Cavalier-Smith on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Thomas (Tom) Cavalier-Smith, FRS, FRSC, NERC Professorial Fellow (21 October 1942 – 19 March 2021), was a professor of

Cavalier-Smith wrote extensively on the taxonomy and classification of all life forms, but especially

Cavalier-Smith wrote extensively on the taxonomy and classification of all life forms, but especially

Five of Cavalier-Smith's kingdoms are classified as

Five of Cavalier-Smith's kingdoms are classified as

evolutionary biology

Evolutionary biology is the subfield of biology that studies the evolutionary processes such as natural selection, common descent, and speciation that produced the diversity of life on Earth. In the 1930s, the discipline of evolutionary biolo ...

in the Department of Zoology, at the University of Oxford

The University of Oxford is a collegiate university, collegiate research university in Oxford, England. There is evidence of teaching as early as 1096, making it the oldest university in the English-speaking world and the List of oldest un ...

.

His research has led to discovery of a number of unicellular organisms (protist

A protist ( ) or protoctist is any eukaryotic organism that is not an animal, land plant, or fungus. Protists do not form a natural group, or clade, but are a paraphyletic grouping of all descendants of the last eukaryotic common ancest ...

s) and advocated for a variety of major taxonomic groups, such as the Chromista

Chromista is a proposed but polyphyletic obsolete Biology, biological Kingdom (biology), kingdom, refined from the Chromalveolata, consisting of single-celled and multicellular eukaryotic species that share similar features in their Photosynthesi ...

, Chromalveolata

Chromalveolata was a eukaryote supergroup present in a major classification of 2005, then regarded as one of the six major groups within the eukaryotes. It was a refinement of the kingdom Chromista, first proposed by Thomas Cavalier-Smith in 198 ...

, Opisthokont

The opisthokonts () are a broad group of eukaryotes, including both the animal and fungus kingdoms. The opisthokonts, previously called the "Fungi/Metazoa group", are generally recognized as a clade. Opisthokonts together with Apusomonadida and ...

a, Rhizaria

The Rhizaria are a diverse and species-rich clade of mostly unicellular eukaryotes. Except for the Chlorarachniophytes and three species in the genus '' Paulinella'' in the phylum Cercozoa, they are all non-photosynthetic, but many Foraminifera ...

, and Excavata

Excavata is an obsolete, extensive and diverse paraphyletic group of unicellular Eukaryota. The group was first suggested by Simpson and Patterson in 1999 and the name latinized and assigned a rank by Thomas Cavalier-Smith in 2002. It contains ...

. He was known for his systems of classification of all organisms.

Life and career

Cavalier-Smith was born on 21 October 1942 in London. His parents were Mary Maude (née Bratt) and Alan Hailes Spencer Cavalier Smith. He was educated atNorwich School

Norwich School (formally King Edward VI Grammar School, Norwich) is a private selective day school in the close of Norwich Cathedral, Norwich. Among the oldest schools in the United Kingdom, it has a traceable history to 1096 as an episcop ...

, Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge

Gonville and Caius College, commonly known as Caius ( ), is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge in Cambridge, England. Founded in 1348 by Edmund Gonville, it is the fourth-oldest of the University of Cambridge's 31 colleges and ...

(MA) in Biology and King's College London

King's College London (informally King's or KCL) is a public university, public research university in London, England. King's was established by royal charter in 1829 under the patronage of George IV of the United Kingdom, King George IV ...

(PhD) in Zoology. He was under the supervision of Sir John Randall for his PhD thesis between 1964 and 1967; his thesis was entitled "''Organelle Development in'' Chlamydomonas reinhardii".

From 1967 to 1969, Cavalier-Smith was a guest investigator at Rockefeller University

The Rockefeller University is a Private university, private Medical research, biomedical Research university, research and graduate-only university in New York City, New York. It focuses primarily on the biological and medical sciences and pro ...

. He became Lecturer of biophysics at King's College London

King's College London (informally King's or KCL) is a public university, public research university in London, England. King's was established by royal charter in 1829 under the patronage of George IV of the United Kingdom, King George IV ...

in 1969. He was promoted to Reader in 1982.

From the early 1980s, Smith promoted views about the taxonomic relationships among living organisms. He was prolific, drawing on a near-unparalleled wealth of information to suggest novel relationships.

