to live free from coercion. During the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the 5th to the late 15th centuries, similarly to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire and ...

, some religious sect

A sect is a subgroup of a religious, political, or philosophical belief system, typically emerging as an offshoot of a larger organization. Originally, the term referred specifically to religious groups that had separated from a main body, but ...

s espoused libertarian thought, and the Age of Enlightenment

The Age of Enlightenment (also the Age of Reason and the Enlightenment) was a Europe, European Intellect, intellectual and Philosophy, philosophical movement active from the late 17th to early 19th century. Chiefly valuing knowledge gained th ...

, and the attendant rise of rationalism

In philosophy, rationalism is the Epistemology, epistemological view that "regards reason as the chief source and test of knowledge" or "the position that reason has precedence over other ways of acquiring knowledge", often in contrast to ot ...

and science

Science is a systematic discipline that builds and organises knowledge in the form of testable hypotheses and predictions about the universe. Modern science is typically divided into twoor threemajor branches: the natural sciences, which stu ...

, signalled the birth of the modern anarchist movement.

Alongside Marxism

Marxism is a political philosophy and method of socioeconomic analysis. It uses a dialectical and materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to analyse class relations, social conflict, ...

, modern anarchism was a significant part of the workers' movement

The labour movement is the collective organisation of Working class, working people to further their shared political and economic interests. It consists of the trade union or labour union movement, as well as political parties of labour. It ca ...

at the end of the 19th century. Modernism, industrialisation, reaction to capitalism and mass migration helped anarchism to flourish and to spread around the globe. Major anarchist schools of thought

Anarchism is a political philosophy and movement that seeks to abolish all institutions that perpetuate authority, coercion, or hierarchy, primarily targeting the state and capitalism. Anarchism advocates for the replacement of the state ...

sprouted up as anarchism grew as a social movement, particularly anarcho-collectivism, anarcho-communism

Anarchist communism is a far-left political ideology and anarchist school of thought that advocates communism. It calls for the abolition of private real property but retention of personal property and collectively-owned items, goods, and se ...

, anarcho-syndicalism

Anarcho-syndicalism is an anarchism, anarchist organisational model that centres trade unions as a vehicle for class conflict. Drawing from the theory of libertarian socialism and the practice of syndicalism, anarcho-syndicalism sees trade uni ...

, and individualist anarchism

Individualist anarchism or anarcho-individualism is a collection of anarchist

Anarchism is a political philosophy and Political movement, movement that seeks to abolish all institutions that perpetuate authority, coercion, or Social hi ...

. As the workers' movement grew, the divide between anarchists and Marxists grew as well. The two currents formally split at the fifth congress of the First International

The International Workingmen's Association (IWA; 1864–1876), often called the First International, was a political international which aimed at uniting a variety of different left-wing socialist, social democratic, communist, and anarchist ...

in 1872. Anarchists participated enthusiastically in the Russian Revolution

The Russian Revolution was a period of Political revolution (Trotskyism), political and social revolution, social change in Russian Empire, Russia, starting in 1917. This period saw Russia Dissolution of the Russian Empire, abolish its mona ...

, but as soon as the Bolsheviks

The Bolsheviks, led by Vladimir Lenin, were a radical Faction (political), faction of the Marxist Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) which split with the Mensheviks at the 2nd Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party, ...

established their authority, anarchist movements, most notably the Makhnovshchina

The Makhnovshchina (, ) was a Political movement#Mass movements, mass movement to establish anarchist communism in southern Ukraine, southern and eastern Ukraine during the Ukrainian War of Independence of 1917–1921. Named after Nestor Makhno, ...

and the Kronstadt rebellion

The Kronstadt rebellion () was a 1921 insurrection of Soviet sailors, Marines, naval infantry, and civilians against the Bolsheviks, Bolshevik government in the Russian port city of Kronstadt. Located on Kotlin Island in the Gulf of Finland, ...

, were harshly suppressed.

Anarchism played a historically prominent role during the Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War () was a military conflict fought from 1936 to 1939 between the Republican faction (Spanish Civil War), Republicans and the Nationalist faction (Spanish Civil War), Nationalists. Republicans were loyal to the Left-wing p ...

, when an anarchist territory was established in Catalonia. Revolutionary Catalonia was organised along anarcho-syndicalist lines, with powerful labor union

A trade union (British English) or labor union (American English), often simply referred to as a union, is an organization of workers whose purpose is to maintain or improve the conditions of their employment, such as attaining better wages ...

s in the cities and collectivised agriculture in the country, but ended in the defeat of the anarchists.

In the 1960s, anarchism re-emerged as a global political and cultural force. In association with the New Left

The New Left was a broad political movement that emerged from the counterculture of the 1960s and continued through the 1970s. It consisted of activists in the Western world who, in reaction to the era's liberal establishment, campaigned for freer ...

and Post-left tendencies, anarchism has influenced social movements that espouse personal autonomy and direct democracy. It has also played major roles in the anti-globalization movement

The anti-globalization movement, or counter-globalization movement, is a social movement critical of economic globalization. The movement is also commonly referred to as the global justice movement, alter-globalization movement, anti-globalist m ...

, Zapatista revolution, and Rojava revolution.

Background

Τhere has been some controversy over the definition of anarchism and hence its history. One group of scholars considersanarchism

Anarchism is a political philosophy and Political movement, movement that seeks to abolish all institutions that perpetuate authority, coercion, or Social hierarchy, hierarchy, primarily targeting the state (polity), state and capitalism. A ...

strictly associated with class struggle

In political science, the term class conflict, class struggle, or class war refers to the economic antagonism and political tension that exist among social classes because of clashing interests, competition for limited resources, and inequali ...

. Others feel this perspective is far too narrow. While the former group examines anarchism as a phenomenon that occurred during the 19th century, the latter group looks to ancient history to trace anarchism's roots. Anarchist philosopher Murray Bookchin

Murray Bookchin (; January 14, 1921 – July 30, 2006) was an American social theorist, author, orator, historian, and political philosopher. Influenced by G. W. F. Hegel, Karl Marx, and Peter Kropotkin, he was a pioneer in the environmental ...

describes the continuation of the "legacy of freedom" of humankind (i.e. the revolutionary moments) that existed throughout history, in contrast with the "legacy of domination" which consists of states, capitalism and other organisational forms.

The three most common forms of defining anarchism are the "etymological" (an-archei, without a ruler, but anarchism is not merely a negation); the "anti-statism" (while this seems to be pivotal, it certainly does not describe the essence of anarchism); and the "anti-authoritarian" definition (denial of every kind of authority, which over-simplifies anarchism). Along with the definition debates, the question of whether it is a philosophy, a theory or a series of actions complicates the issue. Philosophy professor Alejandro de Agosta proposes that anarchism is "a decentralized federation of philosophies as well as practices and ways of life, forged in different communities and affirming diverse geohistories".

Precursors

Prehistoric and ancient era

Many scholars of anarchism, including anthropologists Harold Barclay andDavid Graeber

David Rolfe Graeber (; February 12, 1961 – September 2, 2020) was an American and British anthropologist, Left-wing politics, left-wing and anarchism, anarchist social and political activist. His influential work in Social anthropology, social ...

, claim that some form of anarchy

Anarchy is a form of society without rulers. As a type of stateless society, it is commonly contrasted with states, which are centralized polities that claim a monopoly on violence over a permanent territory. Beyond a lack of government, it can ...

dates back to prehistory. The longest period of human existence, that before the recorded history of human society, was without a separate class of established authority or formal political institutions. Long before anarchism emerged as a distinct perspective, humans lived for thousands of years in self-governing societies without a special ruling or political class. It was only after the rise of hierarchical societies that anarchist ideas were formulated as a critical response to, and a rejection of, coercive political institutions and hierarchical social relationships.

Taoism

Taoism or Daoism (, ) is a diverse philosophical and religious tradition indigenous to China, emphasizing harmony with the Tao ( zh, p=dào, w=tao4). With a range of meaning in Chinese philosophy, translations of Tao include 'way', 'road', ' ...

, which developed in ancient China

The history of China spans several millennia across a wide geographical area. Each region now considered part of the Chinese world has experienced periods of unity, fracture, prosperity, and strife. Chinese civilization first emerged in the Y ...

, has been linked to anarchist thought by some scholars. Taoist sages Lao Tzu

Laozi (), also romanized as Lao Tzu #Name, among other ways, was a semi-legendary Chinese philosophy, Chinese philosopher and author of the ''Tao Te Ching'' (''Laozi''), one of the foundational texts of Taoism alongside the ''Zhuangzi (book) ...

and Zhuang Zhou

Zhuang Zhou (), commonly known as Zhuangzi (; ; literally "Master Zhuang"; also rendered in the Wade–Giles romanization as Chuang Tzu), was an influential Chinese philosopher who lived around the 4th century BCE during the Warring States p ...

, whose principles were grounded in an "anti-polity" stance and a rejection of any kind of involvement in political movements or organisations, developed a philosophy of "non-rule" in the ''Tao Te Ching

The ''Tao Te Ching'' () or ''Laozi'' is a Chinese classic text and foundational work of Taoism traditionally credited to the sage Laozi, though the text's authorship and date of composition and compilation are debated. The oldest excavated por ...

'' and the '' Zhuangzi''. Taoists were trying to live in harmony with nature according to the precepts of their religion by doing this. There is an ongoing debate whether exhorting rulers not to rule is somehow an anarchist objective. A new generation of Taoist thinkers with anarchic leanings appeared during the chaotic Wei-Jin period. Taoism and neo-Taoism had principles more akin to a philosophical anarchisman attempt to delegitimise the state and question its moralityand were pacifist

Pacifism is the opposition to war or violence. The word ''pacifism'' was coined by the French peace campaigner Émile Arnaud and adopted by other peace activists at the tenth Universal Peace Congress in Glasgow in 1901. A related term is ''a ...

schools of thought, in contrast with their Western counterparts some centuries later. Former professor emeritus

''Emeritus/Emerita'' () is an honorary title granted to someone who retirement, retires from a position of distinction, most commonly an academic faculty position, but is allowed to continue using the previous title, as in "professor emeritus".

...

of history at California State University

The California State University (Cal State or CSU) is a Public university, public university system in California, and the List of largest universities and university networks by enrollment, largest public university system in the United States ...

Milton W. Meyer has stated that in his opinion, early Taoists were "early anarchists" who believed in concepts often found in states

State most commonly refers to:

* State (polity), a centralized political organization that regulates law and society within a territory

**Sovereign state, a sovereign polity in international law, commonly referred to as a country

**Nation state, a ...

such as anti-intellectualism

Anti-intellectualism is hostility to and mistrust of intellect, intellectuals, and intellectualism, commonly expressed as deprecation of education and philosophy and the dismissal of art, literature, history, and science as impractical, politica ...

and "laissez-faire

''Laissez-faire'' ( , from , ) is a type of economic system in which transactions between private groups of people are free from any form of economic interventionism (such as subsidies or regulations). As a system of thought, ''laissez-faire'' ...

". Taoist anarchists did not believe in religious traditions such as ritual

A ritual is a repeated, structured sequence of actions or behaviors that alters the internal or external state of an individual, group, or environment, regardless of conscious understanding, emotional context, or symbolic meaning. Traditionally ...

s and the concepts of morality

Morality () is the categorization of intentions, Decision-making, decisions and Social actions, actions into those that are ''proper'', or ''right'', and those that are ''improper'', or ''wrong''. Morality can be a body of standards or principle ...

and good and evil.

Some convictions and ideas deeply held by modern anarchists were first expressed in ancient Greece

Ancient Greece () was a northeastern Mediterranean civilization, existing from the Greek Dark Ages of the 12th–9th centuries BC to the end of classical antiquity (), that comprised a loose collection of culturally and linguistically r ...

. The first known political usage of the word ''anarchy'' () appeared in plays by Aeschylus

Aeschylus (, ; ; /524 – /455 BC) was an ancient Greece, ancient Greek Greek tragedy, tragedian often described as the father of tragedy. Academic knowledge of the genre begins with his work, and understanding of earlier Greek tragedy is large ...

and Sophocles

Sophocles ( 497/496 – winter 406/405 BC)Sommerstein (2002), p. 41. was an ancient Greek tragedian known as one of three from whom at least two plays have survived in full. His first plays were written later than, or contemporary with, those ...

in the fifth century BC. Ancient Greece also saw the first Western instance of anarchy as a philosophical ideal mainly, but not only, by the Cynics and Stoics

Stoicism is a school of Hellenistic philosophy that flourished in ancient Greece and Rome. The Stoics believed that the universe operated according to reason, ''i.e.'' by a God which is immersed in nature itself. Of all the schools of ancient ...

. The Cynics Diogenes of Sinope

Diogenes the Cynic, also known as Diogenes of Sinope (c. 413/403–c. 324/321 BC), was an ancient Greek philosopher and one of the founders of Cynicism. Renowned for his ascetic lifestyle, biting wit, and radical critiques of social conventi ...

and Crates of Thebes

Crates (; c. 365 – c. 285 BC) of Thebes, Greece, Thebes was a Ancient Greece, Greek Cynicism (philosophy), Cynic philosopher, the principal pupil of Diogenes, Diogenes of Sinope and the husband of Hipparchia of Maroneia who lived in t ...

are both supposed to have advocated for anarchistic forms of society, although little remains of their writings. Their most significant contribution was the radical approach of ''nomos'' (law) and ''physis'' (nature). Contrary to the rest of Greek philosophy, aiming to blend ''nomos'' and ''physis'' in harmony, Cynics dismissed ''nomos'' (and in consequence: the authorities, hierarchies, establishments and moral code of polis

Polis (: poleis) means 'city' in Ancient Greek. The ancient word ''polis'' had socio-political connotations not possessed by modern usage. For example, Modern Greek πόλη (polē) is located within a (''khôra''), "country", which is a πατ ...

) while promoting a way of life, based solely on ''physis''. Zeno of Citium

Zeno of Citium (; , ; c. 334 – c. 262 BC) was a Hellenistic philosophy, Hellenistic philosopher from Kition, Citium (, ), Cyprus.

He was the founder of the Stoicism, Stoic school of philosophy, which he taught in Athens from about 300 BC. B ...

, the founder of Stoicism

Stoicism is a school of Hellenistic philosophy that flourished in ancient Greece and Rome. The Stoics believed that the universe operated according to reason, ''i.e.'' by a God which is immersed in nature itself. Of all the schools of ancient ...

, who was much influenced by the Cynics, described his vision of an egalitarian utopia

A utopia ( ) typically describes an imagined community or society that possesses highly desirable or near-perfect qualities for its members. It was coined by Sir Thomas More for his 1516 book ''Utopia (book), Utopia'', which describes a fictiona ...

n society around 300 BC. Zeno's ''Republic

A republic, based on the Latin phrase ''res publica'' ('public affair' or 'people's affair'), is a State (polity), state in which Power (social and political), political power rests with the public (people), typically through their Representat ...

'' advocates a form of anarchic society where there is no need for state structures. He argued that although the necessary instinct of self-preservation

Self-preservation is a behavior or set of behaviors that ensures the survival of an organism. It is thought to be universal among all living organisms.

Self-preservation is essentially the process of an organism preventing itself from being harm ...

leads humans to egotism

Egotism is defined as the drive to maintain and enhance favorable views of oneself and generally features an inflated opinion of one's personal features and Importance#Value of importance and desire to be important, importance distinguished by a ...

, nature has supplied a corrective to it by providing man with another instinct, namely sociability. Like many modern anarchists, he believed that if people follow their instincts, they will have no need of law courts

A court is an institution, often a government entity, with the authority to adjudicate legal disputes between parties and administer justice in civil, criminal, and administrative matters in accordance with the rule of law.

Courts gene ...

or police, no temples and no public worship

Worship is an act of religious devotion usually directed towards a deity or God. For many, worship is not about an emotion, it is more about a recognition of a God. An act of worship may be performed individually, in an informal or formal group, ...

, and use no money— free gifts taking the place of monetary exchanges.

Socrates

Socrates (; ; – 399 BC) was a Ancient Greek philosophy, Greek philosopher from Classical Athens, Athens who is credited as the founder of Western philosophy and as among the first moral philosophers of the Ethics, ethical tradition ...

expressed some views appropriate to anarchism. He constantly questioned authority and at the centre of his philosophy stood every man's right to freedom of consciousness. Aristippus

Aristippus of Cyrene (; ; c. 435 – c. 356 BCE) was a hedonistic Greek philosopher and the founder of the Cyrenaic school of philosophy. He was a pupil of Socrates, but adopted a different philosophical outlook, teaching that the goal of life ...

, a pupil of Socrates and founder of the Hedonistic school, claimed that he did not wish either to rule or be ruled. He saw the State as a danger to personal autonomy. Not all ancient Greeks had anarchic tendencies. Other philosophers such as Plato

Plato ( ; Greek language, Greek: , ; born BC, died 348/347 BC) was an ancient Greek philosopher of the Classical Greece, Classical period who is considered a foundational thinker in Western philosophy and an innovator of the writte ...

and Aristotle

Aristotle (; 384–322 BC) was an Ancient Greek philosophy, Ancient Greek philosopher and polymath. His writings cover a broad range of subjects spanning the natural sciences, philosophy, linguistics, economics, politics, psychology, a ...

used the term anarchy negatively in association with democracy

Democracy (from , ''dēmos'' 'people' and ''kratos'' 'rule') is a form of government in which political power is vested in the people or the population of a state. Under a minimalist definition of democracy, rulers are elected through competitiv ...

which they mistrusted as inherently vulnerable and prone to deteriorate into tyranny

A tyrant (), in the modern English language, English usage of the word, is an autocracy, absolute ruler who is unrestrained by law, or one who has usurper, usurped a legitimate ruler's sovereignty. Often portrayed as cruel, tyrants may defen ...

.

Among the ancient precursors of anarchism are often ignored movements within ancient Judaism

Judaism () is an Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic, Monotheism, monotheistic, ethnic religion that comprises the collective spiritual, cultural, and legal traditions of the Jews, Jewish people. Religious Jews regard Judaism as their means of o ...

and Early Christianity

Early Christianity, otherwise called the Early Church or Paleo-Christianity, describes the History of Christianity, historical era of the Christianity, Christian religion up to the First Council of Nicaea in 325. Spread of Christianity, Christian ...