In 1989 he was appointed Professor of Botany at the University of British Columbia

The University of British Columbia (UBC) is a Public university, public research university with campuses near University of British Columbia Vancouver, Vancouver and University of British Columbia Okanagan, Kelowna, in British Columbia, Canada ...

.

In 1999, he joined the University of Oxford

The University of Oxford is a collegiate university, collegiate research university in Oxford, England. There is evidence of teaching as early as 1096, making it the oldest university in the English-speaking world and the List of oldest un ...

, becoming Professor of evolutionary biology in 2000.

Thomas Cavalier-Smith died in March 2021 following the development of cancer.

Taxonomy

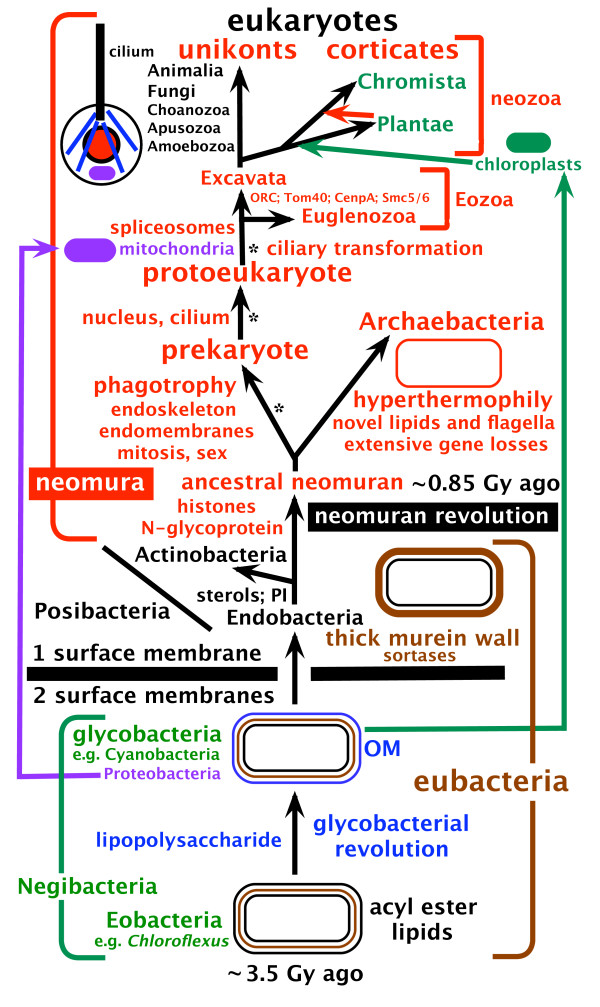

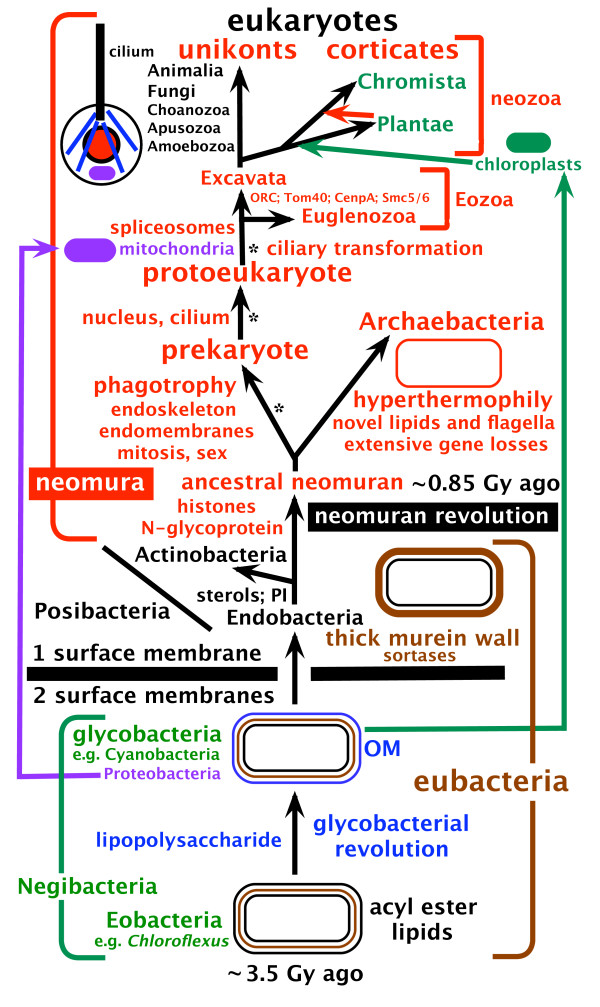

Cavalier-Smith was a prolific taxonomist, drawing on a near-unparalleled wealth of information to suggest novel relationships. His suggestions were translated into taxonomic concepts and classifications with which he associated new names, or in some cases, reused old names. Cavalier-Smith did not follow or espouse an explicit taxonomic philosophy but his approach was closest to evolutionary taxonomy. He and several other colleagues were opposed tocladistic

Cladistics ( ; from Ancient Greek 'branch') is an approach to biological classification in which organisms are categorized in groups ("clades") based on hypotheses of most recent common ancestry. The evidence for hypothesized relationships is ...

approaches to taxonomy arguing that the goals of cladification and classification were different; his approach was similar to that of many others' broad-based treatments of protists.

The scope of Cavalier-Smith's taxonomic propositions was grand, but the numbers and composition of the components (taxa), and, often, their relations were not stable. Propositions were often ambiguous and short-lived; he frequently amended taxa without any change in the name. His approach was not universally accepted: Others attempted to underpin taxonomy of protists with a nested series of atomised, falsifiable propositions, following the philosophy of transformed cladistics. However, this approach is no longer considered defensible.

Cavalier-Smith's ideas that led to the taxonomic structures were usually first presented in the form of tables and complex, annotated diagrams. When presented at scientific meetings, they were sometimes too rich, and often written too small, for the ideas to be easily grasped. Some such diagrams made their way into publications, where careful scrutiny was possible, and where the conjectural nature of some assertions was evident. The richness of his ideas, their continuing evolution, and the transition into taxonomies that gave Cavalier-Smith's investigations into evolutionary paths (phylogeny

A phylogenetic tree or phylogeny is a graphical representation which shows the evolutionary history between a set of species or Taxon, taxa during a specific time.Felsenstein J. (2004). ''Inferring Phylogenies'' Sinauer Associates: Sunderland, M ...

) and the resulting classifications, its distinctive character.

Cavalier-Smith's narrative style

Cavalier-Smith was courageous in his adherence to the earlier traditionalist style characterized byCharles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English Natural history#Before 1900, naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all speci ...

, that of relying on narratives. One example was his advocacy for the Chromista

Chromista is a proposed but polyphyletic obsolete Biology, biological Kingdom (biology), kingdom, refined from the Chromalveolata, consisting of single-celled and multicellular eukaryotic species that share similar features in their Photosynthesi ...

that united lineages that had plastids with chlorophylls a and c (primarily chrysophytes and other stramenopiles

The stramenopiles, also called heterokonts, are Protist, protists distinguished by the presence of stiff tripartite external hairs. In most species, the hairs are attached to flagella, in some they are attached to other areas of the cellular sur ...

, cryptophytes, and haptophytes) despite clear evidence that the group corresponded to a clade.

It was Cavalier-Smith's claim that there was a single endosymbiotic event by which chlorophyll a and c containing plastids were acquired by a common ancestor of all three groups, and that the differences (such as cytological components and their arrangements) among the groups were the result of subsequent evolutionary changes. This interpretation that chromists were monophyletic also required that the heterotrophic (protozoa

Protozoa (: protozoan or protozoon; alternative plural: protozoans) are a polyphyletic group of single-celled eukaryotes, either free-living or parasitic, that feed on organic matter such as other microorganisms or organic debris. Historically ...

n) members of all three groups had arisen from ancestors with plastids.

The alternative hypothesis was that the three chromophytic lineages were not closely related (to the exclusion of other lineages) (i.e. were polyphyletic), likely that all were ancestrally without plastids, and that separate symbiotic events established the chlorophyll a/c plastids stramenopiles, cryptomonads and haptophytes. The polyphyly of the chromists has been re-asserted in subsequent studies.

Cavalier-Smith's lack of an objective and reproducible methodology that translated evolutionary insights into taxa and hierarchical schemes, was often confusing to those who did not follow his publications closely. Many of his taxa required his frequent adjustment (as illustrated below). In turn this led to confusion as to the scope of taxa that a taxonomic name was applied to.

Cavalier-Smith also reused familiar names (such as Protozoa) for innovative taxonomic concepts. This created confusion because Protozoa was and still is used in its old sense, alongside its use in the newer senses. Because of Cavalier-Smith's tendency to publish rapidly and frequently change his narratives and taxonomic summaries, his approach and claims were frequently debated.