. As more contemporary literature shows, anti-state and anti-hierarchy positions can be found in the Tanakh

The Hebrew Bible or Tanakh (;"Tanach"

. ''

The French Revolution stands as a landmark in the history of anarchism. The use of revolutionary violence by masses would captivate anarchists of later centuries, with such events as the

The French Revolution stands as a landmark in the history of anarchism. The use of revolutionary violence by masses would captivate anarchists of later centuries, with such events as the

In 1864, the creation of the

In 1864, the creation of the

Due to a high influx of European immigrants, Chicago was the centre of the American anarchist movement during the 19th century. On 1 May 1886, a general strike was called in several United States cities with the demand of an eight-hour work day, and anarchists allied themselves with the workers' movement despite seeing the objective as

Due to a high influx of European immigrants, Chicago was the centre of the American anarchist movement during the 19th century. On 1 May 1886, a general strike was called in several United States cities with the demand of an eight-hour work day, and anarchists allied themselves with the workers' movement despite seeing the objective as

The use of revolutionary

The use of revolutionary

The

The  Anarchists of CNT-FAI faced a major dilemma after the coup had failed in July 1936: either continue their fight against the state or join the anti-fascist left-wing parties and form a government. They opted for the latter and by November 1936, four members of CNT-FAI became ministers in the government of the former trade unionist

Anarchists of CNT-FAI faced a major dilemma after the coup had failed in July 1936: either continue their fight against the state or join the anti-fascist left-wing parties and form a government. They opted for the latter and by November 1936, four members of CNT-FAI became ministers in the government of the former trade unionist

Anarchism found fertile ground in Asia and was the most vibrant ideology among other socialist currents during the first decades of 20th century. The works of European philosophers, especially Kropotkin's, were popular among revolutionary youth. Intellectuals tried to link anarchism to earlier philosophical currents in Asia, like Taoism,

Anarchism found fertile ground in Asia and was the most vibrant ideology among other socialist currents during the first decades of 20th century. The works of European philosophers, especially Kropotkin's, were popular among revolutionary youth. Intellectuals tried to link anarchism to earlier philosophical currents in Asia, like Taoism,