Palaeos Palaeos.com is a web site on biology, paleontology, phylogeny and geology and which covers the history of Earth. The site is well respected and has been used as a reference by professional paleontologists such as Michael J. Benton, the professor of ...

.com described his writing style as follows: Prof. Cavalier-Smith of Oxford University has produced a large body of work which is well regarded. Still, he is controversial in a way that is a bit difficult to describe. The issue may be one of writing style. Cavalier-Smith has a tendency to make pronouncements where others would use declarative sentences, to use declarative sentences where others would express an opinion, and to express opinions where angels would fear to tread. In addition, he can sound arrogant, reactionary, and even perverse. On the other and he has a long history of being right when everyone else was wrong. To our way of thinking, all of this is overshadowed by one incomparable virtue: the fact that he ''will'' grapple with the details. This makes for very long, very complex papers and causes all manner of dark murmuring, tearing of hair, and gnashing of teeth among those tasked with trying to explain his views of early life. See, or example Zrzavý (2001) ndPatterson (1999). Nevertheless, he deals with all of the relevant facts.

Cavalier-Smith's contributions

Cavalier-Smith wrote extensively on the taxonomy and classification of all life forms, but especially

Cavalier-Smith wrote extensively on the taxonomy and classification of all life forms, but especially protists

A protist ( ) or protoctist is any Eukaryote, eukaryotic organism that is not an animal, Embryophyte, land plant, or fungus. Protists do not form a Clade, natural group, or clade, but are a Paraphyly, paraphyletic grouping of all descendants o ...

. One of his major contributions to biology was his proposal of a new kingdom of life: the Chromista

Chromista is a proposed but polyphyletic obsolete Biology, biological Kingdom (biology), kingdom, refined from the Chromalveolata, consisting of single-celled and multicellular eukaryotic species that share similar features in their Photosynthesi ...

, even though it is not widely accepted to be monophyletic (see above).

He also introduced new taxonomic groupings group for eukaryotes such as the Chromalveolata

Chromalveolata was a eukaryote supergroup present in a major classification of 2005, then regarded as one of the six major groups within the eukaryotes. It was a refinement of the kingdom Chromista, first proposed by Thomas Cavalier-Smith in 198 ...

(1981), Opisthokonta (1987), Rhizaria

The Rhizaria are a diverse and species-rich clade of mostly unicellular eukaryotes. Except for the Chlorarachniophytes and three species in the genus '' Paulinella'' in the phylum Cercozoa, they are all non-photosynthetic, but many Foraminifera ...

(2002), and Excavata

Excavata is an obsolete, extensive and diverse paraphyletic group of unicellular Eukaryota. The group was first suggested by Simpson and Patterson in 1999 and the name latinized and assigned a rank by Thomas Cavalier-Smith in 2002. It contains ...

(2002). Though well known, many of his claims have been controversial and have not gained widespread acceptance in the scientific community

The scientific community is a diverse network of interacting scientists. It includes many "working group, sub-communities" working on particular scientific fields, and within particular institutions; interdisciplinary and cross-institutional acti ...

. His taxonomic revisions often influenced the overall classification of all life forms.

Eight kingdoms model

Cavalier-Smith's first major classification system was the division of all organisms into eight kingdoms. In 1981, he proposed that by completely revising Robert Whittaker's Five Kingdom system, there could be eight kingdoms: Bacteria, Eufungi, Ciliofungi, Animalia, Biliphyta, Viridiplantae, Cryptophyta, and Euglenozoa. In 1983, he revised his system particularly in the light of growing evidence that Archaebacteria were a separate group from Bacteria, to include an array of lineages that had been excluded from his 1981 treatment, to deal with issues of polyphyly, and to promote new ideas of relationships. In addition, some protists lacking mitochondria were discovered. As mitochondria were known to be the result of theendosymbiosis

An endosymbiont or endobiont is an organism that lives within the body or cells of another organism. Typically the two organisms are in a mutualism (biology), mutualistic relationship. Examples are nitrogen-fixing bacteria (called rhizobia), whi ...

of a proteobacterium, it was thought that these amitochondriate eukaryotes were primitively so, marking an important step in eukaryogenesis. As a result, these amitochondriate protists were given special status as a protozan subkingdom Archezoa, that he later elevated to kingdom status. This was later referred to as the Archezoa hypothesis. In 1993, the eight kingdoms became: Eubacteria, Archaebacteria, Archezoa, Protozoa, Chromista, Plantae, Fungi, and Animalia.

The kingdom Archezoa went through many compositional changes due to evidence of polyphyly and paraphyly before being abandoned. He assigned some former members of the kingdom Archezoa to the phylum Amoebozoa

Amoebozoa is a major Taxonomy (biology), taxonomic group containing about 2,400 described species of Amoeba, amoeboid protists, often possessing blunt, fingerlike, Pseudopod#Morphology, lobose pseudopods and tubular mitochondrial cristae. In trad ...

.

Six kingdoms models

By 1998, Cavalier-Smith had reduced the total number ofkingdoms

Kingdom commonly refers to:

* A monarchic state or realm ruled by a king or queen.

** A monarchic chiefdom, represented or governed by a king or queen.

* Kingdom (biology), a category in biological taxonomy

Kingdom may also refer to:

Arts and me ...

from eight to six: Animalia

Animals are multicellular, eukaryotic organisms in the Biology, biological Kingdom (biology), kingdom Animalia (). With few exceptions, animals heterotroph, consume organic material, Cellular respiration#Aerobic respiration, breathe oxygen, ...

, Protozoa

Protozoa (: protozoan or protozoon; alternative plural: protozoans) are a polyphyletic group of single-celled eukaryotes, either free-living or parasitic, that feed on organic matter such as other microorganisms or organic debris. Historically ...

, Fungi

A fungus (: fungi , , , or ; or funguses) is any member of the group of eukaryotic organisms that includes microorganisms such as yeasts and mold (fungus), molds, as well as the more familiar mushrooms. These organisms are classified as one ...

, Plantae

Plants are the eukaryotes that form the kingdom Plantae; they are predominantly photosynthetic. This means that they obtain their energy from sunlight, using chloroplasts derived from endosymbiosis with cyanobacteria to produce sugars fro ...

(including Glaucophyte, red

Red is the color at the long wavelength end of the visible spectrum of light, next to orange and opposite violet. It has a dominant wavelength of approximately 625–750 nanometres. It is a primary color in the RGB color model and a seconda ...

and green algae

The green algae (: green alga) are a group of chlorophyll-containing autotrophic eukaryotes consisting of the phylum Prasinodermophyta and its unnamed sister group that contains the Chlorophyta and Charophyta/ Streptophyta. The land plants ...

), Chromista

Chromista is a proposed but polyphyletic obsolete Biology, biological Kingdom (biology), kingdom, refined from the Chromalveolata, consisting of single-celled and multicellular eukaryotic species that share similar features in their Photosynthesi ...

, and Bacteria. Nevertheless, he had already presented this simplified scheme for the first time on his 1981 paper and endorsed it in 1983.

Five of Cavalier-Smith's kingdoms are classified as

Five of Cavalier-Smith's kingdoms are classified as eukaryotes

The eukaryotes ( ) constitute the domain of Eukaryota or Eukarya, organisms whose cells have a membrane-bound nucleus. All animals, plants, fungi, seaweeds, and many unicellular organisms are eukaryotes. They constitute a major group of ...

as shown in the following scheme:

*''Eubacteria''

*Neomura Neomura (from Ancient Greek ''neo-'' "new", and Latin ''-murus'' "wall") is a proposed clade of life composed of the two domains Archaea and Eukaryota, coined by Thomas Cavalier-Smith in 2002. Its name reflects the hypothesis that both archaea and ...

**''Archaebacteria''

**Eukaryotes

***Kingdom Protozoa

*** Unikont

Amorphea is a taxonomic supergroup that includes the basal Amoebozoa and Obazoa. That latter contains the Opisthokonta, which includes the fungi, animals and the choanoflagellates. The taxonomic affinities of the members of this clade were or ...

s (heterotrophs

A heterotroph (; ) is an organism that cannot produce its own food, instead taking nutrition from other sources of organic carbon, mainly plant or animal matter. In the food chain, heterotrophs are primary, secondary and tertiary consumers, but ...

)

****Kingdom Animalia

****Kingdom Fungi

*** Bikonts (primarily photosynthetic

Photosynthesis ( ) is a Biological system, system of biological processes by which Photoautotrophism, photosynthetic organisms, such as most plants, algae, and cyanobacteria, convert light energy, typically from sunlight, into the chemical ener ...