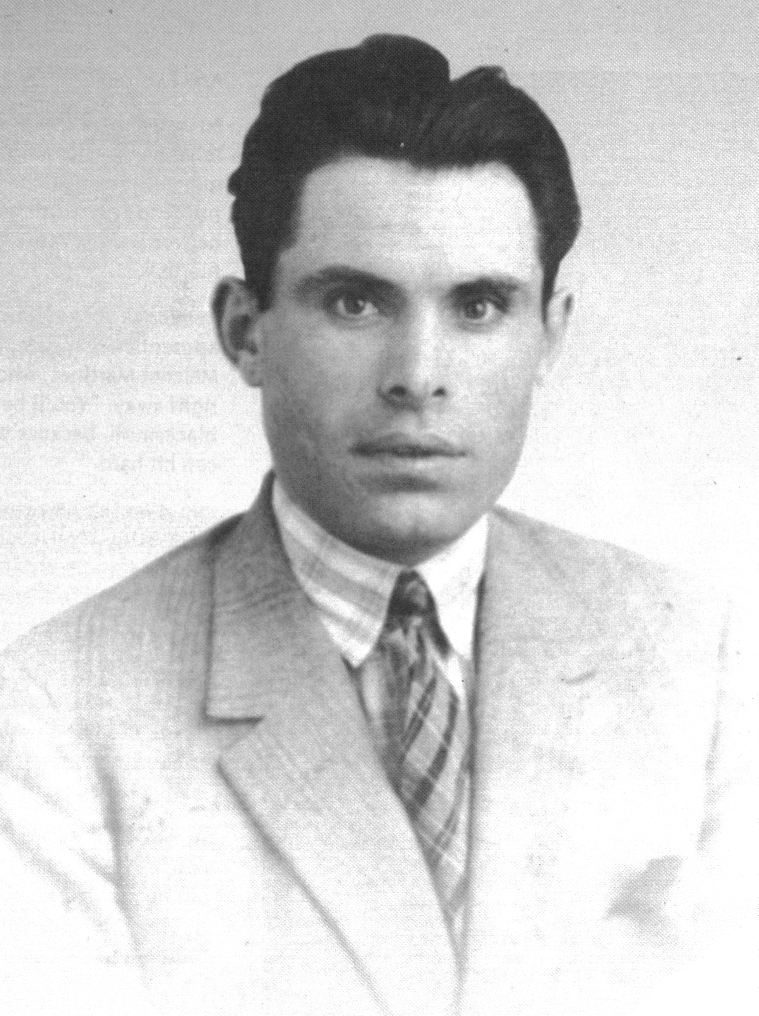

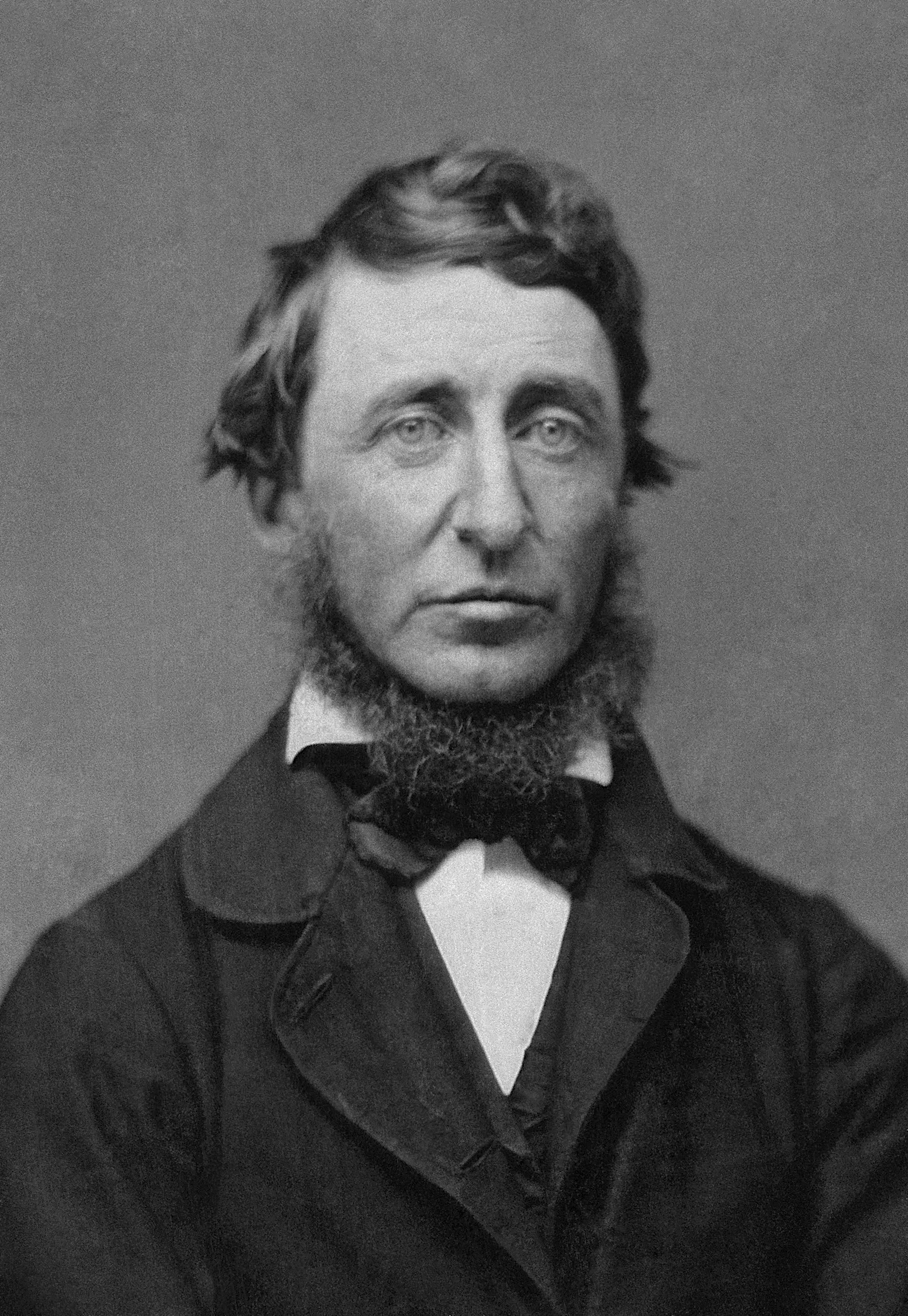

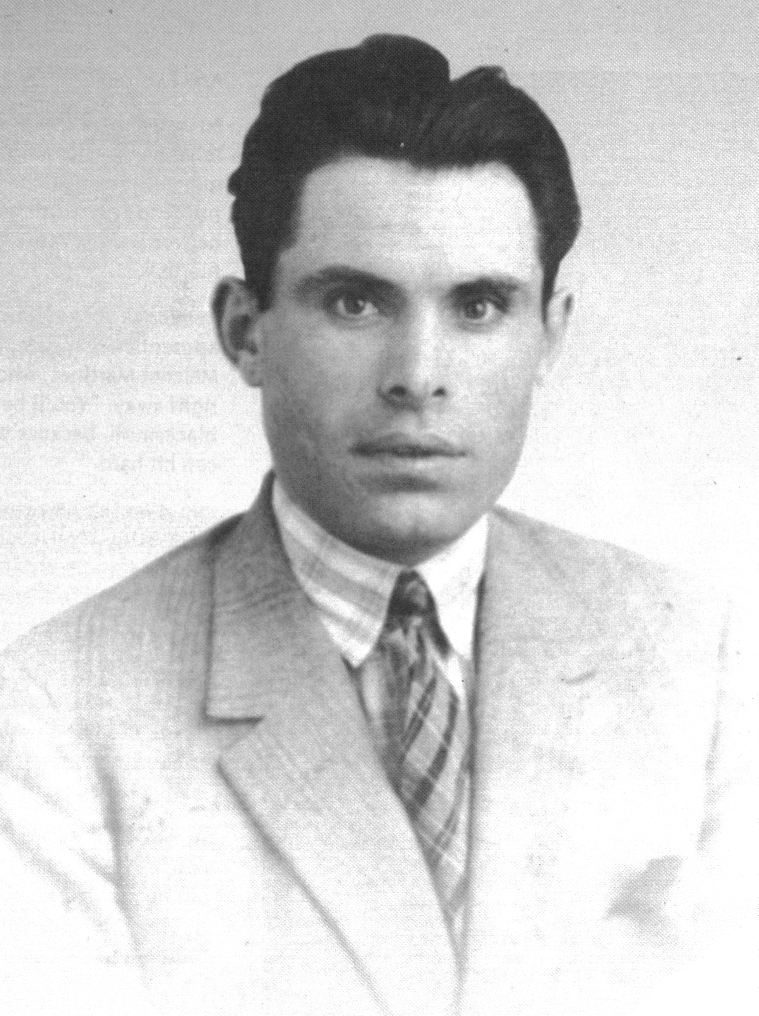

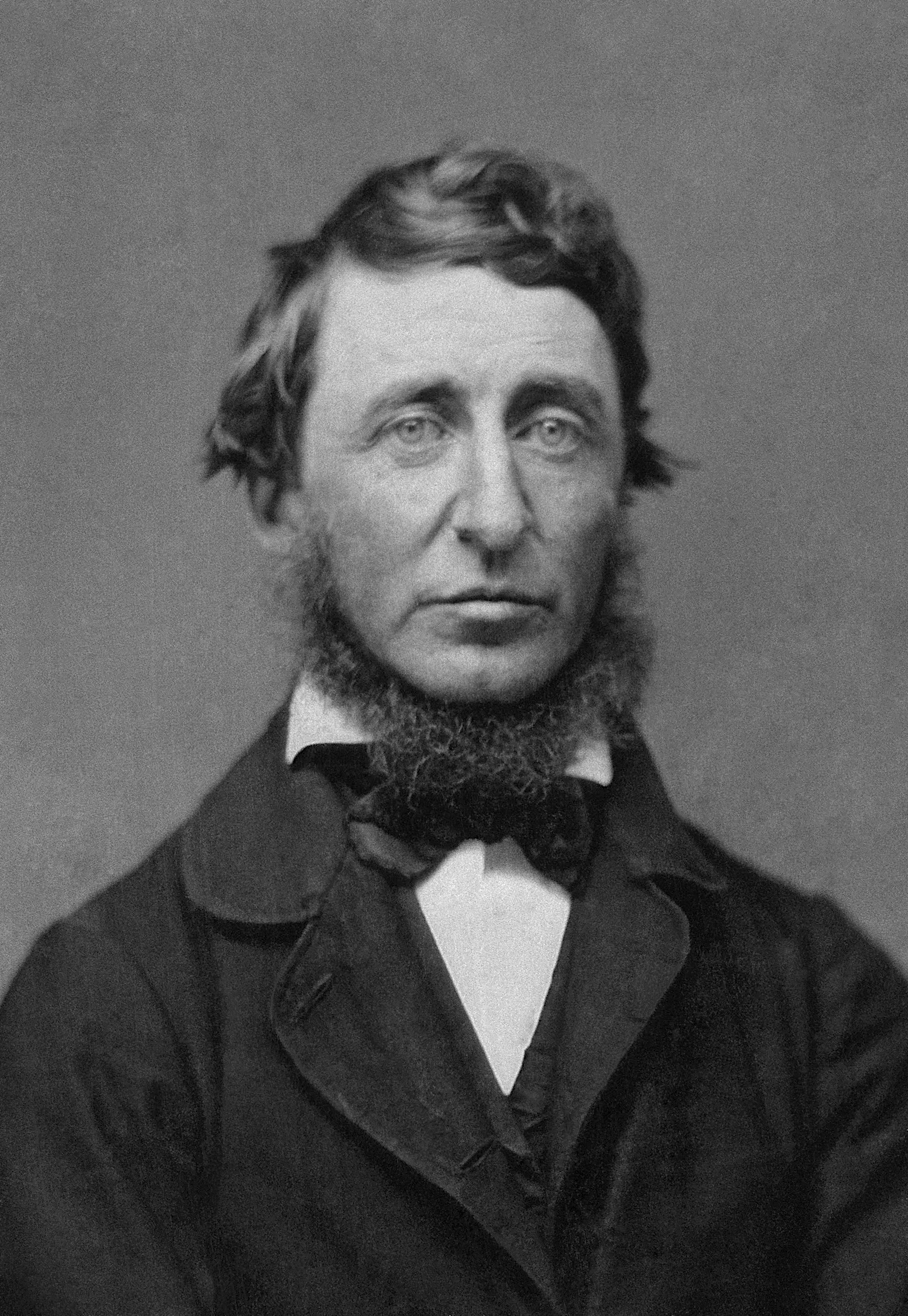

American anarchism has its roots in religious groups that fled Europe to escape European wars of religion, religious persecution during the 17th century. It sprouted towards individual anarchism as distrust of government was widespread in North America during the next centuries. In sharp contrast with their European counterparts, according to the scholar Marshall, American anarchism was leaning towards individualism and was mainly pro-capitalist, hence described as right-libertarianism, right-wing libertarianism; however Marshall later stated that capitalism and anarchism are incompatible and American anarchists like Tucker and Spooner were left libertarians. The scholar Martin stated the American anarchists were Mutualism (economic theory), mutualist anarchists in support of the labor theory of value. American anarchist justified private property as the safeguard of personal autonomy. Henry David Thoreau was an important early influence on individualist anarchist thought in the United States in the mid 19th century. He was skeptical towards government—in his work ''Civil Disobedience (Thoreau), Civil Disobedience'' he declared that ''"That government is best which governs least"''. He has frequently been cited as an anarcho-individualist, even though he was never rebellious. Josiah Warren was, at the late 19th century, a prominent advocate of a variant of mutualism called equitable commerce, a fair trade system where the price of a product is based on labor effort instead of the cost of manufacturing.

American anarchism has its roots in religious groups that fled Europe to escape European wars of religion, religious persecution during the 17th century. It sprouted towards individual anarchism as distrust of government was widespread in North America during the next centuries. In sharp contrast with their European counterparts, according to the scholar Marshall, American anarchism was leaning towards individualism and was mainly pro-capitalist, hence described as right-libertarianism, right-wing libertarianism; however Marshall later stated that capitalism and anarchism are incompatible and American anarchists like Tucker and Spooner were left libertarians. The scholar Martin stated the American anarchists were Mutualism (economic theory), mutualist anarchists in support of the labor theory of value. American anarchist justified private property as the safeguard of personal autonomy. Henry David Thoreau was an important early influence on individualist anarchist thought in the United States in the mid 19th century. He was skeptical towards government—in his work ''Civil Disobedience (Thoreau), Civil Disobedience'' he declared that ''"That government is best which governs least"''. He has frequently been cited as an anarcho-individualist, even though he was never rebellious. Josiah Warren was, at the late 19th century, a prominent advocate of a variant of mutualism called equitable commerce, a fair trade system where the price of a product is based on labor effort instead of the cost of manufacturing.

European individualist anarchism proceeded from the roots laid by

European individualist anarchism proceeded from the roots laid by

In France, a wave of protests and demonstrations confronted the right-wing government of Charles de Gaulle in May 68, May 1968. Even though the anarchists had a minimal role, the events of May had a significant impact on anarchism. There were huge demonstrations with crowds in some places reaching one million participants. Strikes were called in many major cities and towns involving seven million workers—all grassroots, bottom-up and spontaneously organised. Various committees were formed at universities, lyceums, and in neighbourhoods, mostly having anti-authoritarian tendencies. Slogans that resonated with libertarian ideas were prominent such as: "I take my desires for reality, because I believe in the reality of my desires." Even though the spirit of the events leaned mostly towards libertarian communism, some authors draw a connection to anarchism. The wave of protests eased when a 10% pay raise was granted and national elections were proclaimed. The paving stones of Paris were only covering some reformist victories. Nevertheless, the 1968 events inspired a new confidence in anarchism as workers' management, self-determination, grassroots democracy, antiauthoritarianism, and spontaneity became relevant once more. After decades of pessimism 1968 marked the revival of anarchism, either as a distinct ideology or as a part of other social movements.

Originally founded in 1957, The Situationist International rose to prominence during events of 1968 with the principal argument that life had turned into a "spectacle" because of the corrosive effect of capitalism. They later dissolved in 1972. The late 1960s saw the flourish of anarcha-feminism. It attacked the state, capitalism and patriarchy and was organized in a decentralised manner. Black anarchism began to take form at this time and influenced anarchism's move from a Eurocentric demographic.

As the ecological crisis was becoming a greater threat to the planet,

In France, a wave of protests and demonstrations confronted the right-wing government of Charles de Gaulle in May 68, May 1968. Even though the anarchists had a minimal role, the events of May had a significant impact on anarchism. There were huge demonstrations with crowds in some places reaching one million participants. Strikes were called in many major cities and towns involving seven million workers—all grassroots, bottom-up and spontaneously organised. Various committees were formed at universities, lyceums, and in neighbourhoods, mostly having anti-authoritarian tendencies. Slogans that resonated with libertarian ideas were prominent such as: "I take my desires for reality, because I believe in the reality of my desires." Even though the spirit of the events leaned mostly towards libertarian communism, some authors draw a connection to anarchism. The wave of protests eased when a 10% pay raise was granted and national elections were proclaimed. The paving stones of Paris were only covering some reformist victories. Nevertheless, the 1968 events inspired a new confidence in anarchism as workers' management, self-determination, grassroots democracy, antiauthoritarianism, and spontaneity became relevant once more. After decades of pessimism 1968 marked the revival of anarchism, either as a distinct ideology or as a part of other social movements.

Originally founded in 1957, The Situationist International rose to prominence during events of 1968 with the principal argument that life had turned into a "spectacle" because of the corrosive effect of capitalism. They later dissolved in 1972. The late 1960s saw the flourish of anarcha-feminism. It attacked the state, capitalism and patriarchy and was organized in a decentralised manner. Black anarchism began to take form at this time and influenced anarchism's move from a Eurocentric demographic.

As the ecological crisis was becoming a greater threat to the planet,

The anthropology of anarchism has changed in the contemporary era as the traditional lines or ideas of the 19th century have been abandoned. Most anarchists are now younger activists informed with feminist and ecological concerns. They are involved in Counterculture of the 1960s, counterculture, Black Power, creating temporary autonomous zones, and events such as Carnival Against Capital. These movements are not ''anarchist'', but rather ''anarchistic''.

Mexico saw another uprising at the turn of the 21st century. Zapatista Army of National Liberation, Zapatistas took control of a large area in Chiapas. They were organised in an autonomous, self-governing model that has many parallels to anarchism, inspiring many young anarchists in the West. Another stateless region that has been associated with anarchism is the Kurdish area of Rojava conflict, Rojava in northern Syria. The conflict there emerged during the Syrian Civil War and Rojava's decentralized model is founded upon Bookchin's ideas of libertarian municipalism and social ecology within a secular framework and ethnic diversity. Chiapas and Rojava share the same goal, to create a libertarian community despite being surrounded by state apparatus.

Anarchism grew in popularity and influence as part of the anti-war, anti-capitalist, and anti-globalisation movements. Maia Ramnath described those social movements that employ the anarchist framework (leaderless, direct democracy) but do not call themselves anarchists as anarchists with a lowercase ''a'' while describing more traditional forms of anarchism with a capital ''A''. Anarchists became known for their involvement in protests against meetings such as the 1999 Seattle WTO protests, World Trade Organization in Seattle in 1999, 27th G8 summit, Group of Eight in 2001 and the World Economic Forum, as part of anti-globalisation movement. Some anarchist factions at these protests engaged in rioting, property destruction, and violent confrontations with police. These actions were precipitated by ad hoc, leaderless, anonymous cadres known as black blocs. Other organisational tactics pioneered during this period include security culture, affinity groups and the use of decentralised technologies such as the Internet. Occupy Wall Street movement had roots in anarchist philosophy.

According to anarchist scholar Simon Critchley, "contemporary anarchism can be seen as a powerful critique of the pseudo-libertarianism of contemporary neo-liberalism [...] One might say that contemporary anarchism is about responsibility, whether sexual, ecological, or socio-economic; it flows from an experience of conscience about the manifold ways in which the West ravages the rest; it is an ethical outrage at the yawning inequality, impoverishment, and disenfranchisement that is so palpable locally and globally". While having revolutionary aspirations, many contemporary forms of anarchism are not confrontational. Instead, they are trying to build an alternative way of social organization (following the theories of dual power), based on Mutual aid, mutual interdependence and voluntary cooperation, for instance in groups such as Food Not Bombs and in self-managed social centers. Scholar Carissa Honeywell takes the example of Food Not Bombs group of collectives, to highlight some features of how contemporary anarchist groups work: direct action, working together and in solidarity with those left behind. While doing so, Food Not Bombs provides consciousness raising about the rising rates of world hunger and suggest policies to tackle hunger, ranging from Funding, de-funding the arms industry to addressing Monsanto Seed saving, seed-saving policies and patents, helping farmers, and resisting the commodification of food and housing. Honeywell also emphasizes that contemporary anarchists are interested in the flourishing not only of humans, but Animal, non-humans and the Environmentalism, environment as well. Honeywell argues that their analysis of capitalism and governments results in anarchists Anti-politics, rejecting representative democracy and the state as a whole.

The anthropology of anarchism has changed in the contemporary era as the traditional lines or ideas of the 19th century have been abandoned. Most anarchists are now younger activists informed with feminist and ecological concerns. They are involved in Counterculture of the 1960s, counterculture, Black Power, creating temporary autonomous zones, and events such as Carnival Against Capital. These movements are not ''anarchist'', but rather ''anarchistic''.

Mexico saw another uprising at the turn of the 21st century. Zapatista Army of National Liberation, Zapatistas took control of a large area in Chiapas. They were organised in an autonomous, self-governing model that has many parallels to anarchism, inspiring many young anarchists in the West. Another stateless region that has been associated with anarchism is the Kurdish area of Rojava conflict, Rojava in northern Syria. The conflict there emerged during the Syrian Civil War and Rojava's decentralized model is founded upon Bookchin's ideas of libertarian municipalism and social ecology within a secular framework and ethnic diversity. Chiapas and Rojava share the same goal, to create a libertarian community despite being surrounded by state apparatus.

Anarchism grew in popularity and influence as part of the anti-war, anti-capitalist, and anti-globalisation movements. Maia Ramnath described those social movements that employ the anarchist framework (leaderless, direct democracy) but do not call themselves anarchists as anarchists with a lowercase ''a'' while describing more traditional forms of anarchism with a capital ''A''. Anarchists became known for their involvement in protests against meetings such as the 1999 Seattle WTO protests, World Trade Organization in Seattle in 1999, 27th G8 summit, Group of Eight in 2001 and the World Economic Forum, as part of anti-globalisation movement. Some anarchist factions at these protests engaged in rioting, property destruction, and violent confrontations with police. These actions were precipitated by ad hoc, leaderless, anonymous cadres known as black blocs. Other organisational tactics pioneered during this period include security culture, affinity groups and the use of decentralised technologies such as the Internet. Occupy Wall Street movement had roots in anarchist philosophy.

According to anarchist scholar Simon Critchley, "contemporary anarchism can be seen as a powerful critique of the pseudo-libertarianism of contemporary neo-liberalism [...] One might say that contemporary anarchism is about responsibility, whether sexual, ecological, or socio-economic; it flows from an experience of conscience about the manifold ways in which the West ravages the rest; it is an ethical outrage at the yawning inequality, impoverishment, and disenfranchisement that is so palpable locally and globally". While having revolutionary aspirations, many contemporary forms of anarchism are not confrontational. Instead, they are trying to build an alternative way of social organization (following the theories of dual power), based on Mutual aid, mutual interdependence and voluntary cooperation, for instance in groups such as Food Not Bombs and in self-managed social centers. Scholar Carissa Honeywell takes the example of Food Not Bombs group of collectives, to highlight some features of how contemporary anarchist groups work: direct action, working together and in solidarity with those left behind. While doing so, Food Not Bombs provides consciousness raising about the rising rates of world hunger and suggest policies to tackle hunger, ranging from Funding, de-funding the arms industry to addressing Monsanto Seed saving, seed-saving policies and patents, helping farmers, and resisting the commodification of food and housing. Honeywell also emphasizes that contemporary anarchists are interested in the flourishing not only of humans, but Animal, non-humans and the Environmentalism, environment as well. Honeywell argues that their analysis of capitalism and governments results in anarchists Anti-politics, rejecting representative democracy and the state as a whole.

History of Anarchism

Kate Sharpley Library. {{anarchism History of anarchism,

. ''

New Testament

The New Testament (NT) is the second division of the Christian biblical canon. It discusses the teachings and person of Jesus in Christianity, Jesus, as well as events relating to Christianity in the 1st century, first-century Christianit ...

texts.