)

****Kingdom Plantae (including red and green algae)

****Kingdom Chromista

The kingdom Animalia was divided into four subkingdoms: Radiata

Radiata or Radiates is a historical taxonomic rank that was used to classify animals with Symmetry (biology)#Radial symmetry, radially symmetric body plans. The term Radiata is no longer accepted, as it united several different groupings of anim ...

(phyla Porifera

Sponges or sea sponges are primarily marine invertebrates of the animal phylum Porifera (; meaning 'pore bearer'), a Basal (phylogenetics) , basal clade and a sister taxon of the Eumetazoa , diploblasts. They are sessility (motility) , sessile ...

, Cnidaria

Cnidaria ( ) is a phylum under kingdom Animalia containing over 11,000 species of aquatic invertebrates found both in fresh water, freshwater and marine environments (predominantly the latter), including jellyfish, hydroid (zoology), hydroids, ...

, Placozoa

Placozoa ( ; ) is a phylum of free-living (non-parasitic) marine invertebrates. They are blob-like animals composed of aggregations of cells. Moving in water by ciliary motion, eating food by Phagocytosis, engulfment, reproducing by Fission (biol ...

, and Ctenophora

Ctenophora (; : ctenophore ) is a phylum of marine invertebrates, commonly known as comb jellies, that inhabit sea waters worldwide. They are notable for the groups of cilia they use for swimming (commonly referred to as "combs"), and they are ...

), Myxozoa

Myxozoa (etymology: Greek: μύξα ''myxa'' "slime" or "mucus" + thematic vowel o + ζῷον ''zoon'' "animal") is a subphylum of aquatic cnidarian animals – all obligate parasites. It contains the smallest animals ever known to have lived. ...

, Mesozoa

The Mesozoa are minuscule, worm-like parasites of marine invertebrates. Generally, these tiny, elusive creatures consist of a somatoderm (outer layer) of ciliated cells surrounding one or more reproductive cells.

A 2017 study recovered Mesozoa ...

, and Bilateria

Bilateria () is a large clade of animals characterised by bilateral symmetry during embryonic development. This means their body plans are laid around a longitudinal axis with a front (or "head") and a rear (or "tail") end, as well as a left� ...

(all other animal phyla).

He created three new animal phyla: Acanthognatha (rotifers

The rotifers (, from Latin 'wheel' and 'bearing'), sometimes called wheel animals or wheel animalcules, make up a phylum (Rotifera ) of microscopic and near-microscopic pseudocoelomate animals.

They were first described by Rev. John Harris ...

, acanthocephalans, gastrotrichs

The gastrotrichs (phylum Gastrotricha), common name, commonly referred to as hairybellies or hairybacks, are a group of Microscopic scale, microscopic (0.06–3.0 mm), cylindrical, acoelomate animals, and are widely distributed and abundant ...

, and gnathostomulids), Brachiozoa (brachiopods

Brachiopods (), phylum Brachiopoda, are a phylum of animals that have hard "valves" (shells) on the upper and lower surfaces, unlike the left and right arrangement in bivalve molluscs. Brachiopod valves are hinged at the rear end, while the fron ...

and phoronids), and Lobopoda (onychophorans

Onychophora (from , , "claws"; and , , "to carry"), commonly known as velvet worms (for their velvety texture and somewhat wormlike appearance) or more ambiguously as peripatus (after the first described genus, ''Peripatus''), is a phylum of el ...

and tardigrades

Tardigrades (), known colloquially as water bears or moss piglets, are a phylum of eight-legged Segmentation (biology), segmented micro-animals. They were first described by the German zoologist Johann August Ephraim Goeze in 1773, who calle ...

)

and recognised a total of 23 animal phyla.

Cavalier-Smith's 2003 classification scheme:

* Unikont

Amorphea is a taxonomic supergroup that includes the basal Amoebozoa and Obazoa. That latter contains the Opisthokonta, which includes the fungi, animals and the choanoflagellates. The taxonomic affinities of the members of this clade were or ...

s

** protozoan phylum Amoebozoa

Amoebozoa is a major Taxonomy (biology), taxonomic group containing about 2,400 described species of Amoeba, amoeboid protists, often possessing blunt, fingerlike, Pseudopod#Morphology, lobose pseudopods and tubular mitochondrial cristae. In trad ...

(ancestrally uniciliate)

** opisthokonts

*** uniciliate protozoan phylum Choanozoa

Choanozoa is a clade of opisthokont eukaryotes consisting of the choanoflagellates (Choanoflagellatea) and the animals (Animalia, Metazoa). The sister-group relationship between the choanoflagellates and animals has important implications for t ...