Middle Ages

In Persia during the Middle Ages aZoroastrian

Zoroastrianism ( ), also called Mazdayasnā () or Beh-dīn (), is an Iranian religion centred on the Avesta and the teachings of Zarathushtra Spitama, who is more commonly referred to by the Greek translation, Zoroaster ( ). Among the wo ...

prophet named Mazdak

Mazdak (, Middle Persian: 𐭬𐭦𐭣𐭪, also Mazdak the Younger; died c. 524 or 528) was an Iranian Zoroastrian '' mobad'' (priest) and religious reformer who gained influence during the reign of the Sasanian emperor Kavadh I. He claimed to ...

, now considered a proto-socialist, called for the abolition of private property, free love and overthrowing the king. He and his thousands of followers were massacred in 582 CE, but his teaching influenced Islamic sects in the following centuries. A theological predecessor to anarchism developed in Basra

Basra () is a port city in Iraq, southern Iraq. It is the capital of the eponymous Basra Governorate, as well as the List of largest cities of Iraq, third largest city in Iraq overall, behind Baghdad and Mosul. Located near the Iran–Iraq bor ...

and Baghdad

Baghdad ( or ; , ) is the capital and List of largest cities of Iraq, largest city of Iraq, located along the Tigris in the central part of the country. With a population exceeding 7 million, it ranks among the List of largest cities in the A ...

among Mu'tazilite ascetics and Najdiyya Khirijites. This form of revolutionary Islam was not communist or egalitarian. It did not resemble current concepts of anarchism, but preached the State was harmful, illegitimate, immoral and unnecessary.

In Europe, Christianity was overshadowing all aspects of life. The Brethren of the Free Spirit was the most notable example of heretic belief that had some vague anarchistic tendencies. They held anticleric sentiments and believed in total freedom. Even though most of their ideas were individualistic, the movement had a social impact, instigating riots and rebellions in Europe for many years. Other anarchistic religious movements in Europe during the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the 5th to the late 15th centuries, similarly to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire and ...

included the Hussites

upright=1.2, Battle between Hussites (left) and Crusades#Campaigns against heretics and schismatics, Catholic crusaders in the 15th century

upright=1.2, The Lands of the Bohemian Crown during the Hussite Wars. The movement began during the Prag ...

and Adamites.

20th-century historian James Joll

James Bysse Joll FBA (21 June 1918 – 12 July 1994) was a British historian and university lecturer whose works included ''The Origins of the First World War'' and ''Europe Since 1870''. He also wrote on the history of anarchism and socialism ...

described anarchism as two opposing sides. In the Middle Ages, zealotic and ascetic religious movements emerged, which rejected institutions, laws and the established order. In the 18th century another anarchist stream emerged based on rationalism and logic. These two currents of anarchism later blended to form a contradictory movement that resonated with a very broad audience.

Renaissance and early modern era

With the spread of theRenaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) is a Periodization, period of history and a European cultural movement covering the 15th and 16th centuries. It marked the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and was characterized by an effort to revive and sur ...

across Europe, anti-authoritarian and secular ideas re-emerged. The most prominent thinkers advocating for liberty, mainly French, were employing utopia

A utopia ( ) typically describes an imagined community or society that possesses highly desirable or near-perfect qualities for its members. It was coined by Sir Thomas More for his 1516 book ''Utopia (book), Utopia'', which describes a fictiona ...

in their works to bypass strict state censorship. In ''Gargantua and Pantagruel

''The Five Books of the Lives and Deeds of Gargantua and Pantagruel'' (), often shortened to ''Gargantua and Pantagruel'' or the (''Five Books''), is a pentalogy of novels written in the 16th century by François Rabelais. It tells the advent ...

'' (1532–1552), François Rabelais

François Rabelais ( , ; ; born between 1483 and 1494; died 1553) was a French writer who has been called the first great French prose author. A Renaissance humanism, humanist of the French Renaissance and Greek scholars in the Renaissance, Gr ...

wrote of the Abby of Thelema

Thelema () is a Western esotericism, Western esoteric and occult social or spiritual philosophy and a new religious movement founded in the early 1900s by Aleister Crowley (1875–1947), an English writer, mystic, occultist, and ceremonial ma ...

(from ; meaning "will" or "wish"), an imaginary utopia whose motto was "Do as Thou Will". Around the same time, French law student Etienne de la Boetie wrote his '' Discourse on Voluntary Servitude'' where he argued that tyranny resulted from voluntary submission and could be abolished by the people refusing to obey the authorities above them. Later still in France, Gabriel de Foigny perceived a utopia with freedom-loving people without government and no need of religion, as he wrote in '' The Southern Land, Known''. For this, Geneva authorities jailed de Foigny. François Fénelon

François de Salignac de la Mothe-Fénelon, PSS (), more commonly known as François Fénelon (6 August 1651 – 7 January 1715), was a French Catholic archbishop, theologian, poet and writer. Today, he is remembered mostly as the author of ' ...

also used utopia to project his political views in the book ''Les Aventures de Télémaque

:''"Les Aventures de Télémaque" is also the title of a 1922 seven-chapter story by Louis Aragon.''

''Les Aventures de Télémaque, fils d'Ulysse'' () is a didactic novel by François Fénelon, Archbishop of Cambrai, who in 1689 became tutor to ...

'' that infuriated Louis XIV

LouisXIV (Louis-Dieudonné; 5 September 16381 September 1715), also known as Louis the Great () or the Sun King (), was King of France from 1643 until his death in 1715. His verified reign of 72 years and 110 days is the List of longest-reign ...

.

Some Reformation

The Reformation, also known as the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation, was a time of major Theology, theological movement in Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the p ...

currents (like the radical reformist movement of Anabaptists

Anabaptism (from Neo-Latin , from the Greek : 're-' and 'baptism'; , earlier also )Since the middle of the 20th century, the German-speaking world no longer uses the term (translation: "Re-baptizers"), considering it biased. The term (tra ...

) are sometimes credited as the religious forerunners of modern anarchism. Even though the Reformation was a religious movement and strengthened the state, it also opened the way for the humanistic values of the French Revolution. During the English Civil War

The English Civil War or Great Rebellion was a series of civil wars and political machinations between Cavaliers, Royalists and Roundhead, Parliamentarians in the Kingdom of England from 1642 to 1651. Part of the wider 1639 to 1653 Wars of th ...

, Christian anarchism

Christian anarchism is a Christian movement in political theology that claims anarchism is inherent in Christianity and the Gospels. It is grounded in the belief that there is only one source of authority to which Christians are ultimately answ ...

found one of its most articulate exponents in Gerrard Winstanley

Gerrard Winstanley (baptised 19 October 1609 – 10 September 1676) was an English Protestant religious reformer, political philosopher, and activist during the period of the Commonwealth of England. Winstanley was the leader and one of the fo ...

, who was part of the Diggers

The Diggers were a group of religious and political dissidents in England, associated with a political ideology and programme resembling what would later be called agrarian socialism.; ; ; Gerrard Winstanley and William Everard (Digger), Will ...

movement. He published a pamphlet, ''The New Law of Righteousness'', calling for communal ownership and social and economic organisation in small agrarian communities. Drawing on the Bible, he argued that "the blessings of the earth" should "be common to all" and "none Lord over others". William Blake

William Blake (28 November 1757 – 12 August 1827) was an English poet, painter, and printmaker. Largely unrecognised during his life, Blake has become a seminal figure in the history of the Romantic poetry, poetry and visual art of the Roma ...

has also been said to have espoused an anarchistic political position.

In the New World

The term "New World" is used to describe the majority of lands of Earth's Western Hemisphere, particularly the Americas, and sometimes Oceania."America." ''The Oxford Companion to the English Language'' (). McArthur, Tom, ed., 1992. New York: ...

, the first to use the term "anarchy" to mean something other than chaos was Louis-Armand, Baron de Lahontan in his '' Nouveaux voyages dans l'Amérique septentrionale'', 1703 (''New Voyages in Northern America''). He described indigenous American society as having no state, laws, prisons, priests or private property as being in anarchy.

The Quaker

Quakers are people who belong to the Religious Society of Friends, a historically Protestant Christian set of denominations. Members refer to each other as Friends after in the Bible, and originally, others referred to them as Quakers ...

sect, mostly because of their ahierarchical governance and social relations, based on their beliefs of the divine spirit universally within all people and humanity's absolute equality, had some anarchistic tendencies; such values must have influenced Benjamin Tucker

Benjamin Ricketson Tucker (; April 17, 1854 – June 22, 1939) was an American individualist anarchist and self-identified socialist. Tucker was the editor and publisher of the American individualist anarchist periodical ''Liberty'' (1881–19 ...

the editor and publisher of the individualist anarchist periodical ''Liberty''.

Early anarchism

Developments of the 18th century

Modern anarchism grew from the secular and humanistic thought of the Enlightenment. The scientific discoveries that preceded the Enlightenment gave thinkers of the time confidence that humans can reason for themselves. When nature was tamed through science, society could be set free. The development of anarchism was strongly influenced by the works ofJean Meslier

Jean Meslier (; also Mellier; 15 June 1664 – 17 June 1729) was a French Catholic priest (abbé) who was discovered, upon his death, to have written a book-length philosophical essay promoting atheism and materialism. Described by the author as ...