*** kingdom Fungi

*** kingdom Animalia

Animals are multicellular, eukaryotic organisms in the Biology, biological Kingdom (biology), kingdom Animalia (). With few exceptions, animals heterotroph, consume organic material, Cellular respiration#Aerobic respiration, breathe oxygen, ...

* Bikonts

** protozoan infrakingdom Rhizaria

The Rhizaria are a diverse and species-rich clade of mostly unicellular eukaryotes. Except for the Chlorarachniophytes and three species in the genus '' Paulinella'' in the phylum Cercozoa, they are all non-photosynthetic, but many Foraminifera ...

*** phylum Cercozoa

Cercozoa (now synonymised with Filosa) is a phylum of diverse single-celled eukaryotes. They lack shared morphological characteristics at the microscopic level, and are instead united by phylogeny, molecular phylogenies of rRNA and actin or Ubiqu ...

*** phylum Retaria

Retaria is a clade within the supergroup Rhizaria containing the Foraminifera and the Radiolaria. In 2019, the Retaria were recognized as a basal Rhizaria group, as sister of the Cercozoa

Cercozoa (now synonymised with Filosa) is a phylum of ...

( Radiozoa and Foraminifera

Foraminifera ( ; Latin for "hole bearers"; informally called "forams") are unicellular organism, single-celled organisms, members of a phylum or class (biology), class of Rhizarian protists characterized by streaming granular Ectoplasm (cell bio ...

)

** protozoan infrakingdom Excavata

Excavata is an obsolete, extensive and diverse paraphyletic group of unicellular Eukaryota. The group was first suggested by Simpson and Patterson in 1999 and the name latinized and assigned a rank by Thomas Cavalier-Smith in 2002. It contains ...

*** phylum Loukozoa

Loukozoa (From Greek ''loukos'': groove) is a proposed taxon used in some classifications of eukaryotes, consisting of the Metamonada and Malawimonadea. Ancyromonads are closely related to this group, as sister of the entire group, or as sister ...

*** phylum Metamonada

*** phylum Euglenozoa

Euglenozoa are a large group of flagellate Discoba. They include a variety of common free-living species, as well as a few important parasites, some of which infect humans. Euglenozoa are represented by four major groups, ''i.e.,'' Kinetoplastea, ...

*** phylum Percolozoa

The Percolozoa are a group of colourless, non-photosynthetic excavates, including many that can transform between amoeboid, flagellate, and cyst stages.

Characteristics

Most Percolozoa are found as bacterivores in soil, fresh water and occasion ...

** protozoan phylum Apusozoa ( Thecomonadea and Diphylleida

Collodictyonidae (also Diphylleidae) is a group of aquatic, unicellular Eukaryote, eukaryotic organisms with two to four terminal Flagellum, flagella. They feed by phagocytosis, ingesting other unicellular organisms like algae and bacteria.

Rec ...

)

** the chromalveolate clade

*** kingdom Chromista

Chromista is a proposed but polyphyletic obsolete Biology, biological Kingdom (biology), kingdom, refined from the Chromalveolata, consisting of single-celled and multicellular eukaryotic species that share similar features in their Photosynthesi ...

(Cryptista

Cryptista is a clade of alga-like eukaryotes. It is most likely related to Archaeplastida which includes plants and many algae, within the larger group Diaphoretickes.

Other characteristic features of cryptophyte mtDNAs include large syntenic ...

, Heterokonta, and Haptophyta

The haptophytes, classified either as the Haptophyta, Haptophytina or Prymnesiophyta (named for '' Prymnesium''), are a clade of algae.

The names Haptophyceae or Prymnesiophyceae are sometimes used instead. This ending implies classification at ...

)

*** protozoan infrakingdom Alveolata

**** phylum Ciliophora

The ciliates are a group of alveolates characterized by the presence of hair-like organelles called cilia, which are identical in structure to eukaryotic flagella, but are in general shorter and present in much larger numbers, with a different ...

**** phylum Miozoa ( Protalveolata, Dinozoa, and Apicomplexa

The Apicomplexa (also called Apicomplexia; single: apicomplexan) are organisms of a large phylum of mainly parasitic alveolates. Most possess a unique form of organelle structure that comprises a type of non-photosynthetic plastid called an ap ...