, Baron d'Holbach

Paul Thiry, Baron d'Holbach (; ; 8 December 1723 – 21 January 1789), known as d'Holbach, was a Franco-German philosopher, encyclopedist and writer, who was a prominent figure in the French Enlightenment. He was born in Edesheim, near Landau ...

, whose materialistic worldview later resonated with anarchists, and Jean-Jacques Rousseau

Jean-Jacques Rousseau (, ; ; 28 June 1712 – 2 July 1778) was a Republic of Geneva, Genevan philosopher (''philosophes, philosophe''), writer, and composer. His political philosophy influenced the progress of the Age of Enlightenment through ...

, especially in his ''Discourse on Inequality

''Discourse on the Origin and Basis of Inequality Among Men'' (), also commonly known as the "Second Discourse", is a 1755 treatise by philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau, on the topic of social inequality and its origins. The work was written in ...

'' and arguments for the moral centrality of freedom. Rousseau affirmed the goodness in the nature of men and viewed the state as fundamentally oppressive. Denis Diderot

Denis Diderot (; ; 5 October 171331 July 1784) was a French philosopher, art critic, and writer, best known for serving as co-founder, chief editor, and contributor to the along with Jean le Rond d'Alembert. He was a prominent figure during th ...

's '' Supplément au voyage de Bougainville'' (''The Supplement to the Voyage of Bougainville'') was also influential.

The French Revolution stands as a landmark in the history of anarchism. The use of revolutionary violence by masses would captivate anarchists of later centuries, with such events as the

The French Revolution stands as a landmark in the history of anarchism. The use of revolutionary violence by masses would captivate anarchists of later centuries, with such events as the Women's March on Versailles

The Women's March on Versailles, also known as the Black March, the October Days or simply the March on Versailles, was one of the earliest and most significant events of the French Revolution. The march began among women in the marketplaces of ...

, the Storming of the Bastille

The Storming of the Bastille ( ), which occurred in Paris, France, on 14 July 1789, was an act of political violence by revolutionary insurgents who attempted to storm and seize control of the medieval armoury, fortress, and political prison k ...

and the Réveillon riots seen as the revolutionary archetype. Anarchists came to identify with the '' Enragés'' () who expressed the demands of the ''sans-culottes

The (; ) were the working class, common people of the social class in France, lower classes in late 18th-century history of France, France, a great many of whom became radical and militant partisans of the French Revolution in response to their ...

'' (; commoners) who opposed revolutionary government as a contradiction in terms. Denouncing the Jacobin

The Society of the Friends of the Constitution (), renamed the Society of the Jacobins, Friends of Freedom and Equality () after 1792 and commonly known as the Jacobin Club () or simply the Jacobins (; ), was the most influential political cl ...

dictatorship, Jean Varlet wrote in 1794 that "government and revolution are incompatible, unless the people wish to set its constituted authorities in permanent insurrection against itself". In his ''Manifeste des Égaux'' (''Manifesto of the Equals'') of 1801, Sylvain Maréchal

Sylvain Maréchal (; 15 August 1750 – 18 January 1803) was a French essayist, poet, philosopher and political theorist, whose views presaged utopian socialism and communism. His views on a future golden age are occasionally described as ''uto ...

looked forward to the disappearance, once and for all, of "the revolting distinction between rich and poor, of great and small, of masters and valets, of governors and governed". The French Revolution came to depict in the minds of anarchists that as soon as rebels seize power they become the new tyrants, as evidenced by the state-orchestrated violence of the Reign of Terror

The Reign of Terror (French: ''La Terreur'', literally "The Terror") was a period of the French Revolution when, following the creation of the French First Republic, First Republic, a series of massacres and Capital punishment in France, nu ...

. The proto-anarchist groups of ''Enragés'' and ''sans-culottes'' were ultimately executed by guillotine.

The debate over the effects of the French Revolution on the anarchist cause continues to this day. To anarchist historian Max Nettlau, the French revolution was a turning point in anarchistic thought, as it promoted the ideals of " Liberty, Fraternity, and Equality". Yet he felt that the outcome did nothing more than re-shape and modernise the militaristic state. Russian revolutionary and anarchist thinker Peter Kropotkin

Pyotr Alexeyevich Kropotkin (9 December 1842 – 8 February 1921) was a Russian anarchist and geographer known as a proponent of anarchist communism.

Born into an aristocratic land-owning family, Kropotkin attended the Page Corps and later s ...

, however, traced the origins of the anarchist movement further back, linking it to struggles against authority in feudal societies and earlier revolutionary traditions. In a more moderate approach, independent scholar Sean Sheehan points out that the French Revolution proved that even the strongest political establishments can be overthrown.

William Godwin

William Godwin (3 March 1756 – 7 April 1836) was an English journalist, political philosopher and novelist. He is considered one of the first exponents of utilitarianism and the first modern proponent of anarchism. Godwin is most famous fo ...

in England was the first to develop an expression of modern anarchist thought. He is generally regarded as the founder of the school of thought known as philosophical anarchism. He argued in '' Political Justice'' (1793) that government has an inherently malevolent influence on society, and that it perpetuates dependency and ignorance. He thought the spread of the use of reason to the masses would eventually cause the government to wither away as an unnecessary force. Although he did not accord the state with moral legitimacy, he was against the use of revolutionary tactics for removing a government from power. Rather, he advocated for its replacement through a process of peaceful evolution. His aversion to the imposition of a rules-based society led him to denounce, as a manifestation of the people's "mental enslavement", the foundations of law, property rights

The right to property, or the right to own property (cf. ownership), is often classified as a human right for natural persons regarding their Possession (law), possessions. A general recognition of a right to private property is found more rarely ...

and even the institution of marriage. He considered the basic foundations of society as constraining the natural development of individuals to use their powers of reasoning to arrive at a mutually beneficial method of social organisation. In each case, government and its institutions are shown to constrain the development of one's capacity to live wholly in accordance with the full and free exercise of private judgement.

Proudhon and Stirner

FrenchmanPierre-Joseph Proudhon

Pierre-Joseph Proudhon (, ; ; 1809 – 19 January 1865) was a French anarchist, socialist, philosopher, and economist who founded mutualist philosophy and is considered by many to be the "father of anarchism". He was the first person to ca ...

is regarded as the founder of modern anarchism, a label he adopted in his groundbreaking work '' What is Property? Or, an Inquiry into the Principle of Right and Government'' () published in 1840. In it he asks "What is property?", a question that he answers with the famous accusation " Property is theft". Proudhon's theory of mutualism rejects the state, capitalism, and communism. It calls for a co-operative society in which the free associations of individuals are linked in a decentralised federation based on a "Bank of the People" that supplies workers with free credit. He contrasted this with what he called "possession", or limited ownership of resources and goods only while in more or less continuous use. Later, Proudhon also added that "Property is liberty" and argued that it was a bulwark against state power.

Mutualists would later play an important role in the First International

The International Workingmen's Association (IWA; 1864–1876), often called the First International, was a political international which aimed at uniting a variety of different left-wing socialist, social democratic, communist, and anarchist ...

, especially at the first two Congresses held in Geneva and Lausanne, but diminished in European influence with the rise of anarcho-communism. Instead, Mutualism would find fertile ground among American individualists in the late 19th century.

In Spain, Ramón de la Sagra

Ramón Dionisio José de la Sagra y Peris (8 April 179823 May 1871) was a Spanish people, Spanish anarchist, politician, writer, and botanist who founded the world's first anarchist journal, ''El Porvenir'' (Spanish for "The Future").

Biography

...

established the anarchist journal ''El Porvenir'' in La Coruña in 1845 which was inspired by Proudhon's ideas. Catalan politician Francesc Pi i Margall became the principal translator of Proudhon's works into Spanish. He would later briefly become president of Spain in 1873 while leader of the Democratic Republican Federal Party, where he tried to implement some of Proudhon's ideas.

An influential form of individualist anarchism

Individualist anarchism or anarcho-individualism is a collection of anarchist

Anarchism is a political philosophy and Political movement, movement that seeks to abolish all institutions that perpetuate authority, coercion, or Social hi ...

called egoism or egoist anarchism

Egoist anarchism or anarcho-egoism, often shortened as simply egoism, is a Anarchist schools of thought, school of anarchist thought that originated in the philosophy of Max Stirner, philosophy of Max Stirner, a 19th-century philosopher whose "n ...

, was expounded by one of the earliest and best-known proponents of individualist anarchism, German philosopher Max Stirner

Johann Kaspar Schmidt (; 25 October 1806 – 26 June 1856), known professionally as Max Stirner (; ), was a German post-Hegelian philosopher, dealing mainly with the Hegelian notion of social alienation and self-consciousness. Stirner is oft ...

. Stirner's ''The Ego and Its Own

''The Ego and Its Own'' (), also known as ''The Unique and Its Property'', is an 1844 work by German philosopher Max Stirner. It presents a post-Hegelian critique of Christianity and traditional morality on one hand; and on the other, humanism, ...

'' (; also translated as ''The Individual and his Property'' or ''The Unique and His Property''), published in 1844, is a founding text of the philosophy. Stirner was critical of capitalism as it creates class warfare where the rich will exploit the poor, using the state as its tool. He also rejected religions, communism and liberalism, as all of them subordinate individuals to God, a collective, or the state. According to Stirner the only limitation on the rights of the individual is their power to obtain what they desire, without regard for God, state, or morality. He held that society does not exist, but "the individuals are its reality". Stirner advocated self-assertion and foresaw unions of egoists, non-systematic associations continually renewed by all parties' support through an act of will, which proposed as a form of organisation in place of the state

State most commonly refers to:

* State (polity), a centralized political organization that regulates law and society within a territory

**Sovereign state, a sovereign polity in international law, commonly referred to as a country

**Nation state, a ...

. Egoist anarchists claimed that egoism will foster genuine and spontaneous union between individuals. Stirner was proposing an individual rebellion, which would not seek to establish new institutions nor anything resembling a state.

Revolutions of 1848

Europe was shocked by another revolutionary wave in 1848 which started once again in Paris. The new government, consisting mostly of Jacobins, was backed by the working class but failed to implement meaningful reforms.Pierre-Joseph Proudhon

Pierre-Joseph Proudhon (, ; ; 1809 – 19 January 1865) was a French anarchist, socialist, philosopher, and economist who founded mutualist philosophy and is considered by many to be the "father of anarchism". He was the first person to ca ...

and Russian revolutionary Mikhail Bakunin

Mikhail Alexandrovich Bakunin. Sometimes anglicized to Michael Bakunin. ( ; – 1 July 1876) was a Russian revolutionary anarchist. He is among the most influential figures of anarchism and a major figure in the revolutionary socialist, s ...

were involved in the events of 1848. The failure of the revolution shaped Proudhon's views. He became convinced that a revolution should aim to destroy authority, not grasp power. He saw capitalism

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their use for the purpose of obtaining profit. This socioeconomic system has developed historically through several stages and is defined by ...

as the root of social problems and government, using political tools only, as incapable of confronting the real issues. The course of events of 1848, radicalised Bakunin who, due to the failure of the revolutions, lost his confidence in any kind of reform.

Other anarchists active in the 1848 Revolution in France include Anselme Bellegarrigue, Ernest Coeurderoy and the early anarcho-communist Joseph Déjacque, who was the first person to call himself a libertarian. Unlike Proudhon, Déjacque argued that "it is not the product of his or her labour that the worker has a right to, but to the satisfaction of his or her needs, whatever may be their nature". Déjacque was also a critic of Proudhon's mutualist theory and anti-feminist views. Returning to New York, he was able to serialise his book in his periodical ''Le Libertaire, Journal du Mouvement social''. The French anarchist movement, though self-described as "mutualists", started gaining pace during 1860s as workers' associations began to form.

Classical anarchism

The decades of the late 19th and the early 20th centuries constitute the belle époque of anarchist history. In this "classical" era, roughly defined as the period between theParis Commune

The Paris Commune (, ) was a French revolutionary government that seized power in Paris on 18 March 1871 and controlled parts of the city until 28 May 1871. During the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–71, the French National Guard (France), Nation ...

of 1871 and the Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War () was a military conflict fought from 1936 to 1939 between the Republican faction (Spanish Civil War), Republicans and the Nationalist faction (Spanish Civil War), Nationalists. Republicans were loyal to the Left-wing p ...

of 1936 to 1939 (or the 1840s/1860s through 1939), anarchism played a prominent role in working-class struggles (alongside Marxism

Marxism is a political philosophy and method of socioeconomic analysis. It uses a dialectical and materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to analyse class relations, social conflict, ...

) in Europe as well as in the Americas, Asia, and Oceania. Modernism, mass migration, railroads and access to printing all helped anarchists to advance their causes.

First International and Paris Commune

In 1864, the creation of the

In 1864, the creation of the International Workingmen's Association

The International Workingmen's Association (IWA; 1864–1876), often called the First International, was a political international which aimed at uniting a variety of different left-wing socialist, social democratic, communist, and anarchist g ...

(IWA, also called the "First International") united diverse revolutionary currents - including socialist Marxists, trade unionists, communists and anarchists. Karl Marx

Karl Marx (; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, political theorist, economist, journalist, and revolutionary socialist. He is best-known for the 1848 pamphlet '' The Communist Manifesto'' (written with Friedrich Engels) ...

, a leading figure of the International, became a member of its General Council.

Four years later, in 1868, Mikhail Bakunin

Mikhail Alexandrovich Bakunin. Sometimes anglicized to Michael Bakunin. ( ; – 1 July 1876) was a Russian revolutionary anarchist. He is among the most influential figures of anarchism and a major figure in the revolutionary socialist, s ...

joined the First International with his collectivist anarchist associates. They advocated the collectivisation of property and the revolutionary overthrow of the state. Bakunin corresponded with other members of the International, seeking to establish a loose brotherhood of revolutionaries who would ensure that the coming revolution would not take an authoritarian course, in sharp contrast with other currents that were seeking to get a firm grasp on state power. Bakunin's energy and writings about a great variety of subjects, such as education and gender equality, helped to increase his influence within the IWA. His main line was that the International should try to promote a revolution without aiming to create a mere government of "experts". Workers should seek to emancipate their class with direct actions, using cooperatives, mutual credit, and strikes, but avoid participation in bourgeois politics. At first, the collectivists worked with the Marxists to push the First International in a more revolutionary socialist direction. Subsequently, the International became polarised into two camps, with Marx and Bakunin as their respective figureheads. Bakunin characterised Marx's ideas as centralist

Centralisation or centralization (American English) is the process by which the activities of an organisation, particularly those regarding planning, decision-making, and framing strategies and policies, become concentrated within a particular ...

. Because of this, he predicted that if a Marxist party came to power, its leaders would simply take the place of the ruling class

In sociology, the ruling class of a society is the social class who set and decide the political and economic agenda of society.

In Marxist philosophy, the ruling class are the class who own the means of production in a given society and apply ...

they had fought against. Followers of Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, the mutualists, also opposed Marx's state socialism, advocating political abstentionism

Abstentionism is the political practice of standing for election to a deliberative assembly while refusing to take up any seats won or otherwise participate in the assembly's business. Abstentionism differs from an election boycott in that abs ...

and small property holdings.

Meanwhile, an uprising after the Franco-Prussian War

The Franco-Prussian War or Franco-German War, often referred to in France as the War of 1870, was a conflict between the Second French Empire and the North German Confederation led by the Kingdom of Prussia. Lasting from 19 July 1870 to 28 Janua ...

of 1870 to 1871 led to the formation of the Paris Commune

The Paris Commune (, ) was a French revolutionary government that seized power in Paris on 18 March 1871 and controlled parts of the city until 28 May 1871. During the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–71, the French National Guard (France), Nation ...

in March 1871. Anarchists had a prominent role in the Commune,

next to Blanquists and - to a lesser extent - Marxists. The uprising was greatly influenced by anarchists and had a great impact on anarchist history. Radical socialist views, like Proudhonian federalism, were implemented to a small extent. Most importantly, the workers proved they could run their own services and factories. After the defeat of the Commune, anarchists like Eugène Varlin, Louise Michel

Louise Michel (; 29 May 1830 – 9 January 1905) was a teacher and prominent figure during the Paris Commune. Following her penal transportation to New Caledonia she began to embrace anarchism, and upon her return to France she emerged as an im ...

, and Élisée Reclus were shot or imprisoned. The French Third Republic

The French Third Republic (, sometimes written as ) was the system of government adopted in France from 4 September 1870, when the Second French Empire collapsed during the Franco-Prussian War, until 10 July 1940, after the Fall of France durin ...

persecuted socialist supporters for a decade. Leading members of the International who survived the bloody suppression of the Commune fled to Switzerland, where the Anarchist St. Imier International would form in 1872.

In 1872, the conflict between Marxists and anarchists climaxed. Marx had, since 1871, proposed the creation of a political party, which anarchists found to be an appalling and unacceptable prospect. Various groups (including Italian sections, the Belgian Federation and the Jura Federation) rejected Marx's proposition at the 1872 Hague Congress. They saw it as an attempt to create state socialism that would ultimately fail to emancipate humanity. In contrast, they proposed political struggle through social revolution. Finally, anarchists were expelled from the First International. In response, the federalist sections formed their own International at the St. Imier Congress, adopting a revolutionary anarchist programme.

Emergence of anarcho-communism

Anarcho-communism

Anarchist communism is a far-left political ideology and anarchist school of thought that advocates communism. It calls for the abolition of private real property but retention of personal property and collectively-owned items, goods, and se ...

developed out of radical socialist currents after the 1789 French Revolution but was first formulated as such in the Italian section of the First International

The International Workingmen's Association (IWA; 1864–1876), often called the First International, was a political international which aimed at uniting a variety of different left-wing socialist, social democratic, communist, and anarchist ...

. It was the convincing critique of Carlo Cafiero and Errico Malatesta

Errico Malatesta (4 December 1853 – 22 July 1932) was an Italian anarchist propagandist, theorist and revolutionary socialist. He edited several radical newspapers and spent much of his life exiled and imprisoned, having been jailed and expel ...