)

** kingdom Plantae

Plants are the eukaryotes that form the kingdom Plantae; they are predominantly photosynthetic. This means that they obtain their energy from sunlight, using chloroplasts derived from endosymbiosis with cyanobacteria to produce sugars fro ...

( Viridaeplantae, Rhodophyta

Red algae, or Rhodophyta (, ; ), make up one of the oldest groups of eukaryotic algae. The Rhodophyta comprises one of the largest phyla of algae, containing over 7,000 recognized species within over 900 genera amidst ongoing taxonomic revisions. ...

and Glaucophyta

The glaucophytes, also known as glaucocystophytes or glaucocystids, are a small group of unicellular algae found in freshwater and moist terrestrial environments, less common today than they were during the Proterozoic. The stated number of spec ...

)

Seven kingdoms model

Cavalier-Smith and his collaborators revised the classification in 2015, and published it in '' PLOS ONE''. In this scheme they reintroduced the division of prokaryotes into two kingdoms, Bacteria (previously 'Eubacteria') and Archaea (previously 'Archebacteria'). This is based on the consensus in the Taxonomic Outline of Bacteria and Archaea (TOBA) and theCatalogue of Life

The Catalogue of Life (CoL) is an online database that provides an index of known species of animals, plants, fungi, and microorganisms. It was created in 2001 as a partnership between the global Species 2000 and the American Integrated Taxono ...

.

Proposed root of the tree of life

In 2006, Cavalier-Smith proposed that thelast universal common ancestor

The last universal common ancestor (LUCA) is the hypothesized common ancestral cell from which the three domains of life, the Bacteria, the Archaea, and the Eukarya originated. The cell had a lipid bilayer; it possessed the genetic code a ...

to all life was a non-flagellate Gram-negative bacterium ("negibacterium") with two membranes (also known as diderm bacterium).

Awards and honours

Cavalier-Smith was elected Fellow of theLinnean Society of London

The Linnean Society of London is a learned society dedicated to the study and dissemination of information concerning natural history, evolution, and Taxonomy (biology), taxonomy. It possesses several important biological specimen, manuscript a ...

(FLS) in 1980, the Institute of Biology

The Institute of Biology (IoB) was a professional body for biologists, primarily those working in the United Kingdom. The Institute was founded in 1950 by the Biological Council: the then umbrella body for Britain's many learned biological societie ...

(FIBiol) in 1983, the Royal Society of Arts

The Royal Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce, commonly known as the Royal Society of Arts (RSA), is a learned society that champions innovation and progress across a multitude of sectors by fostering creativity, s ...

(FRSA) in 1987, the Canadian Institute for Advanced Research (CIFAR) in 1988, the Royal Society of Canada

The Royal Society of Canada (RSC; , SRC), also known as the Academies of Arts, Humanities, and Sciences of Canada (French: ''Académies des arts, des lettres et des sciences du Canada''), is the senior national, bilingual council of distinguishe ...

(FRSC) in 1997, and the Royal Society of London

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, r ...

(FRS) in 1998.

He received the International Prize for Biology

The is an annual award for "outstanding contribution to the advancement of research in fundamental biology." The Prize, although it is not always awarded to a biologist, is one of the most prestigious honours a natural scientist can receive. Ther ...

from the Emperor of Japan in 2004, and the Linnean Medal

The Linnean Medal of the Linnean Society of London was established in 1888, and is awarded annually to alternately a botanist or a zoologist or (as has been common since 1958) to one of each in the same year. The medal was of gold until 1976, and ...

for Zoology in 2007. He was appointed Fellow of the Canadian Institute for Advanced Research (CIFAR) between 1998 and 2007, and Advisor of the Integrated Microbial Biodiversity of CIFAR. He won the 2007 Frink Medal of the Zoological Society of London

The Zoological Society of London (ZSL) is a charity and organization devoted to the worldwide animal conservation, conservation of animals and their habitat conservation, habitats. It was founded in 1826. Since 1828, it has maintained London Zo ...

.

References

External links

* * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Cavalier-Smith, Thomas English biologists Protistologists 1942 births British evolutionary biologists English humanists English microbiologists English taxonomists Fellows of the Royal Society People educated at Norwich School Alumni of Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge Alumni of King's College London Academics of King's College London Academics of the University of Oxford 20th-century British biologists 21st-century biologists 20th-century British scientists 21st-century British scientists 2021 deaths Thomas Cavalier-Smith